- RETIREMENT ANNOUNCEMENT

- HOME PAGE

- "MYCHART" the new patient portal

- BELMONT MEDICAL ASSOCIATES

- MOUNT AUBURN HOSPITAL

- EMERGENCIES

- PRACTICE PHILOSOPHY

- MY RESUME

- TELEMEDICINE CONSULTATION

- CONTACT ME

- LAB RESULTS

- ePRESCRIPTIONS

- eREFERRALS

- RECORD RELEASE

- MEDICAL SCRIBE

- PHYSICIAN ASSISTANT (PA)

- Medicare Annual Wellness Visit

- Case management/Social work

- Quality Care Measures

- Emergency closing notice

- FEEDBACK

- Talking to your doctor

- Choosing..... and losing a doctor

- INDEX A - Z

- ALLERGIC REACTIONS

- Alternative Medicine

- Alzheimer's Disease

- Bladder Problems

- Blood disorders

- Cancer Concerns

- GENETIC TESTING FOR HEREDITARY CANCER

- Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

- Controversial Concerns

- CPR : Learn and save a life

- CRP : Inflammatory marker

- Diabetes Management

- Dizziness, Vertigo,Tinnitus and Hearing Loss

- EXERCISE

- FEMALE HEALTH

-

GASTROINTESTINAL topics

- Appendicitis

- BRAT diet

- Celiac Disease or Sprue

- Crohn's Disease

- Gastroenterologists for Colon Cancer Screening

- Colonoscopy PREP

- Constipation

- Gluten sensitivity, but not celiac disease

- Heartburn and GERD

- Hemorrhoids and Anal fissure

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- NASH : Non Alcoholic Steato Hepatitis

- FEET PROBLEMS

- HEART RELATED topics

-

INFECTIOUS DISEASES

- Antibiotic Resistance

- Cat bites >

- Clostridia difficile infection - the "antibiotic associated germ"

- CORONA VIRUS

- Dengue Fever and Chikungunya Fever

- Food borne illnesses

- Shingles Vaccine

- Hepatitis B

- Hepatitis C

- Herpes

- Influenza

- Helicobacter pylori - the "ulcer germ"

- HIV Screening

- Lyme and other tick borne diseases

- Measles

- Meningitis

- MRSA (Staph infection)

- Norovirus

- Sexually Transmitted Diseases

- Shingles (Herpes Zoster)

- Sinusitis

- West Nile Virus

- Whooping Cough (Pertussis)

- Zika virus and pregnancy

- INSURANCE related topics

- KIDNEY STONES

- LEG CRAMPS

- LIBRARY for patients

- LIFE DECISIONS

- MALE HEALTH

- Medication/Drug side effects

- MEDICAL MARIJUANA

- MENTAL HEALTH

- Miscellaneous Articles

-

NUTRITION - EXERCISE - WEIGHT

- Cholesterol : New guidelines for treatment

- Advice to lower your cholesterol

- Cholesterol : Control

- Cholesterol : Raising your HDL Level

- Exercise

- Food : Making Smart Choices

- Food : Making Poor Choices

- Food : Grape Fruit and Drug Interaction

- Food : Vitamins, Minerals and Supplements

- Omega 3 fatty acids

- Vitamin B12 deficiency

- Vitamin D

- Weight Loss

- ORTHOPEDICS

- PAIN

- PATIENTS' RIGHTS

- SKIN

- SLEEP

- SMOKING

- STROKE

- THYROID

- SUBSTANCE ABUSE

- Travel and Vaccination

- TREMOR

- Warfarin Anticoagulation

- OTHER STUFF FOLLOWS

- Fact or Opinion?

- Hippocratic Oath

- FREE ADVICE.......for what its worth!

- LAUGHTER.....is the best medicine

- Physicians Pet Peeves

- PHOTO ALBUM - its not all work!

- Cape Town, South Africa

- Tribute page

- The 100 Club

- Free Wi-Fi

Tremor

Finding Some Calm After Living With ‘the Shakes’

By Jane E. Brody : NY Times Article : May 29, 2007

As Sandy Kamen Wisniewski remembers, her hands always shook. She hid them in long sleeves and pockets and wrote only in block letters in school because at least that was readable. The tremor became much worse as she entered her teenage years, and if she was upset or under stress, it grew so bad she cringed with embarrassment and decided that it must all be psychological.

Ms. Wisniewski, now 40, was 14 when she learned that she had not an emotional disorder, but a neurological condition called essential tremor — “essential” not because she needed it, but because no underlying factor caused it. It was not a prelude to Parkinson’s disease, nor was it caused by a hormonal problem, a drug reaction or nervousness.

(Many people thought that Katharine Hepburn had Parkinson’s disease, when in fact she shook because she had essential tremor, as does Terry Link, a state senator in Illinois, and Gov. Jim Gibbons of Nevada.)

This disorder, which in most cases is inherited, is so misunderstood and so often misdiagnosed that Ms. Wisniewski, who lives in Libertyville, Ill., decided to write a book about it. Called “I Can’t Stop Shaking,” the book was self-published last year through Dog Ear Publishing in Indianapolis. Her intent is to help the estimated 10 million people who suffer with essential tremor, often for decades without knowing what is wrong.

John, for example, whose head shook uncontrollably, spent 27 years “being tested for nearly everything,” as he relates in the book. He even had an M.R.I. and was told by the doctor that there was nothing wrong with him.

Modern technology helped him learn the truth when he typed “head tremors” into a computer search engine and found the Web site for the International Essential Tremor Foundation. His shouts of joy upon recognizing his disorder woke his wife. He then recalled that his grandmother and all his cousins had what they called “the shakes,” also without knowing why.

Only a small minority of patients with essential tremor seek treatment, Ms. Wisniewski’s book says, although there are several medications that help and, for intractable cases, a surgical procedure that can greatly reduce, if not eliminate, the tremors.

For Shari Finsilver, who never even told her parents about the hand tremors that began at age 11, the surgery she underwent in her 50s, called deep brain stimulation, was “a life-altering experience, like someone awakened from a lifetime coma.”

As she wrote in Ms. Wisniewski’s book, “I immediately began doing all the things I had not been able to do for 40 years: write by hand, use a camera, cut with scissors, make change at the cash register, sign checks and credit card receipts, enroll in a public speaking course, dance with men other than my husband and son — all the things most people take for granted.

“But best of all, I was able to walk down the aisle at my children’s weddings, and cradle my grandchildren in my arms with steady hands.”

One thorough study has indicated that in 96 percent of cases, essential tremor is familial, a result of an autosomal dominant genetic mutation. That means that every child of a person with the condition has a 50 percent chance of inheriting it. And most people, after learning the nature of their problem, are able to trace it from a parent and other family members. But the so-called penetrance of the mutated gene can vary widely, resulting in different degrees of disability.

