- RETIREMENT ANNOUNCEMENT

- HOME PAGE

- "MYCHART" the new patient portal

- BELMONT MEDICAL ASSOCIATES

- MOUNT AUBURN HOSPITAL

- EMERGENCIES

- PRACTICE PHILOSOPHY

- MY RESUME

- TELEMEDICINE CONSULTATION

- CONTACT ME

- LAB RESULTS

- ePRESCRIPTIONS

- eREFERRALS

- RECORD RELEASE

- MEDICAL SCRIBE

- PHYSICIAN ASSISTANT (PA)

- Medicare Annual Wellness Visit

- Case management/Social work

- Quality Care Measures

- Emergency closing notice

- FEEDBACK

- Talking to your doctor

- Choosing..... and losing a doctor

- INDEX A - Z

- ALLERGIC REACTIONS

- Alternative Medicine

- Alzheimer's Disease

- Bladder Problems

- Blood disorders

- Cancer Concerns

- GENETIC TESTING FOR HEREDITARY CANCER

- Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

- Controversial Concerns

- CPR : Learn and save a life

- CRP : Inflammatory marker

- Diabetes Management

- Dizziness, Vertigo,Tinnitus and Hearing Loss

- EXERCISE

- FEMALE HEALTH

-

GASTROINTESTINAL topics

- Appendicitis

- BRAT diet

- Celiac Disease or Sprue

- Crohn's Disease

- Gastroenterologists for Colon Cancer Screening

- Colonoscopy PREP

- Constipation

- Gluten sensitivity, but not celiac disease

- Heartburn and GERD

- Hemorrhoids and Anal fissure

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- NASH : Non Alcoholic Steato Hepatitis

- FEET PROBLEMS

- HEART RELATED topics

-

INFECTIOUS DISEASES

- Antibiotic Resistance

- Cat bites >

- Clostridia difficile infection - the "antibiotic associated germ"

- CORONA VIRUS

- Dengue Fever and Chikungunya Fever

- Food borne illnesses

- Shingles Vaccine

- Hepatitis B

- Hepatitis C

- Herpes

- Influenza

- Helicobacter pylori - the "ulcer germ"

- HIV Screening

- Lyme and other tick borne diseases

- Measles

- Meningitis

- MRSA (Staph infection)

- Norovirus

- Sexually Transmitted Diseases

- Shingles (Herpes Zoster)

- Sinusitis

- West Nile Virus

- Whooping Cough (Pertussis)

- Zika virus and pregnancy

- INSURANCE related topics

- KIDNEY STONES

- LEG CRAMPS

- LIBRARY for patients

- LIFE DECISIONS

- MALE HEALTH

- Medication/Drug side effects

- MEDICAL MARIJUANA

- MENTAL HEALTH

- Miscellaneous Articles

-

NUTRITION - EXERCISE - WEIGHT

- Cholesterol : New guidelines for treatment

- Advice to lower your cholesterol

- Cholesterol : Control

- Cholesterol : Raising your HDL Level

- Exercise

- Food : Making Smart Choices

- Food : Making Poor Choices

- Food : Grape Fruit and Drug Interaction

- Food : Vitamins, Minerals and Supplements

- Omega 3 fatty acids

- Vitamin B12 deficiency

- Vitamin D

- Weight Loss

- ORTHOPEDICS

- PAIN

- PATIENTS' RIGHTS

- SKIN

- SLEEP

- SMOKING

- STROKE

- THYROID

- SUBSTANCE ABUSE

- Travel and Vaccination

- TREMOR

- Warfarin Anticoagulation

- OTHER STUFF FOLLOWS

- Fact or Opinion?

- Hippocratic Oath

- FREE ADVICE.......for what its worth!

- LAUGHTER.....is the best medicine

- Physicians Pet Peeves

- PHOTO ALBUM - its not all work!

- Cape Town, South Africa

- Tribute page

- The 100 Club

- Free Wi-Fi

Warfarin Anticoagulation

This is an important and potentially life saving medication, but it is not without its risks.

It is essential that you understand as much about this medication as you can.

WHAT IS WARFARIN?

Warfarin (brand name Coumadin®) is a prescription medication that inhibits normal blood clotting (coagulation). Because it interferes with the formation of blood clots, it is also called an anticoagulant. Many people refer to these kinds of medicines as blood thinners, although they do not actually cause the blood to become less thick, only less likely to clot.

