- RETIREMENT ANNOUNCEMENT

- HOME PAGE

- "MYCHART" the new patient portal

- BELMONT MEDICAL ASSOCIATES

- MOUNT AUBURN HOSPITAL

- EMERGENCIES

- PRACTICE PHILOSOPHY

- MY RESUME

- TELEMEDICINE CONSULTATION

- CONTACT ME

- LAB RESULTS

- ePRESCRIPTIONS

- eREFERRALS

- RECORD RELEASE

- MEDICAL SCRIBE

- PHYSICIAN ASSISTANT (PA)

- Medicare Annual Wellness Visit

- Case management/Social work

- Quality Care Measures

- Emergency closing notice

- FEEDBACK

- Talking to your doctor

- Choosing..... and losing a doctor

- INDEX A - Z

- ALLERGIC REACTIONS

- Alternative Medicine

- Alzheimer's Disease

- Bladder Problems

- Blood disorders

- Cancer Concerns

- GENETIC TESTING FOR HEREDITARY CANCER

- Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

- Controversial Concerns

- CPR : Learn and save a life

- CRP : Inflammatory marker

- Diabetes Management

- Dizziness, Vertigo,Tinnitus and Hearing Loss

- EXERCISE

- FEMALE HEALTH

-

GASTROINTESTINAL topics

- Appendicitis

- BRAT diet

- Celiac Disease or Sprue

- Crohn's Disease

- Gastroenterologists for Colon Cancer Screening

- Colonoscopy PREP

- Constipation

- Gluten sensitivity, but not celiac disease

- Heartburn and GERD

- Hemorrhoids and Anal fissure

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- NASH : Non Alcoholic Steato Hepatitis

- FEET PROBLEMS

- HEART RELATED topics

-

INFECTIOUS DISEASES

- Antibiotic Resistance

- Cat bites >

- Clostridia difficile infection - the "antibiotic associated germ"

- CORONA VIRUS

- Dengue Fever and Chikungunya Fever

- Food borne illnesses

- Shingles Vaccine

- Hepatitis B

- Hepatitis C

- Herpes

- Influenza

- Helicobacter pylori - the "ulcer germ"

- HIV Screening

- Lyme and other tick borne diseases

- Measles

- Meningitis

- MRSA (Staph infection)

- Norovirus

- Sexually Transmitted Diseases

- Shingles (Herpes Zoster)

- Sinusitis

- West Nile Virus

- Whooping Cough (Pertussis)

- Zika virus and pregnancy

- INSURANCE related topics

- KIDNEY STONES

- LEG CRAMPS

- LIBRARY for patients

- LIFE DECISIONS

- MALE HEALTH

- Medication/Drug side effects

- MEDICAL MARIJUANA

- MENTAL HEALTH

- Miscellaneous Articles

-

NUTRITION - EXERCISE - WEIGHT

- Cholesterol : New guidelines for treatment

- Advice to lower your cholesterol

- Cholesterol : Control

- Cholesterol : Raising your HDL Level

- Exercise

- Food : Making Smart Choices

- Food : Making Poor Choices

- Food : Grape Fruit and Drug Interaction

- Food : Vitamins, Minerals and Supplements

- Omega 3 fatty acids

- Vitamin B12 deficiency

- Vitamin D

- Weight Loss

- ORTHOPEDICS

- PAIN

- PATIENTS' RIGHTS

- SKIN

- SLEEP

- SMOKING

- STROKE

- THYROID

- SUBSTANCE ABUSE

- Travel and Vaccination

- TREMOR

- Warfarin Anticoagulation

- OTHER STUFF FOLLOWS

- Fact or Opinion?

- Hippocratic Oath

- FREE ADVICE.......for what its worth!

- LAUGHTER.....is the best medicine

- Physicians Pet Peeves

- PHOTO ALBUM - its not all work!

- Cape Town, South Africa

- Tribute page

- The 100 Club

- Free Wi-Fi

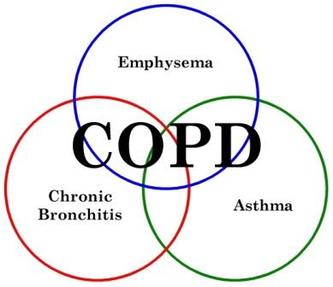

COPD

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

COPD is characterized "by airflow limitation that is not fully reversible.The airflow limitation is usually progressive and associated with an abnormal inflammatory response of the lung to noxious particles or gases."

What is COPD?

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a lung disease in which the lungs are damaged, making it hard to breathe. In COPD, the airways—the tubes that carry air in and out of your lungs—are partly obstructed, making it difficult to get air in and out.

Cigarette smoking is the most common cause of COPD. Most people with COPD are smokers or former smokers. Breathing in other kinds of lung irritants, like pollution, dust, or chemicals, over a long period of time may also cause or contribute to COPD.

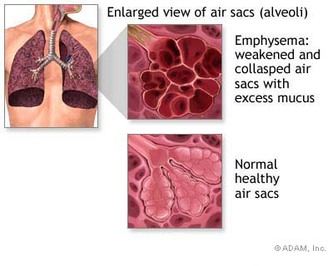

The airways branch out like an upside-down tree, and at the end of each branch are many small, balloon-like air sacs. In healthy people, each airway is clear and open. The air sacs are small and dainty, and both the airways and air sacs are elastic and springy. When you breathe in, each air sac fills up with air like a small balloon; when you breathe out, the balloon deflates and the air goes out. In COPD, the airways and air sacs lose their shape and become floppy. Less air gets in and less air goes out because:

COPD is a major cause of death and illness, and it is the fourth leading cause of death in the United States and throughout the world.

There is no cure for COPD. The damage to your airways and lungs cannot be reversed, but there are things you can do to feel better and slow the damage.

COPD is not contagious—you cannot catch it from someone else.

How the Lungs Work

The lungs provide a very large surface area (the size of a football field) for the exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide between the body and the environment.

A slice of normal lung looks like a pink sponge filled with tiny bubbles or holes. These bubbles, surrounded by a fine network of tiny blood vessels, give the lungs a large surface to exchange oxygen (into the blood where it is carried throughout the body) and carbon dioxide (out of the blood). This process is called gas exchange. Healthy lungs do this very well.

Here is how normal breathing works:

The airways and air sacs in the lung are normally elastic—that is, they try to spring back to their original shape after being stretched or filled with air, just the way a new rubber band or balloon would. This elastic quality helps retain the normal structure of the lung and helps to move the air quickly in and out. In COPD, much of the elastic quality is gone, and the airways and air sacs no longer bounce back to their original shape. This means that the airways collapse, like a floppy hose, and the air sacs tend to stay inflated. The floppy airways obstruct the airflow out of the lungs, leading to an abnormal increase in the lungs' size. In addition, the airways may become inflamed and thickened, and mucus-producing cells produce more mucus, further contributing to the difficulty of getting air out of the lungs.

Other Names for COPD

In chronic bronchitis, the airways have become inflamed and thickened, and there is an increase in the number and size of mucus-producing cells. This results in excessive mucus production, which in turn contributes to cough and difficulty getting air in and out of the lungs.

Most people with COPD have both chronic bronchitis and emphysema.

What Causes COPD?

Smoking Is the Most Common Cause of COPD

Most cases of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) develop after repeatedly breathing in fumes and other things that irritate and damage the lungs and airways. Cigarette smoking is the most common irritant that causes COPD. Pipe, cigar, and other types of tobacco smoke can also cause COPD, especially if the smoke is inhaled. Breathing in other fumes and dusts over a long period of time may also cause COPD. The lungs and airways are highly sensitive to these irritants. They cause the airways to become inflamed and narrowed, and they destroy the elastic fibers that allow the lung to stretch and then return to its resting shape. This makes breathing air in and out of the lungs more difficult.

