- RETIREMENT ANNOUNCEMENT

- HOME PAGE

- "MYCHART" the new patient portal

- BELMONT MEDICAL ASSOCIATES

- MOUNT AUBURN HOSPITAL

- EMERGENCIES

- PRACTICE PHILOSOPHY

- MY RESUME

- TELEMEDICINE CONSULTATION

- CONTACT ME

- LAB RESULTS

- ePRESCRIPTIONS

- eREFERRALS

- RECORD RELEASE

- MEDICAL SCRIBE

- PHYSICIAN ASSISTANT (PA)

- Medicare Annual Wellness Visit

- Case management/Social work

- Quality Care Measures

- Emergency closing notice

- FEEDBACK

- Talking to your doctor

- Choosing..... and losing a doctor

- INDEX A - Z

- ALLERGIC REACTIONS

- Alternative Medicine

- Alzheimer's Disease

- Bladder Problems

- Blood disorders

- Cancer Concerns

- GENETIC TESTING FOR HEREDITARY CANCER

- Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

- Controversial Concerns

- CPR : Learn and save a life

- CRP : Inflammatory marker

- Diabetes Management

- Dizziness, Vertigo,Tinnitus and Hearing Loss

- EXERCISE

- FEMALE HEALTH

-

GASTROINTESTINAL topics

- Appendicitis

- BRAT diet

- Celiac Disease or Sprue

- Crohn's Disease

- Gastroenterologists for Colon Cancer Screening

- Colonoscopy PREP

- Constipation

- Gluten sensitivity, but not celiac disease

- Heartburn and GERD

- Hemorrhoids and Anal fissure

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- NASH : Non Alcoholic Steato Hepatitis

- FEET PROBLEMS

- HEART RELATED topics

-

INFECTIOUS DISEASES

- Antibiotic Resistance

- Cat bites >

- Clostridia difficile infection - the "antibiotic associated germ"

- CORONA VIRUS

- Dengue Fever and Chikungunya Fever

- Food borne illnesses

- Shingles Vaccine

- Hepatitis B

- Hepatitis C

- Herpes

- Influenza

- Helicobacter pylori - the "ulcer germ"

- HIV Screening

- Lyme and other tick borne diseases

- Measles

- Meningitis

- MRSA (Staph infection)

- Norovirus

- Sexually Transmitted Diseases

- Shingles (Herpes Zoster)

- Sinusitis

- West Nile Virus

- Whooping Cough (Pertussis)

- Zika virus and pregnancy

- INSURANCE related topics

- KIDNEY STONES

- LEG CRAMPS

- LIBRARY for patients

- LIFE DECISIONS

- MALE HEALTH

- Medication/Drug side effects

- MEDICAL MARIJUANA

- MENTAL HEALTH

- Miscellaneous Articles

-

NUTRITION - EXERCISE - WEIGHT

- Cholesterol : New guidelines for treatment

- Advice to lower your cholesterol

- Cholesterol : Control

- Cholesterol : Raising your HDL Level

- Exercise

- Food : Making Smart Choices

- Food : Making Poor Choices

- Food : Grape Fruit and Drug Interaction

- Food : Vitamins, Minerals and Supplements

- Omega 3 fatty acids

- Vitamin B12 deficiency

- Vitamin D

- Weight Loss

- ORTHOPEDICS

- PAIN

- PATIENTS' RIGHTS

- SKIN

- SLEEP

- SMOKING

- STROKE

- THYROID

- SUBSTANCE ABUSE

- Travel and Vaccination

- TREMOR

- Warfarin Anticoagulation

- OTHER STUFF FOLLOWS

- Fact or Opinion?

- Hippocratic Oath

- FREE ADVICE.......for what its worth!

- LAUGHTER.....is the best medicine

- Physicians Pet Peeves

- PHOTO ALBUM - its not all work!

- Cape Town, South Africa

- Tribute page

- The 100 Club

- Free Wi-Fi

Celiac Disease

or Gluten Sensitive Enteropathy

Celiac Disease, a Common, but Elusive, Diagnosis

By Jane E. Brody : NY Times : September 29, 2014

The trouble for Daniel Tully, then 12 and an excellent student and athlete in Brooklyn, began 20 months ago, when he developed what seemed like a virus that kept recurring, each time sending him to bed and keeping him from school for a week.

In January, he came down with an intestinal bug from which he never seemed to recover. He developed severe headaches whenever he tried to read or concentrate, became extremely weak, mentally foggy and unable to go to school at all. He vomited violently after meals, lost weight, and eventually could not walk unaided.

“I had to carry him to the bathroom,” recalled his father, Ed Tully.

When a child develops such a devastating constellation of symptoms, you’d think his doctors might consider testing for celiac disease, an autoimmune reaction to dietary gluten that can destroy the small intestine. Awareness of the problem has never been greater.

But even in the most sophisticated medical settings, the diagnosis can be missed or the tests done incorrectly. Over four days in a local hospital, Daniel’s doctors performed an intestinal biopsy. But only two samples were taken, which missed the severe damage in his small intestine.

He finally saw a pediatric immunologist and was given the blood test specific for celiac disease. It was unequivocally positive. The diagnosis was confirmed by a second intestinal biopsy, this time with the recommended six or more samples.

Daniel began a strict gluten-free diet five months ago and is gradually recovering. With intensive physical therapy and a diet rich in meat, he is regaining lost strength, weight and stamina. His doctors say it may take a year, but he eventually will achieve normal growth — as long as he sticks religiously to the diet.

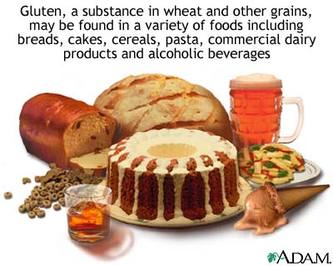

Gluten is a protein in grains like wheat, rye and barley that contains gliadin peptides. In people with celiac disease, these can trigger an autoimmune reaction that damages the villi, tiny projections lining the small intestine that absorb nutrients from food into the body. Like Daniel, people with celiac disease must avoid wheat, rye or barley, or any of the thousands of products or ingredients made from these grains. Some must also abstain from oats.

The disease runs in families: Some of Daniel’s first and second cousins have it, and Daniel’s younger sister is now being tested for it.

First-degree relatives of someone with celiac disease should also be tested for it, even if they have no symptoms. If another person in the immediate family has the disease, second-degree relatives should be tested, Dr. Joseph A. Murray, a gastroenterologist at the Mayo Clinic, said in an interview.

“Celiac disease is now five times more common than it was 50 years ago, and that’s not just the result of better diagnoses,” said Dr. Murray, who is also editor of “Mayo Clinic Going Gluten Free,” to be published in November. “We looked at old stored blood samples, and that showed a real increase in incidence.”

For reasons unknown, celiac disease now affects one in 100 Caucasians, Dr. Murray said. It does occur in other racial groups, but is believed to be much less common.

Hygienic extremes may be to blame for the increase: Overzealous cleanliness has been linked to a rise in autoimmune diseases. But experts speculate the increase also may have to do with how grains are bred these days, or the overreliance on formula to feed infants. Although traditionally considered a disease that shows up in childhood, people of all ages may develop it. One person I know was diagnosed in his 50s, another in her 60s.

But the overwhelming majority of people with celiac disease remain undiagnosed. The most recent data show that only 17 percent of Americans with the disease know they have it. Those who are not avoiding gluten risk developing a host of debilitating, sometimes fatal complications, including cancer.

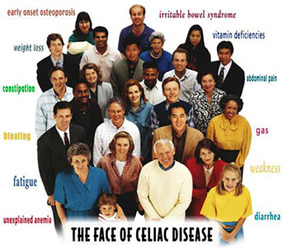

A main reason for this lag in detection is the long and confusing list of signs and symptoms, some of which may be mild enough to be easily ignored or attributed to another condition, like irritable bowel syndrome or an allergy.

