- RETIREMENT ANNOUNCEMENT

- HOME PAGE

- "MYCHART" the new patient portal

- BELMONT MEDICAL ASSOCIATES

- MOUNT AUBURN HOSPITAL

- EMERGENCIES

- PRACTICE PHILOSOPHY

- MY RESUME

- TELEMEDICINE CONSULTATION

- CONTACT ME

- LAB RESULTS

- ePRESCRIPTIONS

- eREFERRALS

- RECORD RELEASE

- MEDICAL SCRIBE

- PHYSICIAN ASSISTANT (PA)

- Medicare Annual Wellness Visit

- Case management/Social work

- Quality Care Measures

- Emergency closing notice

- FEEDBACK

- Talking to your doctor

- Choosing..... and losing a doctor

- INDEX A - Z

- ALLERGIC REACTIONS

- Alternative Medicine

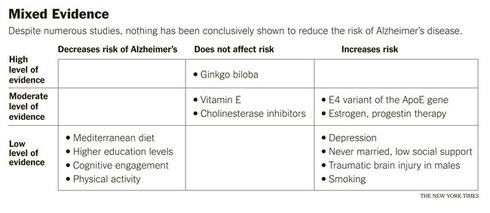

- Alzheimer's Disease

- Bladder Problems

- Blood disorders

- Cancer Concerns

- GENETIC TESTING FOR HEREDITARY CANCER

- Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

- Controversial Concerns

- CPR : Learn and save a life

- CRP : Inflammatory marker

- Diabetes Management

- Dizziness, Vertigo,Tinnitus and Hearing Loss

- EXERCISE

- FEMALE HEALTH

-

GASTROINTESTINAL topics

- Appendicitis

- BRAT diet

- Celiac Disease or Sprue

- Crohn's Disease

- Gastroenterologists for Colon Cancer Screening

- Colonoscopy PREP

- Constipation

- Gluten sensitivity, but not celiac disease

- Heartburn and GERD

- Hemorrhoids and Anal fissure

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- NASH : Non Alcoholic Steato Hepatitis

- FEET PROBLEMS

- HEART RELATED topics

-

INFECTIOUS DISEASES

- Antibiotic Resistance

- Cat bites >

- Clostridia difficile infection - the "antibiotic associated germ"

- CORONA VIRUS

- Dengue Fever and Chikungunya Fever

- Food borne illnesses

- Shingles Vaccine

- Hepatitis B

- Hepatitis C

- Herpes

- Influenza

- Helicobacter pylori - the "ulcer germ"

- HIV Screening

- Lyme and other tick borne diseases

- Measles

- Meningitis

- MRSA (Staph infection)

- Norovirus

- Sexually Transmitted Diseases

- Shingles (Herpes Zoster)

- Sinusitis

- West Nile Virus

- Whooping Cough (Pertussis)

- Zika virus and pregnancy

- INSURANCE related topics

- KIDNEY STONES

- LEG CRAMPS

- LIBRARY for patients

- LIFE DECISIONS

- MALE HEALTH

- Medication/Drug side effects

- MEDICAL MARIJUANA

- MENTAL HEALTH

- Miscellaneous Articles

-

NUTRITION - EXERCISE - WEIGHT

- Cholesterol : New guidelines for treatment

- Advice to lower your cholesterol

- Cholesterol : Control

- Cholesterol : Raising your HDL Level

- Exercise

- Food : Making Smart Choices

- Food : Making Poor Choices

- Food : Grape Fruit and Drug Interaction

- Food : Vitamins, Minerals and Supplements

- Omega 3 fatty acids

- Vitamin B12 deficiency

- Vitamin D

- Weight Loss

- ORTHOPEDICS

- PAIN

- PATIENTS' RIGHTS

- SKIN

- SLEEP

- SMOKING

- STROKE

- THYROID

- SUBSTANCE ABUSE

- Travel and Vaccination

- TREMOR

- Warfarin Anticoagulation

- OTHER STUFF FOLLOWS

- Fact or Opinion?

- Hippocratic Oath

- FREE ADVICE.......for what its worth!

- LAUGHTER.....is the best medicine

- Physicians Pet Peeves

- PHOTO ALBUM - its not all work!

- Cape Town, South Africa

- Tribute page

- The 100 Club

- Free Wi-Fi

Alzheimer's Disease

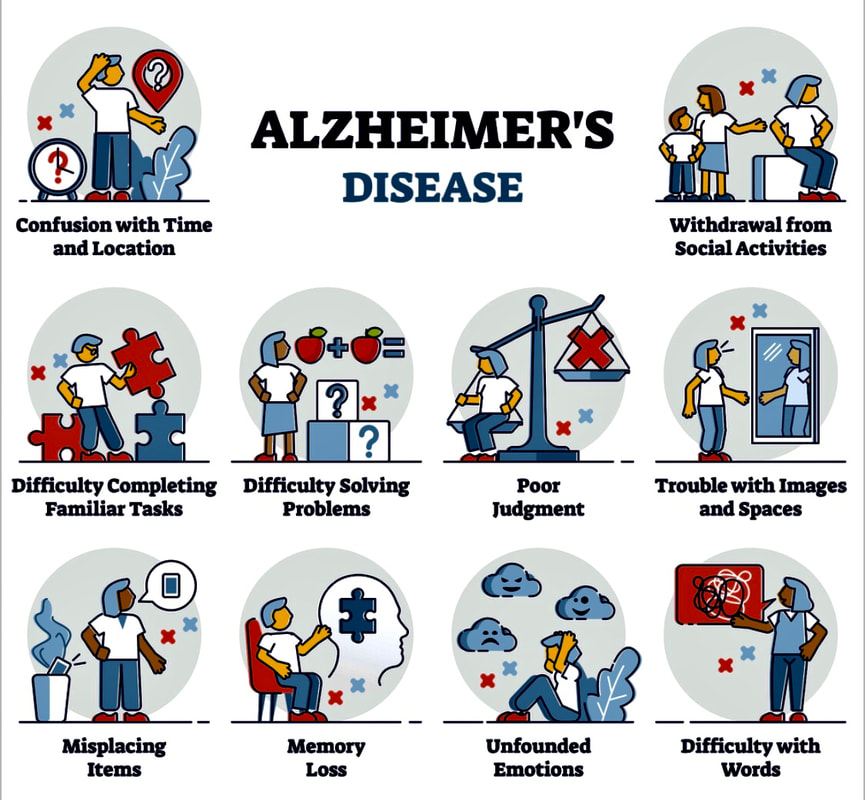

10 warning signs of Alzheimer's:

1. Memory loss. Forgetting recently learned information is one of the most common early signs of dementia. A person begins to forget more often and is unable to recall the information later.

- What's normal? Forgetting names or appointments occasionally.

2. Difficulty performing familiar tasks. People with dementia often find it hard to plan or complete everyday tasks. Individuals may lose track of the steps involved in preparing a meal, placing a telephone call or playing a game.

- What's normal? Occasionally forgetting why you came into a room or what you planned to say.

3. Problems with language. People with Alzheimer’s disease often forget simple words or substitute unusual words, making their speech or writing hard to understand. They may be unable to find the toothbrush, for example, and instead ask for "that thing for my mouth.”

- What's normal? Sometimes having trouble finding the right word.

4. Disorientation to time and place. People with Alzheimer’s disease can become lost in their own neighborhood, forget where they are and how they got there, and not know how to get back home.

- What's normal? Forgetting the day of the week or where you were going.

5. Poor or decreased judgment. Those with Alzheimer’s may dress inappropriately, wearing several layers on a warm day or little clothing in the cold. They may show poor judgment, like giving away large sums of money to telemarketers.

- What's normal? Making a questionable or debatable decision from time to time.

6. Problems with abstract thinking. Someone with Alzheimer’s disease may have unusual difficulty performing complex mental tasks, like forgetting what numbers are for and how they should be used.

- What's normal? Finding it challenging to balance a checkbook.

7. Misplacing things. A person with Alzheimer’s disease may put things in unusual places: an iron in the freezer or a wristwatch in the sugar bowl.

- What's normal? Misplacing keys or a wallet temporarily.

8. Changes in mood or behavior. Someone with Alzheimer’s disease may show rapid mood swings – from calm to tears to anger – for no apparent reason.

- What's normal? Occasionally feeling sad or moody.

9. Changes in personality. The personalities of people with dementia can change dramatically. They may become extremely confused, suspicious, fearful or dependent on a family member.

