- RETIREMENT ANNOUNCEMENT

- HOME PAGE

- "MYCHART" the new patient portal

- BELMONT MEDICAL ASSOCIATES

- MOUNT AUBURN HOSPITAL

- EMERGENCIES

- PRACTICE PHILOSOPHY

- MY RESUME

- TELEMEDICINE CONSULTATION

- CONTACT ME

- LAB RESULTS

- ePRESCRIPTIONS

- eREFERRALS

- RECORD RELEASE

- MEDICAL SCRIBE

- PHYSICIAN ASSISTANT (PA)

- Medicare Annual Wellness Visit

- Case management/Social work

- Quality Care Measures

- Emergency closing notice

- FEEDBACK

- Talking to your doctor

- Choosing..... and losing a doctor

- INDEX A - Z

- ALLERGIC REACTIONS

- Alternative Medicine

- Alzheimer's Disease

- Bladder Problems

- Blood disorders

- Cancer Concerns

- GENETIC TESTING FOR HEREDITARY CANCER

- Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

- Controversial Concerns

- CPR : Learn and save a life

- CRP : Inflammatory marker

- Diabetes Management

- Dizziness, Vertigo,Tinnitus and Hearing Loss

- EXERCISE

- FEMALE HEALTH

-

GASTROINTESTINAL topics

- Appendicitis

- BRAT diet

- Celiac Disease or Sprue

- Crohn's Disease

- Gastroenterologists for Colon Cancer Screening

- Colonoscopy PREP

- Constipation

- Gluten sensitivity, but not celiac disease

- Heartburn and GERD

- Hemorrhoids and Anal fissure

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- NASH : Non Alcoholic Steato Hepatitis

- FEET PROBLEMS

- HEART RELATED topics

-

INFECTIOUS DISEASES

- Antibiotic Resistance

- Cat bites >

- Clostridia difficile infection - the "antibiotic associated germ"

- CORONA VIRUS

- Dengue Fever and Chikungunya Fever

- Food borne illnesses

- Shingles Vaccine

- Hepatitis B

- Hepatitis C

- Herpes

- Influenza

- Helicobacter pylori - the "ulcer germ"

- HIV Screening

- Lyme and other tick borne diseases

- Measles

- Meningitis

- MRSA (Staph infection)

- Norovirus

- Sexually Transmitted Diseases

- Shingles (Herpes Zoster)

- Sinusitis

- West Nile Virus

- Whooping Cough (Pertussis)

- Zika virus and pregnancy

- INSURANCE related topics

- KIDNEY STONES

- LEG CRAMPS

- LIBRARY for patients

- LIFE DECISIONS

- MALE HEALTH

- Medication/Drug side effects

- MEDICAL MARIJUANA

- MENTAL HEALTH

- Miscellaneous Articles

-

NUTRITION - EXERCISE - WEIGHT

- Cholesterol : New guidelines for treatment

- Advice to lower your cholesterol

- Cholesterol : Control

- Cholesterol : Raising your HDL Level

- Exercise

- Food : Making Smart Choices

- Food : Making Poor Choices

- Food : Grape Fruit and Drug Interaction

- Food : Vitamins, Minerals and Supplements

- Omega 3 fatty acids

- Vitamin B12 deficiency

- Vitamin D

- Weight Loss

- ORTHOPEDICS

- PAIN

- PATIENTS' RIGHTS

- SKIN

- SLEEP

- SMOKING

- STROKE

- THYROID

- SUBSTANCE ABUSE

- Travel and Vaccination

- TREMOR

- Warfarin Anticoagulation

- OTHER STUFF FOLLOWS

- Fact or Opinion?

- Hippocratic Oath

- FREE ADVICE.......for what its worth!

- LAUGHTER.....is the best medicine

- Physicians Pet Peeves

- PHOTO ALBUM - its not all work!

- Cape Town, South Africa

- Tribute page

- The 100 Club

- Free Wi-Fi

Exercise

Frequency : 3 - 5 times a week

· Intensity : Work out at 60% - 90% of your heart's maximum pumping capacity. Calculate by subtracting your age from 220 and then calculating 60% (for low intensity) - 90% (for high intensity) of this figure.

· Duration : 15 -60 minutes of continuous activity

· Mode : Any activity that involves large muscle groups in continuous movement eg running, walking, hiking, swimming, bicycling, rowing, rope skipping etc

Health Clubs & Gyms - Quick Tips

1.Before you join, think skeptically about what activities you are likely to participate in and how often you’ll be able to use the club. If you haven’t exercised before or for a long time, question whether you will be able to stick with a new fitness regimen. Most people who join clubs stop using them long before their memberships expire. Since most clubs charge nonrefundable initiation fees, and many clubs require or push annual contracts, you can waste a lot of money if you quit.

2.Consider whether you can get the exercise you want less expensively some other way—for example, by doing push-ups, sit-ups, and running on your own; by joining a sports team or exercise program; or by using a government-sponsored facility.

3.Shop. For roughly the same facilities, you might pay more than twice as much at some clubs as at others.

4.Be sure to press clubs you are considering for their best deals. When you are negotiating, get clubs to compete by mentioning other clubs you are considering. Many clubs have various fee plans and discount options and offer the best deals only if necessary to get the sale. Don’t allow sales staff to pressure you into making a decision. Check to see whether you qualify for a discounted rate due to an arrangement between your employer or health plan and the club. Find out about clubs’ rules on canceling a membership, selling a membership to someone else, and freezing a membership.

5.Try out any club you are considering by asking it for a guest pass to use. When you are there, check out the cleanliness and the condition of equipment, ask other members how crowded the club gets at hours when you might want to be there, and judge how helpful the staff is.

Stretching: The Truth

By Gretchen Reynolds : NY Times Article : November 2, 2008

When Duane Knudson, a professor of kinesiology at California State University, Chico, looks around campus at athletes warming up before practice, he sees one dangerous mistake after another. "They're stretching, touching their toes. . . . " He sighs. "It's discouraging."

If you're like most of us, you were taught the importance of warm-up exercises back in grade school, and you've likely continued with pretty much the same routine ever since. Science, however, has moved on. Researchers now believe that some of the more entrenched elements of many athletes' warm-up regimens are not only a waste of time but actually bad for you. The old presumption that holding a stretch for 20 to 30 seconds — known as static stretching — primes muscles for a workout is dead wrong. It actually weakens them. In a recent study conducted at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, athletes generated less force from their leg muscles after static stretching than they did after not stretching at all. Other studies have found that this stretching decreases muscle strength by as much as 30 percent. Also, stretching one leg's muscles can reduce strength in the other leg as well, probably because the central nervous system rebels against the movements.

"There is a neuromuscular inhibitory response to static stretching," says Malachy McHugh, the director of research at the Nicholas Institute of Sports Medicine and Athletic Trauma at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York City. The straining muscle becomes less responsive and stays weakened for up to 30 minutes after stretching, which is not how an athlete wants to begin a workout.

THE RIGHT WARM-UP should do two things: loosen muscles and tendons to increase the range of motion of various joints, and literally warm up the body. When you're at rest, there's less blood flow to muscles and tendons, and they stiffen. "You need to make tissues and tendons compliant before beginning exercise," Knudson says.

A well-designed warm-up starts by increasing body heat and blood flow. Warm muscles and dilated blood vessels pull oxygen from the bloodstream more efficiently and use stored muscle fuel more effectively. They also withstand loads better. One significant if gruesome study found that the leg-muscle tissue of laboratory rabbits could be stretched farther before ripping if it had been electronically stimulated — that is, warmed up.

