- RETIREMENT ANNOUNCEMENT

- HOME PAGE

- "MYCHART" the new patient portal

- BELMONT MEDICAL ASSOCIATES

- MOUNT AUBURN HOSPITAL

- EMERGENCIES

- PRACTICE PHILOSOPHY

- MY RESUME

- TELEMEDICINE CONSULTATION

- CONTACT ME

- LAB RESULTS

- ePRESCRIPTIONS

- eREFERRALS

- RECORD RELEASE

- MEDICAL SCRIBE

- PHYSICIAN ASSISTANT (PA)

- Medicare Annual Wellness Visit

- Case management/Social work

- Quality Care Measures

- Emergency closing notice

- FEEDBACK

- Talking to your doctor

- Choosing..... and losing a doctor

- INDEX A - Z

- ALLERGIC REACTIONS

- Alternative Medicine

- Alzheimer's Disease

- Bladder Problems

- Blood disorders

- Cancer Concerns

- GENETIC TESTING FOR HEREDITARY CANCER

- Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

- Controversial Concerns

- CPR : Learn and save a life

- CRP : Inflammatory marker

- Diabetes Management

- Dizziness, Vertigo,Tinnitus and Hearing Loss

- EXERCISE

- FEMALE HEALTH

-

GASTROINTESTINAL topics

- Appendicitis

- BRAT diet

- Celiac Disease or Sprue

- Crohn's Disease

- Gastroenterologists for Colon Cancer Screening

- Colonoscopy PREP

- Constipation

- Gluten sensitivity, but not celiac disease

- Heartburn and GERD

- Hemorrhoids and Anal fissure

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- NASH : Non Alcoholic Steato Hepatitis

- FEET PROBLEMS

- HEART RELATED topics

-

INFECTIOUS DISEASES

- Antibiotic Resistance

- Cat bites >

- Clostridia difficile infection - the "antibiotic associated germ"

- CORONA VIRUS

- Dengue Fever and Chikungunya Fever

- Food borne illnesses

- Shingles Vaccine

- Hepatitis B

- Hepatitis C

- Herpes

- Influenza

- Helicobacter pylori - the "ulcer germ"

- HIV Screening

- Lyme and other tick borne diseases

- Measles

- Meningitis

- MRSA (Staph infection)

- Norovirus

- Sexually Transmitted Diseases

- Shingles (Herpes Zoster)

- Sinusitis

- West Nile Virus

- Whooping Cough (Pertussis)

- Zika virus and pregnancy

- INSURANCE related topics

- KIDNEY STONES

- LEG CRAMPS

- LIBRARY for patients

- LIFE DECISIONS

- MALE HEALTH

- Medication/Drug side effects

- MEDICAL MARIJUANA

- MENTAL HEALTH

- Miscellaneous Articles

-

NUTRITION - EXERCISE - WEIGHT

- Cholesterol : New guidelines for treatment

- Advice to lower your cholesterol

- Cholesterol : Control

- Cholesterol : Raising your HDL Level

- Exercise

- Food : Making Smart Choices

- Food : Making Poor Choices

- Food : Grape Fruit and Drug Interaction

- Food : Vitamins, Minerals and Supplements

- Omega 3 fatty acids

- Vitamin B12 deficiency

- Vitamin D

- Weight Loss

- ORTHOPEDICS

- PAIN

- PATIENTS' RIGHTS

- SKIN

- SLEEP

- SMOKING

- STROKE

- THYROID

- SUBSTANCE ABUSE

- Travel and Vaccination

- TREMOR

- Warfarin Anticoagulation

- OTHER STUFF FOLLOWS

- Fact or Opinion?

- Hippocratic Oath

- FREE ADVICE.......for what its worth!

- LAUGHTER.....is the best medicine

- Physicians Pet Peeves

- PHOTO ALBUM - its not all work!

- Cape Town, South Africa

- Tribute page

- The 100 Club

- Free Wi-Fi

Female : Health Topics

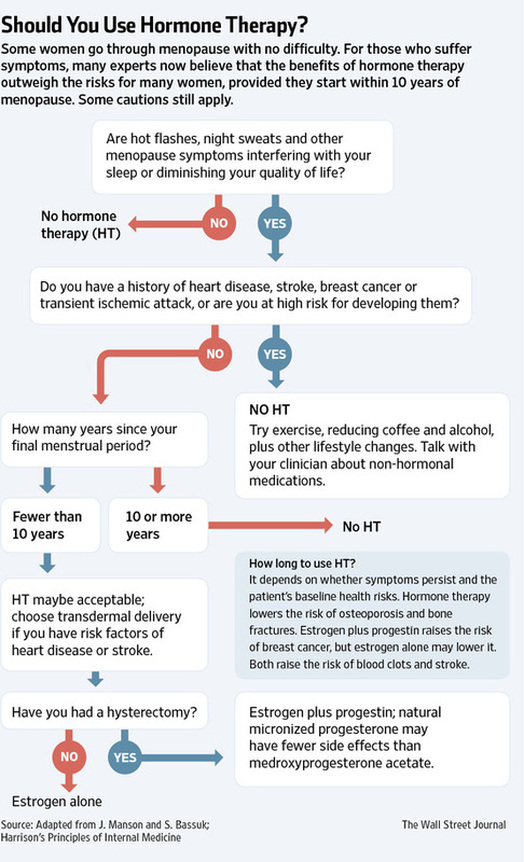

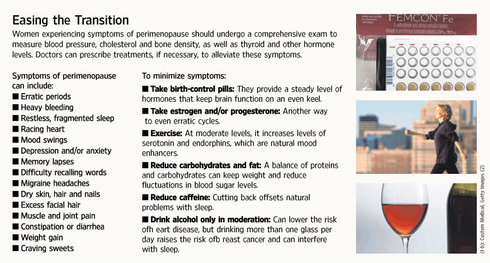

Tackling Menopause’s Side Effects

By Jane E. Brody : NY Times : February 10, 2014

In the-better-late-than-never department, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists has revised its guidelines for effective treatment of the symptoms of menopause.

Published as a practice bulletin for doctors called “Management of Menopausal Symptoms,” the new guidelines recognize that up to three-fourths of women in the United States experience troublesome side effects when their bodies stop producing estrogen as a result of natural or medically induced menopause. The document addresses the most common distressing consequences: hot flushes and vaginal atrophy.

Hot flushes can last for months or even decades, but vaginal problems, if untreated, persist for the remainder of a woman’s life.

Hot flushes can cause drenching, sometimes embarrassing sweating, and seriously disrupt sleep night after night. Vaginal atrophy and the loss of lubrication and elasticity can make sexual encounters painful, depress libido and cause irritation and bleeding during exercise.

You might think the standard treatment would be to administer the hormones that menopausal women are losing. Indeed, supplementation with estrogen was a common practice for decades, and not just for curbing menopausal symptoms. Estrogen was widely promoted as a way to protect women’s health and to keep looking and feeling young well into old age.

But in 2002, a large clinical trial called the Women’s Health Initiative found that the most popular form of hormone replacement, a pill that combined estrogen and synthetic progesterone called Prempro, increased a woman’s risk of heart disease, breast cancer, stroke and blood clots .

The highly publicized results tainted hormone therapy with a broad brush. Although the Women’s Health Initiative was designed primarily to test the popular premise that hormone replacement after menopause protected women’s hearts, the unexpected findings prompted millions of middle-aged and older women to stop using the hormones and kept many millions more from starting them.

Even though the vast majority of the 16,608 participants in the study were older women well past menopause, the findings were widely interpreted to apply to all women going through menopause, even younger women just approaching the end of their fertile years.

Somewhat frenetic experimentation ensued as physicians, drug companies and women themselves searched for effective alternatives to hormone replacement. Various nonhormonal remedies were promoted, from soy foods and black cohosh to exercise and acupuncture. Each had its advocates, but all lacked rigorous scientific evidence for effectiveness.

Those promoting soy-based foods and supplements, for example, cited the low reported rates of menopausal symptoms among Asian women, whose diets are especially rich in soy, which has estrogenic effects. An authoritative review of placebo-controlled studies of plant-based estrogens, however, found no convincing evidence that they were helpful in curbing menopausal hot flushes. (One exception was genistein, a substance in soy, which the researchers said warranted further study.)

