- RETIREMENT ANNOUNCEMENT

- HOME PAGE

- "MYCHART" the new patient portal

- BELMONT MEDICAL ASSOCIATES

- MOUNT AUBURN HOSPITAL

- EMERGENCIES

- PRACTICE PHILOSOPHY

- MY RESUME

- TELEMEDICINE CONSULTATION

- CONTACT ME

- LAB RESULTS

- ePRESCRIPTIONS

- eREFERRALS

- RECORD RELEASE

- MEDICAL SCRIBE

- PHYSICIAN ASSISTANT (PA)

- Medicare Annual Wellness Visit

- Case management/Social work

- Quality Care Measures

- Emergency closing notice

- FEEDBACK

- Talking to your doctor

- Choosing..... and losing a doctor

- INDEX A - Z

- ALLERGIC REACTIONS

- Alternative Medicine

- Alzheimer's Disease

- Bladder Problems

- Blood disorders

- Cancer Concerns

- GENETIC TESTING FOR HEREDITARY CANCER

- Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

- Controversial Concerns

- CPR : Learn and save a life

- CRP : Inflammatory marker

- Diabetes Management

- Dizziness, Vertigo,Tinnitus and Hearing Loss

- EXERCISE

- FEMALE HEALTH

-

GASTROINTESTINAL topics

- Appendicitis

- BRAT diet

- Celiac Disease or Sprue

- Crohn's Disease

- Gastroenterologists for Colon Cancer Screening

- Colonoscopy PREP

- Constipation

- Gluten sensitivity, but not celiac disease

- Heartburn and GERD

- Hemorrhoids and Anal fissure

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- NASH : Non Alcoholic Steato Hepatitis

- FEET PROBLEMS

- HEART RELATED topics

-

INFECTIOUS DISEASES

- Antibiotic Resistance

- Cat bites >

- Clostridia difficile infection - the "antibiotic associated germ"

- CORONA VIRUS

- Dengue Fever and Chikungunya Fever

- Food borne illnesses

- Shingles Vaccine

- Hepatitis B

- Hepatitis C

- Herpes

- Influenza

- Helicobacter pylori - the "ulcer germ"

- HIV Screening

- Lyme and other tick borne diseases

- Measles

- Meningitis

- MRSA (Staph infection)

- Norovirus

- Sexually Transmitted Diseases

- Shingles (Herpes Zoster)

- Sinusitis

- West Nile Virus

- Whooping Cough (Pertussis)

- Zika virus and pregnancy

- INSURANCE related topics

- KIDNEY STONES

- LEG CRAMPS

- LIBRARY for patients

- LIFE DECISIONS

- MALE HEALTH

- Medication/Drug side effects

- MEDICAL MARIJUANA

- MENTAL HEALTH

- Miscellaneous Articles

-

NUTRITION - EXERCISE - WEIGHT

- Cholesterol : New guidelines for treatment

- Advice to lower your cholesterol

- Cholesterol : Control

- Cholesterol : Raising your HDL Level

- Exercise

- Food : Making Smart Choices

- Food : Making Poor Choices

- Food : Grape Fruit and Drug Interaction

- Food : Vitamins, Minerals and Supplements

- Omega 3 fatty acids

- Vitamin B12 deficiency

- Vitamin D

- Weight Loss

- ORTHOPEDICS

- PAIN

- PATIENTS' RIGHTS

- SKIN

- SLEEP

- SMOKING

- STROKE

- THYROID

- SUBSTANCE ABUSE

- Travel and Vaccination

- TREMOR

- Warfarin Anticoagulation

- OTHER STUFF FOLLOWS

- Fact or Opinion?

- Hippocratic Oath

- FREE ADVICE.......for what its worth!

- LAUGHTER.....is the best medicine

- Physicians Pet Peeves

- PHOTO ALBUM - its not all work!