To raise the body's temperature, a warm-up must begin with aerobic activity, usually light jogging. Most coaches and athletes have known this for years. That's why tennis players run around the court four or five times before a match and marathoners stride in front of the starting line. But many athletes do this portion of their warm-up too intensely or too early. A 2002 study of collegiate volleyball players found that those who'd warmed up and then sat on the bench for 30 minutes had lower backs that were stiffer than they had been before the warm-up. And a number of recent studies have demonstrated that an overly vigorous aerobic warm-up simply makes you tired. Most experts advise starting your warm-up jog at about 40 percent of your maximum heart rate (a very easy pace) and progressing to about 60 percent. The aerobic warm-up should take only 5 to 10 minutes, with a 5-minute recovery. (Sprinters require longer warm-ups, because the loads exerted on their muscles are so extreme.) Then it's time for the most important and unorthodox part of a proper warm-up regimen, the Spider-Man and its counterparts.

"TOWARDS THE end of my playing career, in about 2000, I started seeing some of the other guys out on the court doing these strange things before a match and thinking, What in the world is that?" says Mark Merklein, 36, once a highly ranked tennis player and now a national coach for the United States Tennis Association. The players were lunging, kicking and occasionally skittering, spider-like, along the sidelines. They were early adopters of a new approach to stretching.

While static stretching is still almost universally practiced among amateur athletes — watch your child's soccer team next weekend — it doesn't improve the muscles' ability to perform with more power, physiologists now agree. "You may feel as if you're able to stretch farther after holding a stretch for 30 seconds," McHugh says, "so you think you've increased that muscle's readiness." But typically you've increased only your mental tolerance for the discomfort of the stretch. The muscle is actually weaker.

Stretching muscles while moving, on the other hand, a technique known as dynamic stretching or dynamic warm-ups, increases power, flexibility and range of motion. Muscles in motion don't experience that insidious inhibitory response. They instead get what McHugh calls "an excitatory message" to perform.

Dynamic stretching is at its most effective when it's relatively sports specific. "You need range-of-motion exercises that activate all of the joints and connective tissue that will be needed for the task ahead," says Terrence Mahon, a coach with Team Running USA, home to the Olympic marathoners Ryan Hall and Deena Kastor. For runners, an ideal warm-up might include squats, lunges and "form drills" like kicking your buttocks with your heels. Athletes who need to move rapidly in different directions, like soccer, tennis or basketball players, should do dynamic stretches that involve many parts of the body. "Spider-Man" is a particularly good drill: drop onto all fours and crawl the width of the court, as if you were climbing a wall. (For other dynamic stretches, see the sidebar below.)

Even golfers, notoriously nonchalant about warming up (a recent survey of 304 recreational golfers found that two-thirds seldom or never bother), would benefit from exerting themselves a bit before teeing off. In one 2004 study, golfers who did dynamic warm- up exercises and practice swings increased their clubhead speed and were projected to have dropped their handicaps by seven strokes over seven weeks.

Controversy remains about the extent to which dynamic warm-ups prevent injury. But studies have been increasingly clear that static stretching alone before exercise does little or nothing to help. The largest study has been done on military recruits; results showed that an almost equal number of subjects developed lower-limb injuries (shin splints, stress fractures, etc.), regardless of whether they had performed static stretches before training sessions. A major study published earlier this year by the Centers for Disease Control, on the other hand, found that knee injuries were cut nearly in half among female collegiate soccer players who followed a warm-up program that included both dynamic warm-up exercises and static stretching. (For a sample routine, visit www.aclprevent.com/pepprogram.htm.) And in golf, new research by Andrea Fradkin, an assistant professor of exercise science at Bloomsburg University of Pennsylvania, suggests that those who warm up are nine times less likely to be injured.

"It was eye-opening," says Fradkin, formerly a feckless golfer herself. "I used to not really warm up. I do now."

You're Getting Warmer: The Best Dynamic Stretches

These exercises- as taught by the United States Tennis Association's player-development program – are good for many athletes, even golfers. Do them immediately after your aerobic warm-up and as soon as possible before your workout.

STRAIGHT-LEG MARCH

(for the hamstrings and gluteus muscles)

Kick one leg straight out in front of you, with your toes flexed toward the sky. Reach your opposite arm to the upturned toes. Drop the leg and repeat with the opposite limbs. Continue the sequence for at least six or seven repetitions.

SCORPION

(for the lower back, hip flexors and gluteus muscles)

Lie on your stomach, with your arms outstretched and your feet flexed so that only your toes are touching the ground. Kick your right foot toward your left arm, then kick your leftfoot toward your right arm. Since this is an advanced exercise, begin slowly, and repeat up to 12 times.

HANDWALKS

(for the shoulders, core muscles, and hamstrings)

Stand straight, with your legs together. Bend over until both hands are flat on the ground. "Walk" with your hands forward until your back is almost extended. Keeping your legs straight, inch your feet toward your hands, then walk your hands forward again. Repeat five or six times. G.R.

Questions For Your Doctor : What to Ask About Exercise

By Marilynn Larkin : NY Times Article ; January 8, 2008

A new diagnosis can be a frightening experience, and ever-changing research can complicate already difficult treatment decisions. Here are some questions you might ask your doctor if exercise has been recommended as part of your treatment plan.

Why are you recommending exercise for my condition? I thought medication would be enough.

Physicians increasingly prescribe exercise as a complement to medication for a wide range of medical complaints, though it’s not a substitute for taking your drugs. Exercise may help slow progression of certain conditions, such as arthritis, Parkinson’s disease and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or improve other aspects of your health, including cardiovascular endurance and strength. Exercise can also boost mood and sense of well-being.

What kind of exercises should I do? Are there some I should avoid?

If you haven’t been exercising regularly, start by walking. And talk to your doctor first, especially if you’re over 50 or have a medical condition. He or she can recommend a physical therapist or other health professional with experience in your condition. A physical therapist can also show you how to add appropriate resistance and flexibility exercises to your routine.

Can medications affect my ability to exercise?

Some drugs may cause side effects like dizziness, so you want to be sure to choose exercises that allow you to stop and sit down if necessary. Other medications can affect heart rate, making it difficult to tell when you are exercising at or near your target heart rate.

Do I need to lose weight before I start?

Most people can embark on an exercise program regardless of weight. Begin by walking. If you can’t walk 30 minutes at a time, do shorter bouts. Exercising 10 minutes at a time, three times a day, confers similar benefits to exercising in a single 30-minute session, studies show. Increasing physical activity can also help minimize age-related weight gain.

I haven’t regularly exercised since college, and that was years ago. Can I really get benefits now?

You’re never too old to start, as the adage goes. In recent studies, people in their 70s and 80s demonstrated significant gains in strength and function from participation in a strength-training program. Older adults also get cardiovascular benefits from aerobic activity. Improving aerobic capacity and strength will make it easier to do everyday activities and allows older adults stay independent longer.

How do I get started?

Several Web-based programs can help you jump in, including the American Heart Association’s “Choose to Move” program and the “Exercise and Screening for You,” or EASY, tool from Texas A&M Health Science Center. Also see the American College of Sports Medicine’s brochure, Energy Expenditure in Different Modes of Exercise.

How much exercise should I do?

New exercise recommendations from the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association advise moderately intense aerobic exercise 30 minutes a day, five days a week, or vigorously intense aerobic exercise 20 minutes a day, three days a week. In addition, they recommend a mix of eight to 10 strength-training exercises -- on a schedule of 10 to 15 repetitions of each exercise two to three times per week for those with chronic ailments or people over 65.

Do I need to join a gym?

It’s not necessary to join a gym; all you need are a pair of athletic shoes and a little motivation. Some people find that exercising with a friend or in a group helps them stay on track.

Should I buy special equipment?

You don’t need special equipment. However, it may be helpful to invest in resistance bands or free weights to do resistance training. A stability ball to improve balance or a home exercise machine may also help. The American College of Sports Medicine offers brochures to help seniors and others make appropriate purchases and learn to use equipment properly.

I travel a lot for business. How can I keep up my exercise routine?

Know what fitness facilities are available at your hotel and in the immediate area. Plan exercise time around your business obligations. Be aware that the latest research suggests that you can take up to a week off from exercise without any significant reduction in your fitness level. During longer trips, focus on maintaining your fitness with some form of aerobic or strength training -- even though it might not be your usual routine --at least twice a week.

