- RETIREMENT ANNOUNCEMENT

- HOME PAGE

- "MYCHART" the new patient portal

- BELMONT MEDICAL ASSOCIATES

- MOUNT AUBURN HOSPITAL

- EMERGENCIES

- PRACTICE PHILOSOPHY

- MY RESUME

- TELEMEDICINE CONSULTATION

- CONTACT ME

- LAB RESULTS

- ePRESCRIPTIONS

- eREFERRALS

- RECORD RELEASE

- MEDICAL SCRIBE

- PHYSICIAN ASSISTANT (PA)

- Medicare Annual Wellness Visit

- Case management/Social work

- Quality Care Measures

- Emergency closing notice

- FEEDBACK

- Talking to your doctor

- Choosing..... and losing a doctor

- INDEX A - Z

- ALLERGIC REACTIONS

- Alternative Medicine

- Alzheimer's Disease

- Bladder Problems

- Blood disorders

- Cancer Concerns

- GENETIC TESTING FOR HEREDITARY CANCER

- Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

- Controversial Concerns

- CPR : Learn and save a life

- CRP : Inflammatory marker

- Diabetes Management

- Dizziness, Vertigo,Tinnitus and Hearing Loss

- EXERCISE

- FEMALE HEALTH

-

GASTROINTESTINAL topics

- Appendicitis

- BRAT diet

- Celiac Disease or Sprue

- Crohn's Disease

- Gastroenterologists for Colon Cancer Screening

- Colonoscopy PREP

- Constipation

- Gluten sensitivity, but not celiac disease

- Heartburn and GERD

- Hemorrhoids and Anal fissure

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- NASH : Non Alcoholic Steato Hepatitis

- FEET PROBLEMS

- HEART RELATED topics

-

INFECTIOUS DISEASES

- Antibiotic Resistance

- Cat bites >

- Clostridia difficile infection - the "antibiotic associated germ"

- CORONA VIRUS

- Dengue Fever and Chikungunya Fever

- Food borne illnesses

- Shingles Vaccine

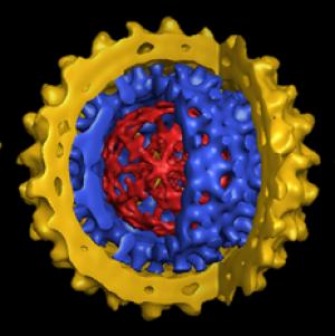

- Hepatitis B

- Hepatitis C

- Herpes

- Influenza

- Helicobacter pylori - the "ulcer germ"

- HIV Screening

- Lyme and other tick borne diseases

- Measles

- Meningitis

- MRSA (Staph infection)

- Norovirus

- Sexually Transmitted Diseases

- Shingles (Herpes Zoster)

- Sinusitis

- West Nile Virus

- Whooping Cough (Pertussis)

- Zika virus and pregnancy

- INSURANCE related topics

- KIDNEY STONES

- LEG CRAMPS

- LIBRARY for patients

- LIFE DECISIONS

- MALE HEALTH

- Medication/Drug side effects

- MEDICAL MARIJUANA

- MENTAL HEALTH

- Miscellaneous Articles

-

NUTRITION - EXERCISE - WEIGHT

- Cholesterol : New guidelines for treatment

- Advice to lower your cholesterol

- Cholesterol : Control

- Cholesterol : Raising your HDL Level

- Exercise

- Food : Making Smart Choices

- Food : Making Poor Choices

- Food : Grape Fruit and Drug Interaction

- Food : Vitamins, Minerals and Supplements

- Omega 3 fatty acids

- Vitamin B12 deficiency

- Vitamin D

- Weight Loss

- ORTHOPEDICS

- PAIN

- PATIENTS' RIGHTS

- SKIN

- SLEEP

- SMOKING

- STROKE

- THYROID

- SUBSTANCE ABUSE

- Travel and Vaccination

- TREMOR

- Warfarin Anticoagulation

- OTHER STUFF FOLLOWS

- Fact or Opinion?

- Hippocratic Oath

- FREE ADVICE.......for what its worth!

- LAUGHTER.....is the best medicine

- Physicians Pet Peeves

- PHOTO ALBUM - its not all work!

- Cape Town, South Africa

- Tribute page

- The 100 Club

- Free Wi-Fi

Hepatitis

Hepatitis B

Weighing the Options for Hepatitis B

By Peter Jaret : NY Times Article : February 14, 2009

IN BRIEF:

Despite the development of an effective vaccine, hepatitis B infection remains a serious health problem worldwide.

Adults exposed to hepatitis B typically fight off the infection; infants and children almost always develop chronic infections.

People can carry hepatitis B virus without having symptoms, even though the infection may be damaging the liver.

Although not everyone infected develops serious complications, hepatitis B can lead to liver disease and cancer.

With seven treatments approved for hepatitis B, doctors can successfully control the infection in most patients.