- What's normal? People’s personalities do change somewhat with age.

10. Loss of initiative. A person with Alzheimer’s disease may become very passive, sitting in front of the TV for hours, sleeping more than usual or not wanting to do usual activities.

- What's normal? Sometimes feeling weary of work or social obligations.

Is It Ordinary Memory Loss, or Alzheimer’s Disease?

By Jane E. Brody : NY Times : May 18, 2015

Soon after her 65th birthday, a close friend became increasingly worried about her memory, wondering if she could have the beginnings of dementia.

Although she seemed to have no more difficulty than the rest of us her age in remembering events, names and places, her physician suggested that, given her level of concern, she should have things checked out.

So she consulted a specialist at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York and had a full-blown neuropsychological assessment — two days of tests of her cognitive abilities. The dozen measures included I.Q. and memory scales, auditory learning and animal naming tests, an oral word association test, a connect-the-dots trail-making test, and a test of her ability to copy complex figures.

The result: reassurance and relief. Everything was in the normal range for her age, and she registered as superior on the ability to perform tasks and solve problems.

Fears about memory issues, commonplace among those of us who often misplace our cellphones and mix up the names of our children, are likely to skyrocket as baby boomers move into their 70s, 80s and beyond.

Many may be unwilling to wait to have their memories tested until symptoms develop that could herald encroaching dementia or Alzheimer’s disease, like finding one’s glasses in the refrigerator, getting lost on a familiar route or being unable to follow directions or normal conversation.

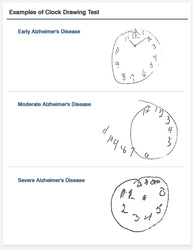

But nor do people have to endure the extensive assessment my friend had. Simple tests done in eight to 12 minutes in a doctor’s office can determine whether memory issues are normal for one’s age or are problematic and warrant a more thorough evaluation. The tests can be administered annually, if necessary, to detect worrisome changes.

However, according to researchers at the University of Michigan, more than half of older adults with signs of memory loss never see a doctor about it. Although there is still no certain way to prevent or forestall age-related cognitive disease, knowing that someone has serious memory problems can alert family members and friends to a need for changes in the person’s living arrangements that can be health- or even lifesaving.

“Early evaluation and identification of people with dementia may help them receive care earlier,” said Dr. Vikas Kotagal, the senior author of the Michigan study. “It can help families make plans for care, help with day-to-day tasks, including medication administration, and watch for future problems that can occur.”

Long the most popular screening test for memory disorders used by primary care doctors is the Mini-Mental State Exam, or MMSE, an eight-minute test in use since 1975. But neurologists say it is less discerning than the slightly longer Montreal Cognitive Assessment, or MoCA, introduced in 1996.

Both tests measure orientation to time, date and place; attention and concentration; ability to calculate; memory; language; and conceptual thinking. But while the MMSE is considered adequate for routine testing of cognitive function by the family doctor, its score can be skewed by a person’s level of education, cultural background, a learning or speech disorder, and language fluency. And according to Dr. Roy Hamilton, a neurologist at the University of Pennsylvania, this test is not sensitive enough to detect signs of mild cognitive impairment.

Furthermore, the MMSE doesn’t test for problems with executive function, defined as the ability to organize, plan and perform tasks efficiently to reach a particular goal.

“Executive function is typically the first area to suffer if you develop cognitive impairment,” Dr. Sam Gandy, the director of the Mount Sinai Center for Cognitive Health and of the N.F.L.’s neurological care program, reported last month in the School of Medicine’s newsletter, Focus on Healthy Aging. “Translated into everyday life, it’s executive function that enables us to carry out activities of daily living, such as dressing and preparing meals.”

The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, which takes 10 to 12 minutes, is more difficult and can pick up problems the MMSE might miss, Dr. Hamilton has noted. It is also more sensitive, better able to discriminate between normal cognitive function and mild impairment or dementia. Still, many memory clinics and neurologists use both tests, along with others like those taken by my friend.

The Montreal test has 11 sections and a possible total score of 30 (25 or better is considered normal). It includes an executive function test called alternating trail-making, in which lines must be drawn from numbers to letters in correct order, 1 to A, 2 to B, and so forth.

Measuring a person’s ability to follow verbal commands includes counting backward from 100 by sevens. To assess abstract thinking, the test asks a person to find common features between two words in each of three pairs. Verbal fluency, a vocabulary test, requires producing 11 or more words that start with a certain letter of the alphabet.

Copying a drawing of a cube and drawing a clock accurately assess so-called visuoconstructional skills, and memory is checked by having the person try to recall five words that were read aloud earlier in the test.

Taking such a test can be quite stressful, although allowances are made for nervousness. But practicing by taking the test in advance of an evaluation can skew the results and hurt the person taking it in the long run.

The MoCA test has proved valid for assessing people who are not demented but could be at risk for developing progressive cognitive decline.

Keep in mind, however, that neither the MMSE nor MoCA are definitive. Rather, they can indicate the need for a more extensive exam like the one my friend had.

Also, it helps to know when not to worry about memory problems. Dr. Kirk R. Daffner, the director of the Center for Brain-Mind Medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, lists six “normal” memory problems that should not cause concern: a tendency to forget facts or events over time, absent-mindedness, a temporary block in retrieving a memory, recalling something accurately only in part, having a memory distorted by the power of suggestion (the recalled memory may never have happened), and having a memory influenced by bias, experiences or mood.

Questions for Your Doctor What to Ask About Alzheimer's Disease

By Irene M. Wielawski : NY Times Article : August 29, 2007

Confronting a new diagnosis can be frightening — and because research changes so often, confusing. Here are some questions you may not think to ask your doctor, along with notes on why they’re important.

How can we be sure my symptoms aren’t the result of a stroke, mental illness or another treatable condition?

What stage of Alzheimer’s disease am I in? What comes next? Clinicians classify the progressive deterioration of brain function in Alzheimer’s disease into seven stages. By the last stage, patients require round-the-clock care. In the first, second and third stages of this slow moving illness, symptoms are minimal, and many patients work and live independently.

What can I do to preserve my health and mental abilities for as long as possible? Although there are no treatments to halt or cure Alzheimer’s disease, recent studies have suggested that exercise, a healthy diet and mental stimulation may delay the onset of disabling symptoms.

What physical symptoms should I anticipate? Patients typically complain of problems with memory and organizational ability, but Alzheimer’s disease also attacks the brain’s motor centers, resulting in problems with balance, coordination, bladder and bowel control, and certain reflexes, including the ability to swallow. Patients and their caregivers should prepare for mental and physical disabilities.

Should I undergo brain neuroimaging? Imaging of the brain occasionally can help differentiate Alzheimer’s disease from other potential causes of dementia in new patients; however, imaging is rarely useful for determining the severity of the disease.

My children are worried about inheriting this illness. Would it be useful for our family to undergo genetic testing? Scientists have identified several gene mutations associated with an increased risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease, but the predictive value of each mutation is low. As a result, genetic testing is useful only for individuals who have several close relatives suffering from early-onset forms of the disease.

What drugs are currently available for Alzheimer’s disease, and how well do they work? Two types of drugs are currently prescribed for treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Cholinesterase inhibitors, such as donepezil and galantamine, regulate acetylcholine, a neurotransmitter influential in learning and memory. The only NMDA receptor antagonist on the market, memantine, tamps down excessive brain activity. Both types have been shown to delay brain deterioration for a brief period (6 to 12 months) in about half the people treated.

My family is afraid to let me drive. Would you refer me for a driving evaluation so we can have an objective opinion of my ability? Driving is often a focal point of familial controversy. Diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease doesn’t always require that a patient immediately stop driving. An objective medical evaluation can be helpful in clarifying the extent of a new patient’s disability.

What can I do to make things easier on my family? Because Alzheimer’s erodes cognitive ability, it’s important for patients to plan for a day when they can no longer take care of their affairs. Newly diagnosed patients should execute medical and durable powers of attorney that authorize spouses or other family members to deal with banks, insurance companies, doctors and others on their behalf.

There is no definitive test for Alzheimer’s disease, and it can be misdiagnosed in patients suffering depression, memory deficits because of normal aging, arterial blockages or even certain vitamin deficiencies. Doctors generally rule out other possibilities, then apply criteria developed by various medical organizations to arrive at the diagnosis.

