- RETIREMENT ANNOUNCEMENT

- HOME PAGE

- "MYCHART" the new patient portal

- BELMONT MEDICAL ASSOCIATES

- MOUNT AUBURN HOSPITAL

- EMERGENCIES

- PRACTICE PHILOSOPHY

- MY RESUME

- TELEMEDICINE CONSULTATION

- CONTACT ME

- LAB RESULTS

- ePRESCRIPTIONS

- eREFERRALS

- RECORD RELEASE

- MEDICAL SCRIBE

- PHYSICIAN ASSISTANT (PA)

- Medicare Annual Wellness Visit

- Case management/Social work

- Quality Care Measures

- Emergency closing notice

- FEEDBACK

- Talking to your doctor

- Choosing..... and losing a doctor

- INDEX A - Z

- ALLERGIC REACTIONS

- Alternative Medicine

- Alzheimer's Disease

- Bladder Problems

- Blood disorders

- Cancer Concerns

- GENETIC TESTING FOR HEREDITARY CANCER

- Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

- Controversial Concerns

- CPR : Learn and save a life

- CRP : Inflammatory marker

- Diabetes Management

- Dizziness, Vertigo,Tinnitus and Hearing Loss

- EXERCISE

- FEMALE HEALTH

-

GASTROINTESTINAL topics

- Appendicitis

- BRAT diet

- Celiac Disease or Sprue

- Crohn's Disease

- Gastroenterologists for Colon Cancer Screening

- Colonoscopy PREP

- Constipation

- Gluten sensitivity, but not celiac disease

- Heartburn and GERD

- Hemorrhoids and Anal fissure

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- NASH : Non Alcoholic Steato Hepatitis

- FEET PROBLEMS

- HEART RELATED topics

-

INFECTIOUS DISEASES

- Antibiotic Resistance

- Cat bites >

- Clostridia difficile infection - the "antibiotic associated germ"

- CORONA VIRUS

- Dengue Fever and Chikungunya Fever

- Food borne illnesses

- Shingles Vaccine

- Hepatitis B

- Hepatitis C

- Herpes

- Influenza

- Helicobacter pylori - the "ulcer germ"

- HIV Screening

- Lyme and other tick borne diseases

- Measles

- Meningitis

- MRSA (Staph infection)

- Norovirus

- Sexually Transmitted Diseases

- Shingles (Herpes Zoster)

- Sinusitis

- West Nile Virus

- Whooping Cough (Pertussis)

- Zika virus and pregnancy

- INSURANCE related topics

- KIDNEY STONES

- LEG CRAMPS

- LIBRARY for patients

- LIFE DECISIONS

- MALE HEALTH

- Medication/Drug side effects

- MEDICAL MARIJUANA

- MENTAL HEALTH

- Miscellaneous Articles

-

NUTRITION - EXERCISE - WEIGHT

- Cholesterol : New guidelines for treatment

- Advice to lower your cholesterol

- Cholesterol : Control

- Cholesterol : Raising your HDL Level

- Exercise

- Food : Making Smart Choices

- Food : Making Poor Choices

- Food : Grape Fruit and Drug Interaction

- Food : Vitamins, Minerals and Supplements

- Omega 3 fatty acids

- Vitamin B12 deficiency

- Vitamin D

- Weight Loss

- ORTHOPEDICS

- PAIN

- PATIENTS' RIGHTS

- SKIN

- SLEEP

- SMOKING

- STROKE

- THYROID

- SUBSTANCE ABUSE

- Travel and Vaccination

- TREMOR

- Warfarin Anticoagulation

- OTHER STUFF FOLLOWS

- Fact or Opinion?

- Hippocratic Oath

- FREE ADVICE.......for what its worth!

- LAUGHTER.....is the best medicine

- Physicians Pet Peeves

- PHOTO ALBUM - its not all work!

- Cape Town, South Africa

- Tribute page

- The 100 Club

- Free Wi-Fi

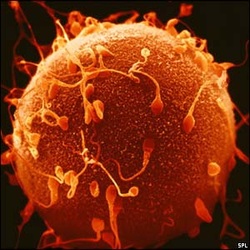

PREGNANT

or

thinking about getting pregnant?

Oversold prenatal tests

By Beth Daley : NE Center for Investigative Reporting : December 14, 2014

Stacie Chapman’s heart skipped when she answered the phone at home and her doctor — rather than a nurse — was on the line. More worrisome was the doctor’s gentle tone as she asked, “Where are you?”

On that spring day in 2013, Dr. Jayme Sloan had bad news for Chapman, who was nearly three months pregnant. Her unborn child had tested positive for Edwards syndrome, a genetic condition associated with severe birth defects. If her baby — a boy, the screening test had shown — was born alive, he probably would not live long.

Sloan explained that the test — MaterniT21 PLUS — has a 99 percent detection rate. Though Sloan offered additional testing to confirm the result, a distraught Chapman said she wanted to terminate the pregnancy immediately.

What she — and the doctor — did not understand, Chapman’s medical records indicate, was that there was a good chance her screening result was wrong. There is, it turns out, a huge and crucial difference between a test that can detect a potential problem and one reliable enough to diagnose a life-threatening condition for certain. The screening test only does the first.

Sparked by the sequencing of the human genome a decade ago, a new generation of prenatal screening tests, including MaterniT21, has exploded onto the market in the past three years. The unregulated screens claim to detect with near-perfect accuracy the risk that a fetus may have Down or Edwards syndromes, and a growing list of other chromosomal abnormalities.

Hundreds of thousands of women in early pregnancy have taken these tests — through a simple blood draw in the doctor’s office — and studies show them to perform far better than traditional blood tests and ultrasound screening.

But a three-month examination by the New England Center for Investigative Reporting has found that companies are overselling the accuracy of their tests and doing little to educate expecting parents or their doctors about the significant risks of false alarms.

Two recent industry-funded studies show that test results indicating a fetus is at high risk for a chromosomal condition can be a false alarm half of the time. And the rate of false alarms goes up the more rare the condition, such as Trisomy 13, which almost always causes death.

Companies selling the most popular of these screens do not make it clear enough to patients and doctors that the results of their tests are not reliable enough to make a diagnosis.

California-based Sequenom Inc., for instance, promises on its web page that its MaterniT21 blood test provides “simple, clear results.” Only far down below does Sequenom disclose that “no test is perfect” and that theirs can produce erroneous results “in rare cases.”

Now, evidence is building that some women are terminating pregnancies based on the screening tests alone. A recent study by another California-based testing company, Natera Inc., which offers a screen called Panorama, found that 6.2 percent of women who received test results showing their fetus at high risk for a chromosomal condition terminated pregnancies without getting a diagnostic test such as an amniocentesis.

And at Stanford University, there have been at least three cases of women aborting healthy fetuses that had received a high-risk screen result.

“The worry is women are terminating without really knowing if [the initial test result] is true or not,” said Athena Cherry, professor of pathology at the Stanford University School of Medicine, whose lab examined the cells of the healthy aborted fetuses.

In one of the three Stanford cases, the woman actually obtained a confirmatory test and was told the fetus was fine, but aborted anyway because of her faith in the screening company’s accuracy claims. “She felt it couldn’t be wrong,” Cherry said.

Companies that sell the screens stand behind their tests, saying they provide much more reliable assurance for expecting mothers than earlier screens. Some say their research focused first on how to accurately identify fetuses with potential genetic defects and only recently have they been able to get enough data to understand how often positive tests are wrong.

“The clinical performance of [noninvasive prenatal tests] has been extremely robust,” Dr. Vance Vanier, vice president of marketing for reproductive and genetic health for San Diego-based Illumina Inc., which offers the Verifi prenatal screen, wrote in an e-mail statement.

The screens are not subject to approval by the Food and Drug Administration. Because of a regulatory loophole, the companies operate free of agency oversight and the kind of independent analysis that would validate their accuracy claims. Doctors often get that information from salespeople, according to doctors themselves.