The new bulletin, prepared by Dr. Clarisa R. Gracia, an associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Pennsylvania, examines the various claims and scores of studies. It offers treatment recommendations based on the best available evidence for preserving the health and well-being of women experiencing menopausal symptoms.

In an interview, Dr. Gracia acknowledged that “there’s a strong placebo effect” when women try one or another suggested remedy for menopausal distress. She admitted that “it’s all for the better” if an innocuous placebo, like a food or supplement, brings relief to some women.

But most women do best when their physicians offer remedies that have been shown to be effective in well-designed studies. And as you might guess, estrogen alone, or in combination with a natural or synthetic progesterone (progestin) for women who still have a uterus, is the “most effective therapy” for curbing hot flushes, the report found.

“Data do not support the use of progestin-only medications, testosterone or compounded bioidentical hormones,” the report also said.

Estrogen with or without progestin can be administered orally or through the skin with a patch, gel or spray. The transdermal route is considered safer: When absorbed through the skin, the hormones bypass the liver, which would otherwise create substances that might raise the risk of heart attack or cancer.

The report emphasizes that treatment with hormones must be individualized and that doctors should prescribe the lowest effective dose for the shortest time needed to relieve hot flushes. But because some women may need hormone therapy to control hot flushes even in their Medicare years, the guidelines recommend “against routine discontinuation of systemic estrogen at age 65.”

Hormone replacement can be risky for some women, especially those who have had breast cancer. Alternatives that have proved helpful include low doses of antidepressants known as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (S.S.R.I.’s), like Paxil, and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (S.N.R.I.’s), like Pristiq. Clonidine, a blood pressure medication, and gabapentin, an anticonvulsant, may also be helpful, though neither is approved by the Food and Drug Administration for menopausal treatment.

The report found little or no data to support the use of herbal remedies, vitamins, phytoestrogens (like isoflavones, soy and red clover) or acupuncture to relieve hot flushes. It did recommend “common sense lifestyle solutions” like dressing in layers, lowering room temperatures, consuming cool drinks, and avoiding alcohol and caffeine. For overweight and obese women, weight loss can also help.

As with hot flushes, vaginal symptoms respond best to estrogen therapy, which can be administered through the mouth or skin or locally via a cream, tablet or ring. Even a low-dose vaginal tablet containing 10 micrograms of estradiol improves symptoms, the report noted.

Low-dose vaginal treatments are administered daily for a week or two at first, then once or twice a week indefinitely as maintenance therapy.

Because small amounts of estrogen used vaginally can enter general circulation, women who have had hormone-sensitive breast cancer are advised to try nonhormonal remedies first.

Many women experience relief of symptoms with lubricants and moisturizers prepared with water or silicone. Lubricants, applied just before intercourse, can reduce friction and pain caused by dryness. Moisturizers are used routinely to relieve dryness, itching, irritation and pain, and to improve elasticity.

Last year, the Food and Drug Administration approved Osphena (ospemifene) to treat vaginal atrophy related to menopause. The drug, taken orally once a day, is a selective estrogen receptor modulator that has estrogenlike effects in the vagina.

But Osphena, too, can promote endometrial growth. It is not recommended for women who have had breast cancer, and it is not intended for long-term use.

No wonder we are all confused!

1991 National Institutes of Health embarks on a study of menopause hormones after observational data suggest that women who use hormones have lower rates of heart disease.

2002 Part of the Women's Health Initiative is stopped after women in the study taking estrogen plus progestin (E+P) show higher rates of heart attack, stroke and breast cancer. Millions of women abandon hormones overnight.

2003 Women taking E+P are not protected from mild memory loss; they are found to be at increased risk for developing dementia.

2004 The second W.H.I. hormone study is stopped one year early because women taking estrogen only show a small increased risk of stroke.

2006 An updated analysis of the estrogen-only trial shows hormone therapy does not increase the risk of breast cancer in postmenopausal women.

2007 Combined data from both hormone trials suggest that timing of therapy may affect risk; hormones may reduce heart disease in women who start therapy closer to menopause.

2009 Women using E+P for more than about five years double their annual risk of breast cancer. That risk is higher than previously thought.

2011 Follow-up of women in the estrogen-only study shows those who took just estrogen had 23 percent fewer breast cancers; younger estrogen users had 46 percent fewer heart attacks.

1991 National Institutes of Health embarks on a study of menopause hormones after observational data suggest that women who use hormones have lower rates of heart disease.

2002 Part of the Women's Health Initiative is stopped after women in the study taking estrogen plus progestin (E+P) show higher rates of heart attack, stroke and breast cancer. Millions of women abandon hormones overnight.

2003 Women taking E+P are not protected from mild memory loss; they are found to be at increased risk for developing dementia.

2004 The second W.H.I. hormone study is stopped one year early because women taking estrogen only show a small increased risk of stroke.

2006 An updated analysis of the estrogen-only trial shows hormone therapy does not increase the risk of breast cancer in postmenopausal women.

2007 Combined data from both hormone trials suggest that timing of therapy may affect risk; hormones may reduce heart disease in women who start therapy closer to menopause.

2009 Women using E+P for more than about five years double their annual risk of breast cancer. That risk is higher than previously thought.

2011 Follow-up of women in the estrogen-only study shows those who took just estrogen had 23 percent fewer breast cancers; younger estrogen users had 46 percent fewer heart attacks.

7 Things You Should Know About Hormone Replacement Therapy

Melinda Beck : WSJ Article : February 3, 2009

A muddle of misinformation keeps clouding the debate over hormone-replacement therapy for women.

Last week, millions of women tuned into "The Oprah Winfrey Show" to hear actress Suzanne Somers sympathize with women suffering from what she called "The Seven Dwarfs of Menopause: Itchy, Bitchy, Sleepy, Sweaty, Bloated, Forgetful and All Dried Up." As she's done in her best-selling books, Ms. Somers, age 62, credited a custom-made blend of "bio-identical" hormones with maintaining her youthful zest and told viewers that the hormone debate boils down to a choice between "restoration versus deterioration."

There was little discussion of potential risks of HRT. The compounding pharmacies that make up such custom blends of hormones without oversight by the Food and Drug Administration often claim their products are so natural that they confer the benefits of hormone replacement (from restoring sleep, mood, memory and sexiness to protecting against osteoporosis) without the risks.

Millions of women abandoned menopause hormones after the big Women's Health Initiative trial was halted early in 2002 amid signs that they increased the risk of heart attack and stroke. A growing number of experts now believe that the women in the WHI -- average age 63 -- do not reflect the typical women entering menopause, and that the same risks may not apply to younger women.

Even so, women seeking safer alternatives have turned to "bio-identicals" -- a trend that worries mainstream medical groups. "Women who were afraid after the WHI, as were their doctors, are going to alternative approaches that have little or no scientific information behind them," says Margaret Weirman, a professor of medicine at the University of Colorado Denver and a spokeswoman for the Endocrine Society, a professional organization devoted to hormone research. "These women may be putting themselves at much higher levels of risk."

Amid all the confusion, here are seven things women should know about the HRT debate now:

1) 'Bio-identical' hormones are available in FDA-approved forms.

Though many experts dismiss "bio-identical" as a meaningless term, proponents use it to mean hormones with the same molecular structure as those that women's bodies make. The main one lost at menopause is estradiol, which affects functions throughout the female body, from skin to bones, hearts and brains. Chemically equivalent estradiol is available in many FDA-approved pills, patches, creams and gels from traditional drug companies, generally made from the exact same plant sources that compounding pharmacies use. What's more, the FDA-approved varieties are covered by insurance, unlike compounded blends that can cost hundreds of dollars a month.

A growing number of doctors prescribe these estradiol-based products instead of Premarin, the estrogen made from horse urine that was used in the WHI. Many also prefer natural progesterone, available in FDA-approved Prometrium, to the synthetic form that was used in the WHI. But there is little evidence comparing one HRT variety against another.

2) Hormones from compounding pharmacies aren't safer than conventional HRT.

Compounded drugs don't carry warnings or list side effects on their labels, but that's because they are not made under FDA scrutiny. In fact, they can vary greatly in strength and potency and little is known about how they release active ingredients over time. "We don't know if it comes out in peaks and valleys or continuously," says Dr. Weirman. "Some people may be getting very high doses, and some people may be getting very little or none."

The International Academy of Compounding Pharmacists contends that its members perform a valuable service in making drugs and strengths that aren't commercially available, that they are providing women with freedom of choice in health-care decisions and that much of the criticism is coming from groups funded by makers of traditional HRT.

