- RETIREMENT ANNOUNCEMENT

- HOME PAGE

- "MYCHART" the new patient portal

- BELMONT MEDICAL ASSOCIATES

- MOUNT AUBURN HOSPITAL

- EMERGENCIES

- PRACTICE PHILOSOPHY

- MY RESUME

- TELEMEDICINE CONSULTATION

- CONTACT ME

- LAB RESULTS

- ePRESCRIPTIONS

- eREFERRALS

- RECORD RELEASE

- MEDICAL SCRIBE

- PHYSICIAN ASSISTANT (PA)

- Medicare Annual Wellness Visit

- Case management/Social work

- Quality Care Measures

- Emergency closing notice

- FEEDBACK

- Talking to your doctor

- Choosing..... and losing a doctor

- INDEX A - Z

- ALLERGIC REACTIONS

- Alternative Medicine

- Alzheimer's Disease

- Bladder Problems

- Blood disorders

- Cancer Concerns

- GENETIC TESTING FOR HEREDITARY CANCER

- Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

- Controversial Concerns

- CPR : Learn and save a life

- CRP : Inflammatory marker

- Diabetes Management

- Dizziness, Vertigo,Tinnitus and Hearing Loss

- EXERCISE

- FEMALE HEALTH

-

GASTROINTESTINAL topics

- Appendicitis

- BRAT diet

- Celiac Disease or Sprue

- Crohn's Disease

- Gastroenterologists for Colon Cancer Screening

- Colonoscopy PREP

- Constipation

- Gluten sensitivity, but not celiac disease

- Heartburn and GERD

- Hemorrhoids and Anal fissure

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- NASH : Non Alcoholic Steato Hepatitis

- FEET PROBLEMS

- HEART RELATED topics

-

INFECTIOUS DISEASES

- Antibiotic Resistance

- Cat bites >

- Clostridia difficile infection - the "antibiotic associated germ"

- CORONA VIRUS

- Dengue Fever and Chikungunya Fever

- Food borne illnesses

- Shingles Vaccine

- Hepatitis B

- Hepatitis C

- Herpes

- Influenza

- Helicobacter pylori - the "ulcer germ"

- HIV Screening

- Lyme and other tick borne diseases

- Measles

- Meningitis

- MRSA (Staph infection)

- Norovirus

- Sexually Transmitted Diseases

- Shingles (Herpes Zoster)

- Sinusitis

- West Nile Virus

- Whooping Cough (Pertussis)

- Zika virus and pregnancy

- INSURANCE related topics

- KIDNEY STONES

- LEG CRAMPS

- LIBRARY for patients

- LIFE DECISIONS

- MALE HEALTH

- Medication/Drug side effects

- MEDICAL MARIJUANA

- MENTAL HEALTH

- Miscellaneous Articles

-

NUTRITION - EXERCISE - WEIGHT

- Cholesterol : New guidelines for treatment

- Advice to lower your cholesterol

- Cholesterol : Control

- Cholesterol : Raising your HDL Level

- Exercise

- Food : Making Smart Choices

- Food : Making Poor Choices

- Food : Grape Fruit and Drug Interaction

- Food : Vitamins, Minerals and Supplements

- Omega 3 fatty acids

- Vitamin B12 deficiency

- Vitamin D

- Weight Loss

- ORTHOPEDICS

- PAIN

- PATIENTS' RIGHTS

- SKIN

- SLEEP

- SMOKING

- STROKE

- THYROID

- SUBSTANCE ABUSE

- Travel and Vaccination

- TREMOR

- Warfarin Anticoagulation

- OTHER STUFF FOLLOWS

- Fact or Opinion?

- Hippocratic Oath

- FREE ADVICE.......for what its worth!

- LAUGHTER.....is the best medicine

- Physicians Pet Peeves

- PHOTO ALBUM - its not all work!

- Cape Town, South Africa

- Tribute page

- The 100 Club

- Free Wi-Fi

Atrial fibrillation

With A-Fib Rhythms, Higher Odds of Stroke

By Jane E. Brody : NY Times : December 30, 2013

When a lean, healthy, physically active person has a stroke, seemingly out of the blue, the cause may well be a heart rhythm abnormality called atrial fibrillation.

Such was the fate of Pamela Bolen of Brooklyn, then 67, who said she collapsed last year at home. Luckily, her husband, Jack, heard her fall, called an ambulance, and within minutes she was at New York Methodist Hospital. There she was given the drug tissue plasminogen activator, or tPA, to dissolve the clot that was blocking circulation in her brain. The treatment spared her lasting disability.

“I had high blood pressure which was completely controlled with medication, but I didn’t know I had atrial fibrillation until I had a stroke,” Ms. Bolen said in an interview. The condition slows blood flow from the heart and was the likely cause of the clot that resulted in her stroke.

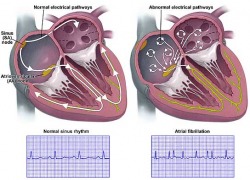

About three million Americans have atrial fibrillation, characterized by multiple irregular electrical signals that cause the heart’s upper chambers, the atria, to contract rapidly, without their usual coordination. This sends an erratic signal to the ventricles, the lower chambers that supply blood to the lungs and rest of the body. People with the disorder face a much higher risk of stroke, and most require treatment to prevent this potentially crippling and sometimes fatal consequence.

“As many as one in five or six strokes is due to atrial fibrillation, and in a lot of these people the rhythm disorder was undetected before the stroke,” said Dr. Christian T. Ruff, cardiologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, who studies new treatments for the disorder.

People with symptomatic A-fib, as it is commonly called, may experience periodic palpitations (a sense that the heart is pounding or fluttering), chest discomfort, shortness of breath, unusual fatigue or dizziness.

A-fib can show up during an electrocardiogram, or EKG, but because the abnormal rhythm may not occur all the time, people suspected of having the condition usually must wear a Holter monitor for days or weeks to obtain a certain diagnosis. This small portable device, connected to electrodes on the chest, continuously records the heart’s rhythm and sends the data to a doctor or company for evaluation.

A-fib is more common in men, tall people and the elderly. As the population ages, the incidence is rising; more than 460,000 new cases are diagnosed annually, a number expected to double in the next 25 years. The condition is also becoming more prevalent at any age, experts say, because of a rise in three leading risk factors — high blood pressure, diabetes and obesity.

These conditions can damage the heart’s electrical system, Dr. Ruff wrote last year in the journal Circulation. Other risk factors include a prior heart attack, overactive thyroid, sleep apnea, excessive alcohol consumption, abnormal heart valves, lung disease and congenital heart defects.

Researchers at the University of California, San Francisco, reported this month in Annals of Internal Medicine that people with a high rate of premature atrial contractions, which can be detected by a Holter monitor worn for 24 hours, face a significantly increased risk of developing A-fib. Dr. Gregory M. Marcus, the senior author and director of clinical research at U.C.S.F.’s cardiology division, theorized that eradicating these premature contractions with drugs or a procedure that destroys the malfunctioning area of the heart may reduce the risk of the rhythm disorder.

Step 1 in treating A-fib is to identify and correct reversible risk factors. Step 2 — and most important, according to Dr. Ruff — is to prevent blood clots from forming by treating patients with anticoagulants.

The most commonly prescribed and least costly treatment is warfarin, also known by the brand name Coumadin, in use for more than half a century. But while highly effective at reducing the risk of stroke, warfarin is a very tricky drug. It interacts with a number of foods, especially those like spinach and kale that are rich in vitamin K, and other drugs that a patient may have to take.

People metabolize warfarin at different rates, making it necessary to repeatedly check a patient’s clotting ability to reduce the risk of excessive bleeding while maintaining an effective anticoagulant level.