And there are other emerging concerns about the new generation of prenatal tests. Two Boston-area obstetricians, with funding from a testing company, recently sent samples from two nonpregnant women to five testing companies for analysis. Three companies returned samples indicating they came from a woman who was carrying a healthy female fetus.

Meanwhile, there are a growing number of cases emerging of women told their screen shows virtually no chance of a fetus having a problem but who then deliver a child with a genetic condition.

“My son lived for four days,’’ said Belinda Boydston, a web/graphic designer in Chandler, Ariz., whose son was born with Edwards syndrome despite a screening test showing that he was extremely unlikely to carry the condition.

But Stacie Chapman knew nothing about these uncertainties when Dr. Sloan told her that her unborn son had screened positive for a genetic condition that was largely incompatible with life.

Hysterical with grief when she hung up, Chapman phoned her husband at a Las Vegas airport on his way home from a business trip. Together, sobbing, they concluded that their son would only suffer if he survived birth. So, that afternoon, Sloan put her in touch with a nurse who found a doctor who could do the termination the next morning.

Chapman spent the afternoon Googling the horrors of Edwards syndrome, with its heart defects, development delays, and extraordinarily high mortality. She was steeling herself for the termination when Sloan called back,urging her to wait, according to Chapman’s medical record.

Chapman had a diagnostic test and learned her son did not have Edwards syndrome. A healthy Lincoln Samuel just turned 1 and has a wide smile that reminds Chapman of her recently deceased father.

However briefly considered, their decision to abort — informed by the MaterniT21’s advertised 99 percent detection statistic — haunts them to this day.

“He is so perfect,’’ Chapman, 43, said, choking up as she watched her son play with a toy lamb. “I almost terminated him.”

Overselling a screen

Advertisements for these new prenatal screens are filled with bright skies, serene, full-bellied women, and, most of all, assurances that the tests can be trusted.

“Never maybe,” promises MaterniT21 in pamphlets. Panorama states its test is “99% Accurate, Simple & Trusted” on a web page.

The screens, conducted as early as nine weeks into a pregnancy, detect placental DNA in a mother’s blood and test it for chromosomal abnormalities as well as gender.

Originally designed for older women and others at higher risk for having a problematic fetus, some of the screens are now marketed to all pregnant women. Company and analyst data indicate there have probably been between 450,000 to 800,000 tests performed in the United States since 2011 and several companies are racing to corner what one market research firm predicts will be a $3.6 billion global industry by 2019.

Independent medical experts say the new screens are far better able to rule out the possibility of certain fetal conditions, especially Down syndrome, than traditional ultrasounds and blood screenings.

That dramatically cuts down on the number of women who are incorrectly told their fetus may have a problem and helps them avoid a more invasive follow-up test, such as amniocentesis, which carries a small risk of miscarriage.

But the new screens are not perfect and can indicate fetuses may have serious genetic abnormalities when they do not, the industry’s own research shows.

For example, among older pregnant women such as Chapman, for whom chromosomal abnormalities are more common, a positive test result for Edwards syndrome is accurate around 64 percent of the time, according to a recent study by Quest Diagnostics, a large provider of medical tests and other services. That means Baby Lincoln had about a 36 percent chance of not having the condition.

Among younger women who are at lower risk for fetal abnormalities, the error rate is even higher. Only about 40 percent of the positive tests showing high risk for Edwards syndrome turned out to be accurate, according to a recent well-regarded Illumina study of its Verifi screen.

The testing companies do recommend that women who get a positive screen result should seek additional tests to confirm it — much the way a woman whose mammogram showed potential breast cancer would undergo a biopsy to determine whether the dark spots actually are cancerous.

But some companies blur the distinction between the results of their screening tests and a true diagnosis, potentially confusing patients and doctors about the trustworthiness and meaning of their test results. Illumina, for example, claims its Verifi screen has “near-diagnostic accuracy,” a term medical experts say has no meaning.

“The companies have done a very poor job of education [and] advertising this new technology, failing to make clear that it is screening testing with very good but inevitably not perfect test performance . . . and that doctors are recommending, offering, ordering a test they do not fully understand,’’ said Dr. Michael Greene, director of obstetrics at Massachusetts General Hospital and a professor at Harvard Medical School.

Company officials say they are now focusing on the accuracy of all test results, including false positives, carrying out research on their frequency, and looking for ways to reduce the stress of these events.

Getting patients to understand limits on the accuracy of positive test results can be “extremely challenging,” said Juan-Sebastian Saldivar, vice president of clinical services and medical affairs at Sequenom, which offers the screen that Chapman used. He said the company works with doctors on how to best explain it to patients.

Officials at Natera, which offers the Panorama test, insist their screens are highly accurate and produce relatively few false alarms. A company-funded study found that positive test results are correct 83 percent of the time, which is more accurate than studies of other tests have shown.

Melissa Stosic, Natera’s director of medical education and clinical affairs, stresses that the company doesn’t oversell the test, working to educate doctors “to be very clear it’s a screening and not diagnostic.”

However, the same Natera study found that some women are ignoring that advice and having abortions without getting a confirmatory diagnostic test. In its study, 22 women out of 356 who were told their fetuses were at high risk for some abnormality terminated the pregnancy without getting an invasive test to confirm the results.

“It’s troubling,’’ said Katie Stoll, a genetic counselor in Washington state who has written extensively on the marketing of noninvasive prenatal screens. “Women are getting the wrong message.”

A short life

The field of this prenatal testing is so new, and the research so dominated by the companies selling the tests, that basic questions about their reliability and testing methods remain unresolved.

For instance, screening companies say they have had exceedingly few cases of women whose screen shows little problem, but then deliver a baby with a genetic condition. Yet such cases are popping up across the country.

It is not clear how large a problem it is, but critics say the troubling anecdotes are another example of quality control concerns that are not being independently vetted.

Belinda Boydston, 43, of Arizona, was stunned to give birth to a baby with Edwards syndrome after a Harmony screen result in October 2013 showed her fetus had only a 0.01 percent chance of having Edwards syndrome, also known as Trisomy 18.

“I delivered prematurely, and they knew right away he had Trisomy 18,” Boydston said, recounting the scene in the delivery room. “I could hear them talking, ‘Didn’t she have that test?’ ”

This year alone, at the Emory Healthcare Department of Human Genetics in Georgia, officials have seen five newborns with Down syndrome whose prenatal noninvasive screens indicated that there was little risk of the condition.

And a couple in Belmont, Calif., sued Ariosa Diagnostics Inc. last year, alleging its Harmony screen falsely indicated their child would not have Down syndrome and that the company’s marketing material misled patients about the screen’s accuracy. The lawsuit is still pending. Ariosa declined to comment, as did Roche, which is acquiring it.

“There needs to be more transparency and accuracy from the companies about what their results mean,’’ said Mary Norton, vice chair of genetics in the department of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of California San Francisco. Norton, who has received funding from Ariosa and Natera, said research in the field is almost all being funded by industry. “There isn’t a lot of independent research going on.”

FDA regulatory loophole

The loophole that allows unregulated tests in the marketplace dates back to the mid-1970s, when the FDA began overseeing diagnostic tests. The FDA exempted what was then a small group of relatively simple tests developed, manufactured, and performed all in a single lab — for example, in a hospital.

In the past decade, for-profit companies have used that regulatory running room to develop complex tests to diagnose or screen for conditions ranging from cancer to Lyme disease and now, fetal chromosomal conditions. Not all tests undergo robust independent review and it is challenging for the public to distinguish good and bad tests, medical experts say.

In late September, the FDA stepped in, publishing draft regulations for the industry expected to take nine years to be fully phased in. Officials there said that the new prenatal tests would probably be among the first few groups to be regulated. Already, the industry is expected to challenge the legality of those rules and a trade group, the American Clinical Laboratory Association, has retained Harvard Law professor Laurence Tribe to help represent them.

However, the FDA has made it clear that the companies don’t have to wait for regulations to act.