The damaged gene interferes with voluntary muscles and can affect any body part, hands most often, but also the neck, larynx (resulting in a tremulous voice) and, less often, the legs. The tremor disappears at rest and during sleep, but becomes apparent when a person tries to do something with the affected part and is made worse by stress, fatigue, caffeine and anxiety.

In people with hand tremors, the shaking starts when they try to write or hold a cup of coffee or eat with a utensil. Many people with essential tremor devise ways to avoid such activities, like eating just sandwiches or never eating in public, typing instead of writing or paying by credit card to avoid writing a check.

One woman in Ms. Wisniewski’s book was able to return to college when she learned that disability laws entitled her to a note taker for all her classes. But many employment opportunities are out of reach. Jean Moore worked in a payroll office until she could no longer read her own numbers. Another woman was fired from her job as a waitress when she could no longer carry cups of liquid and plates of food without spilling them.

Head tremor is more difficult to disguise. Some people sit with their elbows planted on a firm surface, holding their head in their hands.

While the disorder can show itself at any age, essential tremor usually does not become apparent until midlife and then worsens with age.

In diagnosing essential tremor, a doctor must first rule out other causes like medications, drug or alcohol withdrawal, excessive caffeine intake, overactive thyroid, heavy metal poisoning, fever and anxiety. A doctor also must check for other neurological conditions like Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis or dystonia.

A number of drugs have been found, mostly by accident, to relieve tremors. They include beta blockers like propranolol, marketed as Inderal, used mainly to control high blood pressure; primidone, found in Mysoline; and topiramate, or Topamax, used mainly to treat epilepsy.

Several other drugs have helped some patients, and sometimes a combination of medications proves helpful. Dosages are limited by the patient’s ability to tolerate side effects. Injections of botulinum toxin A, in Botox, help many people with head tremors.

If drug treatment is not helpful, implanting a stimulator in the thalamus of the brain can block the nerve signals that cause tremors in the upper extremities. The procedure has its hazards and is usually a last resort.

Most people with essential tremor have discovered on their own that alcohol provides temporary relief. But over time, more and more alcohol is needed to be helpful, so excessive intake and alcoholism are real dangers. This remedy is best used sporadically.

Members of the essential tremor foundation have provided a host of “survival” tips that Ms. Wisniewski lists in her book. They include these ideas:

Shedding Light on a Tremor Disorder

By Jane E. Brady : NY Times Article : December 8, 2009

Essential” usually means vital, necessary, indispensable. But in medicine, the word can assume a different cast, meaning inherent or intrinsic, not symptomatic of anything else, lacking a known cause.

Since the mid-19th century, “essential tremor” has been the diagnosis for a disorder of uncontrollable shaking — usually of the hands but sometimes of the head and other body parts, or the voice — that is not due to some other condition. And without knowing what causes it, doctors have been slow to come up with treatments to subdue it.

As a result, millions of individuals suffer to varying degrees with embarrassment and humiliation, social isolation and difficulties holding down a job or performing the tasks of daily life. When you cannot drink a glass of water or eat soup without spilling it because your hand shakes violently, you are unlikely to join others for a dinner out. When you have to depend on someone else to button your shirt or zip your jacket, you may not go out at all.

Wherever those with essential tremor go, people are likely to stare at them and assume they have a drug or alcohol problem, said Catherine Rice, executive director of the International Essential Tremor Foundation in Lenexa, Kan. (Call it at 888-387-3667 or visit its Web site: www.essentialtremor.org.)

Now, thanks to the devoted efforts of a few researchers here and abroad, all this may change. Recent studies have begun to unravel the mysteries of essential tremor, and “essential” may someday be dropped from its name.

“Until very recently,” Dr. Elan D. Louis, a pioneering neurologist and epidemiologist at the College of Physicians and Surgeons at Columbia University, told me, “essential tremor was thought to have no known pathology, no changes in the brain, which led to a medical dead end.” But in the last five years, Dr. Louis said, discoveries in three areas — the brain, clinical findings and genetics and environment — “have changed our understanding of this disease.”

And as our understanding evolves, he predicts that rational therapies will follow.

Common Over Age 65

Essential tremor is a neurological disorder that causes uncontrollable shaking of one or more body parts during voluntary movement. The symptoms disappear at rest. In that way it differs from Parkinson’s disease, in which shaking at rest is a common symptom that disappears during movement. But those with essential tremor are four to five times as likely to develop Parkinson’s as people without tremor, and both conditions involve related changes in the brain.

Though essential tremor most often affects older people — as many as 1 in 5 over 65 have it — it can occur at any age, even in young children. It is typically progressive, getting worse as people age.

Stephen Remillard of Steamboat Springs, Colo., said he learned he had essential tremor while in kindergarten, when it affected just his hands. But the condition worsened as he got older, and by high school, Mr. Remillard said, “all my extremities as well as my voice were affected.” When he had to speak in class, he said, “it came off as if I was nervous, though I’ve always been a very confident person.”

The academic challenges related to tremor prompted him to drop out of college. But the biggest blow to Mr. Remillard’s self-esteem came when he tried to join the military and was rejected by the Army, Marines, Air Force and Coast Guard. Rather than feel sorry for himself, he returned to college, graduating last May, and started playing sports. Now 25, he works for a ski corporation and runs marathons to raise money for causes like the Lance Armstrong Foundation.

For Richard Crandell, a 66-year-old guitarist from Eugene, Ore., the problem began around age 60, forcing him to abandon his instrument. But he, too, was not to be defeated: he took up the mbira, an African thumb piano that he plays with two thumbs and an index finger.

Still, Mr. Crandell said, he has problems shaving, brushing his teeth, using a computer and slicing and dicing in the kitchen. And at the bank, he has to ask the teller to fill in his forms “because my handwriting is all over the place.”

Ms. Rice said essential tremor ran in her family. “My great-aunts used to shake uncontrollably, starting in their early 40s and becoming quite severe by the time they were 60,” she said. “They found it very difficult to cook, though their job was to feed the farmhands. They couldn’t pick up a heavy pan without spilling the contents. They had to give up crocheting and other things they truly loved.”

New Findings

Dr. Louis and colleagues have established a centralized brain repository that has revealed underlying abnormalities in essential tremor patients. The scientists collect detailed clinical and physiological data on each person, and after death their brains are shipped to Columbia, where they are analyzed and compared with the brains of normal individuals.

Of the 50 brains studied so far, Dr. Louis said, “all are degenerative and have very clear pathological changes, although there are several types, suggesting this is probably a family of diseases.” In one subtype, Lewy bodies, which also occur in Parkinson’s disease, are found in the brain but in a different area from Parkinson’s. (Mr. Crandell’s father died of Parkinson’s, and there have been suggestions that the disorders may be linked.)

In about 80 percent of the brains, there are degenerative changes in the cerebellum, including a loss of cells that produce a major inhibitory neurotransmitter called GABA. Other abnormal findings include a messy arrangement of neurofilaments, which may interfere with nerve cell transmission.

