- RETIREMENT ANNOUNCEMENT

- HOME PAGE

- "MYCHART" the new patient portal

- BELMONT MEDICAL ASSOCIATES

- MOUNT AUBURN HOSPITAL

- EMERGENCIES

- PRACTICE PHILOSOPHY

- MY RESUME

- TELEMEDICINE CONSULTATION

- CONTACT ME

- LAB RESULTS

- ePRESCRIPTIONS

- eREFERRALS

- RECORD RELEASE

- MEDICAL SCRIBE

- PHYSICIAN ASSISTANT (PA)

- Medicare Annual Wellness Visit

- Case management/Social work

- Quality Care Measures

- Emergency closing notice

- FEEDBACK

- Talking to your doctor

- Choosing..... and losing a doctor

- INDEX A - Z

- ALLERGIC REACTIONS

- Alternative Medicine

- Alzheimer's Disease

- Bladder Problems

- Blood disorders

- Cancer Concerns

- GENETIC TESTING FOR HEREDITARY CANCER

- Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

- Controversial Concerns

- CPR : Learn and save a life

- CRP : Inflammatory marker

- Diabetes Management

- Dizziness, Vertigo,Tinnitus and Hearing Loss

- EXERCISE

- FEMALE HEALTH

-

GASTROINTESTINAL topics

- Appendicitis

- BRAT diet

- Celiac Disease or Sprue

- Crohn's Disease

- Gastroenterologists for Colon Cancer Screening

- Colonoscopy PREP

- Constipation

- Gluten sensitivity, but not celiac disease

- Heartburn and GERD

- Hemorrhoids and Anal fissure

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- NASH : Non Alcoholic Steato Hepatitis

- FEET PROBLEMS

- HEART RELATED topics

-

INFECTIOUS DISEASES

- Antibiotic Resistance

- Cat bites >

- Clostridia difficile infection - the "antibiotic associated germ"

- CORONA VIRUS

- Dengue Fever and Chikungunya Fever

- Food borne illnesses

- Shingles Vaccine

- Hepatitis B

- Hepatitis C

- Herpes

- Influenza

- Helicobacter pylori - the "ulcer germ"

- HIV Screening

- Lyme and other tick borne diseases

- Measles

- Meningitis

- MRSA (Staph infection)

- Norovirus

- Sexually Transmitted Diseases

- Shingles (Herpes Zoster)

- Sinusitis

- West Nile Virus

- Whooping Cough (Pertussis)

- Zika virus and pregnancy

- INSURANCE related topics

- KIDNEY STONES

- LEG CRAMPS

- LIBRARY for patients

- LIFE DECISIONS

- MALE HEALTH

- Medication/Drug side effects

- MEDICAL MARIJUANA

- MENTAL HEALTH

- Miscellaneous Articles

-

NUTRITION - EXERCISE - WEIGHT

- Cholesterol : New guidelines for treatment

- Advice to lower your cholesterol

- Cholesterol : Control

- Cholesterol : Raising your HDL Level

- Exercise

- Food : Making Smart Choices

- Food : Making Poor Choices

- Food : Grape Fruit and Drug Interaction

- Food : Vitamins, Minerals and Supplements

- Omega 3 fatty acids

- Vitamin B12 deficiency

- Vitamin D

- Weight Loss

- ORTHOPEDICS

- PAIN

- PATIENTS' RIGHTS

- SKIN

- SLEEP

- SMOKING

- STROKE

- THYROID

- SUBSTANCE ABUSE

- Travel and Vaccination

- TREMOR

- Warfarin Anticoagulation

- OTHER STUFF FOLLOWS

- Fact or Opinion?

- Hippocratic Oath

- FREE ADVICE.......for what its worth!

- LAUGHTER.....is the best medicine

- Physicians Pet Peeves

- PHOTO ALBUM - its not all work!

- Cape Town, South Africa

- Tribute page

- The 100 Club

- Free Wi-Fi

Heartburn and GERD

Taking heartburn seriously

By Tara Pope : NY Times Article

An epidemic of heartburn has triggered an alarming rise in a deadly cancer, but many people at risk still aren't being screened for the disease.

Esophageal adenocarcinoma, the most common form of cancer of the esophagus, is strongly linked to chronic heartburn and acid reflux. And it is now the fastest-growing cancer in the country. While the overall number of cases is small -- just 8,000 people were diagnosed last year -- the incidence of the disease has surged fivefold in three decades.

Screening people with a history of chronic heartburn can help can detect a dangerous precancerous condition known as Barrett's esophagus. And it can help diagnose many esophageal cancers far earlier, before symptoms arise and when long-term survival chances are the highest. Overall five-year survival of esophageal cancer is only about 15%, but when the cancer is found early, surgical removal of the esophagus and chemotherapy can improve five-year survival to about 70%.

Even so, screening for the disease remains controversial. It's expensive, costing about $1,000 per test, and many experts feel the cost isn't justified given that the vast majority of people with heartburn won't ever develop esophageal cancer. "It hasn't gotten much attention because it's not a Top 10 cancer," says David Metz, a University of Pennsylvania professor of medicine.

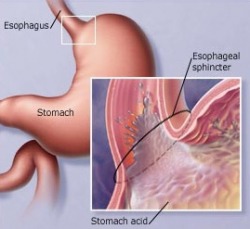

Exactly why esophageal adenocarcinoma is increasing at such a rapid rate isn't clear, but the evidence points to an epidemic of chronic heartburn. Heartburn and reflux occur when stomach acid sloshes up into the esophagus, causing burning pain. It's estimated that 20% of Americans suffer from weekly episodes of heartburn, while 7% suffer bouts every day.