We “have told the [prenatal] companies . . . they really should bring their test into the agency,’’ said Alberto Gutierrez, director of the FDA’s office of in vitro diagnostics in the Center for Devices and Radiological Health. He indicated they could voluntarily submit to regulation, as other types of diagnostic testing companies have done.

While the regulatory fight goes on, doctors say one immediate way to limit potential misuse of possibly inaccurate prenatal screening results is for women to receive genetic counseling before they get the screens — and after. Several women, including Chapman, told the New England Center they were offered the prenatal screens without any clear understanding of what their fetus would be tested for other than Down syndrome and to learn the sex of the baby.

Lincoln Chapman, Stacie’s husband, said he will be forever grateful to Dr. Sloan, of Harvard Vanguard Medical Associates in Boston, for calling Stacie Chapman back to more strongly recommend further tests.

But Stacie Chapman remains conflicted about the doctor’s first call that set in motion the near termination of her pregnancy. Sloan did not stress that the test was just a screen that could be wrong, she recalled.

“I didn’t seek this test out — this test was offered to me by the doctor’s office. They should know how it performs,’’ Chapman said, adding that she would never have considered a pregnancy termination if she had better understood the odds that her result could be wrong.

A health professional involved in Chapman’s case who was not authorized by her employer to comment said Sloan initially was unaware that the screen could be wrong a significant amount of the time.

Sloan did not return calls to discuss her understanding of the statistics, but a Harvard Vanguard statement noted its policy recommends genetic counseling and confirmatory testing for women whose fetuses test positive for a genetic abnormality.

Chapman said enormous heartache could have been avoided in her family if companies advertised more scrupulously, or if her doctor had understood the limitations of the screen.

As millions of women in the United States and elsewhere expect babies this year, some inevitably will be in the same situation as Chapman.

“You know, when I found out [the baby] was fine, my midwife said, ‘You are one in a million, you are so lucky,’ ” Chapman recalls. “But you know? I really wasn’t.”

By Beth Daley : NE Center for Investigative Reporting : December 14, 2014

Stacie Chapman’s heart skipped when she answered the phone at home and her doctor — rather than a nurse — was on the line. More worrisome was the doctor’s gentle tone as she asked, “Where are you?”

On that spring day in 2013, Dr. Jayme Sloan had bad news for Chapman, who was nearly three months pregnant. Her unborn child had tested positive for Edwards syndrome, a genetic condition associated with severe birth defects. If her baby — a boy, the screening test had shown — was born alive, he probably would not live long.

Sloan explained that the test — MaterniT21 PLUS — has a 99 percent detection rate. Though Sloan offered additional testing to confirm the result, a distraught Chapman said she wanted to terminate the pregnancy immediately.

What she — and the doctor — did not understand, Chapman’s medical records indicate, was that there was a good chance her screening result was wrong. There is, it turns out, a huge and crucial difference between a test that can detect a potential problem and one reliable enough to diagnose a life-threatening condition for certain. The screening test only does the first.

Sparked by the sequencing of the human genome a decade ago, a new generation of prenatal screening tests, including MaterniT21, has exploded onto the market in the past three years. The unregulated screens claim to detect with near-perfect accuracy the risk that a fetus may have Down or Edwards syndromes, and a growing list of other chromosomal abnormalities.

Hundreds of thousands of women in early pregnancy have taken these tests — through a simple blood draw in the doctor’s office — and studies show them to perform far better than traditional blood tests and ultrasound screening.

But a three-month examination by the New England Center for Investigative Reporting has found that companies are overselling the accuracy of their tests and doing little to educate expecting parents or their doctors about the significant risks of false alarms.

Two recent industry-funded studies show that test results indicating a fetus is at high risk for a chromosomal condition can be a false alarm half of the time. And the rate of false alarms goes up the more rare the condition, such as Trisomy 13, which almost always causes death.

Companies selling the most popular of these screens do not make it clear enough to patients and doctors that the results of their tests are not reliable enough to make a diagnosis.

California-based Sequenom Inc., for instance, promises on its web page that its MaterniT21 blood test provides “simple, clear results.” Only far down below does Sequenom disclose that “no test is perfect” and that theirs can produce erroneous results “in rare cases.”

Now, evidence is building that some women are terminating pregnancies based on the screening tests alone. A recent study by another California-based testing company, Natera Inc., which offers a screen called Panorama, found that 6.2 percent of women who received test results showing their fetus at high risk for a chromosomal condition terminated pregnancies without getting a diagnostic test such as an amniocentesis.

And at Stanford University, there have been at least three cases of women aborting healthy fetuses that had received a high-risk screen result.

“The worry is women are terminating without really knowing if [the initial test result] is true or not,” said Athena Cherry, professor of pathology at the Stanford University School of Medicine, whose lab examined the cells of the healthy aborted fetuses.

In one of the three Stanford cases, the woman actually obtained a confirmatory test and was told the fetus was fine, but aborted anyway because of her faith in the screening company’s accuracy claims. “She felt it couldn’t be wrong,” Cherry said.

Companies that sell the screens stand behind their tests, saying they provide much more reliable assurance for expecting mothers than earlier screens. Some say their research focused first on how to accurately identify fetuses with potential genetic defects and only recently have they been able to get enough data to understand how often positive tests are wrong.

“The clinical performance of [noninvasive prenatal tests] has been extremely robust,” Dr. Vance Vanier, vice president of marketing for reproductive and genetic health for San Diego-based Illumina Inc., which offers the Verifi prenatal screen, wrote in an e-mail statement.

The screens are not subject to approval by the Food and Drug Administration. Because of a regulatory loophole, the companies operate free of agency oversight and the kind of independent analysis that would validate their accuracy claims. Doctors often get that information from salespeople, according to doctors themselves.

And there are other emerging concerns about the new generation of prenatal tests. Two Boston-area obstetricians, with funding from a testing company, recently sent samples from two nonpregnant women to five testing companies for analysis. Three companies returned samples indicating they came from a woman who was carrying a healthy female fetus.

Meanwhile, there are a growing number of cases emerging of women told their screen shows virtually no chance of a fetus having a problem but who then deliver a child with a genetic condition.

“My son lived for four days,’’ said Belinda Boydston, a web/graphic designer in Chandler, Ariz., whose son was born with Edwards syndrome despite a screening test showing that he was extremely unlikely to carry the condition.

But Stacie Chapman knew nothing about these uncertainties when Dr. Sloan told her that her unborn son had screened positive for a genetic condition that was largely incompatible with life.

Hysterical with grief when she hung up, Chapman phoned her husband at a Las Vegas airport on his way home from a business trip. Together, sobbing, they concluded that their son would only suffer if he survived birth. So, that afternoon, Sloan put her in touch with a nurse who found a doctor who could do the termination the next morning.

Chapman spent the afternoon Googling the horrors of Edwards syndrome, with its heart defects, development delays, and extraordinarily high mortality. She was steeling herself for the termination when Sloan called back,urging her to wait, according to Chapman’s medical record.

Chapman had a diagnostic test and learned her son did not have Edwards syndrome. A healthy Lincoln Samuel just turned 1 and has a wide smile that reminds Chapman of her recently deceased father.

However briefly considered, their decision to abort — informed by the MaterniT21’s advertised 99 percent detection statistic — haunts them to this day.

“He is so perfect,’’ Chapman, 43, said, choking up as she watched her son play with a toy lamb. “I almost terminated him.”

Overselling a screen

Advertisements for these new prenatal screens are filled with bright skies, serene, full-bellied women, and, most of all, assurances that the tests can be trusted.

“Never maybe,” promises MaterniT21 in pamphlets. Panorama states its test is “99% Accurate, Simple & Trusted” on a web page.

The screens, conducted as early as nine weeks into a pregnancy, detect placental DNA in a mother’s blood and test it for chromosomal abnormalities as well as gender.

Originally designed for older women and others at higher risk for having a problematic fetus, some of the screens are now marketed to all pregnant women. Company and analyst data indicate there have probably been between 450,000 to 800,000 tests performed in the United States since 2011 and several companies are racing to corner what one market research firm predicts will be a $3.6 billion global industry by 2019.

