- RETIREMENT ANNOUNCEMENT

- HOME PAGE

- "MYCHART" the new patient portal

- BELMONT MEDICAL ASSOCIATES

- MOUNT AUBURN HOSPITAL

- EMERGENCIES

- PRACTICE PHILOSOPHY

- MY RESUME

- TELEMEDICINE CONSULTATION

- CONTACT ME

- LAB RESULTS

- ePRESCRIPTIONS

- eREFERRALS

- RECORD RELEASE

- MEDICAL SCRIBE

- PHYSICIAN ASSISTANT (PA)

- Medicare Annual Wellness Visit

- Case management/Social work

- Quality Care Measures

- Emergency closing notice

- FEEDBACK

- Talking to your doctor

- Choosing..... and losing a doctor

- INDEX A - Z

- ALLERGIC REACTIONS

- Alternative Medicine

- Alzheimer's Disease

- Bladder Problems

- Blood disorders

- Cancer Concerns

- GENETIC TESTING FOR HEREDITARY CANCER

- Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

- Controversial Concerns

- CPR : Learn and save a life

- CRP : Inflammatory marker

- Diabetes Management

- Dizziness, Vertigo,Tinnitus and Hearing Loss

- EXERCISE

- FEMALE HEALTH

-

GASTROINTESTINAL topics

- Appendicitis

- BRAT diet

- Celiac Disease or Sprue

- Crohn's Disease

- Gastroenterologists for Colon Cancer Screening

- Colonoscopy PREP

- Constipation

- Gluten sensitivity, but not celiac disease

- Heartburn and GERD

- Hemorrhoids and Anal fissure

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- NASH : Non Alcoholic Steato Hepatitis

- FEET PROBLEMS

- HEART RELATED topics

-

INFECTIOUS DISEASES

- Antibiotic Resistance

- Cat bites >

- Clostridia difficile infection - the "antibiotic associated germ"

- CORONA VIRUS

- Dengue Fever and Chikungunya Fever

- Food borne illnesses

- Shingles Vaccine

- Hepatitis B

- Hepatitis C

- Herpes

- Influenza

- Helicobacter pylori - the "ulcer germ"

- HIV Screening

- Lyme and other tick borne diseases

- Measles

- Meningitis

- MRSA (Staph infection)

- Norovirus

- Sexually Transmitted Diseases

- Shingles (Herpes Zoster)

- Sinusitis

- West Nile Virus

- Whooping Cough (Pertussis)

- Zika virus and pregnancy

- INSURANCE related topics

- KIDNEY STONES

- LEG CRAMPS

- LIBRARY for patients

- LIFE DECISIONS

- MALE HEALTH

- Medication/Drug side effects

- MEDICAL MARIJUANA

- MENTAL HEALTH

- Miscellaneous Articles

-

NUTRITION - EXERCISE - WEIGHT

- Cholesterol : New guidelines for treatment

- Advice to lower your cholesterol

- Cholesterol : Control

- Cholesterol : Raising your HDL Level

- Exercise

- Food : Making Smart Choices

- Food : Making Poor Choices

- Food : Grape Fruit and Drug Interaction

- Food : Vitamins, Minerals and Supplements

- Omega 3 fatty acids

- Vitamin B12 deficiency

- Vitamin D

- Weight Loss

- ORTHOPEDICS

- PAIN

- PATIENTS' RIGHTS

- SKIN

- SLEEP

- SMOKING

- STROKE

- THYROID

- SUBSTANCE ABUSE

- Travel and Vaccination

- TREMOR

- Warfarin Anticoagulation

- OTHER STUFF FOLLOWS

- Fact or Opinion?

- Hippocratic Oath

- FREE ADVICE.......for what its worth!

- LAUGHTER.....is the best medicine

- Physicians Pet Peeves

- PHOTO ALBUM - its not all work!

- Cape Town, South Africa

- Tribute page

- The 100 Club

- Free Wi-Fi

Dizziness, Vertigo and Tinnitus

Getting Specific About Dizziness

By Jane E. Brody : NY Times : Feb. 6, 2017

Dizziness is not a disease but rather a symptom that can result from a huge variety of underlying disorders or, in some cases, no disorder at all. Readily determining its cause and how best to treat it — or whether to let it resolve on its own — can depend on how well patients are able to describe exactly how they feel during a dizziness episode and the circumstances under which it usually occurs.

For example, I recently experienced a rather frightening attack of dizziness, accompanied by nausea, at a food and beverage tasting event where I ate much more than I usually do. Suddenly feeling that I might faint at any moment, I lay down on a concrete balcony for about 10 minutes until the disconcerting sensations passed, after which I felt completely normal.

The next morning I checked the internet for my symptom — dizziness after eating — and discovered the condition had a name: Postprandial hypotension, a sudden drop in blood pressure when too much blood is diverted to the digestive tract, leaving the brain relatively deprived. The condition most often affects older adults who may have an associated disorder like diabetes, hypertension or Parkinson’s disease that impedes the body’s ability to maintain a normal blood pressure. Fortunately, I am thus far spared any disorder linked to this symptom, but I’m now careful to avoid overeating lest it happen again.

“An essential problem is that almost every disease can cause dizziness,” say two medical experts who wrote a comprehensive new book, “Dizziness: Why You Feel Dizzy and What Will Help You Feel Better.” Although the vast majority of patients seen at dizziness clinics do not have a serious health problem, the authors, Dr. Gregory T. Whitman and Dr. Robert W. Baloh, emphasize that doctors must always “be on the alert for a serious disease presenting as ‘dizziness,’” like “stroke, transient ischemic attacks, multiple sclerosis and brain tumors.”

Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo can be caused by a blow to the head or be a result of aging. “Approximately one in five people in their 80s will develop B.P.P.V.,” the authors wrote. It can also affect younger people, particularly those who already have, or will develop, migraine headaches, they noted.Dr. Kevin A. Kerber, a neurotologist at the University of Michigan Health System, told me that dizziness is one of the most common symptoms that primary care and emergency department doctors see, as common as back pain and headache. He cited a nationally representative health survey conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 2008 in which 10 percent of adults said they had felt dizzy within the past year and had been referred to or seen by a health care specialist because of the symptom.

Typically, those reporting dizziness in the survey indicated they each had experienced three of the following different types: a spinning or vertigo sensation, including a rocking of yourself or your surroundings; a floating, spacey or tilting sensation; feeling lightheaded, without a sense of motion; feeling as if you are going to pass out or faint; blurring of your vision when you move your head; or feeling off-balance or unsteady.

As you can see, reporting a symptom simply as dizziness does not give a doctor much to go on. A major problem, Dr. Kerber said, is that the examining doctor has to decide on the type of dizziness and determine whether there may be a “particularly dangerous cause” like a heart attack or stroke based on “often unreliable” descriptions by patients.

People use the word dizziness when referring to lightheadedness, unsteadiness, motion intolerance, imbalance, floating or a tilting sensation. Vertigo, a subtype of dizziness, is an illusion of movement caused by uneven input to the inner ear’s vestibular system that provides a sense of balance and orientation in space. In 2011, an estimated 3.9 million people visited emergency departments with symptoms of dizziness or vertigo.

“Patients are generally nonspecific in describing their symptoms,” Dr. Kerber said. “They should spend time thinking about their symptoms before they see the doctor.” Factors to consider, he said, include “timing — does the dizziness occur episodically or is it constant? What seems to set it off — certain positions or particular foods? How long does the symptom last? And what happens over time — does it get worse, stay the same or get better?”

Note, too, whether the feelings get worse when you walk, stand up or move your head. Are the episodes accompanied by nausea, and do they occur so suddenly and severely that they force you to sit or lie down?

Family members or friends who pay attention to the affected individual’s complaints “can help contribute to a rapid and correct diagnosis,” according to the authors of the new book. Dr. Whitman is an otoneurology specialist at Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary, and Dr. Baloh is director of the neurotology clinic and testing laboratory at the medical center of the University of California, Los Angeles.

Two of the most common causes of dizziness are triggered by changes in position. One is called orthostatic hypotension — a reduced flow of blood to the brain that occurs when a person gets up from a sitting or lying position and goes away when the person lies down.