The normal clotting mechanism is a complex process that involves multiple substances (clotting factors). These factors are produced by the liver and act in sequence to form a blood clot. In order for the liver to produce a number of the clotting factors, adequate amounts of vitamin K must be available. Warfarin blocks the availability of vitamin K, and limits the production of these clotting factors. As a result, the clotting mechanism is disrupted and it takes longer for the blood to clot.

USES

Normally, when body tissues are cut or traumatized, the blood clots in order to prevent excessive blood loss. In some patients, however, the clotting mechanism may be triggered by other factors, leading to the formation of small clots (thrombi) in the bloodstream. These clots may travel through the bloodstream and become lodged in smaller blood vessels, reducing blood flow to the organs supplied by those vessels. Blockage of blood flow can cause serious problems including stroke (when a blood vessel leading to a portion of the brain is blocked) and heart attack (when a blood vessel leading to the heart is blocked).

Warfarin is prescribed for patients who are at increased risk for developing harmful blood clots. Patients at risk for developing such clots include those with a mechanical heart valve, an irregular heart rhythm called atrial fibrillation, and patients with certain clotting disorders. (See "Patient information: Atrial fibrillation").

Warfarin is also used in patients who have previously developed harmful clots, including patients who have had a stroke, heart attack, a clot which has traveled to the lung (pulmonary embolism), or a blood clot in the leg (deep venous thrombosis or DVT). In addition, warfarin may be used to prevent an existing clot from growing larger. (See "Patient information: Venous thrombosis").

MONITORING

The goal of warfarin therapy is to decrease the clotting tendency of blood, but not to prevent clotting completely. Therefore, the effect of warfarin on the blood's ability to clot must be carefully monitored with periodic blood testing. Based on the results of these tests, the dose of warfarin is adjusted to maintain the clotting time within a target range.

Prothrombin time (PT) — The test most commonly used to measure the effects of warfarin is the prothrombin time (called pro time, or PT). The PT is a laboratory test that measures the time it takes for the clotting mechanism to progress. It is particularly sensitive to the clotting factors affected by warfarin. The PT is also used to compute a value known as the INR (or International Normalized Ratio).

International Normalized Ratio (INR) — The INR is a way of expressing the PT in a standardized way; this ensures that results obtained by different laboratories can be reliably compared.

The longer it takes the blood to clot, the higher the PT and INR. The target INR range depends upon the clinical situation. In most cases the target range will be 2 to 3, although other ranges may be chosen if there are special circumstances. If, at any particular time, the INR is below the target range (ie, under-anticoagulated), there is a risk of clotting. If, on the other hand, the INR is above the target range (ie, over-anticoagulated), there is an increased risk of bleeding.

Dosing — When warfarin is first prescribed, a higher loading dose may be given so that an effective blood level of the drug is achieved quickly. The loading dose is then adjusted downward until a maintenance dose is found that maintains the INR within the desired range. The PT and INR are monitored frequently until the maintenance dose has been determined. Once the patient is on a stable maintenance dose, the PT and INR are monitored less frequently, generally once every two to four weeks.

The warfarin dose may be adjusted periodically in response to a changing INR or to clinical circumstances that call for an increase or decrease in warfarin therapy. For example, having surgery may require a change in a patient's warfarin regimen. The dose of warfarin may also be modified if other medicines are taken.

SIDE EFFECTS

The major complication associated with warfarin is bleeding due to excessive anticoagulation. Excessive bleeding, or hemorrhage, can occur from any area of the body, and patients on warfarin should report any falls or accidents, as well as signs or symptoms of bleeding or unusual bruising. Signs of unusual bleeding include bleeding from the gums, blood in the urine, bloody or dark stool, a nosebleed, or vomiting blood. Because the risk of bleeding increases as the INR rises, the INR is closely monitored and adjustments are made as needed to maintain the INR within the target range.

Warfarin can also cause skin necrosis or gangrene, manifested by dark red or black lesions on the skin. This is a rare complication that may occur during the first several days of warfarin therapy.

When to seek help — If there are obvious or subtle signs of bleeding, including the following, patients should call their healthcare provider immediately.

PREGNANCY AND WARFARIN

Warfarin is not recommended during pregnancy, especially during the first trimester, due to an increased risk of miscarriage and birth defects. A patient who becomes pregnant or plans to become pregnant while on warfarin therapy should notify their healthcare provider immediately.

Breastfeeding — Although warfarin does not pass into breast milk, a woman who wishes to breastfeed while taking warfarin should also consult her healthcare provider. Warfarin is considered safe for use in women who breastfeed.