The decisive scientific battle against hepatitis B has been won. Thanks to a vaccine approved in the 1980s, transmission of this potentially deadly virus can now be stopped. In countries where the vaccine is widely used, the series of three shots has almost completely halted the spread from infected mothers to their infants, one of the most common routes of transmission, and the one most likely to lead to chronic infection and serious liver disease. The vaccine has also significantly reduced transmission between adults.

Still, an estimated 1.3 million Americans and 400 million people worldwide harbor the virus. Chronic infection with hepatitis B can lead to cirrhosis, or scarring of the liver, and liver failure. Those infected with the virus have a 100-fold higher than average risk of liver cancer.

In the United States, most new cases occur in recent immigrants who were exposed as infants or young children in their native countries. Many don’t know they harbor the virus. A 2005 screening program of Asians and Pacific Islanders in New York City, for example, documented a 15 percent infection rate. One in three of those found to carry the virus were unaware they had been infected.

“These are hard populations to reach,” said Dr. Adrian Di Bisceglie, chief of hepatology at Saint Louis University School of Medicine. “Some are illegal immigrants who are afraid to go to the doctor. Others are self-employed first-generation immigrants who don’t want to get involved in the health care system.”

To reach more chronic carriers, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention issued new guidelines in September recommending testing for everyone born in regions where hepatitis B infects 2 percent or more of the population. That includes large swaths of Asia, the Pacific Islands, Africa, Eastern Europe and the Middle East, where the virus still runs rampant. Others at increased risk are men who have sex with men and intravenous drug users. Patients receiving chemotherapy or immunosuppressive drugs should also be tested; dormant infections can flare up dangerously when the immune system is suppressed.

For those already infected, the prognosis has brightened considerably with the approval of a succession of new and more effective drugs. The first drug used against the virus, interferon, has been supplanted by a longer-lasting version, called pegylated interferon, or peginterferon. In addition, six antiviral drugs, called nucleoside and nucleotide analogs, have been approved.

“Thirty years ago there was nothing we could offer these patients,” said Dr. Emmet B. Keeffe, chief of hepatology at Stanford University School of Medicine. “Today we can control the infection in a majority of patients.”

The most striking evidence comes from waiting lists for liver transplants, long the last-resort treatment for patients infected with hepatitis B who develop severe liver disease. Since 2000, the number of Americans registered for liver transplantation as a result of hepatitis B infection has dropped by 37 percent, according to a study by Dr. W. Ray Kim, a hepatitis expert at the Mayo Clinic College of Medicine.

Encouraging news also emerged from a landmark 2004 study in Taiwan that tested an antiviral drug called lamivudine against a placebo in patients with advanced disease. The trial was halted early because patients receiving the medication improved so much that the investigators felt obliged to switch all the volunteers to the active drug.

“This was the definitive study,” Dr. Di Bisceglie said. “We knew antiviral drugs could suppress virus levels and improve liver function. This showed that treatment also lowered rates of liver cancer and liver failure.”

Even with an arsenal of seven drugs, deciding when to start treatment — and when to stop it — is surprisingly complicated.

“The problem with hepatitis B infection is that the natural history of the disease is so variable,” said Dr. Nancy Reau, assistant professor at the University of Chicago Medical Center. When adults are exposed to the virus, they almost always fight it off successfully on their own. When infants are infected, however, their immature immune systems don’t recognize the invader, which almost always goes on to cause chronic infection. A decades-long period may follow during which the virus continues to replicate but causes little damage.

Then, for reasons not well understood, the immune system becomes triggered and begins to attack the virus. The battle itself accelerates damage to the liver, increasing the risk of cirrhosis, liver failure and liver cancer.

Yet a majority of patients with hepatitis B, again for unknown reasons, carry the virus without ever developing these serious consequences. Unfortunately, doctors cannot reliably predict who is at risk for trouble. “Our crystal ball just isn’t very good yet,” Dr. Reau said.

Physicians wouldn’t need a crystal ball if they had a drug that reliably cured the infection. But in most patients, the available drugs suppress the virus but do not eliminate it. Patients often have to stay on medication for years, even indefinitely.

“Obviously we don’t want to start patients on drugs if they don’t need them,” Dr. Di Bisceglie said. “And because the virus can develop resistance to antiviral drugs we have, we don’t want to start treating patients before they really need it. And the drugs are expensive.”

Deciding when to stop treatment can be equally difficult. In some patients, treatment suppresses the virus to undetectable levels, and once the drug is stopped, the infection remains quiet. But in others, the virus can flare up again after treatment ends, sometimes causing rapid liver damage.

Since some of the drug treatments are so new, and the course of hepatitis B so long, researchers are only beginning to answer questions about optimal long-term treatment. Still, helpful insights have emerged. Patients with hepatitis B who test positive for a protein in the blood called e-antigen appear to have the best shot at going off treatment without a flare-up. Those with e-antigen negative infections, on the other hand, are likely to need to be on therapy indefinitely. Researchers are also gaining insight into which patients will do best on peginterferon versus the newer antiviral drugs.

