- RETIREMENT ANNOUNCEMENT

- HOME PAGE

- "MYCHART" the new patient portal

- BELMONT MEDICAL ASSOCIATES

- MOUNT AUBURN HOSPITAL

- EMERGENCIES

- PRACTICE PHILOSOPHY

- MY RESUME

- TELEMEDICINE CONSULTATION

- CONTACT ME

- LAB RESULTS

- ePRESCRIPTIONS

- eREFERRALS

- RECORD RELEASE

- MEDICAL SCRIBE

- PHYSICIAN ASSISTANT (PA)

- Medicare Annual Wellness Visit

- Case management/Social work

- Quality Care Measures

- Emergency closing notice

- FEEDBACK

- Talking to your doctor

- Choosing..... and losing a doctor

- INDEX A - Z

- ALLERGIC REACTIONS

- Alternative Medicine

- Alzheimer's Disease

- Bladder Problems

- Blood disorders

- Cancer Concerns

- GENETIC TESTING FOR HEREDITARY CANCER

- Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

- Controversial Concerns

- CPR : Learn and save a life

- CRP : Inflammatory marker

- Diabetes Management

- Dizziness, Vertigo,Tinnitus and Hearing Loss

- EXERCISE

- FEMALE HEALTH

-

GASTROINTESTINAL topics

- Appendicitis

- BRAT diet

- Celiac Disease or Sprue

- Crohn's Disease

- Gastroenterologists for Colon Cancer Screening

- Colonoscopy PREP

- Constipation

- Gluten sensitivity, but not celiac disease

- Heartburn and GERD

- Hemorrhoids and Anal fissure

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- NASH : Non Alcoholic Steato Hepatitis

- FEET PROBLEMS

- HEART RELATED topics

-

INFECTIOUS DISEASES

- Antibiotic Resistance

- Cat bites >

- Clostridia difficile infection - the "antibiotic associated germ"

- CORONA VIRUS

- Dengue Fever and Chikungunya Fever

- Food borne illnesses

- Shingles Vaccine

- Hepatitis B

- Hepatitis C

- Herpes

- Influenza

- Helicobacter pylori - the "ulcer germ"

- HIV Screening

- Lyme and other tick borne diseases

- Measles

- Meningitis

- MRSA (Staph infection)

- Norovirus

- Sexually Transmitted Diseases

- Shingles (Herpes Zoster)

- Sinusitis

- West Nile Virus

- Whooping Cough (Pertussis)

- Zika virus and pregnancy

- INSURANCE related topics

- KIDNEY STONES

- LEG CRAMPS

- LIBRARY for patients

- LIFE DECISIONS

- MALE HEALTH

- Medication/Drug side effects

- MEDICAL MARIJUANA

- MENTAL HEALTH

- Miscellaneous Articles

-

NUTRITION - EXERCISE - WEIGHT

- Cholesterol : New guidelines for treatment

- Advice to lower your cholesterol

- Cholesterol : Control

- Cholesterol : Raising your HDL Level

- Exercise

- Food : Making Smart Choices

- Food : Making Poor Choices

- Food : Grape Fruit and Drug Interaction

- Food : Vitamins, Minerals and Supplements

- Omega 3 fatty acids

- Vitamin B12 deficiency

- Vitamin D

- Weight Loss

- ORTHOPEDICS

- PAIN

- PATIENTS' RIGHTS

- SKIN

- SLEEP

- SMOKING

- STROKE

- THYROID

- SUBSTANCE ABUSE

- Travel and Vaccination

- TREMOR

- Warfarin Anticoagulation

- OTHER STUFF FOLLOWS

- Fact or Opinion?

- Hippocratic Oath

- FREE ADVICE.......for what its worth!

- LAUGHTER.....is the best medicine

- Physicians Pet Peeves

- PHOTO ALBUM - its not all work!

- Cape Town, South Africa

- Tribute page

- The 100 Club

- Free Wi-Fi

Weight Loss

Tips for Weight Loss

Dietary guidelines

If motivation is the spark that lights the weight-loss fire, then smart planning is the timber that will keep your desire burning. Lots of folks jump into a new diet or weight-loss plan without giving it much thought. This can lead to disappointment later when results aren't as stellar as had been hoped and people don't understand what went wrong. Losing weight or maintaining a healthful weight brings the promise of feeling great, looking good and decreasing the negative impact that being overweight has on your health.

Factors that most weight-loss experts agree will help you succeed:

PREPARATION

Internal Motivation:

Write down your reasons for wanting to lose weight. An honest assessment can go a long way toward predicting whether you will succeed. Knowing why you want to lose weight can also help you focus your efforts more definitively. Play to your strongest internal motivation. In general, internal motivators (getting healthy, feeling better) lead to long-term success.

External motivators:

(fitting into new clothes in time for a friend's wedding) tend to be powerful but short-lived. Aim for something like climbing stairs without becoming winded rather than trying to fit into that old dress or suit.

Specific motivators make powerful inducements.

A man who enjoys restoring antique cars finds that because of his weight gain he can no longer slide under the cars to work on them. The desire to recapture the joy of his hobby motivates him to lose weight. A mother with a toddler at home can't easily get down on the floor to play with the baby. She makes significant changes in her life (and to her weight) based on her desire to share time with her child. A strong desire for change can lead to a very real commitment to action.

Elicit Support: You could go it alone, but support makes the job easier and more pleasant. Telling the people closest to you about your intentions announces that you're serious and committed to your new lifestyle. This doesn't have to be a media event. Just tell your family and friends that you plan to change some important aspects of your life and that you'd appreciate their support. A caveat: Don't proclaim, "I'm starting a new diet." Diets are temporary. You're making changes for the long haul. Having a support partner works for many people. Together, you can bolster one another's sagging spirits by offering encouragement. Promising to meet a partner for regularly scheduled gym time is a great way to stick to a workout routine. Other people choose to attend weight-management programs, either alone or with a friend. Putting out money for a program or health-club membership turns a wishful idea into a business transaction. "I've already paid for this, so I might as well go," is the mantra of many.

ACTION

Make Gradual Changes

Dramatic changes tend to disappear dramatically; gradual changes stay with you for a lifetime. Make a list of your long-term goals. They may include reaching and maintaining a certain weight, feeling more energetic or reclaiming a sense of control over your life. Break this list into manageable chunks. Perhaps you'll say, "Over the course of the next year, I want to lose X pounds." Divide that number by months or weeks, and then plan how you can meet that goal through decreased caloric intake and increased activity. If you've been inactive for a long time, don't start by exercising three times a week for 30 minutes per session. Ease into it. And when planning your new menu, don't eliminate all "bad" foods in one sweep. With milk, for example, you can reduce fat content in steps, becoming accustomed to the taste and consistency of each type at your own pace. Switch from whole milk to 2 percent — which actually has 36 percent of calories from fat! — then to 1-percent milk and finally to skim, which has no calories from fat.

Schedule Regular Activity:

Exercise burns calories and makes you feel better. It also may curb appetite. Make exercise an automatic part of your day and pretty soon you won't remember a time when you weren't active. On days when a full workout is impossible, you can accumulate activity by squeezing in short bouts of action throughout the day. Park your car far from a building's entrance and walk. Take a brisk stroll after lunch. Perform desk exercises while you work. Tap your foot to music. Use the stairs. These all can add up to more calories burned than are burned during a workout at the gym, and are a lot more convenient.

Eat Smaller, More Frequent Meals:

Smaller meals help stave off feelings of starvation, which can lead to binge eating. It's also an easy way to get fruits and vegetables into your diet. Keep healthful foods handy so "calorie-dispensing" vending machines or fast food joints won't tempt you. Stock staples like apples and raisins in a desk drawer, purse or locker. Baby short cut carrots and celery stalks can fill you up while providing lots of fiber. Almost any recipes you currently use can be turned into a mini meal. How small should these meals be? Aim for snack-like portions of about 100 to 150 calories. Examine typical vending machine snacks and you'll find most are well over this amount. A small package of cheese crackers with peanut butter filling has about 230 calories. By choosing fruit and vegetable snacks instead, you can easily satisfy your hunger without the extra calories. A quarter cup of raisins, for example, has about 130 calories. You can eat as often as you feel genuinely hungry. This means not eating out of habit or boredom. Drink a glass of water before you eat anything. You need water anyway, plus it helps you fill up without adding calories.

