- RETIREMENT ANNOUNCEMENT

- HOME PAGE

- "MYCHART" the new patient portal

- BELMONT MEDICAL ASSOCIATES

- MOUNT AUBURN HOSPITAL

- EMERGENCIES

- PRACTICE PHILOSOPHY

- MY RESUME

- TELEMEDICINE CONSULTATION

- CONTACT ME

- LAB RESULTS

- ePRESCRIPTIONS

- eREFERRALS

- RECORD RELEASE

- MEDICAL SCRIBE

- PHYSICIAN ASSISTANT (PA)

- Medicare Annual Wellness Visit

- Case management/Social work

- Quality Care Measures

- Emergency closing notice

- FEEDBACK

- Talking to your doctor

- Choosing..... and losing a doctor

- INDEX A - Z

- ALLERGIC REACTIONS

- Alternative Medicine

- Alzheimer's Disease

- Bladder Problems

- Blood disorders

- Cancer Concerns

- GENETIC TESTING FOR HEREDITARY CANCER

- Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

- Controversial Concerns

- CPR : Learn and save a life

- CRP : Inflammatory marker

- Diabetes Management

- Dizziness, Vertigo,Tinnitus and Hearing Loss

- EXERCISE

- FEMALE HEALTH

-

GASTROINTESTINAL topics

- Appendicitis

- BRAT diet

- Celiac Disease or Sprue

- Crohn's Disease

- Gastroenterologists for Colon Cancer Screening

- Colonoscopy PREP

- Constipation

- Gluten sensitivity, but not celiac disease

- Heartburn and GERD

- Hemorrhoids and Anal fissure

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- NASH : Non Alcoholic Steato Hepatitis

- FEET PROBLEMS

- HEART RELATED topics

-

INFECTIOUS DISEASES

- Antibiotic Resistance

- Cat bites >

- Clostridia difficile infection - the "antibiotic associated germ"

- CORONA VIRUS

- Dengue Fever and Chikungunya Fever

- Food borne illnesses

- Shingles Vaccine

- Hepatitis B

- Hepatitis C

- Herpes

- Influenza

- Helicobacter pylori - the "ulcer germ"

- HIV Screening

- Lyme and other tick borne diseases

- Measles

- Meningitis

- MRSA (Staph infection)

- Norovirus

- Sexually Transmitted Diseases

- Shingles (Herpes Zoster)

- Sinusitis

- West Nile Virus

- Whooping Cough (Pertussis)

- Zika virus and pregnancy

- INSURANCE related topics

- KIDNEY STONES

- LEG CRAMPS

- LIBRARY for patients

- LIFE DECISIONS

- MALE HEALTH

- Medication/Drug side effects

- MEDICAL MARIJUANA

- MENTAL HEALTH

- Miscellaneous Articles

-

NUTRITION - EXERCISE - WEIGHT

- Cholesterol : New guidelines for treatment

- Advice to lower your cholesterol

- Cholesterol : Control

- Cholesterol : Raising your HDL Level

- Exercise

- Food : Making Smart Choices

- Food : Making Poor Choices

- Food : Grape Fruit and Drug Interaction

- Food : Vitamins, Minerals and Supplements

- Omega 3 fatty acids

- Vitamin B12 deficiency

- Vitamin D

- Weight Loss

- ORTHOPEDICS

- PAIN

- PATIENTS' RIGHTS

- SKIN

- SLEEP

- SMOKING

- STROKE

- THYROID

- SUBSTANCE ABUSE

- Travel and Vaccination

- TREMOR

- Warfarin Anticoagulation

- OTHER STUFF FOLLOWS

- Fact or Opinion?

- Hippocratic Oath

- FREE ADVICE.......for what its worth!

- LAUGHTER.....is the best medicine

- Physicians Pet Peeves

- PHOTO ALBUM - its not all work!

- Cape Town, South Africa

- Tribute page

- The 100 Club

- Free Wi-Fi

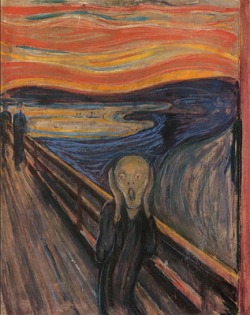

Stress

People react to stress in many ways. There may be physical, behavioral and emotional manifestations.

Physical manifestations:

Unexpected Symptoms of Burnout:

The Tension Builds (It’s Almost Monday)

By Kelley Holland

NY Times Article : March 23, 2008

The feeling is familiar: you are savoring the last of a leisurely Sunday lunch or a long walk in the park when you abruptly realize that your weekend will be over in a matter of hours. In an instant, you are deep in what John Updike called the “chronic sadness of late Sunday afternoon.” As you envision the to-do pile on your desk, the meetings on your calendar, and that trip to Topeka on Tuesday, your mood shifts again, your muscles tense and your head begins to ache.

