- RETIREMENT ANNOUNCEMENT

- HOME PAGE

- "MYCHART" the new patient portal

- BELMONT MEDICAL ASSOCIATES

- MOUNT AUBURN HOSPITAL

- EMERGENCIES

- PRACTICE PHILOSOPHY

- MY RESUME

- TELEMEDICINE CONSULTATION

- CONTACT ME

- LAB RESULTS

- ePRESCRIPTIONS

- eREFERRALS

- RECORD RELEASE

- MEDICAL SCRIBE

- PHYSICIAN ASSISTANT (PA)

- Medicare Annual Wellness Visit

- Case management/Social work

- Quality Care Measures

- Emergency closing notice

- FEEDBACK

- Talking to your doctor

- Choosing..... and losing a doctor

- INDEX A - Z

- ALLERGIC REACTIONS

- Alternative Medicine

- Alzheimer's Disease

- Bladder Problems

- Blood disorders

- Cancer Concerns

- GENETIC TESTING FOR HEREDITARY CANCER

- Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

- Controversial Concerns

- CPR : Learn and save a life

- CRP : Inflammatory marker

- Diabetes Management

- Dizziness, Vertigo,Tinnitus and Hearing Loss

- EXERCISE

- FEMALE HEALTH

-

GASTROINTESTINAL topics

- Appendicitis

- BRAT diet

- Celiac Disease or Sprue

- Crohn's Disease

- Gastroenterologists for Colon Cancer Screening

- Colonoscopy PREP

- Constipation

- Gluten sensitivity, but not celiac disease

- Heartburn and GERD

- Hemorrhoids and Anal fissure

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- NASH : Non Alcoholic Steato Hepatitis

- FEET PROBLEMS

- HEART RELATED topics

-

INFECTIOUS DISEASES

- Antibiotic Resistance

- Cat bites >

- Clostridia difficile infection - the "antibiotic associated germ"

- CORONA VIRUS

- Dengue Fever and Chikungunya Fever

- Food borne illnesses

- Shingles Vaccine

- Hepatitis B

- Hepatitis C

- Herpes

- Influenza

- Helicobacter pylori - the "ulcer germ"

- HIV Screening

- Lyme and other tick borne diseases

- Measles

- Meningitis

- MRSA (Staph infection)

- Norovirus

- Sexually Transmitted Diseases

- Shingles (Herpes Zoster)

- Sinusitis

- West Nile Virus

- Whooping Cough (Pertussis)

- Zika virus and pregnancy

- INSURANCE related topics

- KIDNEY STONES

- LEG CRAMPS

- LIBRARY for patients

- LIFE DECISIONS

- MALE HEALTH

- Medication/Drug side effects

- MEDICAL MARIJUANA

- MENTAL HEALTH

- Miscellaneous Articles

-

NUTRITION - EXERCISE - WEIGHT

- Cholesterol : New guidelines for treatment

- Advice to lower your cholesterol

- Cholesterol : Control

- Cholesterol : Raising your HDL Level

- Exercise

- Food : Making Smart Choices

- Food : Making Poor Choices

- Food : Grape Fruit and Drug Interaction

- Food : Vitamins, Minerals and Supplements

- Omega 3 fatty acids

- Vitamin B12 deficiency

- Vitamin D

- Weight Loss

- ORTHOPEDICS

- PAIN

- PATIENTS' RIGHTS

- SKIN

- SLEEP

- SMOKING

- STROKE

- THYROID

- SUBSTANCE ABUSE

- Travel and Vaccination

- TREMOR

- Warfarin Anticoagulation

- OTHER STUFF FOLLOWS

- Fact or Opinion?

- Hippocratic Oath

- FREE ADVICE.......for what its worth!

- LAUGHTER.....is the best medicine

- Physicians Pet Peeves

- PHOTO ALBUM - its not all work!

