- RETIREMENT ANNOUNCEMENT

- HOME PAGE

- "MYCHART" the new patient portal

- BELMONT MEDICAL ASSOCIATES

- MOUNT AUBURN HOSPITAL

- EMERGENCIES

- PRACTICE PHILOSOPHY

- MY RESUME

- TELEMEDICINE CONSULTATION

- CONTACT ME

- LAB RESULTS

- ePRESCRIPTIONS

- eREFERRALS

- RECORD RELEASE

- MEDICAL SCRIBE

- PHYSICIAN ASSISTANT (PA)

- Medicare Annual Wellness Visit

- Case management/Social work

- Quality Care Measures

- Emergency closing notice

- FEEDBACK

- Talking to your doctor

- Choosing..... and losing a doctor

- INDEX A - Z

- ALLERGIC REACTIONS

- Alternative Medicine

- Alzheimer's Disease

- Bladder Problems

- Blood disorders

- Cancer Concerns

- GENETIC TESTING FOR HEREDITARY CANCER

- Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

- Controversial Concerns

- CPR : Learn and save a life

- CRP : Inflammatory marker

- Diabetes Management

- Dizziness, Vertigo,Tinnitus and Hearing Loss

- EXERCISE

- FEMALE HEALTH

-

GASTROINTESTINAL topics

- Appendicitis

- BRAT diet

- Celiac Disease or Sprue

- Crohn's Disease

- Gastroenterologists for Colon Cancer Screening

- Colonoscopy PREP

- Constipation

- Gluten sensitivity, but not celiac disease

- Heartburn and GERD

- Hemorrhoids and Anal fissure

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- NASH : Non Alcoholic Steato Hepatitis

- FEET PROBLEMS

- HEART RELATED topics

-

INFECTIOUS DISEASES

- Antibiotic Resistance

- Cat bites >

- Clostridia difficile infection - the "antibiotic associated germ"

- CORONA VIRUS

- Dengue Fever and Chikungunya Fever

- Food borne illnesses

- Shingles Vaccine

- Hepatitis B

- Hepatitis C

- Herpes

- Influenza

- Helicobacter pylori - the "ulcer germ"

- HIV Screening

- Lyme and other tick borne diseases

- Measles

- Meningitis

- MRSA (Staph infection)

- Norovirus

- Sexually Transmitted Diseases

- Shingles (Herpes Zoster)

- Sinusitis

- West Nile Virus

- Whooping Cough (Pertussis)

- Zika virus and pregnancy

- INSURANCE related topics

- KIDNEY STONES

- LEG CRAMPS

- LIBRARY for patients

- LIFE DECISIONS

- MALE HEALTH

- Medication/Drug side effects

- MEDICAL MARIJUANA

- MENTAL HEALTH

- Miscellaneous Articles

-

NUTRITION - EXERCISE - WEIGHT

- Cholesterol : New guidelines for treatment

- Advice to lower your cholesterol

- Cholesterol : Control

- Cholesterol : Raising your HDL Level

- Exercise

- Food : Making Smart Choices

- Food : Making Poor Choices

- Food : Grape Fruit and Drug Interaction

- Food : Vitamins, Minerals and Supplements

- Omega 3 fatty acids

- Vitamin B12 deficiency

- Vitamin D

- Weight Loss

- ORTHOPEDICS

- PAIN

- PATIENTS' RIGHTS

- SKIN

- SLEEP

- SMOKING

- STROKE

- THYROID

- SUBSTANCE ABUSE

- Travel and Vaccination

- TREMOR

- Warfarin Anticoagulation

- OTHER STUFF FOLLOWS

- Fact or Opinion?

- Hippocratic Oath

- FREE ADVICE.......for what its worth!

- LAUGHTER.....is the best medicine

- Physicians Pet Peeves

- PHOTO ALBUM - its not all work!

- Cape Town, South Africa

- Tribute page

- The 100 Club

- Free Wi-Fi

ANTIBIOTIC RESISTANCE

In an attempt to reduce the development of resistant bacteria, I try my best to avoid the unnecessary and inappropriate use of antibiotics.

Remember: antibiotics are ineffective against viral infections.

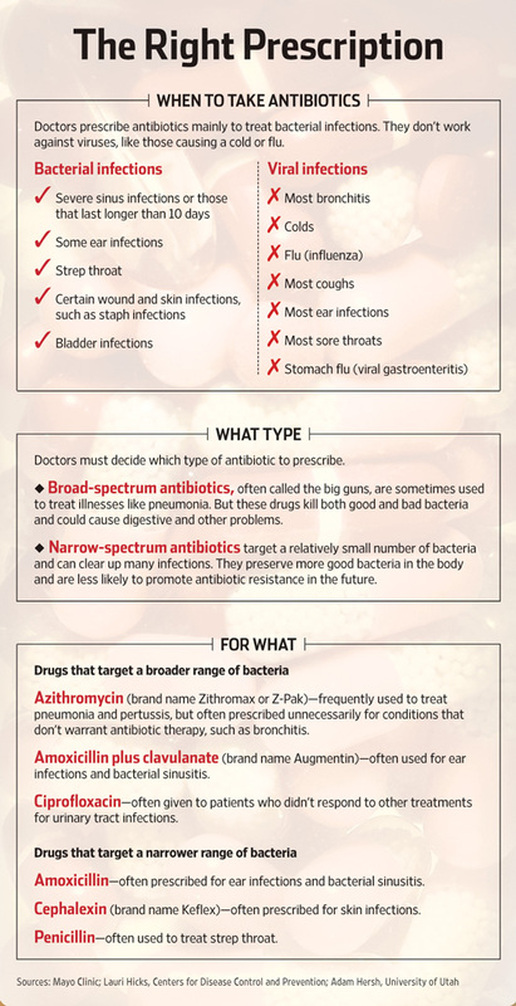

What are antibiotics?

Antibiotics are prescription drugs that attack bacterial germs. They are powerful substances, which can kill or disable disease-causing bacteria.

When do I take antibiotics?

You will be given a prescription for antibiotics when bacteria cause your illness.

Are antibiotics safe to take?

Antibiotics are generally safe and should always be taken as prescribed. As with any medication, antibiotics may have side effects.

Can I save the antibiotic for the next time I am sick?

No. Leftover antibiotics are not a complete dose. Always talk to your doctor because bacteria may not cause your symptoms. If you do have another bacterial infection, a complete dose of antibiotic is needed to kill all the harmful bacteria.

Why should I be concerned about resistant bacteria?

If your prescription does not work against a bacterial germ, your illness lasts longer, and you may have to make return office and pharmacy visits to find the right drug to kill the germ. For more serious infections, it is possible that you would need to be hospitalized or could even die if the infection could not be stopped. Also, while the resistant bacteria are still alive, you act as a carrier of these germs, and you could pass them to friends or family members.

Does that mean I should take antibiotics for the flu or common cold?

No. Colds and influenza are caused by viruses, not by bacteria. Antibiotics don't work against viruses.

When I start feeling better can I stop taking the antibiotic?

No. Your prescription is written to cover the time needed to help your body fight all the harmful bacteria. If you stop your antibiotic early, the bacteria that have not yet been killed can restart an infection.

What is antibiotic resistance?

Sometimes bacteria find a way to fight the antibiotic you are taking and your infection won't go away. This is called antibiotic resistance. When resistance develops you will need to receive a different antibiotic to fight your infection.

What can I do about antibiotic resistance?

A new class of antibiotic drugs is not expected to appear in the immediate future. If bacteria become resistant to all our current antibiotics, we won't have any other alternatives. Using antibiotics wisely will help preserve their effectiveness in the years ahead.

What factors contribute to antibiotic resistance?.

- Misuse and overuse of antibiotics in humans, animals and agriculture;

- demand for antibiotics when antibiotics are not appropriate;

- failure to finish an antibiotic prescription;

- availability of antibiotics without a prescription in some countries

What you can do to prevent antibiotic resistance:

- Do not demand antibiotics from your physician.

- When given antibiotics, take them exactly as prescribed and complete the full course of treatment; do not hoard pills for later use or share leftover antibiotics.