Abdominal pain and bloating are the most common signs. But according to a recent review in JAMA Pediatrics, possible symptoms include chronic or intermittent constipation; vomiting;loss of appetite; weight loss (or, in children, growth failure); fatigue;iron deficiency anemia; abnormal dental enamel; mouth ulcers;arthritis and joint pain; bone loss and fractures; short stature; delayed puberty; unexplained infertility and miscarriage; recurring headaches; loss of feeling in hands and feet; poor coordination and unsteadiness; seizures; depression; hallucinations, anxiety and panic attacks. “Doctors have to raise their index of suspicion,” Dr. Murray said. “At least half of patients don’t have diarrhea. It can present in so many ways.”

About one-third of his patients had asked doctors on their own for testing, he added. It is critically important to be tested before going on a gluten-free diet, which can disguise the intestinal damage characteristic of the condition. Those already eating a restricted diet would have to return to gluten (say, eating two slices of bread a day for two weeks) for the test to be accurate.

Avoiding gluten has become easier in recent years as companies have loaded store shelves with gluten-free foods. A new Food and Drug Administration rule stipulates that any food labeled gluten-free must contain less than 20 parts per million of gluten, considered harmless for most celiac patients.

All uncoated, unprocessed meats, poultry, fish, beans, nuts, vegetables and fruits are naturally gluten-free, and can be labeled as such. But to be safe, consumers must read labels diligently to spot hidden hazards, like hydrolyzed vegetable protein, and learn to ask detailed questions about how food is prepared when dining out. Even reusing water in which wheat pasta is cooked can be hazardous.

KEY CLINICAL POINTS IN CELIAC DISEASE

• Once considered a gastrointestinal disorder that mainly affects white children, celiac disease is now known to affect persons of different ages, races, and ethnic groups, and it may be manifested without any gastrointestinal symptoms.

• Measurement of IgA anti–tissue transglutaminase antibodies is the preferred initial screening test for celiac disease because of its high sensitivity and specificity, but it performs poorly in patients with IgA deficiency (which is more common in patients with celiac disease than in the general population).

• The diagnosis is confirmed by means of upper endoscopy with duodenal biopsy, although recent guidelines suggest that biopsy may not be necessary in selected children with strong clinical and serologic evidence of celiac disease.

• Given the undisputable role of gluten in causing celiac disease enteropathy, the cornerstone of treatment is the implementation of a strict gluten-free diet for life.

• Gluten sensitivity may occur in the absence of celiac disease, and a definitive diagnosis should be made before implementing a lifelong gluten-free diet.

The Overlooked Diagnosis of Celiac Disease

By Carolyn Sayre : NY Times Article : December 16, 2009

It took three decades to figure out what was making Donna Sawka so sick. Her symptoms — bloating, chronic diarrhea and weight loss — began early in childhood, and they only became worse as she aged.

Nine years ago, after developing severe anemia, a specialist told Ms. Sawka that she had celiac disease. The digestive disorder causes damage to the small intestine when gluten, a protein found in wheat, barley and rye, is ingested. People with the disease need to follow a strict gluten-free diet for the rest of their lives to avoid serious complications like osteoporosis and lymphoma, an immune system cancer.

Ms. Sawka, 48, of Fairless Hills, Pa., said she “was overwhelmed” upon learning she had the disease.

“I kept thinking about everything I wouldn’t be able to eat,” she went on. “I couldn’t even receive communion at church.”

Ms. Sawka’s reaction is a familiar one at the support group she attends. It takes the average patient 10 years to receive a diagnosis. And according to specialists, they are the lucky ones. Studies show that 3 million Americans, or 1 in every 133 people, have celiac disease. But 95 percent of them have yet to learn they have it, according to the National Institutes of Health.

“The entire disease and all of its manifestations are incredibly underdiagnosed,” said Dr. Charles Bongiorno, the chief of the division of gastroenterology and hepatology at the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey. “Patients often have it for a decade or two before they are diagnosed.”

Celiac disease is often difficult to detect because the symptoms vary so widely from person to person. Ten years ago, the medical community thought it was a rare disorder that affected only 1 in every 10,000 people, primarily children who had digestive problems and failure to thrive.

But physicians now know that the disease is much more common. Most patients never experience the so-called classic symptoms: bloating, chronic diarrhea and stomach upset. Instead, the signs are often as nebulous as anemia, infertility and osteoporosis.

“It’s a problem,” said Dr. Ritu Verma, section chief of gastroenterology, hepatology and nutrition and director of the Children’s Celiac Center at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. “The majority of patients do not have the traditional signs and symptoms. If someone’s only presenting symptom is anemia, physicians will think of a hundred other things before they think of celiac disease.”

As a result, the condition is also commonly mistaken for other ailments. Ms. Sawka, for one, was told she had everything from irritable bowel syndrome to lupus to an allergic reaction from a spider bite before celiac disease was confirmed.

Part of the problem is also a lack of education among physicians, particularly internists. According to Dr. Bongiorno, most primary care physicians are simply unaware of new research that shows the disease is common and can manifest itself in unusual ways.

“They think it is an exotic malady,” he explained. “That persistent fallacy causes a less-than-appropriate effort to order the right blood tests and refer to gastroenterologists for care.”

In 2006, the National Institutes of Health started a campaign to raise awareness of the disease among both the general public and physicians. A goal was to increase rates of diagnosis because, unlike many ailments, there is a definitive way to stop celiac disease from progressing once it is recognized.

“The vast majority of cases experience a complete remission from symptoms once they are diagnosed and go on a gluten-free diet,” said Dr. Stefano Guandalini, director of the University of Chicago Celiac Disease Center. “So essentially, you have no disease. That is what makes it all the more important to be diagnosed.”

And there is no better time to be on a gluten-free diet. In 2008, 832 gluten-free products entered the market, nearly 6 times the number that debuted in 2003. Last year, gluten-free even emerged as a fad diet in the general population.

“The quantity and quality of these products is amazing,” said Dr. Alessio Fasano, the medical director of the Center for Celiac Research at the University of Maryland Medical Center.

Dr. Fasano said gluten-free products used to taste like cardboard but had significantly improved in recent years. “The only problem,” he said, “is that they cost five or six times more than their normal counterparts.”

Researchers are also beginning to experiment with drugs that may be able to block the immune response to gluten, much like a lactate pill. If the clinical trials are successful, individuals with celiac disease may be someday able to ingest small amounts of gluten.

Until then, the gluten-free diet is working for patients like Ms. Sawka. “I am perfect now,” she said after 35 years of feeling sick. “Every system in my body was in an uproar, and then everything just quieted down.”

Expert Q & A

Effective Management of Celiac Disease

By Carolyn Sayre : New York Times Article : December 16, 2009

Dr. Ritu Verma is the section chief of gastroenterology, hepatology and nutrition and director of the Children’s Celiac Center at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

Q: You have two children with celiac disease. Did that inspire your work at the center?

A: No. I have been a gastroenterologist for much longer than that. I think it is one of the most fascinating diseases. I used to say to my patients, “If God ever said you have to have a disease, I would say give me celiacs.” There is an end point to it. If you change your diet, your intestines and body are as good as someone who does not have it. There is no other condition in medicine that you can cure — and you can call it a cure — just by changing your diet. There are no needles involved. If you think about it, it is probably the easiest disease to have.

Q: How do patients with celiac disease control their condition through diet?

A: They have to go on a gluten-free diet. That means a diet that does not have any wheat, barley or rye in it. You have to read labels for anything that goes in your mouth every time, because the manufacturer may switch ingredients on you. It is not just food — it is also medicine and cosmetics and, for little children, even Play-Doh and things like that. I had one patient who couldn’t figure out why her blood tests weren’t improving. Finally, she realized her shampoo had gluten in it, and she was ingesting it when she bit her nails.

Q: What can someone with celiac disease eat?

A: There is a lot that they can eat. They can eat any fruits, vegetables or meat; also corn, potatoes, beans, lentils, soymilk and eggs. Most people will eat a lot of Indian and Mediterranean food. Spanish food is also popular, because you can have the corn tortillas. Really, it is just the regular pasta, the bread and the cookies that you can’t have.

Q: Can people with celiac disease eat out at restaurants?

A: Many restaurants now have gluten-free menus. We have done a lot of education with restaurants through the National Foundation for Celiac Awareness and their Appetite for Awareness campaign.

