- RETIREMENT ANNOUNCEMENT

- HOME PAGE

- "MYCHART" the new patient portal

- BELMONT MEDICAL ASSOCIATES

- MOUNT AUBURN HOSPITAL

- EMERGENCIES

- PRACTICE PHILOSOPHY

- MY RESUME

- TELEMEDICINE CONSULTATION

- CONTACT ME

- LAB RESULTS

- ePRESCRIPTIONS

- eREFERRALS

- RECORD RELEASE

- MEDICAL SCRIBE

- PHYSICIAN ASSISTANT (PA)

- Medicare Annual Wellness Visit

- Case management/Social work

- Quality Care Measures

- Emergency closing notice

- FEEDBACK

- Talking to your doctor

- Choosing..... and losing a doctor

- INDEX A - Z

- ALLERGIC REACTIONS

- Alternative Medicine

- Alzheimer's Disease

- Bladder Problems

- Blood disorders

- Cancer Concerns

- GENETIC TESTING FOR HEREDITARY CANCER

- Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

- Controversial Concerns

- CPR : Learn and save a life

- CRP : Inflammatory marker

- Diabetes Management

- Dizziness, Vertigo,Tinnitus and Hearing Loss

- EXERCISE

- FEMALE HEALTH

-

GASTROINTESTINAL topics

- Appendicitis

- BRAT diet

- Celiac Disease or Sprue

- Crohn's Disease

- Gastroenterologists for Colon Cancer Screening

- Colonoscopy PREP

- Constipation

- Gluten sensitivity, but not celiac disease

- Heartburn and GERD

- Hemorrhoids and Anal fissure

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- NASH : Non Alcoholic Steato Hepatitis

- FEET PROBLEMS

- HEART RELATED topics

-

INFECTIOUS DISEASES

- Antibiotic Resistance

- Cat bites >

- Clostridia difficile infection - the "antibiotic associated germ"

- CORONA VIRUS

- Dengue Fever and Chikungunya Fever

- Food borne illnesses

- Shingles Vaccine

- Hepatitis B

- Hepatitis C

- Herpes

- Influenza

- Helicobacter pylori - the "ulcer germ"

- HIV Screening

- Lyme and other tick borne diseases

- Measles

- Meningitis

- MRSA (Staph infection)

- Norovirus

- Sexually Transmitted Diseases

- Shingles (Herpes Zoster)

- Sinusitis

- West Nile Virus

- Whooping Cough (Pertussis)

- Zika virus and pregnancy

- INSURANCE related topics

- KIDNEY STONES

- LEG CRAMPS

- LIBRARY for patients

- LIFE DECISIONS

- MALE HEALTH

- Medication/Drug side effects

- MEDICAL MARIJUANA

- MENTAL HEALTH

- Miscellaneous Articles

-

NUTRITION - EXERCISE - WEIGHT

- Cholesterol : New guidelines for treatment

- Advice to lower your cholesterol

- Cholesterol : Control

- Cholesterol : Raising your HDL Level

- Exercise

- Food : Making Smart Choices

- Food : Making Poor Choices

- Food : Grape Fruit and Drug Interaction

- Food : Vitamins, Minerals and Supplements

- Omega 3 fatty acids

- Vitamin B12 deficiency

- Vitamin D

- Weight Loss

- ORTHOPEDICS

- PAIN

- PATIENTS' RIGHTS

- SKIN

- SLEEP

- SMOKING

- STROKE

- THYROID

- SUBSTANCE ABUSE

- Travel and Vaccination

- TREMOR

- Warfarin Anticoagulation

- OTHER STUFF FOLLOWS

- Fact or Opinion?

- Hippocratic Oath

- FREE ADVICE.......for what its worth!

- LAUGHTER.....is the best medicine

- Physicians Pet Peeves

- PHOTO ALBUM - its not all work!

- Cape Town, South Africa

- Tribute page

- The 100 Club

- Free Wi-Fi

Heart Health

February is Heart Month

There's no better time to learn how to protect yourself against heart disease. It's the leading cause of death of both men and women in the U.S. and many adults have at least one risk factor for heart disease. Knowing what you can do to keep your heart healthy and strong is critical to your future health and well-being.

Coronary Artery Disease

For a more comprehensive review of CAD clickon this website

Warning symptoms of a possible heart attack:

Do not attempt to drive yourself to the hospital and nor should you ask a family member to drive you. Minutes count and the emergency medical technicians will not only get you started on treatment in your home, but will also get you seen immediately on arrival in the ER.

Heart attack patients who do not have chest pains are three times as likely to die, probably because doctors do not recognize their symptoms.

Heart Attack Overview

A heart attack is when low blood flow causes the heart to starve for oxygen. Heart muscle dies or becomes permanently damaged. Your doctor calls this a myocardial infarction.

Alternative Names

Myocardial infarction; MI; Acute MI

Causes

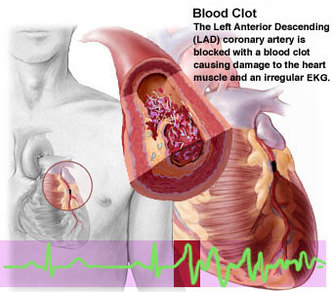

Most heart attacks are caused by a blood clot that blocks one of the coronary arteries. The coronary arteries bring blood and oxygen to the heart. If the blood flow is blocked, the heart starves for oxygen and heart cells die.

A clot most often forms in a coronary artery that has become narrow because of the build-up of a substance called plaque along the artery walls. (See: atherosclerosis) Sometimes, the plaque cracks and triggers a blood clot to form.

Occasionally, sudden overwhelming stress can trigger a heart attack.

It is difficult to estimate exactly how common heart attacks are because as many as 200,000 to 300,000 people in the United States die each year before medical help is sought. It is estimated that approximately 1 million patients visit the hospital each year with a heart attack. About 1 out of every 5 deaths are due to a heart attack.

Risk factors for heart attack and coronary artery disease include:

Symptoms

Chest pain is a major symptom of heart attack. However, some people may have little or no chest pain, especially the elderly and those with diabetes. This is called a silent heart attack.

The pain may be felt in only one part of the body or move from your chest to your arms, shoulder, neck, teeth, jaw, belly area, or back.

The pain can be severe or mild. It can feel like:

Other symptoms of a heart attack include:

Signs and Tests »

A heart attack is a medical emergency. If you have symptoms of a heart attack, seek immediate medical help.

The health care provider will perform a physical exam and listen to your chest using a stethoscope. The doctor may hear abnormal sounds in your lungs (called crackles), a heart murmur, or other abnormal sounds.

You may have a rapid pulse. Blood pressure may be normal, high, or low.

Tests to look at your heart include:

Treatment

If you had a heart attack, you will need to stay in the hospital, possibly in the intensive care unit (ICU). You will be hooked up to an ECG machine, so the health care team can look at how your heart is beating. Life-threatening arrhythmias (irregular heart beats) are the leading cause of death in the first few hours of a heart attack.

The health care team will give you oxygen, even if your blood oxygen levels are normal. This is done so that your body tissues have easy access to oxygen, so your heart doesn't have to work as hard.

An intravenous line (IV) will be placed into one of your veins. Medicines and fluids pass through this IV. You may need a tube inserted into your bladder (urinary catheter) so that doctors can see how much fluid your body gets rid of.

THROMBOLYTIC THERAPY

Depending on the results of the ECG, certain patients may be given blood thinners within 12 hours of when they first felt the chest pain. This is called thrombolytic therapy. The medicine is first given through an IV. Blood thinners taken by mouth may be prescribed later to prevent clots from forming.

Thrombolytic therapy is not appropriate for people who have:

Many different medicines are used to treat and prevent heart attacks.

A procedure called angioplasty may be needed to open blocked coronary arteries. This procedure may be used instead of thrombolytic therapy. Angioplasty with stenting can be a life-saving procedure if you are having a heart attack. However, for persons with coronary heart disease, recent studies show that medicine and angioplasty with stenting have equal benefits. Angioplasty with stenting does not help you live longer, but it can reduce angina or other symptoms of coronary artery disease.

Some people may need emergency coronary artery bypass surgery (CABG).

Expectations (prognosis)

How well you do after a heart attack depends on the amount and location of damaged tissue. Your outcome is worse if the heart attack caused damage to the signaling system that tells the heart to contract.

