- RETIREMENT ANNOUNCEMENT

- HOME PAGE

- "MYCHART" the new patient portal

- BELMONT MEDICAL ASSOCIATES

- MOUNT AUBURN HOSPITAL

- EMERGENCIES

- PRACTICE PHILOSOPHY

- MY RESUME

- TELEMEDICINE CONSULTATION

- CONTACT ME

- LAB RESULTS

- ePRESCRIPTIONS

- eREFERRALS

- RECORD RELEASE

- MEDICAL SCRIBE

- PHYSICIAN ASSISTANT (PA)

- Medicare Annual Wellness Visit

- Case management/Social work

- Quality Care Measures

- Emergency closing notice

- FEEDBACK

- Talking to your doctor

- Choosing..... and losing a doctor

- INDEX A - Z

- ALLERGIC REACTIONS

- Alternative Medicine

- Alzheimer's Disease

- Bladder Problems

- Blood disorders

- Cancer Concerns

- GENETIC TESTING FOR HEREDITARY CANCER

- Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

- Controversial Concerns

- CPR : Learn and save a life

- CRP : Inflammatory marker

- Diabetes Management

- Dizziness, Vertigo,Tinnitus and Hearing Loss

- EXERCISE

- FEMALE HEALTH

-

GASTROINTESTINAL topics

- Appendicitis

- BRAT diet

- Celiac Disease or Sprue

- Crohn's Disease

- Gastroenterologists for Colon Cancer Screening

- Colonoscopy PREP

- Constipation

- Gluten sensitivity, but not celiac disease

- Heartburn and GERD

- Hemorrhoids and Anal fissure

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- NASH : Non Alcoholic Steato Hepatitis

- FEET PROBLEMS

- HEART RELATED topics

-

INFECTIOUS DISEASES

- Antibiotic Resistance

- Cat bites >

- Clostridia difficile infection - the "antibiotic associated germ"

- CORONA VIRUS

- Dengue Fever and Chikungunya Fever

- Food borne illnesses

- Shingles Vaccine

- Hepatitis B

- Hepatitis C

- Herpes

- Influenza

- Helicobacter pylori - the "ulcer germ"

- HIV Screening

- Lyme and other tick borne diseases

- Measles

- Meningitis

- MRSA (Staph infection)

- Norovirus

- Sexually Transmitted Diseases

- Shingles (Herpes Zoster)

- Sinusitis

- West Nile Virus

- Whooping Cough (Pertussis)

- Zika virus and pregnancy

- INSURANCE related topics

- KIDNEY STONES

- LEG CRAMPS

- LIBRARY for patients

- LIFE DECISIONS

- MALE HEALTH

- Medication/Drug side effects

- MEDICAL MARIJUANA

- MENTAL HEALTH

- Miscellaneous Articles

-

NUTRITION - EXERCISE - WEIGHT

- Cholesterol : New guidelines for treatment

- Advice to lower your cholesterol

- Cholesterol : Control

- Cholesterol : Raising your HDL Level

- Exercise

- Food : Making Smart Choices

- Food : Making Poor Choices

- Food : Grape Fruit and Drug Interaction

- Food : Vitamins, Minerals and Supplements

- Omega 3 fatty acids

- Vitamin B12 deficiency

- Vitamin D

- Weight Loss

- ORTHOPEDICS

- PAIN

- PATIENTS' RIGHTS

- SKIN

- SLEEP

- SMOKING

- STROKE

- THYROID

- SUBSTANCE ABUSE

- Travel and Vaccination

- TREMOR

- Warfarin Anticoagulation

- OTHER STUFF FOLLOWS

- Fact or Opinion?

- Hippocratic Oath

- FREE ADVICE.......for what its worth!

- LAUGHTER.....is the best medicine

- Physicians Pet Peeves

- PHOTO ALBUM - its not all work!

- Cape Town, South Africa

- Tribute page

- The 100 Club

- Free Wi-Fi

As Dengue Fever Sweeps India, a Slow Response Stirs Experts’ Fears

By Gardiner Harris : NY Times : November 6, 2012

An epidemic of dengue fever in India is fostering a growing sense of alarm even as government officials here have publicly refused to acknowledge the scope of a problem that experts say is threatening hundreds of millions of people, not just in India but around the world.