- Cape Town, South Africa

- Tribute page

- The 100 Club

- Free Wi-Fi

Cholesterol : How to raise your HDL level

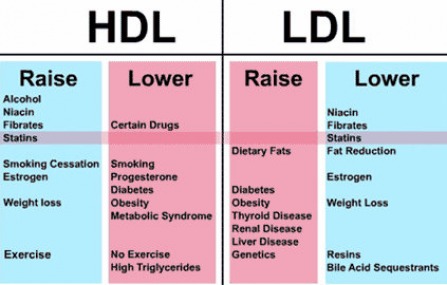

HDL cholesterol (the good cholesterol) helps to prevent our arteries from becoming blocked due to LDL (the bad cholesterol). It does this by "hauling" away the excess cholesterol lining the walls of our blood vessels, then bringing it back to the liver for reprocessing. This in turn helps to keep our arteries clear from a sticky build-up. And, if your levels of HDL are high enough (a level of 40 and above in males, 50 and above in females), it can also decrease your risk for a heart attack.

Raising HDL levels is important because for every one-point increase in HDL, there is a 3 percent decrease in a person's risk of suffering a fatal heart attack. There are two main ways to increase these levels: lifestyle modifications and medication therapy.

Lifestyle Modifications:

Medication Therapy:

Doubt Cast on the ‘Good’ in

‘Good Cholesterol’

By Gina Kolata : NY Times : May 16, 2012

The name alone sounds so encouraging: HDL, the “good cholesterol.” The more of it in your blood, the lower your risk of heart disease. So bringing up HDL levels has got to be good for health.

Or so the theory went.

Now, a new study that makes use of powerful databases of genetic information has found that raising HDL levels may not make any difference to heart disease risk. People who inherit genes that give them naturally higher HDL levels throughout life have no less heart disease than those who inherit genes that give them slightly lower levels. If HDL were protective, those with genes causing higher levels should have had less heart disease.

Researchers not associated with the study, published online Wednesday in The Lancet, found the results compelling and disturbing. Companies are actively developing and testing drugs that raise HDL, although three recent studies of such treatments have failed. And patients with low HDL levels are often told to try to raise them by exercising or dieting or even by taking niacin, which raised HDL but failed to lower heart disease risk in a recent clinical trial.

“I’d say the HDL hypothesis is on the ropes right now,” said Dr. James A. de Lemos, a professor at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, who was not involved in the study.

Dr. Michael Lauer, director of the division of cardiovascular sciences at the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, agreed.

“The current study tells us that when it comes to HDL we should seriously consider going back to the drawing board, in this case meaning back to the laboratory,” said Dr. Lauer, who also was not connected to the research. “We need to encourage basic laboratory scientists to figure out where HDL fits in the puzzle — just what exactly is it a marker for.”

But Dr. Steven Nissen, chairman of cardiovascular medicine at the Cleveland Clinic, who is helping conduct studies of HDL-raising drugs, said he remained hopeful. HDL is complex, he said, and it is possible that some types of HDL molecules might in fact protect against heart disease.

“I am an optimist,” Dr. Nissen said.

The study’s authors emphasize that they are not questioning the well-documented finding that higher HDL levels are associated with lower heart disease risk. But the relationship may not be causative. Many assumed it was because the association was so strong and consistent. Researchers also had a hypothesis to explain how HDL might work. From studies with mice and with cells grown in the laboratory, they proposed that HDL ferried cholesterol out of arteries where it did not belong.

Now it seems that instead of directly reducing heart disease risk, high HDL levels may be a sign that something else is going on that makes heart disease less likely. To investigate the relationship between HDL and cardiovascular risk, the researchers, led by Dr. Sekar Kathiresan, director of preventive cardiology at Massachusetts General Hospital and a geneticist at the Broad Institute of M.I.T. and Harvard, used a method known as Mendelian randomization. It is a study design that has recently become feasible with the advent of quick and lower-cost genetic analyses.

The idea is that people inherit any of a wide variety of genetic variations that determine how much HDL they produce. The result is that people are naturally and randomly assigned by these variations in their inherited genes to make more, or less, HDL, throughout their lives. If HDL reduces the risk of heart disease, then those who make more should be at lower risk.