Chronic heartburn, called gastroesophageal reflux disease or GERD, is on the rise for a number of reasons, including greater consumption of fatty foods that can slow the emptying of the stomach. Increased obesity and even moderate weight gain are also factors. Sometimes heredity, bacterial changes in the gut, or general wear and tear on the esophagus can trigger GERD.

The worry about chronic reflux is that years of exposure to stomach acids can trigger changes in the lining of the esophagus, a condition known as Barrett's esophagus, which can eventually lead to cancer.

The most effective treatments for GERD are drugs called proton pump inhibitors, which limit the amount of acid the stomach produces, but the drugs are expensive. Most insurance companies won't pay for long-term use, prompting doctors to recommend less-expensive and less-effective over-the-counter remedies such as antacids.

"There's been this trivialization of GERD -- that it's just heartburn, it's not a big problem," says Mark Sostek, a gastroenterologist and AstraZeneca's medical director for Nexium. "If in another five or 10 years this cancer rate continues to rise, people are going to look back and rue the day that we've been undertreating all these patients."

Antireflux surgery to tighten faulty valves or repair hernias at the base of the esophagus can also stop chronic reflux. Symptoms can return over time, however, and nobody really knows whether the drugs or surgery can slow the progression of Barrett's or prevent the onset of esophageal cancer.

As a result, many doctors are calling for stepped-up surveillance of GERD patients to detect Barrett's, followed by regular screening of patients found to be at higher risk. In the absence of such wide screening, most patients only discover they have the cancer when they develop swallowing problems. By then, the disease often has spread to lymph nodes or to other organs

But there's little agreement on who should be screened and how often. The American College of Gastroenterology suggests screening men over 50 every three years if they have a history of five years or more of chronic reflux and reflux symptoms at least twice a week. Those diagnosed with Barrett's esophagus are checked more often. Screening involves an endoscopy, whereby doctors insert a thin, lighted tube into the throat of a sedated patient to view the esophagus and take biopsy samples. The procedure is simple, but may result in a mild sore throat.

The medical journal Archives of Internal Medicine published a review of the literature last month that supporting screening. But the guidelines miss large numbers of people at risk. One in eight esophageal cancer patients are women. Some GERD patients don't have typical symptoms, suffering from chronic cough rather than typical reflux.

At the same time, the journal Gastroenterology published the findings of a group of experts who concluded there's little medical evidence to support even the current screening, given the cost.

"There's still controversy," says Stuart J. Spechler, professor of medicine at University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas and a leading expert on Barrett's. "Most physicians agree it's a good idea to screen, but it doesn't get practiced a lot for financial reasons."

Until more is known, the best advice is to eat healthful foods, manage your weight, and seek treatment for chronic heartburn. Some early studies have shown that daily aspirin use may cut risk of esophageal cancer, and studies are under way looking at whether the anti-inflammatory drugs known as Cox II inhibitors, like Celebrex, may also help treat Barrett's. Other studies have shown that regular consumption of green tea may lower risk for esophageal cancer, but data are far from conclusive.

Dietary Habits That Improve GERD

- Eating small portions

- Avoid eating certain foods, including onions, chocolate, peppermint, high-fat or spicy foods, citrus fruits, garlic, and tomatoes or tomato-based products

- Avoid drinking certain beverages, including citrus juices, alcohol, coffee, tea, soft drinks, and other caffeinated and carbonated drinks

- Avoid eating or drinking for 3 hours before going to bed

Lifestyle Habits That Improve GERD

- Lose weight (if you are overweight)

- Stop smoking

- Avoid wearing tight-fitting clothing or belts

- Avoid lying down or prolonged bending over, especially after eating

- Avoid straining and constipation

- Elevate the head of your bed 6 to 8 inches

- Avoid Stress

Cancer Risk From Barrett’s Esophagus Lower Than Thought

By Anahad O'Connor : NY Times : October 13, 2011

People who have a condition known as Barrett’s esophagus, a complication of acid reflux disease, have a higher risk of developing esophageal cancer — but the risk is far smaller than widely believed, a new study shows.

Those with Barrett’s esophagus, which affects about a million Americans, have long been encouraged to undergo repeated, invasive screening tests to look for signs of cancer in the cells lining the food pipe. The condition was thought to make cancer of the esophagus up to 40 times as likely.

But the new study found that the risk of esophageal cancer in Barrett’s patients was only about a fifth of what is currently believed. That suggests that the routine tests and endoscopies patients are subjected to may not be necessary in many cases, said Dr. Peter Funch-Jensen, a professor of surgery at Aarhus University in Denmark and an author of the study, which was published this week in The New England Journal of Medicine.

The study is by far the largest and most comprehensive to date on the subject.

“If you combine the data from all other studies, it adds up to about 60,000 patient-years, and our study comes out to about 70,000 patient-years,” Dr. Funch-Jensen said.

To come up with the new estimate, Dr. Funch-Jensen and his colleagues collected data over nearly 20 years on more than 11,000 people in Denmark who had a diagnosis of Barrett’s esophagus. The researchers used Danish medical registries, which contain data on Denmark’s entire population of over five million people, many of them tracked since birth.

The study found that every year, 0.12 percent of the Barrett’s patients — or about one in 860 people — go on to develop cancer of the esophagus, a disease that is particularly lethal. The figure was much lower than the estimate of 0.5 percent stemming from earlier studies.

The new study comes on the heels of a similar report published this year in The Journal of the National Cancer Institute, which looked at a large population in Ireland. That study found the risk of esophageal cancer in people with Barrett’s was 0.13 percent.

According to current guidelines, people with Barrett’s should consider undergoing an endoscopy and biopsy of the esophageal lining about every three years. But the research suggests that Barrett’s patients may not need as many screening procedures. Dr. Funch-Jensen said he believed endoscopies might be unnecessary after the first year except in cases where doctors find precancerous cells, a condition known as dysplasia, or when new symptoms occur.

