- RETIREMENT ANNOUNCEMENT

- HOME PAGE

- "MYCHART" the new patient portal

- BELMONT MEDICAL ASSOCIATES

- MOUNT AUBURN HOSPITAL

- EMERGENCIES

- PRACTICE PHILOSOPHY

- MY RESUME

- TELEMEDICINE CONSULTATION

- CONTACT ME

- LAB RESULTS

- ePRESCRIPTIONS

- eREFERRALS

- RECORD RELEASE

- MEDICAL SCRIBE

- PHYSICIAN ASSISTANT (PA)

- Medicare Annual Wellness Visit

- Case management/Social work

- Quality Care Measures

- Emergency closing notice

- FEEDBACK

- Talking to your doctor

- Choosing..... and losing a doctor

- INDEX A - Z

- ALLERGIC REACTIONS

- Alternative Medicine

- Alzheimer's Disease

- Bladder Problems

- Blood disorders

- Cancer Concerns

- GENETIC TESTING FOR HEREDITARY CANCER

- Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

- Controversial Concerns

- CPR : Learn and save a life

- CRP : Inflammatory marker

- Diabetes Management

- Dizziness, Vertigo,Tinnitus and Hearing Loss

- EXERCISE

- FEMALE HEALTH

-

GASTROINTESTINAL topics

- Appendicitis

- BRAT diet

- Celiac Disease or Sprue

- Crohn's Disease

- Gastroenterologists for Colon Cancer Screening

- Colonoscopy PREP

- Constipation

- Gluten sensitivity, but not celiac disease

- Heartburn and GERD

- Hemorrhoids and Anal fissure

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- NASH : Non Alcoholic Steato Hepatitis

- FEET PROBLEMS

- HEART RELATED topics

-

INFECTIOUS DISEASES

- Antibiotic Resistance

- Cat bites >

- Clostridia difficile infection - the "antibiotic associated germ"

- CORONA VIRUS

- Dengue Fever and Chikungunya Fever

- Food borne illnesses

- Shingles Vaccine

- Hepatitis B

- Hepatitis C

- Herpes

- Influenza

- Helicobacter pylori - the "ulcer germ"

- HIV Screening

- Lyme and other tick borne diseases

- Measles

- Meningitis

- MRSA (Staph infection)

- Norovirus

- Sexually Transmitted Diseases

- Shingles (Herpes Zoster)

- Sinusitis

- West Nile Virus

- Whooping Cough (Pertussis)

- Zika virus and pregnancy

- INSURANCE related topics

- KIDNEY STONES

- LEG CRAMPS

- LIBRARY for patients

- LIFE DECISIONS

- MALE HEALTH

- Medication/Drug side effects

- MEDICAL MARIJUANA

- MENTAL HEALTH

- Miscellaneous Articles

-

NUTRITION - EXERCISE - WEIGHT

- Cholesterol : New guidelines for treatment

- Advice to lower your cholesterol

- Cholesterol : Control

- Cholesterol : Raising your HDL Level

- Exercise

- Food : Making Smart Choices

- Food : Making Poor Choices

- Food : Grape Fruit and Drug Interaction

- Food : Vitamins, Minerals and Supplements

- Omega 3 fatty acids

- Vitamin B12 deficiency

- Vitamin D

- Weight Loss

- ORTHOPEDICS

- PAIN

- PATIENTS' RIGHTS

- SKIN

- SLEEP

- SMOKING

- STROKE

- THYROID

- SUBSTANCE ABUSE

- Travel and Vaccination

- TREMOR

- Warfarin Anticoagulation

- OTHER STUFF FOLLOWS

- Fact or Opinion?

- Hippocratic Oath

- FREE ADVICE.......for what its worth!

- LAUGHTER.....is the best medicine

- Physicians Pet Peeves

- PHOTO ALBUM - its not all work!