“Ironically, the more we learn, the more complicated our clinical decisions have become,” Dr. Reau said. “The field is moving so fast that what we did two years ago is already fairly obsolete.”

For people infected with hepatitis B, the rapid progress in research means having to weigh complicated options. But it also means a far greater chance that the virus can be kept at bay for a lifetime.

5 Things to Know

The Silent Threat of Hepatitis B

By Peter Jaret

Dr. Nancy Reau is an assistant professor of medicine at the University of Chicago’s Center for Liver Disease, where she specializes in treating hepatitis. Here are five things she says everyone should know about hepatitis B.

Hepatitis B is a silent threat.

People with chronic infections may feel fine for a long time, even as the virus is causing damage to the liver. Recent evidence shows that during the immune tolerant phase, when most researchers had assumed the virus was quiet, the liver may be sustaining injury. By the time symptoms appear, liver damage may be advanced. That’s why it is so important to be tested if you have any reason to think you might have been exposed.

People infected with hepatitis B should be tested for hepatitis C and H.I.V.

Both of these viruses can be transmitted via routes that are similar to hepatitis B. Co-infection raises the risk of complications. In addition, many doctors encourage people with hepatitis B infection to be vaccinated against hepatitis A to protect their livers from additional damage. Hepatitis A is typically transmitted in contaminated water or food.

Family members and close contacts of people infected with hepatitis B should be tested for the virus.

If they have not been exposed to it, they should be vaccinated.

Not every person infected with hepatitis B needs to start treatment right away.

Many people live with the virus and never develop serious symptoms. Most doctors counsel patients to wait until liver function tests and a biopsy show signs that the virus is beginning to cause damage. By waiting, doctors can limit the amount of time patients need to be treated and lower the risk that drug-resistant viruses will emerge.

Current drugs are very effective at controlling the virus and preventing damage.

And because the liver can regenerate itself, some patients with advanced disease may see their condition improve significantly after beginning treatment.

Expert Q & A

Tailoring Treatment For Hepatitis B

By Peter Jaret

Dr. Marion G. Peters is professor of medicine and director of hepatology research at the University of California, San Francisco. She has been chairwoman of the AIDS Clinical Trial Group Hepatitis Committee and currently conducts research on the immunology of chronic liver disease.

Q: What makes hepatitis B such a complicated disease to treat?

A: Unlike other liver diseases, hepatitis waxes and wanes. The disease can be inactive one year, active the next and then inactive again. So you have to constantly monitor patients who are chronically infected with hepatitis B. And then based on what you find, you have to decide when to treat them. We can’t have a one-size-fits-all approach to hepatitis B, because every individual is different.

Q: Why not treat everyone who is infected?

A: If we could eliminate the virus, we would. But the drugs we have suppress the virus and often have to be given over a long period of time, in some cases indefinitely. So we don’t want to treat someone whose disease is inactive. And we don’t want to start someone on an antiviral drug before they really need it. Nearly all the drugs we have available have some resistance. We don’t want to put a young person on a drug they don’t need and then have the virus develop resistance, so that when they do need the drug it may no longer work.

Q: How do you decide when to treat someone with hepatitis B?

A: The first thing I do is take a full history and physical and do blood tests to see if there is inflammation in the liver, which is measured by liver enzymes. Another test measures how much virus there is in the blood. I usually do an ultrasound as well, to assess the condition of the liver.

If the liver appears normal and the liver enzymes are normal, then the disease is inactive, and there’s no reason to treat.

At the other end of the spectrum are people who obviously have cirrhosis, or scarring of the liver, based on a clinical examination or an imaging study, and whose liver function tests are abnormal. Those are people we definitely want to begin treating, to avoid further damage to the liver. Generally, if they have active disease, I do a liver biopsy to see how severe the liver disease is.

Q: Are there instances when you’re not sure whether to start treatment?

A: That’s the challenge. Many people fall in between those two ends of the spectrum. They may have high levels of the virus in their blood but normal or only very slightly elevated liver enzymes. Or they may have intermediate levels of virus and a little bit of inflammation but not much. That’s where the controversy lies, whether to start such patients on treatment or wait.

If I’m unsure, if a patient doesn’t quite fit into one pigeonhole or another, I may recommend a biopsy to help sort out whether to treat or not. The decision is complicated by the fact that the more time patients remain with active disease, the higher their risk of developing liver cancer, which of course we don’t want to happen.

Q: If you decide to wait, how frequently do you monitor the patient?

A: All patients who have hepatitis B virus need to be monitored. How often and what tests we use really depend on the patient’s situation. A patient whose disease is inactive might be monitored every three months for a year and then every six months after that. A patient with some sign of liver problems but not enough to begin treatment should be monitored more often. Monitoring is very important, because we don’t want the patient to progress to cirrhosis or liver cancer.

Q: Can people have chronic hepatitis B and never develop problems?