Cracking the Code to the Memory Vault

By Jane E. Brody : New York Times Article : December 4, 2007

I bless the day 3M invented Post-It notes. I don’t think I could survive without them. They decorate my computer, reminding me how to do things like create a folder, undo an error or save an attachment without opening it. They adorn my refrigerator and kitchen cabinets to help me remember what to buy, what to order and when I have to be where.

Also on my refrigerator is a cartoon by Arnie Levin in The New Yorker showing two elephants. One, covered with notes, says to the other, “As I get older, I find I rely more and more on these sticky notes to remind me.”

I have notes that say, “Take Lunch,” “Take Phone,” “Turn Off Computer!” lest I forget such important tasks when I leave home.

Why do I still remember the symbols for all the elements known when I took chemistry 48 years ago, but don’t recall what I wrote about yesterday?

When I complained to my 30-something son that I cannot seem to remember anything unless I write it down and stare at it, he said reassuringly, “Mom, by now you’ve got so much crammed into your head, something is bound to fall out!”

And I know I’m not alone among the over-50 generation. A good friend, two and a half years my senior, endured a six-hour battery of neuropsychological tests because she feared encroaching Alzheimer’s disease. (She got an all clear.) We tease each other about always having to go everywhere together, because we each supply half a memory.

If my husband precedes me in death, my memory of the movies and plays I have seen will die with him. Though eight years my senior, he remembers not only what we have seen, but also where and when.

And why don’t I have a politician’s memory for names? As a reporter for The Minneapolis Tribune in 1965, I covered Hubert H. Humphrey’s first visit to his home state as vice president. Everywhere he went, he greeted people by name and asked about their relatives, also by name. And seven hours after being introduced to a half-dozen reporters, he said before departing for Washington: “Goodbye, Miss Brody. I’ll give your regards to Brooklyn next time I’m there.”

When I’m introduced to a new person, the name is gone from my memory before the handshake is over. Probably it was never there to start with, because I’ve known since childhood that I’m a visual, not an aural, learner. If a new acquaintance has no name tag, a verbally stated name goes in one ear and out the other, bypassing my brain’s memory cells.

All through school, I took voluminous notes and underlined every important sentence in my textbooks. During exams, I could visualize the answers on their respective pages. No matter how hard I tried to learn just by listening, the lesson was out of my head by the time I left the classroom.

Blocking and Blanking

Few of us escape the experience of walking from one room to another and not remembering why or what for. Chances are an extraneous thought in that brief trek blocked out its original purpose. But if you go back to the first room, you nearly always recall your mission. It’s annoying, but not really embarrassing, not like blanking on the name of someone you know well.

Like the time I tried to introduce my stepmother of 25 years to another guest at my party and could not for the life of me think of her first name. “Sandra, I’d like you to meet my motherhuh, huh, Mrs. Brody,” I finally blurted out.

In “Carved in Sand” (HarperCollins), an enlightening and rather reassuring new book on fading memory in midlife, the writer Cathryn Jakobson Ramin speaks of “‘blocking’ (or ‘blanking’) when names will not come to mind and words dart in and out of consciousness.” Ms. Ramin, like me, has often been stopped cold in the midst of writing when unable to think of what she knows is the perfect word.

Her research found that “word-retrieval failures occur not because of the loss of relevant memories, but because irrelevant ones are activated.”

Daniel L. Schacter, a psychologist and memory expert at Harvard and the author of “The Seven Sins of Memory” (Houghton Mifflin), notes that the concept of blocking exists in 51 languages and that 45 of them have a specific name for it. In English, it’s called “tip of the tongue,” lapses that become increasingly common and challenging from midlife onward.

“People can produce virtually everything they know about a person or everything they know about a word, except its label,” Dr. Schacter wrote. My friends and I often find ourselves talking about “you know who” and “thingamajigs.”

How I Cope

Mnemonics can be useful, if you can remember them and what they stand for. When my 7-year-old grandson told me to “never eat Shredded Wheat,” which he knows I like, he laughed and said it helped him remember “north, east, south and west.” To remember what I have to do or buy when I can’t write it down, I try to concoct an unforgettable mnemonic like “Babies Are Little Children” for bananas, apples, lettuce and cereal.

Whenever possible, I associate a new name with a tangible object: “Cucumber” for Kirby, the lifeguard at the Y; “ravioli” for Ralph, who sits at the desk; and “sherry” for Sherry, the locker room attendant.

For fellow Y members, after learning a name, I use it every chance I get: “Hi, Jeanette,” “So long, Sue, have a nice day,” “Cynthia, you’re early today,” and “Aviva, how’s your new job?”

And I continue to say their names aloud even after I think that they are etched in stone in my memory.

At a dinner where I’m to be seated with a table of strangers, I check the list of others at the table in advance to help me remember their names when we are introduced. And for groups that meet infrequently, I campaign for name tags. No one should have to remember the names of people she sees once or twice a year.

Though I have long worked in a state of organized chaos (I know where everything is, as long as no one moves it), I needed a better system as I advanced in years. Now, every potentially important piece of paper must go in a labeled file (even if that file has only one thing in it), and the files stored alphabetically in a labeled drawer or box, lest they never be found again.

Also, I resist all urges to reorganize my files — or my clothes, shoes, groceries or tools —because I seem to remember only the first place I put something. Move it to a new location, and it is lost until and unless I stumble upon it accidentally.

Finally, to remember when things must be done like move the car, pick up the grandchildren and turn off the oven, I invested heavily in good kitchen timers and scattered them about the house. The best I have found is made by West Bend. The model number is 40005X, and it runs for a very long time on one AAA battery.

Mental Reserves Keep Brains Agile

By Jane E. Brody : NY Times Article : December 11, 2007

My husband, at 74, is the baby of his bridge group, which includes a woman of 85 and a man of 89. This challenging game demands an excellent memory (for bids, cards played, rules and so on) and an ability to think strategically and read subtle psychological cues. Never having had a head for cards, I continue to be amazed by the mental agility of these septua- and octogenarians.

The brain, like every other part of the body, changes with age, and those changes can impede clear thinking and memory. Yet many older people seem to remain sharp as a tack well into their 80s and beyond. Although their pace may have slowed, they continue to work, travel, attend plays and concerts, play cards and board games, study foreign languages, design buildings, work with computers, write books, do puzzles, knit or perform other mentally challenging tasks that can befuddle people much younger.

But when these sharp old folks die, autopsy studies often reveal extensive brain abnormalities like those in patients with Alzheimer’s. Dr. Nikolaos Scarmeas and Yaakov Stern at Columbia University Medical Center recall that in 1988, a study of “cognitively normal elderly women” showed that they had “advanced Alzheimer’s disease pathology in their brains at death.” Later studies indicated that up to two-thirds of people with autopsy findings of Alzheimer’s disease were cognitively intact when they died.

“Something must account for the disjunction between the degree of brain damage and its outcome,” the Columbia scientists deduced. And that something, they and others suggest, is “cognitive reserve.”

Cognitive reserve, in this theory, refers to the brain’s ability to develop and maintain extra neurons and connections between them via axons and dendrites. Later in life, these connections may help compensate for the rise in dementia-related brain pathology that accompanies normal aging.

Exercise: Mental ...

As Cathryn Jakobson Ramin relates in her new book, “Carved in Sand: When Attention Fails and Memory Fades in Midlife” (HarperCollins), the brains of animals exposed to greater physical and mental stimulation appear to have a greater number of healthy nerve cells and connections between them. Scientists theorize that this excess of working neurons and interconnections compensates for damaged ones to ward off dementia.

Observing this, Dr. Stern, a neuropsychologist, and others set out to determine how people can develop cognitive reserve. They have learned thus far that there is no “quick fix” for the aging brain, and little evidence that any one supplement or program or piece of equipment can protect or enhance brain function — advertisements for products like ginkgo biloba to the contrary.

Nonetheless, well-designed studies suggest several ways to improve the brain’s viability. Though best to start early to build up cognitive reserve, there is evidence that this account can be replenished even late in life.

Cognitive reserve is greater in people who complete higher levels of education. The more intellectual challenges to the brain early in life, the more neurons and connections the brain is likely to develop and perhaps maintain into later years. Several studies of normal aging have found that higher levels of educational attainment were associated with slower cognitive and functional decline.

Dr. Scarmeas and Dr. Stern suggest that cognitive reserve probably reflects an interconnection between genetic intelligence and education, since more intelligent people are likely to complete higher levels of education.