Other things that may irritate the lungs and contribute to COPD include:

Genes—tiny bits of information in your body cells passed on by your parents—may play a role in developing COPD. In rare cases, COPD is caused by a gene-related disorder called alpha 1 antitrypsin deficiency. Alpha 1 antitrypsin is a protein in the blood that inactivates destructive proteins. People with antitrypsin deficiency have low levels of alpha 1 antitrypsin; the imbalance of proteins leads to the destruction of the lungs and COPD. If people with this condition smoke, the disease progresses more rapidly.

Who Is At Risk for COPD?

Most people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are smokers or were smokers in the past. People with a family history of COPD are more likely to get the disease if they smoke. The chance of developing COPD is also greater in people who have spent many years in contact with lung irritants, such as:

Most people with COPD are at least 40 years old or around middle age when symptoms start. It is unusual, but possible, for people younger than 40 years of age to have COPD.

What Are the Signs and Symptoms of COPD?

The signs and symptoms of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) include:

The severity of the symptoms depends on how much of the lung has been destroyed. If you continue to smoke, the lung destruction is faster than if you stop smoking.

How Is COPD Diagnosed?

Doctors consider a diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) if you have the typical symptoms and a history of exposure to lung irritants, especially cigarette smoking. A medical history, physical exam, and breathing tests are the most important tests to determine if you have COPD.

Your doctor will examine you and listen to your lungs. Your doctor will also ask you questions about your family and medical history and what lung irritants you may have been around for long periods of time.

Breathing Tests

Your doctor will use a breathing test called spirometryto confirm a diagnosis of COPD. This test is easy and painless and shows how well your lungs work. You breathe hard into a large hose connected to a machine called a spirometer. When you breathe out, the spirometer measures how much air your lungs can hold and how fast you can blow air out of your lungs after taking a deep breath.

Spirometry is the most sensitive and commonly used test of lung functions. It can detect COPD long before you have significant symptoms.

Based on this test, your doctor can determine if you have COPD and how severe it is. Doctors classify the severity of COPD as:

Quitting smoking is the single most important thing you can do to reduce your risk of developing chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and slow the progress of the disease.

Your doctor will recommend treatments that help relieve your symptoms and help you breathe easier. However, COPD cannot be cured.

The goals of COPD treatment are to:

Treatment is based on whether your symptoms are mild, moderate, or severe.

Medicines and pulmonary rehabilitation (rehab) are often used to help relieve your symptoms and to help you breathe more easily and stay active.

COPD Medicines

Bronchodilators

Physicians may recommend medicines called bronchodilators that work by relaxing the muscles around your airways. This type of medicine helps to open your airways quickly and make breathing easier. Bronchodilators can be either short acting or long acting.

If you have mild COPD, your doctor may recommend that you use a short-acting bronchodilator. You then will use the inhaler only when needed.

If you have moderate or severe COPD, your doctor may recommend regular treatment with one or more inhaled bronchodilators. You may be told to use one long-acting bronchodilator. Some people may need to use a long-acting bronchodilator and a short-acting bronchodilator. This is called combination therapy.

Inhaled glucocorticosteroids (steroids)

Inhaled steroids are used for some people with moderate or severe COPD. Inhaled steroids work to reduce airway inflammation. We may recommend that you try inhaled steroids for a trial period of 6 weeks to 3 months to see if the medicine is helping with your breathing problems.

Spiriva® (tiotropium bromide inhalation powder)

This is indicated for the long-term, once-daily, maintenance treatment of bronchospasm associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), including chronic bronchitis and emphysema.

Spiriva is not indicated for the initial treatment of acute episodes of bronchospasm, i.e., rescue therapy and is contraindicated in patients with a history of hypersensitivity to atropine or its derivatives.

Flu shots

The flu (influenza) can cause serious problems in people with COPD. Flu shots can reduce the chance of getting the flu. You should get a flu shot every year.

Pneumococcal vaccine

This vaccine should be administered to those with COPD to prevent a common cause of pneumonia. Revaccination may be necessary after 5 years in those older than 65 years of age.

Pulmonary Rehabilitation

Pulmonary rehabilitation (rehab) is a coordinated program of exercise, disease management training, and counseling that can help you stay more active and carry out your day-to-day activities. What is included in your pulmonary rehab program will depend on what you and your doctor think you need. It may include exercise training, nutrition advice, education about your disease and how to manage it, and counseling. The different parts of the rehab program are managed by different types of health care professionals (doctors, nurses, physical therapists, respiratory therapists, exercise specialists, dietitians) who work together to develop a program just for you. Pulmonary rehab programs can include some or all of the following aspects.

Medical evaluation and management

To decide what you need in your pulmonary rehab program, a medical evaluation will be done. This may include getting information on your health history and what medicines you take, doing a physical exam, and learning about your symptoms. A spirometry measurement may also be done before and after you take a bronchodilator medicine.

Setting goals

You will work with your pulmonary rehab team to set goals for your program. These goals will look at the types of activities that you want to do. For example, you may want to take walks every day, do chores around the house, and visit with friends. These things will be worked on in your pulmonary rehab program.

Exercise training

Your program may include exercise training. This training includes showing you exercises to help your arms and legs get stronger. You may also learn breathing exercises that strengthen the muscles needed for breathing.

Education

Many pulmonary rehab programs have an educational component that helps you learn about your disease and symptoms, commonly used treatments, different techniques used to manage symptoms, and what you should expect from the program. The education may include meeting with (1) a dietitian to learn about your diet and healthy eating; (2) an occupational therapist to learn ways that are easier on your breathing to carry out your everyday activities; or (3) a respiratory therapist to learn about breathing techniques and how to do respiratory treatments.

Program results (outcomes)

You will talk with your pulmonary rehab team at different times during your program to go over the goals that you set and see if you are meeting them. For example, if your goal is to walk every day for 30 minutes, you will talk to members of your pulmonary team and tell them how often you are walking and for how long. The team is interested in helping you reach your goals.

Oxygen Treatment

If you have severe COPD and low levels of oxygen in your blood, you are not getting enough oxygen on you own. Your doctor may recommend oxygen therapy to help with your shortness of breath. You may need extra oxygen all the time or some of the time. For some people with severe COPD, using extra oxygen for more than 15 hours a day can help them:

For some people with severe COPD, surgery may be recommended. Surgery is usually done for people who have:

How Can COPD Be Prevented From Progressing?

If you smoke, the most important thing you can do to stop more damage to your lungs is to quit smoking. Many hospitals have smoking cessation programs or can refer you to one.

It is also important to stay away from people who are smoking and places where you know there will be smokers.

Staying away from other lung irritants such as pollution, dust, and certain cooking or heating fumes is also important. For example, you should stay in your house when the outside air quality is poor.

Managing Complications and Preventing Sudden Onset of Problems

People with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) often have symptoms that suddenly get worse. When this happens, you have a much harder time catching your breath. You may also have chest tightness, more coughing, change in your sputum, and a fever. It is important to call your doctor if you have any of these signs or symptoms.

We will look at things that might be causing these signs and symptoms to suddenly worsen. Sometimes the signs and symptoms are caused by a lung infection. We may want you to take an antibiotic medicine that helps fight off the infection.

We may also recommend additional medicines to help with your breathing. These medicines include bronchodilators and glucocorticosteroids.

We may recommend that you spend time in the hospital if:

Although there is no cure for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), your symptoms can be managed, and damage to your lungs can be slowed. If you smoke, quitting is the most important thing you can do to help your lungs. Information is available on ways to help you quit smoking. You also need to try to stay away from people who are smoking or places where there is smoking.

It is important to keep the air in your home clean. Here are some things that may help you in your home:

See your doctor at least two times a year, even if you are feeling fine. Make sure you bring a list of medicines you are taking to your doctor visit.

Ask your us about getting a flu shot and pneumonia vaccination.

Keep your body strong by learning breathing exercises and walking and exercising regularly.

Eat healthy foods. Ask your family to help you buy and fix healthy foods. Eat lots of fruits and vegetables. Eat protein food like meat, fish, eggs, milk, and soy.

