- RETIREMENT ANNOUNCEMENT

- HOME PAGE

- "MYCHART" the new patient portal

- BELMONT MEDICAL ASSOCIATES

- MOUNT AUBURN HOSPITAL

- EMERGENCIES

- PRACTICE PHILOSOPHY

- MY RESUME

- TELEMEDICINE CONSULTATION

- CONTACT ME

- LAB RESULTS

- ePRESCRIPTIONS

- eREFERRALS

- RECORD RELEASE

- MEDICAL SCRIBE

- PHYSICIAN ASSISTANT (PA)

- Medicare Annual Wellness Visit

- Case management/Social work

- Quality Care Measures

- Emergency closing notice

- FEEDBACK

- Talking to your doctor

- Choosing..... and losing a doctor

- INDEX A - Z

- ALLERGIC REACTIONS

- Alternative Medicine

- Alzheimer's Disease

- Bladder Problems

- Blood disorders

- Cancer Concerns

- GENETIC TESTING FOR HEREDITARY CANCER

- Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

- Controversial Concerns

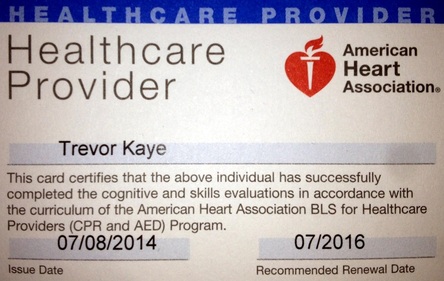

- CPR : Learn and save a life

- CRP : Inflammatory marker

- Diabetes Management

- Dizziness, Vertigo,Tinnitus and Hearing Loss

- EXERCISE

- FEMALE HEALTH

-

GASTROINTESTINAL topics

- Appendicitis

- BRAT diet

- Celiac Disease or Sprue

- Crohn's Disease

- Gastroenterologists for Colon Cancer Screening

- Colonoscopy PREP

- Constipation

- Gluten sensitivity, but not celiac disease

- Heartburn and GERD

- Hemorrhoids and Anal fissure

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- NASH : Non Alcoholic Steato Hepatitis

- FEET PROBLEMS

- HEART RELATED topics

-

INFECTIOUS DISEASES

- Antibiotic Resistance

- Cat bites >

- Clostridia difficile infection - the "antibiotic associated germ"

- CORONA VIRUS

- Dengue Fever and Chikungunya Fever

- Food borne illnesses

- Shingles Vaccine

- Hepatitis B

- Hepatitis C

- Herpes

- Influenza

- Helicobacter pylori - the "ulcer germ"

- HIV Screening

- Lyme and other tick borne diseases

- Measles

- Meningitis

- MRSA (Staph infection)

- Norovirus

- Sexually Transmitted Diseases

- Shingles (Herpes Zoster)

- Sinusitis

- West Nile Virus

- Whooping Cough (Pertussis)

- Zika virus and pregnancy

- INSURANCE related topics

- KIDNEY STONES

- LEG CRAMPS

- LIBRARY for patients

- LIFE DECISIONS

- MALE HEALTH

- Medication/Drug side effects

- MEDICAL MARIJUANA

- MENTAL HEALTH

- Miscellaneous Articles

-

NUTRITION - EXERCISE - WEIGHT

- Cholesterol : New guidelines for treatment

- Advice to lower your cholesterol

- Cholesterol : Control

- Cholesterol : Raising your HDL Level

- Exercise

- Food : Making Smart Choices

- Food : Making Poor Choices

- Food : Grape Fruit and Drug Interaction

- Food : Vitamins, Minerals and Supplements

- Omega 3 fatty acids

- Vitamin B12 deficiency

- Vitamin D

- Weight Loss

- ORTHOPEDICS

- PAIN

- PATIENTS' RIGHTS

- SKIN

- SLEEP

- SMOKING

- STROKE

- THYROID

- SUBSTANCE ABUSE

- Travel and Vaccination

- TREMOR

- Warfarin Anticoagulation

- OTHER STUFF FOLLOWS

- Fact or Opinion?

- Hippocratic Oath

- FREE ADVICE.......for what its worth!