Weight Loss on a Sliding Financial Scale

By Lesley Alderman : NY Times Article : July 4, 2009

If you’re one of the millions of people who are dieting right this minute, or even thinking about it, here’s some good news: you don’t have to throw a lot of money at the problem to see results. In fact, you may not have to spend much at all.

Every year consumers spend billions of dollars on supplements, diet foods, books and meal replacements. But the truth is that success depends not so much on what diet plan you choose or what program you join.

“What matters most is your level of motivation and your willingness to change,” says Kelly D. Brownell, a psychologist and director of the Rudd Center for Food Policy and Obesity at Yale.

A study published in the Feb. 26 issue of The New England Journal of Medicine, for instance, compared four popular diets and found they all produced similar results. After two years, the dieters in each group lost an average of nine pounds. Notably, the dieters who attended more counseling sessions lost a little bit more, which may support the notion that behavior is more important than diet alone.

Motivation, though, is not always easy to come by — especially when it involves changing habits. Some people may need a little help to kick-start a weight-loss regimen, whether that means following a popular diet or enrolling in an organized program. Your goal, though, should not be short term.

“Keeping weight off permanently is a lifelong process,” says James O. Hill, a psychologist and a founder of the National Weight Control Registry (www.nwcr.ws), a database of 6,000 people who have lost weight and kept it off.

How ready are you? The more committed you are, the less you will need to spend. Try the no-money down, do-it-yourself approach first. If that doesn’t work, or you know you need more structure, move on down the list below.

$0.00 : Do It Yourself:

If you’re highly motivated but low on cash, this approach is for you. You will need to reduce the calories you consume, increase the amount you exercise and learn new eating habits.

Your primary care physician can give you basic guidelines for a healthy, low-calorie diet. You can also look at the dietary advice on the Weight-Control Information Network, a site developed by the National Institutes of Health (win.niddk.nih.gov), Mr. Brownell suggests.

Your new diet should comprise fresh food when possible, especially items high in fiber and low in fat. If you already eat well, you can just reduce your portion sizes. Weigh yourself regularly to keep track of your progress and try to get 30 to 40 minutes of exercise a day.

Hard? Yes. Possible? Of course. About half of the members of the National Weight Control Registry lost weight on their own, says Mr. Hill, who is also the director of the Center for Human Nutrition at the University of Colorado, Denver.

$ : BUY A GUIDE BOOK:

For just $20 or so, a book can give you some inspiration and wise advice. If you want a plan to follow, try “The South Beach Diet” (St. Martin’s Griffin, 2005) or “The Best Life Diet” (Simon & Schuster, 2006). Both provide realistic, healthy programs.

Another good book is “The Volumetrics Weight-Control Plan” (HarperTorch, 2002), which explains how to build a diet around foods that make you feel full.

Chronic dieters should read the new book by a former chief of the Food and Drug Administration, Dr. David Kessler, called “The End of Overeating: Taking Control of the Insatiable American Appetite“ (Rodale, 2009). In it, Dr. Kessler explains why and how we get hooked on unhealthy food.

“When I was a kid, we ate three meals a day,” he said in an interview. “Now fat, sugar and salt are on every corner 24/7. It’s become socially acceptable to eat bad food all day long.” In his book Dr. Kessler explains how our brains become wired to crave unhealthy food and provides tips to help control your impulses.

Mr. Hill’s book, “The Step Diet” (Workman, 2004), is ideal if you’re determined to keep weight off.

$$ : JOIN A GROUP:

Formal organizations like Weight Watchers and Jenny Craig can provide support, education and a healthy dose of peer pressure.

Weight Watchers is a good place to start, because it’s relatively inexpensive. You’ll pay an initial fee of $15 to $20, and then $13 to $15 for each weekly meeting. In exchange, Weight Watchers will teach you how to use its points system and provide you with that all-important weekly weigh-in.

Jenny Craig is more expensive, but may suit those who need one-on-one guidance. A yearly membership costs $399, and an additional $83 a week, on average, for Jenny’s Cuisine meals. “There’s not much evidence, though,” Mr. Brownell says, “that programs that provide meal replacements are more effective than those that don’t.”

$$$ : TRY A HOSPITAL PROGRAM:

If you need to lose a substantial amount of weight and have a condition like diabetes, you might want to invest in a hospital-sponsored weight-loss program.

“You’ll get individualized help from people who are quite knowledgeable,” Mr. Brownell said.

At Johns Hopkins Weight Management Center in Baltimore, for instance, you pay $250 for an initial four-hour assessment with a medical doctor, a registered dietitian, a psychologist and a trainer. Follow-up visits are $125 a week, but that includes food.

Most people stay with the program for several months or longer. It’s costly, but a medically monitored program may be more effective for those who are obese and who have related health conditions, says the program’s director, Dr. Lawrence J. Cheskin.

PRICELESS: KEEP IT

you become one of the lucky losers, you’ll need to fight hard to protect your losses. One way is to exercise — a lot.

“Diet is a key for losing weight,” Mr. Hill said. “But physical activity is the key for keeping it off.”

To maintain their weight, members of the National Weight Control Registry ideally exercise 30 to 60 minutes a day. Another key is to enlist the support of family and friends. If your buddies are mocking you for eating a salad while they’re inhaling beer and pizza, Mr. Hill said, it’s going to be tough to succeed.

Here is an overview of the obesity myths looked at by the researchers and what is known to be true:

MYTHS

Ideas not yet proven TRUE OR FALSE

FACTS — GOOD EVIDENCE TO SUPPORT

Adding Food and Subtracting Calories

By Tara Parker-Pope : NY Times : May 2, 2011

To lose weight, eat less, right?

Not always. New research shows that eating more of certain foods can stave off hunger pangs and control calories.

The foods, which include cayenne pepper and puréed vegetables, are natural appetite suppressants. As diet pills fall into increasing disrepute — since Abbott Laboratories withdrew its drug Meridia last year, the Food and Drug Administration has rejected three new diet drugs in recent months — these foods offer a welcome option to people struggling with their weight.

For the research, published in the journal Physiology & Behavior, scientists at Purdue studied the effect of just half a teaspoon of cayenne pepper on a group of 25 diners.

While hot red pepper has been studied before as an appetite suppressant, this study was notable in that it compared people who liked spicy food with those who did not. At various times, diners were given a bowl of tomato soup laced with a half teaspoon of pepper, plain tomato soup, or plain tomato soup with a supplement of red pepper in pill form.

The effect was greater among diners who didn’t regularly consume spicy meals. Among that group, adding red pepper to the soup was associated with eating an average of 60 fewer calories at the next meal compared with when they ate plain soup. For both groups who ate red pepper in food, the spice also appeared to increase the metabolism and cause the body to burn an extra 10 calories on its own.

“We found that when individuals consumed the red pepper in the soup rather than the supplement, they burned more calories,” said Mary-Jon Ludy, who conducted the research as a student at Purdue and will join the faculty of Bowling Green State University. “There is something special about experiencing the burn from the red pepper.”

The researchers were careful not to make too much of their findings. The effects of the cayenne pepper were real but modest, they said, adding that dieters may become desensitized to the effect of red pepper as they grow accustomed to eating spicy foods.

“We’re not at all proposing that this is any miracle cure for obesity,” said the senior author, Richard D. Mattes, a professor of food and nutrition at Purdue. “This is a small change with a small effect that is achievable by making just a small change in the diet. It goes in the right direction.”

Dieters may get better results by adding puréed vegetables to some of their favorite dishes, according to a February report in The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition.

In that study, researchers from Penn State gave 20 men and 21 women casseroles made with varying amounts of purée — a strategy popularized by the cookbook author Jessica Seinfeld, who has encouraged parents to sneak vegetables into foods like spaghetti.

