- RETIREMENT ANNOUNCEMENT

- HOME PAGE

- "MYCHART" the new patient portal

- BELMONT MEDICAL ASSOCIATES

- MOUNT AUBURN HOSPITAL

- EMERGENCIES

- PRACTICE PHILOSOPHY

- MY RESUME

- TELEMEDICINE CONSULTATION

- CONTACT ME

- LAB RESULTS

- ePRESCRIPTIONS

- eREFERRALS

- RECORD RELEASE

- MEDICAL SCRIBE

- PHYSICIAN ASSISTANT (PA)

- Medicare Annual Wellness Visit

- Case management/Social work

- Quality Care Measures

- Emergency closing notice

- FEEDBACK

- Talking to your doctor

- Choosing..... and losing a doctor

- INDEX A - Z

- ALLERGIC REACTIONS

- Alternative Medicine

- Alzheimer's Disease

- Bladder Problems

- Blood disorders

- Cancer Concerns

- GENETIC TESTING FOR HEREDITARY CANCER

- Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

- Controversial Concerns

- CPR : Learn and save a life

- CRP : Inflammatory marker

- Diabetes Management

- Dizziness, Vertigo,Tinnitus and Hearing Loss

- EXERCISE

- FEMALE HEALTH

-

GASTROINTESTINAL topics

- Appendicitis

- BRAT diet

- Celiac Disease or Sprue

- Crohn's Disease

- Gastroenterologists for Colon Cancer Screening

- Colonoscopy PREP

- Constipation

- Gluten sensitivity, but not celiac disease

- Heartburn and GERD

- Hemorrhoids and Anal fissure

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- NASH : Non Alcoholic Steato Hepatitis

- FEET PROBLEMS

- HEART RELATED topics

-

INFECTIOUS DISEASES

- Antibiotic Resistance

- Cat bites >

- Clostridia difficile infection - the "antibiotic associated germ"

- CORONA VIRUS

- Dengue Fever and Chikungunya Fever

- Food borne illnesses

- Shingles Vaccine

- Hepatitis B

- Hepatitis C

- Herpes

- Influenza

- Helicobacter pylori - the "ulcer germ"

- HIV Screening

- Lyme and other tick borne diseases

- Measles

- Meningitis

- MRSA (Staph infection)

- Norovirus

- Sexually Transmitted Diseases

- Shingles (Herpes Zoster)

- Sinusitis

- West Nile Virus

- Whooping Cough (Pertussis)

- Zika virus and pregnancy

- INSURANCE related topics

- KIDNEY STONES

- LEG CRAMPS

- LIBRARY for patients

- LIFE DECISIONS

- MALE HEALTH

- Medication/Drug side effects

- MEDICAL MARIJUANA

- MENTAL HEALTH

- Miscellaneous Articles

-

NUTRITION - EXERCISE - WEIGHT

- Cholesterol : New guidelines for treatment

- Advice to lower your cholesterol

- Cholesterol : Control

- Cholesterol : Raising your HDL Level

- Exercise

- Food : Making Smart Choices

- Food : Making Poor Choices

- Food : Grape Fruit and Drug Interaction

- Food : Vitamins, Minerals and Supplements

- Omega 3 fatty acids

- Vitamin B12 deficiency

- Vitamin D

- Weight Loss

- ORTHOPEDICS

- PAIN

- PATIENTS' RIGHTS

- SKIN

- SLEEP

- SMOKING

- STROKE

- THYROID

- SUBSTANCE ABUSE

- Travel and Vaccination

- TREMOR

- Warfarin Anticoagulation

- OTHER STUFF FOLLOWS

- Fact or Opinion?

- Hippocratic Oath

- FREE ADVICE.......for what its worth!

- LAUGHTER.....is the best medicine

- Physicians Pet Peeves

- PHOTO ALBUM - its not all work!

- Cape Town, South Africa

- Tribute page

- The 100 Club

- Free Wi-Fi

ORTHOPEDIC TOPICS

For Tendon Pain, Think Beyond the Needle

By Jane E. Brody : NY Times : February 28, 2011

Two time-honored remedies for injured tendons seem to be falling on their faces in well-designed clinical trials.

The first, corticosteroid injections into the injured tendon, has been shown to provide only short-term relief, sometimes with poorer long-term results than doing nothing at all.

The second, resting the injured joint, is supposed to prevent matters from getting worse. But it may also fail to make them any better.

Rather, working the joint in a way that doesn’t aggravate the injury but strengthens supporting tissues and stimulates blood flow to the painful area may promote healing faster than “a tincture of time.”

And researchers (supported by my own experience with an injured tendon, as well as that of a friend) suggest that some counterintuitive remedies may work just as well or better.

A review of 41 “high-quality” studies involving 2,672 patients, published in November in The Lancet, revealed only short-lived benefit from corticosteroid injections. For the very common problem of tennis elbow, injections of platelet-rich plasma derived from patients’ own blood had better long-term results.

Still, the authors, from the University of Queensland and Griffith University in Australia, emphasized the need for more and better clinical research to determine which among the many suggested remedies works best for treating different tendons.

My own problem was precipitated one autumn by eight days of pulling a heavy suitcase through six airports. My shoulder hurt nearly all the time (not a happy circumstance for a daily swimmer), and trying to retrieve something even slightly behind me produced a stabbing pain. Diagnosis: tendinitis and arthritis. Treatment: rest and physical therapy.

Two months of physical therapy did help somewhat, as did avoiding motions that caused acute pain. The therapist had some useful tips on adjusting my swimming stroke to minimize stress on the tendon while the injury gradually began to heal.

The following spring, although I still had some pain and feared a relapse, I attacked my garden with a vengeance. Much to my surprise, I was able to do heavy-duty digging and lugging without shoulder pain.

Could the intense workout and perhaps the increased blood flow to my shoulder have enhanced my recovery? A friend, Richard Erde, had an instructive experience.

An avid tennis player at 70, he began having twinges in his right shoulder while playing. Soon, simple motions like slipping out of a shirt sleeve caused serious pain. The diagnosis, based on a physical exam, was injury of the tendon that attaches the biceps muscle of his upper arm to the bones of the shoulder’s rotator cuff.

He was advised to see a rheumatologist, who declined to do a corticosteroid injection and instead recommended physical therapy and rest.

“I stopped playing tennis for a month, and it didn’t help at all,” Mr. Erde told me. “The physical therapist found I had very poor range of motion and had me do a variety of exercises, which improved my flexibility and reduced the pain somewhat.” After two months, he stopped the therapy.

Then several weeks ago, after watching the Australian Open, he thought he should do more to strengthen his arm and shoulder muscles and decided to try playing tennis more vigorously. “The pain started to drop off dramatically,” he said, “and in just 10 days the pain had eased more than 90 percent.”

A Frustrating Injury

Tendinopathies, as these injuries are called, are particularly vexing orthopedic problems that remain poorly understood despite their frequency. “Tendinitis” is a misnomer: rarely are there signs of inflammation, which no doubt accounts for the lack of lasting improvement with steroid shots and anti-inflammatory drugs. They may relieve pain temporarily, but don’t cure the problem.

The underlying pathology of tendinopathies is still a mystery. Even when patients recover, their tendons may continue to look awful, say therapists who do imaging studies. Without a better understanding of the actual causes of tendon pain, it’s hard to develop rational treatments, and even the best specialists may be reduced to trial and error. What works best for one tendon — or one patient — may do little or nothing for another.

Most tendinopathies are precipitated by overuse and commonly afflict overzealous athletes, amateur and professional alike. With or without treatment, they usually take a long time to heal — many months, even a year or more. They can be frustrating and often costly, especially for professional athletes and physically active people like me and Mr. Erde.

In a commentary accompanying the Lancet report, Alexander Scott and Karim M. Khan of the University of British Columbia noted that although “corticosteroid injection does not impair recovery of shoulder tendinopathy, patients should be advised that evidence for even short-term benefits at the shoulder is limited.” Like the Australian reviewers, the commentators concluded that “specific exercise therapy might produce more cures at 6 and 12 months than one or more corticosteroid injections.”

Treatments to Try

Now the question is: What kind of physical therapy gives the best results?

Most therapists prescribe eccentric exercises, which involve muscle contractions as the muscle fibers lengthen (for example, when a hand-held weight is lowered from the waist to the thigh). Eccentric exercises must be performed in a controlled manner; uncontrolled eccentric contractions are a common cause of injuries like groin pulls or hamstring strains.

Marilyn Moffat, professor of physical therapy at New York University and president of the World Confederation for Physical Therapy, prefers “very protective” isometric exercises, at least at the outset of treatment until the tendon injury begins to heal. These exercises involve no movement at all, allowing muscles to contract without producing pain. For example, in treating shoulder tendinopathy, she said in an interview, the patient would push the fists against a wall with upper arms against the body and elbows bent at 90 degrees.