3) Don't trust saliva tests.

Some compounding pharmacies use saliva tests to monitor women's hormone levels and develop custom blends. But many experts say such tests (which can cost hundreds of dollars) are unreliable and lack uniform standards.

Blood tests are more accurate -- but monitoring how women feel is just as key. Many doctors believe that HRT should be used mainly to treat actual symptoms such as hot flashes, mood swings, sleep problems, foggy thinking and other symptoms, rather than arbitrary blood levels since individual ranges vary widely. FDA-approved estradiol products are available in a wide variety of strengths that can be tapered as a woman's symptoms change.

Hormone Options

FDA-approved products with estradiol:

There's a growing consensus that the risks and benefits are different for younger and older women, and that for women who start HRT shortly after menopause, the benefits may outweigh the risks. Women in the WHI who were 20 years past menopause had a 71% higher risk of heart attack on estrogen and progesterone than those taking placebos, but women closer to menopause had an 11% lower risk of heart problems. One theory is that estrogen helps keep healthy blood vessels supple, but make atherosclerosis worse once it has set in.

Similarly, HRT seems to help preserve thinking ability when started just after menopause, but it may hasten the progression of pre-existing memory problems when started later in life, writes JoAnn E. Manson, a Harvard Medical School professor who was a lead investigator on both the WHI and the long-running Nurses' Health Study, in her new book, "Hot Flashes, Hormones and Your Health."

HRT was associated with a lower risk of fractures and colorectal cancer regardless of age. The WHI did not assess whether HRT improved quality-of-life issues such as mood, sleep and hot flashes. Women experiencing such symptoms were excluded from the study on the grounds that immediate effects might prompt some to guess whether they were in the control or placebo group.

5) The increased risk of breast cancer appears related to progesterone rather than estrogen.

Women taking both estrogen and progesterone in the WHI had eight more cases of breast cancer per 10,000 than the control group; women taking estrogen alone had six fewer cases. Women who still have a uterus need some progesterone to guard against uterine cancer, but many doctors now try to give the lowest dose possible to prevent a build-up of uterine lining.

6) Estrogen applied to the skin, in patch, cream or gel form, may have a lower risk of blood clots and strokes than in pill form.

A large study in France published in the Lancet found that women taking estrogen in pill form were three times as likely to develop blood clots than non-users, while women using the estradiol patch had no increased risk. But more study is needed to determine this conclusively.

7) Stay tuned.

Several of these new theories are being tested in another trial called KEEPS (for Kronos Early Estrogen Prevention Study) that is comparing 720 newly menopausal women on oral Premarin, an estrogen patch or placebo. Investigators will monitor their arteries, as well as quality-of-life aspects like mood, fatigue, sleep, bone health and cognition.

In the meantime, women entering menopause should discuss all the risks and benefits with their doctors, as well as their symptoms, health and family history, and make an individual, informed decision.

For Some in Menopause, Hormones May Be Only Option

By Tara Parker-Pope : NY Times : August 15, 2011

For women hoping to combat the symptoms of menopause with nonprescription alternatives like soy and flaxseed supplements, recent studies have held one disappointment after another.

Last week, a clinical trial found that soy worked no better than a placebo for hot flashes and had no effect on bone density. That followed a similar finding about hot flashes from a clinical trial of flaxseed.

“We wish we could have told women that, yes, they work,” said Dr. Silvina Levis, director of the osteoporosis center at the University of Miami, who led the soy study. “Now we have shown that they don’t.”

Before 2002 women were routinely treated with the prescription hormones estrogen and progestin, which rapidly fell out of favor after the landmark Women’s Health Initiative study showed that older women who used them had a heightened risk of heart attacks and breast cancer.

But now some doctors are arguing that those risks do not apply to the typical woman with menopause symptoms, and even some longtime critics of hormone treatment are suggesting that it be given another look for women suffering from severe symptoms.

Study after study has shown that many nondrug treatments — black cohosh, red clover, botanicals, and now soy and flaxseed — simply don’t work. Prescription medicines, including antidepressants, the blood pressure drug clonidine and the seizure drug gabapentin may have some benefit, but many women cannot tolerate the side effects.

“There is no alternative treatment that works very well, whether it’s a drug or over-the-counter herbal preparation,” said Dr. Deborah Grady, associate dean for clinical and translational research at the University of California, San Francisco.

About 75 percent of menopausal women experience hot flashes. Depending on the woman, symptoms can be mild, occurring only a few times a week, or moderate, occurring several times a day. Many women with mild to moderate symptoms cope without needing further treatment. But about a third of women have severe symptoms, experiencing 10 to 20 hot flashes day and night that disrupt their workdays and interfere with sleep.

While doctors often reassure women that it will all be over in just a few years, a May report in the journal Obstetrics and Gynecology found that during one long-term study of women, menopausal hot flashes recurred for some women, for 10 years or more.

A hot flash is usually described as a sudden warmth first felt in the face and neck. Hot flashes can turn a woman’s face red and lead to excessive sweating and then chills. On the Web site MinniePauz.com, women describe feeling lightheaded and dazed, with heart palpitations and anxiety.

“Whoosh, a rush of heat originating from the core of your body,” is how one woman put it. “Hair goes lank and you know that even if you stripped naked and ran down the high street waving your arms to fan your body, well you still wouldn’t get cool because the heat is inside you, not outside.”

The exact cause of hot flashes is not known, but it is believed that menopause disrupts the function of the hypothalamus, which is essentially the body’s thermostat. As a result, even small changes in body temperature that would normally go unnoticed can set off hot flashes.

Among prescription drug treatments, the most effective may be antidepressants, including Effexor, Paxil and Pristiq, which have been shown to reduce hot flashes by as much as 60 percent, doctors say. Antidepressants are particularly useful for women with breast cancer or blood-clot disorders who do not have the option of taking a hormone drug.

But some doctors say they are frustrated by the message given to many women that they must seek an alternative treatment to prescription hormones. Dr. Holly Thacker, director of the center of specialized women’s health at the Cleveland Clinic, said that for many women the benefits of effective hormone treatment would outweigh the risks and that they should not be scared off from considering the drugs.

“It would be like telling someone with insulin-dependent diabetes that they should try to use other things besides insulin,” she said. “I see women look to alternative agents and coming in with bags of things, and they have no idea what they are putting into their body. There has been so much misinformation, and they are confused.”

Dr. Grady, a longtime critic of widespread hormone use, said doctors and women appeared to be less tolerant of risks associated with hormones than of those with other drugs, even though menopause symptoms can be just as intolerable as migraine pain or other health problems.

“Somehow we’re quite willing to take a migraine drug with its associated adverse effects because it works so well, but we’re not willing to take estrogen,” she said. “We worry about the adverse effects associated with estrogen, but the important adverse effects are reasonably uncommon.

“The question is whether a woman is willing to trade off that risk for a very effective treatment for symptoms that are otherwise ruining her life.”

Subtle Science: Heading Off Heart Attacks in Women

By Melinda Beck

WSJ Article : November 25, 2008

Men's and women's hearts are different -- in ways that doctors are still working to understand.

A recent government report adds more mystery: According to the federal Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, or AHRQ, women are far more likely than men to be hospitalized for chest pain for which doctors can't find a cause.

In 2006, the latest data available, 477,000 women were discharged from U.S. hospitals with a diagnosis of nonspecific chest pain, compared with 379,000 men. That diagnosis is often given to patients who are admitted for a possible heart attack that turns out not to be one.

Heart disease is the No. 1 killer of both sexes, claiming more lives each year than all cancers combined. More women than men have died from heart disease in the U.S. every year since 1984, and they are twice as likely as men to die after a heart attack, according to the National Coalition for Women with Heart Disease.

But heart attacks often look different in women than men. While both frequently report chest pain, pressure or tightness, women more often have subtle signs instead, including dizziness, nausea, breathlessness, aches in the back, shoulders or abdomen, sudden weakness or fatigue or an overwhelming feeling of doom. A 2003 study found that 95% of women who had heart attacks started feeling some of those symptoms a month or more before.

"Women are very into their bodies -- they know when they aren't feeling well," says Nieca Goldberg, medical director of New York University's Women's Heart Program. "That's the time to call your doctor, when there's still time to prevent a heart attack."

