- RETIREMENT ANNOUNCEMENT

- HOME PAGE

- "MYCHART" the new patient portal

- BELMONT MEDICAL ASSOCIATES

- MOUNT AUBURN HOSPITAL

- EMERGENCIES

- PRACTICE PHILOSOPHY

- MY RESUME

- TELEMEDICINE CONSULTATION

- CONTACT ME

- LAB RESULTS

- ePRESCRIPTIONS

- eREFERRALS

- RECORD RELEASE

- MEDICAL SCRIBE

- PHYSICIAN ASSISTANT (PA)

- Medicare Annual Wellness Visit

- Case management/Social work

- Quality Care Measures

- Emergency closing notice

- FEEDBACK

- Talking to your doctor

- Choosing..... and losing a doctor

- INDEX A - Z

- ALLERGIC REACTIONS

- Alternative Medicine

- Alzheimer's Disease

- Bladder Problems

- Blood disorders

- Cancer Concerns

- GENETIC TESTING FOR HEREDITARY CANCER

- Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

- Controversial Concerns

- CPR : Learn and save a life

- CRP : Inflammatory marker

- Diabetes Management

- Dizziness, Vertigo,Tinnitus and Hearing Loss

- EXERCISE

- FEMALE HEALTH

-

GASTROINTESTINAL topics

- Appendicitis

- BRAT diet

- Celiac Disease or Sprue

- Crohn's Disease

- Gastroenterologists for Colon Cancer Screening

- Colonoscopy PREP

- Constipation

- Gluten sensitivity, but not celiac disease

- Heartburn and GERD

- Hemorrhoids and Anal fissure

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- NASH : Non Alcoholic Steato Hepatitis

- FEET PROBLEMS

- HEART RELATED topics

-

INFECTIOUS DISEASES

- Antibiotic Resistance

- Cat bites >

- Clostridia difficile infection - the "antibiotic associated germ"

- CORONA VIRUS

- Dengue Fever and Chikungunya Fever

- Food borne illnesses

- Shingles Vaccine

- Hepatitis B

- Hepatitis C

- Herpes

- Influenza

- Helicobacter pylori - the "ulcer germ"

- HIV Screening

- Lyme and other tick borne diseases

- Measles

- Meningitis

- MRSA (Staph infection)

- Norovirus

- Sexually Transmitted Diseases

- Shingles (Herpes Zoster)

- Sinusitis

- West Nile Virus

- Whooping Cough (Pertussis)

- Zika virus and pregnancy

- INSURANCE related topics

- KIDNEY STONES

- LEG CRAMPS

- LIBRARY for patients

- LIFE DECISIONS

- MALE HEALTH

- Medication/Drug side effects

- MEDICAL MARIJUANA

- MENTAL HEALTH

- Miscellaneous Articles

-

NUTRITION - EXERCISE - WEIGHT

- Cholesterol : New guidelines for treatment

- Advice to lower your cholesterol

- Cholesterol : Control

- Cholesterol : Raising your HDL Level

- Exercise

- Food : Making Smart Choices

- Food : Making Poor Choices

- Food : Grape Fruit and Drug Interaction

- Food : Vitamins, Minerals and Supplements

- Omega 3 fatty acids

- Vitamin B12 deficiency

- Vitamin D

- Weight Loss

- ORTHOPEDICS

- PAIN

- PATIENTS' RIGHTS

- SKIN

- SLEEP

- SMOKING

- STROKE

- THYROID

- SUBSTANCE ABUSE

- Travel and Vaccination

- TREMOR

- Warfarin Anticoagulation

- OTHER STUFF FOLLOWS

- Fact or Opinion?

- Hippocratic Oath

- FREE ADVICE.......for what its worth!

- LAUGHTER.....is the best medicine

- Physicians Pet Peeves

- PHOTO ALBUM - its not all work!

- Cape Town, South Africa

- Tribute page

- The 100 Club

- Free Wi-Fi

Travel and Vaccination

http://www.vaccineinformation.org/

For specific information about all immunizations

Tdap replaced the tetanus-diphtheria vaccine in 2005. Physicians should:

- advise their patients, particularly older individuals, that they should be up-to-date with their tetanus vaccination.

- recommend Tdap to patients aged 18 to 64 who have not had a tetanus shot in the past 10 years. Tdap may be given within 10 years of a tetanus shot to protect against pertussis.