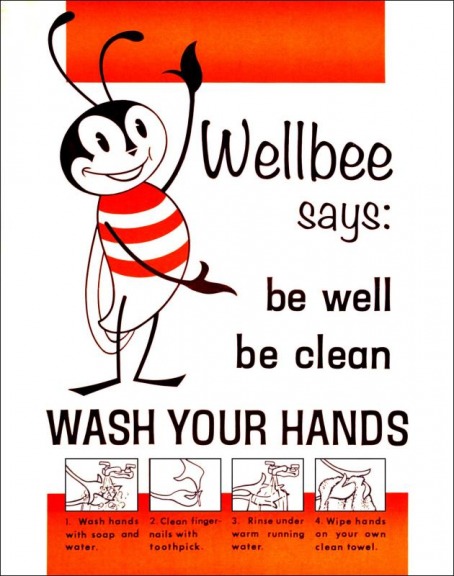

- Wash your hands properly to reduce the chance of getting sick and spreading infection.

- Wash fruits and vegetables thoroughly;

- avoid raw eggs and undercooked meat, especially in ground form. (The majority of food items which cause diseases are raw or undercooked foods of animal origin such as meat, milk, eggs, cheese, fish or shellfish.)

- When protecting a sick person whose defenses are weakened, soaps and other products with antibacterial chemicals are helpful, but should be used according to established procedures and guidelines.

'Superbugs' That Strike the Sickest Patients

By Laura Landro : WSJ Article : October 1, 2008

In hospitals' war against drug-resistant superbugs, a class of bacteria once thought to be fairly benign is emerging as a deadly threat to the sickest and most vulnerable patients. The scourge -- known as gram-negative bacteria -- is throwing a new wrench into efforts to contain the spread of deadly infections.

Amid more than 1.7 million infections annually in hospitals, prevention efforts have been aimed at the most widespread organisms, like the staph infection MRSA and others in the so-called gram-positive category. These can still be thwarted by antibiotics such as vancomycin.

Acinetobacter is becoming resistant to all antibiotics.

But some of these bugs' wily cousins -- which don't pick up the purplish dye used in the test to distinguish them from gram-positive bacteria -- are becoming ultra-resistant. The extra outer membrane that rejects the stain also gives them additional armor against antibiotics. Some also produce an enzyme, known as ESBL, that enables them to break down antibiotics and develop even more resistance.

While they don't cause disease in healthy people, infections by gram-negative bacteria can be devastating for those with weak immune systems: wounded soldiers, burn victims, cancer and AIDS patients, the elderly, premature infants and those with severe injuries or illnesses. The gram-negative bugs that pose the biggest threat include acinetobacter baumannii, enterobacter aerogenes, and pseudomonas aeruginosa, which can attack through wounds, surgical incisions, central lines, respirators and catheters.

Most worrisome, says Centers for Disease Control and Prevention epidemiologist Arjun Srinivasan, is that bacteria like acinetobacter are becoming resistant to the class of drugs known as carbapenems, considered a last line of defense for gram-negative organisms.

Hospitals are now scrambling to come up with strategies to fight both gram-positive and gram-negative classes of bacteria, without increasing the chances that preventing one will lead to the rise of the other. "The gram-negative bacteria are catapulting past MRSA and now getting resistant to almost every antibiotic, which can mean a death sentence" for the sickest patients says Peter Pronovost, a professor at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. With no new antibiotics immediately on the horizon for either class, preventing infections "comes down to blocking and tackling," Dr. Pronovost says -- quickly diagnosing infections, using appropriate antibiotics and "going back to basics" such as getting health-care workers to wash hands.

In partnership with the Michigan Hospital Association, Dr. Pronovost developed a program to prevent bloodstream infections, which can be caused by both gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria and often strike patients in ICUs with large catheters inserted into their veins. With five practices -- handwashing, draping patients before inserting the lines, cleaning the skin properly, avoiding catheters in the groin and removing them as soon as possible -- the consortium reported that the rate of infections in Michigan ICUs dropped by 66% over an 18-month period. The process saved more than 1,729 lives and $246 million.

Dr. Pronovost says that while the steps are well-established, his research shows doctors skip steps more than a third of the time. Today, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, part of the federal Department of Health and Human Services, plans to announce that it will provide funding to expand Dr. Pronovost's program to 10 other states.

Hospitals are struggling to determine how best to detect the presence of different types of bacteria and identify patients on admission who might carry them on their skin or in their intestinal tract. Such screening programs can be costly, and it isn't clear who will pay for them. "You can't culture every patient in every bed for every possible resistant organism," says Gina Pugliese, vice president of the safety institute at Premier Inc., a large hospital purchasing cooperative.

Hospitals are launching myriad new efforts to combat the bugs: They are sterilizing equipment with techniques including vaporized hydrogen peroxide that can decontaminate equipment without harm, discarding contaminated devices, bathing ICU patients with a chemical antiseptic and closing down units for decontamination. They are also requiring hospital workers to wear protective equipment when caring for infected patients or those considered at risk for infection, draping patients from head to toe during procedures and isolating infected patients.

The measures can be hard on patients and families, especially those placed in isolation, says Pat Rosenbaum, a nurse who is authoring new guidelines from the Association of Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology for the prevention of acinetobacter infections, to be released next year. "We don't take lightly putting people into these kind of precautions, but we also don't want to take a risk that they might infect others," she says.

Because overuse of antibiotics is considered a primary culprit in the growing drug-resistance of all bugs, hospitals are forcing physicians to be more judicious in their use of antibiotics, saving the powerful broad-spectrum drugs for the infections known to respond to them. But it can take two or three days to get lab results back that identify bugs, making it harder to determine the right antibiotic to nip infections in the bud before they rage out of control. Hospitals are experimenting with rapid-testing technology that allows them to diagnose lab cultures within hours instead of the one to three days it now takes, but such tests are not yet widely available.

Marin Kollef, a critical-care specialist at Barnes-Jewish Hospital, in St. Louis, Mo., says that if patients come in with a severe infection such as septic shock, he will order three or more antibiotics to cover both gram-negative and gram-positive organisms, then alter treatment once lab cultures come back with a more-specific diagnosis. "The lab may take 24 to 72 hours to get the information back, and if a clinician makes a wrong decision, too much time may go by before the patient gets the right drug," adding to the risk of death, he says.

Infectious-disease experts say the most worrisome of the gram-negative bacteria may be acinetobacter, which is commonly found in soil and water, and may be carried by up to 40% of people on their skin. Over the past several years, a virulent strain has developed increasing resistance to antibiotics. This strain survives in hospitals for long periods and targets severely ill patients through the skin and airways, causing pneumonia and infections in the skin, tissue, central nervous system and bones. There have been a growing number of infections in wounded military personnel returning from Iraq and Afghanistan, where the bacteria thrive in the soil of the hot, humid climates.

Johns Hopkins learned the hard way how quickly acinetobacter can spread. In October 2003, it found that a treatment known as pulsatile lavage -- which uses a spray-like device to irrigate and treat wounds -- was also dispersing acinetobacter from patients who carried the bug into the air via droplets. Johns Hopkins's analysis suggested that the bacteria may have landed on surfaces and then been spread via health-care workers, and was also possibly inhaled by some patients.

Of 11 patients colonized or infected with a drug-resistant form of the bacteria, eight developed wound infections and three had both bloodstream infections and pneumonia; two deaths were linked to the infections. The outbreak was halted by aggressive infection-control measures, including closing and renovating the wound-care treatment unit to add private rooms.

Trish Perl, a professor of medicine and hospital epidemiologist at Johns Hopkins, says the hospital has not had an outbreak of infection since changing its practices, but still sees patients colonized with acinetobacter coming into the hospital, especially from long-term care facilities; her group is paged every time a new case is identified to make sure that the appropriate precautions are in place.

After the death of their 27-year-old son, Josh, linked to an infection with a gram-negative bacterium, Victoria and Armando Nahum started a nonprofit group to raise awareness of prevention (safecarecampaign.org). Their group promotes steps patients can take in hospitals such as asking about what screening is done to prevent infection, questioning surgeons about the need for pre- and post-operative antibiotics, and insisting staffers wash their hands in the presence of the patient and family.

Josh, a skydiving instructor in Loveland, Colo., fractured his femur and skull on a jump, and after recovering from a bacterial infection in the ICU, later contracted the infection enterobacter aerogenes in his spinal fluid, which damaged his central nervous system and rendered him a quadriplegic and ventilator-dependent. His infection responded to none of the antibiotics administered, his father says.