Could some of those nonspecific chest pains in the AHRQ report have been early warning signs? There's no way of knowing, since the statistics don't track whether patients returned with a heart attack later.

Warning for Women

Chest pain is a common symptom in heart attacks, but women may instead have:

But even when women do have such diagnostic tests, doctors are less likely to find CAD. "Women with chest pain are much more likely to have normal coronary arteries," says Rita F. Redberg, director of Women's Cardiovascular Services at the University of California -- San Francisco School of Medicine. "The truth is, we don't always find out what causes it."

One theory is that some chest pain in women may be due to microvascular disease -- blockages in tiny vessels that can't be seen on an angiogram. Such blockages are also too small to be opened with stents or angioplasty, but can be treated with beta blockers and nitroglycerine.

Given the growing awareness that heart attacks present differently in women, the AHRQ data may indicate that doctors are treating women with chest pain more proactively than they used to.

"Women's chest pain is increasingly taken more seriously -- even if it's atypical -- so doctors may have a lower threshold for admitting them," says cardiologist Edmund M. Herrold, a professor of medicine at the State University of New York-Downstate Medical Center in Brooklyn. "I think that's a good thing. In the past, women who should have been admitted were being sent home."

Should women think twice about getting help if they're having chest pain? "We're always trying to draw that line fine -- not wanting people to ignore symptoms, but not thinking it's a heart attack everytime they get a twinge," says Dr. Redberg.

Studies show that women wait longer than men before going to the hospital -- in part because the symptoms may be subtle, and in part because they don't want to "bother" doctors if nothing's wrong. But two-thirds of women who have heart attacks never make it to the hospital.

If you have any of the symptoms for more than a few minutes, seek help quickly. "Don't sit home and wonder," says Dr. Goldberg, who sometimes has to beg patients who call her in the middle of the night to go to the hospital.

She also suggests calling 911 rather than going on your own: "You'll get taken care of faster in the emergency room if you arrive by ambulance. The hospital can call the doctor for you."

Beyond Hysterectomy: Alternative Options for Heavy Bleeding

By Carolyn Sayre

NY Times Article : October 3, 2008

In Brief:

Heavy or prolonged bleeding affects nearly one in five women ages 35 to 49.

Hysterectomy was the treatment of choice 20 years ago, but new options like the Mirena intrauterine device and medications often make surgery unnecessary.

Today, many women with menorrhagia continue to suffer because they are unaware of new treatment options.

It’s rare to find a woman who has never had any trouble with her period. For most, though, the hassles are fairly minor — irritability, mild cramping and the occasional surprise visit. But for the nearly one in five women ages 35 to 49 who suffer from menorrhagia — heavy or prolonged bleeding — their menstrual cycle puts life on hold every month.

“It controlled my life,” said Stefanie Haase, 37, an X-ray technician from Sodus, N.Y., who started bleeding uncontrollably two years ago because of a large fibroid. “I had to carry an extra set of clothes with me at all times. I couldn’t drive without messing up the car, or plan a vacation. My life revolved around my period.”

Twenty years ago, women like Ms. Haase did not have many options. For the nearly 40 percent of women whose abnormal bleeding stemmed from anatomical problems like fibroids and polyps, an invasive surgical procedure to remove the noncancerous growths, called a myomectomy, was often helpful but did not always stop the bleeding. For the majority of patients, the outlook was pretty unpleasant. High-dose hormones caused a host of side effects like rapid weight gain. A procedure called dilation and curettage, or D&C, which scraped away the lining of the uterus, typically failed to stop the bleeding for more than a few months.

Ms. Haase would have quickly found herself out of options and, like many women living with menorrhagia back then, her last resort would likely have been a hysterectomy — major surgery to remove the uterus and sometimes other reproductive organs as well. But thanks to new treatments and techniques, all that has changed.

“Women no longer need to choose between suffering and major surgery,” said Dr. Glenn Schattman, a reproductive surgeon and associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the New York Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Medical College of Cornell. “Today, the key is avoiding major surgery, and thankfully, the overwhelming majority of patients can now be treated with minimally invasive procedures or medication.”

The changes began in 1987, when the Food and Drug Administration approved a laser that could destroy the lining of the uterus by heating it. The laser outpatient procedure that became known as endometrial ablation was a retreat from the finality of a hysterectomy, which not only removes major organs but, back then, also required up to two months of recovery time.

A few years later, physicians began to refine the procedure, developing more sophisticated techniques like endometrial resection, which removes the uterine lining entirely.

“Women who lived 20 years ago were pushed onto a track with very few off-ramps,” said Dr. Morris Wortman, director of the Center for Menstrual Disorders & Reproductive Choice in Rochester. “Endometrial ablation changed that by obviating the need for hysterectomy. It gave women choices.”

Dr. Wortman notes that endometrial ablation stops bleeding in nearly half of women and significantly reduces bleeding in another 40 percent.

But like most procedures, endometrial ablation and resection also have downsides. About 15 percent of patients still need a hysterectomy, and while the uterus remains intact after the endometrial procedures, a woman’s chance of conception is destroyed.

Medical therapies now help eliminate some of the fertility concerns. In the early ’90s, low-dose birth control pills began to be prescribed for women with heavy bleeding who did not have structural problems. Perhaps the biggest breakthrough came in 2001, when the F.D.A. approved Mirena, an intrauterine birth control device that lightens bleeding in more than 80 percent of women.

Today, most physicians consider the fertility-preserving Mirena IUD to be the first-line treatment for heavy bleeding in women with normal anatomy.

“It works beautifully,” said Dr. Linda Bradley, director of hysteroscopic services for the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the Cleveland Clinic’s Center for Menstrual Disorders and Fibroids. “Women who take it either don’t get their period or bleed very lightly.”

That was certainly the case for Sheila Woodruff, 45, of Cleveland, who started using the Mirena IUD last spring. After two years of heavy bleeding that lasted up to 10 days every month and caused her to change her clothes every couple hours, she finally had enough.

The Mirena IUD, she said, “was unbelievable.”

“My period magically became normal again.”

In a small percentage of women, the device causes side effects like spotting or abdominal pain and may need to be removed.

And for women with anatomical problems like fibroids and polyps, minimally invasive procedures like laparoscopic myomectomy have reduced recovery time significantly. And uterine fibroid embolization, a nonsurgical technique that shrinks or kills the growths by cutting off their blood supply, has helped certain patients with structural problems avoid surgery altogether.

Now that alternative treatments to hysterectomy have been developed, physicians say their biggest challenge is raising awareness and acceptance among women, many of whom still fear that major surgery is their only option.

“I can’t believe how many women are essentially bedridden during their periods for a year or two before they see a doctor,” Dr. Schattman said. “They are still scared that heavy bleeding means they will need a hysterectomy.”

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 20 million women now living in the United States have had a hysterectomy. “That number should be lower,” Dr. Wortman said. “And it would be if more women understood all of their options.”

Despite the fact that many physicians say the Mirena device is safe and remarkably effective, women who remember the infamous side effects of the Dalkon Shield, a popular IUD used in the ’70s, still shy away from using it. What’s more, techniques like endometrial ablation and resection have only really begun to catch on in the last 10 years or so as technological advancements have made it easier for less-specialized gynecologists to perform the procedures.

Ms. Haase, for one, waited it out for nearly two years before she underwent surgery. Unlike most patients with fibroids, she underwent both a myomectomy and endometrial resection to stop her bleeding.

“My mother had a hysterectomy when she was 33, so I figured that was my fate,” she said. “But there are so many options out there. I only wish I had known that two years ago.”

More doctors are challenging the convention of removing the cervix during a hysterectomy

By Laura Johannes

WSJ Article : February 24, 2009

For decades, surgeons performing a hysterectomy, or removal of the uterus, typically cut out the woman's cervix as well. If it were left in, doctors reasoned, it could develop cancer.

Now, a growing number of gynecologists are marketing "cervix-sparing" hysterectomies if cancer isn't present. The chance of cervical cancer is fairly low, and Pap-smear screening will catch most cases, these doctors say. And leaving the cervix untouched reduces the risk of surgical damage to the bladder and nearby nerves, and may even allow a woman to enjoy a better sex life long term, say doctors who perform these procedures.