Q: How big of a problem is cross-contamination for people trying to maintain a gluten-free diet?

A: Keeping the diet is easy as far as reading labels, but when you go out to eat you have to talk to the chef and make sure there is no cross-contamination. For example, if you went out to eat for breakfast you would probably think that eggs were safe, but some places use flour to make an omelet. You have to quiz the chef about every ingredient. It is overwhelming, especially when you are just diagnosed.

Q: The number of gluten-free products has increased significantly over the last five years. What has changed?

A: It is an increase in awareness. Five years ago, the National Institutes of Health had this whole session on celiac disease. From there, the North American Society for Pediatric Gastrointerology, Hepatology, and Nutrition started a series of lectures for physicians. Then came the legislation last year that foods would have to be labeled. Awareness has really been building.

Q: Gluten-free and wheat-free labels seem similar, but they mean very different things. Do patients often confuse the two?

A: Yes. That is where the recent labeling became a little dangerous. Foods would say “this does not contain wheat,” but it didn’t say anything about barley and rye. And then there is a whole controversy about oats. So a lot of people would say this is wheat-free, it must be gluten-free. A lot of education is needed about this. Gluten-free is wheat-free, but not the other way around.

Q: Is it important for newly diagnosed patients to work with a dietician?

A: Yes. Patients who are diagnosed and try to figure it out by themselves have a very difficult time and often give up. It is almost impossible to get the proper training yourself. It is also an extremely expensive diet. Going to the store and seeing a loaf of bread costs $8 is enough to make some people say “forget it” or go partially gluten-free, which can make themselves feel better. Dietitians and support groups are really the key to success for people with celiac disease. It is an overwhelming condition.

Q: What happens when patients stop eating gluten?

A: When you have celiac disease, there is damage to the lining of your small intestine. There is something called the villi, these finger-like projections that you look at under the microscope. In people who have celiac disease, the gluten damages the lining of the small intestine and the villi. Once you go on a gluten-free diet, these villi actually start healing and forming back again. If you do another biopsy on someone who has been on a gluten-free diet and is doing well, the small intestine and the villi will be back to normal.

Q: How strictly do patients need to follow the diet if the small intestine and villi will heal after a few months on a gluten-free diet?

A: When you start eating the gluten again, it affects your immune system. So your intestines will heal, but your immune system gets primed. It goes haywire and starts sending out these signals to the rest of your body. Your thyroid and other parts of your body can be affected, and those don’t heal. So it is not just a matter of healing your intestine; it is also a matter of healing your body and protesting this long-term risk of lymphoma that you can develop years down the line. The commitment has to be for life. So you can imagine how tough that is for patients, especially when they start feeling better. How many of us finish a course of antibiotics and when we start feeling better say, “O.K., I am done.”

Q: Physicians used to think celiac disease occurred mostly in childhood. Is any group particularly at risk?

A: A lot of people are diagnosed when they are older now. That is because they are not presenting with the traditional symptoms that young people had. It can really be in any ethnic background. It used to be someone who is Irish or French Canadian, but that is another myth taught in medical schools. It was thought that it was seen in boys more than girls, but that is still up in the air.

Q: Are there any other ways to control celiac disease?

A: Right now, it is only diet. But there are a lot of companies coming up with pills. One of them is actually almost in Phase III trials in adults, and it is thought that it will come out in the next few years. The idea is that people who take this pill would be covered if they went out and had cross contamination. The danger to this pill, of course, is people who would go out and eat regular pizza. We have to wait and see if it is safe enough for that. Right now it is only being tested to protect against the small amount of gluten that may be in someone’s diet.

Q: Are there any efforts to make a celiac vaccine?

A: There are some people who are working on a vaccine. The problem with a vaccine is that there are many different H.L.A. (human leukocyte antigens) types associated with celiac disease, so a vaccine will not be very easy. But I know the person who is looking at the vaccine is trying to develop one for the HLA-DQ2 type, because that is the more lethal one in terms of the long-term risks of cancer.

Questions for Your Doctor

What to Ask About Celiac Disease

By Carolyn Sayre : NY Times Article : December 16, 2009

Confronting a new diagnosis can be frightening — and because research changes so often, confusing. Here are some questions you may not think to ask your doctor, along with notes on why they’re important.

What is celiac disease?

Celiac disease is a digestive condition that causes an immune reaction in the small intestine when gluten, a protein found in wheat, barley and rye, is ingested. Gluten damages the tiny hairlike protrusions known as villi, which line the small intestine, and makes them unable to absorb nutrients from food like fat and protein. As a result, people with celiac disease typically become malnourished.

How common is celiac disease?

It has long been thought that celiac disease was a very rare condition that occurred only in childhood. Researchers now know that the disease is actually more common and affects both children and adults. Three million Americans, or 1 in every 133 people, have celiac disease, but only about 5 percent of them have been diagnosed, according to the National Institutes of Health.

What causes celiac disease?

Physicians are not sure why the disease occurs. But they do know that it is an inherited disorder. The incidence rises to 1 in 22 among people who have an immediate family member with celiac disease. Some researchers say the disease is activated in those who are genetically predisposed by extreme stressors like pregnancy, surgery or a viral infection. Patients with celiac disease also tend to have other autoimmune diseases, which cause the immune system to attack healthy cells and tissue, Like Type 1 diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis and Sjogren’s syndrome.

Does celiac disease always cause digestive problems?

No. Part of the reason why celiac disease is so often overlooked is because it manifests in many different ways. Classic symptoms like bloating, chronic diarrhea, stomach upset and weight loss do not always occur. Patients may instead have symptoms like anemia, bone or joint pain, fatigue, infertility, an itchy rash, osteoporosis or seizures.

Is it common for people with celiac disease to develop a rash?

Dermatitis herpetiformis, an itchy and blistering skin rash, which is commonly found on the elbows, knees or buttocks, occurs in some 15 percent to 25 percent of all patients. People with the rash usually do not have digestive symptoms.

How is celiac disease diagnosed?

Celiac disease is detected by a blood test that looks for elevated levels of autoantibodies proteins that damage the body’s healthy cells and tissues by mistake. It is important that patients continue to eat a regular diet containing gluten before the test; otherwise, the results may come back false positive. If the blood test is positive, most physicians will order an endoscopy, a procedure that lets the doctor look inside the stomach using a thin, flexible tube, to confirm the results. During the endoscopy, the physician will take samples — biopsies — of the intestinal tissue and examine the villi for damage.

Are tests for celiac disease accurate in infants and young children?

The blood test used to diagnose celiac disease is less reliable in children under age 2. If your physician suspects the condition after a negative test result, he or she will follow-up with an endoscopy.

Are there any treatments for celiac disease?

The only way to treat the disease is to follow a gluten-free diet, which eliminates foods and products containing barley, rye and wheat. Most patients’ symptoms will subside, and the damage to their small intestine will heal after just a few months on the diet. Researchers are working on drugs that may be able help people with celiac disease better tolerate gluten.

Which foods have gluten?

Gluten is a protein that is found in barley, rye and wheat. It is found in cereal, grains, pasta and most processed foods. Certain products like lip balms, medications and vitamins may also contain gluten. It is important that people with celiac disease read food and product labels carefully.

Will I ever be able to eat pasta and bread again?

People with celiac disease need to follow a gluten-free diet for the rest of their lives to avoid damaging the small intestine again. Many grocery stores carry special gluten-free bread and pasta products. In 2001, the gluten-free marketplace was a modest $210 million industry. Market researchers project it will reach $1.7 billion by the end of 2010, representing more than a sevenfold increase in just a decade.

What are the long-term complications of celiac disease?

Patients who follow a gluten-free diet rarely have problems. However, failure to adhere to a gluten-free lifestyle can cause serious consequences like anemia, infertility, lymphomas (cancers of the lymph glands) and osteoporosis.

Many people with celiac disease experience bone density loss. Are newly diagnosed patients screened routinely for osteoporosis or osteopenia?

It depends on your doctor. Some physicians will order a DEXA scan, which is a special type of X-ray that measures bone density, in adults and sometimes children, particularly those with a history of fractures. But it is not always standard practice. If you are concerned that you might have bone density loss, discuss taking the test with your physician.