- recommend that healthcare workers and people who have close contact with infants receive Tdap as soon as possible (as early as 2 years after the last tetanus shot).

Excellent resource for travelers issues

CDC Home Page : http://www.cdc.gov/

CDC Alphabetic Index of conditions: http://www.cdc.gov/az.do

CDC Traveler's advice: http://www.cdc.gov/travel/

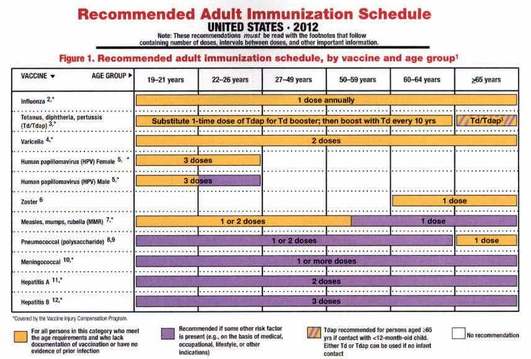

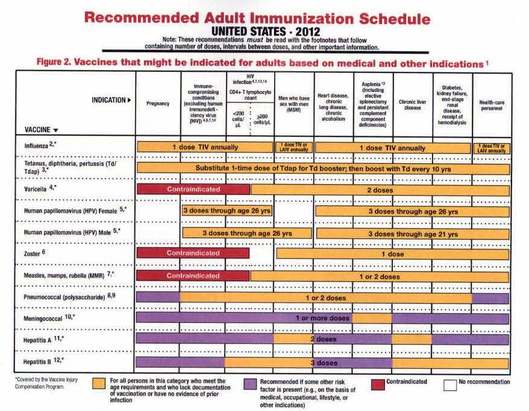

Immunization schedule for adults Immunization Schedule

The Travel Doctor : http://www.traveldoctor.co.uk/index.htm

The real dangers of not getting vaccines

Posted by Dr. Claire McCarthy : Boston.com : September 30, 2013

Not getting vaccines can be very dangerous--not just for you or your child, but for everyone around you.

It's ironic that part of the reason we have trouble convincing some people to immunize their children these days is exactly because they are so successful. Why immunize against polio, some people say, when there are no cases of it? Vaccines are so good at what they do that it's easy to get lulled into thinking that it's safe not to immunize--because we won't be exposed to the diseases anyway.

That's plain old wrong--travelers to and from other countries bring the diseases in all the time--and it's the kind of thinking that puts everyone at risk.

When enough people are immunized against a disease, it creates something called "herd immunity": even if someone shows up who has the disease, it's hard for it to spread because most of the people around that person are immune to it. Herd immunity doesn't just stop spread, it protects people who can't be immunized or aren't fully immunized, like newborns or people who have trouble with their immune systems. It also protects when the vaccines don't work perfectly (which can happen) or when a few people choose not to immunize.

But when lots of people stop immunizing, the herd immunity breaks down. And that's when bad stuff starts happening.

A study just published in the journal Pediatrics shows how this happened in California with pertussis, also known as whooping cough. What most people don't realize is that before we started immunizing against pertussis, it was the leading cause of child mortality in the US. In 1934, there were more than 265,000 cases of pertussis; in 1974, immunization had brought that down to 1010.

But in the early 2000's, the numbers started going up again--and in 2010, there were more than 9,000 cases in California alone, a third of all the cases in the country. There were various reasons for this, including waning immunity from the vaccine (we give booster doses now), but part of the problem was that more people weren't immunizing their children.

Between 2000 and 2010, the number of children whose parents chose not to immunize them--for reasons besides medical reasons--tripled from 0.77 percent to 2.33 percent. This seems low--and it would be, if the people were evenly spread out over the state. But they weren't; many of them lived in the same areas, meaning that in some communities the rate of not immunizing was as high as 84 percent.

The researchers who did the study found that cases of pertussis were 2.5 times more likely to happen in areas of the California where there were groups of people who didn't immunize. The herd immunity broke down--and children died.

When I talk to people who are hesitant about immunizations, what I mostly hear is worry about side effects. It's certainly true that vaccines, like any medical treatment, can have side effects. Luckily, they are rare--but they are certainly possible.

