- RETIREMENT ANNOUNCEMENT

- HOME PAGE

- "MYCHART" the new patient portal

- BELMONT MEDICAL ASSOCIATES

- MOUNT AUBURN HOSPITAL

- EMERGENCIES

- PRACTICE PHILOSOPHY

- MY RESUME

- TELEMEDICINE CONSULTATION

- CONTACT ME

- LAB RESULTS

- ePRESCRIPTIONS

- eREFERRALS

- RECORD RELEASE

- MEDICAL SCRIBE

- PHYSICIAN ASSISTANT (PA)

- Medicare Annual Wellness Visit

- Case management/Social work

- Quality Care Measures

- Emergency closing notice

- FEEDBACK

- Talking to your doctor

- Choosing..... and losing a doctor

- INDEX A - Z

- ALLERGIC REACTIONS

- Alternative Medicine

- Alzheimer's Disease

- Bladder Problems

- Blood disorders

- Cancer Concerns

- GENETIC TESTING FOR HEREDITARY CANCER

- Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

- Controversial Concerns

- CPR : Learn and save a life

- CRP : Inflammatory marker

- Diabetes Management

- Dizziness, Vertigo,Tinnitus and Hearing Loss

- EXERCISE

- FEMALE HEALTH

-

GASTROINTESTINAL topics

- Appendicitis

- BRAT diet

- Celiac Disease or Sprue

- Crohn's Disease

- Gastroenterologists for Colon Cancer Screening

- Colonoscopy PREP

- Constipation

- Gluten sensitivity, but not celiac disease

- Heartburn and GERD

- Hemorrhoids and Anal fissure

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- NASH : Non Alcoholic Steato Hepatitis

- FEET PROBLEMS

- HEART RELATED topics

-

INFECTIOUS DISEASES

- Antibiotic Resistance

- Cat bites >

- Clostridia difficile infection - the "antibiotic associated germ"

- CORONA VIRUS

- Dengue Fever and Chikungunya Fever

- Food borne illnesses

- Shingles Vaccine

- Hepatitis B

- Hepatitis C

- Herpes

- Influenza

- Helicobacter pylori - the "ulcer germ"

- HIV Screening

- Lyme and other tick borne diseases

- Measles

- Meningitis

- MRSA (Staph infection)

- Norovirus

- Sexually Transmitted Diseases

- Shingles (Herpes Zoster)

- Sinusitis

- West Nile Virus

- Whooping Cough (Pertussis)

- Zika virus and pregnancy

- INSURANCE related topics

- KIDNEY STONES

- LEG CRAMPS

- LIBRARY for patients

- LIFE DECISIONS

- MALE HEALTH

- Medication/Drug side effects

- MEDICAL MARIJUANA

- MENTAL HEALTH

- Miscellaneous Articles

-

NUTRITION - EXERCISE - WEIGHT

- Cholesterol : New guidelines for treatment

- Advice to lower your cholesterol

- Cholesterol : Control

- Cholesterol : Raising your HDL Level

- Exercise

- Food : Making Smart Choices

- Food : Making Poor Choices

- Food : Grape Fruit and Drug Interaction

- Food : Vitamins, Minerals and Supplements

- Omega 3 fatty acids

- Vitamin B12 deficiency

- Vitamin D

- Weight Loss

- ORTHOPEDICS

- PAIN

- PATIENTS' RIGHTS

- SKIN

- SLEEP

- SMOKING

- STROKE

- THYROID

- SUBSTANCE ABUSE

- Travel and Vaccination

- TREMOR

- Warfarin Anticoagulation

- OTHER STUFF FOLLOWS

- Fact or Opinion?

- Hippocratic Oath

- FREE ADVICE.......for what its worth!

- LAUGHTER.....is the best medicine

- Physicians Pet Peeves

- PHOTO ALBUM - its not all work!

- Cape Town, South Africa

- Tribute page

- The 100 Club

- Free Wi-Fi

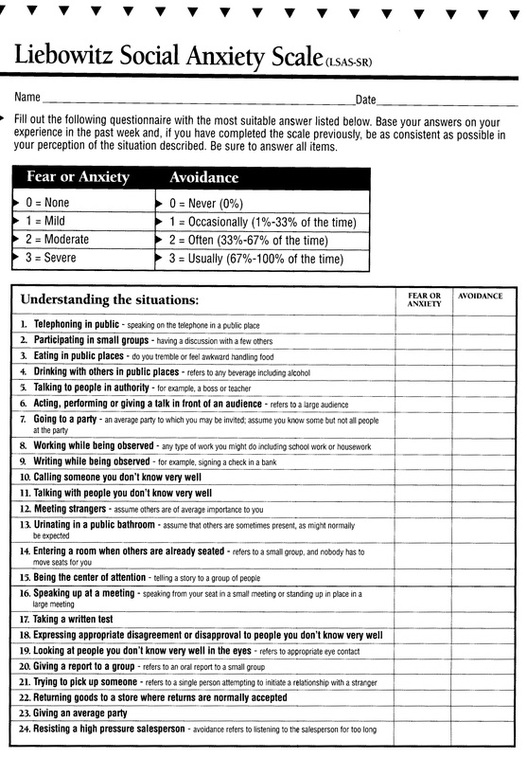

SOCIAL ANXIETY ASSESSMENT TEST

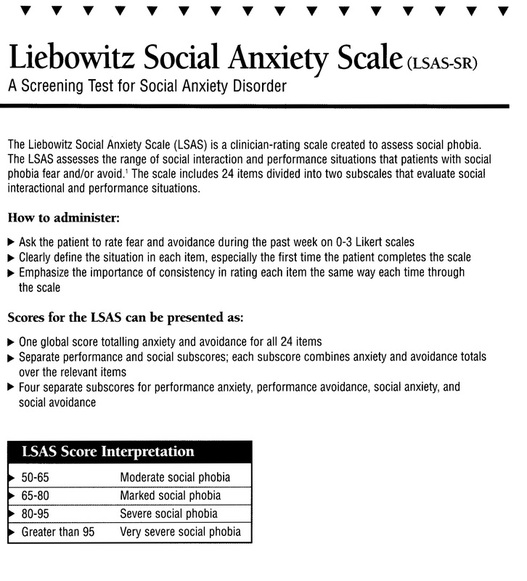

Anxiety Disorders

http://www.healthline.com/health/anxiety/effects-on-body

Introduction

Anxiety Disorders affect about 40 million American adults age 18 years and older (about 18%) in a given year, causing them to be filled with fearfulness and uncertainty. Unlike the relatively mild, brief anxiety caused by a stressful event (such as speaking in public or a first date), anxiety disorders last at least 6 months and can get worse if they are not treated. Anxiety disorders commonly occur along with other mental or physical illnesses, including alcohol or substance abuse, which may mask anxiety symptoms or make them worse. In some cases, these other illnesses need to be treated before a person will respond to treatment for the anxiety disorder.

Effective therapies for anxiety disorders are available, and research is uncovering new treatments that can help most people with anxiety disorders lead productive, fulfilling lives. If you think you have an anxiety disorder, you should seek information and treatment right away.

Each anxiety disorder has different symptoms, but all the symptoms cluster around excessive, irrational fear and dread.

Panic Disorder

"For me, a panic attack is almost a violent experience. I feel disconnected from reality. I feel like I'm losing control in a very extreme way. My heart pounds really hard, I feel like I can't get my breath, and there's an overwhelming feeling that things are crashing in on me."

"It started 10 years ago, when I had just graduated from college and started a new job. I was sitting in a business seminar in a hotel and this thing came out of the blue. I felt like I was dying."

"In between attacks there is this dread and anxiety that it's going to happen again. I'm afraid to go back to places where I've had an attack. Unless I get help, there soon won't be anyplace where I can go and feel safe from panic."

Panic disorder is a real illness that can be successfully treated. It is characterized by sudden attacks of terror, usually accompanied by a pounding heart, sweatiness, weakness, faintness, or dizziness. During these attacks, people with panic disorder may flush or feel chilled; their hands may tingle or feel numb; and they may experience nausea, chest pain, or smothering sensations. Panic attacks usually produce a sense of unreality, a fear of impending doom, or a fear of losing control.