In another exercise, the patient sits holding one end of a dense elastic Thera-Band in each hand and, with thumbs up, upper arms at the sides and elbows bent at 90 degrees, tries to pull the hands apart.

“The stronger the shoulder muscles are when the tendinopathy calms down, the better shape the shoulder is in to take over movement without further injury,” Dr. Moffat said. “You don’t want the muscles to weaken, which is what happens when you rest and do nothing. That leaves you vulnerable to further injury.”

Do Cortisone Shots Actually Make Things Worse?

By Gretchen Reynolds : NY Times : October 27, 2010

In the late 1940s, the steroid cortisone, an anti-inflammatory drug, was first synthesized and hailed as a landmark. It soon became a safe, reliable means to treat the pain and inflammation associated with sports injuries (as well as other conditions). Cortisone shots became one of the preferred treatments for overuse injuries of tendons, like tennis elbow or an aching Achilles, which had been notoriously resistant to treatment. The shots were quite effective, providing rapid relief of pain.

Then came the earliest clinical trials, including one, published in 1954, that raised incipient doubts about cortisone’s powers. In that early experiment, more than half the patients who received a cortisone shot for tennis elbow or other tendon pain suffered a relapse of the injury within six months.

But that cautionary experiment and others didn’t slow the ascent of cortisone (also known as corticosteroids). It had such a magical, immediate effect against pain. Today cortisone shots remain a standard, much-requested treatment for tennis elbow and other tendon problems.

But a major new review article, published last Friday in The Lancet, should revive and intensify the doubts about cortisone’s efficacy. The review examined the results of nearly four dozen randomized trials, which enrolled thousands of people with tendon injuries, particularly tennis elbow, but also shoulder and Achilles-tendon pain. The reviewers determined that, for most of those who suffered from tennis elbow, cortisone injections did, as promised, bring fast and significant pain relief, compared with doing nothing or following a regimen of physical therapy. The pain relief could last for weeks.

But when the patients were re-examined at 6 and 12 months, the results were substantially different. Overall, people who received cortisone shots had a much lower rate of full recovery than those who did nothing or who underwent physical therapy. They also had a 63 percent higher risk of relapse than people who adopted the time-honored wait-and-see approach. The evidence for cortisone as a treatment for other aching tendons, like sore shoulders and Achilles-tendon pain, was slight and conflicting, the review found. But in terms of tennis elbow, the shots seemed to actually be counterproductive. As Bill Vicenzino, Ph.D., the chairman of sports physiotherapy at the University of Queensland in Australia and senior author of the review, said in an e-mail response to questions, “There is a tendency” among tennis-elbow sufferers “for the majority (70-90 percent) of those following a wait-and-see policy to get better” after six months to a year. But “this is not the case” for those getting cortisone shots, he wrote. They “tend to lag behind significantly at those time frames.” In other words, in some way, the cortisone shots impede full recovery, and compared with those ‘‘adopting a wait-and-see policy,” those getting the shots “are worse off.” Those people receiving multiple injections may be at particularly high risk for continuing damage. In one study that the researchers reviewed, “an average of four injections resulted in a 57 percent worse outcome when compared to one injection,” Dr. Vicenzino said.

Why cortisone shots should slow the healing of tennis elbow is a good question. An even better one, though, is why they help in the first place. For many years it was widely believed that tendon-overuse injuries were caused by inflammation, said Karim Khan, M.D., Ph.D., a professor at the School of Human Kinetics at the University of British Columbia and the co-author of a commentary in The Lancet accompanying the new review article. The injuries were, as a group, given the name tendinitis, since the suffix “-itis” means inflammation. Cortisone is an anti-inflammatory medication. Using it against an inflammation injury was logical.

But in the decades since, numerous studies have shown, persuasively, that these overuse injuries do not involve inflammation. When animal or human tissues from these types of injuries are examined, they do not contain the usual biochemical markers of inflammation. Instead, the injury seems to be degenerative. The fibers within the tendons fray. Today the injuries usually are referred to as tendinopathies, or diseased tendons.

Why then does a cortisone shot, an anti-inflammatory, work in the short term in noninflammatory injuries, providing undeniable if ephemeral pain relief? The injections seem to have “an effect on the neural receptors” involved in creating the pain in the sore tendon, Dr. Khan said. “They change the pain biology in the short term.” But, he said, cortisone shots do “not heal the structural damage” underlying the pain. Instead, they actually “impede the structural healing.”

Still, relief of pain might be a sufficient reason to champion the injections, if the pain “were severe,” Dr. Khan said. “But it’s not.” The pain associated with tendinopathies tends to fall somewhere around a 7 or so on a 10-point scale of pain. “It’s not insignificant, but it’s not kidney stones.”

So the question of whether cortisone shots still make sense as a treatment for tendinopathies, especially tennis elbow, depends, Dr. Khan said, on how you choose “to balance short-term pain relief versus the likelihood” of longer-term negative outcomes. In other words, is reducing soreness now worth an increased risk of delayed healing and possible relapse within the year?

Some people, including physicians, may decide that the answer remains yes. There will always be a longing for a magical pill, the quick fix, especially when the other widely accepted and studied alternatives for treating sore tendons are to do nothing or, more onerous to some people, to rigorously exercise the sore joint during physical therapy. But if he were to dispense advice based on his findings and that of his colleagues’ systematic review, Dr. Vincenzino said, he would suggest that athletes with tennis elbow (and possibly other tendinopathies) think not just once or twice about the wisdom of cortisone shots but “three or four times.”

As Sports Medicine Surges, Hope and Hype Outpace Proven Treatments

By Gina Kolata : NY Times : September 4, 2011

Until she tore her hamstring a year and a half ago, Tina Basle ran marathons. Since then, she has been on a desperate search for a cure.

It took her from doctor to doctor, cost her thousands of dollars and led her to try nearly everything sports medicine has to offer — an M.R.I. to show the extent of the injury, physical therapy that included ultrasound and laser therapy, strength training, an injection of platelet-rich plasma (or P.R.P.), a cortisone shot, another cortisone shot.

Finally, in February, she gave up.

“I decided this is never going to heal, so let’s get on with it,” she said.

And so Ms. Basle, a 44-year-old digital media consultant who lives in Manhattan, started running anyway. She has lost a lot of speed and endurance. And, she added, “the stupid hamstring is really no better.”

Medical experts say her tale of multiple futile treatments is all too familiar and points to growing problems in sports medicine, a medical subspecialty that has been experiencing explosive growth. Part of the field’s popularity, among patients and doctors alike, stems from the fact that celebrity athletes, desperate to get back to playing after an injury, have been trying unproven treatments, giving the procedures a sort of star appeal.

But now researchers are questioning many of the procedures, including new ones that often have no rigorous studies to back them up. “Everyone wants to get into sports medicine,” said Dr. James Andrews, a sports medicine orthopedist in Gulf Breeze, Fla., and president-elect of the American Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine.

Doctors love the specialty and can join it with as little as a year of training after their residency, as compared with the more typical two to four years for other specialty training. They see a large group of patients eager for treatment, ranging from competitive athletes to casual exercisers to retirees spending their time on the golf course or tennis court.

The problem is that most sports injuries, including tears of the hamstring ligament like Ms. Basle’s, have no established treatments.

Of course, some remedies for certain injuries do work: putting a cast on a broken bone or operating to repair a torn Achilles tendon. But patients whose injuries have no effective treatment often do not know that medicine has nothing to offer. And many expect cures.

“They watch ‘Grey’s Anatomy’ and think we can do anything,” said Dr. Raymond Monto, a sports medicine orthopedist in West Tisbury, Mass. “And to a certain extent, we allow that.”

Added to that is the effect of sports stars and their doctors. Patients “see a high-profile athlete and say, ‘I want you to do it exactly the same way their doctor did it,’ ” said Dr. Edward McDevitt, an orthopedist in Arnold, Md., who specializes in sports medicine.

The result is therapies that are unproven, possibly worthless or even harmful. There is surgery, like a popular operation that shaves the hip bone to prevent arthritis, that may not work. There are treatments, like steroid injections for injured tendons or taping a sprained ankle, that can slow the healing process. And there are fads, like one of Ms. Basle’s treatments, P.R.P., that soar in popularity while experts debate whether they help.

All this leads Dr. Andrew Green, a shoulder orthopedist at Brown University, to ask, “Is sports medicine a science, something that really pays attention to evidence? Or is it a boutique industry where you have a product and sell it?”

“For a lot of people it is a boutique business,” he said. “But are you still a doctor if you do that?”