- Cape Town, South Africa

- Tribute page

- The 100 Club

- Free Wi-Fi

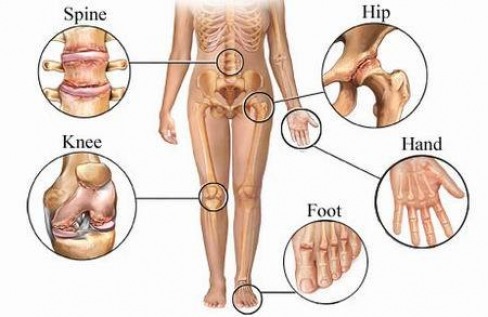

Pain : Arthritis

Osteoarthritis or Degenerative Joint Disease

Caring for Hips and Knees to Avoid Artificial Joints

By Lesley Alderman : NY Times Article : April 23, 2010

Protect your joints now, or pay later.

That’s the message of today’s column, which could be headlined Joint Economics.

If you are one of the more than 400,000 people a year who have already had one or more hips or knees replaced — or someone who already has no choice but to consider joining their ranks — we offer our sympathies or encouragement or even congratulations, depending on how you are faring. But this column is for people who are not yet destined to necessarily become part of those statistics.

Although the human body has an amazing capacity to repair itself, our joints are surprisingly fragile.

When the cartilage that cushions bones wears away, it does not grow back. Thinning cartilage contributes to osteoarthritis, also known as degenerative arthritis, a painful and often debilitating condition.

Over time, arthritic joints can become so sore and inflamed that they need to be replaced with mechanical substitutes. A result: more pain, at least in the short term, and big medical bills.

Fortunately, you can act to protect your joints now, to reduce your chances of needing to replace them later.

And protect you should. The cost for a new hip or knee — the joints most commonly replaced — is $30,000 to $40,000. If you have insurance, your total out-of-pocket costs will be much less, but may still be $3,000 to $4,000. And don’t forget to factor in all those days of work you will miss before you get your new prosthetic.

Creaky joints are a growing national problem. The population is getting older, more people are overweight, and an increasing number of children and young adults are playing serious sports and getting seriously injured — all factors that contribute to osteoarthritis.

“Arthritis used to show up in people during their late 40s and 50s, now we’re seeing it earlier, like in the 30s and 40s,” said Dr. Patience White, a rheumatologist and the chief public health officer at the Arthritis Foundation.

The total national bill for hip replacements in 2007 was $19 billion, and $26 billion for knees, according to the federal Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Those figures are expected to rise significantly in the coming decade, Dr. White said. So protecting your joints will do more than save wear and tear on you and your budget. You could also be doing your part to curtail the national health care bill.

If your joints are still intact, or just beginning to creak, here are some ways to keep osteoarthritis at bay.

CONTROL YOUR WEIGHT

The more you weigh, the more pressure on your joints, which can lead to joint damage. When you walk, each knee bears a force equivalent to three to six times the body’s weight. If you weigh a mere 120 pounds, your knees are taking a 360-pound, or more, beating with every step.

Studies have found a connection between being overweight and developing osteroarthritis of the knees, and to a lesser extent the hips. One recent review found that 27 percent of hip replacements and 69 percent of knee replacements might be attributed to obesity.

For reasons not well understood, weight is more of risk factor for women than men.

“A woman’s risk for developing O.A. is linearly related to her weight,” Dr. David Felson, a rheumatologist and arthritis prevention specialist at Boston University School of Medicine, said, referring to osteoarthritis.

“Men who are moderately overweight are not as at high a risk as a woman of the same weight,” Dr. Felson said.

But a woman can substantially lower her risk by shedding pounds. One study in which Dr. Felson was a co-author found that when a woman lost 10 pounds, her risk of osteoarthritis of the knee dropped by half.

GO LOW-IMPACT

Although no definitive link has been found between osteoarthritis of the knee and running (or any other sport), sports medicine doctors discourage their patients from running on hard pavement, playing tennis on concrete or activities like skiing over lots of moguls.

“Impact sports put too much stress on the joints, particularly the knees,” said Dr. Donald M. Kastenbaum vice chairman of orthopedic surgery at Beth Israel Medical Center in Manhattan. “These activities may lead to O.A. and they definitely can escalate the progression of the condition.”

If you run regularly, try to do so on a track or treadmill and consider swapping one run a week for something low-impact like swimming, biking, lifting weights or tai chi.

AVOID INJURY

Easier said than done, of course. But major injuries, typically the type that require surgery, greatly increase your risk for osteoarthritis.