India has become the focal point for a mosquito-borne plague that is sweeping the globe. Reported in just a handful of countries in the 1950s, dengue (pronounced DEN-gay) is now endemic in half the world’s nations.

“The global dengue problem is far worse than most people know, and it keeps getting worse,” said Dr. Raman Velayudhan, the World Health Organization’s lead dengue coordinator.

The tropical disease, though life-threatening for a tiny fraction of those infected, can be extremely painful. Growing numbers of Western tourists are returning from warm-weather vacations with the disease, which has reached the shores of the United States and Europe. Last month, health officials in Miami announced a case of locally acquired dengue infection.

For those who arrive in India as adults, “you have a reasonable expectation of getting dengue after a few months,” said Dr. Joseph M. Vinetz, a professor at the University of California at San Diego. “If you stay for a longer period, it’s a certainty.”

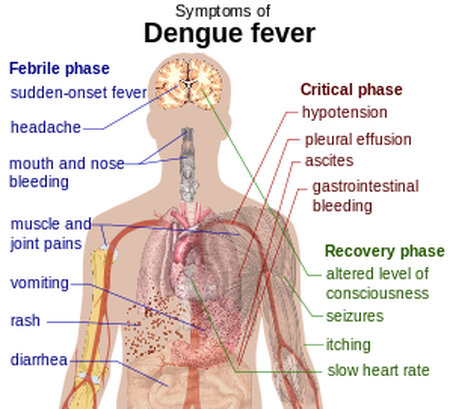

The reason that such an extensive epidemic can hide in plain sight is that as many as 80 percent of dengue infections cause only mild symptoms of fatigue, said Anthony S. Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. For many, the disease is experienced as “maybe just a fever that someone shrugs off.”

But the remaining 20 percent may be affected by more serious flulike symptoms, with high fever, vomiting, searing pain behind the eyes, skin rash, and muscle and joint aches that can be so intense that the illness has been dubbed “breakbone fever.”

The acute part of the illness generally passes within two weeks, but symptoms of fatigue and depression can linger for months. In about 1 percent of cases, dengue advances to a life-threatening cascade of immune responses known as hemorrhagic or shock dengue.

This potentially mortal condition generally happens only after a second dengue infection. There are four strains of the dengue virus, and infection with a second strain can fool the immune system, allowing the virus to replicate. When the body finally realizes its mistake, it floods the system with so many immune attackers that they are poisonous. Such patients must be provided intravenous fluids and round-the-clock care to avoid death.

Twenty years ago, just one of every 50 tourists who returned from the tropics with fever was infected by dengue; now, it is one in six, said Dr. Velayudhan, the W.H.O. official. The Portuguese archipelago of Madeira is in the midst of an epidemic.

On Oct. 9, Puerto Rico’s Health Department declared a dengue epidemic after at least six people died and nearly 5,000 people were sickened.

The great danger of having hundreds of millions of people in India with undiagnosed and unacknowledged primary infections is that a sudden shift in the circulating dengue strain could cause a widespread increase in life-threatening illnesses.

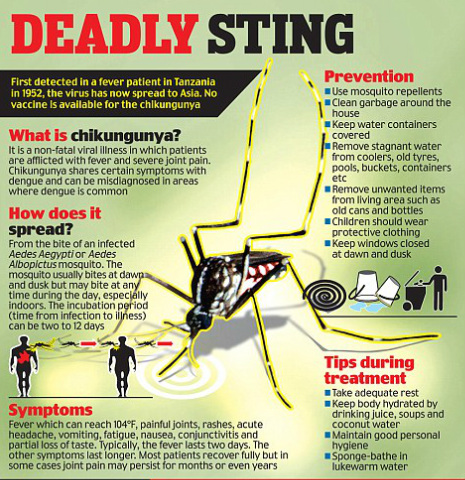

Chikungunya fever :

Virus Advances Through East Caribbean

By Frances Robles : February 8, 2014

The chikungunya (pronounced chick-en-GUN-ya) virus, transmitted by mosquitoes, has been found in Martinique, the British Virgin Islands, Dominica, French Guiana, Guadeloupe, St. Barthelemy, and the French and Dutch sides of St. Martin. Like dengue fever, the virus causes fever and joint and muscle pain, but chikungunya is rarely fatal.

