- RETIREMENT ANNOUNCEMENT

- HOME PAGE

- "MYCHART" the new patient portal

- BELMONT MEDICAL ASSOCIATES

- MOUNT AUBURN HOSPITAL

- EMERGENCIES

- PRACTICE PHILOSOPHY

- MY RESUME

- TELEMEDICINE CONSULTATION

- CONTACT ME

- LAB RESULTS

- ePRESCRIPTIONS

- eREFERRALS

- RECORD RELEASE

- MEDICAL SCRIBE

- PHYSICIAN ASSISTANT (PA)

- Medicare Annual Wellness Visit

- Case management/Social work

- Quality Care Measures

- Emergency closing notice

- FEEDBACK

- Talking to your doctor

- Choosing..... and losing a doctor

- INDEX A - Z

- ALLERGIC REACTIONS

- Alternative Medicine

- Alzheimer's Disease

- Bladder Problems

- Blood disorders

- Cancer Concerns

- GENETIC TESTING FOR HEREDITARY CANCER

- Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

- Controversial Concerns

- CPR : Learn and save a life

- CRP : Inflammatory marker

- Diabetes Management

- Dizziness, Vertigo,Tinnitus and Hearing Loss

- EXERCISE

- FEMALE HEALTH

-

GASTROINTESTINAL topics

- Appendicitis

- BRAT diet

- Celiac Disease or Sprue

- Crohn's Disease

- Gastroenterologists for Colon Cancer Screening

- Colonoscopy PREP

- Constipation

- Gluten sensitivity, but not celiac disease

- Heartburn and GERD

- Hemorrhoids and Anal fissure

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- NASH : Non Alcoholic Steato Hepatitis

- FEET PROBLEMS

- HEART RELATED topics

-

INFECTIOUS DISEASES

- Antibiotic Resistance

- Cat bites >

- Clostridia difficile infection - the "antibiotic associated germ"

- CORONA VIRUS

- Dengue Fever and Chikungunya Fever

- Food borne illnesses

- Shingles Vaccine

- Hepatitis B

- Hepatitis C

- Herpes

- Influenza

- Helicobacter pylori - the "ulcer germ"

- HIV Screening

- Lyme and other tick borne diseases

- Measles

- Meningitis

- MRSA (Staph infection)

- Norovirus

- Sexually Transmitted Diseases

- Shingles (Herpes Zoster)

- Sinusitis

- West Nile Virus

- Whooping Cough (Pertussis)

- Zika virus and pregnancy

- INSURANCE related topics

- KIDNEY STONES

- LEG CRAMPS

- LIBRARY for patients

- LIFE DECISIONS

- MALE HEALTH

- Medication/Drug side effects

- MEDICAL MARIJUANA

- MENTAL HEALTH

- Miscellaneous Articles

-

NUTRITION - EXERCISE - WEIGHT

- Cholesterol : New guidelines for treatment

- Advice to lower your cholesterol

- Cholesterol : Control

- Cholesterol : Raising your HDL Level

- Exercise

- Food : Making Smart Choices

- Food : Making Poor Choices

- Food : Grape Fruit and Drug Interaction

- Food : Vitamins, Minerals and Supplements

- Omega 3 fatty acids

- Vitamin B12 deficiency

- Vitamin D

- Weight Loss

- ORTHOPEDICS

- PAIN

- PATIENTS' RIGHTS

- SKIN

- SLEEP

- SMOKING

- STROKE

- THYROID

- SUBSTANCE ABUSE

- Travel and Vaccination

- TREMOR

- Warfarin Anticoagulation

- OTHER STUFF FOLLOWS

- Fact or Opinion?

- Hippocratic Oath

- FREE ADVICE.......for what its worth!

- LAUGHTER.....is the best medicine

- Physicians Pet Peeves

- PHOTO ALBUM - its not all work!

- Cape Town, South Africa

- Tribute page

- The 100 Club

- Free Wi-Fi

Ovarian Cancer

What every woman should know...

Ovarian cancer is a serious and under-recognized threat to womens health.

Ovarian cancer is very treatable when caught early; the vast majority of cases are not diagnosed until too late.

Ovarian cancer is difficult to diagnose

Raise Your Awareness

Early recognition of symptoms is the best way to save women's lives. Early symptoms include:

If ovarian cancer is suspected, ask to see a gynecological oncologist.

What You Should Ask Your Doctor:

While everyone has these symptoms from time to time, it is important to know your own body and know when something is not right.

If you have these symptoms and they are not normal for you neither you nor your doctor knows why you are having them,

Then ask to have these important tests to help you rule out ovarian cancer.

Who Has the Greatest Risk?

Symptoms Found for Early Check on Ovary Cancer

By Denise Grady : NY Times Article : June 13, 2007

Cancer experts have identified a set of health problems that may be symptoms of ovarian cancer, and they are urging women who have the symptoms for more than a few weeks to see their doctors.

The new advice is the first official recognition that ovarian cancer, long believed to give no warning until it was far advanced, does cause symptoms at earlier stages in many women.

The symptoms to watch out for are bloating, pelvic or abdominal pain, difficulty eating or feeling full quickly and feeling a frequent or urgent need to urinate. A woman who has any of those problems nearly every day for more than two or three weeks is advised to see a gynecologist, especially if the symptoms are new and quite different from her usual state of health.

Doctors say they hope that the recommendations will make patients and doctors aware of early symptoms, lead to earlier diagnosis and, perhaps, save lives, or at least prolong survival.

But it is too soon to tell whether the new measures will work or whether they will lead to a flood of diagnostic tests or even unnecessary operations.

Cancer experts say it is worth trying a more aggressive approach to finding ovarian cancer early. The disease is among the deadlier types of cancer, because most cases are diagnosed late, after the cancer has begun to spread.

This year, 22,430 new cases and 15,280 deaths are expected in the United States.

If the cancer is found and surgically removed early, before it spreads outside the ovary, 93 percent of patients are still alive five years later. Only 19 percent of cases are found that early, and 45 percent of all women with the disease survive at least five years after the diagnosis.

By contrast, among women with breast cancer, 89 percent survive five years or more.

The new recommendations, expected to be formally announced on June 25, are being made by the Gynecologic Cancer Foundation, the Society of Gynecologic Oncologists and the American Cancer Society.

More than 12 other groups have endorsed them, including CancerCare; Gilda’s Club, a support network for anyone touched by cancer; and several medical societies.

“The majority of the time this won’t be ovarian cancer, but it’s just something that should be considered,” said Dr. Barbara Goff, the director of gynecologic oncology at the University of Washington in Seattle and an author of several studies that helped identify the relevant symptoms.

In a number of studies by Dr. Goff and other researchers, these symptoms stood out in women with ovarian cancer as compared with other women.

“We don’t want to scare people, but we also want to arm people with the appropriate information,” said Dr. Goff, who is also a spokeswoman for the Gynecologic Cancer Foundation.

She emphasized that relatively new and persistent problems were the most important ones. So, the transient bloating that often accompanies menstrual periods would not qualify, nor would a lifelong history of indigestion.