For purposes of comparison, the researchers also examined inherited variations in 13 genes that determine levels of LDL, the so-called bad cholesterol. It is well known and widely accepted that lowering LDL levels by any means — diet and exercise, statin drugs — reduces risk. Clinical trials with statins established with certainty that reducing LDL levels is protective. So, the researchers asked, did people who inherited gene variations that affected their LDL levels, have correspondingly higher or lower heart disease risk?

The study found, as expected, that gene variations that raise LDL increase risk and those that lower LDL decrease risk. The gene effects often were tiny, altering LDL levels by only a few percent. But the data, involving tens of thousands of people, clearly showed effects on risk.

“That speaks to how powerful LDL is,” Dr. Kathiresan said.

But the HDL story was very different. First the investigators looked at variations in a well-known gene, endothelial lipase, that affects only HDL. About 2.6 percent of the population has a variation in that gene that raises their HDL levels by about 6 points. The investigators looked at 116,000 people, asking if they had the variant and if those who carried the HDL-raising variant had lower risk for heart disease.

“We found absolutely no association between the HDL-boosting variant and risk for heart disease,” Dr. Kathiresan said. “That was very surprising to us.”

Then they looked at a group of 14 gene variants that also affect HDL levels, asking if there was a relationship between these variants and risk for heart disease. The data included genetic data on 53,500 people. Once again, there was no association between having the variants that increased HDL and risk of heart disease.

Dr. Lauer explains what that means with an analogy.

“One might think of a highway accident that causes a massive traffic jam,” he said. “Stewing in the jam many miles away, I might be tempted to strike the sign that says ‘accident ahead,’ but that won’t do any good. The ‘accident-ahead’ sign is not the cause of the traffic jam — the accident is. Analogously, targeting HDL won’t help if it’s merely a sign.”

Dr. Kathiresan said there were many things HDL might indicate. “The number of factors that track with low HDL is a mile long,” he said. “Obesity, being sedentary, smoking, insulin resistance, having small LDL particles, having increased cholesterol in remnant particles, and having increased amounts of coagulation factors in the blood,” he said. “Our hypothesis is that much of the association may be due to these other factors.”

“I often see patients in the clinic with low HDL levels who ask how they can raise it,” Dr. Kathiresan said. “I tell them, ‘It means you are at increased risk, but I don’t know if raising it will affect your risk.’ ”

That often does not go over well, he added. The notion that HDL is protective is so entrenched that the study’s conclusions may prove hard to accept, he and other researchers said.

“When people see numbers in the abnormal range they want to do something about it,” Dr. Kathiresan said. “It is very hard to get across the concept that the safest thing might be to leave people alone.”

Raising HDL levels is important because for every one-point increase in HDL, there is a 3 percent decrease in a person's risk of suffering a fatal heart attack. There are two main ways to increase these levels: lifestyle modifications and medication therapy.

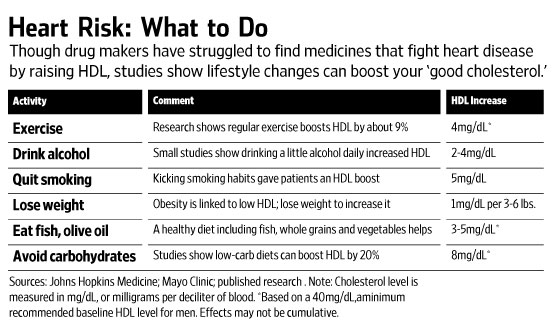

Lifestyle Modifications:

- Exercise. Just 20-30 minutes of aerobic exercise on most days of the week can jump-start your HDL in the right direction.

- Break the tobacco habit. Quitting smoking can raise your HDL levels by about four points.

- Lose weight. Losing 10 pounds can increase your HDL by one and a half points. Aim for a weight loss goal to achieve a body mass index (BMI) of 25 or below.

- Choose the better fat. Minimize the saturated and trans fats in your diet. These substances increase the bad cholesterol while decreasing your good cholesterol. Instead, switch to products containing unsaturated fats (olive, canola, flaxseed, etc.). These may raise your HDL levels. However, this is not a free fatty-pass, because we still have to watch the calories!