About a third of heart attacks are deadly. If you live 2 hours after an attack, you are likely to survive, but you may have complications. Those who do not have complications may fully recover.

Usually a person who has had a heart attack can slowly go back to normal activities, including sexual activity.

Complications

Prevention

To prevent a heart attack:

After a heart attack, you will need regular follow-up care to reduce the risk of having a second heart attack. Often, a cardiac rehabilitation program is recommended to help you gradually return to a normal lifestyle. Always follow the exercise, diet, and medication plan prescribed.

A Visceral Fear: Heart Attacks That Strike Out of the Blue

By Melinda Beck WSJ Article : June 20, 2008

My father was planning a trip to Europe one summer afternoon when he went to the bathroom and didn't return. My mother found him dead of a heart attack on the bathroom floor. My husband's grandfather's heart gave out as he was walking down the sidewalk in New York.

Everybody knows somebody who has had a sudden, fatal heart attack, and it's many people's secret fear. More than 300,000 Americans die of heart disease without making it to the hospital each year; most of them from sudden cardiac arrest, according to the American Heart Association. In about half of those cases, the heart attack itself is the first symptom.

Deaths from cardiovascular disease in general have dropped dramatically in recent years, but it is still the No. 1 killer of men and women in the U.S. -- claiming more lives than cancer, chronic respiratory diseases, accidents and diabetes combined.

That's in part because, for all the advances doctors have made in understanding risk factors, lowering cholesterol with statins and propping open narrowed arteries with stents, most heart attacks are caused when tiny bits of plaque break loose and burst like popcorn kernels, forming clots that block arteries. That prevents blood from reaching areas of heart muscle, which start to die. It's hard to predict when that might happen -- which is why people who never knew they had heart disease, and people who thought it was under control, still have sudden heart attacks.

WHEN TO CALL 911

• Common heart-attack signs in men:

-Pressure, fullness in chest that may come and go

-Discomfort in arms, neck, back, jaw

-Shortness of breath

-Lightheadedness

• Women more likely to have:

-Sudden sweating

-Shortness of breath

-Nausea/vomiting

-Back or jaw pain

Source: American Heart Association

"We have terrific therapies that were unimaginable 25 or 30 years ago," says E. Scott Monrad, director of the cardiac catheterization lab at Montefiore Medical Center in Bronx, N.Y. "But one of the biggest risks is dying before you even get to see a doctor."

Last weekend, scores of commentators on health and political blogs offered theories about what might have been done to save NBC's Tim Russert, who died of a sudden heart attack at work Friday. Few details were released, other than that the much-loved "Meet the Press" moderator was being treated for asymptomatic coronary artery disease, had diabetes and an enlarged heart, and had a stress test in April.

Many blog-posters argued that Mr. Russert should have had an angiogram -- an invasive diagnostic test in which the coronary arteries are injected with dye and X-rayed to spot blockages. But even if he had had the procedure an hour before the attack, doctors might not have seen anything to be alarmed about. More than two-thirds of heart attacks occur in arteries that are less than 50% narrowed by plaque buildup -- and those are often too small to show up on an angiogram or cause much chest pain.

Similarly, the stress test Mr. Russert had is better suited to detecting significantly narrowed arteries than the small, soft unstable kind of plaque that often causes fatal blood clots.

Indeed, about a third of people who have heart attacks don't have the usual risk factors, such as family history of heart disease, abdominal fat, high blood pressure or high cholesterol.

RISK FACTORS

The symptoms that make up "metabolic syndrome" put people at high risk for heart attack, stroke and diabetes. (Smoking and heavy alcohol consumption also raise the risk.)

• Waist more than 40 inches for men; 35 inches for women

• Blood pressure over 130/85mmHg

• Fasting glucose over 110 mg/dl

• Triglycerides over 150 mg/dl

• LDL cholesterol over 100 mg/dl

• HDL cholesterol under 40 mg/dl

Source: American Medical Association

"Time and again we see examples of unexpected cardiac disease in people who didn't know they had it," says Prediman K. Shah, director of cardiology at Cedars-Sinai Heart Institute in Los Angeles, one of many experts who think wider use of coronary calcium CT scans could help spot more people at risk of soft-plaque blockages. The noninvasive procedure takes about 15 minutes and costs a few hundred dollars. But few insurers cover it because there is scant evidence that treating people on that basis saves lives.

At a minimum, seeing a picture of the calcium lining their arteries can be a wake-up call for patients to take their coronary-artery disease seriously and to be diligent in taking medication, exercising and making other healthy lifestyle changes.

Mr. Russert's family and physicians haven't disclosed how his coronary artery disease was diagnosed, or how he was being treated. NBC colleagues said the 58-year-old journalist had been working to control his condition with exercise and diet, though his weight was an ongoing struggle. He had also returned from a family trip to Italy the day before, following a grueling -- but exhilarating -- political primary season.

Not all heart attacks are fatal. Most of the 1.2 million Americans who had one last year survived. If the area of oxygen-starved heart muscle is small, or in the right ventricle, the heart can often keep pumping, allowing the patient to make it to a hospital, where doctors can break up the blockage with a clot-dissolving drug or catheterization. The situation becomes rapidly fatal if the heart starts beating wildly, and ineffectively, as it struggles to keep pumping. Unless it is jolted back into a normal rhythm within a few minutes, the patient's brain will starve for oxygen and shut down.

Some patients with enlarged hearts like Mr. Russert's are candidates for internal defibrillators that can continuously monitor heart rhythm and keep it regular automatically. Vice President Dick Cheney, who has survived four heart attacks, has one.

Many airports, shopping malls, schools and offices have portable Automatic External Defibrillators, or AEDs, on hand as well. They're designed to automatically assess a victim's heart rhythm and administer an electrical jolt as needed. The NBC office reportedly didn't have an AED, but an intern performed cardiopulmonary resuscitation on Mr. Russert until paramedics arrived with a defibrillator.

"The earlier CPR is started, the higher the rate of success," says Dr. Monrad, who says he has had several cases in which vigorous CPR in the field bought precious time and saved a life. On average, however, only a small percentage of people in full cardiac arrests are successfully revived.

More widespread use of AEDs and wider CPR training could save some future victims' lives. Some bloggers suggested that more-aggressive treatment of Mr. Russert's artery disease might have bought him some time, though most experts declined to speculate.

But stents, angioplasty and bypass surgery are only stop-gap measures that don't do anything to halt the progress of the underlying disease. "Everytime I do a procedure on a patient, the family comes up and says, 'Now we don't have to worry anymore,' but that's the wrong message," says Dr. Monrad. "Physicians have to be tough on the standards we set for patients, and patients have to be tougher about the kind of lifestyle choices they make."

The heart has many mysteries that scientists are still unraveling, such as what causes those killer bits of plaque to rupture, the role of inflammation, the complex interplay of diet, vitamins and amino acids like homocysteine. Even the size of cholesterol particles is under scrutiny. "The more small LDL particles you have, the higher your risk of heart disease," says Larry McCleary, a former pediatric neurosurgeon at Denver Children's Hospital who had a heart attack while on rounds at age 46, and has since lost weight, reduced his blood pressure and triglycerides, and exercises daily.

"It's important that each person take responsibility for taking care of themselves," says Edmund Herrold, a clinical cardiologist in New York City and professor at Weill Cornell Medical College. "Get a regular checkup. Watch your weight and your blood pressure and your cholesterol and if you have diabetes, keep that under control. Exercise. Take an aspirin every day. Eliminate meat. There's no guarantee, but you can dramatically lower the risk of a cardiac event if you pay attention to these issues."

The Guide to Beating a Heart Attack

First Line of Defense Is Lowering Risk, Even When Genetics Isn't on Your Side

Ron Wislow : WSJ : April 16, 2012

Here's the good news: Heart disease and its consequences are largely preventable. The bad news is that nearly one million Americans will suffer a heart attack this year.

Still, cardiovascular disease remains the leading killer of both men and women. Doctors worry that the steady progress from an intense public-health campaign beginning in the 1960s is in jeopardy thanks to the obesity epidemic and rising prevalence of diabetes. Only a relative handful of people are fully compliant with recommendations for diet, exercise and other personal habits well proven to help keep hearts healthy.

