- RETIREMENT ANNOUNCEMENT

- HOME PAGE

- "MYCHART" the new patient portal

- BELMONT MEDICAL ASSOCIATES

- MOUNT AUBURN HOSPITAL

- EMERGENCIES

- PRACTICE PHILOSOPHY

- MY RESUME

- TELEMEDICINE CONSULTATION

- CONTACT ME

- LAB RESULTS

- ePRESCRIPTIONS

- eREFERRALS

- RECORD RELEASE

- MEDICAL SCRIBE

- PHYSICIAN ASSISTANT (PA)

- Medicare Annual Wellness Visit

- Case management/Social work

- Quality Care Measures

- Emergency closing notice

- FEEDBACK

- Talking to your doctor

- Choosing..... and losing a doctor

- INDEX A - Z

- ALLERGIC REACTIONS

- Alternative Medicine

- Alzheimer's Disease

- Bladder Problems

- Blood disorders

- Cancer Concerns

- GENETIC TESTING FOR HEREDITARY CANCER

- Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

- Controversial Concerns

- CPR : Learn and save a life

- CRP : Inflammatory marker

- Diabetes Management

- Dizziness, Vertigo,Tinnitus and Hearing Loss

- EXERCISE

- FEMALE HEALTH

-

GASTROINTESTINAL topics

- Appendicitis

- BRAT diet

- Celiac Disease or Sprue

- Crohn's Disease

- Gastroenterologists for Colon Cancer Screening

- Colonoscopy PREP

- Constipation

- Gluten sensitivity, but not celiac disease

- Heartburn and GERD

- Hemorrhoids and Anal fissure

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- NASH : Non Alcoholic Steato Hepatitis

- FEET PROBLEMS

- HEART RELATED topics

-

INFECTIOUS DISEASES

- Antibiotic Resistance

- Cat bites >

- Clostridia difficile infection - the "antibiotic associated germ"

- CORONA VIRUS

- Dengue Fever and Chikungunya Fever

- Food borne illnesses

- Shingles Vaccine

- Hepatitis B

- Hepatitis C

- Herpes

- Influenza

- Helicobacter pylori - the "ulcer germ"

- HIV Screening

- Lyme and other tick borne diseases

- Measles

- Meningitis

- MRSA (Staph infection)

- Norovirus

- Sexually Transmitted Diseases

- Shingles (Herpes Zoster)

- Sinusitis

- West Nile Virus

- Whooping Cough (Pertussis)

- Zika virus and pregnancy

- INSURANCE related topics

- KIDNEY STONES

- LEG CRAMPS

- LIBRARY for patients

- LIFE DECISIONS

- MALE HEALTH

- Medication/Drug side effects

- MEDICAL MARIJUANA

- MENTAL HEALTH

- Miscellaneous Articles

-

NUTRITION - EXERCISE - WEIGHT

- Cholesterol : New guidelines for treatment

- Advice to lower your cholesterol

- Cholesterol : Control

- Cholesterol : Raising your HDL Level

- Exercise

- Food : Making Smart Choices

- Food : Making Poor Choices

- Food : Grape Fruit and Drug Interaction

- Food : Vitamins, Minerals and Supplements

- Omega 3 fatty acids

- Vitamin B12 deficiency

- Vitamin D

- Weight Loss

- ORTHOPEDICS

- PAIN

- PATIENTS' RIGHTS

- SKIN

- SLEEP

- SMOKING

- STROKE

- THYROID

- SUBSTANCE ABUSE

- Travel and Vaccination

- TREMOR

- Warfarin Anticoagulation

- OTHER STUFF FOLLOWS

- Fact or Opinion?

- Hippocratic Oath

- FREE ADVICE.......for what its worth!

- LAUGHTER.....is the best medicine

- Physicians Pet Peeves

- PHOTO ALBUM - its not all work!

- Cape Town, South Africa

- Tribute page

- The 100 Club

- Free Wi-Fi

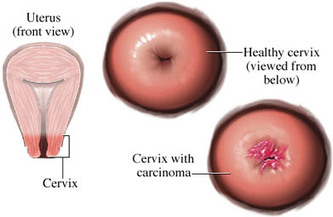

Cervical Cancer

Cervical Cancer Screening

Pap testing and HPV screening

The Food and Drug Administration has approved a new screening test for cervical cancer that could help distinguish women at increased risk from those at very low risk of developing the disease. Women over age 30 can now receive a test for human papilloma virus or HPV, at the same time they receive a Pap test.

The HPV test, manufactured by Digene Corp. of Gaithersburg, Maryland, is already approved to detect HPV in women with abnormal Pap smears, but until now, it was not approved for screening purposes, before results of the Pap test were known.

Since March, 2000, the test has been used for women whose Pap tests show mild abnormalities that can't be readily explained, a condition referred to as Atypical Squamous Cells of Unknown Origin, or ASC-US. Until then, such women had to undergo repeated Pap smears every few months in hopes of determining the nature of the abnormal cells? Whether they might develop into precancerous lesions or clear up on their own. In some cases, a colposcopy ? An examination of the cervix with magnifying binoculars - was used to select areas of the cervix to biopsy, to determine whether the cells were dangerous. Women with ASC-US Pap results who have negative HPV test results could be reassured that their short term risk of developing cervical cancer was very low, and that they could safely return to the usual screening schedule.

HPV is a family of more than 100 extremely common viruses, of which about 30 are sexually transmitted. Of these, about a dozen "high-risk" varieties are linked to nearly all cervical cancers, and to some cases of vaginal, vulvar, anal, and penile cancers. Other, "low-risk" varieties cause genital warts. In most cases, however, HPV infection causes no symptoms at all, so a person who has HPV might not even know it. In other cases, symptoms of HPV do not appear until years after infection.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 50%-75% of sexually active adults will harbor the virus at some point in their life. In most cases, the immune system defeats the virus with no permanent effects. Sometimes, though, HPV that lingers in the body causes changes in the cervix that are detected with a Pap smear. In rare cases, these changes lead to cancer.

