- RETIREMENT ANNOUNCEMENT

- HOME PAGE

- "MYCHART" the new patient portal

- BELMONT MEDICAL ASSOCIATES

- MOUNT AUBURN HOSPITAL

- EMERGENCIES

- PRACTICE PHILOSOPHY

- MY RESUME

- TELEMEDICINE CONSULTATION

- CONTACT ME

- LAB RESULTS

- ePRESCRIPTIONS

- eREFERRALS

- RECORD RELEASE

- MEDICAL SCRIBE

- PHYSICIAN ASSISTANT (PA)

- Medicare Annual Wellness Visit

- Case management/Social work

- Quality Care Measures

- Emergency closing notice

- FEEDBACK

- Talking to your doctor

- Choosing..... and losing a doctor

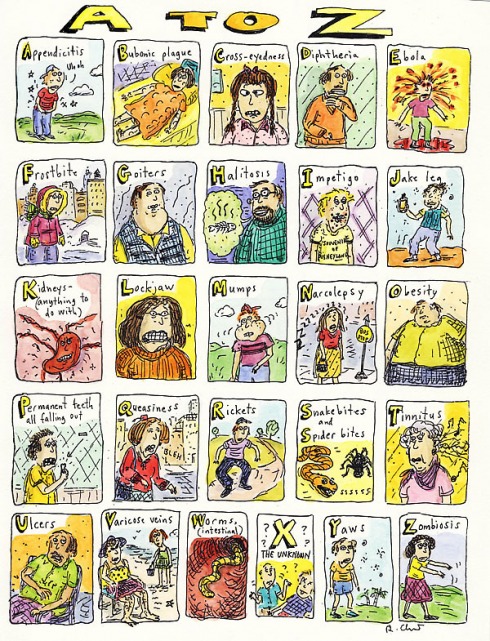

- INDEX A - Z

- ALLERGIC REACTIONS

- Alternative Medicine

- Alzheimer's Disease

- Bladder Problems

- Blood disorders

- Cancer Concerns

- GENETIC TESTING FOR HEREDITARY CANCER

- Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

- Controversial Concerns

- CPR : Learn and save a life

- CRP : Inflammatory marker

- Diabetes Management

- Dizziness, Vertigo,Tinnitus and Hearing Loss

- EXERCISE

- FEMALE HEALTH

-

GASTROINTESTINAL topics

- Appendicitis

- BRAT diet

- Celiac Disease or Sprue

- Crohn's Disease

- Gastroenterologists for Colon Cancer Screening

- Colonoscopy PREP

- Constipation

- Gluten sensitivity, but not celiac disease

- Heartburn and GERD

- Hemorrhoids and Anal fissure

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- NASH : Non Alcoholic Steato Hepatitis

- FEET PROBLEMS

- HEART RELATED topics

-

INFECTIOUS DISEASES

- Antibiotic Resistance

- Cat bites >

- Clostridia difficile infection - the "antibiotic associated germ"

- CORONA VIRUS

- Dengue Fever and Chikungunya Fever

- Food borne illnesses

- Shingles Vaccine

- Hepatitis B

- Hepatitis C

- Herpes

- Influenza

- Helicobacter pylori - the "ulcer germ"

- HIV Screening

- Lyme and other tick borne diseases

- Measles

- Meningitis

- MRSA (Staph infection)

- Norovirus

- Sexually Transmitted Diseases

- Shingles (Herpes Zoster)

- Sinusitis

- West Nile Virus

- Whooping Cough (Pertussis)

- Zika virus and pregnancy

- INSURANCE related topics

- KIDNEY STONES

- LEG CRAMPS

- LIBRARY for patients

- LIFE DECISIONS

- MALE HEALTH

- Medication/Drug side effects

- MEDICAL MARIJUANA

- MENTAL HEALTH

- Miscellaneous Articles

-

NUTRITION - EXERCISE - WEIGHT

- Cholesterol : New guidelines for treatment

- Advice to lower your cholesterol

- Cholesterol : Control

- Cholesterol : Raising your HDL Level

- Exercise

- Food : Making Smart Choices

- Food : Making Poor Choices

- Food : Grape Fruit and Drug Interaction

- Food : Vitamins, Minerals and Supplements

- Omega 3 fatty acids

- Vitamin B12 deficiency

- Vitamin D

- Weight Loss

- ORTHOPEDICS

- PAIN

- PATIENTS' RIGHTS

- SKIN

- SLEEP

- SMOKING

- STROKE

- THYROID

- SUBSTANCE ABUSE

- Travel and Vaccination

- TREMOR

- Warfarin Anticoagulation

- OTHER STUFF FOLLOWS

- Fact or Opinion?

- Hippocratic Oath

- FREE ADVICE.......for what its worth!

- LAUGHTER.....is the best medicine

- Physicians Pet Peeves

- PHOTO ALBUM - its not all work!

- Cape Town, South Africa

- Tribute page

- The 100 Club

- Free Wi-Fi

Sleep

To Rest Easy, Forget the Sheep

Scientists know that many people inadvertently undermine their ability to fall asleep and stay asleep for a full night. Here are some frequent suggestions:

1. Establish a regular sleep schedule and try to stick to it, even on weekends.

2. If you nap during the day, limit it to 20 or 30 minutes, preferably early in the afternoon.

3. Avoid alcohol in the evening, as it can disrupt sleep.

4. Don’t eat a big meal just before bedtime, but don’t go to bed hungry, either. Eat a light snack before bed, if needed, preferably one high in carbohydrates.

5. If you use medications that are stimulants, take them in the morning, or ask your doctor if you can switch to a nonstimulating alternative. If you use drugs that cause drowsiness, take them in the evening.

6. Get regular exercise during the day, but avoid vigorous exercise within three hours of bedtime.

7. If pressing thoughts interfere with falling asleep, write them down (keep a pad and pen next to the bed) and try to forget about them until morning.

8. If you are frequently awakened by a need to use the bathroom, cut down on how much you drink late in the day.

9. If you smoke, quit. Among other hazards, nicotine is a stimulant and can cause nightmares.

10. Avoid beverages and foods containing caffeine after 3 p.m. Even decaf versions have some caffeine, which can bother some people.

Cheating Ourselves of Sleep

By Jane E. Brody : NY Times : June 17, 2013

Think you do just fine on five or six hours of shut-eye? Chances are, you are among the many millions who unwittingly shortchange themselves on sleep.

Research shows that most people require seven or eight hours of sleep to function optimally. Failing to get enough sleep night after night can compromise your health and may even shorten your life. From infancy to old age, the effects of inadequate sleep can profoundly affect memory, learning, creativity, productivity and emotional stability, as well as your physical health.

According to sleep specialists at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine and Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic, among others, a number of bodily systems are negatively affected by inadequate sleep: the heart, lungs and kidneys; appetite, metabolism and weight control; immune function and disease resistance; sensitivity to pain; reaction time; mood; and brain function.

Poor sleep is also a risk factor for depression and substance abuse, especially among people with post-traumatic stress disorder, according to Anne Germain, associate professor of psychiatry at the University of Pittsburgh. People with PTSD tend to relive their trauma when they try to sleep, which keeps their brains in a heightened state of alertness.

Dr. Germain is studying what happens in the brains of sleeping veterans with PTSD in hopes of developing more effective treatments for them and for people with lesser degrees of stress that interfere with a good night’s sleep.

The elderly are especially vulnerable. Timothy H. Monk, who directs the Human Chronobiology Research Program at Western Psychiatric, heads a five-year federally funded study of circadian rhythms, sleep strength, stress reactivity, brain function and genetics among the elderly. “The circadian signal isn’t as strong as people get older,” he said.

He is finding that many are helped by standard behavioral treatments for insomnia, like maintaining a regular sleep schedule, avoiding late-in-day naps and caffeine, and reducing distractions from light, noise and pets.

It should come as no surprise that myriad bodily systems can be harmed by chronically shortened nights. “Sleep affects almost every tissue in our bodies,” said Dr. Michael J. Twery, a sleep specialist at the National Institutes of Health.

