- RETIREMENT ANNOUNCEMENT

- HOME PAGE

- "MYCHART" the new patient portal

- BELMONT MEDICAL ASSOCIATES

- MOUNT AUBURN HOSPITAL

- EMERGENCIES

- PRACTICE PHILOSOPHY

- MY RESUME

- TELEMEDICINE CONSULTATION

- CONTACT ME

- LAB RESULTS

- ePRESCRIPTIONS

- eREFERRALS

- RECORD RELEASE

- MEDICAL SCRIBE

- PHYSICIAN ASSISTANT (PA)

- Medicare Annual Wellness Visit

- Case management/Social work

- Quality Care Measures

- Emergency closing notice

- FEEDBACK

- Talking to your doctor

- Choosing..... and losing a doctor

- INDEX A - Z

- ALLERGIC REACTIONS

- Alternative Medicine

- Alzheimer's Disease

- Bladder Problems

- Blood disorders

- Cancer Concerns

- GENETIC TESTING FOR HEREDITARY CANCER

- Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

- Controversial Concerns

- CPR : Learn and save a life

- CRP : Inflammatory marker

- Diabetes Management

- Dizziness, Vertigo,Tinnitus and Hearing Loss

- EXERCISE

- FEMALE HEALTH

-

GASTROINTESTINAL topics

- Appendicitis

- BRAT diet

- Celiac Disease or Sprue

- Crohn's Disease

- Gastroenterologists for Colon Cancer Screening

- Colonoscopy PREP

- Constipation

- Gluten sensitivity, but not celiac disease

- Heartburn and GERD

- Hemorrhoids and Anal fissure

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- NASH : Non Alcoholic Steato Hepatitis

- FEET PROBLEMS

- HEART RELATED topics

-

INFECTIOUS DISEASES

- Antibiotic Resistance

- Cat bites >

- Clostridia difficile infection - the "antibiotic associated germ"

- CORONA VIRUS

- Dengue Fever and Chikungunya Fever

- Food borne illnesses

- Shingles Vaccine

- Hepatitis B

- Hepatitis C

- Herpes

- Influenza

- Helicobacter pylori - the "ulcer germ"

- HIV Screening

- Lyme and other tick borne diseases

- Measles

- Meningitis

- MRSA (Staph infection)

- Norovirus

- Sexually Transmitted Diseases

- Shingles (Herpes Zoster)

- Sinusitis

- West Nile Virus

- Whooping Cough (Pertussis)

- Zika virus and pregnancy

- INSURANCE related topics

- KIDNEY STONES

- LEG CRAMPS

- LIBRARY for patients

- LIFE DECISIONS

- MALE HEALTH

- Medication/Drug side effects

- MEDICAL MARIJUANA

- MENTAL HEALTH

- Miscellaneous Articles

-

NUTRITION - EXERCISE - WEIGHT

- Cholesterol : New guidelines for treatment

- Advice to lower your cholesterol

- Cholesterol : Control

- Cholesterol : Raising your HDL Level

- Exercise

- Food : Making Smart Choices

- Food : Making Poor Choices

- Food : Grape Fruit and Drug Interaction

- Food : Vitamins, Minerals and Supplements

- Omega 3 fatty acids

- Vitamin B12 deficiency

- Vitamin D

- Weight Loss

- ORTHOPEDICS

- PAIN

- PATIENTS' RIGHTS

- SKIN

- SLEEP

- SMOKING

- STROKE

- THYROID

- SUBSTANCE ABUSE

- Travel and Vaccination

- TREMOR

- Warfarin Anticoagulation

- OTHER STUFF FOLLOWS

- Fact or Opinion?

- Hippocratic Oath

- FREE ADVICE.......for what its worth!

- LAUGHTER.....is the best medicine

- Physicians Pet Peeves

- PHOTO ALBUM - its not all work!

- Cape Town, South Africa

- Tribute page

- The 100 Club

- Free Wi-Fi

Shingles Vaccine

A Shot to Keep the Shingles at Bay

By Jane E. Brody : NY Times Article : October 2, 2007

Maybe you haven’t heard anything about the shingles vaccine. Or maybe you have, but decided against getting it for any of a number of reasons like these:

“My shingles case began with the periodic sensation that bugs were crawling in my hair. Three weeks later, I developed a headache that was one-sided but unlike a migraine. The pain was so bad I couldn’t go to work. That evening, I discovered a raised and very tender ridge on my scalp.

“Unable to sleep and in terrible pain, I went to the local emergency room. The doctor there gave me an intravenous painkiller, tested me for meningitis or encephalitis, and concluded that I had a migraine and infected hair follicle.