Clinically, essential tremor is now considered a neuropsychiatric disease that can include unsteadiness, abnormal eye movements, problems with coordination and cognitive changes that sometimes progress to dementia.

Even certain personality types tend to be overrepresented among patients with essential tremor, Dr. Louis said. Many “are very detail-oriented and tightly wound and have higher harm-avoidance scores,” he said.

Two environmental toxins have been found to be elevated in tremor patients: lead and a dietary chemical called harmane that occurs naturally in plants and animals. When meat is cooked for long periods or at high temperatures, as in barbecuing, levels of harmane rise sharply. Dr. Louis called these “tantalizing leads.”

Despite the problems caused by their disorder, most patients with essential tremor never seek treatment. Two drugs, propranolol (Inderal) and primidone (Mysoline), developed to treat other conditions, have proved helpful for many but not all patients. A costly surgical treatment, deep brain stimulation, has helped to reduce tremors in about 80 percent of patients who have tried it.

Caffeine, certain prescription drugs and undue stress can make symptoms worse and are best avoided. Though alcohol can temporarily relieve tremors, regular heavy drinking is a recognized cause of the disorder .

.

Parkinson's Disease

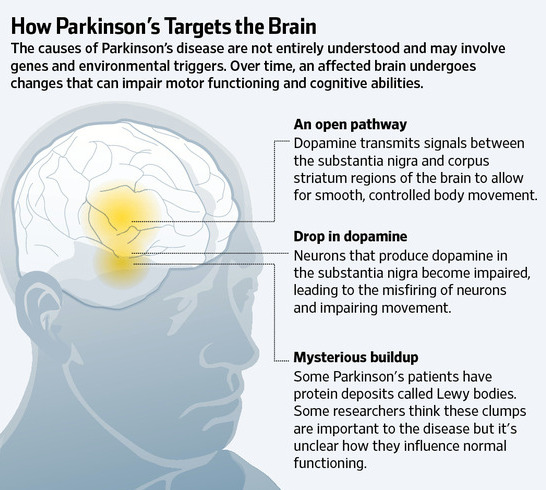

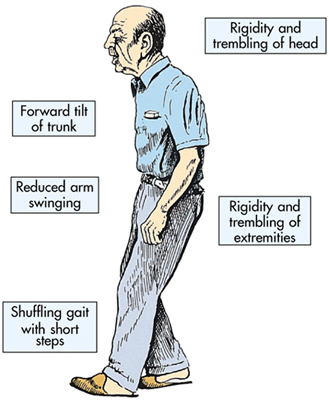

Parkinson's disease is a disorder of the brain that leads to shaking (tremors) and difficulty with walking, movement, and coordination.

Alternative Names

Paralysis agitans; Shaking palsy

Causes

Parkinson's disease was first described in England in 1817 by Dr. James Parkinson. The disease affects approximately 2 of every 1,000 people and most often develops after age 50. It is one of the most common neurologic disorders of the elderly. Sometimes Parkinson's disease occurs in younger adults, but is rarely seen in children. It affects both men and women.

In some cases, Parkinson's disease occurs within families, especially when it affects young people. Most of the cases that occur at an older age have no known cause.

Parkinson's disease occurs when the nerve cells in the part of the brain that controls muscle movement are gradually destroyed. The damage gets worse with time. The exact reason that the cells of the brain waste away is unknown. The disorder may affect one or both sides of the body, with varying degrees of loss of function.

Nerve cells use a brain chemical called dopamine to help send signals back and forth. Damage in the area of the brain that controls muscle movement causes a decrease in dopamine production. Too little dopamine disturbs the balance between nerve-signalling substances (transmitters). Without dopamine, the nerve cells cannot properly send messages. This results in the loss of muscle function.

Some people with Parkinson's disease become severely depressed. This may be due to loss of dopamine in certain brain areas involved with pleasure and mood. Lack of dopamine can also affect motivation and the ability to make voluntary movements.

Early loss of mental capacities is uncommon. However, persons with severe Parkinson's may have overall mental deterioration (including dementia and hallucinations). Dementia can also be a side effect of some of the medications used to treat the disorder.

Parkinson's in children appears to occur when nerves are not as sensitive to dopamine, rather than damage to the area of brain that produces dopamine. Parkinson's in children is rare.

The term "parkinsonism" refers to any condition that involves a combination of the types of changes in movement seen in Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism may be caused by other disorders (such as secondary parkinsonism) or certain medications used to treat schizophrenia.

Symptoms »

Additional symptoms that may be associated with this disease:

The health care provider may be able to diagnose Parkinson's disease based on your symptoms and physical examination. However, the symptoms may be difficult to assess, particularly in the elderly. For example, the tremor may not appear when the person is sitting quietly with arms in the lap. The posture changes may be similar to osteoporosis or other changes associated with aging. Lack of facial expression may be a sign of depression.

An examination may show jerky, stiff movements, tremors of the Parkinson's type, and difficulty starting or completing voluntary movements. Reflexes are essentially normal.

Tests may be needed to rule out other disorders that cause similar symptoms.

See also: Essential tremor

In-Depth Diagnosis »

There is no known cure for Parkinson's disease. The goal of treatment is to control symptoms.

Medications control symptoms primarily by increasing the levels of dopamine in the brain. The specific type of medication, the dose, the amount of time between doses, or the combination of medications taken may need to be changed from time to time as symptoms change. Many medications can cause severe side effects, so monitoring and follow-up by the health care provider is important.

Types of medication:

Good general nutrition and health are important. Exercise should continue, with the level of activity adjusted to meet the changing energy levels that may occur. Regular rest periods and avoidance of stress are recommended, because fatigue or stress can make symptoms worse. Physical therapy, speech therapy, and occupational therapy may help promote function and independence.

Railings or banisters placed in commonly used areas of the house may be of great benefit to the person experiencing difficulties with daily living activities. Special eating utensils may also be helpful.

Social workers or other counseling services may help the patient cope with the disorder and with obtaining assistance (such as Meals-on-Wheels) as appropriate.

Experimental or less common treatments may be recommended. For example, surgery to implant stimulators or destroy tremor-causing tissues may reduce symptoms in some people. Transplantation of adrenal gland tissue to the brain has been attempted, with variable results.

In-Depth Treatment »

Support Groups

Support groups may help a person cope with the changes caused by the disease.

See: Parkinson's disease - support group

Expectations (prognosis)

Untreated, the disorder progresses to total disability, often accompanied by general deterioration of all brain functions, and may lead to an early death.

Treated, the disorder impairs people in varying ways. Most people respond to some extent to medications. The extent of symptom relief, and how long this control of symptoms lasts, is highly variable. The side effects of medications may be severe.