Dr. Ruff said that more than half of A-fib patients were either not on an anticoagulant or on an ineffective dose. Fearful of a hemorrhage in the brain, or uncontrolled bleeding in an accident or emergency surgery, doctors may prescribe an amount of warfarin insufficient to prevent a stroke, he said.

This concern has spurred the development of several other anticoagulants that are considerably safer and easier to take, but also far more expensive than the generic warfarin. The Food and Drug Administration has already approved three such medications --apixaban (Eliquis), dabigatran etexilate mesylate (Pradaxa) and rivaroxaban (Xarelto) — and others are being studied.

Patients with A-fib are also often prescribed drugs to normalize the rate and rhythm of the heart’s contractions. Ed Goldman, 73, of Manhattan, who was found to have A-fib 17 years ago, takes amiodarone hydrochloride (Cordarone) and verapamil (Calan and other brand names), and said in an interview that he rarely experienced a slight increase in his heart rate.

Sometimes an electrical shock to the heart, called cardioversion, is used to restore a normal rhythm.

For some patients, however, neither medication nor cardioversion is able to maintain normal heart rhythm. An invasive procedure called ablation is needed to knock out the area or areas of the heart sending out errant signals. A catheter is inserted into a vein, usually through a small cut in the groin, and snaked up to the heart. Small electrodes placed in the heart identify malfunctioning areas, which are then destroyed.

Last year, Dr. Sanjiv Narayan, an electrophysiologist at the University of California, San Diego, and co-authors described a way to more accurately identify the electrical “hot spots” in the heart responsible for an abnormal rhythm. Ablating those regions was nearly twice as effective as the standard approach to eliminating atrial fibrillation with ablation, the team reported in The Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

But even when all traces of A-fib are eliminated, Dr. Ruff said, continued treatment with an anticoagulant is needed to guard against stroke. “Once a person has had A-fib, there is an increased risk of stroke even if their heart is in normal rhythm,” he said.

Calculate Your Risk of Stroke

What is your CHADS VASC score?

If your score is 2 or greater, you are at increased risk of a stroke and should be on some form of anti-coagulation therapy.

C: Do you have congestive heart failure? 0 or 1

H: Do you have high blood pressure? 0 or 1

A2: Are you 75 years or older? 0 or 2

D: Do you have diabetes? 0 or 1

S2: Have you ever had a stroke or TIA? 0 or 2

V: Do you have a history of a previous heart attack or peripheral artery disease 0 or 1

A: Are you between the age of 65 and 74 years? 0 or 1

Sc: Are you female? 0 or 1

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation is increasingly common with advancing age. During atrial fibrillation, the heart's two upper chambers (the atria) beat chaotically and irregularly — out of coordination with the two lower chambers (the ventricles) of the heart. The result is an irregular and often rapid heart rate that causes poor blood flow to the body and symptoms of heart palpitations, shortness of breath and weakness. Most people with atrial fibrillation have an increased risk of developing blood clots that may lead to stroke.

Atrial fibrillation is a common heart rhythm problem.

More than 2 million Americans have atrial fibrillation, which can cause palpitations, shortness of breath, fatigue and stroke.Atrial fibrillation is often caused by changes in your heart that occur as a result of heart disease or high blood pressure. Episodes of atrial fibrillation can come and go, or you may have chronic atrial fibrillation.Although atrial fibrillation usually isn't life-threatening, it can lead to complications. Treatments for atrial fibrillation may include medications and other interventions to try to alter the heart's electrical system.

Signs and symptoms

A heart in atrial fibrillation doesn't beat efficiently. It may not be able to pump an adequate amount of blood out to your body with each heartbeat, causing a drop in your blood pressure.Some people with atrial fibrillation have no symptoms and are unaware of their condition until their doctor discovers it during a physical examination.

Those who do have symptoms may experience:·

Causes

To pump blood, your heart muscles must contract and relax in a coordinated rhythm. Contraction and relaxation are controlled by electrical signals that travel through your heart muscles.

Your heart consists of four chambers — two upper chambers (atria) and two lower chambers (ventricles). Within the upper right chamber of your heart (right atrium) is a group of cells called the sinus node. This is your heart's natural pacemaker. The sinus node produces the impulse that starts each heartbeat.Normally, the impulse travels first through the atria, then through a connecting pathway between the upper and lower chambers of your heart called the atrioventricular (AV) node. As the signal passes through the atria, they contract, pumping blood from your atria into the ventricles below. A split second later, as the signal passes through the AV node through the right and left bundle branches to the ventricles, the ventricles contract, pumping blood out to your body.In atrial fibrillation, the upper chambers of your heart (atria) experience chaotic electrical signals. As a result, they quiver. The AV node — the electrical connection between the atria and the ventricles — is overloaded with impulses trying to get through to the ventricles. The ventricles also beat rapidly, but not as rapidly as the atria. The reason is because the AV node is like a highway on-ramp — only so many cars can get on at one time. The result is an irregular and fast heart rhythm. The heart rate in atrial fibrillation may range from 100 to 175 beats a minute. The normal range for a heart rate is 60 to 100 beats a minute.

Possible causes

Abnormalities or damage to the heart's structure is the most common cause of atrial fibrillation. Diseases affecting the heart's valves or pumping system are common causes, as is long-term high blood pressure. However, some people who have atrial fibrillation don't have underlying structural heart disease, a condition called lone atrial fibrillation. In lone atrial fibrillation, the cause is often unclear. Serious complications are usually rare in lone atrial fibrillation.

Possible causes of atrial fibrillation include: ·

Risk factors:

Screening and diagnosis

To make a diagnosis of atrial fibrillation, your doctor may do tests that involve the following:

Complications

Sometimes, atrial fibrillation can lead to the following complications:

Treatment

Treatments for atrial fibrillation include medications and procedures that attempt to either reset the heart rhythm back to normal or control the heart rate so that the heart doesn't beat dangerously fast, though it may still beat irregularly. Treatments also include blood thinners to prevent blood clots.

The treatment option best for you will depend on how long you've had atrial fibrillation, how bothersome your symptoms are and the underlying cause of your atrial fibrillation. Generally, the goals of treating atrial fibrillation are to:

The best strategy for you depends on many factors, including whether you have other problems with your heart and how well you tolerate the medications available to treat atrial fibrillation or control the rate. In some cases, you may need a more invasive treatment, such as catheter or surgical techniques.

Resetting the rhythm

Ideally, to treat atrial fibrillation, the heart rate and rhythm are reset to normal. This can be accomplished in some cases, depending on the underlying cause of atrial fibrillation and how long you've had it. To correct atrial fibrillation, doctors may be able to reset your heart to its regular rhythm (sinus rhythm) using a procedure called cardioversion. Cardioversion can be done in two ways:

Maintaining normal rhythm

After electrical cardioversion, anti-arrhythmics often are prescribed to help prevent future episodes of atrial fibrillation. Commonly used medications include amiodarone (Cordarone, Pacerone), propafenone (Rythmol), procainamide (Procanbid) and dofetilide (Tikosyn). Although these drugs can help maintain sinus rhythm in many people, they can cause side effects, such as nausea, dizziness and fatigue. In rare instances, they may cause ventricular arrhythmias — life-threatening rhythm disturbances originating in the heart's lower chambers. These medications may be needed indefinitely. Unfortunately, even with medications, the chance of another episode of atrial fibrillation is high.

Rate control

Sometimes atrial fibrillation can't be converted back to a normal heart rhythm. Then the goal is to slow the heart rate (rate control). Traditionally, doctors have prescribed the medication digoxin (Lanoxin). It can control heart rate at rest but not as well during activity. Most people require additional or alternative medications, such as calcium channel blockers or beta blockers. In general, your heart rate should be between 60 and 100 beats a minute when you're at rest. Your doctor can give you guidelines for your maximal heart rate.

