- RETIREMENT ANNOUNCEMENT

- HOME PAGE

- "MYCHART" the new patient portal

- BELMONT MEDICAL ASSOCIATES

- MOUNT AUBURN HOSPITAL

- EMERGENCIES

- PRACTICE PHILOSOPHY

- MY RESUME

- TELEMEDICINE CONSULTATION

- CONTACT ME

- LAB RESULTS

- ePRESCRIPTIONS

- eREFERRALS

- RECORD RELEASE

- MEDICAL SCRIBE

- PHYSICIAN ASSISTANT (PA)

- Medicare Annual Wellness Visit

- Case management/Social work

- Quality Care Measures

- Emergency closing notice

- FEEDBACK

- Talking to your doctor

- Choosing..... and losing a doctor

- INDEX A - Z

- ALLERGIC REACTIONS

- Alternative Medicine

- Alzheimer's Disease

- Bladder Problems

- Blood disorders

- Cancer Concerns

- GENETIC TESTING FOR HEREDITARY CANCER

- Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

- Controversial Concerns

- CPR : Learn and save a life

- CRP : Inflammatory marker

- Diabetes Management

- Dizziness, Vertigo,Tinnitus and Hearing Loss

- EXERCISE

- FEMALE HEALTH

-

GASTROINTESTINAL topics

- Appendicitis

- BRAT diet

- Celiac Disease or Sprue

- Crohn's Disease

- Gastroenterologists for Colon Cancer Screening

- Colonoscopy PREP

- Constipation

- Gluten sensitivity, but not celiac disease

- Heartburn and GERD

- Hemorrhoids and Anal fissure

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- NASH : Non Alcoholic Steato Hepatitis

- FEET PROBLEMS

- HEART RELATED topics

-

INFECTIOUS DISEASES

- Antibiotic Resistance

- Cat bites >

- Clostridia difficile infection - the "antibiotic associated germ"

- CORONA VIRUS

- Dengue Fever and Chikungunya Fever

- Food borne illnesses

- Shingles Vaccine

- Hepatitis B

- Hepatitis C

- Herpes

- Influenza

- Helicobacter pylori - the "ulcer germ"

- HIV Screening

- Lyme and other tick borne diseases

- Measles

- Meningitis

- MRSA (Staph infection)

- Norovirus

- Sexually Transmitted Diseases

- Shingles (Herpes Zoster)

- Sinusitis

- West Nile Virus

- Whooping Cough (Pertussis)

- Zika virus and pregnancy

- INSURANCE related topics

- KIDNEY STONES

- LEG CRAMPS

- LIBRARY for patients

- LIFE DECISIONS

- MALE HEALTH

- Medication/Drug side effects

- MEDICAL MARIJUANA

- MENTAL HEALTH

- Miscellaneous Articles

-

NUTRITION - EXERCISE - WEIGHT

- Cholesterol : New guidelines for treatment

- Advice to lower your cholesterol

- Cholesterol : Control

- Cholesterol : Raising your HDL Level

- Exercise

- Food : Making Smart Choices

- Food : Making Poor Choices

- Food : Grape Fruit and Drug Interaction

- Food : Vitamins, Minerals and Supplements

- Omega 3 fatty acids

- Vitamin B12 deficiency

- Vitamin D

- Weight Loss

- ORTHOPEDICS

- PAIN

- PATIENTS' RIGHTS

- SKIN

- SLEEP

- SMOKING

- STROKE

- THYROID

- SUBSTANCE ABUSE

- Travel and Vaccination

- TREMOR

- Warfarin Anticoagulation

- OTHER STUFF FOLLOWS

- Fact or Opinion?

- Hippocratic Oath

- FREE ADVICE.......for what its worth!

- LAUGHTER.....is the best medicine

- Physicians Pet Peeves

- PHOTO ALBUM - its not all work!

- Cape Town, South Africa

- Tribute page

- The 100 Club

- Free Wi-Fi

Blood Clots

- Pulmonary Emboli

- Factor V Leiden

Recovering from surgery on his bladder and prostate in a South Florida hospital, 65-year-old Jorge Blau was stable the day after the procedure as he sat in a chair chatting with family members. Suddenly he asked to get back in bed. There, he became short of breath, and he died moments later.