Particularly troubling are increasingly common reports of heart attacks among younger people, even those in their 20s and 30s, says Donald M. Lloyd-Jones, a cardiologist and chief of preventive medicine at Northwestern University's Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago.

There is a lot a person can do to help prevent a heart attack. One international study found that about 90% of the risk associated with such factors as high cholesterol and blood pressure, physical activity, smoking and diet, are within a person's ability to control. The study, called Interheart, compared 15,000 people from every continent who suffered a heart attack with a similar number of relatives or close associates who didn't.

While genetics plays a role in up to one-half of heart attacks, "You can trump an awful lot of your genetics with choices you make and with medicines if you need them," says Dr. Lloyd-Jones.

The Basics

Knowing your cholesterol and blood pressure numbers is as fundamental to heart health as knowing the alphabet is to reading. Yet surveys show about one third of people with problem levels don't know it. For most people, optimal LDL, or bad cholesterol, is under 100; HDL, or good cholesterol, is over 60; and blood pressure is less than 120/80.

Tests for such readings aren't only important to understanding your risk, doctors say, but to measuring your progress toward reducing it. Healthy diet and exercise habits comprise the first line of offense toward improving or managing these numbers and toward controlling weight and blood-sugar levels as well. Drugs to lower cholesterol and blood pressure are effective weapons when needed.

Quitting smoking also yields big benefits. Within a year, a former smoker's heart-attack risk is reduced by 50%.

Guidelines urge three hours a week of brisk exercise to maintain heart health, but many people who can't find the time to work up a sweat for 30 minutes most days don't bother. "It's the all or nothing phenomenon," says Martha Grogan, a cardiologist at Mayo Clinic.

But how about 10 minutes a day? While the 30-minute target is associated with a 70% reduction in heart-attack risk over a year, Mayo researchers analyzed the data and noticed that a brisk 10-minute walk a day results in a nearly 50% reduction compared with people who get hardly any exercise.

The actual benefit varies depending on age, gender, weight and base line physical condition, and those at highest risk have the most to gain. "If you can do more, then you're better off," says Dr. Grogan. "But small amounts of exercise aren't nothing." Still, cardiologists say a 30-minute daily workout should be the goal.

For people who sit most of the day, theirrisk of heart attack is about the same as smoking—Martha Grogan,cardiologist at the Mayo Clinic

Keep Moving

Even regular exercise isn't sufficient if you're confined to a desk or a couch for the rest of the day.

A study from Australian researchers published two years ago found that spending more than four hours a day in front of a computer or television was associated with a doubling of serious heart problems, even among people who exercised regularly. The researchers tracked 4,512 men and women, mostly in their late 50s, for four years and compared them against those spending less than two hours in front a screen.

Prolonged sitting was associated with higher levels of inflammatory markers in the blood, higher body weight and lower levels of HDL, or good cholesterol, indicating that sedentary behavior has its own bad biology apart from whether you're physically active.

Cardiovascular disease remains the leading killer of both men and women.

"For people who sit most of the day, their risk of a heart attack is about the same as smoking," Dr. Grogan says.

Possible remedies: getting up from your desk every 30 minutes or even working at your computer while standing up. Take a walk to talk to a colleague instead of sending an email. Or, "when the 2:30 p.m. doldrums hit," says Dr. Lloyd-Jones, "rather than going for a Snickers, go for a 10-minute walk. The benefit starts to occur as soon as you get up."

Build steps into your day. Take the stairs instead of the escalator; park at the edge of the parking lot at work or the mall instead of jockeying for a space near the entrance.

Don't Worry, Be Happy

In their new heart-health book "Heart 411," Cleveland Clinic doctors Marc Gillinov and Steven Nissen describe a study by Wayne State University researchers who rated the smiles of 230 baseball players who played before 1950 based on pictures in the Baseball Register. Then they looked to see how long the players lived on average: No smile, age 73; partial smile, 75. Those with a full smile made it to 80.

While not the most robust science, it is consistent with other research linking emotional health to lower risk of cardiovascular disease. In contrast, depression, anger and hostility have a deleterious effect. A Duke University study of 255 doctors from several years ago found that 14% of those rated above average for hostility based on a personality test had died 25 years later—most from heart disease—compared with 2% of those who tested below the average.

Eat your veggies

Complying with nutritional guidelines is the toughest challenge for most Americans, data from the American Heart Association indicate. Shopping the perimeter aisles of the grocery store is one possible remedy. It's where fresh produce and other unprocessed foods are typically found—generally considered more heart-healthy than the calorie-dense, salt-heavy foods found principally in the interior sections of the store, says Amparo Villablanca, a cardiologist at University of California, Davis.

She advises patients to "not put mud in your engines. You have to get people to think of their bodies as a finely tuned machine."

Adds Sharonne Hayes, a Mayo Clinic cardiologist: "Don't skip breakfast." If you don't eat in the morning, you trigger metabolic processes "that lead you to eat more during the day."

Get a Good Night's Sleep

Sleep's role in protecting the heart is underestimated, says Mayo's Dr. Grogan. "If you get one less hour of sleep than you need each night, you've basically pulled an all-nighter a week," she says. Chronic sleep deprivation can lead to high blood pressure, weight gain and increase your risk of diabetes, she says.

If You're Stricken, Minutes Matter, Yet Many Ignore Signs, Delay Treatment

Melinda Beck : WSJ : April 9, 2012

The advice sounds very simple. The best way to survive a heart attack is:

1. Recognize the symptoms.

2. Call 911.

3. Chew an aspirin while waiting for emergency personnel to arrive.

But every year, 133,000 Americans die of heart attacks, and another 300,000 die of sudden cardiac arrest—largely because they didn't get help in time.

Of all the efforts to combat cardiovascular disease in the U.S., "this is our Achilles' heel, and it's the area where we've made the least progress," says Ralph Brindis, a past president of the American College of Cardiology.

Heart-attack sufferers fare best when they get to the hospital within one hour after symptoms start. But on average, it takes two to four hours for patients to arrive, and some wait days before seeking medical care. Reasons range from confusion to denial to fear of looking silly if they aren't having a health crisis after all.

Heart attacks, officially called myocardial infarctions, typically occur when a blockage forms in one of the coronary arteries, depriving part of the heart muscle of blood. Doctors can open the blockage with drugs or cardiac catheterization—but the more time that takes, the more heart muscle dies. "Time is muscle," as cardiologists say. Even if the initial heart attack isn't fatal, damaged heart muscle can lead to congestive heart failure—one of the reasons why 19% of men and 26% of women over age 45 die within one year of having their first heart attack, according to the American Heart Association.

Severe damage is bad enough. It can disrupt the heart's rhythm and lead to cardiac arrest, where the heart stops pumping blood. At that point, the victim has only a few minutes to live unless bystanders or paramedics restart the heart with a defibrillator or perform CPR.

Cardiac arrest often happens with no warning. Only 7.6% of people who suffer one outside of a hospital survive long enough to be discharged, a rate that hasn't changed much in 30 years, according to a 2010 University of Michigan study.

Recognize the Symptoms

With most heart attacks, victims do have some warning—but the symptoms can be confusing. The stereotypical "Hollywood heart attack," clutching the chest in agony, is only one scenario. The feeling in the chest may be more squeezing, tightening or heavy pressure. It may radiate down the left arm or up to the jaw or around the back between the shoulder blades, particularly in women. One study found that 71% of women experience flulike symptoms with no chest pain at all.

Both men and women may have indigestion, nausea, lightheadedness, profuse sweating, shortness of breath with little exertion and overwhelming fatigue.

"People whose heart muscle is shutting down often feel really tired, so they lie down and take a nap," says Dr. Alonzo. "That's not a good idea. They may not wake up."

Dr. Alonzo, who has studied behavior during heart attacks for 40 years, notes that people delay getting help longer when they're at home than in the office. At home, "you have more resources to use—you have your bed to lay down on, your favorite drink or your favorite comfort food. If you're at work, you tend to get out of there much faster, " says Dr. Alonzo, who titled one talk on heart-attack delays "Who's Going to Feed the Canary?"

"Thank God we have spouses," says Dr. Brindis. "I can't tell you how often, if it was left up to the patient, they never would have sought care." He says one cardiologist colleague thought he was having a heart attack, and ran up and down the stairs of his building to give himself a stress test. Turned out he was.