- Cape Town, South Africa

- Tribute page

- The 100 Club

- Free Wi-Fi

ZIKA VIRUS

WARNING TO PREGNANT WOMEN

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has warned pregnant women against travel to several countries in the Caribbean and Latin America where the Zika virus is spreading. They include Bahamas, Barbados, Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Dominican Rep., Ecuador, El Salvador, French Guiana, Guadeloupe, Guatemala, Guyana, Haiti, Honduras, Martinique, Mexico, Panama, Paraguay, Saint Martin, Suriname, Venezuela, Virgin Islands, the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, as well as Samoa, in the South Pacific, and Cape Verde, off the coast of Africa. Now present in south Florida (Miami Dade County area). Infection with the virus appears to be linked to the development of microcephaly (unusually small heads and brain damage in newborns).

The latest travel advice remained a Level 2 advisory, meaning it concerns only travelers with specific risk factors — in this case, pregnancy. But Guillain-Barré syndrome, a potentially life-threatening paralysis, has been found in men and women with probable Zika infection in Brazil and French Polynesia.

The C.D.C. is helping Brazil conduct research to determine if any link exists between the Zika virus and Guillain-Barré, an autoimmune condition. Most people with the syndrome recover.

Here are some answers and advice about the outbreak.

What is the Zika virus?

A tropical infection new to the Western Hemisphere.

The Zika virus is a mosquito-transmitted infection related to dengue, yellow fever and West Nile virus. Although it was discovered in the Zika forest in Uganda in 1947 and is common in Africa and Asia, it did not begin spreading widely in the Western Hemisphere until last May, when an outbreak occurred in Brazil.

Until now, almost no one on this side of the world had been infected. Few of us have immune defenses against the virus, so it is spreading rapidly. Millions of people in tropical regions of the Americas may have had it.

How is the virus spread?

One more reason to hate mosquitoes.

Zika is spread by mosquitoes of the Aedes species, which can breed in a pool of water as small as a bottle cap and usually bite during the day. The aggressive yellow fever mosquito, Aedes aegypti, has spread most Zika cases, but that mosquito is common in the United States only in Florida, along the Gulf Coast, and in Hawaii – although it has been found as far north as Washington in hot weather.

The Asian tiger mosquito, Aedes albopictus, is also known to transmit the virus, but it is not clear how efficiently. That mosquito ranges as far north as New York and Chicago in summer.

Although the virus is normally spread by mosquitoes, there have been reports of spread through blood transfusion and through sex.

How do I know if I’ve been infected? Is there a test?

It’s often a silent infection, and hard to diagnose.

Until recently, Zika was not considered a major threat because its symptoms are relatively mild. Only one of five people infected with the virus develop symptoms, which can include fever, rash, joint pain and red eyes. Those infected usually do not have to be hospitalized.

There is no widely available test for Zika infection. Because is closely related to dengue and yellow fever, it may cross-react with antibody tests for those viruses. To detect Zika, a blood or tissue sample from the first week in the infection must be sent to an advanced laboratory so the virus can be detected through sophisticated molecular testing.

How does Zika cause brain damage in infants?

Experts are only beginning to connect the dots.

Scientists do not fully understand the connection. The possibility that the Zika virus causes microcephaly – unusually small heads and damaged brains – emerged in October, when doctors in northern Brazil noticed a surge in babies with the condition.

It is not known exactly how common microcephaly has become in that outbreak. About three million babies are born in Brazil each year. Normally, about 150 cases of microcephaly are reported, and Brazil says it is investigating more than 3,500 reported cases.

But reporting of suspected cases commonly rises during health crises.

Does it matter when in her pregnancy a woman is infected with Zika virus?

Earlier seems to be worse.

The most dangerous time is thought to be during the first trimester – when some women do not realize they are pregnant. Experts do not know how the virus enters the placenta and damages the growing brain of the fetus.

Closely related viruses, including yellow fever, dengue and West Nile, do not normally do so. Viruses from other families, including rubella (German measles) and cytomegalovirus, sometimes do.

Is there a vaccine? How should people protect themselves?

Protection is a huge challenge in infested regions.

There is no vaccine against the Zika virus. Efforts to make one have just begun, and creating and testing a vaccine normally takes years and costs hundreds of millions of dollars.

Because it is impossible to completely prevent mosquito bites, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has advised pregnant women to avoid going to regions where Zika is being transmitted, and has advised women thinking of becoming pregnant to consult doctors before going.