OTHER RECOMMENDATIONS

Take warfarin on a schedule — Warfarin should be taken exactly as directed. Do not increase, decrease, or change the dosing schedule unless told to do so by a healthcare provider. If a dose is missed or forgotten, call the prescribing clinician for advice.

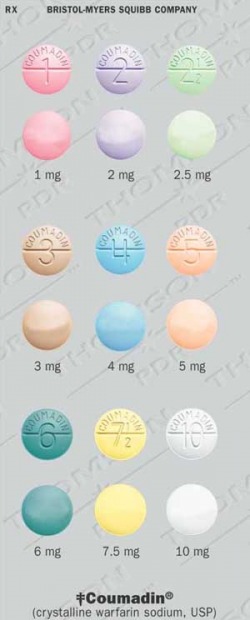

Warfarin tablets come in different strengths; each is usually a different color, with the amount of warfarin (in milligrams) clearly printed on the tablet. If the color or dose of the tablet appears different than those taken previously, the patient should immediately notify their pharmacist or healthcare provider.

Reduce the risk of bleeding —

There is a tendency to bleed more easily than usual while taking warfarin. Some simple changes can decrease this risk:

Falling may significantly increase the risk of bleeding. Taking measures to prevent falls is recommended, and could include the following:

Some foods and supplements can interfere with warfarin's effectiveness. After being stabilized on a particular warfarin dose, consult a healthcare provider before making major dietary changes (eg, starting a diet to lose weight, starting a nutritional supplement or vitamin).

A number of medications, herbs, and vitamins can interact with warfarin (show table 1 and show table 2). This interaction may affect the action of warfarin or the other medication. If warfarin is affected, the dose may need to be adjusted (up or down) to maintain an optimal coagulation effect.

Patients who take warfarin should consult with their clinician before taking any new medication, including over-the-counter (non-prescription) drugs, herbal medicines, vitamins, or any other products. Some of the most common over-the-counter pain relievers, including acetaminophen (Tylenol®), aspirin, and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (such as ibuprofen [Advil®]) and naproxen (Aleve®), enhance the anticoagulant effects of warfarin. Vitamin E may increase the anticoagulant effects of warfarin. Consult a healthcare provider before adding or changing a dose of vitamin E or any other vitamin.

Wear medical identification —

People who require long-term warfarin should wear a bracelet, necklace, or similar alert tag at all times. If an accident occurs and the person is too ill to explain their condition, this will help responders provide appropriate care.

The alert tag should include a list of major medical conditions and the reason warfarin is needed (eg, atrial fibrillation), as well as the name and phone number of an emergency contact. One device, Medic Alert®, provides a toll-free number that emergency medical workers can call to find out a person's medical history, list of medications, family emergency contact numbers, and healthcare provider names and numbers.

Karen A Valentine, MD, PhD

Russell D Hull, MBBS, MSc

UpToDate Patient Information

What is warfarin and the recently approved change in the label for the drug?

Warfarin is a drug prescribed to help prevent blood clots. Following oral ingestion, it acts by blocking the action of certain proteins that cause blood to clot. Since warfarin acts to keep blood from clotting, one of the side effects of the drug is an increased risk for bleeding. This risk increases importantly if patients receive too much warfarin. Patients frequently differ in the dose of warfarin necessary to prevent blood clots and also differ in the risk for bleeding.

The recently approved change in the warfarin label provides information on how people with certain genetic differences may respond to warfarin. Specifically, people with variations in two genes may need lower warfarin doses than people without these genetic variations. The two genes are called CYP2C9 and VKORC1. The CYP2C9 gene is involved in the breakdown (metabolism) of warfarin and the VKORC1 gene helps regulate the ability of warfarin to prevent blood from clotting.

How will this new warfarin label information benefit patients?

This information will benefit patients because it will describe why patients with a variation in the CYP2C9 and/or VKORC1 genes may need a lower warfarin dose than patients with the usual forms of these genes. For patients with these genetic variations, the new label information may help physicians prescribe the correct warfarin dose and also encourage them to give increased attention to how these patients respond to warfarin. Identification of patients with these genetic variations is thought to improve the safe use of warfarin since choosing the correct warfarin dose is important to prevent blood clots and avoid bleeding.

How might healthcare professionals use this information in their practice?