But in the Penn State study, the goal wasn’t to trick people into eating vegetables. Adding the purée bulked up the dish and resulted in fewer calories per serving. (You can see two of the recipes developed by the researchers here.)

In a macaroni and cheese recipe from the researchers, for instance, the cheese sauce is made with skim milk, reduced-fat cheese and one cup each of puréed cauliflower and puréed summer squash.

The diners were fed the casseroles during different visits. They ate pretty much the same amount of food during each visit and reported no differences in flavor or enjoyment. But when they were served the casseroles made with puréed vegetables, they ate 200 to 350 fewer calories a meal.

“We’ve been able to change recipes a lot, even baked goods, and we’ve been doing it for preschool kids and adults,” said Barbara Rolls, director of Penn State’s laboratory for the study of human ingestive behavior. “We had a huge effect on energy intake. We’re adding cups of veggies to recipes and people don’t even notice.”

Other research by Dr. Rolls, author of the popular diet series “Volumetrics,” has shown that eating soup or salads before a meal can also curb the appetite and result in eating fewer calories over all.

But the stealth-vegetable approach allows diners to eat the same amount of favorite foods without ingesting as many calories.

While the best option is to purée vegetables and add them to home-cooked meals, Dr. Rolls said she hoped the food industry would respond by offering more convenient canned and frozen vegetable purées and more foods bulked up with vegetables.

She said that especially when serving the foods to young children, it’s important to continue offering whole vegetables on the side so children develop a taste for vegetables. Adding purée to reduce the calorie content works well with spicy dishes, she said.

“We offered a Tex-Mex casserole, and we could get away with adding the vegetables much more easily,” she said. “Once you put in those spicy flavors, they mask other changes in calorie density and vegetable content. The people were totally unaware we were adding lots and lots of veggies.”

Still Counting Calories?

Your Weight-Loss Plan May Be Outdated

By Jane E. Brody : NY Times : July 18, 2011

It’s no secret that Americans are fatter today than ever before, and not just those unlucky people who are genetically inclined to gain weight or have been overweight all their lives. Many who were lean as young adults have put on lots of unhealthy pounds as they pass into middle age and beyond.

It’s also no secret that the long-recommended advice to eat less and exercise more has done little to curb the inexorable rise in weight. No one likes to feel deprived or leave the table hungry, and the notion that one generally must eat less to control body weight really doesn’t cut it for the typical American.

So the newest findings on what specific foods people should eat less often — and more importantly, more often — to keep from gaining pounds as they age should be of great interest to tens of millions of Americans.

The new research, by five nutrition and public health experts at Harvard University, is by far the most detailed long-term analysis of the factors that influence weight gain, involving 120,877 well-educated men and women who were healthy and not obese at the start of the study. In addition to diet, it has important things to say about exercise, sleep, television watching, smoking and alcohol intake.

The study participants — nurses, doctors, dentists and veterinarians in the Nurses’ Health Study, Nurses’ Health Study II and the Health Professionals Follow-up Study — were followed for 12 to 20 years. Every two years, they completed very detailed questionnaires about their eating and other habits and current weight. The fascinating results were published in June in The New England Journal of Medicine.

The analysis examined how an array of factors influenced weight gain or loss during each four-year period of the study. The average participant gained 3.35 pounds every four years, for a total weight gain of 16.8 pounds in 20 years.

“This study shows that conventional wisdom — to eat everything in moderation, eat fewer calories and avoid fatty foods — isn’t the best approach,” Dr. Dariush Mozaffarian, a cardiologist and epidemiologist at the Harvard School of Public Health and lead author of the study, said in an interview. “What you eat makes quite a difference. Just counting calories won’t matter much unless you look at the kinds of calories you’re eating.”

Dr. Frank B. Hu, a nutrition expert at the Harvard School of Public Health and a co-author of the new analysis, said: “In the past, too much emphasis has been put on single factors in the diet. But looking for a magic bullet hasn’t solved the problem of obesity.”

Also untrue, Dr. Mozaffarian said, is the food industry’s claim that there’s no such thing as a bad food.

“There are good foods and bad foods, and the advice should be to eat the good foods more and the bad foods less,” he said. “The notion that it’s O.K. to eat everything in moderation is just an excuse to eat whatever you want.”

The study showed that physical activity had the expected benefits for weight control. Those who exercised less over the course of the study tended to gain weight, while those who increased their activity didn’t. Those with the greatest increase in physical activity gained 1.76 fewer pounds than the rest of the participants within each four-year period.

But the researchers found that the kinds of foods people ate had a larger effect over all than changes in physical activity.

“Both physical activity and diet are important to weight control, but if you are fairly active and ignore diet, you can still gain weight,” said Dr. Walter Willett, chairman of the nutrition department at the Harvard School of Public Health and a co-author of the study.

As Dr. Mozaffarian observed, “Physical activity in the United States is poor, but diet is even worse.”

Little Things Mean a Lot

People don’t become overweight overnight.

Rather, the pounds creep up slowly, often unnoticed, until one day nothing in the closet fits the way it used to.

Even more important than its effect on looks and wardrobe, this gradual weight gain harms health. At least six prior studies have found that rising weight increases the risk in women of heart disease, diabetes, stroke and breast cancer, and the risk in men of heart disease, diabetes and colon cancer.

The beauty of the new study is its ability to show, based on real-life experience, how small changes in eating, exercise and other habits can result in large changes in body weight over the years.

On average, study participants gained a pound a year, which added up to 20 pounds in 20 years. Some gained much more, about four pounds a year, while a few managed to stay the same or even lose weight.

Participants who were overweight at the study’s start tended to gain the most weight, which seriously raised their risk of obesity-related diseases, Dr. Hu said. “People who are already overweight have to be particularly careful about what they eat,” he said.

The foods that contributed to the greatest weight gain were not surprising. French fries led the list: Increased consumption of this food alone was linked to an average weight gain of 3.4 pounds in each four-year period. Other important contributors were potato chips (1.7 pounds), sugar-sweetened drinks (1 pound), red meats and processed meats (0.95 and 0.93 pound, respectively), other forms of potatoes (0.57 pound), sweets and desserts (0.41 pound), refined grains (0.39 pound), other fried foods (0.32 pound), 100-percent fruit juice (0.31 pound) and butter (0.3 pound).

Also not too surprising were most of the foods that resulted in weight loss or no gain when consumed in greater amounts during the study: fruits, vegetables and whole grains. Compared with those who gained the most weight, participants in the Nurses’ Health Study who lost weight consumed 3.1 more servings of vegetables each day.

But contrary to what many people believe, an increased intake of dairy products, whether low-fat (milk) or full-fat (milk and cheese), had a neutral effect on weight.

And despite conventional advice to eat less fat, weight loss was greatest among people who ate more yogurt and nuts, including peanut butter, over each four-year period.

Nuts are high in vegetable fat, and previous small studies have shown that eating peanut butter can help people lose weight and keep it off, probably because it slows the return of hunger.

That yogurt, among all foods, was most strongly linked to weight loss was the study’s most surprising dietary finding, the researchers said. Participants who ate more yogurt lost an average of 0.82 pound every four years.

Yogurt contains healthful bacteria that in animal studies increase production of intestinal hormones that enhance satiety and decrease hunger, Dr. Hu said. The bacteria may also raise the body’s metabolic rate, making weight control easier.

But, consistent with the new study’s findings, metabolism takes a hit from refined carbohydrates — sugars and starches stripped of their fiber, like white flour. When Dr. David Ludwig of Children’s Hospital Boston compared the effects of refined carbohydrates with the effects of whole grains in both animals and people, he found that metabolism, which determines how many calories are used at rest, slowed with the consumption of refined grains but stayed the same after consumption of whole grains.

Other Influences

As has been suggested by previous smaller studies, how long people slept each night influenced their weight changes. In general, people who slept less than six hours or more than eight hours a night tended to gain the most. Among possible explanations are effects of short nights on satiety hormones, as well as an opportunity to eat more while awake, Dr. Hu said.

