- RETIREMENT ANNOUNCEMENT

- HOME PAGE

- "MYCHART" the new patient portal

- BELMONT MEDICAL ASSOCIATES

- MOUNT AUBURN HOSPITAL

- EMERGENCIES

- PRACTICE PHILOSOPHY

- MY RESUME

- TELEMEDICINE CONSULTATION

- CONTACT ME

- LAB RESULTS

- ePRESCRIPTIONS

- eREFERRALS

- RECORD RELEASE

- MEDICAL SCRIBE

- PHYSICIAN ASSISTANT (PA)

- Medicare Annual Wellness Visit

- Case management/Social work

- Quality Care Measures

- Emergency closing notice

- FEEDBACK

- Talking to your doctor

- Choosing..... and losing a doctor

- INDEX A - Z

- ALLERGIC REACTIONS

- Alternative Medicine

- Alzheimer's Disease

- Bladder Problems

- Blood disorders

- Cancer Concerns

- GENETIC TESTING FOR HEREDITARY CANCER

- Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

- Controversial Concerns

- CPR : Learn and save a life

- CRP : Inflammatory marker

- Diabetes Management

- Dizziness, Vertigo,Tinnitus and Hearing Loss

- EXERCISE

- FEMALE HEALTH

-

GASTROINTESTINAL topics

- Appendicitis

- BRAT diet

- Celiac Disease or Sprue

- Crohn's Disease

- Gastroenterologists for Colon Cancer Screening

- Colonoscopy PREP

- Constipation

- Gluten sensitivity, but not celiac disease

- Heartburn and GERD

- Hemorrhoids and Anal fissure

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- NASH : Non Alcoholic Steato Hepatitis

- FEET PROBLEMS

- HEART RELATED topics

-

INFECTIOUS DISEASES

- Antibiotic Resistance

- Cat bites >

- Clostridia difficile infection - the "antibiotic associated germ"

- CORONA VIRUS

- Dengue Fever and Chikungunya Fever

- Food borne illnesses

- Shingles Vaccine

- Hepatitis B

- Hepatitis C

- Herpes

- Influenza

- Helicobacter pylori - the "ulcer germ"

- HIV Screening

- Lyme and other tick borne diseases

- Measles

- Meningitis

- MRSA (Staph infection)

- Norovirus

- Sexually Transmitted Diseases

- Shingles (Herpes Zoster)

- Sinusitis

- West Nile Virus

- Whooping Cough (Pertussis)

- Zika virus and pregnancy

- INSURANCE related topics

- KIDNEY STONES

- LEG CRAMPS

- LIBRARY for patients

- LIFE DECISIONS

- MALE HEALTH

- Medication/Drug side effects

- MEDICAL MARIJUANA

- MENTAL HEALTH

- Miscellaneous Articles

-

NUTRITION - EXERCISE - WEIGHT

- Cholesterol : New guidelines for treatment

- Advice to lower your cholesterol

- Cholesterol : Control

- Cholesterol : Raising your HDL Level

- Exercise

- Food : Making Smart Choices

- Food : Making Poor Choices

- Food : Grape Fruit and Drug Interaction

- Food : Vitamins, Minerals and Supplements

- Omega 3 fatty acids

- Vitamin B12 deficiency

- Vitamin D

- Weight Loss

- ORTHOPEDICS

- PAIN

- PATIENTS' RIGHTS

- SKIN

- SLEEP

- SMOKING

- STROKE

- THYROID

- SUBSTANCE ABUSE

- Travel and Vaccination

- TREMOR

- Warfarin Anticoagulation

- OTHER STUFF FOLLOWS

- Fact or Opinion?

- Hippocratic Oath

- FREE ADVICE.......for what its worth!

- LAUGHTER.....is the best medicine

- Physicians Pet Peeves

- PHOTO ALBUM - its not all work!

- Cape Town, South Africa

- Tribute page

- The 100 Club

- Free Wi-Fi

Balance

Sudden loss of balance or coordination

Eyes

Sudden change in vision

Face

Sudden weakness of the face

Arm

Sudden weakness of an arm or leg

Speech

Sudden difficulty speaking

Time

Time to call 911

Sudden loss of balance or coordination

Eyes

Sudden change in vision

Face

Sudden weakness of the face

Arm

Sudden weakness of an arm or leg

Speech

Sudden difficulty speaking

Time

Time to call 911

The distinguishing characteristic of stroke symptoms is their sudden onset. No matter what a person’s age, the sudden appearance of any of the following symptoms should prompt a trip to the hospital as quickly as possible.

¶ Numbness or weakness of the face, arm or leg, especially on one side of the body.

¶ Confusion, trouble speaking or understanding speech.

¶ Trouble seeing in one or both eyes.

¶ Difficulty walking, dizziness or loss of balance or coordination.

¶ Sudden, severe headache with no known cause.

Unlike a heart attack, most strokes are painless. Even if the initial symptoms dissipate they must be taken seriously.

CT scan doesn’t show strokes very well in the first 24 hours. If the diagnosis is uncertain, an M.R.I. should be done and a neurologist consulted in the emergency room.

¶ Numbness or weakness of the face, arm or leg, especially on one side of the body.

¶ Confusion, trouble speaking or understanding speech.

¶ Trouble seeing in one or both eyes.

¶ Difficulty walking, dizziness or loss of balance or coordination.

¶ Sudden, severe headache with no known cause.

Unlike a heart attack, most strokes are painless. Even if the initial symptoms dissipate they must be taken seriously.

CT scan doesn’t show strokes very well in the first 24 hours. If the diagnosis is uncertain, an M.R.I. should be done and a neurologist consulted in the emergency room.

Stroke

What is a stroke? The brain controls our body movements, processes information from the outside world and allows us to communicate with others. A stroke occurs when part of the brain stops working because of problems with its blood supply. This leads to the classic symptoms of a stroke, such as a sudden weakness affecting the arm and leg on the same side of the body.

The brain is one of the most delicate parts of the body and, tragically, even a short time without a good blood supply can be disastrous. For example, although a finger or even a leg can be successfully saved after many hours without a blood supply, the brain is damaged within minutes. The symptoms of a stroke usually come on quickly and can be very severe. Brain functionIt is useful to describe the structure of the brain to help understand why different sorts of strokes occur.

The brain controls body movement, processes information from the outside world and allows us to communicate with others through a network of nerves that range throughout the body. THE STRUCTURE OF THE BRAIN

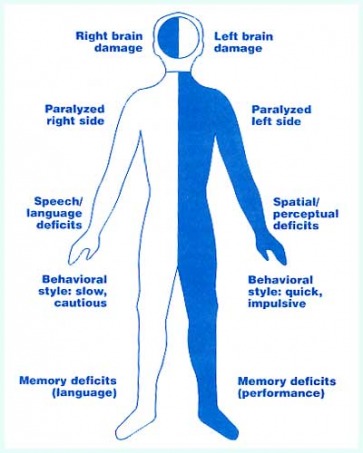

The brain has two hemispheres: the left and the right. Each hemisphere is composed of four lobes. Each of the four lobes of each cerebral hemisphere has its own particular physical and mental functions. These can be impaired by brain damage.

The brain is encased in the bony skull and communicates with the rest of the body through the cranial nerves (which pass through openings in the skull) and the spinal nerves (which pass from the spinal cord through small gaps between the bones of the spine and control the arms, trunk and legs). The brain is made up of three main regions:

The right and left hemispheres communicate through nerve fibre bundles that cross from one side of the body to the other. As a result, the left side of the brain controls the right side of the body and vice versa. A stroke affecting the left side of the brain therefore causes symptoms (for example, weakness) in the right side of the body. In most right-handed people, the left hemisphere is dominant and controls logic and speech, whereas the right hemisphere is involved with imagination and creative thought. This is called left-sided dominance.

The right and left hemispheres communicate with the muscles and sense organs through nerve bundles that cross from one side of the brain to the other. As a result, the left side of the brain controls the right side of the body and vice versa.

The blood supply to the brain is from four main blood vessels – two vertebral arteries and two carotid arteries. The vertebral arteries enter the skull from the backbone and mainly supply the brain stem and cerebellum, whereas the two carotid arteries enter the skull from the front of the neck and mainly supply the two cerebral hemispheres.