Post exercise recovery

By Gretchen Reynolds

NY Times Article : June 1, 2008

From the perspective of an athlete, few things top the virtuous satisfaction that comes from a hard workout. That 10-mile run, that 1,500-meter pool sprint, that hour with the free weights. Makes you feel great, right? You'll do it again tomorrow, for sure. But then it hits — the aftermath.

Within a few hours, your muscles begin sending vicious little reminders about your impressive efforts. Delayed-onset muscle soreness, as it's called, settles in roughly 12 to 24 hours after an intense bout of training, especially if it involved unfamiliar or extreme movements. The affected muscles become so tender and strained that the process of rising from bed the next morning becomes a challenge.

Even if you haven't arrived at this sorry state, repeated hard workouts can tax the body in insidious ways. Muscles, over the course of an hour or so of serious work, use up most of their stored energy. Without remediation, those muscles won't respond as well during your next workout. They'll be more prone to injury. You'll be slower. The 70-year-old from down the street will pass you on the running path.

Completing a hard workout, then, is just the first step. You also have to undo all the damage you've just done.

Start with your postworkout meal. The regeneration of your muscles begins, improbably as it may seem, with that. "Back in the early '90s, most athletes, especially runners and cyclists, were preoccupied with carbohydrates," says John Ivy, the chairman of the department of kinesiology and health education at the University of Texas in Austin and one of the pioneers of research into exercise recovery. This was in the heyday of carbo-loading, when athletes were convinced that the more pasta and bread they ate before a hard workout, the more stored energy they'd have.

But carbo-loading in advance of exercise is not the most efficient way to stock muscles with fuel, physiologists now know, thanks in large part to research conducted by Ivy. When reviewing studies of diabetics, he became intrigued by similarities with his own tests on cyclists: for both groups, insulin in the blood was more effective at carrying energy into the muscles if those muscles had recently been active. "Exercise makes your muscles more responsive to insulin, and this insulin, in turn, increases glycogen muscle uptake," he says. In other words, exercise prompts your muscles to absorb more fuel — glucose, which is stored as glycogen — from the bloodstream. (Carbo-loading can't take advantage of this insulin response because it precedes, rather than follows, a workout.) Your body is actually primed by the exercise to help itself replenish lost fuel.

This improved insulin response, however, lasts only for a brief time after a workout. "You have a window of about 30 to 45 minutes," Ivy says. After that, muscles become resistant to insulin and much less able to absorb glucose. Drinking or eating carbohydrates immediately after a strenuous workout, at a level of at least one gram per kilogram of body weight, is therefore essential to restoring the glycogen you've burned. Wait even a few hours and your ability to replenish that fuel drops by half.

It's also crucial that you take in some protein. Though it poses challenges to strict vegetarians, the latest research shows quite definitively that protein spurs even more of an insulin response than do exercise and carbohydrates alone. "Protein co-ingestion can accelerate muscle glycogen repletion by stimulating endogenous insulin release," says Luc van Loon, an associate professor of human movement sciences at Maastricht University in the Netherlands and the author of several important studies about recovery. Translation: coupling protein with carbohydrates prompts your muscles to store even more glycogen for use during your next workout.

"I'd advise people to have their recovery drink ready and waiting for them before they leave on a run or long bike ride," Ivy says. Ivy himself often drinks low-fat chocolate milk, but any food or drink that includes both carbohydrates and protein — a recovery drink, a smoothie, yogurt — will work.

Then have a real meal within two hours. "You can maintain increased insulin levels and accelerated rates of recovery for about four to six hours if you continue eating," Ivy says. Of course, you can also get by without such diet timing. "But you won't recover as well," Ivy continues. "You probably won't be able to work out as hard on a daily basis." The old guy who chugs his milk and Hershey's syrup will not only pass you — he'll lap you.

Meanwhile, there's the physical damage inside your muscles to consider. Skeletal muscle is a unique kind of tissue, made up of long, thin fibers composed of several different proteins. These proteins interlock like Legos inside fibrous compartments called sarcomeres. Sarcomeres can stretch, but only so far.

During certain kinds of movements, some sarcomeres are pulled past their tolerance. The proteins inside separate, resulting in micro-tears throughout your muscle tissue. After a few hours, this leads to inflammation, swelling, stiffness and pain. (Eccentric muscle contractions, which lengthen muscles, are the main culprit in delayed-onset muscle soreness. Concentric contractions, in which muscles shorten — the upward motion of a biceps curl, for instance — cause less damage. That's why running downhill makes you more sore the next day than running on flat ground.)

"This soreness is actually a good thing," says Thomas Swensen, a professor of exercise and sports science at Ithaca College in Ithaca, N.Y., and a leading researcher into exercise recovery. "You want to stress the muscles. They will adapt positively." The muscles will rebuild themselves, becoming stronger and more pliable. "That's the whole point of hard training," he says. "But it's only effective if you recover fully."

Which is another reason it's important to up your protein intake after a workout; that same protein will also help speed muscle repair. "Exercise stimulates muscle protein synthesis and protein breakdown," van Loon says. "However, without protein or amino acid ingestion, the net balance between protein synthesis and breakdown will remain negative" — i.e., your workouts, in the long run, may do your muscles more harm than good. But eat enough protein immediately after exercising and your muscles will repair themselves fully and become stronger.

Other postworkout recovery strategies, including many that athletes swear by, have far less scientific backing. Take massage. A 2000 study of British boxers showed that postworkout massage made the athletes only feel as if they were recovering quickly; they did not perform any better than those not massaged. Swensen's own 2003 study of massage and recovery produced similar results as the British research.

These studies, however, like many others that have examined massage and exercise, were small and short-term. "It's possible that if you followed athletes over the course of several months," Swensen says, "you might see some benefits from massage. Those studies haven't been done."

Similar ambiguity clouds the use of ibuprofen after exercise. Although advertised as an anti-inflammatory, ibuprofen doesn't always work as expected. A 2006 study of the drug's use among ultra-marathoners found that it did not lessen muscle damage or soreness or reduce inflammation. And although most users do not experience side effects, ibuprofen has been associated with kidney damage and gastrointestinal bleeding.

Finally, there are ice and heat. Many elite athletes swear by a limb-numbing ice bath, and others prefer a soak in a hot tub — although little scientific evidence supports either remedy. Ice will effectively block the swelling associated with a serious injury, such as a sprain, but has not been proven to speed the healing of muscle tissue stressed by a workout. In a study published last year in the British Journal of Sports Medicine, people treated with ice after strenuous exercise later reported more pain upon standing than people immersed in tepid water. The study's authors bluntly concluded that their research "challenges the wide use of [icing] as a recovery strategy by athletes." Similarly, a study published in March in the European Journal of Applied Physiology found that, when it came to muscle recovery, a hot bath was little better than merely sitting quietly for a while.

So where does that leave you, the athlete who has just worked out so diligently? Mixing a smoothie or glass of chocolate milk, the one recovery strategy that satisfies both your inner physiologist and inner child. .

Exercise

Exercise for life.

Before you start an exercise program

If you have decided to start an exercise program, you are already on your way to a healthier heart and a fitter body. The first step you should take is to see your doctor, especially if you have any of the health risks listed below:

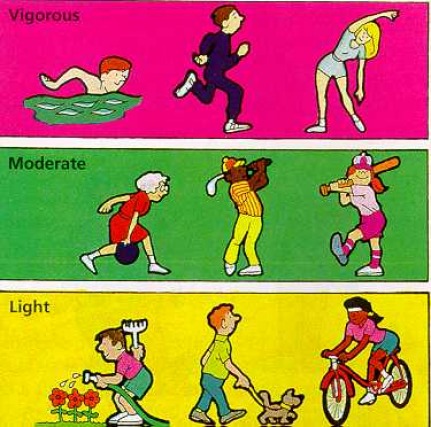

There are 3 categories of exercises: cardiovascular, strength-building, and flexibility.