"We seem to be out of bullets for these multi-drug-resistant organisms, so we have to find ways to control and prevent these infections, because once your family starts down that path it is a black hole," says Mr. Nahum.

An Emerging Threat

Gram-negative bacteria, harmless to the healthy, are fast developing resistance to antibiotics and infecting the sickest patients.

Bacteria : Acinetobacter

Found in : soil, water; humid climates, skin

Infects: lungs ( pneumonia), blood, wounds

Bacteria :Enterobacter Aerogenes

Found in : soil, dairy products, sewage, intestinal tract

Infects : respiratory, tract, skin, soft tissue, urinary tract, bone

Bacteria : Pseudomonas aeruginosa

Found in : soil, water, skin, vegetation, fruits

Infects : urinary, respiratory, skin, bone, joint, gut, ear, eye, nervous system

Bacteria : Klebsiella

Found in : soil, water, vegetables,

nfects : intestinal tract, skin, throat

Deadly Bacteria Found to Be More Common

By Kevin Sack : NY Times Article : October 17, 2007

Nearly 19,000 people died in the United States in 2005 after being infected with virulent drug-resistant bacteria that have spread rampantly through hospitals and nursing homes, according to the most thorough study of the disease’s prevalence ever conducted.

The government study, which is being published Wednesday in The Journal of the American Medical Association, suggests that such infections may be twice as common as previously thought, according to its lead author, Dr. R. Monina Klevens.

If the mortality estimates are correct, the number of deaths associated with the germ, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, or MRSA, would exceed those attributed to H.I.V.-AIDS, Parkinson’s disease, emphysema or homicide each year.

By extrapolating data collected in nine places, the researchers estimated that 94,360 patients developed an invasive infection from the pathogen in 2005 and that nearly one of every five, or 18,650 of them, died. The study points out that it is not always possible to determine whether a death is caused by MRSA or merely accelerated by it.

The authors, who work for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, cautioned that their methodology differed significantly from previous studies and that direct comparisons were therefore risky. But they said they were surprised by the prevalence of serious infections, which they calculated as 32 cases per 100,000 people.

In an accompanying editorial in the medical journal, Dr. Elizabeth A. Bancroft, an epidemiologist with the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health, characterized that finding as “astounding.”

The prevalence of invasive MRSA — when the bacteria has not merely colonized on the skin, but has attacked a normally sterile part of the body, like the organs — is greater, Dr. Bancroft wrote, than the combined rates for other conditions caused by invasive bacteria, including bloodstream infections, meningitis and flesh-eating disease.

The study also concluded that 85 percent of invasive MRSA infections are associated with health care treatment. Previous research had indicated that many hospitals and long-term care centers had become breeding grounds for MRSA because bacteria could be transported from patient to patient by doctors, nurses and unsterilized equipment.

“This confirms in a very rigorous way that this is a huge health problem,” said Dr. John A. Jernigan, the deputy chief of prevention and response in the division of healthcare quality promotion at the disease control agency. “And it drives home that what we do in health care will have a lot to do with how we control it.”

The findings are likely to stimulate further an already active debate about whether hospitals and other medical centers should test all patients for MRSA upon admission. Some hospitals have had notable success in reducing their infection rates by isolating infected patients and then taking extra precautions, like requiring workers to wear gloves and gowns for every contact.

But other research has suggested that such techniques may be excessive, and may have the unintended consequence of diminishing medical care for quarantined patients. The disease control agency, in guidelines released last year, recommended that hospitals try to reduce infection rates by first improving hygiene and resort to screening high-risk patients only if other methods fail.

Dr. Lance R. Peterson, an epidemiologist with Evanston Northwestern Healthcare, said his hospital system in the Chicago area reduced its rate of invasive MRSA infections by 60 percent after it began screening all patients in 2005.

“This study puts more onus on organizations that don’t do active surveillance to demonstrate that they’re reducing their MRSA infections,” Dr. Peterson said. “Other things can work, but nothing else has been demonstrated to have this kind of impact. MRSA is theoretically a totally preventable disease.”

Numerous studies have shown that busy hospital workers disregard basic standards of hand-washing more than half the time. This week, Consumers Union, the nonprofit publisher of Consumer Reports, called for hospitals to begin publishing their compliance rates for hand-washing.

Lisa A. McGiffert, manager of the “Stop Hospital Infections” campaign at Consumers Union, said, “This study just accentuates that the hospital is ground zero, that this is where dangerous infections are occurring that are killing people every day.”

MRSA, which was first isolated in the United States in 1968, causes 10 percent to 20 percent of all infections acquired in health care settings, according to the disease control agency. Resistant to a number of front-line antibiotics, it can cause infections of surgical sites, the urinary tract, the bloodstream and lungs. Treatment often involves the intravenous delivery of other drugs, causing health officials to worry that overuse will breed further resistance.

The bacteria can be brought unknowingly into hospitals and nursing homes by patients who show no symptoms, and can be transmitted by contact as casual as the brush of a doctor’s lab coat. Highly opportunistic, they can enter the bloodstream through incisions and wounds and then quickly overwhelm a weakened immune system.

On Monday, a Virginia teenager died after a weeklong hospitalization for an MRSA infection that spread quickly to his kidneys, liver, lungs and the muscle around his heart. Local officials promptly closed 21 schools for a thorough cleaning.

A major difference between the new study and its predecessors is that it compiled confirmed cases of MRSA infection, rather than relying on coded patient records that sometimes lack precision. The study found higher prevalence rates and death rates for the elderly, African-Americans and men. The figures also varied by geography, with Baltimore’s incidence rates far exceeding those of the eight other locations: Connecticut; Atlanta; San Francisco; Denver; Portland, Ore.; Monroe County, N.Y.; Davidson County, Tenn.; and Ramsey County, Minn.

Dr. Klevens said further research would be needed to understand the racial and geographic disparities.

MRSA infection

Introduction

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infection is caused by Staphylococcus aureus bacteria — often called "staph." Decades ago, a strain of staph emerged in hospitals that was resistant to the broad-spectrum antibiotics commonly used to treat it. Dubbed methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), it was one of the first germs to outwit all but the most powerful drugs. MRSA infection can be fatal.

Staph bacteria are normally found on the skin or in the nose of about one-third of the population. If you have staph on your skin or in your nose but aren't sick, you are said to be "colonized" but not infected with MRSA. Healthy people can be colonized with MRSA and have no ill effects, however, they can pass the germ to others.

Staph bacteria are generally harmless unless they enter the body through a cut or other wound, and even then they often cause only minor skin problems in healthy people. But in older adults and people who are ill or have weakened immune systems, ordinary staph infections can cause serious illness called methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus or MRSA.

In the 1990s, a type of MRSA began showing up in the wider community. Today, that form of staph, known as community-associated MRSA, or CA-MRSA, is responsible for many serious skin and soft tissue infections and for a serious form of pneumonia.

Vancomycin is one of the few antibiotics still effective against hospital strains of MRSA infection, although the drug is no longer effective in every case. Several drugs continue to work against CA-MRSA, but CA-MRSA is a rapidly evolving bacterium, and it may be a matter of time before it, too, becomes resistant to most antibiotics.

Signs and symptoms

Staph infections, including MRSA, generally start as small red bumps that resemble pimples, boils or spider bites. These can quickly turn into deep, painful abscesses that require surgical draining. Sometimes the bacteria remain confined to the skin. But they can also burrow deep into the body, causing potentially life-threatening infections in bones, joints, surgical wounds, the bloodstream, heart valves and lungs.

Causes

Although the survival tactics of bacteria contribute to antibiotic resistance, humans bear most of the responsibility for the problem.

Leading causes of antibiotic resistance include:

- Unnecessary antibiotic use in humans. Like other superbugs, MRSA is the result of decades of excessive and unnecessary antibiotic use. For years, antibiotics have been prescribed for colds, flu and other viral infections that don't respond to these drugs, as well as for simple bacterial infections that normally clear on their own.

- Antibiotics in food and water. Prescription drugs aren't the only source of antibiotics. In the United States, antibiotics can be found in beef cattle, pigs and chickens. The same antibiotics then find their way into municipal water systems when the runoff from feedlots contaminates streams and groundwater. Routine feeding of antibiotics to animals is banned in the European Union and many other industrialized countries. Antibiotics given in the proper doses to animals who are sick don't appear to produce resistant bacteria.

