- RETIREMENT ANNOUNCEMENT

- HOME PAGE

- "MYCHART" the new patient portal

- BELMONT MEDICAL ASSOCIATES

- MOUNT AUBURN HOSPITAL

- EMERGENCIES

- PRACTICE PHILOSOPHY

- MY RESUME

- TELEMEDICINE CONSULTATION

- CONTACT ME

- LAB RESULTS

- ePRESCRIPTIONS

- eREFERRALS

- RECORD RELEASE

- MEDICAL SCRIBE

- PHYSICIAN ASSISTANT (PA)

- Medicare Annual Wellness Visit

- Case management/Social work

- Quality Care Measures

- Emergency closing notice

- FEEDBACK

- Talking to your doctor

- Choosing..... and losing a doctor

- INDEX A - Z

- ALLERGIC REACTIONS

- Alternative Medicine

- Alzheimer's Disease

- Bladder Problems

- Blood disorders

- Cancer Concerns

- GENETIC TESTING FOR HEREDITARY CANCER

- Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

- Controversial Concerns

- CPR : Learn and save a life

- CRP : Inflammatory marker

- Diabetes Management

- Dizziness, Vertigo,Tinnitus and Hearing Loss

- EXERCISE

- FEMALE HEALTH

-

GASTROINTESTINAL topics

- Appendicitis

- BRAT diet

- Celiac Disease or Sprue

- Crohn's Disease

- Gastroenterologists for Colon Cancer Screening

- Colonoscopy PREP

- Constipation

- Gluten sensitivity, but not celiac disease

- Heartburn and GERD

- Hemorrhoids and Anal fissure

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- NASH : Non Alcoholic Steato Hepatitis

- FEET PROBLEMS

- HEART RELATED topics

-

INFECTIOUS DISEASES

- Antibiotic Resistance

- Cat bites >

- Clostridia difficile infection - the "antibiotic associated germ"

- CORONA VIRUS

- Dengue Fever and Chikungunya Fever

- Food borne illnesses

- Shingles Vaccine

- Hepatitis B

- Hepatitis C

- Herpes

- Influenza

- Helicobacter pylori - the "ulcer germ"

- HIV Screening

- Lyme and other tick borne diseases

- Measles

- Meningitis

- MRSA (Staph infection)

- Norovirus

- Sexually Transmitted Diseases

- Shingles (Herpes Zoster)

- Sinusitis

- West Nile Virus

- Whooping Cough (Pertussis)

- Zika virus and pregnancy

- INSURANCE related topics

- KIDNEY STONES

- LEG CRAMPS

- LIBRARY for patients

- LIFE DECISIONS

- MALE HEALTH

- Medication/Drug side effects

- MEDICAL MARIJUANA

- MENTAL HEALTH

- Miscellaneous Articles

-

NUTRITION - EXERCISE - WEIGHT

- Cholesterol : New guidelines for treatment

- Advice to lower your cholesterol

- Cholesterol : Control

- Cholesterol : Raising your HDL Level

- Exercise

- Food : Making Smart Choices

- Food : Making Poor Choices

- Food : Grape Fruit and Drug Interaction

- Food : Vitamins, Minerals and Supplements

- Omega 3 fatty acids

- Vitamin B12 deficiency

- Vitamin D

- Weight Loss

- ORTHOPEDICS

- PAIN

- PATIENTS' RIGHTS

- SKIN

- SLEEP

- SMOKING

- STROKE

- THYROID

- SUBSTANCE ABUSE

- Travel and Vaccination

- TREMOR

- Warfarin Anticoagulation

- OTHER STUFF FOLLOWS

- Fact or Opinion?

- Hippocratic Oath

- FREE ADVICE.......for what its worth!

- LAUGHTER.....is the best medicine

- Physicians Pet Peeves

- PHOTO ALBUM - its not all work!

- Cape Town, South Africa

- Tribute page

- The 100 Club

- Free Wi-Fi

Chronic Pain

Living With Pain That Just Won’t Go Away

By Jane E. Brody : NY Times Article : November 6, 2007

Pain, especially pain that doesn’t quit, changes a person. And rarely for the better. The initial reaction to serious pain is usually fear (what is wrong with me, and is it curable?), but pain that fails to respond to treatment leads to anxiety, depression, anger and irritability.

At age 29, Walter, a computer programmer in Silicon Valley, developed a repetitive stress injury that caused severe pain in his hands when he touched the keyboard. The injury did not respond to rest. The pain became worse, spreading to his shoulders, neck and back.

Unable to work, lift, carry or squeeze anything without enduring days of crippling pain, Walter could no longer drive, open a jar or even sign his name.

“At age 29, I was on Social Security disability, basically confined to home, and my life seemed to be over,” Walter recalls in “Living With Chronic Pain,” by Dr. Jennifer Schneider. Severely depressed, he wonders whether his life is worth living.

Yet, despite his limited mobility and the pain-induced frown lines in his face, to look at Walter is to see a strapping, healthy young man. It is hard to tell that he, or any other person beset with chronic pain, is suffering as much as he says he is.

Pain is an invisible, subjective symptom. The body of a chronic pain sufferer — someone with fibromyalgia, for example, or back pain — usually appears intact. There are no objective tests to detect pain or measure its intensity. You just have to take a person’s word for it.

Nearly 10 percent of people in the United States suffer from moderate to severe chronic pain, and the prevalence increases with age. Complete relief from chronic pain is rare even with the best treatment, which is itself a rarity. Doctors and patients alike, who misunderstand the effects of narcotics, are too often reluctant to use drugs like opioids, which can relieve acute, as well as chronic, pain and may head off the development of a chronic pain syndrome.

Why Pain Persists

The problems with chronic pain are that it never really ends and does not always respond to treatment. If the pain initially was caused by an injury or illness, it can persist long after the injury has healed or the illness defeated because permanent changes have occurred in the body.

Mark Grant, a psychologist in Australia who specializes in managing chronic pain, says the notion that “physical injury equals pain” is overly simplistic. “We now know that pain is caused and maintained by a combination of physical, psychological and neurological factors,” Mr. Grant writes on his Web site, www.overcomingpain.com. With chronic pain, a persistent physical cause often cannot be determined.

“Chronic pain can be caused by muscle tension, changes in circulation, postural imbalances, psychological distress and neurological changes,” Mr. Grant says on his site. “It is also known that unrelieved pain is associated with increased metabolic rate, spontaneous excitation of the central nervous system, changes in blood circulation to the brain and changes in the limbic-hypothalamic system,” the region of the brain that regulates emotions.

Dr. Schneider, the author of “Living With Chronic Pain” (Healthy Living Books, Hatherleigh Press, 2004), is a specialist in pain management in Tucson, Ariz. In her book, she points out that the nervous system is responsible for the two major types of chronic pain.

One, called nociceptive pain, “arises from injury to muscles, tendons and ligaments or in the internal organs,” she writes. Undamaged nerve cells responding to an injury outside themselves transmit pain signals to the spinal cord and then to the brain. The resulting pain is usually described as deep and throbbing. Examples include chronic low back pain, osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, fibromyalgia, headaches, interstitial cystitis and chronic pelvic pain.

The second type, neuropathic pain, “results from abnormal nerve function or direct damage to a nerve.” Among the causes are shingles, diabetic neuropathy, reflex sympathetic dystrophy, phantom limb pain, radiculopathy, spinal stenosis, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, stroke and spinal cord injury.

The damaged nerve fibers “can fire spontaneously, both at the site of the injury and at other places along the nerve pathway” and “can continue indefinitely even after the source of the injury has stopped sending pain messages,” Dr. Schneider writes.

“Neuropathic pain can be constant or intermittent, burning, aching, shooting or stabbing, and it sometimes radiates down the arms or legs,” she adds. This kind of pain tends “to involve exaggerated responses to painful stimuli, spread of pain to areas that were not initially painful, and sensations of pain in response to normally nonpainful stimuli such as light touch.” It is often worse at night and may involve abnormal sensations like tingling, pins and needles, and intense itching.