Calling Your Health Care Provider

Call your health care provider if symptoms of Parkinson's disease appear, if symptoms get worse, or if new symptoms occur. Also tell the health care provider about any possible side effects of medications, which may include:

The Emotional Toll of Parkinson's Disease

By Marilynn Larkin

Dr. Irene Richard, a movement disorder neurologist and researcher at the University of Rochester, is an investigating senior medical adviser to The Michael J. Fox Foundation, an organization committed to improving the lives of people with Parkinson’s disease. Dr. Richard is an expert on the mental and emotional aspects of the illness and is leading a national study looking into whether medications might help treat depression related to Parkinson’s disease.

Q. You investigate the links between mood disorders and Parkinson’s disease. Isn’t it normal to be depressed after a diagnosis of Parkinson’s?

A. Feeling sad after a diagnosis is understandable. But that’s not the same as depression, which is actually a syndrome with many facets. Up to 40 percent of people with Parkinson’s disease develop this syndrome and experience symptoms that may include depressed mood; decreased interest in people and activities; and problems with sleep, appetite and sex. In contrast to sadness, which usually dissipates as people come to accept their diagnosis, depression may continue for weeks or even years. And there’s increasing evidence that although the symptoms are similar, depression related to Parkinson’s disease may be different from regular depression.

Q. How is depression in Parkinson’s disease different?

A. Research has shown us that in some cases, depression may be the first sign of Parkinson’s disease, appearing well before any motor symptoms, and so we think it may be part of the underlying disease process. But not everyone who has Parkinson’s gets depressed, so there’s probably something going on that makes certain people vulnerable and others not — and this vulnerability doesn’t seem to be related to the severity of the disease or how disabled the person is. So a person with mild Parkinson’s symptoms might become severely depressed, whereas someone with worse symptoms doesn’t.

That said, it can be difficult to diagnose depression in Parkinson’s because other symptoms may mask the depression. For example, people with Parkinson’s tend to move slowly and speak softly, without a lot of inflection. These are also signs of major depression. But when individuals with Parkinson’s behave that way, most people don’t think depression — they just chalk it up to the disease. But if the depression can be appropriately treated, the person’s quality of life will improve, as may some of the symptoms.

So the bottom line is at this point is we don’t know if depression is fundamentally different in Parkinson’s or just looks different because of the company it keeps. But either way, it should be treated.

Q. Can doctors just prescribe antidepressants?

A. It’s not that simple. We can’t just transfer information we know based on the brains of people without Parkinson’s and assume that these drugs will work the same way in people who do. We’ve actually embarked on the first large, multi-center, placebo-controlled clinical trial to see whether antidepressants work and can be tolerated by people with Parkinson’s. Nobody has tried to test this until now.

We’ll also try to see whether antidepressants might affect Parkinson’s motor symptoms. We know that certain types of antidepressants can actually induce Parkinson’s-type symptoms in some people who don’t have the disease. And there’s some evidence that selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and medications with anticholinergic properties, such as tricyclic antidepressants and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, may actually help symptoms of Parkinson’s.

But patients with Parkinson’s generally are on a number of other medications, so we don’t know how well the side effects would be tolerated. For example, a person who doesn’t have Parkinson’s disease might not get dizzy or sedated, but someone with Parkinson’s might. We’ll be trying to answer these questions in our study, which is funded by the National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Stroke and compares venlafaxine (Effexor) or paroxetine (Paxil) to placebo.

Q. What stage has the study reached?

A. Recruitment has been difficult, in part because, as is the case for many mood disorders, doctors don’t recognize when their patients are depressed. And if they do recognize it, there’s a stigma attached to having a “mental” disorder, so people don’t want to admit it. And even if they recognize and admit it, many of the people we want to enroll are tired and apathetic because of their disease, so they don’t want to join clinical trials. So we really have a lot of strikes against us.

On the positive side, anyone who enrolls will get in-depth attention from movement disorder specialists, and they’ll also be contributing to knowledge that will help others.

Q. Are other mental or emotional symptoms common in Parkinson’s?

A. We’ve known for a while that some anti-Parkinson’s medications can trigger hallucinations or delusions in some patients. But more recently, we’ve realized that because Parkinson’s affects multiple domains of brain function, you can get mood fluctuations similar to motor fluctuations, where your brain no longer responds to medication by producing dopamine in a steady state. Instead, you have peaks and valleys that can lead to too much motor activity (“on”) or, at the other extreme, rigidity (“off”).

With mood fluctuations, an individual can transition from being sad and suicidal to euphoric within minutes. The change is very dramatic and disconcerting to the person and the people around him or her.

Not everyone experiences these rapid mood swings, but in those who do, they tend to correlate, time-wise, with motor fluctuations. This means someone may be depressed when “off” and normal mood or euphoric when “on.” But having said that, my group has done some research looking at diaries in which patients documented their motor state and their mood hourly for seven days. We found wide variations in mood and motor fluctuations, even for the same individual, over the course of a week. And although the two types of fluctuations correlated in the majority of patients, there was a subset in which they did not.

So it appears there are two independent fluctuations going on in the brain, one for mood and one for motor. This can be very upsetting; it’s like bipolar disorder on a daily basis — you just go from one extreme to another. So we and others are looking into the mechanisms behind these fluctuations, and hopefully at some point, we’ll have a treatment.

Q. What is the most challenging part of your work?

A. Getting people to pay attention to the emotional aspects of the disease. In my work with patients, I’ve been really struck by the way they struggle not only with motor symptoms, but also from emotional symptoms. This has really motivated me to work on these conditions and help raise awareness.

Q. Is awareness of the emotional aspects of Parkinson’s disease increasing?

A. I have to say it’s finally starting to happen. Society’s awareness about mental illness over all is being raised and, hopefully, there will be less stigma attached to it. And in the setting of Parkinson’s disease, these conditions are now on the radar screen. The Michael J. Fox Foundation has asked researchers to apply for grants looking at psychiatric outcomes in Parkinson’s, which is great. We’re also trying to interest researchers involved in emotional and mental disorders in other neurological diseases, like Alzheimer’s, to also focus on Parkinson’s.

By Jane E. Brody : NY Times Article : May 29, 2007

As Sandy Kamen Wisniewski remembers, her hands always shook. She hid them in long sleeves and pockets and wrote only in block letters in school because at least that was readable. The tremor became much worse as she entered her teenage years, and if she was upset or under stress, it grew so bad she cringed with embarrassment and decided that it must all be psychological.

Ms. Wisniewski, now 40, was 14 when she learned that she had not an emotional disorder, but a neurological condition called essential tremor — “essential” not because she needed it, but because no underlying factor caused it. It was not a prelude to Parkinson’s disease, nor was it caused by a hormonal problem, a drug reaction or nervousness.

(Many people thought that Katharine Hepburn had Parkinson’s disease, when in fact she shook because she had essential tremor, as does Terry Link, a state senator in Illinois, and Gov. Jim Gibbons of Nevada.)