A painful mosquito-borne virus common in Africa and Asia has advanced quickly throughout the eastern Caribbean in the past two months, raising the prospect that a once-distant illness will become entrenched throughout the region, public health experts say.

Chikungunya fever, a viral disease similar to dengue, was first spotted in December on the French side of St. Martin and has now spread to seven other countries, the authorities said. About 3,700 people are confirmed or suspected of having contracted it.

It was the first time the malady was locally acquired in the Western Hemisphere. Experts say conditions are ripe for the illness to spread to Central and South America, but they say it is unlikely to affect the United States.

“It is an important development when disease moves from one continent to another,” said Dr. C. James Hospedales, the executive director of the Caribbean Public Health Agency in Trinidad. “Is it likely here to stay? Probably. That’s the pattern we have observed elsewhere.”

Chikungunya fever is particularly troublesome for places such as St. Martin, a French and Dutch island 230 miles east of Puerto Rico, where two million tourists visit annually. In an effort to keep the disease from affecting tourism and crippling the island economy, local governments began islandwide campaigns of insecticide fogging last week and house-to-house cleanups of places where mosquitoes could breed.

The French side of St. Martin to the north has had 476 confirmed cases, the largest cluster in all of the islands, while the Dutch side has had 40 cases, according to the Caribbean Public Health Agency.

Already, the travel search engine Kayak said there was a 75 percent decline in searches for St. Martin in the past three weeks, compared to the same period last year.

Searches for Martinique, which has had 364 confirmed chikungunya cases, were down 18 percent.

“When I read about chikungunya, I thought: ‘There’s a mosquito in St. Martin waiting for me, rubbing its little feet together waiting to get a hold of me,’ ” said Betsy Carter, a New York City novelist who was scheduled to travel to St. Martin with two other couples in January. “So we all decided not to go.”

Ms. Carter was particularly nervous, because she had contracted a different disease from a sand fly a few years ago in Belize, which caused half her hair to fall out. Despite having bought insurance, last month the three couples lost $9,000 they paid to stay at Dreamin Blue, a luxurious villa overlooking Happy Bay.

“The owners said they would spray the house,” Ms. Carter said. “But what if you want to leave the house?”

Public health and tourism officials on the islands are urging visitors to wear long sleeves and insect repellent high in DEET.

“Not a lot of bookings were canceled, but there were a few people not understanding exactly what this was, thinking it was a pandemic on a large scale,” said Kate Richardson, a spokeswoman for the French St. Martin’s tourism board. “People got a bit scared, and a few of them have declined to take their trips.”

She said the hotel association had not reported the number of cancellations.

Chikungunya (pronounced chik-en-GUN-ya) causes high fever and muscle pain, symptoms similar to those caused by dengue fever, which has swept the Caribbean for several years. While dengue can be fatal and chinkungunya rarely is, experts said the effects of chikungunya, such as pain in the small joints, tend to last longer, sometimes for months.

Ann M. Powers, a vector-borne disease specialist at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, said past outbreaks in other nations had incapacitated people because the pain in their wrists and ankles was so severe.

“They miss school and work,” she said. “It’s quite a drain on resources and the work force.”

Nora E. Kelly, an Ontario restaurant comptroller, is leaving for St. Martin on Sunday with a group of 28 friends who have tracked the disease closely and loaded up on insect repellent.

“It’s been a miserable winter,” Ms. Kelly said. “Chikungunya is not going to stop me from getting on that plane in a million years.”

The health ministry in Sint Maarten, the Dutch side of the Caribbean island, said no Canadian, European or American tourist at a resort had fallen ill.

“In order to keep the virus under control, various proactive steps have been taken and continue to be taken by both the Dutch and French authorities,” Lorraine Scot, a spokeswoman for the ministry, said in a statement.

Those steps include fogging, surveillance of suspected cases, biological lab investigations and a public-awareness campaign alerting people to the dangers of standing water, where mosquitoes lay their eggs.

The virus has also been detected in the British Virgin Islands, Dominica, French Guiana, Guadeloupe and St. Barthélemy.

