- RETIREMENT ANNOUNCEMENT

- HOME PAGE

- "MYCHART" the new patient portal

- BELMONT MEDICAL ASSOCIATES

- MOUNT AUBURN HOSPITAL

- EMERGENCIES

- PRACTICE PHILOSOPHY

- MY RESUME

- TELEMEDICINE CONSULTATION

- CONTACT ME

- LAB RESULTS

- ePRESCRIPTIONS

- eREFERRALS

- RECORD RELEASE

- MEDICAL SCRIBE

- PHYSICIAN ASSISTANT (PA)

- Medicare Annual Wellness Visit

- Case management/Social work

- Quality Care Measures

- Emergency closing notice

- FEEDBACK

- Talking to your doctor

- Choosing..... and losing a doctor

- INDEX A - Z

- ALLERGIC REACTIONS

- Alternative Medicine

- Alzheimer's Disease

- Bladder Problems

- Blood disorders

- Cancer Concerns

- GENETIC TESTING FOR HEREDITARY CANCER

- Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

- Controversial Concerns

- CPR : Learn and save a life

- CRP : Inflammatory marker

- Diabetes Management

- Dizziness, Vertigo,Tinnitus and Hearing Loss

- EXERCISE

- FEMALE HEALTH

-

GASTROINTESTINAL topics

- Appendicitis

- BRAT diet

- Celiac Disease or Sprue

- Crohn's Disease

- Gastroenterologists for Colon Cancer Screening

- Colonoscopy PREP

- Constipation

- Gluten sensitivity, but not celiac disease

- Heartburn and GERD

- Hemorrhoids and Anal fissure

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- NASH : Non Alcoholic Steato Hepatitis

- FEET PROBLEMS

- HEART RELATED topics

-

INFECTIOUS DISEASES

- Antibiotic Resistance

- Cat bites >

- Clostridia difficile infection - the "antibiotic associated germ"

- CORONA VIRUS

- Dengue Fever and Chikungunya Fever

- Food borne illnesses

- Shingles Vaccine

- Hepatitis B

- Hepatitis C

- Herpes

- Influenza

- Helicobacter pylori - the "ulcer germ"

- HIV Screening

- Lyme and other tick borne diseases

- Measles

- Meningitis

- MRSA (Staph infection)

- Norovirus

- Sexually Transmitted Diseases

- Shingles (Herpes Zoster)

- Sinusitis

- West Nile Virus

- Whooping Cough (Pertussis)

- Zika virus and pregnancy

- INSURANCE related topics

- KIDNEY STONES

- LEG CRAMPS

- LIBRARY for patients

- LIFE DECISIONS

- MALE HEALTH

- Medication/Drug side effects

- MEDICAL MARIJUANA

- MENTAL HEALTH

- Miscellaneous Articles

-

NUTRITION - EXERCISE - WEIGHT

- Cholesterol : New guidelines for treatment

- Advice to lower your cholesterol

- Cholesterol : Control

- Cholesterol : Raising your HDL Level

- Exercise

- Food : Making Smart Choices

- Food : Making Poor Choices

- Food : Grape Fruit and Drug Interaction

- Food : Vitamins, Minerals and Supplements

- Omega 3 fatty acids

- Vitamin B12 deficiency

- Vitamin D

- Weight Loss

- ORTHOPEDICS

- PAIN

- PATIENTS' RIGHTS

- SKIN

- SLEEP

- SMOKING

- STROKE

- THYROID

- SUBSTANCE ABUSE

- Travel and Vaccination

- TREMOR

- Warfarin Anticoagulation

- OTHER STUFF FOLLOWS

- Fact or Opinion?

- Hippocratic Oath

- FREE ADVICE.......for what its worth!

- LAUGHTER.....is the best medicine

- Physicians Pet Peeves

- PHOTO ALBUM - its not all work!