- LAUGHTER.....is the best medicine

- Physicians Pet Peeves

- PHOTO ALBUM - its not all work!

- Cape Town, South Africa

- Tribute page

- The 100 Club

- Free Wi-Fi

SAVE A LIFE : LEARN CPR

STEP 1: CALL 911

Check the victim for unresponsiveness. If there is no response, Call 911 and return to the victim. In most locations the emergency dispatcher can assist you with CPR instructions.

STEP 2: START CHEST COMPRESSIONS

At a rate of at least 100/minute. See below

Check the victim for unresponsiveness. If there is no response, Call 911 and return to the victim. In most locations the emergency dispatcher can assist you with CPR instructions.

STEP 2: START CHEST COMPRESSIONS

At a rate of at least 100/minute. See below

NOTE

IF YOU A HESITANT OR RELUCTANT TO PERFORM THE BREATHING PART OF CPR

DON'T WORRY

AS RECENT STUDIES ARE SHOWING THAT WITH OR WITHOUT THIS COMPONENT THE RESULTS ARE ABOUT THE SAME

IF YOU A HESITANT OR RELUCTANT TO PERFORM THE BREATHING PART OF CPR

DON'T WORRY

AS RECENT STUDIES ARE SHOWING THAT WITH OR WITHOUT THIS COMPONENT THE RESULTS ARE ABOUT THE SAME

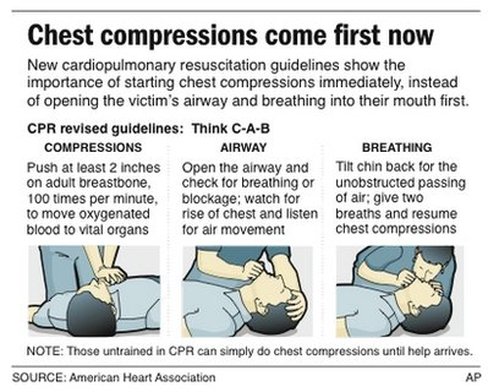

2010 AHA Guidelines:

The ABCs of CPR Rearranged to "CAB"

By Emma Hitt, PhD : October 20, 2010

Chest compressions should be the first step in addressing cardiac arrest. Therefore, the American Heart Association (AHA) now recommends that the A-B-Cs (Airway-Breathing-Compressions) of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) be changed to C-A-B (Compressions-Airway-Breathing).

The changes were documented in the 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care, published in the November 2 supplemental issue of Circulation: Journal of the American Heart Association, and represent an update to previous guidelines issued in 2005.

"The 2010 AHA Guidelines for CPR and ECC [Emergency Cardiovascular Care] are based on the most current and comprehensive review of resuscitation literature ever published," note the authors in the executive summary. The new research includes information from "356 resuscitation experts from 29 countries who reviewed, analyzed, evaluated, debated, and discussed research and hypotheses through in-person meetings, teleconferences, and online sessions ('webinars') during the 36-month period before the 2010 Consensus Conference."

According to the AHA, chest compressions should be started immediately on anyone who is unresponsive and is not breathing normally. Oxygen will be present in the lungs and bloodstream within the first few minutes, so initiating chest compressions first will facilitate distribution of that oxygen into the brain and heart sooner. Previously, starting with "A" (airway) rather than "C" (compressions) caused significant delays of approximately 30 seconds.

"For more than 40 years, CPR training has emphasized the ABCs of CPR, which instructed people to open a victim's airway by tilting their head back, pinching the nose and breathing into the victim's mouth, and only then giving chest compressions," noted Michael R. Sayre, MD, coauthor and chairman of the AHA's Emergency Cardiovascular Care Committee, in an AHA written release. "This approach was causing significant delays in starting chest compressions, which are essential for keeping oxygen-rich blood circulating through the body," he added.

The new guidelines also recommend that during CPR, rescuers increase the speed of chest compressions to a rate of at least 100 times a minute. In addition, compressions should be made more deeply into the chest, to a depth of at least 2 inches in adults and children and 1.5 inches in infants.

Persons performing CPR should also avoid leaning on the chest so that it can return to its starting position, and compression should be continued as long as possible without the use of excessive ventilation.