Healthcare professionals might incorporate the genetic information on CYP2C9 and VKORC1, along with various clinical considerations and patient characteristics (e.g., age, body weight) to better estimate the initial warfarin doses for patients. Warfarin is often administered daily and the response to the drug is mainly measured by a laboratory test result called the INR. The INR measures, in part, the blood's ability to clot and the INR should be performed regularly in all patients receiving warfarin. Genetic information does not replace regular INR testing.

Response to warfarin and the risk for bleeding may be influenced by many factors, such as the presence of serious underlying heart disease or the simultaneous use of other drugs which can interact with warfarin. These clinical considerations impact the healthcare professional's decision to prescribe warfarin as well as the selection of the initial warfarin dosages. The recently revised warfarin product label adds CYP2C9 and VKORC1 genetic variations to the list of these clinical considerations for warfarin use. The label's specific warfarin dose recommendations have not changed.

Will healthcare professionals be required to test patients for these genetic variations prior to prescribing warfarin?

No, healthcare professionals are not required to conduct CYP2C9 and VKORC1 testing before initiating warfarin therapy, nor should genetic testing delay the start of warfarin therapy.

Are tests available to detect variations in the CYP2C9 and/or VKORC1 genes?

Yes, laboratory developed tests are available to determine if a patient has certain CYP2C9 and/or VKORC1 gene variants that may influence the response to warfarin. The availability and reliability of these tests may vary from lab to lab and healthcare professionals should check with their local or reference clinical laboratory to obtain more information about the specific tests.

What did clinical studies show to support the addition of genetic information to the warfarin label?

Clinical studies have suggested that patients with CYP2C9*2 and CYP2C9*3 genetic variations are at an increased risk for bleeding with warfarin therapy. In these studies, patients with these variants generally required lower doses of warfarin to achieve a desired INR control and decrease the risk of bleeding .

In general, more limited information is available for VKORC1 genetic variations than for CYP2C9. Among the more notable studies was the importance of VKORC1 detected in a study of 201 Caucasian patients who needed a wide variation in warfarin doses to maintain an acceptable INR test. Of the factors that were examined to determine why the dose varied so much, the presence of a VKORC1 genetic variation was thought to be responsible for 30% of the warfarin dose variation. The presence of either a VKORC1 or a CYP2C9 variation was thought to be responsible for 40% of the warfarin dose variation. Other non-genetic factors, such as age and weight, were responsible for 10% to15% of warfarin dose variation.

Published studies have estimated the prevalence of CYP2C9 and VKORC1 gene variants in a number of ethnic groups. These studies have estimated the frequency of CYP2C9 gene variants, or genotypes, that may influence warfarin doses at approximately 10% to 20% in Caucasians and African-Americans. For the same populations the frequency of important genotypes of VKORC1 is 14% to 37%. The frequency of the important VKORC1 genotype in the Asian population has been reported to be as high as 89%.

The usual genetic form of CYP2C9 with normal enzyme activity is called CYP2C9*1. Studies indicate that the CYP2C9*2 and CYP2C9*3 genetic variations are important because patients with these variations metabolize warfarin slower than patients with CYP2C9*1. In a study among Caucasians, approximately 11% of the patients carried d the CYP2C9*2 and 7% carried the CYP2C9*3 variation. Limited clinical data suggest CYP2C9 genetic variations in non-Caucasians occur less frequently.

Clinical studies have shown that patients with CYP2C9 and VKORC1 genetic variations require lower warfarin initial and maintenance dose to stay within the target INR. Future clinical studies are expected to identify which initial warfarin doses are most appropriate for people with different CYP2C9 and VKORC1 gene variants. Many of these studies are described at the internet address of: www.clinicaltrials.gov (using the "warfarin" search term).

If a patient has one of these genetic variations, does it mean the patient is more likely to bleed if given warfarin?

The available clinical data suggests that the patient is at an increased risk for bleeding. Not all patients with one or more gene variants in either CYP2C9 or VKORC1 will bleed, nor will all patients without gene variants avoid a bleeding episode. Careful INR monitoring is essential to maintain INR control in all patients irrespective of their genetic and non-genetic factors.

Can a patient's response to warfarin be affected by factors other than genetic variations in CYP2C9 or VKORC1?

Yes, a patient's response to warfarin may be affected by many factors, such as age, body surface area (weight and height), hypertension, serious heart disease, concomitant drugs that interact with warfarin, renal status, past history of bleeding if any, and food that could interfere with warfarin absorption or anticoagulation response.

What is personalized medicine?