Travelers to these countries are advised to avoid or minimize mosquito bites by staying in screened or air-conditioned rooms or sleeping under mosquito nets, wearing insect repellent at all times and wearing long pants, long sleeves, shoes and hats.

WARNING TO PREGNANT WOMEN

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has warned pregnant women against travel to several countries in the Caribbean and Latin America where the Zika virus is spreading. They include Bahamas, Barbados, Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Dominican Rep., Ecuador, El Salvador, French Guiana, Guadeloupe, Guatemala, Guyana, Haiti, Honduras, Martinique, Mexico, Panama, Paraguay, Saint Martin, Suriname, Venezuela, Virgin Islands, the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, as well as Samoa, in the South Pacific, and Cape Verde, off the coast of Africa. Now present in south Florida (Miami Dade County area). Infection with the virus appears to be linked to the development of microcephaly (unusually small heads and brain damage in newborns).

The latest travel advice remained a Level 2 advisory, meaning it concerns only travelers with specific risk factors — in this case, pregnancy. But Guillain-Barré syndrome, a potentially life-threatening paralysis, has been found in men and women with probable Zika infection in Brazil and French Polynesia.

The C.D.C. is helping Brazil conduct research to determine if any link exists between the Zika virus and Guillain-Barré, an autoimmune condition. Most people with the syndrome recover.

Here are some answers and advice about the outbreak.

What is the Zika virus?

A tropical infection new to the Western Hemisphere.

The Zika virus is a mosquito-transmitted infection related to dengue, yellow fever and West Nile virus. Although it was discovered in the Zika forest in Uganda in 1947 and is common in Africa and Asia, it did not begin spreading widely in the Western Hemisphere until last May, when an outbreak occurred in Brazil.

Until now, almost no one on this side of the world had been infected. Few of us have immune defenses against the virus, so it is spreading rapidly. Millions of people in tropical regions of the Americas may have had it.

How is the virus spread?

One more reason to hate mosquitoes.

Zika is spread by mosquitoes of the Aedes species, which can breed in a pool of water as small as a bottle cap and usually bite during the day. The aggressive yellow fever mosquito, Aedes aegypti, has spread most Zika cases, but that mosquito is common in the United States only in Florida, along the Gulf Coast, and in Hawaii – although it has been found as far north as Washington in hot weather.

The Asian tiger mosquito, Aedes albopictus, is also known to transmit the virus, but it is not clear how efficiently. That mosquito ranges as far north as New York and Chicago in summer.

Although the virus is normally spread by mosquitoes, there have been reports of spread through blood transfusion and through sex.

How do I know if I’ve been infected? Is there a test?

It’s often a silent infection, and hard to diagnose.

Until recently, Zika was not considered a major threat because its symptoms are relatively mild. Only one of five people infected with the virus develop symptoms, which can include fever, rash, joint pain and red eyes. Those infected usually do not have to be hospitalized.

There is no widely available test for Zika infection. Because is closely related to dengue and yellow fever, it may cross-react with antibody tests for those viruses. To detect Zika, a blood or tissue sample from the first week in the infection must be sent to an advanced laboratory so the virus can be detected through sophisticated molecular testing.

How does Zika cause brain damage in infants?

Experts are only beginning to connect the dots.

Scientists do not fully understand the connection. The possibility that the Zika virus causes microcephaly – unusually small heads and damaged brains – emerged in October, when doctors in northern Brazil noticed a surge in babies with the condition.

It is not known exactly how common microcephaly has become in that outbreak. About three million babies are born in Brazil each year. Normally, about 150 cases of microcephaly are reported, and Brazil says it is investigating more than 3,500 reported cases.

But reporting of suspected cases commonly rises during health crises.

Does it matter when in her pregnancy a woman is infected with Zika virus?

Earlier seems to be worse.

The most dangerous time is thought to be during the first trimester – when some women do not realize they are pregnant. Experts do not know how the virus enters the placenta and damages the growing brain of the fetus.

Closely related viruses, including yellow fever, dengue and West Nile, do not normally do so. Viruses from other families, including rubella (German measles) and cytomegalovirus, sometimes do.

Is there a vaccine? How should people protect themselves?

