- RETIREMENT ANNOUNCEMENT

- HOME PAGE

- "MYCHART" the new patient portal

- BELMONT MEDICAL ASSOCIATES

- MOUNT AUBURN HOSPITAL

- EMERGENCIES

- PRACTICE PHILOSOPHY

- MY RESUME

- TELEMEDICINE CONSULTATION

- CONTACT ME

- LAB RESULTS

- ePRESCRIPTIONS

- eREFERRALS

- RECORD RELEASE

- MEDICAL SCRIBE

- PHYSICIAN ASSISTANT (PA)

- Medicare Annual Wellness Visit

- Case management/Social work

- Quality Care Measures

- Emergency closing notice

- FEEDBACK

- Talking to your doctor

- Choosing..... and losing a doctor

- INDEX A - Z

- ALLERGIC REACTIONS

- Alternative Medicine

- Alzheimer's Disease

- Bladder Problems

- Blood disorders

- Cancer Concerns

- GENETIC TESTING FOR HEREDITARY CANCER

- Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

- Controversial Concerns

- CPR : Learn and save a life

- CRP : Inflammatory marker

- Diabetes Management

- Dizziness, Vertigo,Tinnitus and Hearing Loss

- EXERCISE

- FEMALE HEALTH

-

GASTROINTESTINAL topics

- Appendicitis

- BRAT diet

- Celiac Disease or Sprue

- Crohn's Disease

- Gastroenterologists for Colon Cancer Screening

- Colonoscopy PREP

- Constipation

- Gluten sensitivity, but not celiac disease

- Heartburn and GERD

- Hemorrhoids and Anal fissure

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- NASH : Non Alcoholic Steato Hepatitis

- FEET PROBLEMS

- HEART RELATED topics

-

INFECTIOUS DISEASES

- Antibiotic Resistance

- Cat bites >

- Clostridia difficile infection - the "antibiotic associated germ"

- CORONA VIRUS

- Dengue Fever and Chikungunya Fever

- Food borne illnesses

- Shingles Vaccine

- Hepatitis B

- Hepatitis C

- Herpes

- Influenza

- Helicobacter pylori - the "ulcer germ"

- HIV Screening

- Lyme and other tick borne diseases

- Measles

- Meningitis

- MRSA (Staph infection)

- Norovirus

- Sexually Transmitted Diseases

- Shingles (Herpes Zoster)

- Sinusitis

- West Nile Virus

- Whooping Cough (Pertussis)

- Zika virus and pregnancy

- INSURANCE related topics

- KIDNEY STONES

- LEG CRAMPS

- LIBRARY for patients

- LIFE DECISIONS

- MALE HEALTH

- Medication/Drug side effects

- MEDICAL MARIJUANA

- MENTAL HEALTH

- Miscellaneous Articles

-

NUTRITION - EXERCISE - WEIGHT

- Cholesterol : New guidelines for treatment

- Advice to lower your cholesterol

- Cholesterol : Control

- Cholesterol : Raising your HDL Level

- Exercise

- Food : Making Smart Choices

- Food : Making Poor Choices

- Food : Grape Fruit and Drug Interaction

- Food : Vitamins, Minerals and Supplements

- Omega 3 fatty acids

- Vitamin B12 deficiency

- Vitamin D

- Weight Loss

- ORTHOPEDICS

- PAIN

- PATIENTS' RIGHTS

- SKIN

- SLEEP

- SMOKING

- STROKE

- THYROID

- SUBSTANCE ABUSE

- Travel and Vaccination

- TREMOR

- Warfarin Anticoagulation

- OTHER STUFF FOLLOWS

- Fact or Opinion?

- Hippocratic Oath

- FREE ADVICE.......for what its worth!

- LAUGHTER.....is the best medicine

- Physicians Pet Peeves

- PHOTO ALBUM - its not all work!

- Cape Town, South Africa

- Tribute page

- The 100 Club

- Free Wi-Fi

Foot Problems

Think of Your Poor Feet

By Laurie Tarkan : NY Times Article : June 19, 2008

In Brief:

Huge numbers of people develop foot pain in their 60s, but it can start as early as the 20s and 30s.

Excessive weight, diabetes and circulation problems can contribute to foot pain.

Proper footwear and regular exercise can play a crucial role in preventing foot problems.

The average person walks the equivalent of three times around the Earth in a lifetime. That is enormous wear and tear on the 26 bones, 33 joints and more than 100 tendons, ligaments and muscles that make up the foot.

In a recent survey for the American Podiatric Medical Association, 53 percent of respondents reported foot pain so severe that it hampered their daily function. On average, people develop pain in their 60s, but it can start as early as the 20s and 30s. Yet, except for women who get regular pedicures, most people don't take much care of their feet.

"A lot of people think foot pain is part of the aging process and accept it, and function and walk with pain," said Dr. Andrew Shapiro, a podiatrist in Valley Stream, N.Y. Though some foot problems are inevitable, their progress can be slowed.

The most common foot conditions that occur with age are arthritic joints, thinning of the fat pads cushioning the soles, plantar fasciitis (inflammation of the fibrous tissue along the sole), bunions (enlargement of the joint at the base of the big toe), poor circulation and fungal nails.

The following questions will help you assess whether you should take more preventive action as you age: Are you overweight?

The force on your feet is about 120 percent of your weight. "Obesity puts a great amount of stress on all the supporting structures of the foot," said Dr. Bart Gastwirth, a podiatrist at the University of Chicago. It can lead to plantar fasciitis and heel pain and can worsen hammertoes and bunions. It's also a risk factor for diabetes, leading to the next question.

Are you diabetic?

Being farthest from the heart, the feet can be the first part of the body to manifest complications like poor circulation and loss of feeling, both of which can lead to poor wound healing and amputation. Diabetics should have their feet examined annually by a doctor and avoid shoes that cause abrasions and pressure.

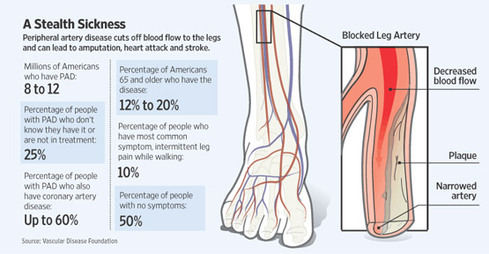

Do you have poor circulation?

If you suffer from peripheral artery disease — a narrowing of veins in the legs — your feet are more susceptible to problems, said Dr. Ross E. Taubman, president of the American Podiatric Medical Association. Smoking also contributes to poor circulation.

Do your parents complain about their feet?

Family history is probably your biggest clue to potential problems.

Do you have flat feet or high arches?

Either puts feet at risk. A flat foot is squishy, causing muscles and tendons to stretch and weaken, leading to tendinitis and arthritis. A high arch is rigid and has little shock absorption, putting more pressure on the ball and heel of the foot, as well as on the knees, hips and back. Shoes or orthotics that support the arch and heel can help flat feet. People with high arches should look for roomy shoes and softer padding to absorb the shock. Isometric exercises also strengthen muscles supporting the foot.

Are you double-jointed?

If you can bend back your thumb to touch your lower arm, the ligaments in your feet are probably stretchy, too, Dr. Gastwirth said. That makes the muscles supporting the foot work harder and can lead to injuries. Wear supportive shoes.

Do your shoes fit?

In the podiatric association's survey, more than 34 percent of men said they could not remember the last time their feet were measured. Twenty percent of women said that once a week they wore shoes that hurt, and 8 percent wore painful shoes daily. Feet flatten and lengthen with age, so if you are clinging to the shoe size you wore at age 21, get your feet measured (especially mothers — pregnancy expands feet).

Do you wear high heels?

"The high heel concentrates the force on the heel and the forefoot," Dr. Gastwirth said. Heels contribute to hammertoes, neuromas (pinched nerves near the ball of the foot), bunions and "pump bump" (a painful bump on the back of the heel), as well as toenail problems. Most of the time, wear heels that are less than two and a half inches high.

Do your feet ever see the light of day?

Fungus thrives in a warm, moist environment. Choose moisture-wicking socks (not cotton), use antifungal powders and air out your toes at home.