Independent medical experts say the new screens are far better able to rule out the possibility of certain fetal conditions, especially Down syndrome, than traditional ultrasounds and blood screenings.

That dramatically cuts down on the number of women who are incorrectly told their fetus may have a problem and helps them avoid a more invasive follow-up test, such as amniocentesis, which carries a small risk of miscarriage.

But the new screens are not perfect and can indicate fetuses may have serious genetic abnormalities when they do not, the industry’s own research shows.

For example, among older pregnant women such as Chapman, for whom chromosomal abnormalities are more common, a positive test result for Edwards syndrome is accurate around 64 percent of the time, according to a recent study by Quest Diagnostics, a large provider of medical tests and other services. That means Baby Lincoln had about a 36 percent chance of not having the condition.

Among younger women who are at lower risk for fetal abnormalities, the error rate is even higher. Only about 40 percent of the positive tests showing high risk for Edwards syndrome turned out to be accurate, according to a recent well-regarded Illumina study of its Verifi screen.

The testing companies do recommend that women who get a positive screen result should seek additional tests to confirm it — much the way a woman whose mammogram showed potential breast cancer would undergo a biopsy to determine whether the dark spots actually are cancerous.

But some companies blur the distinction between the results of their screening tests and a true diagnosis, potentially confusing patients and doctors about the trustworthiness and meaning of their test results. Illumina, for example, claims its Verifi screen has “near-diagnostic accuracy,” a term medical experts say has no meaning.

“The companies have done a very poor job of education [and] advertising this new technology, failing to make clear that it is screening testing with very good but inevitably not perfect test performance . . . and that doctors are recommending, offering, ordering a test they do not fully understand,’’ said Dr. Michael Greene, director of obstetrics at Massachusetts General Hospital and a professor at Harvard Medical School.

Company officials say they are now focusing on the accuracy of all test results, including false positives, carrying out research on their frequency, and looking for ways to reduce the stress of these events.

Getting patients to understand limits on the accuracy of positive test results can be “extremely challenging,” said Juan-Sebastian Saldivar, vice president of clinical services and medical affairs at Sequenom, which offers the screen that Chapman used. He said the company works with doctors on how to best explain it to patients.

Officials at Natera, which offers the Panorama test, insist their screens are highly accurate and produce relatively few false alarms. A company-funded study found that positive test results are correct 83 percent of the time, which is more accurate than studies of other tests have shown.

Melissa Stosic, Natera’s director of medical education and clinical affairs, stresses that the company doesn’t oversell the test, working to educate doctors “to be very clear it’s a screening and not diagnostic.”

However, the same Natera study found that some women are ignoring that advice and having abortions without getting a confirmatory diagnostic test. In its study, 22 women out of 356 who were told their fetuses were at high risk for some abnormality terminated the pregnancy without getting an invasive test to confirm the results.

“It’s troubling,’’ said Katie Stoll, a genetic counselor in Washington state who has written extensively on the marketing of noninvasive prenatal screens. “Women are getting the wrong message.”

A short life

The field of this prenatal testing is so new, and the research so dominated by the companies selling the tests, that basic questions about their reliability and testing methods remain unresolved.

For instance, screening companies say they have had exceedingly few cases of women whose screen shows little problem, but then deliver a baby with a genetic condition. Yet such cases are popping up across the country.

It is not clear how large a problem it is, but critics say the troubling anecdotes are another example of quality control concerns that are not being independently vetted.

Belinda Boydston, 43, of Arizona, was stunned to give birth to a baby with Edwards syndrome after a Harmony screen result in October 2013 showed her fetus had only a 0.01 percent chance of having Edwards syndrome, also known as Trisomy 18.

“I delivered prematurely, and they knew right away he had Trisomy 18,” Boydston said, recounting the scene in the delivery room. “I could hear them talking, ‘Didn’t she have that test?’ ”

This year alone, at the Emory Healthcare Department of Human Genetics in Georgia, officials have seen five newborns with Down syndrome whose prenatal noninvasive screens indicated that there was little risk of the condition.

And a couple in Belmont, Calif., sued Ariosa Diagnostics Inc. last year, alleging its Harmony screen falsely indicated their child would not have Down syndrome and that the company’s marketing material misled patients about the screen’s accuracy. The lawsuit is still pending. Ariosa declined to comment, as did Roche, which is acquiring it.

“There needs to be more transparency and accuracy from the companies about what their results mean,’’ said Mary Norton, vice chair of genetics in the department of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of California San Francisco. Norton, who has received funding from Ariosa and Natera, said research in the field is almost all being funded by industry. “There isn’t a lot of independent research going on.”

FDA regulatory loophole

The loophole that allows unregulated tests in the marketplace dates back to the mid-1970s, when the FDA began overseeing diagnostic tests. The FDA exempted what was then a small group of relatively simple tests developed, manufactured, and performed all in a single lab — for example, in a hospital.

In the past decade, for-profit companies have used that regulatory running room to develop complex tests to diagnose or screen for conditions ranging from cancer to Lyme disease and now, fetal chromosomal conditions. Not all tests undergo robust independent review and it is challenging for the public to distinguish good and bad tests, medical experts say.

In late September, the FDA stepped in, publishing draft regulations for the industry expected to take nine years to be fully phased in. Officials there said that the new prenatal tests would probably be among the first few groups to be regulated. Already, the industry is expected to challenge the legality of those rules and a trade group, the American Clinical Laboratory Association, has retained Harvard Law professor Laurence Tribe to help represent them.

However, the FDA has made it clear that the companies don’t have to wait for regulations to act.

We “have told the [prenatal] companies . . . they really should bring their test into the agency,’’ said Alberto Gutierrez, director of the FDA’s office of in vitro diagnostics in the Center for Devices and Radiological Health. He indicated they could voluntarily submit to regulation, as other types of diagnostic testing companies have done.

While the regulatory fight goes on, doctors say one immediate way to limit potential misuse of possibly inaccurate prenatal screening results is for women to receive genetic counseling before they get the screens — and after. Several women, including Chapman, told the New England Center they were offered the prenatal screens without any clear understanding of what their fetus would be tested for other than Down syndrome and to learn the sex of the baby.

Lincoln Chapman, Stacie’s husband, said he will be forever grateful to Dr. Sloan, of Harvard Vanguard Medical Associates in Boston, for calling Stacie Chapman back to more strongly recommend further tests.

But Stacie Chapman remains conflicted about the doctor’s first call that set in motion the near termination of her pregnancy. Sloan did not stress that the test was just a screen that could be wrong, she recalled.

“I didn’t seek this test out — this test was offered to me by the doctor’s office. They should know how it performs,’’ Chapman said, adding that she would never have considered a pregnancy termination if she had better understood the odds that her result could be wrong.

A health professional involved in Chapman’s case who was not authorized by her employer to comment said Sloan initially was unaware that the screen could be wrong a significant amount of the time.

Sloan did not return calls to discuss her understanding of the statistics, but a Harvard Vanguard statement noted its policy recommends genetic counseling and confirmatory testing for women whose fetuses test positive for a genetic abnormality.

Chapman said enormous heartache could have been avoided in her family if companies advertised more scrupulously, or if her doctor had understood the limitations of the screen.

As millions of women in the United States and elsewhere expect babies this year, some inevitably will be in the same situation as Chapman.

“You know, when I found out [the baby] was fine, my midwife said, ‘You are one in a million, you are so lucky,’ ” Chapman recalls. “But you know? I really wasn’t.”

Breakthroughs in Prenatal Screening

By Jane E. Brody : NY Times : October 7, 2013

More than 30 years ago, a 37-year-old friend of mine with an unplanned fourth pregnancy was told by her obstetrician that an amniocentesis was “too dangerous” and could cause a miscarriage. She ultimately bore a child severely affected by Down syndrome, which could have been detected with the test.

Today, my friend’s story would have a different trajectory. She would have a series of screening tests, and if the results suggested a high risk of Down syndrome, then an amniocentesis or chorionic villus sampling (C.V.S.) to make the diagnosis. She’d be given the option to abort the pregnancy.