- Cut back on simple carbohydrates. Cakes, cookies and highly processed cereals and breads are high-glycemic foods that can lower your HDL and raise the levels of another fat in your bloodstream, triglycerides.

- Drink alcohol in moderation, with a caveat! Alcohol should not be considered medicine—if you don't drink, don't start—but some studies have found mild alcohol consumption (one drink per day for women, two for men) can raise HDL by up to four points. Important caveat: Alcohol may be harmful to those with liver or addiction problems. In these cases, the risks certainly outweigh the benefits.

- Feast on cold-water fish. Eating salmon, mackerel or other fish from icy waters several times a week can have a very positive effect on your HDL levels. They contain omega-3 fatty acids, which may help to explain their health benefits.

- Add fiber. The soluble fiber found in fruits, vegetables, nuts and grains might boost your HDL.

- Avoid anabolic steroids. These decrease your HDL levels, in addition to all their other potential health dangers.

Medication Therapy:

- Niacin, which is also known as nicotinic acid or vitamin B3. This is by far and away our best therapy for raising HDL levels. Studies have shown increases of 20 percent to 35 percent. Unfortunately, every rose has its thorn, and niacin has a big one called side effects (flushing, racing heart, etc). Niaspan, a long acting form of niacin, has a significantly lower incidence of flushing, especially if taken at bedtime with a light snack and if an aspirin is taken an hour before the dose.

- Fibrates, specifically fenofibrate, has the potential to boost your HDL by up to 20 percent. Side effects may include upset stomach and diarrhea.

- Statins. These are better known for their remarkable ability to lower the harmful LDL cholesterol. However, certain drugs within this class (atorvastatin, rosuvastatin and simvastatin) can raise HDL by up to 15 percent.

Doubt Cast on the ‘Good’ in

‘Good Cholesterol’

By Gina Kolata : NY Times : May 16, 2012

The name alone sounds so encouraging: HDL, the “good cholesterol.” The more of it in your blood, the lower your risk of heart disease. So bringing up HDL levels has got to be good for health.

Or so the theory went.

Now, a new study that makes use of powerful databases of genetic information has found that raising HDL levels may not make any difference to heart disease risk. People who inherit genes that give them naturally higher HDL levels throughout life have no less heart disease than those who inherit genes that give them slightly lower levels. If HDL were protective, those with genes causing higher levels should have had less heart disease.

Researchers not associated with the study, published online Wednesday in The Lancet, found the results compelling and disturbing. Companies are actively developing and testing drugs that raise HDL, although three recent studies of such treatments have failed. And patients with low HDL levels are often told to try to raise them by exercising or dieting or even by taking niacin, which raised HDL but failed to lower heart disease risk in a recent clinical trial.

“I’d say the HDL hypothesis is on the ropes right now,” said Dr. James A. de Lemos, a professor at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, who was not involved in the study.

Dr. Michael Lauer, director of the division of cardiovascular sciences at the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, agreed.

“The current study tells us that when it comes to HDL we should seriously consider going back to the drawing board, in this case meaning back to the laboratory,” said Dr. Lauer, who also was not connected to the research. “We need to encourage basic laboratory scientists to figure out where HDL fits in the puzzle — just what exactly is it a marker for.”

But Dr. Steven Nissen, chairman of cardiovascular medicine at the Cleveland Clinic, who is helping conduct studies of HDL-raising drugs, said he remained hopeful. HDL is complex, he said, and it is possible that some types of HDL molecules might in fact protect against heart disease.

“I am an optimist,” Dr. Nissen said.

The study’s authors emphasize that they are not questioning the well-documented finding that higher HDL levels are associated with lower heart disease risk. But the relationship may not be causative. Many assumed it was because the association was so strong and consistent. Researchers also had a hypothesis to explain how HDL might work. From studies with mice and with cells grown in the laboratory, they proposed that HDL ferried cholesterol out of arteries where it did not belong.

