- RETIREMENT ANNOUNCEMENT

- HOME PAGE

- "MYCHART" the new patient portal

- BELMONT MEDICAL ASSOCIATES

- MOUNT AUBURN HOSPITAL

- EMERGENCIES

- PRACTICE PHILOSOPHY

- MY RESUME

- TELEMEDICINE CONSULTATION

- CONTACT ME

- LAB RESULTS

- ePRESCRIPTIONS

- eREFERRALS

- RECORD RELEASE

- MEDICAL SCRIBE

- PHYSICIAN ASSISTANT (PA)

- Medicare Annual Wellness Visit

- Case management/Social work

- Quality Care Measures

- Emergency closing notice

- FEEDBACK

- Talking to your doctor

- Choosing..... and losing a doctor

- INDEX A - Z

- ALLERGIC REACTIONS

- Alternative Medicine

- Alzheimer's Disease

- Bladder Problems

- Blood disorders

- Cancer Concerns

- GENETIC TESTING FOR HEREDITARY CANCER

- Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

- Controversial Concerns

- CPR : Learn and save a life

- CRP : Inflammatory marker

- Diabetes Management

- Dizziness, Vertigo,Tinnitus and Hearing Loss

- EXERCISE

- FEMALE HEALTH

-

GASTROINTESTINAL topics

- Appendicitis

- BRAT diet

- Celiac Disease or Sprue

- Crohn's Disease

- Gastroenterologists for Colon Cancer Screening

- Colonoscopy PREP

- Constipation

- Gluten sensitivity, but not celiac disease

- Heartburn and GERD

- Hemorrhoids and Anal fissure

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- NASH : Non Alcoholic Steato Hepatitis

- FEET PROBLEMS

- HEART RELATED topics

-

INFECTIOUS DISEASES

- Antibiotic Resistance

- Cat bites >

- Clostridia difficile infection - the "antibiotic associated germ"

- CORONA VIRUS

- Dengue Fever and Chikungunya Fever

- Food borne illnesses

- Shingles Vaccine

- Hepatitis B

- Hepatitis C

- Herpes

- Influenza

- Helicobacter pylori - the "ulcer germ"

- HIV Screening

- Lyme and other tick borne diseases

- Measles

- Meningitis

- MRSA (Staph infection)

- Norovirus

- Sexually Transmitted Diseases

- Shingles (Herpes Zoster)

- Sinusitis

- West Nile Virus

- Whooping Cough (Pertussis)

- Zika virus and pregnancy

- INSURANCE related topics

- KIDNEY STONES

- LEG CRAMPS

- LIBRARY for patients

- LIFE DECISIONS

- MALE HEALTH

- Medication/Drug side effects

- MEDICAL MARIJUANA

- MENTAL HEALTH

- Miscellaneous Articles

-

NUTRITION - EXERCISE - WEIGHT

- Cholesterol : New guidelines for treatment

- Advice to lower your cholesterol

- Cholesterol : Control

- Cholesterol : Raising your HDL Level

- Exercise

- Food : Making Smart Choices

- Food : Making Poor Choices

- Food : Grape Fruit and Drug Interaction

- Food : Vitamins, Minerals and Supplements

- Omega 3 fatty acids

- Vitamin B12 deficiency

- Vitamin D

- Weight Loss

- ORTHOPEDICS

- PAIN

- PATIENTS' RIGHTS

- SKIN

- SLEEP

- SMOKING

- STROKE

- THYROID

- SUBSTANCE ABUSE

- Travel and Vaccination

- TREMOR

- Warfarin Anticoagulation

- OTHER STUFF FOLLOWS

- Fact or Opinion?

- Hippocratic Oath

- FREE ADVICE.......for what its worth!

- LAUGHTER.....is the best medicine

- Physicians Pet Peeves

- PHOTO ALBUM - its not all work!

- Cape Town, South Africa

- Tribute page

- The 100 Club

- Free Wi-Fi

ALLERGIES

The Season's Public Enemies

With Trees Shedding Pollen Early, Allergy Sufferers Are in for Unusually Severe Symptoms

Laura Landro : WSJ : March 13, 2012

Jeffrey Bryant is used to the discomforts of hay fever in spring, when trees normally bloom in his hometown of Louisville, Ky. This year was different: Mr. Bryant felt his symptoms come on with a vengeance when it was still January.

"It's never been as bad as this and never started as early," Mr. Bryant says. The 48-year-old computer programmer usually relies on medications to ease his coughing, sneezing and other symptoms. Now, he is working with his doctor to get started on a series of shots that he hopes will control his allergies within a few weeks.

Mild winter temperatures in many parts of the country—the fourth warmest winter since record-keeping began—have triggered an unusually early release of pollen from trees. That bodes badly for the millions of people who suffer from allergic rhinitis—commonly known as hay fever.

Allergists are predicting a longer, and more intense, allergy season than normal. Once people have been exposed to the early pollen, essentially priming the immune system to react to the allergens, there is little chance of relief even if temperatures cool down again. This priming effect can bring on even more severe symptoms for allergy patients, especially those with asthma, says Neil Kao, an allergist in Greenville, N.C.

Medications, including eye drops, antihistamines and nasal sprays, can relieve hay-fever symptoms for many people. For greatest effect, these products usually need to be used just before any exposure to pollen, says Stanley Fineman, an allergy specialist in Marietta, Ga. But this year "we didn't catch it in time because we didn't know the pollen was going to start so early," says Dr. Fineman, who also is president of the American College of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology, which represents allergists. Weather websites often signal when local pollen counts start to rise.

More aggressive treatments, including immune-boosting allergy shots, are also available, and specialists expect more patients may pursue these remedies this year if their symptoms are worse than normal.

Different pollens serve as triggers to different people. Allergy shots, which administer escalating doses of the offending allergens, work like a vaccine to create resistance in the patient. But these can take several months to become effective. Doctors increasingly are recommending faster treatment protocols that deliver the shots over a shorter period and can bring relief within a few weeks.

Allergists also may offer the same type of immunotherapy in the form of drops under the tongue, which patients can use at home after an initial visit. Pharmaceutical firms are developing immunotherapy tablets, to be taken orally, including one from Merck & Co . that has been shown in trials to reduce symptoms of ragweed allergy.

Other researchers are investigating new methods to give patients faster and more effective allergy relief, such as delivering the allergens through the skin or by way of the lymph nodes.

As many as 30% of children and up to 40% of adults suffer from seasonal allergies that cause reactions such as sneezing, itching, stuffy nose, and watery eyes. Trees are one of the earliest plants to release pollen, followed later by pollen from grass and flowering plants. For example, high concentrations of tree pollen in Kansas City, Mo., Tuesday came mainly from juniper, elm and maple trees, according to data compiled by the National Allergy Bureau, part of research group American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. Ditto for Atlanta, where the top offenders were pine, oak and birch.

Some studies suggest climate change, by promoting longer blooming seasons, may increase the prevalence of certain allergens and the time during which people are exposed to them. Warmer temperatures also can boost concentrations of mold, another allergen that is usually killed by colder weather, says James Sublett, the Louisville allergy specialist treating Mr. Bryant.

Improved medications have been introduced to treat allergy symptoms in recent years, including antihistamines, nasal steroid sprays and drugs that block inflammatory chemicals produced by the body. The products are generally safe and effective. But in a large survey of adults presented at an annual allergy conference in 2006, about a third of respondents said they switched medication either because of a lack of effectiveness or side effects.

Unlike medication, allergy shots can potentially lead to lasting remission of symptoms after three to five years.

The treatment, which is formally known as subcutaneous immunotherapy and is generally covered by health insurance plans, may also help prevent development of asthma and new allergies. The shots are typically given once or twice a week for about five months, after which their frequency is reduced.

Growing in popularity is a faster treatment, known as "cluster" therapy, that involves two to four injections one day a week for three weeks. Patients' own immune systems are mobilized and able to counteract naturally occurring allergens often within a few weeks, says Richard Weber, an allergy specialist at National Jewish Health in Denver. Risks include an increased chance of irritation at the injection site and a possibly serious reaction to the allergen.