“It certainly has the potential to move to a lot of other places in the Western Hemisphere,” Ms. Powers said. “All of Central America and big parts of South America would certainly be susceptible.”

The disease is not likely to spread to the United States, because it is carried by two species of mosquito that prefer warm climates.

Chikungunya was first identified in Tanzania in 1952. The name translates to “that which bends up” in the Kimakonde language of Mozambique.

According to the World Health Organization, since 2005, nearly two million cases have been reported in India, Indonesia, Malvides, Myanmar and Thailand.

An epidemic hit Northern Italy in 2007, and in 2006 thousands were sickened in Réunion, a French island east of Madagascar.

Virus Advances Through East Caribbean

By Frances Robles : February 8, 2014

The chikungunya (pronounced chick-en-GUN-ya) virus, transmitted by mosquitoes, has been found in Martinique, the British Virgin Islands, Dominica, French Guiana, Guadeloupe, St. Barthelemy, and the French and Dutch sides of St. Martin. Like dengue fever, the virus causes fever and joint and muscle pain, but chikungunya is rarely fatal.

A painful mosquito-borne virus common in Africa and Asia has advanced quickly throughout the eastern Caribbean in the past two months, raising the prospect that a once-distant illness will become entrenched throughout the region, public health experts say.

Chikungunya fever, a viral disease similar to dengue, was first spotted in December on the French side of St. Martin and has now spread to seven other countries, the authorities said. About 3,700 people are confirmed or suspected of having contracted it.

It was the first time the malady was locally acquired in the Western Hemisphere. Experts say conditions are ripe for the illness to spread to Central and South America, but they say it is unlikely to affect the United States.

“It is an important development when disease moves from one continent to another,” said Dr. C. James Hospedales, the executive director of the Caribbean Public Health Agency in Trinidad. “Is it likely here to stay? Probably. That’s the pattern we have observed elsewhere.”

Chikungunya fever is particularly troublesome for places such as St. Martin, a French and Dutch island 230 miles east of Puerto Rico, where two million tourists visit annually. In an effort to keep the disease from affecting tourism and crippling the island economy, local governments began islandwide campaigns of insecticide fogging last week and house-to-house cleanups of places where mosquitoes could breed.

The French side of St. Martin to the north has had 476 confirmed cases, the largest cluster in all of the islands, while the Dutch side has had 40 cases, according to the Caribbean Public Health Agency.

Already, the travel search engine Kayak said there was a 75 percent decline in searches for St. Martin in the past three weeks, compared to the same period last year.

Searches for Martinique, which has had 364 confirmed chikungunya cases, were down 18 percent.

“When I read about chikungunya, I thought: ‘There’s a mosquito in St. Martin waiting for me, rubbing its little feet together waiting to get a hold of me,’ ” said Betsy Carter, a New York City novelist who was scheduled to travel to St. Martin with two other couples in January. “So we all decided not to go.”

Ms. Carter was particularly nervous, because she had contracted a different disease from a sand fly a few years ago in Belize, which caused half her hair to fall out. Despite having bought insurance, last month the three couples lost $9,000 they paid to stay at Dreamin Blue, a luxurious villa overlooking Happy Bay.

“The owners said they would spray the house,” Ms. Carter said. “But what if you want to leave the house?”

Public health and tourism officials on the islands are urging visitors to wear long sleeves and insect repellent high in DEET.

“Not a lot of bookings were canceled, but there were a few people not understanding exactly what this was, thinking it was a pandemic on a large scale,” said Kate Richardson, a spokeswoman for the French St. Martin’s tourism board. “People got a bit scared, and a few of them have declined to take their trips.”

She said the hotel association had not reported the number of cancellations.

Chikungunya (pronounced chik-en-GUN-ya) causes high fever and muscle pain, symptoms similar to those caused by dengue fever, which has swept the Caribbean for several years. While dengue can be fatal and chinkungunya rarely is, experts said the effects of chikungunya, such as pain in the small joints, tend to last longer, sometimes for months.

Ann M. Powers, a vector-borne disease specialist at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, said past outbreaks in other nations had incapacitated people because the pain in their wrists and ankles was so severe.