Dr. Goff also acknowledged that the urinary problems on the list were classic symptoms of bladder infections, which is common in women. But it still makes sense to consult a doctor, she said, because bladder infections should be treated. Urinary trouble that persists despite treatment is a particular cause for concern, she said.

With ovarian cancer, even a few months’ delay in making the diagnosis may make a difference in survival, because the tumors can grow and spread quickly through the abdomen to the intestines, liver, diaphragm and other organs, Dr. Goff said.

“If you let it go for three months, you can wind up with disease everywhere,” she said

Dr. Thomas J. Herzog, director of gynecologic oncology at the Columbia University Medical Center, said the recommendations were important because the medical profession had until now told women that there were no specific early symptoms.

“If women were more pro-active at recognizing these symptoms, we’d be better at making the diagnosis at an earlier stage,” Dr. Herzog said.

“These are nonspecific symptoms that many people have,” he added. “But when the symptoms persist or worsen, you need to see a specialist. By no means do we want this to result in unnecessary surgery. But I would not expect that to occur in the vast majority of cases.”

Although the American Cancer Society agreed to the recommendations, it did so with some reservations, said Debbie Saslow, director of breast and gynecologic cancer at the society.

“We don’t have any consensus about what doctors should do once the women come to them,” Dr. Saslow said. “There was a lot of hope that we’d be able to say, ‘Go to your doctor, and they will give you this standardized work-up.’ But we can’t do that.”

At the same time, Dr. Saslow said, the cancer society recognized that in some cases doctors had disregarded symptoms in women who were later found to have ovarian cancer, telling the women instead that they were just growing old or going through menopause.

“There are so many horror stories of doctors who have told women to ignore these symptoms or have even belittled them on top of that,” Dr. Saslow said.

In a survey of 1,700 women with ovarian cancer, Dr. Goff and other researchers found that 36 percent had initially been given a wrong diagnosis, with conditions like depression or irritable bowel syndrome.

“Twelve percent were told there was nothing wrong with them, and it was all in their heads,” Dr. Goff said.

Dr. Goff and other specialists said women with the listed symptoms should see a gynecologist for a pelvic and rectal examination. (The best way for a doctor to feel the ovaries is through the rectum.) If there is a question of cancer, the next step is probably a test called a transvaginal ultrasound to check the ovaries for abnormal growths, enlargement or telltale pockets of fluid that can signal cancer. The ultrasound costs $150 to $300 and can be performed in a doctor’s office or a radiology center. A $100 blood test should also be conducted for CA125, a substance called a tumor marker that is often elevated in women with ovarian cancer.

Cancer specialists say any woman with suspicious findings on the tests should be referred to a gynecologic oncologist, a surgeon who specializes in cancers of the female reproductive system.

An unresolved question is what exactly should be done if the test results are normal and yet the woman continues to have symptoms, Dr. Saslow said.

“Do you do exploratory surgery, which has side effects, which are sometimes even fatal?” she asked. “What do you do? We don’t have the answer to that.”

Depending on the test results, the woman may just be monitored for a while or advised to undergo a CT scan or an MRI. But if cancer is strongly suspected, she will probably be urged to go straight to surgery. A needle biopsy, commonly used for breast lumps, cannot be safely performed to check for ovarian cancer because it runs a risk of rupturing the tumor and spreading malignant cells in the abdomen. Instead, the surgeon must carefully remove the entire ovary or the abnormal growth on it and examine the rest of the abdomen for cancer.

While the patient is still on the operating table, biopsies are performed on the tissue that was removed, so that if cancer is found, the surgeon can operate more extensively. Experts say such an operation should be carried out just by gynecologic oncologists, who have special training in meticulously removing as much of the cancerous tissue as possible. This procedure, called debulking, lets chemotherapy work better and greatly improves survival.

Dr. Carol L. Brown, a gynecologic oncologist at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in Manhattan, said, “Ideally, we need to develop a screening tool or a test to find ovarian cancer before it has symptoms.”

No such screening test exists, Dr. Brown said, and until one is developed, the list of symptoms may be the best solution.

“This is something that women themselves can do,” she added, “and we can familiarize clinicians with, to help make the diagnosis earlier.”

Cancer Test for Women Raises Hope, and Concern

By Andrew Pollack : NY Times Article : August 26, 2008

A new blood test aimed at detecting ovarian cancer at an early, still treatable stage is stirring hopes among women and their physicians. But the Food and Drug Administration and some experts say the test has not been proved to work. [They have as a result not approved its usage, but the article is interesting]

The test, called OvaSure, was developed at Yale and has been offered since late June by LabCorp, one of the nation's largest clinical laboratory companies.

The need for such a test is immense. When ovarian cancer is detected at its earliest stage, when it is still confined to the ovaries, more than 90 percent of women will live at least five years, according to the American Cancer Society. But only about 20 percent of cases are detected that early. If the cancer is detected in its latest stages, after it has spread, only about 30 percent of women survive five years.

But far from greeting the new test with elation, many experts are saying it might do more harm than good, leading women to unnecessary surgeries. The Society of Gynecologic Oncologists almost immediately issued a statement saying it did not believe the test had been validated enough for routine use.

"You've got industry trying to capitalize on fear," said Dr. Andrew Berchuck, director of gynecologic oncology at Duke University and the immediate past president of the society. "We'd all love to see a screening test for ovarian cancer," he added, "but OvaSure is very premature."

OvaSure's debut also raises questions about whether greater regulation is needed to assure the validity of a trove of sophisticated new diagnostic tests that are entering the market and are being used as the basis for important treatment decisions. OvaSure did not go through review by the Food and Drug Administration because the agency generally has not regulated tests developed and performed by a single laboratory, as opposed to test kits that are sold to laboratories, hospitals and doctors. (All OvaSure blood samples are sent to LabCorp for analysis.)

But the F.D.A. has now summoned LabCorp to discuss OvaSure, saying the data appear insufficient to back the company's claims about the test. "We believe you are offering a high-risk test that has not received adequate clinical validation and may harm the public health," the agency said in an Aug. 7 letter sent to LabCorp that was posted on the F.D.A. Web site. A spokesman for LabCorp, which is short for Laboratory Corporation of America Holdings, said the company looked forward to reviewing the data with the agency but would continue offering the test in the meantime.

Dr. Myla Lai-Goldman, chief medical officer of LabCorp, said that OvaSure had been validated in several studies and that additional data were expected by the end of this year. Diagnostic tests typically are studied further after they have reached the market, she said. Dr. Goldman said there was "tremendous interest" from physicians in learning more about OvaSure.

Patients and advocacy groups seem divided on OvaSure, which costs about $220 to $240.

"We are hearing from people that they are very excited about it," said Cara Tenenbaum, policy director for the Ovarian Cancer National Alliance. But the alliance urges women to wait for more data before relying on the test.

More than 21,000 new cases of ovarian cancer will be diagnosed in the United States this year and more than 15,000 people are expected to die from the disease, according to the American Cancer Society.

OvaSure measures the level of six proteins in a sample of blood, some produced by a tumor and some produced by the body in reaction to a tumor. It then calculates a probability that the woman has ovarian cancer. One of the six proteins is CA-125, which is used by itself as a test to monitor disease progression in women who already have ovarian cancer but is not good at picking up early disease.