- Cape Town, South Africa

- Tribute page

- The 100 Club

- Free Wi-Fi

NUTRITION, EXERCISE AND WEIGHT RELATED TOPICS

In its fourth annual ranking, U.S. News & World Report assembled a panel of nutritionists and health experts to review 38 currently trending diets, from well-known contenders such as Weight Watchers to the more recently trending Paleo Diet. After the review, the panelists ranked 32 of them into eight corresponding categories:

1. Best Diets Overall

2. Best Commercial Diets

3. Best Weight-Loss Diets

4. Best Diabetes Diets

5. Best Heart-Healthy Diets

6. Best Diets for Healthy Eating

7. Easiest Diets to Follow

8. Best Plant-Based Diets

1. Best Diets Overall

2. Best Commercial Diets

3. Best Weight-Loss Diets

4. Best Diabetes Diets

5. Best Heart-Healthy Diets

6. Best Diets for Healthy Eating

7. Easiest Diets to Follow

8. Best Plant-Based Diets

Mediterranean Diet Is Shown to Ward Off Heart Risks

By Gina Kolata : NY Times : February 25, 2013

About 30 percent of heart attacks, strokes and deaths from heart disease can be prevented in people at high risk if they switch to a Mediterranean diet rich in olive oil, nuts, beans, fish, fruits and vegetables, and even drink wine with meals, a large and rigorous new study has found.

The findings, published on The New England Journal of Medicine’s Web site on Monday, were based on the first major clinical trial to measure the diet’s effect on heart risks. The magnitude of the diet’s benefits startled experts. The study ended early, after almost five years, because the results were so clear it was considered unethical to continue.

The diet helped those following it even though they did not lose weight and most of them were already taking statins, or blood pressure or diabetes drugs to lower their heart disease risk.

“Really impressive,” said Rachel Johnson, a professor of nutrition at the University of Vermont and a spokeswoman for the American Heart Association. “And the really important thing — the coolest thing — is that they used very meaningful endpoints. They did not look at risk factors like cholesterol or hypertension or weight. They looked at heart attacks and strokes and death. At the end of the day, that is what really matters.”

Until now, evidence that the Mediterranean diet reduced the risk of heart disease was weak, based mostly on studies showing that people from Mediterranean countries seemed to have lower rates of heart disease — a pattern that could have been attributed to factors other than diet.

And some experts had been skeptical that the effect of diet could be detected, if it existed at all, because so many people are already taking powerful drugs to reduce heart disease risk, while other experts hesitated to recommend the diet to people who already had weight problems, since oils and nuts have a lot of calories.

Heart disease experts said the study was a triumph because it showed that a diet was powerful in reducing heart disease risk, and it did so using the most rigorous methods. Scientists randomly assigned 7,447 people in Spain who were overweight, were smokers, or had diabetes or other risk factors for heart disease to follow the Mediterranean diet or a low-fat one.

Low-fat diets have not been shown in any rigorous way to be helpful, and they are also very hard for patients to maintain — a reality borne out in the new study, said Dr. Steven E. Nissen, chairman of the department of cardiovascular medicine at the Cleveland Clinic Foundation.

“Now along comes this group and does a gigantic study in Spain that says you can eat a nicely balanced diet with fruits and vegetables and olive oil and lower heart disease by 30 percent,” he said. “And you can actually enjoy life.”

The study, by Dr. Ramon Estruch, a professor of medicine at the University of Barcelona, and his colleagues, was long in the planning. The investigators traveled the world, seeking advice on how best to answer the question of whether a diet alone could make a big difference in heart disease risk. They visited the Harvard School of Public Health several times to consult Dr. Frank M. Sacks, a professor of cardiovascular disease prevention there.

In the end, they decided to randomly assign subjects at high risk of heart disease to three groups. One would be given a low-fat diet and counseled on how to follow it. The other two groups would be counseled to follow a Mediterranean diet. At first the Mediterranean dieters got more intense support. They met regularly with dietitians while members of the low-fat group just got an initial visit to train them in how to adhere to the diet, followed by a leaflet each year on the diet. Then the researchers decided to add more intensive counseling for them, too, but they still had difficulty staying with the diet.