Protection is a huge challenge in infested regions.

There is no vaccine against the Zika virus. Efforts to make one have just begun, and creating and testing a vaccine normally takes years and costs hundreds of millions of dollars.

Because it is impossible to completely prevent mosquito bites, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has advised pregnant women to avoid going to regions where Zika is being transmitted, and has advised women thinking of becoming pregnant to consult doctors before going.

Travelers to these countries are advised to avoid or minimize mosquito bites by staying in screened or air-conditioned rooms or sleeping under mosquito nets, wearing insect repellent at all times and wearing long pants, long sleeves, shoes and hats.

Pregnant women who feel sick and have visited countries in which the Zika virus is spreading should see a doctor soon and be tested for infection even though the tests are imperfect, federal health officials said.

That advice was at the core of interim Zika-related guidelines for pregnant women issued by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The authors are specialists in emerging diseases and reproductive health.

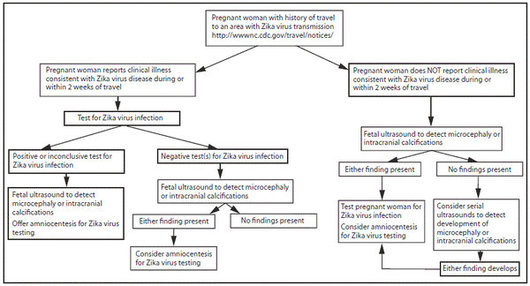

The guidelines included a “testing algorithm” to show doctors how to proceed with a worried patient who is pregnant and has recently lived in or traveled to an area where the virus is being transmitted.

Infection with the virus has been linked to brain damage and microcephaly— unusually small heads in infants.

For such a woman, the picture the guidelines presented is “pretty bleak,” said Dr. William Schaffner, the chairman of preventive medicine at Vanderbilt University.

Some of the recommended tests result in false positive outcomes, he noted, while others are not useful until late in pregnancy. Moreover, the nation’s top laboratories simply don’t yet have the capacity to test all the women who should be tested.

Pregnant women who fell ill with Zika symptoms — these include fever, rash, joint pain and red eyes — during travel or two weeks afterward should get blood tests for the virus, the guidelines say. Those with no symptoms do not need blood tests.

That may cause controversy, experts said, because 80 percent of infected people never develop symptoms, and it is not known whether an asymptomatic infection can affect a fetus.

“That had me scratching my head,” Dr. Schaffner said. “Most cases are asymptomatic, and nothing I’ve read says that women need to be symptomatic for the baby to be affected.”

Dr. Denise J. Jamieson, one of the C.D.C. authors, acknowledged that there is no way to know whether the babies of mothers who did not get noticeably ill might be harmed.

The C.D.C does not recommend blood tests for asymptomatic women, Dr. Jamieson said, partly because the country’s laboratories simply cannot do that many tests right now.

The complex tests currently can be done only by the C.D.C. and a few state laboratories, and they would be overwhelmed by testing, for example, every pregnant woman living in Puerto Rico and every pregnant woman from the rest of the country who visited Latin America or the Caribbean in the last nine months.

“These are interim guidelines, and as soon we know more about the virus, they may evolve,” Dr. Jamieson said.

Twenty countries or territories in this hemisphere have confirmed Zika transmission, according to the Pan American Health Organization. They include Barbados, Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, El Salvador, French Guiana, Guadeloupe, Guatemala, Guyana, Haiti, Honduras, Martinique, Mexico, Panama, Paraguay, Saint Martin, Suriname, Venezuela and the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico.

Zika also spreads in countries in Africa and Asia, but transmission is far less intense because the virus has been there for decades and many people have immunity. Islands in the South Pacific have experienced more recent outbreaks.

Extensive footnotes to the new guidelines note some serious drawback to the tests. For instance, blood testing for the virus itself only is possible within two weeks of the infection.

Tests for antibodies to the virus can be administered later, but may give false positives or inconclusive results if the patient has also been infected with dengue or other related viruses.

Whether a symptomatic woman’s test is positive or negative, the guidelines say, she should be offered a fetal ultrasound to look for microcephaly or calcification inside the developing skull.