9-1-1 centers are now directed to deliver instructions assertively so that chest compressions can be started when cardiac arrest is suspected.

The new guidelines also recommend more strongly that dispatchers instruct untrained lay rescuers to provide Hands-Only CPR (chest compression only) for adults who are unresponsive, with no breathing or no normal breathing.

The ABCs of CPR Rearranged to "CAB"

By Emma Hitt, PhD : October 20, 2010

Chest compressions should be the first step in addressing cardiac arrest. Therefore, the American Heart Association (AHA) now recommends that the A-B-Cs (Airway-Breathing-Compressions) of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) be changed to C-A-B (Compressions-Airway-Breathing).

The changes were documented in the 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care, published in the November 2 supplemental issue of Circulation: Journal of the American Heart Association, and represent an update to previous guidelines issued in 2005.

"The 2010 AHA Guidelines for CPR and ECC [Emergency Cardiovascular Care] are based on the most current and comprehensive review of resuscitation literature ever published," note the authors in the executive summary. The new research includes information from "356 resuscitation experts from 29 countries who reviewed, analyzed, evaluated, debated, and discussed research and hypotheses through in-person meetings, teleconferences, and online sessions ('webinars') during the 36-month period before the 2010 Consensus Conference."

According to the AHA, chest compressions should be started immediately on anyone who is unresponsive and is not breathing normally. Oxygen will be present in the lungs and bloodstream within the first few minutes, so initiating chest compressions first will facilitate distribution of that oxygen into the brain and heart sooner. Previously, starting with "A" (airway) rather than "C" (compressions) caused significant delays of approximately 30 seconds.

"For more than 40 years, CPR training has emphasized the ABCs of CPR, which instructed people to open a victim's airway by tilting their head back, pinching the nose and breathing into the victim's mouth, and only then giving chest compressions," noted Michael R. Sayre, MD, coauthor and chairman of the AHA's Emergency Cardiovascular Care Committee, in an AHA written release. "This approach was causing significant delays in starting chest compressions, which are essential for keeping oxygen-rich blood circulating through the body," he added.

The new guidelines also recommend that during CPR, rescuers increase the speed of chest compressions to a rate of at least 100 times a minute. In addition, compressions should be made more deeply into the chest, to a depth of at least 2 inches in adults and children and 1.5 inches in infants.

Persons performing CPR should also avoid leaning on the chest so that it can return to its starting position, and compression should be continued as long as possible without the use of excessive ventilation.

9-1-1 centers are now directed to deliver instructions assertively so that chest compressions can be started when cardiac arrest is suspected.

The new guidelines also recommend more strongly that dispatchers instruct untrained lay rescuers to provide Hands-Only CPR (chest compression only) for adults who are unresponsive, with no breathing or no normal breathing.

How CPR Can Save a Life

By Jane E. Body : NY Times : December 23, 2013

Millions of people have been trained in CPR in recent decades, yet when people who aren’t in hospitals collapse from a sudden cardiac arrest, relatively few bystanders attempt resuscitation. Only one-fourth to one-third of those who might be helped by CPR receive it before paramedics arrive.

With so many people trained, why isn’t bystander CPR done more often?

For one thing, people forget what to do: the panic that may ensue is not conducive to accurate recall. Even those with medical training often can’t remember the steps just a few months after learning them. Rather than make a mistake, some bystanders simply do nothing beyond calling 911, even though emergency dispatchers often tell callers how to perform CPR.

Then there is the yuck factor: performing mouth-to-mouth resuscitation on a stranger. So pervasive is the feeling of reluctance that researchers decided to study whether rescue breathing is really necessary.

Two major studies, published in The New England Journal of Medicine in July 2010, clearly demonstrated that chest compressions alone were as good or even better than combining them with rescue breathing. In both studies, one conducted in Washington State and London and the other in Sweden, a slightly higher percentage of people who received only bystander chest compressions survived to be discharged from the hospital with good brain function.

When a person collapses suddenly because the heart’s electrical function goes awry, it turned out, there is often enough air in the lungs to sustain heart and brain function for a few minutes, as long as blood is pumped continuously to those vital organs. In addition, some people gasp while in cardiac arrest, which can bring more oxygen into the lungs. Indeed, the studies strongly suggested that interrupting chest compressions to administer rescue breaths actually diminishes the effectiveness of CPR in these patients.