A fear of one's own unexplained physical symptoms is also a symptom of panic disorder. People having panic attacks sometimes believe they are having heart attacks, losing their minds, or on the verge of death. They can't predict when or where an attack will occur, and between episodes many worry intensely and dread the next attack.

Panic attacks can occur at any time, even during sleep. An attack usually peaks within 10 minutes, but some symptoms may last much longer. Panic disorder affects about 6 million American adults1 and is twice as common in women as men. Panic attacks often begin in late adolescence or early adulthood, but not everyone who experiences panic attacks will develop panic disorder. Many people have just one attack and never have another. The tendency to develop panic attacks appears to be inherited.

People who have full-blown, repeated panic attacks can become very disabled by their condition and should seek treatment before they start to avoid places or situations where panic attacks have occurred. For example, if a panic attack happened in an elevator, someone with panic disorder may develop a fear of elevators that could affect the choice of a job or an apartment, and restrict where that person can seek medical attention or enjoy entertainment.

Some people's lives become so restricted that they avoid normal activities, such as grocery shopping or driving. About one-third become housebound or are able to confront a feared situation only when accompanied by a spouse or other trusted person. 2 When the condition progresses this far, it is called agoraphobia, or fear of open spaces.

Early treatment can often prevent agoraphobia, but people with panic disorder may sometimes go from doctor to doctor for years and visit the emergency room repeatedly before someone correctly diagnoses their condition. This is unfortunate, because panic disorder is one of the most treatable of all the anxiety disorders, responding in most cases to certain kinds of medication or certain kinds of cognitive psychotherapy, which help change thinking patterns that lead to fear and anxiety.

Panic disorder is often accompanied by other serious problems, such as depression, drug abuse, or alcoholism.These conditions need to be treated separately. Symptoms of depression include feelings of sadness or hopelessness, changes in appetite or sleep patterns, low energy, and difficulty concentrating. Most people with depression can be effectively treated with antidepressant medications, certain types of psychotherapy, or a combination of the two.

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

"I couldn't do anything without rituals. They invaded every aspect of my life. Counting really bogged me down. I would wash my hair three times as opposed to once because three was a good luck number and one wasn't. It took me longer to read because I'd count the lines in a paragraph. When I set my alarm at night, I had to set it to a number that wouldn't add up to a 'bad' number."

"I knew the rituals didn't make sense, and I was deeply ashamed of them, but I couldn't seem to overcome them until I had therapy."

"Getting dressed in the morning was tough, because I had a routine, and if I didn't follow the routine, I'd get anxious and would have to get dressed again. I always worried that if I didn't do something, my parents were going to die. I'd have these terrible thoughts of harming my parents. That was completely irrational, but the thoughts triggered more anxiety and more senseless behavior. Because of the time I spent on rituals, I was unable to do a lot of things that were important to me."

People with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) have persistent, upsetting thoughts (obsessions) and use rituals (compulsions) to control the anxiety these thoughts produce. Most of the time, the rituals end up controlling them.

For example, if people are obsessed with germs or dirt, they may develop a compulsion to wash their hands over and over again. If they develop an obsession with intruders, they may lock and relock their doors many times before going to bed. Being afraid of social embarrassment may prompt people with OCD to comb their hair compulsively in front of a mirror-sometimes they get "caught" in the mirror and can't move away from it. Performing such rituals is not pleasurable. At best, it produces temporary relief from the anxiety created by obsessive thoughts.

Other common rituals are a need to repeatedly check things, touch things (especially in a particular sequence), or count things. Some common obsessions include having frequent thoughts of violence and harming loved ones, persistently thinking about performing sexual acts the person dislikes, or having thoughts that are prohibited by religious beliefs. People with OCD may also be preoccupied with order and symmetry, have difficulty throwing things out (so they accumulate), or hoard unneeded items.

Healthy people also have rituals, such as checking to see if the stove is off several times before leaving the house. The difference is that people with OCD perform their rituals even though doing so interferes with daily life and they find the repetition distressing. Although most adults with OCD recognize that what they are doing is senseless, some adults and most children may not realize that their behavior is out of the ordinary.

OCD affects about 2.2 million American adults, and the problem can be accompanied by eating disorders, It strikes men and women in roughly equal numbers and usually appears in childhood, adolescence, or early adulthood. One-third of adults with OCD develop symptoms as children, and research indicates that OCD might run in families.

The course of the disease is quite varied. Symptoms may come and go, ease over time, or get worse. If OCD becomes severe, it can keep a person from working or carrying out normal responsibilities at home. People with OCD may try to help themselves by avoiding situations that trigger their obsessions, or they may use alcohol or drugs to calm themselves.

OCD usually responds well to treatment with certain medications and/or exposure-based psychotherapy, in which people face situations that cause fear or anxiety and become less sensitive (desensitized) to them. NIMH is supporting research into new treatment approaches for people whose OCD does not respond well to the usual therapies. These approaches include combination and augmentation (add-on) treatments, as well as modern techniques such as deep brain stimulation.

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

"I was raped when I was 25 years old. For a long time, I spoke about the rape as though it was something that happened to someone else. I was very aware that it had happened to me, but there was just no feeling."

"Then I started having flashbacks. They kind of came over me like a splash of water. I would be terrified. Suddenly I was reliving the rape. Every instant was startling. I wasn't aware of anything around me, I was in a bubble, just kind of floating. And it was scary. Having a flashback can wring you out."

"The rape happened the week before Thanksgiving, and I can't believe the anxiety and fear I feel every year around the anniversary date. It's as though I've seen a werewolf. I can't relax, can't sleep, don't want to be with anyone. I wonder whether I'll ever be free of this terrible problem."

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) develops after a terrifying ordeal that involved physical harm or the threat of physical harm. The person who develops PTSD may have been the one who was harmed, the harm may have happened to a loved one, or the person may have witnessed a harmful event that happened to loved ones or strangers.

PTSD was first brought to public attention in relation to war veterans, but it can result from a variety of traumatic incidents, such as mugging, rape, torture, being kidnapped or held captive, child abuse, car accidents, train wrecks, plane crashes, bombings, or natural disasters such as floods or earthquakes.

People with PTSD may startle easily, become emotionally numb (especially in relation to people with whom they used to be close), lose interest in things they used to enjoy, have trouble feeling affectionate, be irritable, become more aggressive, or even become violent. They avoid situations that remind them of the original incident, and anniversaries of the incident are often very difficult. PTSD symptoms seem to be worse if the event that triggered them was deliberately initiated by another person, as in a mugging or a kidnapping. Most people with PTSD repeatedly relive the trauma in their thoughts during the day and in nightmares when they sleep. These are called flashbacks. Flashbacks may consist of images, sounds, smells, or feelings, and are often triggered by ordinary occurrences, such as a door slamming or a car backfiring on the street. A person having a flashback may lose touch with reality and believe that the traumatic incident is happening all over again.

Not every traumatized person develops full-blown or even minor PTSD. Symptoms usually begin within 3 months of the incident but occasionally emerge years afterward. They must last more than a month to be considered PTSD. The course of the illness varies. Some people recover within 6 months, while others have symptoms that last much longer. In some people, the condition becomes chronic.

PTSD affects about 7.7 million American adults, but it can occur at any age, including childhood. Women are more likely to develop PTSD than men, and there is some evidence that susceptibility to the disorder may run in families. PTSD is often accompanied by depression, substance abuse, or one or more of the other anxiety disorders.

Certain kinds of medication and certain kinds of psychotherapy usually treat the symptoms of PTSD very effectively.

Social Phobia (Social Anxiety Disorder)

"In any social situation, I felt fear. I would be anxious before I even left the house, and it would escalate as I got closer to a college class, a party, or whatever. I would feel sick in my stomach-it almost felt like I had the flu. My heart would pound, my palms would get sweaty, and I would get this feeling of being removed from myself and from everybody else."

"When I would walk into a room full of people, I'd turn red and it would feel like everybody's eyes were on me. I was embarrassed to stand off in a corner by myself, but I couldn't think of anything to say to anybody. It was humiliating. I felt so clumsy, I couldn't wait to get out."