Several studies have linked insufficient sleep to weight gain. Not only do night owls with shortchanged sleep have more time to eat, drink and snack, but levels of the hormone leptin, which tells the brain enough food has been consumed, are lower in the sleep-deprived while levels of ghrelin, which stimulates appetite, are higher.

In addition, metabolism slows when one’s circadian rhythm and sleep are disrupted; if not counteracted by increased exercise or reduced caloric intake, this slowdown could add up to 10 extra pounds in a year.

The body’s ability to process glucose is also adversely affected, which may ultimately result in Type 2 diabetes. In one study, healthy young men prevented from sleeping more than four hours a night for six nights in a row ended up with insulin and blood sugar levels like those of people deemed prediabetic. The risks of cardiovascular diseases and stroke are higher in people who sleep less than six hours a night. Even a single night of inadequate sleep can cause daylong elevations in blood pressure in people with hypertension. Inadequate sleep is also associated with calcification of coronary arteries and raised levels of inflammatory factors linked to heart disease. (In terms of cardiovascular disease, sleeping too much may also be risky. Higher rates of heart disease have been found among women who sleep more than nine hours nightly.)

The risk of cancer may also be elevated in people who fail to get enough sleep. A Japanese study of nearly 24,000 women ages 40 to 79 found that those who slept less than six hours a night were more likely to develop breast cancer than women who slept longer. The increased risk may result from diminished secretion of the sleep hormone melatonin. Among participants in the Nurses Health Study, Eva S. Schernhammer of Harvard Medical School found a link between low melatonin levels and an increased risk of breast cancer.

A study of 1,240 people by researchers at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland found an increased risk of potentially cancerous colorectal polyps in those who slept fewer than six hours nightly.

Children can also experience hormonal disruptions from inadequate sleep. Growth hormone is released during deep sleep; it not only stimulates growth in children, but also boosts muscle mass and repairs damaged cells and tissues in both children and adults.

Dr. Vatsal G. Thakkar, a psychiatrist affiliated with New York University, recently described evidence associating inadequate sleep with an erroneous diagnosis of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children. In one study, 28 percent of children with sleep problems had symptoms of the disorder, but not the disorder.

During sleep, the body produces cytokines, cellular hormones that help fight infections. Thus, short sleepers may be more susceptible to everyday infections like colds and flu. In a study of 153 healthy men and women, Sheldon Cohen and colleagues at Carnegie Mellon University found that those who slept less than seven hours a night were three times as likely to develop cold symptoms when exposed to a cold-causing virus than were people who slept eight or more hours.

Some of the most insidious effects of too little sleep involve mental processes like learning, memory, judgment and problem-solving. During sleep, new learning and memory pathways become encoded in the brain, and adequate sleep is necessary for those pathways to work optimally. People who are well rested are better able to learn a task and more likely to remember what they learned. The cognitive decline that so often accompanies aging may in part result from chronically poor sleep.

With insufficient sleep, thinking slows, it is harder to focus and pay attention, and people are more likely to make poor decisions and take undue risks. As you might guess, these effects can be disastrous when operating a motor vehicle or dangerous machine.

In driving tests, sleep-deprived people perform as if drunk, and no amount of caffeine or cold air can negate the ill effects.

At your next health checkup, tell your doctor how long and how well you sleep. Be honest: Sleep duration and quality can be as important to your health as your blood pressure and cholesterol level.

This is the first of two columns on inadequate sleep.

Why We Need Our Sleep

By Robert Lee Hotz : WSJ Article : January 18, 2008

People have been trying to figure out why we sleep for almost as long as we have been conscious of being awake, tossing and turning in the dark.

After a few restless nights, most of us can't even think straight. We are less able to make sense of problems, make competent moral judgments or retain what we learn, even though studies show our brain cells fire more frenetically to overcome the lack of sleep. Lose too much sleep and we become reckless, emotionally fragile and more vulnerable to infections as well as diabetes, heart disease and obesity, recent research suggests.

Yet scientists probing the purpose of sleep are still largely in the dark. "Why we sleep at all is a strange bastion of the unknown," said sleep psychologist Matthew Walker at the University of California in Berkeley.

One vital function of sleep, researchers argue, may be to help our brains sort, store and consolidate new memories, etching experiences more indelibly into the brain's biochemical archives.

.

Even a 90-minute nap can significantly improve our ability to master new motor skills and strengthen our memories of what we learn, researchers at the University of Haifa in Israel reported last month in Nature Neuroscience. "Napping is as effective as a night's sleep," said psychologist Sara Mednick at the University of California in San Diego.

Moreover, slumber seems to boost our ability to make sense of new knowledge by allowing the brain to detect connections between things we learn.

In research published in April in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Dr. Walker and his collaborators at the Harvard Medical School tested 56 college students and found that their ability to discern the big picture in disparate pieces of information improved measurably after the brain could, during a night's sleep, mull things over.

It is these patterns of meaning -- the distilled essence of knowledge -- that we remember so well. "Sleep helps stabilize memory," said neurologist Jeffrey Ellenbogen, director of the sleep-medicine program at Massachusetts General Hospital.

The erratic biorhythms of sleep and behavior are intertwined everywhere in nature. Socially active fruit flies need more sleep than loner flies, and even zebra fish can get insomnia.

Sleep is controlled partly by our genes. The difference between those of us who naturally wake at dawn and night owls who are wide-eyed at midnight may be partly due to variations in a gene, named Period3, that affects our biological clock. Variations in that gene also make some people especially sensitive to sleep deprivation, scientists at the U.K.'s University of Surrey recently reported.

For many of us, though, sleeplessness is a self-inflicted epidemic in which lifestyle overrides basic biology. "In this odd, Western 24-hour-MTV-fast-food generation we have created, we all feel the need to achieve more and more. The one thing that takes a hit is sleep," Dr. Walker said. On average, most people sleep 75 minutes less each night than people did a century ago, sleep surveys record.

Yet, rarely have so many millions of drowsy people been trying so hard to secure some shut-eye, spending billions on sleep aids. By one estimate, in the U.S. alone, pharmacists filled 49 million prescriptions for sleep drugs last year. Even so, we think we sleep more than we actually do, according to Arizona State University scientists. They recorded how long 2,100 volunteers actually slept each night and compared that to how long the people reported they had slept. Most people overestimated their sleep by about 18 minutes, the scientists found.

The consequences of too little sleep can be dire. Almost half of all heavy-truck accidents in the U.S. can be traced to driver fatigue, while decisions leading to the Challenger space-shuttle disaster, the Chernobyl nuclear-reactor meltdown and the Exxon Valdez oil spill can be partly linked to people drained of rest by round-the-clock work schedules. Weary doctors make more serious medical errors, while sleepy airport baggage screeners make more security mistakes, researchers reported at the Associated Professional Sleep Societies.

All told, the frayed tempers, short attention spans and fuzzy thinking caused by sleep deprivation may cost $15 billion a year in reduced productivity, the National Commission on Sleep Disorders Research estimated.

The expectation of a nap, however, is by itself enough to measurably lower our blood pressure, researchers at the Liverpool John Moores University in England reported in October in the Journal of Applied Physiology.

Indeed, regular nappers -- working men who took a siesta for 30 minutes or more at least three times a week -- had a 64% lower risk of heart-related death, researchers at the University of Athens reported last February in the Archives of Internal Medicine.

"All of the things we are proving about sleep and the brain are things that your mother already knew decades ago," Dr. Walker said. "We are putting the science and the hard facts behind it."

A Good Night’s Sleep Isn’t a Luxury; It’s a Necessity

By Jane E. Brody : NY Times : May 30, 2011

In my younger years, I regarded sleep as a necessary evil, nature’s way of thwarting my desire to cram as many activities into a 24-hour day as possible. I frequently flew the red-eye from California, for instance, sailing (or so I thought) through the next day on less than four hours of uncomfortable sleep.

But my neglect was costing me in ways that I did not fully appreciate. My husband called our nights at the ballet and theater “Jane’s most expensive naps.” Eventually we relinquished our subscriptions. Driving, too, was dicey: twice I fell asleep at the wheel, narrowly avoiding disaster. I realize now that I was living in a state of chronic sleep deprivation.