One group assigned to a Mediterranean diet was given extra-virgin olive oil each week and was instructed to use at least 4 four tablespoons a day. The other group got a combination of walnuts, almonds and hazelnuts and was instructed to eat about an ounce of the mix each day. An ounce of walnuts, for example, is about a quarter cup — a generous handful. The mainstays of the diet consisted of at least three servings a day of fruits and at least two servings of vegetables. Participants were to eat fish at least three times a week and legumes, which include beans, peas and lentils, at least three times a week. They were to eat white meat instead of red, and, for those accustomed to drinking, to have at least seven glasses of wine a week with meals.

They were encouraged to avoid commercially made cookies, cakes and pastries and to limit their consumption of dairy products and processed meats.

To assess compliance with the Mediterranean diet, researchers measured levels of a marker in urine of olive oil consumption — hydroxytyrosol — and a blood marker of nut consumption — alpha-linolenic acid.

The participants stayed with the Mediterranean diet, the investigators reported. But those assigned to a low-fat diet did not lower their fat intake very much. So the study wound up comparing the usual modern diet, with its regular consumption of red meat, sodas and commercial baked goods, with a diet that shunned all that.

Dr. Estruch said he thought the effect of the Mediterranean diet was due to the entire package, not just the olive oil or nuts. He did not expect, though, to see such a big effect so soon. “This is actually really surprising to us,” he said.

The researchers were careful to say in their paper that while the diet clearly reduced heart disease for those at high risk for it, more research was needed to establish its benefits for people at low risk. But Dr. Estruch said he expected it would also help people at both high and low risk, and suggested that the best way to use it for protection would be to start in childhood.

Not everyone is convinced, though. Dr. Caldwell Blakeman Esselstyn Jr., the author of the best seller “Prevent and Reverse Heart Disease: The Revolutionary, Scientifically Proven, Nutrition-Based Cure,” who promotes a vegan diet and does not allow olive oil, dismissed the study.

His views and those of another promoter of a very-low-fat diet, Dr. Dean Ornish, president of the nonprofit Preventive Medicine Research Institute, have influenced many to try to become vegan. Former President Bill Clinton, interviewed on CNN, said Dr. Esselstyn’s and Dr. Ornish’s writings helped convince him that he could reverse his heart disease in that way.

Dr. Esselstyn said those in the Mediterranean diet study still had heart attacks and strokes. So, he said, all the study showed was that “the Mediterranean diet and the horrible control diet were able to create disease in people who otherwise did not have it.”

Others hailed the study.

“This group is to be congratulated for carrying out a study that is nearly impossible to do well,” said Dr. Robert H. Eckel, a professor of medicine at the University of Colorado and a past president of the American Heart Association.

As for the researchers, they have changed their own diets and are following a Mediterranean one, Dr. Estruch said.

“We have all learned,” he said.

By Gina Kolata : NY Times : February 25, 2013

About 30 percent of heart attacks, strokes and deaths from heart disease can be prevented in people at high risk if they switch to a Mediterranean diet rich in olive oil, nuts, beans, fish, fruits and vegetables, and even drink wine with meals, a large and rigorous new study has found.

The findings, published on The New England Journal of Medicine’s Web site on Monday, were based on the first major clinical trial to measure the diet’s effect on heart risks. The magnitude of the diet’s benefits startled experts. The study ended early, after almost five years, because the results were so clear it was considered unethical to continue.

The diet helped those following it even though they did not lose weight and most of them were already taking statins, or blood pressure or diabetes drugs to lower their heart disease risk.

“Really impressive,” said Rachel Johnson, a professor of nutrition at the University of Vermont and a spokeswoman for the American Heart Association. “And the really important thing — the coolest thing — is that they used very meaningful endpoints. They did not look at risk factors like cholesterol or hypertension or weight. They looked at heart attacks and strokes and death. At the end of the day, that is what really matters.”

Until now, evidence that the Mediterranean diet reduced the risk of heart disease was weak, based mostly on studies showing that people from Mediterranean countries seemed to have lower rates of heart disease — a pattern that could have been attributed to factors other than diet.

And some experts had been skeptical that the effect of diet could be detected, if it existed at all, because so many people are already taking powerful drugs to reduce heart disease risk, while other experts hesitated to recommend the diet to people who already had weight problems, since oils and nuts have a lot of calories.