Some chronic pain syndromes involve both nociceptive and neuropathic pain. A common example is sciatica; a pinched nerve causes back pain that radiates down the leg. In some cases, the pain of sciatica is not felt in the back but only in the leg, making the cause difficult to diagnose without an M.R.I.

Beyond Physical Problems

The consequences of chronic pain typically extend well beyond the discomfort from the sensation of pain itself. Dr. Schneider lists these potential physical effects: poor wound healing, weakness and muscle breakdown, decreased movement that can lead to blood clots, shallow breathing and suppressed coughing that raise the risk of pneumonia, sodium and water retention in the kidneys, raised heart rate and blood pressure, weakened immune system, a slowing of gastrointestinal motility, difficulty sleeping, loss of appetite and weight, and fatigue.

But that is hardly the end of it. The psychological and social consequences of chronic pain can be enormous. Unremitting pain can rob a person of the ability to enjoy life, maintain important relationships, fulfill spousal and parental responsibilities, perform well at a job or work at all.

The economic burdens can be severe, especially when the patient is the primary breadwinner or holds a job that provides the family’s health insurance. Only about half of patients with chronic pain “who undergo comprehensive multidisciplinary pain rehabilitation are able to return to work,” Dr. Schneider reports.

As for the notion that chronic pain patients are often malingering — seeking attention and escape from responsibilities — pain specialists say that is nonsense. No one in his right mind — and most patients were in their right minds before the pain began — would trade a fulfilling life for the misery of chronic pain.

Chronic Pain: A Burden Often Shared

By Jane E. Brody : NY Times Article : November 13,2007

Chronic pain is a family problem. When people experience unrelenting pain, everyone they live with and love is likely to suffer. The frustration, anxiety, stress and depression that often go with chronic pain can also afflict family members and friends who feel helpless to provide relief.

Healthy family members are often overworked from assuming the duties of the person in pain. They have little time and energy for friends and other diversions, and they may fret over how to make ends meet when expenses rise and family incomes shrink.

It is easy to see how tempers can flare at the slightest provocation. The combination of unrelieved suffering on the one hand and constant stress and fatigue on the other can be highly volatile, even among the most loving couples — whose burdens are often worsened by a decline of intimacy.

“Family members are rarely considered by doctors who treat pain,” said Dennis C. Turk, a pain management researcher at the University of Washington in Seattle. “Yet a study we did found that family members were up to four times more depressed than the patients.”

But pain experts say there is much that family members and friends can do to improve the situation.

Step one is to recognize that chronic pain is not an individual problem. Let the patient know that you are in this together and will fight it together. When the patient is moody and irritable, try not to take it personally.

Step two involves learning as much as you can about the condition and how to treat it. Eliminating the pain may not be possible, but there often ways to reduce it. (See next week’s column on treating chronic pain.)

Some of the ideas below were adapted from the American Chronic Pain Association’s Family Manual, written by Penney Cowan, the association’s founder and executive director.

“Twenty-five percent of the calls we get are from family members looking for help,” Ms. Cowan said in an interview last week. “Family members are just as isolated, controlled, frustrated, guilt-ridden and confused by chronic pain as is the person in pain.”

Acknowledge your feelings. You may feel guilty about not being able to relieve the distress of someone you love. You may be anxious about financial problems.

You may be distressed by the reactions of other people, who might lack an understanding of chronic pain and suggest that the patient is malingering — faking the pain to avoid work or family responsibilities. At a time when you most need the understanding and support of others, they may seem unsympathetic, even hostile.

But the most common reaction is resentment, over a withdrawal of the patient’s affection and sexual intimacy, the unending care required by the patient, the need to add the patient’s responsibilities to your own, the decline or loss of a social life and time spent with friends. You may resent having to abandon an enjoyable lifestyle or plans for the future.

If the patient was the family breadwinner and is now unable to work, you may have to find a job and, at the same time, do most or all of the chores at home and care for the patient. Chronic exhaustion can erode your temper as well as your own health.

It is all too easy to react to such feelings in emotionally destructive ways. Owning up to them can help you cope more successfully.

Help the patient stay involved. Chronic pain can rob people of their abilities and force them to be cared for by others, leaving them to feel worthless and guilty over not contributing to the family’s welfare. Whether you are the patient’s primary or intermittent caregiver, it is important not to contribute to feelings of helplessness.

Encourage patients to participate as fully as possible in family plans and activities, household chores, discussions and decisions. Perhaps they can no longer do yardwork, but they may still be able to help with cooking, setting the table, washing the dishes, caring for children, handling family finances, making phone calls or shopping by phone. Feeling useful can bolster a patient’s self-esteem and mood.

“For each action the pain person says he or she can no longer do, point out something he or she can do,” the pain association’s manual suggests.

Don’t become a go-for. Chronic pain patients should be encouraged to do whatever they can do for themselves. It is important for you to know when to step in and when to step back. Recognize the patient’s abilities and limitations — consider having an evaluation made by an occupational therapist — and let the patient participate as much as possible in daily activities and self-care.

Communicate. “Open, two-way communication is crucial to dealing effectively with chronic pain,” said Dr. Turk, of the University of Washington. “Family members need to know how they can be helpful and what might be hurtful.”

Failure to communicate honestly and openly can become a cancer on a relationship, be it with a spouse, parent or child. If chronic pain has disrupted family plans, discuss a reordering of priorities. It may be possible to do more than you think.

You have a right to say that you are tired and need to rest, that you need a break from the routine lest you burn out, and that you need to maintain friendships and pursue enjoyable activities outside the home from time to time.

Likewise, the patient has a right and responsibility to express fear, disappointment, guilt and bad feelings about the behavior of some people, as well as gratitude for the help you and others provide.

Ask periodically what the patient might like to discuss with you or do with you. And try not to rise to the bait when the patient is critical or lashes out at you despite all you do. Most often, you are not really the target. But there may be no one else with whom the patient feels safe to express distress.

Take care of yourself. Enlist all the help you can get from family members and friends. Older children can clean the house and prepare meals. Friends and relatives who offer to help can be given tasks that fit their abilities, even if it is just accompanying the patient to a medical appointment. If they haven’t offered, ask.

When necessary, hire others, including neighborhood teenagers, to help out. If you are reluctant to leave the patient home alone, ask a friend or neighbor to stay for a few hours or to look in on the patient every so often so that you can get out for a while.

Don’t neglect your own physical well-being. Eat regular meals, get enough sleep and get regular physical exercise. And be sure to keep up with medical checkups and screening exams. If you get sick, you won’t be much use to the patient in pain.

Many Treatments Can Ease Chronic Pain

By Jane E. Brody : NY Times Article : November 20, 2007

There is one undeniable fact about chronic pain: More often than not, it is untreated or undertreated. In a survey last year by the American Pain Society, only 55 percent of all patients with noncancer-related pain and fewer than 40 percent with severe pain said their pain was under control.

But it does not have to be this way. There are myriad treatments — drugs, devices and alternative techniques — that can greatly ease persistent pain, if not eliminate it.

Chronic pain is second only to respiratory infections as a reason patients seek medical care. Yet because physicians often do not take a patient’s pain seriously or treat it adequately, nearly half of chronic-pain patients have changed doctors at least once, and more than a quarter have changed doctors at least three times.

In an ideal world, every such patient would be treated by a pain specialist familiar with the techniques for alleviating pain. But “very few patients with chronic disabling pain have access to a pain specialist,” a team of experts wrote in a supplement to Practical Pain Management in September.

As a result, most patients have to rely on primary care physicians for pain treatment, obliging them to learn as much as they can about treatment approaches and to persist in their search for relief.

Medications

Most chronic pain patients end up taking a cocktail of pills that complement one another.

These are three categories of drugs useful for treating chronic pain:

For patients with chronic, continuous pain, using a slowly released opioid like oxycodone (Oxycontin), morphine or fentanyl (administered through a skin patch or lozenge on a stick) is preferred. These drugs minimize or eliminate the hills and valleys of pain and reduce the medication patients need.

The usual side effects — sedation, nausea, confusion — soon disappear except for constipation, which can be treated.

Pain specialists also recommend that patients taking slow-release opioids have on hand a fast-acting one like Percocet (oxycodone with acetaminophen) to treat breakthrough pain.