Can supplements help celiac disease?

Sometimes. Patients with celiac disease may benefit from taking a multivitamin and supplements like calcium, iron and vitamin B12. The results of your blood tests and DEXA scan will help your physician determine if supplements are right for you. Supplements should never be used as a replacement for a gluten-free diet.

Should I be screened for celiac disease?

It is a personal decision. Most physicians will recommend that people who have an immediate family member with celiac disease be screened.

5 Things to Know

Hope for Patients With Celiac Disease

By Carolyn Sayre : NY Times Article : December 16, 2009

Dr. Charles Bongiorno is the chief of the division of gastroenterology and hepatology at the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey. “There is hope for patients,” Dr. Bongiorno said of the condition that can be overwhelming for the newly diagnosed. “There is not always going to be bad news.” Here are the five things he thinks everyone should know about the disease:

Celiac disease is underdiagnosed.

Researchers estimate that 1 in every 133 people have the digestive disorder. However, 95 percent of cases have not yet been diagnosed, according to the National Institutes of Health. It is difficult to detect the disease because the symptoms are so variable. Many physicians commonly misdiagnose the disease as other conditions like irritable bowel syndrome.

The classic symptoms are not very common.

It used to be thought that celiac disease always manifested itself in patients as digestive problems like bloating, chronic diarrhea, stomach pain and weight loss. But physicians now know that individuals with the disease have a host of less obvious symptoms including anemia, depression, infertility, osteoporosis and rashes.

Doctors often overlook celiac disease.

The condition is extremely underdiagnosed in patients. Many primary care physicians are unaware that the condition is so common and can manifest itself in unusual ways. If you are concerned that you may celiac disease, it is important that you talk with your physician about being tested. The earlier the disease is diagnosed, the better.

There is a treatment for celiac disease, and it has a very high success rate.

People with the disorder need to maintain a very restrictive gluten-free diet for the rest of their lives. The good news, however, is that the diet typically causes all of the symptoms of the disease to subside. It also repairs the damage that has been done to the intestines and helps avoid major complications that can develop like cancer and osteoporosis.

Those with celiac disease can have a good quality of life.

The diagnosis of celiac disease can be overwhelming for patients, because the diet is so restrictive. Yet a growing number of food manufacturers now make special gluten-free bread and pasta products. Many restaurants are also beginning to offer gluten-free menus. There are also support groups that patients can attend. Contact the National Foundation for Celiac Awareness, which includes advice and support.

Jury Is Still Out on Gluten, the Latest Dietary Villain

By Kate Murphy : NY Times Article : May 8, 2007

Brandi Walzer, a 29-year-old cartographer in Savannah, Ga., loves bread, not to mention pizza and beer. But she tries to avoid them, because they contain gluten — a substance she says upsets her stomach, aggravates her arthritis and touches off depression.

She is among a growing number of Americans who believe that gluten — a protein found in wheat, barley and rye — is responsible for a variety of ills, from skin eruptions to infertility to anxiety to gas. Though diagnostic tests have not indicated she has an allergy or sensitivity to gluten, she nonetheless says she is better off without it.

“I struggle with sticking to a gluten-free diet,” she said, “but when I do, I feel much better.”

There is no question that eating gluten aggravates celiac disease, an autoimmune disorder that damages the small intestine and interferes with absorption of nutrients. But doctors say it is unclear whether gluten can be blamed for other problems.

Nevertheless, it has become a popular dietary villain. Gluten-free foods are popping up on grocery-store shelves and restaurant menus, including those of national chains like P. F. Chang’s and Outback Steakhouse. Warnings of gluten’s evils are common on alternative medicine Web sites and message boards.

“A lot of alternative practitioners like chiropractors have picked up on it and are waving around magic silver balls, crystals and such, telling people they have gluten intolerance,” said Dr. Don W. Powell, a gastroenterologist at the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston.

Sloane Miller, a 35-year-old freelance editor in New York, went on a gluten-free diet six months ago on the advice of her acupuncturist, even though a blood test and a biopsy indicated that she did not have celiacdisease. Long plagued with gastrointestinal distress and believing that she might have an undetectable sensitivity to gluten, Ms. Miller said giving it up was “worth a try.”

Dr. Joseph A. Murray, a gastroenterologist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., who specializes in diagnosing and treating celiac disease, says such advice may be misguided. “There’s this ‘go blame gluten’ thing going on,” he said. “It’s difficult to sort out science from the belief.”

To be sure, whole wheat and other cereal grains that contain gluten can be hard to digest. The bran and germ components tend to pass through the alimentary canal intact, which is why they are often prescribed as a sort of natural broom to relieve constipation — and why they can also cause gas and diarrhea.

Processed and refined wheat products can cause a spike in blood sugar, followed by a drop, that can also make people feel ill. “If you stop eating the beloved Twinkie or fast foods because they contain wheat, then sure you’re going to feel better,” Dr. Murray said. Indeed, many people go on a gluten-free diet not to cure some ill but to lose weight by cutting down on carbohydrates.

Gluten is relatively new to the human diet, as wheat cultivation began only some 10,000 years ago. Now it is ubiquitous, not only in processed foods (including salad dressings, ice cream and peanut butter) but even in the adhesives on envelopes as well as in lipsticks and lotions. “It’s very hard to get away from gluten,” said Dr. Powell of the University of Texas.

Gluten is also making headlines now, because some Chinese suppliers are accused of slipping the industrial chemical melamine into wheat gluten that was added to American pet food, resulting in a product recall. But there is no indication that the contaminated gluten got into the human food supply.

While gluten allergies that provoke an immune response like hives or respiratory problems are rare, celiacdisease is more common than once thought. The prevalence in North America was previously estimated at about 1 in 3,000, but several studies published in the last three years indicate that it is closer to 1 in 100 — and 1 in 22 for those with risk factors like having an immediate relative with celiac disease.

Though no one knows for sure, the revised numbers can probably be attributed to increasing incidence as well as better screening tools. “Chances are now that people actually know someone who has it,” said Dr. Peter H. R. Green, director of the Celiac Disease Center at Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons.

With increased awareness, he said, more people have begun to suspect that they have celiac disease or some milder form of gluten intolerance and decide to eliminate wheat, barley and rye from their diet without proper diagnosis. Ms. Walzer, for example, gave up gluten a year and half ago upon learning she had symptoms similar to those of a co-worker with celiac disease.

Though no test for celiac disease is definitive, the most powerful indicator is a blood test widely used for three years that measures levels of antitissue transglutaminase, or anti-tTG, the antibodies to an enzyme the body secretes when gluten irritates or damages the small intestine.

People with celiac disease have high levels of anti-tTG, suggesting that the body is attacking its own secretions. This autoimmune response leads to destruction of the lining of the small intestine and consequent malabsorption of nutrients. (The test will not be accurate if someone has already stopped eating gluten.) The blood test is usually followed by a duodenal biopsy before a diagnosis of celiac disease is made. The final proof is reversal of symptoms on a gluten-free diet.

Earlier blood tests and a DNA test were far less predictive, and celiac disease has been difficult to identify, especially because its symptoms vary widely. Ann Austin McCormick, a 64-year-old retired elementary school principal in Crosslake, Minn., said she had chronic diarrhea and anemia before she got a diagnosis of celiac disease five years ago. Colin Leslie, a 15-year-old high school student in Rye, N.Y., said he suffered from severe joint pain and headaches before receiving a diagnosis in 2005.

Still others have no symptoms at all — merely a latent form of the disease that may become apparent only after a stressful physiological or psychological event like a serious illness or death of a spouse.

Researchers in the United States, Italy and Great Britain have hypothesized that the incidence of celiacdisease is on the rise worldwide because wheat has become so prevalent in the Western diet that humans are actually overdosing on it. While debatable, this view could also account for cases like those of Ms. Walzer and Ms. Miller, who believe they have subclinical gluten sensitivity.

Currently, the only treatment for celiac disease or a more subjective gluten sensitivity is to avoid eating anything containing gluten. Sensing an opportunity, several companies, including Alba Therapeutics and Alvine Pharmaceuticals Inc., are working to find drugs to inhibit the destructive autoimmune response to gluten that is characteristic of celiac disease.