This disorder, which in most cases is inherited, is so misunderstood and so often misdiagnosed that Ms. Wisniewski, who lives in Libertyville, Ill., decided to write a book about it. Called “I Can’t Stop Shaking,” the book was self-published last year through Dog Ear Publishing in Indianapolis. Her intent is to help the estimated 10 million people who suffer with essential tremor, often for decades without knowing what is wrong.

John, for example, whose head shook uncontrollably, spent 27 years “being tested for nearly everything,” as he relates in the book. He even had an M.R.I. and was told by the doctor that there was nothing wrong with him.

Modern technology helped him learn the truth when he typed “head tremors” into a computer search engine and found the Web site for the International Essential Tremor Foundation. His shouts of joy upon recognizing his disorder woke his wife. He then recalled that his grandmother and all his cousins had what they called “the shakes,” also without knowing why.

Only a small minority of patients with essential tremor seek treatment, Ms. Wisniewski’s book says, although there are several medications that help and, for intractable cases, a surgical procedure that can greatly reduce, if not eliminate, the tremors.

For Shari Finsilver, who never even told her parents about the hand tremors that began at age 11, the surgery she underwent in her 50s, called deep brain stimulation, was “a life-altering experience, like someone awakened from a lifetime coma.”

As she wrote in Ms. Wisniewski’s book, “I immediately began doing all the things I had not been able to do for 40 years: write by hand, use a camera, cut with scissors, make change at the cash register, sign checks and credit card receipts, enroll in a public speaking course, dance with men other than my husband and son — all the things most people take for granted.

“But best of all, I was able to walk down the aisle at my children’s weddings, and cradle my grandchildren in my arms with steady hands.”

One thorough study has indicated that in 96 percent of cases, essential tremor is familial, a result of an autosomal dominant genetic mutation. That means that every child of a person with the condition has a 50 percent chance of inheriting it. And most people, after learning the nature of their problem, are able to trace it from a parent and other family members. But the so-called penetrance of the mutated gene can vary widely, resulting in different degrees of disability.

The damaged gene interferes with voluntary muscles and can affect any body part, hands most often, but also the neck, larynx (resulting in a tremulous voice) and, less often, the legs. The tremor disappears at rest and during sleep, but becomes apparent when a person tries to do something with the affected part and is made worse by stress, fatigue, caffeine and anxiety.

In people with hand tremors, the shaking starts when they try to write or hold a cup of coffee or eat with a utensil. Many people with essential tremor devise ways to avoid such activities, like eating just sandwiches or never eating in public, typing instead of writing or paying by credit card to avoid writing a check.

One woman in Ms. Wisniewski’s book was able to return to college when she learned that disability laws entitled her to a note taker for all her classes. But many employment opportunities are out of reach. Jean Moore worked in a payroll office until she could no longer read her own numbers. Another woman was fired from her job as a waitress when she could no longer carry cups of liquid and plates of food without spilling them.

Head tremor is more difficult to disguise. Some people sit with their elbows planted on a firm surface, holding their head in their hands.

While the disorder can show itself at any age, essential tremor usually does not become apparent until midlife and then worsens with age.

In diagnosing essential tremor, a doctor must first rule out other causes like medications, drug or alcohol withdrawal, excessive caffeine intake, overactive thyroid, heavy metal poisoning, fever and anxiety. A doctor also must check for other neurological conditions like Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis or dystonia.

A number of drugs have been found, mostly by accident, to relieve tremors. They include beta blockers like propranolol, marketed as Inderal, used mainly to control high blood pressure; primidone, found in Mysoline; and topiramate, or Topamax, used mainly to treat epilepsy.

Several other drugs have helped some patients, and sometimes a combination of medications proves helpful. Dosages are limited by the patient’s ability to tolerate side effects. Injections of botulinum toxin A, in Botox, help many people with head tremors.

If drug treatment is not helpful, implanting a stimulator in the thalamus of the brain can block the nerve signals that cause tremors in the upper extremities. The procedure has its hazards and is usually a last resort.

Most people with essential tremor have discovered on their own that alcohol provides temporary relief. But over time, more and more alcohol is needed to be helpful, so excessive intake and alcoholism are real dangers. This remedy is best used sporadically.

Members of the essential tremor foundation have provided a host of “survival” tips that Ms. Wisniewski lists in her book. They include these ideas:

- Using half-full mugs and holding them with all five fingers on the top.

- Using a travel mug with a lid and straw.

- Asking the server to deliver your plate with the food already cut in bite-size pieces.

- Using a bib or fastening the napkin under your chin with a dentist’s chain.

- Writing with a fat pen that has a rubber grip.

- At the computer, wearing wrist weights and keeping palms anchored to the front of the keyboard.

- Using an electric toothbrush and razor.

- Using Velcro instead of buttons.

- Carrying preprinted labels with your name, address and telephone number.

Shedding Light on a Tremor Disorder

By Jane E. Brady : NY Times Article : December 8, 2009

Essential” usually means vital, necessary, indispensable. But in medicine, the word can assume a different cast, meaning inherent or intrinsic, not symptomatic of anything else, lacking a known cause.

Since the mid-19th century, “essential tremor” has been the diagnosis for a disorder of uncontrollable shaking — usually of the hands but sometimes of the head and other body parts, or the voice — that is not due to some other condition. And without knowing what causes it, doctors have been slow to come up with treatments to subdue it.

As a result, millions of individuals suffer to varying degrees with embarrassment and humiliation, social isolation and difficulties holding down a job or performing the tasks of daily life. When you cannot drink a glass of water or eat soup without spilling it because your hand shakes violently, you are unlikely to join others for a dinner out. When you have to depend on someone else to button your shirt or zip your jacket, you may not go out at all.

Wherever those with essential tremor go, people are likely to stare at them and assume they have a drug or alcohol problem, said Catherine Rice, executive director of the International Essential Tremor Foundation in Lenexa, Kan. (Call it at 888-387-3667 or visit its Web site: www.essentialtremor.org.)

Now, thanks to the devoted efforts of a few researchers here and abroad, all this may change. Recent studies have begun to unravel the mysteries of essential tremor, and “essential” may someday be dropped from its name.

“Until very recently,” Dr. Elan D. Louis, a pioneering neurologist and epidemiologist at the College of Physicians and Surgeons at Columbia University, told me, “essential tremor was thought to have no known pathology, no changes in the brain, which led to a medical dead end.” But in the last five years, Dr. Louis said, discoveries in three areas — the brain, clinical findings and genetics and environment — “have changed our understanding of this disease.”

And as our understanding evolves, he predicts that rational therapies will follow.

Common Over Age 65

Essential tremor is a neurological disorder that causes uncontrollable shaking of one or more body parts during voluntary movement. The symptoms disappear at rest. In that way it differs from Parkinson’s disease, in which shaking at rest is a common symptom that disappears during movement. But those with essential tremor are four to five times as likely to develop Parkinson’s as people without tremor, and both conditions involve related changes in the brain.