All four arteries join up in a rough circle, which helps to maintain an adequate supply of blood if one artery gets blocked. Water mains and electricity supplies operate on similar principles, to try to maintain adequate supplies even if part of the supply breaks down. Unfortunately, the effectiveness of the circle of arteries varies from person to person and often does not protect people from the symptoms of a stroke if one of the main arteries becomes blocked.

The blood is supplied to the brain from the front of the neck and the backbone. The arteries join in a rough circle which helps to maintain an adequate supply of blood if one artery is blocked. Causes of a strokeThe brain uses large amounts of oxygen and nutrients (for example, glucose) which are supplied through the circulation. The most common cause of a stroke is when a blood vessel supplying these vital nutrients to the brain becomes blocked with a blood clot. The blood clot – known as a thrombosis – may form locally in a brain artery or form elsewhere (for example, in the heart) and travel in the bloodstream to lodge in the brain. This type of wandering clot is known as an embolus. When a blood vessel in the brain becomes blocked, the brain cells that it supplies quickly become starved of oxygen and glucose, and stop working properly. If the blood supply is not quickly resumed, these brain cells will die. This type of stroke is called an ischemic stroke, or a ‘cerebral infarct’. The medical term ‘ischemic ’ means a shortage of blood. ‘Cerebral’ is the medical term for the brain and ‘infarct’ is the medical term for death of a part of the body.

The second most common cause of a stroke is a brain hemorrhage, which occurs when a blood vessel bursts inside the head. As well as disrupting the supply of oxygen and glucose to some parts of the brain, the escaping blood can cause damage by clotting, swelling and triggering inflammation.

The most common cause of a stroke is a thrombosis – when a blood vessel supplying vital nutrients to the brain becomes blocked with a blood clot.

There are two types of brain hemorrhage: an intracerebral hemorrhage, when blood collects within the brain; and a subarachnoid hemorrhage, when blood collects between the skull and the brain. Doctors are now recognising some medical conditions that appear to weaken blood vessels and increase the chance of a rupture. High blood pressure certainly seems to be an important cause of an intracerebral hemorrhage. Subarachnoid hemorrhage is mainly caused by the rupture of small swellings – known as aneurysms – which can form in weakened blood vessels, and this problem can run in families.

The second most common cause of a stroke is a brain hemorrhage, which occurs when a blood vessel bursts inside the head.

Any bleed or thromboembolus within the head that causes a loss of function for more than 24 hours (assuming the patient survives) can be called a stroke. Symptoms that last less than 24 hours, and from which there is a complete recovery, are known as a transient ischemic attack (TIA) or mini-stroke.

It is often difficult to tell an ischemic cerebral stroke from a haemorrhagic stroke. Both can cause weakness, numbness or paralysis of part of the body, and may be associated with slurred speech and a loss of consciousness. A hemorrhagic stroke is often accompanied by a severe headache, however, and can be more severe, with widespread damage, so that a prolonged loss of consciousness (coma) is more likely.

Stroke Prevention

Wall Street Journal article by Thomas M. Burton

Patrick Corrado, a small-business owner in Chicago, can utter only a dozen words. In Maryland, Florence Barker no longer works in the family paint store. Lupe Montemayor in California walks with a four-pointed cane, and his wife takes care of him.

They are among a vast fraternity resulting from a great failure of modern American medical care: All suffered massive strokes when seemingly in good health. All would have had a good chance of avoiding their strokes if they had undergone one or two simple and relatively inexpensive diagnostic tests.

While a national heart-disease campaign has caused cardiac deaths to decrease over two decades, strokes and stroke deaths are on the rise. In 2001, 164,000 Americans died of a stroke, up from 144,000 in 1990, making it the third most common cause of death after heart attacks and cancer. And in the four years through 2002, the total number of strokes including nonfatal ones rose to an estimated 700,000 from 600,000.

Stroke is the leading U.S. cause of disability. More than 1.1 million people are impaired and many live in nursing homes.

To prevent stroke, two tests are crucial -- neither of them well-known to the public. One is called a carotid ultrasound. It spots fatty plaque buildup in the carotid arteries on each side of the neck. These small conduits, the diameter of a fountain pen, transport blood to the brain. When plaque and blood clots block blood flow, a stroke occurs and brain tissue dies. Experts estimate that such carotid strokes account for one-third to one-half of all strokes.

Once plaque is found, it can be controlled with drugs and better diet. In advanced cases, it is stripped away in surgery or compressed with tiny wire-mesh carotid stents. Carotid surgery is now a standard, low-mortality operation.

"Roughly one-half of all stroke deaths, and a lot of the permanent disability, could be prevented with the carotid ultrasound test," says William R. Flinn, chief of vascular surgery at the University of Maryland.

Mr. Corrado, 58 years old, knows something about that. He didn't get a carotid ultrasound that could have prevented his stroke 10 years ago, although he would have been a good candidate for the exam. But this year he did get the test -- and it led to an operation his doctor says probably saved his life by preventing another stroke. Though Mr. Corrado barely speaks and can only hobble with a cane, he is able to run his business renting plants to company offices and stays upbeat.

The other test, called the ankle-brachial test, gives a reading on plaque buildup throughout the body's arteries. It is a useful predictor of stroke and heart attacks, and it directly measures "peripheral vascular disease," or fatty deposits in leg arteries that can lead to trouble walking and sometimes amputation. These diseases are all closely related.

The two tests can cost several hundred dollars at hospitals, although it's often possible to find them for much less. Neither the federal Medicare agency nor private insurers pay for them as screening tests. The result: Many people who could get great benefit from having them -- those over 60 and younger people with risk factors for stroke such as high blood pressure and family history -- fail to get them.

It's hard to determine exactly how aggressively the tests should be promoted because the risk factors can't be easily quantified. The economics of broad screening programs are a frequent conundrum of modern medicine. Most experts agree it wouldn't be worth the money and effort to spend billions of dollars testing every American adult for stroke risk.

One reason these tests aren't more widely debated: Stroke is a disease without a fixed home in the medical profession. A person with a knee problem goes to an orthopedist; a person with heart trouble goes to a cardiologist. But a person who has artery problems, the precursor of a stroke, may find himself visiting many kinds of doctors. Radiologists, cardiologists, neurologists and vascular surgeons all share the job. Instead of a unified lobbying effort for screening patients, there are turf wars over who gets to treat them.

One group of specialists -- vascular surgeons and physicians -- focuses on ailments of the arteries and veins. They are the ones pushing hardest for the tests, which would lead to more business for vascular surgeons. But there are only 2,400 vascular surgeons and physicians in the U.S., compared with 22,000 cardiologists. The American Stroke Association, made up largely of neurologists and others who treat patients after strokes, says it's considering more promotion but isn't sure how cost-effective the tests are.

"I'm actually amazed at how slow the medical community has been in adopting these tests," says Eric J. Topol, chairman of cardiovascular medicine at the Cleveland Clinic. "There is no risk, there is little cost and there are hardly any false positives or false negatives."

Carotid-artery blockage is easily detectable because carotid arteries are near the neck's surface. The ultrasound operator, called a sonographer, can thus produce vivid color images of blood-flow changes caused by obstruction. Often, such a test costs $250 or more in hospitals. One private company, Life Line Screening Inc. of Cleveland, offers carotid tests across the U.S. for $45 each.

It's important for patients to get such a test at a lab with experienced technicians. But Life Line Screening has already shown that a carotid test can be accurate and cheap. The Cleveland Clinic's Dr. Topol says a study at the clinic found "a very nice correlation" between Life Line's carotid tests and those of the Cleveland Clinic.

The decades-old ankle-brachial test is in essence a sophisticated blood-pressure test. Hospitals may charge several hundred dollars for it, but it can often be found for less, and LifeLine also gives it for $45. Blood pressures are taken at the ankle and brachial artery in the upper arm. The ratio of pressures should be about 1 to 1. So a normal "ankle-brachial index," or ABI, would be around 1.0. But if the arteries between the arm and ankle are partially blocked, pressure at the ankle will be less than that in the arm. A score of 0.9 means blood-flow blockage is significant enough to be considered abnormal.

If a person gets an ABI score of 0.6 or less, "there is a worse prognosis than from any disease, even than cancer," says Dr. Topol. "In this era of patient empowerment, people should know their ABI. The American public doesn't even know it exists, and it should be standard-of-care."