Methadone, a synthetic opioid, is another option for managing chronic pain, especially neuropathic pain, but it has to be taken several times a day. It is metabolized in the liver, along with other drugs that can affect blood levels of methadone.

Other Remedies

Here are some groups that can provide information on managing chronic pain:

Rewiring the Brain to Ease Pain

Brain Scans Fuel Efforts to Teach Patients How to Short-Circuit Hurtful Signals

By Melinda Beck : WSJ; November 15, 2011

How you think about pain can have a major impact on how it feels.

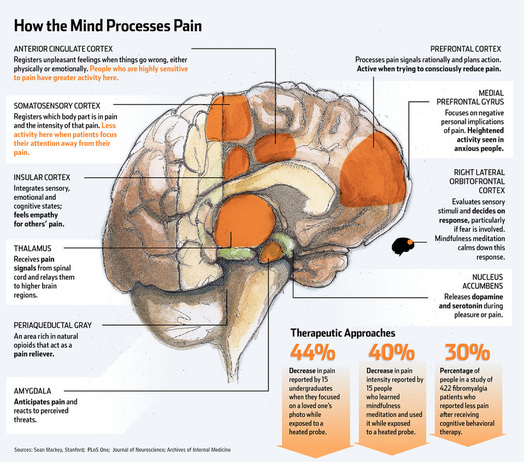

That's the intriguing conclusion neuroscientists are reaching as scanning technologies let them see how the brain processes pain.

That's also the principle behind many mind-body approaches to chronic pain that are proving surprisingly effective in clinical trials.

Some are as old as meditation, hypnosis and tai chi, while others are far more high tech. In studies at Stanford University's Neuroscience and Pain Lab, subjects can watch their own brains react to pain in real-time and learn to control their response—much like building up a muscle. When subjects focused on something distracting instead of the pain, they had more activity in the higher-thinking parts of their brains. When they "re-evaluated" their pain emotionally—"Yes, my back hurts, but I won't let that stop me"—they had more activity in the deep brain structures that process emotion. Either way, they were able to ease their own pain significantly, according to a study in the journal Anesthesiology last month.

While some of these therapies have been used successfully for years, "we are only now starting to understand the brain basis of how they work, and how they work differently from each other," says Sean Mackey, chief of the division of pain management at Stanford.

He and his colleagues were just awarded a $9 million grant to study mind-based therapies for chronic low back pain from the government's National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM).

Some 116 million American adults—one-third of the population—struggle with chronic pain, and many are inadequately treated, according to a report by the Institute of Medicine in July.

Yet abuse of pain medication is rampant. Annual deaths due to overdoses of painkillers quadrupled, to 14,800, between 1998 and 2008, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The painkiller Vicodin is now the most prescribed drug in the U.S.

"There is a growing recognition that drugs are only part of the solution and that people who live with chronic pain have to develop a strategy that calls upon some inner resources," says Josephine Briggs, director of NCCAM, which has funded much of the research into alternative approaches to pain relief.

Already, neuroscientists know that how people perceive pain is highly individual, involving heredity, stress, anxiety, fear, depression, previous experience and general health. Motivation also plays a huge role—and helps explain why a gravely wounded soldier can ignore his own pain to save his buddies while someone who is depressed may feel incapacitated by a minor sprain.

"We are all walking around carrying the baggage, both good and bad, from our past experience and we use that information to make projections about what we expect to happen in the future," says Robert Coghill, a neuroscientist at Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center in Winston-Salem, N.C.

Dr. Coghill gives a personal example: "I'm periodically trying to get into shape—I go to the gym and work out way too much and my muscles are really sore, but I interpret that as a positive. I'm thinking, 'I've really worked hard.' " A person with fibromyalgia might be getting similar pain signals, he says, but experience them very differently, particularly if she fears she will never get better.

Dr. Mackey says patients' emotional states can even predict how they will respond to an illness. For example, people who are anxious are more likely to experience pain after surgery or develop lingering nerve pain after a case of shingles.

That doesn't mean that the pain is imaginary, experts stress. In fact, brain scans show that chronic pain (defined as pain that lasts at least 12 weeks or a long time after the injury has healed) represents a malfunction in the brain's pain processing systems. The pain signals take detours into areas of the brain involved with emotion, attention and perception of danger and can cause gray matter to atrophy. That may explain why some chronic pain sufferers lose some cognitive ability, which is often thought to be a side effect of pain medication.

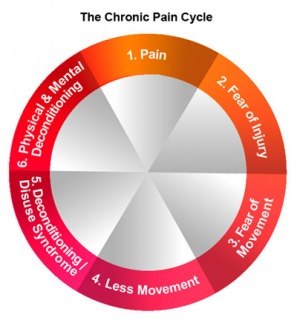

The dysfunction "feeds on itself," says Dr. Mackey. "You get into a vicious circle of more pain, more anxiety, more fear, more depression. We need to interrupt that cycle."

One technique is attention distraction, simply directing your mind away from the pain. "It's like having a flashlight in the dark—you choose what you want to focus on. We have that same power with our mind," says Ravi Prasad, a pain psychologist at Stanford.

Guided imagery, in which a patient imagines, say, floating on a cloud, also works in part by diverting attention away from pain. So does mindfulness meditation. In a study in the Journal of Neuroscience in April, researchers at Wake Forest taught 15 adults how to meditate for 20 minutes a day for four days and subjected them to painful stimuli (a probe heated to 120 degrees Fahrenheit on the leg).

Brain scans before and after showed that while they were meditating, they had less activity in the primary somatosensory cortex, the part of the brain that registers where pain is coming from, and greater activity in the anterior cingulate cortex, which plays a role in handling unpleasant feelings. Subjects also reported feeling 40% less pain intensity and 57% less unpleasantness while meditating.

"Our subjects really looked at pain differently after meditating. Some said, 'I didn't need to say ouch,' " says Fadel Zeidan, the lead investigator.

Techniques that help patients "emotionally reappraise" their pain rather than ignore it are particularly helpful when patients are afraid they will suffer further injury and become sedentary, experts say.

Cognitive behavioral therapy, which is offered at many pain-management programs, teaches patients to challenge their negative thoughts about their pain and substitute more positive behaviors.

Even getting therapy by telephone for six months helped British patients with fibromyalgia, according to a study published online this week in the Archives of Internal Medicine. Nearly 30% of patients receiving the therapy reported less pain, compared with 8% of those getting conventional treatments. The study noted that in the U.K., no drugs are approved for use in fibromyalgia and access to therapy or exercise programs is limited, if available at all.

Anticipating relief also seems to make it happen, research into the placebo effect has shown. In another NCCAM-funded study, 48 subjects were given either real or simulated acupuncture and then exposed to heat stimuli.

Both groups reported similar levels of pain relief—but brain scans showed that actual acupuncture interrupted pain signals in the spinal cord while the sham version, which didn't penetrate the skin, activated parts of the brain associated with mood and expectation, according to a 2009 study in the journal Neuroimage.

One of Dr. Mackey's favorite pain-relieving techniques is love. He and colleagues recruited 15 Stanford undergraduates and had them bring in photos of their beloved and another friend. Then he scanned their brains while applying pain stimuli from a hot probe. On average, the subject reported feeling 44% less pain while focusing on their loved one than on their friend. Brain images showed they had strong activity in the nucleus accumbens, an area deep in the brain involved with dopamine and reward circuits.

Experts stress that much still isn't known about pain and the brain, including whom these mind-body therapies are most appropriate for. They also say it's important that anyone who is in pain get a thorough medical examination. "You can't just say, 'Go take a yoga class.' That's not a thoughtful approach to pain management," says Dr. Briggs.

Pain Relief for Some, With an Odd Tradeoff

By Tara Parker-Pope : NY Times Article : January 8. 2008

For people with chronic pain, relief comes with a tradeoff. Bed rest means missing out on life. Drugs take the edge off, but they also dull the senses and the mind.

But there’s another potential option: implantable stimulators that blunt pain with electrical impulses. In this case, the tradeoff is living with a low-grade buzzing sensation in place of the pain.