“Some people will have dysplasia, but that’s only 5 percent of the patients,” he said. “I don’t think the other 95 percent of the patients with no dysplasia need routine surveillance.“

An accompanying editorial agreed with that assessment, saying the problems with close surveillance of Barrett’s patients “lie in the numbers.”

“Patients with Barrett’s esophagus have the same life expectancy as does the general population, and esophageal cancer proves to be an uncommon cause of death in patients with Barrett’s esophagus,” wrote Dr. Peter J. Kahrilas, chief of gastroenterology at the Northwestern University medical school and the author of the editorial. “Currently available evidence has not shown that the current strategy of screening and surveillance of patients with Barrett’s esophagus is cost-effective or reduces mortality from esophageal adenocarcinoma.”

Factors that can help predict disease progression to esophageal cancer include:

- male gender

- caucasian race

- obesity

- smoking

- hiatal hernia (>4cm)

- long Barrett's segment (>3cm)

- family history of Barrett's esophagus or esophageal cancer

- duration of Barrett's (>10years)

A Sigh of Relief for Heartburn Sufferers

By Peter Jaret

NY Times Article : November 8, 2007

Over the last decade, a tide of powerful heartburn medications, many once available only by prescription, has washed over store shelves, helping to introduce gastroesophageal reflux disease -- or GERD, the medical name for persistent heartburn -- into the vocabulary of consumers everywhere. But along with relief has come worry. Many patients fear they are afflicted with an incurable chronic condition that, if left untreated, eventually leads to more serious problems like inflammation or even cancer of the esophagus.

The truth is a little more complicated. And a lot more reassuring.

Heartburn occurs when the valve between the esophagus and the stomach relaxes at the wrong time, allowing stomach acid to spill upwards and cause a burning sensation in the chest or throat. “Almost everyone experiences heartburn now and then,” said Dr. Joel E. Richter, a heartburn expert at Temple University in Philadelphia.

For years it was thought that chronic heartburn inevitably erodes the delicate lining of the esophagus -- damage that can be visually detected through insertion of a flexible tube, or endoscope, down the throat. Over time, the assumption went, that damage leads to esophagitis, or inflammation of the esophagus, and in some cases to a precancerous condition called Barrett’s esophagus.

But new findings show the picture isn’t quite that simple. “People with horrible symptoms of heartburn often don’t turn out to have esophagitis,” said Dr. C. Daniel Smith of the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Fla. “People with no symptoms at all can turn out to have severe damage.”

“Only about 10 to 15 percent of cases are bad GERD, with signs of esophageal damage,” said Dr. Richter. Complications can include breaks in the lining of the esophagus and scar tissue that forms strictures, but these are uncommon. “Eighty-five percent of the time there’s no damage to the esophagus.” Even when there is damage, studies show, it usually doesn’t progress over time.

Of course even uncomplicated heartburn is no picnic. Regurgitating stomach acid is unpleasant. Flare-ups, which frequently occur at night after a big meal, can disrupt sleep. Luckily, with dozens of treatments available, relief is at hand. For occasional heartburn, garden-variety antacids like Tums, Rolaids or Maalox are usually effective. Drugs called H2 blockers, which suppress stomach acid production, are recommended for more serious or frequent heartburn. For the most severe cases, doctors typically recommend drugs called proton pump inhibitors, or P.P.I.’s, which are even more effective at blocking acid formation.

People with documented esophageal damage or very severe and frequent reflux may need to take medication daily. But the majority of heartburn sufferers don’t need to stay on the drugs for extended periods -- though many do, experts say, perhaps partly out of the fears fanned by direct-to-consumer ads.

“Only 7 percent of people with GERD experience symptoms of heartburn on a daily basis,” said Dr. Lauren B. Gerson, an associate professor of medicine at Stanford University. “They may need to stay on medication. But 30 to 40 percent have flare-ups only about once a month.” In that case, they can get by taking antacids or anti-reflux drugs only occasionally, when the symptoms begin or before indulging in the kind of meal that typically ignites heartburn.

Judicious use of heartburn drugs not only saves money but lowers the risk of untoward side effects. Although heartburn drugs are considered very safe, a 2006 study at the University of Pennsylvania found a 2.6-fold increase in the risk of hip fractures associated with long-term use of proton pump inhibitors. Other studies point to a higher risk of gastrointestinal infections. “These are risks worth taking if you have bad reflux, but not if you don’t really need to take the drugs,” said Dr. Richter.

The best medicine, of course, is prevention. Almost everyone seems to have a pet theory about what causes their heartburn -- spicy foods, coffee, chocolate or alcohol among them. Doctors often tell patients to eliminate certain foods. After years of hearing her colleagues dole out such advice, often to little effect, Dr. Gerson decided to look at the evidence. “Unfortunately, there wasn’t much,” she said. “There’s almost no evidence that cutting out certain foods, giving up alcohol or even quitting smoking had any effect on heartburn.”

One common piece of advice, raising the head of the bed, does seem to reduce episodes of reflux at night slightly. Losing weight if you’re overweight may also help, since excess body fat may put more pressure on the valve between the stomach and esophagus. Hormonal changes associated with excess fat may also make the valve relax when it shouldn’t. Similar hormone fluctuations are the reason many women experience heartburn during pregnancy.

Preventing heartburn provides one more reason to lose weight, though most people probably won’t. Given the nation’s expanding waistline, more and more of us are likely to find ourselves reaching for a heartburn remedy. At least it’s reassuring to know that a little bit of discomfort is all most of us have to worry about.