- Germ mutation. Even when antibiotics are used appropriately, they contribute to the rise of drug-resistant bacteria because they don't destroy every germ they target. Bacteria live on an evolutionary fast track, so germs that survive treatment with one antibiotic soon learn to resist others. And because bacteria mutate much more quickly than new drugs can be produced, some germs end up resistant to just about everything. That's why only a handful of drugs are now effective against most forms of staph.

Because hospital and community strains of MRSA generally occur in different settings, the risk factors for the two strains differ.

Risk factors for hospital-acquired (HA) MRSA include:

- A current or recent hospitalization. MRSA remains a concern in hospitals, where it can attack those most vulnerable — older adults and people with weakened immune systems, burns, surgical wounds or serious underlying health problems. A 2007 report from the Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology estimates that 1.2 million hospital patients are infected with MRSA each year in the United States. They also estimate another 423,000 are colonized with it.

- Residing in a long-term care facility. MRSA is far more prevalent in these facilities than it is in hospitals. Carriers of MRSA have the ability to spread it, even if they're not sick themselves.

- Invasive devices. People who are on dialysis, are catheterized, or have feeding tubes or other invasive devices are at higher risk.

- Recent antibiotic use. Treatment with fluoroquinolones (ciprofloxacin, ofloxacin or levofloxacin) or cephalosporin antibiotics can increase the risk of HA-MRSA.

- Young age. CA-MRSA can be particularly dangerous in children. Often entering the body through a cut or scrape, MRSA can quickly cause a wide spread infection. Children may be susceptible because their immune systems aren't fully developed or they don't yet have antibodies to common germs. Children and young adults are also much more likely to develop dangerous forms of pneumonia than older people are.

- Participating in contact sports. CA-MRSA has crept into both amateur and professional sports teams. The bacteria spread easily through cuts and abrasions and skin-to-skin contact.

- Sharing towels or athletic equipment. Although few outbreaks have been reported in public gyms, CA-MRSA has spread among athletes sharing razors, towels, uniforms or equipment.

- Having a weakened immune system. People with weakened immune systems, including those living with HIV/AIDS, are more likely to have severe CA-MRSA infections.

- Living in crowded or unsanitary conditions. Outbreaks of CA-MRSA have occurred in military training camps and in American and European prisons.

- Association with health care workers. People who are in close contact with health care workers are at increased risk of serious staph infections.

Keep an eye on minor skin problems — pimples, insect bites, cuts and scrapes — especially in children. If wounds become infected, see your doctor. Ask to have any skin infection tested for MRSA before starting antibiotic therapy. Drugs that treat ordinary staph aren't effective against MRSA, and their use could lead to serious illness and more resistant bacteria.

Screening and diagnosis

Doctors diagnose MRSA by checking a tissue sample or nasal secretions for signs of drug-resistant bacteria. The sample is sent to a lab where it's placed in a dish of nutrients that encourage bacterial growth (culture). But because it takes about 48 hours for the bacteria to grow, newer tests that can detect staph DNA in a matter of hours are now becoming more widely available.

In the hospital, you may be tested for MRSA if you show signs of infection or if you are transferred into a hospital from another healthcare setting where MRSA is known to be present. You may also be tested if you have had a previous history of MRSA.

Treatment

Both hospital and community associated strains of MRSA still respond to certain medications. In hospitals and care facilities, doctors generally rely on the antibiotic vancomycin to treat resistant germs. CA-MRSA may be treated with vancomycin or other antibiotics that have proved effective against particular strains. Although vancomycin saves lives, it may grow resistant as well; some hospitals are already seeing outbreaks of vancomycin-resistant MRSA. To help reduce that threat, doctors may drain an abscess caused by MRSA rather than treat the infection with drugs.

Prevention

Hospitals are fighting back against MRSA infection by using surveillance systems that track bacterial outbreaks and by investing in products such as antibiotic-coated catheters and gloves that release disinfectants.

Still, the best way to prevent the spread of germs is for health care workers to wash their hands frequently, to properly disinfect hospital surfaces and to take other precautions such as wearing a mask when working with people with weakened immune systems.

In the hospital, people who are infected or colonized with MRSA are placed in isolation to prevent the spread of MRSA to other patients and healthcare workers.Visitors and healthcare workers caring for isolated patients may be required to wear protective garments and must follow strict handwashing procedures.

What you can do

Here's what you can do to protect yourself, family members or friends from hospital-acquired infections.

- Ask all hospital staff to wash their hands before touching you — every time.

- Wash your own hands frequently.

- Ask to be bathed with disposable cloths treated with a disinfectant rather than with soap and water.

- Make sure that intravenous tubes and catheters are inserted and removed under sterile conditions; some hospitals have dramatically reduced MRSA blood infections simply by sterilizing patients' skin before using catheters.

Protecting yourself from CA-MRSA — which might be just about anywhere — may seem daunting, but these common-sense precautions can help reduce your risk:

- Keep personal items personal. Avoid sharing personal items such as towels, sheets, razors, clothing and athletic equipment. MRSA spreads on contaminated objects as well as through direct contact.

- Keep wounds covered. Keep cuts and abrasions clean and covered with sterile, dry bandages until they heal. The pus from infected sores often contains MRSA, and keeping wounds covered will help keep the bacteria from spreading.

- Sanitize linens. If you have a cut or sore, wash towels and bed linens in hot water with added bleach and dry them in a hot dryer. Wash gym and athletic clothes after each wearing.

- Wash your hands. In or out of the hospital, careful hand washing remains your best defense against germs. Scrub hands briskly for at least 15 seconds, then dry them with a disposable towel and use another towel to turn off the faucet. Carry a small bottle of hand sanitizer containing at least 62 percent alcohol for times when you don't have access to soap and water.

- Get tested. If you have a skin infection that requires treatment, ask your doctor if you should be tested for MRSA. Many doctors prescribe drugs that aren't effective against antibiotic-resistant staph, which delays treatment and creates more resistant germs.

Here are answers to common questions about community-acquired staph infections, or CA-MRSA.

What does CA-MRSA look like?

CA-MRSA is primarily a skin infection. It often resembles a pimple, boil or spider bite, but it quickly worsens into an abscess or puss-filled blister or sore. Patients who have sores that won’t heal or are filled with pus should see a doctor and ask to be tested for staph infection. They should not squeeze the sore or try to drain it — that can spread the infection to other parts of the skin or deeper into the body.

Who is at risk?

The vast majority of MRSA cases happen in hospital settings, but 10 percent to 15 percent occur in the community at large among otherwise healthy people. Infections often occur among people who are prone to cuts and scrapes, such as children and athletes. MRSA typically spreads by skin-to-skin contact, crowded conditions and the sharing of contaminated personal items. Others who should be watchful: people who have regular contact with health care workers, those who have recently taken such antibiotics as fluoroquinolones or cephalosporin, homosexual men, military recruits and prisoners. Clusters of infections have appeared in certain ethnic groups, including Pacific Islanders, Alaskan Natives and Native Americans.

What can I do to lower my risk of contracting MRSA?

Bathing regularly and washing hands before meals is just a start. Wash your hands often or use an antibacterial sanitizer after you’ve been in public places or have touched handrails and other highly trafficked surfaces. Make sure cuts and scrapes are bandaged until they heal. Wash towels and sheets regularly, preferably in hot water, and leave clothes in the dryer until they are completely dry. “Staph is a pretty hardy organism,’’ said Dr. Gerba.

Remind kids and teenagers that personal items shouldn’t be shared with their friends, he added. This includes brushes, combs, razors, towels, makeup and cell phones. A teenager in Dr. Gerba’s own family once contracted MRSA, he said, and he eventually traced the bacteria to her cell phone. She had shared it with a friend whose mother worked in a nursing home. Dr. Gerba went on to discover MRSA on the friend’s cell phone and makeup compact and on a countertop in her home.

Where does MRSA lurk?

The bacteria may be found on the skin and in the noses of nearly 30 percent of the population without causing harm. Experts believe it survives on surfaces in 2 percent to 3 percent of homes, cars and public places.