The risk of HPV progressing causing changes that could lead to cancer is greater for women over age 30 than for younger women, said Debbie Saslow, PhD, director of breast and gynecologic cancer programs for ACS, which is why the new screening test isn't recommended for younger women. HPV infections in younger women tend to go away by themselves.

"In a woman over 30," Saslow said, "if [an HPV infection] hasn't cleared in a year, you want to do additional testing. It doesn't mean she's going to get cancer, but you want to follow her and watch her more carefully" to see if any treatment is needed.

The FDA said women who have an abnormal Pap test and an HPV infection have a 6% to 7% greater risk of developing cervical cancer if they aren't treated.

Still, cervical cancer is rare even among women who do have an HPV infection. The American Cancer Society estimates about 12,200 new cases of cervical cancer will be diagnosed this year. Screening can help prevent the disease by catching abnormalities in the cervix before they become cancerous. The Society recommends Pap tests beginning either at age 21 or three years after a woman first has sexual intercourse. Until age 30, screening should be done every year with the regular Pap test or every two years using the newer liquid-based Pap test. After age 30, women who have had three normal Pap tests in a row can wait two or three years for their next Pap.

"It's important to get screened," Saslow said, and even HPV-negative women should follow the recommended schedule. The FDA said the new use of the HPV test is in addition to Pap tests. The HPV test is not a substitute for regular Pap tests.

Cervical Cancer Vaccine Remains Underused

By Carol Weeg : NY Times Article : July 25, 2008

In Brief:

By getting vaccinated for human papillomavirus, or HPV, before she becomes sexually active, a girl reduces her lifetime risk of developing cervical cancer by 70 percent, studies suggest.

Fewer than one in four eligible girls and women, ages 9 to 26, has been vaccinated against HPV.

The HPV vaccine remains controversial, despite some studies showing its safety and effectiveness.

One in four American girls and women ages 14 to 19 has a sexually transmitted disease, and one in four ages 14 to 59 is infected with HPV.

Preventing cervical cancer may be the last thing on the mind of the average 11-year-old girl. But by getting vaccinated for human papillomavirus, or HPV, the virus that causes nearly all cases of cervical cancer, a girl reduces her lifetime risk of developing the disease by 70 percent, studies suggest.

The vaccine, called Gardasil and made by Merck, protects against the two types of HPV — 16 and 18 — responsible for most cervical cancers, the second leading cancer killer among women worldwide. It also immunizes against HPV 6 and 11, the types of the virus that cause 90 percent of genital warts, which are not life-threatening but can be distressing and difficult to treat.

The federal Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommends vaccinating girls between the ages of 11 and 12, and as young as 9 at the discretion of doctors. It also advises that girls and women ages 13 to 26 receive the vaccine if they have not yet been immunized. But the vaccine is controversial, and only 24 percent of eligible girls and women have gotten at least one of the three recommended doses.

One reason for the controversy is that the vaccine is relatively new. The Food and Drug Administration approved it in 2006, and this leaves some parents, and doctors, questioning its long-term safety and efficacy.

“Studies have been done on fewer than 2,000 girls ages 10 to 15, and to know if a vaccine is safe, millions of people have to get it and have a chance to report any adverse events,” said Dr. Diane Harper, director of the Gynecologic Cancer Prevention Research Group at Dartmouth Medical School. “It’s a public health experiment, but that’s the nature of vaccines.”

Proponents counter by pointing to Gardasil’s track record. An estimated eight million girls and women in the United States have received one or more doses of the vaccine, with fewer than 7 percent reporting serious side effects — about half the rate for vaccines over all.

“There’s six years of safety data that shows no long-term risks, and that’s the same timeframe for other recently recommended vaccines,” said Dr. Mark H. Einstein, director of clinical research in the gynecologic oncology division of Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York.

Safety issues aside, some people oppose the vaccine because they fear that its use will encourage promiscuity. Or they have religious objections to vaccines, or argue that the government has no right to mandate its use, as some states have tried to do.

With or without the vaccine, many teenagers are already sexually active. A recent government study found that one in four girls ages 14 to 19 has a sexually transmitted disease. And one in four American girls and women ages 14 to 59 is infected with HPV, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “This vaccine is a preventive health measure, not a sex education measure,” Dr. Einstein said. “From a science standpoint, it completely makes sense to vaccinate girls against HPV.”

The vaccine is being studied for use in boys and men, too.

“We don’t have widespread vaccination of women, so immunizing men may help protect those women who aren’t vaccinated,” said Dr. Kevin Ault, associate professor of gynecology and obstetrics at Emory University Medical School in Atlanta. It would also protect men against genital warts, which they get at a higher rate than women, and may immunize against relatively rare HPV-related cancers of the penis, anus, neck and head.

Most HPV infections clear up on their own, but those that persist, usually for five years or longer, increase a woman’s risk for developing precancerous cervical lesions. Pap tests, a routine part of a gynecological exam, usually detect these precancers, which can be treated so they do not develop into cancer. Still, 11,000 new cases of cervical cancer are diagnosed in the United States every year, most in women who haven’t gotten regular Pap tests, but some in women whose Pap tests didn’t detect precancerous cells.

Fortunately, cervical cancer is slow-growing.