Some people may not be able to tolerate medications, or medications don't work to control the heart rate. In these cases, AV node ablation may be an option.

AV node ablation involves applying radio frequency energy to your atrioventricular (AV) node through a long, thin tube (catheter) to destroy this small area of tissue. The procedure prevents the atria from sending electrical impulses to the ventricles. The atria continue to fibrillate, though, and anticoagulant medication is still required. A pacemaker is then implanted to establish a normal rhythm.After AV node ablation, you'll need to continue to take anticoagulant medications to reduce the risk of stroke because your heart is still in atrial fibrillation.

Surgical and catheter interventions

Sometimes medications or cardioversion to control atrial fibrillation doesn't work. In those cases, your doctor may recommend a procedure to destroy the area of heart tissue responsible for the erratic electrical signals and restore your heart to a normal rhythm. These options can include:

Newer and less invasive techniques are being developed to create the atrial scar tissue. Doctors at some centers use radio frequency or cryotherapy applied to the outside surface of the heart through a small chest incision or through a scope placed into the chest cavity (thorascopic approach). Microwave, laser and ultrasound energy are also being studied as options to perform the maze procedure.

Preventing blood clots

Most people who have atrial fibrillation or who are undergoing certain treatment for atrial fibrillation are at especially high risk of blood clots that can lead to stroke. The risk is even higher if other heart disease is present along with atrial fibrillation. Your doctor may prescribe blood-thinning medications (anticoagulants), such as warfarin (Coumadin), dabigatran (Pradaxa) or aspirin, in addition to medications designed to treat your irregular heartbeat. Many people have spells of atrial fibrillation and don't even know it — so you may need lifelong anticoagulants even after your rhythm has been restored to normal.

Atrial flutter

Atrial flutter is similar to atrial fibrillation, but slower. If you have atrial flutter, the abnormal heart rhythm in your atria is more organized and less chaotic than in the abnormal patterns common with atrial fibrillation. Sometimes you may have atrial flutter that develops into atrial fibrillation and vice versa. The symptoms, causes and risk factors of atrial flutter are similar to atrial fibrillation. For example, strokes are a common concern in someone with atrial flutter.

One difference between atrial flutter and atrial fibrillation is that many people with atrial flutter respond better to treatment such as catheter ablation. As with atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter is usually not life-threatening when it's properly treated.

Self-care

There are some things you can do to try and prevent recurrent spells of atrial fibrillation. You may need to reduce or eliminate your intake of caffeine and alcohol, which can overstimulate the heart and trigger an episode of atrial fibrillation. It's also important to be careful when taking over-the-counter (OTC) medications. Some, such as cold medicines containing pseudoephedrine, contain stimulants that can trigger atrial fibrillation. Also, some OTC medications adversely interact with anti-arrhythmic medications.

You may need to make lifestyle changes that improve the overall health of your heart, especially to prevent or treat conditions such as high blood pressure. Your doctor may advise that you:

Evolving View of Dangers of Atrial Fibrillation

By Barnaby J. Feder : NY Times Article : July 7, 2007

Atrial fibrillation occurs when stray electrical pulses set off muscle contractions that disrupt the coordinated top-to-bottom pumping action of the atria: two small blood-receiving chambers atop the heart.

That disruption can cause the atria to beat more than 300 times a minute and hamper the ability of the atria to carry out their function of filling the heart’s main pumps, the ventricles, with blood at the start of every heartbeat.

Fibrillation is more chaotic than another common rhythm irregularity known as atrial flutter. And it is harder to treat because it is far less likely than the flutter condition to be confined to the right atrium. The fibrillation can transform the normally coordinated pumping into a disorganized clash of localized mini-contractions that doctors say makes the muscle fibers of the atria look like a bucket of writhing worms.

Until the 1990s, atrial fibrillation was noted mostly for the number of false alarms it generated among patients who showed up at emergency rooms fearing they were having heart attacks.

Doctors viewed it as relatively benign because the most common symptoms — palpitations, dizziness and shortness of breath — were tolerable and often short-lived. No matter how bad patients may have felt, enough blood still flowed into the ventricles to sustain adequate circulation, as long as the ventricles remained healthy.

But doctors now recognize that atrial fibrillation allows blood to pool in the atria and form clots, which in turn may explain why such patients are prone to strokes and heart attacks.

About a third of strokes in patients 80 years or older are attributable to atrial fibrillation, and such strokes are more likely to be deadly than other types, according to studies summarized by Dr. Andrew E. Epstein, a researcher at the University of Alabama in Birmingham, at a meeting of heart rhythm specialists last month in Denver.

And research suggests the added burden that inefficient atrial pumping puts on the ventricles may contribute over time to heart failure.

Atrial Fibrillation FAQ

Some common questions asked by patients:

¶How will I know if I have atrial fibrillation?

You may not. Some patients feel no symptoms and the rapid contractions of the atria may end without any medical intervention. The diagnosis is normally made on the basis of an electrocardiogram.

¶What causes atrial fibrillation?

That is not yet clear and there may well be multiple possible contributors to various forms of the condition. Recent research suggests susceptibility may be inherited in some cases. Stress, smoking and heavy drinking, obesity and a range of illnesses also raise the risks of developing the condition and the likelihood that it will be more difficult to treat. The risk rises with aging and researchers estimate that 9 percent of people over 80 have the condition.

¶What are the most common problems with ablation?

In addition to the high rate of repeat procedures required because doctors have not successfully ablated all of the abnormal electrical activity, many patients report residual pain where diagnostic devices have been placed in their throat and leg pain or infections where the catheters were inserted into their veins. Because fibrillation often continues for many weeks after the procedure, doctors typically say it is impossible to know how successful an ablation has been until three months have passed.

¶Where are the best hospitals to get ablations?

Because the procedure is a difficult one, success rates often track the experience of the doctors doing it. But with new technology and techniques constantly being introduced and doctors occasionally moving, patients should look further than the hospital’s track record in deciding where to turn. In addition, there are cardiac centers in France, Italy and India that have performed the procedure more often and charge significantly less.

Heart Therapy Strains Efforts to Limit Costs

By Barnaby J. Feder : NY Time Article : July 7, 2007

The nation’s most common cardiac malfunction, once thought harmless but now seen as a potential killer, is testing the ability of regulators to keep up with medical treatments being carried out with scant evidence of long-term effectiveness.

With its episodes of rapid and irregular heartbeats, the condition — atrial fibrillation — afflicts at least 2.2 million people in the United States, according to government estimates. While some experience no symptoms and most others seem to suffer little more than weakness or shortness of breath, the condition is now recognized as a major source of strokes and a precursor to potentially fatal deterioration of the heart.

Already, Medicare and private insurers are spending billions of dollars annually to cope with atrial fibrillation, mostly on hospitalizations, tests and drugs unapproved for such patients. The number of patients is forecast to soar, and spending could climb even more rapidly if many of them receive what many doctors say is now their best hope for a cure — an expensive procedure known as catheter-based ablation.

Advocates of the procedure say it is less invasive than open-heart surgery — the only proven method for curing many patients — and in the long run more cost-effective than drugs, which generally offer temporary relief. Thousands of patients worldwide are estimated to have had the procedure done since 2000.

Federal regulators, however, have not approved as safe and effective any of the devices used. So hospitals and doctors are finding it difficult to be fully reimbursed for the procedure’s cost, which is generally calculated at $25,000 to $50,000.