But the bacteria are evolving, and the statistics may already underestimate the prevalence of MRSA. Be especially vigilant in health clubs and gyms — staph grows rapidly in warm, moist environments. The risks of infection and necessary precautions should be explained to student athletes, particularly those in contact sports who often suffer cuts and spend time in locker rooms. When working out at the gym, make sure you wipe down equipment before you use it. Many people clean just the sweaty benches, but Dr. Gerba notes that MRSA also has been found on the grips of workout machines. And if you have a scrape or sore, keep it clean and bandaged until it heals. Minor cuts and scrapes are the way MRSA takes hold.

What is the single best thing I can do to protect myself from MRSA?

Without question, people need to show far more respect for antibiotics. Misuse of antibiotics allows bacteria to evolve and develop resistance to drugs. But parents often pressure pediatricians to prescribe antibiotics even when they don’t help the vast majority of childhood infections. When you do take an antibiotic, finish the dose. Antibiotic resistance is bad for everyone, but your body can also become particularly vulnerable to resistant bacteria if you are careless with the drugs.

How do I find out more?

One of the most useful Web sites is a MRSA primer from Mayoclinic.com. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention offers a useful Q&A about MRSA in schools.

CDC officials stress that the number of such infections is still relatively low, and children ages 5 to 17 years have the lowest rate of MRSA infection of any age group. The overall physical environment, moreover, hasn't played a significant role in the transmission of MRSA. Transmission occurs with direct contact with an infected person or contaminated items, such as sporting equipment or clothing. So scrubbing down locker-room walls as if they were a biohazard hot zone isn't going to protect kids as well as making sure that they keep their hands clean, cover open wounds with clean, dry bandages, and avoid sharing personal items such as towels, razors or uniforms.

In team sports it is also important to exclude players who have potentially infected skin lesions if their wounds can't be covered. Other measures include washing clothes, especially uniforms and exercise gear, in hot water and laundry detergent and drying them in a hot dryer. (For more information on infection prevention techniques, check cdc.gov.)

Such common-sense measures apply to protecting yourself and your children from other kinds of infections as well. In most places where people share facilities or water, bacteria can spread. That resort hot tub may look inviting, but there is always a risk that the others sharing it don't have pristine personal hygiene; so-called recreational water illnesses can cause skin, ear, respiratory, eye, neurologic and wound infections. If you are getting a salon pedicure, don't shave your legs beforehand, because any bacteria in a salon's foot baths, including MRSA, can enter the skin or bloodstream through minor nicks. Ensure that the foot bath basin is thoroughly sanitized, and bring your own equipment, such as clippers.

Rising Threat of Infections Unfazed by Antibiotics

By Andrew Pollack : NY Times Article : February 27, 2010

A minor-league pitcher in his younger days, Richard Armbruster kept playing baseball recreationally into his 70s, until his right hip started bothering him. Last February he went to a St. Louis hospital for what was to be a routine hip replacement.

By late March, Mr. Armbruster, then 78, was dead. After a series of postsurgical complications, the final blow was a bloodstream infection that sent him into shock and resisted treatment with antibiotics.

“Never in my wildest dreams did I think my dad would walk in for a hip replacement and be dead two months later,” said Amy Fix, one of his daughters.

Not until the day Mr. Armbruster died did a laboratory culture identify the organism that had infected him: Acinetobacter baumannii.

The germ is one of a category of bacteria that by some estimates are already killing tens of thousands of hospital patients each year. While the organisms do not receive as much attention as the one known as MRSA — for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus — some infectious-disease specialists say they could emerge as a bigger threat.

That is because there are several drugs, including some approved in the last few years, that can treat MRSA. But for a combination of business reasons and scientific challenges, the pharmaceuticals industry is pursuing very few drugs for Acinetobacter and other organisms of its type, known as Gram-negative bacteria. Meanwhile, the germs are evolving and becoming ever more immune to existing antibiotics.

“In many respects it’s far worse than MRSA,” said Dr. Louis B. Rice, an infectious-disease specialist at the Louis Stokes Cleveland V.A. Medical Center and at Case Western Reserve University. “There are strains out there, and they are becoming more and more common, that are resistant to virtually every antibiotic we have.”

The bacteria, classified as Gram-negative because of their reaction to the so-called Gram stain test, can cause severe pneumonia and infections of the urinary tract, bloodstream and other parts of the body. Their cell structure makes them more difficult to attack with antibiotics than Gram-positive organisms like MRSA.

Acinetobacter, which killed Mr. Armbruster, came to wide attention a few years ago in infections of soldiers wounded in Iraq.

Meanwhile, New York City hospitals, perhaps because of the large numbers of patients they treat, have become the global breeding ground for another drug-resistant Gram-negative germ, Klebsiella pneumoniae.

According to researchers at SUNY Downstate Medical Center, more than 20 percent of the Klebsiella infections in Brooklyn hospitals are now resistant to virtually all modern antibiotics. And those supergerms are now spreading worldwide.

Health authorities do not have good figures on how many infections and deaths in the United States are caused by Gram-negative bacteria. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that roughly 1.7 million hospital-associated infections, from all types of bacteria combined, cause or contribute to 99,000 deaths each year.

But in Europe, where hospital surveys have been conducted, Gram-negative infections are estimated to account for two-thirds of the 25,000 deaths each year caused by some of the most troublesome hospital-acquired infections, according to a report released in September by health authorities there.

To be sure, MRSA remains the single most common source of hospital infections. And it is especially feared because it can also infect people outside the hospital. There have been serious, even deadly, infections of otherwise healthy athletes and school children.

By comparison, the drug-resistant Gram-negative germs for the most part threaten only hospitalized patients whose immune systems are weak. The germs can survive for a long time on surfaces in the hospital and enter the body through wounds, catheters and ventilators.

What is most worrisome about the Gram-negatives is not their frequency but their drug resistance.

“For Gram-positives we need better drugs; for Gram-negatives we need any drugs,” said Dr. Brad Spellberg, an infectious-disease specialist at Harbor-U.C.L.A. Medical Center in Torrance, Calif., and the author of “Rising Plague,” a book about drug-resistant pathogens. Dr. Spellberg is a consultant to some antibiotics companies and has co-founded two companies working on other anti-infective approaches. Dr. Rice of Cleveland has also been a consultant to some pharmaceutical companies.

Doctors treating resistant strains of Gram-negative bacteria are often forced to rely on two similar antibiotics developed in the 1940s — colistin and polymyxin B. These drugs were largely abandoned decades ago because they can cause kidney and nerve damage, but because they have not been used much, bacteria have not had much chance to evolve resistance to them yet.

“You don’t really have much choice,” said Dr. Azza Elemam, an infectious-disease specialist in Louisville, Ky. “If a person has a life-threatening infection, you have to take a risk of causing damage to the kidney.”

Such a tradeoff confronted Kimberly Dozier, a CBS News correspondent who developed an Acinetobacter infection after being injured by a car bomb in 2006 while on assignment in Iraq. After two weeks on colistin, Ms. Dozier’s kidneys began to fail, she recounted in her book, “Breathing the Fire.”

Rejecting one doctor’s advice to go on dialysis and seek a kidney transplant, Ms. Dozier stopped taking the antibiotic to save her kidneys. She eventually recovered from the infection.

Even that dire tradeoff might not be available to some patients. Last year doctors at St. Vincent’s Hospital in Manhattan published a paper describing two cases of “pan-resistant” Klebsiella, untreatable by even the kidney-damaging older antibiotics. One of the patients died and the other eventually recovered on her own, after the antibiotics were stopped.

“It is a rarity for a physician in the developed world to have a patient die of an overwhelming infection for which there are no therapeutic options,” the authors wrote in the journal Clinical Infectious Diseases.

In some cases, antibiotic resistance is spreading to Gram-negative bacteria that can infect people outside the hospital.

Sabiha Khan, 66, went to the emergency room of a Chicago hospital on New Year’s Day suffering from a urinary tract and kidney infection caused by E. coli resistant to the usual oral antibiotics. Instead of being sent home to take pills, Ms. Khan had to stay in the hospital 11 days to receive powerful intravenous antibiotics.

This month, the infection returned, sending her back to the hospital for an additional two weeks.

Some patient advocacy groups say hospitals need to take better steps to prevent such infections, like making sure that health care workers frequently wash their hands and that surfaces and instruments are disinfected. And antibiotics should not be overused, they say, because that contributes to the evolution of resistance.