Now it seems that instead of directly reducing heart disease risk, high HDL levels may be a sign that something else is going on that makes heart disease less likely. To investigate the relationship between HDL and cardiovascular risk, the researchers, led by Dr. Sekar Kathiresan, director of preventive cardiology at Massachusetts General Hospital and a geneticist at the Broad Institute of M.I.T. and Harvard, used a method known as Mendelian randomization. It is a study design that has recently become feasible with the advent of quick and lower-cost genetic analyses.

The idea is that people inherit any of a wide variety of genetic variations that determine how much HDL they produce. The result is that people are naturally and randomly assigned by these variations in their inherited genes to make more, or less, HDL, throughout their lives. If HDL reduces the risk of heart disease, then those who make more should be at lower risk.

For purposes of comparison, the researchers also examined inherited variations in 13 genes that determine levels of LDL, the so-called bad cholesterol. It is well known and widely accepted that lowering LDL levels by any means — diet and exercise, statin drugs — reduces risk. Clinical trials with statins established with certainty that reducing LDL levels is protective. So, the researchers asked, did people who inherited gene variations that affected their LDL levels, have correspondingly higher or lower heart disease risk?

The study found, as expected, that gene variations that raise LDL increase risk and those that lower LDL decrease risk. The gene effects often were tiny, altering LDL levels by only a few percent. But the data, involving tens of thousands of people, clearly showed effects on risk.

“That speaks to how powerful LDL is,” Dr. Kathiresan said.

But the HDL story was very different. First the investigators looked at variations in a well-known gene, endothelial lipase, that affects only HDL. About 2.6 percent of the population has a variation in that gene that raises their HDL levels by about 6 points. The investigators looked at 116,000 people, asking if they had the variant and if those who carried the HDL-raising variant had lower risk for heart disease.

“We found absolutely no association between the HDL-boosting variant and risk for heart disease,” Dr. Kathiresan said. “That was very surprising to us.”

Then they looked at a group of 14 gene variants that also affect HDL levels, asking if there was a relationship between these variants and risk for heart disease. The data included genetic data on 53,500 people. Once again, there was no association between having the variants that increased HDL and risk of heart disease.

Dr. Lauer explains what that means with an analogy.

“One might think of a highway accident that causes a massive traffic jam,” he said. “Stewing in the jam many miles away, I might be tempted to strike the sign that says ‘accident ahead,’ but that won’t do any good. The ‘accident-ahead’ sign is not the cause of the traffic jam — the accident is. Analogously, targeting HDL won’t help if it’s merely a sign.”

Dr. Kathiresan said there were many things HDL might indicate. “The number of factors that track with low HDL is a mile long,” he said. “Obesity, being sedentary, smoking, insulin resistance, having small LDL particles, having increased cholesterol in remnant particles, and having increased amounts of coagulation factors in the blood,” he said. “Our hypothesis is that much of the association may be due to these other factors.”

“I often see patients in the clinic with low HDL levels who ask how they can raise it,” Dr. Kathiresan said. “I tell them, ‘It means you are at increased risk, but I don’t know if raising it will affect your risk.’ ”

That often does not go over well, he added. The notion that HDL is protective is so entrenched that the study’s conclusions may prove hard to accept, he and other researchers said.

“When people see numbers in the abnormal range they want to do something about it,” Dr. Kathiresan said. “It is very hard to get across the concept that the safest thing might be to leave people alone.”

New Rules for Giving Good Cholesterol a Boost

By Christopher Weaver : WSJ : January 7, 2012

In the war against heart-damaging high cholesterol, a promising weapon has been largely neutralized.

A string of recent clinical studies, including a major Merck & Co. trial that began in 2007 and was canceled last month, have shown medicines that raise "good cholesterol" to be no more effective at warding off heart disease than widely used "bad-cholesterol"-cutting drugs alone.

A recent clinical trial showing the B vitamin niacin didn't reduce heart-health risks compared with standard treatment has doctors wondering why they've prescribed other versions of the drug to millions for decades with little evidence to support its effectiveness. WSJ's Christopher Weaver and Dr. Stephen Kopecky, cardiologist at Mayo Clinic, join Lunch Break with details. Photo: Getty Images.