Rachel Lowe, a 40-year-old plastic-surgery nurse in Marietta, Ga., recently started cluster shots recommended by Dr. Fineman after her allergies kicked in in early February. "I always dread when everything is in bloom because my allergies are so bad that I need to lock myself indoors sometimes and can't enjoy the spring," she says.

Some physicians are administering drops under the tongue, known as sublingual immunotherapy, that contain the same substances used in shots. The technique has been used since the 1980s in Europe, where it has been shown to produce lasting remissions in long-term use. It doesn't have U.S. regulatory approval, but some doctors give it to patients anyway as an "off-label" use of the substance.

Other doctors steer clear of the technique because insurers typically don't cover it and there are no standards in the U.S. for dosage and duration of treatment, says Linda Cox, an allergist in Fort Lauderdale, Fla. Another concern, she says: potential liability if something goes wrong.

Steven Prager, an allergist in California, says he began offering sublingual immunotherapy two years ago because many patients don't like shots or find multiple office visits inconvenient. He says he develops a formula for the drops for each patient based on the severity of their allergies. The treatments cost about $75 a month.

A Child’s Allergies Are Serious but

Can Be Treated Effectively

By Walecia Konrad : NT Times Article : March 5, 2010

It starts with a telltale sniffle, itchy eyes and an occasional cough. You think your little one is getting a cold, but the cold never comes while the runny nose seems never to leave.

“That could be a sign of allergies,” says Dr. Kevin Weiss, an expert on allergies and president of the American Board of Medical Specialties. Not a surprising diagnosis when you consider that more than 40 percent of children (and 20 to 30 percent of adults) suffer from allergic rhinitis, often simply called allergies. With spring pollen season just around the corner, parents are bound to hear more of those telltale sniffles.

Allergies are no trivial matter. Each year, allergic rhinitis accounts for two million missed school days and $2.3 million in health care costs for children younger than 12. It’s not unusual for allergy sufferers to spend thousands of dollars each year on doctor visits, medications and other products, says Dr. Linda Cox, an allergist practicing in Ft. Lauderdale, Fla., and a former committee chairwoman for the American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology

What’s more, Dr. Cox said, allergies left untreated in children can often lead to asthma, a chronic and debilitating pulmonary disease.

For the purposes of this article I’ll focus on allergic rhinitis, particularly among children. (The subject of food allergies may warrant a separate, future column.) The condition can be set off by outside elements like pollen from ragweed, grasses and trees and indoor allergens like dust mites and pet dander.

Combating allergies often requires a multipronged and sometimes costly approach. Here’s what you can do to make sure your child gets the best results.

THE RIGHT DOCTOR

Most allergies can be identified and treated by a pediatrician or family doctor. The doctor will use blood tests and your child’s symptoms to come up with an educated guess on what is causing the problem.

“Mild allergies can be treated without a lot of testing,” Dr. Weiss said. New nondrowsy prescription and over-the-counter medications make it easier to treat symptoms, he added. Your child’s doctor should know which drugs are appropriate for children.

That’s good news, because allergists aren’t always part of an insurer’s network or covered under high-deductible plans.

Nevertheless, an allergist can best treat your child if symptoms become moderate to severe. If your child is extremely uncomfortable, losing sleep or missing a lot of school, and the current medications he or she is using aren’t working, you may need to take the next step. An allergist will most likely do a skin test to pinpoint exactly what your child is allergic to. This is often more precise than the blood tests and is usually covered by insurance.

ELIMINATE THE SOURCE

After you and your child’s doctor have narrowed down the possible culprits, it’s time to reduce or remove the troublemakers. Many of the most effective ways to do this are labor-intensive but low in cost, said Dr. James Sublett, an allergist in Louisville, Ky., and professor of pediatric allergy and immunology at the University of Louisville School of Medicine.

Keep your pet away from carpeted rooms, sleeping areas, upholstered furniture and other places where it becomes difficult or impossible to remove dander. Cats are the animals that cause the most allergy problems, and cat allergen can remain in a house for an average of 20 weeks after an animal is removed.

If you and your doctor suspect dust mites are a problem, remove drapes, stuffed animals, pet bedding, upholstered furniture and even carpeting from the bedroom. Wash linens frequently. Dust with a moist cloth or an electrostatic fabric duster. Both do a better job of actually collecting dust rather than just stirring it around. Remember: dust takes a couple of hours to settle after cleaning and vacuuming.

Tumble-drying stuffed animals on high heat for 20 minutes will also kill dust mites.

Get rid of any pest problems, like roaches or mice. Both can be huge allergy triggers. In addition, keep windows closed during peak allergy season.

CONSIDER IMMUNOTHERAPY

Even after you’ve identified and tried to eliminate the source of your child’s allergies, he or she may still be suffering. If that happens, you may have to go for the shots.

Allergy shots have come in for criticism over the years because, well, they are shots and require repeat visits to the doctor’s office — two things children really don’t like.

And many parents may wonder — in some cases, rightfully, alas — whether the allergy doctor is overdiagnosing allergies and overtreating their children. Dr. Cox argues that allergists get to the root of the cause instead of just treating symptoms. General practitioners can prescribe medicines to treat symptoms without easing the condition, she says. In any case, it is important to get a referral from a pediatrician or family doctor whom you trust to do what’s right for your child.

A new study published last month in the peer-reviewed Annals of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology found that allergy shots, also known as immunotherapy, could actually help eliminate allergy symptoms after only 18 months. What’s more, shots may help save you money in the long run. Among the children with allergic rhinitis studied, shots helped to reduce total health care costs by a third, and prescription drug costs by 16 percent, said Dr. Cox, who was a co-author of the study.

In immunotherapy, an allergist injects a small amount of the allergen into a patient. This prompts the body to make natural antibodies, which naturally increase one’s immunity to the culprit. “It is the only therapy that doesn’t just treat allergy symptoms but tries to get at the cause,” Dr. Cox said.

But because the allergist personally mixes the allergens according to a patient’s needs, the shots are not considered pharmaceuticals and are sometimes not covered by insurance.

The first year of allergy shots, which includes a three-month build-up period during which a child receives injections as often as twice a week until the proper dosage is found, would cost a bit less than $1,000 for the year, according to Dr. Cox. The next year, with twice-a-month injections, would total an estimated $350.

For parents who are uninsured and cannot afford shots for their children, Dr. Cox suggests contacting the state allergy society for a list of allergists and clinics that may offer low or no-cost treatments. (Because there is no clearinghouse for such information, you’ll probably have to do your own Web sleuthing.)

AVOID THE UNNECESSARY

There’s no end to the number of products marketed to allergy sufferers, including air filters, humidifiers, dehumidifiers, ozone machines, mattress and pillow encasements, special breathing masks and more. Many of these products are expensive and some are ineffective. Ozone, for instance, can be a pollutant and actually worsen allergies, Dr. Sublett said.

Several studies show that there are no significant improvements from using mattress and pillow encasements and other allergy-fighting products. The best thing to do is to take the necessary steps to remove allergens like the ones discsponsored by the American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. If you’re covered by an H.M.O. or other health network, you’ll need to ask your primary physician for a referral.

With Trees Shedding Pollen Early, Allergy Sufferers Are in for Unusually Severe Symptoms

Laura Landro : WSJ : March 13, 2012

Jeffrey Bryant is used to the discomforts of hay fever in spring, when trees normally bloom in his hometown of Louisville, Ky. This year was different: Mr. Bryant felt his symptoms come on with a vengeance when it was still January.

"It's never been as bad as this and never started as early," Mr. Bryant says. The 48-year-old computer programmer usually relies on medications to ease his coughing, sneezing and other symptoms. Now, he is working with his doctor to get started on a series of shots that he hopes will control his allergies within a few weeks.

Mild winter temperatures in many parts of the country—the fourth warmest winter since record-keeping began—have triggered an unusually early release of pollen from trees. That bodes badly for the millions of people who suffer from allergic rhinitis—commonly known as hay fever.