Unfortunately, microcephaly is generally not detectable by ultrasound before the end of the second trimester.

Women who choose to abort a microcephalic fetus would be forced to seek a late-term abortion.

Those can be performed with little medical risk to the mother, but can be emotionally wrenching, especially if a woman has been visibly pregnant for weeks.

If microcephaly is not present, the guidelines say, the doctor and patient should consider doing a series of ultrasound scans as the pregnancy develops to watch for any appearance of microcephaly.

Women who experienced symptoms and have a positive or inconclusive Zika test should be offered both an ultrasound and amniocentesis.

During amniocentesis, a needle is inserted and some of the amniotic fluid surrounding the baby is withdrawn and tested for the virus. A positive result suggests the fetus has been infected.

Mothers whose fetuses show any signs of microcephaly or skull hardening should also be offered amniocentesis, the guidelines said. The procedure, however, is not recommended until after a fetus is 15 weeks old. It is not known how long the virus might persist in a fetus.

Dr. Schaffner predicted that the ability of state and local laboratories to do more testing would improve as the C.D.C. speeds up distribution of test kits and training, which has been done effectively in past epidemics, including Ebola.

Many ultrasounds would be done on asymptomatic women, he also said, since plenty of those machines and technicians are available and doctors can offer concerned patients little else right now.

Dr. Schaffner said that obstetricians’ offices would be filled with worried women, and that their doctors — normally not obligated to think as much about exotic foreign viruses as infectious disease specialists are — would face a steep learning curve.

“This is a virus with a strange name, an international origin and potentially horrendous consequences,” he said. “This is going to be enormously anxiety-provoking.”

CLINICAL FEATURES:

80% of infections are asymptomatic

Of those who do have symptoms they often have a mild rash, low grade fever, slight headache and a charcteristic conjunctivitis.

MANAGEMENT:

No special precautions are needed unless potential exposure to blood and semen.

Aspirin is not indicated (because infection could be Dengue and aspirin can precipitate hemorrhagic Dengue)

If a woman is infected then determine whether she is pregnant.If not pregnant she should use contraception for > 3 months (ideally 6 months).

If she is pregnant then immediately perform an ultrasound and consider amniocentesis.

Infected men should use condoms for 6 months, if their sexual partner is trying to become pregnant. If partner is pregnant then they are advised to use condoms throughout the pregnancy.

PREVENTION:

Try to avoid travel to the affected areas if try to become pregnant. This applies to both men and women.

Those already pregnant should definitely avoid these areas.

If in an area where the disease is prevalent, then try to avoid mosquito contact by staying indoors; wear clothing that covers as much as possible (light colors better than dark colors) and use a mosquito repellent eg 25% DEET; sleep under mosquito netting with an air conditioner or fan

A Guide to Help Pregnant Women Reduce Their Zika Risk

By Pam Belluck : NY Times : August. 26, 2016

Zika has a foothold in the continental United States now that mosquitoes in parts of Miami-Dade County, Fla., have infected people with the virus. Zika can cause harrowing brain damage in the developing fetus of a woman who is infected during pregnancy, so it is vital that pregnant women minimize that risk. Here’s some advice on how to do that.

If you’re pregnant and living in Miami-Dade, what should you do?

First, avoid the section of the Wynwood neighborhood and the stretch of Miami Beach where health officials say mosquitoes have infected people with the Zika virus.

Try to stay inside during the day. Going out at night is safer than during the day because the Aedes aegypti mosquitoes that can carry the Zika virus are primarily daytime denizens.

If you do go out in the daytime, cover up. Wear “long-sleeve shirts, pants, socks, maybe a scarf,” said Dr. Charles Lockwood, the dean of the medical school at the University of South Florida in Tampa. And, he added, “embed your clothing with permethrin, which you can get at a sports store.”

But don’t forget to apply bug repellent. Use ones recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Those include repellents with DEET, which has been shown to be safe in pregnancy and not to impair a baby’s development. Two other types of repellent, those with picaridin and IR3535, are also recommended; studies on animals have found they have no negative effects on fetuses.