The ABI is foremost a test for peripheral vascular disease, but plaque buildup in one place likely means plaque buildup elsewhere in the body, which is why the ABI is often used to measure the general health of the blood vessels. "Heart disease, stroke and peripheral-artery disease are all one disease," says Alan T. Hirsch, a vascular doctor at Abbott Northwestern Hospital in Minneapolis. "One gets a lot of attention, one gets very little and the third almost none."

In late 2001, Florence Barker, then 64, was running a paint store with her husband in Hancock, Md. She had a big risk factor for stroke -- years of smoking -- but no obvious signs that her carotid arteries were in trouble. Even her blood pressure was normal. One moment, she was sitting at the kitchen table, then suddenly she was unable to speak.

Now her speech is halting at best, and she is too embarrassed to speak on the telephone. She walks with a limp and still is unable to move her right arm or squeeze the fingers of her right hand. She can no longer read, crochet or work in the family store.

"Her mentality now is more like a child," says her daughter, Helen Barker. "You have to guess what she's saying. It's like she knows the word but can't get it out. If I were like that, I would want to kill myself."

Yet "her stroke was totally preventable with one ultrasound exam," says her surgeon, Dr. Flinn of the University of Maryland. "It's a preventable tragedy."

Some strokes aren't preventable by the carotid test or by the ABI test. A "hemorrhagic" stroke results when a bulge in a blood vessel in the brain bursts. There isn't any cheap screen for people at risk of a hemorrhagic stroke, although those with symptoms such as a severe headache may be given a $1,500 magnetic resonance scan. Other strokes occur because of an irregular heartbeat, called atrial fibrillation, that over decades forms clots that can float to the brain. This danger can generally be detected with an electrocardiogram and controlled with drugs.

STROKE FACTS

But vascular doctors say carotid blockage is the single most common cause of stroke, and anyone with severe blockage is at high risk. Jay S. Yadav, director of vascular intervention at the Cleveland Clinic, says the stroke risk every year is more than 5% when carotid arteries are more than 90% blocked. In such cases surgery or carotid stents are usually required.

From mammograms to cholesterol tests, Americans are flooded with messages urging them to get screened for various diseases. But they hear little about the carotid artery test or the ABI. The American Stroke Association, a unit of the American Heart Association, has instead been educating the public to control risk factors such as high blood pressure and cholesterol. Duke University neurologist Larry Goldstein, formerly chairman of the stroke association's advisory committee on stroke prevention, says, "We can't identify very reliably what the population is" who might benefit from screening.

The stroke association spent $141.4 million last year on stroke research and prevention but didn't put any of it toward evaluating who should receive carotid ultrasound or ankle-brachial screening. Rose Marie Robertson, the stroke association's chief science officer, says that's because "our focus is the development of young investigators. In general, we don't fund large clinical trials."

The organization's Stroke Council, which sets priorities for the group, consists almost entirely of neurologists and others who treat patients after strokes, not beforehand to avoid them. In the view of the Cleveland Clinic's Dr. Topol, the predominance of this type of specialist is a big reason the stroke association hasn't been more aggressive.

"Neurologists are asleep at the wheel," he says. "You'd like to catch people much earlier before the horse is out of the barn."

Robert J. Adams, chairman of the stroke association's advisory committee and a neurologist at the Medical College of Georgia, disputes the notion that neurologists are predisposed against screening. "Science has not shown that carotid screening is a clear winner financially or from a medical standpoint," he says. "Neurologists have been big proponents of stroke prevention from the beginning."

However, Dr. Adams concedes that Dr. Topol has a point. "The issue of whether the American Stroke Association should be more aggressive in screening is one that it should hear," he says. "These screening tests are easy to perform."

Stepping into this vacuum, vascular surgeons have begun to evaluate who should be screened. One big study turned up evidence of prestroke conditions in a broad section of the older population.

In its recent screening of 8,000 Americans over 55, the American Vascular Association found that 7% of patients had more than 50% carotid blockage. This isn't enough for surgery, but it is for drug therapy. Yet about half of the high-risk people weren't on medications. The screening program also found 10% had an ankle-brachial score of 0.85 or worse and should at least be taking drugs.

Dr. Hirsch in Minneapolis and colleagues gave an ankle-brachial test to people over 70, plus people between 50 and 69 with a history of smoking or diabetes. Again, there was extensive silent disease: Peripheral-artery disease was found in 29% of patients, or 1,865 out of 6,979. More than half had no idea they had any disease.

An ankle-brachial index of 0.78 "portends an approximate 30% five-year risk" of heart attack, stroke and "vascular death," Dr. Hirsch and colleagues wrote. But their effort to rivet the nation's attention proved to have terrible timing. Dr. Hirsch was appearing in front of a film crew to publicize the study precisely as terrorists crashed airplanes into the World Trade Center. The research went largely unnoticed.

In Orosi, Calif., Lupe Montemayor was a vigorous 64-year-old, playing softball with his children and teaching building trades. In August 2002, a massive stroke left him unable to use his right arm or leg and unable to work. Afterward, surgeon George Lavenson found a "severe narrowing" of the left carotid artery. "Discovery of the carotid lesion by screening and removal of it by surgery prior to the stroke could have prevented" it, says Dr. Lavenson.

Mr. Montemayor's wife, Maria, quit her job as a dental assistant to take care of him. Unable to tend their five-acre patch of nectarines, peaches and pomegranates, they had to sell it. "It was everything we worked for," says Mrs. Montemayor. "I'm waiting to see if God will let him get back to work."

In Chicago, Mr. Corrado, the plant-company owner, doesn't look like most people's image of a stroke victim. He's a bit stocky, but seemingly healthy with a round face, short brown hair and a grayish beard. His mother died of a stroke and he had uncontrolled high blood pressure when, at 48, he suffered a major stroke in 1994. It hit him in the middle of the night. After he failed to appear at work, employees found him hours afterward.

He was essentially paralyzed. Over several months, he regained some ability to walk, but he still has limited ability to move his right arm or leg. By writing with his left hand, speaking a few words and giving thumbs-up and thumbs-down signs, he can, with the help of an assistant, tell his story.

During therapy, he met dozens of patients who are far more debilitated than he is. "Sad," he says, giving the thumbs-down sign. That's his assessment, too, of the fact that he cannot read because of brain damage. But he can do artwork and run his business. His assessment of the therapists who helped him: "Cool-cool," he says, giving a thumbs-up sign.

Earlier this year, he began to have blurred vision along with pain and muscle spasms on his right side. Doctors ordered a carotid ultrasound that pinpointed the cause -- about 90% blockage of his right carotid artery. The plaque was cleared out with surgery in May. William H. Pearce, chief of vascular surgery at Northwestern Memorial Hospital and Mr. Corrado's surgeon, says that with Mr. Corrado's history, another stroke would have been devastating. "He would probably be dead," says Dr. Pearce.

Instead, after ultrasound and the operation, Mr. Corrado was back running his business within weeks. He now has more energy than before the surgery.

His opinion of the ultrasound test? "Cool-cool," he says. The 5 most common warning signs of stroke:

Lost Chances for Survival, Before and After Stroke

By Gina Kolata

NY Times Article : May 28, 2007

Dr. Diana Fite, a 53-year-old emergency medicine specialist in Houston, knew her blood pressure readings had been dangerously high for five years. But she convinced herself that those measurements, about 200 over 120, did not reflect her actual blood pressure. Anyway, she was too young to take medication. She would worry about her blood pressure when she got older.

Then, at 9:30 the morning of June 7, Dr. Fite was driving, steering with her right hand, holding her cellphone in her left, when, for a split second, the right side of her body felt weak. “I said: ‘This is silly, it’s my imagination. I’ve been working too hard.’

Suddenly, her car began to swerve.

“I realized I had no strength whatsoever in my right hand that was holding the wheel,” Dr. Fite said. “And my right foot was dead. I could not get it off the gas pedal.”

She dropped the cellphone, grabbed the steering wheel with her left hand, and steered the car into a parking lot. Then she used her left foot to pry her right foot off the accelerator. She pulled down the visor to look in the mirror. The right side of her face was paralyzed.

With great difficulty, Dr. Fite twisted her body and grasped her cellphone.