“The terrible head pain grew, as did the sensitivity of the rash, and at 3 a.m. the next day, my husband drove me to a major hospital. The doctor cursorily looked at the blistering rash and treated me for a migraine. He had no explanation for the rash.

“After another horrible night and day of pain and a growing rash, my husband drove me to Urgent Care, where a nurse immediately suspected shingles, and the doctor concluded ‘shingles’ in 30 seconds. I got acyclovir for the virus and Vicodin for pain. I slept a lot, and my eye swelled. When the blisters scabbed over, I returned to work, but I was so tired and my eye was so sensitive to light that I had to cut short my workdays.”

Mrs. ClappSmith, an urban planner from St. Paul, said that after her experience she encouraged her mother, who is 71, to get the shingles vaccine. But that decision is not always simple.

One Virus, Two Diseases

Shingles, or herpes zoster, can afflict anyone who has had chickenpox. Both are caused by the varicella-zoster virus. It is not known whether shingles can develop in people who received the chickenpox vaccine, which contains a live attenuated form of the virus.

This virus never leaves the body. It lies dormant for years in nerve roots near the spinal cord and can be reactivated as a shingles infection at any time, especially in people whose immune system is weakened by advanced age, extreme stress, a disease like cancer or AIDS or medications like chemotherapy, steroids and drugs used to prevent organ rejection.

Sometimes, a physical stress like cold or sunburn can bring on an attack.

Reactivated, the virus migrates down the nerve until it reaches the skin, where it causes vague symptoms of irritation, pain, numbness, itching or tingling, followed in two or three days by a painful, blistering rash on one side of the face, head or body. Untreated, the rash lasts two to four weeks.

The pain can be severe and may be accompanied by headache, fever, chills and an upset stomach. In rare cases, it can lead to pneumonia, hearing loss, blindness, encephalitis and, rarer still, death.

After the rash clears, about one patient in five develops post-herpetic neuralgia, or PHN, a debilitating pain that does not always respond to treatment and can be devastating to ordinary life for months or even years.

Treatment with the antiviral drug acyclovir is best administered as early as possible, preferably within 72 hours of the first sign of a rash, to shorten the course of the disease and prevent the severe symptoms that Mrs. ClappSmith experienced. Antiviral drugs, if taken early, can reduce the severity of subsequent post-herpetic neuralgia, but starting antivirals after PHN develops is of no help.

About one million cases of shingles a year occur in the United States, and the risk of it and of PHN increases with age. Half of 85-year-olds will have had shingles and, as people age, shingles-associated nerve pain increases in frequency and severity.

Debilitating nerve pain occurs in nearly a third of people with shingles who are 60 or older, and about 12 percent of older people who have shingles have pain that lasts three months or longer. The pain of PHN, which is difficult to treat, has been described as burning, throbbing, aching, stabbing or shooting. Even clothing touching the skin or a cool breeze can cause excruciating pain.

The Vaccine: Pro and Con

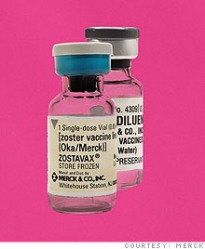

The shingles vaccine, Zostavax by Merck, was licensed in May 2006 after a study of more than 38,500 men and women 60 and older showed that it prevented about half of cases of shingles and reduced the risk of PHN by two-thirds.

“Among vaccine recipients who did get shingles, the episodes generally were far milder than they otherwise would have been,” said Dr. Stephen E. Straus, an infectious disease specialist at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

The vaccine, given in a single dose by injection, contains the same attenuated virus as the chickenpox vaccine, but is 14 times as potent. The side effects have been minimal, usually redness, soreness, swelling or itching at the injection site and, rarely, headaches. Based on the study, the researchers estimated that the vaccine could prevent 250,000 cases of shingles a year and significantly reduce its severity and complications in another 250,000 people. The vaccine is most effective in people 60 to 69, and less so with advancing age.

The vaccine is approved for use in people 60 and older who have had chickenpox. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommended that it be given to people who have had shingles, though the chances of another attack are low. Some insurers will not pay to immunize patients who have had shingles.

For Medicare beneficiaries, the cost is covered only for those with Medicare Part D, the drug benefit, and only if the vaccine is in the formulary of their chosen plan.

Coverage for Zostavax by independent insurers is spotty, though appeals are possible. Many older people who would benefit most from it are unable or unwilling to pay for it. The manufacturer’s price is about $150. The patients’ cost is often $300, although some public health services offer it for about $165. Doctors have to buy the vaccine for their patients.