A: The natural history depends to a great extent on whether people are infected as infants or as adults. About one in three or four people who acquire hepatitis B at birth will die of liver cancer or cirrhosis without monitoring and treatment. Over all, two out of three patients who have inactive disease do not progress to more serious disease. But it is not possible to determine who will progress and who will develop liver cancer without monitoring. That’s why it’s sometimes so difficult to know when to treat a patient.

Q: With seven drugs available, how do you decide which to use?

A: The first drug approved for hepatitis B was interferon, which we still use. But interferon is a tough drug to take because of its side effects, which include flu-like symptoms, muscle aches and pains, and some psychiatric symptoms. Only about one-third of patients respond to interferon. Still, in a young patient I might encourage them to take interferon because then you can save the other drugs for later if necessary.

The other drugs are called nucleotides or nucleosides, and there are a variety of factors that go into choosing the best one. There are several we don’t use much anymore because the virus develops resistance too quickly. And if a patient has developed resistance, then we’ll need to use a different drug. In some cases, especially after liver transplantation, we use a cocktail of antiviral drugs.

Q: How long do patients need to stay on the drugs?

A: That’s the big unknown. With hepatitis B, there are two types of infection. One is called e-antigen negative, and the other is e-antigen positive disease.

E-antigen positive hepatitis we can treat until they get a response and then consolidate the response with one more year of therapy. When we stop, in about 80 percent of patients, the virus remains inactive. These patients aren’t cured, but we’ve stopped the disease from progressing.

But with e-antigen negative hepatitis B, even if you treat patients for a few years and then stop, the disease will typically reactivate. So the problem is, when we put a patient with e-antigen negative disease on treatment, we’re in for the long-term. How long is long term? No one knows. We think it’s at least five years. But we don’t know.

Q: Are there unwanted side effects to the antiviral drugs used for hepatitis B?

A: The main problem I’ve already mentioned: resistance. Otherwise, the drugs are in pill form, so they’re easy to take and there are very few side effects.

Q: What about pregnant women infected with hepatitis B? Can you prevent them from infecting their child?

A: Yes, and this is very important, since this has been the most common and dangerous form of transmission. Infants born to hepatitis B-positive mothers should receive hepatitis immune globulin and vaccination within 12 hours of birth. Hepatitis B globulin gobbles up the virus in the serum and stops the virus from getting to the liver. These infants need to be followed to make sure they don’t develop infection.

Q: What progress would you like to see in the next few years?

A: We’d like to see that the vaccine reaches more and more people around the world, since it prevents infection and could eradicate hepatitis B. But with 400 million people already infected, we need better drugs to treat the disease.

Ideally we’d like to see a drug that can eliminate the virus in the immune tolerant phase. And we’d like drugs that are less likely to cause resistance in the virus. Several of the newest drugs seem to have less of a problem with resistance. But we said that about some older drugs for hepatitis B, and the virus proved us wrong, so we’ll have to wait and see.

Obviously this is a field with a lot of work to be done. My group is now participating in a National Institutes of Health network to study long-term outcomes of hepatitis B infection in the United States, better ways to treat the virus, and ways to define which patients are most at risk of progression of their disease.

Questions for Your Doctor

What to Ask About Hepatitis B

By Peter Jaret

Confronting a new diagnosis can be frightening — and because research changes so often, confusing. Here are some questions you may not think to ask your doctor, along with notes on why they’re important.

Do I have acute or chronic hepatitis B?

Acute infections occur in those who have been infected recently with the hepatitis B virus. Some acute infections are asymptomatic, but when symptoms do occur they include flulike muscle aches and weakness, fever, malaise and jaundice. Most acute hepatitis B infections do not need to be treated. Although infections can persist in adults, most chronic cases occur in people who are infected in infancy or childhood. Blood tests can tell doctors whether the infection is acute or chronic and if the virus is actively multiplying.

Has the infection caused any damage?

Doctors use several tests to determine if hepatitis B has caused damage. One blood test measures a substance called alanine aminotransferase, or ALT, which rises when the liver is damaged. Doctors also use CT scans or ultrasound to assess the condition of the liver. Liver biopsies may be recommended to look at tissue and cells.

Should I consider treatment now?

Doctors usually advise beginning treatment if tests show continuing liver damage. Patients with hepatitis B infection who are undergoing immunosuppressive or cancer chemotherapy should also receive antiviral drugs to prevent the virus from flaring. Age, family history and co-infections with other viruses like H.I.V. also influence the decision. Complications from hepatitis B usually begin to show up around age 40, so younger patients may be counseled to wait and be monitored.

How often should I be monitored?

This will depend on many factors, including whether the virus is active and whether previous tests have shown continuing liver damage. In general, your doctor will want to monitor your condition every three to six months. Even after patients have undergone treatment and the virus has been suppressed, periodic monitoring is recommended.

What’s the best choice of treatment?