Have you seen a podiatrist?

Minor adjustments, using drugstore foot pads or prescription orthotics, can relieve the pressure on sensitive areas, rebalance the foot and slow the progress of a condition.

Do you walk?

Putting more mileage on your feet is the best way to exercise the muscles and keep them healthy.

Sprains : Overview

A sprain is an injury to the ligaments around a joint. Ligaments are strong, flexible fibers that hold bones together. When a ligament is stretched too far or tears, the joint will become painful and swell.

Alternative Names : Joint sprain

Causes Sprains are caused when a joint is forced to move into an unnatural position. For example, "twisting" one's ankle causes a sprain to the ligaments around the ankle.

Symptoms

- Joint pain or muscle pain

- Swelling

- Joint stiffness

- Discoloration of the skin, especially bruising

- Apply ice immediately to help reduce swelling. Wrap the ice in cloth -- DO NOT place ice directly on the skin.

- Try NOT to move the affected area. To help you do this, bandage the affected area firmly, but not tightly. ACE bandages work well. Use a splint if necessary.

- Keep the swollen joint elevated above the level of the heart, even while sleeping.

- Rest the affected joint for several days.

Keep pressure off the injured area until the pain subsides (usually 7-10 days for mild sprains and 3-5 weeks for severe sprains). You may require crutches when walking. Rehabilitation to regain the motion and strength of the joint should begin within one week.

Call Immediately for Emergency Medical Assistance if Go to the hospital right away or call 911 if:

- You suspect a broken bone

- The joint appears to be deformed

- You have a serious injury or the pain is severe

- There is an audible popping sound and immediate difficulty using the joint

- Swelling does not go down within 2 days

- You have symptoms of infection -- the area becomes redder, more painful, or warm, or you have a fever over 100°F

- The pain does not go away after several weeks

- Wear protective footwear for activities that place stress on your ankle and other joints.

- Make sure that shoes fit your feet properly.

- Avoid high-heeled shoes.

- Always warm-up and stretch prior to exercise and sports.

- Avoid sports and activities for which you are not conditioned.

Q: What is the biggest foot and ankle problem that specialists treat?

A: One of the biggest problems we see is ankle instability coming from ankle sprains. About half of all joint injuries occur to the ankle, and approximately 85 percent of these are sprains, which are ruptures of the ankle joint’s surrounding ligaments.

Approximately 46 percent of all athletes have had a significant ankle sprain; some have even suffered multiple sprains. Sprained ankles are the single biggest cause for time lost due to injury in the National Football League. Ankle sprains are a real problem not just for the elite athlete, but for the weekend warrior, too. In the United States, there are 10,000 admissions to the emergency department every day for ankle sprains.

Q: Is it possible to ignore an ankle sprain and get on with your life?

A: The traditional treatment for the sprained ankle, our mothers used to tell us, was that if you didn’t break your ankle, then stop the whining, put some ice on it, and you will be fine. We are now learning that that may not have been the best strategy because it actually leads to more problems.

However, when most ankle sprains are addressed early on with rest, ice and compression and follow-up physical therapy, you should never be bothered again. To ignore a sprain, you do so at your peril. Return to exercise without proper rehabilitation can increase your chances for reinjury, perhaps more severely. You can also develop an osteochondral lesion, which is a crack in the cartilage or bone that will require surgical attention.

Q: What steps do you recommend for healing an ankle sprain?

A: Most ankle sprains result from forced and excessive inversion, an inward rolling of the ankles. These sprains frequently occur when stepping on another player’s foot or when a runner steps into a rut. The ligaments on the outside portion of the ankle, and the muscles on the lateral portion of the leg that are responsible for limiting ankle inversion, are typically injured. The high incidence of recurrent sprains that we see is primarily due to the failure to successfully complete an adequate three-phase treatment program.

Phase 1: Immediate early treatment goals are minimizing soft tissue swelling and regaining range of motion. This is done by applying a compression bandage around the ankle and foot. Elevate the ankle higher than the heart. Apply an ice pack for 20 minutes to control internal bleeding and fluid accumulation. Apply ice every two hours while awake for the next 48 hours. When the foot is elevated, perform range-of-motion exercises by keeping your heel still and tracing the alphabet in capital letters with your big toe.

Phase 2: After 48 hours, the goals are to eliminate all swelling and pain, regain full range of motion and restrengthen the muscles that stabilize the ankle. Remove the compression wrap and immerse your ankle comfortably in a container of hot water (104 degrees Fahrenheit). Perform the air alphabet. Next, place your foot into a container filled with crushed ice and cold water. While keeping the heel of the injured foot on the bottom of the container, lift and rotate the foot up and out until it makes contact with the side of the container. Hold that position for eight seconds, relax for two seconds, and repeat.

Start the hot-water exercises and perform them in descending periods of five, four, three, two and one minute. Alternate each of them with one-minute intervals of cold bath exercises. Continue using the compression wrap until the ankle has no swelling and is pain free.

Phase 3: The goal is to restore range of motion and regain strength to the muscles stabilizing the ankle. You want to be able to stand and balance on the injured foot for 20 seconds without wobbling. Heel raises are excellent. Stand on the injured foot and slowly raise your heel off the ground, then slowly lower it. Repeat 10 times for three sets. Once you can stand and balance on the ball of the injured foot for 20 seconds and have regained full range of motion, begin a jogging program on a flat, smooth surface for up to 20 minutes. When finished, ice the ankle for 20 minutes. When you are able to run on a field or court in a large figure eight pattern at quarter speed, advance to half speed and then full speed. At that point, you can return to full activities.

Q: What if an ankle is still sore in the weeks after the original injury?

A: Our message for the weekend warrior is not to try to run through the pain of an ankle sprain. If you still have chronic pain after three months of your sprain and physical therapy, you may have a chronic tear of the ankle ligaments or an osteochondral defect, or crack in the cartilage or bone that may lead to a cyst on the ankle. This will be uncovered easily with an M.R.I., not typically an X-ray. Once a lesion is there, surgery is necessary. If it’s a small lesion, then microdrilling or micropicking of the surface of the bone helps stimulate the formation of fibrocartilage to replace the lost cartilage.

If the lesion is large, it has to be replaced with something akin to the cartilage that was there. We replace “like with like” by going to the knee and taking out a plug of thin articular cartilage and bone from the outside of the knee joint, where it won’t be missed, and place it in the ankle defect.

A Twisted Ankle Isn’t Just a Simple Sprain

By Jane E. Brody : NY Times Article : July 28, 2009

A sprained ankle is one of the most common joint injuries, prompting many people to consider it “just a sprain” and not treat it with the respect it deserves. The too-common consequence of this neglect is a lasting weakness, an unstable joint and repeated sprains.

Given that some 25,000 ankle sprains occur each day in the United States, it is worth knowing how they can be prevented and how they should be treated.

I suffered two memorable ankle sprains, and although I did better with the second than the first, in neither case did I do everything right.

The first occurred 40 years ago when I was nine months pregnant with twins. I twisted my ankle stepping on an uneven surface in my backyard. The pain subsided in a few minutes, and I did nothing about it. Nothing, that is, until it began to swell and throb hours later and I couldn’t walk. I was not a pretty sight hobbling to the doctor using my husband as a crutch.

The second occurred about two decades ago, when I turned my ankle coming down the stairs of a commuter plane. This time the acute pain was so severe I had to be carried into the airport, where a wheelchair and ice packs were provided. On my connecting four-hour flight, I was given a three-seat row where I could keep my ankle elevated and periodically iced. I slept that night with the pillows under my foot. The next morning, the pain was gone and I went jogging.

The two mistakes: My first injury should have been treated immediately, with rest, ice and elevation and an elastic bandage to keep down the swelling; with the second, I had no business running on that ankle less than 12 hours after the injury.

No Quick Fix I now know that I was lucky not to have ended up with a chronically unstable ankle after either of these episodes. Ankle sprains are so often mistreated or not treated at all, experts say, that they have the highest recurrence rate of any joint injury and often result in chronic symptoms.