With politicians and employers debating ways to tame the explosive growth in health care costs, such treatment stands out as another potentially budget-straining medical commitment.

“This is one of those areas where the practice of medicine has moved faster than the approval process,” said Daniel G. Schultz, head of the Center for Devices and Radiological Health at the Food and Drug Administration. “This is very high on our list of areas that need concerted attention.”

Dr. Schultz said the F.D.A. would soon schedule a public meeting with medical and industry experts to discuss what is known — and still needs to be known — about the welter of drugs and devices now being used without approval to treat atrial fibrillation.

Some of the biggest questions focus on ablation, which involves burning, freezing, or otherwise neutralizing the portions of the heart muscle where abnormal electrical pulses set off the irregular heartbeats. The technique aims to restore the ability of the two atria, situated at the top of the heart, to effectively gather blood and prime the ventricles, the heart’s main pumps.

The original form of atrial ablation, using surgical tools, is still employed, but almost always restricted to cases where the chest is already being cut open for heart valve replacement or other surgery. But most atrial ablations are now minimally invasive procedures using tiny devices mounted at the end of long, flexible plastic catheters that are threaded into the heart through veins.

Full-scale clinical trials have not yet demonstrated the long-term benefits from the catheter-based treatment. But, based on promising results from less rigorous studies, major medical societies have endorsed it. It is not uncommon for off-label drugs and devices to be used where doctors believe they can be more successful than any approved therapies.

Still, any situation where off-label therapies have become as widespread as they are in atrial fibrillation “spotlights where we lack good evidence of which patients can benefit from which therapies,” said Dr. Carolyn M. Clancy, director of the federal Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Gathering such data for atrial fibrillation could be especially challenging, she said, because the severity of the condition varies so much among patients and most have other health problems as well that can affect the risks and benefits of competing therapies.

Lacking regulatory guidelines, doctors currently use either experimental equipment or equipment that the F.D.A. has approved for other purposes, like destroying tumors or fixing other heart arrhythmias. While such off-label use of devices is legal for doctors, insurers are sometimes reluctant to cover it, and health care providers may have less legal protection from lawsuits if something goes wrong.

Typically, doctors and hospitals can bill Medicare or private insurers under codes used for somewhat similar cardiac procedures. But the physicians and hospitals say the reimbursements usually fall far short of full compensation for atrial ablation, which can take four hours or more to perform and requires an overnight stay at the hospital.

As a result, most of the procedures are being performed in teaching hospitals or other centers where doctors are on salary, or by practices that see it as a way to distinguish themselves in the broad market for heart patients. Atrial ablation already makes up 30 percent or more of the business of some specialist groups in competitive cardiac care markets like Florida, according to John O. Goodman, a consultant to cardiovascular medical groups.

Last month at a medical meeting in Denver, heart rhythm specialists distributed a statement endorsed by the American Heart Association, the American College of Cardiology and four other big American and European doctors’ groups that recommended atrial ablation as standard care for patients who do not respond to drug therapy.

Doctors say that the number of procedures would surge if the time involved could be cut to less than two hours — which would make current reimbursements less punishing — and if insurance coverage was enhanced.

“It’s a simple fact that if we don’t get paid for something, our desire to do it is going to be much, much less,” Dr. Richard I. Fogel, a cardiologist at the Care Group in Indianapolis, said at the Denver meeting.

Each catheter-based procedure requires disposable equipment that can cost $4,000 to $5,000 a patient.

According to Alexander K. Arrow, an analyst at Lazard Capital Markets, atrial fibrillation ablation procedures already account for more than $200 million of the $1 billion annual market for cardiac ablation equipment, which is also used for other kinds of arrhythmia.

Companies in the field range from small start-ups to industry giants like St. Jude Medical and Johnson & Johnson. Estimates of the potential market for atrial ablation devices in the next decade range from $1.5 billion to nearly $5 billion, according to Medtech Insight, a market research company in Newport Beach, Calif.

Those projections include sophisticated diagnostic and computerized-mapping equipment, which is often sold by the same companies. Some leading medical centers also use expensive robotic guidance systems from companies like Hansen Medical and Stereotaxis.

The technology’s advocates say that unlike drugs, which at best help patients manage the symptoms of atrial fibrillation and reduce the risks, ablation saves money in the long run by curing the condition. Drug regimes, which vary widely, can be kept to under $1,000 annually for many patients by prescribing generic drugs, but ablation advocates say the true cost of relying on drugs includes more frequent hospitalizations, lifestyle restrictions for patients on blood thinners and poorer outcomes.

On the other hand, some regulators and many doctors contend that ablation “cure” rates, while promising, may have been exaggerated by shortcomings in the designs of the clinical trials that supplied the data.

And they say many patients do not fully understand the likelihood — at least 30 percent according to many studies — that they will need subsequent ablations. Patients may also have to continue taking some or all of their drugs or, in some cases, need to have a pacemaker implanted. Moreover, about 2 percent of patients suffer strokes or other serious complications during procedures.

Still, every major ablation center can cite remarkable success stories. Take L. Jay Schweitzer, 57, a former art teacher from Pine Island, N.Y., who for two decades had increasingly frequent and severe episodes of fibrillation, treated with drugs, before having an ablation two years ago.

“I’ve never had anything more than a brief flutter since then,” Mr. Schweitzer said in a recent phone call from Cape May, N.J., where he was on a surfing vacation.

Mr. Schweitzer’s generally good health and relative youth made him an ideal candidate for the procedure, according to Dr. Larry A. Chinitz, a specialist at the New York University Medical Center, who performed it. Success rates appear to be higher for patients with less frequent and shorter episodes of fibrillation.

The drugs that are used as the first type of treatment for patients like Mr. Schweitzer are prescribed “off label” because, in the absence of adequate clinical tests, they have not gained approval for atrial fibrillation. Developed for other heart problems, they include anti-arrythmia agents like amiodarone and generic sotalol, along with anti-clotting drugs, like warfarin. But doctors and patients alike have been dismayed by the side effects of the drugs and their limited long-term effectiveness in controlling atrial fibrillation.

Amiodarone can damage lungs and the liver, cause Parkinson’s-like muscle tremors, and contribute to heart failure.

Warfarin, often prescribed as Coumadin, a Bristol-Myers Squibb brand, raises the risk of excessive bleeding in any case of injury.

“The medications to control it are nasty drugs,” said Dr. Mark W. Connolly, head of the heart surgery group at St. Michael’s Medical Center in Newark. “Many patients don’t tolerate them well, especially if they are active.”

No wonder doctors expect demand for atrial ablation to grow despite the uncertainties and costs. Dr. Andrea Natale, head of the Cleveland Clinic program, said that he was booked into 2008 and that the waiting list for doctors working under him runs four to six months.

And Dr. Chinitz, the New York University specialist who performed Mr. Schweitzer’s procedure, said his backlog was several months and growing.

“Patients really want this,” he said.

By Jane E. Brody : NY Times : December 30, 2013

When a lean, healthy, physically active person has a stroke, seemingly out of the blue, the cause may well be a heart rhythm abnormality called atrial fibrillation.

Such was the fate of Pamela Bolen of Brooklyn, then 67, who said she collapsed last year at home. Luckily, her husband, Jack, heard her fall, called an ambulance, and within minutes she was at New York Methodist Hospital. There she was given the drug tissue plasminogen activator, or tPA, to dissolve the clot that was blocking circulation in her brain. The treatment spared her lasting disability.

“I had high blood pressure which was completely controlled with medication, but I didn’t know I had atrial fibrillation until I had a stroke,” Ms. Bolen said in an interview. The condition slows blood flow from the heart and was the likely cause of the clot that resulted in her stroke.