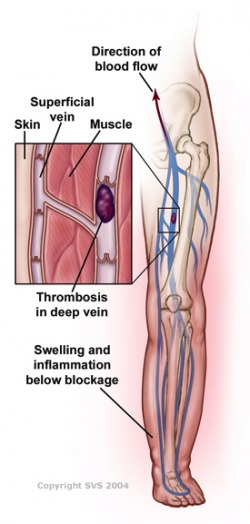

Mr. Blau was the victim of a pulmonary embolism, the leading cause of preventable hospital deaths in the U.S. The disorder occurs when a blood clot forms in the deep veins of the legs or pelvis, known as deep-vein thrombosis, and then breaks free and travels to the lungs, where it blocks a pulmonary artery or one of its branches.

Heading Off Death Life-threatening blood clots are a growing problem in hospitals.

- Clots kill some 200,000 hospital patients in the U.S. each year.

- Institutions are increasingly screening patients for risk and taking measures to prevent clots.

- Patients are being urged to get up and start moving soon after procedures.

But the biggest danger is to hospitalized patients, where DVT followed by pulmonary embolism -- a sequence of occurrences known as a venous thromboembolism event, or VTE -- kills nearly 200,000 U.S. patients a year. Though VTE most often happens to adults over 40, any patient on bed rest after illness or surgery is vulnerable, even after being discharged from hospital. It is the leading cause of maternal death associated with childbirth, which puts pressure on deep veins.

Now, a growing number of hospitals are moving to do a better job of averting life-threatening clots. They are more carefully screening for potential risk factors including obesity, smoking and a family history of clotting problems. They also are more closely following established guidelines for prevention, such as putting certain patients on blood-thinning medications -- including anticlotting drugs heparin or warfarin -- and using special compression socks after surgery that improve circulation in the legs.

For the most part, however, hospitals and surgery centers often fail to screen patients for risks of DVT, and only about a third of patients receive the recommended prevention therapies, studies show.

Helping to pressure hospitals to do a better job to prevent blood clots is a threat of reduced payments from Medicare, which last year began withholding payments for certain preventable occurrences. Recently added to Medicare's list of "never events" that aren't reimbursed are DVT and pulmonary embolisms following knee or hip surgery. Hospital purchasing alliance Premier Inc. is working with about 250 hospitals on better compliance with DVT-prevention measures in a project co-sponsored by Medicare.

Last year, the Surgeon General's office identified DVT prevention as a national priority. The Joint Commission, a nonprofit group that accredits hospitals, later this year will start asking hospitals to collect and report data on DVT, including what they are doing to prevent and treat the condition and how many cases of preventable DVT occur.

Weight as a Risk Factor "People need to know that this is a risk, and there should be protocols in place to prevent it," says Mr. Blau's wife, Ana Blau, of Palm Beach, Fla. She says her husband was overweight, a risk factor for DVT, and compression stockings were used after his surgery.

But hospital records provided by the family show Mr. Blau wasn't given medications used to prevent clots from forming, despite indications he might have been a candidate for these; Mr. Blau had a history of developing clots after past surgery, the records show. But he also had had spinal anesthesia, which increases the risk of bleeding, and may have been a factor in not providing a blood thinner.

Medical guidelines for preventing clots vary by the type of procedure being performed. Physicians also say the guidelines often have to be adjusted to fit the needs of individual patients. Brian Burnikel, medical director of the Total Joint Center at Greenville Hospital System in Greenville, S.C., says that in joint-replacement surgery, for instance, surgeons must balance the need to thin the blood to prevent a clot with the need to make sure patients don't develop a hematoma -- a collection of blood that can increase the risk of infection.

Risk of Bleeding Patients who have had a spinal anesthetic are at increased risk of bleeding around the spine and paralysis from hematoma, so instead of using an aggressive anticlotting drug, patients may just get a milder thinner such as aspirin, Dr. Burnikel says. Surgeons operating on a leg might also reduce the risk of clots by avoiding putting the patient's limb in an extreme position, he says. "You have to tailor what you are doing for each specific patient," Dr. Burnikel says.

Medical experts say the incidence of DVT followed by pulmonary embolism, which is fatal about 30% of the time, is increasing in the hospital. That's because many patients are older, more obese, and are undergoing more complicated and invasive surgeries. As many as two million Americans are estimated to suffer from DVT annually. Some have an inherited blood-clotting disorder that predisposes them to DVT. Medical conditions such as cancer, congestive heart failure, chronic respiratory failure, varicose veins, and estrogen treatment also are linked to increased risk.