“I called 911, but nothing would come out of my mouth,” she said. Then she found that if she spoke very slowly, she could get out words. So, she recalled, “I said ‘stroke’ in this long, horrible voice.”

Dr. Fite is one of an estimated 700,000 Americans who had a stroke last year, but one of the very few who ended up at a hospital with the equipment and expertise to accurately diagnose and treat it.

Stroke is the third-leading cause of death in this country, behind heart disease and cancer, killing 150,000 Americans a year, leaving many more permanently disabled, and costing the nation $62.7 billion in direct and indirect costs, according to the American Stroke Association.

But from diagnosis to treatment to rehabilitation to preventing it altogether, a stroke is a litany of missed opportunities.

Many patients with stroke symptoms are examined by emergency room doctors who are uncomfortable deciding whether the patient is really having a stroke — a blockage or rupture of a blood vessel in the brain that injures or kills brain cells — or is suffering from another condition. Doctors are therefore reluctant to give the only drug shown to make a real difference, tPA, or tissue plasminogen activator.

Many hospitals say they cannot afford to have neurologists on call to diagnose strokes, and cannot afford to have M.R.I. scanners, the most accurate way to diagnose strokes, for the emergency room.

Although tPA was shown in 1996 to save lives and prevent brain damage, and although the drug could help half of all stroke patients, only 3 percent to 4 percent receive it. Most patients, denying or failing to appreciate their symptoms, wait too long to seek help — tPA must be given within three hours. And even when patients call 911 promptly, most hospitals, often uncertain about stroke diagnoses, do not provide the drug.

“I label this a national tragedy or a national embarrassment,” said Dr. Mark J. Alberts, a neurology professor at the Feinberg School of Medicine at Northwestern University. “I know of no disease that is as common or as serious as stroke and where you basically have one therapy and it’s only used in 3 to 4 percent of patients. That’s like saying you only treat 3 to 4 percent of patients with bacterial pneumonia with antibiotics.”

And the strokes in the statistics are only the beginning. For every stroke that doctors know about, there are 5 to 10 tiny, silent strokes, said Dr. Vladimir Hachinski, the editor of the journal Stroke and a neurologist at the London Health Sciences Centre in Ontario.

“They are only silent because we don’t ask questions,” Dr. Hachinski said. “They do not involve memory, but they involve judgment, planning ahead, shifting your attention from one thing to another. And they also may involve late-life depression.”

They are also warning signs that a much larger stroke may be on the way.

Most strokes would never happen if people took simple measures like controlling their blood pressure. Few do. Many say they forget to take medication; others, like Dr. Fite, decide not to. Some have no idea they need the drugs.

Still, there is much more hope now, said Dr. Ralph L. Sacco, professor and chairman of neurology at the Miller School of Medicine at the University of Miami. Like most stroke neurologists, Dr. Sacco entered the field more than a decade ago, when little could be done for such patients.

Now, Dr. Sacco said, there is a device, an M.R.I. scanner, that greatly improves diagnosis, there is a treatment that works and there are others being tested. “Medical systems have to catch up to the research,” he said.

In medicine, Dr. Sacco said, “stroke is a new frontier.”

Promise Unfulfilled

One Tuesday morning in March, Dr. Steven Warach, chief of the stroke program at the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, met with a team from Washington Hospital Center, the largest private hospital in Washington, to review M.R.I. scans of recently admitted patients. They were joined in a teleconference by neurologists at Suburban Hospital in Bethesda, Md., the only other stroke center in the Washington and suburban Maryland area.

The images were mementos of suffering.

There was a 66-year-old woman with a stroke so big the scan actually showed degenerating fibers that carry nerve signals across the brain.

There was a 75-year-old who had trouble moving her right arm and right side in the recovery room after heart surgery. At first doctors thought she was just slow to wake up from the anesthesia. Now, though, it was clear she had suffered a stroke. She had lost the right half of her vision in both eyes and her right side was weak.

There was an 88-year-old who slumped forward at lunch, losing consciousness. When he came to, he had trouble forming words.

There was a middle-age man whose stroke was unforgettable. When Dr. Warach saw his initial M.R.I. scan, in his basement office at his home, he cried out in astonishment so loudly his wife ran downstairs. “I have never seen anything so severe,” Dr. Warach said. None of the three arteries that supplied the man’s right hemisphere were getting any blood.

Now the man lay in a coma, twitching on his left side, paralyzed on his right, breathing with the help of a ventilator. If he survived, he would have severe brain damage.

There was Michael Collins, a 49-year-old police officer who had had a stroke in his police car in Takoma Park, Md. Unlike the others, Mr. Collins seemed mostly recovered. The next few days, though, would determine whether he was among the lucky 10 percent of stroke patients who escape unscathed or whether he would always be weaker on his left side. If that happened, Mr. Collins said, he could never return to his job.

“You have to be able to shoot a gun with either hand,” he explained. But as time passed, Mr. Collins continued to be plagued by numbness in his left hand and on the left side of his face. He wanted to return to work — “I’m doing great,” he said this month — but the Police Department insisted that he retire, telling him, he said, “it’s an officer safety issue.”

The rest of the patients in the stroke units at the two hospitals that day were less fortunate: almost certain to live, but also almost certain to end up with brain damage. Some would have to spend time at a rehabilitation center.

On average, said Dr. Brendan E. Conroy, medical director of the stroke recovery program at the National Rehabilitation Hospital, which is attached to the Washington Hospital Center, a third of the Washington hospital’s stroke patients die, a third go home and a third come to him.

Those whose balance is affected typically spend 20 days learning to deal with a walker or a cane; those who are partly blind or paralyzed must learn to care for themselves. Many functions return, Dr. Conroy said, but rehabilitation also means learning to live with a disability.

But what was perhaps saddest to the neurologists viewing the M.R.I. scans that morning was that tPA, which only recently appeared to be a triumph of medicine, had made not a whit of difference to these patients. They either had not arrived at the hospital in time or had been considered otherwise medically unsuitable to receive it.

Few would have predicted that fate for the drug. In 1995, after 40 years of trying to find something to break up blood clots in the brain, the cause of most strokes, researchers announced that tPA worked. A large federal study showed that, without it, about one patient in five escaped serious injury. With it, one in three escaped.

The drug had a serious side effect — it could cause potentially life-threatening bleeding in the brain in about 6 percent of patients. But the clinical trial demonstrated that the drug’s benefits outweighed its risks.

When the study’s results were announced, Dr. James Grotta of the University of Texas Medical School at Houston expressed the researchers’ elation. “Until today, stroke was an untreatable disease,” Dr. Grotta said.

But the expected sea change did not occur.

One problem was that patients showed up too late. Many had no choice. Strokes often occur in the morning when people are sleeping. They awake with terrifying symptoms, paralyzed on one side or unable to speak.

“That’s the challenge — we have to ask the patient” when the stroke began, said Dr. A. Gregory Sorensen, a co-director of the Athinoula A. Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging at Massachusetts General Hospital. “If they don’t know or can’t talk, we’re out of luck.”

Another problem is deciding whether a patient is really having a stroke. A person who has trouble forming words could just be confused. Or what about someone whose arm or leg is weak?

“A lot of things can cause weakness,” Dr. Warach said. “A nerve injury can cause weakness; sometimes brain tumors can be suddenly symptomatic. Sometimes people have migraines that can completely mimic a stroke.”

In fact, he said, a quarter of emergency room patients with symptoms suggestive of a stroke are not actually having one.

Most get CT scans, which are useful mostly to rule out hemorrhagic strokes, the less common type that is caused by bleeding in the brain and should not be treated with tPA. Stroke specialists can usually then decide whether the patient is having a stroke caused by a blocked blood vessel and whether it can be treated with tPA.

But most stroke patients are handled by emergency room physicians who often say they are not sure of the diagnosis and therefore hesitate to give tPA.

Dr. Richard Burgess, a member of Dr. Warach’s stroke team, explained the situation: There is no particular penalty for not giving tPA. Doctors are unlikely to be sued if the patient dies or is left with brain damage that could have been avoided. But there is a penalty for giving tPA to someone who is not having a stroke. If that patient bleeds into the brain, the drug not only caused a tragic outcome but the doctor could also be sued. Few emergency room doctors want to take that chance.