“They miss school and work,” she said. “It’s quite a drain on resources and the work force.”

Nora E. Kelly, an Ontario restaurant comptroller, is leaving for St. Martin on Sunday with a group of 28 friends who have tracked the disease closely and loaded up on insect repellent.

“It’s been a miserable winter,” Ms. Kelly said. “Chikungunya is not going to stop me from getting on that plane in a million years.”

The health ministry in Sint Maarten, the Dutch side of the Caribbean island, said no Canadian, European or American tourist at a resort had fallen ill.

“In order to keep the virus under control, various proactive steps have been taken and continue to be taken by both the Dutch and French authorities,” Lorraine Scot, a spokeswoman for the ministry, said in a statement.

Those steps include fogging, surveillance of suspected cases, biological lab investigations and a public-awareness campaign alerting people to the dangers of standing water, where mosquitoes lay their eggs.

The virus has also been detected in the British Virgin Islands, Dominica, French Guiana, Guadeloupe and St. Barthélemy.

“It certainly has the potential to move to a lot of other places in the Western Hemisphere,” Ms. Powers said. “All of Central America and big parts of South America would certainly be susceptible.”

The disease is not likely to spread to the United States, because it is carried by two species of mosquito that prefer warm climates.

Chikungunya was first identified in Tanzania in 1952. The name translates to “that which bends up” in the Kimakonde language of Mozambique.

According to the World Health Organization, since 2005, nearly two million cases have been reported in India, Indonesia, Malvides, Myanmar and Thailand.

An epidemic hit Northern Italy in 2007, and in 2006 thousands were sickened in Réunion, a French island east of Madagascar.

Beware of the bite that causes chikungunya

By Karen Weintraub : Boston Globe : December 15, 2014

It starts with a seemingly innocuous mosquito bite — often not even noticed.

Four or five mornings later, the aching sets in. A reddish rash can spread over arms, legs, and face. Fever spikes. Some patients complain of headaches.

Mostly, though, it’s the joint pain they later remember. Legs that throb like they’ve just run a marathon, arms that feel like they’ve competed at rugby.

For most people, a bout of the mosquito-borne disease chikungunya ends about a week after it starts. For a small percentage of people, the joint pain can linger for weeks, months, or even forever.

The virus — pronounced chick-un-GOON-ya — used to infect people mainly on the other side of the world. But over the last year, it has rampaged through the Caribbean and Latin America infecting nearly 1 million people. It has spread into Florida and Puerto Rico, and threatens to keep moving northward.

“Whatever comes to the Caribbean and Latin America generally makes its way to the mainland United States,” said Dr. Mark Gendreau, vice chairman of emergency medicine at Lahey Hospital and Medical Center in Burlington.

The infection is rarely lethal, but the pain can be debilitating.

Although only a handful of cases have been reported in Massachusetts over the last six months — one or two each at Tufts, Massachusetts General Hospital, and Boston Medical Center — infectious disease doctors are anticipating more this winter as people head for warmer climates for vacation.

“It’s just a matter of time,” Gendreau said.

As of late last month, according to the Pan American Health Organization, more than 120,000 people had been infected in El Salvador, nearly half a million in the Dominican Republic, and thousands in the vacation destinations of Jamaica, Barbados, and Curacao.

Doctors say it’s relatively easy for travelers to protect themselves if they’re willing to cover up and wear mosquito repellent.

Luckily for beach-goers, the mosquitoes don’t like bright sunlight, and only hover around sources of fresh water. So lying on a beach should be safe, unless there are, say, large flower pots that have been generously watered or other pools of standing water nearby. Gendreau suggests golfers wear long sleeves, pants, and bug spray.

The mosquitoes that carry chikungunya — Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus — are the same species that can carry dengue, West Nile, and Eastern Equine Encephalitis. Unlike mosquitoes that carry malaria, the ones that bring chikungunya are active during the day.

There are no pills that can protect against chikungunya. And there is no specific treatment for the virus, other than supportive care, such as pain relievers and extra fluids.

But the absence of preventive drugs or treatment doesn’t mean people should skip the doctor if they think they might be infected, said Dr. Natasha Hochberg, co-director of the travel clinic at Boston Medical Center. It’s important to rule out other potentially life-threatening diseases, she said.