Allergists are predicting a longer, and more intense, allergy season than normal. Once people have been exposed to the early pollen, essentially priming the immune system to react to the allergens, there is little chance of relief even if temperatures cool down again. This priming effect can bring on even more severe symptoms for allergy patients, especially those with asthma, says Neil Kao, an allergist in Greenville, N.C.

Medications, including eye drops, antihistamines and nasal sprays, can relieve hay-fever symptoms for many people. For greatest effect, these products usually need to be used just before any exposure to pollen, says Stanley Fineman, an allergy specialist in Marietta, Ga. But this year "we didn't catch it in time because we didn't know the pollen was going to start so early," says Dr. Fineman, who also is president of the American College of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology, which represents allergists. Weather websites often signal when local pollen counts start to rise.

More aggressive treatments, including immune-boosting allergy shots, are also available, and specialists expect more patients may pursue these remedies this year if their symptoms are worse than normal.

Different pollens serve as triggers to different people. Allergy shots, which administer escalating doses of the offending allergens, work like a vaccine to create resistance in the patient. But these can take several months to become effective. Doctors increasingly are recommending faster treatment protocols that deliver the shots over a shorter period and can bring relief within a few weeks.

Allergists also may offer the same type of immunotherapy in the form of drops under the tongue, which patients can use at home after an initial visit. Pharmaceutical firms are developing immunotherapy tablets, to be taken orally, including one from Merck & Co . that has been shown in trials to reduce symptoms of ragweed allergy.

Other researchers are investigating new methods to give patients faster and more effective allergy relief, such as delivering the allergens through the skin or by way of the lymph nodes.

As many as 30% of children and up to 40% of adults suffer from seasonal allergies that cause reactions such as sneezing, itching, stuffy nose, and watery eyes. Trees are one of the earliest plants to release pollen, followed later by pollen from grass and flowering plants. For example, high concentrations of tree pollen in Kansas City, Mo., Tuesday came mainly from juniper, elm and maple trees, according to data compiled by the National Allergy Bureau, part of research group American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. Ditto for Atlanta, where the top offenders were pine, oak and birch.

Some studies suggest climate change, by promoting longer blooming seasons, may increase the prevalence of certain allergens and the time during which people are exposed to them. Warmer temperatures also can boost concentrations of mold, another allergen that is usually killed by colder weather, says James Sublett, the Louisville allergy specialist treating Mr. Bryant.

Improved medications have been introduced to treat allergy symptoms in recent years, including antihistamines, nasal steroid sprays and drugs that block inflammatory chemicals produced by the body. The products are generally safe and effective. But in a large survey of adults presented at an annual allergy conference in 2006, about a third of respondents said they switched medication either because of a lack of effectiveness or side effects.

Unlike medication, allergy shots can potentially lead to lasting remission of symptoms after three to five years.

The treatment, which is formally known as subcutaneous immunotherapy and is generally covered by health insurance plans, may also help prevent development of asthma and new allergies. The shots are typically given once or twice a week for about five months, after which their frequency is reduced.

Growing in popularity is a faster treatment, known as "cluster" therapy, that involves two to four injections one day a week for three weeks. Patients' own immune systems are mobilized and able to counteract naturally occurring allergens often within a few weeks, says Richard Weber, an allergy specialist at National Jewish Health in Denver. Risks include an increased chance of irritation at the injection site and a possibly serious reaction to the allergen.

Rachel Lowe, a 40-year-old plastic-surgery nurse in Marietta, Ga., recently started cluster shots recommended by Dr. Fineman after her allergies kicked in in early February. "I always dread when everything is in bloom because my allergies are so bad that I need to lock myself indoors sometimes and can't enjoy the spring," she says.

Some physicians are administering drops under the tongue, known as sublingual immunotherapy, that contain the same substances used in shots. The technique has been used since the 1980s in Europe, where it has been shown to produce lasting remissions in long-term use. It doesn't have U.S. regulatory approval, but some doctors give it to patients anyway as an "off-label" use of the substance.

Other doctors steer clear of the technique because insurers typically don't cover it and there are no standards in the U.S. for dosage and duration of treatment, says Linda Cox, an allergist in Fort Lauderdale, Fla. Another concern, she says: potential liability if something goes wrong.

Steven Prager, an allergist in California, says he began offering sublingual immunotherapy two years ago because many patients don't like shots or find multiple office visits inconvenient. He says he develops a formula for the drops for each patient based on the severity of their allergies. The treatments cost about $75 a month.

A Child’s Allergies Are Serious but

Can Be Treated Effectively

By Walecia Konrad : NT Times Article : March 5, 2010

It starts with a telltale sniffle, itchy eyes and an occasional cough. You think your little one is getting a cold, but the cold never comes while the runny nose seems never to leave.

“That could be a sign of allergies,” says Dr. Kevin Weiss, an expert on allergies and president of the American Board of Medical Specialties. Not a surprising diagnosis when you consider that more than 40 percent of children (and 20 to 30 percent of adults) suffer from allergic rhinitis, often simply called allergies. With spring pollen season just around the corner, parents are bound to hear more of those telltale sniffles.

Allergies are no trivial matter. Each year, allergic rhinitis accounts for two million missed school days and $2.3 million in health care costs for children younger than 12. It’s not unusual for allergy sufferers to spend thousands of dollars each year on doctor visits, medications and other products, says Dr. Linda Cox, an allergist practicing in Ft. Lauderdale, Fla., and a former committee chairwoman for the American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology

What’s more, Dr. Cox said, allergies left untreated in children can often lead to asthma, a chronic and debilitating pulmonary disease.

For the purposes of this article I’ll focus on allergic rhinitis, particularly among children. (The subject of food allergies may warrant a separate, future column.) The condition can be set off by outside elements like pollen from ragweed, grasses and trees and indoor allergens like dust mites and pet dander.

Combating allergies often requires a multipronged and sometimes costly approach. Here’s what you can do to make sure your child gets the best results.

THE RIGHT DOCTOR

Most allergies can be identified and treated by a pediatrician or family doctor. The doctor will use blood tests and your child’s symptoms to come up with an educated guess on what is causing the problem.

“Mild allergies can be treated without a lot of testing,” Dr. Weiss said. New nondrowsy prescription and over-the-counter medications make it easier to treat symptoms, he added. Your child’s doctor should know which drugs are appropriate for children.

That’s good news, because allergists aren’t always part of an insurer’s network or covered under high-deductible plans.

Nevertheless, an allergist can best treat your child if symptoms become moderate to severe. If your child is extremely uncomfortable, losing sleep or missing a lot of school, and the current medications he or she is using aren’t working, you may need to take the next step. An allergist will most likely do a skin test to pinpoint exactly what your child is allergic to. This is often more precise than the blood tests and is usually covered by insurance.

ELIMINATE THE SOURCE

After you and your child’s doctor have narrowed down the possible culprits, it’s time to reduce or remove the troublemakers. Many of the most effective ways to do this are labor-intensive but low in cost, said Dr. James Sublett, an allergist in Louisville, Ky., and professor of pediatric allergy and immunology at the University of Louisville School of Medicine.

Keep your pet away from carpeted rooms, sleeping areas, upholstered furniture and other places where it becomes difficult or impossible to remove dander. Cats are the animals that cause the most allergy problems, and cat allergen can remain in a house for an average of 20 weeks after an animal is removed.

If you and your doctor suspect dust mites are a problem, remove drapes, stuffed animals, pet bedding, upholstered furniture and even carpeting from the bedroom. Wash linens frequently. Dust with a moist cloth or an electrostatic fabric duster. Both do a better job of actually collecting dust rather than just stirring it around. Remember: dust takes a couple of hours to settle after cleaning and vacuuming.

Tumble-drying stuffed animals on high heat for 20 minutes will also kill dust mites.

Get rid of any pest problems, like roaches or mice. Both can be huge allergy triggers. In addition, keep windows closed during peak allergy season.