The Coalition to Prevent Deep-Vein Thrombosis, funded by a maker of anticlotting drugs, Sanofi-Aventis, offers risk-assessment tools for consumers at PreventDVT.org. Nonprofit group ClotCare.com, which also receives some funding from pharmaceutical companies, offers information on DVT prevention, as well as research and therapies used to prevent blood clots.

After Going Home Patient-advocacy groups say patients and families often aren't advised of the risk of DVT while in the hospital. Patients also need to know about the risks of developing blood clots that could lead to pulmonary embolisms after they leave the hospital, and to be vigilant about reporting any symptoms to their doctors or seeking care in an emergency room. Among common symptoms are a sudden pain in the leg or shortness of breath.

After a minor outpatient procedure to scrape cartilage from her knee, 68-year-old Carol Barrett of Canada had complained to her family of pain in her legs and shortness of breath. But no one thought it was a sign of anything serious. Two days later, Ms. Barrett collapsed at her home in Newmarket, Ontario, and died. A blood clot that had apparently formed during the 10-minute surgery traveled from the deep veins in her leg to her lungs.

"We didn't know about the possibility of blood clots after minor surgery," says her daughter, Cathy Kincaide. "We now know there were some red flags, and had we been more informed, we might have acted on them and sought medical attention before the clot went to her lungs." Adds Ms. Kincaide: "We need to educate patients that no surgery is minor, and you have to be aware of the risks pre- and post-surgery."

Alpesh Amin, a specialist in hospital medicine at the University of California at Irvine, says that more than 60% of patients who enter the hospital have at least three risk factors for DVT, and the sedentary nature of most hospital stays just worsens the likelihood of a blood clot. Dr. Amin analyzed 72,337 cancer patients from a large hospital discharge database maintained by Premier, the hospital alliance. He found that only 27% of patients who were at risk for DVT between 2003 and 2005 were given appropriate prevention treatments recommended by the American College of Chest Physicians, whose DVT guidelines are the most widely used.

Dr. Amin says his hospital has adopted a computerized order system that prompts doctors to assess patients for DVT risk. Over the past few years, this has resulted in appropriate prevention measures being used 90% of the time, up from 30% prior to the program's being adopted. "Every time you get on an airplane, the flight attendants go through a safety check, and that's the kind of consistency we should have in trying to meet prevention guidelines," Dr. Amin says.

Peering Into Veins After completing a risk-assessment questionnaire when patients are admitted, doctors at some hospitals may order tests such as an ultrasound to take a closer look at a patient's veins. But Richard Karulf, chief of surgery at Fairview Southdale Hospital in Edina, Minn., says screening may not always predict who will develop problems. "Some may have inherited problems we don't know about," Dr. Karulf says. Still, Fairview has reduced the incidence of pulmonary embolism following DVT since it began requiring doctors to evaluate patients for risk.

In 2004, North Mississippi Medical Center in Tupelo, Miss., had about 7.6 cases of DVT per 1,000 patients. It began using a protocol, or list of risk factors, that prompts each physician to assess incoming patients for risk. When appropriate, doctors then are prompted to order anticoagulant therapy and other preventive measures.

A year later, the hospital had one case of DVT per 1,000 patients, and in the past year, there hasn't been a single case of pulmonary embolism in a surgical patient, says Michael O'Dell, the hospital's chief quality officer.

Factor V Leiden Disorder Magnifies Blood Clot Risk

Jane E. Brody : NY Times Article : June 10, 2008

When David Bloom, 39, went to Iraq in 2003 to cover the war for NBC News, his wife, Melanie, naturally feared for his safety. Would a bullet or a bomb claim him? A land mine? An ambush?

Instead it was a blood clot lodged in his lungs that ended his life. Ms. Bloom subsequently learned that her husband carried a genetic abnormality, factor V Leiden, that greatly increased his risk for developing blood clots.

Mr. Bloom had three other risk factors for clots: a long plane ride to Iraq, erratic eating habits that could have caused dehydration, and cramped sleeping space in Army vehicles. But had he not had this genetic quirk — or had he known about it and the higher risks it carried — he might have escaped his fate.