You have a case of workplace-related stress. You also have plenty of company.

Poll results released last October by the American Psychological Association found that one-third of Americans are living with extreme stress, and that the most commonly cited source of stress — mentioned by 74 percent of respondents — was work. That was up from 59 percent the previous year.

Some people would not be alarmed by this. When David W. Ballard, the association’s assistant executive director for corporate relations and business strategy, talks to executives, “the concept that stress can be a bad thing is sometimes foreign to them,” he said. “They say stress is a good thing. It motivates them.”

But excessive stress is different, and extremely expensive for employers. Highly stressed employees are absent more often and are much more likely to leave their jobs. When at work, they tend to be significantly less productive — a phenomenon known as presenteeism, which can be even more expensive than frequent absences, Dr. Ballard said.

More than half the respondents to the survey said they had left a job or considered doing so because of stress, and 55 percent said that stress made them less productive at work.

With costs like that, you’d think that companies would devote considerable resources to fighting the problem. But a survey published last year by Watson Wyatt suggests that they aren’t. For example, some 48 percent of the employers in the survey said stress created by long hours and limited resources was affecting business performance, but only 5 percent said they were taking strong action to address those areas.

“Everybody knows it’s an issue, but no one wants to look at it and address it,” said Shelly Wolff, Watson Wyatt’s North American leader for health and productivity. Employers view excessive workplace stress as an enormously costly problem that no one quite knows how to fix, she said. “There’s a fear of opening up something you can’t control,” she said. “They feel it’s going to open Pandora’s box.”

One problem is that stress can be subjective. Some people may feel permanently tethered to the office by their cellphones and laptops, but for others those devices are liberating. One person’s dreaded business trip is another’s respite from pressures at home.

That means there is no one-size-fits-all way for employers to reduce office stress. But putting in place a variety of initiatives is still simpler and less expensive than dealing with extreme stress once it arrives.

At GlaxoSmithKline, a program called “Team Resilience” combines things like health assessments, discussion groups and follow-up evaluations to deal with workplace stress.

The company’s promotion management group, which develops promotional materials and obtains regulatory approval for them, went through the process last fall. The roughly 100 employees in the group, spread between Philadelphia and Research Triangle Park in North Carolina, completed questionnaires about workplace stress and then met in groups organized by work specialty — editors with editors, designers with designers, and so on — to discuss results.

At the outset, “they thought, ‘Oh no, not another survey, not another class,’” said Karen W. Ruffner, the group director. “But when we set up workshops by functional areas, I think they were pleasantly surprised. It gave them an opportunity to talk among their peers. Sometimes you almost have to force that time for people who are really busy.” The groups are having follow-up meetings to address the issues that surfaced, like a desire for more flexibility in how work is organized, she said.

PricewaterhouseCoopers also addresses stress in multiple ways. For example, in annual surveys, employees asked for more coaching and opportunities to connect with more experienced colleagues — and got them.

Over the past two years, the firm has also created market teams for various business lines, which means that 80 to 100 people work together on a portfolio of client accounts. Employees can cover for one another more easily, easing some of the pressure.

Michael J. Fenlon, managing director for people strategy at PricewaterhouseCoopers, said the surveys found higher satisfaction levels and lower turnover among those in market teams. The goal, he said, was “to create an environment where there’s openness and a sense of mutual support,” he said, “where I can work through life-cycle events and no one’s going to think less of me.”

Until recently, if employees sent e-mails on weekends or after hours, an automatic message would appear asking the sender to wait, if possible, and let others enjoy their down time. The message was discontinued after the company determined that workers had taken this stress-reducing sentiment to heart.

When a Co-Worker Is Stressed Out

By Elizabeth Bernstein

WSJ Article : August 26, 2008

Feeling particularly stressed at work? Look around you.

Even in good times, it's not always easy to keep your cool on the job. But as the economy falters and layoffs sweep certain industries, many people are more worried than ever about job security -- in addition to fretting over the value of their homes, the cost of college and a host of other issues. Making matters worse: Stressed-out bosses and co-workers tend to pass tension on to others.

Most people can handle the strain. But what do you do when you think that the person sitting next to you at work cannot?

If you see a co-worker suffering, it's understandable that you may want to offer help. And if you're the boss, in addition to alleviating distress, you will also need to worry about a worker's productivity, as well as office morale.

Indeed, employers may be held liable for failing to prevent the worst-case scenario -- office violence. Warning signs include direct threats, menacing gestures or statements such as, "You wouldn't miss me if I were gone."

"If you are afraid of someone, there is probably a good reason," says Marina London, Web editor for the Employee Assistance Professionals Association, a membership organization based in Arlington, Va., and a licensed social worker. Experts say that someone who appears to be a threat should be dealt with by managers immediately and carefully, with the help of security.