To encourage prevention, an Atlanta couple, Armando and Victoria Nahum, started the Safe Care Campaign

Joshua, a skydiving instructor in Colorado, had fractured his skull and thigh bone on a hard landing. During his treatment, he twice acquired MRSA and then was infected by Enterobacter aerogenes, a Gram-negative bacterium.

“The MRSA they got rid of with antibiotics,” Mr. Nahum said. “But this one they just couldn’t do anything about" after their 27 year old son Joshua, died from a hospital-acquired infection in October 2006.

By Andrew Pollack : NY Times Article : February 27, 2010

A minor-league pitcher in his younger days, Richard Armbruster kept playing baseball recreationally into his 70s, until his right hip started bothering him. Last February he went to a St. Louis hospital for what was to be a routine hip replacement.

By late March, Mr. Armbruster, then 78, was dead. After a series of postsurgical complications, the final blow was a bloodstream infection that sent him into shock and resisted treatment with antibiotics.

“Never in my wildest dreams did I think my dad would walk in for a hip replacement and be dead two months later,” said Amy Fix, one of his daughters.

Not until the day Mr. Armbruster died did a laboratory culture identify the organism that had infected him: Acinetobacter baumannii.

The germ is one of a category of bacteria that by some estimates are already killing tens of thousands of hospital patients each year. While the organisms do not receive as much attention as the one known as MRSA — for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus — some infectious-disease specialists say they could emerge as a bigger threat.

That is because there are several drugs, including some approved in the last few years, that can treat MRSA. But for a combination of business reasons and scientific challenges, the pharmaceuticals industry is pursuing very few drugs for Acinetobacter and other organisms of its type, known as Gram-negative bacteria. Meanwhile, the germs are evolving and becoming ever more immune to existing antibiotics.

“In many respects it’s far worse than MRSA,” said Dr. Louis B. Rice, an infectious-disease specialist at the Louis Stokes Cleveland V.A. Medical Center and at Case Western Reserve University. “There are strains out there, and they are becoming more and more common, that are resistant to virtually every antibiotic we have.”

The bacteria, classified as Gram-negative because of their reaction to the so-called Gram stain test, can cause severe pneumonia and infections of the urinary tract, bloodstream and other parts of the body. Their cell structure makes them more difficult to attack with antibiotics than Gram-positive organisms like MRSA.

Acinetobacter, which killed Mr. Armbruster, came to wide attention a few years ago in infections of soldiers wounded in Iraq.

Meanwhile, New York City hospitals, perhaps because of the large numbers of patients they treat, have become the global breeding ground for another drug-resistant Gram-negative germ, Klebsiella pneumoniae.

According to researchers at SUNY Downstate Medical Center, more than 20 percent of the Klebsiella infections in Brooklyn hospitals are now resistant to virtually all modern antibiotics. And those supergerms are now spreading worldwide.

Health authorities do not have good figures on how many infections and deaths in the United States are caused by Gram-negative bacteria. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that roughly 1.7 million hospital-associated infections, from all types of bacteria combined, cause or contribute to 99,000 deaths each year.

But in Europe, where hospital surveys have been conducted, Gram-negative infections are estimated to account for two-thirds of the 25,000 deaths each year caused by some of the most troublesome hospital-acquired infections, according to a report released in September by health authorities there.

To be sure, MRSA remains the single most common source of hospital infections. And it is especially feared because it can also infect people outside the hospital. There have been serious, even deadly, infections of otherwise healthy athletes and school children.

By comparison, the drug-resistant Gram-negative germs for the most part threaten only hospitalized patients whose immune systems are weak. The germs can survive for a long time on surfaces in the hospital and enter the body through wounds, catheters and ventilators.

What is most worrisome about the Gram-negatives is not their frequency but their drug resistance.

“For Gram-positives we need better drugs; for Gram-negatives we need any drugs,” said Dr. Brad Spellberg, an infectious-disease specialist at Harbor-U.C.L.A. Medical Center in Torrance, Calif., and the author of “Rising Plague,” a book about drug-resistant pathogens. Dr. Spellberg is a consultant to some antibiotics companies and has co-founded two companies working on other anti-infective approaches. Dr. Rice of Cleveland has also been a consultant to some pharmaceutical companies.

Doctors treating resistant strains of Gram-negative bacteria are often forced to rely on two similar antibiotics developed in the 1940s — colistin and polymyxin B. These drugs were largely abandoned decades ago because they can cause kidney and nerve damage, but because they have not been used much, bacteria have not had much chance to evolve resistance to them yet.

“You don’t really have much choice,” said Dr. Azza Elemam, an infectious-disease specialist in Louisville, Ky. “If a person has a life-threatening infection, you have to take a risk of causing damage to the kidney.”

Such a tradeoff confronted Kimberly Dozier, a CBS News correspondent who developed an Acinetobacter infection after being injured by a car bomb in 2006 while on assignment in Iraq. After two weeks on colistin, Ms. Dozier’s kidneys began to fail, she recounted in her book, “Breathing the Fire.”

Rejecting one doctor’s advice to go on dialysis and seek a kidney transplant, Ms. Dozier stopped taking the antibiotic to save her kidneys. She eventually recovered from the infection.

Even that dire tradeoff might not be available to some patients. Last year doctors at St. Vincent’s Hospital in Manhattan published a paper describing two cases of “pan-resistant” Klebsiella, untreatable by even the kidney-damaging older antibiotics. One of the patients died and the other eventually recovered on her own, after the antibiotics were stopped.

“It is a rarity for a physician in the developed world to have a patient die of an overwhelming infection for which there are no therapeutic options,” the authors wrote in the journal Clinical Infectious Diseases.

In some cases, antibiotic resistance is spreading to Gram-negative bacteria that can infect people outside the hospital.

Sabiha Khan, 66, went to the emergency room of a Chicago hospital on New Year’s Day suffering from a urinary tract and kidney infection caused by E. coli resistant to the usual oral antibiotics. Instead of being sent home to take pills, Ms. Khan had to stay in the hospital 11 days to receive powerful intravenous antibiotics.

This month, the infection returned, sending her back to the hospital for an additional two weeks.

Some patient advocacy groups say hospitals need to take better steps to prevent such infections, like making sure that health care workers frequently wash their hands and that surfaces and instruments are disinfected. And antibiotics should not be overused, they say, because that contributes to the evolution of resistance.

To encourage prevention, an Atlanta couple, Armando and Victoria Nahum, started the Safe Care Campaign

Joshua, a skydiving instructor in Colorado, had fractured his skull and thigh bone on a hard landing. During his treatment, he twice acquired MRSA and then was infected by Enterobacter aerogenes, a Gram-negative bacterium.

“The MRSA they got rid of with antibiotics,” Mr. Nahum said. “But this one they just couldn’t do anything about" after their 27 year old son Joshua, died from a hospital-acquired infection in October 2006.

Remember:

Antibiotics are ineffective against viral infections.

New drug-resistant 'superbug' arrives in Mass.

by Gideon Gil : Boston Globe : September 13, 2010

A person infected with a "superbug" that is sparking fears around the world was treated earlier this year in a Massachusetts hospital, disease trackers said today. The patient had recently traveled from India, a hotspot for the germ, which is immune to many common antibiotics.

The patient was treated at Massachusetts General Hospital and isolated, a measure that prevented the germ from spreading, said Dr. David Hooper, chief of the hospital’s infection control unit.

"You’ve got to always be vigilant," Hooper said. "We are concerned, not alarmed. With good infection control and following guidelines, they can be held at bay."

A medical officer at the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said the Massachusetts patient survived, as did the only other two US patients with infections blamed on the superbug, which appears to have been contained. All three patients developed urinary tract infections that carried a genetic feature that made their cases harder to treat.

Known by the medical shorthand NDM-1 -– it stands for New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase -– the gene allows bacteria to escape some of the strongest antibiotics available, a process known as drug resistance.

"It leaves treating physicians with few treatment options," said Dr. Alex Kallen, a CDC medical officer.

The arrival of NDM-1 in the United States casts a spotlight more widely on the problem of drug-resistant bacteria, which have caused outbreaks in hospitals, gyms, and schools. A germ called MRSA has received the most attention, but it has plenty of company.