Cardiovascular exercise is also known as aerobic exercise. Aerobic exercise uses your large muscles and can be continued for long periods. For example, walking, jogging, swimming, and cycling are aerobic activities. These types of exercises drive your body to use oxygen more efficiently and deliver maximum benefits to your heart, lungs, and circulatory system.

Strength-building and flexibility exercises are known as anaerobic exercise. Anaerobic exercise does not have cardiovascular benefits, but it makes your muscles and bones stronger. Strength-building exercises require short, intense effort. Flexibility exercises, which are also anaerobic, tone your muscles through stretching and can prevent muscle and joint problems later in life.

A well-balanced exercise program should include some type of exercise from each category.

Cardiovascular Exercise

A simple definition of cardiovascular exercise is any exercise that raises your heart rate to a level where you can still talk, but you start to sweat a little.

At least 20 minutes of cardiovascular exercise 3 or 4 days a week should be enough to maintain a good fitness level. Any movement is good, even house or yard work. But if your goal is to lose weight, you will need to do some form of cardiovascular exercise for 4 or more days a week for 30 to 45 minutes or longer.

The ideal cardiovascular exercise program starts with a 5- to 10-minute warm-up, which includes gentle movements that will slightly increase your heart rate.

Then, slowly move into 20 or more minutes of a cardiovascular exercise of your choice, such as aerobics, jogging on a treadmill, or walking, to reach what is called your target heart rate. (The chart below can help you find your target heart rate zone.) Your target heart rate is a guideline that can help you measure your fitness level before the start of your program and help you keep track of your progress after you begin an exercise program. Target heart rate also lets you know how hard you are exercising. If you are beginning an exercise program, you should aim for the low end of your target heart rate zone. If you exercise regularly, you may want to work out at the high end of the zone.

To stay within your target heart rate zone, you will need to take your pulse every so often as you exercise. You can find your pulse in 2 places: at the base of your thumb on either hand (called the radial pulse), or at the side of your neck (called the carotid pulse). Put your first 2 fingers over your pulse and count the number of beats within a 10-second period. Multiply this number by 6, and you will have the number of heartbeats in a minute. For example, if you counted your pulse to be 20 during the 10-second pulse count, your heart rate would be 120 beats per minute.

Note: If you are taking certain medicines, like beta blockers, you may not be able to reach your target heart rate. Remember, always have your doctor's approval before beginning any exercise program.

You never want to begin exercising by immediately reaching your target heart rate, because your muscles and circulatory system need to warm up slowly. Intensify your activity slowly during exercise until you reach your target heart rate. There is no need to exceed your target heart rate during exercise.

End your exercise program with a 5- to 10-minute cool down, which will help to lower your heart rate and prevent your muscles from tightening up.

Strength-Building Exercise

People who lift weights or who use any type of equipment that requires weights are doing strength-building exercise. Strength-building exercise makes your muscles and bones stronger and increases your metabolism. Strength exercises also make your muscles larger. Your muscles use calories for energy even when your body is at rest. So, by increasing your muscle mass, you are burning more calories all of the time. If you strength train regularly, you will find that your body looks leaner and you will lose fat.

Strength-building exercises should be performed 2 to 3 times a week for best results. Always warm up your muscles for 5 to 10 minutes before you begin lifting any type of weight or before performing any resistance exercises.

Find a weight that you can comfortably lift for between 8 and 12 repetitions (reps). Reps are the number of times the exercise is performed. When you can easily do 12 to 15 reps of an exercise, it is time to increase the amount of weight you are lifting.

You should choose exercises that work your legs, arms, chest, back, and stomach. Make sure that each movement is performed in a slow, controlled way. Do not jerk the weights or use too much force.

Also, do not hold your breath during the movements. Remember to breathe out as you lift the weight and breathe in as you lower the weight.

Flexibility Exercises

Flexibility exercises are the most neglected part of a fitness program. Having flexibility can improve your posture, reduce your risk of injury, give you more freedom of movement, and release muscle tension and soreness.

Before you start the stretching phase of your program, always do 5 to 10 minutes of warm-up to loosen your muscles. Stretching cold muscles can lead to injury. Some examples of a warm-up are walking around, marching in place, slowly riding an exercise bike, or lightly jogging. If stretching is part of a longer program that includes a cardiovascular workout, always stretch after the cool-down section of your program. You want to make sure that your heart rate has slowed before you begin the stretching phase.

You should try to do stretching exercises for each muscle group. Each stretch should be done slowly and held for at least 10 to 30 seconds.

Do not bounce while you stretch, because bouncing can injure your muscles. Also, do not over stretch a muscle, because it can cause strain or even a tear. Try not to hold your breath while you stretch. Instead, take long, deep breaths throughout your stretching program.

Choosing the right program

Whether you decide to join a health club or to exercise on your own, you will make exercise a regular part of your life if you like doing it. So try to find one or more activities that you like to do or that give you satisfaction. Remember that exercise does not have to feel like a strenuous workout. Your body benefits from any type of movement. So if running or weight lifting are not for you, think about an activity like tai chi or yoga.

If you decide to join a group exercise program like an aerobics class or water-fitness class, here are some tips for choosing a program:

Preventing exercise injuries

One of the most important parts of an exercise program is the warm-up, but most people do not take the time to warm up properly.

A warm up increases your body temperature and makes your muscles loose and ready to exercise. Marching in place, walking for a few minutes, doing some jumping jacks, or jogging in place are all ways to get the blood flowing to the muscles and to prepare them for exercise.

These same exercises can and should be done to cool down after you exercise.

Buying good shoes before you begin an exercise program is one of the most important ways to make sure that you do not get hurt. Your shoes not only protect your feet but also give you a cushion for the weight of your whole body. That is why it is so important that your shoes fit properly.

You should go shoe shopping at the end of the day, when your foot is at its largest size. When you try on a shoe, there should be one-half inch between the end of your toe and the end of the shoe, and your foot should not slip or slide around inside.

Your shoes should feel good when you buy them, and they should not need a "breaking-in" period. If you are exercising regularly, you will most likely need to buy new shoes about every 3 to 6 months. Shoes that are used regularly lose the ability to absorb your weight during exercise and may cause injury to your knees and ankles.

If you are new to an exercise program, and you are exercising at a health club or fitness facility, ask for help before you try something new. The staff should be able to show you how to work any exercise equipment that you do not know how to use. Asking for help will stop you from lifting too much weight or from using the wrong posture when you use the machine. This, in turn, leads to fewer injuries.

Finally, use your good judgment and stay within your exercise limits. Light exercise performed regularly is always better than one gut-wrenching workout session a week. Your body will tell you if you are pushing it too hard. Pain, dizziness, fainting, a cold sweat, or pale skin are signs to stop. Even professional athletes and coaches will tell you that physical fitness is gained a little at a time.

Remember that exercise is not limited to working out in a health club or jogging around a track. Pushing a lawn mower, putting up storm windows, and vacuuming a rug are all forms of exercise, although they are not cardiovascular exercise. If you do not have a job that requires physical activity, taking the stairs instead of the elevator, parking farther away from your office, or taking a brief walk at lunch are all ways to find fitness during your day.

Exercise...Exercise....Exercise

By Jane E. Brody : NY Times Article : December 19, 2006

An apology to all baby boomers and beyond: I’m afraid that in our efforts to get everyone to become physically active, we’ve sold you a bill of goods. A 30-minute walk on most days is just not enough. There is much more to becoming — and staying — physically fit as you age than engaging in regular aerobic activity. (Of course, the same applies to those younger than 60.)

In addition to activities like walking, jogging, cycling and swimming that promote endurance, cardiovascular health and weight control, there is a dire need for exercises that improve posture and increase strength, flexibility and balance. These exercises can greatly reduce the risk of injuries from sports and endurance activities, the demands of daily life, falls and other accidents.

Musculoskeletal injuries are now the No. 1 one reason for seeking medical care in the United States. And falls, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported last month, have become the leading cause of injury deaths for men and women 65 and older.