Heart disease experts said the study was a triumph because it showed that a diet was powerful in reducing heart disease risk, and it did so using the most rigorous methods. Scientists randomly assigned 7,447 people in Spain who were overweight, were smokers, or had diabetes or other risk factors for heart disease to follow the Mediterranean diet or a low-fat one.

Low-fat diets have not been shown in any rigorous way to be helpful, and they are also very hard for patients to maintain — a reality borne out in the new study, said Dr. Steven E. Nissen, chairman of the department of cardiovascular medicine at the Cleveland Clinic Foundation.

“Now along comes this group and does a gigantic study in Spain that says you can eat a nicely balanced diet with fruits and vegetables and olive oil and lower heart disease by 30 percent,” he said. “And you can actually enjoy life.”

The study, by Dr. Ramon Estruch, a professor of medicine at the University of Barcelona, and his colleagues, was long in the planning. The investigators traveled the world, seeking advice on how best to answer the question of whether a diet alone could make a big difference in heart disease risk. They visited the Harvard School of Public Health several times to consult Dr. Frank M. Sacks, a professor of cardiovascular disease prevention there.

In the end, they decided to randomly assign subjects at high risk of heart disease to three groups. One would be given a low-fat diet and counseled on how to follow it. The other two groups would be counseled to follow a Mediterranean diet. At first the Mediterranean dieters got more intense support. They met regularly with dietitians while members of the low-fat group just got an initial visit to train them in how to adhere to the diet, followed by a leaflet each year on the diet. Then the researchers decided to add more intensive counseling for them, too, but they still had difficulty staying with the diet.

One group assigned to a Mediterranean diet was given extra-virgin olive oil each week and was instructed to use at least 4 four tablespoons a day. The other group got a combination of walnuts, almonds and hazelnuts and was instructed to eat about an ounce of the mix each day. An ounce of walnuts, for example, is about a quarter cup — a generous handful. The mainstays of the diet consisted of at least three servings a day of fruits and at least two servings of vegetables. Participants were to eat fish at least three times a week and legumes, which include beans, peas and lentils, at least three times a week. They were to eat white meat instead of red, and, for those accustomed to drinking, to have at least seven glasses of wine a week with meals.

They were encouraged to avoid commercially made cookies, cakes and pastries and to limit their consumption of dairy products and processed meats.

To assess compliance with the Mediterranean diet, researchers measured levels of a marker in urine of olive oil consumption — hydroxytyrosol — and a blood marker of nut consumption — alpha-linolenic acid.

The participants stayed with the Mediterranean diet, the investigators reported. But those assigned to a low-fat diet did not lower their fat intake very much. So the study wound up comparing the usual modern diet, with its regular consumption of red meat, sodas and commercial baked goods, with a diet that shunned all that.

Dr. Estruch said he thought the effect of the Mediterranean diet was due to the entire package, not just the olive oil or nuts. He did not expect, though, to see such a big effect so soon. “This is actually really surprising to us,” he said.

The researchers were careful to say in their paper that while the diet clearly reduced heart disease for those at high risk for it, more research was needed to establish its benefits for people at low risk. But Dr. Estruch said he expected it would also help people at both high and low risk, and suggested that the best way to use it for protection would be to start in childhood.

Not everyone is convinced, though. Dr. Caldwell Blakeman Esselstyn Jr., the author of the best seller “Prevent and Reverse Heart Disease: The Revolutionary, Scientifically Proven, Nutrition-Based Cure,” who promotes a vegan diet and does not allow olive oil, dismissed the study.

His views and those of another promoter of a very-low-fat diet, Dr. Dean Ornish, president of the nonprofit Preventive Medicine Research Institute, have influenced many to try to become vegan. Former President Bill Clinton, interviewed on CNN, said Dr. Esselstyn’s and Dr. Ornish’s writings helped convince him that he could reverse his heart disease in that way.

Dr. Esselstyn said those in the Mediterranean diet study still had heart attacks and strokes. So, he said, all the study showed was that “the Mediterranean diet and the horrible control diet were able to create disease in people who otherwise did not have it.”