The second, called benign paroxysmal positional vertigo, or B.P.P.V., is not exactly benign to those affected, Dr. Kerber said. It is triggered by a change in head position, for example, when lying down, turning over in bed, or bending the head backward while sitting or standing (called “top shelf vertigo”), the authors of “Dizziness” wrote. The person may feel that the world is moving or spinning or that an object in the room is jumping up and down rhythmically.

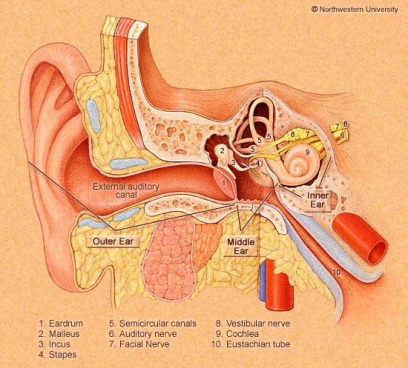

Vertigo is one of the most disabling causes of dizziness. It arises when tiny calcium particles in the inner ear become dislodged from the balance organ and get stuck in the semicircular canal, where “they cause havoc,” Dr. Kerber explained. When the head is moved, the particles shift and set off a sensitive nerve wired to the eyes, making them jerk and causing dizziness. When the particles settle down, the eyes stop jerking and the dizziness goes away.

Vertigo can be a disabling condition that lasts for weeks, months or even years. Those affected are often unable to work, drive or walk around without falling.

However, B.P.P.V. usually responds to a treatment like the Epley maneuver, a sequence of movements that re-positions the head and gets the errant particles to go back to where they belong. The maneuver is often performed by a health professional, but patients can learn to do it on their own if the vertigo recurs.

Symptom: Dizziness.

Cause: Often Baffling.

By Richard Saltus : NY Times Article : September 6, 2005

On the Fourth of July, a 63-year-old man was taken by wheelchair into the emergency room of a suburban Virginia hospital, overwhelmed with dizziness and nausea and gripped by sweat-inducing anxiety.

"I felt dim and lightheaded, like I was just going to fade out," said John Farquhar, a semiretired consultant in Washington. "I said, 'I'm going to die.' "

His wife, Lou, a nurse, had driven him to the hospital, taking big curves gingerly because the motion of a sweeping turn "made me feel like I was pulling 30 G's like a fighter pilot," said Mr. Farquhar, who otherwise was healthy and fit.

The attacks had begun the previous day, out of the blue, while he was playing with the couple's dog, Sascha.

Lifting her high in the air, "I snapped my head back, and suddenly it seemed that my body was turning, and the room was spinning around," Mr. Farquhar recounted. "I felt profoundly dizzy and nauseated."

The episode passed, but the queasiness returned not long afterward, set off by the on-screen action on a DVD. When Mr. Farquhar got out of bed the next day, the world was spinning so violently that he crumpled to his knees, and he could barely make his way to the bathroom, where he vomited, leading to the trip to the E.R.

Dizziness is one of the most miserable of sensations, and it can be disabling.

The technical term for the false sensation that you and the world are spinning is vertigo. (In Alfred Hitchcock's film "Vertigo," the James Stewart character actually suffers from acrophobia, or fear of heights.)

There are many causes of vertigo, most of them temporary and treatable, but sometimes the condition signals a serious problem, like a tumor \nor a stroke. Dizziness and lightheadedness are among the most frequent complaints that cause people to seek medical help.

Although doctors often see patients with the symptom, its cause can be a challenge to determine, said Dr. Jonathan Olshaker, chief of the emergency department at Boston Medical Center, who has written a textbook chapter on vertigo.

"The staff has a concern that they're not going to be able to figure out what it is, or that the person is a difficult-to-treat patient," Dr. Olshaker said. In fact, a vast majority of patients have a specific, identifiable cause for their dizziness, he said.

Even when the cause is probably not serious, doctors generally are cautious, ordering a number of tests and sometimes consulting with neurologists to make sure the cause of the vertigo is not life-threatening.

Ruling out life-threatening causes, the doctors told Mr. Farquhar that he was most likely suffering from benign paroxysmal positional vertigo.

The problem accounts for perhaps 25 to 40 percent of patients seeking medical attention for dizziness. "Paroxysmal" refers to the episodic pattern of vertigo attacks, and "positional" means that the spinning sensations are brought on by certain movements.

Tilting the head back to look upward is a typical trigger. The disorder has been nicknamed "top-shelf vertigo," and hair salon customers sometimes experience it when leaning back for a shampoo, as do patients sitting in dental chairs.

The diagnosis and treatment of vertigo have markedly improved in the last two decades. The cause of most benign positional vertigo is now believed to be calcium debris that has dislodged from a part of the inner ear and strayed into one of the fluid-filled semicircular canals of the sensitive vestibular system.

The system is a cluster of structures that keeps the brain updated on the body's orientation and movement in space.

These microscopic flecks of calcium debris do not in themselves lead to problems, but sometimes in their meandering they brush against delicate, hairlike cells, sending misinformation to the brain.

When those signals conflict with more accurate signals from other nerves, the brain responds with disorientation and vertigo.

The three semicircular canals of the inner ear loop out - more or less at right angles, like three edges of a box meeting at the corner - from a chamber called the vestibule.

The slight fluid movements in these canals in response to head movements and gravity activate the hair-trigger cells that relay positional information to the brain.

Inside the vestibule, scores of tiny "stones" called otoliths are attached to \na membrane, and when the head turns in any direction, the slight force imparted to the otoliths is translated into nerve messages about motion and orientation. B.P.P.V., a common cause of dizziness caused by a malfunction of the inner ear's balance mechanism.

The problem accounts for perhaps 25 to 40 percent of patients seeking medical attention for dizziness. "Paroxysmal" refers to the episodic pattern of vertigo attacks, and "positional" means that the spinning sensations are brought on by certain movements.

The diagnosis and treatment of vertigo have markedly improved in the last two decades. The cause of most benign positional vertigo is now believed to be calcium debris that has dislodged from a part of the inner ear and strayed into one of the fluid-filled semicircular canals of the sensitive vestibular system.

The maneuvers involve moving the head into four different positions sequentially, taking advantage of gravity to roll the calcium flecks out of the sensitive part of the canal to a place where they cause less trouble.

In cases like Mr. Farquhar, the Epley maneuvers are repeated, the patient sits up, and the treatment is complete. For the next 48 hours, Mr. Farquhar was cautioned to avoid a variety of movements that could send the debris tumbling back into the canal.

Most doctors who do this say that 80 percent of patients have their symptoms alleviated in one set of treatments," Dr. Fitzgerald says.

The remaining 20 percent, he added, need repeated treatments, and the overall recurrence rate is 25 percent to 30 percent, though the episodes may not come back for months or years.

Within a few days, Mr. Farquhar was much improved and was able to walk several blocks and go into his office to work. Two months later, he continued to be free of nearly all his symptoms, except a brief lingering feeling of unease just after waking up in the morning.

For all but the most intractable cases, which occasionally require surgery, the simple and low-tech Epley maneuvers rank among the most effective and certainly the least costly of treatments for such a common and disabling source \nof misery.

"Vertigo is a horrible feeling," said Dr. Olshaker, the Boston emergency room chief. "The physician does need to have empathy for these patients. And in recent time, we're seeing more awareness of the condition and the Epley maneuvers, both in the E.R. and the primary care clinic."

A Stable Life, Despite Persistent Dizziness

By Jane E. Brody : NY Times Article : January 15, 2008

On the subway, children twirl themselves around the poles in the cars until they are so dizzy I’m ready to catch them. The young seem to delight in making the world spin out of control for a few moments, causing them to flop about like drunks. But when dizziness, vertigo or loss of balance is neither self-imposed nor short lived, it is anything but fun. It can throw one’s whole life out of kilter, literally and figuratively.This is what befell Cheryl Schiltz in 1997, when long treatment with the antibiotic gentamicin permanently damaged the vestibular apparatus in her inner ear. For three years, said Ms. Schiltz, of Madison, Wis., her world seemed to be made of Jell-O. Lacking a sense of balance, she wobbled with every step, and everything she looked at jiggled and tilted.Unable to work, Ms. Schiltz became increasingly isolated and struggled to perform the simplest household tasks.