In the future, a woman who decides to continue a Down syndrome pregnancy may also be offered prenatal treatment to temper the developmental harm to the fetus.

Prenatal diagnosis, today a routine part of obstetric care, has made great strides since the mid-1970s and is now on the cusp of further revolutionary developments.

In the nearly four decades since amniocentesis became widely accepted, new techniques have gradually improved the safety and accuracy of prenatal diagnosis. Prenatal tests for more than 800 genetic disorders have been developed. And the number of women who must undergo amniocentesis or C.V.S. has been greatly reduced.

The newest screening test, highly accurate and noninvasive, relies on fetal genetic fragments found in the mother’s blood. Available commercially from four companies, this test is so accurate in detecting Down syndrome that few, if any, affected fetuses are missed, and far fewer women need an invasive procedure to confirm or refute the presence of Down, according to studies in several countries.

The new test, done late in the first trimester of pregnancy, can also detect other genetic diseases, like extra copies of chromosomes 13 and 18, and a missing sex chromosome. It is not yet approved by the Food and Drug Administration, however, and the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology currently recommends it only for women at high risk for having a baby with a chromosomal abnormality.

But any woman can get the new screening test if her doctor orders it and she is willing to pay for it herself, according to Dr. Diana W. Bianchi, a neonatologist and geneticist at Tufts University School of Medicine. Dr. Bianchi said she expects it will soon become routine for all pregnant women because, in addition to its “extraordinary accuracy” in detecting a Down syndrome pregnancy, it can be done earlier than other tests, and reduces costs and the risk of complications.

Down syndrome, which occurs in about one in every 700 births in the United States, is by far the most common chromosomal abnormality. It causes physical and intellectual disabilities that range from mild to severe.

In the past, the decision to undergo an amniocentesis or C.V.S. was based on a woman’s age or genetic history. The older the woman, the greater her risk of bearing a child with genetic defects due to an abnormal number of chromosomes.

It is now standard practice to offer all pregnant women a series of noninvasive screening tests in the first and second trimesters of pregnancy to assess the chances that a fetus has the extra copy of chromosome 21, which causes Down syndrome. It is then up to the woman to decide whether to undergo C.V.S. or an amniocentesis.

Taken together, these older screening tests pick up about 92 percent of cases of Down syndrome but miss 8 percent. And they yield false-positive results incorrectly indicating the presence of Down in about 5 percent of fetuses.

“This means a lot of women are needlessly worried and a lot have amnios that are not medically necessary,” Dr. Bianchi explained at a meeting last December of the March of Dimes.

Amniocentesis is performed between 15 and 20 weeks of gestation and involves inserting a long needle into a woman’s uterus to extract some of the fluid and cells surrounding the fetus. In C.V.S., usually done at 11 weeks gestation, the fetal cell sample is taken from the placenta. The cells are then analyzed for possible genetic defects. There is a small risk of miscarriage associated with both procedures.

But the new tests of fetal DNA from the mother’s blood detect all or nearly all cases of Down syndrome, and they return false-positive results in fewer than 1 percent of cases. Only those with a positive result need a C.V.S. or amniocentesis to confirm a Down syndrome pregnancy, and only about one woman in 1,000 who are tested requires such an invasive procedure to learn that her fetus does not have Down syndrome.

In a recent article in The New England Journal of Medicine, however, Stephanie Morain, a doctoral candidate at Harvard who studies medical ethics, and her co-authors said the fetal DNA tests have some disadvantages. They miss some chromosomal abnormalities detected by standard screening techniques, and they are “not widely covered by insurance.” Prices for the tests range from about $800 to more than $2,000, although some companies offer “introductory pricing” specials at about $200.

The new tests are also not required to meet the strict standards of safety and effectiveness established by the F.D.A., and they are valid only in singleton pregnancies. Nonetheless, tens of thousands of the fetal DNA tests have been performed to date.

The new test requires just a few teaspoons of a pregnant woman’s blood. During pregnancy, a woman’s blood contains cell-free DNA from herself and her unborn baby. On average, Dr. Bianchi said in an interview, at around 10 weeks of gestation, about 10 to 12 percent of the DNA in a woman’s blood will be fetal DNA from the placenta.

Using modern genetic sequencing techniques, the fetal DNA can be rapidly analyzed at a relatively low cost, in part because multiple samples from different women can be examined simultaneously.

As with other screening tests, the new DNA tests are “not diagnostic,” Dr. Lee P. Shulman, a geneticist at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, emphasized. A positive result on the test must always be confirmed by a C.V.S. or amniocentesis. Dr. Bianchi is now most excited by the prospect of treating a Down syndrome fetus before birth to minimize the disorder’s neurological effects. Studies have shown that giving pregnant mice medication that counters fetal oxidative stress results in more normal brain development of pups with Down syndrome.

When prenatal testing reveals that a fetus has a chromosomal defect or some other serious birth defect, the March of Dimes recommends that parents:

* Consult a specialist in maternal-fetal medicine who is specially trained to treat high-risk pregnancies.

* Arrange to give birth in a hospital with a Level III newborn intensive care unit (NICU) staffed and equipped to provide the expert care needed by infants with special needs.

* Discuss the best way to deliver the baby with the doctor; a cesarean section is safer than a vaginal birth for babies with certain birth defects.

* Consult a pediatrician who specializes in the kind of care (for example, cardiac or neurological) that the baby will need after birth.

* Join an organization or volunteer group that can provide support and education about how best to care for the baby’s specific needs.

By Jane E. Brody : NY Times : October 7, 2013

More than 30 years ago, a 37-year-old friend of mine with an unplanned fourth pregnancy was told by her obstetrician that an amniocentesis was “too dangerous” and could cause a miscarriage. She ultimately bore a child severely affected by Down syndrome, which could have been detected with the test.

Today, my friend’s story would have a different trajectory. She would have a series of screening tests, and if the results suggested a high risk of Down syndrome, then an amniocentesis or chorionic villus sampling (C.V.S.) to make the diagnosis. She’d be given the option to abort the pregnancy.

In the future, a woman who decides to continue a Down syndrome pregnancy may also be offered prenatal treatment to temper the developmental harm to the fetus.

Prenatal diagnosis, today a routine part of obstetric care, has made great strides since the mid-1970s and is now on the cusp of further revolutionary developments.

In the nearly four decades since amniocentesis became widely accepted, new techniques have gradually improved the safety and accuracy of prenatal diagnosis. Prenatal tests for more than 800 genetic disorders have been developed. And the number of women who must undergo amniocentesis or C.V.S. has been greatly reduced.

The newest screening test, highly accurate and noninvasive, relies on fetal genetic fragments found in the mother’s blood. Available commercially from four companies, this test is so accurate in detecting Down syndrome that few, if any, affected fetuses are missed, and far fewer women need an invasive procedure to confirm or refute the presence of Down, according to studies in several countries.

The new test, done late in the first trimester of pregnancy, can also detect other genetic diseases, like extra copies of chromosomes 13 and 18, and a missing sex chromosome. It is not yet approved by the Food and Drug Administration, however, and the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology currently recommends it only for women at high risk for having a baby with a chromosomal abnormality.

But any woman can get the new screening test if her doctor orders it and she is willing to pay for it herself, according to Dr. Diana W. Bianchi, a neonatologist and geneticist at Tufts University School of Medicine. Dr. Bianchi said she expects it will soon become routine for all pregnant women because, in addition to its “extraordinary accuracy” in detecting a Down syndrome pregnancy, it can be done earlier than other tests, and reduces costs and the risk of complications.

Down syndrome, which occurs in about one in every 700 births in the United States, is by far the most common chromosomal abnormality. It causes physical and intellectual disabilities that range from mild to severe.

In the past, the decision to undergo an amniocentesis or C.V.S. was based on a woman’s age or genetic history. The older the woman, the greater her risk of bearing a child with genetic defects due to an abnormal number of chromosomes.