In a study published in the journal Clinical Cancer Research in February, the test correctly classified 221 of 224 blood samples taken from women with ovarian cancer or from controls. It identified 95 percent of the cancers, and its false positive rate — detecting a cancer that was not there — was 0.6 percent.

But Dr. Beth Y. Karlan, director of the Women's Cancer Research Institute at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, said the samples tested were not representative of what might be encountered in routine screening. There were very few blood samples from women with early stages of the most deadly type of ovarian cancer. "That's really what we want to find," she said.

The biggest concern is not that the test will miss cancers but that it will say a cancer is there when it is not. That would then subject women to needless surgery to have their ovaries removed.

Dr. Berchuck of Duke said only 1 of 3,000 women has ovarian cancer. So even if a screening test had a 1 percent rate of false positives, it would mean that 30 out of 3,000 women tested might be subject to unnecessary surgery for every one real case of cancer.

Teresa Hills, who had a visible mass on her left ovary, got a positive result from OvaSure. But when the ovary was removed, the mass turned out to be benign.

The false positive did not prompt unnecessary surgery because Ms. Hills was going to have the mass removed in any case. But it did cause needless anxiety.

"You can't sleep, you can't eat, you're paralyzed with fear," said Ms. Hills, a 44-year-old mother of three from Rockford, Ill. She said she lost 10 pounds in two weeks after the false diagnosis.

Dr. Lai-Goldman at LabCorp said that OvaSure should be restricted to women at high risk of ovarian cancer and that the test should be repeated if the result is positive. Those measures would limit the number of false positives.

LabCorp estimates that there are 10 million women at high risk. These include carriers of mutations in genes called BRCA1 or BRCA2, as well as women with histories of ovarian or breast cancer.

Dr. Gil Mor, the lead developer of the test at Yale, said the use of OvaSure might reduce ovarian surgeries, not increase them. That is because women with BRCA mutations often have their ovaries removed to prevent cancer. A negative result on the OvaSure test might allow such women to put off the surgery.

"They are removing the ovaries without the test," said Dr. Mor, an associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology. "So what are we talking about here? We are trying to do the opposite and say don't remove the ovaries."

That logic appeals to some. Dr. Elizabeth Poyner, a gynecologic oncologist in Manhattan with a lot of high-risk patients, said she was thinking about how to incorporate OvaSure into her practice. One of her patients, a Manhattan woman with a BRCA2 mutation, said she was planning to take the test in hopes of postponing ovary removal.

"I'd really like a couple of more years to have the heart health and the bone health and all the benefits that come from having estrogen naturally," said the woman, who is in her early 40s and spoke on the condition she not be identified because she had not told some relatives that she has the mutation.

But Dr. Julian C. Schink, director of gynecologic oncology at Northwestern University, said it would be "playing Russian roulette" to put off ovary surgery unless OvaSure detected cancer. "We just don't have any data to show this test will turn positive before the disease turns metastatic," he said.

The test is also not intended to detect the recurrence of cancer. Jean McKibben, a retired schoolteacher from Centennial, Colo., said her test result suggested zero probability that her cancer had returned. But scans then found a tumor. Only later did Ms. McKibben learn that the test does not work for women whose ovaries have been removed.

The ovarian cancer detection field has had disappointments before. Four years ago, the F.D.A. intervened to effectively stop the marketing of another complex ovarian cancer screening test developed by a company called Correlogic Systems. The test, called OvaCheck, had also spurred great hope, but never made it to market as experts questioned its validity.

With the number of genetic and other tests proliferating, the agency has been under pressure to assure that the tests are accurate. Two years ago, the agency said it intended to regulate complex tests, like OvaSure, that measure multiple proteins or genes and use a mathematical formula to compute a result. But it has not finalized the policy.

Peter J. Levine, president of Correlogic, said the company was developing a new ovarian screening test and would apply by the end of the year for F.D.A. approval. He said it would be unfair if LabCorp did not need approval.

Another company, Vermillion, applied to the F.D.A. in June for approval of a test, called OVA1, aimed at determining whether ovarian masses are cancerous.

Dr. Daniel Schultz, who oversees diagnostic tests for the F.D.A., said the agency was trying to balance demands for greater oversight of tests against concerns that regulation could impede development of needed diagnostics.

"We understand that concerns have been raised regarding the impact that F.D.A. regulation would have on this whole field," he said.

Even if OvaSure is validated, or a better test is developed, questions will remain on whether screening is useful, similar to controversies that have arisen about prostate cancer screening.

Dr. Berchuck of Duke said it had not been proved that a test that detects cancer early would cut deaths from the disease. It could be that cancers detected early were the less aggressive ones that would not have killed the woman anyway.

Some experts say women should pay more attention to symptoms, like pain and bloating. But these symptoms can also be caused by other conditions.

The Canary Foundation, which finances research on early cancer detection, is focusing on developing better imaging techniques. Transvaginal ultrasound, which is sometimes used now, is not that good at detecting early disease.

"Too much of the dialogue has been on how good is the blood test," said Don Listwin, a Silicon Valley executive who started the foundation after his mother died from ovarian cancer that was diagnosed late. "They thought it was a bladder infection."

Mr. Listwin said mammograms and the P.S.A. test were fairly unreliable in detecting breast and prostate cancer, respectively. Yet they can be used for screening because a positive test result can be followed by a needle biopsy to confirm whether cancer is present.

But it is difficult to do a biopsy of the ovary because of its location, so a positive blood test result might lead directly to surgery. If imaging could be used for confirmation, he said, then even a somewhat inaccurate blood test might suffice for screening.

Ovarian Cancer

Diagnosis and Staging

Diagnosis

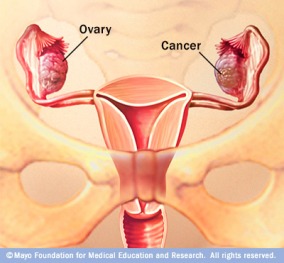

If ovarian cancer is suspected due to physical symptoms or physical exam then there are specific tests that will help with the diagnosis. Your doctor may recommend radiographic studies such as ultrasound, x-ray, abdominal and pelvic CT scan, or MRI. Laboratory blood tests commonly include a CA-125 and a chemistry profile looking at liver function. Other minor surgical procedures that may be done to gather more diagnostic information include removal of fluid from the abdominal cavity (called paracentesis) or fluid from around the lungs (called thoracentesis) using special needles. The fluid is examined under the microscope for cancer cells. These minor procedures can confirm the presence of cancer, but cannot make the diagnosis of ovarian cancer with certainty. Ovarian cancer is diagnosed at the time of surgery. Actual tissue from the ovarian tumor itself is the only absolute method to confirm a diagnosis of ovarian cancer. Biopsies are taken from the tumor tissue and sent to the pathologist for examination under the microscope.

Laparotomy (a surgical procedure which involves opening the abdominal cavity for examination) is the most certain way of diagnosing ovarian cancer and assessing if the cancer has spread to surrounding organs(metastasis).. During surgery a section of the tumor will be given to a pathologist for an immediate review. If the preliminary report is ovarian cancer, the surgeon will perform a more extensive surgery to determine the stage of the cancer.