Unless you do something to slow the deterioration in muscle, bone strength and agility that naturally accompanies aging, you will become a prime candidate for what Dr. Nicholas A. DiNubile, an orthopedic surgeon at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, calls “boomeritis.”

“By their 40th birthday, people often have vulnerabilities — weak links — and as the first generation that is trying to stay active in droves, baby boomers are pushing their frames to the breakpoint,” Dr. DiNubile said in introducing a November press event in New York sponsored by the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons and the National Athletic Trainers’ Association.

“Baby boomers are falling apart — developing tendinitis, bursitis, arthritis and ‘fix-me-itis,’ the idea that modern medicine can fix anything,” he said. “It’s much better to prevent things than to have to try to fix them.”

Dr. DiNubile pointed out that evolution had not kept up with the doubling of the human life span in the last 100 years. To counter the inevitable declines with age, we have to provide our bodies with an extended warranty.

Assess Your Fitness

In their recently published book, “Age-Defying Fitness” (Peachtree Publishers), two prominent physical therapists, Marilyn Moffat of New York University and Carole B. Lewis of Washington, D.C., provide the ingredients to help you make the most of your body for the rest of your life: a quick quiz and a five-part test to assess the status of your posture, strength, balance, flexibility and endurance, followed by five chapters with step-by-step instructions on how to safely improve the areas in which you are lacking.

The therapists describe what happens to these “five domains of fitness” as you age. Posture begins changing as early as the teenage years, the result of activities like prolonged sitting, carrying a heavy purse or briefcase, or working at a computer.

Strength declines as muscle fibers decrease in size and number and as the supply of nerve stimulation and energy to the muscles diminishes. Balance deteriorates as muscles tighten and weaken and joints lose their full range of motion.

Flexibility declines because connective tissue throughout the body becomes less elastic. And endurance falls off because of reduced flexibility, weakened muscles, and stiffer lungs and blood vessels.

Still not convinced you need to work on your fitness? See how you do on the therapists’ quiz:

“The antidote to aging is activity,” the therapists wrote. “Inactivity magnifies age-related changes, but action maintains and increases your abilities in all five domains.”

No Time to Waste

Dr. Vonda J. Wright, a sports medicine specialist at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, said at the New York meeting that “boomers are 59, and we must intervene now to head off what happens to those who age in a sedentary way.”

Injury and arthritis are the main reasons people stop exercising, she said. She urged those in need of a joint replacement not to postpone the surgery, which she likened to repairing a pothole.

Marjorie J. Albohm, a certified athletic trainer affiliated with OrthoIndy and the Indiana Orthopedic Hospital in Indianapolis, cautioned against “cookbook recipes” for exercise. “The key to a good workout is customization,” based on a professional assessment of flexibility, cardiovascular endurance, strength and balance, she said. “The goal is to minimize symptoms and prevent new injuries,” Ms. Albohm said, and she urged people to listen to their bodies to avoid making things worse.

Ms. Albohm emphasized flexibility, saying it is “not optional” as you age. “To prevent stiffness and maintain joint mobility you should stretch daily for 15 to 20 minutes,” she said “using slow, controlled movements, before or after your exercise program.”

For cardiovascular endurance, she recommended alternating between weight-bearing (walking, jogging) and non-weight-bearing (swimming, cycling) aerobic activities three days a week for 30 to 45 minutes each time.

Muscle strength, Ms. Albohm noted, can be increased at any age, even in one’s 90s, to protect against falls, maintain mobility, prevent new injuries and empower individuals. Especially important is strengthening the muscles in the front and sides of the thighs, which help support the knees, and strengthening core muscles of the trunk (back, buttocks and abdomen) to protect the spine and support the entire body.

Finally, we need to worry about our bones. At least 1.5 million “fragility fractures” occur annually in the United States. These are breaks that result when someone falls from a standing height or less, trips over the cat or lifts something heavy, and they affect men as well as women, Dr. Laura Tosi, an orthopedic surgeon at Children’s National Medical Center in Washington, D.C., said at the New York event.

“A history of a fragility fracture is far more predictive of future fractures than a bone density test,” Dr. Tosi said, adding that a major cause is a shortage of vitamin D, which lets calcium into bones.

“The current standard for vitamin D is not adequate,” she said, and predicted it would soon be raised to perhaps 1,000 International Units a day. Vitamin supplements are crucial, because adequate amounts of vitamin D cannot be absorbed through diet and sunshine alone.

Personal Health: You Name It and Exercise Helps It

By Jane E. Brody

NY Times Article : April 28, 2008

Randi considers the Y.M.C.A. her lifeline, especially the pool. Randi weighs more than 300 pounds and has borderline diabetes, but she controls her blood sugar and keeps her bright outlook on life by swimming every day for about 45 minutes.

Randi overcame any self-consciousness about her weight for the sake of her health, and those who swim with her and share the open locker room are proud of her. If only the millions of others beset with chronic health problems recognized the inestimable value to their physical and emotional well-being of regular physical exercise.

“The single thing that comes close to a magic bullet, in terms of its strong and universal benefits, is exercise,” Frank Hu, epidemiologist at the Harvard School of Public Health, said in the Harvard Magazine.

I have written often about the protective roles of exercise. It can lower the risk of heart attack, stroke, hypertension, diabetes, obesity, depression, dementia, osteoporosis, gallstones, diverticulitis, falls, erectile dysfunction, peripheral vascular disease and 12 kinds of cancer.

But what if you already have one of these conditions? Or an ailment like rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, congestive heart failure or osteoarthritis? How can you exercise if you’re always tired or in pain or have trouble breathing? Can exercise really help?

You bet it can. Marilyn Moffat, a professor of physical therapy at New York University and co-author with Carole B. Lewis of “Age-Defying Fitness” (Peachtree, 2006), conducts workshops for physical therapists around the country and abroad, demonstrating how people with chronic health problems can improve their health and quality of life by learning how to exercise safely.

Up and Moving

“The data show that regular moderate exercise increases your ability to battle the effects of disease,” Dr. Moffat said in an interview. “It has a positive effect on both physical and mental well-being. The goal is to do as much physical activity as your body lets you do, and rest when you need to rest.”

In years past, doctors were afraid to let heart patients exercise. When my father had a heart attack in 1968, he was kept sedentary for six weeks. Now, heart attack patients are in bed barely half a day before they are up and moving, Dr. Moffat said.

The core of cardiac rehab is a progressive exercise program to increase the ability of the heart to pump oxygen- and nutrient-rich blood more effectively throughout the body. The outcome is better endurance, greater ability to enjoy life and decreased mortality.

The same goes for patients with congestive heart failure. “Heart failure patients as old as 91 can increase their oxygen consumption significantly,” Dr. Moffat said.

Aerobic exercise lowers blood pressure in people with hypertension, and it improves peripheral circulation in people who develop cramping leg pains when they walk — a condition called intermittent claudication. The treatment for it, in fact, is to walk a little farther each day.

In people who have had transient ischemic attacks, or ministrokes, “gradually increasing exercise improves blood flow to the brain and may diminish the risk of a full-blown stroke,” Dr. Moffat said. And aerobic and strength exercises have been shown to improve endurance, walking speed and the ability to perform tasks of daily living up to six years after a stroke.

As Randi knows, moderate exercise cuts the risk of developing diabetes. And for those with diabetes, exercise improves glucose tolerance — less medication is needed to control blood sugar — and reduces the risk of life-threatening complications.

Perhaps the most immediate benefits are reaped by people with joint and neuromuscular disorders. Without exercise, those at risk of osteoarthritis become crippled by stiff, deteriorated joints. But exercise that increases strength and aerobic capacity can reduce pain, depression and anxiety and improve function, balance and quality of life.

Likewise for people with rheumatoid arthritis. “The less they do, the worse things get,” Dr. Moffat said. “The more their joints move, the better.”

Exercise that builds gradually and protects inflamed joints can diminish pain, fatigue, morning stiffness, depression and anxiety, she said, and improve strength, walking speed and activity.