If you want to use a lower-dose repellent, apply it more often. As Dr. Sarah G. Obican, a maternal fetal specialist, told The New York Times in April, “Using a 6 percent DEET product will last you two hours, and 20 percent one will last close to four hours.”

Should you think about going away for a while, if possible?

If you can get away, and if you think it would be too stressful to stay in Miami, then that’s certainly something to consider. Some women have decided to relocate temporarily, moving in with relatives or staying at a vacation home.

But most don’t have that option or can’t afford to leave. And there are other things to consider, like the burden on other family members or finding a doctor you like in the new location for prenatal care.

How can you rid a home of mosquitoes that carry Zika?

Remove all standing water. Aedes aegypti like to lay their eggs in stagnant water, and they need only a thimbleful left behind in a dog bowl, a puddle in a shower drain, or the drops that pool on potted plants.

These mosquitoes also lurk in dark humid places — in closets, under beds, and in other nooks and crannies. The C.D.C. recommends using indoor insect foggers or sprays to kill mosquitoes and treat the spaces where they might hide. It says, “These products work immediately, and may need to be reapplied.”

To keep mosquitoes from entering your home, close windows, use air-conditioning and make sure that screens are secure.

If your children or spouse is infected, are you at risk?

Children and spouses can be infected if they are bitten by infected mosquitoes, so they should protect themselves with repellent, too. The main risk to you would be from unprotected sex with your spouse, so practice safe sex throughout the pregnancy.

More generally, anyone who becomes infected could theoretically serve as a blood meal for a random Aedes aegypti mosquito that comes along and bites them. That mosquito could then become infected and bite a pregnant woman. That is why all people in a place like Miami-Dade should do what they can to protect themselves and prevent mosquitoes from breeding in homes and workplaces.

If you’re pregnant, is it safe to visit Miami-Dade?

It depends on whether you can take the steps needed to protect yourself from mosquitoes, and whether you feel comfortable going there.

There are reasons the C.D.C. has made a two-tiered recommendation for pregnant women: One, don’t go to the two areas in Wynwood and Miami Beach where active Zika transmission has taken place; two, consider not going to the rest of Miami-Dade County.

Dr. Anthony Fauci, the director of the National Institute of Allergies and Infectious Disease, said the recommendation was based on the assessment of the risk of getting the virus in the continental United States, which has much better mosquito control than much of the Latin American and Caribbean region where Zika has been rampant.

It’s also based on the experience with two other viruses spread by Aedes aegypti, dengue and chikungunya, he said. When those viruses have appeared in the continental United States, including in Florida, the majority of the cases were “singular,” he said, meaning that nobody else in the person’s household or workplace became infected. That is probably because the infected mosquito bit only one person before dying.

For roughly every nine individual cases, there were about two clusters, areas where two or more people became infected. That pattern seems to be playing out with the Zika virus in South Florida, experts say.

“You’re often asked why you are talking about a section of a state when you have guidelines advising people not to go to an entire country,” Dr. Fauci said. “It’s because the conditions in different countries are much different than what we’re seeing in Florida.”

So, he said, the C.D.C. decided to tell pregnant women not to go to the sites of the two Florida clusters, the areas of confirmed risk. And for the rest of Miami-Dade, “since there is some uncertainty, the decision was to at least tell the people that there’s some risk there.”

The public health authorities also want to factor in the realities of people’s lives and the difficulties that travel warnings can impose, including economic and personal hardship if they have to sacrifice jobs or family needs to leave or avoid a Zika zone.

“You have to be very careful in not seeming like you’re dictating to people what they should do with their lives,” Dr. Fauci said. “But you have to give people enough information to make decisions to protect themselves.”

It’s a balancing act — for public officials and for pregnant women.

Asked if pregnant women should travel to Miami-Dade, Scott C. Weaver, the director of the Institute for Human Infections and Immunity at the University of Texas Medical Branch, said: “I don’t think it’s a simple black-and-white thing. If someone really needs to travel there for work, something that can’t be postponed or canceled, then take extreme precautions, stay inside a hotel room, apply repellent a lot.”

But he said: “I think certainly that pregnant women who have a choice whether to travel there should be postponing their trip. Certainly to the outbreak areas, but even in the entire region of South Florida.”