The Claim: Chewing Gum After a Meal Can Prevent Heartburn

By Ahanad O'Connor : NY Times Article : July 31, 2007

THE FACTS :

The list of ideas for easing heartburn is long and filled with home remedies, many unproved. But one of the simplest, chewing gum, may be among the most effective.

Heartburn results from digestive fluids’ traveling from stomach to esophagus in a process known as gastroesophageal reflux. When scientists set out to study whether this could be countered by chewing gum, they assumed the answer would be no. Instead they found that the saliva stimulated by chewing seemed to neutralize acid and help force fluids back to the stomach.

In a study published in The Journal of Dental Research in 2005, researchers had 31 people eat heartburn-inducing meals and then asked random subjects to chew sugar-free gum for 30 minutes. Acid levels after the meals were significantly lower when the participants chewed gum.

A similar study in 2001 compared the effects of chewing gum after a large breakfast in people with gastroesophageal reflux and in those without it. It found that the beneficial effects of chewing gum on heartburn lasted up to three hours, “with a more profound effect in refluxers than in controls.”

Another option is antacid chewing gums. One study in 2002, by scientists at the nonprofit Oklahoma Foundation for Digestive Research, found that antacid chewing gum was more effective after a meal than chewable tablets.

THE BOTTOM LINE :

Studies show that chewing gum after a meal can significantly reduce the severity of heartburn.

Esophageal Therapy You Can Stomach

By Melinda Beck

WSJ Article : May 20, 2008

Got heartburn? Several times a week for five or more years? Then you're at increased risk for a form of esophageal cancer that, though rare, is the fastest-growing cancer in the U.S., particularly in white men over 50. It's also one of the most deadly, with a five-year survival rate of just 17%.

Doctors can sometimes see the cancer coming years earlier when acid reflux causes cells in the esophagus to mutate to become more like stomach tissue, a condition called Barrett's esophagus. In adenocarcinoma, the Barrett's cells keep mutating into cancer.

The standard treatment for Barrett's has been to watch for precancerous changes called dysplasia, and in some cases remove the patient's esophagus. But a new outpatient procedure that lets doctors zap Barrett's tissue with radiofrequency ablation (RFA) is showing promise.

At a conference of gastroenterologists in San Diego on Monday, researchers presented interim results from a multi-center trial showing that among patients treated with RFA, 85% were free of dysplasia, and 74% were free of all signs of Barrett's, 12 months later. None of the treated patients progressed to high-grade dysplasia or cancer. In the control group, several patients got worse, and none was free of Barrett's.

Other studies showed that RFA caused few side effects and that genetic changes in the esophagus returned to normal afterward.

"It's way cool. It's far and away the most effective endoscopic treatment that we've ever had," says Nicholas Shaheen, director of the Center for Esophageal Disease and Swallowing at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill School of Medicine and the lead investigator.

The RFA procedure involves no incisions, but the patient is sedated. A gastroenterologist inserts a tiny camera, along with a sizing balloon, down the patient's esophagus. A second balloon delivers a short burst of energy that burns out the Barrett's tissue, which appears rough and red in contrast to healthy pink tissue. The technology, called the HALO Ablation System, is made by BÂRRX Medical Inc., a privately held company in Sunnyvale, Calif.

The RFA procedure is usually repeated a few months later, with a smaller HALO device. "It's like removing old wallpaper -- you do a big stripping and then go back and remove any bits that are left," says Charles Lightdale, a gastroenterologist at NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital/Columbia, who also consults for BÂRRX.

To date, about 16,000 RFA procedures have been performed since 2001; it's available at about 200 centers in the U.S., and covered by Medicare and most insurers. It's too soon to know whether the Barrett's will return in the long run. Patients are usually kept on acid-blocking drugs.

No one knows why adenocarcinoma of the esophagus is rising so fast -- up sixfold in the U.S. since 1975. It appears to be related to obesity, especially belly fat, which puts pressure on the abdomen. Another form of esophageal cancer, squamous cell, linked to alcohol and tobacco use, is declining in the U.S.

An estimated 3.3 million Americans have Barrett's. Only about 1 in every 200 of them will develop esophageal cancer. But people with high-grade dysplasia have a much higher risk.

For them, RFA appears to be a good alternative to an esophagectomy, a grueling operation that severely restricts eating. A big question now is whether people with earlier stages of Barrett's should be treated with RFA, which is still new and costly, or just watched with endoscopes and biopsies.

"This is very safe and effective therapy," says Dr. Shaheen, who gets no remuneration from BÂRRX. "But as we move from high-risk to lower-risk patients, the calculus changes."

Some patients are eager to eliminate the cancer risk. Louis Plzak, a retired thoracic surgeon from Philadelphia, had monitored his Barrett's for several years when he learned about RFA at a surgical conference and decided to have it done preventatively. "This will allow me to start living without the fear of Barrett's," says Dr. Plzak, age 74.

If you're having reflux several times a week, if you need medicine to control it or if you had it in the past, see a gastroenterologist. Chronic heartburn may stop once Barrett's sets in, since the mutated tissue isn't as sensitive to reflux. Controlling your weight will also help cut your risk of esophageal cancer.

Finding, and Treating, Esophageal Cancer

By Jane E. Brody

NY Times Article : December 2, 2008

Half a century ago, my grandmother died of esophageal cancer. For decades preceding her death, a bottle of milk of magnesia was her steady companion because she suffered daily from heartburn, now known as gastroesophageal reflux disease, or GERD. But many years passed before a link was clearly established between chronic irritation of the esophagus by stomach acid and this usually fatal cancer.

Now that the role of acid reflux is well known in cancer risk and unpleasant conditions like chronic cough and hoarseness, drug companies market several products, prescription and over the counter, that are far better able to control the backup of stomach acid than milk of magnesia. And gastroenterologists now know to be on the alert for early signs of trouble among patients who suffer from GERD.