I don’t want to nod off during cultural events, and I no longer have my husband to spell me at the wheel. I also don’t want to compromise my ability to think and react. As research cited recently in this newspaper’s magazine found, “The sleep-deprived among us are lousy judges of our own sleep needs. We are not nearly as sharp as we think we are.”

Studies have shown that people function best after seven to eight hours of sleep, so I now aim for a solid seven hours, the amount associated with the lowest mortality rate. Yet on most nights something seems to interfere, keeping me up later than my intended lights-out at 10 p.m. — an essential household task, an e-mail requiring an urgent and thoughtful response, a condolence letter I never found time to write during the day, a long article that I must read.

It’s always something.

What’s Keeping Us Up?

I know I’m hardly alone. Between 1960 and 2010, the average night’s sleep for adults in the United States dropped to six and a half hours from more than eight. Some experts predict a continuing decline, thanks to distractions like e-mail, instant and text messaging, and online shopping.

Age can have a detrimental effect on sleep. In a 2005 national telephone survey of 1,003 adults ages 50 and older, the Gallup Organization found that a mere third of older adults got a good night’s sleep every day, fewer than half slept more than seven hours, and one-fifth slept less than six hours a night.

With advancing age, natural changes in sleep quality occur. People may take longer to fall asleep, and they tend to get sleepy earlier in the evening and to awaken earlier in the morning. More time is spent in the lighter stages of sleep and less in restorative deep sleep. R.E.M. sleep, during which the mind processes emotions and memories and relieves stress, also declines with age.

Habits that ruin sleep often accompany aging: less physical activity, less time spent outdoors (sunlight is the body’s main regulator of sleepiness and wakefulness), poorer attention to diet, taking medications that can disrupt sleep, caring for a chronically ill spouse, having a partner who snores. Some use alcohol in hopes of inducing sleep; in fact, it disrupts sleep.

Add to this list a host of sleep-robbing health issues, like painful arthritis, diabetes, depression, anxiety, sleep apnea, hot flashes in women and prostate enlargement in men. In the last years of his life, my husband was plagued with restless leg syndrome, forcing him to get up and walk around in the middle of the night until the symptoms subsided. During a recent night, I was awake for hours with leg cramps that simply wouldn’t quit.

Beauty Rest and Beyond

A good night’s sleep is much more than a luxury. Its benefits include improvements in concentration, short-term memory, productivity, mood, sensitivity to pain and immune function.

If you care about how you look, more sleep can even make you appear more attractive. In a study published online in December in the journal BMJ, researchers in Sweden and the Netherlands reported that 23 sleep-deprived adults seemed to untrained observers to be less healthy, more tired and less attractive than they appeared to be after a full night’s sleep.

Perhaps more important, losing sleep may make you fat — or at least, fatter than you would otherwise be. In a study by Harvard researchers involving 68,000 middle-aged women followed for 16 years, those who slept five hours or less each night were found to weigh 5.4 pounds more — and were 15 percent more likely to become obese — than the women who slept seven hours nightly.

Michael Breus, a clinical psychologist and sleep specialist in Scottsdale, Ariz., and author of “The Sleep Doctor’s Diet Plan,” points out that as the average length of sleep has declined in the United States, the average weight of Americans has increased.

There are plausible reasons to think this is a cause-and-effect relationship. At least two factors may be involved: more waking hours in homes brimming with food and snacks; and possible changes in the hormones leptin and ghrelin, which regulate appetite.

In a study published in 2009 in The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, Dr. Plamen D. Penev, an endocrinologist at the University of Chicago, and co-authors explored calorie consumption and expenditure by 11 healthy volunteers who spent two 14-day stays in a sleep laboratory. Both sessions offered unlimited access to tasty foods. During one stay, the volunteers — five women and six men — were limited to 5.5 hours of sleep a night, and during the other they got 8.5 hours of sleep.

Although the subjects ate the same amount of food at meals, during the shortened nights they consumed an average of 221 more calories from snacks than they did when they were getting more sleep. The snacks they ate tended to be high in carbohydrates, and the subjects expended no more energy than they did on the longer nights. In just two weeks, the extra nighttime snacking could add nearly a pound to body weight, the scientists concluded.

These researchers found no significant changes in the participants’ blood levels of the hormones leptin and ghrelin, but others have found that short sleepers have lower levels of appetite-suppressing leptin and higher levels of ghrelin, which prompts an increase in calorie intake.

Sleep loss may also affect the function of a group of neurons in the hypothalamus of the brain, where another hormone, orexin, is involved in the regulation of feeding behavior.

The bottom line: Resist the temptation to squeeze one more thing into the end of your day. If health problems disrupt your sleep, seek treatment that can lessen their effect. If you have trouble falling asleep or often awaken during the night and can’t get back to sleep, you could try taking supplements of melatonin, the body’s natural sleep inducer. I keep it at my bedside.

If you have trouble sleeping, the tips accompanying this article may help. And if all else fails, try to take a nap during the day. Naps can enhance brain function, energy, mood and productivity.

Brain Basics:

Understanding Sleep

Do you ever feel sleepy or "zone out" during the day? Do you find it hard to wake up on Monday mornings? If so, you are familiar with the powerful need for sleep. However, you may not realize that sleep is as essential for your well-being as food and water.

Until the 1950s, most people thought of sleep as a passive, dormant part of our daily lives. We now know that our brains are very active during sleep. Moreover, sleep affects our daily functioning and our physical and mental health in many ways that we are just beginning to understand.

Nerve-signaling chemicals called neurotransmitters control whether we are asleep or awake by acting on different groups of nerve cells, or neurons, in the brain. Neurons in the brainstem, which connects the brain with the spinal cord, produce neurotransmitters such as serotonin and norepinephrine that keep some parts of the brain active while we are awake. Other neurons at the base of the brain begin signaling when we fall asleep. These neurons appear to "switch off" the signals that keep us awake. Research also suggests that a chemical called adenosine builds up in our blood while we are awake and causes drowsiness. This chemical gradually breaks down while we sleep.

During sleep, we usually pass through five phases of sleep: stages 1, 2, 3, 4, and REM (rapid eye movement) sleep. These stages progress in a cycle from stage 1 to REM sleep, then the cycle starts over again with stage 1 (see figure 1 ). We spend almost 50 percent of our total sleep time in stage 2 sleep, about 20 percent in REM sleep, and the remaining 30 percent in the other stages. Infants, by contrast, spend about half of their sleep time in REM sleep.

During stage 1, which is light sleep, we drift in and out of sleep and can be awakened easily. Our eyes move very slowly and muscle activity slows. People awakened from stage 1 sleep often remember fragmented visual images. Many also experience sudden muscle contractions called hypnic myoclonia, often preceded by a sensation of starting to fall. These sudden movements are similar to the "jump" we make when startled. When we enter stage 2 sleep, our eye movements stop and our brain waves (fluctuations of electrical activity that can be measured by electrodes) become slower, with occasional bursts of rapid waves called sleep spindles. In stage 3, extremely slow brain waves called delta waves begin to appear, interspersed with smaller, faster waves. By stage 4, the brain produces delta waves almost exclusively. It is very difficult to wake someone during stages 3 and 4, which together are called deep sleep. There is no eye movement or muscle activity. People awakened during deep sleep do not adjust immediately and often feel groggy and disoriented for several minutes after they wake up. Some children experience bedwetting, night terrors, or sleepwalking during deep sleep.

When we switch into REM sleep, our breathing becomes more rapid, irregular, and shallow, our eyes jerk rapidly in various directions, and our limb muscles become temporarily paralyzed. Our heart rate increases, our blood pressure rises, and males develop penile erections. When people awaken during REM sleep, they often describe bizarre and illogical tales – dreams.

The first REM sleep period usually occurs about 70 to 90 minutes after we fall asleep. A complete sleep cycle takes 90 to 110 minutes on average. The first sleep cycles each night contain relatively short REM periods and long periods of deep sleep. As the night progresses, REM sleep periods increase in length while deep sleep decreases. By morning, people spend nearly all their sleep time in stages 1, 2, and REM.