If you have been told you that you have severe COPD, there are some things that you can do to get the most out of each breath. Make your life as easy as possible at home by:

Six Killers: Lung Disease

From Smoking Boom, a Major Killer of Women

By Denise Grady : NY Times Article : November 29, 2007

For Jean Rommes, the crisis came five years ago, on a Monday morning when she had planned to go to work but wound up in the hospital, barely able to breathe. She was 59, the president of a small company in Iowa. Although she had quit smoking a decade earlier, 30 years of cigarettes had taken their toll.

After several days in the hospital, she was sent home tethered to an oxygen tank, with a raft of medicines and a warning: “If I didn’t do something, life was going to continue to be a pretty scary experience.”

Ms. Rommes has chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or C.O.P.D., a progressive illness that permanently damages the lungs and is usually caused by smoking. Once thought of as an old man’s disease, this disorder has become a major killer in women as well, the consequence of a smoking boom in the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s. The death rate in women nearly tripled from 1980 to 2000, and since 2000, more women than men have died or been hospitalized every year because of the disease.

“Women started smoking in what I call the Virginia Slims era, when they started sponsoring sporting events,” said Dr. Barry J. Make, a lung specialist at National Jewish Medical and Research Center in Denver. “It’s now just catching up to them.”

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease actually comprises two illnesses: one, emphysema, destroys air sacs deep in the lungs; the other, chronic bronchitis, causes inflammation, congestion and scarring in the airways. The disease kills 120,000 Americans a year, is the fourth leading cause of death and is expected to be third by 2020. About 12 million Americans are known to have it, including many who have long since quit smoking, and studies suggest that 12 million more cases have not been diagnosed. Half the patients are under 65. The disease has left some 900,000 working-age people too sick to work and costs $42 billion a year in medical bills and lost productivity.

“It’s the largest uncontrolled epidemic of disease in the United States today,” said Dr. James Crapo, a professor at the National Jewish Medical and Research Center.

Experts consider the statistics a national disgrace. They say chronic lung disease is misdiagnosed, neglected, improperly treated and stigmatized as self-induced, with patients made to feel they barely deserve help, because they smoked. The disease is mired in a bog of misconception and prejudice, doctors say. It is commonly mistaken for asthma, especially in women, and treated with the wrong drugs.

Although incurable, it is treatable, but many patients, and some doctors, mistakenly think little can be done for it. As a result, patients miss out on therapies that could help them feel better and possibly live longer. The therapies vary, but may include drugs, exercise programs, oxygen and lung surgery.

Incorrectly treated, many fall needlessly into a cycle of worsening illness and disability, and wind up in the emergency room over and over again with pneumonia and other exacerbations — breathing crises like the one that put Ms. Rommes in the hospital — that might have been averted.

“Patients often come to me with years of being under treated,” said Dr. Byron Thomashow, the director of the Center for Chest Disease at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia hospital.

Still others are overtreated for years with steroids like prednisone, which is meant for short-term use and if used too much can thin the bones, weaken muscles and raise the risk of cataracts.

Adequate treatment means drugs, usually inhaled, that open the airways and quell inflammation — preventive medicines that must be used daily, not just in emergencies. It is essential to quit smoking.

Patients also need antibiotics to fight lung infections, vaccines to prevent flu and pneumonia and lessons on special breathing techniques that can help them make the most of their diminished lungs. Some need oxygen, which can help them be more active and prolong life in severe cases. Many need dietary advice: obesity can worsen symptoms, but some with advanced disease lose so much weight that their muscles begin to waste. Some people with emphysema benefit from surgery to remove diseased parts of their lungs.

Above all, patients need exercise, because shortness of breath drives many to become inactive, and they become increasingly weak, homebound, disabled and depressed. Many could benefit from therapy programs called pulmonary rehabilitation, which combine exercise with education about the disease, drugs and nutrition, but the programs are not available in all parts of the country, and insurance coverage for them varies.

“I have a complicated, severe group of patients, but I will swear to you that very few wind up in hospitals,” Dr. Thomashow said. “I treat aggressively. I use the medicines, I exercise all of them. You can make a difference here. This is an example of how we’re undertreating this entire disease.”

Little-Known Epidemic

Researchers say there is so little public awareness of how common and serious C.O.P.D. is that the O might as well stand for “obscure” or “overlooked.”

The disease may not be well known, but people who have it are a familiar sight. They are the ones who cannot climb half a flight of stairs without getting winded, who have a perpetual smoker’s cough or wheeze, who need oxygen to walk down the block or push a cart through the supermarket. Some grow too weak and short of breath to leave the house. The flu or even a cold can put them in the hospital. In advanced stages, the lung disease can lead to heart failure.

“This is a disease where people eventually fade away because they can no longer cope with life,” said Grace Anne Dorney Koppel, who has chronic lung disease. (Ms. Dorney Koppel, a lawyer, is married to Ted Koppel.) “My God, if you don’t have breath, you don’t have anything.”

Most cases, about 85 percent, are caused by smoking, and symptoms usually start after age 40, in people who have smoked a pack a day for 10 years or more. In the United States, 45 million people smoke, 21 percent of adults. Only about 20 percent of smokers develop chronic lung disease.

The illness is not the same as asthma, but some patients have asthma along with their other lung problems. Most have a combination of emphysema and chronic bronchitis. In about one-sixth of cases, emphysema is the main problem. Women are far more likely than men to develop chronic bronchitis, and are less prone to emphysema. Some studies have suggested that women’s lungs are more sensitive than men’s to the toxins in smoke.

Worldwide, these lung diseases kill 2.5 million people a year. An article in September in The Lancet, a medical journal, said that “if every smoker in the world were to stop smoking today, the rates of C.O.P.D. would probably continue to increase for the next 20 years.” The reason is that although quitting slows the disease, it can develop later.

Cigarettes are the major cause worldwide, but other sources are important in developing countries, especially smoke from indoor fires that burn wood, coal, straw or dung for heating and cooking. Women and children are most likely to be exposed. Outdoor air pollution plays less of a part: it can aggravate existing disease, but is believed to cause only 1 percent of cases in rich countries and 2 percent in poorer ones. Occupational exposures in cotton mills and mines may contribute.

Researchers have differed about whether passive smoking plays a role, but a Lancet article in September predicted that in China, among the 240 million people who are now over 50, 1.9 million who never smoked will die from chronic lung disease — just from exposure to other people’s smoke.

Many patients with lung disease have other illnesses as well, like heart disease, acid reflux, hypertension, high cholesterol, sinus problems or diabetes. Compared with other smokers, those with C.O.P.D. are more likely to develop lung cancer as well. Researchers suspect that all the ailments stem partly from the same underlying condition, widespread inflammation, a reaction by the immune system that can affect blood vessels, organs and tissues all over the body.

Lung disease can creep up insidiously, because human beings have lung power to spare. Millions of airways, with enough surface area to cover a tennis court, provide so much reserve that most people would not notice it if they lost the use of a third or even half of a lung. But all that extra capacity can hide an impending disaster.

“If it comes on gradually, the body can adjust,” said Dr. Neil Schachter, a lung specialist and professor at Mount Sinai Medical Center in New York. “Some of these patients are at oxygen levels where you and I would be gasping for breath.”

People adjust psychologically as well, cutting back their activities, deciding perhaps that they just do not enjoy sports anymore, that they are getting older, gaining weight or a bit out of shape. But at some point the body can no longer compensate, and denial does not work anymore.

“It’s like trying to breathe through a straw,” Dr. Schachter said. “It’s very uncomfortable.”

By then, half a lung might be ruined. On a CT scan, he said, the lungs may look “moth-eaten,” full of holes where tissue has been destroyed.

Often, the diagnosis is not made until the disease is advanced. Even though breathing tests are easy to perform and recommended for high-risk patients like former and current smokers, many doctors do not bother. People who do get a diagnosis frequently are not taught how to use the inhalers that are the mainstay of treatment. Access to pulmonary rehabilitation is limited because Medicare has left coverage decisions to the states. Some programs have shut down, and there are bills in the House and Senate that would require pulmonary rehabilitation to be covered by Medicare. Medicare may also reduce coverage for home oxygen.