Personalized medicine is a term that has been applied to clinical practice when a doctor uses information about a patient's genotype or gene expression along with other information such as the physical exam, medical history, age, race, gender, co-administered drugs to select a medicine or a dose of a medical product that is thought to be best suited for that patient. The promise of personalized medicine is to improve the safety and effectiveness of drug therapy in an individual patient.

How does the coumadin labeling change fit into this strategy?

The label change highlights the opportunity for healthcare providers to use genetic tests to improve their initial estimate of a reasonable warfarin dose for a specific patient; this process may optimize the use of warfarin and lower the risk for bleeding.

As a patient on warfarin, you now have the option of checking your PT/INR at home, anytime. Visit website at mdinr.com and see whether this is an option that would work for you.

It is essential that you understand as much about this medication as you can.

WHAT IS WARFARIN?

Warfarin (brand name Coumadin®) is a prescription medication that inhibits normal blood clotting (coagulation). Because it interferes with the formation of blood clots, it is also called an anticoagulant. Many people refer to these kinds of medicines as blood thinners, although they do not actually cause the blood to become less thick, only less likely to clot.

The normal clotting mechanism is a complex process that involves multiple substances (clotting factors). These factors are produced by the liver and act in sequence to form a blood clot. In order for the liver to produce a number of the clotting factors, adequate amounts of vitamin K must be available. Warfarin blocks the availability of vitamin K, and limits the production of these clotting factors. As a result, the clotting mechanism is disrupted and it takes longer for the blood to clot.

USES

Normally, when body tissues are cut or traumatized, the blood clots in order to prevent excessive blood loss. In some patients, however, the clotting mechanism may be triggered by other factors, leading to the formation of small clots (thrombi) in the bloodstream. These clots may travel through the bloodstream and become lodged in smaller blood vessels, reducing blood flow to the organs supplied by those vessels. Blockage of blood flow can cause serious problems including stroke (when a blood vessel leading to a portion of the brain is blocked) and heart attack (when a blood vessel leading to the heart is blocked).

Warfarin is prescribed for patients who are at increased risk for developing harmful blood clots. Patients at risk for developing such clots include those with a mechanical heart valve, an irregular heart rhythm called atrial fibrillation, and patients with certain clotting disorders. (See "Patient information: Atrial fibrillation").

Warfarin is also used in patients who have previously developed harmful clots, including patients who have had a stroke, heart attack, a clot which has traveled to the lung (pulmonary embolism), or a blood clot in the leg (deep venous thrombosis or DVT). In addition, warfarin may be used to prevent an existing clot from growing larger. (See "Patient information: Venous thrombosis").

MONITORING

The goal of warfarin therapy is to decrease the clotting tendency of blood, but not to prevent clotting completely. Therefore, the effect of warfarin on the blood's ability to clot must be carefully monitored with periodic blood testing. Based on the results of these tests, the dose of warfarin is adjusted to maintain the clotting time within a target range.

Prothrombin time (PT) — The test most commonly used to measure the effects of warfarin is the prothrombin time (called pro time, or PT). The PT is a laboratory test that measures the time it takes for the clotting mechanism to progress. It is particularly sensitive to the clotting factors affected by warfarin. The PT is also used to compute a value known as the INR (or International Normalized Ratio).

International Normalized Ratio (INR) — The INR is a way of expressing the PT in a standardized way; this ensures that results obtained by different laboratories can be reliably compared.

The longer it takes the blood to clot, the higher the PT and INR. The target INR range depends upon the clinical situation. In most cases the target range will be 2 to 3, although other ranges may be chosen if there are special circumstances. If, at any particular time, the INR is below the target range (ie, under-anticoagulated), there is a risk of clotting. If, on the other hand, the INR is above the target range (ie, over-anticoagulated), there is an increased risk of bleeding.

Dosing — When warfarin is first prescribed, a higher loading dose may be given so that an effective blood level of the drug is achieved quickly. The loading dose is then adjusted downward until a maintenance dose is found that maintains the INR within the desired range. The PT and INR are monitored frequently until the maintenance dose has been determined. Once the patient is on a stable maintenance dose, the PT and INR are monitored less frequently, generally once every two to four weeks.

The warfarin dose may be adjusted periodically in response to a changing INR or to clinical circumstances that call for an increase or decrease in warfarin therapy. For example, having surgery may require a change in a patient's warfarin regimen. The dose of warfarin may also be modified if other medicines are taken.