Some people call their physicians to discuss their symptoms—but experts say that only wastes more time. Even if you merely suspect you might be suffering from a heart attack, seek help as soon as possible. "It takes skilled physicians and nurses and lab technicians and often some kind of imaging tests to actually diagnose a heart attack, so there's no way you can diagnose it yourself at home," says cardiologist Janet Wright, executive director of the Department of Health and Human Service's Million Hearts campaign, which aims to prevent one million heart attacks and strokes in the next five years.

Call 911

Once they do decide to go the emergency room, only about 50% of heart-attack sufferers call 911 and arrive by ambulance, studies show. In the Yale Heart Study to date, 41% of respondents said someone else drove them, and 13% drove themselves.

According to Dr. Alonzo, some said they were worried about the cost of ambulance; others said they would be embarrassed to have neighbors see them taken away on a gurney.

But calling 911 has many important advantages. Emergency-medical technicians can perform CPR or use a defibrillator in case of cardiac arrest. Some can start intravenous fluids and give medications. EMTs can also administer electrocardiograms to gauge the extent of heart damage and notify the hospital to have the appropriate equipment standing by. That can significantly cut "door-to-balloon time"—the time between when a heart-attack sufferer first arrives and his or her blocked artery is opened.

"Patients who are brought in my ambulance are treated differently by the medical team," says Dr. Brindis. If you do go to the hospital on your own, be sure you announce, "I think I'm having a heart attack!" for immediate attention.

Take an Aspirin

It does make sense to take one adult-strength aspirin, which prevents blood clots and may help keep an artery partially open. Chewing it will get it into your bloodstream quicker than swallowing it. The brand doesn't matter, as long as it's uncoated. Tylenol, Advil and other pain-relievers that aren't aspirin-based won't have the same effect.

If you have a history of heart disease or are at high risk for cardiac arrest, it may make sense to buy a home defibrillator, which costs about $1,200. "Cardiac arrest is what will kill you," says Douglas Zipes, another past president of the American College of Cardiology. "Having it in your home is a very cheap insurance policy."

The Right Recovery

Sadly, surviving a heart attack doesn't end with getting to the hospital quickly.

Cardiac-rehabilitation programs that offer exercise and diet plans along with education and support groups can help lower that risk. Many hospitals offer them, but they're under-used. In one study, only 14% of heart-attack survivors on Medicare enrolled.

PERSONAL STORIES: Vignettes from heart-attack patients.

Her Symptoms Overlooked

Women generally take longer than men to seek help when they have heart-attack symptoms--partly because they don't want to make trouble, partly because they have too much else to do and partly because some doctors brush them off when they do.

Carolyn Thomas of Victoria, Canada, was 58, experienced all three in 2008 when she had the classic symptoms—"crushing pain in the chest, nausea, sweating, pain down the left arm"—while out for her usual morning walk.

"I leaned against a tree, thinking, 'This better not be a heart attack because I don't have time for one,' " recalls Ms. Thomas, who worked in hospital communications at the time.

She went to the emergency room anyway, but was told her tests were normal. "The doctor said, 'You're in the right demographic for acid-reflux. Go see your family doctor," she says. "I was so embarrassed. I left like I had wasted five hours of their time."

The pain returned, then subsided, on and off for days. Ms. Thomas, made an appointment to see her doctor, but didn't think it was urgent. "I knew it couldn't be my heart, because this guy with an MD just told me it wasn't," she says.

She went on a long-planned visit to see her mother in Ottawa. But on the way back, the chest pain got worse. She had two more attacks in the airport and two more during the five-hour flight home. She didn't notify the flight attendant "because I didn't want to make a fuss," she says.

When she landed in Vancouver, after midnight, she was too weak to walk and barely made her connecting flight to Victoria. "I kept thinking, if I can just get home, I'll be all right," she says. An airport staffer with a wheelchair helped her to her car "with me apologizing all the while," she says. It took her 20 minutes to gather the strength to drive home.

At the hospital the next morning, doctors said she had a 99% blockage in her left anterior descending artery—known as "the widowmaker," since blockages there are so often fatal.

"Notice they don't call it 'the widower-maker,' " says Ms. Thomas, who learned that men with the symptoms she had on her first visit would typically be kept for observation far longer.

Since then, Ms. Thomas attended a leadership program for women heart-attack survivors at the Mayo Clinic and started a blog, myheartsisters.org, to help educate women about heart disease.

Among the research on her site: a study in the New England Journal of Medicine showing that women are seven times more likely than men to be misdiagnosed in mid-heart attack and sent home from the hospital, and a 2005 poll from the American Heart Association that found that only 8% of family-care physicians and 17% of cardiologists were aware that more women have died from heart disease than men every year since 1984.

Women do bear some of the responsibility for delays in care themselves. "Women think, 'Yes, we'll call the doctor after we pick up the kids and finish that report and put the casserole in the oven,' " says Ms. Thomas.

But she urges others to pay more attention to their bodies and their instincts. "You know when something is not right. That's what I didn't pay attention to," says Ms. Thomas. "The acid test is, 'If somebody that you love is experiencing these symptoms, what would you do?' "

Public-health officials also say that physicians need to be more aware of women's heart issues, and watch their bedside manner with false alarms.

Says Janet Wright, executive director of the Department of Health and Human Service's Million Heart campaign: "We need to work on medical personnel to say something like, 'You are not having a heart attack, but we're so glad you came in, and here are five things you can do to prevent one in the future.' "

Attack Wiped His Memory Clean

Fewer than 8% of people who suffer sudden cardiac arrest outside of a hospital live long enough to be discharged. James Wilson was one of the lucky ones.

In 1999, Mr. Wilson, then a 41-year old lawyer, was a Naval Reserve commander on active duty in Paris. He and his wife were on a bus heading to Monet's Garden when he said to her, "I don't feel good," and collapsed.

The bus driver gave him mouth-to-mouth resuscitation and restored his breathing while other passengers kept his heart beating with cardiopulmonary resuscitation until emergency-medical technicians arrived and shocked his heart with a defibrillator—twice—before his normal heartbeat returned.

Still, Mr. Wilson's brain had been deprived of oxygen for several minutes. He went into a coma that lasted three days. Then he was taken to an Air Force hospital in Germany, and medevac'd to Walter Reed Army Medical Center in Washington D.C..

Doctors there couldn't determine what caused Mr. Wilson's heart to stop beating, a common problem with sudden cardiac arrest. They suspected an electrical disturbance and implanted an internal defibrillator in his chest in case his heart stopped beating again.

The bigger problem, Mr. Wilson says, was that the lack of oxygen "caused my frontal lobe to be 'wiped clean,' as the doctors described it. I had more work to do getting my brain functioning again than anything I had to do with my heart." He had no memory of the event, the hospitalization or even being in Paris. He called a law firm he hadn't worked at for two years and asked for his messages.

Doctors at Walter Reed put his chances of returning to his work as a lawyer at 1%, but he beat the odds again. After four months of therapy to restore memory functions, he was cleared to practice law again. Even today, he still gets "small blips of memory, but I cannot be sure that it is legitimately my memory of being in Paris or something that comes from a movie or a magazine."

What caused Mr. Wilson's heart to stop beating is still a mystery. So far, his internal defibrillator hasn't been needed, though he does run 10K races to stay fit. His father suffered something similar years earlier. "I just hope that neither my son nor my daughter get the chance to see if it will happen to them," he says.

After Jog, Healthy 46-Year-Old Is Stricken

On March 8, Lisa Schmidtfrerick-Miller woke up, got dressed and jogged the three miles scheduled for her half-marathon training program. A licensed massage therapist, she had only one appointment and spent the rest of the day at her desk. On her way home, she realized that she was "just not feeling right." She felt light-headed, with pressure in her upper chest that extended across her collarbone, into both arms and radiated to her upper jaw.

They were classic symptoms of a heart attack—but Ms. Miller was an active, healthy 46-year old, with no risk factors for heart disease.

She knew enough from her work in public health to take an aspirin and go to the local hospital in Jamestown, N.Y., "just to get checked out." She was transported to a fully equipped cardiac-care center, where she was diagnosed with Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection (SCAD), a condition in which the inner lining of a coronary artery separates and folds over inside the artery. "The torn part blocks blood flow and wham-o, a heart attack," as Ms. Miller explains.