About three million Americans have atrial fibrillation, characterized by multiple irregular electrical signals that cause the heart’s upper chambers, the atria, to contract rapidly, without their usual coordination. This sends an erratic signal to the ventricles, the lower chambers that supply blood to the lungs and rest of the body. People with the disorder face a much higher risk of stroke, and most require treatment to prevent this potentially crippling and sometimes fatal consequence.

“As many as one in five or six strokes is due to atrial fibrillation, and in a lot of these people the rhythm disorder was undetected before the stroke,” said Dr. Christian T. Ruff, cardiologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, who studies new treatments for the disorder.

People with symptomatic A-fib, as it is commonly called, may experience periodic palpitations (a sense that the heart is pounding or fluttering), chest discomfort, shortness of breath, unusual fatigue or dizziness.

A-fib can show up during an electrocardiogram, or EKG, but because the abnormal rhythm may not occur all the time, people suspected of having the condition usually must wear a Holter monitor for days or weeks to obtain a certain diagnosis. This small portable device, connected to electrodes on the chest, continuously records the heart’s rhythm and sends the data to a doctor or company for evaluation.

A-fib is more common in men, tall people and the elderly. As the population ages, the incidence is rising; more than 460,000 new cases are diagnosed annually, a number expected to double in the next 25 years. The condition is also becoming more prevalent at any age, experts say, because of a rise in three leading risk factors — high blood pressure, diabetes and obesity.

These conditions can damage the heart’s electrical system, Dr. Ruff wrote last year in the journal Circulation. Other risk factors include a prior heart attack, overactive thyroid, sleep apnea, excessive alcohol consumption, abnormal heart valves, lung disease and congenital heart defects.

Researchers at the University of California, San Francisco, reported this month in Annals of Internal Medicine that people with a high rate of premature atrial contractions, which can be detected by a Holter monitor worn for 24 hours, face a significantly increased risk of developing A-fib. Dr. Gregory M. Marcus, the senior author and director of clinical research at U.C.S.F.’s cardiology division, theorized that eradicating these premature contractions with drugs or a procedure that destroys the malfunctioning area of the heart may reduce the risk of the rhythm disorder.

Step 1 in treating A-fib is to identify and correct reversible risk factors. Step 2 — and most important, according to Dr. Ruff — is to prevent blood clots from forming by treating patients with anticoagulants.

The most commonly prescribed and least costly treatment is warfarin, also known by the brand name Coumadin, in use for more than half a century. But while highly effective at reducing the risk of stroke, warfarin is a very tricky drug. It interacts with a number of foods, especially those like spinach and kale that are rich in vitamin K, and other drugs that a patient may have to take.

People metabolize warfarin at different rates, making it necessary to repeatedly check a patient’s clotting ability to reduce the risk of excessive bleeding while maintaining an effective anticoagulant level.

Dr. Ruff said that more than half of A-fib patients were either not on an anticoagulant or on an ineffective dose. Fearful of a hemorrhage in the brain, or uncontrolled bleeding in an accident or emergency surgery, doctors may prescribe an amount of warfarin insufficient to prevent a stroke, he said.

This concern has spurred the development of several other anticoagulants that are considerably safer and easier to take, but also far more expensive than the generic warfarin. The Food and Drug Administration has already approved three such medications --apixaban (Eliquis), dabigatran etexilate mesylate (Pradaxa) and rivaroxaban (Xarelto) — and others are being studied.

Patients with A-fib are also often prescribed drugs to normalize the rate and rhythm of the heart’s contractions. Ed Goldman, 73, of Manhattan, who was found to have A-fib 17 years ago, takes amiodarone hydrochloride (Cordarone) and verapamil (Calan and other brand names), and said in an interview that he rarely experienced a slight increase in his heart rate.

Sometimes an electrical shock to the heart, called cardioversion, is used to restore a normal rhythm.

For some patients, however, neither medication nor cardioversion is able to maintain normal heart rhythm. An invasive procedure called ablation is needed to knock out the area or areas of the heart sending out errant signals. A catheter is inserted into a vein, usually through a small cut in the groin, and snaked up to the heart. Small electrodes placed in the heart identify malfunctioning areas, which are then destroyed.

Last year, Dr. Sanjiv Narayan, an electrophysiologist at the University of California, San Diego, and co-authors described a way to more accurately identify the electrical “hot spots” in the heart responsible for an abnormal rhythm. Ablating those regions was nearly twice as effective as the standard approach to eliminating atrial fibrillation with ablation, the team reported in The Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

But even when all traces of A-fib are eliminated, Dr. Ruff said, continued treatment with an anticoagulant is needed to guard against stroke. “Once a person has had A-fib, there is an increased risk of stroke even if their heart is in normal rhythm,” he said.

Calculate Your Risk of Stroke

What is your CHADS VASC score?

If your score is 2 or greater, you are at increased risk of a stroke and should be on some form of anti-coagulation therapy.

C: Do you have congestive heart failure? 0 or 1

H: Do you have high blood pressure? 0 or 1

A2: Are you 75 years or older? 0 or 2

D: Do you have diabetes? 0 or 1

S2: Have you ever had a stroke or TIA? 0 or 2

V: Do you have a history of a previous heart attack or peripheral artery disease 0 or 1

A: Are you between the age of 65 and 74 years? 0 or 1

Sc: Are you female? 0 or 1

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation is increasingly common with advancing age. During atrial fibrillation, the heart's two upper chambers (the atria) beat chaotically and irregularly — out of coordination with the two lower chambers (the ventricles) of the heart. The result is an irregular and often rapid heart rate that causes poor blood flow to the body and symptoms of heart palpitations, shortness of breath and weakness. Most people with atrial fibrillation have an increased risk of developing blood clots that may lead to stroke.

Atrial fibrillation is a common heart rhythm problem.

More than 2 million Americans have atrial fibrillation, which can cause palpitations, shortness of breath, fatigue and stroke.Atrial fibrillation is often caused by changes in your heart that occur as a result of heart disease or high blood pressure. Episodes of atrial fibrillation can come and go, or you may have chronic atrial fibrillation.Although atrial fibrillation usually isn't life-threatening, it can lead to complications. Treatments for atrial fibrillation may include medications and other interventions to try to alter the heart's electrical system.

Signs and symptoms

A heart in atrial fibrillation doesn't beat efficiently. It may not be able to pump an adequate amount of blood out to your body with each heartbeat, causing a drop in your blood pressure.Some people with atrial fibrillation have no symptoms and are unaware of their condition until their doctor discovers it during a physical examination.

Those who do have symptoms may experience:·

- Palpitations, which are sensations of a racing, uncomfortable, irregular heartbeat or a flopping in your chest ·

- Weakness ·

- Lightheadedness ·

- Confusion ·

- Shortness of breath ·

- Chest pain

- Sporadic. In this case it's called paroxysmal (par-ok-SIZ-mul) atrial fibrillation. You may have symptoms that come and go, lasting for a few minutes to hours and then stopping on their own. ·

- Chronic. With chronic atrial fibrillation, symptoms may last until they're treated.

Causes

To pump blood, your heart muscles must contract and relax in a coordinated rhythm. Contraction and relaxation are controlled by electrical signals that travel through your heart muscles.