But brain stimulation does not have to stop with the diploma. Better-educated people may go on to choose more intellectually demanding occupations and pursue brain-stimulating hobbies, resulting in a form of lifelong learning. In researching her book, Ms. Ramin said she found that novelty was crucial to providing stimulation for the aging brain.

“If you’re doing the same thing over and over again, without introducing new mental challenges, it won’t be beneficial,” she said in an interview. Thus, as with muscles, it’s “use it or lose it.” The brain requires continued stresses to maintain or enhance its strength.

So if you knit, challenge yourself with more than simply stitched scarves. Try a complicated pattern or garment. Listening to opera is lovely, but learning the libretto (available in most libraries) stimulates more neurons. In my 60s I took up knitting and crocheting and am now learning Spanish. My husband is a fanatical puzzle-doer who recently added Sudoku to the crosswords and double-crostics he carries around with him.

In 2001, Dr. Scarmeas published a long-term study of cognitively healthy elderly New Yorkers. On average, those who pursued the most leisure activities of an intellectual or social nature had a 38 percent lower risk of developing dementia. The more activities, the lower the risk.

Long-term studies in other countries, including Sweden and China, have also found that continued social interactions helped protect against dementia. The more extensive an older person’s social network, the better the brain is likely to work, the research suggests. Especially helpful are productive or mentally stimulating activities pursued with other people, like community gardening, taking classes, volunteering or participating in a play-reading group.

... and Physical

Perhaps the most direct route to a fit mind is through a fit body. As Sandra Aamodt, editor of Nature Neuroscience, and Sam Wang, a neuroscientist at Princeton University, recently stated on The New York Times’s Op-Ed page, physical exercise “improves what scientists call ‘executive function,’ the set of abilities that allows you to select behavior that’s appropriate to the situation, inhibit inappropriate behavior and focus on the job at hand in spite of distractions. Executive function includes basic functions like processing speed, response speed and working memory, the type used to remember a house number while walking from the car to a party.”

Although executive function typically declines with advancing years, “elderly people who have been athletic all their lives have much better executive function than sedentary people of the same age,” Dr. Aamodt and Dr. Wang reported.

And not just because cognitively healthy people tend to be more active. When inactive people in their 70s get more exercise, executive function improves, an analysis of 18 studies showed. Just walking fast for 30 to 60 minutes several times a week can help. And compared with those who are sedentary, people who exercise regularly in midlife are one-third as likely to develop Alzheimer’s in their 70s. Even those who start exercising in their 60s cut their risk of dementia in half.

Exercise may help by improving blood flow (and hence oxygen and nutrients) to the brain, reducing the risk of ministrokes and clogged blood vessels, and stimulating growth factors that promote the formation of new neurons and neuronal connections.

When Lapses Are Not Just Signs of Aging

By Jane E. Brody : NY Times : September 5, 2011

Who hasn’t struggled occasionally to come up with a desired word or the name of someone near and dear? I was still in my 40s when one day the first name of my stepmother of 30-odd years suddenly escaped me. I had to introduce her to a friend as “Mrs. Brody.”

But for millions of Americans with a neurological condition called mild cognitive impairment, lapses in word-finding and name recall are often common, along with other challenges like remembering appointments, difficulty paying bills or losing one’s train of thought in the middle of a conversation.

Though not as severe as full-blown Alzheimer’s disease or other forms of dementia, mild cognitive impairment is often a portent of these mind-robbing disorders. Dr. Barry Reisberg, professor of psychiatry at New York University School of Medicine, who in 1982 described the seven stages of Alzheimer’s disease, calls the milder disorder Stage 3, a condition of subtle deficits in cognitive function that nonetheless allow most people to live independently and participate in normal activities.

One of Dr. Reisberg’s patients is a typical example. In the two and a half years since her diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment at age 78, the woman learned to use the subway, piloted an airplane for the first time (with an instructor) and continued to enjoy vacations and family visits. But she also paid some of the same bills twice and spends hours shuffling papers.

Dr. Ronald C. Petersen, a neurologist at the Mayo Clinic College of Medicine in Rochester, Minn., described mild cognitive impairment as “an intermediate state of cognitive function,” somewhere between the changes seen normally as people age and the severe deficits associated with dementia.

While most people experience a gradual cognitive decline as they get older (only about one in 100 lives long without cognitive loss), others experience more extreme changes in cognitive function, the neurologist wrote in The New England Journal of Medicine in June. In population-based studies, mild cognitive impairment has been found in 10 percent to 20 percent of people older than 65, he noted.

Dr. Petersen described two “subtypes” of the condition, amnestic and nonamnestic, that have different trajectories. The more common amnestic type is associated with significant memoryproblems, and within 5 to 10 years usually — but not always — progresses to full-blown Alzheimer’s disease, he said in an interview.

“Subtle forgetfulness, such as misplacing objects and having difficulty recalling words, can plague persons as they age and probably represents normal aging,” he wrote. “The memory lossthat occurs in persons with amnestic mild cognitive impairment is more prominent. Typically, they start to forget important information that they previously would have remembered easily, such as appointments, telephone conversations or recent events that would normally interest them,” like the outcome of a ballgame would a sports fan.

The forgetfulness is often obvious to those who are affected and to people close to them, but not to casual observers.

The less common nonamnestic type, which is associated with difficulty making decisions, finding the right words, multitasking, visual-spatial tasks and navigating, can be a forerunner of other kinds of dementia, Dr. Petersen said.

In general, Dr. Reisberg said, “mild cognitive impairment lasts about seven years before it begins to interfere with the activities of daily life.”

The Correct Diagnosis

Distinguishing mild cognitive impairment from the effects of normal aging can be challenging. Typically, new patients take a short test of mental status, provide a thorough medical history and are checked for conditions that may be reversible causes of impaired cognition. Problems like depression, medication side effects, vitamin B12 deficiency or an underactive thyroid can mimic the symptoms of mild cognitive impairment.

Other tests, like an M.R.I. or CT scan of the brain, can look for evidence of a stroke, brain tumor or leaky blood vessel that may be impairing brain function.

It is natural, Dr. Petersen said, for patients and their families to want to know whether and how quickly the disorder might progress. While patients decline by about 10 percent each year, on average, certain factors are associated with more rapid progression. Among these are the presence of a gene called APOE e4, more common among patients with Alzheimer’s disease; a reduced hippocampus, a region of the brain important to memory; and a low metabolic rate in the temporal and parietal regions of the brain.

Amyloid plaques in the brain, while a hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease and a predictor of progression, have also been found at autopsy in people with perfectly normal cognitive function.

Preserving Cognitive Function

Despite a number of clinical trials that tested various medications, no drug to treat mild cognitive impairment has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration. But experts like Dr. Reisberg and Dr. Petersen suggest several approaches that may slow the decline in cognitive function.

Although studies did not show that medications like donepezil (brand name Aricept) and memantine (Namenda), both used to treat Alzheimer’s disease, do not change the ultimate course of mild cognitive impairment, Dr. Reisberg said they can be useful temporary treatments that may stabilize patients for a few years.

Although the drugs are not approved for this condition, licensed physicians can prescribe approved medications “off label.” “Clinicians have to work with what we have,” Dr. Reisberg said.

There are people who think they are having memory problems, but tests do not show anything definitive. Some may be in Stage 1 of Alzheimer’s disease, Dr. Reisberg said, and perhaps could benefit from early treatment with the drugs.

It is also important to reduce cardiovascular risk factors like smoking, elevated cholesterol and high blood pressure; keep blood sugar at normal levels; minimize stress (which in animal studies can cause the hippocampus to shrink); and avoid anticholinergic drugs that can interfere with brain chemicals important to memory. These include Demerol to treat pain, Detrol to treat a leaky bladder, tricyclic antidepressants, Valium, and over-the-counter medications with Benadryl (diphenhydramine), like Tylenol PM, Dr. Petersen said.

Some cognitive rehabilitation exercises, like computer games that enhance focus, may be helpful, Dr. Petersen said, but there have been few good studies to demonstrate a benefit. Compensatory techniques, like taking notes, creating mnemonics and making structured schedules, can be useful aids, he added.

But most promising is regular physical exercise, which in animal studies was found to reduce the accumulation of amyloid in the brain. An Australian study in patients with memory problems showed that brisk walking for 150 minutes a week improved cognitive function.

What's Good for the Heart Is Good for the Head

By Jane E. Brody : NY Times Article : March 22, 2005

For decades I've been pleading with my readers to adopt healthy habits to prevent heart disease and possibly some cancers. Now there's another organ, the brain, that these measures may protect.