CONSIDER IMMUNOTHERAPY

Even after you’ve identified and tried to eliminate the source of your child’s allergies, he or she may still be suffering. If that happens, you may have to go for the shots.

Allergy shots have come in for criticism over the years because, well, they are shots and require repeat visits to the doctor’s office — two things children really don’t like.

And many parents may wonder — in some cases, rightfully, alas — whether the allergy doctor is overdiagnosing allergies and overtreating their children. Dr. Cox argues that allergists get to the root of the cause instead of just treating symptoms. General practitioners can prescribe medicines to treat symptoms without easing the condition, she says. In any case, it is important to get a referral from a pediatrician or family doctor whom you trust to do what’s right for your child.

A new study published last month in the peer-reviewed Annals of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology found that allergy shots, also known as immunotherapy, could actually help eliminate allergy symptoms after only 18 months. What’s more, shots may help save you money in the long run. Among the children with allergic rhinitis studied, shots helped to reduce total health care costs by a third, and prescription drug costs by 16 percent, said Dr. Cox, who was a co-author of the study.

In immunotherapy, an allergist injects a small amount of the allergen into a patient. This prompts the body to make natural antibodies, which naturally increase one’s immunity to the culprit. “It is the only therapy that doesn’t just treat allergy symptoms but tries to get at the cause,” Dr. Cox said.

But because the allergist personally mixes the allergens according to a patient’s needs, the shots are not considered pharmaceuticals and are sometimes not covered by insurance.

The first year of allergy shots, which includes a three-month build-up period during which a child receives injections as often as twice a week until the proper dosage is found, would cost a bit less than $1,000 for the year, according to Dr. Cox. The next year, with twice-a-month injections, would total an estimated $350.

For parents who are uninsured and cannot afford shots for their children, Dr. Cox suggests contacting the state allergy society for a list of allergists and clinics that may offer low or no-cost treatments. (Because there is no clearinghouse for such information, you’ll probably have to do your own Web sleuthing.)

AVOID THE UNNECESSARY

There’s no end to the number of products marketed to allergy sufferers, including air filters, humidifiers, dehumidifiers, ozone machines, mattress and pillow encasements, special breathing masks and more. Many of these products are expensive and some are ineffective. Ozone, for instance, can be a pollutant and actually worsen allergies, Dr. Sublett said.

Several studies show that there are no significant improvements from using mattress and pillow encasements and other allergy-fighting products. The best thing to do is to take the necessary steps to remove allergens like the ones discsponsored by the American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. If you’re covered by an H.M.O. or other health network, you’ll need to ask your primary physician for a referral.

An Abundance of Remedies but

Little Relief

Peter Jaret : NY Times Article : October 25, 2007

In Brief:

Despite dozens of over-the-counter and prescription remedies, millions of allergy sufferers seek better relief.

Allergies are often overlooked by doctors and patients but can lead to serious health problems, including asthma in children.

Rush immunotherapy regimens offer a fast response -- and hold out hope for long-term relief -- but require close monitoring.

Under-the-tongue remedies offer an alternative for the needle shy but aren’t yet F.D.A.-approved.

With more than 35 over-the-counter remedies and 28 prescription medications crowding the market, you’d think it would be easy for hay fever sufferers to find relief.

Think again.

Most of the estimated 50 million Americans who suffer the runny noses, raw and itchy eyes, clogged sinuses and hammering headaches of allergic rhinitis, as hay fever is medically known, aren’t getting the relief they seek. According to a 2005 survey conducted by the Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America, more than half say they’re “very interested” in finding a new medication. One in four reports “constantly trying different medications to find one that works for me.”

Why is it so hard to find an effective treatment?

One problem, experts say, is that allergic rhinitis isn’t taken seriously enough, by doctors or allergy sufferers. “Allergic rhinitis is typically a doorknob complaint,” said Dr. Bradley Marple, professor of otolaryngology at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical School in Dallas. “Patients wait until they’re almost out the door before they say, ’Oh, and by the way, my allergies have been acting up.’” Too many doctors quickly write a prescription or recommend an over-the-counter antihistamine but fail to follow up to see if it worked.

Four out of five allergy sufferers never even make it to the doctor’s office, relying instead on over-the-counter remedies, according to the A.A.F.A. survey. “Unfortunately, that usually means there’s no treatment plan in place,” said Dr. Marple. “A patient may try one antihistamine and if it doesn’t work try another, when what they really need is a decongestant, or a drug that targets another part of the allergic reaction, or a corticosteroid nasal spray.”

That’s too bad, and not only because it means needless suffering. Allergies can lead to sleep problems and set sufferers up for more serious respiratory problems. Children with allergic rhinitis are three times more likely than their non-sniffling counterparts to develop asthma. Kids and adults alike are more likely to develop sinus and ear infections, especially if their allergies go untreated.

The strongest argument for taking allergies seriously comes from results of an ongoing experiment called the Preventive Allergy Treatment Study in Denmark. Seven years after completing a course of allergy shots aimed at quieting an overcharged immune response to harmless substances such as pollen, children in the study were more than four times less likely to develop asthma.

“Those results are really remarkable,” said Dr. Harold Nelson, an allergist at the National Jewish Medical and Research Center in Denver. Along with other evidence, he explained, they show that immunotherapy doesn’t just alleviate symptoms but actually changes the immune system of people with allergies, restoring it to normal.

Unfortunately, few studies have been done to compare one course of allergy treatment with another. Instead, physicians must rely not on evidence-based research but what’s referred to as “expert opinion.” And as Dr. Marple said, “experts can disagree.”

Still, a consensus on the basic plan of attack is emerging.

For mild to moderate allergic rhinitis, over-the-counter remedies are a reasonable first step. Decongestants work by constricting tiny blood vessels and shrinking swollen and inflamed tissue in the lining of the sinuses. Antihistamines block one of the biochemical steps of the allergic process.

If over-the-counter medicines don’t work, it’s time to talk to a doctor or allergist. Many prescribe corticosteroid nasal sprays, which suppress the allergic process at the heart of the problem.

Typically, immunotherapy is the last resort. The treatment involves identifying the specific culprit that’s causing the problem through a series of skin tests or, in some cases, a blood test. Tiny doses of allergen are then injected under the skin in a weekly series of allergy shots to desensitize the immune system.

Some doctors now offer an accelerated protocol called rush or cluster immunotherapy, in which patients receive several shots a day, spaced half an hour apart. “Instead of the six to eight months it usually takes with standard immunotherapy, we can get to maintenance levels in four weeks,” said Dr. Nelson. Because this rush procedure can lead to serious immune reactions, including shock, it must be closely monitored. A ragweed vaccine given over six weeks is also currently in testing.

For the needle-shy, another advance is making immunotherapy more attractive: the use of allergens that dissolve under the tongue. Although widely used in Europe, sublingual allergens haven’t yet won F.D.A. approval in the United States. Allergists are free to prescribe them, but insurance companies won’t cover the cost. Another drawback is that sublingual allergens are only about half as effective as injections in desensitizing the immune system. But patients can take them at home, rather than having to make an office visit for each treatment - an important advantage.

For his part, Dr. Nelson thinks more patients should consider immunotherapy, especially those with severe and persistent allergic rhinitis. “Medications work only as long as you keep taking them,” he said. “Immunotherapy is the only treatment we have that alters the immune system, restoring the same response to allergens like ragweed that we see in normal nonallergic people.”

Unlike pills and nasal sprays, in other words, immunotherapy holds out the possibility of something far better: a cure.

Expert Q + A

On the Trail of Allergy Relief

Peter Jaret : NY Times Article : October 25, 2007

Dr. Bradley Marple is a professor of otolaryngology at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical School and a member of the American Academy of Otolaryngic Allergy Working Group on Allergic Rhinitis.

Q: What causes allergic rhinitis?

A: The immediate trigger can be ragweed pollen, pets, dust mites and a range of other allergens, or substances that stimulate the immune system. For most people these are innocuous substances. People who develop allergic rhinitis have an excess of a certain class of antibodies, called IgE, which makes them unusually sensitive to these otherwise harmless substances. All the symptoms of allergic rhinitis are really part of the immune response.