Lisa Haven, executive director of the Vestibular Disorders Association, reports that “the risk of falling is two to three times greater in people with chronic imbalance or dizziness.” Nearly 9 percent of Americans 65 and older have balance problems, the prevalence of which is likely to increase as the 78 million baby boomers age.

Four Types of Dizziness :

The job of the vestibular system is to integrate sensory stimuli and movement for the brain and keep objects in visual focus as the body moves. When the head moves, signals are sent to the inner ear, an organ consisting of three semicircular canals surrounded by fluid. It in turn sends movement information to the vestibular nerve, which carries it to the brainstem and cerebellum, which control balance and posture and coordinate movement. Disruption of any part of the system can result in dizziness.

These are four types of dizziness, all of which are more common with increasing age:

What to Tell the Doctor:

About 40 percent of people experience at least one of these forms of dizziness at some time during their lives. When dizziness persists, medical care is essential, and so is the ability to provide a detailed description of the symptoms and what provokes them.

For example, for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo, a simple head-turning maneuver that repositions crystals in the inner ear may bring lasting relief. If ministrokes are the cause, the treatment may involve anticlotting drugs or opening a blocked artery with a stent. If medication is the problem, adjusting the dose or changing the drug can relieve dizziness. If dizziness persists despite treatment, lifestyle adjustments can help like avoiding sudden movements, keeping often-used items within easy reach, standing up slowly and clenching hands and flexing feet before standing. Physical therapy can help, as can exercises that strengthen muscles and that combine eye, head and body movements.Ms. Schiltz, whose vestibular system was damaged a decade ago, said she was told that nothing could be done about it. Nothing, that is, until she became the first patient to be treated with a device called a BrainPort invented by the late Dr. Paul Bach-y-Rita, a neurobiologist and rehabilitation medicine specialist, and his colleagues at the University of Wisconsin. The device takes advantage of the acute sensitivity of the tongue and sends balance signals directly to the brain from the tongue, bypassing the ear’s vestibular apparatus. At first, she used it a few minutes at a time, but soon found longer use kept her in balance for hours, then days, then weeks and months. Eventually, all that was needed was 20 minutes twice a day to train her brain, and she now uses it just occasionally.She is among more than 100 study participants who have used the BrainPort, including patients with multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease and stroke. The device is available commercially in Canada and is awaiting approval by the Food and Drug Administration in the United States.Dr. Norman Doidge of the research faculty at the Columbia University Psychoanalytic Center and the University of Toronto describes Ms. Schiltz’s dramatic recovery in his new book about the plasticity of the brain, “The Brain That Changes Itself.” (Her case was also described in Science Times in November 2004.) With her sense of balance intact, Ms. Schiltz was able to return to school and on Dec. 20 received a degree in rehabilitation psychology.“I feel like a restored, even enhanced, person,” she said in an interview. “I’m living proof that the brain can be retrained. My goal now is to help people with acquired disabilities gain increased independence.”

New Views of Motion Sickness

Travel-Related Nausea Puzzles Scientists Amid Search for a Better Remedy; Ginger Root or a Nasal Spray?

Sumathi Reddy : WSJ : June 18, 2013

Researchers from the Navy, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration and academia are studying causes and potential treatments of motion sickness, hoping to formulate better products for situations that range from the extreme (space!) to the mundane (road trip to Grandma's, anyone?).

There's nothing quite like motion sickness to ruin summer travel, with symptoms including dizziness, headache, nausea and most unfortunately, vomiting. Some 25% to 40% of the population suffers from some degree of motion sickness, depending on the mode of transportation.

At Siena College, in Loudonville, N.Y., researchers have studied the effectiveness of ginger capsules, facial cooling and listening to music as a distraction for lessening symptoms and physiological responses to motion sickness.

NASA and the Navy are collaborating with pharmaceutical company Epiomed Therapeutics, of Irvine, Calif., to develop a nasal spray containing scopolamine, a drug currently used in a prescription-only patch for those prone to seasickness. Researchers say the drug's strong possible side effects, such as drowsiness and dry mouth, would be significantly reduced with a nasal spray.

Part of the difficulty with devising treatments is that experts don't know exactly what causes motion sickness. The prevailing belief is it is caused by a sensory mismatch between the visual and vestibular systems. The vestibular system, which is part of the inner ear, monitors movement and helps control balance.

In other words, our inner ear tells our brain that we are moving, but our eyes tell us we aren't, or vice versa. "When one of these is telling you you're in motion and the other one is telling you you're sitting, the brain gets confused with the mixed signals, and it causes this sense of sickness," says Abinash Virk, director of the travel and tropical medicine clinic at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

What remain unknown are the reasons why the mismatch causes some individuals to react adversely. One long-standing theory is that the reactions are triggered by the brain's false identification of a toxin in the body, with nausea and vomiting a protective response to get rid of it.

Another theory is that body sway, or the change in a person's movements over short time intervals, can explain a propensity to get motion sickness. In Tom Stoffregen's lab at the University of Minnesota, the kinesiology professor measures each subject's body sway over a short period. He has found that individuals who are more susceptible have a more-erratic sway during and even before they are exposed to any stimulation.

Dr. Stoffregen uses a force plate, a glorified bathroom scale with pressure sensors, to take measurements of body movement as often as 200 times a second. He studies people both in a lab simulator and on ships.

In a forthcoming study to be published in the online journal PLOS ONE, Dr. Stoffregen tested the body sway of 35 cruise passengers aboard a ship in the Caribbean before departure. Passengers then reported the intensity of their seasickness. He found a link: Those who reported getting more sea sickness had more body sway at the dock.

"There may be sort of a general classification that people who are susceptible to motion sickness have," Dr. Stoffregen said. "Maybe they just move differently in general."

Max Levine, an associate professor of psychology at Siena College, studies behavioral and alternative motion-sickness treatments. In a recent experiment on about 50 individuals, half received capsules with ginger root and the remainder got a placebo. Then the individuals were seated in a chamber and exposed to a rotating device called an optokinetic drum that induces motion sickness.

"The folks who got ginger beforehand ended up doing much better both in terms of the symptoms they developed and in terms of the physiological reaction that they had in the stomach," he said.

Recent behavioral experiments have found that cool compresses or gel packs placed on the forehead are somewhat effective at controlling physiological changes, such as abnormal rhythmic stomach activity that generally accompanies nausea, but didn't significantly reduce nausea. Listening to one's favorite music as a distraction showed improvements in symptoms including nausea, as well as in physiological changes, Dr. Levine said. Now, Dr. Levine is studying how deep breathing and relaxation may aid in motion sickness.

Doctors say a common misperception is that traveling on an empty stomach helps. Wrong. It's better to eat a light meal beforehand, especially one high in protein.

In a 2004 study in Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 18 individuals completed three trials. In one, they had a protein drink before exposure to a device that induces motion sickness. In a second trial, they had a carbohydrate drink, and the third time they had nothing. They fared best after the protein drink. Protein "really tends to get the stomach into that slow normal rhythmic activity more so than fats and carbohydrates," Dr. Levine said.

Children over age 2 seem more prone to motion sickness than adults. Some experts think children's extra-sharp senses may make them aware of even a slight mismatch. Adults in their golden years seem to experience motion sickness less often—perhaps because of habituation.

Women have a greater tendency than men to get motion sickness. Some experts believe this is because women also are more prone to getting migraines, and migraine sufferers have a higher rate of motion sickness. Or women may simply report motion sickness symptoms more often.

Doctors say prescription drugs and over-the-counter options like Dramamine are the best treatment option, though some can cause side effects. Such drugs work by suppressing the central nervous system's response to nausea-producing stimuli. They reduce symptoms for many people but aren't universally effective.

Some travelers rely on homeopathic remedies such as ginger or acupressure wrist bands. Sujana Chandrasekhar, director of New York Otology in New York City, said they aren't universally effective, but are "worth trying."

There are behavioral tips for preventing or minimizing symptoms. Cynthia Ryan knows them all. The 45-year-old Portland, Ore., resident has suffered from motion sickness since she was a child commuting to school along winding roads, her barf bag in hand. Now the executive director of the Vestibular Disorders Association, Ms. Ryan says individuals with vestibular disorders are prone to motion sickness.