“Usually the time to progression from a premalignant lesion to an invasive cancer is about 10 years,” said Dr. Teresa Diaz-Montes, gynecologic oncologist at Johns Hopkins Medical Center. When caught early, which is usually the case in the United States, cervical cancer can often be treated and cured by a simple or radical hysterectomy. Survival rates are high. “If the tumor is confined to the cervix, the five-year survival rate will be 80 to over 95 percent,” Dr. Diaz-Montes said.

And women can improve their chance of survival by getting treated by gynecologic oncologists rather than general gynecologists, studies show.

“Cervical cancer is not as common now as it was in the past because of Pap tests, so it’s important to be seen by a gynecologic oncologist because these are the specialists trained to treat this disease,” Dr. Diaz-Montes said. She advises women to look for a physician who sees a high volume of patients that need the same type of treatment they require.

Still, 3,700 women die from cervical cancer in the United States every year. Experts say that doesn’t need to happen.

“By getting vaccinated early and having regular Pap tests, and HPV tests when her health care provider recommends them,” Dr. Einstein said, “a woman has the best chance of preventing what is by far one of the most preventable cancers we have.”

American Cancer Society Guidelines

HPV Vaccine

Girls should get the new vaccine for human papilloma virus (HPV) at age 11-12, the American Cancer Society says in new guidelines issued Friday.

HPV is a very common virus. Some types of HPV are sexually transmitted, and these can cause cervical cancer and other types of cancer, as well as genital warts.

The vaccine currently available, called Gardasil, protects against 2 types of HPV that cause about 70% of cervical cancers, and 2 other types that cause 90% of genital warts. It is given as a series of 3 shots over the course of 6 months. Other HPV vaccines are also being tested.

But screening will still be an important part of cervical cancer prevention, even in people who have been vaccinated, the guidelines say. They are published in the latest issue of the ACS journal CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians.

The complete ACS recommendations address several different groups:

Potential for Preventing Many Cervical Cancers

Cervical cancer screening with the Pap test has greatly reduced the incidence of this cancer in the United States. The greatest impact of the vaccine is likely to be in groups where screening levels are low, such as in medically underserved populations. The vaccine may prove especially helpful in other countries where cervical cancer screening is not routinely done.

Giving the vaccine to young girls is important, the new guidelines say, because it works best when given to people before they ever become infected with HPV. Because the types of HPV that cause cervical cancer are sexually transmitted, girls should get vaccinated well before they become sexually active.

Surveys of US teens show that nearly a quarter of them have had sex by age 15, and 70% have had sex by age 18.

Most people become infected with HPV at some point in their lives, but the infection usually clears up on its own without ever causing any symptoms. Only rarely does the infection linger in the body and cause cancer. The American Cancer Society estimates there will be about 11,150 cases of cervical cancer in the US in 2007. About 3,670 women will die from the disease.

Widespread vaccination promises to reduce the number of people with diseases caused by HPV, the guidelines say. Over the long term (it can take up to 20 years for an HPV infection to cause cervical cancer) that will mean fewer cases of cervical cancer. In the short term, it will mean fewer cases of genital warts, and less need for procedures (like biopsies) used to treat pre-cancerous changes in the cervix.

Screening Still Needed

But being vaccinated will not eliminate the need for cervical cancer screening, the guidelines stress.

For one thing, the vaccine only protects against 2 types of HPV that cause cervical cancer; there are around a dozen other types that also can cause this disease. The vaccine also doesn't protect women if they are already infected with one of HPV types targeted by the vaccine.

Women who are vaccinated could therefore still develop cervical cancer, and screening is the best way to prevent that from happening. Screening with the Pap test can detect dangerous changes in the cervix before they ever turn into cancer, or at least find cervical cancer at an early stage, when it is easier to treat.

It also isn't known yet how long the vaccine will provide protection, or if booster vaccinations may be needed at some point. Clinical trials have followed women only for about 5 years.

Citation: "American Cancer Society Guideline for Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Vaccine Use to Prevent Cervical Cancer and Its Precursors" Published in the Jan./Feb. 2007 CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians (Vol. 57, No. 1: 7-28). First author: Debbie Saslow, PhD, American Cancer Society.

Pap Test, a Mainstay Against Cervical Cancer, May Be Fading

By Andrew Pollack : NY Times article : January 16, 2007

The big news in the war on cervical cancer is the new vaccine recently approved to prevent the disease. But another major change that will affect millions of women is also under way, though more slowly and quietly.

The Pap smear, an annual ritual for many women and the mainstay of cervical cancer prevention for more than half a century, may start to fade in importance.

It will not disappear for many more years, if ever. But a newer genetic test that detects human papillomavirus, or HPV, which causes cervical cancer, is starting to play a bigger role in screening. And other genetic tests are being developed. At the least, some experts say, women will no longer need Pap smears as often.

“We can potentially change the entire cervical screening paradigm,” said Dr. Thomas C. Wright, a professor of pathology at Columbia University Medical Center who is also a consultant for Roche, which is developing a genetic HPV test.

The new vaccine could also deal a longer-term blow to Pap testing, which works by detecting abnormal cells from the cervix that could be on their way to becoming cancerous. It is not that women would no longer need screening because they had been vaccinated. The vaccine, approved only for girls and women 9 to 26 years old, does not protect against all strains of HPV that cause cancer.

If a precancerous lesion is present, the Pap test will detect it only 50 percent to 80 percent of the time. Pap testing is effective only because it is done often; a lesion can take 10 years to turn into a cancer, so a yearly test will probably find it in time.

As more women get the HPV vaccine, however, the number of lesions will decline, making the Pap test more costly per cancer case detected. And with fewer problems to detect, said Dr. Eduardo L. Franco, a professor of epidemiology and oncology at McGill University, the technicians who read Pap smears may lower their guard — and their accuracy.