People awakened after sleeping more than a few minutes are usually unable to recall the last few minutes before they fell asleep. This sleep-related form of amnesia is the reason people often forget telephone calls or conversations they've had in the middle of the night. It also explains why we often do not remember our alarms ringing in the morning if we go right back to sleep after turning them off.

Since sleep and wakefulness are influenced by different neurotransmitter signals in the brain, foods and medicines that change the balance of these signals affect whether we feel alert or drowsy and how well we sleep. Caffeinated drinks such as coffee and drugs such as diet pills and decongestants stimulate some parts of the brain and can cause insomnia, or an inability to sleep. Many antidepressants suppress REM sleep. Heavy smokers often sleep very lightly and have reduced amounts of REM sleep. They also tend to wake up after 3 or 4 hours of sleep due to nicotine withdrawal. Many people who suffer from insomnia try to solve the problem with alcohol – the so-called night cap. While alcohol does help people fall into light sleep, it also robs them of REM and the deeper, more restorative stages of sleep. Instead, it keeps them in the lighter stages of sleep, from which they can be awakened easily.

People lose some of the ability to regulate their body temperature during REM, so abnormally hot or cold temperatures in the environment can disrupt this stage of sleep. If our REM sleep is disrupted one night, our bodies don't follow the normal sleep cycle progression the next time we doze off. Instead, we often slip directly into REM sleep and go through extended periods of REM until we "catch up" on this stage of sleep.

People who are under anesthesia or in a coma are often said to be asleep. However, people in these conditions cannot be awakened and do not produce the complex, active brain wave patterns seen in normal sleep. Instead, their brain waves are very slow and weak, sometimes all but undetectable.

How Much Sleep Do We Need?

The amount of sleep each person needs depends on many factors, including age. Infants generally require about 16 hours a day, while teenagers need about 9 hours on average. For most adults, 7 to 8 hours a night appears to be the best amount of sleep, although some people may need as few as 5 hours or as many as 10 hours of sleep each day. Women in the first 3 months of pregnancy often need several more hours of sleep than usual. The amount of sleep a person needs also increases if he or she has been deprived of sleep in previous days. Getting too little sleep creates a "sleep debt," which is much like being overdrawn at a bank. Eventually, your body will demand that the debt be repaid. We don't seem to adapt to getting less sleep than we need; while we may get used to a sleep-depriving schedule, our judgment, reaction time, and other functions are still impaired.

People tend to sleep more lightly and for shorter time spans as they get older, although they generally need about the same amount of sleep as they needed in early adulthood. About half of all people over 65 have frequent sleeping problems, such as insomnia, and deep sleep stages in many elderly people often become very short or stop completely. This change may be a normal part of aging, or it may result from medical problems that are common in elderly people and from the medications and other treatments for those problems.

Experts say that if you feel drowsy during the day, even during boring activities, you haven't had enough sleep. If you routinely fall asleep within 5 minutes of lying down, you probably have severe sleep deprivation, possibly even a sleep disorder. Microsleeps, or very brief episodes of sleep in an otherwise awake person, are another mark of sleep deprivation. In many cases, people are not aware that they are experiencing microsleeps. The widespread practice of "burning the candle at both ends" in western industrialized societies has created so much sleep deprivation that what is really abnormal sleepiness is now almost the norm.

Many studies make it clear that sleep deprivation is dangerous. Sleep-deprived people who are tested by using a driving simulator or by performing a hand-eye coordination task perform as badly as or worse than those who are intoxicated. Sleep deprivation also magnifies alcohol's effects on the body, so a fatigued person who drinks will become much more impaired than someone who is well-rested. Driver fatigue is responsible for an estimated 100,000 motor vehicle accidents and 1500 deaths each year, according to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. Since drowsiness is the brain's last step before falling asleep, driving while drowsy can – and often does – lead to disaster. Caffeine and other stimulants cannot overcome the effects of severe sleep deprivation. The National Sleep Foundation says that if you have trouble keeping your eyes focused, if you can't stop yawning, or if you can't remember driving the last few miles, you are probably too drowsy to drive safely.

What Does Sleep Do For Us?

Although scientists are still trying to learn exactly why people need sleep, animal studies show that sleep is necessary for survival. For example, while rats normally live for two to three years, those deprived of REM sleep survive only about 5 weeks on average, and rats deprived of all sleep stages live only about 3 weeks. Sleep-deprived rats also develop abnormally low body temperatures and sores on their tail and paws. The sores may develop because the rats' immune systems become impaired. Some studies suggest that sleep deprivation affects the immune system in detrimental ways.

Sleep appears necessary for our nervous systems to work properly. Too little sleep leaves us drowsy and unable to concentrate the next day. It also leads to impaired memory and physical performance and reduced ability to carry out math calculations. If sleep deprivation continues, hallucinations and mood swings may develop. Some experts believe sleep gives neurons used while we are awake a chance to shut down and repair themselves. Without sleep, neurons may become so depleted in energy or so polluted with byproducts of normal cellular activities that they begin to malfunction. Sleep also may give the brain a chance to exercise important neuronal connections that might otherwise deteriorate from lack of activity.

Deep sleep coincides with the release of growth hormone in children and young adults. Many of the body's cells also show increased production and reduced breakdown of proteins during deep sleep. Since proteins are the building blocks needed for cell growth and for repair of damage from factors like stress and ultraviolet rays, deep sleep may truly be "beauty sleep." Activity in parts of the brain that control emotions, decision-making processes, and social interactions is drastically reduced during deep sleep, suggesting that this type of sleep may help people maintain optimal emotional and social functioning while they are awake. A study in rats also showed that certain nerve-signaling patterns which the rats generated during the day were repeated during deep sleep. This pattern repetition may help encode memories and improve learning.

Dreaming and REM Sleep

We typically spend more than 2 hours each night dreaming. Scientists do not know much about how or why we dream. Sigmund Freud, who greatly influenced the field of psychology, believed dreaming was a "safety valve" for unconscious desires. Only after 1953, when researchers first described REM in sleeping infants, did scientists begin to carefully study sleep and dreaming. They soon realized that the strange, illogical experiences we call dreams almost always occur during REM sleep. While most mammals and birds show signs of REM sleep, reptiles and other cold-blooded animals do not.

REM sleep begins with signals from an area at the base of the brain called the pons (see figure 2 ). These signals travel to a brain region called the thalamus, which relays them to the cerebral cortex – the outer layer of the brain that is responsible for learning, thinking, and organizing information. The pons also sends signals that shut off neurons in the spinal cord, causing temporary paralysis of the limb muscles. If something interferes with this paralysis, people will begin to physically "act out" their dreams – a rare, dangerous problem called REM sleep behavior disorder. A person dreaming about a ball game, for example, may run headlong into furniture or blindly strike someone sleeping nearby while trying to catch a ball in the dream.

REM sleep stimulates the brain regions used in learning. This may be important for normal brain development during infancy, which would explain why infants spend much more time in REM sleep than adults (see Sleep: A Dynamic Activity ). Like deep sleep, REM sleep is associated with increased production of proteins. One study found that REM sleep affects learning of certain mental skills. People taught a skill and then deprived of non-REM sleep could recall what they had learned after sleeping, while people deprived of REM sleep could not.

Some scientists believe dreams are the cortex's attempt to find meaning in the random signals that it receives during REM sleep. The cortex is the part of the brain that interprets and organizes information from the environment during consciousness. It may be that, given random signals from the pons during REM sleep, the cortex tries to interpret these signals as well, creating a "story" out of fragmented brain activity.

Sleep and Circadian Rhythms

Circadian rhythms are regular changes in mental and physical characteristics that occur in the course of a day (circadian is Latin for "around a day"). Most circadian rhythms are controlled by the body's biological "clock." This clock, called the suprachiasmatic nucleus or SCN (see figure 2 ), is actually a pair of pinhead-sized brain structures that together contain about 20,000 neurons. The SCN rests in a part of the brain called the hypothalamus, just above the point where the optic nerves cross. Light that reaches photoreceptors in the retina (a tissue at the back of the eye) creates signals that travel along the optic nerve to the SCN.