Social phobia, also called social anxiety disorder, is diagnosed when people become overwhelmingly anxious and excessively self-conscious in everyday social situations. People with social phobia have an intense, persistent, and chronic fear of being watched and judged by others and of doing things that will embarrass them. They can worry for days or weeks before a dreaded situation. This fear may become so severe that it interferes with work, school, and other ordinary activities, and can make it hard to make and keep friends.

While many people with social phobia realize that their fears about being with people are excessive or unreasonable, they are unable to overcome them. Even if they manage to confront their fears and be around others, they are usually very anxious beforehand, are intensely uncomfortable throughout the encounter, and worry about how they were judged for hours afterward.

Social phobia can be limited to one situation (such as talking to people, eating or drinking, or writing on a blackboard in front of others) or may be so broad (such as in generalized social phobia) that the person experiences anxiety around almost anyone other than the family.

Physical symptoms that often accompany social phobia include blushing, profuse sweating, trembling, nausea, and difficulty talking. When these symptoms occur, people with PTSD feel as though all eyes are focused on them.

Social phobia affects about 15 million American adults. Women and men are equally likely to develop the disorder, which usually begins in childhood or early adolescence. There is some evidence that genetic factors are involved. Social phobia is often accompanied by other anxiety disorders or depression,and substance abuse may develop if people try to self-medicate their anxiety.

Social phobia can be successfully treated with certain kinds of psychotherapy or medications.

Specific Phobias

"I'm scared to death of flying, and I never do it anymore. I used to start dreading a plane trip a month before I was due to leave. It was an awful feeling when that airplane door closed and I felt trapped. My heart would pound, and I would sweat bullets. When the airplane would start to ascend, it just reinforced the feeling that I couldn't get out. When I think about flying, I picture myself losing control, freaking out, and climbing the walls, but of course I never did that. I'm not afraid of crashing or hitting turbulence. It's just that feeling of being trapped. Whenever I've thought about changing jobs, I've had to think, "Would I be under pressure to fly?" These days I only go places where I can drive or take a train. My friends always point out that I couldn't get off a train traveling at high speeds either, so why don't trains bother me? I just tell them it isn't a rational fear."

A specific phobia is an intense fear of something that poses little or no actual danger. Some of the more common specific phobias are centered around closed-in places, heights, escalators, tunnels, highway driving, water, flying, dogs, and injuries involving blood. Such phobias aren't just extreme fear; they are irrational fear of a particular thing. You may be able to ski the world's tallest mountains with ease but be unable to go above the 5th floor of an office building. While adults with phobias realize that these fears are irrational, they often find that facing, or even thinking about facing, the feared object or situation brings on a panic attack or severe anxiety.

Specific phobias affect an estimated 19.2 million adult Americans and are twice as common in women as men.They usually appear in childhood or adolescence and tend to persist into adulthood. The causes of specific phobias are not well understood, but there is some evidence that the tendency to develop them may run in families.

If the feared situation or feared object is easy to avoid, people with specific phobias may not seek help; but if avoidance interferes with their careers or their personal lives, it can become disabling and treatment is usually pursued.

Specific phobias respond very well to carefully targeted psychotherapy.

Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD)

"I always thought I was just a worrier. I'd feel keyed up and unable to relax. At times it would come and go, and at times it would be constant. It could go on for days. I'd worry about what I was going to fix for a dinner party, or what would be a great present for somebody. I just couldn't let something go."

"I'd have terrible sleeping problems. There were times I'd wake up wired in the middle of the night. I had trouble concentrating, even reading the newspaper or a novel. Sometimes I'd feel a little lightheaded. My heart would race or pound. And that would make me worry more. I was always imagining things were worse than they really were: when I got a stomachache, I'd think it was an ulcer."

People with generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) go through the day filled with exaggerated worry and tension, even though there is little or nothing to provoke it. They anticipate disaster and are overly concerned about health issues, money, family problems, or difficulties at work. Sometimes just the thought of getting through the day produces anxiety.

GAD is diagnosed when a person worries excessively about a variety of everyday problems for at least 6 months.People with GAD can't seem to get rid of their concerns, even though they usually realize that their anxiety is more intense than the situation warrants. They can't relax, startle easily, and have difficulty concentrating. Often they have trouble falling asleep or staying asleep. Physical symptoms that often accompany the anxiety include fatigue, headaches, muscle tension, muscle aches, difficulty swallowing, trembling, twitching, irritability, sweating, nausea, lightheadedness, having to go to the bathroom frequently, feeling out of breath, and hot flashes.

When their anxiety level is mild, people with GAD can function socially and hold down a job. Although they don't avoid certain situations as a result of their disorder, people with GAD can have difficulty carrying out the simplest daily activities if their anxiety is severe.

GAD affects about 6.8 million adult Americans and about twice as many women as men. The disorder comes on gradually and can begin across the life cycle, though the risk is highest between childhood and middle age. It is diagnosed when someone spends at least 6 months worrying excessively about a number of everyday problems. There is evidence that genes play a modest role in GAD.

Other anxiety disorders, depression, or substance abuseoften accompany GAD, which rarely occurs alone. GAD is commonly treated with medication or cognitive-behavioral therapy, but co-occurring conditions must also be treated using the appropriate therapies.

Treatment of Anxiety Disorders

In general, anxiety disorders are treated with medication, specific types of psychotherapy, or both.Treatment choices depend on the problem and the person's preference. Before treatment begins, a doctor must conduct a careful diagnostic evaluation to determine whether a person's symptoms are caused by an anxiety disorder or a physical problem. If an anxiety disorder is diagnosed, the type of disorder or the combination of disorders that are present must be identified, as well as any coexisting conditions, such as depression or substance abuse. Sometimes alcoholism, depression, or other coexisting conditions have such a strong effect on the individual that treating the anxiety disorder must wait until the coexisting conditions are brought under control.

People with anxiety disorders who have already received treatment should tell their current doctor about that treatment in detail. If they received medication, they should tell their doctor what medication was used, what the dosage was at the beginning of treatment, whether the dosage was increased or decreased while they were under treatment, what side effects occurred, and whether the treatment helped them become less anxious. If they received psychotherapy, they should describe the type of therapy, how often they attended sessions, and whether the therapy was useful.

Often people believe that they have "failed" at treatment or that the treatment didn't work for them when, in fact, it was not given for an adequate length of time or was administered incorrectly. Sometimes people must try several different treatments or combinations of treatment before they find the one that works for them.

How to Help Someone Having a Panic Attack

This article details the best current measures to take to relieve someone suffering a panic attack. Come to the support of friends, family, and other members of the community when they suffer from an unexpected panic attack.

Steps other anxiety disorders, or depression.

Tips

Warnings

Medications

Medication will not cure anxiety disorders, but it can keep them under control while the person receives psychotherapy. Medication must be prescribed by physicians, usually psychiatrists, who can either offer psychotherapy themselves or work as a team with psychologists, social workers, or counselors who provide psychotherapy. The principal medications used for anxiety disorders are antidepressants, anti-anxiety drugs, and beta-blockers to control some of the physical symptoms. With proper treatment, many people with anxiety disorders can lead normal, fulfilling lives.

Antidepressants

Antidepressants were developed to treat depression but are also effective for anxiety disorders. Although these medications begin to alter brain chemistry after the very first dose, their full effect requires a series of changes to occur; it is usually about 4 to 6 weeks before symptoms start to fade. It is important to continue taking these medications long enough to let them work.

SSRIs

Some of the newest antidepressants are called selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, or SSRIs. SSRIs alter the levels of the neurotransmitter serotonin in the brain, which, like other neurotransmitters, helps brain cells communicate with one another.

Fluoxetine (Prozac®), sertraline (Zoloft®), escitalopram (Lexapro®), paroxetine (Paxil®), and citalopram (Celexa®) are some of the SSRIs commonly prescribed for panic disorder, OCD, PTSD, and social phobia. SSRIs are also used to treat panic disorder when it occurs in combination with OCD, social phobia, or depression. Venlafaxine (Effexor®), a drug closely related to the SSRIs, is used to treat GAD. These medications are started at low doses and gradually increased until they have a beneficial effect.

SSRIs have fewer side effects than older antidepressants, but they sometimes produce slight nausea or jitters when people first start to take them. These symptoms fade with time. Some people also experience sexual dysfunction with SSRIs, which may be helped by adjusting the dosage or switching to another SSRI.