Your heart consists of four chambers — two upper chambers (atria) and two lower chambers (ventricles). Within the upper right chamber of your heart (right atrium) is a group of cells called the sinus node. This is your heart's natural pacemaker. The sinus node produces the impulse that starts each heartbeat.Normally, the impulse travels first through the atria, then through a connecting pathway between the upper and lower chambers of your heart called the atrioventricular (AV) node. As the signal passes through the atria, they contract, pumping blood from your atria into the ventricles below. A split second later, as the signal passes through the AV node through the right and left bundle branches to the ventricles, the ventricles contract, pumping blood out to your body.In atrial fibrillation, the upper chambers of your heart (atria) experience chaotic electrical signals. As a result, they quiver. The AV node — the electrical connection between the atria and the ventricles — is overloaded with impulses trying to get through to the ventricles. The ventricles also beat rapidly, but not as rapidly as the atria. The reason is because the AV node is like a highway on-ramp — only so many cars can get on at one time. The result is an irregular and fast heart rhythm. The heart rate in atrial fibrillation may range from 100 to 175 beats a minute. The normal range for a heart rate is 60 to 100 beats a minute.

Possible causes

Abnormalities or damage to the heart's structure is the most common cause of atrial fibrillation. Diseases affecting the heart's valves or pumping system are common causes, as is long-term high blood pressure. However, some people who have atrial fibrillation don't have underlying structural heart disease, a condition called lone atrial fibrillation. In lone atrial fibrillation, the cause is often unclear. Serious complications are usually rare in lone atrial fibrillation.

Possible causes of atrial fibrillation include: ·

- High blood pressure ·

- Heart attacks ·

- Abnormal heart valves ·

- Congenital heart defects ·

- An overactive thyroid or other metabolic imbalance ·

- Exposure to stimulants, such as medications, caffeine or tobacco, or to alcohol ·

- Sick sinus syndrome — this occurs when the heart's natural pacemaker stops functioning properly ·

- Emphysema or other lung diseases ·

- Previous heart surgery ·

- Viral infections ·

- Stress due to pneumonia, surgery or other illnesses ·

- Sleep apnea

Risk factors:

- Age. The older you are, the greater your risk of developing atrial fibrillation. As you age, the electrical and structural properties of the atria can change. This may lead to the breakdown of the normal atrial rhythm.

- Heart disease. Anyone with heart disease, including valve problems, history of heart attack and heart surgery, faces an increased risk of atrial fibrillation.

- Other chronic conditions. People with thyroid problems, high blood pressure, sleep apnea and other medical problems have an elevated risk of atrial fibrillation.

- Alcohol use. Use of alcohol, especially binge drinking, can trigger an episode of atrial fibrillation.

- Family history. An increased risk of atrial fibrillation runs in some families. In some of these cases, specific genes have been identified as the likely cause of atrial fibrillation.

Screening and diagnosis

To make a diagnosis of atrial fibrillation, your doctor may do tests that involve the following:

- Electrocardiogram (ECG). Patches with wires (electrodes) are attached to your skin to measure electrical impulses given off by your heart. Impulses are recorded as waves displayed on a monitor or printed on paper.

- Holter monitor. This is a portable machine that records all of your heartbeats. You wear the monitor under your clothing. It records information about the electrical activity of your heart as you go about your normal activities for a day or two. You can press a button if you feel symptoms, and then your doctor can figure out what heart rhythm was present at that moment.

- Event recorder. This device is similar to a Holter monitor except all of your heartbeats are not recorded. There are two recorder types: One uses a phone to transmit signals from the recorder while you're experiencing symptoms. The other type is worn all the time (except while showering) for as long as a month. Event recorders are especially useful in diagnosing rhythm disturbances that occur at unpredictable times.

- Echocardiogram. In this test, sound waves are used to produce a video image of your heart. Sound waves are directed at your heart from a wand-like device (transducer) that's held on your chest. The sound waves that bounce off your heart are reflected back through your chest wall and processed electronically to provide video images of your heart in motion to detect underlying structural heart disease.

- Blood tests. These help your doctor rule out thyroid problems or blood chemistry abnormalities that may lead to atrial fibrillation.

Complications

Sometimes, atrial fibrillation can lead to the following complications:

- Stroke. In atrial fibrillation, the chaotic rhythm may cause blood to pool in your atria and form clots. If a blood clot forms, it could dislodge from your heart and travel to your brain. There it might block arterial blood flow, causing a stroke. The risk of stroke in atrial fibrillation depends on your age (you have a higher risk as you age) and on whether you have high blood pressure or a history of heart failure or previous stroke, and other factors. Most people with atrial fibrillation have a much greater risk of stroke than do those who don't have atrial fibrillation. Medications such as blood thinners can greatly lower your risk of stroke or damage to other organs caused by blood clots.

- Heart failure. Atrial fibrillation alone, especially if not controlled, may weaken the heart, leading to heart failure — a condition in which your heart can't circulate enough blood to meet your body's needs.

Treatment

Treatments for atrial fibrillation include medications and procedures that attempt to either reset the heart rhythm back to normal or control the heart rate so that the heart doesn't beat dangerously fast, though it may still beat irregularly. Treatments also include blood thinners to prevent blood clots.

The treatment option best for you will depend on how long you've had atrial fibrillation, how bothersome your symptoms are and the underlying cause of your atrial fibrillation. Generally, the goals of treating atrial fibrillation are to:

- Reset the rhythm — or — control the rate

- Prevent blood clots

The best strategy for you depends on many factors, including whether you have other problems with your heart and how well you tolerate the medications available to treat atrial fibrillation or control the rate. In some cases, you may need a more invasive treatment, such as catheter or surgical techniques.

Resetting the rhythm

Ideally, to treat atrial fibrillation, the heart rate and rhythm are reset to normal. This can be accomplished in some cases, depending on the underlying cause of atrial fibrillation and how long you've had it. To correct atrial fibrillation, doctors may be able to reset your heart to its regular rhythm (sinus rhythm) using a procedure called cardioversion. Cardioversion can be done in two ways:

- Cardioversion with drugs. This form of cardioversion uses medications called anti-arrhythmics to help restore normal sinus rhythm. Depending on your heart condition, your doctor may recommend trying intravenous or oral medications to return your heart to normal rhythm. This is often done in the hospital with continuous monitoring of your heart rate. If your heart rhythm returns to normal, your doctor often will prescribe the same anti-arrhythmic or a similar one long term to try to prevent recurrent spells of atrial fibrillation.

- Electrical cardioversion. In this brief procedure, an electrical shock is delivered to your heart through paddles or patches placed on your chest. The shock stops your heart's electrical activity for a split second. When your heart begins again, the hope is that it resumes its normal rhythm. The procedure is performed under anesthesia.

Maintaining normal rhythm

After electrical cardioversion, anti-arrhythmics often are prescribed to help prevent future episodes of atrial fibrillation. Commonly used medications include amiodarone (Cordarone, Pacerone), propafenone (Rythmol), procainamide (Procanbid) and dofetilide (Tikosyn). Although these drugs can help maintain sinus rhythm in many people, they can cause side effects, such as nausea, dizziness and fatigue. In rare instances, they may cause ventricular arrhythmias — life-threatening rhythm disturbances originating in the heart's lower chambers. These medications may be needed indefinitely. Unfortunately, even with medications, the chance of another episode of atrial fibrillation is high.

Rate control

Sometimes atrial fibrillation can't be converted back to a normal heart rhythm. Then the goal is to slow the heart rate (rate control). Traditionally, doctors have prescribed the medication digoxin (Lanoxin). It can control heart rate at rest but not as well during activity. Most people require additional or alternative medications, such as calcium channel blockers or beta blockers. In general, your heart rate should be between 60 and 100 beats a minute when you're at rest. Your doctor can give you guidelines for your maximal heart rate.

Some people may not be able to tolerate medications, or medications don't work to control the heart rate. In these cases, AV node ablation may be an option.