Pap testing “is going to break down in a world in which vaccination decreases the prevalence of lesions,” said Dr. Franco, who said he had done some minor consulting for genetic test developers. Referring to the accuracy of Pap testing, he added, “It’s already bad enough, and it’s going to get worse.”

But Pap testing has its strong defenders, who question the value of the genetic test for HPV. Some gynecologists say having women come for annual Pap testing brings them in for other needed examinations. And there is a huge industry built up to provide the screening.

“The perception is that the annual Pap smear drives volume,” said Dr. Walter Kinney, a gynecological oncologist at Kaiser Permanente, the health maintenance organization. “I don’t see anyone raising their hand volunteering to give that up.”

At Kaiser, where doctors’ pay does not depend on customer volume, the genetic HPV test is offered with Pap testing to every woman 30 and older. If both tests are negative, a woman does not come back for further screening for three years. The savings from less frequent screening more than pay for the extra cost of the HPV test, Dr. Kinney said.

Kaiser’s testing laboratory in Berkeley, Calif., processes 300,000 to 500,000 cervical specimens a year. A robotic arm rapidly retrieves particular specimens from cold storage for testing and disposes of others when they are no longer needed.

The most recent guidelines from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, issued in 2003, suggested that some women over 30 do not need annual Pap tests, but many doctors and patients have resisted that idea.

“Sometimes you advocate that strategy, but the woman comes back the next year almost demanding the Pap smear,” said Dr. Juan Felix, a professor of pathology and of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Southern California. “Women have been sort of mentally trained to come to get their annual test.”

Pap testing is named for Dr. George N. Papanicolaou, who developed the test at Cornell Medical School. It started to become widely used in the 1950s.

Cells are scraped from the surface of the cervix, spread on a microscope slide and examined for abnormalities that could indicate a precancerous lesion. If found and confirmed by further examination, the lesions can be removed by any of several techniques.

Pap testing has cut cervical cancer rates by 75 percent or more in nations with thorough screening. In the United States, there are now about 10,000 cases of cervical cancer each year and 4,000 deaths. More than half the cases are in women who do not undergo screening.

“It is one of the greatest public health interventions in terms of sheer success and lives saved,” said Philip E. Castle, an expert on cervical cancer screening at the National Cancer Institute.

But while successful, Dr. Castle said, Pap screening is “not very efficient,” costing billions of dollars a year. And it does miss cancer cases. A study of women with cervical cancer, conducted among members of seven health plans and published in The Journal of the National Cancer Institute in 2005, found that 32 percent had had one or more normal Pap tests in the three years before the diagnosis.

B. K. Cockrell, 57, a homemaker in Troup, Tex., was one woman who got cancer despite a series of normal Pap tests. In 2005, her gynecologist, Dr. A. Jay Staub of Dallas, also began giving the HPV genetic test, which gave a positive reading. Further examination showed that Ms. Cockrell had cancer, which was caught early enough to be removed by a hysterectomy without the need for chemotherapy or radiation.

“I believe I would be extremely ill today” if not for the HPV test, she said.

A newer form of Pap testing called liquid cytology, which spreads the cells more evenly on a slide, is said by some cytologists to be more sensitive, though some published studies contradict that.

But Pap testing has other problems as well. Of the 50 million to 60 million tests done in the United States each year, as many as two million are classified as ambiguous, possibly a lesion and possibly not. Such results require further testing, like colposcopy, an uncomfortable procedure in which the cervix is examined with a magnifying device, and biopsy, which can be painful.

The HPV genetic test looks for the DNA of 13 of the cancer-causing strains of the virus. Experts say this test can detect more than 90 percent of precancerous lesions. It is also easier to automate and far less likely to produce ambiguous results.

The samples are taken the same way as for a Pap test, meaning women still need to get into stirrups. But since the genetic test is less prone to error, experts say it is possible that in the future women will be able to take their own samples.

The test was first approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 1999, and its use has grown steadily, partly spurred by advertising by the test’s manufacturer, Digene. The company, based in Gaithersburg, Md., says about seven million Americans are getting the test each year, which is one-fifth of those it believes would be eligible. With Merck now calling attention to the role of HPV in its advertisements for its new vaccine, Digene executives expect interest in their test to grow.

Some experts say that since the HPV test catches more lesions than Pap, it would be cost-effective to make it the primary test, with Pap testing used only on the women who test positive for the virus.

“HPV testing as the stand-alone primary screening technology represents the scientifically obvious next step,” F. Xavier Bosch of the Catalán Institute of Oncology in Barcelona, Spain, wrote last August in a supplement of the journal Vaccine on the future of cervical cancer prevention.

But some experts say the HPV test is not ready for that.

One problem is that HPV testing costs $50 to more than $100, compared with as little as $20 for a Pap test. More significant, many, if not most, sexually active women will be infected with HPV at some point. But in most cases, particularly for younger women, the immune system dispenses with the virus.

That is why even those who advocate using HPV testing as the primary screen, or using it alongside Pap testing, do so only for women over 30 or 35, when the viral infection is less likely to be transient. (The HPV test is approved for two uses: to help resolve an ambiguous Pap test or to use in conjunction with Pap screening for women 30 and over.)

Dr. George Sawaya, an associate professor of obstetrics, gynecology and reproductive sciences at the University of California, San Francisco, says about 2,500 to 3,000 cervical cancer cases in the United States each year are in women with normal Pap tests. While use of the HPV test instead of the Pap as the primary screen may further reduce that number, “we have to make sure we are not dragging along tens of thousands of women who will have positive tests but no disease,” he said.

Some of those women would be subject to unnecessary biopsies and even to removal of lesions that would never turn cancerous, he said. The removal operations have risks of their own, he added, potentially raising the chances a woman will have premature deliveries in the future.