Her rule of thumb is to always be the driver. "I almost never let somebody else drive," she said. "And if I do, I sit in the passenger seat." Even when sitting as the front passenger, Ms. Ryan says she does deep-breathing exercises and tries to focus on a fixed point on the road in front of her. "I can't participate in conversations," she said. "I can't read. Sometimes someone will pass me a smartphone and say, 'Can you read me the directions?' And I'll say, 'Not unless you want me to throw up in your car.' "

Watching television TV or reading in a car is a no-no. "Face forward in the vehicle to be as alert to what's happening outside the vehicle as the driver would be," Dr. Chandrasekhar said. "You want to try to match your eyes to what's going on and to what your inner ear is feeling." Experts say: Just close your eyes and sleep.

Living With a Sound You Can’t Turn Off

By Jane E. Brody : NY Times : December 3, 2012

Shortly after my 70th birthday, a high-pitched hum began in my left ear. I noticed it only during quiet times but soon realized that it never went away.

An ear, nose and throat specialist (otolaryngologist) examined my ears and took a thorough medical history that included questions about noise exposure and drugs I take. An audiologist checked my hearing.

Diagnosis: tinnitus, with a mild hearing loss in the upper range that closely matched the pitch of the hum.

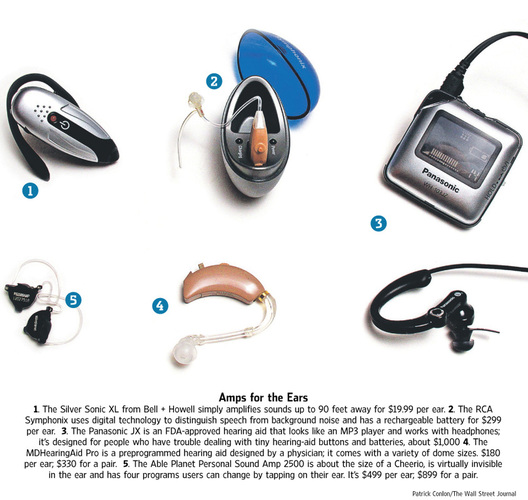

Although the hum was not particularly disturbing, I asked what might be done if it should get loud enough to interfere with my life and ability to hear speech clearly (about 85 percent of tinnitus cases are accompanied by hearing loss). The answer was that I could be fitted with a hearing aid.

But since my tinnitus is still mild, no mention was made of anything that might relieve the constant noise in my head.

Tinnitus is a chronic noise of varying intensity, loudness and pitch that has no external source. Rather, it seems to come from within a person's head. It is most apparent to the sufferer when all is quiet and may not be noticed when the person is otherwise distracted - while participating in physical activity, for example, or listening to music.

There is currently no cure for tinnitus, a potentially life-disrupting condition that affects about 10 to 20 percent of people, mostly those over age 65, but also many veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Among possible causes are head and neck injuries, drugs that damage the ear, blood vessel disease, autoimmune disorders, ear conditions and disorders of the temporomandibular joint.

Until recently, no treatment had been shown to have lasting effectiveness in controlled clinical trials, despite a host of remedies variously endorsed by hearing specialists and commercial interests.

In addition to a hearing aid, the most commonly prescribed remedy is a so-called masking device, a white-noise machine that introduces natural or artificial sound into the sufferer's ears in an attempt to suppress the perceived ringing. But eventually the noise of the masker can become as disruptive as the tinnitus.

"When patients respond poorly to the masking device, they are often told they haven't used it long or consistently enough," said Rilana F. F. Cima, a psychologist and researcher in the Netherlands.

Fear and Anxiety

Dr. Cima said in an interview that, like me, most people with tinnitus function fairly well. But for about 3 percent of people with the condition, it is extremely disabling, causing intense distress, fear and anxiety, and leaving them unable to function.

"Patients say the sound is driving them crazy," Dr. Cima said. "Their negative reaction to not wanting to hear it creates daily life impairment." She said patients would do almost anything to avoid hearing the sound in their heads and the feelings of fear and anxiety that result.

Recently Dr. Cima's team demonstrated the effectiveness of a multidisciplinary, psychology-based approach to this problem. The technique, published last spring in The Lancet, does not make the ringing go away, but it does show that now there is real hope for relief for people whose tinnitus impairs their ability to work, sleep and enjoy life.

In an accompanying editorial, Dr. Berthold Langguth of the University of Regensburg in Germany, an international authority on tinnitus, said the team's findings "overcome the idea that nothing can be done to treat tinnitus" and provide "a clear statement against therapeutic nihilism."

James Henry, a specialist in auditory rehabilitation at the Veterans Administration Medical Center in Portland, Ore., where many veterans with traumatic brain injuries are treated for tinnitus, said that Dr. Cima had done "probably the best study to date, a good job that is advancing the field."

An Improved Approach

The three-month treatment developed and carefully tested by the Dutch team is based on cognitive behavioral therapy and relies on principles of exposure therapy long proven effective to treat phobias. While the use of cognitive behavioral therapy for tinnitus is not new, the team's demonstration of a scientifically validated, comprehensive approach to the problem offers a therapeutic blueprint that others can use.

Unlike the use of a tinnitus masker, the treatment is simple, relatively brief and does not require patients to purchase or use devices to gain relief. If necessary, patients who "relapse" can return for a brief therapeutic brush-up.

Dr. Cima's team enrolled 492 patients with varying degrees of tinnitus and randomly assigned them to receive either usual care or "specialized" care. Usual care, in the Netherlands as well as in the United States, involves a medical exam and hearing test, typically followed by a prescription for a hearing aid and/or masking device.

Patients may also be given antidepressants, anti-anxiety drugs, sleep aids or other medication to relieve emotional distress and other disabling symptoms.

The Dutch treatment relies solely on psychological techniques. Following an education session about tinnitus and lessons in deep relaxation, patients are gradually exposed to an external source of the very ringing they hear in their heads. After 10 or 12 sessions, they become habituated to it and no longer find it threatening.

It is not the noise itself but "patients' extremely negative reaction to it that creates daily life impairment," Dr. Cima explained. "Patients are continuously stressed and fearful of it. It becomes a sign of a danger from which they must escape."

She likened the approach to helping people overcome their fear of spiders by inducing deep relaxation and gradually introducing them to increasingly realistic objects of their fear.

"They may never learn to love spiders, but they can live with them more comfortably," Dr. Cima said.

Dr. Henry of the veterans medical center, who has been involved in tinnitus research for a quarter century, said his team uses a similar approach with five treatment sessions, which "takes care of about 95 percent of cases," he said.

"Lots of veterans get tinnitus in association with traumatic brain injuries, but the tinnitus is often permanent even after these other injuries are resolved," Dr. Henry said. "We teach them skills that enable them to manage their tinnitus. They learn to reframe the problem in a more positive way. It's not a cure - nobody has a cure - but we're able to help most veterans and enable them to live a normal life."

A cure may emerge from findings of changes in the brains of tinnitus patients that are being revealed through sophisticated imaging techniques.

New Therapies Fight Phantom Noises of Tinnitus

By Kate Murphy : NY Times Article : April 1, 2008

Modern life is loud. The jolting buzz of an alarm clock awakens the ears to a daily din of trucks idling, sirens blaring, televisions droning, computers pinging and phones ringing — not to mention refrigerators humming and air-conditioners thrumming. But for the 12 million Americans who suffer from severe tinnitus, the phantom tones inside their head are louder than anything else.

By Jane E. Brody : NY Times : Feb. 6, 2017

Dizziness is not a disease but rather a symptom that can result from a huge variety of underlying disorders or, in some cases, no disorder at all. Readily determining its cause and how best to treat it — or whether to let it resolve on its own — can depend on how well patients are able to describe exactly how they feel during a dizziness episode and the circumstances under which it usually occurs.

For example, I recently experienced a rather frightening attack of dizziness, accompanied by nausea, at a food and beverage tasting event where I ate much more than I usually do. Suddenly feeling that I might faint at any moment, I lay down on a concrete balcony for about 10 minutes until the disconcerting sensations passed, after which I felt completely normal.