And dietary supplement makers are in a race to develop enzyme formulations that will help people digest gluten, just as lactase pills and drops were developed in the 1980s to help people digest lactose in dairy products.

But with supermarkets brimming with gluten-free breads, cereals, cakes and cookies and restaurants serving gluten-free pastas, pizzas and beer, it has become far less difficult to stay on a gluten-free diet.

“It’s easy to go gluten-free,” Ms. Miller said. “I don’t miss it at all.”

By Carolyn Sayre : NY Times Article : December 16, 2009

It took three decades to figure out what was making Donna Sawka so sick. Her symptoms — bloating, chronic diarrhea and weight loss — began early in childhood, and they only became worse as she aged.

Nine years ago, after developing severe anemia, a specialist told Ms. Sawka that she had celiac disease. The digestive disorder causes damage to the small intestine when gluten, a protein found in wheat, barley and rye, is ingested. People with the disease need to follow a strict gluten-free diet for the rest of their lives to avoid serious complications like osteoporosis and lymphoma, an immune system cancer.

Ms. Sawka, 48, of Fairless Hills, Pa., said she “was overwhelmed” upon learning she had the disease.

“I kept thinking about everything I wouldn’t be able to eat,” she went on. “I couldn’t even receive communion at church.”

Ms. Sawka’s reaction is a familiar one at the support group she attends. It takes the average patient 10 years to receive a diagnosis. And according to specialists, they are the lucky ones. Studies show that 3 million Americans, or 1 in every 133 people, have celiac disease. But 95 percent of them have yet to learn they have it, according to the National Institutes of Health.

“The entire disease and all of its manifestations are incredibly underdiagnosed,” said Dr. Charles Bongiorno, the chief of the division of gastroenterology and hepatology at the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey. “Patients often have it for a decade or two before they are diagnosed.”

Celiac disease is often difficult to detect because the symptoms vary so widely from person to person. Ten years ago, the medical community thought it was a rare disorder that affected only 1 in every 10,000 people, primarily children who had digestive problems and failure to thrive.

But physicians now know that the disease is much more common. Most patients never experience the so-called classic symptoms: bloating, chronic diarrhea and stomach upset. Instead, the signs are often as nebulous as anemia, infertility and osteoporosis.

“It’s a problem,” said Dr. Ritu Verma, section chief of gastroenterology, hepatology and nutrition and director of the Children’s Celiac Center at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. “The majority of patients do not have the traditional signs and symptoms. If someone’s only presenting symptom is anemia, physicians will think of a hundred other things before they think of celiac disease.”

As a result, the condition is also commonly mistaken for other ailments. Ms. Sawka, for one, was told she had everything from irritable bowel syndrome to lupus to an allergic reaction from a spider bite before celiac disease was confirmed.

Part of the problem is also a lack of education among physicians, particularly internists. According to Dr. Bongiorno, most primary care physicians are simply unaware of new research that shows the disease is common and can manifest itself in unusual ways.

“They think it is an exotic malady,” he explained. “That persistent fallacy causes a less-than-appropriate effort to order the right blood tests and refer to gastroenterologists for care.”

In 2006, the National Institutes of Health started a campaign to raise awareness of the disease among both the general public and physicians. A goal was to increase rates of diagnosis because, unlike many ailments, there is a definitive way to stop celiac disease from progressing once it is recognized.

“The vast majority of cases experience a complete remission from symptoms once they are diagnosed and go on a gluten-free diet,” said Dr. Stefano Guandalini, director of the University of Chicago Celiac Disease Center. “So essentially, you have no disease. That is what makes it all the more important to be diagnosed.”

And there is no better time to be on a gluten-free diet. In 2008, 832 gluten-free products entered the market, nearly 6 times the number that debuted in 2003. Last year, gluten-free even emerged as a fad diet in the general population.

“The quantity and quality of these products is amazing,” said Dr. Alessio Fasano, the medical director of the Center for Celiac Research at the University of Maryland Medical Center.

Dr. Fasano said gluten-free products used to taste like cardboard but had significantly improved in recent years. “The only problem,” he said, “is that they cost five or six times more than their normal counterparts.”

Researchers are also beginning to experiment with drugs that may be able to block the immune response to gluten, much like a lactate pill. If the clinical trials are successful, individuals with celiac disease may be someday able to ingest small amounts of gluten.

Until then, the gluten-free diet is working for patients like Ms. Sawka. “I am perfect now,” she said after 35 years of feeling sick. “Every system in my body was in an uproar, and then everything just quieted down.”

Expert Q & A

Effective Management of Celiac Disease

By Carolyn Sayre : New York Times Article : December 16, 2009

Dr. Ritu Verma is the section chief of gastroenterology, hepatology and nutrition and director of the Children’s Celiac Center at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

Q: You have two children with celiac disease. Did that inspire your work at the center?

A: No. I have been a gastroenterologist for much longer than that. I think it is one of the most fascinating diseases. I used to say to my patients, “If God ever said you have to have a disease, I would say give me celiacs.” There is an end point to it. If you change your diet, your intestines and body are as good as someone who does not have it. There is no other condition in medicine that you can cure — and you can call it a cure — just by changing your diet. There are no needles involved. If you think about it, it is probably the easiest disease to have.

Q: How do patients with celiac disease control their condition through diet?

A: They have to go on a gluten-free diet. That means a diet that does not have any wheat, barley or rye in it. You have to read labels for anything that goes in your mouth every time, because the manufacturer may switch ingredients on you. It is not just food — it is also medicine and cosmetics and, for little children, even Play-Doh and things like that. I had one patient who couldn’t figure out why her blood tests weren’t improving. Finally, she realized her shampoo had gluten in it, and she was ingesting it when she bit her nails.

Q: What can someone with celiac disease eat?

A: There is a lot that they can eat. They can eat any fruits, vegetables or meat; also corn, potatoes, beans, lentils, soymilk and eggs. Most people will eat a lot of Indian and Mediterranean food. Spanish food is also popular, because you can have the corn tortillas. Really, it is just the regular pasta, the bread and the cookies that you can’t have.

Q: Can people with celiac disease eat out at restaurants?

A: Many restaurants now have gluten-free menus. We have done a lot of education with restaurants through the National Foundation for Celiac Awareness and their Appetite for Awareness campaign.

Q: How big of a problem is cross-contamination for people trying to maintain a gluten-free diet?

A: Keeping the diet is easy as far as reading labels, but when you go out to eat you have to talk to the chef and make sure there is no cross-contamination. For example, if you went out to eat for breakfast you would probably think that eggs were safe, but some places use flour to make an omelet. You have to quiz the chef about every ingredient. It is overwhelming, especially when you are just diagnosed.

Q: The number of gluten-free products has increased significantly over the last five years. What has changed?

A: It is an increase in awareness. Five years ago, the National Institutes of Health had this whole session on celiac disease. From there, the North American Society for Pediatric Gastrointerology, Hepatology, and Nutrition started a series of lectures for physicians. Then came the legislation last year that foods would have to be labeled. Awareness has really been building.

Q: Gluten-free and wheat-free labels seem similar, but they mean very different things. Do patients often confuse the two?

A: Yes. That is where the recent labeling became a little dangerous. Foods would say “this does not contain wheat,” but it didn’t say anything about barley and rye. And then there is a whole controversy about oats. So a lot of people would say this is wheat-free, it must be gluten-free. A lot of education is needed about this. Gluten-free is wheat-free, but not the other way around.

Q: Is it important for newly diagnosed patients to work with a dietician?

A: Yes. Patients who are diagnosed and try to figure it out by themselves have a very difficult time and often give up. It is almost impossible to get the proper training yourself. It is also an extremely expensive diet. Going to the store and seeing a loaf of bread costs $8 is enough to make some people say “forget it” or go partially gluten-free, which can make themselves feel better. Dietitians and support groups are really the key to success for people with celiac disease. It is an overwhelming condition.

Q: What happens when patients stop eating gluten?