Wider use of HPV testing would also mean telling millions of women that they have a sexuallt transmitted disease, causing unnecessary stress. “Everybody presumes they are dirty when they are told they have something like this,” said Dr. Abbie Roth, an obstetrician and gynecologist at Northwestern Memorial Hospital in Chicago. “Everybody universally cries when they get that information.”

Digene says it hopes that European countries, which place more limits on medical spending than the United States, will make HPV testing the standard in place of the Pap. European experts disagree on whether that will happen.

But Pap testing is likely to be displaced in developing countries, which account for more than 80 percent of the roughly 500,000 new cases of cervical cancer and 275,000 deaths each year. Those countries cannot do efficient Pap screening for lack of laboratories and technicians and difficulty in getting women, who might have to walk miles to a clinic, to come for testing every year.

In the developing world, Pap testing has had “basically no impact on cervical cancer rates in any country, ever,” said Jacqueline Sherris, a strategic program leader for reproductive health at PATH, a nonprofit organization in Seattle.

PATH is working with Digene to develop a simpler and cheaper version of the HPV test for developing countries. Women might be tested only once or twice during their 30s but would get fairly good protection, Ms. Sherris said.

Still other tests are in development. One would determine the specific strain of HPV infecting a woman. Types 16 and 18 account for most cancers (and are the cancer-causing types targeted by the new vaccine). So having one of them would be considered more worrisome.

Yet another test would look for the activation of two genes, called E6 and E7. Such activation is believed to be required for a precancerous lesion to turn into cancer.

“Looking forward,” said Dr. Wright of Columbia, “the molecular tests are becoming so good that we can see a time when cytology is no longer used as the primary screening test.”

Pap testing and HPV screening

The Food and Drug Administration has approved a new screening test for cervical cancer that could help distinguish women at increased risk from those at very low risk of developing the disease. Women over age 30 can now receive a test for human papilloma virus or HPV, at the same time they receive a Pap test.

The HPV test, manufactured by Digene Corp. of Gaithersburg, Maryland, is already approved to detect HPV in women with abnormal Pap smears, but until now, it was not approved for screening purposes, before results of the Pap test were known.

Since March, 2000, the test has been used for women whose Pap tests show mild abnormalities that can't be readily explained, a condition referred to as Atypical Squamous Cells of Unknown Origin, or ASC-US. Until then, such women had to undergo repeated Pap smears every few months in hopes of determining the nature of the abnormal cells? Whether they might develop into precancerous lesions or clear up on their own. In some cases, a colposcopy ? An examination of the cervix with magnifying binoculars - was used to select areas of the cervix to biopsy, to determine whether the cells were dangerous. Women with ASC-US Pap results who have negative HPV test results could be reassured that their short term risk of developing cervical cancer was very low, and that they could safely return to the usual screening schedule.

HPV is a family of more than 100 extremely common viruses, of which about 30 are sexually transmitted. Of these, about a dozen "high-risk" varieties are linked to nearly all cervical cancers, and to some cases of vaginal, vulvar, anal, and penile cancers. Other, "low-risk" varieties cause genital warts. In most cases, however, HPV infection causes no symptoms at all, so a person who has HPV might not even know it. In other cases, symptoms of HPV do not appear until years after infection.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 50%-75% of sexually active adults will harbor the virus at some point in their life. In most cases, the immune system defeats the virus with no permanent effects. Sometimes, though, HPV that lingers in the body causes changes in the cervix that are detected with a Pap smear. In rare cases, these changes lead to cancer.

The risk of HPV progressing causing changes that could lead to cancer is greater for women over age 30 than for younger women, said Debbie Saslow, PhD, director of breast and gynecologic cancer programs for ACS, which is why the new screening test isn't recommended for younger women. HPV infections in younger women tend to go away by themselves.

"In a woman over 30," Saslow said, "if [an HPV infection] hasn't cleared in a year, you want to do additional testing. It doesn't mean she's going to get cancer, but you want to follow her and watch her more carefully" to see if any treatment is needed.

The FDA said women who have an abnormal Pap test and an HPV infection have a 6% to 7% greater risk of developing cervical cancer if they aren't treated.

Still, cervical cancer is rare even among women who do have an HPV infection. The American Cancer Society estimates about 12,200 new cases of cervical cancer will be diagnosed this year. Screening can help prevent the disease by catching abnormalities in the cervix before they become cancerous. The Society recommends Pap tests beginning either at age 21 or three years after a woman first has sexual intercourse. Until age 30, screening should be done every year with the regular Pap test or every two years using the newer liquid-based Pap test. After age 30, women who have had three normal Pap tests in a row can wait two or three years for their next Pap.

"It's important to get screened," Saslow said, and even HPV-negative women should follow the recommended schedule. The FDA said the new use of the HPV test is in addition to Pap tests. The HPV test is not a substitute for regular Pap tests.

Cervical Cancer Vaccine Remains Underused

By Carol Weeg : NY Times Article : July 25, 2008

In Brief:

By getting vaccinated for human papillomavirus, or HPV, before she becomes sexually active, a girl reduces her lifetime risk of developing cervical cancer by 70 percent, studies suggest.

Fewer than one in four eligible girls and women, ages 9 to 26, has been vaccinated against HPV.

The HPV vaccine remains controversial, despite some studies showing its safety and effectiveness.

One in four American girls and women ages 14 to 19 has a sexually transmitted disease, and one in four ages 14 to 59 is infected with HPV.

Preventing cervical cancer may be the last thing on the mind of the average 11-year-old girl. But by getting vaccinated for human papillomavirus, or HPV, the virus that causes nearly all cases of cervical cancer, a girl reduces her lifetime risk of developing the disease by 70 percent, studies suggest.