Exercise is crucial to improving function of total hip or knee replacements. But “most patients with knee replacements don’t get intensive enough activity,” Dr. Moffat said.

Water exercises are particularly helpful for people with multiple sclerosis, who must avoid overheating. And for those with Parkinson’s, resistance training and aerobic exercise can increase their ability to function independently and improve their balance, stride length, walking speed and mood.

Resistance training, along with aerobic exercise, is especially helpful for people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; it helps counter the loss of muscle mass and strength from lack of oxygen.

In the February/March issue of ACE Certified News, Natalie Digate Muth, a registered dietitian and personal trainer, emphasized the value of a good workout for people suffering from depression. Mastering a new skill increases their sense of worth, social contact improves mood, and the endorphins released during exercise improve well-being.

“Exercise is an important adjunct to pharmacological therapy, and it does not matter how severe the depression — exercise works equally well for people with moderate or severe depression,” wrote Ms. Muth, who is pursuing a medical degree at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

Feel-Good Hormones

Healthy people may have difficulty appreciating the burdens faced by those with chronic ailments, Dr. Nancey Trevanian Tsai noted in the same issue of ACE Certified News. “Oftentimes, disease-ridden statements — like ‘I’m a diabetic’ — become barricades that keep clients from seeing themselves getting better,” she said, and many feel “enslaved by their diseases and treatments.”

But the feel-good hormones released through exercise can help sustain activity.

“With regular exercise, the body seeks to continue staying active,” wrote Dr. Tsai, an assistant professor of neurosciences at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. She recommended an exercise program tailored to the person’s current abilities, daily needs, medication schedule, side effects and response to treatment.

She urged trainers who work with people with chronic ailments to start slowly with easily achievable goals, build gradually on each accomplishment and focus on functional gains. Over time, a sense of accomplishment, better sleep, less pain and enhanced satisfaction with life can become further reasons to pursue physical activity.

“Even if exercise is tough to schedule,” Dr. Moffat said, “you feel so much better, it’s crazy not to do it.”

Rest and Motion. The value of interval training

By Peter Jaret : NY Times article : May 3, 2007

Some gym goers are tortoises. They prefer to take their sweet time, leisurely pedaling or ambling along on a treadmill. Others are hares, impatiently racing through miles at high intensity.

Each approach offers similar health benefits: lower risk of heart disease, protection against Type 2 diabetes, and weight loss.

But new findings suggest that for at least one workout a week it pays to be both tortoise and hare — alternating short bursts of high-intensity exercise with easy-does-it recovery.

Weight watchers, prediabetics and those who simply want to increase their fitness all stand to gain.

This alternating fast-slow technique, called interval training, is hardly new. For decades, serious athletes have used it to improve performance.

But new evidence suggests that a workout with steep peaks and valleys can dramatically improve cardiovascular fitness and raise the body’s potential to burn fat.

Best of all, the benefits become evident in a matter of weeks.

“There’s definitely renewed interest in interval training,” said Ed Coyle, the director of the human performance laboratory at the University of Texas at Austin.

A 2005 study published in the Journal of Applied Physiology found that after just two weeks of interval training, six of the eight college-age men and women doubled their endurance, or the amount of time they could ride a bicycle at moderate intensity before exhaustion.

Eight volunteers in a control group, who did not do any interval training, showed no improvement in endurance.

Researchers at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, had the exercisers sprint for 30 seconds, then either stop or pedal gently for four minutes.

Such a stark improvement in endurance after 15 minutes of intense cycling spread over two weeks was all the more surprising because the volunteers were already reasonably fit. They jogged, biked or did aerobic exercise two to three times a week.

Doing bursts of hard exercise not only improves cardiovascular fitness but also the body’s ability to burn fat, even during low- or moderate-intensity workouts, according to a study published this month, also in the Journal of Applied Physiology. Eight women in their early 20s cycled for 10 sets of four minutes of hard riding, followed by two minutes of rest. Over two weeks, they completed seven interval workouts.

After interval training, the amount of fat burned in an hour of continuous moderate cycling increased by 36 percent, said Jason L. Talanian, the lead author of the study and an exercise scientist at the University of Guelph in Ontario. Cardiovascular fitness — the ability of the heart and lungs to supply oxygen to working muscles — improved by 13 percent.

It didn’t matter how fit the subjects were before. Borderline sedentary subjects and the college athletes had similar increases in fitness and fat burning. “Even when interval training was added on top of other exercise they were doing, they still saw a significant improvement,” Mr. Talanian said.

That said, this was a small study that lacked a control group, so more research would be needed to confirm that interval training was responsible.

Interval training isn’t for everyone. “Pushing your heart rate up very high with intensive interval training can put a strain on the cardiovascular system, provoking a heart attack or stroke in people at risk,” said Walter R. Thompson, professor of exercise science at Georgia State University in Atlanta.

For anyone with heart disease or high blood pressure — or who has joint problems such as arthritis or is older than 60 — experts say to consult a doctor before starting interval training.

Still, anyone in good health might consider doing interval training once or twice a week. Joggers can alternate walking and sprints. Swimmers can complete a couple of fast laps, then four more slowly.

There is no single accepted formula for the ratio between hard work and a moderate pace or resting. In fact, many coaches recommend varying the duration of activity and rest.

But some guidelines apply. The high-intensity phase should be long and strenuous enough that a person is out of breath — typically one to four minutes of exercise at 80 to 85 percent of their maximum heart rate. Recovery periods should not last long enough for their pulse to return to its resting rate.

Also people should remember to adequately warm up before the first interval. Coaches advise that, ideally, people should not do interval work on consecutive days. More than 24 hours between such taxing sessions will allow the body to recover and help them avoid burnout.

What is so special about interval training? One advantage is that it allows exercisers to spend more time doing high-intensity activity than they could in a single sustained effort. “The rest period in interval training gives the body time to remove some of the waste products of working muscles,” said Barry A. Franklin, the director of the cardiac rehabilitation and exercise laboratories at the William Beaumont Hospital in Royal Oak, Mich.

To go hard, the body must use new muscle fibers. Once these recent recruits are trained, they are available to burn fuel even during easy-does-it workouts. “Any form of exercise that recruits new muscle fibers is going to enhance the body’s ability to metabolize carbohydrates and fat,” Dr. Coyle said.

Interval training also stimulates change in mitochondria, where fuel is converted to energy, causing them to burn fat first — even during low- and moderate-intensity workouts, Mr. Talanian said.

Improved fat burning means endurance athletes can go further before tapping into carbohydrate stores. It is also welcome news to anyone trying to lose weight or avoid gaining it.

Unfortunately, many people aren’t active enough to keep muscles healthy. At the sedentary extreme, one result can be what Dr. Coyle calls “metabolic stalling” — carbohydrates in the form of blood glucose and fat particles in the form of triglycerides sit in the blood. That, he suspects, could be a contributing factor to metabolic syndrome, the combination of obesity, insulin resistance, high cholesterol and elevated triglycerides that increases the risk of heart disease and diabetes.

The Benefits of lifting weights

By Judy Foreman : Boston Globe Article : January 21, 2008

I'm an exercise junkie - and proud of it. I swim, I run, I bike.

But, like many other people, I'm a disaster when it comes to lifting weights, also called strength, or resistance, training. The closest I come is lifting a few tiny dumbbells at home in front of the TV. And that's only when the Red Sox are on.

This is about to change, and not just because of lingering New Year's resolutions.

A growing body of evidence shows that strength training not only provides many benefits that aerobic workouts alone cannot, but also offers some of the same health benefits as aerobic conditioning.

It's long been known that weight lifting becomes more important as you get older to prevent injury and preserve the strength to do normal things like climbing stairs, hauling groceries, and chasing grandchildren.

What's comparatively new is that it does much more than that, potentially reducing the risk of developing heart disease, relieving neck pain, improving balance, and making it easier to battle the bulge - though it needs to be done properly to avoid injury.

The evidence for the value of strength training has grown so much that last year, the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association issued new recommendations for healthy adults 65 and older that stressed the importance of weight lifting.