The cancer that results from chronic reflux is preceded by a benign condition called Barrett’s esophagus, a cellular abnormality of the esophageal lining that can become precancerous. If untreated, about 10 percent of patients with Barrett’s esophagus eventually develop esophageal cancer, the nation’s fastest-growing cancer. In the last four decades, the annual number of new cases has risen 300 to 500 percent.

The American Cancer Society estimates that 16,470 new cases of esophageal cancer will be diagnosed in this country this year and that more than 14,000 people will die from it.

Diagnosed early, well before patients develop swallowing problems, esophageal cancer is usually curable. A cure is most certain if the problem is detected and corrected before or during the advanced precancerous stage. But for about 90 percent of patients, early detection and treatment are missed, and the outcome is fatal.

Detecting Trouble

Unfortunately, the esophagus, unlike more accessible body parts like the breast and skin, is not very easy to monitor. In the traditional exam, called gastrointestinal endoscopy, the patient is heavily sedated, usually in a hospital, and a scope the diameter of a garden hose is inserted through the mouth into the esophagus.

For patients with GERD who have already developed Barrett’s esophagus, annual endoscopy is recommended to check on the health of esophageal cells. If a biopsy indicates an impending or existing cancer, the usual treatment is a rather challenging operation in which all or part of the esophagus and the upper part of the stomach are removed and the remaining parts of the digestive tract are reattached.

Another technique uses light therapy to destroy the inner lining of the esophagus, which can result in scarring and strictures that impede swallowing.

After this treatment, patients must stay out of sunlight and direct artificial light for about six weeks to avoid a severe sunburn on exposed skin.

New Methods

But now there are simpler and safer alternatives for both detecting and treating an esophageal problem even before it becomes a serious precancer.

A colleague who suffers from chronic reflux recently underwent the new detection method, called TransNasal Esophagoscopy, or T.N.E. It can be done safely and effectively in a doctor’s office, and it does not require sedation or involve loss of a day’s work. Nor does it leave the patient with a sore throat.

“Surprisingly easy,” was how my colleague described it. “I had an exam that involved sending a tube, slim as a wire, with a camera, down through a nostril.”

His doctor, Dr. Jonathan E. Aviv, medical director of the Voice and Swallowing Center at NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital/Columbia University Medical Center, said he and other ear, nose and throat doctors around the country started using the technique in the mid-1990s.

“Patients are examined awake, sitting upright in a chair,” Dr. Aviv said in an e-mail message. “An ultrathin flexible scope, the size of a shoelace, is placed via the patient’s numbed nose past the throat and then into the esophagus, thereby avoiding the powerful gag reflex which sits in the mouth.”

Dr. Aviv described the technique as a triple bonus: one that avoids the risk of anesthesia and loss of work time for patients, increases the efficiency of medical practice for doctors and reduces the costs to insurers.

Even newer than T.N.E. is a technique that can both diagnose and, using radiofrequency energy, treat abnormal cells.

Joseph Broderick of Hudson, Fla., had suffered for years with periodic attacks of reflux, especially after eating spicy foods.

“I had a bottle of Maalox at the ready to quiet it down,” Mr. Broderick, 77, said in an interview.

At his doctor’s suggestion, he underwent a traditional endoscopy and esophageal biopsy, which revealed the presence of Barrett’s esophagus. He was prescribed medical, dietary and behavioral treatment to control reflux and told to return a year later for another test.

But before the second test, he began having pain in his chest. This time, the endoscopy and biopsy found advanced dysplasia, a cellular abnormality that can progress to cancer without warning. A repeat exam three months later found no improvement, and an operation was recommended.

First Mr. Broderick sought a second opinion from Dr. John E. Carroll, a gastroenterologist and assistant professor of medicine at Georgetown University Medical Center. Given the treatment options, Mr. Broderick said the choice was a no-brainer: burn out the precancerous cells with radiofrequency energy before they become invasive cancer.

The therapy uses a device, produced by BARRX Medical of Sunnyvale, Calif., that fits on the tip of a gastroscope, with a balloon that expands to fill the esophagus. The device, which has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration, is coupled to a generator that emits radiofrequency energy deep enough to burn off the inner lining of the esophagus. Normal esophageal cells then form to replace the destroyed cells.

Prevention

In a report published this year in the journal Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, cellular abnormalities were eliminated in 98 percent of 70 patients with Barrett’s esophagus who were treated at eight medical centers around the country. The improvement lasted the duration of the study, up to two and a half years.

In a second study by the same multicenter group, 142 patients with advanced dysplasia were treated. The precancerous condition was eliminated in 90 percent, and the Barrett’s cells were destroyed in 54 percent of the patients at one year.

The question now is whom to treat with this technique, since most people with Barrett’s esophagus never get the cancer.

“The trouble is, there’s no predicting which patients will progress to cancer, and when they do, it’s a major cancer that spreads quickly,” Dr. Carroll said. “So I believe this will become a treatment option for most patients with Barrett’s.”

The Claim:

Lying on Your Left Side Eases Heartburn

By Anahad O'Connor : NY Times : October 25, 2010

THE FACTS:

For people with chronic heartburn, restful sleep is no easy feat. Fall asleep in the wrong position, and acid slips into the esophagus, a recipe for agita and insomnia.

Doctors recommend sleeping on an incline, which allows gravity to keep the stomach’s contents where they belong. But sleeping on your side can also make a difference — so long as you choose the correct side. Several studies have found that sleeping on the right side aggravates heartburn; sleeping on the left tends to calm it.