SIDE EFFECTS

The major complication associated with warfarin is bleeding due to excessive anticoagulation. Excessive bleeding, or hemorrhage, can occur from any area of the body, and patients on warfarin should report any falls or accidents, as well as signs or symptoms of bleeding or unusual bruising. Signs of unusual bleeding include bleeding from the gums, blood in the urine, bloody or dark stool, a nosebleed, or vomiting blood. Because the risk of bleeding increases as the INR rises, the INR is closely monitored and adjustments are made as needed to maintain the INR within the target range.

Warfarin can also cause skin necrosis or gangrene, manifested by dark red or black lesions on the skin. This is a rare complication that may occur during the first several days of warfarin therapy.

When to seek help — If there are obvious or subtle signs of bleeding, including the following, patients should call their healthcare provider immediately.

- Persistent nausea, gastrointestinal upset, or vomiting blood or other material that looks like coffee grounds

- Headaches, dizziness, or weakness

- Nosebleeds

- Dark red or brown urine

- Blood in the bowel movement or dark-colored stool

- Pain, discomfort, or swelling, especially after an injury

- After a serious fall or head injury, even if there are no other symptoms

- Bleeding from the gums after brushing the teeth

- Swelling or pain at an injection site

- Excessive menstrual bleeding or bleeding between menstrual periods

- Diarrhea, vomiting, or inability to eat for more than 24 hours

- Fever (temperature greater than 100.4º F or 38º C)

PREGNANCY AND WARFARIN

Warfarin is not recommended during pregnancy, especially during the first trimester, due to an increased risk of miscarriage and birth defects. A patient who becomes pregnant or plans to become pregnant while on warfarin therapy should notify their healthcare provider immediately.

Breastfeeding — Although warfarin does not pass into breast milk, a woman who wishes to breastfeed while taking warfarin should also consult her healthcare provider. Warfarin is considered safe for use in women who breastfeed.

OTHER RECOMMENDATIONS

Take warfarin on a schedule — Warfarin should be taken exactly as directed. Do not increase, decrease, or change the dosing schedule unless told to do so by a healthcare provider. If a dose is missed or forgotten, call the prescribing clinician for advice.

Warfarin tablets come in different strengths; each is usually a different color, with the amount of warfarin (in milligrams) clearly printed on the tablet. If the color or dose of the tablet appears different than those taken previously, the patient should immediately notify their pharmacist or healthcare provider.

Reduce the risk of bleeding —

There is a tendency to bleed more easily than usual while taking warfarin. Some simple changes can decrease this risk:

- Use a soft bristle toothbrush

- Floss with waxed floss rather than unwaxed floss

- Shave with an electric razor rather than a blade

- Take care when using sharp objects, such as knives and scissors

- Avoid activities that have a risk of falling or injury (eg, contact sports)

Falling may significantly increase the risk of bleeding. Taking measures to prevent falls is recommended, and could include the following:

- Remove loose rugs and electrical cords or any other loose items in the home that could lead to tripping, slipping, and falling.

- Ensure that there is adequate lighting in all areas inside and around the home, including stairwells and entrance ways.

- Avoid walking on ice, wet or polished floors, or other potentially slippery surfaces.

- Avoid walking on unfamiliar areas outside.

Some foods and supplements can interfere with warfarin's effectiveness. After being stabilized on a particular warfarin dose, consult a healthcare provider before making major dietary changes (eg, starting a diet to lose weight, starting a nutritional supplement or vitamin).

- Vitamin K— Eating an increased amount of foods rich in vitamin K can lower the prothrombin time and INR, making warfarin less effective, and potentially increasing the risk of blood clots. Patients who take warfarin should aim to eat a relatively similar amount of vitamin K each week. Some foods have a high level of vitamin K, including: kale, broccoli, spinach, collard or turnip greens, lettuce, Brussels sprouts, and cabbage. It is not necessary to avoid these foods. However, the patient should eat a relatively similar amount on a regular basis rather than eating a large serving occasionally.

- Cranberry juice — There have been mixed reports on the effect of cranberry juice in people who use warfarin to prevent blood clots. Some experts have reported that drinking cranberry juice while on warfarin can cause significant over anticoagulation and bleeding. However, a small study found that drinking one eight ounce serving of cranberry juice per day for seven days had no effect on the INR of seven men taking warfarin for atrial fibrillation. It is plausible that larger amounts could have a more significant effect.