Not so fast, argues the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. The influential nonprofit doctors' group argued in a 2007 report that evidence was lacking that sparing the cervix improves one's sex life or bladder function. And if a growth develops, removing the cervix alone carries higher risk, including infection, than a hysterectomy, the group says. "It's not appropriate for surgeons to recommend it as a superior technique," says Denise Jamieson, chairman of the committee that wrote the report.

Cutting Less

More doctors are challenging the convention of removing the cervix during a hysterectomy. Here's why:

Now the tide appears to be turning. In 2006, 9.7% of U.S. inpatient hysterectomies, which account for more than 90% of the procedures, preserved the cervix, compared with just 1.7% a decade earlier, according to federal data.

The cervix is a small, doughnut-shaped mass of tissue at the base of the uterus. Downsides to keeping it include the need to continue regular Pap smears and the possibility of continued menstrual bleeding or spotting, if the surgeon doesn't succeed in removing all of the uterus.

"When you give women the choice, and you tell them the pros and cons, many of them find the idea of keeping the cervix very appealing," says Seth Kivnick, a physician at Kaiser Foundation Hospital in West Los Angeles. Three-quarters of women without cancer choose to keep the cervix when having a hysterectomy at the hospital, he says.

Some researchers believe that for at least some women, the cervix may contribute to sexual pleasure; doctors also say leaving it in place makes it easier to avoid unwittingly shortening the vaginal canal. A 212-patient Finnish study from 1983 found pain upon intercourse pre-hysterectomy was better relieved by a cervix-sparing procedure. A parallel study, involving the same women, found the frequency of orgasms decreased in women who had their cervix removed but not in those who didn't.

Dr. Jamieson, of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, says the orgasm finding didn't reach statistical significance. Also, the study designs were flawed, in part because the women weren't assigned randomly to the different procedures, she says.

Other studies have failed to validate a positive role for sparing the cervix. A 2005 study of 135 women found no difference in sexual functioning or quality of life between women who had the cervix-sparing and regular hysterectomies. "It's not to say that an individual woman may not be in a better place, but on average it's not true," says lead author Miriam Kuppermann, an epidemiologist at the University of California, San Francisco.

One limitation of the research is that various studies, including Dr. Kuppermann's, compared hysterectomies done with a large abdominal incision. Many surgeons pushing the cervix-sparing procedure do a minimally invasive version involving only three or four tiny incisions, which helps shorten recovery times. Removal of both the uterus and the cervix can also be performed minimally invasively, but this option isn't yet widely available. In another type of procedure, called "vaginal hysterectomy," no abdominal incisions are made and the uterus is removed through the vagina; the cervix generally must be removed. Women whose Pap smears recently found lesions that could be pre-cancerous are generally advised to have the cervix removed during a hysterectomy. Some physicians won't leave the cervix in place if a woman tests positive for strains of human papillomavirus that can cause cervical cancer.

A Dip in the Sex Drive, Tied to Menopause

By Jane E. Brody

NY Times Article ; March 31, 2009

Concern about the safety of hormone replacement has all but obscured one of the most pressing concerns for women of a certain age: the effects of menopause on their sex lives. Many are reluctant to ask their doctors a question uppermost in their minds: “What has happened to my desire for sex and my ability to enjoy it?”

With fully a third of their lives ahead of them, but with little or none of the hormones that fostered what may have been a robust sex life, many postmenopausal women experience diminished or absent sexual desire, difficulty becoming aroused or achieving orgasm, or pain during intercourse caused by menopause-related vaginal changes.

Sometimes the reasons for these problems go beyond hormones. Some women may consider themselves less sexually attractive as their bodies change with age, or they have partners who have lost interest in sex or the ability to perform reliably.

But for most postmenopausal women, hormone-related changes are the primary factors that interfere with sexual satisfaction. My friend Linda, for example, who lives in Pittsburgh, was 52 years old and recently married when her vibrant interest in sex suddenly plummeted, leading to a frantic search for a way to restore it.

A more common situation is described by Pat Wingart and Barbara Kantrowitz in their informative book, “Is It Hot in Here or Is It Me?” (Workman, 2006): “You’re not in the mood a lot of the time. Most nights, you just wish your partner would roll over and go to sleep. When you do feel like a little action, it takes forever to get warmed up. Sometimes sex is more painful than pleasurable.”

Common Changes

Unlike Linda, who had an abrupt change in desire, many women report a gradual decline in sexual desire as they age. In a survey of 580 menopausal women conducted by Siecus, the Sexuality Information and Education Council of the United States, 45 percent reported a decrease in sexual desire after menopause, 37 percent reported no change and 10 percent reported an increase.

Although individual experiences certainly vary, “Changes in arousal clearly are associated with menopause,” according to a 2007 article in The Journal of the American Medical Association. The author, Dr. Jennifer E. Potter of Harvard Medical School and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, said physical factors include less blood flow to genital organs, a decrease in vaginal lubrication and a decreased response to touch.

Women can achieve orgasm throughout their lives, but they typically need more direct, more intense and longer stimulation of the clitoris to reach a climax, Dr. Potter noted.

Another common experience is a diminished intensity of orgasm and painful uterine contractions after orgasm, although the women surveyed by Siecus said over all that they remained satisfied with sex.

Yet as Dr. Potter put it, “What might be a satisfying sexual life for one woman may seem woefully inadequate to another,” adding that what a woman expects from her sex life can make a difference. She cited the findings of various large surveys: “Only one-third to one-half of women who report decreased desire or response believe they have a problem or feel distress for which they would like help.”

So what happens to a woman’s body when levels of sex hormones fall?

Although estrogen is a woman’s predominant hormone before menopause, testosterone, produced in women primarily by the ovaries and adrenal glands, is considered the libido hormone for both men and women.

Testosterone levels in women decline by about 50 percent between the ages of 20 and 45, and the amount of testosterone produced continues to decline gradually as women age. While menopause itself has no direct effect on testosterone production, surgical removal of the ovaries can cause an abrupt drop in this hormone and accompanying sexual desire, especially for women who have not gone through natural menopause.

For some women, the increased ratio of testosterone to estrogen that occurs after menopause gives their sex drive a boost, Ms. Wingart and Ms. Kantrowitz point out.

But for most women, the menopausal effects of low levels of estrogen are the primary deterrents to sexual pleasure. In addition to the infamous hot flashes, changes in the vagina and vulva can have serious effects on the sexual experience.

¶With little or no estrogen, vaginal walls become dry, thin and less elastic, causing pain during penetration.

¶Diminished blood flow to the genital area means it can take much longer for a woman to feel aroused.

¶The anticipation of painful uterine contractions with orgasm can be a turnoff.

¶A leakage of urine some women experience during sex can prompt them to avoid it.

Helpful Treatments

Linda, who asked that her last name not be used, said she was more concerned about reviving her sex life than a possible increased risk of hormone-induced cancer or heart disease. A prescription of the drug Estratest, which combines estrogen and testosterone, solved her problem.

But taking estrogen orally is not recommended for women who have had breast cancer or are at high risk for developing it. Also, to protect the uterus against cancer, estrogen should be combined with a progestin.

An alternative that works for some is vaginal application of a little estrogen via a cream, ring or tablet, which keeps the hormone from passing through the liver and diminishes the amount that enters the bloodstream.

Gynecologists concerned about safety are more likely to recommend a non-oil-based lubricant. Besides such popular products as K-Y jelly, Ms. Wingart and Ms. Kantrowitz suggest several longer-lasting products that have an adhesive quality, including Replens, K-Y Long-Lasting Vaginal Moisturizer and Astroglide Silken Secret. The authors said “women who have intercourse regularly seem to generate more lubrication than those who do it less frequently.”

Infrequent intercourse or prolonged periods without it can result in a narrowing of the vagina that can be countered by the use of lubricated vaginal dilators. For women whose sex lives are disrupted by lack of a partner, the authors recommend self-stimulation. Dr. Potter suggested that even for women with partners, a vibrator or small battery-powered vacuum pump can aid in arousal.

While a Viagra-like drug is not yet an option for women, use of the antidepressant bupropion (Wellbutrin at 300 milligrams a day) may improve sexual arousal and satisfaction in women who are not depressed. And Dr. Potter pointed out that remaining physically fit can also help.

Melinda Beck : WSJ Article : February 3, 2009

A muddle of misinformation keeps clouding the debate over hormone-replacement therapy for women.