Based in part on these findings, the American Heart Association has removed rescue breathing from bystander CPR guidelines for teenagers and adults in sudden cardiac arrest.

About 900 Americans die every day because of sudden cardiac arrest. Nearly 383,000 of such episodes occur outside hospitals each year, 88 percent of them at home. Thus, the life you save with CPR may well be a relative’s.

Sudden cardiac arrest is not the same as a heart attack. A victim of sudden cardiac arrest collapses suddenly, becomes unresponsive to gentle shaking and stops breathing normally. The arrest occurs when the heart’s electrical system malfunctions, resulting in highly irregular signals that leave the heart unable to pump blood. After just four minutes of this, the brain’s ability to recover from a lack of oxygen begins to seriously decline.

About 95 percent of people in sudden cardiac arrest die before reaching the hospital. Many of them were otherwise healthy. A victim’s chances of survival fall by 7 percent to 10 percent every minute the heart fails to pump.

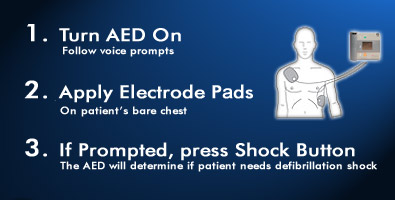

Since 2010, the heart association has advocated a simplified version of bystander CPR. When encountering a person who has collapsed and is unresponsive, the most important emergency action — after yelling for someone to call 911 — is to administer rapid, forceful chest compressions until medical help arrives or an automated external defibrillator, or A.E.D., can be used to shock the heart back into a normal rhythm.

Put one hand over the other, with fingers entwined, place them in the center of the chest between the victim’s nipples, and press hard and fast. Each compression should depress the chest by about two inches and should be repeated about 100 times a minute. If done to the beat of “Staying Alive,” the old Bee Gees song, the proper rhythm will be achieved. The chest should be allowed to rise up momentarily between compressions to allow the heart and lungs to refill.

You don’t have to take a course to learn compression-only CPR. You can prepare by watching a video by the American Heart Association. Search online for “hands-only CPR instructional video,” or check out the association’s web page on the topic. There are also free mobile training apps available for iPhone and Android phones.

Chest compressions alone should be done only for teenagers and adults in sudden cardiac arrest. Conventional CPR, with rescue breathing, is still recommended for infants and younger children. The combination should also be used for teenagers and adults in cardiac arrest who collapsed unobserved and may not have any air left in their lungs, as well as for victims of drowning, drug overdose or collapse because of a breathing problem.

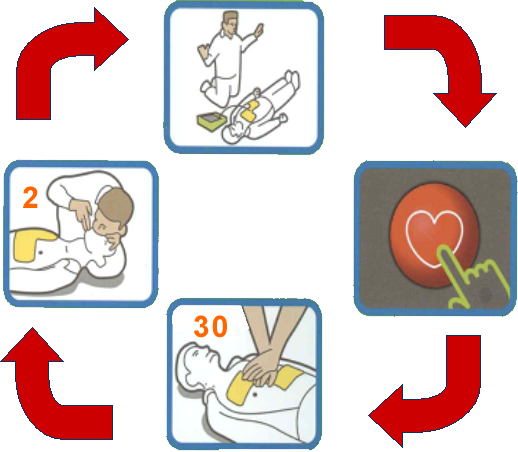

The heart association has changed the recommended protocol for conventional CPR in hopes of improving its effectiveness. The current recommendation is to start with 30 chest compressions (at a rate of 100 a minute) followed by two one-second breaths, repeating this sequence until help arrives.

When providing breaths, the victim’s head should be tilted back to open the airway. For an infant, the rescuer’s mouth should completely cover the baby’s nose and mouth. For children older than 1 and for adults, the victim’s nose should be pinched and the mouth completely covered by the mouth of the rescuer, who should observe the chest rising with each rescue breath.