The devices, which are implanted near the spine, are not widely used. They are expensive, don’t work for everyone and rarely offer complete relief. Industry officials estimate that fewer than 10 percent of eligible patients opt for the treatment.

But when they do work, they can be life-changing. Carolyn Stewart, 45, of Clifton, N.J., has lived with chronic back pain since she was 18, when she had surgery after a car accident. Then four years ago, a procedure for a collapsed lung accidentally resulted in nerve damage that caused excruciating pain. “I just want to sleep normally and not have pain that wakes me up every 20 minutes,” she said.

Ms. Stewart has been using pain drugs to cope, but side effects, including fatigue and constipation, only add to her discomfort. A few years ago she did a “test drive” of a spinal cord stimulator and experienced a significant drop in her pain. Insurance troubles delayed a permanent implant, but this month she is finally undergoing surgery to attach the device to her spinal cord. “It’s not going to be 100 percent,” she said. “But I will be happy with a 50 percent change.”

Not every patient feels that way. Ms. Stewart’s physician, Dr. Andrew G. Kaufman, director of interventional pain management at Overlook Hospital in Summit, N.J., described a patient who tested a stimulator and experienced “unbelievable” pain relief, yet simply couldn’t adjust to the sensation created by the device and decided not to keep it. “She couldn’t get over the background buzzing,” Dr. Kaufman said.

Still, most patients accept this vibrating version of white noise, says Dr. Richard North, a retired neurosurgery professor at Johns Hopkins who developed several patents related to the technology, although he no longer receives royalties.

“When they first feel the sensation they say, ‘That’s weird,’” said Dr. North, who treats patients at the LifeBridge Health Brain and Spine Institute in Baltimore. “It quickly becomes clear that ‘weird’ is going to be just fine if it replaces the pain.”

Chronic pain is a particularly difficult problem to understand and solve. Pain is normal after an injury or because of a health problem. But sometimes the nerves misfire and continue sending intense pain signals to the brain even after the injury heals. Dr. Vijay B. Vad, a sports medicine specialist at the Hospital for Special Surgery in Manhattan, compares the problem to a thermostat in a cool room. “If it’s 65 degrees in the house, but the thermostat thinks it’s 50 degrees, the heat keeps running,” Dr. Vad said.

The condition, complex regional pain syndrome, or C.R.P.S., typically develops after a medical procedure or an accident. But even minor injuries, like a sprain from a fall, can cause it. The syndrome may follow 5 percent of all injuries, according to the Reflex Sympathetic Dystrophy Association, an advocacy group for people with chronic pain.

Spinal cord stimulation works by implanting an electrode near the spinal cord, inserted through the same place where epidural pain relief is injected for women in labor. Electrical pulses scramble or block the pain signals traveling through the nervous system, preventing them from reaching the brain.

But spinal cord stimulators offer significant relief to only about half the patients who try them. In September, the journal Pain published the largest-ever clinical trial of spinal cord stimulators, comparing their use with conventional pain therapies, including drugs, nerve blocks and physical therapy. The study, which was financed by the implant maker Medtronic, followed 100 patients who had undergone spinal surgery and had developed chronic pain in one or both legs.

Every patient received conventional pain treatment, but half were also given a spinal cord implant. Pain fell by half for 48 percent of the implant patients but only 9 percent of the others.

The implants cost about $20,000, and the procedure, hospital care and follow-up can bring the total bill to about $40,000. In August, the medical journal Neurosurgery showed that spinal cord implants were far cheaper than additional operations to treat pain.

Another concern is that patients who require high doses of stimulation drain the battery quickly, requiring surgery to replace the device. New rechargeable versions of the stimulators have helped resolve that concern.

For some patients, relief is only temporary, and the pain returns. Doctors say simple adjustments to the device may solve that problem.

“Sometimes efficacy wanes over time, but I still believe in them,” said Dr. Kaufman, also an assistant professor of anesthesiology at the New Jersey Medical School. “When drugs don’t work, what else is there?”

Antidepressants Don’t Ease Back Pain

By Tara Parker-Pope : NY Times Article : February 4, 2008

Nearly one in four primary care doctors prescribes antidepressants as a treatment for low back pain. But a new report shows there’s no evidence the drugs offer any relief.

The finding comes from a review by the Cochrane Collaboration, a not-for-profit group that evaluates medical research. The use of depression pills to treat back pain has been controversial. Some studies have suggested a benefit while others have shown the drugs don’t help. Complicating matters is the fact that depression is common among sufferers of chronic back pain, so it’s not always clear if doctors are prescribing the drugs for pain relief or as a preventative measure against depression.

The Cochrane review, led by Donna Urquhart, a research fellow at Monash University in Melbourne, Australia, analyzed 10 published studies that compared antidepressants to placebos in patients with low back pain. Some of the patients had ruptured discs, slipped vertebrae, pinched nerves or other problems; some were depressed, while others were free of depression.

Most of the studies found that patients receiving antidepressants didn’t experience any more pain relief than those taking a placebo, although some of the research suggested a benefit. Overall, the analysis concluded that there’s no evidence that prescribing antidepressants to treat back pain relieves pain or improves function. The researchers also found that in patients with low back pain, antidepressant treatment didn’t curb depression, either.

Most of the studies looked at an older class of drugs called tricyclic antidepressants, although a few studies included some of the newer generation antidepressants, including the drugs Wellbutrin and Paxil.

The data are surprising because last fall The Annals of Internal Medicine published a review showing antidepressants did appear to relieve back pain. The discrepancy may be due to different ways of measuring pain relief in each review. However, Cochrane reviews are among the most respected in medicine.

A 2000 survey in The Archives of Family Medicine showed that doctors commonly prescribe antidepressants to patients with back pain. Back pain sufferers who are using antidepressants shouldn’t quit the drugs as a result of the report without talking to their doctors first. Quitting antidepressants cold turkey can be risky, triggering a series of side effects. And patients with a history of depression likely will be advised to continue treatment with the drugs.

“Existing studies do not provide adequate evidence for or against the use of antidepressants in low back pain, and further research is needed,” Dr. Urquhart told the Health Behavior News Service. “In the meantime, antidepressants should be regarded as an unproven treatment for nonspecific low back pain.”

Drug-Free Remedies for Chronic Pain

By Loolwa Khazzoom : AARP Magazine Article

In the early 1980s Cynthia Toussaint was a promising young dancer, close to snagging a role in the hit TV series Fame. But then she tore a hamstring in ballet class. Usually such tears heal on their own, but in Toussaint’s case the injury led to the development of complex regional pain syndrome—a little-understood disease characterized by chronic pain that spreads throughout the body and can be so excruciating that even the touch of clothing hurts.

“It felt like I had been doused with gasoline and lit on fire,” recalls Toussaint, now 48, who was a student at the University of California, Irvine. “I can’t imagine surviving something more devastating.”

Toussaint had become one of the many Americans suffering from chronic pain—as many as 76 million, according to the American Pain Foundation—who are dealing with everything from arthritis to cancer. And like many pain patients, she struggled to convince doctors her symptoms were real. Toussaint says she was refused X-rays, misdiagnosed, and dismissed as crazy. “One doctor patted me on the head, saying, ‘You’re making a mountain out of a molehill, darling. You need to see a psychologist,’” she recalls. Meanwhile her disease—often reversible if treated early—only got worse.

Online Extra...

Resources for Advocacy and Information

When you’re in pain, don’t go it alone. These online professional, holistic, and support groups can help

Academy for Guided Imagery This association provides referrals to practitioners of and resources about this visualizing technique.

American Academy of Pain Management You can find specialists, accredited programs, and information on pain management on the website of this interdisciplinary nonprofit group, which assists “clinicians who treat people with pain through education, setting standards of care, and advocacy”; the site offers a directory of specialists, a list of accredited programs, and information on coping with pain.

American Academy of Pain Medicine A medical association, it focuses on education, advocacy, and research to promote the best care for patients; it helps locate specialists in your area and provides general information about pain (847-375-4731).

American Chronic Pain Association Do you want to join or start a support group? The ACPA has plenty of them in the United States, as well as Canada, Great Britain, and other countries (800-533-3231).