The groups now recommend that all older Americans do eight to 10 repetitions for each of the major muscle groups (biceps, quadriceps, hamstrings, etc.). Resistance exercises should be done on two or more nonconsecutive days of the week.

The idea is to lift a weight that's heavy enough to work each muscle group until it is fatigued, so the amount you lift will increase as your strength grows. Weight-bearing exercise, like walking or running, does not count as weight lifting - that means you really have to lift weights or work out on a resistance machine.

One of the biggest benefits of strength training is that it dramatically increases muscle mass, which aerobic exercise does not, noted William J. Evans, director of the Nutrition, Metabolism, and Exercise Laboratory at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences. More muscle mass is good not just because it makes you stronger but because it increases basal metabolic rate - muscle cells even at rest burn more calories than fat cells.

Moreover, while aerobic exercise can significantly, although temporarily, increase blood pressure, a potential concern for some heart patients, resistance training does so only minimally, Evans said. Weight training also gets results fast - it only takes resistance training twice a week for a few weeks to begin to see a significant effect, compared with three days a week with aerobics.

Indeed, the more researchers probe the benefits of weight training for specific conditions, the stronger the case they can make, said Miriam Nelson, director of the John Hancock Center for Physical Activity and Nutrition at Tufts University.

Although studies have not yet proven that strength training lowers the risk of osteoporosis, Nelson said, they do show it lowers the risk of fractures by improving balance, bone density, and muscle mass. Weight training is also good for people with arthritis, she said, because stronger muscles can take the pressure off inflamed joints.

Weight training has been shown to have other benefits, too.

Research by Steven N. Blair, an exercise scientist at the University of South Carolina, suggests that people with greater muscle strength may be somewhat less likely to develop metabolic syndrome, a cluster of factors that raise the risk of heart disease and diabetes, such as increased waist size, high fasting blood sugar, high triglycerides, low HDL or "good" cholesterol, and high blood pressure. More studies are needed to confirm this association.

For older people with physical disabilities, 66 trials reviewed by Cochrane Collaboration, an international nonprofit group that evaluates health treatments, increasing strength and, to a lesser extent, function. A different 2007 Cochrane review of 34 studies showed that exercises, including strength training, can improve balance in women age 75 and older. Yet another 2007 Cochrane review of 34 studies on fibromyalgia (musculoskeletal pain) showed strength training may improve physical capacity.

And a Danish study just published last week showed that strength training can diminish the chronic neck pain of at computers.

I could go on. But I'm convinced. Weight training may not be as much fun as a run in the park. But I need it. I'm guessing you do, too.

The value of resistance training and the heart

While conventional wisdom once held that people with heart disease should not pump iron, a new scientific statement from the American Heart Association says some resistance training can be good for them.

"Just like we once learned that people with heart disease benefited from aerobic exercise, we are now learning that guided, moderate weight training also has significant benefits," said Mark Williams, professor of medicine at Creighton University School of Medicine in Omaha, Nebraska.

Weight training is seen as a complement to aerobic exercise, not a replacement, he said. But it provides everyday benefits.

"It helps people better perform tasks of daily living -- like lifting sacks of groceries," Williams said in a statement.

Resistance training is not recommended for people with certain conditions such as unstable heart disease, uncontrolled high blood pressure or heart rhythm disorders, infections in and around the heart, and some other serious problems.

The statement's recommendations for an initial weight-lifting program says resistance training should be performed:

And they are easier to stick to.

"For people with cardiovascular disease, the level of resistance should be reduced and number of repetitions increased, resulting in a lower relative effort and reducing the likelihood of breath-holding and straining," the statement reads.

The heart benefits of weight training include increased muscle mass which can help in weight control.

"Patients who have had cardiac events are often apprehensive about returning to this type of activity, or doing things in their daily lives that might be perceived as strenuous ... Now we know that they can return to the active things they enjoy doing," Williams said.

By recruiting new muscle fibers and increasing the body’s ability to use fuel, interval training could potentially lower the risk of metabolic syndrome.

Interval training does amount to hard work, but the sessions can be short. Best of all, a workout that combines tortoise and hare leaves little time for boredom.

Work Out Now, Ache Later: How Your Muscles Pay You Back

By Vicky Lowry : New York Times. November 16, 2004

Active people know the feeling all too well: a stiff and achy sensation in the muscles that sneaks up on the body 24 hours or more after, say, a hard run, a challenging weight lifting session or the first day back on the ski slopes.

Sports scientists call it delayed onset of muscle soreness. Athletes call it a nuisance because even simple movements like walking down stairs can be an ordeal. If the soreness is severe enough, it can hamper the next workout or even ruin a ski vacation.

Because of the delay, some people may not even realize that the aches and pains were caused by an activity - gardening, for example, or hammering nails - engaged in days before.

"I've had patients call me up who think they have a virus," said Dr. Gary Wadler, a professor at the New York University School of Medicine and a specialist in sports medicine.

The culprit for delayed muscle soreness is not, as some people used to think, the buildup of lactic acid, a byproduct of exercise that dissipates from the muscle tissues within an hour. That kind of soreness is considered acute. As soon as someone stops exercising, or shortly afterward, the burn goes away.

"It's not the key bad guy," said Dr. Michael Saunders, director of the Human Performance Laboratory at James Madison University in Harrisonburg, Va.

No one knows for sure exactly what does cause muscle soreness. But many scientists now think that the delayed pain is caused by microscopic tears in the muscles when a certain exercise or activity is new or novel. These tiny tears eventually produce inflammation, and corresponding pain, 24 to 36 hours later.

"White blood cells start to repair the damaged muscle after about 12 to 24 hours and they release a number of chemicals which are likely to be involved in the generation of local muscle pain," said Dr. Mark Tarnopolsky, a specialist in neuromuscular disorders at the McMaster University Medical Center in Hamilton, Ontario. "You see damage at the microscopic level immediately after exercise, yet the soreness is usually delayed for about 24 hours and peaks at 48 hours."

The good news is that as these little tears repair themselves, they prepare the muscles to handle the same type of exercise better the next time.

"The muscle gets more resilient, meaning the next time you do that same exercise you won't get damaged as much," said Dr. Priscilla Clarkson, a professor of exercise science at the University of Massachusetts and a leading researcher on muscle soreness. "That doesn't mean you are stronger, or mean you can lift more weight. It just means your muscle fibers are likely stronger so they won't tear as easily. Over time they'll build up and become a stronger fiber to lift more weight."

Performing certain exercises can almost guarantee delayed soreness: running, hiking or skiing downhill, for example, and lowering weights - what weight lifters refer to as "negatives." In these downhill or downward motions, called eccentric muscle actions, the muscle fibers have to lengthen and then contract, "like putting on the brakes," Dr. Clarkson explained. "It's that lengthening-contraction that puts the most strain on the fiber and does the most damage."

Of the 600 or so muscles in the human body, about 400 of them are skeletal. The largest of these are the muscles most susceptible to delayed soreness, Dr. Wadler said.

Severe muscle pain that lasts for many days can be a sign of rhabdomyolysis, a disorder that occurs when too much of the muscle protein myoglobin leaks from the muscle cells into the bloodstream, possibly damaging the kidneys.

Dark urine, indicating the presence of myoglobin, can be a symptom of rhabdomyolysis, which in very rare cases can lead to renal failure.

Running marathons and participating in other endurance events can cause rhabdomyolysis, said Dr. William O. Roberts, president of the American College of Sports Medicine. Other risk factors include being unfit or dehydrated and exercising in high temperatures.

"It's one of the reasons why you want to stay well hydrated if you are going to work your muscles hard," Dr. Roberts said. "Drink enough so that you have good urine output to clear these waste products." In most cases, though, delayed muscle soreness is not serious, and the soreness fades after a day or two of rest. Weight lifters typically work out the lower body one day and the upper body the next to give fatigued muscles a chance to recover. And conditioned athletes, like cyclists and runners, often alternate between easy and hard days of exercise. "Stress-adapt, stress-adapt so you can handle more and more exercise," said Dr. Tarnopolsky. "That's what an athlete strives for."