It is now standard practice to offer all pregnant women a series of noninvasive screening tests in the first and second trimesters of pregnancy to assess the chances that a fetus has the extra copy of chromosome 21, which causes Down syndrome. It is then up to the woman to decide whether to undergo C.V.S. or an amniocentesis.

Taken together, these older screening tests pick up about 92 percent of cases of Down syndrome but miss 8 percent. And they yield false-positive results incorrectly indicating the presence of Down in about 5 percent of fetuses.

“This means a lot of women are needlessly worried and a lot have amnios that are not medically necessary,” Dr. Bianchi explained at a meeting last December of the March of Dimes.

Amniocentesis is performed between 15 and 20 weeks of gestation and involves inserting a long needle into a woman’s uterus to extract some of the fluid and cells surrounding the fetus. In C.V.S., usually done at 11 weeks gestation, the fetal cell sample is taken from the placenta. The cells are then analyzed for possible genetic defects. There is a small risk of miscarriage associated with both procedures.

But the new tests of fetal DNA from the mother’s blood detect all or nearly all cases of Down syndrome, and they return false-positive results in fewer than 1 percent of cases. Only those with a positive result need a C.V.S. or amniocentesis to confirm a Down syndrome pregnancy, and only about one woman in 1,000 who are tested requires such an invasive procedure to learn that her fetus does not have Down syndrome.

In a recent article in The New England Journal of Medicine, however, Stephanie Morain, a doctoral candidate at Harvard who studies medical ethics, and her co-authors said the fetal DNA tests have some disadvantages. They miss some chromosomal abnormalities detected by standard screening techniques, and they are “not widely covered by insurance.” Prices for the tests range from about $800 to more than $2,000, although some companies offer “introductory pricing” specials at about $200.

The new tests are also not required to meet the strict standards of safety and effectiveness established by the F.D.A., and they are valid only in singleton pregnancies. Nonetheless, tens of thousands of the fetal DNA tests have been performed to date.

The new test requires just a few teaspoons of a pregnant woman’s blood. During pregnancy, a woman’s blood contains cell-free DNA from herself and her unborn baby. On average, Dr. Bianchi said in an interview, at around 10 weeks of gestation, about 10 to 12 percent of the DNA in a woman’s blood will be fetal DNA from the placenta.

Using modern genetic sequencing techniques, the fetal DNA can be rapidly analyzed at a relatively low cost, in part because multiple samples from different women can be examined simultaneously.

As with other screening tests, the new DNA tests are “not diagnostic,” Dr. Lee P. Shulman, a geneticist at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, emphasized. A positive result on the test must always be confirmed by a C.V.S. or amniocentesis. Dr. Bianchi is now most excited by the prospect of treating a Down syndrome fetus before birth to minimize the disorder’s neurological effects. Studies have shown that giving pregnant mice medication that counters fetal oxidative stress results in more normal brain development of pups with Down syndrome.

When prenatal testing reveals that a fetus has a chromosomal defect or some other serious birth defect, the March of Dimes recommends that parents:

* Consult a specialist in maternal-fetal medicine who is specially trained to treat high-risk pregnancies.

* Arrange to give birth in a hospital with a Level III newborn intensive care unit (NICU) staffed and equipped to provide the expert care needed by infants with special needs.

* Discuss the best way to deliver the baby with the doctor; a cesarean section is safer than a vaginal birth for babies with certain birth defects.

* Consult a pediatrician who specializes in the kind of care (for example, cardiac or neurological) that the baby will need after birth.

* Join an organization or volunteer group that can provide support and education about how best to care for the baby’s specific needs.

That Prenatal Visit May Be Months Too Late

By Roni Rabin : NY Times : November 28, 2006

For years, women have had it drummed into them that prenatal care is the key to having a healthy baby, and that they should see a doctor as soon as they know they are pregnant.

But by then, it may already be too late. Public health officials are now encouraging women to make sure they are in optimal health well in advance of a pregnancy to reduce the risk of preventable birth defects and complications. They have recast the message to emphasize not only prenatal care, as they did in the past, but also what they are calling “preconception care.”

The problem, doctors say, is that by the first prenatal visit, a woman is usually 10 to 12 weeks pregnant. “If a birth defect is going to happen, it’s already happened,” said Dr. Peter S. Bernstein, a maternal fetal medicine specialist at Montefiore Medical Center in New York who helped write new government guidelines on preconception care.

For many women, Dr. Bernstein said, “The most important doctor’s visit may be the one that takes place before a pregnancy is conceived.”

The new guidelines, issued by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention last spring, include 10 specific health care recommendations and advise prepregnancy checkups that include screening for diabetes, H.I.V. and obesity; managing chronic medical conditions; reviewing medications that may harm a fetus; and making sure vaccinations are up to date.

Much of the advice directed to women is fairly standard: they should abstain from smoking, alcohol and drugs, and should take prenatal vitamins, including folic acid.

For Diane Jackey, a mother of five from Hempstead, N.Y., maintaining preconception health meant continuing prenatal vitamins between pregnancies, snatching exercise whenever she could and maintaining a balanced diet. “I don’t smoke, and I don’t drink at all,” Ms. Jackey said.

What is new and somewhat controversial about the guidelines is the suggestion that they should apply to women throughout their reproductive years, even when they are not planning pregnancies. (Men should be wary of exposures to toxins that cause birth defects and should avoid sexually transmitted diseases, experts say.)

But while the report was criticized in some quarters for treating all women as though they were eternally “prepregnant,” it also discusses the importance of family planning and child spacing and encourages young people to develop a “reproductive life plan.” Half of all pregnancies in the United States are unplanned, experts say, and preparing for a healthy pregnancy can require behavioral changes that may take months. Even daily supplements of folic acid should ideally be taken for three months before conception.

“It’s not like we have an injection we can give someone” to prepare her for pregnancy, said Dr. Hani Atrash, associate director for program development at the National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities at the disease centers. “Some of the interventions, like weight management, need time to happen. You cannot quit smoking in one day.”

The issue of preconception health has taken on added urgency in recent years because while infant mortality rates were on the decline from 1980 to 2000, the proportion of small and preterm babies increased significantly. And low birth weight, which has been linked to maternal smoking and multiple births, is a leading cause of death and disability for infants.

In 2002, the infant mortality rate in the United States increased for the first time in more than 40 years, to 7.0 deaths per 1,000 live births in 2002 from 6.8 deaths per 1,000 live births in 2001. The rate dropped back to 6.8 per 1,000 in 2003. Blacks are at the highest risk for preterm birth and low birth weights, and their infant mortality rates are more than double that of whites.

Meanwhile, rising obesity rates and the tendency to postpone motherhood mean far more women are overweight when they become pregnant and thus are more likely to have high blood pressure, diabetes or prediabetes, which complicate pregnancy.

“There is no question the No. 1 issue for women in America is their weight,” said Dr. Gary Hankins, who leads the committee on obstetrics practice of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Pre-existing diabetes significantly increases the risk of birth defects, but the risk is virtually eliminated if the disease is controlled before conception, Dr. Hankins said. Obese women who become pregnant face a higher risk of developing gestational diabetes and of having a large baby and a difficult delivery.

While doctors have been recommending preconception care for many years, it has never really caught on. Only one in six health care providers said they had provided preconception care to patients, one study found, and most health plans do not cover it. Medicaid, the government health plan for the poor, often only covers women after they are pregnant.

Rochelle Carr, 31, a Bronx mother, sought preconception counseling because she worried that her asthma medications might harm a developing fetus. Ms. Carr was also concerned because she had suffered a life-threatening pulmonary embolism, or blood clot to the lung, when she was 29.

Ms. Carr’s doctor referred her to a maternal fetal medicine specialist at Montefiore Medical Center. Dr. Ashlesha Dayal reviewed Ms. Carr’s medications and advised her to stop taking an asthma drug linked to birth defects and to start taking folic acid daily.