The vaccine, called Gardasil and made by Merck, protects against the two types of HPV — 16 and 18 — responsible for most cervical cancers, the second leading cancer killer among women worldwide. It also immunizes against HPV 6 and 11, the types of the virus that cause 90 percent of genital warts, which are not life-threatening but can be distressing and difficult to treat.

The federal Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommends vaccinating girls between the ages of 11 and 12, and as young as 9 at the discretion of doctors. It also advises that girls and women ages 13 to 26 receive the vaccine if they have not yet been immunized. But the vaccine is controversial, and only 24 percent of eligible girls and women have gotten at least one of the three recommended doses.

One reason for the controversy is that the vaccine is relatively new. The Food and Drug Administration approved it in 2006, and this leaves some parents, and doctors, questioning its long-term safety and efficacy.

“Studies have been done on fewer than 2,000 girls ages 10 to 15, and to know if a vaccine is safe, millions of people have to get it and have a chance to report any adverse events,” said Dr. Diane Harper, director of the Gynecologic Cancer Prevention Research Group at Dartmouth Medical School. “It’s a public health experiment, but that’s the nature of vaccines.”

Proponents counter by pointing to Gardasil’s track record. An estimated eight million girls and women in the United States have received one or more doses of the vaccine, with fewer than 7 percent reporting serious side effects — about half the rate for vaccines over all.

“There’s six years of safety data that shows no long-term risks, and that’s the same timeframe for other recently recommended vaccines,” said Dr. Mark H. Einstein, director of clinical research in the gynecologic oncology division of Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York.

Safety issues aside, some people oppose the vaccine because they fear that its use will encourage promiscuity. Or they have religious objections to vaccines, or argue that the government has no right to mandate its use, as some states have tried to do.

With or without the vaccine, many teenagers are already sexually active. A recent government study found that one in four girls ages 14 to 19 has a sexually transmitted disease. And one in four American girls and women ages 14 to 59 is infected with HPV, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “This vaccine is a preventive health measure, not a sex education measure,” Dr. Einstein said. “From a science standpoint, it completely makes sense to vaccinate girls against HPV.”

The vaccine is being studied for use in boys and men, too.

“We don’t have widespread vaccination of women, so immunizing men may help protect those women who aren’t vaccinated,” said Dr. Kevin Ault, associate professor of gynecology and obstetrics at Emory University Medical School in Atlanta. It would also protect men against genital warts, which they get at a higher rate than women, and may immunize against relatively rare HPV-related cancers of the penis, anus, neck and head.

Most HPV infections clear up on their own, but those that persist, usually for five years or longer, increase a woman’s risk for developing precancerous cervical lesions. Pap tests, a routine part of a gynecological exam, usually detect these precancers, which can be treated so they do not develop into cancer. Still, 11,000 new cases of cervical cancer are diagnosed in the United States every year, most in women who haven’t gotten regular Pap tests, but some in women whose Pap tests didn’t detect precancerous cells.

Fortunately, cervical cancer is slow-growing.

“Usually the time to progression from a premalignant lesion to an invasive cancer is about 10 years,” said Dr. Teresa Diaz-Montes, gynecologic oncologist at Johns Hopkins Medical Center. When caught early, which is usually the case in the United States, cervical cancer can often be treated and cured by a simple or radical hysterectomy. Survival rates are high. “If the tumor is confined to the cervix, the five-year survival rate will be 80 to over 95 percent,” Dr. Diaz-Montes said.

And women can improve their chance of survival by getting treated by gynecologic oncologists rather than general gynecologists, studies show.

“Cervical cancer is not as common now as it was in the past because of Pap tests, so it’s important to be seen by a gynecologic oncologist because these are the specialists trained to treat this disease,” Dr. Diaz-Montes said. She advises women to look for a physician who sees a high volume of patients that need the same type of treatment they require.

Still, 3,700 women die from cervical cancer in the United States every year. Experts say that doesn’t need to happen.

“By getting vaccinated early and having regular Pap tests, and HPV tests when her health care provider recommends them,” Dr. Einstein said, “a woman has the best chance of preventing what is by far one of the most preventable cancers we have.”

American Cancer Society Guidelines

HPV Vaccine

Girls should get the new vaccine for human papilloma virus (HPV) at age 11-12, the American Cancer Society says in new guidelines issued Friday.

HPV is a very common virus. Some types of HPV are sexually transmitted, and these can cause cervical cancer and other types of cancer, as well as genital warts.

The vaccine currently available, called Gardasil, protects against 2 types of HPV that cause about 70% of cervical cancers, and 2 other types that cause 90% of genital warts. It is given as a series of 3 shots over the course of 6 months. Other HPV vaccines are also being tested.

But screening will still be an important part of cervical cancer prevention, even in people who have been vaccinated, the guidelines say. They are published in the latest issue of the ACS journal CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians.

The complete ACS recommendations address several different groups:

- Routine HPV vaccination is recommended for girls aged 11-12 years.

- Girls as young as 9 years old may be vaccinated.

- The vaccine is also recommended for girls 13-18 years old to catch up on missed shots or to complete the series of shots.

- There is not yet enough information to recommend for or against vaccinating women 19-26 years old, so these women should discuss vaccination with their doctor.

- The HPV vaccine is not recommended at this time for women over age 26.

- The HPV vaccine is not recommended at this time for boys or men.

- Women should continue to be screened for cervical cancer according to ACS guidelines, regardless of whether they have gotten the HPV vaccine.

Potential for Preventing Many Cervical Cancers

Cervical cancer screening with the Pap test has greatly reduced the incidence of this cancer in the United States. The greatest impact of the vaccine is likely to be in groups where screening levels are low, such as in medically underserved populations. The vaccine may prove especially helpful in other countries where cervical cancer screening is not routinely done.