Subtle Signs

But the vast majority of people suffering from mental stress in the workplace don't become violent, and the warning signs that something is wrong may be more subtle. In fact, by the time you notice that a co-worker has a problem, it's likely been going on for a while. That's why experts suggest intervening early.

Mental-health experts say they're seeing increasing signs of stress this year, with more people seeking professional help for mental strain brought on by financial or work issues. Since the Bear Stearns collapse last spring, calls to employee-assistance programs -- which help people with mental-health and personal problems -- have risen about 10%, according to the Employee Assistance Professionals Association.

"Work conditions can cause mental illness," says Rodney L. Lowman, a psychologist who specializes in occupational mental health and president of Lake Superior State University in Sault Ste. Marie, Mich. "If we put healthy, well-adjusted people in the right foxhole with guns blaring at them, the likelihood of them experiencing depression and anxiety is very high."

Experts say the most significant warning signs are changes in behavior, including work patterns, eating habits or drinking. Someone may start working too hard. He may show up late, appear despondent, withdrawn or abrasive, and seem increasingly annoyed. "Just being different is not the problem. It's the change," says James Campbell Quick, a professor at the University of Texas at Arlington who teaches preventive stress management.

Earlier this summer, Talia Witkowski was struggling through a meeting at the Los Angeles nonprofit organization where she worked when her boss pulled her aside. Dr. Witkowski, a psychologist, says the boss told her she didn't seem as sharp as usual and recommended that she take the rest of the day off to clear her mind. Dr. Witkowski went home, took a walk, wrote in her journal, and prepared a nice dinner for herself. "I was very thankful for her insight and intuition and for having been given the rest of the afternoon off to get back to center," says Dr. Witkowski.

When trying to help someone who is suffering from mental distress, it is critical to approach with empathy. "Let the individual know that you have a sense of understanding where they are coming from," says John Weaver, a psychologist in Waukesha, Wis., who consults with businesses.

It's perfectly fine, and can be helpful, to ask a co-worker how he's doing. But it's important not to be intrusive. "Say, 'I am sure you are experiencing a lot of stress at work; how are you coping?' " says Dr. Lowman. "It's about inviting conversation, not demanding answers."

No Labels

And never suggest that someone has a mental illness. "You always want to describe behavior, rather than label the person," says Ms. London, of the Employee Assistance Professionals Association. "So you don't want to say, 'I think you are anorexic.' You want to say, 'I am very concerned; I think you are losing a great deal of weight.' And you don't want to say, 'I think you are an alcoholic.' You want to say, 'I am worried that every night after work you have six beers.' "

If the colleague you are trying to help appears receptive, you may want to recommend they speak to a mental-health professional at your company's employee-assistance program. Many employers contract with outside firms to offer these services. "The job is encouraging them to go to an appropriate source for help and to get them to do that early rather than later," says Dr. Lowman.

Getting Attached

You should never offer help outside of work, especially if you are the boss. "It always ends badly," says Michael P. Maslanka, a labor and employment law attorney in Dallas. People under duress will sometimes attach themselves to the person who tries to help them and think that the solution to their problems is to talk to this person. They may start requesting increasing amounts of help.

"If it's serious, you need to point out that, 'I am not an expert,' " says Lester Tobias, a psychologist in Westborough, Mass., who specializes in management issues. He suggests saying, " 'I think this is over my head and you really need to talk to a professional if you want to talk.' "

If you are the boss, offering help outside of the office -- calling the doctor to make an appointment, for instance, or offering a ride -- may open you up to liability. Once you undertake the duty to help, the duty continues. If you don't continue with this responsibility in the future, you could be sued for negligence.

Time Off

So if you are the boss, you should offer only work-related help. Hand out the number to your employee-assistance program. Try to lighten someone's workload. Encourage the person to take vacation. Offer additional time off without pay.

And if the worker you're trying to help resists your overture -- and there doesn't seem to be a risk he will hurt someone, including himself, or his productivity isn't suffering -- back off, at least for now.

"You've communicated that you care about them," says Dr. Lowman. And that, he says, "may be helpful in itself."

Stress So Bad It Hurts -- Really

Melinda Beck : WSJ Article : March 20, 2009

"I think your real problem is stress," the doctor said when I complained that the muscle injections he was giving me hadn't relieved my neck and shoulder pain. "You can't blame me for everything that's hard in your life," he said.

My bursting into tears only seemed to confirm his diagnosis.

It's not like I hadn't heard this before. During earlier bouts of low-back pain, irritable-bowel syndrome and temporomandibular joint disorder, plenty of doctors have used the stress word with me. And each time, I've become indignant. It sounded like "it's all in your head" or "you're malingering."

That's an outdated view, says Christopher L. Edwards, director of the Behavioral Chronic Pain Management program at Duke University Medical Center. Decades ago, when doctors said a condition was psychosomatic, it was the equivalent of saying it wasn't real, since there was little evidence that the body and the brain were connected. "Now, we recognize that what happens in the brain affects the body and what happens in the body affects the brain," he says. That knowledge gives us the tools to try to manage the situation, he adds.