However--and this is what people don't think about--the risk of side effects from the vaccine are always lower than the risk of complications from the disease. And you can't necessarily count on not catching the disease. It's not just pertussis; we are seeing more measles, too, and other vaccine-preventable diseases. And influenza is a real risk every single year.

While you or your child might weather influenza, chicken pox, pertussis or whatever without too much trouble, the newborn next door, or your own newborn, or your frail grandmother or the child at school being treated for cancer might not. The immunization decision isn't just about you or your child. It's about every single person around you.

So if you are considering skipping any immunizations for your child or yourself, think hard before you make that potentially dangerous decision. Read not just about vaccines but about the diseases they prevent; there's lots of information about both on the website of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Talk to your doctor if you have any questions at all.

Remember: vaccines have saved thousands and thousands of lives. They might already have saved yours or your child's, whether you are immunized or not.

Planning a Vac(cin)ation

By Michelle Higgins : NY Times : July 27, 2011

GETTING vaccinated may be the last thing on your mind when heading off on vacation, but it’s important — whether you are traveling to an exotic destination or not.

Case in point: the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention issued a health advisory last month pointing out that the United States is currently experiencing the highest number of measles cases since 1996, many of which were acquired overseas. As of June 17, 156 confirmed cases of measles had been reported to the center this year; 136 of them involved unvaccinated Americans who had recently traveled abroad, unvaccinated visitors to the United States and people who didn’t travel but may have caught the disease from those who did.

The advisory, which encourages travelers planning trips abroad to make sure they have had the M.M.R. (measles, mumps and rubella) vaccine before they leave, illustrates that it isn’t just far-flung places that are a source of concern — outbreaks are occurring in places like France, Britain, Spain and Switzerland. “Those of us who run travel clinics are very used to seeing people going to developing countries or tropical countries” getting the relevant shots, said Dr. David O. Freedman, a board member at the International Society of Travel Medicine and a professor of medicine and epidemiology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. “But nobody thinks about it when they go to Europe.”

The thinking is similar, he said, for other popular destinations, including Mexico and parts of Central America. “There’s not a perception that you need to go and get a bunch of shots if you’re going to Cancún,” Dr. Freedman said. But in fact, he added, you should consider being vaccinated for certain food- and water-borne diseases like hepatitis A — one of the most common vaccine-preventable infections acquired during travel — which is prevalent in Mexico and other destinations in Latin America. In 2007, international travel was the most frequently identified risk factor for hepatitis A among United States cases for which exposure information was collected, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. As in previous years, most of those travel-related cases (85 percent) were associated with travel to Mexico, Central America or South America. Though many people recover from hepatitis A within a few weeks, in some cases the symptoms — fatigue, nausea, diarrhea and jaundice — can last two months or longer.

As a general rule, travelers should be up to date on routine immunizations “no matter where they are going and what they are doing,” said Dr. Phyllis Kozarsky, a travel health consultant at the C.D.C. and a professor of medicine at Emory University in Atlanta. In addition to the M.M.R., these vaccinations include a tetanus booster every 10 years and the influenza vaccine during flu season each year.

As for measles, the highly contagious disease has always been a risk for travelers in the developing world, experts say. But the increase in cases in the United States and large outbreaks occurring in Europe are recent issues, stemming in part from fears of parents who refuse to vaccinate their children because they believe immunizations cause illnesses, particularly autism, even though multiple studies have found no reputable evidence to support such a claim.

Although most Americans have been vaccinated for measles or are immune because they’ve had the disease, public health officials are concerned about those who have not been immunized, including babies and those born after 1957 (the cut-off year for people likely to be immune since the disease was endemic then), but before 1970, when vaccination became routine.

Before any international travel, infants 6 months through 11 months of age should have at least one dose of measles vaccine, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Children 12 months or older should have two doses separated by at least 28 days — whether traveling or not. And adults should review their vaccination records to ensure they’re up to date. The Web site cdc.gov offers a “Q&A” page about measles that includes more guidance on how to know if you need a vaccine.

You can also look up recommended vaccinations and information about disease prevention by destination on the agency’s Web site. But be sure to consult a travel medicine expert, ideally four to six weeks before your trip, for a complete risk assessment. The International Society of Travel Medicine offers a searchable directory of its members at istm.org.