Q: Does the condition run in families?

A: To a certain extent, yes. If both parents have allergies, a child stands a 75 percent chance of developing them. If neither parent is allergic, the risk drops to 25 percent. The genetic aspects are numerous and overlapping, which means we’re not going to find a single gene that accounts for allergies. And as the percentages suggest, environmental factors also play a role.

Q: How does environment influence the risk of developing allergic rhinitis?

A: To answer that, let me recount a fascinating story. When the Berlin Wall fell in the late 1980s, East Germans on one side of the wall turned out to have a much lower incidence of allergic rhinitis and asthma

One possible answer is what’s called the hygiene hypothesis. The immune system was designed to be exposed in early life to a variety of viruses, bacteria and fungi. Those exposures allow it to develop normally. In a society with very high standards of hygiene, such as West Germany and the United States, the immune system isn’t challenged in the same way. Instead of developing to target real threats, such as bacteria, the immune system may dysfunction and begin to trigger allergies.

Q: Should we be sending children to spend time on farms?

A: That’s one idea. Another more reasonable lesson to learn is that we should be more judicious in our use of antibiotics. A lot of kids develop runny noses, and we shouldn’t be so quick to rush to treat them. Having pets might help. Studies show that young children who grow up with a cat in the house are less likely to develop allergies or asthma. Since I’m allergic to cats, though, I offer that advice reluctantly.

Q: Are there other ways to prevent allergic rhinitis?

A: The key to prevention is avoidance, which is easier said than done. You can eradicate the disease if you can get rid of the allergen that’s causing problems. In the case of dust mites, which tend to live in the bedroom, you can wash sheets regularly and keep humidity down to below 50 percent, which drives down dust mite populations. You can remove carpeting and any stuffed animals from the bedroom, which are also home to dust mites. Of course if you’re allergic to cats or dogs, it’s a good idea not to let them share the bedroom. Since we spend one-third of our lives sleeping, you can reduce your exposure somewhat by targeting the bedroom. Avoiding outdoor allergens, such as ragweed pollen, is much more difficult, unless you hermetically seal yourself up in a container. In that case, the best approach is treatment.

Q: Do over-the-counter medicines work?

A: Yes. Many are good at relieving symptoms such as congestion or itchy eyes or runny nose. But they often have side effects, and it’s important not to overuse them, so I recommend reading the label and following instructions. If you have a cough along with congestion and itchy eyes, it’s wise to see a doctor. A cough can be a sign of asthma. If you try over-the-counter drugs and they aren’t helping, see your doctor. That’s especially important for children with symptoms of allergic rhinitis, since we know that treating the condition can greatly lessen the risk of going on to develop asthma.

Q: What about prescription drug options?

A: There are several classes of prescription medications, with more and more emerging out of new research. Antihistamines block the histamine receptor on mast cells, which are the main culprits in allergic reactions. They are very effective at treating the symptoms.

Another newer class of drugs, called anti-leukotrienes, targets another substance involved in allergic responses. Mast cell stabilizers have also been developed that help keep these cells from breaking down and releasing allergic mediators. Probably the most effective medication is topical steroid nasal spray, such as Flonase, Nasonax and Rhinocort. These contain steroids that remain on the surface of cells, decreasing a huge number of inflammatory responses associated with allergic rhinitis. Because corticosteroid nasal sprays take a while to take effect, we usually recommend starting them before allergy season begins.

Immunotherapy offers another alternative, especially when medication doesn’t provide complete relief. The treatment involves identifying the specific allergen and desensitizing the immune system by injecting small amounts of it under the skin over time.

Q: You’ve mentioned allergic rhinitis and asthma. What’s the connection?

A: Both are mediated by an excess of IgE, a class of antibodies. Twenty years ago we thought asthma was caused by bronchial constriction. Now we know the main cause is allergic inflammation. Inflammation needs to be controlled in order to prevent more serious problems from asthma. Allergists now use the term “unified airway” to describe a new understanding that the nose, sinuses and lungs aren’t separate systems but part of the same system. What goes on in the upper respiratory tract can exacerbate problems in the lower respiratory tract. And it’s now clear that treating inflammation in the upper respiratory tract can help prevent development of asthma.

Q: Are you excited about the prospect for new treatments under development?

A: Absolutely. There are many promising avenues of research. Purified antigens are being tested that can lead to a more rapid desensitization in immunotherapy. There’s interest in putting specific antigens onto viral vectors that will carry them directly to mast cells. Ultimately that could mean that one injection would render people nonallergic, instead of the years of immunotherapy now often required. Before long, I hope, sublingual immunotherapy, which uses antigens that dissolve under the tongue instead of injections, may be approved in the United States. It offers two important advantages. It’s very, very safe. And you don’t have to come into a doctor’s office. You can do immunotherapy yourself at home.

Questions for Your Doctor

What to Ask About Allergic Rhinitis

By Peter Jaret : NY Times Article : October 25, 2007

Confronting a new diagnosis can be frightening -- and because research changes so often, confusing. Here are some questions you may not think to ask your doctor, along with notes on why they’re important.

What’s the likely cause of my allergies?

Allergies that occur year-round are likely to be caused by something in the house or immediate environment, such as dust mites or pet dander. Seasonal allergies are more likely to be caused by pollen from ragweed, grasses or trees. Identifying your particular culprit -- or at least making an informed guess about its source -- is useful in trying to prevent allergy attacks. If you decide to have allergy shots, also called immunotherapy, your doctor will determine exactly what the allergen is by doing skin tests or a blood test.

Is there anything I can do to prevent allergies?

The best form of prevention is avoiding allergy-inducing substances. That’s easier said than done. Washing your bed sheets and vacuuming around the house regularly can lower your exposure to dust mites or animal dander. Staying inside as much as possible during allergy season can help prevent pollen-induced allergic rhinitis. Some people have gone so far as moving to another part of the country. Unfortunately, pulling up stakes usually offers only temporary respite. If you’re prone to allergic rhinitis, you’re likely to become sensitive to something in the new environment.

Should I try an over-the-counter allergy medicine?

Most allergy sufferers start by trying over-the-counter remedies. If you have a mild to moderate case of seasonal allergies, antihistamines available on drugstore shelves can help reduce inflammation. Many cause drowsiness, so use them with care. Allergy eye drops can ease the itchy watery eyes.

How long can I go on using an over-the-counter allergy medicine?

Overuse of some over-the-counter medicines can cause inflammation, triggering the same symptoms you’re hoping to treat, a condition known as rhinitis medicamentosa. With decongestants, for example, studies show the problem begins to arise after about 10 days of use.

What about prescription allergy medications?

More than three dozen prescription remedies are available. Among the most effective are corticosteroid nasal sprays, which suppress the immune reaction that causes runny noses, congestion and itchy eyes. A recent study that compared four different prescription nasal sprays found that all were equally effective, so it’s worth checking the cost. It’s important to follow the package instructions exactly, since overuse can cause inflammation.

Should I consider getting allergy shots?

Although over-the-counter and prescription medicines ease symptoms, they don’t cure allergic rhinitis. The only way to treat the underlying condition is immunotherapy, which involves exposure to controlled doses of the allergen. A 2007 review of 51 studies that included 2,971 participants found that immunotherapy is both effective -- measured by reduction in symptoms and need for allergy medicines -- and safe.

Should I consider an accelerated course of immunotherapy?

Although effective, standard immunotherapy requires multiple visits to the doctor, often over the course of several years. Some allergy clinics around the country offer a speeded up protocol called rush immunotherapy. A study involving 893 patients at the Allergy and Asthma Center in Fort Wayne, Indiana, found that rush immunotherapy offers significantly faster relief than conventional protocols of allergy shots. But because the accelerated protocol also raises the risk of a serious immune reaction, it’s essential that rush immunotherapy be done by qualified allergists.

What’s the safest and most effective treatment for children with allergic rhinitis?