Signals from the SCN travel to several brain regions, including the pineal gland, which responds to light-induced signals by switching off production of the hormone melatonin. The body's level of melatonin normally increases after darkness falls, making people feel drowsy. The SCN also governs functions that are synchronized with the sleep/wake cycle, including body temperature, hormone secretion, urine production, and changes in blood pressure.

By depriving people of light and other external time cues, scientists have learned that most people's biological clocks work on a 25-hour cycle rather than a 24-hour one. But because sunlight or other bright lights can reset the SCN, our biological cycles normally follow the 24-hour cycle of the sun, rather than our innate cycle. Circadian rhythms can be affected to some degree by almost any kind of external time cue, such as the beeping of your alarm clock, the clatter of a garbage truck, or the timing of your meals. Scientists call external time cues zeitgebers (German for "time givers").

When travelers pass from one time zone to another, they suffer from disrupted circadian rhythms, an uncomfortable feeling known as jet lag. For instance, if you travel from California to New York, you "lose" 3 hours according to your body's clock. You will feel tired when the alarm rings at 8 a.m. the next morning because, according to your body's clock, it is still 5 a.m. It usually takes several days for your body's cycles to adjust to the new time.

To reduce the effects of jet lag, some doctors try to manipulate the biological clock with a technique called light therapy. They expose people to special lights, many times brighter than ordinary household light, for several hours near the time the subjects want to wake up. This helps them reset their biological clocks and adjust to a new time zone.

Symptoms much like jet lag are common in people who work nights or who perform shift work. Because these people's work schedules are at odds with powerful sleep-regulating cues like sunlight, they often become uncontrollably drowsy during work, and they may suffer insomnia or other problems when they try to sleep. Shift workers have an increased risk of heart problems, digestive disturbances, and emotional and mental problems, all of which may be related to their sleeping problems. The number and severity of workplace accidents also tend to increase during the night shift. Major industrial accidents attributed partly to errors made by fatigued night-shift workers include the Exxon Valdez oil spill and the Three Mile Island and Chernobyl nuclear power plant accidents. One study also found that medical interns working on the night shift are twice as likely as others to misinterpret hospital test records, which could endanger their patients. It may be possible to reduce shift-related fatigue by using bright lights in the workplace, minimizing shift changes, and taking scheduled naps.

Many people with total blindness experience life-long sleeping problems because their retinas are unable to detect light. These people have a kind of permanent jet lag and periodic insomnia because their circadian rhythms follow their innate cycle rather than a 24-hour one. Daily supplements of melatonin may improve night-time sleep for such patients. However, since the high doses of melatonin found in most supplements can build up in the body, long-term use of this substance may create new problems. Because the potential side effects of melatonin supplements are still largely unknown, most experts discourage melatonin use by the general public.

Sleep and Disease

Sleep and sleep-related problems play a role in a large number of human disorders and affect almost every field of medicine. For example, problems like stroke and asthma attacks tend to occur more frequently during the night and early morning, perhaps due to changes in hormones, heart rate, and other characteristics associated with sleep. Sleep also affects some kinds of epilepsy in complex ways. REM sleep seems to help prevent seizures that begin in one part of the brain from spreading to other brain regions, while deep sleep may promote the spread of these seizures. Sleep deprivation also triggers seizures in people with some types of epilepsy.

Neurons that control sleep interact closely with the immune system. As anyone who has had the flu knows, infectious diseases tend to make us feel sleepy. This probably happens because cytokines, chemicals our immune systems produce while fighting an infection, are powerful sleep-inducing chemicals. Sleep may help the body conserve energy and other resources that the immune system needs to mount an attack.

Sleeping problems occur in almost all people with mental disorders, including those with depression and schizophrenia. People with depression, for example, often awaken in the early hours of the morning and find themselves unable to get back to sleep. The amount of sleep a person gets also strongly influences the symptoms of mental disorders. Sleep deprivation is an effective therapy for people with certain types of depression, while it can actually cause depression in other people. Extreme sleep deprivation can lead to a seemingly psychotic state of paranoia and hallucinations in otherwise healthy people, and disrupted sleep can trigger episodes of mania (agitation and hyperactivity) in people with manic depression.

Sleeping problems are common in many other disorders as well, including Alzheimer's disease, stroke, cancer, and head injury. These sleeping problems may arise from changes in the brain regions and neurotransmitters that control sleep, or from the drugs used to control symptoms of other disorders. In patients who are hospitalized or who receive round-the-clock care, treatment schedules or hospital routines also may disrupt sleep. The old joke about a patient being awakened by a nurse so he could take a sleeping pill contains a grain of truth. Once sleeping problems develop, they can add to a person's impairment and cause confusion, frustration, or depression. Patients who are unable to sleep also notice pain more and may increase their requests for pain medication. Better management of sleeping problems in people who have other disorders could improve these patients' health and quality of life.

Sleep Disorders

At least 40 million Americans each year suffer from chronic, long-term sleep disorders each year, and an additional 20 million experience occasional sleeping problems. These disorders and the resulting sleep deprivation interfere with work, driving, and social activities. They also account for an estimated $16 billion in medical costs each year, while the indirect costs due to lost productivity and other factors are probably much greater. Doctors have described more than 70 sleep disorders, most of which can be managed effectively once they are correctly diagnosed. The most common sleep disorders include insomnia, sleep apnea, restless legs syndrome, and narcolepsy.

Insomnia

Almost everyone occasionally suffers from short-term insomnia. This problem can result from stress, jet lag, diet, or many other factors. Insomnia almost always affects job performance and well-being the next day. About 60 million Americans a year have insomnia frequently or for extended periods of time, which leads to even more serious sleep deficits. Insomnia tends to increase with age and affects about 40 percent of women and 30 percent of men. It is often the major disabling symptom of an underlying medical disorder.

For short-term insomnia, doctors may prescribe sleeping pills. Most sleeping pills stop working after several weeks of nightly use, however, and long-term use can actually interfere with good sleep. Mild insomnia often can be prevented or cured by practicing good sleep habits (see "Tips for a Good Night's Sleep"). For more serious cases of insomnia, researchers are experimenting with light therapy and other ways to alter circadian cycles.

Sleep Apnea

Sleep apnea is a disorder of interrupted breathing during sleep. It usually occurs in association with fat buildup or loss of muscle tone with aging. These changes allow the windpipe to collapse during breathing when muscles relax during sleep (see figure 3 ). This problem, called obstructive sleep apnea, is usually associated with loud snoring (though not everyone who snores has this disorder). Sleep apnea also can occur if the neurons that control breathing malfunction during sleep.

During an episode of obstructive apnea, the person's effort to inhale air creates suction that collapses the windpipe. This blocks the air flow for 10 seconds to a minute while the sleeping person struggles to breathe. When the person's blood oxygen level falls, the brain responds by awakening the person enough to tighten the upper airway muscles and open the windpipe. The person may snort or gasp, then resume snoring. This cycle may be repeated hundreds of times a night. The frequent awakenings that sleep apnea patients experience leave them continually sleepy and may lead to personality changes such as irritability or depression. Sleep apnea also deprives the person of oxygen, which can lead to morning headaches, a loss of interest in sex, or a decline in mental functioning. It also is linked to high blood pressure, irregular heartbeats, and an increased risk of heart attacks and stroke. Patients with severe, untreated sleep apnea are two to three times more likely to have automobile accidents than the general population. In some high-risk individuals, sleep apnea may even lead to sudden death from respiratory arrest during sleep.

An estimated 18 million Americans have sleep apnea. However, few of them have had the problem diagnosed. Patients with the typical features of sleep apnea, such as loud snoring, obesity, and excessive daytime sleepiness, should be referred to a specialized sleep center that can perform a test called polysomnography. This test records the patient's brain waves, heartbeat, and breathing during an entire night. If sleep apnea is diagnosed, several treatments are available. Mild sleep apnea frequently can be overcome through weight loss or by preventing the person from sleeping on his or her back. Other people may need special devices or surgery to correct the obstruction. People with sleep apnea should never take sedatives or sleeping pills, which can prevent them from awakening enough to breathe.