Meanwhile, billions are spent on treating exacerbations, episodes of severe breathing trouble that are often caused by colds, flu or other respiratory infections.

A recent study of 1,600 consecutive hospitalizations for chronic lung disease in five New York hospitals found that once patients were in the hospital, their treatment was generally correct, Dr. Thomashow said. But “most upsetting,” he said, was that the majority had been incorrectly treated before going to the hospital.

For many, trying to control the disease, rather than be controlled by it, is a daily struggle. Diane Williams Hymons, 57, a social service consultant and therapist in Silver Spring, Md., has had lifelong problems with bronchitis, allergies and asthma. In the last five or 10 years, her breathing difficulties have worsened, but she was told only three years ago that she had C.O.P.D. It motivated her to give up cigarettes, after smoking for more than 30 years.

“I have good days, and days that aren’t as great,” she said. “I sometimes have trouble walking up steps. I have to stop and catch my breath.”

She is “usually fine” when sitting, she said.

Her mother, also a former smoker with chronic lung disease, has been in a pulmonary rehabilitation program. Ms. Williams Hymons’s doctor has not recommended such a program for her, but she has no idea why. They have discussed surgery to remove part of her lungs, which helps some people with emphysema, but she said no decision had been made yet because it is not clear whether her main problem is emphysema or asthma. She is not sure what her prognosis is.

A Risky Approach

Ms. Williams Hymons has been taking prednisone pills for years, something both she and her doctor know is risky. But when she tries to cut back, the disease flares up. She has many side effects from the drug.

“My bone density is not looking real good,” she said. “I have cramps in my hands and feet, weight gain and bloating, the moon face, excess facial hair, fat deposits between my shoulder blades. Yes, I have those.”

She has broken two ribs just from coughing, probably because the prednisone has thinned her bones, she said. She went to a hospital for the rib pain last year and was given so much asthma medication to stop the coughing that it caused abnormal heart rhythms. She wound up in the cardiac unit for five days, and now says “never again” to being hospitalized.

Her doctor orders regular bone density tests.

“I know he’s concerned, like I’m concerned,” Ms. Williams Hymons said, “but we can’t seem to kind of get things under control.”

A recent study of 25 primary care practices around the United States treating chronic lung disease found that most did not perform spirometry, a simple breathing test used to diagnose or monitor the disease, even when they had the equipment to do so. The test takes only a few minutes, but doctors said there was not enough time during the usual 15-minute visit. Similarly, the practices did not offer much help with smoking cessation.

The author of the study (published in August in The American Journal of Medicine), Pamela L. Moore, said many of the doctors felt unable to help smokers quit, and believed that as long as patients kept smoking, treatments for lung disease would be for nought. But Dr. Moore said research had found that people are more likely to quit or start cutting back if doctors recommend it.

Labeling the disease self-induced is “an unbelievably painful concept,” Dr. Thomashow said. “Patients blame themselves, their family blames them, we even have evidence that health providers blame them.”

Shame and Blame

Indeed, a patient at a clinic in Manhattan, with nasal oxygen tubing attached to equipment in a backpack, said, “This is one of the evils you must suffer for the things we did in our life.”

Smoking also contributes to heart disease, Dr. Thomashow said, and yet people “don’t waste time blaming the patient.”

“This disease quite frankly has an image problem,” said Dr. James Kiley, the director of lung research at the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, which started a campaign last January to educate people about the disease.

In one way or another every patient seems to have encountered what John Walsh, president of the C.O.P.D. Foundation, calls the “shame and blame” attached to this disease.

It is a familiar theme to Ms. Dorney Koppel, who agreed to become a spokeswoman for the institute’s education campaign. She was surprised to be asked to help, she said, because the campaign needed a celebrity, and she is merely married to one. She asked the person who invited her, whether there were no famous people with C.O.P.D.

“I was told, ‘None who will admit it,’” she said.

Ms. Dorney Koppel, who is candid about being a former smoker, calls the illness the Rodney Dangerfield of diseases.

“You don’t get no respect,” she said. “I have to pay publicly for my sins. I have paid.”

Like many patients, Ms. Rommes has both emphysema and chronic bronchitis, along with asthma. She had symptoms for years before receiving the correct diagnosis.

She began smoking in college during the 1960s, when she was 18. People whom she admired smoked, and it seemed cool. She smoked for 30 years.

When she quit in 1992, it was not because she thought she was ill, but because she realized that she was organizing her day around chances to smoke. But she almost certainly was ill. She was only 50, but climbing a flight of stairs left her winded. From what she found in medical dictionaries, she began to suspect she had lung disease.

By 2000 she was so short of breath that she consulted her doctor about it.

He gave her a spirometry test. In one second, healthy adults should be able to blow out 80 percent of the total they can exhale; her score was 34 percent, which, she knows now, indicated moderate to severe lung disease.

“I honestly don’t know whether he knew,” she said of her doctor. “I suspect he did, but he didn’t call it emphysema.”

“He put me on a couple of inhalers and he called it asthma,” Ms. Rommes said. “I sort of ignored the whole thing, because the inhalers did make me feel better. I started to gain some weight, and things got progressively worse.”

She cannot help wondering now if she could have avoided becoming so desperately ill, if she had only known sooner what a dangerous illness she had.

The turning point came in February 2003 when she tried to take a shower and found that she could not breathe. The steam all but suffocated her. She managed to drive from her home in Osceola, Iowa, to her doctor’s office, struggle across the parking lot like someone climbing a mountain and collapse, gasping, onto a couch inside the clinic. Her blood oxygen was perilously low, two-thirds of normal, even when she was given oxygen. The hospital was next door, and her doctor had her admitted immediately.

Fear and Anger

She had Type 2 diabetes as well as lung disease, and her doctor told her that losing weight would help both illnesses. But she said, “He made it pretty clear that he didn’t think I would or could.”

Motivated by fear and anger, she began riding an exercise bike, walking on a treadmill, lifting weights at a gym and eating only 1,200 to 1,500 calories a day, mostly lean meat with plenty of vegetables and fruit.

“I kind of came to the conclusion that if I didn’t, I probably wasn’t going to be around,” Ms. Rommes said. “I wasn’t ready to check out. And my husband was beginning to show the signs of Alzheimer’s disease. I knew that if I couldn’t continue to manage our affairs, it wasn’t going to work out.”

By December 2003, her efforts were starting to pay off. She went from needing oxygen around the clock to using it only for sleeping, and by January 2005 she no longer needed it at all. She was able to lower the doses of her inhalers and diabetes medicines. By February 2005, she had lost 100 pounds.

The daily exercise also helped her deal with the stress of her husband’s illness. He died in June.

“I had no clue that exercise would do as much for ability to breathe as it did,” she said, adding that it helped more than the drugs, which she described as “really pretty minimal.”

She is hooked on exercise now, getting up every morning at 5 a.m. to walk for 45 minutes on the treadmill. She goes at it hard enough to break a sweat, wearing a blood oxygen monitor to make sure her level does not dip too low (if it does, she slows down or uses special breathing techniques to bring it up). She walks outdoors, as well, and three times a week, she works out with weights at a gym.

“Exercise is absolutely essential, and it’s essential to start it as soon as you know you have C.O.P.D.,” she said.

Exercise does not heal or strengthen the lungs themselves, but it improves overall fitness, which people with lung disease need desperately because their shortness of breath leads to inactivity, muscle wasting and loss of stamina.

“Both my pulmonologist and my regular doctor have made it really, really clear to me that I have not increased my lung capacity at all,” Ms. Rommes said. “But I’ve improved the mechanics. I’ve done everything I know how to do to make the lung capacity as efficient as possible. That’s the key for me; I know there are lots of people with this disease who don’t exercise, who I guess just give up.”

She realizes that she has two serious chronic diseases that could shorten her life. But it does not worry her much, she said, because she figures she is doing everything she can to take care of herself, and would rather spend her time enjoying life — work, reading, opera, traveling, children and grandchildren.