“A backpacker going to the Thailand-Cambodian border visiting a refugee camp versus a C.E.O. of an international company staying at a deluxe hotel in Bangkok versus someone going on a honeymoon to the beaches are all very different, and very different risks,” said Dr. Kozarsky of the C.D.C.

A good doctor who specializes in travel medicine will go through your entire itinerary carefully, and consider everything from the regions you will be visiting (urban versus rural), your travel style (backpacking versus luxury hotel) and the time of year (which can influence exposure to mosquitoes, which spread malaria and dengue) to determine if the recommended vaccines or prevention measures are really necessary for your vacation.

Malaria and Japanese encephalitis are among the diseases listed under the C.D.C.’s travel health page for China, for example. But travelers visiting only major cities, like Beijing or Shanghai, don’t need to carry malaria pills or get a shot for Japanese encephalitis (a mosquito-borne disease endemic to rural areas in China).

Travel medicine experts can also be helpful in determining whether you need a yellow fever vaccine, which is required under international health regulations for travel to certain countries, including parts of sub-Saharan Africa and tropical South America, and must be administered at certified yellow fever vaccination centers, which can be found on the agency’s Web site.

Many countries require an “international certificate of vaccination or prophylaxis” signed by a medical provider for the yellow fever vaccine from travelers coming from an infected area. For example, Indian health regulations may ask for evidence of vaccination against yellow fever if you are arriving from sub-Saharan Africa or other yellow fever areas. If you do not have such proof, you could be subject to immediate deportation or a six-day detention in a yellow fever quarantine center, according to the State Department’s India information sheet. If you travel through any part of sub-Saharan Africa, even for one day, you are advised to carry proof of yellow fever immunization.

To be sure, travel vaccines aren’t cheap. And for the most part, insurance won’t cover them. The Travel Clinic of New York City, for example, charges $130 for a yellow fever shot and $90 for hepatitis A, according to its Web site, travelclinicnyc.com. That’s in addition to an $80 consultation fee.

But as long as you aren’t paying for unnecessary immunizations, the shots are worth it. Bottom line, said Dr. Freedman of the International Society of Travel Medicine, “Vaccines are your insurance policy.”

Vaccines aren't for kids alone

By Lauran Neergaard : AP Article : January 23, 2008

Vaccines aren't just for kids, but far too few grown-ups are rolling up their sleeves, disappointed federal health officials reported Wednesday.

The numbers of newly vaccinated are surprisingly low, considering how much public attention a trio of new shots — which protect against shingles, whooping cough and cervical cancer — received in recent years.

Yet many seem to have missed, or forgotten, the news: A survey by the National Foundation for Infectious Diseases found that aside from the flu, most adults have trouble even naming diseases that they could prevent with a simple inoculation.

"We really need to get beyond the mentality that vaccines are for kids. Vaccines are for everybody," said Dr. Anne Schuchat of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, who called the new data sobering. "We obviously have a lot more work to do."

The new CDC report found:

- Only about 2 percent of Americans ages 60 and older received a vaccine against shingles in its first year of sales.

"Many people describe the shingles pain as the worst pain they've ever endured," said Dr. Michael Oxman of the University of California, San Diego.

The shingles vaccine, Merck & Co.'s Zostavax, isn't perfect, but it cuts in half the risk of shingles — and those who still get it have a much milder case.

- About 2 percent of adults ages 18 to 64 got a booster shot against whooping cough in the two years since it hit the market.

The pertussis booster was added to another long-recommended shot, a booster against tetanus and diphtheria that adults should get every 10 years. The new triple combo is called "Tdap." Sanofi-Aventis's Adacel brand is for ages 11 to 64. There also is a version for 10- to 18-year-olds, GlaxoSmithKline's Boostrix.

- About 10 percent of women ages 18 to 26 have received at least one dose of a three-shot series that protects against the human papillomavirus, or HPV, that causes cervical cancer.

The vaccine, Merck's Gardasil, protects against four of those high-risk types. That's not complete protection — so even the vaccinated still need regular Pap smears — but those strains are responsible for about 72 percent of cervical cancer and 90 percent of genital warts, said Dr. Stanley Gall of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Stay tuned: The government is considering whether even more women should get the vaccine — those up to age 45 who aren't yet infected, Gall said. And studies are under way to see if it works in men.

Price may play a role in these low vaccination rates. The shingles shot costs around $150, and the three-shot HPV vaccine about $300, and insurance coverage varies. There's no national program to guarantee access for adults who can't afford vaccines as there is for child vaccines.