American Holistic Health Association This nonprofit serves as “a neutral clearing house” for pain patients, providing guidance through the maze of conventional and alternative medicine. Resources on its website include self-help tools; free health-book catalogs; and health-related books, CDs, and DVDs (714-779-6152).

American Pain Society A multidisciplinary organization for practicing physicians and other scientific professionals, APS also offers resources and publications for pain sufferers (847-375-4715).

ChronicBabe This website is primarily targeted to young women with chronic illnesses, but its articles and resources are relevant to anyone with chronic pain.

For Grace Cynthia Toussaint’s nonprofit works to ensure the ethical and equal treatment of women in chronic pain, through self-empowerment, public awareness, health-care-practitioner education, and legislative advocacy.

The Healing Mind This center offers articles, books, CDs, and public workshops on mind/body medicine treatments for numerous health conditions; the website features a blog by Martin Rossman, M.D., and other health experts.

National Pain Foundation Pain sufferers and their families can find a wide range of resources regarding treatment options, as well as peer-reviewed information; representatives are available to answer questions three days a week by e-mail, and the website offers physician referrals and an online support community.

--Ron Jones and Loolwa Khazzoom

Bedridden and folded up in a fetal position, she was unable to brush her hair, shower, or use the bathroom unaided. She teetered on the verge of suicide. Finally, after 15 years, a switch in medical plans introduced her to doctors who believed her. But by that point, the pain medications they prescribed could not reverse her condition. Worse, the drugs left her with a slew of side effects.

Toussaint wanted to try physical therapy for pelvic pain, and a movement therapy called Feldenkrais, ideas her doctor initially dismissed. “He rolled his eyes and said, ‘It’ll never help,’” she remembers. Ultimately, however, the move led her into the world of alternative therapies—and saved Toussaint’s life.

When she first began working with a physical therapist, Toussaint was so sensitive that the slightest touch caused her intense pain. So the therapist, sitting at Toussaint’s bedside, used guided imagery, a deep-relaxation method scientifically proven to reduce pain levels.

In guided imagery, a therapist helps a patient imagine herself in a calming place. Many patients visualize going to the beach or the mountains. Toussaint conjured up a make-believe ballet class, where week after week the therapist followed Toussaint’s verbal cues to guide her through elaborate combinations that she “danced” in her head.

Her body quickly began unfolding. Within one month of starting the three-times-a-week guided-imagery sessions, she could sit up, walk around her condominium, and shower without help. Perhaps most significantly, she was able to receive hands-on physical therapy, which further reduced her pain. She later cofounded For Grace, a nonprofit that helps women with chronic pain.

How is it possible that simply by engaging her imagination, Toussaint began healing her pain? New advances in neuroscience shed light on the process, says Martin Rossman, M.D., author of Guided Imagery for Self-Healing (New World Library, 2000). “While acute pain appears in areas of the brain that are connected to tissue damage, chronic pain lives in other areas of the brain—the prefrontal cortex and limbic system, which the brain uses for memories, especially emotional ones,” Rossman says. In some cases “the pain lives on long past the time when the body tissues have healed.”

Repeated thoughts and emotions create nerve pathways in the brain. Chronic pain impulses travel along well-worn pathways. By using techniques such as guided imagery to build new nerve pathways, “the pain pathways can become less active,” Rossman says.

Guided imagery and Feldenkrais, the therapies that helped Toussaint, are only two out of more than a dozen alternative therapies that have been scientifically documented to ease chronic pain when drugs can’t. And they frequently can’t, says James Dillard, M.D., D.C., coauthor of The Chronic Pain Solution (Bantam, 2003). “Even if we prescribe medication as well as we can, on average we are still only going to take away between 50 and 60 percent of your pain.”

This is not to say that drugs have no place in pain treatment. Experts agree that medication is a necessary and sometimes lifesaving part of the pain-management equation. “People need to function in their lives,” says David Simon, M.D., cofounder, CEO, and medical director of the Chopra Center for Wellbeing in Carlsbad, California. “There’s clearly a role for appropriate pharmaceuticals.”

The latest trend, says Steven Stanos, D.O., medical director of the Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago Center for Pain Management, is to take a more comprehensive approach to treating chronic pain, a “bio-psycho-social approach.” The “bio,” or biological, part means treating the physical or underlying pathology—and, where possible, its root cause. The “psycho,” or psychological, part addresses the depression, fear, and anxiety that can accompany and even exacerbate the experience of chronic pain. The “social” part pertains to a patient’s ability to function, work, sustain friendships, and maintain status in society.

If a clinician ignores any of the biological, psychological, or social impacts of chronic pain, Stanos says, “it may become a struggle to successfully treat patients.”

Very few doctors have specialized training in pain management. In fact, only 3 percent of U.S. medical schools offer a separate course in it. So if you suffer from chronic pain, you’re probably going to have to become an expert yourself. “I think the person with pain should see it as a journey,” advises Simon. “They have to be the captain of that ship.”

That proposition can feel daunting enough when you’re well and helping a family member through a difficult diagnosis. But when you are the one in pain, managing your case yourself may be an overwhelming challenge. That’s why Mary Pat Aardrup, senior vice president of the National Pain Foundation, recommends enlisting a friend or family member as an advocate—someone who can help research treatment options and interview both conventional and alternative health care practitioners.

Make sure the practitioners you find are willing to work together. When everybody shares information, you’re more likely to get the most accurate diagnosis and best care. Curing the root cause may resolve the problem—as in the case of Lyme disease. But “assuming that you have a disorder for which there’s no easy medical fix,” advises Simon, “begin a process of trying to relieve yourself of that pain, starting with the most noninvasive and then gradually working your way into more invasive approaches.” If a therapy doesn’t offer relief within a few weeks, experts say, try something else.

When choosing therapies to try, “it’s important to think critically,” says journalist Paula Kamen, who wrote All in My Head (Da Capo Press, 2006), about her quest for relief from chronic daily headache. “There is so much desperation that makes us vulnerable as chronic-pain patients.” Be wary of anyone who promises to cure any problem, she says. Also, understand any risks before you participate. And remember, you can quit at any time—even in the middle of a session—if something doesn’t feel right.

Check out the chart below to learn about alternative therapies that have been shown to help relieve chronic pain. Informing yourself could be your first step on the path to a pain-free life.

Alternative Treatments That Work on Pain

Research shows these therapies can ease discomfort. For more information visit the website of the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine.

TYPE

WHAT THEY HELP

HOW THEY WORK

EXAMPLES

Movement-Based Therapies:

Physical exercises and practices

Musculoskeletal pain, joint pain, and lower-back pain

By strengthening muscles supporting joints, improving alignment, and releasing endorphins

• Physical therapy: Specialized movements to strengthen weak

areas of the body, often through resistance training

• Yoga: An Indian practice of meditative stretching and posing

• Pilates: A resistance regimen that strengthens core muscles

• Tai chi: A slow, flowing Chinese practice that improves balance

• Feldenkrais: A therapy that builds efficiency of movement

Nutritional and Herbal Remedies:

Food choices and dietary supplements (ask your doc before using supplements)

All chronic pain but especially abdominal discomfort, headaches, and inflammatory conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis

By boosting the body’s natural immunity, reducing pain-causing inflammation, soothing pain, and decreasing insomnia

• Anti-inflammatory diet: A Mediterranean eating pattern high in whole grains, fresh fruits, leafy vegetables, fish, and olive oil

• Omega-3 fatty acids: Nutrients abundant in fish oil and flaxseed that reduce inflammation in the body

• Ginger: A root that inhibits pain-causing molecules

• Turmeric: A spice that reduces inflammation

• MSM: Methylsulfonylmethane, a naturally occurring nutrient that helps build bone and cartilage

Mind-Body Medicine:

Using the powers of the mind to produce changes in the body

All types of chronic pain

By reducing stressful (and, hence, pain-inducing) emotions such as panic and fear, and by refocusing attention on subjects other than pain

• Meditation: Focusing the mind on something specific (such as breathing or repeating a word or phrase) to quiet it