Others hailed the study.

“This group is to be congratulated for carrying out a study that is nearly impossible to do well,” said Dr. Robert H. Eckel, a professor of medicine at the University of Colorado and a past president of the American Heart Association.

As for the researchers, they have changed their own diets and are following a Mediterranean one, Dr. Estruch said.

“We have all learned,” he said.

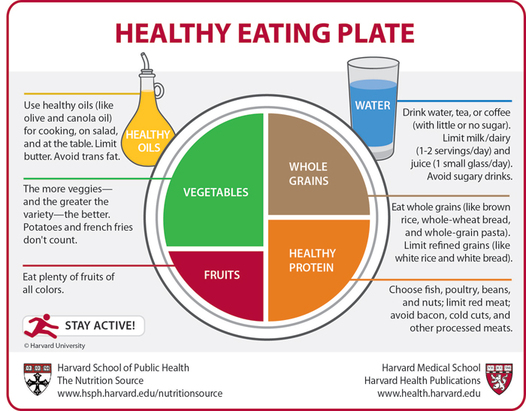

Uncle Sam's Latest Menu

Dietary Dish Simplifies Food Guidelines, Pushes Pyramid Scheme Off the Table

By Bill Tomson and Julie Jargony : WSJ : June 3, 2011

After two decades, the federal government has decided to serve nutrition advice on a plate instead of a pyramid.The U.S. Department of Agriculture introduced the plate-shaped icon Thursday to replace the pyramid that often was criticized as confusing. The plate's sections show the recommended food groups, with fruits and vegetables taking up half the dish.

The plate, which follows the government's revised nutrition guidelines released in January, won praise from nutrition advocates and food industry groups. "People don't eat off a pyramid, they eat off a plate," said Dawn Jackson Blatner, a registered dietitian in Chicago.

The USDA's first version of the food pyramid came out in 1992. With carbohydrates such as bread and spaghetti occupying a band along the base, it gave far less space to fruits and vegetables. It also suggested eating fats "sparingly," which nutritional experts said ignored the benefits of foods with healthier forms of fat.

The guidelines say people should avoid processed foods that are heavy in salt, drink water instead of sugary drinks, and step up fish consumption while depending less on red meat.

First lady Michelle Obama, who has sought to make childhood obesity her signature cause, helped to introduce the plate in Washington. "This is a quick, simple reminder for all of us to be more mindful of the foods that we're eating, and as a mom I can already tell how much this is going to help parents across the country," Mrs. Obama said.

The overall cost of the initiative was approximately $2.9 million over a three-year period, a USDA spokeswoman said.

Food companies applauded the new symbol and stressed their efforts to put healthier products on grocery shelves. "The new MyPlate icon is certainly more practical and intuitive than the previous My Pyramid icon," said Juli Mandel Sloves, a spokeswoman for Campbell Soup Co.

The Center for Science in the Public Interest, a nonprofit group that sometimes tussles with the food industry, called the plate a "huge improvement over the inscrutable food pyramid."

"It likely will shock most people into recognizing that they need to eat a heck of a lot more vegetables and fruits," said the center's Margo Wootan. "Most people are eating about a quarter of a plate of fruits or vegetables, not a half a plate as recommended."

The new USDA icon makes no mention of meat specifically, but American Meat Institute Foundation President James Hodges said beef, pork and poultry are "some of the most nutrient-rich foods available." The plate graphic, he said, "affirms the role that meat and poultry play in a healthy diet, while emphasizing under consumed food groups."

Dietary Dish Simplifies Food Guidelines, Pushes Pyramid Scheme Off the Table

By Bill Tomson and Julie Jargony : WSJ : June 3, 2011

After two decades, the federal government has decided to serve nutrition advice on a plate instead of a pyramid.The U.S. Department of Agriculture introduced the plate-shaped icon Thursday to replace the pyramid that often was criticized as confusing. The plate's sections show the recommended food groups, with fruits and vegetables taking up half the dish.