A: When you have celiac disease, there is damage to the lining of your small intestine. There is something called the villi, these finger-like projections that you look at under the microscope. In people who have celiac disease, the gluten damages the lining of the small intestine and the villi. Once you go on a gluten-free diet, these villi actually start healing and forming back again. If you do another biopsy on someone who has been on a gluten-free diet and is doing well, the small intestine and the villi will be back to normal.

Q: How strictly do patients need to follow the diet if the small intestine and villi will heal after a few months on a gluten-free diet?

A: When you start eating the gluten again, it affects your immune system. So your intestines will heal, but your immune system gets primed. It goes haywire and starts sending out these signals to the rest of your body. Your thyroid and other parts of your body can be affected, and those don’t heal. So it is not just a matter of healing your intestine; it is also a matter of healing your body and protesting this long-term risk of lymphoma that you can develop years down the line. The commitment has to be for life. So you can imagine how tough that is for patients, especially when they start feeling better. How many of us finish a course of antibiotics and when we start feeling better say, “O.K., I am done.”

Q: Physicians used to think celiac disease occurred mostly in childhood. Is any group particularly at risk?

A: A lot of people are diagnosed when they are older now. That is because they are not presenting with the traditional symptoms that young people had. It can really be in any ethnic background. It used to be someone who is Irish or French Canadian, but that is another myth taught in medical schools. It was thought that it was seen in boys more than girls, but that is still up in the air.

Q: Are there any other ways to control celiac disease?

A: Right now, it is only diet. But there are a lot of companies coming up with pills. One of them is actually almost in Phase III trials in adults, and it is thought that it will come out in the next few years. The idea is that people who take this pill would be covered if they went out and had cross contamination. The danger to this pill, of course, is people who would go out and eat regular pizza. We have to wait and see if it is safe enough for that. Right now it is only being tested to protect against the small amount of gluten that may be in someone’s diet.

Q: Are there any efforts to make a celiac vaccine?

A: There are some people who are working on a vaccine. The problem with a vaccine is that there are many different H.L.A. (human leukocyte antigens) types associated with celiac disease, so a vaccine will not be very easy. But I know the person who is looking at the vaccine is trying to develop one for the HLA-DQ2 type, because that is the more lethal one in terms of the long-term risks of cancer.

Questions for Your Doctor

What to Ask About Celiac Disease

By Carolyn Sayre : NY Times Article : December 16, 2009

Confronting a new diagnosis can be frightening — and because research changes so often, confusing. Here are some questions you may not think to ask your doctor, along with notes on why they’re important.

What is celiac disease?

Celiac disease is a digestive condition that causes an immune reaction in the small intestine when gluten, a protein found in wheat, barley and rye, is ingested. Gluten damages the tiny hairlike protrusions known as villi, which line the small intestine, and makes them unable to absorb nutrients from food like fat and protein. As a result, people with celiac disease typically become malnourished.

How common is celiac disease?

It has long been thought that celiac disease was a very rare condition that occurred only in childhood. Researchers now know that the disease is actually more common and affects both children and adults. Three million Americans, or 1 in every 133 people, have celiac disease, but only about 5 percent of them have been diagnosed, according to the National Institutes of Health.

What causes celiac disease?

Physicians are not sure why the disease occurs. But they do know that it is an inherited disorder. The incidence rises to 1 in 22 among people who have an immediate family member with celiac disease. Some researchers say the disease is activated in those who are genetically predisposed by extreme stressors like pregnancy, surgery or a viral infection. Patients with celiac disease also tend to have other autoimmune diseases, which cause the immune system to attack healthy cells and tissue, Like Type 1 diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis and Sjogren’s syndrome.

Does celiac disease always cause digestive problems?

No. Part of the reason why celiac disease is so often overlooked is because it manifests in many different ways. Classic symptoms like bloating, chronic diarrhea, stomach upset and weight loss do not always occur. Patients may instead have symptoms like anemia, bone or joint pain, fatigue, infertility, an itchy rash, osteoporosis or seizures.

Is it common for people with celiac disease to develop a rash?

Dermatitis herpetiformis, an itchy and blistering skin rash, which is commonly found on the elbows, knees or buttocks, occurs in some 15 percent to 25 percent of all patients. People with the rash usually do not have digestive symptoms.

How is celiac disease diagnosed?

Celiac disease is detected by a blood test that looks for elevated levels of autoantibodies proteins that damage the body’s healthy cells and tissues by mistake. It is important that patients continue to eat a regular diet containing gluten before the test; otherwise, the results may come back false positive. If the blood test is positive, most physicians will order an endoscopy, a procedure that lets the doctor look inside the stomach using a thin, flexible tube, to confirm the results. During the endoscopy, the physician will take samples — biopsies — of the intestinal tissue and examine the villi for damage.

Are tests for celiac disease accurate in infants and young children?

The blood test used to diagnose celiac disease is less reliable in children under age 2. If your physician suspects the condition after a negative test result, he or she will follow-up with an endoscopy.

Are there any treatments for celiac disease?

The only way to treat the disease is to follow a gluten-free diet, which eliminates foods and products containing barley, rye and wheat. Most patients’ symptoms will subside, and the damage to their small intestine will heal after just a few months on the diet. Researchers are working on drugs that may be able help people with celiac disease better tolerate gluten.

Which foods have gluten?

Gluten is a protein that is found in barley, rye and wheat. It is found in cereal, grains, pasta and most processed foods. Certain products like lip balms, medications and vitamins may also contain gluten. It is important that people with celiac disease read food and product labels carefully.

Will I ever be able to eat pasta and bread again?

People with celiac disease need to follow a gluten-free diet for the rest of their lives to avoid damaging the small intestine again. Many grocery stores carry special gluten-free bread and pasta products. In 2001, the gluten-free marketplace was a modest $210 million industry. Market researchers project it will reach $1.7 billion by the end of 2010, representing more than a sevenfold increase in just a decade.

What are the long-term complications of celiac disease?

Patients who follow a gluten-free diet rarely have problems. However, failure to adhere to a gluten-free lifestyle can cause serious consequences like anemia, infertility, lymphomas (cancers of the lymph glands) and osteoporosis.

Many people with celiac disease experience bone density loss. Are newly diagnosed patients screened routinely for osteoporosis or osteopenia?

It depends on your doctor. Some physicians will order a DEXA scan, which is a special type of X-ray that measures bone density, in adults and sometimes children, particularly those with a history of fractures. But it is not always standard practice. If you are concerned that you might have bone density loss, discuss taking the test with your physician.

Can supplements help celiac disease?

Sometimes. Patients with celiac disease may benefit from taking a multivitamin and supplements like calcium, iron and vitamin B12. The results of your blood tests and DEXA scan will help your physician determine if supplements are right for you. Supplements should never be used as a replacement for a gluten-free diet.

Should I be screened for celiac disease?

It is a personal decision. Most physicians will recommend that people who have an immediate family member with celiac disease be screened.

5 Things to Know

Hope for Patients With Celiac Disease

By Carolyn Sayre : NY Times Article : December 16, 2009

Dr. Charles Bongiorno is the chief of the division of gastroenterology and hepatology at the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey. “There is hope for patients,” Dr. Bongiorno said of the condition that can be overwhelming for the newly diagnosed. “There is not always going to be bad news.” Here are the five things he thinks everyone should know about the disease:

Celiac disease is underdiagnosed.

Researchers estimate that 1 in every 133 people have the digestive disorder. However, 95 percent of cases have not yet been diagnosed, according to the National Institutes of Health. It is difficult to detect the disease because the symptoms are so variable. Many physicians commonly misdiagnose the disease as other conditions like irritable bowel syndrome.

The classic symptoms are not very common.

It used to be thought that celiac disease always manifested itself in patients as digestive problems like bloating, chronic diarrhea, stomach pain and weight loss. But physicians now know that individuals with the disease have a host of less obvious symptoms including anemia, depression, infertility, osteoporosis and rashes.

Doctors often overlook celiac disease.

The condition is extremely underdiagnosed in patients. Many primary care physicians are unaware that the condition is so common and can manifest itself in unusual ways. If you are concerned that you may celiac disease, it is important that you talk with your physician about being tested. The earlier the disease is diagnosed, the better.

There is a treatment for celiac disease, and it has a very high success rate.