Tricyclics

Tricyclics are older than SSRIs and work as well as SSRIs for anxiety disorders other than OCD. They are also started at low doses that are gradually increased. They sometimes cause dizziness, drowsiness, dry mouth, and weight gain, which can usually be corrected by changing the dosage or switching to another tricyclic medication.

Tricyclics include imipramine (Tofranil®), which is prescribed for panic disorder and GAD, and clomipramine (Anafranil®), which is the only tricyclic antidepressant useful for treating OCD.

MAOIs

Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) are the oldest class of antidepressant medications. The MAOIs most commonly prescribed for anxiety disorders are phenelzine (Nardil®), followed by tranylcypromine (Parnate®), and isocarboxazid (Marplan®), which are useful in treating panic disorder and social phobia. People who take MAOIs cannot eat a variety of foods and beverages (including cheese and red wine) that contain tyramine or take certain medications, including some types of birth control pills, pain relievers (such as Advil®, Motrin®, or Tylenol®), cold and allergy medications, and herbal supplements; these substances can interact with MAOIs to cause dangerous increases in blood pressure. The development of a new MAOI skin patch may help lessen these risks. MAOIs can also react with SSRIs to produce a serious condition called "serotonin syndrome," which can cause confusion, hallucinations, increased sweating, muscle stiffness, seizures, changes in blood pressure or heart rhythm, and other potentially life-threatening conditions.

Anti-Anxiety Drugs

High-potency benzodiazepines combat anxiety and have few side effects other than drowsiness. Because people can get used to them and may need higher and higher doses to get the same effect, benzodiazepines are generally prescribed for short periods of time, especially for people who have abused drugs or alcohol and who become dependent on medication easily. One exception to this rule is people with panic disorder, who can take benzodiazepines for up to a year without harm.

Clonazepam (Klonopin®) is used for social phobia and GAD, lorazepam (Ativan®) is helpful for panic disorder, and alprazolam (Xanax®) is useful for both panic disorder and GAD.

Some people experience withdrawal symptoms if they stop taking benzodiazepines abruptly instead of tapering off, and anxiety can return once the medication is stopped. These potential problems have led some physicians to shy away from using these drugs or to use them in inadequate doses.

Buspirone (Buspar®), an azapirone, is a newer anti-anxiety medication used to treat GAD. Possible side effects include dizziness, headaches, and nausea. Unlike benzodiazepines, buspirone must be taken consistently for at least 2 weeks to achieve an anti-anxiety effect.

Beta-Blockers

Beta-blockers, such as propranolol (Inderal®), which is used to treat heart conditions, can prevent the physical symptoms that accompany certain anxiety disorders, particularly social phobia. When a feared situation can be predicted (such as giving a speech), a doctor may prescribe a beta-blocker to keep physical symptoms of anxiety under control.

Psychotherapy

Psychotherapy involves talking with a trained mental health professional, such as a psychiatrist, psychologist, social worker, or counselor, to discover what caused an anxiety disorder and how to deal with its symptoms.

Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy Cognitive-

Behavioral Therapy Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is very useful in treating anxiety disorders. The cognitive part helps people change the thinking patterns that support their fears, and the behavioral part helps people change the way they react to anxiety-provoking situations.

For example, CBT can help people with panic disorder learn that their panic attacks are not really heart attacks and help people with social phobia learn how to overcome the belief that others are always watching and judging them. When people are ready to confront their fears, they are shown how to use exposure techniques to desensitize themselves to situations that trigger their anxieties.

People with OCD who fear dirt and germs are encouraged to get their hands dirty and wait increasing amounts of time before washing them. The therapist helps the person cope with the anxiety that waiting produces; after the exercise has been repeated a number of times, the anxiety diminishes. People with social phobia may be encouraged to spend time in feared social situations without giving in to the temptation to flee and to make small social blunders and observe how people respond to them. Since the response is usually far less harsh than the person fears, these anxieties are lessened. People with PTSD may be supported through recalling their traumatic event in a safe situation, which helps reduce the fear it produces. CBT therapists also teach deep breathing and other types of exercises to relieve anxiety and encourage relaxation.

Exposure-based behavioral therapy has been used for many years to treat specific phobias. The person gradually encounters the object or situation that is feared, perhaps at first only through pictures or tapes, then later face-to-face. Often the therapist will accompany the person to a feared situation to provide support and guidance.

CBT is undertaken when people decide they are ready for it and with their permission and cooperation. To be effective, the therapy must be directed at the person's specific anxieties and must be tailored to his or her needs. There are no side effects other than the discomfort of temporarily increased anxiety.

CBT or behavioral therapy often lasts about 12 weeks. It may be conducted individually or with a group of people who have similar problems. Group therapy is particularly effective for social phobia. Often "homework" is assigned for participants to complete between sessions. There is some evidence that the benefits of CBT last longer than those of medication for people with panic disorder, and the same may be true for OCD, PTSD, and social phobia. If a disorder recurs at a later date, the same therapy can be used to treat it successfully a second time.

Medication can be combined with psychotherapy for specific anxiety disorders, and this is the best treatment approach for many people.

TAKING MEDICATIONS

Before taking medication for an anxiety disorder:

If you think you have an anxiety disorder, the first person you should see is your family doctor. A physician can determine whether the symptoms that alarm you are due to an anxiety disorder, another medical condition, or both.

If an anxiety disorder is diagnosed, the next step is usually seeing a mental health professional. The practitioners who are most helpful with anxiety disorders are those who have training in cognitive-behavioral therapy and/or behavioral therapy, and who are open to using medication if it is needed.

You should feel comfortable talking with the mental health professional you choose. If you do not, you should seek help elsewhere. Once you find a mental health professional with whom you are comfortable, the two of you should work as a team and make a plan to treat your anxiety disorder together.

Remember that once you start on medication, it is important not to stop taking it abruptly. Certain drugs must be tapered off under the supervision of a doctor or bad reactions can occur. Make sure you talk to the doctor who prescribed your medication before you stop taking it. If you are having trouble with side effects, it's possible that they can be eliminated by adjusting how much medication you take and when you take it.

Most insurance plans, including health maintenance organizations (HMOs), will cover treatment for anxiety disorders. Check with your insurance company and find out. If you don't have insurance, the Health and Human Services division of your county government may offer mental health care at a public mental health center that charges people according to how much they are able to pay. If you are on public assistance, you may be able to get care through your state Medicaid plan.

Ways to Make Treatment More Effective

Many people with anxiety disorders benefit from joining a self-help or support group and sharing their problems and achievements with others. Internet chat rooms can also be useful in this regard, but any advice received over the Internet should be used with caution, as Internet acquaintances have usually never seen each other and false identities are common. Talking with a trusted friend or member of the clergy can also provide support, but it is not a substitute for care from a mental health professional.

Stress management techniques and meditation can help people with anxiety disorders calm themselves and may enhance the effects of therapy. There is preliminary evidence that aerobic exercise may have a calming effect. Since caffeine, certain illicit drugs, and even some over-the-counter cold medications can aggravate the symptoms of anxiety disorders, they should be avoided. Check with your physician or pharmacist before taking any additional medications.

The family is very important in the recovery of a person with an anxiety disorder. Ideally, the family should be supportive but not help perpetuate their loved one's symptoms. Family members should not trivialize the disorder or demand improvement without treatment. If your family is doing either of these things, you may want to show them this booklet so they can become educated allies and help you succeed in therapy.

Role of Research in Improving the Understanding and Treatment of Anxiety Disorders

NIMH supports research into the causes, diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of anxiety disorders and other mental illnesses. Scientists are looking at what role genes play in the development of these disorders and are also investigating the effects of environmental factors such as pollution, physical and psychological stress, and diet. In addition, studies are being conducted on the "natural history" (what course the illness takes without treatment) of a variety of individual anxiety disorders, combinations of anxiety disorders, and anxiety disorders that are accompanied by other mental illnesses such as depression.