SCAD was once thought to be a rare condition, but it is increasingly being diagnosed in otherwise healthy adults their 30s and 40s. About 70% of the recent cases are in women, about one-third of them who were pregnant or had recently given birth.

Ms. Miller's SCAD was in the left anterior descending artery—the so-called widowmaker. But doctors were able to restore blood flow with cardiac catheterization. They think that with a variety of medications, her artery should be able to heal on its own.

What's frustrating—and frightening—is that it's not known whether people who have had one episode of SCAD are at high risk for another, or what they can do to reduce that risk. Ms. Miller has no history of coronary heart disease, never smoked, maintains a normal weight, has low blood pressure and very healthy cholesterol numbers.

Still, she had started a cardiac rehabilitation program—and joined a group of other SCAD survivors who are determined to further research and awareness of SCAD.

He Relented and Called an Ambulance

Bruce Smith was out for a walk around midnight on Feb. 26 when he felt "like a grenade had exploded in my chest."

He knew he was at risk for heart problems. "I'm a fat guy, and over the years, I've become more sedentary," says the 62-year-old journalist in Yelm, Wash., though he had been trying to walk more and eat less lately.

But what went flashed through his mind was: "What is this? What can I do about it? I don't have any money or any insurance."

He decided to go to sleep and woke up thinking, "Thank God, I dodged that bullet." But an hour later, the pain returned, worse than the night before. He took some aspirin and sat down and the pain got even worse, radiating across his chest, down his arm up into his jaw and face. "It was even ringing my cavities," he says.

Mr. Smith called his neighbor, Dave. Twice, but his line was busy. So he resigned himself to calling 911. Soon, he heard a siren getting louder and closer.

One firefighter rushed in with a blood pressure monitor and an EKG machine. Another helped attach pads and monitoring wires. With his blood pressure soaring to 230/169, the EMTs carried him out on a thin metal wheelchair, transferred him to a gurney and secured him in the back of the ambulance, where they squirted nitroglycerine under his tongue and got an IV flowing.

They also told him not to worry about not having money or insurance.

At Good Samaritan Hospital in Puyallup, Wash., Mr. Smith learned that he had a 95% blockage in his rear circumflex coronary artery and was whisked to the cardiac catheterization lab for angioplasty.

He asked a technician, "Would it be fair to say I've had a heart attack?"

"Dude, it could have been fatal," the tech replied.

It was only later that night, after hours of surgery and recovery, when a nurse was asking about how he lived, that he had an epiphany, Mr. Smith says. One revelation was that he needed more love in his life. Another was that "all the things I thought I was doing for myself weren't enough. It was humbling."

Now in his seventh week of cardiac rehab, Mr. Smith says he makes a point to do something physical for at least an hour every day. He's lost 10 pounds so far and is determined to return to his high school weight. He also enjoys kibitzing with fellow members of his cardiac-rehab group while pedaling bicycles or on the treadmill. "Everybody's in the same boat. Nobody feels good," he says.

As for his medical bills, they aren't all settled yet, but Good Sam hospital is covering the cost of nursing, ER, the cardiac care and eight to 10 weeks of rehab as charity care. He's gotten discounts on medications and a local tax levy covers ambulance costs when patients can't pay. Friends and neighbors and family members are also helping with food, gas and rides to doctor visits and rehab. "God bless you all," he says.

Corrections & Amplifications

A 2005 poll from the American Heart Association that found that only 8% of family-care physicians and 17% of cardiologists were aware that more women have died from heart disease than men every year since 1984. An earlier version of the online profile of Carolyn Thomas stated that 8% of family-care physicians and 17% of cardiologists were unaware that more women have died from the disease.

More Is Not Necessary Better In Coronary Care

By Jane E. Brody : NY Times Article : January 6, 2009

Ira’s story is a classic example of invasive cardiology run amok.

Ira, of Hewlett, N.Y., was 53 when he had an exercise stress test as part of an insurance policy application. Though he lasted the full 12 minutes on the treadmill with no chest pain, an abnormality on the EKG led to an angiogram, which prompted the cardiologist to suggest that a coronary artery narrowed by atherosclerosis be widened by balloon angioplasty, with a wire-mesh tube called a stent inserted to keep the artery open.

The goal, he was told, was to prevent a clot from blocking the artery and causing a heart attack or sudden cardiac death.

Wanting to avoid an invasive procedure, Ira decided to pursue a less drastic course of dieting, weight loss and cholesterol-lowering medication. But three years later, the specter of a stent arose again. An abnormal reading on a presurgical EKG led to another angiogram, which indicated that the original narrowing had worsened. Cowed by the stature of the cardiologist, Ira finally agreed to have not one but three coronary arteries treated with angioplasty and drug-coated stents, making him one of about a million Americans who last year underwent angioplasties, most of whom had stents inserted.

Being Treated While Healthy For patients in the throes of a heart attack and those with crippling chest pain from even minor exertion, angioplasty and stents can be lifesaving, says Dr. Michael Ozner, a Miami cardiologist and the author of “The Great American Heart Hoax” (Benbella Books, $24.95). But, Dr. Ozner said in an interview, such “unstable” patients represent only a minority of those undergoing these costly and sometimes risky procedures.

Most stent patients are healthy like Ira, who was experiencing no chest pain or cardiac symptoms of any sort. Yet Ira was afraid not to follow the doctor’s advice, despite the fact that no study has shown that these procedures in otherwise healthy patients can reduce the risk of heart attacks, crippling angina or sudden cardiac death. “We’ve extended the indications for surgical angioplasty and stent placement without any data to support the procedures in the vast majority of patients — stable patients with blockages in their arteries,” Dr. Ozner said.

What the studies do show, Dr. Ozner said, is that putting stents in such patients is no more protective than following a heart-healthy lifestyle and taking medication and, if necessary, nutritional supplements to reduce cardiac risk. The studies have also shown that stents sometimes make matters worse by increasing the chance that a dangerous clot will form in a coronary artery, as noted in 2006 by an advisory panel to the Food and Drug Administration.

Dr. Ozner, medical director of the Cardiovascular Prevention Institute of South Florida, is one of many prevention-oriented cardiologists vocal about the overuse of “interventional cardiology,” a specialty involving invasive coronary treatments that have become lucrative for the hospitals and doctors who perform them.

Even some interventional cardiologists have expressed concern about the many patients without symptoms who are treated surgically. “The only justification for these procedures is to prolong life or improve the quality of life,” said Dr. David L. Brown, an interventional cardiologist and chief of cardiology at Stony Brook University Medical Center, “and there are plenty of patients undergoing them who fit into neither category.”

Mistaken Assumptions

The treatments — coronary artery bypass surgery, angioplasty and the placement of drug-coated stents — cost about $60 billion a year in the United States. Though they are not known to prevent heart attacks or coronary mortality in most patients, they are covered by insurance. Counseling patients about diet, exercise and stress management — which is relatively inexpensive and has been proved to be life-extending — is rarely reimbursed. In other words, procedure-oriented modern cardiology is pound wise and penny foolish. And in these economic times, it makes great sense to reconsider the approaches to reducing morbidity and mortality from the nation’s leading killer.

Most people mistakenly think of coronary artery disease as a plumbing problem. Influenced by genetics, diet, diabetes, hypertension, smoking and other factors, major arteries through which oxygen-rich blood flows to the heart gradually become narrowed by deposits of cholesterol-rich plaques until blood can no longer pass through, resulting in a heart attack.

In coronary bypass surgery, a blood vessel taken from elsewhere in the body is reattached to a clogged coronary artery to bypass the narrowed part.

However, as Dr. Ozner points out in his book, “three major studies performed in the late 1970s and early 1980s clearly proved that for the majority of patients, bypass surgery is no more effective than conservative medical treatment.” The exceptions — patients whose health and lives could be saved — were those with advanced disease of the left main coronary artery and those with severe crippling, or unstable, angina.

Bypass surgery does relieve the pain of angina, though recent studies suggest this may happen because pain receptors around the heart are destroyed during surgery.

“The studies on angioplasty delivered even worse news,” Dr. Ozner wrote. “Unless the patient was in the midst of a heart attack, the opening of a blocked coronary artery with a balloon catheter resulted in a worse outcome compared to management through medication.” In fact, one trial, published in 2003 in The Journal of the American College of Cardiology, found that balloon angioplasty, which flattens plaque against arterial walls, actually raised the risk of a heart attack or death.