Because people in their 50s account for one in every seven cases of shingles, some physicians administer the vaccine “off label” to those younger than 60, even though its safety and effectiveness in younger people are not known. Also unknown is whether the vaccine is safe to administer to people whose immune systems are already weakened.

Follow-up studies are under way to determine how long the vaccine remains effective. If immunity wanes, a booster shot may be necessary.

Until the unknowns are resolved, the vaccine is not recommended for those with immune systems weakened by disease or drug treatment, women who are pregnant or might be pregnant and people with active untreated tuberculosis. Nor should the vaccine be given to anyone who has had a life-threatening allergic reaction to gelatin or the antibiotic neomycin.

Federal health officials urge vaccine recipients to help them monitor reactions by reporting unusual symptoms like high fever or behavior changes or allergic reactions like difficulty breathing, rapid heart beat, dizziness, hives or wheezing to their doctors and asking the doctors to file a Vaccine Adverse Event Report. Patients can file reports themselves through www.vaers.hhs.gov or by calling (800) 822-7967.

By Jane E. Brody : NY Times Article : October 2, 2007

Maybe you haven’t heard anything about the shingles vaccine. Or maybe you have, but decided against getting it for any of a number of reasons like these:

- It is approved for people 60 and older, and you are 45.

- Your insurance does not cover it, and it costs $165 to $300.

- It protects just half of those vaccinated, and you would just as soon take your chances.

- No one yet knows how long the benefits will last.

- No one yet knows about delayed side effects.

- You do not know anything about shingles, so how common or bad can it be?

“My shingles case began with the periodic sensation that bugs were crawling in my hair. Three weeks later, I developed a headache that was one-sided but unlike a migraine. The pain was so bad I couldn’t go to work. That evening, I discovered a raised and very tender ridge on my scalp.

“Unable to sleep and in terrible pain, I went to the local emergency room. The doctor there gave me an intravenous painkiller, tested me for meningitis or encephalitis, and concluded that I had a migraine and infected hair follicle.

“The terrible head pain grew, as did the sensitivity of the rash, and at 3 a.m. the next day, my husband drove me to a major hospital. The doctor cursorily looked at the blistering rash and treated me for a migraine. He had no explanation for the rash.

“After another horrible night and day of pain and a growing rash, my husband drove me to Urgent Care, where a nurse immediately suspected shingles, and the doctor concluded ‘shingles’ in 30 seconds. I got acyclovir for the virus and Vicodin for pain. I slept a lot, and my eye swelled. When the blisters scabbed over, I returned to work, but I was so tired and my eye was so sensitive to light that I had to cut short my workdays.”

Mrs. ClappSmith, an urban planner from St. Paul, said that after her experience she encouraged her mother, who is 71, to get the shingles vaccine. But that decision is not always simple.

One Virus, Two Diseases

Shingles, or herpes zoster, can afflict anyone who has had chickenpox. Both are caused by the varicella-zoster virus. It is not known whether shingles can develop in people who received the chickenpox vaccine, which contains a live attenuated form of the virus.

This virus never leaves the body. It lies dormant for years in nerve roots near the spinal cord and can be reactivated as a shingles infection at any time, especially in people whose immune system is weakened by advanced age, extreme stress, a disease like cancer or AIDS or medications like chemotherapy, steroids and drugs used to prevent organ rejection.

Sometimes, a physical stress like cold or sunburn can bring on an attack.

Reactivated, the virus migrates down the nerve until it reaches the skin, where it causes vague symptoms of irritation, pain, numbness, itching or tingling, followed in two or three days by a painful, blistering rash on one side of the face, head or body. Untreated, the rash lasts two to four weeks.

The pain can be severe and may be accompanied by headache, fever, chills and an upset stomach. In rare cases, it can lead to pneumonia, hearing loss, blindness, encephalitis and, rarer still, death.

After the rash clears, about one patient in five develops post-herpetic neuralgia, or PHN, a debilitating pain that does not always respond to treatment and can be devastating to ordinary life for months or even years.

Treatment with the antiviral drug acyclovir is best administered as early as possible, preferably within 72 hours of the first sign of a rash, to shorten the course of the disease and prevent the severe symptoms that Mrs. ClappSmith experienced. Antiviral drugs, if taken early, can reduce the severity of subsequent post-herpetic neuralgia, but starting antivirals after PHN develops is of no help.

About one million cases of shingles a year occur in the United States, and the risk of it and of PHN increases with age. Half of 85-year-olds will have had shingles and, as people age, shingles-associated nerve pain increases in frequency and severity.