The reason is not entirely clear. One hypothesis holds that right-side sleeping relaxes the lower esophageal sphincter, between the stomach and the esophagus. Another holds that left-side sleeping keeps the junction between stomach and esophagus above the level of gastric acid.

In a study in The Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology, scientists recruited a group of healthy subjects and fed them high-fat meals on different days to induce heartburn. Immediately after the meals, the subjects spent four hours lying on one side or the other as devices measured their esophageal acidity. Ultimately, the researchers found that “the total amount of reflux time was significantly greater” when the subjects lay on their right side.

“In addition,” they wrote, “average overall acid clearance was significantly prolonged with right side down.”

In another study, this one in The American Journal of Gastroenterology, scientists fed a group of chronic heartburn patients a high-fat dinner and a bedtime snack, then measured reflux as they slept. The right-side sleepers had greater acid levels and longer “esophageal acid clearance.” Other studies have had similar results.

THE BOTTOM LINE:

Lying on your right side seems to aggravate heartburn.

Lying on Your Left Side Eases Heartburn

By Anahad O'Connor : NY Times : October 25, 2010

THE FACTS:

For people with chronic heartburn, restful sleep is no easy feat. Fall asleep in the wrong position, and acid slips into the esophagus, a recipe for agita and insomnia.

Doctors recommend sleeping on an incline, which allows gravity to keep the stomach’s contents where they belong. But sleeping on your side can also make a difference — so long as you choose the correct side. Several studies have found that sleeping on the right side aggravates heartburn; sleeping on the left tends to calm it.

The reason is not entirely clear. One hypothesis holds that right-side sleeping relaxes the lower esophageal sphincter, between the stomach and the esophagus. Another holds that left-side sleeping keeps the junction between stomach and esophagus above the level of gastric acid.

In a study in The Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology, scientists recruited a group of healthy subjects and fed them high-fat meals on different days to induce heartburn. Immediately after the meals, the subjects spent four hours lying on one side or the other as devices measured their esophageal acidity. Ultimately, the researchers found that “the total amount of reflux time was significantly greater” when the subjects lay on their right side.

“In addition,” they wrote, “average overall acid clearance was significantly prolonged with right side down.”

In another study, this one in The American Journal of Gastroenterology, scientists fed a group of chronic heartburn patients a high-fat dinner and a bedtime snack, then measured reflux as they slept. The right-side sleepers had greater acid levels and longer “esophageal acid clearance.” Other studies have had similar results.

THE BOTTOM LINE:

Lying on your right side seems to aggravate heartburn.

RISKS OF LONG TERM USE OF PROTON PUMP INHIBITORS

- Vitamin B12 deficiency

- Iron deficiency

- Magnesium deficiency

- Calcium deficiency

- Increased risk of certain infections (Clostridium difficile) because acid in the stomach is necessary for sterilizing gastric contents

CHRONIC HEARTBURN SHOULD NOT BE IGNORED

For a patient who is diagnosed with Barrett’s esophagus, who has

undergone a second endoscopy that confirms the absence of dysplasia on biopsy, a follow-up surveillance examination should not be performed in less than three years as per published guidelines.

For pharmacological treatment of patients with gastroesophageal

reflux disease (GERD), long-term acid suppression therapy (proton pump inhibitors or histamine2 receptor antagonists) should be titrated to the lowest effective dose needed to achieve therapeutic goals.

The main identifiable risk associated with reducing or discontinuing acid suppression therapy is an increased symptom burden. It follows that the decision regarding the need for (and dosage of) maintenance therapy is driven by the impact of those residual symptoms on the patient’s quality of life rather than as a disease control measure.

Combating Acid Reflux May Bring Host of Ills

Roni Caryn Rabin : NY Times : June 25, 2012

The first time Jolene Rudell fainted, she assumed that the stress of being in medical school had gotten to her. Then, two weeks later, she lost consciousness again.

Blood tests showed Ms. Rudell's red blood cell count and iron level were dangerously low. But she is a hearty eater (and a carnivore), and her physician pointed to another possible culprit: a popular drug used by millions of Americans like Ms. Rudell to prevent gastroesophageal acid reflux, or severe heartburn.

Long-term use of the drugs, called proton pump inhibitors, or P.P.I.'s, can make it difficult to absorb some nutrients. Ms. Rudell, 33, has been taking these medications on and off for nearly a decade. Her doctor treated her anemia with high doses of iron, and recommended she try to manage without a P.P.I., but that's been difficult, she said. "I'm hoping I'll get off the P.P.I. after I complete my residency training," she said, "but that's still several years away."

As many as four in 10 Americans have symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease, or GERD, and many depend on P.P.I.'s like Prilosec, Prevacid and Nexium to reduce stomach acid. These are the third highest-selling class of drugs in the United States, after antipsychotics and statins, with more than 100 million prescriptions and $13.9 billion in sales in 2010, in addition to over-the-counter sales.

But in recent years, the Food and Drug Administration has issued numerous warnings about P.P.I.'s, saying long-term use and high doses have been associated with an increased risk of bone fractures and infection with a bacterium called Clostridium difficile that can be especially dangerous to elderly patients. In a recent paper, experts recommended that older adults use the drugs only "for the shortest duration possible."

Studies have shown long-term P.P.I. use may reduce the absorption of important nutrients, vitamins and minerals, including magnesium, calcium and vitamin B12, and might reduce the effectiveness of other medications, with the F.D.A. warning that taking Prilosec together with the anticlotting agent clopidogrel (Plavix) can weaken the protective effect (of clopidogrel) for heart patients.

Other research has found that people taking P.P.I.'s are at increased risk of developing pneumonia; one study even linked use of the drug to weight gain.

Drug company officials dismiss such reports, saying that they do not prove the P.P.I.'s are the cause of the problems and that many P.P.I. users are older adults who are susceptible to infections and more likely to sustain fractures and have nutritional deficits.