The answer depends on factors including how far the infection has progressed and the subtype of virus. Interferon, the first drug approved for hepatitis B, is administered by injection and is often recommended for younger patients with signs of mild or moderate liver damage. Doctors now use a longer-lasting form called pegylated interferon, or peginterferon. The newer drugs, called nucleosides and nucleotides, are taken orally. They have very few side effects, so they can be given over long periods.

How long will I need to stay on the drug?

The length of therapy depends on the drug you receive and how your body responds to it. Peginterferon is given for a limited period, typically 16 to 48 weeks. Oral antiviral drugs, because they have few side effects, can be given for an indefinite period. If your immune system shows signs that it may be able to control the virus on its own, therapy may be stopped after what doctors call a consolidation period, usually six months to a year after blood tests show the infection is under control. People with a form of hepatitis B known as e-antigen negative are most likely to need to stay on medication. Those with e-antigen positive virus stand a better chance of stopping therapy.

What is the likely prognosis?

Doctors can’t say for sure. But new treatments and a better understanding of the natural history of this unpredictable virus have significantly improved the prospects in recent years. In almost all patients with chronic hepatitis B, the virus can be controlled and liver damage prevented or, in some cases, even reversed.

What if treatment doesn’t work?

If one treatment doesn’t work, another may. Doctors often switch people who don’t respond to peginterferon onto an antiviral medication, for example. And there are multiple antiviral drugs to try. If hepatitis B has severely damaged the liver, liver transplantation may be an option.

What if I’m pregnant or want to have children?

Hepatitis B passes easily from infected mother to baby, so it’s vitally important that infants born to hepatitis B-positive mothers receive hepatitis B immune globulin and vaccination within 12 hours of birth. Immune globulin helps prevent the virus from infecting a newborn baby. The vaccine triggers the immune system to recognize hepatitis B and generate antibodies against it.

Should I be tested for liver cancer?

Liver cancer can arise in people with hepatitis B even in the absence of obvious liver damage. Doctors recommend that people with hepatitis B be screened for liver cancer with blood tests and imaging tests like ultrasounds, CT scans or M.R.I.’s every six months starting around age 35 to 40. Screening tests may be recommended earlier in people with liver damage or a family history of liver cancer.

By Peter Jaret : NY Times Article : February 14, 2009

IN BRIEF:

Despite the development of an effective vaccine, hepatitis B infection remains a serious health problem worldwide.

Adults exposed to hepatitis B typically fight off the infection; infants and children almost always develop chronic infections.

People can carry hepatitis B virus without having symptoms, even though the infection may be damaging the liver.

Although not everyone infected develops serious complications, hepatitis B can lead to liver disease and cancer.

With seven treatments approved for hepatitis B, doctors can successfully control the infection in most patients.

The decisive scientific battle against hepatitis B has been won. Thanks to a vaccine approved in the 1980s, transmission of this potentially deadly virus can now be stopped. In countries where the vaccine is widely used, the series of three shots has almost completely halted the spread from infected mothers to their infants, one of the most common routes of transmission, and the one most likely to lead to chronic infection and serious liver disease. The vaccine has also significantly reduced transmission between adults.

Still, an estimated 1.3 million Americans and 400 million people worldwide harbor the virus. Chronic infection with hepatitis B can lead to cirrhosis, or scarring of the liver, and liver failure. Those infected with the virus have a 100-fold higher than average risk of liver cancer.

In the United States, most new cases occur in recent immigrants who were exposed as infants or young children in their native countries. Many don’t know they harbor the virus. A 2005 screening program of Asians and Pacific Islanders in New York City, for example, documented a 15 percent infection rate. One in three of those found to carry the virus were unaware they had been infected.

“These are hard populations to reach,” said Dr. Adrian Di Bisceglie, chief of hepatology at Saint Louis University School of Medicine. “Some are illegal immigrants who are afraid to go to the doctor. Others are self-employed first-generation immigrants who don’t want to get involved in the health care system.”

To reach more chronic carriers, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention issued new guidelines in September recommending testing for everyone born in regions where hepatitis B infects 2 percent or more of the population. That includes large swaths of Asia, the Pacific Islands, Africa, Eastern Europe and the Middle East, where the virus still runs rampant. Others at increased risk are men who have sex with men and intravenous drug users. Patients receiving chemotherapy or immunosuppressive drugs should also be tested; dormant infections can flare up dangerously when the immune system is suppressed.

For those already infected, the prognosis has brightened considerably with the approval of a succession of new and more effective drugs. The first drug used against the virus, interferon, has been supplanted by a longer-lasting version, called pegylated interferon, or peginterferon. In addition, six antiviral drugs, called nucleoside and nucleotide analogs, have been approved.

“Thirty years ago there was nothing we could offer these patients,” said Dr. Emmet B. Keeffe, chief of hepatology at Stanford University School of Medicine. “Today we can control the infection in a majority of patients.”