To prepare for a major surgical procedure, a chest x-ray will be included in the preoperative evaluation to determine if there is any cancer spread to the lungs and to assure that the lungs are healthy for surgery. If there are any gastrointestinal symptoms or suspicion of cancer involvement, special x-rays of the bowel (barium enema or colonoscopy) may be indicated, as well as a bowel preparation (enemas and medication) to cleanse the colon.

Women who have not had a recent mammogram may have one performed at this time and an ECG (electrocadiogram--a test that measures the electrical conduction of the heart) if over age 45. Routine preoperative laboratory tests include blood serum chemistries, liver and kidney function tests, a CBC (complete blood count) blood typing for potential transfusions, urinalysis, a baseline CA-125 (if not already done) and a pregnancy test, if appropriate. Additional tests or special medications may be ordered depending on the individual patients' age and general health.

Staging

The stage of a cancer indicates the extent of disease or how widespread it is, i.e. is the cancer confined to the organ of origin or has it spread to the other nearby areas, lymph nodes or distant organs.

Staging of ovarian cancer is a highly skilled surgical operation and is performed during the primary (initial) surgery to remove as much of the cancer as possible. Surgical staging is of critical importance in the management of the disease since both treatment and prognosis (a prediction about the likely outcome or course of the disease) strongly depend on an accurate stage. It is based on an understanding of the patterns of disease spread and must be performed in a systematic and thorough manner. A gynecologic oncologist is a gynecological surgeon specifically trained to perform these types of operations. It is recommended that a gynecological oncologist be consulted prior to any ovarian cancer surgery.

The staging system for ovarian cancer was developed by the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO, 1998) and is used uniformly in all developed countries.

Although there are subcategories to each stage, the basic four stages of ovarian cancer are:

Stage I

The cancer is confined to one or both ovaries. Tumor may be found on the surface of the ovary.

93.6%

5-year survival

Stage II

The cancer involves one or both ovaries with extension into the pelvic region, e.g., it is found in the uterus, fallopian tubes, bladder, sigmoid colon or rectum. Few women are diagnosed at this stage.

Not available

Stage III

The cancer has spread beyond the pelvis to the abdominal wall or abdomen, small bowel, lymph nodes or liver surface.

68.1%*

5-year survival

Stage IV

This is the most advanced form of ovarian cancer. Stage IV cancers have spread to distant organs such as the liver (spread beyond just the surface of the liver), spleen or lung.

29.1%

5-year survival

* Relative 5-year survival rates from ACS Cancer Facts & Figures, 2007

Grading

The grade of a cancer (the histologic grade) measures how abnormal or malignant its' cells look under the microscope. Tumors are graded on a scale of 0 to 3, with grade 0 tumors representing non-invasive tumors of low malignant potential (LMP), also called borderline tumors. Grade 1 tumors look most like normal tissue (called well differentiated), grade 2 look somewhat like normal tissue (called moderately well differentiated) and grade 3 tumors appear very abnormal (called poorly differentiated or undifferentiated). Grade 1 tumors have the best prognosis, while grade 3 tumors are the most serious.. The histologic grade seems to correlate roughly with the biological aggressiveness of the tumor.

Prognostic Factors

The prognosis, or predicted likely outcome of the disease (chance of recovery or recurrence), of ovarian cancer depends on a number of factors. Of primary importance and significance is the stage of disease as well as the amount or volume of residual disease (the amount of cancer remaining in the abdomen or pelvis after primary surgery).

Other factors that influence survival are the histologic cell type, the cancer grade, age, performance status, and the volume of ascites (fluid in the abdomen), if present. Favorable/low risk prognostic factors include early or limited stage, low histologic grade, non-clear cell histology, none to minimal residual disease (less than one centimeter,1cm), younger age, and a good performance status.

Patterns of Metastasis

When cancer spreads to other organs or areas of the body, it is called metastasis. In ovarian cancer, metastasis can occur in four ways.

Common areas for ovarian cancer spread include the lining of the abdomen or pelvis (peritoneum), organs of the abdomen such as the bowel, bladder, uterus, liver and lungs.

Recurrent Ovarian Cancer

If ovarian cancer returns more than 6 months after the completion of therapy, it is called a "persistent ovarian cancer," and its original stage still applies. If the cancer reoccurs within 6 months after the completion of therapy it may be referred to as “persistant ovarian cancer.”

Doubts on Ovarian Cancer Relapse Test

By Andrew Pollack : NY Times Article : June 1, 2009

In a finding that is likely to shake up medical practice, researchers reported here that early detection of a relapse of ovarian cancer with a widely used blood test does not help women live longer.

The finding goes against the common presumption that early detection and treatment of cancer is better. It could force doctors and patients to re-evaluate the need for the periodic testing that has become an anxiety-inducing but also reassuring ritual for many women who have had ovarian cancer.

Most women who are in remission from ovarian cancer take the test, which measures levels of a protein called CA125, every three months or more frequently. The test can detect the recurrence of the cancer months before symptoms appear, allowing patients to start chemotherapy earlier.

But the new study, presented at the annual meeting here of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, found that women who started chemotherapy early based on a test result did not live longer than women who waited until symptoms appeared.

“For the first time, women can be reassured that there’s no benefit to early detection of relapse from routine CA125 testing,” said Dr. Gordon J. S. Rustin, director of medical oncology at Mount Vernon Hospital in Middlesex, England, and the lead author of the study. He said women could safely forgo such testing.

The finding is another in a series suggesting that early detection of cancer might not always lead to better outcomes for patients. A study published in March, for instance, suggested that early detection of prostate cancer using the PSA blood test did not help men live longer but did lead to unnecessary treatments.

This new study does not refer to initial diagnosis of ovarian cancer, only to a relapse. Doctors are convinced that if the initial diagnosis can be made early, which is very difficult, the cancer can be treated by surgery. But for relapsed ovarian cancer, surgery is usually not an option.

Dr. Beth Karlan, director of gynecologic oncology at Cedars Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, said the results of the new trial would “make us all rethink the approach to treating patients with recurrent ovarian cancer.”

Dr. Karlan, who was not involved in the study but presented a commentary on it, said CA125 testing should be done less frequently. But she stopped short of saying it should be eliminated, saying that in any event, patients would not accept that.

“Many women often say they live from one CA125 to the next,” she said.

The new study, done in Britain and nine other countries, compared 265 women who began chemotherapy after their CA125 levels began to rise with 264 women who waited to begin chemotherapy until they had symptoms, like abdominal bloating or pain.

The group getting the test began chemotherapy a median of about five months earlier. But the overall median survival for the groups was the same, about 41 months from the start of their remission. Moreover, the extra chemotherapy seemed to worsen the quality of life.

Dr. Rustin said the explanation for the counterintuitive results was not that CA125 was a poor predictor of cancer’s return. Rather, he said, some cancers were sensitive to chemotherapy, so it did not matter if they were treated early. Other tumors were resistant to chemotherapy and would not respond to treatment no matter when it was given.

Dr. Andrew Berchuck, director of gynecologic oncology at Duke University, said that while “it’s the American way, sort of, to be aggressive” and treat early, some doctors and patients even now did not start chemotherapy when CA125 rises.