Growing, scientifically sound evidence suggests that people can delay and perhaps even prevent Alzheimer's disease by taking steps like eating low-fat diets rich in antioxidants, maintaining normal weight, exercising regularly and avoiding bad habits like smoking and excessive drinking.

Several other practices - including remaining socially connected and keeping the brain stimulated by reading, doing puzzles and learning new things - also appear to protect the brain against dementia.

Achieving such protection is no minor matter. Nearly half of the people who live past 85 develop this devastating disease that ultimately divorces them from reality and those who love them. With 77 million baby boomers headed toward advanced age, much can be gained from postponing this most common form of dementia, if not preventing it entirely.

An estimated 4.5 million Americans now have Alzheimer's, and the number has doubled since 1980, as more people reach older and older ages. Alzheimer's already costs Medicare three times as much as any other disease. By 2010, Medicare costs for people with Alzheimer's are expected to rise by more than 50 percent, to $49.3 billion from $31.9 billion in 2000. Now, half of all nursing home costs are related to dementia.

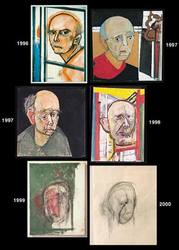

Alzheimer's is a progressive brain disorder that gradually destroys a person's memory and ability to learn, reason, make judgments, communicate and carry out normal activities of daily life.

Two changes in the brain are characteristic: abnormal microscopic structures called amyloid plaques that accumulate outside brain cells and tangles of a protein called tau that form inside brain cells. Because these changes are now seen only in autopsies, coming up with early diagnoses and tests for the disorder is a major challenge.

Early signs may include forgetting recently learned information, performing familiar tasks only with difficulty, misplacing things (putting shoes in the refrigerator, for example), fumbling for the right word for an ordinary object (like a toothbrush) and forgetting where you are or how you got there. Personalities can also change, and patients can become paranoid, suspicious, fearful or extremely confused. Some lose their judgment and suffer from mood swings or loss of initiative.

Built for Durability

The brain is a very forgiving organ. It has a very large reserve capacity and can withstand an extraordinary number of "hits" and bounce back from them. Witness how well some people recover from serious strokes and brain trauma. Likewise, autopsies often reveal considerable brain changes associated with Alzheimer's disease among subjects who showed no symptoms of dementia during their lives.

But when the brain is otherwise compromised, it may not be as able to protect itself against the encroaching damage of Alzheimer's.

So how do measures to prevent heart disease and stroke protect the brain? In an interview, Dr. Laurel Coleman, a geriatric physician in Augusta, Me., and a member of the national board of the Alzheimer's Association, explained that increasing evidence suggested an overlap between vascular disease in the brain and what happens to the brain in people who develop Alzheimer's.

The presence of vascular disease - the kind that can lead to a heart attack or stroke - seems to decrease the brain's ability to fend off the effects of Alzheimer's-related damage and increase a person's chances of showing obvious signs of dementia.

"Some people," Dr. Coleman said, "have pure Alzheimer's disease and some have pure cerebral vascular disease. But most have a mix of the two." The same risk factors that raise a person's chances of having a heart attack or stroke - high cholesterol and blood pressure, excess weight, smoking, lack of exercise - also raise the risk of developing dementia, she explained.

It's not that circulatory disease causes Alzheimer's, she emphasized. But if the brain lacks a healthy flow of blood through vessels relatively free of atherosclerotic plaques, it is less able to fight off the damage associated with dementia.

Likewise, Dr. Coleman acknowledges that genetic factors may raise a person's risk of Alzheimer's. Taking steps to reduce the risk incurred through genes, though, makes good sense. And that is achieved by controlling known risks for vascular disease.

Some large long-term observational studies, including the Nurses' Health Study and the Honolulu-Asia Aging Study, support the link between risk factors for vascular disease and Alzheimer's. For example, an increased risk of Alzheimer's or an accelerated decline in mental functioning was noted in Japanese-American men with untreated high blood pressure, in American nurses and Dutch study participants with Type 2 diabetes (a result of excess weight), in Finns with high cholesterol and high intakes of saturated fats, and in Europeans who smoked.

A study lasting for decades at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm found a sixfold increase in the risk of Alzheimer's in people who were obese and had high blood pressure and high cholesterol.

But the most telling evidence comes from an order of nuns, nearly 700 School Sisters of Notre Dame studied over many years by Dr. David Snowdon. All the nuns in the order by and large have similar eating and exercise habits, and all agreed to allow their brains to be autopsied.

These autopsies confirmed what had been suspected from observational studies: a striking relationship between the presence in the brain of cerebral vascular disease and symptoms caused by damage related to Alzheimer's disease.

The sisters with brain abnormalities characteristic of Alzheimer's were more likely to have shown symptoms of dementia if they also had strokes or clogged brain arteries.

Recipe for Success

In addition to controlling weight and fat intake, consuming foods or supplements rich in omega-3 fatty acids, like fatty fish or supplements of DHA, appears to protect against brain deterioration. Likewise, regular exercise - like walking more than two miles a day - seems to delay the degeneration of nerve cells in the brain.

How you spend your leisure time may also make an important difference. Activities that involve mental and social stimulation, like doing crossword puzzles; playing bridge, checkers or chess; learning a language or new skill; taking up knitting or crocheting; and remaining socially involved have all been associated in various studies with preservation of normal brain function.

When these activities are combined with regular physical activity, the benefit appears to be even greater.

To spread information about such steps, the Alzheimer's Association is conducting "Maintain Your Brain" workshops across the country. Listings are at www.alz.org.

Mice and other rodents have been shown throughout their lives to be able to form new cells in the part of the brain involved in learning and memory if they live in an "enriched" environment.

Can you be any less well developed than a mouse?

Taking On Alzheimer’s

By Stephanie Saul : NY Times Article : June 10, 2007

In the book “Mrs. Frisby and the Rats of NIMH,” a group of lab rats acquire human intelligence through a genetic experiment. Every child recognizes the charming tale as pure fantasy, yet something similar is occurring at a major pharmaceuticals company, Wyeth, where rodents tested in its labs have, indeed, taken on some features of the human brain.

Unlike the fictional rats that learned to read, write and operate machinery, Wyeth’s animals are slow-witted, confused and forgetful because they suffer from the crippling dementia of Alzheimer’s disease, which they acquired from a transplanted human gene.

Something else extraordinary is going on at Wyeth. The company’s scientists not only can give rodents Alzheimer’s — they have also figured out how to take it away. Curing mice is a lot simpler than curing people, but the results are a tantalizing development that offers hope to humans suffering from the disease. The work also advances what Wyeth executives describe as their war on Alzheimer’s.

Wyeth’s team faces a formidable foe. In an industry often criticized as making pricey “me too” drugs that involve minor tweaks to competitors’ products, as well as promoting medicines of marginal value, Wyeth has decided to go full bore against Alzheimer’s, a disease that has defied effective treatment since it was first identified a century ago. The company has dedicated more than 350 scientists exclusively to Alzheimer’s research, and they are working on 23 separate projects for medicines to possibly treat the disease.

About five million people in the United States are living with Alzheimer’s, according to the Alzheimer’s Association, an advocacy group funded by individual donors as well as foundations and major corporations, including drug makers. Without a cure or new treatments, the number of those with the disease could grow to 13.2 million by 2050, the National Institute on Aging estimates.

“I think this is going to be the disease, and maybe one of the biggest health care political issues of my generation,” says Robert Essner, 59, Wyeth’s professorial chief executive. “It’s hard for anyone to envision how to provide health care in the United States if you’re going to have to deal with the burden. You just start to add up the cost, 20 years from now as my generation gets old — it’s phenomenal.”

Mr. Essner will have more than a host of grateful baby boomers awaiting him if Wyeth’s crusade is successful. The company could snare a big financial payoff from what still amounts to a risky bet, one that has already cost Wyeth about $450 million in research funds. But with a treatment that slows progress of the disease possibly selling at more than $20,000 a year, the company’s Alzheimer’s program is one reason that some analysts are voicing renewed enthusiasm about Wyeth’s stock, which had been weighed down for years by costly fen-phen diet drug litigation.