Once Ms. Carr became pregnant, Dr. Dayal prescribed an anticoagulant because Ms. Carr was at high risk for developing another blood clot. The doctor also explained the risks of taking the anticoagulant. “She really put my mind at ease,” said Ms. Carr, who delivered a healthy baby, Joshua, on Nov. 29, 2005.

Doctors say that planning pregnancies and using reliable contraception are part and parcel of preconception care, and they are encouraging all health providers — not just obstetricians but emergency room doctors, primary care physicians, cardiologists and endocrinologists — to counsel women of childbearing age about the possibility of pregnancy. “What we’re actually talking about,” Dr. Atrash said, “is women’s health.”

By Roni Rabin : NY Times : November 28, 2006

For years, women have had it drummed into them that prenatal care is the key to having a healthy baby, and that they should see a doctor as soon as they know they are pregnant.

But by then, it may already be too late. Public health officials are now encouraging women to make sure they are in optimal health well in advance of a pregnancy to reduce the risk of preventable birth defects and complications. They have recast the message to emphasize not only prenatal care, as they did in the past, but also what they are calling “preconception care.”

The problem, doctors say, is that by the first prenatal visit, a woman is usually 10 to 12 weeks pregnant. “If a birth defect is going to happen, it’s already happened,” said Dr. Peter S. Bernstein, a maternal fetal medicine specialist at Montefiore Medical Center in New York who helped write new government guidelines on preconception care.

For many women, Dr. Bernstein said, “The most important doctor’s visit may be the one that takes place before a pregnancy is conceived.”

The new guidelines, issued by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention last spring, include 10 specific health care recommendations and advise prepregnancy checkups that include screening for diabetes, H.I.V. and obesity; managing chronic medical conditions; reviewing medications that may harm a fetus; and making sure vaccinations are up to date.

Much of the advice directed to women is fairly standard: they should abstain from smoking, alcohol and drugs, and should take prenatal vitamins, including folic acid.

For Diane Jackey, a mother of five from Hempstead, N.Y., maintaining preconception health meant continuing prenatal vitamins between pregnancies, snatching exercise whenever she could and maintaining a balanced diet. “I don’t smoke, and I don’t drink at all,” Ms. Jackey said.

What is new and somewhat controversial about the guidelines is the suggestion that they should apply to women throughout their reproductive years, even when they are not planning pregnancies. (Men should be wary of exposures to toxins that cause birth defects and should avoid sexually transmitted diseases, experts say.)

But while the report was criticized in some quarters for treating all women as though they were eternally “prepregnant,” it also discusses the importance of family planning and child spacing and encourages young people to develop a “reproductive life plan.” Half of all pregnancies in the United States are unplanned, experts say, and preparing for a healthy pregnancy can require behavioral changes that may take months. Even daily supplements of folic acid should ideally be taken for three months before conception.

“It’s not like we have an injection we can give someone” to prepare her for pregnancy, said Dr. Hani Atrash, associate director for program development at the National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities at the disease centers. “Some of the interventions, like weight management, need time to happen. You cannot quit smoking in one day.”

The issue of preconception health has taken on added urgency in recent years because while infant mortality rates were on the decline from 1980 to 2000, the proportion of small and preterm babies increased significantly. And low birth weight, which has been linked to maternal smoking and multiple births, is a leading cause of death and disability for infants.

In 2002, the infant mortality rate in the United States increased for the first time in more than 40 years, to 7.0 deaths per 1,000 live births in 2002 from 6.8 deaths per 1,000 live births in 2001. The rate dropped back to 6.8 per 1,000 in 2003. Blacks are at the highest risk for preterm birth and low birth weights, and their infant mortality rates are more than double that of whites.

Meanwhile, rising obesity rates and the tendency to postpone motherhood mean far more women are overweight when they become pregnant and thus are more likely to have high blood pressure, diabetes or prediabetes, which complicate pregnancy.

“There is no question the No. 1 issue for women in America is their weight,” said Dr. Gary Hankins, who leads the committee on obstetrics practice of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Pre-existing diabetes significantly increases the risk of birth defects, but the risk is virtually eliminated if the disease is controlled before conception, Dr. Hankins said. Obese women who become pregnant face a higher risk of developing gestational diabetes and of having a large baby and a difficult delivery.

While doctors have been recommending preconception care for many years, it has never really caught on. Only one in six health care providers said they had provided preconception care to patients, one study found, and most health plans do not cover it. Medicaid, the government health plan for the poor, often only covers women after they are pregnant.

Rochelle Carr, 31, a Bronx mother, sought preconception counseling because she worried that her asthma medications might harm a developing fetus. Ms. Carr was also concerned because she had suffered a life-threatening pulmonary embolism, or blood clot to the lung, when she was 29.

Ms. Carr’s doctor referred her to a maternal fetal medicine specialist at Montefiore Medical Center. Dr. Ashlesha Dayal reviewed Ms. Carr’s medications and advised her to stop taking an asthma drug linked to birth defects and to start taking folic acid daily.

Once Ms. Carr became pregnant, Dr. Dayal prescribed an anticoagulant because Ms. Carr was at high risk for developing another blood clot. The doctor also explained the risks of taking the anticoagulant. “She really put my mind at ease,” said Ms. Carr, who delivered a healthy baby, Joshua, on Nov. 29, 2005.

Doctors say that planning pregnancies and using reliable contraception are part and parcel of preconception care, and they are encouraging all health providers — not just obstetricians but emergency room doctors, primary care physicians, cardiologists and endocrinologists — to counsel women of childbearing age about the possibility of pregnancy. “What we’re actually talking about,” Dr. Atrash said, “is women’s health.”

Prenatal Tests:

More Information, Less Risk

By Jane E. Brody : NY Times : July 27, 2004

At age 35, Angelica decided to start a family. Knowing that her age was associated with an increased risk of bearing a child with a chromosomal defect, at 18 weeks of pregnancy she underwent amniocentesis, an analysis of fetal cells from amniotic fluid extracted by a large needle inserted into the womb through the abdomen.

The test revealed a fetus with the extra chromosome that causes Down syndrome, and a distraught Angelica chose to end the pregnancy.

A year and a half later she was pregnant again. This time she did not want to wait until the fourth month to find out if the fetus had a chromosomal problem, so at 10 weeks she underwent chorionic villus sampling, or C.V.S., an analysis of fetal cells extracted from the placenta. No chromosomal abnormality was found, and six and a half months later she gave birth to a healthy boy.

Now 39, Angelica is pregnant once more. Based on her age, her risk of bearing a child with Down syndrome is 1 in 80. But this time there is to be no amniocentesis or C.V.S., for both tests are costly and invasive, with a small but not insignificant risk of miscarriage or fetal damage.

Instead, she underwent a series of simple blood tests plus a detailed sonogram at 12 weeks. These tests revealed that there was only a 1 in 981 chance that her child would have a chromosomal abnormality or neural tube defect, about the same risk as that faced by a woman of 29.

Measuring the Hazards

More women are having babies later in their reproductive lives, at ages when the chance of conceiving a child with a major chromosomal defect rises precipitously. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the American College of Medical Genetics recommend that prenatal diagnosis by amniocentesis or C.V.S. be offered to all pregnant women 35 and older, as well as to younger women with positive results on screening blood tests.

But using age as the sole criterion has resulted in rising numbers of the invasive and expensive tests, as well as an increase in miscarriages of what are often hard-won pregnancies among older women. And so experts in obstetrics and fetal medicine have devised a series of simple blood tests that, when factored together with a woman's age and often with the results of a sonogram, are greatly reducing the numbers of women undergoing the more involved tests without compromising the chances of detecting serious fetal abnormalities.

A new study, published in the June issue of Obstetrics & Gynecology, illustrates this trend. According to the study, the number of women in Connecticut who had amniocentesis or C.V.S. declined 50 percent from 1991 to 2002, while the share of Down syndrome births did not increase even though more women were becoming pregnant at ''an advanced maternal age.''

Dr. Peter A. Benn, a geneticist at the University of Connecticut Health Center in Farmington, where the study was done, said fewer women had the procedures because more of them had blood tests and sonograms to screen for abnormalities.