He was not surprised by the finding that the more television people watched, the more weight they gained, most likely because they are influenced by a barrage of food ads and snack in front of the TV.

Alcohol intake had an interesting relationship to weight changes. No significant effect was found among those who increased their intake to one glass of wine a day, but increases in other forms of alcohol were likely to bring added pounds.

As expected, changes in smoking habits also influenced weight changes. Compared with people who never smoked, those who had quit smoking within the previous four years gained an average of 5.17 pounds. Subsequent weight gain was minimal — 0.14 pound for each four-year period.

Those who continued smoking lost 0.7 pound in each four-year period, which the researchers surmised may have resulted from undiagnosed underlying disease, especially since those who took up smoking experienced no change in weight.

Seduced by Snacks? No, Not You

By Kim Severson : NY Times Article Oct 11, 200

People almost always think they are too smart for Prof. Brian Wansink’s quirky experiments in the psychology of overindulgence.

When it comes to the slippery issues of snacking and portion control, no one thinks he or she is the schmo who digs deep into the snack bowl without thinking, or orders dessert just because a restaurant plays a certain kind of music.

“To a person, people will swear they aren’t influenced by the size of a package or how much variety there is on a buffet or the fancy name on a can of beans, but they are,” Dr. Wansink said. “Every time.”

He has the data to prove it. Dr. Wansink, who holds a doctorate in marketing from Stanford University and directs the Cornell University Food and Brand Lab, probably knows more about why we put things in our mouths than anybody else. His experiments examine the cues that make us eat the way we do. The size of an ice cream scoop, the way something is packaged and whom we sit next to all influence how much we eat. His research doesn’t pave a clear path out of the obesity epidemic, but it does show the significant effect one’s eating environment has on slow and steady weight gain.

In an eight-seat lab designed to look like a cozy kitchen, Dr. Wansink offers free lunches in exchange for hard data. He opened the lab at Cornell in April, after he moved it from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, where he spent eight years conducting experiments in cafeterias, grocery stores and movie theaters. Dr. Wansink presents his work to dieticians, food executives and medical professionals. They use it to get people to eat differently.

His research on how package size accelerates consumption led, in a roundabout way, to the popular 100-calorie bags of versions of Wheat Thins and Oreos, which are promoted for weight management. Although food companies have long used packaging and marketing techniques to get people to buy more food, Dr. Wansink predicts companies will increasingly use some of his research to help people eat less or eat better, even if it means not selling as much food. He reasons that companies will make up the difference by charging more for new packaging that might slow down consumption or that put seemingly healthful twists on existing brands. And they get to wear a halo for appearing to do their part to prevent obesity.

To his mind, the 65 percent of Americans who are overweight or obese got that way, in part, because they didn’t realize how much they were eating.

“We don’t have any idea what the normal amount to eat is, so we look around for clues or signals,” he said. “When all you see is that big portions of food cost less than small ones, it can be confusing.”

Although people think they make 15 food decisions a day on average, his research shows the number is well over 200. Some are obvious, some are subtle. The bigger the plate, the larger the spoon, the deeper the bag, the more we eat. But sometimes we decide how much to eat based on how much the person next to us is eating, sometimes moderating our intake by more than 20 percent up or down to match our dining companion.

Much of his work is outlined in the book “Mindless Eating: Why We Eat More Than We Think” (Bantam), which will be published on Tuesday. The book is his fourth over all, but his first directed at a general audience. It is peppered with his goofy, appealing Midwestern humor and practical diet tips. But the most fascinating material is directly from his studies on university campuses and in test kitchens for institutions like the United States Army.

An appalling example of our mindless approach to eating involved an experiment with tubs of five-day-old popcorn. Moviegoers in a Chicago suburb were given free stale popcorn, some in medium-size buckets, some in large buckets. What was left in the buckets was weighed at the end of the movie. The people with larger buckets ate 53 percent more than people with smaller buckets. And people didn’t eat the popcorn because they liked it, he said. They were driven by hidden persuaders: the distraction of the movie, the sound of other people eating popcorn and the Pavlovian popcorn trigger that is activated when we step into a movie theater.

Dr. Wansink is particularly proud of his bottomless soup bowl, which he and some undergraduates devised with insulated tubing, plastic dinnerware and a pot of hot tomato soup rigged to keep the bowl about half full. The idea was to test which would make people stop eating: visual cues, or a feeling of fullness.

People using normal soup bowls ate about nine ounces. The typical bottomless soup bowl diner ate 15 ounces. Some of those ate more than a quart, and didn’t stop until the 20-minute experiment was over. When asked to estimate how many calories they had consumed, both groups thought they had eaten about the same amount, and 113 fewer calories on average than they actually had.

Last week in his lab seven people were finishing lunch while watching a big-screen TV. Cartoons on the TV served as a distraction so participants would not be influenced by what and how much those nearby ate.

Because he does not take money from food companies and is a newcomer at the university, the lab runs on the cheap. The menus, like the one on this day, are often built from Beefaroni, applesauce, M&M’s and Chex Mix: simple, inexpensive food that subjects are familiar with and that can be easily manipulated.

He prefers to experiment on graduate students or office workers, whom he sometimes lures with the promise of a drawing for an iPod. “It’s easy to find undergraduates to participate, but with the guys nothing makes sense because they all eat like animals,” he said.

On this day he is testing how much people eat depending on whether they have exercised. Over the past several weeks they have sent subjects, some who have exercised and some who have not, through an unlimited buffet line. By measuring the difference between how much and what people eat depending on whether they have exercised, Dr. Wansink hopes to prove that even moderate exercise makes us think we are entitled to many more calories than we actually burned.

“Geez Louise, you can’t believe how much people eat to overcompensate,” he said.

Those kinds of things — intuitive bits we know about food but think we are either immune to or don’t think about — are the spine of “Mindless Eating.” In it he outlines an eating plan based on simple awareness. Employ a few tricks and you can take in 100 to 300 fewer calories a day. At the end of a year you could be 10 to 30 pounds lighter.

For example, sit next to the person you think will be the slowest eater when you go to a restaurant, and be the last one to start eating. Plate high-calorie foods in the kitchen but serve vegetables family style. Never eat directly from a package. Wrap tempting food in foil so you don’t see it. At a buffet put only two items on your plate at a time.

His dieting methods aren’t as fast as the Atkins plan or even Weight Watchers, and have little to do with matters that consume nutrition researchers or even culinarians. Dr. Wansink is not that guy. Although he has studied to be a sommelier and keeps a mental list of his 100 best meals, he drinks vats of Diet Coke and will inhale a box of Burger King Cini-mini rolls with no apologies. He doesn’t think that his work will solve the obesity problem, but it’s a start.

“It’s like a big pyramid,” he said. “The people at 30,000 feet can look down and say we need a wholesale change in our food system, in school lunches, in the way we farm.” At the bottom of the pyramid, he said, are the nutritionists and the diet fanatics who think the problem will be solved by examining every nutrient and calorie.

Dr. Wansink does his research for the person in the middle, the guy on the sofa who can appreciate a good meal, whether it is from Le Bernardin or Le Burger King.

“Will being more mindful about how we eat make everyone 100 pounds lighter next year?” he said. “No, but it might make them 10 pounds lighter.”

And the best part, he promises, is that you won’t even notice.

Weight-Loss Drugs: Hoopla and Hype

By Jane E. Brody : April 24, 2007 :Personal Health : NY Times article

“Lose 8 to 10 pounds per week, easily ... and you won’t gain the weight back afterward.”

“Lose up to 2 pounds daily without diet or exercise!”

“You could lose up to 10 lbs. this weekend!”

“Clinically proven to give you a better body without spending countless hours dieting or working out.”

“Lose 10 lbs. and unwanted inches in 48 hours. Guaranteed!”

Do these promises sound too good to be true? Well, they are. They are among hundreds of advertising claims and testimonials touted by sellers of over-the-counter weight-loss remedies. They appear in leading magazines and newspapers, on television infomercials and the Web. And millions of people succumb to the pie-in-the-sky promises every day, throwing away good money and, sometimes, their good health along with it.