Stents were designed to keep the flattened plaque in place. But studies of stable patients found no greater protection against heart attacks from stents than from treatments like making lifestyle changes and taking drugs to lower cholesterol and blood pressure.

A Small Culprit

A new understanding of how most heart attacks occur suggests why these procedures have not lived up to their promise. According to current evidence, most heart attacks do not occur because an artery is closed by a large plaque. Rather, a relatively small, unstable plaque ruptures and attracts inflammatory cells and coagulating agents, leading to an artery-blocking clot.

In most Americans middle age and older, small plaques are ubiquitous in coronary arteries and there is no surgical way to treat them all.

“Interventional cardiology is doing cosmetic surgery on the coronary arteries, making them look pretty, but it’s not treating the underlying biology of these arteries,” said Dr. Ozner, who received the 2008 American Heart Association Humanitarian Award. “If some of the billions spent on intervention were put into prevention, we’d have a much healthier America at a lower cost.”

Dr. Ozner advises patients who are told they need surgery to get an independent second opinion from a specialist.

New Thinking On How To Protect The Heart

By Jane E. Brody : NY Times Article : January 13, 2009

If last week’s column convinced you that surgery may not be the best way to avoid a heart attack or sudden cardiac death, the next step is finding out what can work as well or better to protect your heart.

Many measures are probably familiar: not smoking, controlling cholesterol and blood pressure, exercising regularly and staying at a healthy weight. But some newer suggestions may surprise you.

It is not that the old advice, like eating a low-fat diet or exercising vigorously, was bad advice; it was based on the best available evidence of the time and can still be very helpful. But as researchers unravel the biochemical reasons for most heart attacks, the advice for avoiding them is changing.

And, you’ll be happy to know, the new suggestions for both diet and exercise are less rigid. The food is tasty, easy to prepare and relatively inexpensive, and you don’t have to sweat for an hour a day to reap the benefits of exercise.

The well-established risk factors for heart disease remain intact: high cholesterol, high blood pressure, smoking, diabetes, abdominal obesity and sedentary living. But behind them a relatively new factor has emerged that may be even more important as a cause of heart attacks than, say, high blood levels of artery-damaging cholesterol.

That factor is C-reactive protein, or CRP, a blood-borne marker of inflammation that, along with coagulation factors, is now increasingly recognized as the driving force behind clots that block blood flow to the heart. Yet patients are rarely tested for CRP, even if they already have heart problems.

Even in people with normal cholesterol, if CRP is elevated, the risk of heart attack is too, said Dr. Michael Ozner, medical director of the Cardiovascular Prevention Institute of South Florida. He thinks that when people have their cholesterol checked, they should also be tested for high-sensitivity CRP.

Diet Revisited The new dietary advice is actually based on a rather old finding that predates the mantra to eat a low-fat diet. In the Seven Countries Study started in 1958 and first published in 1970, Dr. Ancel Keys of the University of Minnesota and co-authors found that heart disease was rare in the Mediterranean and Asian regions where vegetables, grains, fruits, beans and fish were the dietary mainstays. But in countries like Finland and the United States where plates were typically filled with red meat, cheese and other foods rich in saturated fats, heart disease and cardiac deaths were epidemic.

The finding resulted in the well-known advice to reduce dietary fat and especially saturated fats (those that are firm at room temperature), and to replace these harmful fats with unsaturated ones like vegetable oils. What was missed at the time and has now become increasingly apparent is that the heart-healthy Mediterranean diet is not really low in fat, but its main sources of fat — olive oil and oily fish as well as nuts, seeds and certain vegetables — help to prevent heart disease by improving cholesterol ratios and reducing inflammation.

Virtues Confirmed It was not until 1999 that the value of a traditional Mediterranean diet was confirmed, when the Lyon Diet Heart Study compared the effects of a Mediterranean-style diet with one that the American Heart Association recommended for patients who had survived a first heart attack.

The study found that within four years, the Mediterranean approach reduced the rates of heart disease recurrence and cardiac death by 50 to 70 percent when compared with the heart association diet.

Several subsequent studies have confirmed the virtues of the Mediterranean approach. For example, a study among more than 3,000 men and women in Greece, published in 2004 by Dr. Christina Chrysohoou of the University of Athens, found that adhering to a Mediterranean diet improved six markers of inflammation and coagulation, including CRP, white blood cell count and fibrinogen.

The same year Kim T. B. Knoops, a nutritionist at Wageningen University in the Netherlands, and co-authors published a study showing that among men and women ages 70 to 90, those who followed a Mediterranean diet and other healthful practices, like not smoking, had a 50 percent lower rate of deaths from heart disease and all causes.

“The Mediterranean diet is one people can stick to,” said Dr. Ozner, author of “The Miami Mediterranean Diet” and “The Great American Heart Hoax” (BenBella, 2008). “The food is delicious, and the ingredients can be found in any grocery store.

“You should make most of the food yourself,” Dr. Ozner added. “When the diet is stripped of lots of processed foods, you ratchet down inflammation. Among my patients, the compliance rate — those who adopt the diet and stick with it — is greater than 90 percent.”

Among foods that help to reduce the inflammatory marker CRP are cold-water fish like salmon, tuna and mackerel; flax seed; walnuts; and canola oil and margarine based on canola oil. Fish oil capsules are also effective. Dr. Ozner recommends cooking with canola oil and using more expensive and aromatic olive oil for salads.

Other aspects of the Mediterranean diet — vegetables, fruits and red wine (or purple grape juice) — are helpful as well. Their antioxidant properties help prevent the formation of artery-damaging LDL cholesterol.

Other Steps Several recent studies have linked periodontal disease to an increased risk of heart disease, most likely because gum disease causes low-grade chronic inflammation. So good dental hygiene, with regular periodontal cleanings, can help protect your heart as well as your teeth.

Reducing chronic stress is another important factor. The Interheart study, which examined the effects of stress in more than 27,000 people, found that stress more than doubled the risk of heart attacks.

Dr. Joel Okner, a cardiologist in Chicago, and Jeremy Clorfene, a cardiac psychologist, the authors of “The No Bull Book on Heart Disease” (Sterling, 2009), note that getting enough sleep improves the ability to manage stress.

Practicing the relaxation response once or twice a day by breathing deeply and rhythmically in a quiet place with eyes closed and muscles relaxed can help cool the hottest blood. Other techniques Dr. Ozner recommends include meditation, prayer, yoga, self-hypnosis, laughter, taking a midday nap, getting a dog or cat, taking up a hobby and exercising regularly.

He noted that in a 1996 study, just 15 minutes of exercise five days a week decreased the risk of cardiac death by 46 percent.

Even very brief bouts of exercise can be helpful. A British study published in the current American Journal of Clinical Nutrition found that accumulating short bouts — just three minutes each — of brisk walking for a total of 30 minutes a day improved several measures of cardiac risk as effectively as one continuous 30-minute session.

There is solid evidence that heart risk is lower for those who eat a “Mediterranean Diet” — heavy in fruits and vegetables, some olive oil, some nuts, some wine, plenty of fish, not much red meat. There’s also pretty good evidence that, independent of studies of the Mediterranean diet, a diet rich in vegetables and nuts may lower the risk of heart disease.

Eating a lot of trans fats (typically found in processed foods that contain partially hydrogenated oil) probably increases the risk of heart disease, the researchers found, as does a diet rich in foods that have a high glycemic index, such as sugary cereals and refined grains.

- It is essential that the patient should not smoke.

- Cholesterol levels should be aggressively lowered using a "statin" [eg simvastatin, pravastatin, atorvastatin, rosuvastatin]. The LDL goal should be <75.

- Hypertension should be controlled ideally with both a beta-blocker [eg metoprolol, atenolol, carvedilol] and an ACE inhibitor [eg lisinopril, ramipril, quinapril] with the goal of having a systolic blood pressure of <140 and a pulse rate of around 60 beats per minute.

- Diabetes should be tightly and consistently controlled. Hemoglobin A1c level should be <7%.

- Adult low dose aspirin [81mg] should be taken on a daily basis. In addition, clopidogrel (Plavix) 75mg a day may be prescribed for 9-12 months after stenting or bypass grafting.

- Nitroglycerin sublingual tablets should be available for use should any breakthrough angina occur.