Scientists currently think that, like heart disease and type 1 diabetes, mental illnesses are complex and probably result from a combination of genetic, environmental, psychological, and developmental factors. For instance, although NIMH-sponsored studies of twins and families suggest that genetics play a role in the development of some anxiety disorders, problems such as PTSD are triggered by trauma. Genetic studies may help explain why some people exposed to trauma develop PTSD and others do not.

Several parts of the brain are key actors in the production of fear and anxiety. Using brain imaging technology and neurochemical techniques, scientists have discovered that the amygdala and the hippocampus play significant roles in most anxiety disorders.

The amygdala is an almond-shaped structure deep in the brain that is believed to be a communications hub between the parts of the brain that process incoming sensory signals and the parts that interpret these signals. It can alert the rest of the brain that a threat is present and trigger a fear or anxiety response. It appears that emotional memories are stored in the central part of the amygdala and may play a role in anxiety disorders involving very distinct fears, such as fears of dogs, spiders, or flying.

The hippocampus is the part of the brain that encodes threatening events into memories. Studies have shown that the hippocampus appears to be smaller in some people who were victims of child abuse or who served in military combat.17, 18 Research will determine what causes this reduction in size and what role it plays in the flashbacks, deficits in explicit memory, and fragmented memories of the traumatic event that are common in PTSD.

By learning more about how the brain creates fear and anxiety, scientists may be able to devise better treatments for anxiety disorders. For example, if specific neurotransmitters are found to play an important role in fear, drugs may be developed that will block them and decrease fear responses; if enough is learned about how the brain generates new cells throughout the lifecycle, it may be possible to stimulate the growth of new neurons in the hippocampus in people with PTSD.

Current research at NIMH on anxiety disorders includes studies that address how well medication and behavioral therapies work in the treatment of OCD, and the safety and effectiveness of medications for children and adolescents who have a combination of anxiety disorders and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

When Memories Are Scars

Harrowing experiences damage the brain.

New drugs promise to heal it.

Could the end of posttraumatic stress be near?

By Matt Bean

Roger Pitman, M.D., hunts nightmares for a living. Not the vivid phantasmagoria populated by zombies or disembodied skulls, or even the nude-at-the-podium orations that leave us blushing in our sleep. He's after the nonfiction variety, the indelible, enduring flashbacks that stick in our heads after reality goes awry: a saw blade meeting flesh, say, or an improvised explosive device overturning a Humvee.

I'm in Dr. Pitman's lab in Boston, watching him track down a particularly vivid figment, a stab wound to the neck that's been plaguing 43-year-old carpenter Al Carney for 2 months now. "We're about to put him back in the most horrifying moment of his life," says the Harvard psychiatrist, peeling back the top sheet on a thick medical file labeled Patient 102. In the room next door, the stout laborer sits, eyes closed, headphones on, wired with a battery of biofeedback equipment: electrodes affixed to his chest to monitor his heart rate; a forehead sensor scanning for tension; and a tiny pad on the inside of his palm measuring how much sweat seeps through his skin.

"It's 8:30 a.m. on Thursday, March 30," a narrator begins to read over the headphones. "Noticing Peter Bowman standing there, you become tense all over. He says he's here to collect a check. Feeling jittery, you tell him he needs to fix several things before you pay him any more. As the argument becomes heated, your heart beats faster. Peter becomes physically aggressive, and you feel a blow to your neck. You fall to the ground. Several people pull him off you. . . . After you're separated, you realize that you're bleeding profusely from several knife wounds."

Fade Away

Carney's vital signs ebb and flow on a flat-screen monitor in the corner of the room as he reimagines the assault. They spike when he's "stabbed" by Bowman. But I don't need whirring telemetry machines to tell me the narrative has struck a nerve: Carney starts fidgeting, and he taps his scuffed gym shoes together at the toes. Even though he's been asked to sit still, his head twitches back and forth against the recliner's headrest. Later, Dr. Pitman will compare Carney's physiological responses with the results from previous sessions, as well as his reactions to positive scripts used as controls—the birth of his first child, a transcendent round of golf. Carney is one of dozens of accident victims that Dr. Pitman and his team have culled from Boston emergency rooms to study a drug called propranolol. The study is double-blind—no one, least of all Carney, knows whether the pill he took was a placebo or propranolol. But the contractor hopes he'll get lucky and will be able to stop the spiral of substance abuse, irritability, and insomnia that started with the stabbing at the construction site.

Dr. Pitman's study is leading a new wave of research that promises to curtail the harmful psychological effects of extreme stress, especially posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Today's most common treatment, cognitive-behavior therapy coupled with drugs such as Prozac, fails at least as often as it succeeds. Dr. Pitman hopes that defusing horrible memories—that high-school car crash, the abusing babysitter—could within 5 years become less difficult with the help of propranolol.

"Posttraumatic stress disorder is just a memory that has its volume set too loud," Dr. Pitman observes, thumbing through a thick sheaf of case histories. "Something turned up the switch. We're trying to turn it back down again."

Surviving Trauma

We all have things we'd like to forget. And some of us have things we can't bear to remember. According to the National Center for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, 61 percent of American men will be exposed to a traumatic event in their lifetimes. And, according to the National Comorbidity Survey, 5 percent of men nationwide will develop PTSD at some point in their lives. These men include 9/11 survivors, Hurricane Katrina victims, and, increasingly, military veterans: According to a 2005 study published in the New England Journal of Medicine, 17 percent of Iraq war veterans suffer from PTSD, anxiety, or depression. But the disorder also hits closer to home. Domestic disputes, burglaries, accidents, and even surgeries can engrave malignant memories on the brain. One recent study suggests that more than 15 percent of heart-attack

Not every man who falls victim to atraumatic event develops PTSD, of course. To be diagnosed, you must experience a laundry list of symptoms for more than a month. Some people, inexplicably, shrug off serious trauma without a second thought. Carney is somewhere in between the two extremes: While the past has become an inescapable drag on the present, it is a nagging presence, not an overriding one.

"We all have stress hormones, and we're all affected by them," says Deane Aikins, Ph.D., a Yale psychologist who heads up the cognitive neuroscience wing of the National Center for PTSD. "We're just now beginning to understand why some of us are inherently more resilient to the stress, and how maladaptive behaviors learned at an early age can impact us for the rest of our lives."

Just as cancer researchers have made countless discoveries about how normal cells live and die, so have PTSD researchers used their unique niche to shine a broader spotlight on the delicate interaction between the brain and the body. And what they've learned has implications far beyond PTSD. It could change how we think about stress altogether.

All in a Day's Work

"I should never have even been at the mill," says Terrell Kyle, a 43-year-old cabinetmaker from Caribou, Maine. "That's what really gets me." Kyle is the sort of solitary woodworker who'd rather fashion the occasional cabinet in his garage workshop than work behind the big-mill, big-money lumber machines that churn thousands of logs into millions of planks each day. But in the winter of 2005, his family short on cash, he went back to the mill, reluctant but resolute.

About 3 months in, and just 25 minutes before the end of a brutal graveyard shift, the conveyor belt of lumber under Kyle's watch jammed. He walked over to do the usual routine: Hit the kill switch, clear the board, restart the saw. And that's how it might have gone, in fact, if he'd been more familiar with the equipment, if it hadn't been his 10th machine of the day, or if he hadn't been working at high speed for 11 hours and 35 minutes among some very sharp, very dangerous, very finicky machinery. As it happened, he dislodged the board, his hand kicked back into 24 inches of whirring steel, and, in a flurry of blood and blade, Kyle lost all the fingers and the thumb on his left hand.

"I keep coming back to that moment," he says. "I know I was screaming. But here's the thing: I don't ever remember looking at my hand. That moment is just lost. My supervisor came over, and I told him I had lost all of my fingers, so I'm sure I knew. But I just walked out of the mill and had a cigarette."

The orthopedic surgeon at the nearest hospital decided Kyle's injuries were beyond his reach, so the carpenter was helicoptered, along with a plastic bag containing four of his fingers breaded in sawdust, to Massachusetts General Hospital. There, he met an on-call member of Dr. Pitman's team and was administered a pill—either propranolol or a placebo—and underwent reattachment surgery.