But while using the drugs for short periods may not be problematic, they tend to breed dependency, experts say, leading patients to take them for far longer than the recommended 8 to 12 weeks; some stay on them for life. Many hospitals have been starting patients on P.P.I.'s as a matter of routine, to prevent stress ulcers, then discharging them with instructions to continue the medication at home. Dr. Charlie Baum, head of U.S. Medical Affairs for Takeda Pharmaceuticals North America Inc., said its P.P.I. Dexilant is safe when used according to the prescribed indication of up to six months for maintenance, though many physicians prescribe it for longer.

"Studies have shown that once you're on them, it's hard to stop taking them," said Dr. Shoshana J. Herzig of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston. "It's almost like an addiction."

P.P.I.'s work by blocking the production of acid in the stomach, but the body reacts by overcompensating and, she said, "revving up production" of acid-making cells. "You get excess growth of those cells in the stomach, so when you unblock production, you have more of the acid-making machinery," she said.

Moreover, proton pump inhibitors have not been the wonder drugs that experts had hoped for. More widespread treatment of GERD has not reduced the incidence of esophageal cancers. Squamous cell carcinoma, which is associated with smoking, has declined, but esophageal adenocarcinomas, which are associated with GERD, have increased 350 percent since 1970.

"When people take P.P.I.'s, they haven't cured the problem of reflux," said Dr. Joseph Stubbs, an internist in Albany, Ga., and a former president of the American College of Physicians. "They've just controlled the symptoms."

And P.P.I.'s provide a way for people to avoid making difficult lifestyle changes, like losing weight or cutting out the foods that cause heartburn, he said. "People have found, 'I can keep eating what I want to eat, and take this and I'm doing fine,' " he said. "We're starting to see that if you do that, you can run into some risky side effects."

Many patients may be on the drugs for no good medical reason, at huge cost to the health care system, said Dr. Joel J. Heidelbaugh, a family medicine doctor in Ann Arbor, Mich. When he reviewed medical records of almost 1,000 patients on P.P.I.'s at an outpatient Veterans Affairs clinic in Ann Arbor, he found that only one-third had a diagnosis that justified the drugs. The others seemed to have been given the medications "just in case."

"We put people on P.P.I.'s, and we ignore the fact that we were designed to have acid in our stomach," said Dr. Greg Plotnikoff, a physician who specializes in integrative therapy at the Penny George Institute for Health and Healing in Minneapolis.

Stomach acid is needed to break down food and absorb nutrients, he said, as well as for proper functioning of the gallbladder and pancreas. Long-term of use of P.P.I.'s may interfere with these processes, he noted. And suppression of stomach acid, which kills bacteria and other microbes, may make people more susceptible to infections, like C. difficile.

Taking P.P.I.'s, Dr. Plotnikoff said, "changes the ecology of the gut and actually allows overgrowth of some things that normally would be kept under control."

Stomach acid also stimulates coughing, which helps clear the lungs. Some experts think this is why some patients, especially those who are frail and elderly, face an increased risk of pneumonia if they take P.P.I.'s.

But many leading gastroenterologists are convinced that the benefits of the drugs outweigh their risks. They say the drugs prevent serious complications of GERD, like esophageal and stomach ulcers and peptic strictures, which occur when inflammations causes the lower end of the esophagus to narrow.

The studies that detected higher risks among patients on P.P.I.'s "are statistical analyses of very large patient populations. But how does that relate to you, as one person taking the drug?" said Dr. Donald O. Castell, director of esophageal disorders at the Medical University of South Carolina and an author of the American College of Gastroenterology's practice guidelines for GERD, who has financial relationships with drug companies that make P.P.I.'s. He added, "You don't want to throw the baby out with the bathwater."

Most physicians think that GERD is a side effect of the obesity epidemic, and that lifestyle changes could ameliorate heartburn for many.

"If we took 100 people with reflux and got them to rigidly follow the lifestyle recommendations, 90 wouldn't need any medication," Dr. Castell said. "But good luck getting them to do that."

Emerging Type of Heartburn Defies Drugs, Diagnosis

Melinda Beck : WSJ : November 12, 2012

New research suggests that in many people, heartburn may be caused by something other than acid reflux. But gastroenterologists are often stumped as to what it is and how to treat it.

Some 44% of Americans have heartburn at least once a month, and 7% have it daily, according to the International Foundation for Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders. Heartburn that frequent is the most common symptom of gastroesophageal reflux disease, a diagnosis believed to be rising world-wide with obesity and advancing age. One 2004 study cited a 46% increase in GERD-related visits to primary-care physicians over a three-year period alone.

But up to one-half of GERD patients don't get complete relief from even the strongest acid-reducing medications, called proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs), and most don't have any evidence of acid erosion when doctors examine their esophagus with an endoscope. Gastroenterologists have dubbed this condition non-erosive reflux diseases, or NERD.

It has become a hot topic for discussion and research. "It used to be thought that all GERD was the same—you give patients PPIs and they'll all respond," says Prateek Sharma, a gastroenterologist at the University of Kansas School of Medicine. "But we're finding that a subset of these patients don't have acid as a cause of their symptoms."

Gastrointestinal experts now estimate that 50% to 70% of GERD patients actually have NERD, and studies show they are more likely to be female—and younger and thinner—than typical acid-reflux sufferers. They are also about 20% to 30% less likely to get relief from acid-blocking drugs. But their episodes of heartburn are just as frequent, just as severe and just as disruptive of their quality of life, studies show.

Doctors suspect some may be suffering from a reflux of bile, a digestive liquid produced in the liver, rather than stomach acid, or from hypersensitivity to sensations in the esophagus.