Dr. Edwards says his pain-management program in Durham, N.C., is seeing a rise in patients amid the current economic crisis: "There's a very strong relationship between the economy and the number of out-of-control stress cases we see."

From Stress to Pain

Psychological stress can turn into physical pain and illness in a number of ways. One is the body's primitive "fight-or-flight" mechanism. When the brain senses a threat, it activates the sympathetic nervous system and signals the adrenal glands to pump out adrenaline, cortisol and other hormones that prime the body for action. Together, they make the muscles tense up, the digestive tract slow down, blood vessels constrict and the heart beat faster.

That's all very useful for outrunning a mastodon. But when the threat is a tanking stock portfolio or an impending layoff, the state of alarm can last indefinitely. Muscles stay tense and contracted, which can make for migraine headaches, clenched jaws, knots in the neck and shoulders, and pangs in the lower back. Some of those body parts are already under pressure from long hours at the computer, restless sleep, grinding teeth and poor posture.

The Gut Brain

The digestive tract has its own extensive system of nerve cells lining the esophagus, stomach and intestines -- known as the gut brain -- that are extremely sensitive to thoughts and emotions. That's what creates the feeling of butterflies in the stomach. When anxiety persists, it can set off heartburn, indigestion and irritable-bowel syndrome, in which the normal movement of the colon gets out of rhythm, traps painful gas and alternates between diarrhea and constipation.

"Stress does not necessarily cause pain, but it exacerbates the [physical] situation that may already be there. It diminishes your ability to cope," Dr. Edwards says.

Stress also creates biochemical changes that can affect the immune system, making it underreact to viruses and bacterial infections, or overreact, which can set off allergies, asthma and skin disorders like psoriasis and eczema. And stress can raise the level of inflammation in the body, which has been associated with heart disease. A recent study in the journal Psychosomatic Medicine found that stressful conditions even in the teenage years can raise the level of C-reactive protein, a marker for inflammation that increases the likelihood of cardiovascular problems later.

There are plenty of ways to short-circuit these harmful effects of stress. One of the best is physical exercise, which not only releases the feel-good neurotransmitters called endorphins, but also helps use up excess cortisol and adrenaline. Under stress, "there's a large amount of negative emotional energy in your system that is trying to find a way to discharge," says David Whitehouse, a psychiatrist and chief medical officer for OptumHealth Behavioral Solutions, a unit of UnitedHealth Group Inc. He adds that "stress kills brain cells. The body responds by making new ones, and exercise can help activate them and make new connections between them."

Sleeping and Eating

Many experts also recommend getting plenty of sleep, eating regular, balanced meals and keeping up social connections -- all things that people tend to forgo in times of stress.

Biofeedback, once considered alternative medicine, is now accepted in mainstream medical circles as a way for people to reduce the impact of stress. Dr. Edwards runs a biofeedback laboratory at Duke, where patients monitor their heart rates, respiration, temperature and other vital signs and learn to control them with relaxation techniques. "The goal is that once we teach you to do that, you can use it the rest of your life," he says.

Another form of biofeedback is called Heart Rate Variability Training, which teaches people to adjust their breathing to maintain an optimum interval between heart beats that induces a feeling of calm throughout the body. "It's probably similar to what happens in yoga and meditation," says Dr. Whitehouse.

He adds that there is much new research going on in the field of "emotional resilience training" to help people learn to lower their anxiety levels and recover from setbacks. "People spend huge amounts of money, time and energy training their cognitive brains. What we now know is that the emotional brain can be trained as well to become more resilient," Dr. Whitehouse says.

Emotions play a major role in how pain is perceived in the brain. In the 1960s, Ronald Melzack, a Canadian psychologist, and Patrick David Wall, a British physician, offered a groundbreaking theory after observing soldiers in World War II. "Two soldiers with nearly identical injuries from the same bomb blast would be sitting side by side in a hospital ward," Dr. Edwards explains. "One soldier would be saying, 'Hey doc, can you sew me up? I need to get back to my unit.' And the other would be crying, moaning and writhing in pain."

Drs. Melzack and Wall determined that chemical gates in the spinal cord control pain signals from the body to the brain, depending largely on patients' emotional states. Positive emotions diminished the perception of pain, while negative emotions kept the gates open -- sometimes continuing the pain even after the initial cause had disappeared.

Fear versus Fact

There's a growing consensus that cognitive behavioral therapy can be very effective at diffusing negative emotions. It works by examining, and challenging, the thoughts behind them. "We'd say, 'I understand your fear, but fear is not a fact. Let's look at the reality in your life,'" says Katherine Muller, a cognitive therapist and director of psychology training at Montefiore Medical Center in Bronx, N.Y.