Debilitating nerve pain occurs in nearly a third of people with shingles who are 60 or older, and about 12 percent of older people who have shingles have pain that lasts three months or longer. The pain of PHN, which is difficult to treat, has been described as burning, throbbing, aching, stabbing or shooting. Even clothing touching the skin or a cool breeze can cause excruciating pain.

The Vaccine: Pro and Con

The shingles vaccine, Zostavax by Merck, was licensed in May 2006 after a study of more than 38,500 men and women 60 and older showed that it prevented about half of cases of shingles and reduced the risk of PHN by two-thirds.

“Among vaccine recipients who did get shingles, the episodes generally were far milder than they otherwise would have been,” said Dr. Stephen E. Straus, an infectious disease specialist at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

The vaccine, given in a single dose by injection, contains the same attenuated virus as the chickenpox vaccine, but is 14 times as potent. The side effects have been minimal, usually redness, soreness, swelling or itching at the injection site and, rarely, headaches. Based on the study, the researchers estimated that the vaccine could prevent 250,000 cases of shingles a year and significantly reduce its severity and complications in another 250,000 people. The vaccine is most effective in people 60 to 69, and less so with advancing age.

The vaccine is approved for use in people 60 and older who have had chickenpox. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommended that it be given to people who have had shingles, though the chances of another attack are low. Some insurers will not pay to immunize patients who have had shingles.

For Medicare beneficiaries, the cost is covered only for those with Medicare Part D, the drug benefit, and only if the vaccine is in the formulary of their chosen plan.

Coverage for Zostavax by independent insurers is spotty, though appeals are possible. Many older people who would benefit most from it are unable or unwilling to pay for it. The manufacturer’s price is about $150. The patients’ cost is often $300, although some public health services offer it for about $165. Doctors have to buy the vaccine for their patients.

Because people in their 50s account for one in every seven cases of shingles, some physicians administer the vaccine “off label” to those younger than 60, even though its safety and effectiveness in younger people are not known. Also unknown is whether the vaccine is safe to administer to people whose immune systems are already weakened.

Follow-up studies are under way to determine how long the vaccine remains effective. If immunity wanes, a booster shot may be necessary.

Until the unknowns are resolved, the vaccine is not recommended for those with immune systems weakened by disease or drug treatment, women who are pregnant or might be pregnant and people with active untreated tuberculosis. Nor should the vaccine be given to anyone who has had a life-threatening allergic reaction to gelatin or the antibiotic neomycin.

Federal health officials urge vaccine recipients to help them monitor reactions by reporting unusual symptoms like high fever or behavior changes or allergic reactions like difficulty breathing, rapid heart beat, dizziness, hives or wheezing to their doctors and asking the doctors to file a Vaccine Adverse Event Report. Patients can file reports themselves through www.vaers.hhs.gov or by calling (800) 822-7967.

Why Patients Aren’t Getting the Shingles Vaccine

By Pauline W. Chen, MD : NY Times Article : June 10, 2010

Four years ago at age 78, R., a retired professional known as much for her small-town Minnesotan resilience as her commitment to public service, developed a fleeting rash over her left chest. The rash, which turned out to be shingles, or herpes zoster, was hardly noticeable.

But the complications were unforgettable.

For close to a year afterward, R. wrestled with the searing and relentless pain in the area where the rash had been. “It was ghastly, the worst possible pain anyone could have,” R. said recently, recalling the sleepless nights and fruitless search for relief. “I’ve had babies and that hurts a lot, but at least it goes away. This pain never let up. I felt like I was losing my mind for just a few minutes of peace.”

Shingles and its painful complication, called postherpetic neuralgia, result from reactivation of the chicken pox virus, which remains in the body after a childhood bout and is usually dormant in the adult. Up to a third of all adults who have had chicken pox will eventually develop one or both of these conditions, becoming debilitated for anywhere from a week to several years. That percentage translates into about one million Americans affected each year, with older adults, whose immune systems are less robust, being most vulnerable. Once the rash and its painful sequel appear, treatment options are limited at best and carry their own set of complications.

While the search for relief costs Americans over $500 million each year, the worst news until recently has been that shingles and its painful complication could happen to any one of us. There were no preventive measures available.

But in 2006, the Food and Drug Administration approved a new vaccine against shingles. Clinical trials on the vaccine revealed that it could, with relatively few side effects, reduce the risk of developing shingles by more than half and the risk of post-herpetic neuralgia by over two-thirds. In 2008, a national panel of experts on immunizations at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention went on to recommend the vaccine to all adults age 60 and older.