Last month at the National Athletic Trainers’ Association annual meeting in San Antonio, experts responsible for the ankle health of college athletes reviewed research evidence for various methods believed to help prevent recurrent ankle sprains. I suspect that few athletes, whether professional, intramural or recreational, will like the bottom line: ankle sprains usually need more rehabilitation and take longer to heal than most people allow for.

Undertreatment means that “30 to 40 percent of people with simple ankle sprains develop chronic long-term joint pathology,” said one presenter, Tricia Hubbard, the undergraduate athletic training director at the University of North Carolina in Charlotte.

“Most research is showing that with any ankle sprain, the ankle should be immediately immobilized to protect the joint and allow the injured ligaments to heal,” Dr. Hubbard said in an interview. “At least a week for the simplest sprain, 10 to 14 days for a moderate sprain and four to six weeks for more severe sprains.”

Yet coaches, like most people, she said, “tend to think, ‘It’s just a sprain, you’ll be fine’ and they tape the ankle and ice it and the player is back on the field in a few days.”

Of course, players want to play, whatever their level, so they rarely question the wisdom of such a quick turnaround.

“Lack of pain is not always the best indicator that it’s safe to resume activity,” Dr. Hubbard said. “The pain of an ankle sprain can subside fairly quickly, but that does not mean the injured ligaments have healed.”

A Vulnerable Joint The ankle, which joins the lower leg bones to the foot, is held together by bands of elastic fibers called ligaments. A sprain results when one or more ligaments is stretched beyond its normal range. In a severe sprain, the elastic fibers tear partly or completely.

Sprains occur when the foot turns in or out to an abnormal degree relative to the ankle. Common causes include stepping up or down on an uneven surface, particularly when wearing shoes with platform soles or high heels; stepping wrong off a curb or into a hole; or stepping on an object left in the wrong place.

In athletics, common causes include coming down wrong after a jump shot or rebound; stepping on another player’s foot; and having to make quick directional changes, as in tennis, basketball, football and soccer.

As with other such injuries, the recommended first aid for an ankle sprain, to be started as soon as possible after the injury, goes by the acronym RICE:

R for rest, I for ice, C for compression, E for elevation. In other words, get off the foot, wrap it in an Ace-type bandage, raise it higher than the heart and ice it with a cloth-wrapped ice pack applied for 20 minutes once every hour (longer application can cause tissue damage).

This should soon be followed by a visit to a doctor, physical therapist or professional trainer, who should prescribe a period of immobilization of the ankle and rehabilitation exercises. An anti-inflammatory drug may be recommended and crutches provided for a few days, especially if the ankle is too painful to bear weight.

The Healing Process Immobilization using a brace or cast provides ligaments with the rest they need to heal and reduces the risk of aggravating the injury. Even a complete ligament tear can heal without surgery through proper immobilization. But immobilization should not be overdone and must be followed in a week by exercises that prevent muscle atrophy and stiffness.

During healing, Dr. Hubbard said, “new tissues are laid down, and they need to be aligned with the action of the joint” through proper exercise.

Rehabilitation should include range-of-motion and stretching exercises, strength training and balance training.

Dr. Hubbard said studies had shown that one of the most effective immobilizers is the AirCast Air-Stirrup ankle brace. This inexpensive half-pound device limits motion but can be removed for needed exercises.

Even after an injury has healed, an athlete’s ankle often needs extra protection during physical activities. Studies reviewed by Jay Hertel, an athletic trainer at the University of Virginia, showed that wearing a lace-up ankle brace was more effective than taping the ankle in preventing reinjury.

Of course, preventing injury in the first place is ideal. Athletic trainers emphasize the importance of wearing proper shoes for your chosen activity — shoes that are comfortable, supportive and not worn out.

Dr. Hubbard says women should be very careful in high heels or platform shoes, which she called “an ankle sprain waiting to happen.”

After a Sprain, Don’t Just Walk It Off

By Jane E. Brody : NY Times : July 22, 2013

Whenever I see a woman walking (or trying to) in stilettos — skinny heels over 3 inches high — my first thought is, “There’s a sprained ankle waiting to happen.”

An estimated 28,000 ankle injuries occur daily in the United States, most of them through sporting activities, including jogging on uneven surfaces. But while no one suggests remaining sedentary to protect your ankles, experts wisely warn against purposely putting them at risk by wearing hazardous shoes or getting back in the game before an injured ankle has healed.

If you’ve ever thought, “Oh, it’s just a sprain,” read on. The latest information about ankle sprains, released in a position statement last month by the National Athletic Trainers’ Association, clearly shows that ankle injuries should never be taken lightly and are too often mistreated or not treated at all.

The result is an ankle prone to prolonged discomfort, reinjury, chronic disability and early arthritis.

Ankle injuries are the most common mishap among sports participants, accounting for nearly half of all athletic injuries. According to the report by the trainers’ association, the highest incidence occurs in field hockey, followed by volleyball, football, basketball, cheerleading, ice hockey, lacrosse, soccer, rugby, track and field, gymnastics and softball.

I was surprised that tennis did not make the list, since any sport that involves quick changes in direction leaves ankles especially vulnerable to unnatural twists. Other reasons for ankle injury among athletes include landing awkwardly from jumps, stepping on another athlete’s foot, trauma to the ankle when the heel lands during running, and stressing the foot when it is in a fixed position.

Perhaps the most interesting finding in the new report is the fact that the most widely accepted treatment for an ankle sprain — rest, ice, compression and elevation, popularly called RICE — has yet to be shown to be effective in controlled clinical trials.

“There’s not a whole lot of good evidence out there to support it,” Thomas W. Kaminski, lead author of the new report, said with a hint of irony in his voice. However, neither he nor his co-authors suggest that this time-honored remedy be abandoned.

What should be abandoned is the temptation to try to walk off the searing pain of a twisted ankle. In fact, in years past, that’s often what athletes were advised to do. But trying to walk on an injured ankle is precisely the wrong approach, the athletic trainers now say.

Also wrong, I was surprised to learn, is to immediately reach for a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) like ibuprofen or naproxen to relieve pain and prevent swelling. Rather, it’s best to start with acetaminophen to control the pain, said Dr. Kaminski, athletic trainer at the University of Delaware.

He explained, “It’s best to wait 48 hours before taking an NSAID because you want the normal inflammatory process to kick in and begin the healing process. Then you take the NSAID to keep the swelling from getting worse.” Don’t take an NSAID on an empty stomach and don’t exceed the dosing directions.

For both people who are physically active and those who are sedentary, the only consistent risk factor for an ankle injury is having suffered a prior sprain. This fact alone underscores the importance of giving ankle injuries the respect and treatment they deserve.

Most important, Dr. Kaminski said, is to have the injury properly diagnosed to determine its extent and, in turn, dictate the proper therapy. This doesn’t necessarily mean you must race off to the emergency room and get an X-ray for every twisted ankle. But coaches, trainers (both athletic and personal), and doctors should know how to do a proper exam, checking for deformity, swelling, discoloration, point tenderness, and the ankle’s range of motion — the foot’s ability to move in all its normal positions.

Although X-rays are typically ordered for 80 percent to 95 percent of patients who go to the emergency room with a foot or ankle injury, an X-ray is not warranted unless there is an obvious deformity, bone tenderness, or an inability to bear weight or walk four steps immediately after the injury, the NATA report says. X-rays do not show damage to soft tissues like ligaments and tendons, the ones most often injured in an ankle sprain.

Nor is an M.R.I. especially helpful; both imaging tests mainly add many dollars to the cost of diagnosing and treating an ankle injury.

What should you do? Immediately after injuring an ankle, begin RICE, described in the report as “universally accepted as best practice by athletic trainers and other health care professionals.” That means get off the injured foot; prop it up, if possible, higher than the heart; wrap it in a compression bandage; and apply cold. There are various ways to ice an injured ankle: ice packs, immersion in ice water, application of frozen cups of ice or frozen bags of peas, chemical cold packs, and cold sprays.

Apply cold for 10 to 20 minutes at a time, then remove it for 10 minutes and reapply. When using an ice pack or chemical cold pack, cover the skin first with a wet cloth to avoid tissue damage. Icing can also be used to reduce discomfort before doing exercises prescribed to strengthen an injured ankle.