- Alcohol — Chronic abuse of alcohol affects the body's ability to handle warfarin. Patients on warfarin therapy should avoid drinking alcohol on a daily basis. Alcohol should be limited to no more than one to two servings of alcohol occasionally. In addition, drinking excessive amounts of alcohol can increase the risk of injury, and therefore bleeding.

A number of medications, herbs, and vitamins can interact with warfarin (show table 1 and show table 2). This interaction may affect the action of warfarin or the other medication. If warfarin is affected, the dose may need to be adjusted (up or down) to maintain an optimal coagulation effect.

Patients who take warfarin should consult with their clinician before taking any new medication, including over-the-counter (non-prescription) drugs, herbal medicines, vitamins, or any other products. Some of the most common over-the-counter pain relievers, including acetaminophen (Tylenol®), aspirin, and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (such as ibuprofen [Advil®]) and naproxen (Aleve®), enhance the anticoagulant effects of warfarin. Vitamin E may increase the anticoagulant effects of warfarin. Consult a healthcare provider before adding or changing a dose of vitamin E or any other vitamin.

Wear medical identification —

People who require long-term warfarin should wear a bracelet, necklace, or similar alert tag at all times. If an accident occurs and the person is too ill to explain their condition, this will help responders provide appropriate care.

The alert tag should include a list of major medical conditions and the reason warfarin is needed (eg, atrial fibrillation), as well as the name and phone number of an emergency contact. One device, Medic Alert®, provides a toll-free number that emergency medical workers can call to find out a person's medical history, list of medications, family emergency contact numbers, and healthcare provider names and numbers.

Karen A Valentine, MD, PhD

Russell D Hull, MBBS, MSc

UpToDate Patient Information

What is warfarin and the recently approved change in the label for the drug?

Warfarin is a drug prescribed to help prevent blood clots. Following oral ingestion, it acts by blocking the action of certain proteins that cause blood to clot. Since warfarin acts to keep blood from clotting, one of the side effects of the drug is an increased risk for bleeding. This risk increases importantly if patients receive too much warfarin. Patients frequently differ in the dose of warfarin necessary to prevent blood clots and also differ in the risk for bleeding.

The recently approved change in the warfarin label provides information on how people with certain genetic differences may respond to warfarin. Specifically, people with variations in two genes may need lower warfarin doses than people without these genetic variations. The two genes are called CYP2C9 and VKORC1. The CYP2C9 gene is involved in the breakdown (metabolism) of warfarin and the VKORC1 gene helps regulate the ability of warfarin to prevent blood from clotting.

How will this new warfarin label information benefit patients?

This information will benefit patients because it will describe why patients with a variation in the CYP2C9 and/or VKORC1 genes may need a lower warfarin dose than patients with the usual forms of these genes. For patients with these genetic variations, the new label information may help physicians prescribe the correct warfarin dose and also encourage them to give increased attention to how these patients respond to warfarin. Identification of patients with these genetic variations is thought to improve the safe use of warfarin since choosing the correct warfarin dose is important to prevent blood clots and avoid bleeding.

How might healthcare professionals use this information in their practice?

Healthcare professionals might incorporate the genetic information on CYP2C9 and VKORC1, along with various clinical considerations and patient characteristics (e.g., age, body weight) to better estimate the initial warfarin doses for patients. Warfarin is often administered daily and the response to the drug is mainly measured by a laboratory test result called the INR. The INR measures, in part, the blood's ability to clot and the INR should be performed regularly in all patients receiving warfarin. Genetic information does not replace regular INR testing.

Response to warfarin and the risk for bleeding may be influenced by many factors, such as the presence of serious underlying heart disease or the simultaneous use of other drugs which can interact with warfarin. These clinical considerations impact the healthcare professional's decision to prescribe warfarin as well as the selection of the initial warfarin dosages. The recently revised warfarin product label adds CYP2C9 and VKORC1 genetic variations to the list of these clinical considerations for warfarin use. The label's specific warfarin dose recommendations have not changed.

Will healthcare professionals be required to test patients for these genetic variations prior to prescribing warfarin?

No, healthcare professionals are not required to conduct CYP2C9 and VKORC1 testing before initiating warfarin therapy, nor should genetic testing delay the start of warfarin therapy.

Are tests available to detect variations in the CYP2C9 and/or VKORC1 genes?

Yes, laboratory developed tests are available to determine if a patient has certain CYP2C9 and/or VKORC1 gene variants that may influence the response to warfarin. The availability and reliability of these tests may vary from lab to lab and healthcare professionals should check with their local or reference clinical laboratory to obtain more information about the specific tests.