• Guided imagery: Visualizing a particular outcome or scenario with the goal of mentally changing one’s physical reality

• Biofeedback: With a special machine, becoming alert to body processes, such as muscle tightening, to learn to control them

• Relaxation: Releasing tension in the body through exercises such as controlled breathing

Energy Healing:

Manipulating the electrical energy—called chi in Chinese medicine—emitted by the body’s nervous system

Pain that lingers after an injury heals, as well as pain complicated by trauma, anxiety, or depression

By relaxing the body and the mind, distracting the nervous system, producing natural painkillers, activating natural pleasure centers, and manipulating chi

• Acupuncture: The insertion of hair-thin needles into points along the body’s meridians, or energetic pathways, to stimulate the flow of energy throughout the body; proven helpful for post-surgical pain and dental pain, among other types

• Acupressure: Finger pressure applied to points along the meridians, to balance and increase the flow of energy

• Chigong: Very slow, gentle physical movements, similar to tai chi, that cleanse the body and circulate chi

• Reiki: Moving a practitioner’s hands over the energy fields of the client’s body to increase energy flow and restore balance

Physical Manipulation:

Hands-on massage or movement of painful areas

Musculoskeletal pain, especially lower-back and neck pain; pain from muscle underuse or overuse; and pain from adhesions or scars

By restoring mobility, improving circulation, decreasing blood pressure, and relieving stress

• Massage: The manipulation of tissue to relax clumps of knotted muscle fiber, increase circulation, and release patterns of chronic tension

• Chiropractic: Physically moving vertebrae or other joints into proper alignment, to relieve stress

• Osteopathy: Realigning vertebrae, ribs, and other joints, as with chiropractic; osteopaths have training equivalent to that of medical doctors

Lifestyle Changes:

Developing healthy habits at home and work

All types of chronic pain

By strengthening the immune system and enhancing well-being, and by reframing one’s relationship to (and, thus, experience of) chronic pain

• Sleep hygiene: Creating an optimal sleep environment to get deep, restorative rest; strategies include establishing a regular sleep-and-wake schedule and minimizing light and noise.

• Positive work environment: Having a comfortable workspace and control over one’s activities to reduce stress and contribute to the sense of mastery over pain.

• Healthy relationships: Nurturing honest and supportive friendships and family ties to ease anxiety that exacerbate pain.

• Exercise: Regular activity to build strength and lower stress

Best Treatment for TMJ May Be Nothing

By Jane E. Brody : NY Times Article : February 3, 2009

One person gets migraine headaches, another ringing in the ears, a third clicking and locking of the jaw, a fourth pain on the sides and back of the head and neck. All are suspected of having a temporomandibular disorder.

Up to three-fourths of Americans have one or more signs of a temporomandibular problem, most of which come and go and finally disappear on their own. Specialists from Boston estimate that only 5 percent to 10 percent of people with symptoms need treatment.

Popularly called TMJ, for the joint where the upper and lower jaws meet, temporomandibular disorders actually represent a wider class of head pain problems that can involve this pesky joint, the muscles involved in chewing, and related head and neck muscles and bones.

But too often, experts say, patients fail to have the problem examined in a comprehensive way and undergo costly and sometimes irreversible therapies that may do little or nothing to relieve their symptoms. As scientists at the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research wrote recently, “Less is often best in treating TMJ disorders.”

A New Understanding

The TMJ is a complicated joint that connects the lower jaw to the temporal bone at the side of the head. It has both a hinge and a sliding motion. When the mouth is opening, the rounded ends, or condyles, of the lower jaw glide along the sockets of the temporal bones. Muscles are connected to both the jaw and the temporal bones, and a soft disc between them absorbs shocks to the jaw from chewing and other jaw movements.

TMJ problems were originally thought to stem from dental malocclusion — upper and lower teeth misalignment — and improper jaw position. That prompted a focus on replacing missing teeth and fitting patients with braces to realign their teeth and change how the jaws come together.

But later studies revealed that malocclusion itself was an infrequent cause of facial pain and other temporomandibular symptoms. Rather, as the Boston specialists wrote recently in The New England Journal of Medicine “the cause is now considered multifactorial, with biologic, behavioral, environmental, social, emotional and cognitive factors, alone or in combination, contributing to the development of signs and symptoms of temporomandibular disorders.”

According to the American Academy of Orofacial Pain, the disorder “usually involves more than one symptom and rarely has a single cause.”

Among the “mechanical” causes that are now recognized as distorting the function of the TMJ are congenital or developmental abnormalities of the jaw; displacement of the disc between the jaw bones; inflammation or arthritis that causes the joint to degenerate; traumatic injury to the joint (sometimes just from opening the mouth too wide); tumors; infection; and excessive laxity or tightness of the joint.

But the most common TMJ problem is known as myofacial pain disorder, a neuromuscular problem of the chewing muscles characterized by a dull, aching pain in and around the ear that may radiate to the side or back of the head or down the neck. Someone with this disorder may have tender jaw muscles, hear clicking or popping noises in the jaw, or have difficulty opening or closing the mouth. Simple acts like chewing, talking excessively or yawning can make the symptoms worse.

Jaw-irritating habits, like clenching the teeth or jaw, tooth grinding at night, biting the lips or fingernails, chewing gum or chewing on a pencil, can make the problem worse or longer lasting. Psychological factors also often play a role, especially depression, anxiety or stress.

Proper Assessment

The overwhelming majority of people with TMJ symptoms are women. Women represent up to 90 percent of patients who seek treatment, Dr. Leonard B. Kaban, chief of oral and maxillofacial surgery at the Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, said in an interview. Most patients are middle-age adults, he and two dental specialists, Dr. Steven J. Scrivani and Dr. David A. Keith, wrote in the journal article.

Dr. Kaban urged patients to obtain a thorough assessment of the problem before choosing therapy, especially if they have symptoms like tinnitus (ringing in the ears) and migraine headaches.

He said doctors and dentists should “start with a thorough history — you can get 80 to 90 percent of the needed information just from talking to the patient about their habits.” This should be followed by a physical examination, checking for signs like muscle tenderness and pain in the jaw, limited jaw opening and noises.

“Among the biggest advances in diagnosis has been imaging studies, especially by M.R.I. and occasionally by CT scan with a cone-beam image,” Dr. Kaban said.

For those with complicated problems, he suggested visiting a multidisciplinary temporomandibular clinic, found at many leading hospitals and dental schools.

Therapy Options

Resting the jaw is the most important therapy. Stop harmful chewing and biting habits, avoid opening your mouth wide while yawning or laughing (holding a fist under the chin helps), and temporarily eat only soft foods like yogurt, soup, fish, cottage cheese and well-cooked, mashed or pureed vegetables and fruit. It also helps to apply heat to the side of the face and to take a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medication, for up to two weeks.

Other self-care measures suggested by the orofacial academy include not leaning on or sleeping on the jaw and not playing wind, grass or string instruments that stress, strain or thrust back the jaw.

Physical therapy to retrain positioning of the spine, head, jaw and tongue can be helpful, as can heat treatments with ultrasound and short-wave diathermy.

Some patients are helped by a low-dose tricyclic antidepressant taken at bedtime, or antianxiety medication. Stress management and relaxation techniques like massage, yoga, biofeedback, cognitive therapy and counseling to achieve a less frenetic work pace are also helpful, according to the findings of a national conference on pain management.

If you clench or grind your teeth, you can be fitted with a mouth guard that is inserted like a retainer or removable denture, especially at night, to prevent this joint-damaging behavior.

But Dr. Kaban cautioned against embarking on “any expensive, irreversible treatment” before a thorough diagnosis is completed and simple, reversible therapies have been tried and found wanting.

As with other joints, he said, surgery is a treatment of last resort, when medical management has proved ineffective. As he and his colleagues wrote, surgery is primarily for patients who are born with or develop jaw malformations and patients with arthritis who have loose fragments of bone or require condyle reshaping.

By Jane E. Brody : NY Times Article : November 6, 2007

Pain, especially pain that doesn’t quit, changes a person. And rarely for the better. The initial reaction to serious pain is usually fear (what is wrong with me, and is it curable?), but pain that fails to respond to treatment leads to anxiety, depression, anger and irritability.