No longer are prolonged periods of rest recommended. The emphasis now is on “functional rehabilitation — getting patients moving as soon as possible, doing walking exercises, and enhancing joint mobility,” Dr. Kaminski said.

Most important of all, and often the most neglected, is balance training, which starts with standing on one foot (the injured one) on a firm, even surface, then on a foam surface or trampoline, first with eyes open, then eyes closed.

“The idea is to force the ankle to move under more unstable conditions, as you’d find on a sidewalk, lawn or the beach,” Dr. Kaminski said.

Also helpful is strengthening the structures that support ankle stability and flexibility. Older folks take note: ankle problems are a common risk factor for falls among the elderly, and the stronger the muscles in the lower leg, the more support they provide for the ankles.

An inexpensive way to boost ankle strength is to wrap a resistance band or towel under the ball of the foot and, holding the ends of the band or towel tightly, move the foot in every direction: up, down, to the right and to the left 10 times. Plan to do this exercise three times a day. And, of course, unless you’re a runway model, stay out of those high heels!

How to Fix Bad Ankles

By Gretchen Reynolds : NY Times Article : July 8, 2009

Ankles provide a rare opportunity to recreate a seminal medical study in the comfort of your own home. Back in the mid-1960s, a physician, wondering why, after one ankle sprain, his patients so often suffered another, asked the affected patients to stand on their injured leg (after it was no longer sore). Almost invariably, they wobbled badly, flailing out with their arms and having to put their foot down much sooner than people who’d never sprained an ankle. With this simple experiment, the doctor made a critical, if in retrospect, seemingly self-evident discovery. People with bad ankles have bad balance.

Remarkably, that conclusion, published more than 40 years ago, is only now making its way into the treatment of chronically unstable ankles. “I’m not really sure why it’s taken so long,” says Patrick McKeon, an assistant professor in the Division of Athletic Training at the University of Kentucky. “Maybe because ankles don’t get much respect or research money. They’re the neglected stepchild of body parts.”

At the same time, in sports they’re the most commonly injured body part — each year approximately eight million people sprain an ankle. Millions of those will then go on to sprain that same ankle, or their other ankle, in the future. “The recurrence rate for ankle sprains is at least 30 percent,” McKeon says, “and depending on what numbers you use, it may be high as 80 percent.”

A growing body of research suggests that many of those second (and often third and fourth) sprains could be avoided with an easy course of treatment. Stand on one leg. Try not to wobble. Hold for a minute. Repeat.

This is the essence of balance training, a supremely low-tech but increasingly well-documented approach to dealing with unstable ankles. A number of studies published since last year have shown that the treatment, simple as it is, can be quite beneficial.

In one of the best-controlled studies to date, 31 young adults with a history of multiple ankle sprains completed four weeks of supervised balance training. So did a control group with healthy ankles. The injured started out much shakier than the controls during the exercises. But by the end of the month, those with wobbly ankles had improved dramatically on all measures of balance. They also reported, subjectively, that their ankles felt much less likely to give way at any moment. The control group had improved their balance, too, but only slightly. Similarly, a major review published last year found that six weeks of balance training, begun soon after a first ankle sprain, substantially reduced the risk of a recurrence. The training also lessened, at least somewhat, the chances of suffering a first sprain at all.

Why should balance training prevent ankle sprains? The reasons are both obvious and quite subtle. Until recently, clinicians thought that ankle sprains were primarily a matter of overstretched, traumatized ligaments. Tape or brace the joint, relieve pressure on the sore tissue, and a person should heal fully, they thought. But that approach ignored the role of the central nervous system, which is intimately tied in to every joint. “There are neural receptors in ligaments,” says Jay Hertel, an associate professor of kinesiology at the University of Virginia and an expert on the ankle. When you damage the ligament, “you damage the neuro-receptors as well. Your brain no longer receives reliable signals” from the ankle about how your ankle and foot are positioned in relation to the ground. Your proprioception — your sense of your body’s position in space — is impaired. You’re less stable and more prone to falling over and re-injuring yourself.

For some people, that wobbliness, virtually inevitable for at least a month after an initial ankle sprain, eventually dissipates; for others it’s abiding, perhaps even permanent. Researchers don’t yet know why some people don’t recover. But they do believe that balance training can return the joint and its neuro-receptor function almost to normal.

Best of all, if you don’t mind your spouse sniggering, you can implement state-of-the-art balance training at home. “We have lots of equipment here in our lab” for patients to test, stress, and improve their balance, Hertel says. “But all you really need is some space, a table or wall nearby to steady yourself if needed, and a pillow.” (If you’ve recently sprained your ankle, wait until you comfortably can bear weight on the joint before starting balance training.) Begin by testing the limits of your equilibrium. If you can stand sturdily on one leg for a minute, cross your arms over your chest. If even that’s undemanding, close your eyes. Hop. Or attempt all of these exercises on the pillow, so that the surface beneath you is unstable. “One of the take-home exercises we give people is to stand on one leg while brushing your teeth, and to close your eyes if it’s too easy,” Hertel says. “It may sound ridiculous, but if you do that for two or three minutes a day, you’re working your balance really well.”

Plantar Fasciitis : Overview

Plantar fasciitis is irritation and swelling of the thick tissue on the bottom of the foot.

Causes »

The plantar fascia is a very thick band of tissue that covers the bones on the bottom of the foot. This fascia can become inflamed and painful in some people, making walking more difficult.

Risk factors for plantar fasciitis include:

- Foot arch problems (both flat foot and high arches)

- Obesity

- Running

- Sudden weight gain

- Tight Achilles tendon (the tendon connecting the calf muscles to the heel)

This condition is one of the most common orthopedic complaints relating to the foot.

Plantar fasciitis is commonly thought of as being caused by a heel spur, but research has found that this is not the case. On x-ray, heel spurs are seen in people with and without plantar fasciitis.

In-Depth Causes »

Symptoms:

The most common complaint is pain in the bottom of the heel, usually worst in the morning and improving throughout the day. By the end of the day the pain may be replaced by a dull aching that improves with rest.

Exams and Tests:

Typical physical exam findings include:

- Mild swelling

- Redness

- Tenderness on the bottom of the heel

Treatment:

Conservative treatment is almost always successful, given enough time. Treatment can last from several months to 2 years before symptoms get better. Most patients will be better in 9 months.

Initial treatment usually consists of:

- Anti-inflammatory medications

- Heel stretching exercises

- Night splints

- Shoe inserts

Some physicians will offer steroid injections, which can provide lasting relief in many people. However, this injection is very painful and not for everyone.

In a few patients, non-surgical treatment fails and surgery to release the tight, inflamed fascia becomes necessary.

Outlook (Prognosis):

Nearly all patients will improve within 1 year of beginning non-surgical therapy, with no long-term problems. In the few patients requiring surgery, most have relief of their heel pain.

Possible Complications:

Complications with surgery include:

- Infection

- Nerve injury

- No improvement in pain

- Rupture of the plantar fascia

Prevention »

Maintaining good flexibility around the ankle, particularly the Achilles tendon and calf muscles, is probably the best way to prevent plantar fasciitis.

No Consensus on a Common Cause of Foot Pain

By Gretchen Reynolds: NY Times : February20, 2013

There are more charismatic-sounding sports injuries than plantar fasciitis, like tennis elbow, runner’s knee and turf toe. But there aren’t many that are more common. The condition, characterized by stabbing pain in the heel or arch, sidelines up to 10 percent of all runners, as well as countless soccer, baseball, football and basketball players, golfers, walkers and others from both the recreational and professional ranks. The Lakers star Kobe Bryant, the quarterback Eli Manning, the Olympic marathon runner Ryan Hall and the presidential candidate Mitt Romney all have been stricken.

But while plantar fasciitis is democratic in its epidemiology, its underlying cause remains surprisingly enigmatic. In fact, the mysteries of plantar fasciitis underscore how little is understood, medically, about overuse sports injuries in general and why, as a result, they remain so insidiously difficult to treat.