A Theory Becomes a Fad

If ever anyone wanted to know how untested sports medicine treatments come into use, they would need only look at platelet-rich plasma, medical experts say. They joke that it is the perfect example of what is a tried-and-true path to popularizing a new treatment. It is what Dr. John Bergfeld, an orthopedic sports medicine specialist at the Cleveland Clinic, calls the Orthopedic Triad: famous athlete, famous doctor, untested treatment.

While there are no official statistics on P.R.P. treatment, all agree that it has exploded on the scene, propelled by testimonials from celebrity athletes.

Part of its appeal was that it made sense. Blood contains platelets that secrete growth factors that, in turn, can help tissue heal. So if a patient’s own platelets are injected into the injury site, they might speed recovery. And since it is the patient’s own platelets, the treatment is unlikely to be harmful.

It is easy to extract platelets. A doctor spins a tube of a patient’s blood in a centrifuge and then removes the middle layer of cells. Those are the platelets.

The claims by athletes and their doctors that brought the treatment to the fore began in the winter of 2009. Two leading football players for the Pittsburgh Steelers — Hines Ward, who sprained a ligament in his knee, and Troy Polamalu, who strained his calf — had P.R.P., recovered quickly and went on to play in the Super Bowl.

Earlier that year, a doctor for a pitcher for the Los Angeles Dodgers, Takashi Saito, said P.R.P. let the pitcher avoid surgery, which would have put him out of commission for about a year. Soon afterward, Tiger Woods reported that he had had four P.R.P. injections after knee surgery.

His doctor, Anthony Galea, who was later investigated for providing performance enhancing drugs to athletes, told The New York Times in December 2009 that within two days after his first treatment, Woods sent him a text. “He said he couldn’t believe how good he felt,” Dr. Galea said. “He’d joke and say, ‘I can jump on the kitchen table.’ ”

Having an athlete report that a treatment worked “is almost like direct-to-consumer advertising,” said Dr. Fred Azur, a sports medicine orthopedist in Memphis.

Of course, researchers say, testimonials from athletes and their doctors are a far cry from credible evidence. Most injuries eventually get better on their own, so if a patient has a treatment and then gets better, would the person have gotten better at the same time anyway? Or did the treatment actually slow the healing process? There is no way to know without a study that compares people who were randomly assigned to have a treatment with those who were randomly assigned not to have it.

But testimonials, especially from celebrities, had an effect.

Patients began asking for the treatment, and sports medicine doctors responded, offering it to speed healing of tissue and muscle injuries, mend broken bones and even help with arthritis.

(This reporter tried P.R.P. in 2009 for a torn hamstring and wrote in an article about the experience that it was impossible to know if it helped; her hamstring eventually healed.)

The number of commercially available kits for obtaining the platelet-rich plasma in a doctor’s office more than doubled, to 16 from six, in the past five years. Some journals devoted entire issues to the treatment, even though most of these papers fall far short of scientific rigor. Interest among orthopedists is so intense that the orthopedists’ association devoted a daylong session to the procedure before its annual meeting, something the group had never done before.

Prices varied widely from hundreds to thousands of dollars per injection. The cost of the equipment — tubing, test tubes — is about $150 to $200. The rest goes to the doctor and the hospital.

If an injury fails to heal, doctors often inject again and again. Insurers usually do not pay, so patients, like Ms. Basle, pay out of their own pocket — she paid $1,500 for an injection.

P.R.P. has gotten so popular, in fact, that there is sort of a price war. In some places, doctors who were charging more than $1,000 two years ago charge about $500 today.

In the meantime, sales representatives from equipment makers urge doctors to use it, telling them, said Dr. Marc Schneider, a sports medicine orthopedist in Cleveland, that “there is no downside.”

But, Dr. Schneider asked, “is there an upside?”

Those who say no to requests for the treatment often lose patients.

“Patients come in and say, ‘I want the same thing that Tiger Woods had,’ ” said Dr. McDevitt, the sports medicine orthopedist in Maryland. “I say, ‘It really hasn’t been proven.’ And they say, ‘Well, I don’t care.’ ”

And when he refuses to provide the treatment to patients, Dr. McDevitt adds, “They usually say: ‘No offense, Doctor. You seem like a nice guy, but I will go to see one of the many, many other doctors who will do it.’ ”

Conflicting Studies

As the editor of a newsletter put out by the orthopedics society, Dr. S. Terry Canale wanted to give doctors some guidance about P.R.P. There were lots of studies, but most were not rigorous, Dr. Canale said, and they came to contradictory conclusions. To further complicate matters, there were four different ways of preparing the treatment, and doctors asked if the different results reflected different preparations.

“It went on and on,” Dr. Canale said. “There was no obvious conclusion.”

Some of the best studies, though, were disappointing. For example, one found that the treatment was no better than saline injections for people with Achilles tendinopathy, a painful injury that often afflicts athletes like runners or tennis players and resists treatment.

Maybe, some said, the problem is that P.R.P. diffuses after it is injected.

Dr. Scott Rodeo of the Hospital for Special Surgery in New York addressed that in a new study. His patients had torn their rotator cuffs, a tendon in the shoulder, a painful injury affecting tennis players and swimmers, among others.

During surgery to sew the tendon together, Dr. Rodeo added P.R.P. directly to the injury, embedding it in a fibrin matrix that, he said, “is sort of like chewing gum” to ensure it stayed in place. The procedure did not help.

There was one rigorous study — of tennis elbow — that did have a positive result. But it compared P.R.P. with cortisone injections, which can impede healing. Critics said the treatment should have been compared with saline injections, which could serve as a placebo. A new study comparing it with saline found that it was no better than the salt water.

In February — when some of these studies were released, and others were still under way — Dr. Canale decided it was time to try to sort things out. He invited about 50 leading experts on P.R.P. to meet, review the data on the treatment and reach some sort of consensus on whether it worked.

They included Dr. Allan Mishra, an orthopedist in private practice in Menlo Park, Calif., who is supported by and gets royalties from one of the P.R.P. equipment makers, Biomet, and is on the board of directors and owns stock in another company, BioParadox, which is exploring the treatment for cardiovascular disease.

Dr. Mishra says more research is needed but offers the treatment for a variety of injuries. His Web page includes a TV news video that claims P.R.P. cured a Stanford football player, James McGillicuddy, with a torn knee tendon. On the program, Dr. Mishra says that, in general, 90 percent of the patients he treats “get better and stay better” after the treatment.

Dr. Canale, who says he receives no support from the P.R.P. industry, said: “The bottom line is that most think it works. The operative word is ‘think.’ They don’t know if it works. They have a feeling it does.”

Dr. Rodeo, who also reports having no conflicts of interest, said he understood that response. “Unfortunately in our field, there often is acceptance and use before there is data,” he said.

The Next Big Thing?

As orthopedists and other sports medicine doctors argue about this particular treatment, another popular treatment is forming. It leapt to the public and medical world’s attention this year when Bartolo Colon, a pitcher for the New York Yankees, made an astonishing comeback from elbow injuries and a torn rotator cuff that had plagued him for years and had kept him from pitching for all of 2010.

In May, Mr. Colon and his doctor, Joseph R. Purita, an orthopedic surgeon in Boca Raton, Fla., reported that Mr. Colon was treated with P.R.P. and “stem cells” — his own fat and bone marrow cells, injected into his shoulder and elbow. Dr. Purita worked with the Harvest Technologies Corporation, a Massachusetts company that also supplies equipment for P.R.P.

The opening scenes seem familiar to those who followed the saga of P.R.P.

Once again, there is a rationale behind the treatment, said Rocky Tuan, director of the Center for Cellular and Molecular Engineering at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center.

The reasoning began with questions about why P.R.P. is not clearly effective. The problem may be that growth factors released from platelets need cells that can respond. But most tissues in joints and tendons have very few cells.

“That’s where stem cells come in,” Dr. Tuan said. Fat and bone marrow contain stem cells that might grow into joint or tendon if they were placed in the right environment. And if a patient also gets an injection of P.R.P., a tendon or joint might actually heal.

The key word, of course, is “might.”

For now, Dr. Tuan said, “no systematic study has been done.”

By Gina Kolata : NY Times : September 4, 2011

Until she tore her hamstring a year and a half ago, Tina Basle ran marathons. Since then, she has been on a desperate search for a cure.

It took her from doctor to doctor, cost her thousands of dollars and led her to try nearly everything sports medicine has to offer — an M.R.I. to show the extent of the injury, physical therapy that included ultrasound and laser therapy, strength training, an injection of platelet-rich plasma (or P.R.P.), a cortisone shot, another cortisone shot.

Finally, in February, she gave up.

“I decided this is never going to heal, so let’s get on with it,” she said.

And so Ms. Basle, a 44-year-old digital media consultant who lives in Manhattan, started running anyway. She has lost a lot of speed and endurance. And, she added, “the stupid hamstring is really no better.”