“I will tell pretty much anybody that I have emphysema,” Ms. Rommes said. “They say, ‘Did you smoke?’ I say, ‘Yes I did, for 30 years, and I quit in 1992.’ Maybe it’s why I’ve attacked this the way I did. O.K., I did it to myself, and so I better do everything I can to get out of it. We all do things in our lives that are stupid, and then you do what you can to fix it.”

Questions for Your Doctor : What to Ask About C.O.P.D.

By Aliyah Baruchin : NY Times Article : November 28, 2007

Confronting a new diagnosis can be frightening -- and because research changes so often, confusing. Here are some questions you may not think to ask your doctor, along with notes on why they’re important.

I’ve never smoked cigarettes (or quit 20 years ago). How could I get C.O.P.D.?

Smoking is far and away the leading cause of C.O.P.D. in the United States and accounts for 85 percent of cases (though only about 20 percent of all smokers develop C.O.P.D. with significant symptoms); the disease can develop in people who quit years ago. Passive exposure to secondhand smoke may also play a role. In developing countries, exposure to indoor smoke from heating or cooking can cause the disease. Job exposures (such as to silica in mines) may also cause C.O.P.D. Air pollution likely accounts for only 1 percent to 2 percent of cases, although it can make the disease worse.

I’ve smoked for 25 years. Will quitting now make a difference?

Quitting smoking is the most effective thing you can do to treat C.O.P.D. Smoking inflames the lungs and airways, and while stopping may not be enough to prevent disease progression completely, it may slow it. Studies show that, overall, quitting smoking brings about a 50 percent sustained reduction in lung function decline.

What’s the best way to quit smoking?

In one study from 2001, nicotine replacements products, such as gums, sprays or a patch, were more effective than the pill buproprion (Zyban) in helping smokers with C.O.P.D. to quit. A newer smoking cessation drug, called Chantix, is also available. Counseling may also help.

Do I need a breathing test (spirometry)?

Spirometry, a relatively simple breathing test that measures how much and how quickly air moves out of the lungs, is the best way to assess lung function in patients with C.O.P.D. It is critical for making a diagnosis and assessing progression of the disease. Unfortunately, harried physicians too often skip the test, which only takes a few minutes. A recent study of 25 primary care practices found that most did not perform the test, even when they had the equipment to do so.

Should I see a lung specialist?

A lung specialist would be most likely to perform spirometry during routine visits and be familiar with medications to treat C.O.P.D. That includes preventive medicines to open the airways and quell inflammation, which should be taken daily and not just in emergencies. It’s also critical that patients know how to use inhalers and other medications properly.

How often do I need to come in for check-ups?

If you have C.O.P.D., doctors generally recommend you get spirometry at least once a year. More frequent visits may be needed to assess your response to therapy. It’s also important to see your doctor if symptoms worsen -- an increase in cough, sputum or shortness of breath beyond normal day-to-day variations.

What will happen if I catch a cold or the flu? Will it make my C.O.P.D. worse?

Respiratory ailments like colds, the flu or acute bronchitis can cause a flare-up of C.O.P.D., and patients may not return to their previous levels of lung function after the illness. That’s why doctors advise patients with C.O.P.D. to stay up-to-date on vaccinations, including an annual flu shot and a pneumonia vaccination every five or six years. It’s also important that respiratory ailments be diagnosed and treated early with antibiotics or other measures.

Can weather affect my symptoms?

Many patients’ symptoms worsen with weather changes, such as fronts coming through, more humidity or impending rain or snow. Doctors used to suggest that patients with C.O.P.D. live in a dry climate but now recognize that dry weather isn’t necessarily better for all patients.

Is diet important?

Aim to maintain a healthy weight. Some people with advanced disease lose so much weight their muscles begin to waste. Obesity, on the other hand, can worsen symptoms like shortness of breath.

What limitations will there be on my activity?

Limitations depend on how advanced C.O.P.D. is when it’s diagnosed. Unfortunately, C.O.P.D. is often diagnosed late, because people are unaware that symptoms such as a smoker’s cough or shortness of breath are problematic. Often the symptoms progress so slowly that people don’t recognize that they require treatment. If C.O.P.D. is caught relatively early, patients have fewer limitations on their activity.

Should I be engaging in special exercises?

Exercise is now one of the most important components of C.O.P.D. treatment. Unfortunately, shortness of breath drives many patients to become inactive. Your doctor or a pulmonary therapist can teach you activities to strengthen the arms or legs, as well as breathing exercises to strengthen the muscles used for breathing.

Would I benefit from pulmonary rehabilitation?

Pulmonary rehabilitation, which involves an exercise program, along with counseling and education, can ease shortness of breath and improve quality of life in patients with C.O.P.D. It’s not available in all parts of the country, however, and insurance coverage varies.

How likely is my disease to become worse?

Some people with C.O.P.D. progress rapidly; doctors aren’t sure why. Early treatment is important because it may slow the worsening of symptoms.

Is surgery an option for my C.O.P.D.?

Some patients with very advanced disease may be candidates for lung volume reduction surgery, which removes areas of lung badly damaged by emphysema. The operation helps some, but not all, patients breathe easier. The surgery is undergoing testing at various medical centers to determine who might benefit most. Some newer, minimally invasive forms of lung surgery for C.O.P.D. are also being examined in clinical trials.

What is COPD?

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a lung disease in which the lungs are damaged, making it hard to breathe. In COPD, the airways—the tubes that carry air in and out of your lungs—are partly obstructed, making it difficult to get air in and out.

Cigarette smoking is the most common cause of COPD. Most people with COPD are smokers or former smokers. Breathing in other kinds of lung irritants, like pollution, dust, or chemicals, over a long period of time may also cause or contribute to COPD.

The airways branch out like an upside-down tree, and at the end of each branch are many small, balloon-like air sacs. In healthy people, each airway is clear and open. The air sacs are small and dainty, and both the airways and air sacs are elastic and springy. When you breathe in, each air sac fills up with air like a small balloon; when you breathe out, the balloon deflates and the air goes out. In COPD, the airways and air sacs lose their shape and become floppy. Less air gets in and less air goes out because:

- The airways and air sacs lose their elasticity (like an old rubber band).

- The walls between many of the air sacs are destroyed.

- The walls of the airways become thick and inflamed (swollen).

- Cells in the airways make more mucus (sputum) than usual, which tends to clog the airways.

COPD is a major cause of death and illness, and it is the fourth leading cause of death in the United States and throughout the world.

There is no cure for COPD. The damage to your airways and lungs cannot be reversed, but there are things you can do to feel better and slow the damage.

COPD is not contagious—you cannot catch it from someone else.

How the Lungs Work

The lungs provide a very large surface area (the size of a football field) for the exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide between the body and the environment.

A slice of normal lung looks like a pink sponge filled with tiny bubbles or holes. These bubbles, surrounded by a fine network of tiny blood vessels, give the lungs a large surface to exchange oxygen (into the blood where it is carried throughout the body) and carbon dioxide (out of the blood). This process is called gas exchange. Healthy lungs do this very well.

Here is how normal breathing works:

- You breathe in air through your nose and mouth. The air travels down through your windpipe (trachea) then through large and small tubes in your lungs called bronchial tubes. The larger tubes are bronchi, and the smaller tubes are bronchioles. Sometimes the word "airways" is used to refer to the various tubes or passages that air must travel through from the nose and mouth into the lungs. The airways in your lungs look something like an upside-down tree with many branches.

- At the ends of the small bronchial tubes, there are groups of tiny air sacs called alveoli. The air sacs have very thin walls, and small blood vessels called capillaries run in the walls. Oxygen passes from the air sacs into the blood in these small blood vessels. At the same time, carbon dioxide passes from the blood into the air sacs. Carbon dioxide, a normal byproduct of the body's metabolism, must be removed.