Wyeth is hardly the only company looking for Alzheimer’s treatments. Virtually every large drug maker and a number of smaller biotechnology companies are working to develop Alzheimer’s drugs, with several hundred ideas under study. Several companies are expected to announce results of clinical studies during an international Alzheimer’s meeting that is under way in Washington. “There seems to be a current of excitement,” said Peter Davies, a biochemist at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in the Bronx, who has studied Alzheimer’s for 30 years. Dr. Davies is working with Eli Lilly and Applied NeuroSolutions on a possible course of treatment that is such a secret that he will not say anything about it. “I wouldn’t say it’s a race,” Dr. Davies said, “but this is novel and we want to get a jump on therapeutics.”

The four Alzheimer’s treatments now on the market work by regulating the action of chemical neurotransmitters in the brain. The drugs — Aricept by Eisai and Pfizer, Exelon by Novartis, Razadyne by Johnson & Johnson and Namenda by Forest Laboratories — have shown mixed results treating Alzheimer’s symptoms and do nothing to stop the disease’s progress.

Dr. Todd Golde, professor of neuroscience at the Mayo Clinic, says that the drugs are not very effective, and that consumers’ large expenditures for them — about $1.4 billion in the United States alone last year, according to data from Verispan — reflect the desperation of patients and their families to treat the disease.

“It’s scary if you look at the trials that got these drugs approved,” Dr. Golde said. “The change in mental status was so small, the average caregiver of a patient would have no way of knowing there was any difference.” While there is no evidence that any of the drugs stem the underlying disease, they were approved based on studies showing temporary improvement or stabilization in some patients with Alzheimer’s. The changes can be as minor as a better ability to dress oneself or to take out the trash.

In one study of people taking Namenda and Aricept combined for six months, 60 percent of patients either improved or did not deteriorate. “I would say that physicians do believe these drugs are of benefit to patients with Alzheimer’s,” said Stephen M. Graham, senior director of clinical development at Forest.

Spokesmen for the other companies with Alzheimer’s drugs echoed that assessment in regard to their products, pointing to clinical studies demonstrating that they help patients.

Wyeth is wagering that it can find more promising treatments for a nebulous, stealthy disease that does more than rob people of their health and well-being. It also steals some of their most precious memories.

AT first blush, Robert Essner seems an unlikely flag bearer for a corporate assault on Alzheimer’s. The son of a college professor, Mr. Essner studied humanities as an undergraduate and in graduate school, intending to teach college history. But after he graduated from the University of Chicago in 1971 with a master’s degree in history, he soon realized that jobs in his field were scarce. He says he stumbled into pharmaceuticals by answering an ad in The Wall Street Journal.

Today, he is on the leading edge of a generation that is facing a huge emotional and financial burden from a disease that leaves victims requiring full-time nursing care. He is urging a national mobilization against what he describes as a looming Alzheimer’s “epidemic.”

Mr. Essner often speaks publicly about the disease, stepping outside his role as corporate chief and into the public policy arena. Last month, he testified at a Senate hearing, recommending that the NationalInstitutes of Health double its current annual funding of $643 million for Alzheimer’s research.

Seated recently at a conference table at the company’s headquarters on pastoral property near Madison, N.J., Mr. Essner said he has taken to the podium because he thinks Alzheimer’s should garner the same attention that AIDS received during the 1980s and 1990s, when a coalition of government and industry worked feverishly to find treatments.

He says he is concerned as much about the disease’s dehumanizing effects as he is about its costs. “You see mothers who don’t recognize their daughters,” he says.

Mr. Essner also speaks from experience. While he requested that details be kept private, he confides that a relative has been caught in the disease’s maw. In fact, Mr. Essner is just one of several senior managers involved in the Alzheimer’s drug discovery program at Wyeth whose families have been affected by the disease.

Among the others is Menelas Pangalos, the company’s vice president for neuroscience research and a biochemist. He remembers visiting his grandmother in Greece while she was in the throes of the disease. While people may expect the elderly to lose their memories, Dr. Pangalos says that this is a false assumption that has gained traction only because Alzhiemer’s is so prevalent.

“The problem is that it’s so common,” he said in an interview at Wyeth’s research laboratory near Princeton, N.J., where much of its Alzheimer’s work is conducted. “You assume it’s normal and it’s natural, but it’s not.”

MR. Essner understands history well enough to recognize that big scientific breakthroughs generally accrue to those willing to take a chance. With the high failure rates in drug development, it is unlikely that any single compound now under study will make it to the market. But Mr. Essner says he believes that with so many drugs under study, at least one is likely to succeed.

Wyeth announced last month that it was moving early into advanced human trials of one experimental treatment, a biological product that many scientists view as the most promising new product under study for Alzheimer’s. Wyeth made a presentation about its Alzheimer’s work the centerpiece of the company’s annual shareholders meeting in April, as well as its annual report, which included the stories of seven Alzheimer’s sufferers.

Among those chronicled in the Wyeth accounts was Gilbert Brown, 80, a retired auto parts salesman for Sears in New Jersey. His son, Michael S. Brown, noticed changes in his father several years ago.

“We would talk on the telephone several times a week and he would sometimes say things that didn’t make sense,” said the younger Mr. Brown, who runs a state-funded program that assists low-income students at Montclair State University in Montclair, N.J. At one point, in a subtle but sure sign that something was amiss, Mr. Brown told his son in 2004 that he had lost his checkbook and insisted that he was going to Kmart for a new one.

About three years ago, his father’s gradual decline prompted the younger Mr. Brown, 59, to move him into his home in Irvington, N.J. Today, the elder Mr. Brown can no longer carry on a conversation, dress himself or shave. In fact, he cannot remember the word for shaving. Yet the elder Mr. Brown can still play church hymns on the organ, remembering old favorites like “Rock of Ages” and others that he regularly performs at a senior program. But his son struggles each morning to help his father shower and dress.

“It really hurts,” the younger Mr. Brown says. “He is a very intelligent man. He was the kind of person that his family, my mom’s family, would depend upon to do anything, conduct any business. Then to go from that to not being able to do anything.”

Mr. Brown took Aricept, one of the four Alzheimer’s drugs currently available, until his insurance company said his disease had progressed too far and he was no longer eligible.

“You don’t know what the progression of the deterioration is, so it’s hard to tell if the medicine is helping or not,” Michael Brown says.

A paucity of effective Alzheimer’s treatments reflects how difficult it remains for scientists, doctors and other medical researchers to understand and combat brain disease. Alzheimer’s research began about a century ago, when the Bavarian psychiatrist Alois Alzheimer first diagnosed a 51-year-old patient suffering from dementia, delirium and hallucinations.

The patient, whom Dr. Alzheimer called Auguste D., entered the Frankfurt asylum in 1901. The doctor’s notes on her condition reveal that she was unable to answer simple questions. “At lunch, she eats cauliflower and pork,” the notes say. “Asked what she is eating, she answers, ‘spinach.’ ” Mrs. D. complained to her doctor: “I have lost myself.”

Mrs. D. died five years later, and an autopsy revealed abnormalities in her brain, including the presence of sticky plaque and tangled fibers in nerves. The condition that Dr. Alzheimer described in Mrs. D. was later named after him. While the exact cause of the disease is still unknown, researchers believe that genetic factors play a role and that heavy plaque deposits like those Dr. Alzheimer discovered in Mrs. D.’s brain may contribute to tissue deterioration — leading to memory and recognition loss, linguistic problems and degraded motor skills. But scientists continue to debate whether plaque is a symptom or a cause of Alzheimer’s.

With more and more people living into their 80s and 90s, Alzheimer’s is more common today than it was 100 years ago. Estimates of its frequency vary, but it strikes one out of every 5 people between ages 75 and 84 and 42 percent of those over age 85, according to the Alzheimer’s Association. The organization estimates the current direct and indirect costs of the disease at nearly $150 billion a year, a figure that includes medical and nursing home costs as well as lost job productivity for family members who serve as caregivers. Two drug companies that have progressed to late-stage tests of Alzheimer’s treatments are Neurochem and Myriad Genetics. Neurochem says it may disclose results of its late-stage trial this month. Its drug, Alzhemed, aims at the plaque.

Myriad Genetics’ product, Flurizan, is similar to an anti-inflammatory drug, and it may lower the production of the protein found in plaque. Dr. Golde of the Mayo Clinic was involved in developing the compound.

The National Institutes of Health, the primary federal agency that oversees and helps fund biomedical research, is currently supporting 22 studies involving Alzheimer’s.