It's no surprise that being told that pain is stress related feels like an affront, Dr. Muller says. "There's this idea among high-functioning people that 'I'm a good coper,' and these symptoms suggest that you're not," she says. Indeed, many successful people find that low levels of stress and worry help them function. "But in periods of high stress, that worry takes over and becomes the dominant feeling. You're still going to work. You're still doing stuff for your family, but it's taking a toll. And suddenly your body is saying, 'Whoa -- I can't take the tension any more,'" Dr. Muller says.

One technique she uses is to have patients keep a diary evaluating their stress level on a scale of zero to 10 several times a day and note what was happening at the time. Patterns may emerge -- that headache may set in every Thursday afternoon, after the staff meeting -- and there may be ways to change the situation. "The message I'm trying to send is that you are responsible for your own stress," says Dr. Muller. "The way you are looking at it and feeling about it is more up to you than you realize."

So is stress-related pain all in your head after all? "All pain, and all human experience, is in your head," says Dr. Edwards. But that's a message of hope, he adds, since there are now ways that weren't available 60 years ago to ease pain by managing thoughts and emotions.

All right. Sew me up, doc. I want to get back to my unit -- I think.

So now you know how to recognize how stress may manifest, there is a lot you can do to decrease the stresses in your life. The next link has stress relief suggestions.

Physical manifestations:

- Dry mouth

- Fatigue

- Headache

- Muscle tension

- Rapid heartbeat

- Shakiness

- Shallow breathing

- Stomach upset

- Sweat or moist skin

- Teeth clenching or grinding

- Clamming up/not communicating

- Compulsive eating/gambling/sex/TV-watching

- Excessive drinking, smoking or drug abuse

- Facial or other tics, such as leg bouncing, pen tapping or finger drumming

- Isolating/withdrawing from family, friends, and community

- Lashing out at others/blowing up

- Sleep disturbances (unable to fall asleep, tossing and turning, waking up too early etc)

- Angrier than usual

- Crying more easily than usual

- Edginess

- Excessive guilt

- Feeling blue

- Feeling empty or spent

- Feeling helpless

- Feeling out of control

- Tired, disillusioned or emotionally fatigued?

- Under undue pressure to perform or be successful?

- Underappreciated or misunderstood?

- That you have more work than it is feasible to perform?

- That you do not have enough time to provide high quality care or service?

- That you are achieving less than you should be able to?

- Negative about your job or yourself?

- Frustrated or easily irritated by small or unimportant things?

- That you are unable to be empathic/sympathetic to people, colleagues or family members?

- That there is no one you can talk to?

- 0 - 1 questions there is no sign of burn-out.

- 2 - 4 questions then this represents early warning signs of a potential problem

- 5+ positive responses suggest that you are burned out and need to take action. Work toward relieving your stressors NOW!

Unexpected Symptoms of Burnout:

- Cynicism

- Boredom

- Feeling stuck in a rut

- Addiction

- Physical symptoms

- Anxiety/depression

- Jealousy

- Low self-esteem

- Defensiveness

- Impatience

The Tension Builds (It’s Almost Monday)

By Kelley Holland

NY Times Article : March 23, 2008

The feeling is familiar: you are savoring the last of a leisurely Sunday lunch or a long walk in the park when you abruptly realize that your weekend will be over in a matter of hours. In an instant, you are deep in what John Updike called the “chronic sadness of late Sunday afternoon.” As you envision the to-do pile on your desk, the meetings on your calendar, and that trip to Topeka on Tuesday, your mood shifts again, your muscles tense and your head begins to ache.

You have a case of workplace-related stress. You also have plenty of company.

Poll results released last October by the American Psychological Association found that one-third of Americans are living with extreme stress, and that the most commonly cited source of stress — mentioned by 74 percent of respondents — was work. That was up from 59 percent the previous year.

Some people would not be alarmed by this. When David W. Ballard, the association’s assistant executive director for corporate relations and business strategy, talks to executives, “the concept that stress can be a bad thing is sometimes foreign to them,” he said. “They say stress is a good thing. It motivates them.”

But excessive stress is different, and extremely expensive for employers. Highly stressed employees are absent more often and are much more likely to leave their jobs. When at work, they tend to be significantly less productive — a phenomenon known as presenteeism, which can be even more expensive than frequent absences, Dr. Ballard said.

More than half the respondents to the survey said they had left a job or considered doing so because of stress, and 55 percent said that stress made them less productive at work.

With costs like that, you’d think that companies would devote considerable resources to fighting the problem. But a survey published last year by Watson Wyatt suggests that they aren’t. For example, some 48 percent of the employers in the survey said stress created by long hours and limited resources was affecting business performance, but only 5 percent said they were taking strong action to address those areas.