Treatment Barriers

There is a way to diagnose strokes more accurately — with a diffusion M.R.I., a type of scan that shows water moving in the brain. During a stroke, the flow of water slows to a crawl as dead and dying cells swell. In one recent study, diffusion M.R.I. scans found five times as many strokes as CT scans, with twice the accuracy.

A diffusion M.R.I. “answers the question 95 percent of the time," Dr. Sorensen said.

It seemed the perfect solution, but it was not.

Most hospitals say they cannot provide such scans to stroke patients. They would need both an M.R.I. technician and an expert to interpret the scans around the clock. They would need an M.R.I. machine near the emergency room. Most hospitals have the huge machines elsewhere, steadily booked far in advance for other patients.

It is simply not practical to demand the scans at every hospital or even every stroke center, said Dr. Edward C. Jauch, an emergency medicine doctor at the University of Cincinnati and a member of the Greater Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky Stroke Team.

“If you made M.R.I. the standard of care before giving tPA, most centers would not be able to comply,” Dr. Jauch said. And if it takes more time to get a scan — as it often does — it might be better to forgo it and give tPA immediately if the patient’s symptoms seem unambiguous.

Doctors do not need an M.R.I. to diagnose and treat stroke, said Dr. Lee H. Schwamm, vice chairman of the department of neurology at Massachusetts General Hospital. But, Dr. Schwamm added, if the question is whether it helps, there is one reply: “By all means.”

It has still not been shown, though, that M.R.I. scans actually improve outcomes. It might depend on the circumstances and the hospital, said Dr. Walter J. Koroshetz, deputy director of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke.

But some who use M.R.I. scans, and who have studied them in research, say the system has to change. They say enough is known about the scans to advocate having them at every major medical center that will treat stroke patients.

“All these problems could be solved if there was a will to do it,” Dr. Sorensen said. In his opinion, it comes down to old and outdated assumptions that there is not much to be done for a stroke, to financial considerations and to a medical system that resists change. But the most significant barriers, he said, are financial.

Another approach, stroke specialists say, is to direct all patients with stroke symptoms to designated stroke centers. There, stroke patients would be treated by experienced neurologists and admitted to stroke units for additional care. For the first time, in its newly published guidelines, the American Stroke Association recommended the routing of patients to stroke centers.

But even with such a system in place, many patients end up at hospitals that are not prepared to treat them, as Dr. Grotta discovered in Houston.

He thought he could change stroke care in Houston with the stroke center idea. The first step went well — the city’s ambulance services agreed to take all patients with stroke symptoms to designated stroke centers.

Then, Dr. David E. Persse, the city’s director of emergency medical services, asked every one of Houston’s 25 hospitals if it wanted to be a stroke center. While seven have said yes, others have declined.

Stroke patients, unlike heart attack patients, are not moneymakers. Because of the way medical care is reimbursed, most hospitals either lose money or do little more than break even with stroke care but can often make several thousand dollars opening the arteries of a heart attack patient. And being a stroke center means finding and paying stroke specialists to be available around the clock.

Soon another problem emerged. As many as a third of the patients refused to let the ambulance take them to a stroke center, demanding to go to their local hospital.

“By law in Texas, we cannot take that man to another hospital against his will,” Dr. Persse said. “We could be charged with assault and battery and kidnapping and unlawful imprisonment.”

The Joint Commission, which accredits hospitals, recently started certifying stroke centers, requiring that the hospitals be willing to treat stroke patients aggressively. But only 322 of the 4,280 accredited hospitals in the nation qualify, and most patients and doctors have no idea whether a hospital nearby is among them. (The list is available on the site http://www.jointcommission.org/CertificationPrograms/Disease-SpecificCare/DSCOrgs/ under “primary stroke centers.”) Some states, like New York, Massachusetts and Florida, do their own certifying of stroke centers.

Nonetheless, most ambulances do not consider stroke center designations when they transport patients. And, said John Becknell, a spokesman for the National Association of Emergency Medical Technicians, national programs can be difficult because every community has its own rules for which ambulances pick up patients and where they take them.

As a result, most stroke patients have no access to the recommended care and even fewer get M.R.I.’s, a situation Dr. Warach said he found appalling.

“How can it ever be in the patient’s best interest to have an inferior diagnosis?” he asked. “It borders on malpractice that given a choice between two noninvasive tests, one of which is clearly superior, the worse test is the one that is preferred.”

Averting Catastrophe

In those awful moments when she realized she had had a stroke, Dr. Fite, unlike most patients, knew what to do. She told the ambulance crew to take her to Memorial Hermann Hospital, even though it was about an hour away. She knew that it was one of the Houston stroke centers, that Dr. Grotta worked there, and that its doctors had experience diagnosing strokes and giving tPA.

When she arrived, Dr. Grotta asked if she was sure she wanted the drug. Did she want to risk bleeding in the brain? Dr. Fite did not hesitate. The stroke, she said, “was just so devastating that I would rather die of a hemorrhage in the brain than be left completely paralyzed in my right side.”

“In my horrible voice, I said, ‘Yes, I want the tPA,’ ” Dr. Fite said.

Within 10 to 15 minutes, the drug started to dissolve the clot.

“I had weird spasms as nerves started to work again,” Dr. Fite said. “An arm would draw up real quick, a leg would tighten up. It hurt so bad I was crying because of the pain. But it was movement, and I knew something was going on.”

Now, she looks back with dismay on her cavalier attitude toward high blood pressure. She knew very well how to prevent a stroke but, like many patients and despite her medical training, she found it all too easy to deny her own risk.

Researchers have known for years the conditions that predispose a person to stroke — smoking, diabetes, high cholesterol and an irregular heartbeat known as atrial fibrillation. But the major one is high blood pressure.

“Of all the modifiable risk factors, high blood pressure leads the list,” Dr. Sacco said. “With heart disease, you think more of cholesterol; with stroke you think of high blood pressure.”

The reason, Dr. Sacco said, is that with high blood pressure, the tiny blood vessels in the brain clamp down so much and so hard to protect the brain that they can become rigid. Then they get blocked. The result is a stroke.

Often, people decide they do not need their blood pressure medication or simply forget to take it because they feel well. But, Dr. Sacco said, patients are not solely to blame. Doctors may not have time to work with patients, monitoring blood pressure, telling them about changes in their diet and exercise that might help, or trying different drugs and combining them if necessary.

And it is not so simple for people to keep track of their blood pressure. Machines in drugstores and supermarkets are not always accurate. Doctors may require appointments to check blood pressure.

Even when people do try to control their pressure, doctors may not prescribe enough drugs or high enough doses.

“They’re on a couple of drugs, and the doctor doesn’t want to push it,” said Dr. Jeffrey A. Cutler, a consultant to the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute and a retired director of its clinical applications and prevention program.

The result is that no more than half the people with high blood pressure have it under control, Dr. Cutler said. He estimated that half of all strokes could be prevented if people kept their blood pressure within the recommended range.

Another lost opportunity to prevent strokes is the undertreatment of atrial fibrillation, in which the two upper chambers of the heart quiver. Blood can pool in the heart and clot, and those clots can be swept into the brain, lodge in a small blood vessel and cause a stroke.

Strokes from atrial fibrillation can largely be prevented with anticlotting drugs like warfarin. Yet many who have the condition do not know it and many who know they have it were never given or do not take an anticlotting drug.

Some strokes can also be prevented by procedures to open obstructed arteries in the neck that supply blood to the brain.

As for Dr. Fite, she completely recovered. And she has changed her ways.

She was sobered by the cost of her treatment and brief hospital stay — $96,000, most of which was paid by her insurance company. But she was even more sobered by how close she came to catastrophe.

Now, Dr. Fite takes three blood pressure pills, a drug to prevent blood clots and a cholesterol-lowering drug. She plans to take those drugs every day for the rest of her life.

“I was so stupid,” she said. “Boy, when you go through this, you never want to go through it again.”

“I have been given that precious second chance,” she said. “I was so blessed.”

The brain is one of the most delicate parts of the body and, tragically, even a short time without a good blood supply can be disastrous. For example, although a finger or even a leg can be successfully saved after many hours without a blood supply, the brain is damaged within minutes. The symptoms of a stroke usually come on quickly and can be very severe. Brain functionIt is useful to describe the structure of the brain to help understand why different sorts of strokes occur.