Last week, millions of women tuned into "The Oprah Winfrey Show" to hear actress Suzanne Somers sympathize with women suffering from what she called "The Seven Dwarfs of Menopause: Itchy, Bitchy, Sleepy, Sweaty, Bloated, Forgetful and All Dried Up." As she's done in her best-selling books, Ms. Somers, age 62, credited a custom-made blend of "bio-identical" hormones with maintaining her youthful zest and told viewers that the hormone debate boils down to a choice between "restoration versus deterioration."

There was little discussion of potential risks of HRT. The compounding pharmacies that make up such custom blends of hormones without oversight by the Food and Drug Administration often claim their products are so natural that they confer the benefits of hormone replacement (from restoring sleep, mood, memory and sexiness to protecting against osteoporosis) without the risks.

Millions of women abandoned menopause hormones after the big Women's Health Initiative trial was halted early in 2002 amid signs that they increased the risk of heart attack and stroke. A growing number of experts now believe that the women in the WHI -- average age 63 -- do not reflect the typical women entering menopause, and that the same risks may not apply to younger women.

Even so, women seeking safer alternatives have turned to "bio-identicals" -- a trend that worries mainstream medical groups. "Women who were afraid after the WHI, as were their doctors, are going to alternative approaches that have little or no scientific information behind them," says Margaret Weirman, a professor of medicine at the University of Colorado Denver and a spokeswoman for the Endocrine Society, a professional organization devoted to hormone research. "These women may be putting themselves at much higher levels of risk."

Amid all the confusion, here are seven things women should know about the HRT debate now:

1) 'Bio-identical' hormones are available in FDA-approved forms.

Though many experts dismiss "bio-identical" as a meaningless term, proponents use it to mean hormones with the same molecular structure as those that women's bodies make. The main one lost at menopause is estradiol, which affects functions throughout the female body, from skin to bones, hearts and brains. Chemically equivalent estradiol is available in many FDA-approved pills, patches, creams and gels from traditional drug companies, generally made from the exact same plant sources that compounding pharmacies use. What's more, the FDA-approved varieties are covered by insurance, unlike compounded blends that can cost hundreds of dollars a month.

A growing number of doctors prescribe these estradiol-based products instead of Premarin, the estrogen made from horse urine that was used in the WHI. Many also prefer natural progesterone, available in FDA-approved Prometrium, to the synthetic form that was used in the WHI. But there is little evidence comparing one HRT variety against another.

2) Hormones from compounding pharmacies aren't safer than conventional HRT.

Compounded drugs don't carry warnings or list side effects on their labels, but that's because they are not made under FDA scrutiny. In fact, they can vary greatly in strength and potency and little is known about how they release active ingredients over time. "We don't know if it comes out in peaks and valleys or continuously," says Dr. Weirman. "Some people may be getting very high doses, and some people may be getting very little or none."

The International Academy of Compounding Pharmacists contends that its members perform a valuable service in making drugs and strengths that aren't commercially available, that they are providing women with freedom of choice in health-care decisions and that much of the criticism is coming from groups funded by makers of traditional HRT.

3) Don't trust saliva tests.

Some compounding pharmacies use saliva tests to monitor women's hormone levels and develop custom blends. But many experts say such tests (which can cost hundreds of dollars) are unreliable and lack uniform standards.

Blood tests are more accurate -- but monitoring how women feel is just as key. Many doctors believe that HRT should be used mainly to treat actual symptoms such as hot flashes, mood swings, sleep problems, foggy thinking and other symptoms, rather than arbitrary blood levels since individual ranges vary widely. FDA-approved estradiol products are available in a wide variety of strengths that can be tapered as a woman's symptoms change.

Hormone Options

FDA-approved products with estradiol:

- Alora

- Climara

- Vivelle

- Estraderm

- Estrace

- Estrogel

- Prometrium

- Crinone

There's a growing consensus that the risks and benefits are different for younger and older women, and that for women who start HRT shortly after menopause, the benefits may outweigh the risks. Women in the WHI who were 20 years past menopause had a 71% higher risk of heart attack on estrogen and progesterone than those taking placebos, but women closer to menopause had an 11% lower risk of heart problems. One theory is that estrogen helps keep healthy blood vessels supple, but make atherosclerosis worse once it has set in.

Similarly, HRT seems to help preserve thinking ability when started just after menopause, but it may hasten the progression of pre-existing memory problems when started later in life, writes JoAnn E. Manson, a Harvard Medical School professor who was a lead investigator on both the WHI and the long-running Nurses' Health Study, in her new book, "Hot Flashes, Hormones and Your Health."

HRT was associated with a lower risk of fractures and colorectal cancer regardless of age. The WHI did not assess whether HRT improved quality-of-life issues such as mood, sleep and hot flashes. Women experiencing such symptoms were excluded from the study on the grounds that immediate effects might prompt some to guess whether they were in the control or placebo group.

5) The increased risk of breast cancer appears related to progesterone rather than estrogen.

Women taking both estrogen and progesterone in the WHI had eight more cases of breast cancer per 10,000 than the control group; women taking estrogen alone had six fewer cases. Women who still have a uterus need some progesterone to guard against uterine cancer, but many doctors now try to give the lowest dose possible to prevent a build-up of uterine lining.

6) Estrogen applied to the skin, in patch, cream or gel form, may have a lower risk of blood clots and strokes than in pill form.

A large study in France published in the Lancet found that women taking estrogen in pill form were three times as likely to develop blood clots than non-users, while women using the estradiol patch had no increased risk. But more study is needed to determine this conclusively.

7) Stay tuned.

Several of these new theories are being tested in another trial called KEEPS (for Kronos Early Estrogen Prevention Study) that is comparing 720 newly menopausal women on oral Premarin, an estrogen patch or placebo. Investigators will monitor their arteries, as well as quality-of-life aspects like mood, fatigue, sleep, bone health and cognition.

In the meantime, women entering menopause should discuss all the risks and benefits with their doctors, as well as their symptoms, health and family history, and make an individual, informed decision.

For Some in Menopause, Hormones May Be Only Option

By Tara Parker-Pope : NY Times : August 15, 2011

For women hoping to combat the symptoms of menopause with nonprescription alternatives like soy and flaxseed supplements, recent studies have held one disappointment after another.

Last week, a clinical trial found that soy worked no better than a placebo for hot flashes and had no effect on bone density. That followed a similar finding about hot flashes from a clinical trial of flaxseed.

“We wish we could have told women that, yes, they work,” said Dr. Silvina Levis, director of the osteoporosis center at the University of Miami, who led the soy study. “Now we have shown that they don’t.”

Before 2002 women were routinely treated with the prescription hormones estrogen and progestin, which rapidly fell out of favor after the landmark Women’s Health Initiative study showed that older women who used them had a heightened risk of heart attacks and breast cancer.

But now some doctors are arguing that those risks do not apply to the typical woman with menopause symptoms, and even some longtime critics of hormone treatment are suggesting that it be given another look for women suffering from severe symptoms.

Study after study has shown that many nondrug treatments — black cohosh, red clover, botanicals, and now soy and flaxseed — simply don’t work. Prescription medicines, including antidepressants, the blood pressure drug clonidine and the seizure drug gabapentin may have some benefit, but many women cannot tolerate the side effects.

“There is no alternative treatment that works very well, whether it’s a drug or over-the-counter herbal preparation,” said Dr. Deborah Grady, associate dean for clinical and translational research at the University of California, San Francisco.

About 75 percent of menopausal women experience hot flashes. Depending on the woman, symptoms can be mild, occurring only a few times a week, or moderate, occurring several times a day. Many women with mild to moderate symptoms cope without needing further treatment. But about a third of women have severe symptoms, experiencing 10 to 20 hot flashes day and night that disrupt their workdays and interfere with sleep.

While doctors often reassure women that it will all be over in just a few years, a May report in the journal Obstetrics and Gynecology found that during one long-term study of women, menopausal hot flashes recurred for some women, for 10 years or more.

A hot flash is usually described as a sudden warmth first felt in the face and neck. Hot flashes can turn a woman’s face red and lead to excessive sweating and then chills. On the Web site MinniePauz.com, women describe feeling lightheaded and dazed, with heart palpitations and anxiety.

“Whoosh, a rush of heat originating from the core of your body,” is how one woman put it. “Hair goes lank and you know that even if you stripped naked and ran down the high street waving your arms to fan your body, well you still wouldn’t get cool because the heat is inside you, not outside.”