"This is just another example of these multidrug-resistant [germs] that we are going to have to come to grips with," said Dr. Alfred DeMaria, top disease tracker for the Massachusetts Department of Public Health.

Global health specialists attending a major meeting of microbiologists and infectious disease doctors in Boston this week said they are particularly concerned about NDM-1 because of its emergence in India. Antibiotics are cheap and available over the counter in South Asia, specialists said, fueling inappropriate use and, consequently, the development of drug resistance. Poor sanitation can further spread NDM-1, which thrives in germs that proliferate in the gut.

"There are certain factors in the Indian subcontinent that are going to make this spread quite widely," said Timothy Walsh, the Cardiff University scientist who helped discover the germ. "It’s very easy for us to forget in the Western world how desperate the conditions are in some of these countries."

The US cases -- the other patients were treated in California and Illinois -- also illustrate how swiftly germs can spread in an era of jet travel. Scattered cases of NDM-1 infections have been reported elsewhere in Asia, as well as in Europe and Canada.

"Slowly, it’s going to be a problem worldwide," said Patrice Nordmann, a French germ specialist. "It's a question of time."

All three of the US patients had been in India, and two underwent medical procedures in hospitals while they were there, Kallen said. The patient treated in Boston was an Indian citizen with cancer who had undergone surgery and chemotherapy in that country before coming to Massachusetts, the CDC physician said.

Neither of the patients who spent time in Indian hospitals is believed to have traveled to that country as part of medical tourism -- the practice of US and European patients going abroad for surgeries that can cost less and happen faster.

Germs with NDM-1 are typically spread through poor hygiene and not by coughing or sneezing, Walsh said. In India, children playing in sewage could potentially be exposed to the superbug.

In the United States, DeMaria said, the threat posed by the germs is most acute in hospitals. "They don’t cause infection in people walking down the street," he said. "If somebody’s in an intensive care unit on a ventilator with a tube in their trachea, they’re at risk for these organisms. If someone has had extensive abdominal surgery with lots of open wounds, they’re at risk."

Only two antibiotics possess a measure of effectiveness against bacteria riddled with NDM-1, doctors said: an old drug called colistin, and tigecycline.

The paucity of drugs reflects not only the strength of the superbug but also the long-neglected development of new antibiotics. While compounds are being studied in labs and some are undergoing human testing, scientists and physicians at the Boston meeting, the Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, expressed little hope that the antibiotic medicine cabinet will expand significantly in coming years.

"There are some antibiotics that have been talked about at this meeting," Walsh said. "Trouble is we’ve got one or two that look promising, and what we need are six to eight to cover our options."

by Gideon Gil : Boston Globe : September 13, 2010

A person infected with a "superbug" that is sparking fears around the world was treated earlier this year in a Massachusetts hospital, disease trackers said today. The patient had recently traveled from India, a hotspot for the germ, which is immune to many common antibiotics.

The patient was treated at Massachusetts General Hospital and isolated, a measure that prevented the germ from spreading, said Dr. David Hooper, chief of the hospital’s infection control unit.

"You’ve got to always be vigilant," Hooper said. "We are concerned, not alarmed. With good infection control and following guidelines, they can be held at bay."

A medical officer at the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said the Massachusetts patient survived, as did the only other two US patients with infections blamed on the superbug, which appears to have been contained. All three patients developed urinary tract infections that carried a genetic feature that made their cases harder to treat.

Known by the medical shorthand NDM-1 -– it stands for New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase -– the gene allows bacteria to escape some of the strongest antibiotics available, a process known as drug resistance.

"It leaves treating physicians with few treatment options," said Dr. Alex Kallen, a CDC medical officer.

The arrival of NDM-1 in the United States casts a spotlight more widely on the problem of drug-resistant bacteria, which have caused outbreaks in hospitals, gyms, and schools. A germ called MRSA has received the most attention, but it has plenty of company.

"This is just another example of these multidrug-resistant [germs] that we are going to have to come to grips with," said Dr. Alfred DeMaria, top disease tracker for the Massachusetts Department of Public Health.

Global health specialists attending a major meeting of microbiologists and infectious disease doctors in Boston this week said they are particularly concerned about NDM-1 because of its emergence in India. Antibiotics are cheap and available over the counter in South Asia, specialists said, fueling inappropriate use and, consequently, the development of drug resistance. Poor sanitation can further spread NDM-1, which thrives in germs that proliferate in the gut.

"There are certain factors in the Indian subcontinent that are going to make this spread quite widely," said Timothy Walsh, the Cardiff University scientist who helped discover the germ. "It’s very easy for us to forget in the Western world how desperate the conditions are in some of these countries."

The US cases -- the other patients were treated in California and Illinois -- also illustrate how swiftly germs can spread in an era of jet travel. Scattered cases of NDM-1 infections have been reported elsewhere in Asia, as well as in Europe and Canada.

"Slowly, it’s going to be a problem worldwide," said Patrice Nordmann, a French germ specialist. "It's a question of time."

All three of the US patients had been in India, and two underwent medical procedures in hospitals while they were there, Kallen said. The patient treated in Boston was an Indian citizen with cancer who had undergone surgery and chemotherapy in that country before coming to Massachusetts, the CDC physician said.

Neither of the patients who spent time in Indian hospitals is believed to have traveled to that country as part of medical tourism -- the practice of US and European patients going abroad for surgeries that can cost less and happen faster.

Germs with NDM-1 are typically spread through poor hygiene and not by coughing or sneezing, Walsh said. In India, children playing in sewage could potentially be exposed to the superbug.

In the United States, DeMaria said, the threat posed by the germs is most acute in hospitals. "They don’t cause infection in people walking down the street," he said. "If somebody’s in an intensive care unit on a ventilator with a tube in their trachea, they’re at risk for these organisms. If someone has had extensive abdominal surgery with lots of open wounds, they’re at risk."

Only two antibiotics possess a measure of effectiveness against bacteria riddled with NDM-1, doctors said: an old drug called colistin, and tigecycline.

The paucity of drugs reflects not only the strength of the superbug but also the long-neglected development of new antibiotics. While compounds are being studied in labs and some are undergoing human testing, scientists and physicians at the Boston meeting, the Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, expressed little hope that the antibiotic medicine cabinet will expand significantly in coming years.

"There are some antibiotics that have been talked about at this meeting," Walsh said. "Trouble is we’ve got one or two that look promising, and what we need are six to eight to cover our options."

A Guide to Smarter, Safer Antibiotic Use

By Jane E. Brody : NY Times : March 21, 2011

Antibiotics are important drugs, perhaps the most important. In a world beset with “an unprecedented wave of new and old infections,” as one expert recently wrote, it is critically important that antibiotics work well when people need them.

But antibiotics are frequently misused — overprescribed or incorrectly taken by patients, and recklessly fed to farm animals. As a result, lifesaving antibacterial drugs lose effectiveness faster than new ones are developed to replace them.

Each year, 100,000 people in the United States die from hospital-acquired infections that are resistant to antibiotics, according to the Infectious Diseases Society of America.

These concerns led Dr. Zelalem Temesgen, an infectious disease specialist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., to create a 15-part “Symposium on Antimicrobial Therapy,” published in February in The Mayo Clinic Proceedings. The series is intended in part to help practicing physicians know when and how antibiotics should be used — and, equally important, when they should not.

Improving how antibiotics are prescribed can do more than curb resistance. It can save lives and money by reducing adverse drug reactions and eliminating or shortening hospital stays, Dr. Temesgen said.

The first installment in the series, based on guidelines developed by the infectious diseases society and published with Dr. Temesgen’s introduction, was devoted to helping doctors practice better medicine. It also can help patients better understand how and when antibiotics work best, and it can arm them with the right questions when an antibiotic prescription is being considered.

Patient-Tailored Therapy

The report, prepared by three infectious disease specialists — Surbhi Leekha, now at the University of Maryland, and Drs. Christine L. Terrell and Randall S. Edson, both at the Mayo Clinic — urged doctors to avoid a “one size fits all” approach to antibiotics. Rather, they said, many individual factors must be taken into account to ensure the right drug and the right dose are prescribed for each patient.

It is often up to the patient to make sure the prescribing physician is aware of these influential factors. They include:

Kidney and liver function.

The kidneys and liver eliminate drugs from the body. If the organs are not working well, toxic levels can accumulate in the bloodstream.