AV node ablation involves applying radio frequency energy to your atrioventricular (AV) node through a long, thin tube (catheter) to destroy this small area of tissue. The procedure prevents the atria from sending electrical impulses to the ventricles. The atria continue to fibrillate, though, and anticoagulant medication is still required. A pacemaker is then implanted to establish a normal rhythm.After AV node ablation, you'll need to continue to take anticoagulant medications to reduce the risk of stroke because your heart is still in atrial fibrillation.

Surgical and catheter interventions

Sometimes medications or cardioversion to control atrial fibrillation doesn't work. In those cases, your doctor may recommend a procedure to destroy the area of heart tissue responsible for the erratic electrical signals and restore your heart to a normal rhythm. These options can include:

- Radiofrequency catheter ablation. In many people who have atrial fibrillation and an otherwise normal heart, atrial fibrillation is caused by rapidly discharging triggers, or "hot spots." These hot spots are like abnormal pacemaker cells that fire so rapidly that the atria fibrillate. When present, these triggers are most commonly found in the pulmonary veins, the veins that return blood from the lungs to the heart. Radio frequency energy directed to these hot spots through a catheter (called radiofrequency ablation, pulmonary vein ablation or pulmonary vein isolation) may be used to destroy these hot spots, scarring the tissue and thereby disrupting the erratic electrical signals. This eliminates the arrhythmia without the need for medications or implantable devices. In some cases, additional spots are treated in your heart — depending on the electrical circuits found — and sometimes other types of catheters that can freeze the heart tissue (cryotherapy) are used.

Newer and less invasive techniques are being developed to create the atrial scar tissue. Doctors at some centers use radio frequency or cryotherapy applied to the outside surface of the heart through a small chest incision or through a scope placed into the chest cavity (thorascopic approach). Microwave, laser and ultrasound energy are also being studied as options to perform the maze procedure.

Preventing blood clots

Most people who have atrial fibrillation or who are undergoing certain treatment for atrial fibrillation are at especially high risk of blood clots that can lead to stroke. The risk is even higher if other heart disease is present along with atrial fibrillation. Your doctor may prescribe blood-thinning medications (anticoagulants), such as warfarin (Coumadin), dabigatran (Pradaxa) or aspirin, in addition to medications designed to treat your irregular heartbeat. Many people have spells of atrial fibrillation and don't even know it — so you may need lifelong anticoagulants even after your rhythm has been restored to normal.

Atrial flutter

Atrial flutter is similar to atrial fibrillation, but slower. If you have atrial flutter, the abnormal heart rhythm in your atria is more organized and less chaotic than in the abnormal patterns common with atrial fibrillation. Sometimes you may have atrial flutter that develops into atrial fibrillation and vice versa. The symptoms, causes and risk factors of atrial flutter are similar to atrial fibrillation. For example, strokes are a common concern in someone with atrial flutter.

One difference between atrial flutter and atrial fibrillation is that many people with atrial flutter respond better to treatment such as catheter ablation. As with atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter is usually not life-threatening when it's properly treated.

Self-care

There are some things you can do to try and prevent recurrent spells of atrial fibrillation. You may need to reduce or eliminate your intake of caffeine and alcohol, which can overstimulate the heart and trigger an episode of atrial fibrillation. It's also important to be careful when taking over-the-counter (OTC) medications. Some, such as cold medicines containing pseudoephedrine, contain stimulants that can trigger atrial fibrillation. Also, some OTC medications adversely interact with anti-arrhythmic medications.

You may need to make lifestyle changes that improve the overall health of your heart, especially to prevent or treat conditions such as high blood pressure. Your doctor may advise that you:

- Eat heart-healthy foods

- Reduce your salt intake, which can help lower blood pressure

- Increase your physical activity

- Quit smoking

- Avoid alcohol

Evolving View of Dangers of Atrial Fibrillation

By Barnaby J. Feder : NY Times Article : July 7, 2007

Atrial fibrillation occurs when stray electrical pulses set off muscle contractions that disrupt the coordinated top-to-bottom pumping action of the atria: two small blood-receiving chambers atop the heart.

That disruption can cause the atria to beat more than 300 times a minute and hamper the ability of the atria to carry out their function of filling the heart’s main pumps, the ventricles, with blood at the start of every heartbeat.

Fibrillation is more chaotic than another common rhythm irregularity known as atrial flutter. And it is harder to treat because it is far less likely than the flutter condition to be confined to the right atrium. The fibrillation can transform the normally coordinated pumping into a disorganized clash of localized mini-contractions that doctors say makes the muscle fibers of the atria look like a bucket of writhing worms.

Until the 1990s, atrial fibrillation was noted mostly for the number of false alarms it generated among patients who showed up at emergency rooms fearing they were having heart attacks.

Doctors viewed it as relatively benign because the most common symptoms — palpitations, dizziness and shortness of breath — were tolerable and often short-lived. No matter how bad patients may have felt, enough blood still flowed into the ventricles to sustain adequate circulation, as long as the ventricles remained healthy.

But doctors now recognize that atrial fibrillation allows blood to pool in the atria and form clots, which in turn may explain why such patients are prone to strokes and heart attacks.

About a third of strokes in patients 80 years or older are attributable to atrial fibrillation, and such strokes are more likely to be deadly than other types, according to studies summarized by Dr. Andrew E. Epstein, a researcher at the University of Alabama in Birmingham, at a meeting of heart rhythm specialists last month in Denver.

And research suggests the added burden that inefficient atrial pumping puts on the ventricles may contribute over time to heart failure.

Atrial Fibrillation FAQ

Some common questions asked by patients:

¶How will I know if I have atrial fibrillation?

You may not. Some patients feel no symptoms and the rapid contractions of the atria may end without any medical intervention. The diagnosis is normally made on the basis of an electrocardiogram.

¶What causes atrial fibrillation?

That is not yet clear and there may well be multiple possible contributors to various forms of the condition. Recent research suggests susceptibility may be inherited in some cases. Stress, smoking and heavy drinking, obesity and a range of illnesses also raise the risks of developing the condition and the likelihood that it will be more difficult to treat. The risk rises with aging and researchers estimate that 9 percent of people over 80 have the condition.

¶What are the most common problems with ablation?

In addition to the high rate of repeat procedures required because doctors have not successfully ablated all of the abnormal electrical activity, many patients report residual pain where diagnostic devices have been placed in their throat and leg pain or infections where the catheters were inserted into their veins. Because fibrillation often continues for many weeks after the procedure, doctors typically say it is impossible to know how successful an ablation has been until three months have passed.

¶Where are the best hospitals to get ablations?

Because the procedure is a difficult one, success rates often track the experience of the doctors doing it. But with new technology and techniques constantly being introduced and doctors occasionally moving, patients should look further than the hospital’s track record in deciding where to turn. In addition, there are cardiac centers in France, Italy and India that have performed the procedure more often and charge significantly less.

Heart Therapy Strains Efforts to Limit Costs

By Barnaby J. Feder : NY Time Article : July 7, 2007

The nation’s most common cardiac malfunction, once thought harmless but now seen as a potential killer, is testing the ability of regulators to keep up with medical treatments being carried out with scant evidence of long-term effectiveness.

With its episodes of rapid and irregular heartbeats, the condition — atrial fibrillation — afflicts at least 2.2 million people in the United States, according to government estimates. While some experience no symptoms and most others seem to suffer little more than weakness or shortness of breath, the condition is now recognized as a major source of strokes and a precursor to potentially fatal deterioration of the heart.

Already, Medicare and private insurers are spending billions of dollars annually to cope with atrial fibrillation, mostly on hospitalizations, tests and drugs unapproved for such patients. The number of patients is forecast to soar, and spending could climb even more rapidly if many of them receive what many doctors say is now their best hope for a cure — an expensive procedure known as catheter-based ablation.