The plate, which follows the government's revised nutrition guidelines released in January, won praise from nutrition advocates and food industry groups. "People don't eat off a pyramid, they eat off a plate," said Dawn Jackson Blatner, a registered dietitian in Chicago.

The USDA's first version of the food pyramid came out in 1992. With carbohydrates such as bread and spaghetti occupying a band along the base, it gave far less space to fruits and vegetables. It also suggested eating fats "sparingly," which nutritional experts said ignored the benefits of foods with healthier forms of fat.

The guidelines say people should avoid processed foods that are heavy in salt, drink water instead of sugary drinks, and step up fish consumption while depending less on red meat.

First lady Michelle Obama, who has sought to make childhood obesity her signature cause, helped to introduce the plate in Washington. "This is a quick, simple reminder for all of us to be more mindful of the foods that we're eating, and as a mom I can already tell how much this is going to help parents across the country," Mrs. Obama said.

The overall cost of the initiative was approximately $2.9 million over a three-year period, a USDA spokeswoman said.

Food companies applauded the new symbol and stressed their efforts to put healthier products on grocery shelves. "The new MyPlate icon is certainly more practical and intuitive than the previous My Pyramid icon," said Juli Mandel Sloves, a spokeswoman for Campbell Soup Co.

The Center for Science in the Public Interest, a nonprofit group that sometimes tussles with the food industry, called the plate a "huge improvement over the inscrutable food pyramid."

"It likely will shock most people into recognizing that they need to eat a heck of a lot more vegetables and fruits," said the center's Margo Wootan. "Most people are eating about a quarter of a plate of fruits or vegetables, not a half a plate as recommended."

The new USDA icon makes no mention of meat specifically, but American Meat Institute Foundation President James Hodges said beef, pork and poultry are "some of the most nutrient-rich foods available." The plate graphic, he said, "affirms the role that meat and poultry play in a healthy diet, while emphasizing under consumed food groups."

BMI : A Number That May Not Add Up

By Jane E. Brody : NY Times : April 13, 2014

In July 1998, the National Institutes of Health changed what it means to be overweight, defining it as a body mass index of 25 or greater for adults. The cutoff had been 28 for men and 27 for women, so suddenly about 29 million Americans who had been considered normal became overweight even though they hadn’t gained an ounce.

The change, based on a review of hundreds of studies that matched B.M.I. levels with health risks in large groups of people, brought the country in line with definitions used by the World Health Organization and other health agencies. But it also prompted many to question the real meaning of B.M.I. and to note its potential drawbacks: labeling some healthy people as overweight or obese who are not overly fat, and failing to distinguish between dangerous and innocuous distributions of body fat.

More recent studies have indicated that many people with B.M.I. levels at the low end of normal are less healthy than those now considered overweight. And some people who are overly fat according to their B.M.I. are just as healthy as those considered to be of normal weight, as discussed in a new book, “The Obesity Paradox,” by Dr. Carl J. Lavie, a cardiologist in New Orleans, and Kristin Loberg.

Unlike readings on a scale, B.M.I. is based on a person’s weight in relation to his height. It is calculated by dividing weight in kilograms by height in meters squared (or, for those not metric-savvy, weight in pounds divided by height in inches squared and the result multiplied by 703).

According to current criteria, those with a B.M.I. below 18.5 are underweight; those between 18.5 and 24.9 are normal; those between 25 to 29.9 are overweight; and those 30 and higher are obese. The obese are further divided into three grades: Grade 1, in which B.M.I. is 30 to 34.9; Grade 2, 35 to 39.9; Grade 3, 40 and higher.

Before you contemplate a crash diet because your B.M.I. classifies you as overweight, consider what the index really represents and what is now known about its relationship to health and longevity.

The index was devised in the 1830s from measurements in men by a Belgian statistician interested in human growth. More than a century later, it was adopted by insurers and some researchers studying the distribution of obesity in the general population. Though never meant to be an individual assessment, only a way to talk about weight in large populations, B.M.I. gradually was adopted as an easy and inexpensive way for doctors to assess weight in their patients.