The Role of Adrenaline

Kyle's hand rejected the fingers soon after, and months later, he still can't erase the painful memories. "Sometimes I wonder if I would have been better off as an automobile-accident victim with amnesia," he says. "The memory just seemed to impregnate itself so that it's there, all the time, like static, on the fringes of my mind, finding a way to intrude on my other thoughts. Anything going around fast creates this clenching feeling inside my chest. A snowblower. An airplane propeller. Car wheels. I often think I'm having a heart attack. I mean, consciously I know I'm not in any danger. But subconsciously, it makes me want to run, to get away, to not look, to plug my ears." Kyle's psychological symptoms—blackouts, flashbacks, depression, anxiety, insomnia, irritability, and hypervigilance—aren't the only tolls paid by PTSD sufferers. In a 2006 study, researchers in Switzerland found that the syndrome significantly raises the levels of a key blood-clotting agent, promoting arteriosclerosis and, by extension, increasing the risk of heart disease. Traumatic stress has also been linked to immune system, gut, and muscle disorders, such as hemorrhaging and ulcers.

Posttraumatic stress amounts to a spectacular breakdown of what is normally a very helpful mechanism. Bundling an emotional component with a memory dovetails with Darwin's theory of natural selection, says Dr. Pitman. "If you, as a Paleolithic man, happen to be taking a new route to the watering hole one day and encounter a crocodile, you'd better remember that crocodile," he says. "If you don't, you'll be eliminated from the gene pool. Adrenaline not only helps you escape, but strengthens that emotional component to make sure you won't forget."

But extremely traumatic events can unleash a torrent of stress hormones, searing the memory into the brain. That's where propranolol enters the picture. It blunts the impact of stress hormones on the amygdala, the small, emotional control center in the middle of your brain. As a result, the brain is able to encode the traumatic memory as a factual event, a garden-variety horrible memory, rather than a world-changing, panic-inducing schism in consciousness. It's like removing the crescendo of violins from the climax of an action movie: You still know what's happening, but you're able to focus on just the facts.

Erasing Memories from the Hard Drive

Propranolol is part of a class of drugs called beta-blockers already being used to treat real-time anxiety disorders, such as performance anxiety in public speakers. Dr. Pitman's study hinges on administering the drug within 6 hours of a traumatic event. And other researchers have been stretching the window even further—uncovering new revelations about how memories are made and stored in the brain. "The old story was that once memories are stored, they're stored forever," says Karim Nader, Ph.D., a researcher at McGill University, in Montreal. Nader specializes in the relatively new field of memory "reconsolidation," the subsequent revision of a memory after it's already been transferred into long-term storage. "But what I found is that once you access a memory, you have to restore it. It's kind of like taking a file off the hard drive and putting it into RAM—you have to save it to the hard drive all over again, or parts of it can get lost." Nader and his researchers have found an ingenious way to induce just such a memory loss—even in patients more than 3 decades removed from a traumatic event. First, he administers propranolol, effectively hitting the emotional mute button. Then he uses the same sort of prerecorded narration that Dr. Pitman (a co-researcher on the project) does to bring the memory into RAM. Finally, he moves on to other memories, and the patient's brain naturally "reconsolidates" the traumatic one with much less drama. Nader is now expanding the study in an attempt to corroborate his results with a larger group of subjects.

"Nobody knows when they're going to be in a car accident, or be raped, or be kidnapped, so trying to give them a pill within 6 hours of the trauma is difficult," he says. "But we can control the memory now, bringing it back to the point of sensitivity no matter when it occurred. This could have implications for all kinds of problems: drug addiction, obsessive-compulsive disorder, or anything where you need to change the wiring in the brain."

As visceral as they may be, traumatic events—explosions, stabbings, car crashes—may be less to blame for PTSD than the brains of the sufferers themselves. That's the lesson from as-yet-unpublished research on the army's 10th Mountain Division, a light-infantry, rapid-deployment force that has been dispatched into active duty more frequently than any other army division over the past decade.

Stress Resistance

What's unique about these soldiers, beyond their combat training and high stress levels, is their uniformity: They're all healthy, they're all screened often to eliminate psychological maladies and substance abusers, and, most important, they're all willing to let Deane Aikins, the Yale psychologist, scan their brains, drain their blood, and shock them with a small probe, all in the name of science. Aikins, a soft-spoken researcher charged with helping the Department of Veterans Affairs plan its approach to treating the waves of soldiers returning from Iraq, designed an experiment to compare how the soldiers would react to two different stimuli: an innocuous pulse of light, and a pulse of light paired with a slight electrical shock. He found that soldiers who overreacted to the innocuous stimulus were more likely to develop PTSD in Iraq if exposed to a traumatic event (95 percent of active-duty members are) than the cool-hand Lukes in the crowd. What could the key physiological difference be? A chemical called neuropeptide Y.

"In another study, we found that stress-resilient guys were under the same amount of combat stress as the PTSD guys, and indeed some of them were from the same unit," says Aikins, who plans to publish his research this fall. "But there's an explosion, somebody dies, a Humvee flips, and then one guy gets PTSD and another guy from the same unit doesn't. Why? Lo and behold, we're finding that the men who are unflappable may also have lower levels of cortisol and higher levels of neuropeptide Y."

Neuropeptide Y is one of hundreds of compounds involved in the complicated braiding of stress signals and memory. It isn't easily administered or synthesized, and so Aikins's research is valuable largely for prescreening for PTSD susceptibility, rather than as a means of treatment. But it's proof positive that the way we react to any stress—even a slight shock and an annoying flash of light—dictates the way we're likely to react to the most extreme stressors.

Flight-or-Flight Response

Beneath all the bells and whistles, behind all the high-level cognition—calculus, poetry, Sudoku—the brain is just a fancy system for detecting and avoiding stress. Nobel Prize-winning researcher Eric Kandel demonstrated this more than 50 years ago by analyzing the nervous system of a simple sea snail, called aplysia. The snail's nervous system, Kandel found, would change at the synaptic level when it "learned," strengthening the connection between nerve cells that carry out a particular behavior (gill retraction) and sensory nerve cells that react to a stimulus (mechanical probe). It was a seminal discovery: Actual physical changes, both in how the neurons connect to one another and within the chemical gateways that govern the firing of each neuron itself, underlie learning and memory. The consequence of having a brain tuned to change with even minor stress, however, is that it's extra-sensitive to overload by extreme stress. Over the past decade, molecular biologists have begun to unravel how this happens at the cellular level.

"The brain is like a collection of mobile phone networks," says Hermona Soreq, Ph.D., a Jerusalem-based neurobiologist who has developed a drug to block PTSD at the DNA level. "They all communicate within themselves, but also within each other. We know that when there is a big disaster, like the recent missile attacks, the network crashes. That's posttraumatic stress for you. That's what we see in the shelters and streets every day."

Soreq's motivation for beating PTSD is anything but academic: I spoke with her the day before the UN-proposed cease-fire went into effect in the Israeli-Lebanese conflict, as she feared for the safety of her son, a soldier, and as both sides bombed and strafed to try to claim victory with the deadline looming.

Threats of any kind—especially life-threatening ones—trigger the release of the fight-or-flight neurotransmitter acetylcholine. Add more and the neurons fire faster and more efficiently, speeding up the network. Take it away—this is what chemical-warfare agents like Sarin or Zyklon B do—and you essentially shut down the network. To keep us on an even keel, the brain releases certain chemicals to help tone down this fight-or-flight response after the threat has passed. But if we keep seeing Dr. Pitman's crocodiles, even just in our heads, these compounds can permanently alter the structure of our brain, disrupting our neurochemical balance and leading to PTSD-like problems.

Playing God with the Brain

Soreq's drug, called Monarsen (after her nickname, Mona), stops the unbalancing by blocking production of one of these buffering compounds, a persistent, fast-moving version that appears only during stressful situations. Monarsen effectively handcuffs the compound's DNA blueprint, or gene, from being turned into a biologically active protein, cutting the problem off at the source. "What we do in present-day therapy, with drugs such as Prozac or propranolol, is the least economical approach," says Soreq. "We try to block the bottom of the gene-expression pyramid—the proteins, the stress hormones such as cortisol or adrenaline," she says. "But you have one gene at the top of the pyramid controlling everything, so why not aim there?"