Though essential tremor most often affects older people — as many as 1 in 5 over 65 have it — it can occur at any age, even in young children. It is typically progressive, getting worse as people age.

Stephen Remillard of Steamboat Springs, Colo., said he learned he had essential tremor while in kindergarten, when it affected just his hands. But the condition worsened as he got older, and by high school, Mr. Remillard said, “all my extremities as well as my voice were affected.” When he had to speak in class, he said, “it came off as if I was nervous, though I’ve always been a very confident person.”

The academic challenges related to tremor prompted him to drop out of college. But the biggest blow to Mr. Remillard’s self-esteem came when he tried to join the military and was rejected by the Army, Marines, Air Force and Coast Guard. Rather than feel sorry for himself, he returned to college, graduating last May, and started playing sports. Now 25, he works for a ski corporation and runs marathons to raise money for causes like the Lance Armstrong Foundation.

For Richard Crandell, a 66-year-old guitarist from Eugene, Ore., the problem began around age 60, forcing him to abandon his instrument. But he, too, was not to be defeated: he took up the mbira, an African thumb piano that he plays with two thumbs and an index finger.

Still, Mr. Crandell said, he has problems shaving, brushing his teeth, using a computer and slicing and dicing in the kitchen. And at the bank, he has to ask the teller to fill in his forms “because my handwriting is all over the place.”

Ms. Rice said essential tremor ran in her family. “My great-aunts used to shake uncontrollably, starting in their early 40s and becoming quite severe by the time they were 60,” she said. “They found it very difficult to cook, though their job was to feed the farmhands. They couldn’t pick up a heavy pan without spilling the contents. They had to give up crocheting and other things they truly loved.”

New Findings

Dr. Louis and colleagues have established a centralized brain repository that has revealed underlying abnormalities in essential tremor patients. The scientists collect detailed clinical and physiological data on each person, and after death their brains are shipped to Columbia, where they are analyzed and compared with the brains of normal individuals.

Of the 50 brains studied so far, Dr. Louis said, “all are degenerative and have very clear pathological changes, although there are several types, suggesting this is probably a family of diseases.” In one subtype, Lewy bodies, which also occur in Parkinson’s disease, are found in the brain but in a different area from Parkinson’s. (Mr. Crandell’s father died of Parkinson’s, and there have been suggestions that the disorders may be linked.)

In about 80 percent of the brains, there are degenerative changes in the cerebellum, including a loss of cells that produce a major inhibitory neurotransmitter called GABA. Other abnormal findings include a messy arrangement of neurofilaments, which may interfere with nerve cell transmission.

Clinically, essential tremor is now considered a neuropsychiatric disease that can include unsteadiness, abnormal eye movements, problems with coordination and cognitive changes that sometimes progress to dementia.

Even certain personality types tend to be overrepresented among patients with essential tremor, Dr. Louis said. Many “are very detail-oriented and tightly wound and have higher harm-avoidance scores,” he said.

Two environmental toxins have been found to be elevated in tremor patients: lead and a dietary chemical called harmane that occurs naturally in plants and animals. When meat is cooked for long periods or at high temperatures, as in barbecuing, levels of harmane rise sharply. Dr. Louis called these “tantalizing leads.”

Despite the problems caused by their disorder, most patients with essential tremor never seek treatment. Two drugs, propranolol (Inderal) and primidone (Mysoline), developed to treat other conditions, have proved helpful for many but not all patients. A costly surgical treatment, deep brain stimulation, has helped to reduce tremors in about 80 percent of patients who have tried it.

Caffeine, certain prescription drugs and undue stress can make symptoms worse and are best avoided. Though alcohol can temporarily relieve tremors, regular heavy drinking is a recognized cause of the disorder .

.

Parkinson's Disease

Parkinson's disease is a disorder of the brain that leads to shaking (tremors) and difficulty with walking, movement, and coordination.

Alternative Names

Paralysis agitans; Shaking palsy

Causes

Parkinson's disease was first described in England in 1817 by Dr. James Parkinson. The disease affects approximately 2 of every 1,000 people and most often develops after age 50. It is one of the most common neurologic disorders of the elderly. Sometimes Parkinson's disease occurs in younger adults, but is rarely seen in children. It affects both men and women.

In some cases, Parkinson's disease occurs within families, especially when it affects young people. Most of the cases that occur at an older age have no known cause.

Parkinson's disease occurs when the nerve cells in the part of the brain that controls muscle movement are gradually destroyed. The damage gets worse with time. The exact reason that the cells of the brain waste away is unknown. The disorder may affect one or both sides of the body, with varying degrees of loss of function.

Nerve cells use a brain chemical called dopamine to help send signals back and forth. Damage in the area of the brain that controls muscle movement causes a decrease in dopamine production. Too little dopamine disturbs the balance between nerve-signalling substances (transmitters). Without dopamine, the nerve cells cannot properly send messages. This results in the loss of muscle function.

Some people with Parkinson's disease become severely depressed. This may be due to loss of dopamine in certain brain areas involved with pleasure and mood. Lack of dopamine can also affect motivation and the ability to make voluntary movements.

Early loss of mental capacities is uncommon. However, persons with severe Parkinson's may have overall mental deterioration (including dementia and hallucinations). Dementia can also be a side effect of some of the medications used to treat the disorder.

Parkinson's in children appears to occur when nerves are not as sensitive to dopamine, rather than damage to the area of brain that produces dopamine. Parkinson's in children is rare.

The term "parkinsonism" refers to any condition that involves a combination of the types of changes in movement seen in Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism may be caused by other disorders (such as secondary parkinsonism) or certain medications used to treat schizophrenia.

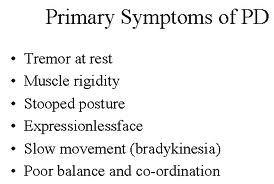

Symptoms »

- Muscle rigidity

- Stiffness

- Difficulty bending arms or legs

- Unstable, stooped, or slumped-over posture

- Loss of balance

- Gait (walking pattern) changes

- Shuffling walk

- Slow movements

- Difficulty initiating any voluntary movement

- Difficulty beginning to walk

- Difficulty getting up from a chair

- Small steps followed by the need to run to maintain balance

- Freezing of movement when the movement is stopped, inability to resume movement

- Muscle aches and pains (myalgia)

- Shaking, tremors (varying degrees, may not be present)

- Characteristically occur at rest, may occur at any time

- May become severe enough to interfere with activities

- May be worse when tired, excited, or stressed

- Finger-thumb rubbing (pill-rolling tremor) may be present

- Changes in facial expression

- Reduced ability to show facial expressions

- "Mask" appearance to face

- Staring

- May be unable to close mouth

- Reduced rate of blinking

- Voice or speech changes

- Slow speech

- Low volume

- Monotone

- Difficulty speaking

- Loss of fine motor skills

- Difficulty writing, may be small and illegible

- Difficulty eating

- Difficulty with any activity that requires small movements

- Uncontrolled, slow movement

- Frequent falls

- Decline in intellectual function (may occur, can be severe)

- A variety of gastrointestinal symptoms, mainly constipation.