At best, though, B.M.I. is a crude measure that “actually misses more than half of people with excess body fat,” Geoffrey Kabat, an epidemiologist at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, has noted. Someone with a “normal” B.M.I. can still be overly fat internally and prone to obesity-related ills.

Calling B.M.I. an imperfect predictor of a person’s health risks, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention cautions doctors against using it as a diagnostic tool.

For one thing, body weight is made up of muscle, bone and water, as well as body fat. B.M.I. alone is at best an imprecise measure of how fat a person may be. When Arnold Schwarzenegger was Mr. Universe, his B.M.I. was well in the obese range, yet he was hardly fat.

Another problem: the distribution of excess body fat makes a big difference to health. Those with lots of abdominal fat, which is metabolically active, are prone to developing insulin resistance, elevated blood lipids, high blood pressure, diabetes, premature cardiovascular disease, and an increased risk of erectile dysfunction and Alzheimer’s disease.

But fat carried in the hips, buttocks or thighs is relatively inert; while it may be cosmetically undesirable, it is not linked to chronic disease or early death.

Furthermore, a person’s age, gender and ethnicity influence the relationship between B.M.I., body fat and health risk. Among children, a high B.M.I. is a good indicator of excess fat and a propensity to remain overly fat into adulthood. But for an elderly person or someone with a chronic disease, a B.M.I. in the range of overweight or obesity may even be protective. Sometimes — after a heart attack or major surgery, for example — extra body fat can provide energy that helps the patient to survive. An added layer of fat can also protect against traumatic injuries in an accident.

On average, women have a higher percentage of body fat in relation to total weight than do men, but this does not necessarily raise their health risks. And African-Americans, who tend have heavier bones and weigh more than Caucasians, face a lower risk to health even with a B.M.I. in the overweight range.

Physical fitness, too, influences the effects of B.M.I. In an editorial in JAMA last year, Dr. Steven B. Heymsfield and Dr. William T. Cefalu of the Pennington Biomedical Research Center in Baton Rouge, La., noted that “cardiorespiratory fitness” is an independent predictor of mortality at any level of fatness.

While experts continue to debate whether a person can be “fit and fat,” Keri Gans, a dietitian in New York and former spokeswoman for the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, points out that physical activity and a healthy diet tend to offset the risks of being overweight.

“You don’t need to be thin to be fit,” she said. At any weight, fitness can reduce the risk of developing heart disease, lung disease, diabetes or high blood pressure.

At the other end of the weight spectrum, people with a low-normal or below-normal B.M.I. (less than 18.5) face a different set of health risks. They may lack sufficient reserves to survive a serious health problem, and they are prone to osteoporosis, infertility and serious infections resulting from a weakened immune system.

Last year a widely publicized meta-analysis covering more than 2.88 million people and 270,000 deaths found that those whose B.M.I. indicated they were overweight and those with Grade 1 obesity were not at a greater risk of death than those in the normal range. And a new analysis of 32 studies by researchers in Australia concluded that for older people, being overweight did not increase mortality, but the risk rose for those at the lower end of normal, with a B.M.I. of less than 23.

By Jane E. Brody : NY Times : April 13, 2014

In July 1998, the National Institutes of Health changed what it means to be overweight, defining it as a body mass index of 25 or greater for adults. The cutoff had been 28 for men and 27 for women, so suddenly about 29 million Americans who had been considered normal became overweight even though they hadn’t gained an ounce.

The change, based on a review of hundreds of studies that matched B.M.I. levels with health risks in large groups of people, brought the country in line with definitions used by the World Health Organization and other health agencies. But it also prompted many to question the real meaning of B.M.I. and to note its potential drawbacks: labeling some healthy people as overweight or obese who are not overly fat, and failing to distinguish between dangerous and innocuous distributions of body fat.

More recent studies have indicated that many people with B.M.I. levels at the low end of normal are less healthy than those now considered overweight. And some people who are overly fat according to their B.M.I. are just as healthy as those considered to be of normal weight, as discussed in a new book, “The Obesity Paradox,” by Dr. Carl J. Lavie, a cardiologist in New Orleans, and Kristin Loberg.