The most striking evidence comes from waiting lists for liver transplants, long the last-resort treatment for patients infected with hepatitis B who develop severe liver disease. Since 2000, the number of Americans registered for liver transplantation as a result of hepatitis B infection has dropped by 37 percent, according to a study by Dr. W. Ray Kim, a hepatitis expert at the Mayo Clinic College of Medicine.

Encouraging news also emerged from a landmark 2004 study in Taiwan that tested an antiviral drug called lamivudine against a placebo in patients with advanced disease. The trial was halted early because patients receiving the medication improved so much that the investigators felt obliged to switch all the volunteers to the active drug.

“This was the definitive study,” Dr. Di Bisceglie said. “We knew antiviral drugs could suppress virus levels and improve liver function. This showed that treatment also lowered rates of liver cancer and liver failure.”

Even with an arsenal of seven drugs, deciding when to start treatment — and when to stop it — is surprisingly complicated.

“The problem with hepatitis B infection is that the natural history of the disease is so variable,” said Dr. Nancy Reau, assistant professor at the University of Chicago Medical Center. When adults are exposed to the virus, they almost always fight it off successfully on their own. When infants are infected, however, their immature immune systems don’t recognize the invader, which almost always goes on to cause chronic infection. A decades-long period may follow during which the virus continues to replicate but causes little damage.

Then, for reasons not well understood, the immune system becomes triggered and begins to attack the virus. The battle itself accelerates damage to the liver, increasing the risk of cirrhosis, liver failure and liver cancer.

Yet a majority of patients with hepatitis B, again for unknown reasons, carry the virus without ever developing these serious consequences. Unfortunately, doctors cannot reliably predict who is at risk for trouble. “Our crystal ball just isn’t very good yet,” Dr. Reau said.

Physicians wouldn’t need a crystal ball if they had a drug that reliably cured the infection. But in most patients, the available drugs suppress the virus but do not eliminate it. Patients often have to stay on medication for years, even indefinitely.

“Obviously we don’t want to start patients on drugs if they don’t need them,” Dr. Di Bisceglie said. “And because the virus can develop resistance to antiviral drugs we have, we don’t want to start treating patients before they really need it. And the drugs are expensive.”

Deciding when to stop treatment can be equally difficult. In some patients, treatment suppresses the virus to undetectable levels, and once the drug is stopped, the infection remains quiet. But in others, the virus can flare up again after treatment ends, sometimes causing rapid liver damage.

Since some of the drug treatments are so new, and the course of hepatitis B so long, researchers are only beginning to answer questions about optimal long-term treatment. Still, helpful insights have emerged. Patients with hepatitis B who test positive for a protein in the blood called e-antigen appear to have the best shot at going off treatment without a flare-up. Those with e-antigen negative infections, on the other hand, are likely to need to be on therapy indefinitely. Researchers are also gaining insight into which patients will do best on peginterferon versus the newer antiviral drugs.

“Ironically, the more we learn, the more complicated our clinical decisions have become,” Dr. Reau said. “The field is moving so fast that what we did two years ago is already fairly obsolete.”

For people infected with hepatitis B, the rapid progress in research means having to weigh complicated options. But it also means a far greater chance that the virus can be kept at bay for a lifetime.

5 Things to Know

The Silent Threat of Hepatitis B

By Peter Jaret

Dr. Nancy Reau is an assistant professor of medicine at the University of Chicago’s Center for Liver Disease, where she specializes in treating hepatitis. Here are five things she says everyone should know about hepatitis B.

Hepatitis B is a silent threat.

People with chronic infections may feel fine for a long time, even as the virus is causing damage to the liver. Recent evidence shows that during the immune tolerant phase, when most researchers had assumed the virus was quiet, the liver may be sustaining injury. By the time symptoms appear, liver damage may be advanced. That’s why it is so important to be tested if you have any reason to think you might have been exposed.

People infected with hepatitis B should be tested for hepatitis C and H.I.V.

Both of these viruses can be transmitted via routes that are similar to hepatitis B. Co-infection raises the risk of complications. In addition, many doctors encourage people with hepatitis B infection to be vaccinated against hepatitis A to protect their livers from additional damage. Hepatitis A is typically transmitted in contaminated water or food.

Family members and close contacts of people infected with hepatitis B should be tested for the virus.

If they have not been exposed to it, they should be vaccinated.

Not every person infected with hepatitis B needs to start treatment right away.

Many people live with the virus and never develop serious symptoms. Most doctors counsel patients to wait until liver function tests and a biopsy show signs that the virus is beginning to cause damage. By waiting, doctors can limit the amount of time patients need to be treated and lower the risk that drug-resistant viruses will emerge.

Current drugs are very effective at controlling the virus and preventing damage.

And because the liver can regenerate itself, some patients with advanced disease may see their condition improve significantly after beginning treatment.

Expert Q & A

Tailoring Treatment For Hepatitis B

By Peter Jaret

Dr. Marion G. Peters is professor of medicine and director of hepatology research at the University of California, San Francisco. She has been chairwoman of the AIDS Clinical Trial Group Hepatitis Committee and currently conducts research on the immunology of chronic liver disease.