Experts do agree that plantar fasciitis is, essentially, an irritation of the plantar fascia, a long, skinny rope of tissue that runs along the bottom of the foot, attaching the heel bone to the toes and forming your foot’s arch. When that tissue becomes irritated, you develop pain deep within the heel. The pain is usually most pronounced first thing in the morning, since the fascia tightens while you sleep.

But scientific agreement about the condition and its causes ends about there.

For many years, “most of us who treat plantar fasciitis believed that it involved chronic inflammation” of the fascia, said Dr. Terrence M. Philbin, a board-certified orthopedic surgeon at the Orthopedic Foot and Ankle Center in Westerville, Ohio, who specializes in plantar fasciitis.

It was thought that by running or otherwise repetitively pounding their heels against the ground, people strained the plantar fascia, and the body responded with a complex cascade of inflammatory biochemical processes that resulted in extra blood and fluids flowing to the injury site, as well as enhanced pain sensitivity.

But instead of lasting only a few days and then fading, as acute inflammation usually does, the process can become chronic and create its own problems, causing tissue damage and continuing pain.

This progression is also what experts believed was happening when people developed chronic Achilles’ tendon pain, tennis elbow or other lingering, overuse injuries.

But when scientists actually biopsied fascia tissue from people with chronic plantar fasciitis, “they did not find much if any inflammation,” Dr. Philbin said. There were virtually none of the cellular markers that characterize that condition.

“Plantar fasciitis does not involve inflammatory cells,” said Dr. Karim Khan, a professor of family practice medicine at the University of British Columbia and editor of The British Journal of Sports Medicine, who has written extensively about overuse sports injuries.

Instead, plantar fasciitis more likely is caused by degeneration or weakening of the tissue. This process probably begins with small tears that occur during activity and that, in normal circumstances, the body simply repairs, strengthening the tissue as it does. That is the point of exercise training.

But sometimes, for unknown reasons, this ongoing tissue damage overwhelms the body’s capacity to respond. The small tears don’t heal. They accumulate. The tissue begins subtly to degenerate, even to shred. It hurts.

By and large, most sports medicine experts now believe that this is how we develop other overuse injuries, like tennis elbow or Achilles tendinopathy, which used to be called tendinitis. The suffix “itis” means inflammation. But since the injury isn’t thought to involve chronic inflammation, its name has changed.

This has not yet happened with plantar fasciitis, and may not, given what a mouthful fasciopathy would be.

The evolving medical opinions about plantar fasciitis matter, beyond nomenclature, though, because treatments depend on causes. At the moment, many physicians rely on injections of cortisone, a steroid that is both a pain reliever and anti-inflammatory, to treat plantar fasciitis. And cortisone shots do reduce the soreness. In a study published last year in BMJ, patients who received cortisone injections reported less heel pain after four months than those whose shots had contained a placebo saline solution.

But whether those benefits will last is unknown, especially if plantar fasciitis is, indeed, degenerative. In studies with people suffering from tennis elbow, another injury that is now considered degenerative, cortisone shots actually slowed tissue healing.

We need similar studies in people with plantar fasciitis, Dr. Khan said. “They have not been done.”

Thankfully, most people who develop plantar fasciitis will recover within a few months without injections or other invasive treatments, Dr. Philbin said, if they simply back off their running mileage somewhat or otherwise rest the foot and stretch the affected tissues. Stretching the plantar fascia, as well as the Achilles’ tendon, which also attaches to the heel bone, and the hamstring muscles seems to result in less strain on the fascia during activity, meaning less ongoing trauma and, eventually, time for the body to catch up with repairs.

To ensure that you are stretching correctly, Dr. Philbin suggests consulting a physical therapist, after, of course, visiting a sports medicine doctor for a diagnosis. Not all heel or arch pain is plantar fasciitis. And comfort yourself if you do have the condition with the knowledge that Kobe Bryant, Eli Manning and Ryan Hall have all returned to competition and Mr. Romney still runs.

Follow up article:

Plantar fasciitis, or pain in the foot, especially near the heel or arch, is sadly familiar to many of us who run, walk, play basketball or tennis or otherwise are active. An irritation of the long, skinny rope of tissue that runs along the bottom of the foot, it’s one of the most frequent overuse injuries, especially as we age.

Until recently, scientists believed that it was an inflammatory condition. But when they microscopically examined tissue from sore heels, they found little evidence of inflammation. Instead, the injury seems to involve degeneration of the tissue; small tears in the fascia accumulate and become a constant, debilitating ache.

Because there’s little inflammation, anti-inflammatory drugs, like ibuprofen, are unlikely to aid in healing the problem. A better response, says Dr. Terrence M. Philbin, a orthopedic surgeon at the Orthopedic Foot and Ankle Center in Westerville, Ohio, is ‘‘first, to back off training,’’ allowing the slight tears in the tissue to heal. If you run every day, drop to twice a week or walk for a while.

Meanwhile, stretch. While stretching may be of equivocal value among the healthy, it aids in recovery from sore feet.

“Stretching the calves and Achilles’ tendon is important,” Dr. Philbin says. For a full program of stretches, consult a physical therapist, he says. But a simple, effective calf stretch, according to the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons, involves leaning forward against a wall with one leg behind you, heel on the ground, and the other leg ahead and bent, as if you were taking a step. Push your hips toward the wall to fully stretch the calf of the back leg. Hold for 10 seconds, and repeat 20 times on each leg.

And be patient. Recovery from plantar fasciitis typically requires months, Dr. Philbin says, but for most people, it does happen, and without surgery or other invasive treatment.

Can I get relief for plantar fasciitis?

If you have stairs or a sturdy box in your home and a backpack, timely relief for plantar fasciitis may be possible, according to a new study of low-tech treatments for the condition.

Plantar fasciitis, the heel pain caused by irritation of the connective tissue on the bottom of the foot, can be lingering and intractable. A recent study of novice runners found that those who developed plantar fasciitis generally required at least five months to recover, and some remained sidelined for a year or more.

Until recently, first-line treatments involved stretching and anti-inflammatory painkillers such as ibuprofen or cortisone. But many scientists now believe that anti-inflammatories are unwarranted, because the condition involves little inflammation. Stretching is still commonly recommended.

But the new study, published in August in the Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, finds that a single exercise could be even more effective. It requires standing barefoot on the affected leg on a stair or box, with a rolled-up towel resting beneath the toes of the sore foot and the heel extending over the edge of the stair or box. The unaffected leg should hang free, bent slightly at the knee.

Then slowly raise and lower the affected heel to a count of three seconds up, two seconds at the top and three seconds down. In the study, once participants could complete 12 repetitions fairly easily, volunteers donned a backpack stuffed with books to add weight. The volunteers performed eight to 12 repetitions of the exercise every other day.

Other volunteers completed a standard plantar fasciitis stretching regimen, in which they pulled their toes toward their shins 10 times, three times a day.

After three months, those in the exercise group reported vast improvements. Their pain and disability had declined significantly.Those who did standard stretches, on the other hand, showed little improvement after three months, although, with a further nine months of stretching, most reported pain relief.

The upshot, said Michael Skovdal Rathleff, a researcher at Aalborg University in Denmark, who led the study, is that there was “a quicker reduction in pain” with the exercise program, and a reminder of how books, in unexpected ways, can help us heal.

Foot, Leg, and Ankle Swelling : Overview

Abnormal buildup of fluid in the ankles, feet, and legs is called peripheral edema.

Alternative Names

Swelling of the ankles - feet - legs; Ankle swelling; Foot swelling; Leg swelling; Edema - peripheral; Peripheral edema

Considerations

Painless swelling of the feet and ankles is a common problem, particularly in older people. It may affect both legs and may include the calves or even the thighs. Because of the effect of gravity, swelling is particularly noticeable in these locations.