This has left researchers grappling with a riddle: Low levels of high-density lipoprotein, or so-called good cholesterol, have long been shown as a predictor of heart disease, since HDLs help ferry bad cholesterol away from artery walls to the liver. But even with drugs such as niacin—which raised HDL levels 18 percentage points more than a placebo in an early trial that supported its FDA approval—studies now show it hasn't reduced the odds of falling ill when bad cholesterol is in check.

Now, some scientists theorize that the problem lies not in trying to raise HDL, but specifically in the approaches current medications take to raising it.

These findings cast dark clouds over what many scientists have long seen as the next-most promising avenue of cholesterol treatment after statin drugs, which slash the "bad" cholesterol that accumulates in the arteries. Pfizer Inc.'s well-known statin Lipitor, now generic, reduced the risk of heart attacks by one-third in studies. Doctors and researchers hoped boosting HDL would go a long way toward limiting remaining risk.

In the Merck study, researchers found adding HDL-boosting niacin to a statin didn't prevent heart attacks any more effectively than a statin alone.

"The statin story has been one of the triumphs of medicine, but it was not a cure," says Jorge Plutzky, a cardiologist and researcher at Brigham and Women's Hospital in Boston, noting that people on the drug still suffer heart attacks.

Niacin, a naturally occurring B vitamin, is prescribed for heart-health conditions. Side effects are usually minimal, often limited to facial flushing. In very rare cases, high dosages have been linked to liver toxicity.

Jack Kutner, one of Dr. Plutzky's patients, took a big dose of niacin each day for more than two decades—in part because of his family's history of fatal heart attacks. But when the 55-year-old retired financial services executive from Cambridge, Mass., reviewed the recent research with Dr. Plutzky, he says they concluded the niacin wasn't doing anything to lower his heart risk and that his cholesterol was well controlled on the statin Crestor. "We figured we'd just get rid of it," says Mr. Kutner.

Dr. Plutzky says he is disappointed by the failure of niacin in recent trials, especially given its promise. "One of the great hopes to bring down residual risks in the post-statin era is by raising HDL," he says, but the data beg the question, "where do we go from here?"

Indeed, research has long shown that people with high HDL levels face fewer heart attacks. A nonsmoking 55-year-old man with normal blood pressure and high HDL—60 or greater—faces a 4% 10-year chance of heart disease, about one-third less than an identical patient with HDL below 30, according to the Framingham Risk Score, a widely used heart-health assessment based on a decades-long longitudinal study.

But drug-industry attempts to artificially inflate HDL have fallen short. In addition to Merck's recent study for a drug called Tredaptive, Roche Holding AG halted a study for an HDL-raising drug known as CETP inhibitor in May when researchers realized it wasn't working. Pfizer canceled a similar study in 2006. And last year, National Institutes of Health-funded research showed niacin didn't improve results for patients already taking statins.

The Merck study "showed a real question mark in the therapeutic marker," said Roger Newton, chief science officer of drug firm Esperion, and a discoverer of Lipitor. Researchers theorize that medically elevated HDL may not be as effective as natural HDL at whisking away bad cholesterol. "Not all HDL are created the same," he said.

But little is known about what makes an effective HDL particle versus a stunted, useless one, Dr. Newton says. While Esperion is working on an HDL-boosting treatment, "we're focusing most of our energies and finances" on a new LDL-lowering medicine, he says.

That leaves patients seeking a heart-health booster beyond statins with old-fashioned lifestyle methods such as diet and exercise. "If you raise HDL in non-pharmacologic ways, it really does help you," says Steve Kopecky, a Mayo Clinic cardiologist. "We always assumed it was HDL" that decreased heart-disease risk, he says. "But maybe it was the exercise that did it, or the not smoking that did it," he says.

Doctors advise routine exercise along with a healthy diet featuring vegetables, fruits, nuts and whole grains. High-sugar diets, obesity and smoking all lower HDL, while moderate drinking—a glass of wine a night, for instance—can raise it. Mr. Kutner, in Cambridge, says his HDL, aided by daily exercise and efforts to avoid foods such as red meat, had reached 38 without niacin, a lifetime record.