The next morning I checked the internet for my symptom — dizziness after eating — and discovered the condition had a name: Postprandial hypotension, a sudden drop in blood pressure when too much blood is diverted to the digestive tract, leaving the brain relatively deprived. The condition most often affects older adults who may have an associated disorder like diabetes, hypertension or Parkinson’s disease that impedes the body’s ability to maintain a normal blood pressure. Fortunately, I am thus far spared any disorder linked to this symptom, but I’m now careful to avoid overeating lest it happen again.

“An essential problem is that almost every disease can cause dizziness,” say two medical experts who wrote a comprehensive new book, “Dizziness: Why You Feel Dizzy and What Will Help You Feel Better.” Although the vast majority of patients seen at dizziness clinics do not have a serious health problem, the authors, Dr. Gregory T. Whitman and Dr. Robert W. Baloh, emphasize that doctors must always “be on the alert for a serious disease presenting as ‘dizziness,’” like “stroke, transient ischemic attacks, multiple sclerosis and brain tumors.”

Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo can be caused by a blow to the head or be a result of aging. “Approximately one in five people in their 80s will develop B.P.P.V.,” the authors wrote. It can also affect younger people, particularly those who already have, or will develop, migraine headaches, they noted.Dr. Kevin A. Kerber, a neurotologist at the University of Michigan Health System, told me that dizziness is one of the most common symptoms that primary care and emergency department doctors see, as common as back pain and headache. He cited a nationally representative health survey conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 2008 in which 10 percent of adults said they had felt dizzy within the past year and had been referred to or seen by a health care specialist because of the symptom.

Typically, those reporting dizziness in the survey indicated they each had experienced three of the following different types: a spinning or vertigo sensation, including a rocking of yourself or your surroundings; a floating, spacey or tilting sensation; feeling lightheaded, without a sense of motion; feeling as if you are going to pass out or faint; blurring of your vision when you move your head; or feeling off-balance or unsteady.

As you can see, reporting a symptom simply as dizziness does not give a doctor much to go on. A major problem, Dr. Kerber said, is that the examining doctor has to decide on the type of dizziness and determine whether there may be a “particularly dangerous cause” like a heart attack or stroke based on “often unreliable” descriptions by patients.

People use the word dizziness when referring to lightheadedness, unsteadiness, motion intolerance, imbalance, floating or a tilting sensation. Vertigo, a subtype of dizziness, is an illusion of movement caused by uneven input to the inner ear’s vestibular system that provides a sense of balance and orientation in space. In 2011, an estimated 3.9 million people visited emergency departments with symptoms of dizziness or vertigo.

“Patients are generally nonspecific in describing their symptoms,” Dr. Kerber said. “They should spend time thinking about their symptoms before they see the doctor.” Factors to consider, he said, include “timing — does the dizziness occur episodically or is it constant? What seems to set it off — certain positions or particular foods? How long does the symptom last? And what happens over time — does it get worse, stay the same or get better?”

Note, too, whether the feelings get worse when you walk, stand up or move your head. Are the episodes accompanied by nausea, and do they occur so suddenly and severely that they force you to sit or lie down?

Family members or friends who pay attention to the affected individual’s complaints “can help contribute to a rapid and correct diagnosis,” according to the authors of the new book. Dr. Whitman is an otoneurology specialist at Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary, and Dr. Baloh is director of the neurotology clinic and testing laboratory at the medical center of the University of California, Los Angeles.

Two of the most common causes of dizziness are triggered by changes in position. One is called orthostatic hypotension — a reduced flow of blood to the brain that occurs when a person gets up from a sitting or lying position and goes away when the person lies down.

The second, called benign paroxysmal positional vertigo, or B.P.P.V., is not exactly benign to those affected, Dr. Kerber said. It is triggered by a change in head position, for example, when lying down, turning over in bed, or bending the head backward while sitting or standing (called “top shelf vertigo”), the authors of “Dizziness” wrote. The person may feel that the world is moving or spinning or that an object in the room is jumping up and down rhythmically.

Vertigo is one of the most disabling causes of dizziness. It arises when tiny calcium particles in the inner ear become dislodged from the balance organ and get stuck in the semicircular canal, where “they cause havoc,” Dr. Kerber explained. When the head is moved, the particles shift and set off a sensitive nerve wired to the eyes, making them jerk and causing dizziness. When the particles settle down, the eyes stop jerking and the dizziness goes away.

Vertigo can be a disabling condition that lasts for weeks, months or even years. Those affected are often unable to work, drive or walk around without falling.

However, B.P.P.V. usually responds to a treatment like the Epley maneuver, a sequence of movements that re-positions the head and gets the errant particles to go back to where they belong. The maneuver is often performed by a health professional, but patients can learn to do it on their own if the vertigo recurs.

Symptom: Dizziness.

Cause: Often Baffling.

By Richard Saltus : NY Times Article : September 6, 2005

On the Fourth of July, a 63-year-old man was taken by wheelchair into the emergency room of a suburban Virginia hospital, overwhelmed with dizziness and nausea and gripped by sweat-inducing anxiety.

"I felt dim and lightheaded, like I was just going to fade out," said John Farquhar, a semiretired consultant in Washington. "I said, 'I'm going to die.' "

His wife, Lou, a nurse, had driven him to the hospital, taking big curves gingerly because the motion of a sweeping turn "made me feel like I was pulling 30 G's like a fighter pilot," said Mr. Farquhar, who otherwise was healthy and fit.

The attacks had begun the previous day, out of the blue, while he was playing with the couple's dog, Sascha.

Lifting her high in the air, "I snapped my head back, and suddenly it seemed that my body was turning, and the room was spinning around," Mr. Farquhar recounted. "I felt profoundly dizzy and nauseated."

The episode passed, but the queasiness returned not long afterward, set off by the on-screen action on a DVD. When Mr. Farquhar got out of bed the next day, the world was spinning so violently that he crumpled to his knees, and he could barely make his way to the bathroom, where he vomited, leading to the trip to the E.R.

Dizziness is one of the most miserable of sensations, and it can be disabling.

The technical term for the false sensation that you and the world are spinning is vertigo. (In Alfred Hitchcock's film "Vertigo," the James Stewart character actually suffers from acrophobia, or fear of heights.)

There are many causes of vertigo, most of them temporary and treatable, but sometimes the condition signals a serious problem, like a tumor \nor a stroke. Dizziness and lightheadedness are among the most frequent complaints that cause people to seek medical help.

Although doctors often see patients with the symptom, its cause can be a challenge to determine, said Dr. Jonathan Olshaker, chief of the emergency department at Boston Medical Center, who has written a textbook chapter on vertigo.

"The staff has a concern that they're not going to be able to figure out what it is, or that the person is a difficult-to-treat patient," Dr. Olshaker said. In fact, a vast majority of patients have a specific, identifiable cause for their dizziness, he said.

Even when the cause is probably not serious, doctors generally are cautious, ordering a number of tests and sometimes consulting with neurologists to make sure the cause of the vertigo is not life-threatening.

Ruling out life-threatening causes, the doctors told Mr. Farquhar that he was most likely suffering from benign paroxysmal positional vertigo.

The problem accounts for perhaps 25 to 40 percent of patients seeking medical attention for dizziness. "Paroxysmal" refers to the episodic pattern of vertigo attacks, and "positional" means that the spinning sensations are brought on by certain movements.

Tilting the head back to look upward is a typical trigger. The disorder has been nicknamed "top-shelf vertigo," and hair salon customers sometimes experience it when leaning back for a shampoo, as do patients sitting in dental chairs.

The diagnosis and treatment of vertigo have markedly improved in the last two decades. The cause of most benign positional vertigo is now believed to be calcium debris that has dislodged from a part of the inner ear and strayed into one of the fluid-filled semicircular canals of the sensitive vestibular system.

The system is a cluster of structures that keeps the brain updated on the body's orientation and movement in space.

These microscopic flecks of calcium debris do not in themselves lead to problems, but sometimes in their meandering they brush against delicate, hairlike cells, sending misinformation to the brain.

When those signals conflict with more accurate signals from other nerves, the brain responds with disorientation and vertigo.

The three semicircular canals of the inner ear loop out - more or less at right angles, like three edges of a box meeting at the corner - from a chamber called the vestibule.

The slight fluid movements in these canals in response to head movements and gravity activate the hair-trigger cells that relay positional information to the brain.