According to one big study, 10 to 20 years after a person injures the anterior cruciate ligament or menisci of the knee, that person has a 50 percent chance of having arthritis of the knee.

Those rates are even higher when the injury happens in your 30s or 40s, Dr. Felson said. “As you move into middle age, it’s crucial to avoid sports that predispose you to injury,” he said.

Weekend warriors, who sit at a desk Monday through Friday, and then run or play basketball for five hours straight on the weekend, are at a high risk for injury, and thus for osteoarthritis.

GET FIT

It makes sense. The better toned your muscles are, the less likely you are to injure yourself (unless you are also playing football every Saturday morning).

And “building muscles up around joints acts like a shock absorber, spreading stress across the joint,” said Dr. Laith M. Jazrawi, chief of the sports medicine division at NYU Hospital for Joint Diseases. Pilates, moderate weight lifting, vinyasa yoga and swimming are all nonimpact forms of exercise that firm up your muscles without jeopardizing your cartilage.

No definitive link exists between increased flexibility and lower, or higher, rates of osteoarthritis. But some doctors interviewed said they believed that by regularly stretching your muscles you are less likely to injure your joints. It can’t hurt to judiciously stretch your muscles after a workout. And even if it won’t protect your joints from deterioration, it will certainly make your muscles feel better.

BE SKEPTICAL

Don’t waste your money on specialized nutrients. Shark cartilage, glucosamine and chondroitin — popular supplements marketed for healthy joints — can be expensive and probably are of limited benefit, many specialists say.

“There’s some evidence to suggest glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate may be helpful in O.A. once it has started, but overall the results are inconclusive,” Dr. Jazrawi said. As for shark cartilage, there is no evidence to suggest that it has any benefit for treating the symptoms or the disease, he said. Joints are like car parts. With proper care and maintenance, they last longer.

Less Invasive Hip Surgeries Make Inroads

By Jane E. Brody : NY Times Article : February 9, 2010

Hip replacement is one of the most successful operations in all of medicine, which prompts many orthopedic surgeons to think, as one leader in the field put it, “Why change something that doesn’t need fixing?”

But that leader, Dr. Robert Berghoff; his colleagues at Arizona Orthopedic Associates in Phoenix; and other orthopedic surgeons around the country believed that improvements were possible, especially with regard to reducing complications and speeding recovery.

The technique these surgeons use is called anterior hip replacement, one of several minimally invasive operations that are associated with a shorter hospital stay, smaller incision, less trauma to muscles, less pain and blood loss, reduced risk of dislocation after surgery, faster healing and a quicker return to normal activities.

“The morning after surgery I was able to walk without a walker or even a cane and could put my full weight on the operated side,” Jack White, a 71-year-old personal trainer from Paradise Valley, Ariz., said in an interview. “The next day I walked 50 yards without a limp and was able to go home, where I did physical therapy five days a week for two weeks. On Day 5, I walked a mile and a half, and in Week 4, I taught my aerobics class and played 18 holes of golf with no pain and no problem.”

The operation was introduced in the United States more than two decades ago by Dr. Joel M. Matta of the St. John’s Health Center in Santa Monica, Calif., who also helped design a special operating table to simplify the procedure.

Another minimally invasive form of hip replacement, the PATH technique, was developed by a Los Angeles orthopedist, Dr. Brad L. Penenberg.

Dr. Patrick Meere of New York University Langone Medical Center and the Hospital for Joint Diseases in New York tells me this method has the same advantages as the anterior approach, results in no activity limitations and also offers a safety net: If anything goes wrong during the procedure, the problem can be repaired without having to do a more extensive operation.

Traditional Method

Nearly 200,000 hip replacements are performed each year in the United States, and the number continues to grow as the population ages. There is no age limit for this elective operation unless an underlying health problem makes any operation too risky.

The usual reasons for hip replacement are osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis and traumatic arthritis, all of which can cause pain and stiffness that limit mobility and the ability to perform activities of daily living. Most patients try less drastic measures — physical therapy, medications (pain relievers, anti-inflammatory drugs and glucosamine supplements), injections of hyaluronic acid and walking aids — before deciding that surgery is their best hope for escaping chronic pain and disability.

To appreciate the potential benefits of minimally invasive methods, it helps to know how hip replacements are usually done.