Medical experts say her tale of multiple futile treatments is all too familiar and points to growing problems in sports medicine, a medical subspecialty that has been experiencing explosive growth. Part of the field’s popularity, among patients and doctors alike, stems from the fact that celebrity athletes, desperate to get back to playing after an injury, have been trying unproven treatments, giving the procedures a sort of star appeal.

But now researchers are questioning many of the procedures, including new ones that often have no rigorous studies to back them up. “Everyone wants to get into sports medicine,” said Dr. James Andrews, a sports medicine orthopedist in Gulf Breeze, Fla., and president-elect of the American Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine.

Doctors love the specialty and can join it with as little as a year of training after their residency, as compared with the more typical two to four years for other specialty training. They see a large group of patients eager for treatment, ranging from competitive athletes to casual exercisers to retirees spending their time on the golf course or tennis court.

The problem is that most sports injuries, including tears of the hamstring ligament like Ms. Basle’s, have no established treatments.

Of course, some remedies for certain injuries do work: putting a cast on a broken bone or operating to repair a torn Achilles tendon. But patients whose injuries have no effective treatment often do not know that medicine has nothing to offer. And many expect cures.

“They watch ‘Grey’s Anatomy’ and think we can do anything,” said Dr. Raymond Monto, a sports medicine orthopedist in West Tisbury, Mass. “And to a certain extent, we allow that.”

Added to that is the effect of sports stars and their doctors. Patients “see a high-profile athlete and say, ‘I want you to do it exactly the same way their doctor did it,’ ” said Dr. Edward McDevitt, an orthopedist in Arnold, Md., who specializes in sports medicine.

The result is therapies that are unproven, possibly worthless or even harmful. There is surgery, like a popular operation that shaves the hip bone to prevent arthritis, that may not work. There are treatments, like steroid injections for injured tendons or taping a sprained ankle, that can slow the healing process. And there are fads, like one of Ms. Basle’s treatments, P.R.P., that soar in popularity while experts debate whether they help.

All this leads Dr. Andrew Green, a shoulder orthopedist at Brown University, to ask, “Is sports medicine a science, something that really pays attention to evidence? Or is it a boutique industry where you have a product and sell it?”

“For a lot of people it is a boutique business,” he said. “But are you still a doctor if you do that?”

A Theory Becomes a Fad

If ever anyone wanted to know how untested sports medicine treatments come into use, they would need only look at platelet-rich plasma, medical experts say. They joke that it is the perfect example of what is a tried-and-true path to popularizing a new treatment. It is what Dr. John Bergfeld, an orthopedic sports medicine specialist at the Cleveland Clinic, calls the Orthopedic Triad: famous athlete, famous doctor, untested treatment.

While there are no official statistics on P.R.P. treatment, all agree that it has exploded on the scene, propelled by testimonials from celebrity athletes.

Part of its appeal was that it made sense. Blood contains platelets that secrete growth factors that, in turn, can help tissue heal. So if a patient’s own platelets are injected into the injury site, they might speed recovery. And since it is the patient’s own platelets, the treatment is unlikely to be harmful.

It is easy to extract platelets. A doctor spins a tube of a patient’s blood in a centrifuge and then removes the middle layer of cells. Those are the platelets.

The claims by athletes and their doctors that brought the treatment to the fore began in the winter of 2009. Two leading football players for the Pittsburgh Steelers — Hines Ward, who sprained a ligament in his knee, and Troy Polamalu, who strained his calf — had P.R.P., recovered quickly and went on to play in the Super Bowl.

Earlier that year, a doctor for a pitcher for the Los Angeles Dodgers, Takashi Saito, said P.R.P. let the pitcher avoid surgery, which would have put him out of commission for about a year. Soon afterward, Tiger Woods reported that he had had four P.R.P. injections after knee surgery.

His doctor, Anthony Galea, who was later investigated for providing performance enhancing drugs to athletes, told The New York Times in December 2009 that within two days after his first treatment, Woods sent him a text. “He said he couldn’t believe how good he felt,” Dr. Galea said. “He’d joke and say, ‘I can jump on the kitchen table.’ ”

Having an athlete report that a treatment worked “is almost like direct-to-consumer advertising,” said Dr. Fred Azur, a sports medicine orthopedist in Memphis.

Of course, researchers say, testimonials from athletes and their doctors are a far cry from credible evidence. Most injuries eventually get better on their own, so if a patient has a treatment and then gets better, would the person have gotten better at the same time anyway? Or did the treatment actually slow the healing process? There is no way to know without a study that compares people who were randomly assigned to have a treatment with those who were randomly assigned not to have it.

But testimonials, especially from celebrities, had an effect.

Patients began asking for the treatment, and sports medicine doctors responded, offering it to speed healing of tissue and muscle injuries, mend broken bones and even help with arthritis.

(This reporter tried P.R.P. in 2009 for a torn hamstring and wrote in an article about the experience that it was impossible to know if it helped; her hamstring eventually healed.)

The number of commercially available kits for obtaining the platelet-rich plasma in a doctor’s office more than doubled, to 16 from six, in the past five years. Some journals devoted entire issues to the treatment, even though most of these papers fall far short of scientific rigor. Interest among orthopedists is so intense that the orthopedists’ association devoted a daylong session to the procedure before its annual meeting, something the group had never done before.

Prices varied widely from hundreds to thousands of dollars per injection. The cost of the equipment — tubing, test tubes — is about $150 to $200. The rest goes to the doctor and the hospital.

If an injury fails to heal, doctors often inject again and again. Insurers usually do not pay, so patients, like Ms. Basle, pay out of their own pocket — she paid $1,500 for an injection.

P.R.P. has gotten so popular, in fact, that there is sort of a price war. In some places, doctors who were charging more than $1,000 two years ago charge about $500 today.

In the meantime, sales representatives from equipment makers urge doctors to use it, telling them, said Dr. Marc Schneider, a sports medicine orthopedist in Cleveland, that “there is no downside.”

But, Dr. Schneider asked, “is there an upside?”

Those who say no to requests for the treatment often lose patients.

“Patients come in and say, ‘I want the same thing that Tiger Woods had,’ ” said Dr. McDevitt, the sports medicine orthopedist in Maryland. “I say, ‘It really hasn’t been proven.’ And they say, ‘Well, I don’t care.’ ”

And when he refuses to provide the treatment to patients, Dr. McDevitt adds, “They usually say: ‘No offense, Doctor. You seem like a nice guy, but I will go to see one of the many, many other doctors who will do it.’ ”

Conflicting Studies

As the editor of a newsletter put out by the orthopedics society, Dr. S. Terry Canale wanted to give doctors some guidance about P.R.P. There were lots of studies, but most were not rigorous, Dr. Canale said, and they came to contradictory conclusions. To further complicate matters, there were four different ways of preparing the treatment, and doctors asked if the different results reflected different preparations.

“It went on and on,” Dr. Canale said. “There was no obvious conclusion.”

Some of the best studies, though, were disappointing. For example, one found that the treatment was no better than saline injections for people with Achilles tendinopathy, a painful injury that often afflicts athletes like runners or tennis players and resists treatment.

Maybe, some said, the problem is that P.R.P. diffuses after it is injected.

Dr. Scott Rodeo of the Hospital for Special Surgery in New York addressed that in a new study. His patients had torn their rotator cuffs, a tendon in the shoulder, a painful injury affecting tennis players and swimmers, among others.

During surgery to sew the tendon together, Dr. Rodeo added P.R.P. directly to the injury, embedding it in a fibrin matrix that, he said, “is sort of like chewing gum” to ensure it stayed in place. The procedure did not help.

There was one rigorous study — of tennis elbow — that did have a positive result. But it compared P.R.P. with cortisone injections, which can impede healing. Critics said the treatment should have been compared with saline injections, which could serve as a placebo. A new study comparing it with saline found that it was no better than the salt water.

In February — when some of these studies were released, and others were still under way — Dr. Canale decided it was time to try to sort things out. He invited about 50 leading experts on P.R.P. to meet, review the data on the treatment and reach some sort of consensus on whether it worked.

They included Dr. Allan Mishra, an orthopedist in private practice in Menlo Park, Calif., who is supported by and gets royalties from one of the P.R.P. equipment makers, Biomet, and is on the board of directors and owns stock in another company, BioParadox, which is exploring the treatment for cardiovascular disease.

Dr. Mishra says more research is needed but offers the treatment for a variety of injuries. His Web page includes a TV news video that claims P.R.P. cured a Stanford football player, James McGillicuddy, with a torn knee tendon. On the program, Dr. Mishra says that, in general, 90 percent of the patients he treats “get better and stay better” after the treatment.