Unlike readings on a scale, B.M.I. is based on a person’s weight in relation to his height. It is calculated by dividing weight in kilograms by height in meters squared (or, for those not metric-savvy, weight in pounds divided by height in inches squared and the result multiplied by 703).

According to current criteria, those with a B.M.I. below 18.5 are underweight; those between 18.5 and 24.9 are normal; those between 25 to 29.9 are overweight; and those 30 and higher are obese. The obese are further divided into three grades: Grade 1, in which B.M.I. is 30 to 34.9; Grade 2, 35 to 39.9; Grade 3, 40 and higher.

Before you contemplate a crash diet because your B.M.I. classifies you as overweight, consider what the index really represents and what is now known about its relationship to health and longevity.

The index was devised in the 1830s from measurements in men by a Belgian statistician interested in human growth. More than a century later, it was adopted by insurers and some researchers studying the distribution of obesity in the general population. Though never meant to be an individual assessment, only a way to talk about weight in large populations, B.M.I. gradually was adopted as an easy and inexpensive way for doctors to assess weight in their patients.

At best, though, B.M.I. is a crude measure that “actually misses more than half of people with excess body fat,” Geoffrey Kabat, an epidemiologist at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, has noted. Someone with a “normal” B.M.I. can still be overly fat internally and prone to obesity-related ills.

Calling B.M.I. an imperfect predictor of a person’s health risks, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention cautions doctors against using it as a diagnostic tool.

For one thing, body weight is made up of muscle, bone and water, as well as body fat. B.M.I. alone is at best an imprecise measure of how fat a person may be. When Arnold Schwarzenegger was Mr. Universe, his B.M.I. was well in the obese range, yet he was hardly fat.

Another problem: the distribution of excess body fat makes a big difference to health. Those with lots of abdominal fat, which is metabolically active, are prone to developing insulin resistance, elevated blood lipids, high blood pressure, diabetes, premature cardiovascular disease, and an increased risk of erectile dysfunction and Alzheimer’s disease.

But fat carried in the hips, buttocks or thighs is relatively inert; while it may be cosmetically undesirable, it is not linked to chronic disease or early death.

Furthermore, a person’s age, gender and ethnicity influence the relationship between B.M.I., body fat and health risk. Among children, a high B.M.I. is a good indicator of excess fat and a propensity to remain overly fat into adulthood. But for an elderly person or someone with a chronic disease, a B.M.I. in the range of overweight or obesity may even be protective. Sometimes — after a heart attack or major surgery, for example — extra body fat can provide energy that helps the patient to survive. An added layer of fat can also protect against traumatic injuries in an accident.

On average, women have a higher percentage of body fat in relation to total weight than do men, but this does not necessarily raise their health risks. And African-Americans, who tend have heavier bones and weigh more than Caucasians, face a lower risk to health even with a B.M.I. in the overweight range.

Physical fitness, too, influences the effects of B.M.I. In an editorial in JAMA last year, Dr. Steven B. Heymsfield and Dr. William T. Cefalu of the Pennington Biomedical Research Center in Baton Rouge, La., noted that “cardiorespiratory fitness” is an independent predictor of mortality at any level of fatness.

While experts continue to debate whether a person can be “fit and fat,” Keri Gans, a dietitian in New York and former spokeswoman for the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, points out that physical activity and a healthy diet tend to offset the risks of being overweight.

“You don’t need to be thin to be fit,” she said. At any weight, fitness can reduce the risk of developing heart disease, lung disease, diabetes or high blood pressure.

At the other end of the weight spectrum, people with a low-normal or below-normal B.M.I. (less than 18.5) face a different set of health risks. They may lack sufficient reserves to survive a serious health problem, and they are prone to osteoporosis, infertility and serious infections resulting from a weakened immune system.

Last year a widely publicized meta-analysis covering more than 2.88 million people and 270,000 deaths found that those whose B.M.I. indicated they were overweight and those with Grade 1 obesity were not at a greater risk of death than those in the normal range. And a new analysis of 32 studies by researchers in Australia concluded that for older people, being overweight did not increase mortality, but the risk rose for those at the lower end of normal, with a B.M.I. of less than 23.