By Jane E. Body : NY Times : December 23, 2013

Millions of people have been trained in CPR in recent decades, yet when people who aren’t in hospitals collapse from a sudden cardiac arrest, relatively few bystanders attempt resuscitation. Only one-fourth to one-third of those who might be helped by CPR receive it before paramedics arrive.

With so many people trained, why isn’t bystander CPR done more often?

For one thing, people forget what to do: the panic that may ensue is not conducive to accurate recall. Even those with medical training often can’t remember the steps just a few months after learning them. Rather than make a mistake, some bystanders simply do nothing beyond calling 911, even though emergency dispatchers often tell callers how to perform CPR.

Then there is the yuck factor: performing mouth-to-mouth resuscitation on a stranger. So pervasive is the feeling of reluctance that researchers decided to study whether rescue breathing is really necessary.

Two major studies, published in The New England Journal of Medicine in July 2010, clearly demonstrated that chest compressions alone were as good or even better than combining them with rescue breathing. In both studies, one conducted in Washington State and London and the other in Sweden, a slightly higher percentage of people who received only bystander chest compressions survived to be discharged from the hospital with good brain function.

When a person collapses suddenly because the heart’s electrical function goes awry, it turned out, there is often enough air in the lungs to sustain heart and brain function for a few minutes, as long as blood is pumped continuously to those vital organs. In addition, some people gasp while in cardiac arrest, which can bring more oxygen into the lungs. Indeed, the studies strongly suggested that interrupting chest compressions to administer rescue breaths actually diminishes the effectiveness of CPR in these patients.

Based in part on these findings, the American Heart Association has removed rescue breathing from bystander CPR guidelines for teenagers and adults in sudden cardiac arrest.

About 900 Americans die every day because of sudden cardiac arrest. Nearly 383,000 of such episodes occur outside hospitals each year, 88 percent of them at home. Thus, the life you save with CPR may well be a relative’s.

Sudden cardiac arrest is not the same as a heart attack. A victim of sudden cardiac arrest collapses suddenly, becomes unresponsive to gentle shaking and stops breathing normally. The arrest occurs when the heart’s electrical system malfunctions, resulting in highly irregular signals that leave the heart unable to pump blood. After just four minutes of this, the brain’s ability to recover from a lack of oxygen begins to seriously decline.

About 95 percent of people in sudden cardiac arrest die before reaching the hospital. Many of them were otherwise healthy. A victim’s chances of survival fall by 7 percent to 10 percent every minute the heart fails to pump.

Since 2010, the heart association has advocated a simplified version of bystander CPR. When encountering a person who has collapsed and is unresponsive, the most important emergency action — after yelling for someone to call 911 — is to administer rapid, forceful chest compressions until medical help arrives or an automated external defibrillator, or A.E.D., can be used to shock the heart back into a normal rhythm.

Put one hand over the other, with fingers entwined, place them in the center of the chest between the victim’s nipples, and press hard and fast. Each compression should depress the chest by about two inches and should be repeated about 100 times a minute. If done to the beat of “Staying Alive,” the old Bee Gees song, the proper rhythm will be achieved. The chest should be allowed to rise up momentarily between compressions to allow the heart and lungs to refill.

You don’t have to take a course to learn compression-only CPR. You can prepare by watching a video by the American Heart Association. Search online for “hands-only CPR instructional video,” or check out the association’s web page on the topic. There are also free mobile training apps available for iPhone and Android phones.

Chest compressions alone should be done only for teenagers and adults in sudden cardiac arrest. Conventional CPR, with rescue breathing, is still recommended for infants and younger children. The combination should also be used for teenagers and adults in cardiac arrest who collapsed unobserved and may not have any air left in their lungs, as well as for victims of drowning, drug overdose or collapse because of a breathing problem.

The heart association has changed the recommended protocol for conventional CPR in hopes of improving its effectiveness. The current recommendation is to start with 30 chest compressions (at a rate of 100 a minute) followed by two one-second breaths, repeating this sequence until help arrives.

When providing breaths, the victim’s head should be tilted back to open the airway. For an infant, the rescuer’s mouth should completely cover the baby’s nose and mouth. For children older than 1 and for adults, the victim’s nose should be pinched and the mouth completely covered by the mouth of the rescuer, who should observe the chest rising with each rescue breath.