Before September 1991, Dr. Benn said, women at his center were identified as facing a high risk of a chromosomally abnormal fetus based on their age or family history, or based on their having a low level of alpha-fetoprotein, a substance in blood. That month, though, the center began screening for Down syndrome in the second trimester of pregnancy using maternal blood levels of three substances -- alpha-fetoprotein plus human chorionic gonadotropin and estriol -- and combining those levels with the woman's age to obtain a risk estimate.

In 1996, structural abnormalities visible on a sonogram were used to modify the blood-test risk estimate. In 1999, the center added a fourth substance in blood, inhibin-A, to the risk calculation.

In 1991, there were 48,566 live births there, with 6,082, or 12 percent, to women 35 or older at delivery. In 2002, the number of live births declined to 41,690, but the number born to women 35 and older rose to 9,040, 21.7 percent of the total.

Despite the 58 percent increase in the share of women 35 and older at delivery, referrals to the center for an invasive test based on age alone declined 68 percent as those receiving the prenatal blood and ultrasound tests grew.

''Using age as the sole criterion for an invasive test is not an efficient use of resources,'' Dr. Benn said in an interview. He added that reducing the number of invasive tests did not result in a failure to detect affected pregnancies.

''We're getting at least as many, if not more,'' he said, at a much lower cost and with minimal trauma to the woman and her unborn child. An amniocentesis or C.V.S. costs $2,000 or more, while the blood tests and sonogram cost about $300.

In some areas of the country, blood tests plus the sonogram, which among other things measures a translucent area at the back of the fetal neck, are being performed in the first trimester, as was done in Angelica's case. This approach relieves overall maternal anxiety, because the overwhelming majority of tested pregnancies give a low-risk result. It also permits abortion of an affected pregnancy before other people know the woman is pregnant.

First-trimester screening has been used in Europe for several years but is only now becoming part of American obstetrical practice, Dr. Benn said.

Understanding the Data

Doctors, midwives and nurses can estimate the risk of having a baby with chromosomal abnormalities, but each woman must decide herself what to do with that information. In a report in the May/June issue of The Journal of Midwifery & Women's Health, Dr. Elena A. Gates, an obstetrician-gynecologist at the University of California, San Francisco, explored the factors influencing a woman's perception of risk.

''We toss numbers around but don't appreciate the difficulties people have in understanding the figures,'' Dr. Gates said in an interview.

She added that among the factors influencing a woman's perception of risk are her ideas ''when she walks in the door -- what she's read or heard from her friends, and how familiar she is with the condition, whether a friend, neighbor or family member had an affected child or she had a prior affected pregnancy.''

Also important, she said, is how the information is presented. ''Do you say you have a 5 percent chance of Down syndrome,'' she asked, ''or a 95 percent chance that the baby is not affected?''

In reviewing studies of how women perceive risk, Dr. Gates said, she discovered that it was much harder for most women to understand greater or lesser risk when proportions were used -- say, 1 in 384 versus 1 in 112 -- than when the same risks were expressed as a rate, like 2.6 per 1,000 versus 8.9 per 1,000.

It takes time to explain risk estimates to pregnant women and their partners, and to be sure they grasp the full meaning of the numbers within the context of personal experience and knowledge.

''Providers should bear in mind that a woman's individual values are much more important to optimizing decision-making than are her risks of any particular outcome,'' Dr. Gates concluded.

But she added a cautionary note: because of economics, lack of access to doctors and clinics, or simply a delay in receiving care, only about half of all pregnant women in this country receive prenatal diagnostic tests early enough to abort an affected pregnancy or prepare for the birth of an affected child.

More Information, Less Risk

By Jane E. Brody : NY Times : July 27, 2004

At age 35, Angelica decided to start a family. Knowing that her age was associated with an increased risk of bearing a child with a chromosomal defect, at 18 weeks of pregnancy she underwent amniocentesis, an analysis of fetal cells from amniotic fluid extracted by a large needle inserted into the womb through the abdomen.

The test revealed a fetus with the extra chromosome that causes Down syndrome, and a distraught Angelica chose to end the pregnancy.

A year and a half later she was pregnant again. This time she did not want to wait until the fourth month to find out if the fetus had a chromosomal problem, so at 10 weeks she underwent chorionic villus sampling, or C.V.S., an analysis of fetal cells extracted from the placenta. No chromosomal abnormality was found, and six and a half months later she gave birth to a healthy boy.

Now 39, Angelica is pregnant once more. Based on her age, her risk of bearing a child with Down syndrome is 1 in 80. But this time there is to be no amniocentesis or C.V.S., for both tests are costly and invasive, with a small but not insignificant risk of miscarriage or fetal damage.

Instead, she underwent a series of simple blood tests plus a detailed sonogram at 12 weeks. These tests revealed that there was only a 1 in 981 chance that her child would have a chromosomal abnormality or neural tube defect, about the same risk as that faced by a woman of 29.

Measuring the Hazards

More women are having babies later in their reproductive lives, at ages when the chance of conceiving a child with a major chromosomal defect rises precipitously. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the American College of Medical Genetics recommend that prenatal diagnosis by amniocentesis or C.V.S. be offered to all pregnant women 35 and older, as well as to younger women with positive results on screening blood tests.

But using age as the sole criterion has resulted in rising numbers of the invasive and expensive tests, as well as an increase in miscarriages of what are often hard-won pregnancies among older women. And so experts in obstetrics and fetal medicine have devised a series of simple blood tests that, when factored together with a woman's age and often with the results of a sonogram, are greatly reducing the numbers of women undergoing the more involved tests without compromising the chances of detecting serious fetal abnormalities.

A new study, published in the June issue of Obstetrics & Gynecology, illustrates this trend. According to the study, the number of women in Connecticut who had amniocentesis or C.V.S. declined 50 percent from 1991 to 2002, while the share of Down syndrome births did not increase even though more women were becoming pregnant at ''an advanced maternal age.''

Dr. Peter A. Benn, a geneticist at the University of Connecticut Health Center in Farmington, where the study was done, said fewer women had the procedures because more of them had blood tests and sonograms to screen for abnormalities.

Before September 1991, Dr. Benn said, women at his center were identified as facing a high risk of a chromosomally abnormal fetus based on their age or family history, or based on their having a low level of alpha-fetoprotein, a substance in blood. That month, though, the center began screening for Down syndrome in the second trimester of pregnancy using maternal blood levels of three substances -- alpha-fetoprotein plus human chorionic gonadotropin and estriol -- and combining those levels with the woman's age to obtain a risk estimate.

In 1996, structural abnormalities visible on a sonogram were used to modify the blood-test risk estimate. In 1999, the center added a fourth substance in blood, inhibin-A, to the risk calculation.

In 1991, there were 48,566 live births there, with 6,082, or 12 percent, to women 35 or older at delivery. In 2002, the number of live births declined to 41,690, but the number born to women 35 and older rose to 9,040, 21.7 percent of the total.

Despite the 58 percent increase in the share of women 35 and older at delivery, referrals to the center for an invasive test based on age alone declined 68 percent as those receiving the prenatal blood and ultrasound tests grew.

''Using age as the sole criterion for an invasive test is not an efficient use of resources,'' Dr. Benn said in an interview. He added that reducing the number of invasive tests did not result in a failure to detect affected pregnancies.

''We're getting at least as many, if not more,'' he said, at a much lower cost and with minimal trauma to the woman and her unborn child. An amniocentesis or C.V.S. costs $2,000 or more, while the blood tests and sonogram cost about $300.

In some areas of the country, blood tests plus the sonogram, which among other things measures a translucent area at the back of the fetal neck, are being performed in the first trimester, as was done in Angelica's case. This approach relieves overall maternal anxiety, because the overwhelming majority of tested pregnancies give a low-risk result. It also permits abortion of an affected pregnancy before other people know the woman is pregnant.

First-trimester screening has been used in Europe for several years but is only now becoming part of American obstetrical practice, Dr. Benn said.

Understanding the Data