Common Causes

Foot, leg, and ankle swelling is common with the following situations:

- Prolonged standing

- Long airplane flights or automobile rides

- Menstrual periods (for some women)

- Pregnancy -- excessive swelling may be a sign of pre-eclampsia, a serious condition sometimes called toxemia, that includes high blood pressure and swelling

- Being overweight

- Increased age

- Injury or trauma to your ankle or foot

Other conditions that can cause swelling to one or both legs include:

- Blood clot

- Leg infection

- Venous insufficiency (when the veins in your legs are unable to adequately pump blood back to the heart)

- Varicose veins

- Burns (including sunburn)

- Insect bite or sting

- Starvation or malnutrition

- Surgery to your leg or foot

- Hormones like estrogen (in birth control pills or hormone replacement therapy) and testosterone

- A group of blood pressure lowering drugs called calcium channel blockers (such as nifedipine, amlodipine, diltiazem, felodipine, and verapamil)

- Steroids

- Antidepressants, including MAO inhibitors (such as phenelzine and tranylcypromine) and tricyclics (such as nortriptyline, desipramine, and amitriptyline)

- Elevate your legs above your heart while lying down.

- Exercise your legs. This helps pump fluid from your legs back to your heart.

- Wear support stockings (sold at most drug and medical supply stores).

- Try to follow a low-salt diet, which may reduce fluid retention and swelling.

- You feel short of breath.

- You have chest pain, especially if it feels like pressure or tightness.

- You have decreased urine output.

- You have a history of liver disease and now have swelling in your legs or abdomen.

- Your swollen foot or leg is red or warm to the touch.

- You have a fever.

- You are pregnant and have more than just mild swelling or have a sudden increase in swelling.

What to Expect at Your Health Care Provider's Office

Your doctor will take a medical history and conduct a thorough physical examination, with special attention to your heart, lungs, abdomen, legs, and feet.

Your doctor will ask questions like the following:

- What specific body parts swell? Your ankles, feet, legs? Above the knee or below?

- Do you have swelling at all times or is it worse in the morning or the evening?

- What makes your swelling better?

- What makes your swelling worse?

- Does the swelling get better when you elevate your legs?

- What other symptoms do you have?

- Blood tests such as a CBC or blood chemistry

- ECG

- Chest x-ray or extremity x-ray

- Urinalysis

Prevention

Avoid sitting or standing without moving for prolonged periods of time. When flying, stretch your legs often and get up to walk when possible. When driving, stop to stretch and walk every hour or so. Avoid wearing restrictive clothing or garters around your thighs. Exercise regularly. Lose weight if you need to.

Summer Flip-Flops May Lead to Foot Pain

Flip-flops are a mainstay of summertime footwear, but they can be painfully bad for your feet and legs, new research shows.

Researchers from Auburn University in Alabama studied the biomechanics of the flip-flop and determined that wearing thong-style flip-flops can result in sore feet, ankles and legs.

“We found that when people walk in flip-flops, they alter their gait, which can result in problems and pain from the foot up into the hips and lower back,'’ said Justin Shroyer, a biomechanics doctoral student who presented the findings to the recent annual meeting of the American College of Sports Medicine in Indianapolis.

For the study, the researchers recruited 39 college-age men and women and asked them to wear flip-flops or athletic shoes. They then had them walk a platform that measured vertical force as their feet hit the ground. A video camera measured stride length and limb angles.

Flip-flop wearers took shorter steps and their heels hit the ground with less vertical force than when the same walkers wore athletic shoes. People wearing flip-flops also don’t bring their toes up as much as the leg swings forward. That results in a larger angle to the ankle and a shorter stride length, the study showed. The reason may be that people tend to grip flip-flops with their toes.

Mr. Shroyer notes that he himself owns two pairs of flip-flops, and the research doesn’t mean people shouldn’t wear them. However, flip-flops are best worn for short periods of time, like at the beach or for comfort after an athletic event. But they are not designed to properly support the foot and ankle during all-day wear, he notes.

Unhappy Feet

By Gretchen Reynolds : NY Times : September 14, 2008

Within the sports world, as elsewhere, sore feet don’t command much respect. “Athletes will play through a level of pain in their feet that, if they felt it in their knees or their shoulders, they’d be hammering at a surgeon’s door,” says Glenn Pfeffer, the director of the Foot and Ankle Center at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles. Aching feet are the “forgotten stepchild” of sports injuries, he adds. Remember Lakers guard Kobe Bryant’s bout with plantar fasciitis, a painful heel condition, in 2004? Probably not, because the complaint, unpleasant as it was, didn’t constitute a very heroic sports story. When he experienced twinges in his back earlier this year, however, it made headlines.

The ignoble status that injured feet have among athletes is puzzling, because foot troubles aren’t just debilitating; in many sports they’re also common. A 2004 Duke University study of 26 N.C.A.A. men’s basketball players found six feet that showed signs of serious trauma upon M.R.I. examination. Two of the players hadn’t experienced foot pain, but the bone marrow in their metatarsals (the five long bones of the feet) was flooded with excess fluid, a possible early indicator of tissue and bone damage and often of an imminent stress fracture. One of them, in fact, developed a stress fracture not long after the study began and had to sit out the remainder of the season.

Additional research has found similar foot trauma from other sports, particularly running. A small but compelling 2003 study done in Brussels looked at the impact of running for 30 minutes a day for one week. The 10 subjects were new to the sport. Three showed slight signs of foot damage before the study. At the end of the week, half of the runners had either new or increased fluid accumulation in their bone marrow. After only seven days, the newbie joggers had pounded their feet into the earliest stages of stress fracture.

The foot is at such high risk for injury largely because it has so many small, frangible parts — 26 bones, 33 joints and more than 100 tendons, ligaments and muscles, any of which can fail. Nevertheless, under ideal conditions, feet are built to handle the abuse of even high-impact sports. “A healthy foot, like a car, has two ways to absorb pressure: it has pads and it has springs,” says Carol Frey, the director of orthopedic foot and ankle surgery at the West Coast Center for Orthopedic Surgery and Sports Medicine in Manhattan Beach, Calif. The pads are the cushiony pillows of fat beneath the heel and

the ball of the foot. The springs are its tendons and ligaments, which flex and bend as the foot moves. Strong tendons and ligaments can withstand several times a person’s body weight — the force with which a foot can hit the ground while jumping or running downhill.

But as athletes reach their 30s or 40s, the fat pads that help to absorb impact start to thin. There’s no way to replump them permanently, although some foot doctors have tried injecting the soles of patients’ feet with collagen or other fillers. Meanwhile, the foot’s once-springy tendons and ligaments tighten up along with the rest of an athlete’s aging body. Foot tissues connect to those in the lower leg, particularly the Achilles’ tendon, that long, thick, tensile rope that binds the powerful muscles of the calf to the heel. If the tendon becomes inflexible, it pulls the calf muscles taut. It also strains the plantar fascia, the main ligament on the underside of the foot. Stretched too far, the plantar fascia becomes inflamed. This is the condition known as plantar fasciitis. If you’ve had it, you know how crippling this pain can be, especially in severe cases where plantar-fascia fibers shred away from the heel bone.

“I expect to return to running,” says Larry Green, a former amateur marathoner and triathlete from Orange County, Calif. “I’m not at the point where I want to give up.” But he has had reason to doubt whether it’s worth it. Last winter, Green was out for a run when he felt a sudden “ripping snap” deep in his foot. He’d partially torn some of the tissue that attaches to the plantar fascia, possibly as a result of a course of the antibiotic, Ciprofloxacin, which has been associated with sudden tissue ruptures in tendons. Half a year later, he still needs his boot-size brace on occasion. “Your feet support your weight,” he says. “You don’t really think about that until they start to hurt. Then you can’t not think about it.”

Injuries to the plantar fascia and connected tissues are the most common foot ailment in athletes over 30. Many people, feeling the first stabs of heel pain from an injured fascia, switch to softer, looser athletic shoes, thinking that will cosset the foot and correct the problem. It does the opposite. “Adding soft cushioning beneath your feet increases instability,” says Douglas Richie, a podiatrist in Seal Beach, Calif., and a former president of the American Academy of Podiatric Sports Medicine. The unsupported foot rolls too much, and the tight tissues get pulled even tighter.