Monarsen, then, is the equivalent of using a laser-guided missile to target an enemy's headquarters instead of razing the entire town. That precision enables it to be administered in smaller doses, with fewer side effects. And because acetylcholine impacts cellular signaling throughout the body, from the immune system to the red blood cells, it may prevent an even wider range of stress-caused symptoms.

"Our goal is to prevent changes in the brain that have the potential to ruin the life of a child who spends 4 weeks in a bomb shelter, or the victims of 9/11," she says. "Or the soldiers now fighting in Iraq."

"That's like playing god with the brain," says Barry Romo, a national coordinator with a Vietnam-veterans antiwar group. "One of the things that keeps us from remaking mistakes is looking back and having regret, as opposed to thinking, Well, shit, that was a close shave, but at least I'm okay."

Romo, one of a small but very vocal group of critics of Soreq's and Dr. Pitman's research, worries that the way we interpret memories, whether terrifyingly vivid or naive and nostalgic, is part of who we are as individuals. To tinker with that is to step onto unsteady ethical ground.

Avoiding Abuse

"I think people have a right to have medication, if they need it, but I have to wonder what these drugs will be used for in the hands of police or the military or someone who doesn't deserve them," he says. "We don't want to create a bunch of storm troopers who can do anything they want without having to worry about the repercussions." Dr. Pitman, for his part, says that's overstating what such drugs can do—at least for now. "I think it's far-fetched, but it's possible that something like that will be found. I don't think it's going to be with propranolol, but it's possible," he says. "But then you get into the question of 'Do we hold back a drug from people it can help simply to prevent others from abusing it?' If we practiced that, then nobody in the hospital would be able to get morphine for their pain. When you're talking about people who are dying of cancer, it's not really a tough decision."

Cabinetmaker Terrell Kyle won't know for another year whether he received the placebo or the active drug in Pitman's double-blind study. But simply learning about the biology of his disorder has helped Kyle deal with the flashbacks and panic attacks, rein in his rage around the house, and reconnect with his daughter, who, he says, bore the brunt of his mood swings. The prosthetic he's been given is too clumsy for detailed woodworking, but Kyle hopes that someday he might even be able to fire up some of the new tools that now sit in his garage gathering dust.

"Some people go through years and years of torture," he says. "Should we mess with their memories? Should we be able to take those thoughts away? Absolutely. We want to act as though nothing happened, but it's never that easy."

"It's not about playing God," Kyle goes on. "It's about finding a way to feel human again."

When Anxiety Is at the Table

By Jeff Bell : NY Times Article : February 6, 2008

For some of us the trouble starts before we even step into a restaurant.

If Carole Johnson, a retired school administrator who lives near Sacramento, Calif., happens to have a distressing thought while passing through a doorway, she needs to “clear” the thought by passing through the door twice more, doing it precisely three times.

My own challenge is fighting the urge to return to my parked car and check yet again that the parking brake is secure. If I don’t, how can I be sure my car won’t roll into something — or worse, someone?

Ms. Johnson and I are but two of the estimated five to seven million Americans battling obsessive-compulsive disorder, an anxiety disorder characterized by intrusive distressing thoughts and repetitive rituals aimed at dislodging those thoughts. We are an eclectic bunch spanning every imaginable cross-section of society, and we battle an equally eclectic mix of obsessions and compulsions. Some of us obsess about contamination, others about hurting people, and still others about symmetry. Almost all of us can find something to obsess about at a restaurant.

Sometimes the trouble is the element of public theater in the dining room, meaning we have to indulge in our often-embarrassing rituals under the eyes of so many strangers while trying not to get caught. Or it might be worrying about the safety of the food and the people who serve it.

Many of the situations that unsettle people with obsessive-compulsive disorder — driving, for instance — provoke at least some level of anxiety in just about everyone. But restaurants are designed to be calming and relaxing. That is one of the main reasons people like to eat out.

To many of us with obsessive-compulsive disorder, those pleasures are invisible. We walk into a calm and civilized dining room and see things we won’t be able to control. This feeds directly into one of the unifying themes of the disorder: an often crushing inability to handle the unknown.

“The common thread, I think, has something to do with certainty,” said Dr. Michael Jenike, medical director of the Obsessive Compulsive Disorders Institute at McLean Hospital in Belmont, Mass., which is affiliated with Harvard Medical School. “If you have O.C.D., whatever form, there seems to be some problem with being certain about things — whether they’re safe or whether they’ve been done right.”

If lack of certainty is our common challenge, than warding off uncertainty is our common quest. For some of us battling obsessive-compulsive disorder, that means scrubbing our hands to make sure they’re clean, or checking and re-checking everything around us in the name of safety. For others, the need is to arrange various items in order, or repeat actions in ritualized sequences in vain attempts at removing doubt.

These quirks lead to some serious complications in our lives, especially when we find ourselves in a place that triggers obsessive-compulsive behavior, like a restaurant. Once Ms. Johnson gets past the door, she often needs to try out a few tables, looking for one that feels right, as a frustrated maître d’hôtel looks on.

Personally, I am fine with just about any table, although the wobbly ones can spell big trouble. I have harm obsessions, which means I am plagued by the fear that other people will be hurt by something I do, or don’t do. Seated at a less-than-sturdy table, I conjure images of fellow diners being crushed or otherwise injured should I fail to notify the restaurant’s management. This is called a reporting compulsion in the vernacular of the disorder, and before I learned to fight these urges, many a manager heard from me.

One of them was the woman running a coffee house I frequent. One day while sipping my latte at a fake-marble table I leaned forward, and the far end of the tabletop lifted. This barely moved my coffee cup, but it sent my nerves right through the roof. Before I realized it I was crouched over, my head upside down beneath the table. The only responsible thing to do, I decided, was to ask the woman behind the counter to come over for a look. Her lack of concern only exacerbated my problems.

Forget the tabletop, my friend Matt Solomon tells me; it’s what’s on top of the table, and precisely where, that really matters. Mr. Solomon is a 39-year-old lawyer in Fort Worth with order compulsions. To enjoy a meal he needs to separate the salt and pepper shakers, and, ideally, place a napkin holder or other divider midway between them.

Why? He can no more answer that than Ms. Johnson can tell you why she needs to chew her food in sets of three bites or drink her beverages three sips at a time. Three is her magic number. That is about as refined an explanation as any of us can give for our compulsions, rituals that we understand are entirely illogical.

Some of our other concerns may seem familiar. I imagine most diners, for example, have noticed and perhaps even struggled to remove white detergent spots that can sometimes be seen on silverware. But few, I suspect, have gone to the lengths Jared Kant has to get rid of them. Mr. Kant is a 24-year-old research assistant living outside of Boston who has obsessive fears of contamination. (He first came to my attention when I read a memoir he wrote about living with obsessive-compulsive disorder.) Last year he visited a Chinese restaurant with several friends, one of whom pointed out that their silverware was spotted and seemed dirty. Mr. Kant collected all the utensils at the table and attempted to sterilize them by holding them above a small flame at the center of a pu-pu platter, quickly attracting the attention of their waiter.

Ah, waiters, and waitresses. And bartenders. For some with obsessive-compulsive disorder, the success or failure of a dining experience can hinge on the appearance of a restaurant’s staff.

Mr. Solomon, for example, feels compelled to inspect the hands of anyone serving him. Cuts and scrapes are objectionable because in his mind, they can lead to his contracting a disease that could kill him.

This past Halloween, Mr. Solomon ate at the bar of a steakhouse, where he was served by a bartender dressed in a devil costume. He noticed a small red stain on the man’s right knuckle, and couldn’t rule out the possibility that the stain was blood. Trying to avoid things the bartender had touched, Mr. Solomon used a straw to drink from his water glass and swapped the silverware the bartender had placed in front of him for another set from farther down the bar.

Coincidentally, Mr. Solomon and Mr. Kant have each battled contamination issues on both sides of the counter. Mr. Solomon spent years working as a bartender, often consumed by thoughts of becoming deathly ill. He was convinced that one of his regular customers was carrying a fatal virus, and came up with strategies to minimize contact. “I would always quickly put his change down before he could try to take it from my hand,” he said.