A Hidden Problem Factor V Leiden (pronounced factor five) is the most common hereditary clotting disorder in the United States, present in 2 percent to 7 percent of Caucasians, less often in Hispanics and rarely in Asians and African-Americans.

The disorder accounts for 20 percent and to 40 percent of cases of deep vein thrombosis, or D.V.T., the clot that Mr. Bloom developed in his leg before it broke loose and traveled to his lungs, resulting in a pulmonary embolism that caused his death.

Factor V Leiden is more often than not a hidden disorder, until someone in a family — often someone like Mr. Bloom, who was athletic and healthy — develops a deep vein thrombosis or another unexpected clot. Because screening for this problem is not routine, factor V Leiden is usually not detected until several members of a family develop clots or one person develops a succession of clots.

Even then, a possible carrier of the gene defect may not be tested.

Dr. Rinah Shopnick, medical director of the Hemophilia and Thrombosis Center of Nevada, described the case of Ann, 20, who reported to the center about her doctors’ reactions to her family history. Ann told doctors that her otherwise healthy cousin had suffered a major heart attack in his 40s and was found to have factor V Leiden. Her grandmother died while pregnant, and her aunt, uncle and grandfather died of heart problems.

Ann reported that she had had blood pressure problems since age 8, and developed a serious blood pressure disorder during pregnancy and that her brother had just tested positive for the defect.

Yet she was advised by two doctors not to be tested, she said. The reasoning was that the disorder was rare, that she would have to pay for the test (it is not expensive) and that if she was found to carry the gene it could affect her ability to buy affordable life and health insurance. (Federal legislation has just been passed to protect against such discrimination.)

Inherited Risk In someone with factor V Leiden, clots can arise in veins anywhere. The abnormality can increase the risk of heart attack, stroke, miscarriage, gallbladder dysfunction and toxemia of pregnancy. Clots are also more likely to develop after surgery and childbirth and in women taking oral contraceptives or estrogen therapy.

The disorder results from a mutation in the factor V gene that participates in forming clots in response to an injury, for example. Without two fully functional factor V genes, the body’s ability to put a brake on clot formation is inhibited.

Normally, a molecule called activated protein C, or APC, prevents clots from becoming too large by inactivating coagulation factor V. But factor V Leiden impairs this protein’s ability to suppress the coagulation factor because it is longer lasting and stickier.

A parent who carries the mutated gene has a 50 percent chance of passing it on to each child. Someone who inherits one mutated gene faces a five- to seven-fold increased risk of developing a serious and potentially life-threatening clot. Someone with two of the damaged genes has a 25- to 50-fold increased risk. Approximately one person in 5,000 among whites in the United States and Europe has two of the mutated genes.

Because the risk of suffering a clot is about one in 1,000 people a year in the general population, the increased risk associated with factor V Leiden is not to be taken lightly: 5 to 7 in 1,000 people each year for those with one mutant gene and 25 to 50 per 1,000 in those with two mutant genes. The risk is greatest in individuals who have more than one clotting defect, as well as in people who smoke or are overweight.

A Danish study of 9,253 adults found that in people who did not smoke, were not overweight and were younger than 40, the 10-year risk of clots and emboli was 1 percent in those with one mutated gene and 3 percent in those with two damaged genes. But the risk increased to 10 percent in people with one mutated gene and 51 percent in those with two abnormal genes if they smoked, were overweight and were older than 60.

Screening Two blood tests can detect factor V Leiden. One, the APC resistance assay, is 95 percent accurate and could be used for screening. It measures the anticoagulant response to activated protein C. A definitive but more costly diagnosis, also performed on blood, can be made by genetic analysis of the factor V gene.

One or both tests is recommended for people with D.V.T., pulmonary embolism, premature stroke, repeated miscarriage, a family history of clots or a known factor V mutation in a blood relative. Thus, Mr. Bloom’s three daughters should be tested, because each has a 50 percent chance of carrying the defective gene.

For people with a personal or family history of clots, testing can help avert clotting complications when they undergo major surgery, are treated for cancer, anticipate pregnancy or plan to take oral contraceptives, estrogen therapy or a drug like tamoxifen.