“Everybody knows it’s an issue, but no one wants to look at it and address it,” said Shelly Wolff, Watson Wyatt’s North American leader for health and productivity. Employers view excessive workplace stress as an enormously costly problem that no one quite knows how to fix, she said. “There’s a fear of opening up something you can’t control,” she said. “They feel it’s going to open Pandora’s box.”

One problem is that stress can be subjective. Some people may feel permanently tethered to the office by their cellphones and laptops, but for others those devices are liberating. One person’s dreaded business trip is another’s respite from pressures at home.

That means there is no one-size-fits-all way for employers to reduce office stress. But putting in place a variety of initiatives is still simpler and less expensive than dealing with extreme stress once it arrives.

At GlaxoSmithKline, a program called “Team Resilience” combines things like health assessments, discussion groups and follow-up evaluations to deal with workplace stress.

The company’s promotion management group, which develops promotional materials and obtains regulatory approval for them, went through the process last fall. The roughly 100 employees in the group, spread between Philadelphia and Research Triangle Park in North Carolina, completed questionnaires about workplace stress and then met in groups organized by work specialty — editors with editors, designers with designers, and so on — to discuss results.

At the outset, “they thought, ‘Oh no, not another survey, not another class,’” said Karen W. Ruffner, the group director. “But when we set up workshops by functional areas, I think they were pleasantly surprised. It gave them an opportunity to talk among their peers. Sometimes you almost have to force that time for people who are really busy.” The groups are having follow-up meetings to address the issues that surfaced, like a desire for more flexibility in how work is organized, she said.

PricewaterhouseCoopers also addresses stress in multiple ways. For example, in annual surveys, employees asked for more coaching and opportunities to connect with more experienced colleagues — and got them.

Over the past two years, the firm has also created market teams for various business lines, which means that 80 to 100 people work together on a portfolio of client accounts. Employees can cover for one another more easily, easing some of the pressure.

Michael J. Fenlon, managing director for people strategy at PricewaterhouseCoopers, said the surveys found higher satisfaction levels and lower turnover among those in market teams. The goal, he said, was “to create an environment where there’s openness and a sense of mutual support,” he said, “where I can work through life-cycle events and no one’s going to think less of me.”

Until recently, if employees sent e-mails on weekends or after hours, an automatic message would appear asking the sender to wait, if possible, and let others enjoy their down time. The message was discontinued after the company determined that workers had taken this stress-reducing sentiment to heart.

When a Co-Worker Is Stressed Out

By Elizabeth Bernstein

WSJ Article : August 26, 2008

Feeling particularly stressed at work? Look around you.

Even in good times, it's not always easy to keep your cool on the job. But as the economy falters and layoffs sweep certain industries, many people are more worried than ever about job security -- in addition to fretting over the value of their homes, the cost of college and a host of other issues. Making matters worse: Stressed-out bosses and co-workers tend to pass tension on to others.

Most people can handle the strain. But what do you do when you think that the person sitting next to you at work cannot?

If you see a co-worker suffering, it's understandable that you may want to offer help. And if you're the boss, in addition to alleviating distress, you will also need to worry about a worker's productivity, as well as office morale.

Indeed, employers may be held liable for failing to prevent the worst-case scenario -- office violence. Warning signs include direct threats, menacing gestures or statements such as, "You wouldn't miss me if I were gone."

"If you are afraid of someone, there is probably a good reason," says Marina London, Web editor for the Employee Assistance Professionals Association, a membership organization based in Arlington, Va., and a licensed social worker. Experts say that someone who appears to be a threat should be dealt with by managers immediately and carefully, with the help of security.

Subtle Signs

But the vast majority of people suffering from mental stress in the workplace don't become violent, and the warning signs that something is wrong may be more subtle. In fact, by the time you notice that a co-worker has a problem, it's likely been going on for a while. That's why experts suggest intervening early.

Mental-health experts say they're seeing increasing signs of stress this year, with more people seeking professional help for mental strain brought on by financial or work issues. Since the Bear Stearns collapse last spring, calls to employee-assistance programs -- which help people with mental-health and personal problems -- have risen about 10%, according to the Employee Assistance Professionals Association.

"Work conditions can cause mental illness," says Rodney L. Lowman, a psychologist who specializes in occupational mental health and president of Lake Superior State University in Sault Ste. Marie, Mich. "If we put healthy, well-adjusted people in the right foxhole with guns blaring at them, the likelihood of them experiencing depression and anxiety is very high."

Experts say the most significant warning signs are changes in behavior, including work patterns, eating habits or drinking. Someone may start working too hard. He may show up late, appear despondent, withdrawn or abrasive, and seem increasingly annoyed. "Just being different is not the problem. It's the change," says James Campbell Quick, a professor at the University of Texas at Arlington who teaches preventive stress management.