The brain controls body movement, processes information from the outside world and allows us to communicate with others through a network of nerves that range throughout the body. THE STRUCTURE OF THE BRAIN

The brain has two hemispheres: the left and the right. Each hemisphere is composed of four lobes. Each of the four lobes of each cerebral hemisphere has its own particular physical and mental functions. These can be impaired by brain damage.

The brain is encased in the bony skull and communicates with the rest of the body through the cranial nerves (which pass through openings in the skull) and the spinal nerves (which pass from the spinal cord through small gaps between the bones of the spine and control the arms, trunk and legs). The brain is made up of three main regions:

- the brain stem

- the cerebellum

- the cerebral hemispheres.

The right and left hemispheres communicate through nerve fibre bundles that cross from one side of the body to the other. As a result, the left side of the brain controls the right side of the body and vice versa. A stroke affecting the left side of the brain therefore causes symptoms (for example, weakness) in the right side of the body. In most right-handed people, the left hemisphere is dominant and controls logic and speech, whereas the right hemisphere is involved with imagination and creative thought. This is called left-sided dominance.

The right and left hemispheres communicate with the muscles and sense organs through nerve bundles that cross from one side of the brain to the other. As a result, the left side of the brain controls the right side of the body and vice versa.

The blood supply to the brain is from four main blood vessels – two vertebral arteries and two carotid arteries. The vertebral arteries enter the skull from the backbone and mainly supply the brain stem and cerebellum, whereas the two carotid arteries enter the skull from the front of the neck and mainly supply the two cerebral hemispheres.

All four arteries join up in a rough circle, which helps to maintain an adequate supply of blood if one artery gets blocked. Water mains and electricity supplies operate on similar principles, to try to maintain adequate supplies even if part of the supply breaks down. Unfortunately, the effectiveness of the circle of arteries varies from person to person and often does not protect people from the symptoms of a stroke if one of the main arteries becomes blocked.

The blood is supplied to the brain from the front of the neck and the backbone. The arteries join in a rough circle which helps to maintain an adequate supply of blood if one artery is blocked. Causes of a strokeThe brain uses large amounts of oxygen and nutrients (for example, glucose) which are supplied through the circulation. The most common cause of a stroke is when a blood vessel supplying these vital nutrients to the brain becomes blocked with a blood clot. The blood clot – known as a thrombosis – may form locally in a brain artery or form elsewhere (for example, in the heart) and travel in the bloodstream to lodge in the brain. This type of wandering clot is known as an embolus. When a blood vessel in the brain becomes blocked, the brain cells that it supplies quickly become starved of oxygen and glucose, and stop working properly. If the blood supply is not quickly resumed, these brain cells will die. This type of stroke is called an ischemic stroke, or a ‘cerebral infarct’. The medical term ‘ischemic ’ means a shortage of blood. ‘Cerebral’ is the medical term for the brain and ‘infarct’ is the medical term for death of a part of the body.

The second most common cause of a stroke is a brain hemorrhage, which occurs when a blood vessel bursts inside the head. As well as disrupting the supply of oxygen and glucose to some parts of the brain, the escaping blood can cause damage by clotting, swelling and triggering inflammation.

The most common cause of a stroke is a thrombosis – when a blood vessel supplying vital nutrients to the brain becomes blocked with a blood clot.

There are two types of brain hemorrhage: an intracerebral hemorrhage, when blood collects within the brain; and a subarachnoid hemorrhage, when blood collects between the skull and the brain. Doctors are now recognising some medical conditions that appear to weaken blood vessels and increase the chance of a rupture. High blood pressure certainly seems to be an important cause of an intracerebral hemorrhage. Subarachnoid hemorrhage is mainly caused by the rupture of small swellings – known as aneurysms – which can form in weakened blood vessels, and this problem can run in families.

The second most common cause of a stroke is a brain hemorrhage, which occurs when a blood vessel bursts inside the head.

Any bleed or thromboembolus within the head that causes a loss of function for more than 24 hours (assuming the patient survives) can be called a stroke. Symptoms that last less than 24 hours, and from which there is a complete recovery, are known as a transient ischemic attack (TIA) or mini-stroke.

It is often difficult to tell an ischemic cerebral stroke from a haemorrhagic stroke. Both can cause weakness, numbness or paralysis of part of the body, and may be associated with slurred speech and a loss of consciousness. A hemorrhagic stroke is often accompanied by a severe headache, however, and can be more severe, with widespread damage, so that a prolonged loss of consciousness (coma) is more likely.

Stroke Prevention

Wall Street Journal article by Thomas M. Burton

Patrick Corrado, a small-business owner in Chicago, can utter only a dozen words. In Maryland, Florence Barker no longer works in the family paint store. Lupe Montemayor in California walks with a four-pointed cane, and his wife takes care of him.

They are among a vast fraternity resulting from a great failure of modern American medical care: All suffered massive strokes when seemingly in good health. All would have had a good chance of avoiding their strokes if they had undergone one or two simple and relatively inexpensive diagnostic tests.

While a national heart-disease campaign has caused cardiac deaths to decrease over two decades, strokes and stroke deaths are on the rise. In 2001, 164,000 Americans died of a stroke, up from 144,000 in 1990, making it the third most common cause of death after heart attacks and cancer. And in the four years through 2002, the total number of strokes including nonfatal ones rose to an estimated 700,000 from 600,000.

Stroke is the leading U.S. cause of disability. More than 1.1 million people are impaired and many live in nursing homes.

To prevent stroke, two tests are crucial -- neither of them well-known to the public. One is called a carotid ultrasound. It spots fatty plaque buildup in the carotid arteries on each side of the neck. These small conduits, the diameter of a fountain pen, transport blood to the brain. When plaque and blood clots block blood flow, a stroke occurs and brain tissue dies. Experts estimate that such carotid strokes account for one-third to one-half of all strokes.

Once plaque is found, it can be controlled with drugs and better diet. In advanced cases, it is stripped away in surgery or compressed with tiny wire-mesh carotid stents. Carotid surgery is now a standard, low-mortality operation.

"Roughly one-half of all stroke deaths, and a lot of the permanent disability, could be prevented with the carotid ultrasound test," says William R. Flinn, chief of vascular surgery at the University of Maryland.

Mr. Corrado, 58 years old, knows something about that. He didn't get a carotid ultrasound that could have prevented his stroke 10 years ago, although he would have been a good candidate for the exam. But this year he did get the test -- and it led to an operation his doctor says probably saved his life by preventing another stroke. Though Mr. Corrado barely speaks and can only hobble with a cane, he is able to run his business renting plants to company offices and stays upbeat.

The other test, called the ankle-brachial test, gives a reading on plaque buildup throughout the body's arteries. It is a useful predictor of stroke and heart attacks, and it directly measures "peripheral vascular disease," or fatty deposits in leg arteries that can lead to trouble walking and sometimes amputation. These diseases are all closely related.

The two tests can cost several hundred dollars at hospitals, although it's often possible to find them for much less. Neither the federal Medicare agency nor private insurers pay for them as screening tests. The result: Many people who could get great benefit from having them -- those over 60 and younger people with risk factors for stroke such as high blood pressure and family history -- fail to get them.

It's hard to determine exactly how aggressively the tests should be promoted because the risk factors can't be easily quantified. The economics of broad screening programs are a frequent conundrum of modern medicine. Most experts agree it wouldn't be worth the money and effort to spend billions of dollars testing every American adult for stroke risk.

One reason these tests aren't more widely debated: Stroke is a disease without a fixed home in the medical profession. A person with a knee problem goes to an orthopedist; a person with heart trouble goes to a cardiologist. But a person who has artery problems, the precursor of a stroke, may find himself visiting many kinds of doctors. Radiologists, cardiologists, neurologists and vascular surgeons all share the job. Instead of a unified lobbying effort for screening patients, there are turf wars over who gets to treat them.

One group of specialists -- vascular surgeons and physicians -- focuses on ailments of the arteries and veins. They are the ones pushing hardest for the tests, which would lead to more business for vascular surgeons. But there are only 2,400 vascular surgeons and physicians in the U.S., compared with 22,000 cardiologists. The American Stroke Association, made up largely of neurologists and others who treat patients after strokes, says it's considering more promotion but isn't sure how cost-effective the tests are.