Q: What makes hepatitis B such a complicated disease to treat?

A: Unlike other liver diseases, hepatitis waxes and wanes. The disease can be inactive one year, active the next and then inactive again. So you have to constantly monitor patients who are chronically infected with hepatitis B. And then based on what you find, you have to decide when to treat them. We can’t have a one-size-fits-all approach to hepatitis B, because every individual is different.

Q: Why not treat everyone who is infected?

A: If we could eliminate the virus, we would. But the drugs we have suppress the virus and often have to be given over a long period of time, in some cases indefinitely. So we don’t want to treat someone whose disease is inactive. And we don’t want to start someone on an antiviral drug before they really need it. Nearly all the drugs we have available have some resistance. We don’t want to put a young person on a drug they don’t need and then have the virus develop resistance, so that when they do need the drug it may no longer work.

Q: How do you decide when to treat someone with hepatitis B?

A: The first thing I do is take a full history and physical and do blood tests to see if there is inflammation in the liver, which is measured by liver enzymes. Another test measures how much virus there is in the blood. I usually do an ultrasound as well, to assess the condition of the liver.

If the liver appears normal and the liver enzymes are normal, then the disease is inactive, and there’s no reason to treat.

At the other end of the spectrum are people who obviously have cirrhosis, or scarring of the liver, based on a clinical examination or an imaging study, and whose liver function tests are abnormal. Those are people we definitely want to begin treating, to avoid further damage to the liver. Generally, if they have active disease, I do a liver biopsy to see how severe the liver disease is.

Q: Are there instances when you’re not sure whether to start treatment?

A: That’s the challenge. Many people fall in between those two ends of the spectrum. They may have high levels of the virus in their blood but normal or only very slightly elevated liver enzymes. Or they may have intermediate levels of virus and a little bit of inflammation but not much. That’s where the controversy lies, whether to start such patients on treatment or wait.

If I’m unsure, if a patient doesn’t quite fit into one pigeonhole or another, I may recommend a biopsy to help sort out whether to treat or not. The decision is complicated by the fact that the more time patients remain with active disease, the higher their risk of developing liver cancer, which of course we don’t want to happen.

Q: If you decide to wait, how frequently do you monitor the patient?

A: All patients who have hepatitis B virus need to be monitored. How often and what tests we use really depend on the patient’s situation. A patient whose disease is inactive might be monitored every three months for a year and then every six months after that. A patient with some sign of liver problems but not enough to begin treatment should be monitored more often. Monitoring is very important, because we don’t want the patient to progress to cirrhosis or liver cancer.

Q: Can people have chronic hepatitis B and never develop problems?

A: The natural history depends to a great extent on whether people are infected as infants or as adults. About one in three or four people who acquire hepatitis B at birth will die of liver cancer or cirrhosis without monitoring and treatment. Over all, two out of three patients who have inactive disease do not progress to more serious disease. But it is not possible to determine who will progress and who will develop liver cancer without monitoring. That’s why it’s sometimes so difficult to know when to treat a patient.

Q: With seven drugs available, how do you decide which to use?

A: The first drug approved for hepatitis B was interferon, which we still use. But interferon is a tough drug to take because of its side effects, which include flu-like symptoms, muscle aches and pains, and some psychiatric symptoms. Only about one-third of patients respond to interferon. Still, in a young patient I might encourage them to take interferon because then you can save the other drugs for later if necessary.

The other drugs are called nucleotides or nucleosides, and there are a variety of factors that go into choosing the best one. There are several we don’t use much anymore because the virus develops resistance too quickly. And if a patient has developed resistance, then we’ll need to use a different drug. In some cases, especially after liver transplantation, we use a cocktail of antiviral drugs.

Q: How long do patients need to stay on the drugs?

A: That’s the big unknown. With hepatitis B, there are two types of infection. One is called e-antigen negative, and the other is e-antigen positive disease.

E-antigen positive hepatitis we can treat until they get a response and then consolidate the response with one more year of therapy. When we stop, in about 80 percent of patients, the virus remains inactive. These patients aren’t cured, but we’ve stopped the disease from progressing.

But with e-antigen negative hepatitis B, even if you treat patients for a few years and then stop, the disease will typically reactivate. So the problem is, when we put a patient with e-antigen negative disease on treatment, we’re in for the long-term. How long is long term? No one knows. We think it’s at least five years. But we don’t know.

Q: Are there unwanted side effects to the antiviral drugs used for hepatitis B?

A: The main problem I’ve already mentioned: resistance. Otherwise, the drugs are in pill form, so they’re easy to take and there are very few side effects.

Q: What about pregnant women infected with hepatitis B? Can you prevent them from infecting their child?