Restless Legs Syndrome

Restless legs syndrome (RLS), a familial disorder causing unpleasant crawling, prickling, or tingling sensations in the legs and feet and an urge to move them for relief, is emerging as one of the most common sleep disorders, especially among older people. This disorder, which affects as many as 12 million Americans, leads to constant leg movement during the day and insomnia at night. Severe RLS is most common in elderly people, though symptoms may develop at any age. In some cases, it may be linked to other conditions such as anemia, pregnancy, or diabetes.

Many RLS patients also have a disorder known as periodic limb movement disorder or PLMD, which causes repetitive jerking movements of the limbs, especially the legs. These movements occur every 20 to 40 seconds and cause repeated awakening and severely fragmented sleep. In one study, RLS and PLMD accounted for a third of the insomnia seen in patients older than age 60.

RLS and PLMD often can be relieved by drugs that affect the neurotransmitter dopamine, suggesting that dopamine abnormalities underlie these disorders' symptoms. Learning how these disorders occur may lead to better therapies in the future.

Narcolepsy

Narcolepsy affects an estimated 250,000 Americans. People with narcolepsy have frequent "sleep attacks" at various times of the day, even if they have had a normal amount of night-time sleep. These attacks last from several seconds to more than 30 minutes. People with narcolepsy also may experience cataplexy (loss of muscle control during emotional situations), hallucinations, temporary paralysis when they awaken, and disrupted night-time sleep. These symptoms seem to be features of REM sleep that appear during waking, which suggests that narcolepsy is a disorder of sleep regulation. The symptoms of narcolepsy typically appear during adolescence, though it often takes years to obtain a correct diagnosis. The disorder (or at least a predisposition to it) is usually hereditary, but it occasionally is linked to brain damage from a head injury or neurological disease.

Once narcolepsy is diagnosed, stimulants, antidepressants, or other drugs can help control the symptoms and prevent the embarrassing and dangerous effects of falling asleep at improper times. Naps at certain times of the day also may reduce the excessive daytime sleepiness.

In 1999, a research team working with canine models identified a gene that causes narcolepsy–a breakthrough that brings a cure for this disabling condition within reach. The gene, hypocretin receptor 2, codes for a protein that allows brain cells to receive instructions from other cells. The defective versions of the gene encode proteins that cannot recognize these messages, perhaps cutting the cells off from messages that promote wakefulness. The researchers know that the same gene exists in humans, and they are currently searching for defective versions in people with narcolepsy.

The Future

Sleep research is expanding and attracting more and more attention from scientists. Researchers now know that sleep is an active and dynamic state that greatly influences our waking hours, and they realize that we must understand sleep to fully understand the brain. Innovative techniques, such as brain imaging, can now help researchers understand how different brain regions function during sleep and how different activities and disorders affect sleep. Understanding the factors that affect sleep in health and disease also may lead to revolutionary new therapies for sleep disorders and to ways of overcoming jet lag and the problems associated with shift work. We can expect these and many other benefits from research that will allow us to truly understand sleep's impact on our lives.

Choosing the Right Sleep Medicines, or None at All

By Peter Jaret : NY Times Article : August 7, 2008

In Brief:

The safety of insomnia drugs has improved steadily over the past 30 years.

Choosing the right sleep medication is important; some are best at helping people fall asleep, while others help people stay asleep through the night.

Although medications are often recommended for acute insomnia, the first line of treatment for chronic insomnia is behavioral therapy.

Insomniacs know all too well what it’s like to lie awake in a tangle of sheets, the day’s worries parading through the brain as the minutes tick past with agonizing slowness. With studies linking troubled sleep to a variety of health problems including heart attacks and obesity, it’s enough to keep anyone awake at night.

An estimated 30 million Americans wrestle with chronic insomnia. Many suffer in silence. A 2005 National Sleep Foundation survey found that only one-third of patients with insomnia were asked by their primary care physicians about the quality of their sleep. Insomnia sufferers are equally unlikely to raise the issue with their doctors, studies show. And that’s too bad, experts say.

More and safer medications for sleep problems are available. And with a growing list to choose from, doctors can target prescriptions more precisely to specific complaints: trouble falling asleep, for instance, versus trouble staying asleep.

Remedies to help people fall asleep have been around for centuries, from laudanum in the 1800s to barbiturates more recently. “Unfortunately, most of them were addictive and potentially deadly,” said Dr. David Neubauer, associate director of the Sleep Disorders Center at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore. “The history of sleep medications is really a tale of improving safety.”

A big advance came in the 1970s with the introduction of benzodiazepine drugs like Halcion, Xanax and Restoril. Although far safer than barbiturates, these sleep medications can still cause dependence and withdrawal symptoms like rebound insomnia. That prompted the Food and Drug Administration to approve them only for short-term use, usually no more than two weeks.

The same restrictions remained in place when a new generation of hypnotic drugs, known as nonbenzodiazepines or “Z” drugs, hit the market, starting with Ambien in the early 1990s.

“But it soon became evident that Ambien was really quite different, that it didn’t have the same withdrawal effects or dependency,” said Dr. Michael Thorpy, director of the Sleep-Wake Disorders Center at Montefiore Medical Center in the Bronx.

In one recent study, researchers at Duke University Medical Center pitted Ambien-CR, a controlled-release formulation, against a placebo. After taking the drug for six months, volunteers reported no rebound insomnia when they stopped. Almost 90 percent said the drug helped them sleep, compared with just under 60 percent of the placebo group. Those on the active drug also reported less morning sleepiness and greater ability to concentrate during the day.

Newer nonbenzodiazepines like Lunesta and Sonata have no restrictions on how long they can be used. Even so, they remain on the federal list of controlled substances because of their potential for abuse.

The latest sleeping pill to win F.D.A. approval, called Rozerem, is the first sleeping pill not on that list, because there appears to be little chance it will be abused. The drug, which targets receptors in the brain for the sleep hormone melatonin, represents the first new class of sleep medication in several decades.

Safer sleep medicines are particularly welcome for people whose insomnia is caused by chronic pain or other persistent medical conditions, Dr. Thorpy said. “These are people who are never going to get a good night’s sleep without medication, and who may need hypnotics for the rest of their lives,” he said.

But those people are the exceptions — most insomniacs will not require pills indefinitely. Indeed, medications are generally considered the first-line treatment not for chronic sleep problems but for acute, short-term insomnia brought on by, say, unusual stress at work or the aftermath of surgery.

“Medications can help nip insomnia in the bud, and may prevent it from becoming a chronic problem,” said Wilfred Pigeon, assistant professor of psychiatry at the Sleep and Neurophysiology Research Laboratory at the University of Rochester.

Doctors are increasingly exploiting the differences among nonbenzodiazepines to tailor their prescription to particular sleep complaints.

Chief among these differences is a drug’s half-life, a measure of how long the active ingredients remain in the body, which can range from one to seven hours for the top sleep aids. If the problem is falling asleep, a drug with a short half-life, like Sonata or Rozerem, may be the best choice. If a patient complains about waking in the middle of the night, a medicine with a longer half-life, like Ambien-CR or Lunesta, may work best.

Although the F.D.A. has not yet approved sleeping pills specifically to be taken when people find themselves wide awake in the middle of the night, “many people take Sonata that way, because it has a very short half-life,” Dr. Thorpy said.

A 2006 study by researchers at the Clinilabs Sleep Disorders Institute at St. Luke’s-Roosevelt Hospital Center in New York found that Sonata taken in the middle of the night caused less next-day sleepiness than Ambien, a drug with a longer half-life.

But even the newer sleep medicines have side effects, including reports of people having no memory of raiding the refrigerator or getting behind the wheel the night before. And because sleep medications address only the symptoms of insomnia and not the causes, many experts agree that the best approach when sleep problems persist is cognitive-behavioral therapy, which teaches strategies like better sleep habits and restricting the amount of time spent awake in bed.

“Drugs can help relieve people’s acute anxiety about being able to fall asleep or stay asleep,” Dr. Pigeon said. Behavioral approaches, which in practice are often combined with sleep drugs, “help make lasting changes in the quality of people’s sleep,” he said.

But changing sleep habits takes time, and a shortage of therapists trained in behavioral sleep medicine means that option is not available to everyone who might benefit. Harried physicians often find it easier to write out a prescription than to discuss sleep hygiene with patients, who likewise often seek the quick relief offered by pills.