The exact cause of hot flashes is not known, but it is believed that menopause disrupts the function of the hypothalamus, which is essentially the body’s thermostat. As a result, even small changes in body temperature that would normally go unnoticed can set off hot flashes.

Among prescription drug treatments, the most effective may be antidepressants, including Effexor, Paxil and Pristiq, which have been shown to reduce hot flashes by as much as 60 percent, doctors say. Antidepressants are particularly useful for women with breast cancer or blood-clot disorders who do not have the option of taking a hormone drug.

But some doctors say they are frustrated by the message given to many women that they must seek an alternative treatment to prescription hormones. Dr. Holly Thacker, director of the center of specialized women’s health at the Cleveland Clinic, said that for many women the benefits of effective hormone treatment would outweigh the risks and that they should not be scared off from considering the drugs.

“It would be like telling someone with insulin-dependent diabetes that they should try to use other things besides insulin,” she said. “I see women look to alternative agents and coming in with bags of things, and they have no idea what they are putting into their body. There has been so much misinformation, and they are confused.”

Dr. Grady, a longtime critic of widespread hormone use, said doctors and women appeared to be less tolerant of risks associated with hormones than of those with other drugs, even though menopause symptoms can be just as intolerable as migraine pain or other health problems.

“Somehow we’re quite willing to take a migraine drug with its associated adverse effects because it works so well, but we’re not willing to take estrogen,” she said. “We worry about the adverse effects associated with estrogen, but the important adverse effects are reasonably uncommon.

“The question is whether a woman is willing to trade off that risk for a very effective treatment for symptoms that are otherwise ruining her life.”

Subtle Science: Heading Off Heart Attacks in Women

By Melinda Beck

WSJ Article : November 25, 2008

Men's and women's hearts are different -- in ways that doctors are still working to understand.

A recent government report adds more mystery: According to the federal Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, or AHRQ, women are far more likely than men to be hospitalized for chest pain for which doctors can't find a cause.

In 2006, the latest data available, 477,000 women were discharged from U.S. hospitals with a diagnosis of nonspecific chest pain, compared with 379,000 men. That diagnosis is often given to patients who are admitted for a possible heart attack that turns out not to be one.

Heart disease is the No. 1 killer of both sexes, claiming more lives each year than all cancers combined. More women than men have died from heart disease in the U.S. every year since 1984, and they are twice as likely as men to die after a heart attack, according to the National Coalition for Women with Heart Disease.

But heart attacks often look different in women than men. While both frequently report chest pain, pressure or tightness, women more often have subtle signs instead, including dizziness, nausea, breathlessness, aches in the back, shoulders or abdomen, sudden weakness or fatigue or an overwhelming feeling of doom. A 2003 study found that 95% of women who had heart attacks started feeling some of those symptoms a month or more before.

"Women are very into their bodies -- they know when they aren't feeling well," says Nieca Goldberg, medical director of New York University's Women's Heart Program. "That's the time to call your doctor, when there's still time to prevent a heart attack."

Could some of those nonspecific chest pains in the AHRQ report have been early warning signs? There's no way of knowing, since the statistics don't track whether patients returned with a heart attack later.

Warning for Women

Chest pain is a common symptom in heart attacks, but women may instead have:

- Pressure or pain in shoulders, back, jaw or arms

- Dizziness or nausea

- Sudden fatigue or weakness

- Shortness of breath

- Unexplained anxiety

But even when women do have such diagnostic tests, doctors are less likely to find CAD. "Women with chest pain are much more likely to have normal coronary arteries," says Rita F. Redberg, director of Women's Cardiovascular Services at the University of California -- San Francisco School of Medicine. "The truth is, we don't always find out what causes it."

One theory is that some chest pain in women may be due to microvascular disease -- blockages in tiny vessels that can't be seen on an angiogram. Such blockages are also too small to be opened with stents or angioplasty, but can be treated with beta blockers and nitroglycerine.

Given the growing awareness that heart attacks present differently in women, the AHRQ data may indicate that doctors are treating women with chest pain more proactively than they used to.

"Women's chest pain is increasingly taken more seriously -- even if it's atypical -- so doctors may have a lower threshold for admitting them," says cardiologist Edmund M. Herrold, a professor of medicine at the State University of New York-Downstate Medical Center in Brooklyn. "I think that's a good thing. In the past, women who should have been admitted were being sent home."

Should women think twice about getting help if they're having chest pain? "We're always trying to draw that line fine -- not wanting people to ignore symptoms, but not thinking it's a heart attack everytime they get a twinge," says Dr. Redberg.

Studies show that women wait longer than men before going to the hospital -- in part because the symptoms may be subtle, and in part because they don't want to "bother" doctors if nothing's wrong. But two-thirds of women who have heart attacks never make it to the hospital.

If you have any of the symptoms for more than a few minutes, seek help quickly. "Don't sit home and wonder," says Dr. Goldberg, who sometimes has to beg patients who call her in the middle of the night to go to the hospital.

She also suggests calling 911 rather than going on your own: "You'll get taken care of faster in the emergency room if you arrive by ambulance. The hospital can call the doctor for you."

Beyond Hysterectomy: Alternative Options for Heavy Bleeding

By Carolyn Sayre

NY Times Article : October 3, 2008

In Brief:

Heavy or prolonged bleeding affects nearly one in five women ages 35 to 49.

Hysterectomy was the treatment of choice 20 years ago, but new options like the Mirena intrauterine device and medications often make surgery unnecessary.

Today, many women with menorrhagia continue to suffer because they are unaware of new treatment options.

It’s rare to find a woman who has never had any trouble with her period. For most, though, the hassles are fairly minor — irritability, mild cramping and the occasional surprise visit. But for the nearly one in five women ages 35 to 49 who suffer from menorrhagia — heavy or prolonged bleeding — their menstrual cycle puts life on hold every month.

“It controlled my life,” said Stefanie Haase, 37, an X-ray technician from Sodus, N.Y., who started bleeding uncontrollably two years ago because of a large fibroid. “I had to carry an extra set of clothes with me at all times. I couldn’t drive without messing up the car, or plan a vacation. My life revolved around my period.”

Twenty years ago, women like Ms. Haase did not have many options. For the nearly 40 percent of women whose abnormal bleeding stemmed from anatomical problems like fibroids and polyps, an invasive surgical procedure to remove the noncancerous growths, called a myomectomy, was often helpful but did not always stop the bleeding. For the majority of patients, the outlook was pretty unpleasant. High-dose hormones caused a host of side effects like rapid weight gain. A procedure called dilation and curettage, or D&C, which scraped away the lining of the uterus, typically failed to stop the bleeding for more than a few months.

Ms. Haase would have quickly found herself out of options and, like many women living with menorrhagia back then, her last resort would likely have been a hysterectomy — major surgery to remove the uterus and sometimes other reproductive organs as well. But thanks to new treatments and techniques, all that has changed.

“Women no longer need to choose between suffering and major surgery,” said Dr. Glenn Schattman, a reproductive surgeon and associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the New York Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Medical College of Cornell. “Today, the key is avoiding major surgery, and thankfully, the overwhelming majority of patients can now be treated with minimally invasive procedures or medication.”

The changes began in 1987, when the Food and Drug Administration approved a laser that could destroy the lining of the uterus by heating it. The laser outpatient procedure that became known as endometrial ablation was a retreat from the finality of a hysterectomy, which not only removes major organs but, back then, also required up to two months of recovery time.

A few years later, physicians began to refine the procedure, developing more sophisticated techniques like endometrial resection, which removes the uterine lining entirely.

“Women who lived 20 years ago were pushed onto a track with very few off-ramps,” said Dr. Morris Wortman, director of the Center for Menstrual Disorders & Reproductive Choice in Rochester. “Endometrial ablation changed that by obviating the need for hysterectomy. It gave women choices.”

Dr. Wortman notes that endometrial ablation stops bleeding in nearly half of women and significantly reduces bleeding in another 40 percent.

But like most procedures, endometrial ablation and resection also have downsides. About 15 percent of patients still need a hysterectomy, and while the uterus remains intact after the endometrial procedures, a woman’s chance of conception is destroyed.