"Let's pay at least as much attention to nutrition as we do [to] drugs," says Stephen Devries, a Northwestern Medicine cardiologist and director of the Gaples Institute, a nonprofit that promotes heart health. "There's a big focus on drugs, partly because no one is making a lot of money selling nuts."

But for many patients drugs are easier. "I know I should get at least 30 minutes of physical activity in every day," says Christopher Edginton, a 66-year-old professor of leisure services at the University of Northern Iowa who took niacin for several years. But "I don't always do it," he says.

Researchers who hope for a successful, HDL-raising drug now say they worry pharmaceutical companies may not revisit the approach. Drug maker AbbVie Inc., will lose patent protection for its $900 million-a-year niacin-based drug Niaspan in 2013, and has no incentive to fund further research.

Sales of prescription niacin, marketed by AbbVie, and over-the-counter B vitamin pills which often contain lower doses, reached more than $2 billion in combined U.S. sales last year, according to company filings and data firm Euromonitor.

Merck says it remains hopeful about its own CETP inhibitor now in clinical trials, but declined to discuss details of the Tredaptive study pending full publication of the results. Tredaptive included niacin, a statin and another drug meant to reduce the flushing side effect of niacin.

William Boden, chief of medicine at Samuel S. Stratton VA Medical Center in Albany, N.Y., and a principal investigator in the NIH-funded niacin study, says a well-designed niacin study may show the drug has benefits for certain patients, such as those with very low HDL, but "the question is now, who would fund it?"

Still, "no one is refuting the epidemiology" that shows low HDL predicts heart risk, Dr. Boden says: "I still believe in the HDL hypothesis."

By Christopher Weaver : WSJ : January 7, 2012

In the war against heart-damaging high cholesterol, a promising weapon has been largely neutralized.

A string of recent clinical studies, including a major Merck & Co. trial that began in 2007 and was canceled last month, have shown medicines that raise "good cholesterol" to be no more effective at warding off heart disease than widely used "bad-cholesterol"-cutting drugs alone.

A recent clinical trial showing the B vitamin niacin didn't reduce heart-health risks compared with standard treatment has doctors wondering why they've prescribed other versions of the drug to millions for decades with little evidence to support its effectiveness. WSJ's Christopher Weaver and Dr. Stephen Kopecky, cardiologist at Mayo Clinic, join Lunch Break with details. Photo: Getty Images.

This has left researchers grappling with a riddle: Low levels of high-density lipoprotein, or so-called good cholesterol, have long been shown as a predictor of heart disease, since HDLs help ferry bad cholesterol away from artery walls to the liver. But even with drugs such as niacin—which raised HDL levels 18 percentage points more than a placebo in an early trial that supported its FDA approval—studies now show it hasn't reduced the odds of falling ill when bad cholesterol is in check.

Now, some scientists theorize that the problem lies not in trying to raise HDL, but specifically in the approaches current medications take to raising it.

These findings cast dark clouds over what many scientists have long seen as the next-most promising avenue of cholesterol treatment after statin drugs, which slash the "bad" cholesterol that accumulates in the arteries. Pfizer Inc.'s well-known statin Lipitor, now generic, reduced the risk of heart attacks by one-third in studies. Doctors and researchers hoped boosting HDL would go a long way toward limiting remaining risk.

In the Merck study, researchers found adding HDL-boosting niacin to a statin didn't prevent heart attacks any more effectively than a statin alone.

"The statin story has been one of the triumphs of medicine, but it was not a cure," says Jorge Plutzky, a cardiologist and researcher at Brigham and Women's Hospital in Boston, noting that people on the drug still suffer heart attacks.

Niacin, a naturally occurring B vitamin, is prescribed for heart-health conditions. Side effects are usually minimal, often limited to facial flushing. In very rare cases, high dosages have been linked to liver toxicity.

Jack Kutner, one of Dr. Plutzky's patients, took a big dose of niacin each day for more than two decades—in part because of his family's history of fatal heart attacks. But when the 55-year-old retired financial services executive from Cambridge, Mass., reviewed the recent research with Dr. Plutzky, he says they concluded the niacin wasn't doing anything to lower his heart risk and that his cholesterol was well controlled on the statin Crestor. "We figured we'd just get rid of it," says Mr. Kutner.