The airways and air sacs in the lung are normally elastic—that is, they try to spring back to their original shape after being stretched or filled with air, just the way a new rubber band or balloon would. This elastic quality helps retain the normal structure of the lung and helps to move the air quickly in and out. In COPD, much of the elastic quality is gone, and the airways and air sacs no longer bounce back to their original shape. This means that the airways collapse, like a floppy hose, and the air sacs tend to stay inflated. The floppy airways obstruct the airflow out of the lungs, leading to an abnormal increase in the lungs' size. In addition, the airways may become inflamed and thickened, and mucus-producing cells produce more mucus, further contributing to the difficulty of getting air out of the lungs.

Other Names for COPD

- Chronic obstructive airway disease

- Chronic obstructive lung disease

- Emphysema

- Chronic bronchitis

In chronic bronchitis, the airways have become inflamed and thickened, and there is an increase in the number and size of mucus-producing cells. This results in excessive mucus production, which in turn contributes to cough and difficulty getting air in and out of the lungs.

Most people with COPD have both chronic bronchitis and emphysema.

What Causes COPD?

Smoking Is the Most Common Cause of COPD

Most cases of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) develop after repeatedly breathing in fumes and other things that irritate and damage the lungs and airways. Cigarette smoking is the most common irritant that causes COPD. Pipe, cigar, and other types of tobacco smoke can also cause COPD, especially if the smoke is inhaled. Breathing in other fumes and dusts over a long period of time may also cause COPD. The lungs and airways are highly sensitive to these irritants. They cause the airways to become inflamed and narrowed, and they destroy the elastic fibers that allow the lung to stretch and then return to its resting shape. This makes breathing air in and out of the lungs more difficult.

Other things that may irritate the lungs and contribute to COPD include:

- Working around certain kinds of chemicals and breathing in the fumes for many years

- Working in a dusty area over many years

- Heavy exposure to air pollution

Genes—tiny bits of information in your body cells passed on by your parents—may play a role in developing COPD. In rare cases, COPD is caused by a gene-related disorder called alpha 1 antitrypsin deficiency. Alpha 1 antitrypsin is a protein in the blood that inactivates destructive proteins. People with antitrypsin deficiency have low levels of alpha 1 antitrypsin; the imbalance of proteins leads to the destruction of the lungs and COPD. If people with this condition smoke, the disease progresses more rapidly.

Who Is At Risk for COPD?

Most people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are smokers or were smokers in the past. People with a family history of COPD are more likely to get the disease if they smoke. The chance of developing COPD is also greater in people who have spent many years in contact with lung irritants, such as:

- Air pollution

- Chemical fumes, vapors, and dusts usually linked to certain jobs

Most people with COPD are at least 40 years old or around middle age when symptoms start. It is unusual, but possible, for people younger than 40 years of age to have COPD.

What Are the Signs and Symptoms of COPD?

The signs and symptoms of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) include:

- Cough

- Sputum (mucus) production

- Shortness of breath, especially with exercise

- Wheezing (a whistling or squeaky sound when you breathe)

- Chest tightness

The severity of the symptoms depends on how much of the lung has been destroyed. If you continue to smoke, the lung destruction is faster than if you stop smoking.

How Is COPD Diagnosed?

Doctors consider a diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) if you have the typical symptoms and a history of exposure to lung irritants, especially cigarette smoking. A medical history, physical exam, and breathing tests are the most important tests to determine if you have COPD.

Your doctor will examine you and listen to your lungs. Your doctor will also ask you questions about your family and medical history and what lung irritants you may have been around for long periods of time.

Breathing Tests

Your doctor will use a breathing test called spirometryto confirm a diagnosis of COPD. This test is easy and painless and shows how well your lungs work. You breathe hard into a large hose connected to a machine called a spirometer. When you breathe out, the spirometer measures how much air your lungs can hold and how fast you can blow air out of your lungs after taking a deep breath.

Spirometry is the most sensitive and commonly used test of lung functions. It can detect COPD long before you have significant symptoms.

Based on this test, your doctor can determine if you have COPD and how severe it is. Doctors classify the severity of COPD as:

- At risk (for developing COPD). Breathing test is normal. Mild signs that include a chronic cough and sputum production.

- Mild COPD. Breathing test shows mild airflow limitation. Signs may include a chronic cough and sputum production. At this stage, you may not be aware that airflow in your lungs is reduced.

- Moderate COPD. Breathing test shows a worsening airflow limitation. Usually the signs have increased. Shortness of breath usually develops when working hard, walking fast, or doing other brisk activities. At this stage, a person usually seeks medical attention.

- Severe COPD. Breathing test shows severe airflow limitation. A person is short of breath after just a little activity. In very severe COPD, complications like respiratory failure or signs of heart failure may develop. At this stage, the quality of life is greatly impaired and the worsening symptoms may be life threatening.

- Bronchodilator reversibility testing. This test uses the spirometer and medicines called bronchodilators. Bronchodilators work by relaxing tightened muscles around the airways and opening up airways quickly to ease breathing. Your doctor will use the results of this test to see if your lung problems are being caused by another lung condition such as asthma. However, since airways in COPD may also be constricted, your doctor can use the results of this test to help set your treatment goals.

- Other pulmonary function testing. For instance, your doctor could test diffusion capacity.

- A chest x ray is a picture of your lungs. A chest x ray may be done to see if another disease, like heart failure, may be causing your symptoms.

- Arterial blood gas. This is a blood test that shows the oxygen level in your blood. It is measured in people with severe COPD to see if oxygen treatment is recommended.

Quitting smoking is the single most important thing you can do to reduce your risk of developing chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and slow the progress of the disease.

Your doctor will recommend treatments that help relieve your symptoms and help you breathe easier. However, COPD cannot be cured.

The goals of COPD treatment are to:

- Relieve your symptoms with no or minimal side effects of treatment

- Slow the progress of the disease

- Improve exercise tolerance (your ability to stay active)

- Prevent and treat complications and sudden onset of problems

- Improve your overall health

Treatment is based on whether your symptoms are mild, moderate, or severe.

Medicines and pulmonary rehabilitation (rehab) are often used to help relieve your symptoms and to help you breathe more easily and stay active.

COPD Medicines

Bronchodilators

Physicians may recommend medicines called bronchodilators that work by relaxing the muscles around your airways. This type of medicine helps to open your airways quickly and make breathing easier. Bronchodilators can be either short acting or long acting.

- Short-acting bronchodilators (albuterol/Ventolin HFA or levabuterol tartrate/Xopenex HFA) last about 4 to 6 hours and are used only when needed especially for rescue therapy.

- Long-acting bronchodilators (salmeterol/Serevent or formoterol/Foradil) last about 12 hours or more and may be prescribed for daily maintenance usage.

If you have mild COPD, your doctor may recommend that you use a short-acting bronchodilator. You then will use the inhaler only when needed.

If you have moderate or severe COPD, your doctor may recommend regular treatment with one or more inhaled bronchodilators. You may be told to use one long-acting bronchodilator. Some people may need to use a long-acting bronchodilator and a short-acting bronchodilator. This is called combination therapy.

Inhaled glucocorticosteroids (steroids)

Inhaled steroids are used for some people with moderate or severe COPD. Inhaled steroids work to reduce airway inflammation. We may recommend that you try inhaled steroids for a trial period of 6 weeks to 3 months to see if the medicine is helping with your breathing problems.

Spiriva® (tiotropium bromide inhalation powder)

This is indicated for the long-term, once-daily, maintenance treatment of bronchospasm associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), including chronic bronchitis and emphysema.

Spiriva is not indicated for the initial treatment of acute episodes of bronchospasm, i.e., rescue therapy and is contraindicated in patients with a history of hypersensitivity to atropine or its derivatives.

Flu shots

The flu (influenza) can cause serious problems in people with COPD. Flu shots can reduce the chance of getting the flu. You should get a flu shot every year.

Pneumococcal vaccine

This vaccine should be administered to those with COPD to prevent a common cause of pneumonia. Revaccination may be necessary after 5 years in those older than 65 years of age.