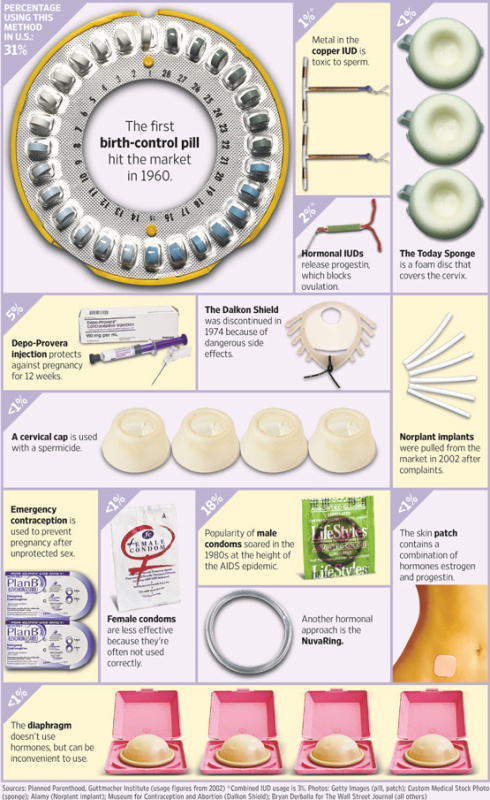

Medical therapies now help eliminate some of the fertility concerns. In the early ’90s, low-dose birth control pills began to be prescribed for women with heavy bleeding who did not have structural problems. Perhaps the biggest breakthrough came in 2001, when the F.D.A. approved Mirena, an intrauterine birth control device that lightens bleeding in more than 80 percent of women.

Today, most physicians consider the fertility-preserving Mirena IUD to be the first-line treatment for heavy bleeding in women with normal anatomy.

“It works beautifully,” said Dr. Linda Bradley, director of hysteroscopic services for the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the Cleveland Clinic’s Center for Menstrual Disorders and Fibroids. “Women who take it either don’t get their period or bleed very lightly.”

That was certainly the case for Sheila Woodruff, 45, of Cleveland, who started using the Mirena IUD last spring. After two years of heavy bleeding that lasted up to 10 days every month and caused her to change her clothes every couple hours, she finally had enough.

The Mirena IUD, she said, “was unbelievable.”

“My period magically became normal again.”

In a small percentage of women, the device causes side effects like spotting or abdominal pain and may need to be removed.

And for women with anatomical problems like fibroids and polyps, minimally invasive procedures like laparoscopic myomectomy have reduced recovery time significantly. And uterine fibroid embolization, a nonsurgical technique that shrinks or kills the growths by cutting off their blood supply, has helped certain patients with structural problems avoid surgery altogether.

Now that alternative treatments to hysterectomy have been developed, physicians say their biggest challenge is raising awareness and acceptance among women, many of whom still fear that major surgery is their only option.

“I can’t believe how many women are essentially bedridden during their periods for a year or two before they see a doctor,” Dr. Schattman said. “They are still scared that heavy bleeding means they will need a hysterectomy.”

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 20 million women now living in the United States have had a hysterectomy. “That number should be lower,” Dr. Wortman said. “And it would be if more women understood all of their options.”

Despite the fact that many physicians say the Mirena device is safe and remarkably effective, women who remember the infamous side effects of the Dalkon Shield, a popular IUD used in the ’70s, still shy away from using it. What’s more, techniques like endometrial ablation and resection have only really begun to catch on in the last 10 years or so as technological advancements have made it easier for less-specialized gynecologists to perform the procedures.

Ms. Haase, for one, waited it out for nearly two years before she underwent surgery. Unlike most patients with fibroids, she underwent both a myomectomy and endometrial resection to stop her bleeding.

“My mother had a hysterectomy when she was 33, so I figured that was my fate,” she said. “But there are so many options out there. I only wish I had known that two years ago.”

More doctors are challenging the convention of removing the cervix during a hysterectomy

By Laura Johannes

WSJ Article : February 24, 2009

For decades, surgeons performing a hysterectomy, or removal of the uterus, typically cut out the woman's cervix as well. If it were left in, doctors reasoned, it could develop cancer.

Now, a growing number of gynecologists are marketing "cervix-sparing" hysterectomies if cancer isn't present. The chance of cervical cancer is fairly low, and Pap-smear screening will catch most cases, these doctors say. And leaving the cervix untouched reduces the risk of surgical damage to the bladder and nearby nerves, and may even allow a woman to enjoy a better sex life long term, say doctors who perform these procedures.

Not so fast, argues the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. The influential nonprofit doctors' group argued in a 2007 report that evidence was lacking that sparing the cervix improves one's sex life or bladder function. And if a growth develops, removing the cervix alone carries higher risk, including infection, than a hysterectomy, the group says. "It's not appropriate for surgeons to recommend it as a superior technique," says Denise Jamieson, chairman of the committee that wrote the report.

Cutting Less

More doctors are challenging the convention of removing the cervix during a hysterectomy. Here's why:

- Pap smears have sharply reduced the incidence of cervical cancer.

- Sparing the cervix reduces the risk of bladder damage.

- Some doctors say it may improve sexual function.

Now the tide appears to be turning. In 2006, 9.7% of U.S. inpatient hysterectomies, which account for more than 90% of the procedures, preserved the cervix, compared with just 1.7% a decade earlier, according to federal data.

The cervix is a small, doughnut-shaped mass of tissue at the base of the uterus. Downsides to keeping it include the need to continue regular Pap smears and the possibility of continued menstrual bleeding or spotting, if the surgeon doesn't succeed in removing all of the uterus.

"When you give women the choice, and you tell them the pros and cons, many of them find the idea of keeping the cervix very appealing," says Seth Kivnick, a physician at Kaiser Foundation Hospital in West Los Angeles. Three-quarters of women without cancer choose to keep the cervix when having a hysterectomy at the hospital, he says.

Some researchers believe that for at least some women, the cervix may contribute to sexual pleasure; doctors also say leaving it in place makes it easier to avoid unwittingly shortening the vaginal canal. A 212-patient Finnish study from 1983 found pain upon intercourse pre-hysterectomy was better relieved by a cervix-sparing procedure. A parallel study, involving the same women, found the frequency of orgasms decreased in women who had their cervix removed but not in those who didn't.

Dr. Jamieson, of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, says the orgasm finding didn't reach statistical significance. Also, the study designs were flawed, in part because the women weren't assigned randomly to the different procedures, she says.

Other studies have failed to validate a positive role for sparing the cervix. A 2005 study of 135 women found no difference in sexual functioning or quality of life between women who had the cervix-sparing and regular hysterectomies. "It's not to say that an individual woman may not be in a better place, but on average it's not true," says lead author Miriam Kuppermann, an epidemiologist at the University of California, San Francisco.

One limitation of the research is that various studies, including Dr. Kuppermann's, compared hysterectomies done with a large abdominal incision. Many surgeons pushing the cervix-sparing procedure do a minimally invasive version involving only three or four tiny incisions, which helps shorten recovery times. Removal of both the uterus and the cervix can also be performed minimally invasively, but this option isn't yet widely available. In another type of procedure, called "vaginal hysterectomy," no abdominal incisions are made and the uterus is removed through the vagina; the cervix generally must be removed. Women whose Pap smears recently found lesions that could be pre-cancerous are generally advised to have the cervix removed during a hysterectomy. Some physicians won't leave the cervix in place if a woman tests positive for strains of human papillomavirus that can cause cervical cancer.

A Dip in the Sex Drive, Tied to Menopause

By Jane E. Brody

NY Times Article ; March 31, 2009

Concern about the safety of hormone replacement has all but obscured one of the most pressing concerns for women of a certain age: the effects of menopause on their sex lives. Many are reluctant to ask their doctors a question uppermost in their minds: “What has happened to my desire for sex and my ability to enjoy it?”

With fully a third of their lives ahead of them, but with little or none of the hormones that fostered what may have been a robust sex life, many postmenopausal women experience diminished or absent sexual desire, difficulty becoming aroused or achieving orgasm, or pain during intercourse caused by menopause-related vaginal changes.

Sometimes the reasons for these problems go beyond hormones. Some women may consider themselves less sexually attractive as their bodies change with age, or they have partners who have lost interest in sex or the ability to perform reliably.

But for most postmenopausal women, hormone-related changes are the primary factors that interfere with sexual satisfaction. My friend Linda, for example, who lives in Pittsburgh, was 52 years old and recently married when her vibrant interest in sex suddenly plummeted, leading to a frantic search for a way to restore it.