Hochberg said she sees no reason for people traveling to Florida to worry — their chances of contracting chikungunya are small — but people headed farther south should take precautions, such as covering their limbs and wearing bug spray.

Although the United States has been largely immune to tropical diseases in recent decades, the changing climate, more extensive travel, and the mosquito’s ability to adapt may not protect us much longer.

“Chikungunya is a classic example of the potential for extensive spread of infectious diseases,” said Dr. Edward T. Ryan, director of Tropical Medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital. “It just reinforces that there are constantly emerging infectious diseases.”

About 100 people have already brought chikungunya to Florida, where they then were bitten by local mosquitoes, allowing the virus to spread there, Lahey’s Gendreau said. In Massachusetts, where the freezing winters kill off most mosquitoes, we probably won’t see widespread chikungunya infections, he said.

But as mosquitoes adapt “and become more comfortable in moderate to even cold climates, those diseases we normally would just see in tropical areas become more prominent here,” Gendreau said.

Chikungunya was first described in 1952 in southern Tanzania, where it was named in the local language, meaning “to become contorted” — which described what people looked like when they were bent over in pain caused by the illness.

The virus spread across the Indian Ocean in recent decades, infecting millions in India, and arrived in the Caribbean last December. In mosquito-prone areas, chikungunya usually rips through a population, infecting large percentages, said Mass. General’s Ryan. Those who get chikungunya generally become immune after their first infection.

So far, drug development has been slow, in part because the disease is rarely lethal, and has been concentrated in countries facing more serious diseases, like malaria.

But in 2007, the virus struck a small French-owned island in the Indian Ocean called La Réunion, said Dr. Erich Tauber, a European vaccine developer.

Within 14 months of its arrival on the island, about 40 percent of the 800,000 residents had caught the disease, and European companies started to think seriously about developing a vaccine, said Tauber, CEO of Themis Bioscience, an Austrian biotech that recently began testing a possible vaccine in people.

Themis’s vaccine test went well, research shows, with only minor side effects reported. If testing in more people proves safe and effective, the vaccine could be available to the public in about four years, Tauber said.

In the meantime, Nita Bhat suggests that others take the precautions she didn’t. In 2009, Bhat went to her birth village in India and after neglecting to use bug spray or wear long sleeves got bitten by a mosquito carrying chikungunya.

Then a student at Stanford University, Bhat woke up her last morning in India feeling sore all over. By the time she had flown the 2½ hours from Bangalore to Delhi, she couldn’t walk and needed a wheelchair to reach her connecting flight.

Bhat, now an educational consultant in Boston, was one of the unlucky ones whose disease lingered. For most of that year at Stanford, she needed a golf cart to get around campus and had lingering pains and terrible fatigue. Slowly, over the next six months, the aches subsided and her energy returned.

“I don’t want anyone else to get chikungunya,” Bhat said recently. “I think it’s a miserable disease.”

By Karen Weintraub : Boston Globe : December 15, 2014

It starts with a seemingly innocuous mosquito bite — often not even noticed.

Four or five mornings later, the aching sets in. A reddish rash can spread over arms, legs, and face. Fever spikes. Some patients complain of headaches.

Mostly, though, it’s the joint pain they later remember. Legs that throb like they’ve just run a marathon, arms that feel like they’ve competed at rugby.

For most people, a bout of the mosquito-borne disease chikungunya ends about a week after it starts. For a small percentage of people, the joint pain can linger for weeks, months, or even forever.

The virus — pronounced chick-un-GOON-ya — used to infect people mainly on the other side of the world. But over the last year, it has rampaged through the Caribbean and Latin America infecting nearly 1 million people. It has spread into Florida and Puerto Rico, and threatens to keep moving northward.

“Whatever comes to the Caribbean and Latin America generally makes its way to the mainland United States,” said Dr. Mark Gendreau, vice chairman of emergency medicine at Lahey Hospital and Medical Center in Burlington.

The infection is rarely lethal, but the pain can be debilitating.

Although only a handful of cases have been reported in Massachusetts over the last six months — one or two each at Tufts, Massachusetts General Hospital, and Boston Medical Center — infectious disease doctors are anticipating more this winter as people head for warmer climates for vacation.