Small wonder that pharmaceutical researchers are continually in search of novel insomnia drugs. One drug under development, for example, works in a new way to enhance slow-wave sleep, the deepest stage of slumber, with a goal of making people feel more refreshed in the morning.

“People come in complaining about their sleep,” Dr. Neubauer said. “But of course what we’re really looking for is better wakefulness.”

Tips for a Good Night's Sleep:

Adapted from "When You Can't Sleep: The ABCs of ZZZs," by the National Sleep Foundation.

Sleep Apnea ........An Overview

Obstructive sleep apnea is a condition in which a person has episodes of stopped breathing during sleep.

See also:

Alternative Names Sleep apnea - obstructive; Apnea - obstructive sleep apnea syndrome

Causes » Normally, the muscles of the upper part of the throat help keep the airway open and allow air to flow into the lungs. Even though these muscles usually relax during sleep, the upper throat remains open enough to let air pass by.

However, some people have a narrower throat area, and, during sleep, relaxation of the muscles causes the passage to completely close. This prevents air from getting into the lungs. Loud snoring and labored breathing occur. During deep sleep, breathing can stop for a short period of time (often more than 10 seconds). This is called apnea.

An apnea episode is followed by a sudden attempt to breathe, and a change to a lighter stage of sleep. The result is fragmented sleep that is not restful, leading to excessive daytime drowsiness.

Older obese men seem to be at higher risk, although as many as 40% of people with obstructive sleep apnea are not obese. The following factors may also increase your risk for obstructive sleep apnea:

In-Depth Causes »

Symptoms » It is important to emphasize that, often, the person who has obstructive sleep apnea does not remember the episodes of apnea during the night. The main symptoms are usually associated with excessive daytime sleepiness due to poor sleep during the night. Often, family members, especially spouses, witness the periods of no breathing.

A person with obstructive sleep apnea usually snores heavily soon after falling asleep. The snoring continues at a regular pace for a period of time, often becoming louder, but is then interrupted by a long silent period during which there is no breathing. This is followed by a loud snort and gasp, and the snoring returns. This pattern repeats frequently throughout the night.

Symptoms that may be observed include:

Exams and Tests » The health care provider will perform a physical exam. This will involve carefully checking your mouth, neck, and throat. You will be asked about your medical history. Often, a survey that asks a series of questions about daytime sleepiness, sleep quality, and bedtime habits is given.

A sleep study (polysomnogram) is used to confirm obstructive sleep apnea.

Other tests that may be performed include:

Treatment » The goal is to keep the airway open so that breathing does not stop during sleep.

The following may relieve symptoms of sleep apnea in some individuals:

Surgery may be an option in some cases. This may involve:

In-Depth Treatment »

Outlook (Prognosis) When treated correctly, obstructive sleep apnea may be controlled. However, many patients are unable or unwilling to tolerate CPAP therapy.

Possible Complications During the nonbreathing episodes, blood oxygen levels falls. Persistent low levels of oxygen (hypoxia) may cause many of the daytime symptoms. If the condition is severe enough, pulmonary hypertension may develop, leading to right-sided heart failure or cor pulmonale.

Other complications include:

Scientists know that many people inadvertently undermine their ability to fall asleep and stay asleep for a full night. Here are some frequent suggestions:

1. Establish a regular sleep schedule and try to stick to it, even on weekends.

2. If you nap during the day, limit it to 20 or 30 minutes, preferably early in the afternoon.

3. Avoid alcohol in the evening, as it can disrupt sleep.

4. Don’t eat a big meal just before bedtime, but don’t go to bed hungry, either. Eat a light snack before bed, if needed, preferably one high in carbohydrates.

5. If you use medications that are stimulants, take them in the morning, or ask your doctor if you can switch to a nonstimulating alternative. If you use drugs that cause drowsiness, take them in the evening.

6. Get regular exercise during the day, but avoid vigorous exercise within three hours of bedtime.

7. If pressing thoughts interfere with falling asleep, write them down (keep a pad and pen next to the bed) and try to forget about them until morning.

8. If you are frequently awakened by a need to use the bathroom, cut down on how much you drink late in the day.

9. If you smoke, quit. Among other hazards, nicotine is a stimulant and can cause nightmares.

10. Avoid beverages and foods containing caffeine after 3 p.m. Even decaf versions have some caffeine, which can bother some people.

Cheating Ourselves of Sleep

By Jane E. Brody : NY Times : June 17, 2013

Think you do just fine on five or six hours of shut-eye? Chances are, you are among the many millions who unwittingly shortchange themselves on sleep.

Research shows that most people require seven or eight hours of sleep to function optimally. Failing to get enough sleep night after night can compromise your health and may even shorten your life. From infancy to old age, the effects of inadequate sleep can profoundly affect memory, learning, creativity, productivity and emotional stability, as well as your physical health.

According to sleep specialists at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine and Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic, among others, a number of bodily systems are negatively affected by inadequate sleep: the heart, lungs and kidneys; appetite, metabolism and weight control; immune function and disease resistance; sensitivity to pain; reaction time; mood; and brain function.

Poor sleep is also a risk factor for depression and substance abuse, especially among people with post-traumatic stress disorder, according to Anne Germain, associate professor of psychiatry at the University of Pittsburgh. People with PTSD tend to relive their trauma when they try to sleep, which keeps their brains in a heightened state of alertness.

Dr. Germain is studying what happens in the brains of sleeping veterans with PTSD in hopes of developing more effective treatments for them and for people with lesser degrees of stress that interfere with a good night’s sleep.

The elderly are especially vulnerable. Timothy H. Monk, who directs the Human Chronobiology Research Program at Western Psychiatric, heads a five-year federally funded study of circadian rhythms, sleep strength, stress reactivity, brain function and genetics among the elderly. “The circadian signal isn’t as strong as people get older,” he said.

He is finding that many are helped by standard behavioral treatments for insomnia, like maintaining a regular sleep schedule, avoiding late-in-day naps and caffeine, and reducing distractions from light, noise and pets.

It should come as no surprise that myriad bodily systems can be harmed by chronically shortened nights. “Sleep affects almost every tissue in our bodies,” said Dr. Michael J. Twery, a sleep specialist at the National Institutes of Health.

Several studies have linked insufficient sleep to weight gain. Not only do night owls with shortchanged sleep have more time to eat, drink and snack, but levels of the hormone leptin, which tells the brain enough food has been consumed, are lower in the sleep-deprived while levels of ghrelin, which stimulates appetite, are higher.

In addition, metabolism slows when one’s circadian rhythm and sleep are disrupted; if not counteracted by increased exercise or reduced caloric intake, this slowdown could add up to 10 extra pounds in a year.

The body’s ability to process glucose is also adversely affected, which may ultimately result in Type 2 diabetes. In one study, healthy young men prevented from sleeping more than four hours a night for six nights in a row ended up with insulin and blood sugar levels like those of people deemed prediabetic. The risks of cardiovascular diseases and stroke are higher in people who sleep less than six hours a night. Even a single night of inadequate sleep can cause daylong elevations in blood pressure in people with hypertension. Inadequate sleep is also associated with calcification of coronary arteries and raised levels of inflammatory factors linked to heart disease. (In terms of cardiovascular disease, sleeping too much may also be risky. Higher rates of heart disease have been found among women who sleep more than nine hours nightly.)

The risk of cancer may also be elevated in people who fail to get enough sleep. A Japanese study of nearly 24,000 women ages 40 to 79 found that those who slept less than six hours a night were more likely to develop breast cancer than women who slept longer. The increased risk may result from diminished secretion of the sleep hormone melatonin. Among participants in the Nurses Health Study, Eva S. Schernhammer of Harvard Medical School found a link between low melatonin levels and an increased risk of breast cancer.

A study of 1,240 people by researchers at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland found an increased risk of potentially cancerous colorectal polyps in those who slept fewer than six hours nightly.

Children can also experience hormonal disruptions from inadequate sleep. Growth hormone is released during deep sleep; it not only stimulates growth in children, but also boosts muscle mass and repairs damaged cells and tissues in both children and adults.