General or spinal anesthesia is used for the operation, which typically takes one to two hours. An incision 10 to 12 inches long is made through the muscles on the side of the hip to expose the hip joint, and the diseased bone tissue and cartilage are removed. An artificial socket is then implanted into the pelvic bone and a metal stem is inserted into the thigh bone, the top of which is replaced by a metallic ball to create a ball-and-socket joint that mimics the function of a natural hip joint.

The average hospital stay is four or five days, followed in most cases by extensive rehabilitation. Patients are told not to cross their legs or bend at the hip more than 90 degrees after surgery — in some cases indefinitely, because these motions can cause dislocation of the replaced joint that requires a repeat operation.

Possible complications of the surgery include blood clots, infection, fracture and a change in leg length. Possible delayed complications include dislocation of the new joint, breaking or loosening of the prosthesis and stiffening of the tissues around the joint. Although modern materials have extended the life of implants to 20 years or so, they can eventually wear out and require replacement.

Patients should prepare ahead for limitations associated with postoperative recovery. The American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons suggests these home modifications: safety bars or handrails for the shower or bath; a raised toilet seat and shower bench; a long-handled sponge and shower hose; handrails on all stairways; removal of all loose carpets and electrical cords in walking areas; a dressing stick, sock aid and long-handled shoe horn; a reacher to help you grab objects without bending or climbing; a stable chair with firm cushion, back and arms; and firm pillows for chairs, sofas and cars so you can sit with knees lower than your hips.

You might also rent a commode if there is no bathroom on the first floor; arrange for help with cooking, shopping, bathing and laundry for several weeks; prepare and freeze individual meals in advance of surgery; and place frequently used kitchen, bathroom and clothing items within easy reach.

The Minimal Approach

Studies comparing long-term results of minimally invasive hip replacement with more traditional surgery have had mixed results, and all forms of hip replacement have benefited from improved anesthetic and pain management techniques. Surgeons who routinely use less invasive methods maintain that there are decided advantages for most patients, even though the operation itself can take somewhat longer.

Perhaps most important is that major muscles in the buttocks and thigh that help to stabilize the hip joint are not cut, reducing the risk of dislocation and speeding recovery. Patients spend less time in the hospital and, like Mr. White, return to normal life more quickly.

Still, Dr. Berghoff emphasized, it takes time to become adept at the procedure, as with any complex surgery. In choosing a surgeon, ask how many of the operations the surgeon has done using the proposed technique and with what results.

Regardless of the type of operation, as Mr. White found, it helps to have supporting muscles as strong as possible before surgery, perhaps through several sessions with a physical therapist if the patient’s condition allows it.

Concerns Over ‘Metal on Metal’ Hip Implants

By Barry Meier : NY Times Article : March 3, 2010

Some of the nation’s leading orthopedic surgeons have reduced or stopped use of a popular category of artificial hips amid concerns that the devices are causing severe tissue and bone damage in some patients, often requiring replacement surgery within a year or two.

In recent years, such devices, known as “metal on metal” implants, have been used in about one-third of the approximately 250,000 hip replacements performed annually in this country. They are used in conventional hip replacements and in a popular alternative procedure known as resurfacing.

The devices, whose ball-and-socket joints are made from metals like cobalt and chromium, became widely used in the belief that they would be more durable than previous types of implants.

The cause and the scope of the problem are not clear. But studies in recent years indicate that in some cases the devices can quickly begin to wear, generating high volumes of metallic debris that is absorbed into a patient’s body. That situation can touch off inflammatory reactions that cause pain in the groin, death of tissue in the hip joint and loss of surrounding bone.

Doctors at leading orthopedic centers like Rush University Medical Center in Chicago and the Mayo Clinic in Minneapolis say they have treated a number of patients over the last year with problems related to the metal debris.

Artificial hips, intended to last 15 years or more, need early replacement far more frequently for reasons like dislocation than because of problems caused by metallic debris. But surgeons say that when metal particles are the culprit, the procedures to replace the devices can be far more complex and can leave some patients with lasting complications.

“What we see is soft-tissue destruction and destruction of bone,” said Dr. Young-Min Kwon, an orthopedic surgeon at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

A recent editorial in a medical journal for orthopedic surgeons, The Journal of Arthroplasty, urged doctors to use the metal-on-metal devices only with “great caution, if at all.”