More than $1.3 billion a year is spent on dietary supplements for weight loss, most of which have had little or no scientifically acceptable testing for effectiveness and safety, especially when used for months. More than 20 percent of women and nearly 10 percent of men have used nonprescription weight-loss supplements, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says.

“Over-the-counter dietary supplements to treat obesity appeal to many patients who desire a magic bullet for weight loss,” Dr. Robert B. Saper and colleagues at the Harvard Medical School wrote in the journal American Family Physician in 2004. Those desperately seeking to lose unwanted pounds can choose among more than 50 individual dietary supplements and more than 125 combination products, none of which meets medically acceptable criteria for recommended use, the experts wrote.

In a telephone survey last year among 1,444 people trying to lose weight, by the Center for Survey Research and Analysis at the University of Connecticut, more than 60 percent mistakenly thought that all such supplements had been tested and proved safe and effective; 54 percent thought that the Food and Drug Administration approved the remedies. In fact, not one dietary supplement for weight loss has that kind of approval, although one licensed prescription drug, orlistat, has conditional approval for over-the-counter sale under the brand name Alli.

Reasons for Skepticism

Before spending another cent on yet another nonprescription weight-loss remedy, ask yourself: “If there really was a miracle drug out there, wouldn’t it drive out the competition? And wouldn’t everyone know about it?” You shouldn’t have to go online or ask a store clerk to find out.

If you wonder how we got into this mess of unsubstantiated claims, look no further than the United States Congress, which in 1994 passed the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act. That law permitted proliferation of supplements derived from natural products without first having to submit clinical evidence of their safety and effectiveness to the food and drug agency. That led to the weight-loss products derived from herbal or other botanical ingredients like aloe, ephedra, fiber and green tea; minerals like chromium and pyruvates; amino acids; enzymes; and tissues from organs or glands.

Millions of gullible people seem to believe that “if it’s natural, it’s got to be good.” Judging from the growing supplement sales, few people learned from the fiasco with ephedra, an admittedly effective weight-loss supplement that the F.D.A. banned in 2004 after it was linked to 10 deaths and 13 instances of permanent disability among 87 reports of serious adverse effects in less than two years.

Now products labeled ephedra-free, bitter orange among them, contain related chemicals that, like ephedra, may also raise blood pressure and disturb heart rhythms, possibly leading to heart attacks, strokes and death. The Mayo Clinic has warned that “people with existing , high blood pressure or other cardiovascular problems should avoid bitter orange.” Note, however, that 9 of the 23 crippling and fatal effects of ephedra occurred in people with no cardiovascular risk factors.

There is no way to know whether a dietary supplement off the shelf is safe or even pure. Until and unless a disaster like ephedra comes to federal attention, the industry is essentially self-regulated. Even the Federal Trade Commission, which can prosecute for false advertising, has been unable to keep up with the proliferation of products and undocumented claims.

Dr. Saper, among others, has examined popular supplements. A combined analysis of 11 trials of the soluble fiber guar gum showed no benefit. For chromium and ginseng, he found no scientifically structured trials that showed a difference in weight loss between the supplement and a placebo. And chronic use of chromium may cause kidney and muscle damage.

Supplements with HCA, from the tropical fruit mangosteen, reported to interfere with fat synthesis and speed fat breakdown, showed contradictory results in different human tests. CLA, a trans fatty acid that reduced fat deposition in mice, produced no change in body fat in a 12-week trial of 60 patients, but caused gastrointestinal distress and may raise cholesterol and worsen insulin resistance.

Chitosan seemed safe in short-term studies but “is likely ineffective for weight loss,” Dr. Saper wrote, based on five clinical studies. It can cause constipation, bloating and other gastrointestinal symptoms, the Mayo Clinic reported.

One substance, pyruvate, showed a small benefit over a placebo, about two and a half pounds in six weeks. It is frightfully expensive and takes a week or two before results are seen.

Green tea extract, said to speed metabolism and suppress appetite, is supported by limited evidence of effectiveness and can cause vomiting, bloating, indigestion and diarrhea, as well as jitteriness and palpitations from its caffeine.

In addition to possible risks associated with single-drug supplements, many products combine several ingredients that could interact to add hazards. Some ingredients in weight-loss supplements can interact with prescription and over-the-counter remedies, possibly resulting in toxic effects.

Hoodia, a supplement derived from a South African cactus, may indeed suppress appetite. But the real thing is very hard to obtain, and most of the products sold in stores and on the Web contain little or none of the effective extract.

The list could go on and on, but I think you get the point. There is no quick fix for weight loss using over-the-counter diet pills.

The F.D.A. Weighs In

Several prescription drugs have received F.D.A. approval. Orlistat, sold as Xenical, reduces the absorption of fat from foods. It can cause gastrointestinal distress and disrupt absorption of fat-soluble vitamins.

Sibutramine, sold as Meridia, revs up metabolism and energy levels and creates a feeling of fullness. Common side effects include dry mouth, constipation and insomnia. Meridia should not be used by people with cardiac risk factors and those who use bronchodilators, take decongestants or use M.A.O. inhibitors or S.S.R.I.’s for depression.

A number of products called sympathomimetics are approved for short-term use. All can raise blood pressure. They include phentermine, sold as Lonamin, Oby-Cap, Adipex and Fastin; mazindol, Mazanor and Sanorex; benzphetamine, Didrex; diethylpropion, Tenuate; and phendimetrazine, Adipost, Bontril, Melfiat, Plegine, Prelu-2 and Statobex. Any may help a dieter start, but because of side effects, long-term use is generally not recommended.

How Does Your Waistline Matter? Let Us Count The Ways.

Gina Kolata : NY Times article : May 1, 2007

At age 39, with diabetes and high blood pressure in her family, Linda M. was starting to worry about her weight and its health consequences. She was 5 feet 6 inches tall and weighed 170 pounds, which placed her in the overweight category, according to the standard definition. Although she was not officially obese, she said, “I realized I was not at my ideal weight.”

But Linda was in for a surprise during an appointment last fall with Dr. Judith Korner, an obesity specialist at Columbia University. Instead of weighing her, Dr. Korner whipped out a tape measure and measured her waist.

It was 35 inches, putting her in a danger zone, Dr. Korner explained. An overweight woman with a waist 35 inches or larger, or an overweight man with at least a 40-inch waist, is at increased risk for diabetes and heart disease.

“That was an education,” said Linda M., who did not want her last name revealed because of her weight. “I did not realize that my waist determined my future risk.”

Obesity specialists differ on what measurements are best.

Linda’s body mass index, or B.M.I., for example, was 27.4, far from the obesity category, which starts at 30. She would have to weigh 185 pounds to have a B.M.I. that high. (For comparison, a man who is six feet tall and weighs 221 pounds is considered obese.)

If a doctor were to use B.M.I. exclusively to evaluate Linda, the conclusion would be that her weight was not a serious health risk. She had only one risk factor for heart disease — a high level of triglycerides — and the guidelines for B.M.I. say that overweight people need two factors, like high triglycerides and a high cholesterol or blood pressure levels, to be considered at serious risk.

B.M.I. has limitations. Muscular men might have high B.M.I.’s, which make them seem fatter than they are. Old people often have deceptively low B.M.I.’s because they have lost so much muscle in the aging process.

In Linda M.’s case, adding her waist measurement to her B.M.I. indicates a high health risk, according to guidelines published by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. For Dr. Korner, the test is useful in assessing if people like Linda M. — overweight but in a gray zone — face a true health risk? If her waist had been less than 35 inches, Dr. Korner would have been less concerned.

Dr. Ned Calonge, chairman of the United States Preventive Services Task Force, said the panel preferred B.M.I. measurements to determine whether people are fat enough to place their health at risk. For most adults, he explained, B.M.I. “is more feasible or has better validity than other measures.”

But, Dr. Calonge added, it is not enough to simply diagnose someone as obese. The goal should be better health.

And the problem with testing for obesity, using B.M.I. or anything else, is that the sort of counseling most patients get from their doctors has not been shown to improve health, Dr. Calonge said.