The results for other strategies for avoiding or recovering more quickly from muscle soreness are mixed. Many active people reach for nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs like Advil or Aleve. While some data suggest that the drugs may work to prevent soreness or alleviate it once it sets in, the degree of reduction in soreness is small, Dr. Clarkson said.

Rarely, doctors prescribe the painkillers known as COX-2 inhibitors for short-term muscle soreness. But the drugs, which include Celebrex and Bextra, are more commonly used to treat arthritis.

And all cox-2 inhibitors are under increased scrutiny, after Vioxx was pulled from the market in September. Merck withdrew it after studies found it increased the risk of heart attacks and stroke.

Stretching does not prevent muscle soreness, researchers have found, and massage does little to improve recovery after eccentric muscle use, according to a study published in September in The American Journal of Sports Medicine. In the study, researchers in Stockholm found that after participants performed leg exercises to exhaustion, massage treatment did not affect the level or duration of pain, loss of strength or muscle function.

Consuming protein, however, may help. In a report published in the July issue of the journal Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, scientists found that trained cyclists who consumed a carbohydrate and protein beverage during and immediately after a ride, were able to ride 29 percent longer during the first ride, and 40 percent longer in a second session than those consuming carbohydrates alone.

"Our findings suggest that the protein-carbohydrate mix enhanced muscle performance and recovery in the later rides," said Dr. Saunders of James Madison, the study's lead author.

But further research is necessary. The results of the study may have been influenced by a higher caloric content in the carbohydrate-protein beverage.

"There is some evidence that consuming protein and carbohydrates in the immediate period after exercise may decrease subsequent muscle damage, but that research is in its infancy," said Dr. Tarnopolsky. "What has been fairly well established is that eating food in the postexercise period is better than starving.

"The take-home message is if you are training in the evening don't go to bed on an empty stomach. And if you work out in the morning, eat breakfast afterward or make darn sure to take a snack to work."

A practical tactic is to try to limit muscle soreness before it takes hold. For that, you need to train the body to get used to downhill or downward motions.

"Gradually run or walk down hills more if you are planning to participate in a downhill event, or take an elevator up to the top of a tall building and walk or run down the stairs," Dr. Roberts recommended.

Hikers should consider using adjustable poles, which distribute some of the stress on the legs, transferring it to the upper body, when descending steep grades. "I put hiking poles into the hands of every one of my clients and tell them that if they don't like them I'll carry them," said Nate Goldberg, who routinely guides hikes up 14,000-foot peaks in the Sawatch Mountains of Colorado as director of the Beaver Creek Hiking Center. "Very rarely do I get a set of poles back."

Seasoned athletes, it turns out, are no more immune to delayed onset of muscle soreness than neophyte exercisers. "If I asked Lance Armstrong to run down 10 flights of stairs, he'd be very sore," Dr. Clarkson said. "It's all about sport specificity."

Can Exercise Kill?

The answer: Yes, and probably more often than you think

By Kevin Helliker : Wall Street Journal : October 11, 2004

· In the space of seven months in 2002, three physicians at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore suffered sudden cardiac death while exercising. Two were running, the other working out in the hospital's fitness center. All three had paid close attention to diet and exercised regularly. The oldest was 51.

This unlikely string of deaths brought tremendous local attention to a topic that medicine typically doesn't emphasize -- for good reason. Exercise, after all, prolongs more lives than it cuts short. And in a nation that is largely sedentary, people need no extra excuse not to exercise.

Yet a growing number of physicians believe that publicizing the risks of exercise could potentially save a significant number of lives. Johns Hopkins cardiologist Nancy Strahan, for one, is now advising her middle-aged patients to stay away from jogging until they've undergone an exam to determine their risks.

"Present research reveals that vigorous exercise is responsible for triggering up to 17%" of sudden cardiac deaths in the U.S., says a recent article in the American Medical Athletic Association Journal. This means that vigorous exercise is triggering tens of thousands of U.S. deaths a year.

Impact on Immune System

What's more, sudden death isn't the only risk. Evidence is mounting that extreme exercise -- marathons, triathlons and the like -- may be detrimental to the immune system and long-term health. "Exercising to excess can harm our health," cautions Kenneth Cooper, the physician credited with founding the aerobics movement back in the 1960s.

All of this, of course, runs counter to conventional wisdom, which says that exercise is a virtue, and that you can't get too much of a virtue. Indeed, pretty much as soon as a thirtysomething slips on his first pair of running shoes he is challenged by an acquaintance or athletic-store poster to run a marathon. But exercise more accurately may be perceived as a medical therapy, and doctors are generally very cautious about the dosages they prescribe for medical therapies. Nobody would recommend quadrupling the dose of a drug that had proved to be effective.

So, how much is too much? It depends, of course, on the person.

The risk of sudden cardiac death during exercise would be reduced if people -- especially those older than 40 -- underwent various tests before starting a workout program. These tests include: an electrocardiogram, an electrical recording of the heart that can detect various abnormalities; an exercise stress test, during which physicians monitor the cardiovascular system's response during a treadmill workout; and an echocardiogram, an ultrasound scan that can spot a wide range of defects. Whether your insurance will pay for these tests depends on your age, health plan and how strongly your doctor recommends them.

Although these tests aren't guaranteed to find every cardiovascular booby trap that exercise can trip, they can identify a significant percentage of the conditions that cause sudden cardiac death-artery blockages, cardiac arrhythmias, aneurysms and more.

The risk of sudden death during exercise appears to rise as the duration of the workout grows. For instance, the risk of death during a marathon is about one in 50,000 finishers -- significantly higher than during shorter races or inactivity. One reason is that during long-distance runs the body sustains muscle injury, and it can react to this injury as if it were bleeding, by rendering blood more clottable, says Arthur Siegel, a Harvard University professor and chief of internal medicine at McLean Hospital in Belmont, Mass. In people with hidden blockage in their coronary arteries, this thickened blood can result in sudden cardiac death.

But that's not the only danger. Muscular injury can also set off a hormonal response that in turn triggers water intoxication, with acute brain swelling, says Dr. Siegel. This can be deadly for marathon runners who take too seriously the recommendation to drink lots of fluid. In recent years, young and healthy runners have died of hyponatremia -- essentially drinking too much fluid -- in several marathons, including those in Chicago and Boston.

"A half-million Americans a year are going out to run marathons," says Dr. Siegel. "They incur a dose of exercise that is enough to cause muscle injury that could, under certain circumstances, have grave consequences."

Having run 20 marathons himself, Dr. Siegel calls himself an advocate for safe participation. Avoiding hyponatremia is mostly a matter of drinking only when thirsty, and this caution is especially important for slower runners.

As for sudden cardiac death, Dr. Siegel suggests that people at risk for cardiac disease perhaps should be cautious about pushing their heart rates too high. People with high risk factors "ought to be careful about keeping the intensity moderate," says Dr. Siegel. "Exercise at a level where they can be conversational." Should such people run marathons? Dr. Siegel advises: "Do the marathon training but skip the race."

An increasingly popular theory has it that death from extreme exercise may not come until years afterward. This theory first occurred to Dr. Cooper, founder of the Cooper Institute in Dallas, when he noticed what seemed like a higher-than-average rate of cancer and other disease among the fitness fanatics he knew.

'More Harm Than Good'?

Having now studied the matter for more than 20 years, he has concluded that especially long and intense bouts of exercise may be damaging to the immune system. It is only a theory, but it is at least partly based on medical studies such as one showing that marathoners suffer a high rate of cold and flu just before and after races.

"If you're exercising more than five hours a week [at a high intensity], there's a possibility that you may be doing more harm than good," Dr. Cooper says.

Nobody should feel compelled for health reasons to run marathons, do triathlons or otherwise aspire to become a fitness fanatic, says Dr. Cooper, adding that 30 minutes a day of moderate exercise such as walking is sufficient.