A: Yes, and this is very important, since this has been the most common and dangerous form of transmission. Infants born to hepatitis B-positive mothers should receive hepatitis immune globulin and vaccination within 12 hours of birth. Hepatitis B globulin gobbles up the virus in the serum and stops the virus from getting to the liver. These infants need to be followed to make sure they don’t develop infection.

Q: What progress would you like to see in the next few years?

A: We’d like to see that the vaccine reaches more and more people around the world, since it prevents infection and could eradicate hepatitis B. But with 400 million people already infected, we need better drugs to treat the disease.

Ideally we’d like to see a drug that can eliminate the virus in the immune tolerant phase. And we’d like drugs that are less likely to cause resistance in the virus. Several of the newest drugs seem to have less of a problem with resistance. But we said that about some older drugs for hepatitis B, and the virus proved us wrong, so we’ll have to wait and see.

Obviously this is a field with a lot of work to be done. My group is now participating in a National Institutes of Health network to study long-term outcomes of hepatitis B infection in the United States, better ways to treat the virus, and ways to define which patients are most at risk of progression of their disease.

Questions for Your Doctor

What to Ask About Hepatitis B

By Peter Jaret

Confronting a new diagnosis can be frightening — and because research changes so often, confusing. Here are some questions you may not think to ask your doctor, along with notes on why they’re important.

Do I have acute or chronic hepatitis B?

Acute infections occur in those who have been infected recently with the hepatitis B virus. Some acute infections are asymptomatic, but when symptoms do occur they include flulike muscle aches and weakness, fever, malaise and jaundice. Most acute hepatitis B infections do not need to be treated. Although infections can persist in adults, most chronic cases occur in people who are infected in infancy or childhood. Blood tests can tell doctors whether the infection is acute or chronic and if the virus is actively multiplying.

Has the infection caused any damage?

Doctors use several tests to determine if hepatitis B has caused damage. One blood test measures a substance called alanine aminotransferase, or ALT, which rises when the liver is damaged. Doctors also use CT scans or ultrasound to assess the condition of the liver. Liver biopsies may be recommended to look at tissue and cells.

Should I consider treatment now?

Doctors usually advise beginning treatment if tests show continuing liver damage. Patients with hepatitis B infection who are undergoing immunosuppressive or cancer chemotherapy should also receive antiviral drugs to prevent the virus from flaring. Age, family history and co-infections with other viruses like H.I.V. also influence the decision. Complications from hepatitis B usually begin to show up around age 40, so younger patients may be counseled to wait and be monitored.

How often should I be monitored?

This will depend on many factors, including whether the virus is active and whether previous tests have shown continuing liver damage. In general, your doctor will want to monitor your condition every three to six months. Even after patients have undergone treatment and the virus has been suppressed, periodic monitoring is recommended.

What’s the best choice of treatment?

The answer depends on factors including how far the infection has progressed and the subtype of virus. Interferon, the first drug approved for hepatitis B, is administered by injection and is often recommended for younger patients with signs of mild or moderate liver damage. Doctors now use a longer-lasting form called pegylated interferon, or peginterferon. The newer drugs, called nucleosides and nucleotides, are taken orally. They have very few side effects, so they can be given over long periods.

How long will I need to stay on the drug?

The length of therapy depends on the drug you receive and how your body responds to it. Peginterferon is given for a limited period, typically 16 to 48 weeks. Oral antiviral drugs, because they have few side effects, can be given for an indefinite period. If your immune system shows signs that it may be able to control the virus on its own, therapy may be stopped after what doctors call a consolidation period, usually six months to a year after blood tests show the infection is under control. People with a form of hepatitis B known as e-antigen negative are most likely to need to stay on medication. Those with e-antigen positive virus stand a better chance of stopping therapy.

What is the likely prognosis?

Doctors can’t say for sure. But new treatments and a better understanding of the natural history of this unpredictable virus have significantly improved the prospects in recent years. In almost all patients with chronic hepatitis B, the virus can be controlled and liver damage prevented or, in some cases, even reversed.

What if treatment doesn’t work?

If one treatment doesn’t work, another may. Doctors often switch people who don’t respond to peginterferon onto an antiviral medication, for example. And there are multiple antiviral drugs to try. If hepatitis B has severely damaged the liver, liver transplantation may be an option.

What if I’m pregnant or want to have children?

Hepatitis B passes easily from infected mother to baby, so it’s vitally important that infants born to hepatitis B-positive mothers receive hepatitis B immune globulin and vaccination within 12 hours of birth. Immune globulin helps prevent the virus from infecting a newborn baby. The vaccine triggers the immune system to recognize hepatitis B and generate antibodies against it.

Should I be tested for liver cancer?

Liver cancer can arise in people with hepatitis B even in the absence of obvious liver damage. Doctors recommend that people with hepatitis B be screened for liver cancer with blood tests and imaging tests like ultrasounds, CT scans or M.R.I.’s every six months starting around age 35 to 40. Screening tests may be recommended earlier in people with liver damage or a family history of liver cancer.