In women with factor V Leiden, for example, treatment with an anticoagulant during pregnancy can reduce the risk of pregnancy loss. Women needing contraception might be wise to avoid birth control pills and instead choose a method that would not increase their risk of clots. And a person who is hospitalized or needs surgery can be treated with blood thinners and mechanical compression boots.

Though factor V Leiden alone does not seem to raise the risk of arterial clots, something as simple as daily therapy with low-dose aspirin may help prevent a heart attack or stroke in people with factor V Leiden if they have additional risk factors.

Preventive action is also important during long periods of immobilization, including long car and plane rides. Drinking plenty of water to prevent dehydration, avoiding alcohol, taking frequent walks and wearing elastic stockings can lower the risk of clots on such excursions.

Think about Factor V Leiden when you are dealing with

- Deep Vein Thrombosis

- Pulmonary Embolism

- Heart attack at early age

- Premature Stroke

- Recurrent Miscarriages

What Is Deep Vein Thrombosis?

Deep vein thrombosis (throm-BO-sis), or DVT, is a blood clot that forms in a vein deep in the body. Blood clots occur when blood thickens and clumps together.

Most deep vein blood clots occur in the lower leg or thigh. They also can occur in other parts of the body.

A blood clot in a deep vein can break off and travel through the bloodstream. The loose clot is called an embolus (EM-bo-lus). It can travel to an artery in the lungs and block blood flow. This condition is called pulmonary embolism (PULL-mun-ary EM-bo-lizm), or PE.

PE is a very serious condition. It can damage the lungs and other organs in the body and cause death.

Blood clots in the thighs are more likely to break off and cause PE than blood clots in the lower legs or other parts of the body. Blood clots also can form in veins closer to the skin's surface. However, these clots won't break off and cause PE.

Other Names for Deep Vein Thrombosis

- Blood clot in the leg.

- Thrombophlebitis.

- Venous thrombosis.

- Venous thromboembolism (VTE). This term is used for both deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism.

What Causes Deep Vein Thrombosis?

Blood clots can form in your body's deep veins if:

- A vein's inner lining is damaged. Injuries caused by physical, chemical, or biological factors can damage the veins. Such factors include surgery, serious injuries, inflammation, and immune responses.

- Blood flow is sluggish or slow. Lack of motion can cause sluggish or slow blood flow. This may occur after surgery, if you're ill and in bed for a long time, or if you're traveling for a long time.

- Your blood is thicker or more likely to clot than normal. Some inherited conditions (such as factor V Leiden) increase the risk of blood clotting. Hormone therapy or birth control pills also can increase the risk of clotting.

Who Is at Risk for Deep Vein Thrombosis?

The risk factors for deep vein thrombosis (DVT) include:

- A history of DVT.

- Conditions or factors that make your blood thicker or more likely to clot than normal. Some inherited blood disorders (such as factor V Leiden) will do this. Hormone therapy or birth control pills also increase the risk of clotting.

- Injury to a deep vein from surgery, a broken bone, or other trauma.

- Slow blood flow in a deep vein due to lack of movement. This may occur after surgery, if you're ill and in bed for a long time, or if you're traveling for a long time.

- Pregnancy and the first 6 weeks after giving birth.

- Recent or ongoing treatment for cancer.

- A central venous catheter. This is a tube placed in a vein to allow easy access to the bloodstream for medical treatment.

- Older age. Being older than 60 is a risk factor for DVT, although DVT can occur at any age.

- Overweight or obesity.

- Smoking.

What Are the Signs and Symptoms of Deep Vein Thrombosis?

The signs and symptoms of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) might be related to DVT itself or pulmonary embolism (PE). See your doctor right away if you have signs or symptoms of either condition. Both DVT and PE can cause serious, possibly life-threatening problems if not treated.

Deep Vein Thrombosis

Only about half of the people who have DVT have signs and symptoms. These signs and symptoms occur in the leg affected by the deep vein clot. They include:

- Swelling of the leg or along a vein in the leg

- Pain or tenderness in the leg, which you may feel only when standing or walking

- Increased warmth in the area of the leg that's swollen or painful

- Red or discolored skin on the leg

Some people aren't aware of a deep vein clot until they have signs and symptoms of PE. Signs and symptoms of PE include:

- Unexplained shortness of breath

- Pain with deep breathing

- Coughing up blood

How Is Deep Vein Thrombosis Diagnosed?