Some medicines are safe; others shouldn’t be used by children. Be sure to read package inserts and always ask your doctor if you aren’t sure. Immunotherapy is considered safe for children over 2 years of age, although getting kids to submit to a treatment that involves needles may not be easy. Still, it’s important to take allergic rhinitis in children seriously, since it can lead to the development of asthma.

House Dust Tips:

If you have dust mite allergy, pay careful attention to dust-proofing your bedroom. The worst things to have in the bedroom are:

Carpets trap dust and make dust control impossible.

Reducing the amount of dust mites in your home may mean new cleaning techniques as well as some changes in furnishings to eliminate dust collectors. Water is often the secret to effective dust removal.

If you use sprays:

Controlling Cat & Dog Allergies Tips:

Actually, these are tips for controlling allergies to all the furry creatures you can’t help but cuddle.

If you or your child is allergic to furry pets, especially cats, the best way to avoid allergic reactions is to find them another home. If you are like most people who are attached to their pets, that is usually not a desirable option. There are ways, however, to help lower the levels of animal allergens in the air, which may reduce allergic reactions.

Other tips for controlling allergies:

If you have dust mite allergy, pay careful attention to dust-proofing your bedroom. The worst things to have in the bedroom are:

- Wall-to-wall carpet

- Blinds

- Down-filled blankets

- Feather pillows

- Stuffed animals

- Heating vents with forced hot air

- Dogs and cats

- Closets full of clothing

Carpets trap dust and make dust control impossible.

- Shag carpets are the worst type of carpet for people who are sensitive to dust mites.

- Vacuuming doesn’t get rid of dust mite proteins in furniture and carpeting, but redistributes them back into the room, unless the vacuum has a special HEPA (high-efficiency particulate air) filter.

- Rugs on concrete floors encourage dust mite growth.

Reducing the amount of dust mites in your home may mean new cleaning techniques as well as some changes in furnishings to eliminate dust collectors. Water is often the secret to effective dust removal.

- Clean washable items, including throw rugs, often, using water hotter than 130 degrees Fahrenheit. Lower temperatures will not kill dust mites.

- Clean washable items at a commercial establishment that uses high water temperature, if you cannot or do not want to set water temperature in your home at 130 degrees. (There is a danger of getting scalded if the water is more than 120 degrees.)

- Dust frequently with a damp cloth or oiled mop.

- Do not leave food or garbage out.

- Store food in airtight containers.

- Clean all food crumbs or spilled liquids right away.

If you use sprays:

- Do not spray in food preparation or storage areas.

- Do not spray in areas where children play or sleep.

- Limit the spray to the infested area.

- Follow instructions on the label carefully.

- Make sure there is plenty of fresh air when you spray.

- Keep the person with allergies or asthma out of the room while spraying.

Controlling Cat & Dog Allergies Tips:

Actually, these are tips for controlling allergies to all the furry creatures you can’t help but cuddle.

If you or your child is allergic to furry pets, especially cats, the best way to avoid allergic reactions is to find them another home. If you are like most people who are attached to their pets, that is usually not a desirable option. There are ways, however, to help lower the levels of animal allergens in the air, which may reduce allergic reactions.

- Bathe your cat weekly and brush it more frequently (ideally, a non-allergic person should do this).

- Keep cats out of your bedroom.

- Remove carpets and soft furnishings, which collect animal allergens.

- Use a vacuum cleaner and room air cleaners with HEPA filters.

- Wear a face mask while house and cat cleaning

Other tips for controlling allergies:

- Take a quick shower at night to clean off any pollen from your hair

- Wash and change your pillow case frequently

- Wear sunglasses when you are outdoors especially if it is windy

- Avoid touching your face and rubbing your eyes

- Use your home and car air conditioner. Remember to change the filter.

- Keep bedroom windows closed especially if near trees

- Avoid parking your car under a tree

- Medication: Claritin or Zyrtec are both available over the counter without a prescription. Take either of these once during the day and you can add either chlotrimeton 4mg or Benadryl 25mg at bedtime.

- Women should be aware that wine and certain foods can exacerbate and worsen allergies (see article below)

The CLAIM: Alcohol Worsens Allergies

By Anahad O'Connor : NY Times Article : April 19, 2010

THE FACTS:

Sniffling, sneezing and struggling through allergy season this year?

You may want to lay off alcohol for a while. Studies have found that alcohol can cause or worsen the common symptoms of asthma and hay fever, like sneezing, itching, headaches and coughing.

But the problem is not always the alcohol itself. Beer, wine and liquor contain histamine, produced by yeast and bacteria during the fermentation process. Histamine, of course, is the chemical that sets off allergy symptoms. Wine and beer also contain sulfites, another group of compounds known to provoke asthma and other allergy-like symptoms.

In one study in Sweden in 2005 , scientists looked at thousands of people and found that compared with the general population, those with diagnoses of asthma, bronchitis and hay fever were far more likely to experience sneezing, a runny nose and “lower-airway symptoms” after having a drink. Red wine and white wine were the most frequent triggers, and women, for unknown reasons, were about twice as likely to be affected as men.

Another study of thousands of women published in the journal Clinical and Experimental Allergy in 2008 found that having more than two glasses of wine a day almost doubles the risk of allergy symptoms, even among women who were free of seasonal and perennial allergies at the start of the study.

It helps to be on the lookout for other foods that either contain or release histamine, like aged cheeses, pickled or fermented products and yeast-containing foods, like bread, cider and grapes.

THE BOTTOM LINE :

Drinking alcohol can cause or worsen allergies, particularly in women.

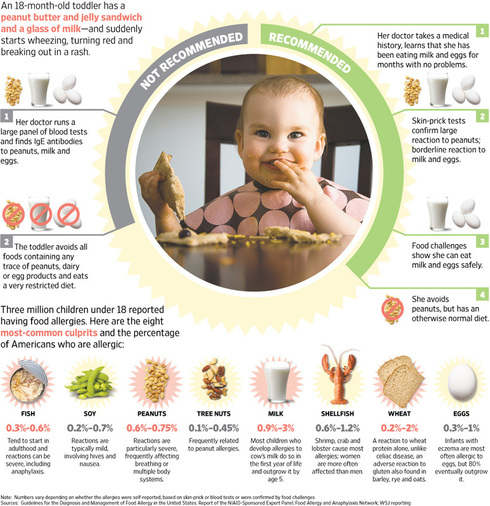

Food Allergies Less Common Than Believed

By Gina Kolata : NY Times Article : May 11, 2010

Many who think they have food allergies actually do not.

A new report, commissioned by the federal government, finds the field is rife with poorly done studies, misdiagnoses and tests that can give misleading results.

While there is no doubt that people can be allergic to certain foods, with reproducible responses ranging from a rash to a severe life-threatening reaction, the true incidence of food allergies is only about 8 percent for children and less than 5 percent for adults, said Dr. Marc Riedl, an author of the new paper and an allergist and immunologist at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Yet about 30 percent of the population believe they have food allergies. And, Dr. Riedl said, about half the patients coming to his clinic because they had been told they had a food allergy did not really have one.

Dr. Riedl does not dismiss the seriousness of some people’s responses to foods. But, he says, “That accounts for a small percentage of what people term ‘food allergies.’ ”

Even people who had food allergies as children may not have them as adults. People often shed allergies, though no one knows why. And sometimes people develop food allergies as adults, again for unknown reasons.

For their report, Dr. Riedl and his colleagues reviewed all the papers they could find on food allergies published between January 1988 and September 2009 — more than 12,000 articles. In the end, only 72 met their criteria, which included having sufficient data for analysis and using more rigorous tests for allergic responses.

“Everyone has a different definition” of a food allergy, said Dr. Jennifer J. Schneider Chafen of the Department of Veterans Affairs’ Palo Alto Health Care System in California and Stanford’s Center for Center for Primary Care and Outcomes Research, who was the lead author of the new report. People who receive a diagnosis after one of the two tests most often used — pricking the skin and injecting a tiny amount of the suspect food and looking in blood for IgE antibodies, the type associated with allergies — have less than a 50 percent chance of actually having a food allergy, the investigators found.