Additional symptoms that may be associated with this disease:

- Depression

- Confusion

- Dementia

- Seborrhea (oily skin)

- Loss of muscle function or feeling

- Muscle atrophy

- Memory loss

- Drooling

- Anxiety, stress, and tension

The health care provider may be able to diagnose Parkinson's disease based on your symptoms and physical examination. However, the symptoms may be difficult to assess, particularly in the elderly. For example, the tremor may not appear when the person is sitting quietly with arms in the lap. The posture changes may be similar to osteoporosis or other changes associated with aging. Lack of facial expression may be a sign of depression.

An examination may show jerky, stiff movements, tremors of the Parkinson's type, and difficulty starting or completing voluntary movements. Reflexes are essentially normal.

Tests may be needed to rule out other disorders that cause similar symptoms.

See also: Essential tremor

In-Depth Diagnosis »

There is no known cure for Parkinson's disease. The goal of treatment is to control symptoms.

Medications control symptoms primarily by increasing the levels of dopamine in the brain. The specific type of medication, the dose, the amount of time between doses, or the combination of medications taken may need to be changed from time to time as symptoms change. Many medications can cause severe side effects, so monitoring and follow-up by the health care provider is important.

Types of medication:

- Deprenyl may provide some improvement to mildly affected patients.

- Amantadine or anticholinergic medications may be used to reduce early or mild tremors.

- Levodopa may be used to increase the body's supply of dopamine, which may improve movement and balance.

- Carbidopa reduces the side effects of levodopa and makes levodopa work better.

- Entacapone is used to prevent the breakdown of levodopa.

- Pramipexole and ropinirole are used before or together with levodopa.

- Rasagiline is approved for patients with early Parkinson's disease. It may also be combined with levodopa in patients with more advanced cases of the disease. Rasagiline helps block the breakdown of dopamine.

- Neupro is a new skin patch that contains the drug rotigotine. This medicine helps dopamine receptors in the brain work better. The patch is replaced every 24 hours. Neupro is approved for persons with early stage Parkinson's disease.

Good general nutrition and health are important. Exercise should continue, with the level of activity adjusted to meet the changing energy levels that may occur. Regular rest periods and avoidance of stress are recommended, because fatigue or stress can make symptoms worse. Physical therapy, speech therapy, and occupational therapy may help promote function and independence.

Railings or banisters placed in commonly used areas of the house may be of great benefit to the person experiencing difficulties with daily living activities. Special eating utensils may also be helpful.

Social workers or other counseling services may help the patient cope with the disorder and with obtaining assistance (such as Meals-on-Wheels) as appropriate.

Experimental or less common treatments may be recommended. For example, surgery to implant stimulators or destroy tremor-causing tissues may reduce symptoms in some people. Transplantation of adrenal gland tissue to the brain has been attempted, with variable results.

In-Depth Treatment »

Support Groups

Support groups may help a person cope with the changes caused by the disease.

See: Parkinson's disease - support group

Expectations (prognosis)

Untreated, the disorder progresses to total disability, often accompanied by general deterioration of all brain functions, and may lead to an early death.

Treated, the disorder impairs people in varying ways. Most people respond to some extent to medications. The extent of symptom relief, and how long this control of symptoms lasts, is highly variable. The side effects of medications may be severe.

- Varying degrees of disability

- Difficulty swallowing or eating

- Difficulty performing daily activities

- Injuries from falls

- Side effects of medications

Calling Your Health Care Provider

Call your health care provider if symptoms of Parkinson's disease appear, if symptoms get worse, or if new symptoms occur. Also tell the health care provider about any possible side effects of medications, which may include:

- Involuntary movements

- Nausea and vomiting

- Dizziness

- Changes in alertness, behavior or mood

- Severe confusion or disorientation

- Delusional behavior

- Hallucinations

- Loss of mental functions

The Emotional Toll of Parkinson's Disease

By Marilynn Larkin

Dr. Irene Richard, a movement disorder neurologist and researcher at the University of Rochester, is an investigating senior medical adviser to The Michael J. Fox Foundation, an organization committed to improving the lives of people with Parkinson’s disease. Dr. Richard is an expert on the mental and emotional aspects of the illness and is leading a national study looking into whether medications might help treat depression related to Parkinson’s disease.

Q. You investigate the links between mood disorders and Parkinson’s disease. Isn’t it normal to be depressed after a diagnosis of Parkinson’s?

A. Feeling sad after a diagnosis is understandable. But that’s not the same as depression, which is actually a syndrome with many facets. Up to 40 percent of people with Parkinson’s disease develop this syndrome and experience symptoms that may include depressed mood; decreased interest in people and activities; and problems with sleep, appetite and sex. In contrast to sadness, which usually dissipates as people come to accept their diagnosis, depression may continue for weeks or even years. And there’s increasing evidence that although the symptoms are similar, depression related to Parkinson’s disease may be different from regular depression.

Q. How is depression in Parkinson’s disease different?

A. Research has shown us that in some cases, depression may be the first sign of Parkinson’s disease, appearing well before any motor symptoms, and so we think it may be part of the underlying disease process. But not everyone who has Parkinson’s gets depressed, so there’s probably something going on that makes certain people vulnerable and others not — and this vulnerability doesn’t seem to be related to the severity of the disease or how disabled the person is. So a person with mild Parkinson’s symptoms might become severely depressed, whereas someone with worse symptoms doesn’t.

That said, it can be difficult to diagnose depression in Parkinson’s because other symptoms may mask the depression. For example, people with Parkinson’s tend to move slowly and speak softly, without a lot of inflection. These are also signs of major depression. But when individuals with Parkinson’s behave that way, most people don’t think depression — they just chalk it up to the disease. But if the depression can be appropriately treated, the person’s quality of life will improve, as may some of the symptoms.

So the bottom line is at this point is we don’t know if depression is fundamentally different in Parkinson’s or just looks different because of the company it keeps. But either way, it should be treated.

Q. Can doctors just prescribe antidepressants?

A. It’s not that simple. We can’t just transfer information we know based on the brains of people without Parkinson’s and assume that these drugs will work the same way in people who do. We’ve actually embarked on the first large, multi-center, placebo-controlled clinical trial to see whether antidepressants work and can be tolerated by people with Parkinson’s. Nobody has tried to test this until now.

We’ll also try to see whether antidepressants might affect Parkinson’s motor symptoms. We know that certain types of antidepressants can actually induce Parkinson’s-type symptoms in some people who don’t have the disease. And there’s some evidence that selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and medications with anticholinergic properties, such as tricyclic antidepressants and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, may actually help symptoms of Parkinson’s.