Your doctor will diagnose deep vein thrombosis (DVT) based on your medical history, a physical exam, and test results. He or she will identify your risk factors and rule out other causes of your symptoms.

For some people, DVT might not be diagnosed until after they receive emergency treatment for pulmonary embolism (PE).

Medical History

To learn about your medical history, your doctor may ask about:

- Your overall health

- Any prescription medicines you're taking

- Any recent surgeries or injuries you've had

- Whether you've been treated for cancer

Your doctor will check your legs for signs of DVT, such as swelling or redness. He or she also will check your blood pressure and your heart and lungs.

Diagnostic Tests

Your doctor may recommend tests to find out whether you have DVT.

Common Tests

The most common test for diagnosing deep vein blood clots is ultrasound. This test uses sound waves to create pictures of blood flowing through the arteries and veins in the affected leg.

Your doctor also may recommend a D-dimer test or venography (ve-NOG-rah-fee).

A D-dimer test measures a substance in the blood that's released when a blood clot dissolves. If the test shows high levels of the substance, you may have a deep vein blood clot. If your test results are normal and you have few risk factors, DVT isn't likely.

Your doctor may suggest venography if an ultrasound doesn't provide a clear diagnosis. For venography, dye is injected into a vein in the affected leg. The dye makes the vein visible on an x-ray image. The x ray will show whether blood flow is slow in the vein, which may suggest a blood clot.

Other Tests

Other tests used to diagnose DVT include magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (to-MOG-rah-fee), or CT, scanning. These tests create pictures of your organs and tissues.

You may need blood tests to check whether you have an inherited blood clotting disorder that can cause DVT. This may be the case if you have repeated blood clots that are not related to another cause. Blood clots in an unusual location (such as the liver, kidney, or brain) also may suggest an inherited clotting disorder.

If your doctor thinks that you have PE, he or she may recommend more tests, such as a lung ventilation perfusion scan (VQ scan). A lung VQ scan shows how well oxygen and blood are flowing to all areas of the lungs.

For more information about diagnosing PE, go to the Health Topics Pulmonary Embolism article.

How Is Deep Vein Thrombosis Treated?

Doctors treat deep vein thrombosis (DVT) with medicines and other devices and therapies. The main goals of treating DVT are to:

- Stop the blood clot from getting bigger

- Prevent the blood clot from breaking off and moving to your lungs

- Reduce your chance of having another blood clot

Your doctor may prescribe medicines to prevent or treat DVT.

Anticoagulants

Anticoagulants (AN-te-ko-AG-u-lants) are the most common medicines for treating DVT. They're also known as blood thinners.

These medicines decrease your blood's ability to clot. They also stop existing blood clots from getting bigger. However, blood thinners can't break up blood clots that have already formed. (The body dissolves most blood clots with time.)

Blood thinners can be taken as a pill, an injection under the skin, or through a needle or tube inserted into a vein (called intravenous, or IV, injection).

Warfarin and heparin are two blood thinners used to treat DVT. Warfarin is given in pill form. (Coumadin® is a common brand name for warfarin.) Heparin is given as an injection or through an IV tube. There are different types of heparin. Your doctor will discuss the options with you.

Your doctor may treat you with both heparin and warfarin at the same time. Heparin acts quickly. Warfarin takes 2 to 3 days before it starts to work. Once the warfarin starts to work, the heparin is stopped.

Pregnant women usually are treated with just heparin because warfarin is dangerous during pregnancy.

Treatment for DVT using blood thinners usually lasts for 6 months. The following situations may change the length of treatment:

- If your blood clot occurred after a short-term risk (for example, surgery), your treatment time may be shorter.

- If you've had blood clots before, your treatment time may be longer.

- If you have certain other illnesses, such as cancer, you may need to take blood thinners for as long as you have the illness.

Sometimes the bleeding is internal (inside your body). People treated with blood thinners usually have regular blood tests to measure their blood's ability to clot. These tests are called PT and PTT tests.

These tests also help your doctor make sure you're taking the right amount of medicine. Call your doctor right away if you have easy bruising or bleeding. These may be signs that your medicines have thinned your blood too much.

Thrombin Inhibitors

These medicines interfere with the blood clotting process. They're used to treat blood clots in patients who can't take heparin.