"I'm actually amazed at how slow the medical community has been in adopting these tests," says Eric J. Topol, chairman of cardiovascular medicine at the Cleveland Clinic. "There is no risk, there is little cost and there are hardly any false positives or false negatives."

Carotid-artery blockage is easily detectable because carotid arteries are near the neck's surface. The ultrasound operator, called a sonographer, can thus produce vivid color images of blood-flow changes caused by obstruction. Often, such a test costs $250 or more in hospitals. One private company, Life Line Screening Inc. of Cleveland, offers carotid tests across the U.S. for $45 each.

It's important for patients to get such a test at a lab with experienced technicians. But Life Line Screening has already shown that a carotid test can be accurate and cheap. The Cleveland Clinic's Dr. Topol says a study at the clinic found "a very nice correlation" between Life Line's carotid tests and those of the Cleveland Clinic.

The decades-old ankle-brachial test is in essence a sophisticated blood-pressure test. Hospitals may charge several hundred dollars for it, but it can often be found for less, and LifeLine also gives it for $45. Blood pressures are taken at the ankle and brachial artery in the upper arm. The ratio of pressures should be about 1 to 1. So a normal "ankle-brachial index," or ABI, would be around 1.0. But if the arteries between the arm and ankle are partially blocked, pressure at the ankle will be less than that in the arm. A score of 0.9 means blood-flow blockage is significant enough to be considered abnormal.

If a person gets an ABI score of 0.6 or less, "there is a worse prognosis than from any disease, even than cancer," says Dr. Topol. "In this era of patient empowerment, people should know their ABI. The American public doesn't even know it exists, and it should be standard-of-care."

The ABI is foremost a test for peripheral vascular disease, but plaque buildup in one place likely means plaque buildup elsewhere in the body, which is why the ABI is often used to measure the general health of the blood vessels. "Heart disease, stroke and peripheral-artery disease are all one disease," says Alan T. Hirsch, a vascular doctor at Abbott Northwestern Hospital in Minneapolis. "One gets a lot of attention, one gets very little and the third almost none."

In late 2001, Florence Barker, then 64, was running a paint store with her husband in Hancock, Md. She had a big risk factor for stroke -- years of smoking -- but no obvious signs that her carotid arteries were in trouble. Even her blood pressure was normal. One moment, she was sitting at the kitchen table, then suddenly she was unable to speak.

Now her speech is halting at best, and she is too embarrassed to speak on the telephone. She walks with a limp and still is unable to move her right arm or squeeze the fingers of her right hand. She can no longer read, crochet or work in the family store.

"Her mentality now is more like a child," says her daughter, Helen Barker. "You have to guess what she's saying. It's like she knows the word but can't get it out. If I were like that, I would want to kill myself."

Yet "her stroke was totally preventable with one ultrasound exam," says her surgeon, Dr. Flinn of the University of Maryland. "It's a preventable tragedy."

Some strokes aren't preventable by the carotid test or by the ABI test. A "hemorrhagic" stroke results when a bulge in a blood vessel in the brain bursts. There isn't any cheap screen for people at risk of a hemorrhagic stroke, although those with symptoms such as a severe headache may be given a $1,500 magnetic resonance scan. Other strokes occur because of an irregular heartbeat, called atrial fibrillation, that over decades forms clots that can float to the brain. This danger can generally be detected with an electrocardiogram and controlled with drugs.

STROKE FACTS

- Each year, about 700,000 Americans have a new or recurrent stroke. About 500,000 of these are new.

- One-third to one-half are estimated to be caused by carotid-artery blockage.

- Eighty-eight percent are "ischemic," meaning that blood flow to the brain is blocked, typically by plaque or clots; 12% are "hemorrhagic," involving a burst aneurysm or artery in or near the brain.

- In a recent study, more than 1.1 million American adults had difficulty functioning in activities including daily living because of strokes.

- The estimated direct and indirect cost of stroke in 2004 is $53.6 billion.

- The age-adjusted stroke incidence rates per 100,000 people per year are 167 for white men, 138 for white women, 323 for African-American men and 260 for African-American women.

- Sometimes strokes are preceded by ministrokes called "transient ischemic attacks." Symptoms can include sudden blindness in one eye, loss of sensations on one side of body, paralysis on one side or in an arm or leg, slurred speech, dizziness, and difficulty in thinking of or saying the appropriate word.

But vascular doctors say carotid blockage is the single most common cause of stroke, and anyone with severe blockage is at high risk. Jay S. Yadav, director of vascular intervention at the Cleveland Clinic, says the stroke risk every year is more than 5% when carotid arteries are more than 90% blocked. In such cases surgery or carotid stents are usually required.

From mammograms to cholesterol tests, Americans are flooded with messages urging them to get screened for various diseases. But they hear little about the carotid artery test or the ABI. The American Stroke Association, a unit of the American Heart Association, has instead been educating the public to control risk factors such as high blood pressure and cholesterol. Duke University neurologist Larry Goldstein, formerly chairman of the stroke association's advisory committee on stroke prevention, says, "We can't identify very reliably what the population is" who might benefit from screening.

The stroke association spent $141.4 million last year on stroke research and prevention but didn't put any of it toward evaluating who should receive carotid ultrasound or ankle-brachial screening. Rose Marie Robertson, the stroke association's chief science officer, says that's because "our focus is the development of young investigators. In general, we don't fund large clinical trials."

The organization's Stroke Council, which sets priorities for the group, consists almost entirely of neurologists and others who treat patients after strokes, not beforehand to avoid them. In the view of the Cleveland Clinic's Dr. Topol, the predominance of this type of specialist is a big reason the stroke association hasn't been more aggressive.

"Neurologists are asleep at the wheel," he says. "You'd like to catch people much earlier before the horse is out of the barn."

Robert J. Adams, chairman of the stroke association's advisory committee and a neurologist at the Medical College of Georgia, disputes the notion that neurologists are predisposed against screening. "Science has not shown that carotid screening is a clear winner financially or from a medical standpoint," he says. "Neurologists have been big proponents of stroke prevention from the beginning."

However, Dr. Adams concedes that Dr. Topol has a point. "The issue of whether the American Stroke Association should be more aggressive in screening is one that it should hear," he says. "These screening tests are easy to perform."

Stepping into this vacuum, vascular surgeons have begun to evaluate who should be screened. One big study turned up evidence of prestroke conditions in a broad section of the older population.

In its recent screening of 8,000 Americans over 55, the American Vascular Association found that 7% of patients had more than 50% carotid blockage. This isn't enough for surgery, but it is for drug therapy. Yet about half of the high-risk people weren't on medications. The screening program also found 10% had an ankle-brachial score of 0.85 or worse and should at least be taking drugs.

Dr. Hirsch in Minneapolis and colleagues gave an ankle-brachial test to people over 70, plus people between 50 and 69 with a history of smoking or diabetes. Again, there was extensive silent disease: Peripheral-artery disease was found in 29% of patients, or 1,865 out of 6,979. More than half had no idea they had any disease.

An ankle-brachial index of 0.78 "portends an approximate 30% five-year risk" of heart attack, stroke and "vascular death," Dr. Hirsch and colleagues wrote. But their effort to rivet the nation's attention proved to have terrible timing. Dr. Hirsch was appearing in front of a film crew to publicize the study precisely as terrorists crashed airplanes into the World Trade Center. The research went largely unnoticed.

In Orosi, Calif., Lupe Montemayor was a vigorous 64-year-old, playing softball with his children and teaching building trades. In August 2002, a massive stroke left him unable to use his right arm or leg and unable to work. Afterward, surgeon George Lavenson found a "severe narrowing" of the left carotid artery. "Discovery of the carotid lesion by screening and removal of it by surgery prior to the stroke could have prevented" it, says Dr. Lavenson.

Mr. Montemayor's wife, Maria, quit her job as a dental assistant to take care of him. Unable to tend their five-acre patch of nectarines, peaches and pomegranates, they had to sell it. "It was everything we worked for," says Mrs. Montemayor. "I'm waiting to see if God will let him get back to work."

In Chicago, Mr. Corrado, the plant-company owner, doesn't look like most people's image of a stroke victim. He's a bit stocky, but seemingly healthy with a round face, short brown hair and a grayish beard. His mother died of a stroke and he had uncontrolled high blood pressure when, at 48, he suffered a major stroke in 1994. It hit him in the middle of the night. After he failed to appear at work, employees found him hours afterward.