“I’ve had patients who wouldn’t dream of not being treated,” Dr. Berchuck said. “But there are also people who wouldn’t want to go back on chemo unless they absolutely have to.”

Diane Paul, an ovarian cancer survivor and patient advocate in Brooklyn, said that when she was getting the CA125 test, she asked her doctors not to tell her the results, to reduce her anxiety. “I was in a constant state of agitation, waiting for the test, waiting for the results,” she said.

But others would prefer to know. “This makes me feel in control of this disease,” said Carol Tawney of Shawnee, Kan., a seven-year survivor who has her CA125 tested every two months.

The symptoms to watch out for are -

Ovarian cancer is a serious and under-recognized threat to womens health.

- Ovarian cancer kills more women than all the Gynecologic Oncology combined.

- Ovarian cancer is the fourth leading cause of cancer death among women in the United States.

- Ovarian cancer occurs in 1 in 57 women, up from 1 in 70 several years ago.

- Deaths from ovarian have risen. 2004 statistics released from the American Cancer Society show that ovarian cancer deaths have risen by close to 20% over 2003 statistics.

- More than 16,000 women will die this year alone and more than 25,500 will be diagnosed.

Ovarian cancer is very treatable when caught early; the vast majority of cases are not diagnosed until too late.

- When ovarian cancer is caught before it has spread outside the ovaries, 90+% will survive 5 years.

- Only 24% of ovarian cancer is caught early.

- When diagnosed after the disease has spread the chance of five-year survival drops to less than 25%.

Ovarian cancer is difficult to diagnose

- There is no reliable screening test for the early detection of ovarian cancer. The Pap smear only checks for cervical cancer.

- Symptoms are often vague and easily confused with other diseases. However, new studies indicate that ovarian cancer has recognizable symptoms, even early stage disease. Knowing those symptoms can help save women's lives.

Raise Your Awareness

Early recognition of symptoms is the best way to save women's lives. Early symptoms include:

- Bloating, a feeling of fullness, gas

- Frequent or urgent urination

- Nausea, indigestion, constipation, diarrhea

- Menstrual disorders, pain during intercourse

- Fatigue, backaches.

If ovarian cancer is suspected, ask to see a gynecological oncologist.

What You Should Ask Your Doctor:

While everyone has these symptoms from time to time, it is important to know your own body and know when something is not right.

If you have these symptoms and they are not normal for you neither you nor your doctor knows why you are having them,

Then ask to have these important tests to help you rule out ovarian cancer.

- Bimanual pelvic exam

- Ca125 blood test (If it comes back elevated, ask your doctor to repeat this test monthly for several months. If it comes back progressively more elevated each time, even if the values are low, this is an indication that the condition could very likely be serious.)

- Transvaginal ultrasound

Who Has the Greatest Risk?

- Have 2 or more relatives who have had ovarian cancer

- Have a family history of multiple cancers: ovarian, breast or colon cancer

- Were diagnosed with breast cancer under the age of 50

- Have a personal history of multiple exposures to fertility drugs

- Are of Ashkenazi Jewish decent

- Have had uninterrupted ovulation (never used birth control pills, or no pregnancies)

- Have the BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene mutation

- Are over the age of 50

Symptoms Found for Early Check on Ovary Cancer

By Denise Grady : NY Times Article : June 13, 2007

Cancer experts have identified a set of health problems that may be symptoms of ovarian cancer, and they are urging women who have the symptoms for more than a few weeks to see their doctors.

The new advice is the first official recognition that ovarian cancer, long believed to give no warning until it was far advanced, does cause symptoms at earlier stages in many women.

The symptoms to watch out for are bloating, pelvic or abdominal pain, difficulty eating or feeling full quickly and feeling a frequent or urgent need to urinate. A woman who has any of those problems nearly every day for more than two or three weeks is advised to see a gynecologist, especially if the symptoms are new and quite different from her usual state of health.

Doctors say they hope that the recommendations will make patients and doctors aware of early symptoms, lead to earlier diagnosis and, perhaps, save lives, or at least prolong survival.

But it is too soon to tell whether the new measures will work or whether they will lead to a flood of diagnostic tests or even unnecessary operations.

Cancer experts say it is worth trying a more aggressive approach to finding ovarian cancer early. The disease is among the deadlier types of cancer, because most cases are diagnosed late, after the cancer has begun to spread.

This year, 22,430 new cases and 15,280 deaths are expected in the United States.

If the cancer is found and surgically removed early, before it spreads outside the ovary, 93 percent of patients are still alive five years later. Only 19 percent of cases are found that early, and 45 percent of all women with the disease survive at least five years after the diagnosis.

By contrast, among women with breast cancer, 89 percent survive five years or more.

The new recommendations, expected to be formally announced on June 25, are being made by the Gynecologic Cancer Foundation, the Society of Gynecologic Oncologists and the American Cancer Society.

More than 12 other groups have endorsed them, including CancerCare; Gilda’s Club, a support network for anyone touched by cancer; and several medical societies.

“The majority of the time this won’t be ovarian cancer, but it’s just something that should be considered,” said Dr. Barbara Goff, the director of gynecologic oncology at the University of Washington in Seattle and an author of several studies that helped identify the relevant symptoms.

In a number of studies by Dr. Goff and other researchers, these symptoms stood out in women with ovarian cancer as compared with other women.

“We don’t want to scare people, but we also want to arm people with the appropriate information,” said Dr. Goff, who is also a spokeswoman for the Gynecologic Cancer Foundation.

She emphasized that relatively new and persistent problems were the most important ones. So, the transient bloating that often accompanies menstrual periods would not qualify, nor would a lifelong history of indigestion.

Dr. Goff also acknowledged that the urinary problems on the list were classic symptoms of bladder infections, which is common in women. But it still makes sense to consult a doctor, she said, because bladder infections should be treated. Urinary trouble that persists despite treatment is a particular cause for concern, she said.

With ovarian cancer, even a few months’ delay in making the diagnosis may make a difference in survival, because the tumors can grow and spread quickly through the abdomen to the intestines, liver, diaphragm and other organs, Dr. Goff said.

“If you let it go for three months, you can wind up with disease everywhere,” she said

Dr. Thomas J. Herzog, director of gynecologic oncology at the Columbia University Medical Center, said the recommendations were important because the medical profession had until now told women that there were no specific early symptoms.

“If women were more pro-active at recognizing these symptoms, we’d be better at making the diagnosis at an earlier stage,” Dr. Herzog said.

“These are nonspecific symptoms that many people have,” he added. “But when the symptoms persist or worsen, you need to see a specialist. By no means do we want this to result in unnecessary surgery. But I would not expect that to occur in the vast majority of cases.”

Although the American Cancer Society agreed to the recommendations, it did so with some reservations, said Debbie Saslow, director of breast and gynecologic cancer at the society.

“We don’t have any consensus about what doctors should do once the women come to them,” Dr. Saslow said. “There was a lot of hope that we’d be able to say, ‘Go to your doctor, and they will give you this standardized work-up.’ But we can’t do that.”