Thrombolytics

Doctors prescribe these medicines to quickly dissolve large blood clots that cause severe symptoms. Because thrombolytics can cause sudden bleeding, they're used only in life-threatening situations.

Other Types of Treatment

Vena Cava FilterIf you can't take blood thinners or they're not working well, your doctor may recommend a vena cava filter.

The filter is inserted inside a large vein called the vena cava. The filter catches blood clots before they travel to the lungs, which prevents pulmonary embolism. However, the filter doesn't stop new blood clots from forming.

Graduated Compression Stockings

Graduated compression stockings can reduce leg swelling caused by a blood clot. These stockings are worn on the legs from the arch of the foot to just above or below the knee.

Compression stockings are tight at the ankle and become looser as they go up the leg. This creates gentle pressure up the leg. The pressure keeps blood from pooling and clotting.

There are three types of compression stockings. One type is support pantyhose, which offer the least amount of pressure.

The second type is over-the-counter compression hose. These stockings give a little more pressure than support pantyhose. Over-the-counter compression hose are sold in medical supply stores and pharmacies.

Prescription-strength compression hose offer the greatest amount of pressure. They also are sold in medical supply stores and pharmacies. However, a specially trained person needs to fit you for these stockings.

Talk with your doctor about how long you should wear compression stockings.

How Can Deep Vein Thrombosis Be Prevented?

You can take steps to prevent deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE). If you're at risk for these conditions:

- See your doctor for regular checkups.

- Take all medicines as your doctor prescribes.

- Get out of bed and move around as soon as possible after surgery or illness (as your doctor recommends). Moving around lowers your chance of developing a blood clot.

- Exercise your lower leg muscles during long trips. This helps prevent blood clots from forming.

- Take all medicines that your doctor prescribes to prevent or treat blood clots

- Follow up with your doctor for tests and treatment

- Use compression stockings as your doctor directs to prevent leg swelling

Travel Tips

The risk of developing DVT while traveling is low. The risk increases if the travel time is longer than 4 hours or you have other DVT risk factors.

During long trips, it may help to:

- Walk up and down the aisles of the bus, train, or airplane. If traveling by car, stop about every hour and walk around.

- Move your legs and flex and stretch your feet to improve blood flow in your calves.

- Wear loose and comfortable clothing.

- Drink plenty of fluids and avoid alcohol.

Living With Deep Vein Thrombosis

If you've had a deep vein blood clot, you're at greater risk for another one. During treatment and after:

- Take steps to prevent deep vein thrombosis (DVT). (For more information, go to "How Can Deep Vein Thrombosis Be Prevented?")

- Check your legs for signs of DVT. These include swollen areas, pain or tenderness, increased warmth in swollen or painful areas, or red or discolored skin on the legs.

- Contact your doctor right away if you have signs or symptoms of DVT.

DVT often is treated with blood-thinning medicines. These medicines can thin your blood too much and cause bleeding (sometimes inside the body). This side effect can be life threatening.

Bleeding can occur in the digestive system or the brain. Signs and symptoms of bleeding in the digestive system include:

- Bright red vomit or vomit that looks like coffee grounds

- Bright red blood in your stools or black, tarry stools

- Pain in your abdomen

- Severe pain in your head

- Sudden changes in your vision

- Sudden loss of movement in your arms or legs

- Memory loss or confusion

You might want to wear a medical ID bracelet or necklace that states you're at risk of bleeding. If you're injured, the ID will alert medical personnel of your condition.

Talk with your doctor before taking any medicines other than your DVT medicines. This includes over-the-counter medicines. Aspirin, for example, also can thin your blood. Taking two medicines that thin your blood may raise your risk of bleeding.

Ask your doctor about how your diet affects these medicines. Foods that contain vitamin K can change how warfarin (a blood-thinning medicine) works. Vitamin K is found in green, leafy vegetables and some oils, like canola and soybean oils. Your doctor can help you plan a balanced and healthy diet.

Discuss with your doctor whether drinking alcohol will interfere with your medicines. Your doctor can tell you what amount of alcohol is safe for you.

Clinical TrialsThe National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) is strongly committed to supporting research aimed at preventing and treating heart, lung, and blood diseases and conditions and sleep disorders.

Researchers have learned a lot about blood disorders over the years. That knowledge has led to advances in medical knowledge and care. However, many questions remain about various blood disorders, including deep vein thrombosis (DVT).