“You now have a, quote, diagnosis,” Dr. Calonge said. And there is at least fair evidence from research that intense and expensive counseling about diet and exercise can help people lose weight and improve conditions that place them at risk for heart disease. But, he added, “it is uncertain whether less intense interventions have any impact at all.”

For Madelyn Fernstrom, the director of the Health System Weight Management Center at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, the goal of a medical exam is not to document how fat someone is but to rule out rare metabolic conditions that might be causing the weight problem. An exam also helps to determine whether there are associated medical conditions that should be treated, like diabetes or high cholesterol or blood pressure.

As for Linda M., waist measurement made the difference.

“After that, I got myself in gear,” she said. “I tried to eat less sugar and healthier snacks; I was more conscious of what I was selecting.”

She lost 20 pounds and a couple of inches from her waist. Her triglycerides are lower, yet still a bit high. But, she says, as she sees it, with a smaller waist, “I’m out of the danger zone.”

Skipping Cereal and Eggs, and Packing on Pounds

By Nicholas Bakalar : New York Times Article : March 25, 2008

Researchers have found evidence that Mom was right: breakfast may really be the most important meal of all. A new study reports that the more often adolescents eat breakfast, the less likely they are to be overweight.

The researchers examined the eating and exercise habits of 1,007 boys and 1,215 girls, with an average age of 15 at the start of the five-year study — a racially and economically diverse sample from public schools in the Minneapolis-St. Paul area.

The authors found a direct relationship between eating breakfast and body mass index; the more often an adolescent had breakfast, the lower the B.M.I. And whether they looked at the data at a given point or analyzed changes over time, that relationship persisted.

Why eating breakfast should lead to fewer unwanted pounds is unclear, but the study found that breakfast eaters consumed greater amounts of carbohydrates and fiber, got fewer calories from fat and exercised more. Consumption of fiber-rich foods may improve glucose and insulin levels, making people feel satisfied and less likely to eat more later in the day.

“Food consumption at breakfast does seem to influence activity,” said Donna Spruijt-Metz, an assistant professor of preventive medicine at the University of Southern California, who was not involved in the study. “Maybe kids eating breakfast get less refined foods and more that contain fiber. The influence of that on metabolism and behavior is something we’re still trying to sort out in my lab.”

For the study, which appears in the March issue of Pediatrics, the researchers recorded food intake using a well-established food frequency questionnaire and added specific questions about how often the teenagers ate breakfast.

They also included questions to determine the behavioral and social forces that might affect eating. For example, they asked whether the teenagers were concerned about their weight, whether they skipped meals to lose weight, whether they had ever been teased about their weight and how often they had dieted during the last year. They were also asked how much exercise they were getting.

About half the teenagers ate breakfast intermittently, but girls were more likely to skip breakfast consistently and boys more likely to eat it every day. Girls who consistently ate breakfast had an overall diet higher in cholesterol, fiber and total calories than those who skipped the meal; the boys who were consistent consumed more calories, more carbohydrates and fiber, and less saturated fat than their breakfast-skipping peers.

At the start of the study, consistent breakfast eaters had an average body mass index of 21.7, intermittent eaters 22.5, and those who never had breakfast 23.4. Over the next five years, B.M.I. increased in exactly the same pattern. The relationship persisted even after controlling for age, sex, race, socioeconomic status, smoking and concerns about diet and weight.

The authors acknowledge that the study depends on self-reports of weight and eating habits, which are not always reliable, and that even though they controlled for many variables, the study was observational, showing only an association between breakfast eating habits and body mass, not a causal relationship.

Still, Mark A. Pereira, a co-author of the study and an associate professor of epidemiology at the University of Minnesota, said that eating a healthy breakfast would “promote healthy eating throughout the day and might help to prevent situations where you’re grabbing fast food or vending machine food.”

Dr. Pereira added that parents could begin to set a good example by sitting down to breakfast themselves. “The whole family structure is involved here,” he said.

Don't waste time

Seize the moment

Be more attentive about the whole eating experience; don't eat when you are driving or at the computer, When we're distracted or hurried the food (and calories) we eat tend not to register well in our brains. A brief premeal meditation to get centered before eating so you can more easily derive pleasure from your food, give the meal your full attention, and notice

when you've had enough. Make the first bites count:

The maximum food enjoyment comes in the initial bites. After a few bites, taste buds start to lose their sensitivity to the chemicals in food that make it taste good. Satisfying your taste buds by really savoring those first few bites may help you stop eating when you're physically comfortable.

Keep up appearances:

Using a smaller plate and paying attention to the presentation of a meal can increase your awareness of the food in front of you and help you stop eating when you are comfortable. The brain looks at the plate and decides if the portion is adequate. It takes some time, but the smaller the plate, the smaller the portion.

Choose satisfying foods:

Steer away from foods that give you a lot of calories for very little volume, such as milk shakes, cheese, and chocolate. The higher the fiber, protein, and/or water content of a food or meal, the more likely it is to be satisfying in your stomach without going overboard on calories.

Eat slowly:

This isn't a new concept; remember all those familiar dieting tips like "sip water between bites" and "chew thoroughly before swallowing"? These were all aimed at slowing us down when we eat. It takes 12 or more minutes for food satisfaction signals to reach the brain of a thin person, but 20 or more minutes for an obese person. Eating slowly ensures that these important messages have time to reach the brain. ·

More advice about portion control

According to experts, we have become so accustomed to oversized portions of food and extra-large serving dishes that we can no longer tell how much we are overeating. We may have more success at reducing our excessive portions by reducing the size of our food packages and serving pieces than by trying to figure out a healthy portion size. That’s essentially the conclusion Cornell University professor Brian Wansink reaches in a recent analysis published in the Journal of the American Dietetic Association on the problem of Americans’ extra-large portions.

Research from Cornell University and Penn State has repeatedly shown that the larger the amount of food we are faced with—whether on our plate or in serving bowls—the more we will eat. We might not eat everything, but we still eat more than if we started with less. This has been demonstrated in single meals, such as comparing the amount eaten of different size sub sandwiches, and in totals over a period of several days.

For many people, eating more when presented with large amounts of food may be tied to the “Clean Plate Club” phenomenon; we have been taught to view not eating all we are given as wasteful. However, researchers suggest that we may often be unable to even recognize extra-large portions. Studies show that when an equal amount of food is presented on a relatively large and small plate, we see the large plate as having less food than the smaller plate, which seems more full.

Studies also show that we tend to eat in “units.” If we buy a package of six cookies or crackers, we usually eat them all rather than leaving part of a package. If a “unit” or package of candy, French fries or soft drinks gets larger, we are more likely to eat the whole container anyway.

And food units in the United States—packages in stores and portions in restaurants—have grown dramatically in the last 20 years. For example, a bottle of soda 20 years ago was 6.5 ounces and had 85 calories; today’s soda comes in 20 ounce bottles that can contain about 250 calories. Along with calorie consumption, extra large portions can significantly increase the amount of fat and sodium we get.

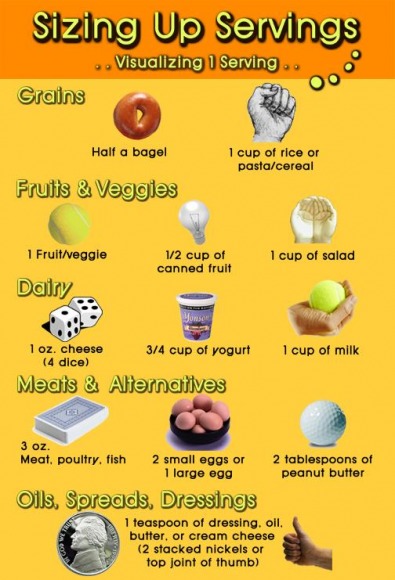

Portion Size Management - See Chart At The Bottom Of This Page

One way to improve your portion size management is to learn to better judge the amount of food in front of you. Studies have shown that if people practice measuring out different portion sizes, their accuracy can improve.