Giving the vaccine to young girls is important, the new guidelines say, because it works best when given to people before they ever become infected with HPV. Because the types of HPV that cause cervical cancer are sexually transmitted, girls should get vaccinated well before they become sexually active.

Surveys of US teens show that nearly a quarter of them have had sex by age 15, and 70% have had sex by age 18.

Most people become infected with HPV at some point in their lives, but the infection usually clears up on its own without ever causing any symptoms. Only rarely does the infection linger in the body and cause cancer. The American Cancer Society estimates there will be about 11,150 cases of cervical cancer in the US in 2007. About 3,670 women will die from the disease.

Widespread vaccination promises to reduce the number of people with diseases caused by HPV, the guidelines say. Over the long term (it can take up to 20 years for an HPV infection to cause cervical cancer) that will mean fewer cases of cervical cancer. In the short term, it will mean fewer cases of genital warts, and less need for procedures (like biopsies) used to treat pre-cancerous changes in the cervix.

Screening Still Needed

But being vaccinated will not eliminate the need for cervical cancer screening, the guidelines stress.

For one thing, the vaccine only protects against 2 types of HPV that cause cervical cancer; there are around a dozen other types that also can cause this disease. The vaccine also doesn't protect women if they are already infected with one of HPV types targeted by the vaccine.

Women who are vaccinated could therefore still develop cervical cancer, and screening is the best way to prevent that from happening. Screening with the Pap test can detect dangerous changes in the cervix before they ever turn into cancer, or at least find cervical cancer at an early stage, when it is easier to treat.

It also isn't known yet how long the vaccine will provide protection, or if booster vaccinations may be needed at some point. Clinical trials have followed women only for about 5 years.

Citation: "American Cancer Society Guideline for Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Vaccine Use to Prevent Cervical Cancer and Its Precursors" Published in the Jan./Feb. 2007 CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians (Vol. 57, No. 1: 7-28). First author: Debbie Saslow, PhD, American Cancer Society.

Pap Test, a Mainstay Against Cervical Cancer, May Be Fading

By Andrew Pollack : NY Times article : January 16, 2007

The big news in the war on cervical cancer is the new vaccine recently approved to prevent the disease. But another major change that will affect millions of women is also under way, though more slowly and quietly.

The Pap smear, an annual ritual for many women and the mainstay of cervical cancer prevention for more than half a century, may start to fade in importance.

It will not disappear for many more years, if ever. But a newer genetic test that detects human papillomavirus, or HPV, which causes cervical cancer, is starting to play a bigger role in screening. And other genetic tests are being developed. At the least, some experts say, women will no longer need Pap smears as often.

“We can potentially change the entire cervical screening paradigm,” said Dr. Thomas C. Wright, a professor of pathology at Columbia University Medical Center who is also a consultant for Roche, which is developing a genetic HPV test.

The new vaccine could also deal a longer-term blow to Pap testing, which works by detecting abnormal cells from the cervix that could be on their way to becoming cancerous. It is not that women would no longer need screening because they had been vaccinated. The vaccine, approved only for girls and women 9 to 26 years old, does not protect against all strains of HPV that cause cancer.

If a precancerous lesion is present, the Pap test will detect it only 50 percent to 80 percent of the time. Pap testing is effective only because it is done often; a lesion can take 10 years to turn into a cancer, so a yearly test will probably find it in time.

As more women get the HPV vaccine, however, the number of lesions will decline, making the Pap test more costly per cancer case detected. And with fewer problems to detect, said Dr. Eduardo L. Franco, a professor of epidemiology and oncology at McGill University, the technicians who read Pap smears may lower their guard — and their accuracy.

Pap testing “is going to break down in a world in which vaccination decreases the prevalence of lesions,” said Dr. Franco, who said he had done some minor consulting for genetic test developers. Referring to the accuracy of Pap testing, he added, “It’s already bad enough, and it’s going to get worse.”

But Pap testing has its strong defenders, who question the value of the genetic test for HPV. Some gynecologists say having women come for annual Pap testing brings them in for other needed examinations. And there is a huge industry built up to provide the screening.

“The perception is that the annual Pap smear drives volume,” said Dr. Walter Kinney, a gynecological oncologist at Kaiser Permanente, the health maintenance organization. “I don’t see anyone raising their hand volunteering to give that up.”

At Kaiser, where doctors’ pay does not depend on customer volume, the genetic HPV test is offered with Pap testing to every woman 30 and older. If both tests are negative, a woman does not come back for further screening for three years. The savings from less frequent screening more than pay for the extra cost of the HPV test, Dr. Kinney said.

Kaiser’s testing laboratory in Berkeley, Calif., processes 300,000 to 500,000 cervical specimens a year. A robotic arm rapidly retrieves particular specimens from cold storage for testing and disposes of others when they are no longer needed.

The most recent guidelines from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, issued in 2003, suggested that some women over 30 do not need annual Pap tests, but many doctors and patients have resisted that idea.

“Sometimes you advocate that strategy, but the woman comes back the next year almost demanding the Pap smear,” said Dr. Juan Felix, a professor of pathology and of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Southern California. “Women have been sort of mentally trained to come to get their annual test.”

Pap testing is named for Dr. George N. Papanicolaou, who developed the test at Cornell Medical School. It started to become widely used in the 1950s.

Cells are scraped from the surface of the cervix, spread on a microscope slide and examined for abnormalities that could indicate a precancerous lesion. If found and confirmed by further examination, the lesions can be removed by any of several techniques.

Pap testing has cut cervical cancer rates by 75 percent or more in nations with thorough screening. In the United States, there are now about 10,000 cases of cervical cancer each year and 4,000 deaths. More than half the cases are in women who do not undergo screening.