At the same time, Dr. Saslow said, the cancer society recognized that in some cases doctors had disregarded symptoms in women who were later found to have ovarian cancer, telling the women instead that they were just growing old or going through menopause.

“There are so many horror stories of doctors who have told women to ignore these symptoms or have even belittled them on top of that,” Dr. Saslow said.

In a survey of 1,700 women with ovarian cancer, Dr. Goff and other researchers found that 36 percent had initially been given a wrong diagnosis, with conditions like depression or irritable bowel syndrome.

“Twelve percent were told there was nothing wrong with them, and it was all in their heads,” Dr. Goff said.

Dr. Goff and other specialists said women with the listed symptoms should see a gynecologist for a pelvic and rectal examination. (The best way for a doctor to feel the ovaries is through the rectum.) If there is a question of cancer, the next step is probably a test called a transvaginal ultrasound to check the ovaries for abnormal growths, enlargement or telltale pockets of fluid that can signal cancer. The ultrasound costs $150 to $300 and can be performed in a doctor’s office or a radiology center. A $100 blood test should also be conducted for CA125, a substance called a tumor marker that is often elevated in women with ovarian cancer.

Cancer specialists say any woman with suspicious findings on the tests should be referred to a gynecologic oncologist, a surgeon who specializes in cancers of the female reproductive system.

An unresolved question is what exactly should be done if the test results are normal and yet the woman continues to have symptoms, Dr. Saslow said.

“Do you do exploratory surgery, which has side effects, which are sometimes even fatal?” she asked. “What do you do? We don’t have the answer to that.”

Depending on the test results, the woman may just be monitored for a while or advised to undergo a CT scan or an MRI. But if cancer is strongly suspected, she will probably be urged to go straight to surgery. A needle biopsy, commonly used for breast lumps, cannot be safely performed to check for ovarian cancer because it runs a risk of rupturing the tumor and spreading malignant cells in the abdomen. Instead, the surgeon must carefully remove the entire ovary or the abnormal growth on it and examine the rest of the abdomen for cancer.

While the patient is still on the operating table, biopsies are performed on the tissue that was removed, so that if cancer is found, the surgeon can operate more extensively. Experts say such an operation should be carried out just by gynecologic oncologists, who have special training in meticulously removing as much of the cancerous tissue as possible. This procedure, called debulking, lets chemotherapy work better and greatly improves survival.

Dr. Carol L. Brown, a gynecologic oncologist at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in Manhattan, said, “Ideally, we need to develop a screening tool or a test to find ovarian cancer before it has symptoms.”

No such screening test exists, Dr. Brown said, and until one is developed, the list of symptoms may be the best solution.

“This is something that women themselves can do,” she added, “and we can familiarize clinicians with, to help make the diagnosis earlier.”

Cancer Test for Women Raises Hope, and Concern

By Andrew Pollack : NY Times Article : August 26, 2008

A new blood test aimed at detecting ovarian cancer at an early, still treatable stage is stirring hopes among women and their physicians. But the Food and Drug Administration and some experts say the test has not been proved to work. [They have as a result not approved its usage, but the article is interesting]

The test, called OvaSure, was developed at Yale and has been offered since late June by LabCorp, one of the nation's largest clinical laboratory companies.

The need for such a test is immense. When ovarian cancer is detected at its earliest stage, when it is still confined to the ovaries, more than 90 percent of women will live at least five years, according to the American Cancer Society. But only about 20 percent of cases are detected that early. If the cancer is detected in its latest stages, after it has spread, only about 30 percent of women survive five years.

But far from greeting the new test with elation, many experts are saying it might do more harm than good, leading women to unnecessary surgeries. The Society of Gynecologic Oncologists almost immediately issued a statement saying it did not believe the test had been validated enough for routine use.

"You've got industry trying to capitalize on fear," said Dr. Andrew Berchuck, director of gynecologic oncology at Duke University and the immediate past president of the society. "We'd all love to see a screening test for ovarian cancer," he added, "but OvaSure is very premature."

OvaSure's debut also raises questions about whether greater regulation is needed to assure the validity of a trove of sophisticated new diagnostic tests that are entering the market and are being used as the basis for important treatment decisions. OvaSure did not go through review by the Food and Drug Administration because the agency generally has not regulated tests developed and performed by a single laboratory, as opposed to test kits that are sold to laboratories, hospitals and doctors. (All OvaSure blood samples are sent to LabCorp for analysis.)

But the F.D.A. has now summoned LabCorp to discuss OvaSure, saying the data appear insufficient to back the company's claims about the test. "We believe you are offering a high-risk test that has not received adequate clinical validation and may harm the public health," the agency said in an Aug. 7 letter sent to LabCorp that was posted on the F.D.A. Web site. A spokesman for LabCorp, which is short for Laboratory Corporation of America Holdings, said the company looked forward to reviewing the data with the agency but would continue offering the test in the meantime.

Dr. Myla Lai-Goldman, chief medical officer of LabCorp, said that OvaSure had been validated in several studies and that additional data were expected by the end of this year. Diagnostic tests typically are studied further after they have reached the market, she said. Dr. Goldman said there was "tremendous interest" from physicians in learning more about OvaSure.

Patients and advocacy groups seem divided on OvaSure, which costs about $220 to $240.

"We are hearing from people that they are very excited about it," said Cara Tenenbaum, policy director for the Ovarian Cancer National Alliance. But the alliance urges women to wait for more data before relying on the test.

More than 21,000 new cases of ovarian cancer will be diagnosed in the United States this year and more than 15,000 people are expected to die from the disease, according to the American Cancer Society.

OvaSure measures the level of six proteins in a sample of blood, some produced by a tumor and some produced by the body in reaction to a tumor. It then calculates a probability that the woman has ovarian cancer. One of the six proteins is CA-125, which is used by itself as a test to monitor disease progression in women who already have ovarian cancer but is not good at picking up early disease.

In a study published in the journal Clinical Cancer Research in February, the test correctly classified 221 of 224 blood samples taken from women with ovarian cancer or from controls. It identified 95 percent of the cancers, and its false positive rate — detecting a cancer that was not there — was 0.6 percent.

But Dr. Beth Y. Karlan, director of the Women's Cancer Research Institute at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, said the samples tested were not representative of what might be encountered in routine screening. There were very few blood samples from women with early stages of the most deadly type of ovarian cancer. "That's really what we want to find," she said.

The biggest concern is not that the test will miss cancers but that it will say a cancer is there when it is not. That would then subject women to needless surgery to have their ovaries removed.

Dr. Berchuck of Duke said only 1 of 3,000 women has ovarian cancer. So even if a screening test had a 1 percent rate of false positives, it would mean that 30 out of 3,000 women tested might be subject to unnecessary surgery for every one real case of cancer.

Teresa Hills, who had a visible mass on her left ovary, got a positive result from OvaSure. But when the ovary was removed, the mass turned out to be benign.

The false positive did not prompt unnecessary surgery because Ms. Hills was going to have the mass removed in any case. But it did cause needless anxiety.

"You can't sleep, you can't eat, you're paralyzed with fear," said Ms. Hills, a 44-year-old mother of three from Rockford, Ill. She said she lost 10 pounds in two weeks after the false diagnosis.