At the time, the shingles vaccine seemed to embody the best of medicine, both old school and new. Its advent was contemporary medicine’s elegant response to a once intractable, age-old problem. It didn’t necessarily put an end to the spread of disease, in this case chicken pox; but it dramatically reduced the burden of illness for the affected individual. And, most notably, its utter simplicity was a metaphoric shot-in-the-arm for old-fashioned doctoring values. Among the increasingly complex and convoluted suggestions for health care reform that were brewing at that moment, here was a powerful intervention that relied on only three things: a needle, a syringe and a patient-doctor relationship rooted in promoting wellness.

Not.

In the two years since the vaccine became available, fewer than 10 percent of all eligible patients have received it. Despite the best intentions of patients and doctors (and no shortage of needles and syringes), the shingles vaccine has failed to take hold, in large part because of the most modern of obstacles. What should have been a widely successful and simple wellness intervention between doctors and their patients became a 21st century Rube Goldberg-esque nightmare.

Last month in The Annals of Internal Medicine, researchers from the University of Colorado in Denver and the C.D.C. surveyed almost 600 primary care physicians and found that fewer than half strongly recommended the shingles vaccine. Doctors were not worried about safety — a report in the same issue of the journal confirmed that the vaccine has few side effects; rather, they were concerned about patient cost.

Although only one dose is required, the vaccination costs $160 to $195 per dose, 10 times more than other commonly prescribed adult vaccines; and insurance carriers vary in the amount they will cover. Thus, while the overwhelming majority of doctors in the study did not hesitate to strongly recommend immunizations against influenza and pneumonia, they could not do the same with the shingles vaccine.

“It’s just a shot, not a pap smear or a colonoscopy,” said Dr. Laura P. Hurley, lead author and assistant professor of medicine at the University of Colorado in Denver. “But the fact is that it is an expensive burden for all patients, even those with private insurance and Medicare because it is not always fully reimbursed.”

Moreover, many private insurers require patients to pay out of pocket first and apply for reimbursement afterward. And because the shingles vaccine is the only vaccine more commonly given to seniors that has been treated as a prescription drug, eligible Medicare patients must also first pay out of pocket then submit the necessary paperwork in order to receive the vaccine in their doctor’s office. It’s a complicated reimbursement process that stands in stark contrast to the automatic, seamless and fully covered one that Medicare has for flu and pneumonia vaccines.

Despite this payment maze, some physicians have tried to stock and administer the vaccine in their offices; many, however, eventually stop because they can no longer afford to provide the immunizations. “If you have one out of 10 people who doesn’t pay for the vaccine, your office loses money,” said Dr. Allan Crimm, the managing partner of Ninth Street Internal Medicine, a primary care practice in Philadelphia. Over time, Dr. Crimm’s practice lost thousands of dollars on the shingles vaccine. “It’s indicative of how there are perverse incentives that make it difficult to accomplish what everybody agrees should happen.”

Even bypassing direct reimbursement is fraught with complications for doctors and patients. A third of the physicians surveyed in the University of Colorado study resorted to “brown bagging,” a term more frequently used to describe insurers who have patients carry chemotherapy drugs from a cheaper supplier to their oncologists’ offices. In the case of the shingles vaccine, the study doctors began writing prescriptions for patients to pick up the vaccine at the pharmacy and then return to have it administered in their offices. However, the shingles vaccine must be frozen until a few minutes before administration, and a transit time greater than 30 minutes between office and pharmacy can diminish the vaccine’s effectiveness.

Dr. Crimm and the physicians in his office finally resorted to what another third of the physicians in the study did: they gave patients prescriptions to have the vaccine administered at pharmacies that offered immunization clinics. But when faced with the added hassles of taking additional time off from work and making a separate trip to the pharmacy, not all patients followed through. “Probably about 60 percent of our patients finally did get the vaccine at the pharmacy,” Dr. Crimm estimated. “This is as opposed to 98 percent of our patients getting the pneumonia and influenza vaccines, immunizations where they just have to go down the hall because we stock it, roll up their sleeves then walk out the door.”

With all of these barriers, it comes as no surprise that in the end only 2 percent to 7 percent of patients are immunized against shingles. “There’s just so much that primary care practices must take care of with chronic diseases like obesity and diabetes and heart disease,” Dr. Hurley noted. “If a treatment isn’t easy to administer, then sometimes it just falls to the bottom of the list of things for people to do.”

“Shingles vaccination has become a disparity issue,” Dr. Hurley added. “It’s great that this vaccine was developed and could potentially prevent a very severe disease. But we have to have a reimbursement process that coincides with these interventions. Just making these vaccines doesn’t mean that they will have a public health impact.”