The limited studies conducted so far estimate that 1 to 3 percent of implant recipients could be affected by the problem. Given the large number of people who have received metal devices, that could mean thousands of patients in the United States. Reports suggest that women are far more likely than men to be affected.

All the major orthopedics makers sell these devices. Several companies said in statements that the implants did not pose a significant risk and that the incidence of metal debris problems was extremely low.

For example, Zimmer Holdings, one of this country’s biggest producers of artificial joints, said in a statement that published data “suggests that ion release levels from Zimmer’s metal-on-metal hip systems are commensurate with other metal-on-metal systems in the industry, and are not associated with significant risk to patients.”

But some surgeons are concerned that they may only now be seeing the leading edge of a mounting problem. The current generation of metal-on-metal devices is still relatively new, having been used increasingly over the last decade.

Studies show that the devices can shed atomic-size particles of metals like chromium and cobalt that can be readily absorbed by tissue or enter the bloodstream.

Surgeons at Rush University Medical Center have performed about two dozen replacement procedures because of metal debris over the last year, said Dr. Joshua J. Jacobs, the head the orthopedic surgery department there. A similar number of patients have had metal-on-metal hips removed at the Mayo Clinic, according to Dr. Daniel J. Berry, Mayo’s head of orthopedic surgery.

Dr. Berry added that surgeons at the Mayo Clinic had reduced by 80 percent their use of metal-on-metal implants over the last year in favor of those made from other materials, like combinations of metal and plastic. Other doctors said that to be cautious they were also scaling back their use of the all-metal implants until the scientific evidence became clearer.

It is not clear whether some makers’ devices are more prone to the debris problem than others. But some experts argue that some manufacturers, in a rush to meet the demand for metal-on-metal devices, marketed some poorly designed implants and that some doctors fail to properly implant even well-designed ones.

“It is a sad travesty,” said Dr. Harlan C. Amstutz, an orthopedic surgeon in Los Angeles who helped pioneer hip resurfacing. “It is design-related and it is technique-related.”

Dr. Amstutz, who developed a hip-resurfacing system sold by the Wright Medical Group, said he believed that resurfacing, which typically uses all-metal components, was safe. The procedure, which preserves more thigh bone than in a conventional hip replacement, is aimed at younger, more active patients who may need several hip replacements in their lifetimes.

Several orthopedic surgeons agreed that the procedure was generally safe. But those doctors said they were limiting resurfacing procedures to men under 55 with strong bones because other patients, including women, did not have good outcomes.

One hip device company, Smith & Nephew, which markets an implant called the Birmingham hip resurfacing system, said that data from an implant registry in Australia showed that fewer than 1 percent of patients using that product had reactions to metal.

Another major producer, the DePuy Orthopaedics division of Johnson & Johnson, said that, “as with other materials, metal-on-metal wear debris may cause soft tissue reaction in the area of a hip implant in a small percentage of cases.”

All hip devices, regardless of the material, create debris as the ball rotates and rubs against the cuplike socket. But in metal-on-metal hips, either because of poor design or poor implant technique, the ball can sometimes press against the cup’s edge. This creates a chisel-like effect referred to as “edge-loading” that produces large volumes of microscopic metallic particles that can cause havoc in some patients.

Three years ago, for example, Gregory Smith, 35, of Milan, Ill., got a metal-on-metal joint to correct a congenital hip disorder. Mr. Smith, an unemployed heavy-equipment operator, said that he began experiencing severe pain almost immediately.

Finally, last year, he went to Rush University, where an orthopedic surgeon, Dr. Brett Levine, removed the device and replaced it. The soft tissue surrounding Mr. Smith’s left hip was severely inflamed, and some of it had died.

“It was like having a fire taken out of your body,” Mr. Smith said of the removed joint.

Dr. Levine said he was now replacing metal-on-metal devices at the rate of one a month. He said that the surgeon who had implanted Mr. Smith’s artificial hip had installed the cup component slightly askew. The misalignment, he said, probably would not have created a serious problem if the device had not been metal on metal.

“These implants are less forgiving,” Dr. Levine said.