The American Institute for Cancer Research and the United States Department of Agriculture have both developed educational materials to help people learn to recognize serving sizes by comparing food amounts to common objects. For example, three ounces of meat, poultry or fish look like a deck of cards or a checkbook. A half-cup of pasta or rice looks like a tennis ball or a cupped handful.

Because of how our perception of portion size changes depending on the size and shape of the container, Wansink argues that we should pay more attention to our packages, plates and serving bowls. Market research shows that single serving packages are booming in popularity, which may be one step in this direction.

Look around your kitchen at the different size plates, bowls and glasses you have available. Instead of serving ice cream in two- or three-cup cereal bowls, make half- or one-cup custard cups the official ice cream bowl. With 200 calories per cup in even many healthful cereal choices, our tendency to simply fill a bowl and then eat it all could turn that bowl of cereal into a higher-calorie breakfast than you realize if you use large bowls.

You don’t have to get rid of those big bowls; large portion sizes are one way to increase the amount of nutrients we get. If you want people to eat more salad, they will do so automatically with bigger salad bowls.

Finally, Wansink’s research shows that the more food we have on hand, the more we will eat. So ignore the “common sense” of grocery store marketing urging you to buy two packages of cookies or chips for the price of one; you may just eat twice as much. If you find it’s easier or less expensive to buy large quantities of snack foods (such as nuts or trail mix), you can separate the food into several healthful portions, or take some out and tuck the big package out of sight.

Putting an End to Mindless Munching

WSJ Article : May 13, 2008

First, ask yourself how hungry you are, on a scale of 1 (ravenous) to 7 (stuffed).

Next, take time to appreciate the food on your plate. Notice the colors and textures.

Take a bite. Slowly experience the tastes on your tongue. Put down your fork and savor.

"Most people don't think about what they're eating -- they're focusing on the next bite," says Sasha Loring, a psychotherapist at Duke Integrative Medicine, part of Duke University Health System here. "I've worked with lots of obese people -- you'd think they'd enjoy food. But a lot of them say they haven't really tasted what they've been shoveling down for years."

Over lunch, Ms. Loring is teaching me how to eat mindfully -- paying attention to what you eat and stopping just before you're full, ideally about 5½ on that 7-point scale. Many past diet plans have stressed not overeating. What's different about mindful eating is the paradoxical concept that eating just a few mouthfuls, and savoring the experience, can be far more satisfying than eating an entire cake mindlessly.

ENJOYING YOUR FOOD

• Assess how hungry you are.

• Eat slowly; savor your food.

• Put your fork down and breathe between bites.

• Notice taste satiety.

• Check back on your hunger level.

• Stop when you start to feel full.

Source: Duke Integrative Medicine

RESOURCES

For more information on mindful eating, see these Web sites:

• www.emindful.com1 -- online mindfulness training courses

• www.tcme.org2 -- for clinicians interested in understanding mindful eating

• www.mindfuleating.org3 -- an educational site for consumers

• www.dukeintegrativemedicine.org4 -- offers a variety of conventional and complementary/alternative medicine strategies

And these books:

• "Mindless Eating" by Brian Wansink

• "Eating Mindfully" by Susan Albers

• "The Zen of Eating" by Ronna Kabatznick

It sounds so simple, but it takes discipline and practice. It's a far cry from the mindless way many of us eat while walking, working or watching TV, stopping only when the plate is clean or the show is over.

It's also a mind-blowing experience: I'm full and completely satisfied after three mindful bites.

The approach, which has roots in Buddhism, is being studied at several academic medical centers and the National Institutes of Health as a way to combat eating disorders. In a randomized controlled trial at Duke and Indiana State University, binge eaters who participated in a nine-week mindful-eating program went from binging an average of four times a week to once, and reduced their levels of insulin resistance, a precursor to diabetes. More NIH-funded trials are under way to study whether mindful eating is effective for weight loss, and for helping people who have lost weight keep it off.

One key aspect is to approach food nonjudgmentally. Many people bring a host of negative emotions to the table -- from guilt about blowing a diet to childhood fears of deprivation or wastefulness. "I joke with my clients that if I could put a microphone in their heads and broadcast what they're saying to themselves when they eat, the FCC would have to bleep it out," says Megrette Fletcher, executive director of the Center for Mindful Eating, a Web-based forum for health-care professionals.

Using food as a reward or as solace also interferes with eating mindfully; if you're eating to satisfy emotional hunger, it's hard to ever feel full. "Ask yourself, what do you really need and what else can you do it fulfill it?" says Ms. Loring.

FORUM

Chronic dieters in particular have trouble recognizing their internal cues, says Jean Kristeller, a psychologist at Indiana State, who pioneered mindful eating in the 1990s. "Diets set up rules around food and disconnect people even further from their own experiences of hunger and satiety and fullness," she says.

Mindful eaters learn to assess taste satiety. A hunger for something sweet or sour or salty can often be satisfied with a small morsel. In one exercise, Ms. Kristeller has clients mindfully eat a single raisin -- noticing their thoughts and emotions, as well as the taste and texture. "It sounds somewhat silly," she explains, "but it can also be very profound."

Mindful eating also means learning to ignore urges to snack that aren't connected to hunger. And it's critical to leave food on your plate once you are full; pack it to go, if possible.

In contrast to other diet programs, the researchers involved with mindful eating avoid making weight-loss claims; that's still being investigated. But some practitioners say it's life-changing.

"I don't think about food anymore. It's totally out of my mind," says Mary Ann Power, age 50, of Pittsboro, N.C., a lifelong dieter who thinks she's lost eight or 10 pounds in two weeks since learning the practice at Duke. "I think you could put a piece of chocolate cake in front of my nose right now, and it wouldn't tempt me. Before, I could eat three pieces."

One mindful meal at Duke made a big impression on me -- I was satisfied with minimal meals for days afterward. But it's hard to sustain. I find myself eating mindlessly again in front of the TV, or at the computer.

"Try to eat one meal or one snack mindfully every day," advises Jeffrey Greeson, a psychologist with the Duke program. "Even eating just the first few bites mindfully can help break the cycle of wolfing it down without paying any attention."

....and now that we have made you totally crazy and guilty about losing weight, there may be some advantage to being a little overweight

WSJ Article : November 6, 2007

Being 25 pounds overweight doesn't appear to raise your risk of dying from cancer or heart disease, says a new government study that seems to vindicate Grandma's claim that a few extra pounds won't kill you.

Released just a few weeks before Thanksgiving, the findings might comfort some who can't seem to lose those last 15 pounds. And they hearten proponents of a theory that it's possible to be "fit and fat."

The news isn't all good: Overweight people do have a higher chance of dying from diabetes and kidney disease. And people who are obese -- generally those more than 30 pounds overweight for their height -- have a higher risk of death from a variety of ills, including some cancers and heart disease.

However, having a little extra weight actually seemed to help people survive some illnesses -- results that baffled several leading health researchers.

"This is a very puzzling disconnect," said JoAnn Manson, chief of preventive medicine at Harvard's Brigham and Women's Hospital.

It was the second study by the same government scientists who two years ago first suggested that deaths from being too fat were overstated. The new report further analyzed the same data, this time looking at specific causes of death along with new mortality figures from 2004 for 2.3 million U.S. adults.

"Excess weight does not uniformly increase the risk of mortality from any and every cause, but only from certain causes," said the study's lead author Katherine Flegal, of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The study, which appears in Wednesday's Journal of the American Medical Association, analyzed the body-mass index of people who died from various diseases.

In many cases, the risks of death were substantial for obese people -- those with a body-mass index, or BMI, of at least 30.

Specifically, obesity raised the risk of death from heart disease, diabetes and kidney disease, and several cancers previously linked with excess weight, including breast, colon and pancreatic cancer. But being merely overweight -- having a BMI between 25 and 30 -- did not increase the risk of dying from heart disease or any kind of cancer.

Also surprising was that overweight people were up to about 40% less likely than normal-weight people to die from several other causes including emphysema, pneumonia, injuries and various infections. The age group that seemed to benefit most from a little extra padding were people aged 25 to 59; older overweight people had reduced risks for these diseases, too.