By Pauline W. Chen, MD : NY Times Article : June 10, 2010

Four years ago at age 78, R., a retired professional known as much for her small-town Minnesotan resilience as her commitment to public service, developed a fleeting rash over her left chest. The rash, which turned out to be shingles, or herpes zoster, was hardly noticeable.

But the complications were unforgettable.

For close to a year afterward, R. wrestled with the searing and relentless pain in the area where the rash had been. “It was ghastly, the worst possible pain anyone could have,” R. said recently, recalling the sleepless nights and fruitless search for relief. “I’ve had babies and that hurts a lot, but at least it goes away. This pain never let up. I felt like I was losing my mind for just a few minutes of peace.”

Shingles and its painful complication, called postherpetic neuralgia, result from reactivation of the chicken pox virus, which remains in the body after a childhood bout and is usually dormant in the adult. Up to a third of all adults who have had chicken pox will eventually develop one or both of these conditions, becoming debilitated for anywhere from a week to several years. That percentage translates into about one million Americans affected each year, with older adults, whose immune systems are less robust, being most vulnerable. Once the rash and its painful sequel appear, treatment options are limited at best and carry their own set of complications.

While the search for relief costs Americans over $500 million each year, the worst news until recently has been that shingles and its painful complication could happen to any one of us. There were no preventive measures available.

But in 2006, the Food and Drug Administration approved a new vaccine against shingles. Clinical trials on the vaccine revealed that it could, with relatively few side effects, reduce the risk of developing shingles by more than half and the risk of post-herpetic neuralgia by over two-thirds. In 2008, a national panel of experts on immunizations at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention went on to recommend the vaccine to all adults age 60 and older.

At the time, the shingles vaccine seemed to embody the best of medicine, both old school and new. Its advent was contemporary medicine’s elegant response to a once intractable, age-old problem. It didn’t necessarily put an end to the spread of disease, in this case chicken pox; but it dramatically reduced the burden of illness for the affected individual. And, most notably, its utter simplicity was a metaphoric shot-in-the-arm for old-fashioned doctoring values. Among the increasingly complex and convoluted suggestions for health care reform that were brewing at that moment, here was a powerful intervention that relied on only three things: a needle, a syringe and a patient-doctor relationship rooted in promoting wellness.

Not.

In the two years since the vaccine became available, fewer than 10 percent of all eligible patients have received it. Despite the best intentions of patients and doctors (and no shortage of needles and syringes), the shingles vaccine has failed to take hold, in large part because of the most modern of obstacles. What should have been a widely successful and simple wellness intervention between doctors and their patients became a 21st century Rube Goldberg-esque nightmare.

Last month in The Annals of Internal Medicine, researchers from the University of Colorado in Denver and the C.D.C. surveyed almost 600 primary care physicians and found that fewer than half strongly recommended the shingles vaccine. Doctors were not worried about safety — a report in the same issue of the journal confirmed that the vaccine has few side effects; rather, they were concerned about patient cost.

Although only one dose is required, the vaccination costs $160 to $195 per dose, 10 times more than other commonly prescribed adult vaccines; and insurance carriers vary in the amount they will cover. Thus, while the overwhelming majority of doctors in the study did not hesitate to strongly recommend immunizations against influenza and pneumonia, they could not do the same with the shingles vaccine.

“It’s just a shot, not a pap smear or a colonoscopy,” said Dr. Laura P. Hurley, lead author and assistant professor of medicine at the University of Colorado in Denver. “But the fact is that it is an expensive burden for all patients, even those with private insurance and Medicare because it is not always fully reimbursed.”

Moreover, many private insurers require patients to pay out of pocket first and apply for reimbursement afterward. And because the shingles vaccine is the only vaccine more commonly given to seniors that has been treated as a prescription drug, eligible Medicare patients must also first pay out of pocket then submit the necessary paperwork in order to receive the vaccine in their doctor’s office. It’s a complicated reimbursement process that stands in stark contrast to the automatic, seamless and fully covered one that Medicare has for flu and pneumonia vaccines.

Despite this payment maze, some physicians have tried to stock and administer the vaccine in their offices; many, however, eventually stop because they can no longer afford to provide the immunizations. “If you have one out of 10 people who doesn’t pay for the vaccine, your office loses money,” said Dr. Allan Crimm, the managing partner of Ninth Street Internal Medicine, a primary care practice in Philadelphia. Over time, Dr. Crimm’s practice lost thousands of dollars on the shingles vaccine. “It’s indicative of how there are perverse incentives that make it difficult to accomplish what everybody agrees should happen.”