Dr. Lai-Goldman at LabCorp said that OvaSure should be restricted to women at high risk of ovarian cancer and that the test should be repeated if the result is positive. Those measures would limit the number of false positives.

LabCorp estimates that there are 10 million women at high risk. These include carriers of mutations in genes called BRCA1 or BRCA2, as well as women with histories of ovarian or breast cancer.

Dr. Gil Mor, the lead developer of the test at Yale, said the use of OvaSure might reduce ovarian surgeries, not increase them. That is because women with BRCA mutations often have their ovaries removed to prevent cancer. A negative result on the OvaSure test might allow such women to put off the surgery.

"They are removing the ovaries without the test," said Dr. Mor, an associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology. "So what are we talking about here? We are trying to do the opposite and say don't remove the ovaries."

That logic appeals to some. Dr. Elizabeth Poyner, a gynecologic oncologist in Manhattan with a lot of high-risk patients, said she was thinking about how to incorporate OvaSure into her practice. One of her patients, a Manhattan woman with a BRCA2 mutation, said she was planning to take the test in hopes of postponing ovary removal.

"I'd really like a couple of more years to have the heart health and the bone health and all the benefits that come from having estrogen naturally," said the woman, who is in her early 40s and spoke on the condition she not be identified because she had not told some relatives that she has the mutation.

But Dr. Julian C. Schink, director of gynecologic oncology at Northwestern University, said it would be "playing Russian roulette" to put off ovary surgery unless OvaSure detected cancer. "We just don't have any data to show this test will turn positive before the disease turns metastatic," he said.

The test is also not intended to detect the recurrence of cancer. Jean McKibben, a retired schoolteacher from Centennial, Colo., said her test result suggested zero probability that her cancer had returned. But scans then found a tumor. Only later did Ms. McKibben learn that the test does not work for women whose ovaries have been removed.

The ovarian cancer detection field has had disappointments before. Four years ago, the F.D.A. intervened to effectively stop the marketing of another complex ovarian cancer screening test developed by a company called Correlogic Systems. The test, called OvaCheck, had also spurred great hope, but never made it to market as experts questioned its validity.

With the number of genetic and other tests proliferating, the agency has been under pressure to assure that the tests are accurate. Two years ago, the agency said it intended to regulate complex tests, like OvaSure, that measure multiple proteins or genes and use a mathematical formula to compute a result. But it has not finalized the policy.

Peter J. Levine, president of Correlogic, said the company was developing a new ovarian screening test and would apply by the end of the year for F.D.A. approval. He said it would be unfair if LabCorp did not need approval.

Another company, Vermillion, applied to the F.D.A. in June for approval of a test, called OVA1, aimed at determining whether ovarian masses are cancerous.

Dr. Daniel Schultz, who oversees diagnostic tests for the F.D.A., said the agency was trying to balance demands for greater oversight of tests against concerns that regulation could impede development of needed diagnostics.

"We understand that concerns have been raised regarding the impact that F.D.A. regulation would have on this whole field," he said.

Even if OvaSure is validated, or a better test is developed, questions will remain on whether screening is useful, similar to controversies that have arisen about prostate cancer screening.

Dr. Berchuck of Duke said it had not been proved that a test that detects cancer early would cut deaths from the disease. It could be that cancers detected early were the less aggressive ones that would not have killed the woman anyway.

Some experts say women should pay more attention to symptoms, like pain and bloating. But these symptoms can also be caused by other conditions.

The Canary Foundation, which finances research on early cancer detection, is focusing on developing better imaging techniques. Transvaginal ultrasound, which is sometimes used now, is not that good at detecting early disease.

"Too much of the dialogue has been on how good is the blood test," said Don Listwin, a Silicon Valley executive who started the foundation after his mother died from ovarian cancer that was diagnosed late. "They thought it was a bladder infection."

Mr. Listwin said mammograms and the P.S.A. test were fairly unreliable in detecting breast and prostate cancer, respectively. Yet they can be used for screening because a positive test result can be followed by a needle biopsy to confirm whether cancer is present.

But it is difficult to do a biopsy of the ovary because of its location, so a positive blood test result might lead directly to surgery. If imaging could be used for confirmation, he said, then even a somewhat inaccurate blood test might suffice for screening.

Ovarian Cancer

Diagnosis and Staging

Diagnosis

If ovarian cancer is suspected due to physical symptoms or physical exam then there are specific tests that will help with the diagnosis. Your doctor may recommend radiographic studies such as ultrasound, x-ray, abdominal and pelvic CT scan, or MRI. Laboratory blood tests commonly include a CA-125 and a chemistry profile looking at liver function. Other minor surgical procedures that may be done to gather more diagnostic information include removal of fluid from the abdominal cavity (called paracentesis) or fluid from around the lungs (called thoracentesis) using special needles. The fluid is examined under the microscope for cancer cells. These minor procedures can confirm the presence of cancer, but cannot make the diagnosis of ovarian cancer with certainty. Ovarian cancer is diagnosed at the time of surgery. Actual tissue from the ovarian tumor itself is the only absolute method to confirm a diagnosis of ovarian cancer. Biopsies are taken from the tumor tissue and sent to the pathologist for examination under the microscope.

Laparotomy (a surgical procedure which involves opening the abdominal cavity for examination) is the most certain way of diagnosing ovarian cancer and assessing if the cancer has spread to surrounding organs(metastasis).. During surgery a section of the tumor will be given to a pathologist for an immediate review. If the preliminary report is ovarian cancer, the surgeon will perform a more extensive surgery to determine the stage of the cancer.

To prepare for a major surgical procedure, a chest x-ray will be included in the preoperative evaluation to determine if there is any cancer spread to the lungs and to assure that the lungs are healthy for surgery. If there are any gastrointestinal symptoms or suspicion of cancer involvement, special x-rays of the bowel (barium enema or colonoscopy) may be indicated, as well as a bowel preparation (enemas and medication) to cleanse the colon.

Women who have not had a recent mammogram may have one performed at this time and an ECG (electrocadiogram--a test that measures the electrical conduction of the heart) if over age 45. Routine preoperative laboratory tests include blood serum chemistries, liver and kidney function tests, a CBC (complete blood count) blood typing for potential transfusions, urinalysis, a baseline CA-125 (if not already done) and a pregnancy test, if appropriate. Additional tests or special medications may be ordered depending on the individual patients' age and general health.

Staging

The stage of a cancer indicates the extent of disease or how widespread it is, i.e. is the cancer confined to the organ of origin or has it spread to the other nearby areas, lymph nodes or distant organs.

Staging of ovarian cancer is a highly skilled surgical operation and is performed during the primary (initial) surgery to remove as much of the cancer as possible. Surgical staging is of critical importance in the management of the disease since both treatment and prognosis (a prediction about the likely outcome or course of the disease) strongly depend on an accurate stage. It is based on an understanding of the patterns of disease spread and must be performed in a systematic and thorough manner. A gynecologic oncologist is a gynecological surgeon specifically trained to perform these types of operations. It is recommended that a gynecological oncologist be consulted prior to any ovarian cancer surgery.