Pulmonary Rehabilitation

Pulmonary rehabilitation (rehab) is a coordinated program of exercise, disease management training, and counseling that can help you stay more active and carry out your day-to-day activities. What is included in your pulmonary rehab program will depend on what you and your doctor think you need. It may include exercise training, nutrition advice, education about your disease and how to manage it, and counseling. The different parts of the rehab program are managed by different types of health care professionals (doctors, nurses, physical therapists, respiratory therapists, exercise specialists, dietitians) who work together to develop a program just for you. Pulmonary rehab programs can include some or all of the following aspects.

Medical evaluation and management

To decide what you need in your pulmonary rehab program, a medical evaluation will be done. This may include getting information on your health history and what medicines you take, doing a physical exam, and learning about your symptoms. A spirometry measurement may also be done before and after you take a bronchodilator medicine.

Setting goals

You will work with your pulmonary rehab team to set goals for your program. These goals will look at the types of activities that you want to do. For example, you may want to take walks every day, do chores around the house, and visit with friends. These things will be worked on in your pulmonary rehab program.

Exercise training

Your program may include exercise training. This training includes showing you exercises to help your arms and legs get stronger. You may also learn breathing exercises that strengthen the muscles needed for breathing.

Education

Many pulmonary rehab programs have an educational component that helps you learn about your disease and symptoms, commonly used treatments, different techniques used to manage symptoms, and what you should expect from the program. The education may include meeting with (1) a dietitian to learn about your diet and healthy eating; (2) an occupational therapist to learn ways that are easier on your breathing to carry out your everyday activities; or (3) a respiratory therapist to learn about breathing techniques and how to do respiratory treatments.

Program results (outcomes)

You will talk with your pulmonary rehab team at different times during your program to go over the goals that you set and see if you are meeting them. For example, if your goal is to walk every day for 30 minutes, you will talk to members of your pulmonary team and tell them how often you are walking and for how long. The team is interested in helping you reach your goals.

Oxygen Treatment

If you have severe COPD and low levels of oxygen in your blood, you are not getting enough oxygen on you own. Your doctor may recommend oxygen therapy to help with your shortness of breath. You may need extra oxygen all the time or some of the time. For some people with severe COPD, using extra oxygen for more than 15 hours a day can help them:

- Do tasks or activities with less shortness of breath

- Protect the heart and other organs from damage

- Sleep more during the night and improve alertness during the day

- Live longer

For some people with severe COPD, surgery may be recommended. Surgery is usually done for people who have:

- Severe symptoms

- Not had improvement from taking medicines

- A very hard time breathing most of the time

- Bullectomy. In this procedure, doctors remove one or more very large bullae from the lungs of people who have emphysema. Bullae are air spaces that are formed when the walls of the air sacs break. The air spaces can become so large that they interfere with breathing.

- Lung volume reduction surgery (LVRS). In this procedure, surgeons remove sections of damaged tissue from the lungs of patients with emphysema. A major NHLBI study of LVRS recently showed that patients whose emphysema was mostly in the upper lobes of the lung and who had this surgery, along with medical treatment and pulmonary rehabilitation, were more likely to function better after 2 years than patients who received medical therapy only. They also did not have a greater chance of dying than the other patients.

A small group of these patients who also had low exercise capacity after pulmonary rehabilitation but before surgery were also more likely to function better after LVRS than similar patients who received medical treatment only.

How Can COPD Be Prevented From Progressing?

If you smoke, the most important thing you can do to stop more damage to your lungs is to quit smoking. Many hospitals have smoking cessation programs or can refer you to one.

It is also important to stay away from people who are smoking and places where you know there will be smokers.

Staying away from other lung irritants such as pollution, dust, and certain cooking or heating fumes is also important. For example, you should stay in your house when the outside air quality is poor.

Managing Complications and Preventing Sudden Onset of Problems

People with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) often have symptoms that suddenly get worse. When this happens, you have a much harder time catching your breath. You may also have chest tightness, more coughing, change in your sputum, and a fever. It is important to call your doctor if you have any of these signs or symptoms.

We will look at things that might be causing these signs and symptoms to suddenly worsen. Sometimes the signs and symptoms are caused by a lung infection. We may want you to take an antibiotic medicine that helps fight off the infection.

We may also recommend additional medicines to help with your breathing. These medicines include bronchodilators and glucocorticosteroids.

We may recommend that you spend time in the hospital if:

- You have a lot of difficulty catching your breath.

- You have a hard time talking.

- Your lips or fingernails turn blue or gray.

- You are not mentally alert.

- Your heartbeat is very fast.

- Home treatment of worsening symptoms doesn't help.

Although there is no cure for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), your symptoms can be managed, and damage to your lungs can be slowed. If you smoke, quitting is the most important thing you can do to help your lungs. Information is available on ways to help you quit smoking. You also need to try to stay away from people who are smoking or places where there is smoking.

It is important to keep the air in your home clean. Here are some things that may help you in your home:

- Keep smoke, fumes, and strong smells out of your home.

- If your home is painted or sprayed for insects, have it done when you can stay away from your home.

- Cook near an open door or window.

- If you heat with wood or kerosene, keep a door or window open.

- Keep your windows closed and stay at home when there is a lot of pollution or dust outside.

See your doctor at least two times a year, even if you are feeling fine. Make sure you bring a list of medicines you are taking to your doctor visit.

Ask your us about getting a flu shot and pneumonia vaccination.

Keep your body strong by learning breathing exercises and walking and exercising regularly.

Eat healthy foods. Ask your family to help you buy and fix healthy foods. Eat lots of fruits and vegetables. Eat protein food like meat, fish, eggs, milk, and soy.

If you have been told you that you have severe COPD, there are some things that you can do to get the most out of each breath. Make your life as easy as possible at home by:

- Asking your friends and family for help.

- Doing things slowly.

- Doing things sitting down.

- Putting things you need in one place that is easy to reach.

- Finding very simple ways to cook, clean, and do other chores. Some people use a small table or cart with wheels to move things around. Using a pole or tongs with long handles can help you reach things.

- Keeping your clothes loose.

- Wearing clothes and shoes that are easy to put on and take off.

- Asking for help moving your things around in your house so that you will not need to climb stairs as often.

- Picking a place to sit that you can enjoy and visit with others.

- Order antibiotics, which are medicines that help fight off infection

- Change the type and dosage of the bronchodilator and glucocorticosteroid medicines you have been taking

- Order oxygen or increase the amount of oxygen you are currently using

- The phone numbers for the doctor, hospital, and people who can take you to the hospital or doctor

- Directions to the hospital and doctor's office

- A list of the medicines you are taking

- You find that is hard to talk or walk.

- Your heart is beating very fast or irregularly.

- Your lips or fingernails are gray or blue.

- Your breathing is fast and hard, even when you are using your medicines.

- Smoking is the most common cause of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

- COPD is a disease that slowly worsens over time, especially if you continue to smoke.

- Breathing in other kinds of lung irritants, like pollution, dust, or chemicals, over a long period of time may also cause or contribute to COPD. Secondhand smoke and genetic disorders can also play a role in COPD.

- There is no cure for COPD (which includes emphysema and chronic bronchitis), and it is a major cause of illness and death.

- In COPD, much of the elastic quality of the airways and air sacs in the lung is gone. The airways collapse and obstruct the normal airflow. Airways may also become inflamed and thickened.

- The signs and symptoms of COPD are different for each person. Common signs are cough, sputum production, shortness of breath, wheezing, and chest tightness.

- COPD usually occurs in people who are at least 40 years old. COPD is not contagious.

- If you have COPD, you are more likely to have lung infections, which can be fatal.

- Your doctor can use a medical history, physical exam, and breathing tests, such as spirometry, to diagnose—or rule out—COPD even before you have significant symptoms.

- If the lungs are severely damaged, the heart may be affected. A person with COPD dies when the lungs and heart are unable to function and get oxygen to the body's organs and tissues, or when a complication such as a severe infection occurs.

- Treatment for COPD may help prevent complications, prolong life, and improve a person's quality of life. Quitting smoking, staying away from people who are smoking, and avoiding exposure to other lung irritants are the most important ways to reduce your risk of developing COPD or to slow the progress of the disease.