Inside the vestibule, scores of tiny "stones" called otoliths are attached to \na membrane, and when the head turns in any direction, the slight force imparted to the otoliths is translated into nerve messages about motion and orientation. B.P.P.V., a common cause of dizziness caused by a malfunction of the inner ear's balance mechanism.

The problem accounts for perhaps 25 to 40 percent of patients seeking medical attention for dizziness. "Paroxysmal" refers to the episodic pattern of vertigo attacks, and "positional" means that the spinning sensations are brought on by certain movements.

The diagnosis and treatment of vertigo have markedly improved in the last two decades. The cause of most benign positional vertigo is now believed to be calcium debris that has dislodged from a part of the inner ear and strayed into one of the fluid-filled semicircular canals of the sensitive vestibular system.

The maneuvers involve moving the head into four different positions sequentially, taking advantage of gravity to roll the calcium flecks out of the sensitive part of the canal to a place where they cause less trouble.

In cases like Mr. Farquhar, the Epley maneuvers are repeated, the patient sits up, and the treatment is complete. For the next 48 hours, Mr. Farquhar was cautioned to avoid a variety of movements that could send the debris tumbling back into the canal.

Most doctors who do this say that 80 percent of patients have their symptoms alleviated in one set of treatments," Dr. Fitzgerald says.

The remaining 20 percent, he added, need repeated treatments, and the overall recurrence rate is 25 percent to 30 percent, though the episodes may not come back for months or years.

Within a few days, Mr. Farquhar was much improved and was able to walk several blocks and go into his office to work. Two months later, he continued to be free of nearly all his symptoms, except a brief lingering feeling of unease just after waking up in the morning.

For all but the most intractable cases, which occasionally require surgery, the simple and low-tech Epley maneuvers rank among the most effective and certainly the least costly of treatments for such a common and disabling source \nof misery.

"Vertigo is a horrible feeling," said Dr. Olshaker, the Boston emergency room chief. "The physician does need to have empathy for these patients. And in recent time, we're seeing more awareness of the condition and the Epley maneuvers, both in the E.R. and the primary care clinic."

A Stable Life, Despite Persistent Dizziness

By Jane E. Brody : NY Times Article : January 15, 2008

On the subway, children twirl themselves around the poles in the cars until they are so dizzy I’m ready to catch them. The young seem to delight in making the world spin out of control for a few moments, causing them to flop about like drunks. But when dizziness, vertigo or loss of balance is neither self-imposed nor short lived, it is anything but fun. It can throw one’s whole life out of kilter, literally and figuratively.This is what befell Cheryl Schiltz in 1997, when long treatment with the antibiotic gentamicin permanently damaged the vestibular apparatus in her inner ear. For three years, said Ms. Schiltz, of Madison, Wis., her world seemed to be made of Jell-O. Lacking a sense of balance, she wobbled with every step, and everything she looked at jiggled and tilted.Unable to work, Ms. Schiltz became increasingly isolated and struggled to perform the simplest household tasks.

Lisa Haven, executive director of the Vestibular Disorders Association, reports that “the risk of falling is two to three times greater in people with chronic imbalance or dizziness.” Nearly 9 percent of Americans 65 and older have balance problems, the prevalence of which is likely to increase as the 78 million baby boomers age.

Four Types of Dizziness :

The job of the vestibular system is to integrate sensory stimuli and movement for the brain and keep objects in visual focus as the body moves. When the head moves, signals are sent to the inner ear, an organ consisting of three semicircular canals surrounded by fluid. It in turn sends movement information to the vestibular nerve, which carries it to the brainstem and cerebellum, which control balance and posture and coordinate movement. Disruption of any part of the system can result in dizziness.

These are four types of dizziness, all of which are more common with increasing age:

- Faintness

- Loss of balance, feeling unsteady

- Vertigo

- Vague lightheadedness

What to Tell the Doctor:

About 40 percent of people experience at least one of these forms of dizziness at some time during their lives. When dizziness persists, medical care is essential, and so is the ability to provide a detailed description of the symptoms and what provokes them.

- What does the dizziness feel like — faintness, loss of balance, lightheadedness, a sensation that you or your surroundings are spinning or moving?

- When did the symptoms begin?

- How long do they last?

- What provokes or relieves them?

- What other symptoms like headache, ringing in the ears, impaired vision, difficulty walking, weakness or hearing loss accompany the dizziness?

- trying to reproduce the symptoms. For example, by rapidly standing and sitting, standing after lying down or lying on a tilt table while changes in blood pressure are measured.

- The doctor may test heart function with an electrocardiogram or an echocardiogram, an exercise stress test or a Holter monitor to detect abnormal rhythms.

- Vision tests may be performed, along with tests to evaluate balance and gait and

- C.T. or M.R.I. scans of the head, including noninvasive tests that check for narrowed or blocked arteries to the brain.

- If no physical explanation for dizziness is found, the patient may be checked for psychological disorders like depression, panic attacks or dissociation from the world.

For example, for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo, a simple head-turning maneuver that repositions crystals in the inner ear may bring lasting relief. If ministrokes are the cause, the treatment may involve anticlotting drugs or opening a blocked artery with a stent. If medication is the problem, adjusting the dose or changing the drug can relieve dizziness. If dizziness persists despite treatment, lifestyle adjustments can help like avoiding sudden movements, keeping often-used items within easy reach, standing up slowly and clenching hands and flexing feet before standing. Physical therapy can help, as can exercises that strengthen muscles and that combine eye, head and body movements.Ms. Schiltz, whose vestibular system was damaged a decade ago, said she was told that nothing could be done about it. Nothing, that is, until she became the first patient to be treated with a device called a BrainPort invented by the late Dr. Paul Bach-y-Rita, a neurobiologist and rehabilitation medicine specialist, and his colleagues at the University of Wisconsin. The device takes advantage of the acute sensitivity of the tongue and sends balance signals directly to the brain from the tongue, bypassing the ear’s vestibular apparatus. At first, she used it a few minutes at a time, but soon found longer use kept her in balance for hours, then days, then weeks and months. Eventually, all that was needed was 20 minutes twice a day to train her brain, and she now uses it just occasionally.She is among more than 100 study participants who have used the BrainPort, including patients with multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease and stroke. The device is available commercially in Canada and is awaiting approval by the Food and Drug Administration in the United States.Dr. Norman Doidge of the research faculty at the Columbia University Psychoanalytic Center and the University of Toronto describes Ms. Schiltz’s dramatic recovery in his new book about the plasticity of the brain, “The Brain That Changes Itself.” (Her case was also described in Science Times in November 2004.) With her sense of balance intact, Ms. Schiltz was able to return to school and on Dec. 20 received a degree in rehabilitation psychology.“I feel like a restored, even enhanced, person,” she said in an interview. “I’m living proof that the brain can be retrained. My goal now is to help people with acquired disabilities gain increased independence.”

New Views of Motion Sickness

Travel-Related Nausea Puzzles Scientists Amid Search for a Better Remedy; Ginger Root or a Nasal Spray?

Sumathi Reddy : WSJ : June 18, 2013

Researchers from the Navy, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration and academia are studying causes and potential treatments of motion sickness, hoping to formulate better products for situations that range from the extreme (space!) to the mundane (road trip to Grandma's, anyone?).

There's nothing quite like motion sickness to ruin summer travel, with symptoms including dizziness, headache, nausea and most unfortunately, vomiting. Some 25% to 40% of the population suffers from some degree of motion sickness, depending on the mode of transportation.

At Siena College, in Loudonville, N.Y., researchers have studied the effectiveness of ginger capsules, facial cooling and listening to music as a distraction for lessening symptoms and physiological responses to motion sickness.

NASA and the Navy are collaborating with pharmaceutical company Epiomed Therapeutics, of Irvine, Calif., to develop a nasal spray containing scopolamine, a drug currently used in a prescription-only patch for those prone to seasickness. Researchers say the drug's strong possible side effects, such as drowsiness and dry mouth, would be significantly reduced with a nasal spray.

Part of the difficulty with devising treatments is that experts don't know exactly what causes motion sickness. The prevailing belief is it is caused by a sensory mismatch between the visual and vestibular systems. The vestibular system, which is part of the inner ear, monitors movement and helps control balance.