Dr. Plutzky says he is disappointed by the failure of niacin in recent trials, especially given its promise. "One of the great hopes to bring down residual risks in the post-statin era is by raising HDL," he says, but the data beg the question, "where do we go from here?"

Indeed, research has long shown that people with high HDL levels face fewer heart attacks. A nonsmoking 55-year-old man with normal blood pressure and high HDL—60 or greater—faces a 4% 10-year chance of heart disease, about one-third less than an identical patient with HDL below 30, according to the Framingham Risk Score, a widely used heart-health assessment based on a decades-long longitudinal study.

But drug-industry attempts to artificially inflate HDL have fallen short. In addition to Merck's recent study for a drug called Tredaptive, Roche Holding AG halted a study for an HDL-raising drug known as CETP inhibitor in May when researchers realized it wasn't working. Pfizer canceled a similar study in 2006. And last year, National Institutes of Health-funded research showed niacin didn't improve results for patients already taking statins.

The Merck study "showed a real question mark in the therapeutic marker," said Roger Newton, chief science officer of drug firm Esperion, and a discoverer of Lipitor. Researchers theorize that medically elevated HDL may not be as effective as natural HDL at whisking away bad cholesterol. "Not all HDL are created the same," he said.

But little is known about what makes an effective HDL particle versus a stunted, useless one, Dr. Newton says. While Esperion is working on an HDL-boosting treatment, "we're focusing most of our energies and finances" on a new LDL-lowering medicine, he says.

That leaves patients seeking a heart-health booster beyond statins with old-fashioned lifestyle methods such as diet and exercise. "If you raise HDL in non-pharmacologic ways, it really does help you," says Steve Kopecky, a Mayo Clinic cardiologist. "We always assumed it was HDL" that decreased heart-disease risk, he says. "But maybe it was the exercise that did it, or the not smoking that did it," he says.

Doctors advise routine exercise along with a healthy diet featuring vegetables, fruits, nuts and whole grains. High-sugar diets, obesity and smoking all lower HDL, while moderate drinking—a glass of wine a night, for instance—can raise it. Mr. Kutner, in Cambridge, says his HDL, aided by daily exercise and efforts to avoid foods such as red meat, had reached 38 without niacin, a lifetime record.

"Let's pay at least as much attention to nutrition as we do [to] drugs," says Stephen Devries, a Northwestern Medicine cardiologist and director of the Gaples Institute, a nonprofit that promotes heart health. "There's a big focus on drugs, partly because no one is making a lot of money selling nuts."

But for many patients drugs are easier. "I know I should get at least 30 minutes of physical activity in every day," says Christopher Edginton, a 66-year-old professor of leisure services at the University of Northern Iowa who took niacin for several years. But "I don't always do it," he says.

Researchers who hope for a successful, HDL-raising drug now say they worry pharmaceutical companies may not revisit the approach. Drug maker AbbVie Inc., will lose patent protection for its $900 million-a-year niacin-based drug Niaspan in 2013, and has no incentive to fund further research.

Sales of prescription niacin, marketed by AbbVie, and over-the-counter B vitamin pills which often contain lower doses, reached more than $2 billion in combined U.S. sales last year, according to company filings and data firm Euromonitor.

Merck says it remains hopeful about its own CETP inhibitor now in clinical trials, but declined to discuss details of the Tredaptive study pending full publication of the results. Tredaptive included niacin, a statin and another drug meant to reduce the flushing side effect of niacin.

William Boden, chief of medicine at Samuel S. Stratton VA Medical Center in Albany, N.Y., and a principal investigator in the NIH-funded niacin study, says a well-designed niacin study may show the drug has benefits for certain patients, such as those with very low HDL, but "the question is now, who would fund it?"

Still, "no one is refuting the epidemiology" that shows low HDL predicts heart risk, Dr. Boden says: "I still believe in the HDL hypothesis."