At age 29, Walter, a computer programmer in Silicon Valley, developed a repetitive stress injury that caused severe pain in his hands when he touched the keyboard. The injury did not respond to rest. The pain became worse, spreading to his shoulders, neck and back.

Unable to work, lift, carry or squeeze anything without enduring days of crippling pain, Walter could no longer drive, open a jar or even sign his name.

“At age 29, I was on Social Security disability, basically confined to home, and my life seemed to be over,” Walter recalls in “Living With Chronic Pain,” by Dr. Jennifer Schneider. Severely depressed, he wonders whether his life is worth living.

Yet, despite his limited mobility and the pain-induced frown lines in his face, to look at Walter is to see a strapping, healthy young man. It is hard to tell that he, or any other person beset with chronic pain, is suffering as much as he says he is.

Pain is an invisible, subjective symptom. The body of a chronic pain sufferer — someone with fibromyalgia, for example, or back pain — usually appears intact. There are no objective tests to detect pain or measure its intensity. You just have to take a person’s word for it.

Nearly 10 percent of people in the United States suffer from moderate to severe chronic pain, and the prevalence increases with age. Complete relief from chronic pain is rare even with the best treatment, which is itself a rarity. Doctors and patients alike, who misunderstand the effects of narcotics, are too often reluctant to use drugs like opioids, which can relieve acute, as well as chronic, pain and may head off the development of a chronic pain syndrome.

Why Pain Persists

The problems with chronic pain are that it never really ends and does not always respond to treatment. If the pain initially was caused by an injury or illness, it can persist long after the injury has healed or the illness defeated because permanent changes have occurred in the body.

Mark Grant, a psychologist in Australia who specializes in managing chronic pain, says the notion that “physical injury equals pain” is overly simplistic. “We now know that pain is caused and maintained by a combination of physical, psychological and neurological factors,” Mr. Grant writes on his Web site, www.overcomingpain.com. With chronic pain, a persistent physical cause often cannot be determined.

“Chronic pain can be caused by muscle tension, changes in circulation, postural imbalances, psychological distress and neurological changes,” Mr. Grant says on his site. “It is also known that unrelieved pain is associated with increased metabolic rate, spontaneous excitation of the central nervous system, changes in blood circulation to the brain and changes in the limbic-hypothalamic system,” the region of the brain that regulates emotions.

Dr. Schneider, the author of “Living With Chronic Pain” (Healthy Living Books, Hatherleigh Press, 2004), is a specialist in pain management in Tucson, Ariz. In her book, she points out that the nervous system is responsible for the two major types of chronic pain.

One, called nociceptive pain, “arises from injury to muscles, tendons and ligaments or in the internal organs,” she writes. Undamaged nerve cells responding to an injury outside themselves transmit pain signals to the spinal cord and then to the brain. The resulting pain is usually described as deep and throbbing. Examples include chronic low back pain, osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, fibromyalgia, headaches, interstitial cystitis and chronic pelvic pain.

The second type, neuropathic pain, “results from abnormal nerve function or direct damage to a nerve.” Among the causes are shingles, diabetic neuropathy, reflex sympathetic dystrophy, phantom limb pain, radiculopathy, spinal stenosis, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, stroke and spinal cord injury.

The damaged nerve fibers “can fire spontaneously, both at the site of the injury and at other places along the nerve pathway” and “can continue indefinitely even after the source of the injury has stopped sending pain messages,” Dr. Schneider writes.

“Neuropathic pain can be constant or intermittent, burning, aching, shooting or stabbing, and it sometimes radiates down the arms or legs,” she adds. This kind of pain tends “to involve exaggerated responses to painful stimuli, spread of pain to areas that were not initially painful, and sensations of pain in response to normally nonpainful stimuli such as light touch.” It is often worse at night and may involve abnormal sensations like tingling, pins and needles, and intense itching.

Some chronic pain syndromes involve both nociceptive and neuropathic pain. A common example is sciatica; a pinched nerve causes back pain that radiates down the leg. In some cases, the pain of sciatica is not felt in the back but only in the leg, making the cause difficult to diagnose without an M.R.I.

Beyond Physical Problems

The consequences of chronic pain typically extend well beyond the discomfort from the sensation of pain itself. Dr. Schneider lists these potential physical effects: poor wound healing, weakness and muscle breakdown, decreased movement that can lead to blood clots, shallow breathing and suppressed coughing that raise the risk of pneumonia, sodium and water retention in the kidneys, raised heart rate and blood pressure, weakened immune system, a slowing of gastrointestinal motility, difficulty sleeping, loss of appetite and weight, and fatigue.

But that is hardly the end of it. The psychological and social consequences of chronic pain can be enormous. Unremitting pain can rob a person of the ability to enjoy life, maintain important relationships, fulfill spousal and parental responsibilities, perform well at a job or work at all.

The economic burdens can be severe, especially when the patient is the primary breadwinner or holds a job that provides the family’s health insurance. Only about half of patients with chronic pain “who undergo comprehensive multidisciplinary pain rehabilitation are able to return to work,” Dr. Schneider reports.

As for the notion that chronic pain patients are often malingering — seeking attention and escape from responsibilities — pain specialists say that is nonsense. No one in his right mind — and most patients were in their right minds before the pain began — would trade a fulfilling life for the misery of chronic pain.

Chronic Pain: A Burden Often Shared

By Jane E. Brody : NY Times Article : November 13,2007

Chronic pain is a family problem. When people experience unrelenting pain, everyone they live with and love is likely to suffer. The frustration, anxiety, stress and depression that often go with chronic pain can also afflict family members and friends who feel helpless to provide relief.

Healthy family members are often overworked from assuming the duties of the person in pain. They have little time and energy for friends and other diversions, and they may fret over how to make ends meet when expenses rise and family incomes shrink.

It is easy to see how tempers can flare at the slightest provocation. The combination of unrelieved suffering on the one hand and constant stress and fatigue on the other can be highly volatile, even among the most loving couples — whose burdens are often worsened by a decline of intimacy.

“Family members are rarely considered by doctors who treat pain,” said Dennis C. Turk, a pain management researcher at the University of Washington in Seattle. “Yet a study we did found that family members were up to four times more depressed than the patients.”

But pain experts say there is much that family members and friends can do to improve the situation.

Step one is to recognize that chronic pain is not an individual problem. Let the patient know that you are in this together and will fight it together. When the patient is moody and irritable, try not to take it personally.

Step two involves learning as much as you can about the condition and how to treat it. Eliminating the pain may not be possible, but there often ways to reduce it. (See next week’s column on treating chronic pain.)

Some of the ideas below were adapted from the American Chronic Pain Association’s Family Manual, written by Penney Cowan, the association’s founder and executive director.

“Twenty-five percent of the calls we get are from family members looking for help,” Ms. Cowan said in an interview last week. “Family members are just as isolated, controlled, frustrated, guilt-ridden and confused by chronic pain as is the person in pain.”

Acknowledge your feelings. You may feel guilty about not being able to relieve the distress of someone you love. You may be anxious about financial problems.

You may be distressed by the reactions of other people, who might lack an understanding of chronic pain and suggest that the patient is malingering — faking the pain to avoid work or family responsibilities. At a time when you most need the understanding and support of others, they may seem unsympathetic, even hostile.

But the most common reaction is resentment, over a withdrawal of the patient’s affection and sexual intimacy, the unending care required by the patient, the need to add the patient’s responsibilities to your own, the decline or loss of a social life and time spent with friends. You may resent having to abandon an enjoyable lifestyle or plans for the future.

If the patient was the family breadwinner and is now unable to work, you may have to find a job and, at the same time, do most or all of the chores at home and care for the patient. Chronic exhaustion can erode your temper as well as your own health.

It is all too easy to react to such feelings in emotionally destructive ways. Owning up to them can help you cope more successfully.

Help the patient stay involved. Chronic pain can rob people of their abilities and force them to be cared for by others, leaving them to feel worthless and guilty over not contributing to the family’s welfare. Whether you are the patient’s primary or intermittent caregiver, it is important not to contribute to feelings of helplessness.