Why extra fat isn't always deadly and might even help people survive some illnesses is unclear and in fact disputed by many health experts.

But University of South Carolina obesity researcher Steven Blair, who says people can be fat and fit, is a believer. He called the report a careful and plausible analysis, and said Americans have been whipped into a "near hysteria" by hype over the nation's obesity epidemic.

While the epidemic is real, the number of deaths attributed to it and to being overweight has been exaggerated, Mr. Blair said.

People should focus instead on healthful eating and exercise, and stop obsessing about carrying a few extra pounds or becoming supermodel thin, Mr. Blair said. He says his hefty grandmother used to justify her extra padding, saying, "'That way I have protection in case I get sick.' Maybe there is something to that."

A little extra weight might provide "additional nutritional reserves" that could help people battle certain diseases, Ms. Flegal said.

Robert Eckel, a spokesman for the American Heart Association, argued that the results may be misleading. For example, diabetes and heart disease often occur together and both often afflict overweight people. So when diabetes is listed as a cause of death, heart disease could have contributed, he said.

Dr. Eckel also said the study results might reflect aggressive efforts to treat high blood pressure and cholesterol or other conditions that can lead to fatal heart attacks. Those conditions often occur in overweight people and can be costly and debilitating even if they aren't always deadly, he said.

Obesity researcher Barry Popkin of the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill, agreed, noting that the study "is about death. This is not about health and sickness." It doesn't address whether cancer and heart disease occur more often in overweight people -- something that has been suggested by other research.

Michael Thun of the American Cancer Society noted that staying slim tops a recent list of recommendations for preventing cancer in a report from the World Cancer Research Fund and American Institute for Cancer Research. The report was based on a review of more than 7,000 studies. The CDC report "definitely won't be the last word," Dr. Thun said.

Dr. Manson, the Harvard researcher, cautioned that extra pounds can lead to obesity so people shouldn't be complacent about being overweight.

Causes of Death Are Linked to a Person’s Weight

By Gina Kolata : NY Times Article : November 8, 2007

About two years ago, a group of federal researchers reported that overweight people have a lower death rate than people who are normal weight, underweight or obese. Now, investigating further, they found out which diseases are more likely to lead to death in each weight group.

Linking, for the first time, causes of death to specific weights, they report that overweight people have a lower death rate because they are much less likely to die from a grab bag of diseases that includes Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s, infections and lung disease. And that lower risk is not counteracted by increased risks of dying from any other disease, including cancer, diabetes or heart disease.

As a consequence, the group from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Cancer Institute reports, there were more than 100,000 fewer deaths among the overweight in 2004, the most recent year for which data were available, than would have expected if those people had been of normal weight.

Their paper is published today in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

The researchers also confirmed that obese people and people whose weights are below normal have higher death rates than people of normal weight. But, when they asked why, they found that the reasons were different for the different weight categories.

Some who studied the relation between weight and health said the nation might want to reconsider what are ideal weights.

“If we use the criteria of mortality, then the term ‘overweight’ is a misnomer,” said Daniel McGee, professor of statistics at Florida State University.

“I believe the data,” said Dr. Elizabeth Barrett-Connor, a professor of family and preventive medicine at the University of California, San Diego. A body mass index of 25 to 30, the so-called overweight range, “may be optimal,” she said.

Others said there were plenty of reasons that being overweight was not desirable.

“Health extends far beyond mortality rates,” said Dr. JoAnn Manson, chief of preventive medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

Dr. Manson added that other studies, including ones at Harvard, found that being obese or overweight increased a person’s risk for any of a number of diseases, including diabetes, heart disease and several forms of cancer. And, she added, excess weight makes it more difficult to move about and impairs the quality of life.

“That’s the big picture in terms of health outcomes,” Dr. Manson said. “That’s what the public needs to look at.”

Researchers generally divide weight into four categories — normal, underweight, overweight and obese — based on the body mass index, which is a measure of body fat based on height and weight. A woman who is 5 foot 4, for instance, would be considered at normal weight at 130, underweight at 107 pounds, overweight at 150 pounds and obese at 180.

In this study, those with normal weight were considered the baseline and others were compared to them.

The federal researchers, led by Katherine Flegal, of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, said the big picture they found was surprisingly complex. The higher death rate in obese people, as might be expected, was almost entirely driven by a higher death rate from heart disease.

But, contrary to expectations, the obese did not have an increased risk of dying from cancer. They were slightly more likely than people of normal weights to die of a handful of cancers that are thought to be related to excess weight — cancers of the colon, breast, esophagus, uterus, ovary, kidney and pancreas. Yet they had a lower risk of dying from other cancers, including lung cancer. In the end, the increases and decreases in cancer risks balanced out.

As for diabetes, it showed up in the death rates only when the researchers grouped diabetes and kidney disease as one category. Diabetes can cause kidney disease, they note. But, the researchers point out, the number of diabetes deaths may be too low because many people with diabetes die from heart disease, and often the cause of death is listed as a heart attack.

The diverse collection of diseases other than cancer, heart disease and diabetes, which show up in the analyses of the underweight and the overweight, have gone relatively unscrutinized among epidemiologists, noted Dr. Mitchell Gail, a cancer institute scientist and an author of the paper. But, Dr. Gail added, “these are not a negligible source of mortality.”

The new study began several years ago when the investigators used national data to look at death risks according to body weight. They concluded that, compared with people of normal weight, the overweight had a decreased death risk and the underweight and obese had increased risk.

That led them to ask if being fat or thin affects a person’s life span, what diseases, exactly, are those individuals at risk for, or protected from?

The research involved analyzing data from three large national surveys, the National Health and Nutrition surveys, which are administered by the National Center for Health Statistics. Their participants are a nationally representative group of Americans who are weighed and measured, assuring that heights and weights are accurate, and followed until death. The investigators determined the causes of death by asking what was recorded on death certificates.

The researchers caution that a study like theirs cannot speak to cause and effect. They do not yet know, precisely, what it is about being underweight, for instance, that increases the death rate from everything except heart disease and cancer. Researchers tried to rule out those who were thin, because they might have been already sick. They also ruled out smokers, and the results did not change.

Dr. Gail, though, had some advice, which, he said, is his personal opinion as a physician and researcher: “If you are in the pink and feeling well and getting a good amount of exercise and if your doctor is very happy with your lab values and other test results, then I am not sure there is any urgency to change your weight.”

Putting Very Little Weight in Calorie Counting Methods

By Gina Kolata : NY Times Article : December 20, 2007

The Spinning class at our local gym was winding down. People were wiping off their bikes, gathering their towels and water bottles, and walking out the door when a woman shouted to the instructor, “How many calories did we burn?”

“About 900,” the instructor replied.

My husband and I rolled our eyes. We looked around the room. Most people had hardly broken a sweat. I did a quick calculation in my head.

We were cycling for 45 minutes. Suppose someone was running and that the rule of thumb, 100 calories a mile, was correct.

To burn 900 calories, we would have had to work as hard as someone who ran a five-minute mile for the entire distance of nine miles.

Exercise physiologists say there is little in the world of exercise as wildly exaggerated as people’s estimates of the number of calories they burn.

Despite the displays on machines at gyms, with their precise-looking calorie counts, and despite the official-looking published charts of exercise and calories, it can be all but impossible to accurately estimate of the number of calories you burn.

You can use your heart rate to gauge your effort, and from that you can plan routines that are as challenging as you want. But, researchers say, heart rate does not translate easily into calories. And you may be in for a rude surprise if you try to count the calories you think you used during exercise and then reward yourself with extra food.

One reason for the calorie-count skepticism is that two individuals of the same age, gender, height, weight and even the same level of fitness can burn a different amount of calories at the same level of exertion.

Claude Bouchard, an obesity and exercise researcher who directs the Pennington Biomedical Research Center in Baton Rouge, La., found that if, for example, the average number of calories burned with an exercise is 100, individuals will burn anywhere from 70 to 130 calories.