Dr. Canale, who says he receives no support from the P.R.P. industry, said: “The bottom line is that most think it works. The operative word is ‘think.’ They don’t know if it works. They have a feeling it does.”

Dr. Rodeo, who also reports having no conflicts of interest, said he understood that response. “Unfortunately in our field, there often is acceptance and use before there is data,” he said.

The Next Big Thing?

As orthopedists and other sports medicine doctors argue about this particular treatment, another popular treatment is forming. It leapt to the public and medical world’s attention this year when Bartolo Colon, a pitcher for the New York Yankees, made an astonishing comeback from elbow injuries and a torn rotator cuff that had plagued him for years and had kept him from pitching for all of 2010.

In May, Mr. Colon and his doctor, Joseph R. Purita, an orthopedic surgeon in Boca Raton, Fla., reported that Mr. Colon was treated with P.R.P. and “stem cells” — his own fat and bone marrow cells, injected into his shoulder and elbow. Dr. Purita worked with the Harvest Technologies Corporation, a Massachusetts company that also supplies equipment for P.R.P.

The opening scenes seem familiar to those who followed the saga of P.R.P.

Once again, there is a rationale behind the treatment, said Rocky Tuan, director of the Center for Cellular and Molecular Engineering at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center.

The reasoning began with questions about why P.R.P. is not clearly effective. The problem may be that growth factors released from platelets need cells that can respond. But most tissues in joints and tendons have very few cells.

“That’s where stem cells come in,” Dr. Tuan said. Fat and bone marrow contain stem cells that might grow into joint or tendon if they were placed in the right environment. And if a patient also gets an injection of P.R.P., a tendon or joint might actually heal.

The key word, of course, is “might.”

For now, Dr. Tuan said, “no systematic study has been done.”

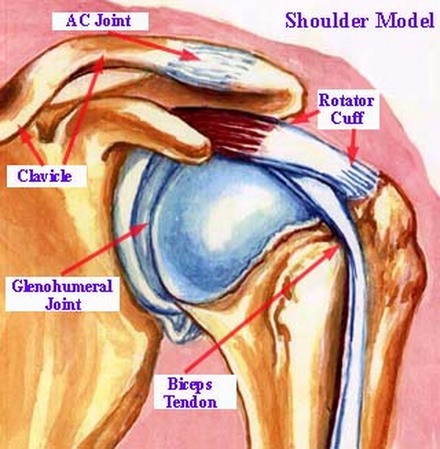

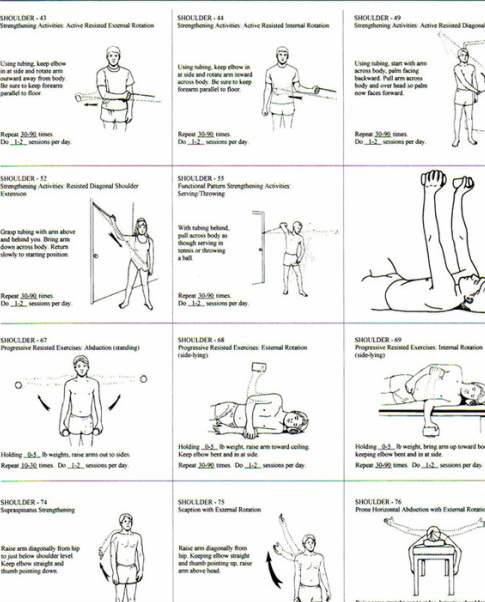

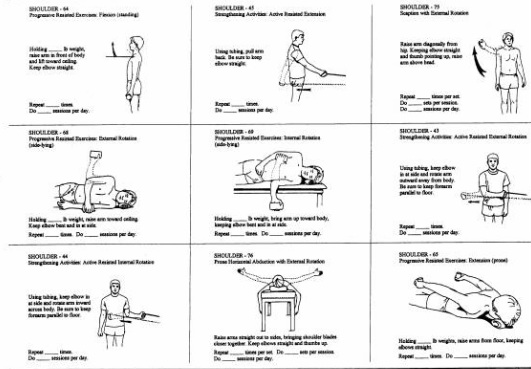

THE SHOULDER

Rotator Cuff Exercises

Before you start

The exercises described below can help you strengthen the muscles in your shoulder (especially the muscles of the rotator cuff--the part that helps circular motion). These exercises should not cause you pain. If you feel any pain, stop exercising. Start again with a lighter weight.

Look at the pictures with each exercise so you can use the correct position. Warm up before adding weights. To warm up, stretch your arms and shoulders, and do pendulum exercises. To do pendulum exercises, bend from the waist, letting your arms hang down. Keep your arm and shoulder muscles relaxed, and move your arms slowly back and forth. Perform the exercises slowly: Lift your arm to a slow count of 3 and lower your arm to a slow count of 6.

Keep repeating each of the following exercises until your arm is tired. Use a light enough weight that you don't get tired until you've done the exercise about 20 to 30 times. Increase the weight a little each week (but never so much that the weight causes pain). Start with 2 ounces the first week. Move up to 4 ounces the second week, 8 ounces the next week and so on.

Each time you finish doing all 4 exercises, put an ice pack on your shoulder for 20 minutes. It's best to use a plastic bag with ice cubes in it or a bag of frozen peas, not gel packs. If you do all 4 exercises 3 to 5 times a week, your rotator cuff muscles will become stronger, and you'll get back normal strength in your shoulder.

Exercise 1

Start by lying on your stomach on a table or a bed. Put your left arm out at shoulder level with your elbow bent to 90° and your hand down. Keep your elbow bent, and slowly raise your left hand. Stop when your hand is level with your shoulder. Lower your hand slowly. Repeat the exercise until your arm is tired. Then do the exercise with your right arm.

Exercise 2

Lie on your right side with a rolled-up towel under your right armpit. Stretch your right arm above your head. Keep your left arm at your side with your elbow bent to 90° and the forearm resting against your chest, palm down. Roll your left shoulder out, raising the left forearm until it's level with your shoulder. (Hint: This is like the backhand swing in tennis.) Lower the arm slowly. Repeat the exercise until your arm is tired. Then do the exercise with your right arm.

Exercise 3

Lie on your right side. Keep your left arm along the upper side of your body. Bend your right elbow to 90°. Keep the right forearm resting on the table. Now roll your right shoulder in, raising your right forearm up to your chest. (Hint: This is like the forehand swing in tennis.) Lower the forearm slowly. Repeat the exercise until your arm is tired. Then do the exercise with your left arm.

Exercise 4

In a standing position, start with your right arm halfway between the front and side of your body, thumb down. (You may need to raise your left arm for balance.) Raise your right arm until almost level (about a 45° angle). (Hint: This is like emptying a can.) Don't lift beyond the point of pain. Slowly lower your arm. Repeat the exercise until your arm is tired. Then do the exercise with your left arm.

Before you start

The exercises described below can help you strengthen the muscles in your shoulder (especially the muscles of the rotator cuff--the part that helps circular motion). These exercises should not cause you pain. If you feel any pain, stop exercising. Start again with a lighter weight.

Look at the pictures with each exercise so you can use the correct position. Warm up before adding weights. To warm up, stretch your arms and shoulders, and do pendulum exercises. To do pendulum exercises, bend from the waist, letting your arms hang down. Keep your arm and shoulder muscles relaxed, and move your arms slowly back and forth. Perform the exercises slowly: Lift your arm to a slow count of 3 and lower your arm to a slow count of 6.

Keep repeating each of the following exercises until your arm is tired. Use a light enough weight that you don't get tired until you've done the exercise about 20 to 30 times. Increase the weight a little each week (but never so much that the weight causes pain). Start with 2 ounces the first week. Move up to 4 ounces the second week, 8 ounces the next week and so on.

Each time you finish doing all 4 exercises, put an ice pack on your shoulder for 20 minutes. It's best to use a plastic bag with ice cubes in it or a bag of frozen peas, not gel packs. If you do all 4 exercises 3 to 5 times a week, your rotator cuff muscles will become stronger, and you'll get back normal strength in your shoulder.

Exercise 1

Start by lying on your stomach on a table or a bed. Put your left arm out at shoulder level with your elbow bent to 90° and your hand down. Keep your elbow bent, and slowly raise your left hand. Stop when your hand is level with your shoulder. Lower your hand slowly. Repeat the exercise until your arm is tired. Then do the exercise with your right arm.

Exercise 2

Lie on your right side with a rolled-up towel under your right armpit. Stretch your right arm above your head. Keep your left arm at your side with your elbow bent to 90° and the forearm resting against your chest, palm down. Roll your left shoulder out, raising the left forearm until it's level with your shoulder. (Hint: This is like the backhand swing in tennis.) Lower the arm slowly. Repeat the exercise until your arm is tired. Then do the exercise with your right arm.