But adults aren't taking full advantage of some cheap old standby vaccines, either. Among people 65 or older, a high-risk age, CDC found only 69 percent get an annual flu shot; just 66 percent have had a one-time pneumonia vaccine; and 44 percent had received a tetanus shot in the past 10 years.

It's not too late for a flu shot this year — and Oxman urged getting some of the other adult shots in the same doctor visit.

Immunizations : The Controversy Persists

By Donald B. McNeil, Jr. : NY Times Article : March 29, 2008

IN BRIEF

Vaccinations are among the most important health advances in history.

Death rates for 13 diseases that can be prevented by childhood vaccinations were at all-time lows in the United States in 2007.

Rumors persist that some immunizations, or the vaccine preservative thimerosal, cause autism.

Public health experts generally agree that after clean water and flush toilets, the most important health advances in history have been vaccinations.

Shots against measles, diphtheria, whooping cough, tetanus, polio, mumps, rubella, chicken pox, flu, hepatitis and some causes of childhood meningitis, pneumonia and diarrhea have saved more lives than all the “miracle drugs” of the latter half of the 20th century — antibiotics like penicillin, antivirals like drugs to fight AIDS and flu, and so on. In addition, vaccination is one of the leading reasons that many families in the West now feel comfortable having only two or three children: they can be reasonably certain that the children will survive childhood.

According to a large historical study by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released in November 2007, death rates for 13 diseases that can be prevented by childhood vaccinations were at all-time lows in the United States. The study looked at hospital and death records going back to 1900 and estimated death rates before various vaccines were invented. In nine of the diseases, rates of hospitalization or death had declined more than 90 percent. For three — smallpox, diphtheria and polio — death rates had dropped by 100 percent.

In the 1930s, the United States had about 30,000 diphtheria cases a year, and 3,000 of those succumbed to the disease as gray membranes formed in their airways and eventually choked them to death. Diphtheria is now virtually unknown in the West, but in the chaos following the breakup of the former Soviet Union, vaccinations broke down, and the Red Cross estimated there were 100,000 cases and 5,000 deaths from the disease.

Smallpox vaccine is no longer given to children because the disease has been eliminated from the world, except for stocks frozen in laboratories in the United States and Russia. The smallpox vaccine also carried some risks.

Since the 1990s, vaccines have become somewhat controversial, even in the United States. As diseases have disappeared, generations have grown up without ever seeing the sickness and death they caused. At the same time, new parents are often upset as their babies receive between 20 and 30 injections before age 2 and suffer the pain and mild fever that can accompany them as routine side effects.

In addition, rumors continue to spread that some vaccines, or a mercury antifungal vaccine preservative called thimerosal that was added to vaccines, cause autism. Numerous studies have shown no link between autism and either vaccines or the preservative. An active anti-vaccine lobby, however, keeps the issue alive. The lobby is a broad tent. A few members question even whether bacteria and viruses cause disease; most seek more research into safety and greater rights to refuse vaccination.

State and city health departments, recognizing that the risk of epidemics soars when children gather daily in school, generally require parents to prove that children have been immunized before they enroll. There are some exceptions. All states allow medical exemptions for children who are immunocompromised or allergic to vaccine components. Most allow religious objections. A few allow “personal or philosophical” ones; how hard it is to get one varies by state.

Health insurers pay for most vaccines, and public clinics offer them free to the uninsured, the cost paid by the federal government under the Vaccines for Children Program of 1994. Before that time, incomplete vaccination was most common among the poor. Now it is more common for children from wealthy or middle-class families to lack some or all shots, presumably because their parents objected.

More vaccines are being developed all the time. Some are aimed at teenagers because they thwart diseases spread by sex or common in student dorms and military barracks. These include vaccines for human papillomaviruses, which cause cervical cancer; herpes; and meningococcal B infections, the cause of sometimes deadly meningitis. Others, like those against flu, shingles and some bacterial toxins, are particularly aimed at older people, who have weaker immune systems and are more likely to be in hospitals or nursing homes.

Newer vaccines tend to be much more expensive than older ones, which were developed before the era of clinical trials costing hundreds of millions of dollars and before medical liability lawsuits were so common. But the cost of not vaccinating at all, as history has taught, can be very high.