- Try to stay in shape by walking on a daily basis and attempt to lose weight if you are overweight.

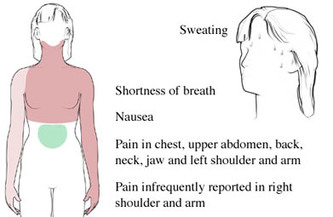

Warning symptoms of a possible heart attack:

- chest pressure or pain which can radiate up to the neck, jaw, down one or both arms and into the back, especially if associated with any of the following symptoms:

- sweating

- nausea or vomiting

- shortness of breath

Do not attempt to drive yourself to the hospital and nor should you ask a family member to drive you. Minutes count and the emergency medical technicians will not only get you started on treatment in your home, but will also get you seen immediately on arrival in the ER.

Heart attack patients who do not have chest pains are three times as likely to die, probably because doctors do not recognize their symptoms.

- An estimated 13 percent of patients without chest pain died in the hospital, compared to 4.3 percent of patients with chest pain, according to a study published in the journal Chest.

- The patients who died tended to be older women, the international team of researchers found.

- While the majority of people who have acute coronary syndromes, such as heart attacks and unstable angina, feel chest pain, some do not, but, instead, may experience atypical symptoms of fainting, shortness of breath, excessive sweating, or nausea and vomiting

- Patients without chest pain tended to be older women with diabetes, heart failure or high blood pressure. Patients who suffered chest pain were more likely to be smokers with clogged arteries

Heart Attack Overview

A heart attack is when low blood flow causes the heart to starve for oxygen. Heart muscle dies or becomes permanently damaged. Your doctor calls this a myocardial infarction.

Alternative Names

Myocardial infarction; MI; Acute MI

Causes

Most heart attacks are caused by a blood clot that blocks one of the coronary arteries. The coronary arteries bring blood and oxygen to the heart. If the blood flow is blocked, the heart starves for oxygen and heart cells die.

A clot most often forms in a coronary artery that has become narrow because of the build-up of a substance called plaque along the artery walls. (See: atherosclerosis) Sometimes, the plaque cracks and triggers a blood clot to form.

Occasionally, sudden overwhelming stress can trigger a heart attack.

It is difficult to estimate exactly how common heart attacks are because as many as 200,000 to 300,000 people in the United States die each year before medical help is sought. It is estimated that approximately 1 million patients visit the hospital each year with a heart attack. About 1 out of every 5 deaths are due to a heart attack.

Risk factors for heart attack and coronary artery disease include:

- Bad genes (hereditary factors)

- Being male

- Diabetes

- Getting older

- High blood pressure

- Smoking

- Too much fat in your diet

- Unhealthy cholesterol levels, especially high LDL ("bad") cholesterol and low HDL ("good") cholesterol

Symptoms

Chest pain is a major symptom of heart attack. However, some people may have little or no chest pain, especially the elderly and those with diabetes. This is called a silent heart attack.

The pain may be felt in only one part of the body or move from your chest to your arms, shoulder, neck, teeth, jaw, belly area, or back.

The pain can be severe or mild. It can feel like:

- Squeezing or heavy pressure

- A tight band around the chest

- Something heavy sitting on your chest

- Bad indigestion

Other symptoms of a heart attack include:

- Shortness of breath

- Nausea or vomiting

- Anxiety

- Cough

- Fainting

- Lightheadedness - dizziness

- Palpitations (feeling like your heart is beating too fast)

- Sweating, which may be extreme

Signs and Tests »

A heart attack is a medical emergency. If you have symptoms of a heart attack, seek immediate medical help.

The health care provider will perform a physical exam and listen to your chest using a stethoscope. The doctor may hear abnormal sounds in your lungs (called crackles), a heart murmur, or other abnormal sounds.

You may have a rapid pulse. Blood pressure may be normal, high, or low.

Tests to look at your heart include:

- Coronary angiography

- CT scan

- Echocardiography

- Electrocardiogram (ECG) -- once or repeated over several hours

- MRI

- Nuclear ventriculography

- Troponin I and troponin T

- CPK and CPK-MB

- Serum myoglobin

Treatment

If you had a heart attack, you will need to stay in the hospital, possibly in the intensive care unit (ICU). You will be hooked up to an ECG machine, so the health care team can look at how your heart is beating. Life-threatening arrhythmias (irregular heart beats) are the leading cause of death in the first few hours of a heart attack.

The health care team will give you oxygen, even if your blood oxygen levels are normal. This is done so that your body tissues have easy access to oxygen, so your heart doesn't have to work as hard.

An intravenous line (IV) will be placed into one of your veins. Medicines and fluids pass through this IV. You may need a tube inserted into your bladder (urinary catheter) so that doctors can see how much fluid your body gets rid of.

THROMBOLYTIC THERAPY

Depending on the results of the ECG, certain patients may be given blood thinners within 12 hours of when they first felt the chest pain. This is called thrombolytic therapy. The medicine is first given through an IV. Blood thinners taken by mouth may be prescribed later to prevent clots from forming.

Thrombolytic therapy is not appropriate for people who have:

- Bleeding inside their head (intracranial hemorrhage)

- Brain abnormalities such as tumors or blood vessel malformations

- Stroke within the past 3 months (or possibly longer)

- Head injury within the past 3 months

- Severe high blood pressure

- Had major surgery or a major injury within the past 3 weeks

- Internal bleeding within the past 2-4 weeks

- Peptic ulcer disease

- A history of using blood thinners such as coumadin

Many different medicines are used to treat and prevent heart attacks.

- Nitroglycein helps reduce chest pain. You may also receive strong medicines to relieve pain.

- Antiplatelet medicines help prevent clot formation. Aspirin is an antiplatelet drug. Another one is clopidogrel (Plavix).

- Beta-blockers (such as metoprolol, atenolol, and propranolol) help reduce the strain on the heart and lower blood pressure.

- ACE inhibitors (such as ramipril, lisinopril, enalapril, or captopril) are used to prevent heart failure and lower blood pressure.

A procedure called angioplasty may be needed to open blocked coronary arteries. This procedure may be used instead of thrombolytic therapy. Angioplasty with stenting can be a life-saving procedure if you are having a heart attack. However, for persons with coronary heart disease, recent studies show that medicine and angioplasty with stenting have equal benefits. Angioplasty with stenting does not help you live longer, but it can reduce angina or other symptoms of coronary artery disease.

Some people may need emergency coronary artery bypass surgery (CABG).

Expectations (prognosis)

How well you do after a heart attack depends on the amount and location of damaged tissue. Your outcome is worse if the heart attack caused damage to the signaling system that tells the heart to contract.

About a third of heart attacks are deadly. If you live 2 hours after an attack, you are likely to survive, but you may have complications. Those who do not have complications may fully recover.

Usually a person who has had a heart attack can slowly go back to normal activities, including sexual activity.

Complications

- Blood clot in the lungs (pulmonary embolism)

- Cardiogenic shock

- Congestive heart failure

- Damage extending past heart tissue (infarct extension)

- Damage to heart valves or the wall between the two sides of the heart

- Inflammation around the lining of the heart (pericarditis)

- Irregular heart beats, including ventricular tachycardia and ventricular fibrillation

- Side effects of drug treatment

Prevention

To prevent a heart attack:

- Keep your blood pressure, blood sugar, and cholesterol under control.

- Don't smoke.

- Consider drinking 1 to 2 glasses of alcohol or wine each day. Moderate amounts of alcohol may reduce your risk of cardiovascular problems. However, drinking larger amounts does more harm than good.

- Eat a low fat diet rich in fruits and vegetables and low in animal fat.

- Eat fish twice a week. Baked or grilled fish is better than fried fish. Frying can destroy some of the benefits.

- Exercise daily or several times a week. Walking is a good form of exercise. Talk to your doctor before starting an exercise routine.

- Lose weight if you are overweight.

- New guidelines no longer recommend hormone replacement therapy, vitamins E or C, antioxidants, or folic acid to prevent heart disease.

After a heart attack, you will need regular follow-up care to reduce the risk of having a second heart attack. Often, a cardiac rehabilitation program is recommended to help you gradually return to a normal lifestyle. Always follow the exercise, diet, and medication plan prescribed.