“It is one of the greatest public health interventions in terms of sheer success and lives saved,” said Philip E. Castle, an expert on cervical cancer screening at the National Cancer Institute.

But while successful, Dr. Castle said, Pap screening is “not very efficient,” costing billions of dollars a year. And it does miss cancer cases. A study of women with cervical cancer, conducted among members of seven health plans and published in The Journal of the National Cancer Institute in 2005, found that 32 percent had had one or more normal Pap tests in the three years before the diagnosis.

B. K. Cockrell, 57, a homemaker in Troup, Tex., was one woman who got cancer despite a series of normal Pap tests. In 2005, her gynecologist, Dr. A. Jay Staub of Dallas, also began giving the HPV genetic test, which gave a positive reading. Further examination showed that Ms. Cockrell had cancer, which was caught early enough to be removed by a hysterectomy without the need for chemotherapy or radiation.

“I believe I would be extremely ill today” if not for the HPV test, she said.

A newer form of Pap testing called liquid cytology, which spreads the cells more evenly on a slide, is said by some cytologists to be more sensitive, though some published studies contradict that.

But Pap testing has other problems as well. Of the 50 million to 60 million tests done in the United States each year, as many as two million are classified as ambiguous, possibly a lesion and possibly not. Such results require further testing, like colposcopy, an uncomfortable procedure in which the cervix is examined with a magnifying device, and biopsy, which can be painful.

The HPV genetic test looks for the DNA of 13 of the cancer-causing strains of the virus. Experts say this test can detect more than 90 percent of precancerous lesions. It is also easier to automate and far less likely to produce ambiguous results.

The samples are taken the same way as for a Pap test, meaning women still need to get into stirrups. But since the genetic test is less prone to error, experts say it is possible that in the future women will be able to take their own samples.

The test was first approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 1999, and its use has grown steadily, partly spurred by advertising by the test’s manufacturer, Digene. The company, based in Gaithersburg, Md., says about seven million Americans are getting the test each year, which is one-fifth of those it believes would be eligible. With Merck now calling attention to the role of HPV in its advertisements for its new vaccine, Digene executives expect interest in their test to grow.

Some experts say that since the HPV test catches more lesions than Pap, it would be cost-effective to make it the primary test, with Pap testing used only on the women who test positive for the virus.

“HPV testing as the stand-alone primary screening technology represents the scientifically obvious next step,” F. Xavier Bosch of the Catalán Institute of Oncology in Barcelona, Spain, wrote last August in a supplement of the journal Vaccine on the future of cervical cancer prevention.

But some experts say the HPV test is not ready for that.

One problem is that HPV testing costs $50 to more than $100, compared with as little as $20 for a Pap test. More significant, many, if not most, sexually active women will be infected with HPV at some point. But in most cases, particularly for younger women, the immune system dispenses with the virus.

That is why even those who advocate using HPV testing as the primary screen, or using it alongside Pap testing, do so only for women over 30 or 35, when the viral infection is less likely to be transient. (The HPV test is approved for two uses: to help resolve an ambiguous Pap test or to use in conjunction with Pap screening for women 30 and over.)

Dr. George Sawaya, an associate professor of obstetrics, gynecology and reproductive sciences at the University of California, San Francisco, says about 2,500 to 3,000 cervical cancer cases in the United States each year are in women with normal Pap tests. While use of the HPV test instead of the Pap as the primary screen may further reduce that number, “we have to make sure we are not dragging along tens of thousands of women who will have positive tests but no disease,” he said.

Some of those women would be subject to unnecessary biopsies and even to removal of lesions that would never turn cancerous, he said. The removal operations have risks of their own, he added, potentially raising the chances a woman will have premature deliveries in the future.

Wider use of HPV testing would also mean telling millions of women that they have a sexuallt transmitted disease, causing unnecessary stress. “Everybody presumes they are dirty when they are told they have something like this,” said Dr. Abbie Roth, an obstetrician and gynecologist at Northwestern Memorial Hospital in Chicago. “Everybody universally cries when they get that information.”

Digene says it hopes that European countries, which place more limits on medical spending than the United States, will make HPV testing the standard in place of the Pap. European experts disagree on whether that will happen.

But Pap testing is likely to be displaced in developing countries, which account for more than 80 percent of the roughly 500,000 new cases of cervical cancer and 275,000 deaths each year. Those countries cannot do efficient Pap screening for lack of laboratories and technicians and difficulty in getting women, who might have to walk miles to a clinic, to come for testing every year.

In the developing world, Pap testing has had “basically no impact on cervical cancer rates in any country, ever,” said Jacqueline Sherris, a strategic program leader for reproductive health at PATH, a nonprofit organization in Seattle.

PATH is working with Digene to develop a simpler and cheaper version of the HPV test for developing countries. Women might be tested only once or twice during their 30s but would get fairly good protection, Ms. Sherris said.

Still other tests are in development. One would determine the specific strain of HPV infecting a woman. Types 16 and 18 account for most cancers (and are the cancer-causing types targeted by the new vaccine). So having one of them would be considered more worrisome.

Yet another test would look for the activation of two genes, called E6 and E7. Such activation is believed to be required for a precancerous lesion to turn into cancer.

“Looking forward,” said Dr. Wright of Columbia, “the molecular tests are becoming so good that we can see a time when cytology is no longer used as the primary screening test.”

- Ask about the vaccine Gardasil which is now available for girls and women ages 9-26 for protection against certain strains of HPV.

- Cervical cancer screening should begin about 3 years after a woman begins having sexual intercourse, but no later than 21 years of age.

- Screening should be done annually with regular Pap tests or every two years with the liquid-based thin smear Pap tests.