Even bypassing direct reimbursement is fraught with complications for doctors and patients. A third of the physicians surveyed in the University of Colorado study resorted to “brown bagging,” a term more frequently used to describe insurers who have patients carry chemotherapy drugs from a cheaper supplier to their oncologists’ offices. In the case of the shingles vaccine, the study doctors began writing prescriptions for patients to pick up the vaccine at the pharmacy and then return to have it administered in their offices. However, the shingles vaccine must be frozen until a few minutes before administration, and a transit time greater than 30 minutes between office and pharmacy can diminish the vaccine’s effectiveness.

Dr. Crimm and the physicians in his office finally resorted to what another third of the physicians in the study did: they gave patients prescriptions to have the vaccine administered at pharmacies that offered immunization clinics. But when faced with the added hassles of taking additional time off from work and making a separate trip to the pharmacy, not all patients followed through. “Probably about 60 percent of our patients finally did get the vaccine at the pharmacy,” Dr. Crimm estimated. “This is as opposed to 98 percent of our patients getting the pneumonia and influenza vaccines, immunizations where they just have to go down the hall because we stock it, roll up their sleeves then walk out the door.”

With all of these barriers, it comes as no surprise that in the end only 2 percent to 7 percent of patients are immunized against shingles. “There’s just so much that primary care practices must take care of with chronic diseases like obesity and diabetes and heart disease,” Dr. Hurley noted. “If a treatment isn’t easy to administer, then sometimes it just falls to the bottom of the list of things for people to do.”

“Shingles vaccination has become a disparity issue,” Dr. Hurley added. “It’s great that this vaccine was developed and could potentially prevent a very severe disease. But we have to have a reimbursement process that coincides with these interventions. Just making these vaccines doesn’t mean that they will have a public health impact.”

Few Takers for the Shingles Vaccine

By Paula Span : NY Times : January 12, 2011

The good news about the shingles vaccine, recommended for all adults age 60 or older with normal immune systems, is that it works even better than scientists first thought.

A study published on Tuesday in The Journal of the American Medical Association reported that the rate of shingles was 55 percent lower in the 75,761 people age 60 or older who received the vaccine, compared with those who did not.

Formally known as herpes zoster, shingles occurs when the varicella zoster virus, which also causes chickenpox and can lay dormant in nerve cells for decades, reactivates to cause a painful skin rash. In some, the intense pain can persist for months after the rash clears, a complication called postherpetic neuralgia.

About 30 percent of Americans develop shingles at some point, a Mayo Clinic team reported in 2007; the researchers also found that postherpetic neuralgia occurs in 18 percent of shingles patients, but in a third of those 79 or older.

Medical researchers can’t explain why some people with latent varicella infections develop shingles and others never do. But the new vaccine certainly seems to better the odds of dodging this scourge.

Data published in 2005, which led to the vaccine’s approval by the Food and Drug Administration, found its effectiveness lessened in those over 80. (Octogenarians were advised to get the shot anyway.) In the new study, however, the shingles vaccine was shown to reduce the risk of outbreaks in all age cohorts and races, and among those with chronic diseases.

“This vaccine has the potential to annually prevent tens of thousands of cases” of shingles, the authors wrote.

So what’s the bad news? Only a sliver of the senior population at risk for shingles is getting vaccinated. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recently published the data on vaccination coverage among older adults in 2009. Nearly two-thirds of those over 65 got flu vaccines that year, the agency found, and more than 60 percent were vaccinated against pneumonia.

But just 10 percent received the shingles vaccine. “Bottom line, 10 percent is a pretty poor number,” Dr. Rafael Harpaz, an epidemiologist at the C.D.C. and co-author of Tuesday’s report, said in an interview.

Various factors seem to be preventing wider use of the vaccine, Dr. Harpaz explained. First, it is still fairly new, introduced in 2006. And on occasion its manufacturer, Merck, has been unable to produce enough, twice causing shortages that lasted for months. The most recent one is just ending, and an ample supply is promised by the end of this month. But uncertainty about availability has frustrated both doctors and patients.

And how many older patients even know to ask for the shot? “Merck has not aggressively marketed this vaccine at all,” Dr. Harpaz said. “And other players aren’t promoting it either, like health departments or even the C.D.C., so there’s less awareness of it.”

But it’s also harder to make the shingles vaccine available. “It’s the most expensive vaccine recommended to the elderly,” he said. An inoculation costs about $200, and not all insurance plans cover it.

Medicare does, but through the drug benefit, Part D. Most people will want to get it in doctors’ offices, however, and doctors are paid by a different Medicare benefit, Part B. This means that patients frequently have to pay for the vaccine and injection out of pocket, then get reimbursed. In some cases, they buy the vaccine at a pharmacy, where Medicare covers most of the cost, and then carry it to a doctor’s office for the injection — a bad idea, since it needs to remain frozen. Such financial complications are the major barrier to use, The Annals of Internal Medicine reported earlier this year.