He was essentially paralyzed. Over several months, he regained some ability to walk, but he still has limited ability to move his right arm or leg. By writing with his left hand, speaking a few words and giving thumbs-up and thumbs-down signs, he can, with the help of an assistant, tell his story.

During therapy, he met dozens of patients who are far more debilitated than he is. "Sad," he says, giving the thumbs-down sign. That's his assessment, too, of the fact that he cannot read because of brain damage. But he can do artwork and run his business. His assessment of the therapists who helped him: "Cool-cool," he says, giving a thumbs-up sign.

Earlier this year, he began to have blurred vision along with pain and muscle spasms on his right side. Doctors ordered a carotid ultrasound that pinpointed the cause -- about 90% blockage of his right carotid artery. The plaque was cleared out with surgery in May. William H. Pearce, chief of vascular surgery at Northwestern Memorial Hospital and Mr. Corrado's surgeon, says that with Mr. Corrado's history, another stroke would have been devastating. "He would probably be dead," says Dr. Pearce.

Instead, after ultrasound and the operation, Mr. Corrado was back running his business within weeks. He now has more energy than before the surgery.

His opinion of the ultrasound test? "Cool-cool," he says. The 5 most common warning signs of stroke:

- sudden numbness or weakness

- dim vision

- dizziness

- severe headache

- confusion or difficulty speaking

Lost Chances for Survival, Before and After Stroke

By Gina Kolata

NY Times Article : May 28, 2007

Dr. Diana Fite, a 53-year-old emergency medicine specialist in Houston, knew her blood pressure readings had been dangerously high for five years. But she convinced herself that those measurements, about 200 over 120, did not reflect her actual blood pressure. Anyway, she was too young to take medication. She would worry about her blood pressure when she got older.

Then, at 9:30 the morning of June 7, Dr. Fite was driving, steering with her right hand, holding her cellphone in her left, when, for a split second, the right side of her body felt weak. “I said: ‘This is silly, it’s my imagination. I’ve been working too hard.’

Suddenly, her car began to swerve.

“I realized I had no strength whatsoever in my right hand that was holding the wheel,” Dr. Fite said. “And my right foot was dead. I could not get it off the gas pedal.”

She dropped the cellphone, grabbed the steering wheel with her left hand, and steered the car into a parking lot. Then she used her left foot to pry her right foot off the accelerator. She pulled down the visor to look in the mirror. The right side of her face was paralyzed.

With great difficulty, Dr. Fite twisted her body and grasped her cellphone.

“I called 911, but nothing would come out of my mouth,” she said. Then she found that if she spoke very slowly, she could get out words. So, she recalled, “I said ‘stroke’ in this long, horrible voice.”

Dr. Fite is one of an estimated 700,000 Americans who had a stroke last year, but one of the very few who ended up at a hospital with the equipment and expertise to accurately diagnose and treat it.

Stroke is the third-leading cause of death in this country, behind heart disease and cancer, killing 150,000 Americans a year, leaving many more permanently disabled, and costing the nation $62.7 billion in direct and indirect costs, according to the American Stroke Association.

But from diagnosis to treatment to rehabilitation to preventing it altogether, a stroke is a litany of missed opportunities.

Many patients with stroke symptoms are examined by emergency room doctors who are uncomfortable deciding whether the patient is really having a stroke — a blockage or rupture of a blood vessel in the brain that injures or kills brain cells — or is suffering from another condition. Doctors are therefore reluctant to give the only drug shown to make a real difference, tPA, or tissue plasminogen activator.

Many hospitals say they cannot afford to have neurologists on call to diagnose strokes, and cannot afford to have M.R.I. scanners, the most accurate way to diagnose strokes, for the emergency room.

Although tPA was shown in 1996 to save lives and prevent brain damage, and although the drug could help half of all stroke patients, only 3 percent to 4 percent receive it. Most patients, denying or failing to appreciate their symptoms, wait too long to seek help — tPA must be given within three hours. And even when patients call 911 promptly, most hospitals, often uncertain about stroke diagnoses, do not provide the drug.

“I label this a national tragedy or a national embarrassment,” said Dr. Mark J. Alberts, a neurology professor at the Feinberg School of Medicine at Northwestern University. “I know of no disease that is as common or as serious as stroke and where you basically have one therapy and it’s only used in 3 to 4 percent of patients. That’s like saying you only treat 3 to 4 percent of patients with bacterial pneumonia with antibiotics.”

And the strokes in the statistics are only the beginning. For every stroke that doctors know about, there are 5 to 10 tiny, silent strokes, said Dr. Vladimir Hachinski, the editor of the journal Stroke and a neurologist at the London Health Sciences Centre in Ontario.

“They are only silent because we don’t ask questions,” Dr. Hachinski said. “They do not involve memory, but they involve judgment, planning ahead, shifting your attention from one thing to another. And they also may involve late-life depression.”

They are also warning signs that a much larger stroke may be on the way.

Most strokes would never happen if people took simple measures like controlling their blood pressure. Few do. Many say they forget to take medication; others, like Dr. Fite, decide not to. Some have no idea they need the drugs.

Still, there is much more hope now, said Dr. Ralph L. Sacco, professor and chairman of neurology at the Miller School of Medicine at the University of Miami. Like most stroke neurologists, Dr. Sacco entered the field more than a decade ago, when little could be done for such patients.

Now, Dr. Sacco said, there is a device, an M.R.I. scanner, that greatly improves diagnosis, there is a treatment that works and there are others being tested. “Medical systems have to catch up to the research,” he said.

In medicine, Dr. Sacco said, “stroke is a new frontier.”

Promise Unfulfilled

One Tuesday morning in March, Dr. Steven Warach, chief of the stroke program at the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, met with a team from Washington Hospital Center, the largest private hospital in Washington, to review M.R.I. scans of recently admitted patients. They were joined in a teleconference by neurologists at Suburban Hospital in Bethesda, Md., the only other stroke center in the Washington and suburban Maryland area.

The images were mementos of suffering.

There was a 66-year-old woman with a stroke so big the scan actually showed degenerating fibers that carry nerve signals across the brain.

There was a 75-year-old who had trouble moving her right arm and right side in the recovery room after heart surgery. At first doctors thought she was just slow to wake up from the anesthesia. Now, though, it was clear she had suffered a stroke. She had lost the right half of her vision in both eyes and her right side was weak.

There was an 88-year-old who slumped forward at lunch, losing consciousness. When he came to, he had trouble forming words.

There was a middle-age man whose stroke was unforgettable. When Dr. Warach saw his initial M.R.I. scan, in his basement office at his home, he cried out in astonishment so loudly his wife ran downstairs. “I have never seen anything so severe,” Dr. Warach said. None of the three arteries that supplied the man’s right hemisphere were getting any blood.

Now the man lay in a coma, twitching on his left side, paralyzed on his right, breathing with the help of a ventilator. If he survived, he would have severe brain damage.

There was Michael Collins, a 49-year-old police officer who had had a stroke in his police car in Takoma Park, Md. Unlike the others, Mr. Collins seemed mostly recovered. The next few days, though, would determine whether he was among the lucky 10 percent of stroke patients who escape unscathed or whether he would always be weaker on his left side. If that happened, Mr. Collins said, he could never return to his job.

“You have to be able to shoot a gun with either hand,” he explained. But as time passed, Mr. Collins continued to be plagued by numbness in his left hand and on the left side of his face. He wanted to return to work — “I’m doing great,” he said this month — but the Police Department insisted that he retire, telling him, he said, “it’s an officer safety issue.”

The rest of the patients in the stroke units at the two hospitals that day were less fortunate: almost certain to live, but also almost certain to end up with brain damage. Some would have to spend time at a rehabilitation center.

On average, said Dr. Brendan E. Conroy, medical director of the stroke recovery program at the National Rehabilitation Hospital, which is attached to the Washington Hospital Center, a third of the Washington hospital’s stroke patients die, a third go home and a third come to him.

Those whose balance is affected typically spend 20 days learning to deal with a walker or a cane; those who are partly blind or paralyzed must learn to care for themselves. Many functions return, Dr. Conroy said, but rehabilitation also means learning to live with a disability.