Age.

Considering a new antibiotic? This is no time lie about your age. “Patients at both extremes of age handle drugs differently, primarily due to differences in body size and kidney function,” the experts wrote. A face-lift and hair coloring may disguise your geriatric status, but they will not help your kidneys process drugs as well as they did in your youth. In some cases, in young, otherwise healthy patients, higher drug doses may be needed to be sure that therapeutic levels are maintained.

Pregnancy and nursing.

Some antibiotics given to a pregnant or lactating woman can adversely affect her baby, and it is critically important to tell the prescribing doctor if you are pregnant (or might be pregnant) or nursing. The risk of drug-induced birth defects is highest in the first three months of pregnancy; during the last three months, drugs are eliminated from the body more quickly, and higher doses may be needed to maintain a therapeutic blood level.

Drug allergy or intolerance.

Make sure the doctor knows if you have ever had a bad reaction to an antibiotic. But — and this is important — neither you nor your doctor should assume you are allergic to, for example, penicillin because you once developed a rash while taking it. The rash could have been caused by the illness or something else entirely.

When an allergy is suspected, a skin test should be performed to confirm it so that the ideal antibiotic treatment is not mistakenly ruled out in the future.

“It has been shown that only 10 percent to 20 percent of patients reporting a history of penicillin allergy were truly allergic when assessed by skin testing,” the experts wrote.

In an interview, Dr. Edson said it is possible to rapidly desensitize a patient to a needed antibiotic by administering progressively larger oral doses of the drug.

Recent antibiotic use.

Tell the doctor if you recently took an antibiotic. If you develop a bacterial illness within three months of antibiotic therapy, you may have a drug-resistant infection that requires use of an alternate class of medication.

Genetic characteristics.

Some people are born with factors that make them especially vulnerable to bad reactions from certain antibiotics. For example, in those with a condition known as G6PD deficiency, which is most common among blacks, certain antibiotics can lead to the destruction of red blood cells. Patients who could be at risk should be tested for G6PD deficiency beforehand.

The Value of a Culture

When patients arrive at the doctor’s office with an inflamed throat, deep cough, high fever or unrelenting sinus pain, more often than not they are given prescriptions for antibiotics. The experts noted that it is sometimes reasonable to treat an infection without first getting a culture of the responsible organism — like when the patient’s symptoms are typical of a known bacterial infection.

“Doctors do have to exercise clinical judgment in many cases,” Dr. Edson said. For example, he and his co-authors wrote, “Cellulitis is most frequently assumed to be caused by streptococci or staphylococci, and antibacterial treatment can be administered in the absence of a positive culture.”

Likewise, they added, community-acquired pneumonia (that is, pneumonia that develops somewhere other than a hospital) can be treated with an antibiotic without patients first receiving a diagnostic test.

But all too often, the cause of a patient’s symptoms is not bacterial and may not even be an infection. In these cases, taking an antibiotic will do no good and may even be harmful. Possible nonbacterial causes include a viral infection (which will not respond to an antibiotic), a connective tissue disorder or an allergy, Dr. Edson said.

He and his co-authors emphasized the importance of getting a laboratory to identify the responsible organism when the likely cause of symptoms is not apparent or when patients have a serious or life-threatening infection, require long-term antibiotic therapy or fail to benefit from the drug chosen initially.

Sometimes a culture will indicate the need to administer two antibiotics simultaneously — for example, when the infectious organism produces an enzyme that inactivates what would otherwise be the most effective antibacterial drug.

The experts also urged that if patients were first treated with a broad-spectrum antibiotic (one that attacks a number of different bacteria), doctors should consider switching to a narrow-spectrum drug that targets the specific cause once it is identified through a laboratory culture. This could reduce the risk of other bacteria becoming resistant to the broad-spectrum drug.

"Superbugs"

Misuse of antibiotics has led to a global health threat: the rise of dangerous—or even fatal—superbugs. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is now attacking both patients in hospitals and also in the community and a deadly new multi-drug resistant bacteria called carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae, or CRKP is now in the headlines. Last year, antibiotic resistant infections killed 25,000 people in Europe, the Guardian reports.

Unless steps are taken to address this crisis, the cures doctors have counted on to battle bacteria will soon be useless. CRKP has now been reported in 36 US states—and health officials suspect that it may also be triggering infections in the other 14 states where reporting isn’t required. High rates have been found in long-term care facilities in Los Angeles County, where the superbug was previously believed to be rare, according to a study presented earlier this month. CRKP is even scarier than MRSA because the new superbug is resistant to almost all antibiotics, while a few types of antibiotics still work on MRSA. Who’s at risk for superbugs—and what can you do to protect yourself and family members? Here’s a guide to these dangerous bacteria.

What is antibiotic resistance?

Almost every type of bacteria has evolved and mutated to become less and less responsive to common antibiotics, largely due to overuse of these medications. Because superbugs are resistant to these drugs, they can quickly spread in hospitals and the community, causing infections that are hard or even impossible to cure. Doctors are forced to turn to more expensive and sometimes more toxic drugs of last resort. The problem is that every time antibiotics are used, some bacteria survive, giving rise to dangerous new strains like MRSA and CRKP, the CDC reports.

What are CRKP and MRSA?

Klebseiella is a common type of gram-negative bacteria that are found in our intestines (where the bugs don’t cause disease). The CRKP strain is resistant to almost all antibiotics, including carbapenems, the so-called “antibiotics of last resort.” MRSA (methacillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus) is a type of bacteria that live on the skin and can burrow deep into the body if someone has cuts or wounds, including those from surgery.

Who is at risk?

CRKP and MRSA infects patients, usually the elderly—who are already ill and living in long-term healthcare facilities, such as nursing homes. People who are on ventilators, require IVs, or have undergone prolonged treatment with certain antibiotics face the greatest threat of CRKP infection. Healthy people are at very low risk for CRKP. There are 2 types of MRSA, a form that affects hospital patients, with similar risk factors to CRKP, and another even more frightening strain found in communities, attacking people of all ages who have not been in medical facilities, including athletes, weekend warriors who use locker rooms, kids in daycare centers, soldiers, and people who get tattoos. Nearly 500,000 people a year are hospitalized with MRSA.

How likely is it to be fatal?

In earlier outbreaks, 35 percent of CRKP-infected patients died, Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) reported in 2008. The death rate among those affected by the current outbreak isn’t yet known. About 19,000 deaths a year are linked to MRSA in the US and rates of the disease has rise 10-fold, with most infections found in the community.

How does it spread?

Both MRSA and CRKP are mainly transmitted by person-to-person contact, such as the infected hands of a healthcare provider. They can enter the lungs through a ventilator, causing pneumonia, the bloodstream through an IV catheter, causing bloodstream infection (sepsis), or the urinary tract through a catheter, causing a urinary tract infection. Both can also cause surgical wounds to become infected. MRSA can also be spread in contact with infected items, such as sharing razors, clothing, and sports equipment. These superbugs are not spread through the air.

What are the symptoms?

Since CRKP presents itself as a variety of illnesses, most commonly pneumonia, meningitis, urinary tract infections, wound (or surgical site) infections and blood infections, symptoms reflect those illnesses, most often pneumonia. MRSA typically causes boils and abscesses that resemble infected bug bites, but can also present as pneumonia or flu-like symptoms.

How are superbugs related?

The only drug that still works against the CRKP is colistin, a toxic antibiotic that can damage the kidneys. Several drugs, such as vancomycin, may still work against MRSA.

What’s the best protection against superbugs?

Healthcare providers are prescribing fewer antibiotics, to help prevent CRKP, MRSA and other superbugs from developing resistance to even more antibiotics. The best way to stop bacteria from spreading is simple hygiene. If someone you know is in a nursing home or hospital, make sure doctors and staff wash their hands in front of you. Also wash your own hands frequently, with soap and water or an alcohol-based hand sanitizer, avoid sharing personal items, and shower after using gym equipment.

Misuse of antibiotics has led to a global health threat: the rise of dangerous—or even fatal—superbugs. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is now attacking both patients in hospitals and also in the community and a deadly new multi-drug resistant bacteria called carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae, or CRKP is now in the headlines. Last year, antibiotic resistant infections killed 25,000 people in Europe, the Guardian reports.