Another guess is psychological stress. A 2004 study of 60 patients conducted at the University of California, Los Angeles, found that those with severe, sustained stress in the previous six months were more likely to have heartburn symptoms during the next four months.

"It's probably a bunch of different conditions put together in one basket," says Loren Laine, a professor of medicine at Yale University School of Medicine and president of the American Gastroenterological Association. "The ones we worry about are the ones who don't respond to standard therapy," he says. "Then we have to figure out why they don't respond."

Most people with heartburn take over-the-counter antacids, H2 receptor blockers or PPIs, often on the advice of pharmacists or primary-care physicians. Many H2 blockers and PPIs are available in stronger prescription form as well. More than 113 million prescriptions are filled for PPIs each year, at a cost of $14 billion, making it the third largest-selling drug category in the world.

Patients are typically referred to gastroenterologists only if their heartburn persists, or if they experience so-called alarm symptoms, such as nausea, vomiting blood or extreme discomfort. Gastroenterologists generally only do an endoscopy when the patient doesn't respond to taking a PPI twice a day for 12 weeks.

Doctors seldom see evidence of acid erosion when they use an endoscope—a long tube with a lighted camera that lets them examine the esophagus—but there is debate over what that means. Some patients' heartburn may be caused by micro-erosions only visible with special equipment. Some may have symptoms that haven't produced damage yet, and in some cases, the damage in the esophagus may have been healed by the acid-blocking medication, but still, the heartburn pain persists.

"The patient doesn't care if they have esophageal erosion of not. They are more concerned about the pain," says Dr. Sharma.

To investigate whether acid reflux is involved at all, doctors can do a 24-hour pH test, inserting an acid-sensitive probe through the patient's nose into the esophagus, where it records any episodes of reflux. If acid secretions are normal, or if they don't correlate with the patient's symptoms, it is a strong clue that the heartburn has another cause.

A newer version currently attracting physician interest, called impedance testing, can detect nonacid reflux, including bile.

If reflux is normal and doesn't correlate with patient's symptoms, doctors typically diagnose "functional heartburn," which means they have ruled out known explanations. "That's what you call it when you don't know what else to call it," says David Clarke, a gastroenterologist in Portland, Ore.

By some estimates, functional heartburn accounts for up to 50% of NERD patients. One theory is that sufferers have a hypersensitive esophagus, in which nerve endings interpret even normal digestive sensations as painful, similar to fibromyalgia. Acid-suppressing medication doesn't help, but low-dose tricyclic antidepressants seem to modulate the pain in some patients.

Studies also show that patients diagnosed with functional heartburn exhibit a high percentage of psychological stress. Dr. Clarke says he found that about one-third of his patients with heartburn didn't get better on proton-pump inhibitors, or have evidence of acid reflux, but in virtually every case, they had severe stress in their lives. Once the stress was recognized and resolved, their GI symptoms improved.

"Many people with those conditions aren't as aware of them as you would think," says Dr. Clarke, who is president of the Psychophysiologic Disorders Association, a nonprofit advocacy group for stress-induced medical conditions. And many GI specialists don't have the time or training to help patients understand how stress might cause their symptoms, he says.

There is surprisingly little research on whether certain foods may cause heartburn. "Why not try diet first instead of drugs?" asks Jan Patenaude, director of medical nutrition at Oxford Biomedical Technologies, Inc. The South Florida lab company tests patients' blood to see if it forms an inflammatory reaction to any of hundreds of foods. Patients then stop eating any suspect food, then gradually add them back to see if their heartburn returns.

Mainstream gastroenterologists say there is little evidence that an inflammatory reaction causes heartburn. Then again, doctors have long counseled patients to avoid common "trigger" foods such as chocolate, peppermint, peppers, alcohol and caffeine. "A lot of standard advice that we give hasn't been proven," says Dr. Sharma.

Other standard recommendations are to quit smoking, not lie down within three hours of eating, get sufficient sleep, avoid tight clothes (particularly those that constrict the waist) and lose weight. A recent study in the Journal of Obesity found that when patients who were overweight or obese lost weight, they had a reduction in symptoms.

Many doctors tell patients with NERD or functional heartburn to continue taking proton-pump inhibitors, despite studies showing they are less effective in such cases. The Food and Drug Administration has issued warnings that long-term use and high doses can increase the risk of bone fractures and bacterial infections—and may reduce the absorption of key nutrients, including magnesium, calcium and vitamin B12.

A Glossary for Your Gut

- Heartburn: A burning pain behind the sternum, or breast bone, that may radiate up into the throat.

- Acid reflux: Occurs when acid secretions in the stomach splash up into the esophagus (food pipe), a frequent cause of heartburn.

- GERD (Gastroesophageal reflux disease): Digestive distress caused by acid reflux, usually diagnosed when heartburn occurs at least weekly.

- NERD (Non-erosive reflux disease): Chronic heartburn with no evidence of acid damage in the esophagus.

- Functional heartburn: A catch-all term for heartburn with no apparent cause.

- Antacids: Over-the-counter medications that neutralize excess stomach acid, e.g Rolaids, Tums, Pepto-Bismol.

- H2 blockers*: Drugs that reduce stomach acid by blocking histamines that produce it, e.g. Pepcid, Tagamet, Zantac.

- Proton-pump inhibitors* (PPIs): The most potent drugs that block the stomach's production of acid, e.g. Nexium, Prevacid, Prilosec, Aciphex. Can take up to several months to work.

Dietary Triggers

Not surprisingly, what you eat can come back to haunt you, heartburn-wise.

Common dietary triggers include:

- Tomatoes

- Citrus

- Peppers

- Caffeine

- Alcohol

- Chocolate

- Peppermint