People with the disorder need to maintain a very restrictive gluten-free diet for the rest of their lives. The good news, however, is that the diet typically causes all of the symptoms of the disease to subside. It also repairs the damage that has been done to the intestines and helps avoid major complications that can develop like cancer and osteoporosis.

Those with celiac disease can have a good quality of life.

The diagnosis of celiac disease can be overwhelming for patients, because the diet is so restrictive. Yet a growing number of food manufacturers now make special gluten-free bread and pasta products. Many restaurants are also beginning to offer gluten-free menus. There are also support groups that patients can attend. Contact the National Foundation for Celiac Awareness, which includes advice and support.

Jury Is Still Out on Gluten, the Latest Dietary Villain

By Kate Murphy : NY Times Article : May 8, 2007

Brandi Walzer, a 29-year-old cartographer in Savannah, Ga., loves bread, not to mention pizza and beer. But she tries to avoid them, because they contain gluten — a substance she says upsets her stomach, aggravates her arthritis and touches off depression.

She is among a growing number of Americans who believe that gluten — a protein found in wheat, barley and rye — is responsible for a variety of ills, from skin eruptions to infertility to anxiety to gas. Though diagnostic tests have not indicated she has an allergy or sensitivity to gluten, she nonetheless says she is better off without it.

“I struggle with sticking to a gluten-free diet,” she said, “but when I do, I feel much better.”

There is no question that eating gluten aggravates celiac disease, an autoimmune disorder that damages the small intestine and interferes with absorption of nutrients. But doctors say it is unclear whether gluten can be blamed for other problems.

Nevertheless, it has become a popular dietary villain. Gluten-free foods are popping up on grocery-store shelves and restaurant menus, including those of national chains like P. F. Chang’s and Outback Steakhouse. Warnings of gluten’s evils are common on alternative medicine Web sites and message boards.

“A lot of alternative practitioners like chiropractors have picked up on it and are waving around magic silver balls, crystals and such, telling people they have gluten intolerance,” said Dr. Don W. Powell, a gastroenterologist at the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston.

Sloane Miller, a 35-year-old freelance editor in New York, went on a gluten-free diet six months ago on the advice of her acupuncturist, even though a blood test and a biopsy indicated that she did not have celiacdisease. Long plagued with gastrointestinal distress and believing that she might have an undetectable sensitivity to gluten, Ms. Miller said giving it up was “worth a try.”

Dr. Joseph A. Murray, a gastroenterologist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., who specializes in diagnosing and treating celiac disease, says such advice may be misguided. “There’s this ‘go blame gluten’ thing going on,” he said. “It’s difficult to sort out science from the belief.”

To be sure, whole wheat and other cereal grains that contain gluten can be hard to digest. The bran and germ components tend to pass through the alimentary canal intact, which is why they are often prescribed as a sort of natural broom to relieve constipation — and why they can also cause gas and diarrhea.

Processed and refined wheat products can cause a spike in blood sugar, followed by a drop, that can also make people feel ill. “If you stop eating the beloved Twinkie or fast foods because they contain wheat, then sure you’re going to feel better,” Dr. Murray said. Indeed, many people go on a gluten-free diet not to cure some ill but to lose weight by cutting down on carbohydrates.

Gluten is relatively new to the human diet, as wheat cultivation began only some 10,000 years ago. Now it is ubiquitous, not only in processed foods (including salad dressings, ice cream and peanut butter) but even in the adhesives on envelopes as well as in lipsticks and lotions. “It’s very hard to get away from gluten,” said Dr. Powell of the University of Texas.

Gluten is also making headlines now, because some Chinese suppliers are accused of slipping the industrial chemical melamine into wheat gluten that was added to American pet food, resulting in a product recall. But there is no indication that the contaminated gluten got into the human food supply.

While gluten allergies that provoke an immune response like hives or respiratory problems are rare, celiacdisease is more common than once thought. The prevalence in North America was previously estimated at about 1 in 3,000, but several studies published in the last three years indicate that it is closer to 1 in 100 — and 1 in 22 for those with risk factors like having an immediate relative with celiac disease.

Though no one knows for sure, the revised numbers can probably be attributed to increasing incidence as well as better screening tools. “Chances are now that people actually know someone who has it,” said Dr. Peter H. R. Green, director of the Celiac Disease Center at Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons.

With increased awareness, he said, more people have begun to suspect that they have celiac disease or some milder form of gluten intolerance and decide to eliminate wheat, barley and rye from their diet without proper diagnosis. Ms. Walzer, for example, gave up gluten a year and half ago upon learning she had symptoms similar to those of a co-worker with celiac disease.

Though no test for celiac disease is definitive, the most powerful indicator is a blood test widely used for three years that measures levels of antitissue transglutaminase, or anti-tTG, the antibodies to an enzyme the body secretes when gluten irritates or damages the small intestine.

People with celiac disease have high levels of anti-tTG, suggesting that the body is attacking its own secretions. This autoimmune response leads to destruction of the lining of the small intestine and consequent malabsorption of nutrients. (The test will not be accurate if someone has already stopped eating gluten.) The blood test is usually followed by a duodenal biopsy before a diagnosis of celiac disease is made. The final proof is reversal of symptoms on a gluten-free diet.

Earlier blood tests and a DNA test were far less predictive, and celiac disease has been difficult to identify, especially because its symptoms vary widely. Ann Austin McCormick, a 64-year-old retired elementary school principal in Crosslake, Minn., said she had chronic diarrhea and anemia before she got a diagnosis of celiac disease five years ago. Colin Leslie, a 15-year-old high school student in Rye, N.Y., said he suffered from severe joint pain and headaches before receiving a diagnosis in 2005.

Still others have no symptoms at all — merely a latent form of the disease that may become apparent only after a stressful physiological or psychological event like a serious illness or death of a spouse.

Researchers in the United States, Italy and Great Britain have hypothesized that the incidence of celiacdisease is on the rise worldwide because wheat has become so prevalent in the Western diet that humans are actually overdosing on it. While debatable, this view could also account for cases like those of Ms. Walzer and Ms. Miller, who believe they have subclinical gluten sensitivity.

Currently, the only treatment for celiac disease or a more subjective gluten sensitivity is to avoid eating anything containing gluten. Sensing an opportunity, several companies, including Alba Therapeutics and Alvine Pharmaceuticals Inc., are working to find drugs to inhibit the destructive autoimmune response to gluten that is characteristic of celiac disease.

And dietary supplement makers are in a race to develop enzyme formulations that will help people digest gluten, just as lactase pills and drops were developed in the 1980s to help people digest lactose in dairy products.

But with supermarkets brimming with gluten-free breads, cereals, cakes and cookies and restaurants serving gluten-free pastas, pizzas and beer, it has become far less difficult to stay on a gluten-free diet.

“It’s easy to go gluten-free,” Ms. Miller said. “I don’t miss it at all.”

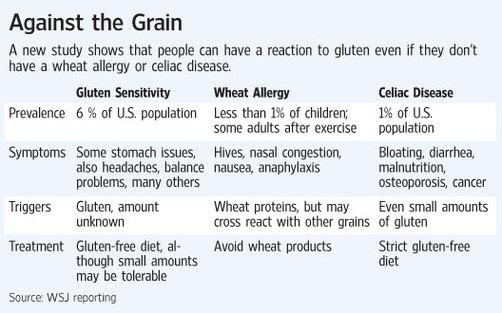

Clues to Gluten Sensitivity

By Melinda Beck : WSJ : March 14, 2011

Lisa Rayburn felt dizzy, bloated and exhausted. Wynn Avocette suffered migraines and body aches. Stephanie Meade's 4-year-old daughter had constipation and threw temper tantrums.

Some people claim that eating gluten products can cause health problems like body aches and chronic fatigue -- and even some behavioral problems in children. WSJ's Melinda Beck talks with Kelsey Hubbard about a new study that sheds light on what may be going on.

All three tested negative for celiac disease, a severe intolerance to gluten, a protein found in wheat and other grains. But after their doctors ruled out other causes, all three adults did their own research and cut gluten—and saw the symptoms subside.

A new study in the journal BMC Medicine may shed some light on why. It shows gluten can set off a distinct reaction in the intestines and the immune system, even in people who don't have celiac disease.