Exercise 3

Lie on your right side. Keep your left arm along the upper side of your body. Bend your right elbow to 90°. Keep the right forearm resting on the table. Now roll your right shoulder in, raising your right forearm up to your chest. (Hint: This is like the forehand swing in tennis.) Lower the forearm slowly. Repeat the exercise until your arm is tired. Then do the exercise with your left arm.

Exercise 4

In a standing position, start with your right arm halfway between the front and side of your body, thumb down. (You may need to raise your left arm for balance.) Raise your right arm until almost level (about a 45° angle). (Hint: This is like emptying a can.) Don't lift beyond the point of pain. Slowly lower your arm. Repeat the exercise until your arm is tired. Then do the exercise with your left arm.

A Safer Shoulder Workout

By Anahad O'Connor : NY Times : September 29, 2011

Is your shoulder workout doing more harm than good?

For gymgoers looking to build strength and fill out their T-shirts, poor form or technique can turn shoulder workouts into a fast track to physical therapy. About a third of all resistance training injuries involve the deltoids, the muscles that form the rounded contour of the shoulder, making them one of the most common injuries that occur in the weight room.

But many of these injuries can be prevented with small changes in technique, a fact highlighted by new research published in the latest issue of Strength & Conditioning Journal.

The research focuses on one of the most popular shoulder exercises for men and women: the upright row. If you spend any time around the weight rack at your gym, chances are you know it.

To perform an upright row, pick up a barbell with an overhand grip, hold it by your waist, and lift straight up toward your chin. Some people use a pair of light dumbbells, kettle bells or a cable machine. All accomplish the same goal, strengthening the trapezius (a large muscle that spans the neck, shoulders and back) and the medial deltoid (the middle of the three muscles that make up the deltoids).

The problem, research shows, is that most people invariably lift the weight too high, which can lead to shoulder impingement, in which the shoulder blade rubs, or impinges, on the rotator cuff, causing pain and irritation.

“I would say 80 percent of gymgoers do this exercise wrong,” said Brad Schoenfeld, a lecturer in the exercise science department at Lehman College (part of the City University of New York) and an author of the study. “In fact, if you ask a lot of trainers, they’ll say never do an upright row, you’ll get an impingement from it.”

When doing an upright row, don’t raise the bar too high. The study found that three simple steps can reduce the risk of injury.

The same rule holds for another popular exercise called the lateral raise, which develops the medial deltoids. Mr. Schoenfeld advises starting with a weight or kettle bell in each hand, arms at your side and knees slightly bent. Lift the weights out to the side, arms slightly bent — but do not extend any higher than the level of your shoulders. Just as with the upright row, poor form in the lateral raise can lead to impingement.

Exercising the medial deltoids carries a number of aesthetic and practical benefits. In addition to creating more muscle definition, the exercises can round out the shoulders and enhance the look of the upper arms (think Michelle Obama or Hugh Jackman guns). The exercises can also build strength for everyday activities like carrying groceries, lifting heavy objects or hoisting small children.

Mr. Schoenfeld also advises eliminating two shoulder exercises from your workout. Skip the behind-the-neck shoulder press because lifting behind the neck can easily strain the rotator cuff and put excessive stress on the shoulder joint. A related exercise, the behind-the-neck pull down, causes similar problems and raises the risk of impingement.

Instead, just pull the bar down in front of your head, not behind it.

“You should always do the pull down from the front,” Mr. Schoenfeld said. “If you pull down hard behind the neck it can damage the cervical spine, and studies show that the front lat pull down has greater muscle recruitment. I just can’t think of any reason why you should ever do the behind-the-neck pull down.”

By Anahad O'Connor : NY Times : September 29, 2011

Is your shoulder workout doing more harm than good?

For gymgoers looking to build strength and fill out their T-shirts, poor form or technique can turn shoulder workouts into a fast track to physical therapy. About a third of all resistance training injuries involve the deltoids, the muscles that form the rounded contour of the shoulder, making them one of the most common injuries that occur in the weight room.

But many of these injuries can be prevented with small changes in technique, a fact highlighted by new research published in the latest issue of Strength & Conditioning Journal.

The research focuses on one of the most popular shoulder exercises for men and women: the upright row. If you spend any time around the weight rack at your gym, chances are you know it.

To perform an upright row, pick up a barbell with an overhand grip, hold it by your waist, and lift straight up toward your chin. Some people use a pair of light dumbbells, kettle bells or a cable machine. All accomplish the same goal, strengthening the trapezius (a large muscle that spans the neck, shoulders and back) and the medial deltoid (the middle of the three muscles that make up the deltoids).

The problem, research shows, is that most people invariably lift the weight too high, which can lead to shoulder impingement, in which the shoulder blade rubs, or impinges, on the rotator cuff, causing pain and irritation.

“I would say 80 percent of gymgoers do this exercise wrong,” said Brad Schoenfeld, a lecturer in the exercise science department at Lehman College (part of the City University of New York) and an author of the study. “In fact, if you ask a lot of trainers, they’ll say never do an upright row, you’ll get an impingement from it.”

When doing an upright row, don’t raise the bar too high. The study found that three simple steps can reduce the risk of injury.

- Keep the weight as close to your body as possible during the movement.

- Avoid the temptation to pull the weight up to your chin or nose.

- Don’t let your elbows or the weight climb any higher than your shoulders.

The same rule holds for another popular exercise called the lateral raise, which develops the medial deltoids. Mr. Schoenfeld advises starting with a weight or kettle bell in each hand, arms at your side and knees slightly bent. Lift the weights out to the side, arms slightly bent — but do not extend any higher than the level of your shoulders. Just as with the upright row, poor form in the lateral raise can lead to impingement.

Exercising the medial deltoids carries a number of aesthetic and practical benefits. In addition to creating more muscle definition, the exercises can round out the shoulders and enhance the look of the upper arms (think Michelle Obama or Hugh Jackman guns). The exercises can also build strength for everyday activities like carrying groceries, lifting heavy objects or hoisting small children.

Mr. Schoenfeld also advises eliminating two shoulder exercises from your workout. Skip the behind-the-neck shoulder press because lifting behind the neck can easily strain the rotator cuff and put excessive stress on the shoulder joint. A related exercise, the behind-the-neck pull down, causes similar problems and raises the risk of impingement.

Instead, just pull the bar down in front of your head, not behind it.

“You should always do the pull down from the front,” Mr. Schoenfeld said. “If you pull down hard behind the neck it can damage the cervical spine, and studies show that the front lat pull down has greater muscle recruitment. I just can’t think of any reason why you should ever do the behind-the-neck pull down.”

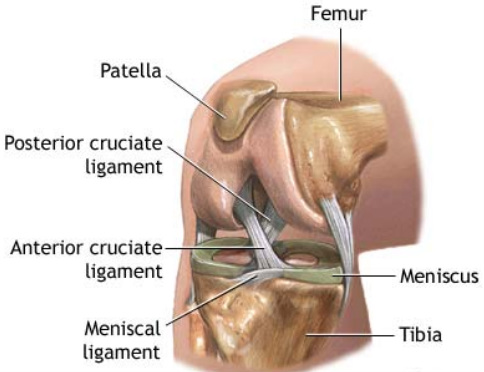

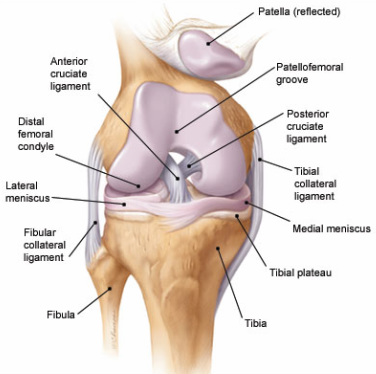

THE KNEE

Could You Have a Jeremy Lin Knee?

A Torn Meniscus Can Go Unnoticed; 42% of Older Men Have Some Damage

Melinda Beck : WSJ : April 2, 2012

A Torn Meniscus Can Go Unnoticed; 42% of Older Men Have Some Damage

Melinda Beck : WSJ : April 2, 2012

- Of the more than 7,500 parts in the human body, the knee's meniscus may be the most vulnerable.

The crescent-shaped cushions of rubbery cartilage—two in each knee—act as shock absorbers as people walk, run, pivot and bend. Sudden stops and twisting motions can cause the meniscus to rip or experience a more gradual tear.

Jeremy Lin is the latest pro athlete to fall victim. The popular New York Knicks point guard will have surgery this week on a small, chronic tear in his left knee and miss the rest of the season, the team announced Saturday. Last month, Red Bulls power forward Juan Agudelo, Atlanta Braves third baseman Chipper Jones and Kansas City Royals catcher Salvador Perez all had meniscus surgery.