Dr. Vatsal G. Thakkar, a psychiatrist affiliated with New York University, recently described evidence associating inadequate sleep with an erroneous diagnosis of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children. In one study, 28 percent of children with sleep problems had symptoms of the disorder, but not the disorder.

During sleep, the body produces cytokines, cellular hormones that help fight infections. Thus, short sleepers may be more susceptible to everyday infections like colds and flu. In a study of 153 healthy men and women, Sheldon Cohen and colleagues at Carnegie Mellon University found that those who slept less than seven hours a night were three times as likely to develop cold symptoms when exposed to a cold-causing virus than were people who slept eight or more hours.

Some of the most insidious effects of too little sleep involve mental processes like learning, memory, judgment and problem-solving. During sleep, new learning and memory pathways become encoded in the brain, and adequate sleep is necessary for those pathways to work optimally. People who are well rested are better able to learn a task and more likely to remember what they learned. The cognitive decline that so often accompanies aging may in part result from chronically poor sleep.

With insufficient sleep, thinking slows, it is harder to focus and pay attention, and people are more likely to make poor decisions and take undue risks. As you might guess, these effects can be disastrous when operating a motor vehicle or dangerous machine.

In driving tests, sleep-deprived people perform as if drunk, and no amount of caffeine or cold air can negate the ill effects.

At your next health checkup, tell your doctor how long and how well you sleep. Be honest: Sleep duration and quality can be as important to your health as your blood pressure and cholesterol level.

This is the first of two columns on inadequate sleep.

Why We Need Our Sleep

By Robert Lee Hotz : WSJ Article : January 18, 2008

People have been trying to figure out why we sleep for almost as long as we have been conscious of being awake, tossing and turning in the dark.

After a few restless nights, most of us can't even think straight. We are less able to make sense of problems, make competent moral judgments or retain what we learn, even though studies show our brain cells fire more frenetically to overcome the lack of sleep. Lose too much sleep and we become reckless, emotionally fragile and more vulnerable to infections as well as diabetes, heart disease and obesity, recent research suggests.

Yet scientists probing the purpose of sleep are still largely in the dark. "Why we sleep at all is a strange bastion of the unknown," said sleep psychologist Matthew Walker at the University of California in Berkeley.

One vital function of sleep, researchers argue, may be to help our brains sort, store and consolidate new memories, etching experiences more indelibly into the brain's biochemical archives.

.

Even a 90-minute nap can significantly improve our ability to master new motor skills and strengthen our memories of what we learn, researchers at the University of Haifa in Israel reported last month in Nature Neuroscience. "Napping is as effective as a night's sleep," said psychologist Sara Mednick at the University of California in San Diego.

Moreover, slumber seems to boost our ability to make sense of new knowledge by allowing the brain to detect connections between things we learn.

In research published in April in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Dr. Walker and his collaborators at the Harvard Medical School tested 56 college students and found that their ability to discern the big picture in disparate pieces of information improved measurably after the brain could, during a night's sleep, mull things over.

It is these patterns of meaning -- the distilled essence of knowledge -- that we remember so well. "Sleep helps stabilize memory," said neurologist Jeffrey Ellenbogen, director of the sleep-medicine program at Massachusetts General Hospital.

The erratic biorhythms of sleep and behavior are intertwined everywhere in nature. Socially active fruit flies need more sleep than loner flies, and even zebra fish can get insomnia.

Sleep is controlled partly by our genes. The difference between those of us who naturally wake at dawn and night owls who are wide-eyed at midnight may be partly due to variations in a gene, named Period3, that affects our biological clock. Variations in that gene also make some people especially sensitive to sleep deprivation, scientists at the U.K.'s University of Surrey recently reported.

For many of us, though, sleeplessness is a self-inflicted epidemic in which lifestyle overrides basic biology. "In this odd, Western 24-hour-MTV-fast-food generation we have created, we all feel the need to achieve more and more. The one thing that takes a hit is sleep," Dr. Walker said. On average, most people sleep 75 minutes less each night than people did a century ago, sleep surveys record.

Yet, rarely have so many millions of drowsy people been trying so hard to secure some shut-eye, spending billions on sleep aids. By one estimate, in the U.S. alone, pharmacists filled 49 million prescriptions for sleep drugs last year. Even so, we think we sleep more than we actually do, according to Arizona State University scientists. They recorded how long 2,100 volunteers actually slept each night and compared that to how long the people reported they had slept. Most people overestimated their sleep by about 18 minutes, the scientists found.

The consequences of too little sleep can be dire. Almost half of all heavy-truck accidents in the U.S. can be traced to driver fatigue, while decisions leading to the Challenger space-shuttle disaster, the Chernobyl nuclear-reactor meltdown and the Exxon Valdez oil spill can be partly linked to people drained of rest by round-the-clock work schedules. Weary doctors make more serious medical errors, while sleepy airport baggage screeners make more security mistakes, researchers reported at the Associated Professional Sleep Societies.

All told, the frayed tempers, short attention spans and fuzzy thinking caused by sleep deprivation may cost $15 billion a year in reduced productivity, the National Commission on Sleep Disorders Research estimated.

The expectation of a nap, however, is by itself enough to measurably lower our blood pressure, researchers at the Liverpool John Moores University in England reported in October in the Journal of Applied Physiology.

Indeed, regular nappers -- working men who took a siesta for 30 minutes or more at least three times a week -- had a 64% lower risk of heart-related death, researchers at the University of Athens reported last February in the Archives of Internal Medicine.

"All of the things we are proving about sleep and the brain are things that your mother already knew decades ago," Dr. Walker said. "We are putting the science and the hard facts behind it."

A Good Night’s Sleep Isn’t a Luxury; It’s a Necessity

By Jane E. Brody : NY Times : May 30, 2011

In my younger years, I regarded sleep as a necessary evil, nature’s way of thwarting my desire to cram as many activities into a 24-hour day as possible. I frequently flew the red-eye from California, for instance, sailing (or so I thought) through the next day on less than four hours of uncomfortable sleep.

But my neglect was costing me in ways that I did not fully appreciate. My husband called our nights at the ballet and theater “Jane’s most expensive naps.” Eventually we relinquished our subscriptions. Driving, too, was dicey: twice I fell asleep at the wheel, narrowly avoiding disaster. I realize now that I was living in a state of chronic sleep deprivation.

I don’t want to nod off during cultural events, and I no longer have my husband to spell me at the wheel. I also don’t want to compromise my ability to think and react. As research cited recently in this newspaper’s magazine found, “The sleep-deprived among us are lousy judges of our own sleep needs. We are not nearly as sharp as we think we are.”

Studies have shown that people function best after seven to eight hours of sleep, so I now aim for a solid seven hours, the amount associated with the lowest mortality rate. Yet on most nights something seems to interfere, keeping me up later than my intended lights-out at 10 p.m. — an essential household task, an e-mail requiring an urgent and thoughtful response, a condolence letter I never found time to write during the day, a long article that I must read.

It’s always something.

What’s Keeping Us Up?

I know I’m hardly alone. Between 1960 and 2010, the average night’s sleep for adults in the United States dropped to six and a half hours from more than eight. Some experts predict a continuing decline, thanks to distractions like e-mail, instant and text messaging, and online shopping.

Age can have a detrimental effect on sleep. In a 2005 national telephone survey of 1,003 adults ages 50 and older, the Gallup Organization found that a mere third of older adults got a good night’s sleep every day, fewer than half slept more than seven hours, and one-fifth slept less than six hours a night.

With advancing age, natural changes in sleep quality occur. People may take longer to fall asleep, and they tend to get sleepy earlier in the evening and to awaken earlier in the morning. More time is spent in the lighter stages of sleep and less in restorative deep sleep. R.E.M. sleep, during which the mind processes emotions and memories and relieves stress, also declines with age.

Habits that ruin sleep often accompany aging: less physical activity, less time spent outdoors (sunlight is the body’s main regulator of sleepiness and wakefulness), poorer attention to diet, taking medications that can disrupt sleep, caring for a chronically ill spouse, having a partner who snores. Some use alcohol in hopes of inducing sleep; in fact, it disrupts sleep.