The staging system for ovarian cancer was developed by the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO, 1998) and is used uniformly in all developed countries.

Although there are subcategories to each stage, the basic four stages of ovarian cancer are:

Stage I

The cancer is confined to one or both ovaries. Tumor may be found on the surface of the ovary.

93.6%

5-year survival

Stage II

The cancer involves one or both ovaries with extension into the pelvic region, e.g., it is found in the uterus, fallopian tubes, bladder, sigmoid colon or rectum. Few women are diagnosed at this stage.

Not available

Stage III

The cancer has spread beyond the pelvis to the abdominal wall or abdomen, small bowel, lymph nodes or liver surface.

68.1%*

5-year survival

Stage IV

This is the most advanced form of ovarian cancer. Stage IV cancers have spread to distant organs such as the liver (spread beyond just the surface of the liver), spleen or lung.

29.1%

5-year survival

* Relative 5-year survival rates from ACS Cancer Facts & Figures, 2007

Grading

The grade of a cancer (the histologic grade) measures how abnormal or malignant its' cells look under the microscope. Tumors are graded on a scale of 0 to 3, with grade 0 tumors representing non-invasive tumors of low malignant potential (LMP), also called borderline tumors. Grade 1 tumors look most like normal tissue (called well differentiated), grade 2 look somewhat like normal tissue (called moderately well differentiated) and grade 3 tumors appear very abnormal (called poorly differentiated or undifferentiated). Grade 1 tumors have the best prognosis, while grade 3 tumors are the most serious.. The histologic grade seems to correlate roughly with the biological aggressiveness of the tumor.

Prognostic Factors

The prognosis, or predicted likely outcome of the disease (chance of recovery or recurrence), of ovarian cancer depends on a number of factors. Of primary importance and significance is the stage of disease as well as the amount or volume of residual disease (the amount of cancer remaining in the abdomen or pelvis after primary surgery).

Other factors that influence survival are the histologic cell type, the cancer grade, age, performance status, and the volume of ascites (fluid in the abdomen), if present. Favorable/low risk prognostic factors include early or limited stage, low histologic grade, non-clear cell histology, none to minimal residual disease (less than one centimeter,1cm), younger age, and a good performance status.

Patterns of Metastasis

When cancer spreads to other organs or areas of the body, it is called metastasis. In ovarian cancer, metastasis can occur in four ways.

- By direct contact or extension, it can invade nearby tissue or organs located near or around the ovary, such as the fallopian tubes, uterus, bladder, rectum, etc.

- By seeding or shedding into the abdominal cavity, which is the most common way ovarian cancer spreads. Cancer cells break off the surface of the ovarian mass and "drop" to other structures in the abdomen such as the liver, stomach, colon or diaphragm.

- By breaking loose from the ovarian mass, invading the lymphatic vessels and then traveling to other areas of the body or distant organs such as the lung or liver.

- By breaking loose from the ovarian mass, invading the blood system and traveling to other areas of the body or distant organs. This type of metastasis is rare in ovarian cancer.

Common areas for ovarian cancer spread include the lining of the abdomen or pelvis (peritoneum), organs of the abdomen such as the bowel, bladder, uterus, liver and lungs.

Recurrent Ovarian Cancer

If ovarian cancer returns more than 6 months after the completion of therapy, it is called a "persistent ovarian cancer," and its original stage still applies. If the cancer reoccurs within 6 months after the completion of therapy it may be referred to as “persistant ovarian cancer.”

Doubts on Ovarian Cancer Relapse Test

By Andrew Pollack : NY Times Article : June 1, 2009

In a finding that is likely to shake up medical practice, researchers reported here that early detection of a relapse of ovarian cancer with a widely used blood test does not help women live longer.

The finding goes against the common presumption that early detection and treatment of cancer is better. It could force doctors and patients to re-evaluate the need for the periodic testing that has become an anxiety-inducing but also reassuring ritual for many women who have had ovarian cancer.

Most women who are in remission from ovarian cancer take the test, which measures levels of a protein called CA125, every three months or more frequently. The test can detect the recurrence of the cancer months before symptoms appear, allowing patients to start chemotherapy earlier.

But the new study, presented at the annual meeting here of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, found that women who started chemotherapy early based on a test result did not live longer than women who waited until symptoms appeared.

“For the first time, women can be reassured that there’s no benefit to early detection of relapse from routine CA125 testing,” said Dr. Gordon J. S. Rustin, director of medical oncology at Mount Vernon Hospital in Middlesex, England, and the lead author of the study. He said women could safely forgo such testing.

The finding is another in a series suggesting that early detection of cancer might not always lead to better outcomes for patients. A study published in March, for instance, suggested that early detection of prostate cancer using the PSA blood test did not help men live longer but did lead to unnecessary treatments.

This new study does not refer to initial diagnosis of ovarian cancer, only to a relapse. Doctors are convinced that if the initial diagnosis can be made early, which is very difficult, the cancer can be treated by surgery. But for relapsed ovarian cancer, surgery is usually not an option.

Dr. Beth Karlan, director of gynecologic oncology at Cedars Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, said the results of the new trial would “make us all rethink the approach to treating patients with recurrent ovarian cancer.”

Dr. Karlan, who was not involved in the study but presented a commentary on it, said CA125 testing should be done less frequently. But she stopped short of saying it should be eliminated, saying that in any event, patients would not accept that.

“Many women often say they live from one CA125 to the next,” she said.

The new study, done in Britain and nine other countries, compared 265 women who began chemotherapy after their CA125 levels began to rise with 264 women who waited to begin chemotherapy until they had symptoms, like abdominal bloating or pain.

The group getting the test began chemotherapy a median of about five months earlier. But the overall median survival for the groups was the same, about 41 months from the start of their remission. Moreover, the extra chemotherapy seemed to worsen the quality of life.

Dr. Rustin said the explanation for the counterintuitive results was not that CA125 was a poor predictor of cancer’s return. Rather, he said, some cancers were sensitive to chemotherapy, so it did not matter if they were treated early. Other tumors were resistant to chemotherapy and would not respond to treatment no matter when it was given.

Dr. Andrew Berchuck, director of gynecologic oncology at Duke University, said that while “it’s the American way, sort of, to be aggressive” and treat early, some doctors and patients even now did not start chemotherapy when CA125 rises.

“I’ve had patients who wouldn’t dream of not being treated,” Dr. Berchuck said. “But there are also people who wouldn’t want to go back on chemo unless they absolutely have to.”

Diane Paul, an ovarian cancer survivor and patient advocate in Brooklyn, said that when she was getting the CA125 test, she asked her doctors not to tell her the results, to reduce her anxiety. “I was in a constant state of agitation, waiting for the test, waiting for the results,” she said.

But others would prefer to know. “This makes me feel in control of this disease,” said Carol Tawney of Shawnee, Kan., a seven-year survivor who has her CA125 tested every two months.

The symptoms to watch out for are -

- bloating

- pelvic or abdominal pain

- difficulty eating or feeling full quickly

- feeling a frequent or urgent need to urinate

- A woman who has any of those problems nearly every day for more than two or three weeks is advised to see a gynecologist, especially if the symptoms are new and quite different from her usual state of health.