Many skiers, cyclists, joggers, golfers and other weekend warriors also damage their menisci, as do a growing number of teens and adolescents who play sports.

It isn't just athletes who are at risk. Cartilage weakens and frays naturally with age, so older people can tear a meniscus just walking or rising from a chair. Excess weight also places extra stress on joints and wears down cartilage faster.

"A lot of tears are due to chronic degeneration," says Frederick Azar, chief of staff at the Campbell Clinic in Germantown, Tenn., and a spokesman for the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, or AAOS. "People may attribute them to a sudden movement, but usually the trouble has been brewing for a long time."

Not surprisingly, knee injuries are rising with the aging population and the obesity epidemic. More than four million Americans visited physicians for meniscus tears in 2009, more than double the number of 2000, according to the AAOS.

Not every torn meniscus needs to be fixed. In a landmark study in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2008, researchers randomly selected 991 people aged 50 to 90 to undergo MRIs of the right knee. Overall, 30% of the women and 42% of the men were found to have a tear or other meniscus damage. Of those, 61% said they hadn't experienced any pain or disability in the knee during the previous month, meaning a torn meniscus can often go unnoticed.

That's why orthopedists often say, "Treat the patient, not the MRI."

Surgery is usually recommended in the case of a sudden, severe meniscus tear or in a young athlete with a long playing career ahead. Surgery is also warranted if the knee makes a "popping" or "clicking" sound or catches when bending, which often means that a piece of meniscus has come loose inside the joint.

But if the tear is the result of long-term degeneration and osteoarthritis has set in, several studies show that patients do just as well with physical therapy as they do with surgery.

"If the MRI shows a meniscus tear, but the patient isn't experiencing catching or locking [and] their X-rays show early arthritis, I don't think they'd be a surgical candidate," says Michael Stuart, professor of orthopedics at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. "But we would help with their pain. We'd suggest weight loss, activity modification, anti-inflammatory medications, maybe an injection of a local anesthetic and orthotics in their shoes."

Much also depends on the size and location of the tear. While surgeons can suture a small tear on the periphery of the meniscus, the inner portion of the meniscus doesn't have its own blood supply, so repairs there seldom heal. Surgeons remove the damaged portion instead.

As late as 1971, surgeons frequently removed the entire meniscus if part of it was damaged. Now they leave as much of the meniscus in place as possible. Nearly 700,000 such "partial meniscectomies" were performed in 2006, usually with arthroscopy, in which surgeons using tiny incisions and a lighted scope that lets them both see and sculpt the tissue.

Many patients report significant relief from the procedure, which is usually done on an outpatient basis.

"I wish I'd had the surgery sooner," says Haralee Weintraub of Portland, Ore., who hurt her right knee skiing and put up with pain for 10 years before she had the procedure in 2003 at age 50.

But having only a partial meniscus does alter the way the knee joint handles body movements and raises the risk of osteoarthritis later. Whether that's inevitable depends on the patient's age, health, genes and activity levels.

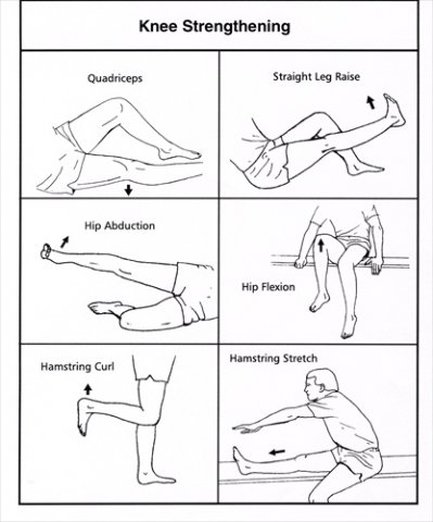

Physical therapy and strength training before and after the surgery can be crucial. But patients are often told to avoid high-impact sports, or they run the risk of needing a knee replacement later.

By the time he was 18, Anthony Baldinelli had torn his menisci three times playing soccer and had much of the cartilage removed. Now he gets a flare-up of arthritis when he plays sports more than once a week. Doctors want to avoid a knee replacement because he's only 23. "On X-rays, my right knee looks like an old man's," says Mr. Baldinelli, a publicist in Raleigh, N.C.

When a meniscus tear is very large or complex, a transplant may be an option. The tissue is taken from cadavers that have been frozen and screened for infections. The risk of rejection is minimal with cartilage; matches are based on size instead.

Follow-up studies have found that about 80% of transplant recipients find significant pain relief. But a donor meniscus isn't as good as an original. "After about 10 years, 40% of them will have torn and require additional surgery or partial or total removal," says Dr. Stuart.

Mike Schwartz, 43, who runs an Internet apparel company in Santa Monica, Calif., damaged his knees as a gymnast in his teens and had a meniscus transplant in 2007. He is grateful that his knee no longer swells up easily, but it is still stiff and sore if he leaves it unbent too long. "My knee still pretty much hurts all the time," he says.

In many cases, physical therapy can stave off the need for meniscus surgery for a few years—or indefinitely. The training strengthens and retrains leg muscles to put less strain on damaged tissue.

Some clinics are trying a variety of techniques aimed at coaxing the body to heal itself, with or without surgery. Injections of platelet-rich plasma, or PRP, are popular among pro athletes. Doctors withdraw several ounces of the patient's own blood, spin it and separate out the platelets, which secrete natural growth factors, then inject them back into the site of injury, where they theoretically stimulate healing. But there have been few randomized trials to date and results have been mixed.

Injections of hyaluronic acid—originally derived from the combs of roosters—can lubricate knee joints and stave off surgery in some cases. Patricia Lorenz, 66, of Clearwater, Fla., who tore her meniscus "traipsing all over Europe" in 2000, was scheduled for knee-replacement surgery in January when a sports-medicine doctor gave her a cortisone shot and three injections of rooster cartilage.

"The pain went away immediately," says Ms. Lorenz, an author and speaker. "He says it will last six to 12 months and then I can get three more shots."

Researchers are hoping to develop stem-cell therapies to repair damaged meniscus tissue. Others are engineering biodegradable scaffoldings that could serve as a matrix for growing a new meniscus inside patients' knees. Until then, orthopedists advise patients to treat their knees with respect and assume they are the only two they will get.

Common Knee Surgery Does Very Little for Some, Study Suggests

By Pam Belluck : NY Times : December 25, 2013

A popular surgical procedure worked no better than fake operations in helping people with one type of common knee problem, suggesting that thousands of people may be undergoing unnecessary surgery, a new study in The New England Journal of Medicine reports.

The unusual study involved people with a torn meniscus, crescent-shaped cartilage that helps cushion and stabilize knees. Arthroscopic surgery on the meniscus is the most common orthopedic procedure in the United States, performed, the study said, about 700,000 times a year at an estimated cost of $4 billion.

The study, conducted in Finland, involved a small subset of meniscal tears. But experts, including some orthopedic surgeons, said the study added to other recent research suggesting that meniscal surgery should be aimed at a narrower group of patients; that for many, options like physical therapy may be as good.

The surgery, arthroscopic partial meniscectomy, involves small incisions. They are to accommodate the arthroscope, which allows doctors to see inside, and for tools to trim torn meniscus and to smooth ragged edges of what remains.

The Finnish study does not indicate that surgery never helps; there is consensus that it should be performed in some circumstances, especially for younger patients and for tears from acute sports injuries. But about 80 percent of tears develop from wear and aging, and some researchers believe surgery in those cases should be significantly limited.

“Those who do research have been gradually showing that this popular operation is not of very much value,” said Dr. David Felson, a professor of medicine and epidemiology at Boston University. This study “provides information beautifully about whether the surgery that the orthopedist thinks he or she is doing is accomplishing anything. I think often the answer is no.”

The volunteer patients in the Finnish study all received anesthesia and incisions. But some received actual surgery, others simulated procedures. They did not know which.

A year later, most patients in both groups said their knees felt better, and the vast majority said they would choose the same method again, even if it was fake.

“It’s a well-done study,” said Dr. David Jevsevar, chairman of the committee on evidence-based quality and value of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. “It gives further credence or support to a number of studies that have shown that giving arthroscopy to patients is not always going to make a difference.”

Dr. Jevsevar, an orthopedic surgeon in St. George, Utah, said he hoped the study would spur research to better identify patients who should have surgery.

“Are there operations that are done that do not need to be done? I’m sure that’s the case, but we don’t know the magnitude,” he said. “We still think there’s benefit in arthroscopic meniscectomy in appropriate patients. What we need to define in the future is what’s the definition of appropriate patient.”

One factor is whether pain is caused by the torn meniscus or something else, especially osteoarthritis, which often accompanies tears. Another possible consideration is whether mechanical knee function is affected.