John Hardy, a neurogeneticist at the National Institute on Aging, a branch of the National Institutes of Health, says some of the ideas under study as Alzheimer’s treatments have little chance of success. “There’s some pretty wacky things that people try because we’re desperate,” he says.

Dr. Hardy helped to develop a leading theory, known as the “amyloid cascade,” about the biological process that results in Alzheimer’s. The hypothesis holds that Alzheimer’s brain plaque, which contains a protein called beta amyloid, causes symptoms of the disease. According to the theory, plaque develops when something goes awry in the breakdown of a substance called an amyloid precursor protein, or A.P.P.

Scientists came to believe that A.P.P. had something to do with Alzheimer’s by analyzing the genes of Alzheimer’s patients. They also discovered that people with Down syndrome — a group that commonly develops Alzheimer’s-like symptoms — are born with extra A.P.P. And mutations in A.P.P. genes are among the genetic abnormalities found in families with a hereditary form of early-onset Alzheimer’s.

A.P.P. exists in many human cells. It is normally broken down in the body without incident. But scientists believe that in Alzheimer’s patients, enzymes interfere with the breakdown, causing A.P.P. to glob together and form the sticky, toxic beta-amyloid plaque that interferes with activities in the brain.

Among the many companies going after Alzheimer’s, Wyeth is regarded as a leader. Wyeth’s biggest Alzheimer’s bet, in partnership with Elan Pharmaceuticals, involves biological products that would actually slow or reverse the progress of the disease by attacking beta-amyloid. While most researchers believe that the accumulation of beta-amyloid in the brain is the instigating factor of Alzheimer’s, that theory is not without its critics.

Dr. Davies of Einstein, who also directs an Alzheimer’s research center at North Shore-Long Island Jewish Health System, says he believes that plaque is a symptom of the disease rather than a cause. He questions whether eliminating plaque will help those with Alzheimer’s. “It’s like trying to clear up scar tissue and expecting things to get better,” he says.

He subscribes to an alternative theory that focuses on tau, a protein found in the tangled nerve fibers in the brain of Alzheimer’s patients, as the real culprit. His interests also frame a larger divide in the Alzheimer’s world. Those who embrace the beta-amyloid protein theory are nicknamed “Baptists.” Those who finger tau as the villain are called “Tauists.” The two sides recently have moved closer together, more willing to say that beta-amyloid and tau may be working together in Alzheimer’s.

If the two camps continue to merge, it may mean that in the long run Alzheimer’s patients will be treated with more than one drug, the way multipronged treatment regimens are used for cardiovascular problems.

Wyeth itself is keeping a research foot in both treatment camps, on the theory that it is better not to place all its bets on one disease pathway. It is working on compounds aiming at tau, as well as brain enzymes that have been implicated in Alzheimer’s. Its partnership with Elan began in 2000, when several key Wyeth scientists came to Mr. Essner, describing Elan’s work and asking him to sign off on a partnership.

“I asked, ‘What’s the probability of success?’ ” Mr. Essner recalls, laughing. “The first guy said 30 percent. I said: ‘Really? 30 percent, that’s very high.’ He said, ‘Well maybe 10 percent,’ then finally, ‘I have no idea.’ ”

But Mr. Essner says that it was hard to apply a financial calculus to such an undertaking. “I really came away with the impression that their passion for this was so great, that if I had said no, I would have had a mutiny,” he says.

In a development that illustrates the vicissitudes of drug development, the Wyeth-Elan partnership suffered a major setback in 2002, when the first human trial of an Alzheimer’s vaccine, called AN-1792, had to be halted. About 18 patients, or 6 percent of those enrolled, suffered inflammation in their brains. It was an apparent reaction to the vaccine, which used a strand of human protein to prompt an immune response.

Despite the severe reactions of some patients, others in the interrupted trial may have responded positively to the vaccine, according to Wyeth’s follow-up examinations. The symptoms of some patients who fared well in the trial appeared to have stabilized, a contrast to the inexorable decline usually experienced in Alzheimer’s. Autopsies of five trial participants who later died of natural causes revealed evidence of plaque-clearing in their brains.

The results supported the idea that Alzheimer’s plaque can be attacked with immunotherapy. “It looked like the vaccine was doing the same thing we’ve seen in the animals,” Dr. Pangalos says.

After the failure of AN-1792, Wyeth and Elan worked to develop a safer vaccine and also focused on another form of immunotherapy: passive immunization.

Instead of vaccinating patients with a strand of amyloid protein and letting them form their own antibodies, passive immunization injects pre-made antibodies directly into patients. In theory, the antibodies then attach themselves to harmful plaque and dissolve it. Wyeth would deliver its antibody product, bapineuzumab, to patients through infusion, in a process much like chemotherapy for cancer patients.

In a joint announcement last month, Wyeth and Elan said a late-stage trial of the drug would begin in the second half of this year. Although history shows that the odds are against the success of any individual drug, the progress is an encouraging sign for a drug that many scientists regard as the most promising treatment in development for Alzheimer’s.

“It’s going to be the first test of what we call the amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s,” says David Morgan, an Alzheimer’s researcher at the University of South Florida. “Elan and Wyeth clearly are in the lead in developing immunotherapy.”

AT Wyeth’s research lab near Princeton, scientists have tested bapineuzumab and other compounds on genetically altered mice, using a special swimming pool equipped with an invisible platform.

When a mouse is placed in the pool, it instinctively begins swimming around to find a resting place. Once a normal mouse finds the platform the first time, it can find its way back on follow-up swims. But the genetically altered mice become lost.

“The Alzheimer’s mouse cannot remember the location of the platform,” says Reka Hosszu, a research scientist at Wyeth who works with the animals. She says that an Alzheimer’s mouse will paddle aimlessly in the pool.

After treatment, the Alzheimer’s mice can find the platform more easily. And their brains look better. In before-and-after images, it is clear that globs of toxic plaque have cleared. “You can get rid of pretty much all of the amyloid,” says Dr. Pangalos as he displays a three-dimensional image of a mouse brain on his computer. “And you can reverse their memory to normal, like a young mouse.”

If all goes according to Wyeth’s plan, it should work in humans, too. “We’re going after this,” Dr. Pangalos says, “and we’re not stopping until we’ve nailed it.”

Zen and the Art of Coping With Alzheimer’s

By Denise Grady : NY Times Article : August 14, 2007

During the YouTube forum with the Democratic presidential candidates in July, the first question about health care came from two middle-age brothers in Iowa, who faced the camera with their elderly mother. Not everybody with Alzheimer’s disease has two loving sons to take care of them, they said, adding that a boom in dementia is expected in the next few decades.

“What are you prepared to do to fight this disease now?” they asked.

The politicians mouthed generalities about health care, larded with poignant anecdotes. None of them answered the question about Alzheimer’s.

Science hasn’t done much better. There is no cure for Alzheimer’s and no way to prevent it. Scientists haven’t even stopped arguing about whether the gunk that builds up in the Alzheimer’s brain is a cause or an effect of the disease. Alzheimer’s is roaring down — a train wreck to come — on societies all over the world.

People in this country spend more than a $1 billion a year on prescription drugs marketed to treat it, but for most patients the pills have only marginal effects, if any, on symptoms and do nothing to stop the underlying disease process that eats away at the brain. Pressed for answers, most researchers say no breakthrough is around the corner, and it could easily be a decade or more before anything comes along that makes a real difference for patients.

Meanwhile, the numbers are staggering: 4.5 million people in the United States have Alzheimer’s, 1 in 10 over 65 and nearly half of those over 85. Taking care of them costs $100 billion a year, and the number of patients is expected to reach 11 million to 16 million by 2050. Experts say the disease will swamp the health system.

It’s already swamping millions of families, who suffer the anguish of seeing a loved one’s mind and personality disintegrate, and who struggle with caregiving and try to postpone the wrenching decision about whether they can keep the patient at home as helplessness increases, incontinence sets in and things are only going to get worse.

Drug companies are placing big bets on Alzheimer’s. Wyeth, for instance, has 23 separate projects aimed at developing new treatments. Hundreds of theories are under study at other companies large and small. Why not? People with Alzheimer’s and their families are so desperate that they will buy any drug that offers even a shred of hope, and many will keep using the drug even if the symptoms don’t get better, because they can easily be convinced that the patient would be even worse off without it.

It is telling, maybe a tacit admission of defeat, that a caregiving industry has sprung up around Alzheimer’s. Books, conferences and Web sites abound — how to deal with the anger, the wandering, the sleeping all day and staying up all night, the person who asks the same question 15 times in 15 minutes, wants to wear the same blouse every day and no longer recognizes her own children or knows what a toilet is for.