Earlier this summer, Talia Witkowski was struggling through a meeting at the Los Angeles nonprofit organization where she worked when her boss pulled her aside. Dr. Witkowski, a psychologist, says the boss told her she didn't seem as sharp as usual and recommended that she take the rest of the day off to clear her mind. Dr. Witkowski went home, took a walk, wrote in her journal, and prepared a nice dinner for herself. "I was very thankful for her insight and intuition and for having been given the rest of the afternoon off to get back to center," says Dr. Witkowski.

When trying to help someone who is suffering from mental distress, it is critical to approach with empathy. "Let the individual know that you have a sense of understanding where they are coming from," says John Weaver, a psychologist in Waukesha, Wis., who consults with businesses.

It's perfectly fine, and can be helpful, to ask a co-worker how he's doing. But it's important not to be intrusive. "Say, 'I am sure you are experiencing a lot of stress at work; how are you coping?' " says Dr. Lowman. "It's about inviting conversation, not demanding answers."

No Labels

And never suggest that someone has a mental illness. "You always want to describe behavior, rather than label the person," says Ms. London, of the Employee Assistance Professionals Association. "So you don't want to say, 'I think you are anorexic.' You want to say, 'I am very concerned; I think you are losing a great deal of weight.' And you don't want to say, 'I think you are an alcoholic.' You want to say, 'I am worried that every night after work you have six beers.' "

If the colleague you are trying to help appears receptive, you may want to recommend they speak to a mental-health professional at your company's employee-assistance program. Many employers contract with outside firms to offer these services. "The job is encouraging them to go to an appropriate source for help and to get them to do that early rather than later," says Dr. Lowman.

Getting Attached

You should never offer help outside of work, especially if you are the boss. "It always ends badly," says Michael P. Maslanka, a labor and employment law attorney in Dallas. People under duress will sometimes attach themselves to the person who tries to help them and think that the solution to their problems is to talk to this person. They may start requesting increasing amounts of help.

"If it's serious, you need to point out that, 'I am not an expert,' " says Lester Tobias, a psychologist in Westborough, Mass., who specializes in management issues. He suggests saying, " 'I think this is over my head and you really need to talk to a professional if you want to talk.' "

If you are the boss, offering help outside of the office -- calling the doctor to make an appointment, for instance, or offering a ride -- may open you up to liability. Once you undertake the duty to help, the duty continues. If you don't continue with this responsibility in the future, you could be sued for negligence.

Time Off

So if you are the boss, you should offer only work-related help. Hand out the number to your employee-assistance program. Try to lighten someone's workload. Encourage the person to take vacation. Offer additional time off without pay.

And if the worker you're trying to help resists your overture -- and there doesn't seem to be a risk he will hurt someone, including himself, or his productivity isn't suffering -- back off, at least for now.

"You've communicated that you care about them," says Dr. Lowman. And that, he says, "may be helpful in itself."

Stress So Bad It Hurts -- Really

Melinda Beck : WSJ Article : March 20, 2009

"I think your real problem is stress," the doctor said when I complained that the muscle injections he was giving me hadn't relieved my neck and shoulder pain. "You can't blame me for everything that's hard in your life," he said.

My bursting into tears only seemed to confirm his diagnosis.

It's not like I hadn't heard this before. During earlier bouts of low-back pain, irritable-bowel syndrome and temporomandibular joint disorder, plenty of doctors have used the stress word with me. And each time, I've become indignant. It sounded like "it's all in your head" or "you're malingering."

That's an outdated view, says Christopher L. Edwards, director of the Behavioral Chronic Pain Management program at Duke University Medical Center. Decades ago, when doctors said a condition was psychosomatic, it was the equivalent of saying it wasn't real, since there was little evidence that the body and the brain were connected. "Now, we recognize that what happens in the brain affects the body and what happens in the body affects the brain," he says. That knowledge gives us the tools to try to manage the situation, he adds.

Dr. Edwards says his pain-management program in Durham, N.C., is seeing a rise in patients amid the current economic crisis: "There's a very strong relationship between the economy and the number of out-of-control stress cases we see."

From Stress to Pain

Psychological stress can turn into physical pain and illness in a number of ways. One is the body's primitive "fight-or-flight" mechanism. When the brain senses a threat, it activates the sympathetic nervous system and signals the adrenal glands to pump out adrenaline, cortisol and other hormones that prime the body for action. Together, they make the muscles tense up, the digestive tract slow down, blood vessels constrict and the heart beat faster.

That's all very useful for outrunning a mastodon. But when the threat is a tanking stock portfolio or an impending layoff, the state of alarm can last indefinitely. Muscles stay tense and contracted, which can make for migraine headaches, clenched jaws, knots in the neck and shoulders, and pangs in the lower back. Some of those body parts are already under pressure from long hours at the computer, restless sleep, grinding teeth and poor posture.