But patients with Parkinson’s generally are on a number of other medications, so we don’t know how well the side effects would be tolerated. For example, a person who doesn’t have Parkinson’s disease might not get dizzy or sedated, but someone with Parkinson’s might. We’ll be trying to answer these questions in our study, which is funded by the National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Stroke and compares venlafaxine (Effexor) or paroxetine (Paxil) to placebo.

Q. What stage has the study reached?

A. Recruitment has been difficult, in part because, as is the case for many mood disorders, doctors don’t recognize when their patients are depressed. And if they do recognize it, there’s a stigma attached to having a “mental” disorder, so people don’t want to admit it. And even if they recognize and admit it, many of the people we want to enroll are tired and apathetic because of their disease, so they don’t want to join clinical trials. So we really have a lot of strikes against us.

On the positive side, anyone who enrolls will get in-depth attention from movement disorder specialists, and they’ll also be contributing to knowledge that will help others.

Q. Are other mental or emotional symptoms common in Parkinson’s?

A. We’ve known for a while that some anti-Parkinson’s medications can trigger hallucinations or delusions in some patients. But more recently, we’ve realized that because Parkinson’s affects multiple domains of brain function, you can get mood fluctuations similar to motor fluctuations, where your brain no longer responds to medication by producing dopamine in a steady state. Instead, you have peaks and valleys that can lead to too much motor activity (“on”) or, at the other extreme, rigidity (“off”).

With mood fluctuations, an individual can transition from being sad and suicidal to euphoric within minutes. The change is very dramatic and disconcerting to the person and the people around him or her.

Not everyone experiences these rapid mood swings, but in those who do, they tend to correlate, time-wise, with motor fluctuations. This means someone may be depressed when “off” and normal mood or euphoric when “on.” But having said that, my group has done some research looking at diaries in which patients documented their motor state and their mood hourly for seven days. We found wide variations in mood and motor fluctuations, even for the same individual, over the course of a week. And although the two types of fluctuations correlated in the majority of patients, there was a subset in which they did not.

So it appears there are two independent fluctuations going on in the brain, one for mood and one for motor. This can be very upsetting; it’s like bipolar disorder on a daily basis — you just go from one extreme to another. So we and others are looking into the mechanisms behind these fluctuations, and hopefully at some point, we’ll have a treatment.

Q. What is the most challenging part of your work?

A. Getting people to pay attention to the emotional aspects of the disease. In my work with patients, I’ve been really struck by the way they struggle not only with motor symptoms, but also from emotional symptoms. This has really motivated me to work on these conditions and help raise awareness.

Q. Is awareness of the emotional aspects of Parkinson’s disease increasing?

A. I have to say it’s finally starting to happen. Society’s awareness about mental illness over all is being raised and, hopefully, there will be less stigma attached to it. And in the setting of Parkinson’s disease, these conditions are now on the radar screen. The Michael J. Fox Foundation has asked researchers to apply for grants looking at psychiatric outcomes in Parkinson’s, which is great. We’re also trying to interest researchers involved in emotional and mental disorders in other neurological diseases, like Alzheimer’s, to also focus on Parkinson’s.

Hospital Dangers for Patients With Parkinson’s

By Paula Span : NY Times : April 17, 2013

It was supposed to be a short stay. In 2006, Roger Anderson was to undergo surgery to relieve a painfully compressed spinal disk. His wife, Karen, figured the staff at the hospital, in Portland, Ore., would understand how to care for someone with Parkinson’s disease.

It can be difficult. Parkinson’s patients like Mr. Anderson, for example, must take medications at precise intervals to replace the brain chemical dopamine, which is diminished by the disease. “You don’t have much of a window,” Mrs. Anderson said. “If you have to wait an hour, you have tremendous problems.” Without these medications, people may “freeze” and be unable to move, or develop uncontrolled movements called dyskinesia, and are prone to falls.

But the nurses at the Portland hospital didn’t seem to grasp those imperatives. “You’d have to wait half an hour or an hour, and that’s not how it works for Parkinson’s patients,” Mrs. Anderson said. Nor did hospital rules, at the time, permit her to simply give her husband the Sinemet pills on her own.

Surgery and anesthesia, the disrupted medications, an incision that subsequently became infected — all contributed to a tailspin that lasted nearly three months. Mr. Anderson developed delirium, rotated between rehab centers and hospitals, took a fall, lost 60 pounds. “People were telling me, ‘He’s never going to come home,’” Mrs. Anderson said.

He did recover, and at 69 is doing well, his wife said, though his disease has progressed. But his wasn’t an unusual story, neurologists say.

Any older person faces dangers in a hospital, but for people with Parkinson’s — largely a disease of older adults — they’ve proved particularly hazardous. “Patients were telling us these horrendous stories,” said Dr. Michael Okun, a University of Florida neurologist and national medical director of the National Parkinson Foundation. “Even in good hospitals. Even in my own hospital.”

People with Parkinson’s are hospitalized much more frequently than others their age, and their stays last longer. A common reason: “These patients aren’t getting their meds on time, and they’re not getting the right meds,” Dr. Okun said. Some need to take their dopamine-replacing drugs as often as every two hours, a schedule at odds with standard hospital regimens.

Worse, some commonly prescribed drugs — including Compazine and Phenergan for nausea, and Reglan to stimulate bowel function after surgery — actually block dopamine and worsen symptoms in patients with Parkinson’s. Then they are at risk for falls and fractures and for aspiration pneumonia.

Moreover, any infection can lead to delirium, because Parkinson’s patients have lowered cognitive reserve. But the drug Haldol, which hospitals frequently use to reduce confusion, is also a dopamine blocker. “Haldol is the worst drug you can give a Parkinson’s patient,” Dr. Okun said. Over all, “it can be a real mess.”

With proper treatment, most Parkinson’s patients can live long and good lives, “but stressing them with a fall or an infection or anesthesia can make them fall apart,” he said, turning supposed in-and-out hospitalizations into weeks of illness and decline. Not everyone is as lucky as Roger Anderson.

What will help, in the long run, is educating hospital staffs about Parkinson’s and changing the way they function. And yet — isn’t this a sad commentary? — “it’s slow going to effect change in the health care system, and in the meantime a lot of people are getting hurt,” Dr. Okun said.

So, unfair as it may be to put the onus on patients and families, the foundation is offering a free Aware in Care kit that includes a bracelet identifying the wearer as a Parkinson’s patient and fact sheets and reminder slips to hand out to doctors and nurses. “We want to arm people,” Dr. Okun said.

The Andersons have used the kit for subsequent hospitalizations and found it useful. And Mrs. Anderson reports that now, years after their three-month nightmare, hospitals actually encourage her to bring along her husband’s medications and to administer the pills herself as his schedule demands.

You might argue that the hospital is magnanimously allowing her to do the job its staff is supposed to do, but she’s fine with that. It beats the alternative.