- Treatment may include medicines such as bronchodilators, steroids, flu shots, and pneumococcal vaccine to avoid or reduce further complications.

- As the symptoms of COPD get worse over time, a person may have more difficulty with walking and exercising. You should talk to your doctor about exercising and whether you would benefit from a pulmonary rehab program—a coordinated program of exercise, physical therapy, disease management training, advice on diet, and counseling.

- Oxygen treatment and surgery to remove part of a lung or even to transplant a lung may be recommended for persons with severe COPD.

- If you have a sudden worsening of signs or symptoms, it is important to contact your doctor and seek emergency treatment.

- Be prepared and have information on hand that you or others would need in a medical emergency, such as information on medicines you are taking, directions to the hospital or your doctor’s office, and people to contact if you are unable to speak or call them.

Six Killers: Lung Disease

From Smoking Boom, a Major Killer of Women

By Denise Grady : NY Times Article : November 29, 2007

For Jean Rommes, the crisis came five years ago, on a Monday morning when she had planned to go to work but wound up in the hospital, barely able to breathe. She was 59, the president of a small company in Iowa. Although she had quit smoking a decade earlier, 30 years of cigarettes had taken their toll.

After several days in the hospital, she was sent home tethered to an oxygen tank, with a raft of medicines and a warning: “If I didn’t do something, life was going to continue to be a pretty scary experience.”

Ms. Rommes has chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or C.O.P.D., a progressive illness that permanently damages the lungs and is usually caused by smoking. Once thought of as an old man’s disease, this disorder has become a major killer in women as well, the consequence of a smoking boom in the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s. The death rate in women nearly tripled from 1980 to 2000, and since 2000, more women than men have died or been hospitalized every year because of the disease.

“Women started smoking in what I call the Virginia Slims era, when they started sponsoring sporting events,” said Dr. Barry J. Make, a lung specialist at National Jewish Medical and Research Center in Denver. “It’s now just catching up to them.”

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease actually comprises two illnesses: one, emphysema, destroys air sacs deep in the lungs; the other, chronic bronchitis, causes inflammation, congestion and scarring in the airways. The disease kills 120,000 Americans a year, is the fourth leading cause of death and is expected to be third by 2020. About 12 million Americans are known to have it, including many who have long since quit smoking, and studies suggest that 12 million more cases have not been diagnosed. Half the patients are under 65. The disease has left some 900,000 working-age people too sick to work and costs $42 billion a year in medical bills and lost productivity.

“It’s the largest uncontrolled epidemic of disease in the United States today,” said Dr. James Crapo, a professor at the National Jewish Medical and Research Center.

Experts consider the statistics a national disgrace. They say chronic lung disease is misdiagnosed, neglected, improperly treated and stigmatized as self-induced, with patients made to feel they barely deserve help, because they smoked. The disease is mired in a bog of misconception and prejudice, doctors say. It is commonly mistaken for asthma, especially in women, and treated with the wrong drugs.

Although incurable, it is treatable, but many patients, and some doctors, mistakenly think little can be done for it. As a result, patients miss out on therapies that could help them feel better and possibly live longer. The therapies vary, but may include drugs, exercise programs, oxygen and lung surgery.

Incorrectly treated, many fall needlessly into a cycle of worsening illness and disability, and wind up in the emergency room over and over again with pneumonia and other exacerbations — breathing crises like the one that put Ms. Rommes in the hospital — that might have been averted.

“Patients often come to me with years of being under treated,” said Dr. Byron Thomashow, the director of the Center for Chest Disease at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia hospital.

Still others are overtreated for years with steroids like prednisone, which is meant for short-term use and if used too much can thin the bones, weaken muscles and raise the risk of cataracts.

Adequate treatment means drugs, usually inhaled, that open the airways and quell inflammation — preventive medicines that must be used daily, not just in emergencies. It is essential to quit smoking.

Patients also need antibiotics to fight lung infections, vaccines to prevent flu and pneumonia and lessons on special breathing techniques that can help them make the most of their diminished lungs. Some need oxygen, which can help them be more active and prolong life in severe cases. Many need dietary advice: obesity can worsen symptoms, but some with advanced disease lose so much weight that their muscles begin to waste. Some people with emphysema benefit from surgery to remove diseased parts of their lungs.

Above all, patients need exercise, because shortness of breath drives many to become inactive, and they become increasingly weak, homebound, disabled and depressed. Many could benefit from therapy programs called pulmonary rehabilitation, which combine exercise with education about the disease, drugs and nutrition, but the programs are not available in all parts of the country, and insurance coverage for them varies.

“I have a complicated, severe group of patients, but I will swear to you that very few wind up in hospitals,” Dr. Thomashow said. “I treat aggressively. I use the medicines, I exercise all of them. You can make a difference here. This is an example of how we’re undertreating this entire disease.”

Little-Known Epidemic

Researchers say there is so little public awareness of how common and serious C.O.P.D. is that the O might as well stand for “obscure” or “overlooked.”

The disease may not be well known, but people who have it are a familiar sight. They are the ones who cannot climb half a flight of stairs without getting winded, who have a perpetual smoker’s cough or wheeze, who need oxygen to walk down the block or push a cart through the supermarket. Some grow too weak and short of breath to leave the house. The flu or even a cold can put them in the hospital. In advanced stages, the lung disease can lead to heart failure.

“This is a disease where people eventually fade away because they can no longer cope with life,” said Grace Anne Dorney Koppel, who has chronic lung disease. (Ms. Dorney Koppel, a lawyer, is married to Ted Koppel.) “My God, if you don’t have breath, you don’t have anything.”

Most cases, about 85 percent, are caused by smoking, and symptoms usually start after age 40, in people who have smoked a pack a day for 10 years or more. In the United States, 45 million people smoke, 21 percent of adults. Only about 20 percent of smokers develop chronic lung disease.

The illness is not the same as asthma, but some patients have asthma along with their other lung problems. Most have a combination of emphysema and chronic bronchitis. In about one-sixth of cases, emphysema is the main problem. Women are far more likely than men to develop chronic bronchitis, and are less prone to emphysema. Some studies have suggested that women’s lungs are more sensitive than men’s to the toxins in smoke.

Worldwide, these lung diseases kill 2.5 million people a year. An article in September in The Lancet, a medical journal, said that “if every smoker in the world were to stop smoking today, the rates of C.O.P.D. would probably continue to increase for the next 20 years.” The reason is that although quitting slows the disease, it can develop later.

Cigarettes are the major cause worldwide, but other sources are important in developing countries, especially smoke from indoor fires that burn wood, coal, straw or dung for heating and cooking. Women and children are most likely to be exposed. Outdoor air pollution plays less of a part: it can aggravate existing disease, but is believed to cause only 1 percent of cases in rich countries and 2 percent in poorer ones. Occupational exposures in cotton mills and mines may contribute.

Researchers have differed about whether passive smoking plays a role, but a Lancet article in September predicted that in China, among the 240 million people who are now over 50, 1.9 million who never smoked will die from chronic lung disease — just from exposure to other people’s smoke.

Many patients with lung disease have other illnesses as well, like heart disease, acid reflux, hypertension, high cholesterol, sinus problems or diabetes. Compared with other smokers, those with C.O.P.D. are more likely to develop lung cancer as well. Researchers suspect that all the ailments stem partly from the same underlying condition, widespread inflammation, a reaction by the immune system that can affect blood vessels, organs and tissues all over the body.

Lung disease can creep up insidiously, because human beings have lung power to spare. Millions of airways, with enough surface area to cover a tennis court, provide so much reserve that most people would not notice it if they lost the use of a third or even half of a lung. But all that extra capacity can hide an impending disaster.

“If it comes on gradually, the body can adjust,” said Dr. Neil Schachter, a lung specialist and professor at Mount Sinai Medical Center in New York. “Some of these patients are at oxygen levels where you and I would be gasping for breath.”