The Gut Brain

The digestive tract has its own extensive system of nerve cells lining the esophagus, stomach and intestines -- known as the gut brain -- that are extremely sensitive to thoughts and emotions. That's what creates the feeling of butterflies in the stomach. When anxiety persists, it can set off heartburn, indigestion and irritable-bowel syndrome, in which the normal movement of the colon gets out of rhythm, traps painful gas and alternates between diarrhea and constipation.

"Stress does not necessarily cause pain, but it exacerbates the [physical] situation that may already be there. It diminishes your ability to cope," Dr. Edwards says.

Stress also creates biochemical changes that can affect the immune system, making it underreact to viruses and bacterial infections, or overreact, which can set off allergies, asthma and skin disorders like psoriasis and eczema. And stress can raise the level of inflammation in the body, which has been associated with heart disease. A recent study in the journal Psychosomatic Medicine found that stressful conditions even in the teenage years can raise the level of C-reactive protein, a marker for inflammation that increases the likelihood of cardiovascular problems later.

There are plenty of ways to short-circuit these harmful effects of stress. One of the best is physical exercise, which not only releases the feel-good neurotransmitters called endorphins, but also helps use up excess cortisol and adrenaline. Under stress, "there's a large amount of negative emotional energy in your system that is trying to find a way to discharge," says David Whitehouse, a psychiatrist and chief medical officer for OptumHealth Behavioral Solutions, a unit of UnitedHealth Group Inc. He adds that "stress kills brain cells. The body responds by making new ones, and exercise can help activate them and make new connections between them."

Sleeping and Eating

Many experts also recommend getting plenty of sleep, eating regular, balanced meals and keeping up social connections -- all things that people tend to forgo in times of stress.

Biofeedback, once considered alternative medicine, is now accepted in mainstream medical circles as a way for people to reduce the impact of stress. Dr. Edwards runs a biofeedback laboratory at Duke, where patients monitor their heart rates, respiration, temperature and other vital signs and learn to control them with relaxation techniques. "The goal is that once we teach you to do that, you can use it the rest of your life," he says.

Another form of biofeedback is called Heart Rate Variability Training, which teaches people to adjust their breathing to maintain an optimum interval between heart beats that induces a feeling of calm throughout the body. "It's probably similar to what happens in yoga and meditation," says Dr. Whitehouse.

He adds that there is much new research going on in the field of "emotional resilience training" to help people learn to lower their anxiety levels and recover from setbacks. "People spend huge amounts of money, time and energy training their cognitive brains. What we now know is that the emotional brain can be trained as well to become more resilient," Dr. Whitehouse says.

Emotions play a major role in how pain is perceived in the brain. In the 1960s, Ronald Melzack, a Canadian psychologist, and Patrick David Wall, a British physician, offered a groundbreaking theory after observing soldiers in World War II. "Two soldiers with nearly identical injuries from the same bomb blast would be sitting side by side in a hospital ward," Dr. Edwards explains. "One soldier would be saying, 'Hey doc, can you sew me up? I need to get back to my unit.' And the other would be crying, moaning and writhing in pain."

Drs. Melzack and Wall determined that chemical gates in the spinal cord control pain signals from the body to the brain, depending largely on patients' emotional states. Positive emotions diminished the perception of pain, while negative emotions kept the gates open -- sometimes continuing the pain even after the initial cause had disappeared.

Fear versus Fact

There's a growing consensus that cognitive behavioral therapy can be very effective at diffusing negative emotions. It works by examining, and challenging, the thoughts behind them. "We'd say, 'I understand your fear, but fear is not a fact. Let's look at the reality in your life,'" says Katherine Muller, a cognitive therapist and director of psychology training at Montefiore Medical Center in Bronx, N.Y.

It's no surprise that being told that pain is stress related feels like an affront, Dr. Muller says. "There's this idea among high-functioning people that 'I'm a good coper,' and these symptoms suggest that you're not," she says. Indeed, many successful people find that low levels of stress and worry help them function. "But in periods of high stress, that worry takes over and becomes the dominant feeling. You're still going to work. You're still doing stuff for your family, but it's taking a toll. And suddenly your body is saying, 'Whoa -- I can't take the tension any more,'" Dr. Muller says.

One technique she uses is to have patients keep a diary evaluating their stress level on a scale of zero to 10 several times a day and note what was happening at the time. Patterns may emerge -- that headache may set in every Thursday afternoon, after the staff meeting -- and there may be ways to change the situation. "The message I'm trying to send is that you are responsible for your own stress," says Dr. Muller. "The way you are looking at it and feeling about it is more up to you than you realize."

So is stress-related pain all in your head after all? "All pain, and all human experience, is in your head," says Dr. Edwards. But that's a message of hope, he adds, since there are now ways that weren't available 60 years ago to ease pain by managing thoughts and emotions.

All right. Sew me up, doc. I want to get back to my unit -- I think.

So now you know how to recognize how stress may manifest, there is a lot you can do to decrease the stresses in your life. The next link has stress relief suggestions.