The best way to prevent and treat early-stage plantar fasciitis is simple and cheap: “Stretch, stretch, stretch,” Pfeffer says. “You need to loosen the tight calf and foot muscles.” Though some researchers have questioned the efficacy of stretching in general, that’s not the case when it comes to feet. The regimen of stretches recommended by most foot specialists isn’t strenuous: it involves such established exercises as dangling your heel from a stair step or grasping your bare toes and pulling them toward you. But it does require commitment. “I’d like to see people stretching three to four times a day,” Pfeffer says, “not two or three times a week, which is probably what most people consider enough.” (You can find stretching instructions at footankleinstitute.com.) Those with a more feckless attitude can invest in a ProStretch, a crescent-shaped plastic device that “does the stretching for you,” Frey says. It’s available at many drugstores and Web sites for less than $50.

Extremely tight Achilles’ tendons might respond to a technique called heavy-load eccentric training, in which you perform stretching exercises while carrying extra weight, like a backpack. To avoid injuring yourself further, though, don’t try this without the help of a physical therapist or trainer.

If stretching doesn’t provide relief, more drastic measures might be required, including a brace like the one Green uses. Custom orthotics, which raise the heel and reduce pressure from a tight Achilles’ tendon, can also help, but they’re pricey (often $400 or more), and some research has indicated that they’re no better in the long term for treating plantar fasciitis than the gel inserts you can buy at any Walgreens. A reputable sports podiatrist can tell you if your degree of injury calls for custom orthotics.

Two additional treatments for intractable heel pain have shown promise: one uses a radio-frequency probe to break up scar tissue along the fascia, and another merely deadens the nerves in the heel. “Plantar fasciitis is almost always self-limiting,” Richie says, meaning that it forces you to stay off your foot until it heals. “This technique allows the patient to get through the pain until the condition finally resolves.”

Not all foot problems, of course, involve the fascia. Millions of athletes suffer from such uncharismatic ailments as blisters, bunions, hammertoes, pinched nerves and that distance-runner’s nuisance, black, loosened toenails. Some of these complaints are caused by innate deficiencies in a person’s gait — landing on your toes and not your midfoot or heel, for instance, which sends the full jolt of the impact through the skinny bones of the forefoot and can cause stress fractures and other damage; or overpronation, a common problem in which the foot rolls too far inward during each stride. If you have low arches, you probably have a tendency to overpronate, so look for shoes that promise “motion control.”

Many foot injuries are, in fact, the result of wearing the wrong shoes or the wrong shoe size. Studies have suggested that Americans too often wear shoes that don’t fit, and athletes are no exception. Shoes that are too narrow through the toe box contribute directly to the formation of blisters and bunions. Those that are too short lead to hammertoes and blackened nails, and those in which the flex point of the shoe doesn’t hit exactly at the flex point of the foot can cause pinched nerves and stress fractures. To ensure that your shoes fit, shop at the end of the day, when feet are at their largest, and have your feet measured. “You can add a shoe size or more during adulthood,” Richie points out. If you have plantar fasciitis or other heel pain, he says, choose shoes that also have at least an inch of lift in the heel.

As for those balletic types who land on their toes while running, most foot experts suggest a consultation with a coach or trainer to correct your stride. With few exceptions, you could generate more power and speed, and avoid many metatarsal stress fractures, by learning to strike the ground nearer to your heel.

“The majority of sports-related foot injuries are preventable,” Pfeffer says, somewhat forlornly, “if people would just start paying attention.”

The Many Ills of Peripheral Nerve Damage

By Jane E. Brody : NY Times Article : October 20, 2009

If you have ever slept on an arm and awakened with a “dead” hand, or sat too long with your legs crossed and had your foot fall asleep, you have some inkling of what many people with peripheral neuropathy

And numbness and tingling are hardly the worst symptoms of this highly variable condition, which involves damage to one or more of the myriad nerves outside the brain and spinal cord. Effects may include disabling pain, stinging, swelling, burning, itching, muscle weakness, twitching, loss of sensation, hypersensitivity to touch, lack of coordination, difficulty breathing, digestive disorders, dizziness, impotence, incontinence, and even paralysis and death.

I realize now that I had a mild, reversible bout of peripheral neuropathy several decades ago when a misplaced shot of morphine damaged a sensory nerve in my thigh. It took three years for the nerve to recover, and for much of that time I could not tolerate anything brushing against my leg.

One of my sons, too, was afflicted when a nerve behind his knee was injured during a basketball game. He had no feeling or mobility in his foot for nine months, but after several years the nerve healed and he regained full use of his foot.

And a good friend was nearly paralyzed, also temporarily, following a flu shot, by a far more serious form of peripheral neuropathy — an autoimmune affliction called Guillain-Barré syndrome, in which one’s own antibodies attack the myelin sheath that protects nerves throughout the body.

There are hundreds of forms of peripheral neuropathy. A medical guide describing them, compiled by a team of neurologists at the behest of the Neuropathy Association, fills a booklet the size of a two-year wall calendar.

The association, which sponsors research and provides education and support for patients and families dealing with peripheral neuropathy, estimates that the disorder afflicts more than 20 million Americans at any given time. If the cause can be corrected, peripheral nerves can regenerate slowly and patients can recover, although not always completely.

But many people never recover. They must learn to live with the disorder, with the help of treatments and devices that can ease their discomfort and disability. With such a wide array of symptoms and causes, getting a correct diagnosis is often a challenge. Worse, frustrated patients are sometimes told, “It’s all in your head.”

Causes Behind an Ailment

There are three types of peripheral nerves:

- sensory nerves, which transmit sensations like pain, touch, heat and cold;

- motor nerves, which control the action of muscles throughout the body;

- and autonomic nerves, which regulate functions that are not under conscious control, like blood pressure, digestion and heart rate.

Someone with damaged sensory nerves might not feel heat, for example, and could be scalded by an overly hot bath. Neuropathy of the motor nerves can result in weakness, lack of coordination or paralysis; neuropathy of the autonomic nerves can lead to high blood pressure, irregular heart rate, diarrhea or constipation, impotence and incontinence.

The list of possible causes of neuropathy is far too long for this column. They include inherited conditions like Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease; infections or inflammatory disorders like hepatitis, Lyme disease, AIDS, rheumatoid arthritis and lupus; organ diseases like diabetes, hypothyroidism and kidney disease; exposure to toxic substances like industrial solvents, heavy metals, sniffed glue and some cancer drugs; trauma to or pressure on a nerve from an injury, cast, crutches, abnormal body position, repetitive motion (as in carpal tunnel syndrome), tumor or abnormal bone growth; alcoholism; and deficiency of vitamin B12.

The most common cause, accounting for nearly a third of neuropathy cases, is diabetes, especially among those whose blood sugar levels are poorly controlled. Half of all people with diabetes eventually begin to lose sensation and develop pain and sometimes weakness in their feet and hands. In people with diabetes, even minor injuries to the feet, if not quickly and properly treated, can result in gangrene and amputations.

In nearly a third of cases, no cause is ever found, leaving patients with no other recourse than treatment of their symptoms.

Suspected cases are best referred to a neurologist, who should begin by taking a complete personal and family medical history and performing a physical and neurological examination, checking on reflexes, muscle strength and tone, sensations, balance and coordination.

A complete workup is likely to include blood tests, urinalysis, a nerve conduction study and electronic measurements of muscle activity. Imaging studies, like a CT scan or an M.R.I., may reveal a tumor, vertebral damage or abnormal bone growth. In some cases, a nerve or muscle biopsy may be done.

Relief and Restoration If the underlying cause cannot be corrected, the goals of treatment are relief of symptoms and restoration of lost functions. Pain control is paramount. Effective relief may come from over-the-counter remedies or a lidocaine patch but sometimes requires prescribed opiates.

Many with neuropathic pain have benefited from drugs licensed for other uses, including antiseizure medications like gabapentin, topiramate (Topamax) and pregabalin (Lyrica) and antidepressants like the tricyclic amitriptyline and the selective serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor duloxetine (Cymbalta). Vitamin B12 deficiency can be treated with supplements and fortified cereals or by judicious consumption of meats, poultry, fish, eggs and dairy products.

And since alcohol and tobacco are particularly risky for people with neuropathy, or a health problem that predisposes them to it, they have every reason to quit smoking and to drink only in moderation.