“It’s just a matter of time,” Gendreau said.

As of late last month, according to the Pan American Health Organization, more than 120,000 people had been infected in El Salvador, nearly half a million in the Dominican Republic, and thousands in the vacation destinations of Jamaica, Barbados, and Curacao.

Doctors say it’s relatively easy for travelers to protect themselves if they’re willing to cover up and wear mosquito repellent.

Luckily for beach-goers, the mosquitoes don’t like bright sunlight, and only hover around sources of fresh water. So lying on a beach should be safe, unless there are, say, large flower pots that have been generously watered or other pools of standing water nearby. Gendreau suggests golfers wear long sleeves, pants, and bug spray.

The mosquitoes that carry chikungunya — Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus — are the same species that can carry dengue, West Nile, and Eastern Equine Encephalitis. Unlike mosquitoes that carry malaria, the ones that bring chikungunya are active during the day.

There are no pills that can protect against chikungunya. And there is no specific treatment for the virus, other than supportive care, such as pain relievers and extra fluids.

But the absence of preventive drugs or treatment doesn’t mean people should skip the doctor if they think they might be infected, said Dr. Natasha Hochberg, co-director of the travel clinic at Boston Medical Center. It’s important to rule out other potentially life-threatening diseases, she said.

Hochberg said she sees no reason for people traveling to Florida to worry — their chances of contracting chikungunya are small — but people headed farther south should take precautions, such as covering their limbs and wearing bug spray.

Although the United States has been largely immune to tropical diseases in recent decades, the changing climate, more extensive travel, and the mosquito’s ability to adapt may not protect us much longer.

“Chikungunya is a classic example of the potential for extensive spread of infectious diseases,” said Dr. Edward T. Ryan, director of Tropical Medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital. “It just reinforces that there are constantly emerging infectious diseases.”

About 100 people have already brought chikungunya to Florida, where they then were bitten by local mosquitoes, allowing the virus to spread there, Lahey’s Gendreau said. In Massachusetts, where the freezing winters kill off most mosquitoes, we probably won’t see widespread chikungunya infections, he said.

But as mosquitoes adapt “and become more comfortable in moderate to even cold climates, those diseases we normally would just see in tropical areas become more prominent here,” Gendreau said.

Chikungunya was first described in 1952 in southern Tanzania, where it was named in the local language, meaning “to become contorted” — which described what people looked like when they were bent over in pain caused by the illness.

The virus spread across the Indian Ocean in recent decades, infecting millions in India, and arrived in the Caribbean last December. In mosquito-prone areas, chikungunya usually rips through a population, infecting large percentages, said Mass. General’s Ryan. Those who get chikungunya generally become immune after their first infection.

So far, drug development has been slow, in part because the disease is rarely lethal, and has been concentrated in countries facing more serious diseases, like malaria.

But in 2007, the virus struck a small French-owned island in the Indian Ocean called La Réunion, said Dr. Erich Tauber, a European vaccine developer.

Within 14 months of its arrival on the island, about 40 percent of the 800,000 residents had caught the disease, and European companies started to think seriously about developing a vaccine, said Tauber, CEO of Themis Bioscience, an Austrian biotech that recently began testing a possible vaccine in people.

Themis’s vaccine test went well, research shows, with only minor side effects reported. If testing in more people proves safe and effective, the vaccine could be available to the public in about four years, Tauber said.

In the meantime, Nita Bhat suggests that others take the precautions she didn’t. In 2009, Bhat went to her birth village in India and after neglecting to use bug spray or wear long sleeves got bitten by a mosquito carrying chikungunya.

Then a student at Stanford University, Bhat woke up her last morning in India feeling sore all over. By the time she had flown the 2½ hours from Bangalore to Delhi, she couldn’t walk and needed a wheelchair to reach her connecting flight.

Bhat, now an educational consultant in Boston, was one of the unlucky ones whose disease lingered. For most of that year at Stanford, she needed a golf cart to get around campus and had lingering pains and terrible fatigue. Slowly, over the next six months, the aches subsided and her energy returned.

“I don’t want anyone else to get chikungunya,” Bhat said recently. “I think it’s a miserable disease.”