In other words, our inner ear tells our brain that we are moving, but our eyes tell us we aren't, or vice versa. "When one of these is telling you you're in motion and the other one is telling you you're sitting, the brain gets confused with the mixed signals, and it causes this sense of sickness," says Abinash Virk, director of the travel and tropical medicine clinic at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

What remain unknown are the reasons why the mismatch causes some individuals to react adversely. One long-standing theory is that the reactions are triggered by the brain's false identification of a toxin in the body, with nausea and vomiting a protective response to get rid of it.

Another theory is that body sway, or the change in a person's movements over short time intervals, can explain a propensity to get motion sickness. In Tom Stoffregen's lab at the University of Minnesota, the kinesiology professor measures each subject's body sway over a short period. He has found that individuals who are more susceptible have a more-erratic sway during and even before they are exposed to any stimulation.

Dr. Stoffregen uses a force plate, a glorified bathroom scale with pressure sensors, to take measurements of body movement as often as 200 times a second. He studies people both in a lab simulator and on ships.

In a forthcoming study to be published in the online journal PLOS ONE, Dr. Stoffregen tested the body sway of 35 cruise passengers aboard a ship in the Caribbean before departure. Passengers then reported the intensity of their seasickness. He found a link: Those who reported getting more sea sickness had more body sway at the dock.

"There may be sort of a general classification that people who are susceptible to motion sickness have," Dr. Stoffregen said. "Maybe they just move differently in general."

Max Levine, an associate professor of psychology at Siena College, studies behavioral and alternative motion-sickness treatments. In a recent experiment on about 50 individuals, half received capsules with ginger root and the remainder got a placebo. Then the individuals were seated in a chamber and exposed to a rotating device called an optokinetic drum that induces motion sickness.

"The folks who got ginger beforehand ended up doing much better both in terms of the symptoms they developed and in terms of the physiological reaction that they had in the stomach," he said.

Recent behavioral experiments have found that cool compresses or gel packs placed on the forehead are somewhat effective at controlling physiological changes, such as abnormal rhythmic stomach activity that generally accompanies nausea, but didn't significantly reduce nausea. Listening to one's favorite music as a distraction showed improvements in symptoms including nausea, as well as in physiological changes, Dr. Levine said. Now, Dr. Levine is studying how deep breathing and relaxation may aid in motion sickness.

Doctors say a common misperception is that traveling on an empty stomach helps. Wrong. It's better to eat a light meal beforehand, especially one high in protein.

In a 2004 study in Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 18 individuals completed three trials. In one, they had a protein drink before exposure to a device that induces motion sickness. In a second trial, they had a carbohydrate drink, and the third time they had nothing. They fared best after the protein drink. Protein "really tends to get the stomach into that slow normal rhythmic activity more so than fats and carbohydrates," Dr. Levine said.

Children over age 2 seem more prone to motion sickness than adults. Some experts think children's extra-sharp senses may make them aware of even a slight mismatch. Adults in their golden years seem to experience motion sickness less often—perhaps because of habituation.

Women have a greater tendency than men to get motion sickness. Some experts believe this is because women also are more prone to getting migraines, and migraine sufferers have a higher rate of motion sickness. Or women may simply report motion sickness symptoms more often.

Doctors say prescription drugs and over-the-counter options like Dramamine are the best treatment option, though some can cause side effects. Such drugs work by suppressing the central nervous system's response to nausea-producing stimuli. They reduce symptoms for many people but aren't universally effective.

Some travelers rely on homeopathic remedies such as ginger or acupressure wrist bands. Sujana Chandrasekhar, director of New York Otology in New York City, said they aren't universally effective, but are "worth trying."

There are behavioral tips for preventing or minimizing symptoms. Cynthia Ryan knows them all. The 45-year-old Portland, Ore., resident has suffered from motion sickness since she was a child commuting to school along winding roads, her barf bag in hand. Now the executive director of the Vestibular Disorders Association, Ms. Ryan says individuals with vestibular disorders are prone to motion sickness.

Her rule of thumb is to always be the driver. "I almost never let somebody else drive," she said. "And if I do, I sit in the passenger seat." Even when sitting as the front passenger, Ms. Ryan says she does deep-breathing exercises and tries to focus on a fixed point on the road in front of her. "I can't participate in conversations," she said. "I can't read. Sometimes someone will pass me a smartphone and say, 'Can you read me the directions?' And I'll say, 'Not unless you want me to throw up in your car.' "

Watching television TV or reading in a car is a no-no. "Face forward in the vehicle to be as alert to what's happening outside the vehicle as the driver would be," Dr. Chandrasekhar said. "You want to try to match your eyes to what's going on and to what your inner ear is feeling." Experts say: Just close your eyes and sleep.

Living With a Sound You Can’t Turn Off

By Jane E. Brody : NY Times : December 3, 2012

Shortly after my 70th birthday, a high-pitched hum began in my left ear. I noticed it only during quiet times but soon realized that it never went away.

An ear, nose and throat specialist (otolaryngologist) examined my ears and took a thorough medical history that included questions about noise exposure and drugs I take. An audiologist checked my hearing.

Diagnosis: tinnitus, with a mild hearing loss in the upper range that closely matched the pitch of the hum.

Although the hum was not particularly disturbing, I asked what might be done if it should get loud enough to interfere with my life and ability to hear speech clearly (about 85 percent of tinnitus cases are accompanied by hearing loss). The answer was that I could be fitted with a hearing aid.

But since my tinnitus is still mild, no mention was made of anything that might relieve the constant noise in my head.

Tinnitus is a chronic noise of varying intensity, loudness and pitch that has no external source. Rather, it seems to come from within a person's head. It is most apparent to the sufferer when all is quiet and may not be noticed when the person is otherwise distracted - while participating in physical activity, for example, or listening to music.

There is currently no cure for tinnitus, a potentially life-disrupting condition that affects about 10 to 20 percent of people, mostly those over age 65, but also many veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Among possible causes are head and neck injuries, drugs that damage the ear, blood vessel disease, autoimmune disorders, ear conditions and disorders of the temporomandibular joint.

Until recently, no treatment had been shown to have lasting effectiveness in controlled clinical trials, despite a host of remedies variously endorsed by hearing specialists and commercial interests.

In addition to a hearing aid, the most commonly prescribed remedy is a so-called masking device, a white-noise machine that introduces natural or artificial sound into the sufferer's ears in an attempt to suppress the perceived ringing. But eventually the noise of the masker can become as disruptive as the tinnitus.

"When patients respond poorly to the masking device, they are often told they haven't used it long or consistently enough," said Rilana F. F. Cima, a psychologist and researcher in the Netherlands.

Fear and Anxiety

Dr. Cima said in an interview that, like me, most people with tinnitus function fairly well. But for about 3 percent of people with the condition, it is extremely disabling, causing intense distress, fear and anxiety, and leaving them unable to function.

"Patients say the sound is driving them crazy," Dr. Cima said. "Their negative reaction to not wanting to hear it creates daily life impairment." She said patients would do almost anything to avoid hearing the sound in their heads and the feelings of fear and anxiety that result.

Recently Dr. Cima's team demonstrated the effectiveness of a multidisciplinary, psychology-based approach to this problem. The technique, published last spring in The Lancet, does not make the ringing go away, but it does show that now there is real hope for relief for people whose tinnitus impairs their ability to work, sleep and enjoy life.

In an accompanying editorial, Dr. Berthold Langguth of the University of Regensburg in Germany, an international authority on tinnitus, said the team's findings "overcome the idea that nothing can be done to treat tinnitus" and provide "a clear statement against therapeutic nihilism."

James Henry, a specialist in auditory rehabilitation at the Veterans Administration Medical Center in Portland, Ore., where many veterans with traumatic brain injuries are treated for tinnitus, said that Dr. Cima had done "probably the best study to date, a good job that is advancing the field."

An Improved Approach

The three-month treatment developed and carefully tested by the Dutch team is based on cognitive behavioral therapy and relies on principles of exposure therapy long proven effective to treat phobias. While the use of cognitive behavioral therapy for tinnitus is not new, the team's demonstration of a scientifically validated, comprehensive approach to the problem offers a therapeutic blueprint that others can use.