One way to see such a reaction is with what is called a food challenge, giving people a suspect food disguised so they do not know if they are eating it or a placebo food. If the disguised food causes a reaction, the person has an allergy.

But in practice, most doctors are reluctant to use food challenges, Dr. Riedl said. They believe the test to be time consuming, and worry about asking people to consume a food, like peanuts, that can elicit a frightening response.

The paper, to be published Wednesday in The Journal of the American Medical Association, is part of a large project organized by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases to try to impose order on the chaos of food allergy testing. An expert panel will provide guidelines defining food allergies and giving criteria to diagnose and manage patients. They hope to have a final draft by the end of June.

“We were approached as in a sense the honest broker who could get parties together to look at this question,” said Dr. Matthew J. Fenton, who oversees the guidelines project for the allergy institute.

Authors of the new report — and experts on the guidelines panel — say even accepted dogma, like the idea that breast-fed babies have fewer allergies or that babies should not eat certain foods like eggs for the first year of life, have little evidence behind them.

Part of the confusion is over what is a food allergy and what is a food intolerance, Dr. Fenton said. Allergies involve the immune system, while intolerances generally do not. For example, a headache from sulfites in wine is not a food allergy. It is an intolerance. The same is true for lactose intolerance, caused by the lack of an enzyme needed to digest sugar in milk.

And other medical conditions can make people think they have food allergies, Dr. Fenton said. For example, people sometimes interpret acid reflux symptoms after eating a particular food as an allergy.

The chairman of the guidelines project, Dr. Joshua Boyce, an associate professor of medicine at Harvard and an allergist and pediatric pulmonologist, said one of the biggest misconceptions some doctors and patients have is that a positive test for IgE antibodies to a food means a person is allergic to that food. It is not necessarily so, he said.

During development, he said, the immune system tends to react to certain food proteins, producing IgE antibodies. But, Dr. Boyce said, “these antibodies can be transient and even inconsequential.”

“There are plenty of individuals with IgE antibodies to various foods who don’t react to those foods at all,” Dr. Boyce said.

The higher the levels of IgE antibodies to a particular food, the greater the likelihood the person will react in an allergic way. But even then, the antibodies do not necessarily portend a severe reaction, Dr. Boyce said. Antibodies to some foods, like peanuts, are much more likely to produce a reaction than ones to other foods, like wheat or corn or rice. No one understands why.

The guidelines panel hopes its report will lead to new research as well as clarify the definition and testing for food allergies.

But for now, Dr. Fenton said, doctors should not use either the skin-prick test or the antibody test as the sole reason for thinking their patients have a food allergy.

“By themselves they are not sufficient,” Dr. Fenton said.

By Gina Kolata : NY Times Article : May 11, 2010

Many who think they have food allergies actually do not.

A new report, commissioned by the federal government, finds the field is rife with poorly done studies, misdiagnoses and tests that can give misleading results.

While there is no doubt that people can be allergic to certain foods, with reproducible responses ranging from a rash to a severe life-threatening reaction, the true incidence of food allergies is only about 8 percent for children and less than 5 percent for adults, said Dr. Marc Riedl, an author of the new paper and an allergist and immunologist at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Yet about 30 percent of the population believe they have food allergies. And, Dr. Riedl said, about half the patients coming to his clinic because they had been told they had a food allergy did not really have one.

Dr. Riedl does not dismiss the seriousness of some people’s responses to foods. But, he says, “That accounts for a small percentage of what people term ‘food allergies.’ ”

Even people who had food allergies as children may not have them as adults. People often shed allergies, though no one knows why. And sometimes people develop food allergies as adults, again for unknown reasons.

For their report, Dr. Riedl and his colleagues reviewed all the papers they could find on food allergies published between January 1988 and September 2009 — more than 12,000 articles. In the end, only 72 met their criteria, which included having sufficient data for analysis and using more rigorous tests for allergic responses.

“Everyone has a different definition” of a food allergy, said Dr. Jennifer J. Schneider Chafen of the Department of Veterans Affairs’ Palo Alto Health Care System in California and Stanford’s Center for Center for Primary Care and Outcomes Research, who was the lead author of the new report. People who receive a diagnosis after one of the two tests most often used — pricking the skin and injecting a tiny amount of the suspect food and looking in blood for IgE antibodies, the type associated with allergies — have less than a 50 percent chance of actually having a food allergy, the investigators found.

One way to see such a reaction is with what is called a food challenge, giving people a suspect food disguised so they do not know if they are eating it or a placebo food. If the disguised food causes a reaction, the person has an allergy.

But in practice, most doctors are reluctant to use food challenges, Dr. Riedl said. They believe the test to be time consuming, and worry about asking people to consume a food, like peanuts, that can elicit a frightening response.

The paper, to be published Wednesday in The Journal of the American Medical Association, is part of a large project organized by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases to try to impose order on the chaos of food allergy testing. An expert panel will provide guidelines defining food allergies and giving criteria to diagnose and manage patients. They hope to have a final draft by the end of June.

“We were approached as in a sense the honest broker who could get parties together to look at this question,” said Dr. Matthew J. Fenton, who oversees the guidelines project for the allergy institute.

Authors of the new report — and experts on the guidelines panel — say even accepted dogma, like the idea that breast-fed babies have fewer allergies or that babies should not eat certain foods like eggs for the first year of life, have little evidence behind them.

Part of the confusion is over what is a food allergy and what is a food intolerance, Dr. Fenton said. Allergies involve the immune system, while intolerances generally do not. For example, a headache from sulfites in wine is not a food allergy. It is an intolerance. The same is true for lactose intolerance, caused by the lack of an enzyme needed to digest sugar in milk.

And other medical conditions can make people think they have food allergies, Dr. Fenton said. For example, people sometimes interpret acid reflux symptoms after eating a particular food as an allergy.

The chairman of the guidelines project, Dr. Joshua Boyce, an associate professor of medicine at Harvard and an allergist and pediatric pulmonologist, said one of the biggest misconceptions some doctors and patients have is that a positive test for IgE antibodies to a food means a person is allergic to that food. It is not necessarily so, he said.

During development, he said, the immune system tends to react to certain food proteins, producing IgE antibodies. But, Dr. Boyce said, “these antibodies can be transient and even inconsequential.”

“There are plenty of individuals with IgE antibodies to various foods who don’t react to those foods at all,” Dr. Boyce said.

The higher the levels of IgE antibodies to a particular food, the greater the likelihood the person will react in an allergic way. But even then, the antibodies do not necessarily portend a severe reaction, Dr. Boyce said. Antibodies to some foods, like peanuts, are much more likely to produce a reaction than ones to other foods, like wheat or corn or rice. No one understands why.

The guidelines panel hopes its report will lead to new research as well as clarify the definition and testing for food allergies.

But for now, Dr. Fenton said, doctors should not use either the skin-prick test or the antibody test as the sole reason for thinking their patients have a food allergy.

“By themselves they are not sufficient,” Dr. Fenton said.

Food Allergy Advice for Kids: Don't Delay Peanuts, Eggs

Sumathi Reddy : WSJ : March 4, 2013

Parents trying to navigate the confusing world of children's food allergies now have more specific advice to consider. Highly allergenic foods such as peanut butter, fish and eggs can be introduced to babies between 4 and 6 months and may even play a role in preventing food allergies from developing.

These recommendations regarding children and food allergies—a rising phenomenon that researchers don't fully understand—come from the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology in a January article in the Journal of Allergy & Clinical Immunology: In Practice. The AAAAI's Adverse Reactions to Foods Committee outlined how and when to introduce highly allergenic foods, which include wheat, soy, milk, tree nuts, and shellfish.

The recommendations are a U-turn from 2000, when the American Academy of Pediatrics issued guidelines that children should put off having milk until age 1, eggs until 2 and peanuts, shellfish, tree nuts and fish until 3. In 2008, the AAP revised its guidelines, citing little evidence that such delays prevent the development of food allergies, but it didn't say when and how to introduce such foods.