What did clinical studies show to support the addition of genetic information to the warfarin label?

Clinical studies have suggested that patients with CYP2C9*2 and CYP2C9*3 genetic variations are at an increased risk for bleeding with warfarin therapy. In these studies, patients with these variants generally required lower doses of warfarin to achieve a desired INR control and decrease the risk of bleeding .

In general, more limited information is available for VKORC1 genetic variations than for CYP2C9. Among the more notable studies was the importance of VKORC1 detected in a study of 201 Caucasian patients who needed a wide variation in warfarin doses to maintain an acceptable INR test. Of the factors that were examined to determine why the dose varied so much, the presence of a VKORC1 genetic variation was thought to be responsible for 30% of the warfarin dose variation. The presence of either a VKORC1 or a CYP2C9 variation was thought to be responsible for 40% of the warfarin dose variation. Other non-genetic factors, such as age and weight, were responsible for 10% to15% of warfarin dose variation.

Published studies have estimated the prevalence of CYP2C9 and VKORC1 gene variants in a number of ethnic groups. These studies have estimated the frequency of CYP2C9 gene variants, or genotypes, that may influence warfarin doses at approximately 10% to 20% in Caucasians and African-Americans. For the same populations the frequency of important genotypes of VKORC1 is 14% to 37%. The frequency of the important VKORC1 genotype in the Asian population has been reported to be as high as 89%.

The usual genetic form of CYP2C9 with normal enzyme activity is called CYP2C9*1. Studies indicate that the CYP2C9*2 and CYP2C9*3 genetic variations are important because patients with these variations metabolize warfarin slower than patients with CYP2C9*1. In a study among Caucasians, approximately 11% of the patients carried d the CYP2C9*2 and 7% carried the CYP2C9*3 variation. Limited clinical data suggest CYP2C9 genetic variations in non-Caucasians occur less frequently.

Clinical studies have shown that patients with CYP2C9 and VKORC1 genetic variations require lower warfarin initial and maintenance dose to stay within the target INR. Future clinical studies are expected to identify which initial warfarin doses are most appropriate for people with different CYP2C9 and VKORC1 gene variants. Many of these studies are described at the internet address of: www.clinicaltrials.gov (using the "warfarin" search term).

If a patient has one of these genetic variations, does it mean the patient is more likely to bleed if given warfarin?

The available clinical data suggests that the patient is at an increased risk for bleeding. Not all patients with one or more gene variants in either CYP2C9 or VKORC1 will bleed, nor will all patients without gene variants avoid a bleeding episode. Careful INR monitoring is essential to maintain INR control in all patients irrespective of their genetic and non-genetic factors.

Can a patient's response to warfarin be affected by factors other than genetic variations in CYP2C9 or VKORC1?

Yes, a patient's response to warfarin may be affected by many factors, such as age, body surface area (weight and height), hypertension, serious heart disease, concomitant drugs that interact with warfarin, renal status, past history of bleeding if any, and food that could interfere with warfarin absorption or anticoagulation response.

What is personalized medicine?

Personalized medicine is a term that has been applied to clinical practice when a doctor uses information about a patient's genotype or gene expression along with other information such as the physical exam, medical history, age, race, gender, co-administered drugs to select a medicine or a dose of a medical product that is thought to be best suited for that patient. The promise of personalized medicine is to improve the safety and effectiveness of drug therapy in an individual patient.

How does the coumadin labeling change fit into this strategy?

The label change highlights the opportunity for healthcare providers to use genetic tests to improve their initial estimate of a reasonable warfarin dose for a specific patient; this process may optimize the use of warfarin and lower the risk for bleeding.

- You must know the dosage strength of the warfarin/Coumadin tablets that you have.

- You must know the dosage strength that you actually take.

- You must take your warfarin/Coumadin exactly as prescribed.

- Always take after 7:00 pm.

- Have your PT/INR checked regularly (at least once a month) when you are in a stable state.

- Call by 4pm to find out what dose adjustment needs to be made.

- INR goals: 2 to 3.0 for atrial fibrillation and deep vein thrombosis. 3 to 3.5 for a mechanical heart valve

- If you experience any excessive bruising or bleeding, your PT/INR needs to be checked urgently. Don't wait for your next scheduled blood test!

As a patient on warfarin, you now have the option of checking your PT/INR at home, anytime. Visit website at mdinr.com and see whether this is an option that would work for you.