The challenge for Mr. Kant was serving lattes. In his late teens, while training to be a barista, he learned of the potential dangers from improperly handled milk. He became obsessed with the possibility of harming customers through inadvertent negligence. Even worse was the prospect that he might never know. “My biggest fear was that one day I would find out that a customer had come down sick, brutally sick with something, and the only thing they knew was that they’d had a latte,” Mr. Kant said.

I can’t imagine handling even the most basic server duties, like adding up the items on a customer’s bill. I struggle enough with checking and rechecking my tip calculations. And that’s just one of my challenges at the end of a meal.

As part of my harm obsession, one of my concerns is that germs from my mouth will hurt others. Although I try to keep my fingers away from my lips and their germs while I’m eating, I’m rarely successful (it’s not as easy as it sounds). By the end of the meal I believe that my hands are contaminated. The problem is that I need them to scribble my signature on the check. If I’m lucky, I will have remembered to bring my own pen; if not, I may feel compelled to “table-wash” my hands, a little trick I developed over the years: I use the condensation on the outside of a cold water glass to rinse off the germs. (Forget drying my hands, by the way; my napkin would only re-contaminate them.)

Once the check is signed, I must be sure that it is really signed. At my worst, I have opened and closed the vinyl check holder again and again, seeing my signature each time, yet unable to feel certain. I’ve left the table, only to return to check again. And again.

Help is available, in the form of a therapy called exposure response prevention. As the name suggests, the technique calls for exposing people with obsessive-compulsive disorder to situations that trigger obsessions, then preventing them from acting on them. The therapy addresses low-level anxieties, and works up from there.

With restaurant cleanliness, for example, a therapist might have an client rate his anxiety about challenges ranging from simply touching spotted silverware to eating from a spotted plate. Then the therapist would ask him to face those situations while fighting the compulsion to clean or replace spotted items.

The therapy attempts to alter behavior, but it appears to alter much more than that. Dr. Sanjaya Saxena, the director of a program for obsessive-compulsive disorders at the University of California at San Diego, said that exposure response prevention therapy “certainly is changing the brain at the molecular level — that is, at the level of particular proteins that are expressed and created and on the level of neurotransmitter function.” In that sense, he said, “behavioral therapy is biological therapy.”

I am no brain scientist. I understand almost nothing about proteins and neurotransmitters. But my own extensive work with this particular form of torture (that is, directed treatment), with medication, has progressively allowed me to take back much of the life my disorder stole from me.

Today I travel extensively, sharing my recovery story and working with groups like the Obsessive Compulsive Foundation to raise awareness. In my job as a radio news anchor, I don’t have to eat out much, but when I’m on the road for work related to the disorder, I wind up eating in a lot of restaurants. I can honestly say I’m starting to enjoy it. In fact, while I still like ice water with my meal, I often find myself drinking from the glass, not washing with it.

Now when I say check, please, I’m simply asking for my bill.

Extinguishing the Fear at the Roots of Anxiety

By Benedict Carey : NY Times Article : July 9, 2008

The study of anxiety is fast merging with the science of memory. No longer focused just on symptoms like social isolation and depressed mood, scientists are turning to the disorder’s neural roots, to how the brain records and consolidates in memory the frightening events that set off long-term anxiety. And they are finding that it may be possible to blunt the emotional impact of even the worst memories and fears.

The war in Iraq has lent a new cultural urgency to this research. About one in eight of the troops returning from combat show signs of post-traumatic stress disorder, or P.T.S.D., which is characterized by intrusive thoughts, sleep loss and hyper-alertness following a horrifying experience. Many are so traumatized that they fail utterly to respond to antianxiety medications, talk therapy and other conventional treatments.

P.T.S.D. is one of the most worrisome of the generally recognized anxiety disorders. There are four others: generalized anxiety disorder (G.A.D.), obsessive-compulsive disorder, phobias and panic disorder. G.A.D. is the most common, but all are familiar complaints in doctors’ offices: more than 20 million Americans will suffer one of these during his or her lifetime.

Genetics and the environment play roles in the development of anxiety disorders, but the point where these influences intersect is clearly the brain. The biology of anxiety has been very difficult to untangle in part because it is so familiar, so integral to our survival.

Most people can and do cope with many causes of anxiety, including demanding jobs, rocky relationships, second mortgages and even combat. Every day uncounted millions are beset by the sudden, heart-pounding dizziness of panic. It is normal, even necessary, to feel fear and stress. The brain’s anticipation of threats is an invaluable survival tool. The question for scientists is: Why can’t some people turn down the voltage?

When mammals sense threat, at least two important brain circuits swing into action. One pathway runs through the frontal lobe of the cerebral cortex, the layer of the brain that regulates consciousness, thinking and decision-making functions.

The other circuit is more primal, running deep into the unconscious brain and through the amygdala, a pair of lozenge-sized nubs of neural tissue (one on each side of the brain) specialized to register threats. This unconscious circuit is “quick and dirty,” a primal survival instinct that increases blood pressure, heart rate

The difference between the two may be crucial to understanding how an irrational fear forms. The amygdala records sights and sounds associated with a harrowing memory, and it is capable of sending the body into high alert before a person consciously processes the stimuli.

Most drugs currently prescribed for anxiety, like benzodiazepines and antidepressants, work to ease the symptoms of anxiety and have little effect on the underlying trigger. But scientists are now taking tentative first steps toward altering the brain’s age-old dynamic.

Researchers have been experimenting with a heart disease drug called propranolol, for instance, which interferes with the action of stress hormones like epinephrine. Stress hormones are central to the human response to threat; they prime the body to fight or run, and appear to deepen the neural roots of a terrifying memory in the brain. When the memory returns, these hormones flood again into the bloodstream.

But in one series of studies, people with P.T.S.D. who took propranolol reacted more calmly — on measures of heart rate and sweat gland activity — upon revisiting a painful memory than did similar subjects who took a dummy pill. By blocking receptors on brain cells that are sensitive to stress hormones, experts theorize, the drug may have taken the sting out of the frightening recollections.

Propranolol has not been proved to reliably ease the effects of trauma, but the investigation of such drugs is only beginning. Another candidate, an antibiotic called D-cycloserine, may help severely anxious patients alter the way they think about and react to current everyday concerns.

In one experiment, 28 people who were terrified of heights received so-called exposure therapy, including computer simulated rides in a glass elevator. The therapy helped all the subjects cope with their anxieties. But the participants who also took D-cycloserine learned to override their fears far more quickly than those who did not.

The drug may speed up a process that researchers call fear extinction, the unlearning of frightening associations. In theory, a successful fear-extinguisher might even complement analytic talk therapy in which patient and therapist work to understand how symptoms might be linked to loss, poisoned relationships or childhood traumas. The anxieties that flow from these events flourish deep in the brain, but now there is evidence that they can be rooted out — a chance for balm in an increasingly harrowing world.

and alertness well before the thinking cortex is fully aware of what is happening.

Anxiety Disorders affect about 40 million American adults age 18 years and older (about 18%) in a given year, causing them to be filled with fearfulness and uncertainty. Unlike the relatively mild, brief anxiety caused by a stressful event (such as speaking in public or a first date), anxiety disorders last at least 6 months and can get worse if they are not treated. Anxiety disorders commonly occur along with other mental or physical illnesses, including alcohol or substance abuse, which may mask anxiety symptoms or make them worse. In some cases, these other illnesses need to be treated before a person will respond to treatment for the anxiety disorder.

Effective therapies for anxiety disorders are available, and research is uncovering new treatments that can help most people with anxiety disorders lead productive, fulfilling lives. If you think you have an anxiety disorder, you should seek information and treatment right away.

Each anxiety disorder has different symptoms, but all the symptoms cluster around excessive, irrational fear and dread.

Panic Disorder

"For me, a panic attack is almost a violent experience. I feel disconnected from reality. I feel like I'm losing control in a very extreme way. My heart pounds really hard, I feel like I can't get my breath, and there's an overwhelming feeling that things are crashing in on me."

"It started 10 years ago, when I had just graduated from college and started a new job. I was sitting in a business seminar in a hotel and this thing came out of the blue. I felt like I was dying."

"In between attacks there is this dread and anxiety that it's going to happen again. I'm afraid to go back to places where I've had an attack. Unless I get help, there soon won't be anyplace where I can go and feel safe from panic."