A Visceral Fear: Heart Attacks That Strike Out of the Blue

By Melinda Beck WSJ Article : June 20, 2008

My father was planning a trip to Europe one summer afternoon when he went to the bathroom and didn't return. My mother found him dead of a heart attack on the bathroom floor. My husband's grandfather's heart gave out as he was walking down the sidewalk in New York.

Everybody knows somebody who has had a sudden, fatal heart attack, and it's many people's secret fear. More than 300,000 Americans die of heart disease without making it to the hospital each year; most of them from sudden cardiac arrest, according to the American Heart Association. In about half of those cases, the heart attack itself is the first symptom.

Deaths from cardiovascular disease in general have dropped dramatically in recent years, but it is still the No. 1 killer of men and women in the U.S. -- claiming more lives than cancer, chronic respiratory diseases, accidents and diabetes combined.

That's in part because, for all the advances doctors have made in understanding risk factors, lowering cholesterol with statins and propping open narrowed arteries with stents, most heart attacks are caused when tiny bits of plaque break loose and burst like popcorn kernels, forming clots that block arteries. That prevents blood from reaching areas of heart muscle, which start to die. It's hard to predict when that might happen -- which is why people who never knew they had heart disease, and people who thought it was under control, still have sudden heart attacks.

WHEN TO CALL 911

• Common heart-attack signs in men:

-Pressure, fullness in chest that may come and go

-Discomfort in arms, neck, back, jaw

-Shortness of breath

-Lightheadedness

• Women more likely to have:

-Sudden sweating

-Shortness of breath

-Nausea/vomiting

-Back or jaw pain

Source: American Heart Association

"We have terrific therapies that were unimaginable 25 or 30 years ago," says E. Scott Monrad, director of the cardiac catheterization lab at Montefiore Medical Center in Bronx, N.Y. "But one of the biggest risks is dying before you even get to see a doctor."

Last weekend, scores of commentators on health and political blogs offered theories about what might have been done to save NBC's Tim Russert, who died of a sudden heart attack at work Friday. Few details were released, other than that the much-loved "Meet the Press" moderator was being treated for asymptomatic coronary artery disease, had diabetes and an enlarged heart, and had a stress test in April.

Many blog-posters argued that Mr. Russert should have had an angiogram -- an invasive diagnostic test in which the coronary arteries are injected with dye and X-rayed to spot blockages. But even if he had had the procedure an hour before the attack, doctors might not have seen anything to be alarmed about. More than two-thirds of heart attacks occur in arteries that are less than 50% narrowed by plaque buildup -- and those are often too small to show up on an angiogram or cause much chest pain.

Similarly, the stress test Mr. Russert had is better suited to detecting significantly narrowed arteries than the small, soft unstable kind of plaque that often causes fatal blood clots.

Indeed, about a third of people who have heart attacks don't have the usual risk factors, such as family history of heart disease, abdominal fat, high blood pressure or high cholesterol.

RISK FACTORS

The symptoms that make up "metabolic syndrome" put people at high risk for heart attack, stroke and diabetes. (Smoking and heavy alcohol consumption also raise the risk.)

• Waist more than 40 inches for men; 35 inches for women

• Blood pressure over 130/85mmHg

• Fasting glucose over 110 mg/dl

• Triglycerides over 150 mg/dl

• LDL cholesterol over 100 mg/dl

• HDL cholesterol under 40 mg/dl

Source: American Medical Association

"Time and again we see examples of unexpected cardiac disease in people who didn't know they had it," says Prediman K. Shah, director of cardiology at Cedars-Sinai Heart Institute in Los Angeles, one of many experts who think wider use of coronary calcium CT scans could help spot more people at risk of soft-plaque blockages. The noninvasive procedure takes about 15 minutes and costs a few hundred dollars. But few insurers cover it because there is scant evidence that treating people on that basis saves lives.

At a minimum, seeing a picture of the calcium lining their arteries can be a wake-up call for patients to take their coronary-artery disease seriously and to be diligent in taking medication, exercising and making other healthy lifestyle changes.

Mr. Russert's family and physicians haven't disclosed how his coronary artery disease was diagnosed, or how he was being treated. NBC colleagues said the 58-year-old journalist had been working to control his condition with exercise and diet, though his weight was an ongoing struggle. He had also returned from a family trip to Italy the day before, following a grueling -- but exhilarating -- political primary season.

Not all heart attacks are fatal. Most of the 1.2 million Americans who had one last year survived. If the area of oxygen-starved heart muscle is small, or in the right ventricle, the heart can often keep pumping, allowing the patient to make it to a hospital, where doctors can break up the blockage with a clot-dissolving drug or catheterization. The situation becomes rapidly fatal if the heart starts beating wildly, and ineffectively, as it struggles to keep pumping. Unless it is jolted back into a normal rhythm within a few minutes, the patient's brain will starve for oxygen and shut down.

Some patients with enlarged hearts like Mr. Russert's are candidates for internal defibrillators that can continuously monitor heart rhythm and keep it regular automatically. Vice President Dick Cheney, who has survived four heart attacks, has one.

Many airports, shopping malls, schools and offices have portable Automatic External Defibrillators, or AEDs, on hand as well. They're designed to automatically assess a victim's heart rhythm and administer an electrical jolt as needed. The NBC office reportedly didn't have an AED, but an intern performed cardiopulmonary resuscitation on Mr. Russert until paramedics arrived with a defibrillator.

"The earlier CPR is started, the higher the rate of success," says Dr. Monrad, who says he has had several cases in which vigorous CPR in the field bought precious time and saved a life. On average, however, only a small percentage of people in full cardiac arrests are successfully revived.

More widespread use of AEDs and wider CPR training could save some future victims' lives. Some bloggers suggested that more-aggressive treatment of Mr. Russert's artery disease might have bought him some time, though most experts declined to speculate.

But stents, angioplasty and bypass surgery are only stop-gap measures that don't do anything to halt the progress of the underlying disease. "Everytime I do a procedure on a patient, the family comes up and says, 'Now we don't have to worry anymore,' but that's the wrong message," says Dr. Monrad. "Physicians have to be tough on the standards we set for patients, and patients have to be tougher about the kind of lifestyle choices they make."

The heart has many mysteries that scientists are still unraveling, such as what causes those killer bits of plaque to rupture, the role of inflammation, the complex interplay of diet, vitamins and amino acids like homocysteine. Even the size of cholesterol particles is under scrutiny. "The more small LDL particles you have, the higher your risk of heart disease," says Larry McCleary, a former pediatric neurosurgeon at Denver Children's Hospital who had a heart attack while on rounds at age 46, and has since lost weight, reduced his blood pressure and triglycerides, and exercises daily.

"It's important that each person take responsibility for taking care of themselves," says Edmund Herrold, a clinical cardiologist in New York City and professor at Weill Cornell Medical College. "Get a regular checkup. Watch your weight and your blood pressure and your cholesterol and if you have diabetes, keep that under control. Exercise. Take an aspirin every day. Eliminate meat. There's no guarantee, but you can dramatically lower the risk of a cardiac event if you pay attention to these issues."

The Guide to Beating a Heart Attack

First Line of Defense Is Lowering Risk, Even When Genetics Isn't on Your Side

Ron Wislow : WSJ : April 16, 2012

Here's the good news: Heart disease and its consequences are largely preventable. The bad news is that nearly one million Americans will suffer a heart attack this year.

Still, cardiovascular disease remains the leading killer of both men and women. Doctors worry that the steady progress from an intense public-health campaign beginning in the 1960s is in jeopardy thanks to the obesity epidemic and rising prevalence of diabetes. Only a relative handful of people are fully compliant with recommendations for diet, exercise and other personal habits well proven to help keep hearts healthy.

Particularly troubling are increasingly common reports of heart attacks among younger people, even those in their 20s and 30s, says Donald M. Lloyd-Jones, a cardiologist and chief of preventive medicine at Northwestern University's Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago.

There is a lot a person can do to help prevent a heart attack. One international study found that about 90% of the risk associated with such factors as high cholesterol and blood pressure, physical activity, smoking and diet, are within a person's ability to control. The study, called Interheart, compared 15,000 people from every continent who suffered a heart attack with a similar number of relatives or close associates who didn't.

While genetics plays a role in up to one-half of heart attacks, "You can trump an awful lot of your genetics with choices you make and with medicines if you need them," says Dr. Lloyd-Jones.

The Basics