"For the first time, we have scientific evidence that indeed, gluten sensitivity not only exists, but is very different from celiac disease," says lead author Alessio Fasano, medical director of the University of Maryland's Center for Celiac Research.

The news will be welcome to people who have suspected a broad range of ailments may be linked to their gluten intake, but have failed to find doctors who agree.

"Patients have been told if it wasn't celiac disease, it wasn't anything. It was all in their heads," says Cynthia Kupper, executive director of the nonprofit Gluten Intolerance Group of North America.

The growing market for gluten-free foods, with sales estimated at $2.6 billion last year, has made it even harder to distinguish a medical insight from a fad.

Although much remains unknown, it is clear that gluten—a staple of human diets for 10,000 years—triggers an immune response like an enemy invader in some modern humans.

The most basic negative response is an allergic reaction to wheat that quickly brings on hives, congestion, nausea or potentially fatal anaphylaxis. Less than 1% of children have the allergy and most outgrow it by age five. A small number of adults have similar symptoms if they exercise shortly after eating wheat.

At the other extreme is celiac disease, which causes the immune system to mistakenly attack the body's own tissue. Antibodies triggered by gluten flatten the villi, the tiny fingers in the intestines needed to soak up nutrients from food. The initial symptoms are cramping, bloating and diarrhea, similar to irritable bowel syndrome, or IBS, but celiac disease can lead to malnutrition, osteoporosis and other more serious health problems that can result in early death. It can be diagnosed with a blood test, but an intestinal biopsy is needed to be sure.

The incidence of celiac disease is rising sharply—and not just due to greater awareness. Tests comparing old blood samples to recent ones show the rate has increased four-fold in the last 50 years, to at least 1 in 133 Americans. It's also being diagnosed in people as old as 70 who have eaten gluten safely all their lives.

"People aren't born with this. Something triggers it and with this dramatic rise in all ages, it must be something pervasive in the environment," says Joseph A. Murray, a gastroenterologist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. One possible culprit: agricultural changes to wheat that have boosted its protein content.

Gluten sensitivity, also known as gluten intolerance, is much more vague.

Some experts think as many as 1 in 20 Americans may have some form of it, but there is no test or defined set of symptoms. The most common are IBS-like stomach problems, headaches, fatigue, numbness and depression, but more than 100 symptoms have been loosely linked to gluten intake, which is why it has been so difficult to study. Peter Green, director of the Celiac Disease Center says that research into gluten sensitivity today is roughly where celiac disease was 30 years ago.

In the new study, researchers compared blood samples and intestinal biopsies from 42 subjects with confirmed celiac disease, 26 with suspected gluten sensitivity and 39 healthy controls. Those with gluten sensitivity didn't have the flattened villi, or the "leaky" intestinal walls seen in the subjects with celiac disease.

Their immune reactions were different, too. In the gluten-sensitive group, the response came from innate immunity, a primitive system with which the body sets up barriers to repel invaders. The subjects with celiac disease rallied adaptive immunity, a more sophisticated system that develops specific cells to fight foreign bodies.

The findings still need to be replicated. How a reaction to gluten could cause such a wide range of symptoms also remains unproven. Dr. Fasano and other experts speculate that once immune cells are mistakenly primed to attack gluten, they can migrate and spread inflammation, even to the brain.

Indeed, Marios Hadjivassiliou, a neurologist in Sheffield, England, says he found deposits of antibodies to gluten in autopsies and brain scans of some patients with ataxia, a condition of impaired balance.

Could such findings help explain why some parents of autistic children say their symptoms have improved—sometimes dramatically—when gluten was eliminated from their diets? To date, no scientific studies have emerged to back up such reports.

Dr. Fasano hopes to eventually discover a biomarker specifically for gluten sensitivity. In the meantime, he and other experts recommend that anyone who thinks they have it be tested for celiac disease first.

For now, a gluten-free diet is the only treatment recommended for gluten sensitivity, though some may be able to tolerate small amounts, says Ms. Kupper.

"There's a lot more that needs to be done for people with gluten sensitivity," she says. "But at least we now recognize that it's real and that these people aren't crazy."

By Melinda Beck : WSJ : March 14, 2011

Lisa Rayburn felt dizzy, bloated and exhausted. Wynn Avocette suffered migraines and body aches. Stephanie Meade's 4-year-old daughter had constipation and threw temper tantrums.

Some people claim that eating gluten products can cause health problems like body aches and chronic fatigue -- and even some behavioral problems in children. WSJ's Melinda Beck talks with Kelsey Hubbard about a new study that sheds light on what may be going on.

All three tested negative for celiac disease, a severe intolerance to gluten, a protein found in wheat and other grains. But after their doctors ruled out other causes, all three adults did their own research and cut gluten—and saw the symptoms subside.

A new study in the journal BMC Medicine may shed some light on why. It shows gluten can set off a distinct reaction in the intestines and the immune system, even in people who don't have celiac disease.

"For the first time, we have scientific evidence that indeed, gluten sensitivity not only exists, but is very different from celiac disease," says lead author Alessio Fasano, medical director of the University of Maryland's Center for Celiac Research.

The news will be welcome to people who have suspected a broad range of ailments may be linked to their gluten intake, but have failed to find doctors who agree.

"Patients have been told if it wasn't celiac disease, it wasn't anything. It was all in their heads," says Cynthia Kupper, executive director of the nonprofit Gluten Intolerance Group of North America.

The growing market for gluten-free foods, with sales estimated at $2.6 billion last year, has made it even harder to distinguish a medical insight from a fad.

Although much remains unknown, it is clear that gluten—a staple of human diets for 10,000 years—triggers an immune response like an enemy invader in some modern humans.

The most basic negative response is an allergic reaction to wheat that quickly brings on hives, congestion, nausea or potentially fatal anaphylaxis. Less than 1% of children have the allergy and most outgrow it by age five. A small number of adults have similar symptoms if they exercise shortly after eating wheat.

At the other extreme is celiac disease, which causes the immune system to mistakenly attack the body's own tissue. Antibodies triggered by gluten flatten the villi, the tiny fingers in the intestines needed to soak up nutrients from food. The initial symptoms are cramping, bloating and diarrhea, similar to irritable bowel syndrome, or IBS, but celiac disease can lead to malnutrition, osteoporosis and other more serious health problems that can result in early death. It can be diagnosed with a blood test, but an intestinal biopsy is needed to be sure.

The incidence of celiac disease is rising sharply—and not just due to greater awareness. Tests comparing old blood samples to recent ones show the rate has increased four-fold in the last 50 years, to at least 1 in 133 Americans. It's also being diagnosed in people as old as 70 who have eaten gluten safely all their lives.

"People aren't born with this. Something triggers it and with this dramatic rise in all ages, it must be something pervasive in the environment," says Joseph A. Murray, a gastroenterologist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. One possible culprit: agricultural changes to wheat that have boosted its protein content.

Gluten sensitivity, also known as gluten intolerance, is much more vague.

Some experts think as many as 1 in 20 Americans may have some form of it, but there is no test or defined set of symptoms. The most common are IBS-like stomach problems, headaches, fatigue, numbness and depression, but more than 100 symptoms have been loosely linked to gluten intake, which is why it has been so difficult to study. Peter Green, director of the Celiac Disease Center says that research into gluten sensitivity today is roughly where celiac disease was 30 years ago.

In the new study, researchers compared blood samples and intestinal biopsies from 42 subjects with confirmed celiac disease, 26 with suspected gluten sensitivity and 39 healthy controls. Those with gluten sensitivity didn't have the flattened villi, or the "leaky" intestinal walls seen in the subjects with celiac disease.

Their immune reactions were different, too. In the gluten-sensitive group, the response came from innate immunity, a primitive system with which the body sets up barriers to repel invaders. The subjects with celiac disease rallied adaptive immunity, a more sophisticated system that develops specific cells to fight foreign bodies.

The findings still need to be replicated. How a reaction to gluten could cause such a wide range of symptoms also remains unproven. Dr. Fasano and other experts speculate that once immune cells are mistakenly primed to attack gluten, they can migrate and spread inflammation, even to the brain.