Moreover, internists and other doctors who treat adults may have trouble storing the vaccine; they don’t usually have freezers in their offices. Family practitioners often do, though, because they treat children and pediatric vaccines are also frozen.

Yes, the distribution and marketing of the vaccine clearly still need work. But as caregivers, we may be more conscious than our parents of its availability, better able to ascertain which doctor or pharmacy has it and to cope with the resulting paperwork, perhaps better able to shell out $200.

So help spread the word. Shingles is a mean disease, and the older the victim, the meaner it gets. Apart from the pain of that postherpetic neuralgia, it can attack the eyes and permanently damage vision. And once you get an outbreak, you can get another. And another.

By Paula Span : NY Times : January 12, 2011

The good news about the shingles vaccine, recommended for all adults age 60 or older with normal immune systems, is that it works even better than scientists first thought.

A study published on Tuesday in The Journal of the American Medical Association reported that the rate of shingles was 55 percent lower in the 75,761 people age 60 or older who received the vaccine, compared with those who did not.

Formally known as herpes zoster, shingles occurs when the varicella zoster virus, which also causes chickenpox and can lay dormant in nerve cells for decades, reactivates to cause a painful skin rash. In some, the intense pain can persist for months after the rash clears, a complication called postherpetic neuralgia.

About 30 percent of Americans develop shingles at some point, a Mayo Clinic team reported in 2007; the researchers also found that postherpetic neuralgia occurs in 18 percent of shingles patients, but in a third of those 79 or older.

Medical researchers can’t explain why some people with latent varicella infections develop shingles and others never do. But the new vaccine certainly seems to better the odds of dodging this scourge.

Data published in 2005, which led to the vaccine’s approval by the Food and Drug Administration, found its effectiveness lessened in those over 80. (Octogenarians were advised to get the shot anyway.) In the new study, however, the shingles vaccine was shown to reduce the risk of outbreaks in all age cohorts and races, and among those with chronic diseases.

“This vaccine has the potential to annually prevent tens of thousands of cases” of shingles, the authors wrote.

So what’s the bad news? Only a sliver of the senior population at risk for shingles is getting vaccinated. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recently published the data on vaccination coverage among older adults in 2009. Nearly two-thirds of those over 65 got flu vaccines that year, the agency found, and more than 60 percent were vaccinated against pneumonia.

But just 10 percent received the shingles vaccine. “Bottom line, 10 percent is a pretty poor number,” Dr. Rafael Harpaz, an epidemiologist at the C.D.C. and co-author of Tuesday’s report, said in an interview.

Various factors seem to be preventing wider use of the vaccine, Dr. Harpaz explained. First, it is still fairly new, introduced in 2006. And on occasion its manufacturer, Merck, has been unable to produce enough, twice causing shortages that lasted for months. The most recent one is just ending, and an ample supply is promised by the end of this month. But uncertainty about availability has frustrated both doctors and patients.

And how many older patients even know to ask for the shot? “Merck has not aggressively marketed this vaccine at all,” Dr. Harpaz said. “And other players aren’t promoting it either, like health departments or even the C.D.C., so there’s less awareness of it.”

But it’s also harder to make the shingles vaccine available. “It’s the most expensive vaccine recommended to the elderly,” he said. An inoculation costs about $200, and not all insurance plans cover it.

Medicare does, but through the drug benefit, Part D. Most people will want to get it in doctors’ offices, however, and doctors are paid by a different Medicare benefit, Part B. This means that patients frequently have to pay for the vaccine and injection out of pocket, then get reimbursed. In some cases, they buy the vaccine at a pharmacy, where Medicare covers most of the cost, and then carry it to a doctor’s office for the injection — a bad idea, since it needs to remain frozen. Such financial complications are the major barrier to use, The Annals of Internal Medicine reported earlier this year.

Moreover, internists and other doctors who treat adults may have trouble storing the vaccine; they don’t usually have freezers in their offices. Family practitioners often do, though, because they treat children and pediatric vaccines are also frozen.

Yes, the distribution and marketing of the vaccine clearly still need work. But as caregivers, we may be more conscious than our parents of its availability, better able to ascertain which doctor or pharmacy has it and to cope with the resulting paperwork, perhaps better able to shell out $200.

So help spread the word. Shingles is a mean disease, and the older the victim, the meaner it gets. Apart from the pain of that postherpetic neuralgia, it can attack the eyes and permanently damage vision. And once you get an outbreak, you can get another. And another.