“Take 100 people with knee pain; a very high percentage have a meniscal tear,” said Dr. Kenneth Fine, an orthopedic surgeon who also teaches at George Washington University. “People love concreteness: ‘There’s a tear, you know. You have to take care of the tear.’ I tell them, ‘No. 1, I’m not so sure the meniscal tear is causing your pain, and No. 2, even if it is, I’m not sure the surgery’s going to take care of it.”

Dr. Fine added: “Yours truly has a meniscal tear. It just causes pain. I’m not having any mechanical symptoms; my knees are not locking. So I’m not going to let anybody operate.”

He likened the recent studies to attempts to educate people that “it’s not really good to take antibiotics for the common cold. There’s a lot of pressure to operate. Financial, obviously. But also, if a primary care doctor keeps sending me patients who are complaining of knee pain and I keep not operating on them, then the primary care doctor is going to stop sending me patients.”

The new research builds on a groundbreaking 2002 Texas study, showing that patients receiving arthroscopy for knee osteoarthritis fared no better than those receiving sham surgery. A 2008 Canadian study found that patients undergoing surgery for knee arthritis did no better than those having physical therapy and taking medication. Now many surgeons have stopped operating on patients with only knee arthritis.

Earlier this year, a study at seven American hospitals found that patients with meniscal tears and osteoarthritis did not experience greater improvement with surgery than those receiving physical therapy, although after six months, one-third of the physical therapy group sought surgery. (Their surgical results were not reported.)

An author of that study, Dr. Robert Marx of the Hospital for Special Surgery, said his conclusion was that often physical therapy should be tried before surgery. Still, “properly selected patients do benefit from knee arthroscopy,” he said. “When you have someone who doesn’t have arthritis and they have a painful meniscal tear, you’re going to make that person very happy.”

Dr. Marx expressed some skepticism about the Finnish study, which involved patients with only meniscal tears, not perceptible arthritis. He wondered if the tears were small or if the pain was caused by the kneecap, adding, “I cannot believe that this would be the same population of patients I would operate on.”

Dr. Teppo Jarvinen, an author of the Finnish study, said whether meniscal tears caused the participants’ pain was unknown, but arthritis was an unlikely cause, since they seemingly had none. About 10 percent of meniscal tear patients have no arthritis, he said.

The study involved five hospitals and 146 patients, ages 35 to 65, with wear-induced tears and knee pain. About half had mechanical problems like locking or clicking knees.

Most patients received spinal anesthesia, remaining awake (one hospital used general anesthesia). Surgeons used arthroscopes to assess the knee. If it matched study criteria, nurses opened envelopes containing random assignments to actual or sham surgery. In real surgery, shaver tools trimmed torn meniscus; for fake surgery, bladeless shavers were rubbed against the outside of the kneecap to simulate that sensation. Nobody evaluating the patients later knew which procedure had been received.

After a year, each group reported similar improvement, even those with clicking or locking knees. Two in the surgery group needed further surgery; five in the sham group requested surgery. Dr. Jarvinen acknowledged the possibility that fake surgery had some placebo effect but said results were too strong for that to explain everything.

Dr. Frederick Azar, first vice president of the orthopedic surgeons academy, said the study focused on a minority of patients, those he already did not operate on; he operates mostly on patients with mild to moderate arthritis whose meniscal tears appear to be causing pain.

“Arthroscopy is a very useful tool,” he said. Still, he said, “I’m sure there are some physicians who may look at this and say it may change the way they approach their patients, in terms of surgery or not surgery.”

Doctors' New Advice for Joint Pain:

Get Moving

By Laura Landro : WSJ Article : April 12, 2011

Doctors increasingly are recommending physical activity to help osteoarthritis patients, overturning the more traditional medical advice for people to take it easy to protect their joints.

The new treatment approach comes as osteoarthritis, a degenerative joint disease once considered a problem of old age, has begun showing up in more middle-aged and young adults as a result of obesity and sports injuries. Studies have shown that weight loss, combined with exercises aimed at improving joint function and building up muscles that support the joints, can significantly improve patients' health and quality of life compared with medication alone.

Treating Osteoarthritis

Doctors recommend a range of moderate physical activities and weight loss to help manage osteoarthritis. Exercises to improve flexibility, such as the knee-to-chest stretch, decrease joint stiffness and improve range of motion. They also minimize muscle soreness after workouts and reduce injury.

What to do:

Yoga and tai chi, and basic hamstring, shoulder, neck and back stretches. Reach for the sky and toes.

What not to do:

Don't bounce when holding a stretch. And don't forget to stretch after finishing a workout.

"The most dangerous exercise you can do when you have arthritis is none," says Kate Lorig, director of the Patient Education Research Center at Stanford University. Since each pound of extra body weight adds the equivalent of four pounds to the knees, even a small loss of weight can cut in half the risk of knee osteoarthritis for women, who are at higher risk than men, studies show.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has stepped up funding to programs in a dozen states that include free six-week classes to teach osteoarthritis patients to take an active role in managing their disease. The federal Administration on Aging has funded similar programs in most parts of the country. And the nonprofit National Council on Aging has begun offering an online self-management program for patients to use on their own time.

Osteoarthritis, which can affect knees, hips, feet, hands and other parts of the body, occurs when the cartilage that cushions the spaces between the joints wears away. The disease affects some 27 million Americans and leads to 632,000 surgical joint replacements a year. It is the most common cause of disability for U.S. adults, according to the nonprofit Arthritis Foundation. That number is expected to grow as the population ages: One in two adults will develop knee osteoarthritis before age 85, and the risk increases to two in three adults who are obese.

Exercising Your Joints

Build an exercise routine slowly in five- to 10-minute blocks, working up to 30 minutes total. Three 10-minute sessions in a day are as effective as one 30-minute session. If you are regularly getting 30 minutes of physical activity most days, start adding time gradually.

Aerobic fitness, like doing aquatic exercises, reduces inflammation from arthritis. Aerobic fitness increases metabolism, builds endurance and reduces inflammation from arthritis.

What to do:

Aquatic exercise, cycling, swimming, walking

What not to do:

High-impact aerobics or running Muscle strengthening makes joints more stable and keeps bones positioned properly. It also increases bone density

What to do:

Lift light dumbbells or soup cans, use resistance bands or try Pilates. Focus on doing slow, controlled movements, as in the chair stand, concentrating on proper form.

What not to do:

Do not overtrain by lifting too much weight or performing too many repetitions or sets of exercises. Do not jerk weighted items quickly

Prescription and over-the-counter non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs help reduce pain, swelling and inflammation, but can cause stomach distress and ulcers—and for some people an increased risk of heart attack. Scientists are working to develop new drugs and treatments to rebuild cartilage and slow the progress of osteoarthritis, but these new therapies could be a decade away.

In the meantime, the CDC says obesity prevention, physical activity programs and self-management education courses in local communities offer the best chances of limiting the damage from osteoarthritis. Self-management programs typically involve classes that instruct people on the best exercises for strengthening muscles that support the joints and for enhancing flexibility to keep joints from regularly seizing up. As important, patients are taught which exercises not to do to avoid exacerbating the problem.

Even mild exercise can be painful for osteoarthritis patients. But with time, doctors say, the benefits accumulate as reduced pain and greater mobility. Strengthening the muscles around the knees or hip can help support the joints and take over some of the shock-absorbing functions played by cartilage, according to Harvard Medical School experts. Stronger muscles can also hold the joints in the most functional and least painful position. Regular activity can also replenish lubrication to the cartilage of the joint to reduce stiffness and pain. And aerobic activity such as swimming that doesn't put heavy stress on the hips, knees and spine can reduce inflammation in the joints, as well as improving overall fitness and weight control.

Arthritis self-management programs encourage patients to set up a weekly action plan for exercise and weight loss, including a log to track progress and gradually set higher goals. Coping with depression, a relatively common occurrence in people with restricted mobility, also is part of the lesson plan as is judicious use of pain drugs. The CDC says self-management education has been shown to help the health of an adult with doctor-diagnosed arthritis by 15% to 30% compared to medication alone.

Heredity plays a factor in osteoarthritis, especially in the hands. But early onset osteoarthritis can develop within 10 years of an injury, so a teenager hurt at 15 could have the disease by age 25 or 30.

"We are seeing younger and younger patients coming in with osteoarthritis because of more obesity and injuries," says Nicholas DiNubile, a Philadelphia-area orthopedic surgeon. Of particular concern, Dr. Nubile says is a sharp rise in injuries to the anterior cruciate ligament, or ACL, in the knee, most commonly seen among female soccer players. Some 50% to 80% of players with an ACL tear go on to develop osteoarthritis. But studies have shown that such injuries can be avoided with training programs that focus on landing and decelerating in a more controlled fashion.