Encourage patients to participate as fully as possible in family plans and activities, household chores, discussions and decisions. Perhaps they can no longer do yardwork, but they may still be able to help with cooking, setting the table, washing the dishes, caring for children, handling family finances, making phone calls or shopping by phone. Feeling useful can bolster a patient’s self-esteem and mood.

“For each action the pain person says he or she can no longer do, point out something he or she can do,” the pain association’s manual suggests.

Don’t become a go-for. Chronic pain patients should be encouraged to do whatever they can do for themselves. It is important for you to know when to step in and when to step back. Recognize the patient’s abilities and limitations — consider having an evaluation made by an occupational therapist — and let the patient participate as much as possible in daily activities and self-care.

Communicate. “Open, two-way communication is crucial to dealing effectively with chronic pain,” said Dr. Turk, of the University of Washington. “Family members need to know how they can be helpful and what might be hurtful.”

Failure to communicate honestly and openly can become a cancer on a relationship, be it with a spouse, parent or child. If chronic pain has disrupted family plans, discuss a reordering of priorities. It may be possible to do more than you think.

You have a right to say that you are tired and need to rest, that you need a break from the routine lest you burn out, and that you need to maintain friendships and pursue enjoyable activities outside the home from time to time.

Likewise, the patient has a right and responsibility to express fear, disappointment, guilt and bad feelings about the behavior of some people, as well as gratitude for the help you and others provide.

Ask periodically what the patient might like to discuss with you or do with you. And try not to rise to the bait when the patient is critical or lashes out at you despite all you do. Most often, you are not really the target. But there may be no one else with whom the patient feels safe to express distress.

Take care of yourself. Enlist all the help you can get from family members and friends. Older children can clean the house and prepare meals. Friends and relatives who offer to help can be given tasks that fit their abilities, even if it is just accompanying the patient to a medical appointment. If they haven’t offered, ask.

When necessary, hire others, including neighborhood teenagers, to help out. If you are reluctant to leave the patient home alone, ask a friend or neighbor to stay for a few hours or to look in on the patient every so often so that you can get out for a while.

Don’t neglect your own physical well-being. Eat regular meals, get enough sleep and get regular physical exercise. And be sure to keep up with medical checkups and screening exams. If you get sick, you won’t be much use to the patient in pain.

Many Treatments Can Ease Chronic Pain

By Jane E. Brody : NY Times Article : November 20, 2007

There is one undeniable fact about chronic pain: More often than not, it is untreated or undertreated. In a survey last year by the American Pain Society, only 55 percent of all patients with noncancer-related pain and fewer than 40 percent with severe pain said their pain was under control.

But it does not have to be this way. There are myriad treatments — drugs, devices and alternative techniques — that can greatly ease persistent pain, if not eliminate it.

Chronic pain is second only to respiratory infections as a reason patients seek medical care. Yet because physicians often do not take a patient’s pain seriously or treat it adequately, nearly half of chronic-pain patients have changed doctors at least once, and more than a quarter have changed doctors at least three times.

In an ideal world, every such patient would be treated by a pain specialist familiar with the techniques for alleviating pain. But “very few patients with chronic disabling pain have access to a pain specialist,” a team of experts wrote in a supplement to Practical Pain Management in September.

As a result, most patients have to rely on primary care physicians for pain treatment, obliging them to learn as much as they can about treatment approaches and to persist in their search for relief.

Medications

Most chronic pain patients end up taking a cocktail of pills that complement one another.

These are three categories of drugs useful for treating chronic pain:

- If the pain is not severe, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, Nsaids for short, are often tried first. Some, like ibuprofen and naproxen, are sold over the counter. Others, like diclofenac (Voltaren) and celecoxib (Celebrex), are available by prescription. All have risks, especially to the heart and gastrointestinal tract, and may be inappropriate for those prone to a heart attack, stroke or ulcers. Nsaids must not be combined with one another or any aspirinlike drug, but they can be used safely with acetaminophen (Tylenol).

- Several classes of drugs originally marketed for other uses are now part of the pain control armamentarium — antidepressants, especially the S.N.R.I.’s like venlafaxine (Effexor) and duloxetine (Cymbalta); antiepileptics like gabapentin (Neurontin) and pregabalin (Lyrica); and muscle relaxants like baclofen (Lioresal) and dantrolene sodium (Dantrium). These are often used in combination with specific pain-relieving drugs.

- By far the most important class of drugs for moderate to severe chronic pain are the opioids: morphine and morphinelike drugs. Patients often reject them for fear of becoming addicted, a rare event when they are used to treat pain. Doctors often avoid prescribing them for fear of addicting patients, being duped by drug abusers or being raided by the Justice Department. Pain societies have established clear-cut guidelines to help doctors avoid such risks, including ways to identify patients who could become addicted.

For patients with chronic, continuous pain, using a slowly released opioid like oxycodone (Oxycontin), morphine or fentanyl (administered through a skin patch or lozenge on a stick) is preferred. These drugs minimize or eliminate the hills and valleys of pain and reduce the medication patients need.

The usual side effects — sedation, nausea, confusion — soon disappear except for constipation, which can be treated.

Pain specialists also recommend that patients taking slow-release opioids have on hand a fast-acting one like Percocet (oxycodone with acetaminophen) to treat breakthrough pain.

Methadone, a synthetic opioid, is another option for managing chronic pain, especially neuropathic pain, but it has to be taken several times a day. It is metabolized in the liver, along with other drugs that can affect blood levels of methadone.

Other Remedies

- Some patients in chronic pain use a technique called TENS, for transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, in which pulses of low-intensity electric current are applied to the skin. The theory is that the pulses transmit signals to the brain that compete with the pain signals. Unlike drugs, TENS has no side effects or interaction with drugs, and it can be used at home.

- Acupuncture, another increasingly popular treatment for persistent as well as intermittent pain, is thought to work by increasing the release of endorphins, chemicals that block pain signals from reaching the brain. It may be effective in relieving headaches, facial and low back pain, and pain caused by shingles, arthritis and spastic colon.

- Guided imagery, meditation, relaxation therapy and hypnosis or hypnotherapy are often useful adjuncts to pain treatment, because they can reduce stress and take one’s mind off the pain. Likewise, cognitive behavioral (“talk”) therapy can help patients think and behave differently with respect to their pain. Other options include massage and hydrotherapy, the use of hot or cold water to reduce inflammation and promote healing.

- Many chronic pain patients can benefit from physical therapy and exercises to strengthen weak supporting muscles and relax tight joints (which for the last two years has helped me control sciatic pain), or occupational therapy to learn new ways of moving, sitting and lying down to reduce irritation of or dependence on painful body parts.

- Finally, a mental adjustment may be necessary to improve the quality of life of chronic pain patients, who have to accept that they may always have some degree of pain. Chronic pain tends not to go away, and changes may have to be made both at work and at play. The goals should be to reduce pain to an acceptable level and to learn how not to make it worse.

Here are some groups that can provide information on managing chronic pain:

- AMERICAN CHRONIC PAIN ASSOCIATION E-mail: [email protected]; Web site: www.theacpa.org. P.O. Box 850, Rocklin, Calif., 95677-0850; (916) 632-0922 or (800) 533-3231.

- AMERICAN PAIN FOUNDATION [email protected]; www.painfoundation.org. 201 North Charles Street, Suite 710, Baltimore, Md., 21201-4111; (888) 615-7246.

- NATIONAL FOUNDATION FOR THE TREATMENT OF PAIN [email protected]; www.paincare.org. P.O. Box 70045, Houston, Tex., 77270; (713) 862-9332.

Rewiring the Brain to Ease Pain

Brain Scans Fuel Efforts to Teach Patients How to Short-Circuit Hurtful Signals

By Melinda Beck : WSJ; November 15, 2011

How you think about pain can have a major impact on how it feels.

That's the intriguing conclusion neuroscientists are reaching as scanning technologies let them see how the brain processes pain.

That's also the principle behind many mind-body approaches to chronic pain that are proving surprisingly effective in clinical trials.