Unlike the use of a tinnitus masker, the treatment is simple, relatively brief and does not require patients to purchase or use devices to gain relief. If necessary, patients who "relapse" can return for a brief therapeutic brush-up.

Dr. Cima's team enrolled 492 patients with varying degrees of tinnitus and randomly assigned them to receive either usual care or "specialized" care. Usual care, in the Netherlands as well as in the United States, involves a medical exam and hearing test, typically followed by a prescription for a hearing aid and/or masking device.

Patients may also be given antidepressants, anti-anxiety drugs, sleep aids or other medication to relieve emotional distress and other disabling symptoms.

The Dutch treatment relies solely on psychological techniques. Following an education session about tinnitus and lessons in deep relaxation, patients are gradually exposed to an external source of the very ringing they hear in their heads. After 10 or 12 sessions, they become habituated to it and no longer find it threatening.

It is not the noise itself but "patients' extremely negative reaction to it that creates daily life impairment," Dr. Cima explained. "Patients are continuously stressed and fearful of it. It becomes a sign of a danger from which they must escape."

She likened the approach to helping people overcome their fear of spiders by inducing deep relaxation and gradually introducing them to increasingly realistic objects of their fear.

"They may never learn to love spiders, but they can live with them more comfortably," Dr. Cima said.

Dr. Henry of the veterans medical center, who has been involved in tinnitus research for a quarter century, said his team uses a similar approach with five treatment sessions, which "takes care of about 95 percent of cases," he said.

"Lots of veterans get tinnitus in association with traumatic brain injuries, but the tinnitus is often permanent even after these other injuries are resolved," Dr. Henry said. "We teach them skills that enable them to manage their tinnitus. They learn to reframe the problem in a more positive way. It's not a cure - nobody has a cure - but we're able to help most veterans and enable them to live a normal life."

A cure may emerge from findings of changes in the brains of tinnitus patients that are being revealed through sophisticated imaging techniques.

New Therapies Fight Phantom Noises of Tinnitus

By Kate Murphy : NY Times Article : April 1, 2008

Modern life is loud. The jolting buzz of an alarm clock awakens the ears to a daily din of trucks idling, sirens blaring, televisions droning, computers pinging and phones ringing — not to mention refrigerators humming and air-conditioners thrumming. But for the 12 million Americans who suffer from severe tinnitus, the phantom tones inside their head are louder than anything else.

Often caused by prolonged or sudden exposure to loud noises, tinnitus (pronounced tin-NIGHT-us or TIN-nit-us) is becoming an increasingly common complaint, particularly among soldiers returning from combat, users of portable music players, and aging baby boomers reared on rock ’n’ roll. (Other causes include stress, some kinds of chemotherapy, head and neck trauma, sinus infections, and multiple sclerosis.)

Although there is no cure, researchers say they have never had a better understanding of the cascade of physiological and psychological mechanisms responsible for tinnitus. As a result, new treatments under investigation — some of them already on the market — show promise in helping patients manage the ringing, pinging and hissing that otherwise drives them to distraction.

The most promising therapies, experts say, are based on discoveries made in the last five years about the brain activity of people with tinnitus. With brain-scanning equipment like functional magnetic resonance imaging, researchers in the United States and Europe have independently discovered that the brain areas responsible for interpreting sound and producing fearful emotions are exceptionally active in people who complain of tinnitus.

“We’ve discovered that tinnitus is not so much ringing in the ears as ringing in the brain,” said Thomas J. Brozoski, a tinnitus researcher at Southern Illinois University School of Medicine in Springfield.

Indeed, tinnitus can be intense in people with hearing loss and even those whose auditory nerves have been completely severed. In the absence of normal auditory stimulation, the brain is like a driver trying to tune in to a radio station that is out of range. It turns up the volume trying but gets only annoying static. Richard Salvi, director of the Center for Hearing and Deafness at the State University of New York at Buffalo, said the static could be “neural noise” — the sound of nerves firing. Or, he said, it could be a leftover sound memory.

Adam Edwards, a 34-year-old co-owner of a wheel repair shop in Dallas, said he developed tinnitus four years ago after target shooting with a pistol. “I had all the risk factors,” he said. “I grew up hunting, I played drums in a band, I went to loud concerts, I have a loud work environment — everything but living next to a missile launch site.” His tinnitus, which he described as a “computer beeping” sound, was so intense and persistent that he needed sedatives to sleep at night.

Mr. Edwards says he has gotten relief from a device developed by an Australian audiologist, which became widely available in the United States last year. Manufactured by Neuromonics Inc. of Bethlehem, Pa., it looks like an MP3 player and delivers sound spanning the full auditory spectrum, digitally embedded in soothing music.

Similar to white noise, the broadband sound, tailored to each patient’s hearing ability, masks the tinnitus. (The music is intended to ease the anxiety that often accompanies the disorder.) Patients wear the $5,000 device, which is usually not covered by health insurance, for a minimum of two hours a day for six months. Since completing the treatment regimen last year, Mr. Edwards said his tinnitus had “become sort of like Muzak at a department store — you hear it if you think about it, but otherwise you don’t really notice.”

A small, company-financed study in the journal Ear & Hearing in April 2007 indicated that the Neuromonics method was 90 percent successful at reducing tinnitus. A larger study is under way to determine its long-term effectiveness.

Anne Howell, an audiologist at the Callier Center for Communication Disorders at the University of Texas at Dallas, said the Neuromonics device was a big improvement over older sound therapies that required wearing something that looked like a hearing aid all the time and took 18 to 24 months.

“The length of time was discouraging for many patients,” she said. “And a lot of them told me that wearing something that looks like a hearing aid would cause a problem in their professional life.”

Other treatments showing promise include surgically implanted electrodes and noninvasive magnetic stimulation, both intended to disrupt and possibly reset the faulty brain signals responsible for tinnitus. Using functional M.R.I. to guide them, neurosurgeons in Belgium have performed the implant procedure on several patients in the last year and say it has suppressed tinnitus entirely.

But the treatment is controversial. “It’s a radical option and not proven yet,” said Jennifer R. Melcher, an assistant professor of otology and laryngology at Harvard Medical School.

The magnetic therapy, similar to treatments used for depression and chronic pain, involves holding a magnet in the shape of a figure eight over the skull. Clinicians use functional M.R.I. to aim the magnetic pulses so they reach regions of the brain responsible for interpreting sound. Patients receive a pulse every second for about 20 minutes. “It works for some people but not for others,” said Anthony Cacace, professor of communication science and nerve disorders at Wayne State University in Detroit. Since tinnitus has so many causes, Dr. Cacace said, the challenge now is to find out which “subsets of patients benefit from this treatment.”

Researchers in Brazil have published a study indicating that a treatment called cranial-sacral trigger point therapy can relieve tinnitus in some head and neck trauma cases by releasing muscles that constrict hearing and neural pathways.

And drugs intended to treat alcoholism, epilepsy, Alzheimer’s and depression that alter levels of various neurotransmitters in the brain like serotonin, dopamine and gamma-aminobutyric acid have quieted tinnitus in some published animal and human studies.

“We’ve never been so hopeful,” said Dr. Salvi, of SUNY Buffalo, “of finding treatments for a disorder that haunts people and follows them everywhere they go.”

That Buzzing Sound : The mystery of tinnitus.

by Jerome Groopman, MD

The New Yorker : February 9, 2009

Tinnitus is one of the most common clinical conditions in the United States.

I noticed the sound one evening about a year ago. At first, I thought an alarm had been set off. Then I realized that the noise—a high-pitched drone—was mainly in my right ear. It has been with me ever since. The tone varies, from a soft whoosh like a shower to a piercing screech resembling a dental drill. When I am engaged in work at the hospital or in the laboratory, it seems distant. But in idle moments it gets louder and more annoying, once even jarring me from a dream.

Tinnitus—the false perception of sound in the absence of an acoustic stimulus, a phantom noise—is one of the most common clinical syndromes in the United States, affecting twelve per cent of men and almost fourteen per cent of women who are sixty-five and older. It only rarely afflicts the young, with one significant exception: those serving in the armed forces. Tinnitus affects nearly half the soldiers exposed to blasts in Iraq and Afghanistan.