The advice is painfully and ironically reminiscent of the 1960s and ’70s, the literal and figurative high point for many of the people who are now coping with demented parents. The theme is, essentially, go with the flow. People with Alzheimer’s aren’t being stubborn or nasty on purpose; they can’t help it. Arguing and correcting will not only not help, but they will ratchet up the hostility level and make things worse. The person with dementia has been transported into a strange, confusing new world and the best other people can do is to try to imagine the view from there and get with the program.

If a patient asks for her mother, for instance, instead of pointing out that her mother has been dead for 40 years, it is better to say something like, “I wish your mother were here, too,” and then maybe redirect the conversation to something else, like what’s for lunch.

If Dad wants to polish off the duck sauce in a Chinese restaurant like it’s a bowl of soup, why not? If Grandma wants to help out by washing the dishes but makes a mess of it, leave her to it and just rewash them later when she’s not looking. Pull out old family pictures to give the patient something to talk about. Learn the art of fragmented, irrational conversation and follow the patient’s lead instead of trying to control the dialogue.

Basically, just tango on. And hope somebody will do the same for you when your time comes. Unless the big breakthrough happens first.

Alzheimer's Disease Overview

Alzheimer's disease (AD), one form of dementia, is a progressive, degenerative brain disease. It affects memory, thinking, and behavior.

Memory impairment is a necessary feature for the diagnosis of this or any type of dementia. Change in one of the following areas must also be present: language, decision-making ability, judgment, attention, and other areas of mental function and personality.

The rate of progression is different for each person. If AD develops rapidly, it is likely to continue to progress rapidly. If it has been slow to progress, it will likely continue on a slow course.

Alternative Names Senile dementia/Alzheimer's type (SDAT)

Causes » More than 4 million Americans currently have AD. The older you get, the greater your risk of developing AD, although it is not a part of normal aging. Family history is another common risk factor.

In addition to age and family history, risk factors for AD may include:

- Longstanding high blood pressure

- History of head trauma

- High levels of homocysteine (a body chemical that contributes to chronic illnesses such as heart disease, depression, and possibly AD)

- Female gender -- because women usually live longer than men, they are more likely to develop AD

The cause of AD is not entirely known but is thought to include both genetic and environmental factors. A diagnosis of AD is made based on characteristic symptoms and by excluding other causes of dementia.

Prior theories regarding the accumulation of aluminum, lead, mercury, and other substances in the brain leading to AD have been disproved. The only way to know for certain that someone had AD is by microscopic examination of a sample of brain tissue after death.

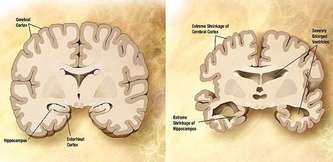

The brain tissue shows "neurofibrillary tangles" (twisted fragments of protein within nerve cells that clog up the cell), "neuritic plaques" (abnormal clusters of dead and dying nerve cells, other brain cells, and protein), and "senile plaques" (areas where products of dying nerve cells have accumulated around protein). Although these changes occur to some extent in all brains with age, there are many more of them in the brains of people with AD.

The destruction of nerve cells (neurons) leads to a decrease in neurotransmitters (substances secreted by a neuron to send a message to another neuron). The correct balance of neurotransmitters is critical to the brain.

By causing both structural and chemical problems in the brain, AD appears to disconnect areas of the brain that normally work together.

About 10 percent of all people over 70 have significant memory problems and about half of those are due to AD. The number of people with AD doubles each decade past age 70. Having a close blood relative who developed AD increases your risk.

Early onset disease can run in families and involves autosomal dominant, inherited mutations that may be the cause of the disease. So far, three early onset genes have been identified.

Late onset AD, the most common form of the disease, develops in people 60 and older and is thought to be less likely to occur in families. Late onset AD may run in some families, but the role of genes is less direct and definitive. These genes may not cause the problem itself, but simply increase the likelihood of formation of plaques and tangles or other AD-related pathologies in the brain.

In-Depth Causes »

In the early stages, the symptoms of AD may be subtle and resemble signs that people mistakenly attribute to "natural aging." Symptoms often include:

- Repeating statements

- Misplacing items

- Having trouble finding names for familiar objects

- Getting lost on familiar routes

- Personality changes

- Losing interest in things previously enjoyed

- Difficulty performing tasks that take some thought, but used to come easily, like balancing a checkbook, playing complex games (such as bridge), and learning new information or routines

- Forgetting details about current events

- Forgetting events in your own life history, losing awareness of who you are

- Problems choosing proper clothing

- Hallucinations, arguments, striking out, and violent behavior

- Delusions, depression, agitation

- Difficulty performing basic tasks like preparing meals and driving

- Understand language

- Recognize family members

- Perform basic activities of daily living such as eating, dressing, and bathing

The first step in diagnosing Alzheimer's disease is to establish that dementia is present. Then, the type of dementia should be clarified. A health care provider will take a history, do a physical exam (including a neurological exam), and perform a mental status examination.

Tests may be ordered to help determine if there is a treatable condition that could be causing dementia or contributing to the confusion of AD. These conditions include thyroid disease, vitamin deficiency, brain tumor, drug and medication intoxication, chronic infection, anemia, and severe depression.

AD usually has a characteristic pattern of symptoms and can be diagnosed by history and physical exam by an experienced clinician. Tests that are often done to evaluate or exclude other causes of dementia include computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and blood tests.

In the early stages of dementia, brain image scans may be normal. In later stages, an MRI may show a decrease in the size of the cortex of the brain or of the area of the brain responsible for memory (the hippocampus). While the scans do not confirm the diagnosis of AD, they do exclude other causes of dementia (such as stroke and tumor).

In-Depth Diagnosis »

Treatment

Unfortunately, there is no cure for AD. The goals in treating AD are to:

- Slow the progression of the disease.

- Manage behavior problems, confusion, and agitation.

- Modify the home environment.

- Support family members and other caregivers.

LIFESTYLE CHANGES

The following steps can help people with AD:

- Walk regularly with a caregiver or other reliable companion. This can improve communication skills and prevent wandering.

- Use bright light therapy to reduce insomnia and wandering.

- Listen to calming music. This may reduce wandering and restlessness, boost brain chemicals, ease anxiety, enhance sleep, and improve behavior.

- Get a pet dog.

- Practice relaxation techniques.

- Receive regular massages. This is relaxing and provides social interactions.

Several drugs are available to try to slow the progression of AD and possibly improve the person's mental capabilities. Memantine (Namenda) is currently the only drug approved for the treatment of moderate-to-severe Alzheimer’s disease.

Other medicines include donepezil (Aricept), rivastigmine (Exelon), galantamine (Razadyne, formerly called Reminyl), and tacrine (Cognex). These drugs affect the level of a neurotransmitter in the brain called acetylcholine. They may cause nausea and vomiting. Tacrine also causes an elevation in liver enzymes and must be taken four times a day. It is now rarely used.

Aricept is taken once a day and may stabilize or even improve the person's mental capabilities. It is generally well tolerated. Exelon seems to work in a similar way. It is taken twice a day.

Other medicines may be needed to control aggressive, agitated, or dangerous behaviors. These are usually given in very low doses.

It may be necessary to stop any medications that make confusion worse. Such medicines may include pain killers, cimetidine, central nervous system depressants, antihistamines, sleeping pills, and others. Never change or stop taking any medicines without first talking to your doctor.

SUPPLEMENTS

Folate (vitamin B9) is critical to the health of the nervous system. Together with some other B vitamins, folate is also responsible for clearing homocysteine (a body chemical that contributes to chronic illnesses) from the blood. High levels of homocysteine and low levels of both folate and vitamin B12 have been found in people with AD. Although the benefits of taking these B vitamins for AD is not entirely clear, it may be worth considering them, particularly if your homocysteine levels are high.

Antioxidant supplements, like ginkgo biloba and vitamin E, scavenge free radicals. These products of metabolism are highly reactive and can damage cells throughout the body.

Vitamin E dissolves in fat, readily enters the brain, and may slow down cell damage. In at least one well-designed study of people with AD who were followed for 2 years, those who took vitamin E supplements had improved symptoms compared to those who took a placebo pill. Patients who take blood-thinning medications like warfarin (Coumadin) may should talk to their doctor before taking vitamin E.