Food allergies affect an estimated 5% of children under the age of 5 in the U.S., according to the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, part of the National Institutes of Health. The prevalence of a food allergy for children under 18 increased by 18% from 1997 to 2007.

"There's been more studies that find that if you introduce them early it may actually prevent food allergy," said David Fleischer, co-author of the article and a pediatric allergist at National Jewish Health in Denver. "We need to get the message out now to pediatricians, primary-care physicians and specialists that these allergenic foods can be introduced early."

Dr. Fleischer said more study results are needed to conclusively determine whether early introduction will in fact lead to lower food-allergy rates and whether they should be recommended as a practice.

The first trials to split children into groups, with some eating highly allergenic foods early on and others delaying, are continuing in the United Kingdom and Australia with some preliminary results expected to be out next year. This type of trial with children is rare and the results are highly anticipated.

One theory to explain why early introduction is important holds that if babies aren't exposed early enough to certain foods, their immune systems will treat them as foreign substances and attack them, resulting in an allergy.

"The body has to be trained in the first year of life," says Katie Allen, a professor and allergist at the Murdoch Childrens Research Institute at Royal Children's Hospital in Australia. (The institute was founded in part by the late Dame Elisabeth Murdoch, mother of Rupert Murdoch, who is chairman of News Corp., which owns The Wall Street Journal.) "We think there's a critical window, probably around 4 to 6 months, when the child first starts to eat solids," she says.

Another possible explanation from some experts for the increase in allergies: As westernized countries have become more hygienic, children don't have the same exposure to germs, which affects the development of the immune system.

Dr. Allen believes there may be a link between food allergies and vitamin D. In a study out this week in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, researchers took blood samples from more than 5,000 babies and found that those with low vitamin D levels were three times more likely to have a food allergy.

Food-allergy reactions range from hives and eczema to asthma, vomiting and anaphylaxis, a life-threatening reaction in which the body's major systems quickly shut down. A 2011 prevalence study in the journal Pediatrics found that 39% of children with food allergies have a history of severe reactions.

The new recommendations include introducing highly allergenic foods after typical first foods have been eaten and tolerated, such as rice cereal, fruits and vegetables. They suggest children be fed the foods at home and in gradually increasing amounts. The AAAAI recommendations cited about half-a-dozen studies in making its new guidelines.

One observational study compared Jewish children in the United Kingdom with those in Israel, where the peanut-allergy rate is low. The 2008 study of more than 5,000 children in each country in the Journal of Allergy Clinical Immunology found the rate of peanut allergies among the U.K. children was 10 times that of those in Israel. Gideon Lack, a professor of paediatric allergy at King's College London, said the researchers followed up with surveys given to the parents of about 100 infants hundred in each country. They found that popular snacks with peanuts were given to Israeli babies often before they were 6 months of age, whereas the majority of babies in the United Kingdom didn't taste peanut products until after the age of 1.

Dr. Lack is in the midst of the much-anticipated, randomized controlled trial in the U.K., which is following 640 children with a high risk of allergy—determined by eczema—from infancy to the age of 5. Half of the children are consuming at least 24 grams of peanuts three times a week, while the others have none. About two-thirds of the children are now 5 and receiving peanut-allergy testing. Preliminary results are expected next year.

Some experts are critical of the observational studies cited in the recommendations. "The evidence that has come up is of great interest but it's all either anecdotal or epidemiological and not the intervention studies that are going on right now that will lead to answers in the next three years," said Robert Wood, director of Pediatric Allergy and Immunology at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

Dr. Wood said he tells parent they don't need to feel pressured to do an early introduction. "You can do whatever you want because we're not sure what makes a difference," he said.

When food allergies first started becoming more common in the 1990s, the prevailing thought among experts was that delaying introduction of such foods would reduce the prevalence of food allergies.

"As these guidelines were implemented we've seen a paradoxical increase in foods allergies in young children, especially with peanut allergies," said Anna Nowak-Wegrzyn, associate professor of pediatrics at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai Hospital.

The new recommendations from the AAAAI committee say an allergist should be consulted in cases when an infant has eczema that is difficult to control, or an existing food allergy. For children who have a sibling with a peanut allergy—and have a 7% greater risk of a peanut allergy—parents may request an evaluation but the risks of introducing peanut at home in infancy are low, the recommendations noted.

Debby Beerman, a Chicago-area mom, has two boys, ages 4 and 3, with a number of allergies.

"It scares me to think that you would give the food to a child at such a young age when they can't really express that they're not feeling well or they're in distress or something's not right," said Ms. Beerman, a member of the Food Allergy Research & Education, an advocacy group. "But if the data was there to support it, I think we would all do anything we could to try and avoid this.

Sumathi Reddy : WSJ : March 4, 2013

Parents trying to navigate the confusing world of children's food allergies now have more specific advice to consider. Highly allergenic foods such as peanut butter, fish and eggs can be introduced to babies between 4 and 6 months and may even play a role in preventing food allergies from developing.

These recommendations regarding children and food allergies—a rising phenomenon that researchers don't fully understand—come from the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology in a January article in the Journal of Allergy & Clinical Immunology: In Practice. The AAAAI's Adverse Reactions to Foods Committee outlined how and when to introduce highly allergenic foods, which include wheat, soy, milk, tree nuts, and shellfish.

The recommendations are a U-turn from 2000, when the American Academy of Pediatrics issued guidelines that children should put off having milk until age 1, eggs until 2 and peanuts, shellfish, tree nuts and fish until 3. In 2008, the AAP revised its guidelines, citing little evidence that such delays prevent the development of food allergies, but it didn't say when and how to introduce such foods.

Food allergies affect an estimated 5% of children under the age of 5 in the U.S., according to the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, part of the National Institutes of Health. The prevalence of a food allergy for children under 18 increased by 18% from 1997 to 2007.

"There's been more studies that find that if you introduce them early it may actually prevent food allergy," said David Fleischer, co-author of the article and a pediatric allergist at National Jewish Health in Denver. "We need to get the message out now to pediatricians, primary-care physicians and specialists that these allergenic foods can be introduced early."

Dr. Fleischer said more study results are needed to conclusively determine whether early introduction will in fact lead to lower food-allergy rates and whether they should be recommended as a practice.

The first trials to split children into groups, with some eating highly allergenic foods early on and others delaying, are continuing in the United Kingdom and Australia with some preliminary results expected to be out next year. This type of trial with children is rare and the results are highly anticipated.

One theory to explain why early introduction is important holds that if babies aren't exposed early enough to certain foods, their immune systems will treat them as foreign substances and attack them, resulting in an allergy.

"The body has to be trained in the first year of life," says Katie Allen, a professor and allergist at the Murdoch Childrens Research Institute at Royal Children's Hospital in Australia. (The institute was founded in part by the late Dame Elisabeth Murdoch, mother of Rupert Murdoch, who is chairman of News Corp., which owns The Wall Street Journal.) "We think there's a critical window, probably around 4 to 6 months, when the child first starts to eat solids," she says.

Another possible explanation from some experts for the increase in allergies: As westernized countries have become more hygienic, children don't have the same exposure to germs, which affects the development of the immune system.

Dr. Allen believes there may be a link between food allergies and vitamin D. In a study out this week in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, researchers took blood samples from more than 5,000 babies and found that those with low vitamin D levels were three times more likely to have a food allergy.

Food-allergy reactions range from hives and eczema to asthma, vomiting and anaphylaxis, a life-threatening reaction in which the body's major systems quickly shut down. A 2011 prevalence study in the journal Pediatrics found that 39% of children with food allergies have a history of severe reactions.

The new recommendations include introducing highly allergenic foods after typical first foods have been eaten and tolerated, such as rice cereal, fruits and vegetables. They suggest children be fed the foods at home and in gradually increasing amounts. The AAAAI recommendations cited about half-a-dozen studies in making its new guidelines.