Advocates of the procedure say it is less invasive than open-heart surgery — the only proven method for curing many patients — and in the long run more cost-effective than drugs, which generally offer temporary relief. Thousands of patients worldwide are estimated to have had the procedure done since 2000.

Federal regulators, however, have not approved as safe and effective any of the devices used. So hospitals and doctors are finding it difficult to be fully reimbursed for the procedure’s cost, which is generally calculated at $25,000 to $50,000.

With politicians and employers debating ways to tame the explosive growth in health care costs, such treatment stands out as another potentially budget-straining medical commitment.

“This is one of those areas where the practice of medicine has moved faster than the approval process,” said Daniel G. Schultz, head of the Center for Devices and Radiological Health at the Food and Drug Administration. “This is very high on our list of areas that need concerted attention.”

Dr. Schultz said the F.D.A. would soon schedule a public meeting with medical and industry experts to discuss what is known — and still needs to be known — about the welter of drugs and devices now being used without approval to treat atrial fibrillation.

Some of the biggest questions focus on ablation, which involves burning, freezing, or otherwise neutralizing the portions of the heart muscle where abnormal electrical pulses set off the irregular heartbeats. The technique aims to restore the ability of the two atria, situated at the top of the heart, to effectively gather blood and prime the ventricles, the heart’s main pumps.

The original form of atrial ablation, using surgical tools, is still employed, but almost always restricted to cases where the chest is already being cut open for heart valve replacement or other surgery. But most atrial ablations are now minimally invasive procedures using tiny devices mounted at the end of long, flexible plastic catheters that are threaded into the heart through veins.

Full-scale clinical trials have not yet demonstrated the long-term benefits from the catheter-based treatment. But, based on promising results from less rigorous studies, major medical societies have endorsed it. It is not uncommon for off-label drugs and devices to be used where doctors believe they can be more successful than any approved therapies.

Still, any situation where off-label therapies have become as widespread as they are in atrial fibrillation “spotlights where we lack good evidence of which patients can benefit from which therapies,” said Dr. Carolyn M. Clancy, director of the federal Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Gathering such data for atrial fibrillation could be especially challenging, she said, because the severity of the condition varies so much among patients and most have other health problems as well that can affect the risks and benefits of competing therapies.

Lacking regulatory guidelines, doctors currently use either experimental equipment or equipment that the F.D.A. has approved for other purposes, like destroying tumors or fixing other heart arrhythmias. While such off-label use of devices is legal for doctors, insurers are sometimes reluctant to cover it, and health care providers may have less legal protection from lawsuits if something goes wrong.

Typically, doctors and hospitals can bill Medicare or private insurers under codes used for somewhat similar cardiac procedures. But the physicians and hospitals say the reimbursements usually fall far short of full compensation for atrial ablation, which can take four hours or more to perform and requires an overnight stay at the hospital.

As a result, most of the procedures are being performed in teaching hospitals or other centers where doctors are on salary, or by practices that see it as a way to distinguish themselves in the broad market for heart patients. Atrial ablation already makes up 30 percent or more of the business of some specialist groups in competitive cardiac care markets like Florida, according to John O. Goodman, a consultant to cardiovascular medical groups.

Last month at a medical meeting in Denver, heart rhythm specialists distributed a statement endorsed by the American Heart Association, the American College of Cardiology and four other big American and European doctors’ groups that recommended atrial ablation as standard care for patients who do not respond to drug therapy.

Doctors say that the number of procedures would surge if the time involved could be cut to less than two hours — which would make current reimbursements less punishing — and if insurance coverage was enhanced.

“It’s a simple fact that if we don’t get paid for something, our desire to do it is going to be much, much less,” Dr. Richard I. Fogel, a cardiologist at the Care Group in Indianapolis, said at the Denver meeting.

Each catheter-based procedure requires disposable equipment that can cost $4,000 to $5,000 a patient.

According to Alexander K. Arrow, an analyst at Lazard Capital Markets, atrial fibrillation ablation procedures already account for more than $200 million of the $1 billion annual market for cardiac ablation equipment, which is also used for other kinds of arrhythmia.

Companies in the field range from small start-ups to industry giants like St. Jude Medical and Johnson & Johnson. Estimates of the potential market for atrial ablation devices in the next decade range from $1.5 billion to nearly $5 billion, according to Medtech Insight, a market research company in Newport Beach, Calif.

Those projections include sophisticated diagnostic and computerized-mapping equipment, which is often sold by the same companies. Some leading medical centers also use expensive robotic guidance systems from companies like Hansen Medical and Stereotaxis.

The technology’s advocates say that unlike drugs, which at best help patients manage the symptoms of atrial fibrillation and reduce the risks, ablation saves money in the long run by curing the condition. Drug regimes, which vary widely, can be kept to under $1,000 annually for many patients by prescribing generic drugs, but ablation advocates say the true cost of relying on drugs includes more frequent hospitalizations, lifestyle restrictions for patients on blood thinners and poorer outcomes.

On the other hand, some regulators and many doctors contend that ablation “cure” rates, while promising, may have been exaggerated by shortcomings in the designs of the clinical trials that supplied the data.

And they say many patients do not fully understand the likelihood — at least 30 percent according to many studies — that they will need subsequent ablations. Patients may also have to continue taking some or all of their drugs or, in some cases, need to have a pacemaker implanted. Moreover, about 2 percent of patients suffer strokes or other serious complications during procedures.

Still, every major ablation center can cite remarkable success stories. Take L. Jay Schweitzer, 57, a former art teacher from Pine Island, N.Y., who for two decades had increasingly frequent and severe episodes of fibrillation, treated with drugs, before having an ablation two years ago.

“I’ve never had anything more than a brief flutter since then,” Mr. Schweitzer said in a recent phone call from Cape May, N.J., where he was on a surfing vacation.

Mr. Schweitzer’s generally good health and relative youth made him an ideal candidate for the procedure, according to Dr. Larry A. Chinitz, a specialist at the New York University Medical Center, who performed it. Success rates appear to be higher for patients with less frequent and shorter episodes of fibrillation.

The drugs that are used as the first type of treatment for patients like Mr. Schweitzer are prescribed “off label” because, in the absence of adequate clinical tests, they have not gained approval for atrial fibrillation. Developed for other heart problems, they include anti-arrythmia agents like amiodarone and generic sotalol, along with anti-clotting drugs, like warfarin. But doctors and patients alike have been dismayed by the side effects of the drugs and their limited long-term effectiveness in controlling atrial fibrillation.

Amiodarone can damage lungs and the liver, cause Parkinson’s-like muscle tremors, and contribute to heart failure.

Warfarin, often prescribed as Coumadin, a Bristol-Myers Squibb brand, raises the risk of excessive bleeding in any case of injury.

“The medications to control it are nasty drugs,” said Dr. Mark W. Connolly, head of the heart surgery group at St. Michael’s Medical Center in Newark. “Many patients don’t tolerate them well, especially if they are active.”

No wonder doctors expect demand for atrial ablation to grow despite the uncertainties and costs. Dr. Andrea Natale, head of the Cleveland Clinic program, said that he was booked into 2008 and that the waiting list for doctors working under him runs four to six months.

And Dr. Chinitz, the New York University specialist who performed Mr. Schweitzer’s procedure, said his backlog was several months and growing.

“Patients really want this,” he said.

- You should know how to monitor your own pulse rate and rhythm

- You should know the signs and symptoms of a stroke

- If you are on warfarin/Coumadin you should have your PT/INR checked on a monthly basis once stabilized.

The newer agents to prevent blood clots are now available and NO regular blood test are needed while on these agents.

The newer agents to prevent blood clots are now available and NO regular blood test are needed while on these agents.