Many patients are helped by physical therapy, occupational therapy and devices like braces, splints and wheelchairs. Railings on stairways and in the bathroom, elimination of tripping hazards like scatter rugs, and improved lighting (including night-lights) can reduce the risk of falls. For those insensitive to heat, a thermometer should be used to test water in a tub, shower or sink. Orthopedic shoes are invaluable to patients with lost sensitivity in their feet or impaired balance.

A variety of mechanical aids can make it easier to live with peripheral neuropathy, among them kitchen tools made by Oxo. Those with digestive problems might try eating small frequent meals and sleeping with their heads elevated.

Other helpful sources include the book “Peripheral Neuropathy: When the Numbness, Weakness and Pain Won’t Stop” (Demos Health, 2006), by Dr. Norman Latov, professor of neurology and neuroscience at Weill Cornell Medical College; and the Neuropathy Association, 60 East 42nd Street, Suite 942, New York, N.Y. 10165-0930 (800-247-6968, or online at www.neuropathy.org). The association maintains a list of support groups and of centers that specialize in diagnosing and treating neuropathy.

Do Certain Types of Sneakers Prevent Injuries?

By Gretchen Reynolds : NY Times : July 21, 2010

A few years ago, the military began analyzing the shapes of recruits’ feet. Injuries during basic training were rampant, and military authorities hoped that by fitting soldiers with running shoes designed for their foot types, injury rates would drop. Trainees obediently began clambering onto a high-tech light table with a mirror beneath it, designed to help outline a subject’s foot. Evaluators classified the recruits as having high, normal or low arches, and they passed out running shoes accordingly.

Many of us have had a similar experience. For decades, coaches and shoe salesmen have visually assessed runners’ foot types to recommend footwear. Runners with high arches have been directed toward soft, well-cushioned shoes, since it’s thought that high arches prevent adequate pronation, or the inward motion of your foot and ankle as you run. Pronation dissipates some of the forces generated by each stride. Flat-footed, low-arched runners, who tend to over-pronate, have typically been told to try sturdy “motion control” shoes with firm midsoles and Teutonic support features, while runners with normal arches are offered neutral shoes (often called “stability” shoes by the companies that make and categorize them)

But as the military prepared to invest large sums in more arch-diagnosing light tables, someone thought to ask if the practice of assigning running shoes by foot shape actually worked. The approach was entrenched in the sports world and widely accepted. But did it actually reduce injuries? Military researchers checked the scientific literature and found that no studies had been completed that answered that question, so eventually they decided they would have to mount their own. They began fitting thousands of recruits in the Army, Air Force and Marine Corps with either the “right” shoes for their feet or stability shoes.

Over the course of three large studies, the most recent of which was published last month in The American Journal of Sports Medicine, the researchers found almost no correlation at all between wearing the proper running shoes and avoiding injury. Injury rates were high among all the runners, but they were highest among the soldiers who had received shoes designed specifically for their foot types. If anything, wearing the “right” shoes for their particular foot shape had increased trainees’ chances of being hurt.

Scientific rumblings about whether running shoes deliver on their promises have been growing louder in recent years. In 2008, an influential review article in The British Journal of Sports Medicine concluded that sports-medicine specialists should stop recommending running shoes based on a person’s foot posture. No scientific evidence supported the practice, the authors pointed out, concluding that “the true effects” of today’s running shoes “on the health and performance of distance runners remain unknown.”

More recently, a study published online in late June in The British Journal of Sports Medicine produced results similar to those in the military experiments, this time using experienced distance runners as subjects. For the study, 81 women were classified according to their foot postures, a more comprehensive measure of foot type than arch shape. About half of the runners received shoes designated by the shoe companies as appropriate for their particular foot stance (underpronators were given cushiony shoes, overpronators motion-control shoes and so on). The rest received shoes at random. All of the women started a 13-week, half-marathon training program. By the end, about a third had missed training days because of pain, with a majority of the hurt runners wearing shoes specifically designed for their foot postures. (It’s worth noting that across the board, motion-control shoes were the most injurious for the runners. Many overpronators, who, in theory, should have benefited from motion-control shoes, complained of pain and missed training days after wearing them, as did a number of the runners with normal feet and every single underpronating runner assigned to the motion-control shoes.)

The lesson of the newest studies is obvious if perhaps disconcerting to those of us planning to invest in new running shoes this summer. “You can’t simply look at foot type as a basis for buying a running shoe,” says Dr. Bruce H. Jones, the manager of the Injury Prevention Program for the United States Army’s Public Health Command and senior author of the military studies. The widespread belief that flat-footed, overpronating runners need motion-control shoes and that high-arched, underpronating runners will benefit from well-cushioned pairs is quite simply, he adds, “a myth.”

The mythology grew and persists, however, in large part because “in certain aspects, the shoes do work,” says Michael Ryan, Ph.D., the lead author of the study of female half-marathoners and currently a postdoctoral fellow in the department of orthopedics and rehabilitation at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. Motion-control shoes, for instance, do control motion, he says. Biomechanical studies of runners on treadmills repeatedly have proved that pronation is significantly reduced in runners who wear motion-control shoes.

The problem is that “no one knows whether pronation is really the underlying issue,” Dr. Jones says. Few scientific studies have examined how or even if over- or underpronation contributes to running injuries. “There is so much that we still don’t understand about the biomechanics of the lower extremities,” Dr. Jones concludes.

For now, if you’re heading out to buy new running shoes, plan to be your own best advocate. “If a salesperson says you need robust motion-control shoes, ask to try on a few pairs of neutral or stability shoes, too,” Mr. Ryan says. “Go outside and run around the block” in each pair. “If you feel any pain or discomfort, that’s your first veto.” Hand back those shoes. Try several more pairs. “There really are only a few pairs that will fit and feel right” for any individual runner, he says. “My best advice is, turn on your sensors and listen to your body, not to what the salespeople might tell you.”

By Gretchen Reynolds : NY Times : July 21, 2010

A few years ago, the military began analyzing the shapes of recruits’ feet. Injuries during basic training were rampant, and military authorities hoped that by fitting soldiers with running shoes designed for their foot types, injury rates would drop. Trainees obediently began clambering onto a high-tech light table with a mirror beneath it, designed to help outline a subject’s foot. Evaluators classified the recruits as having high, normal or low arches, and they passed out running shoes accordingly.

Many of us have had a similar experience. For decades, coaches and shoe salesmen have visually assessed runners’ foot types to recommend footwear. Runners with high arches have been directed toward soft, well-cushioned shoes, since it’s thought that high arches prevent adequate pronation, or the inward motion of your foot and ankle as you run. Pronation dissipates some of the forces generated by each stride. Flat-footed, low-arched runners, who tend to over-pronate, have typically been told to try sturdy “motion control” shoes with firm midsoles and Teutonic support features, while runners with normal arches are offered neutral shoes (often called “stability” shoes by the companies that make and categorize them)

But as the military prepared to invest large sums in more arch-diagnosing light tables, someone thought to ask if the practice of assigning running shoes by foot shape actually worked. The approach was entrenched in the sports world and widely accepted. But did it actually reduce injuries? Military researchers checked the scientific literature and found that no studies had been completed that answered that question, so eventually they decided they would have to mount their own. They began fitting thousands of recruits in the Army, Air Force and Marine Corps with either the “right” shoes for their feet or stability shoes.

Over the course of three large studies, the most recent of which was published last month in The American Journal of Sports Medicine, the researchers found almost no correlation at all between wearing the proper running shoes and avoiding injury. Injury rates were high among all the runners, but they were highest among the soldiers who had received shoes designed specifically for their foot types. If anything, wearing the “right” shoes for their particular foot shape had increased trainees’ chances of being hurt.

Scientific rumblings about whether running shoes deliver on their promises have been growing louder in recent years. In 2008, an influential review article in The British Journal of Sports Medicine concluded that sports-medicine specialists should stop recommending running shoes based on a person’s foot posture. No scientific evidence supported the practice, the authors pointed out, concluding that “the true effects” of today’s running shoes “on the health and performance of distance runners remain unknown.”