Expert Q & A

People Battling Vaccines

By Laurie Tarkan

Dr. Paul Offit, a pediatrician and chief of infectious diseases at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

Q. A number of new vaccines have recently rolled out. Have the big pharmaceutical companies been reinvigorated to produce vaccines?

A. Yes. In 1955, there were 27 companies that made vaccines. In the early ’80s, following a flood of litigation against vaccine makers that we now know were false claims, there was a decrease to about 18 companies. Now there are 5. Vaccines are not traditionally big money makers. They’re given once or a few times in one’s life, so they’re never going to be blockbusters. But starting in 2000, a number of new vaccines were introduced that had been in development for 15 to 20 years. What really reinvigorated vaccines was Prevnar, the pneumococcal vaccine that prevents against meningitis and ear infections. Here was the first vaccine to cross the billion-dollar mark. Then came the human pappilomavirus vaccine for cervical cancer, which is roughly a $2 billion-a-year product. Although they’re not traditional blockbusters, at least it’s enough to make it worthwhile for drug companies.

Q. The vaccine Gardasil, which prevents genital warts or human pappilomavirus (H.P.V.) and therefore protects against cervical cancer, has a lot of fans and some detractors. Hasn’t this been a great breakthrough?

A. Every year, there are 10,000 women who are newly diagnosed with cervical cancer, and every year about 3,500 die from the cancer. The vaccine has been tested in 30,000 women for more than five years. It’s safe. The two types of H.P.V. that it protects against account for about 70 percent of all cervical cancer. Probably the number is closer to 78 percent. They spent 15 to 20 years making a product which is remarkably effective and which prevents cancer. Jonas Salk had a ticker tape parade when he developed a vaccine for polio. The days for ticker tape parades for vaccines are over. But if there ever would be one, there should be one for this.

Q. Just as all of these new vaccines are coming out, it seems that the fear of vaccinations is growing.

A. I agree. The biggest reasons for this are that people are generally compelled by their fears, and since you don’t see vaccine-preventable diseases anymore, like polio, you don’t have a fear of it. For most mothers, vaccinations become a matter of faith — faith in pharmaceutical companies, faith in public health officials — and I think there’s been an erosion of faith. Second, I do think the media does not do a good job at educating us about where the real risks lie. So you’re scared of a pandemic like the bird flu but not scared of the epidemic flu, which kills 35,000 people a year. Scared of measles vaccine but not scared of measles.

Q. People are more scared of the mercury in the flu shot than the flu?

A. Right. A hundred children a year die from the flu. Most people who get the flu vaccine never imagine they’ll get the flu that will cause hospitalization or death. But people do die of flu. If you talk to some of these families that are now advocates for the flu shot, — who never could have imagined it would happen to them, and it happened to them — you’d get your flu shot. Don’t wait until it happens to you and then become an advocate for flu vaccine.

Q. It’s becoming more common for parents to have chickenpox parties to expose their children to the chickenpox rather than getting the vaccine. Is there anything terribly wrong with this approach?

A. Yes. Your child can die from chickenpox. We made a vaccine video about separating fact from fear. It so happened that one of the cameramen said his sister took her child to a chickenpox party, she was eight or nine years old, she got chickenpox and died from the infection. His sister was wracked with guilt. That’s no party. Prior to chickenpox vaccine, we had 100 deaths from chickenpox a year. That’s not common, but why take the risk if you don’t need to?

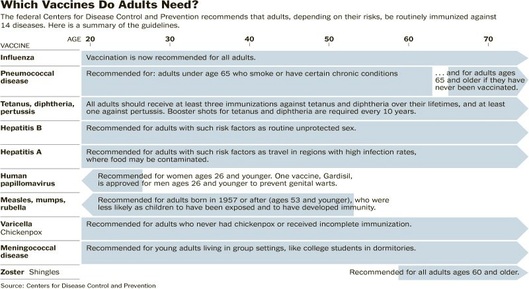

Q. Getting back to adults, many don’t know what vaccinations they should get, other than the flu shot. Do we need more immunizations than in the past?

A. Yes, the list has grown. The flu vaccine gets the most attention. But adults over 50 can also benefit from the pneumococcal vaccine. Pneumococcus is a fairly common cause of pneumonia and [raises the] risk of death in older adults. There’s a new shingles vaccine, for herpes zoster, recommended for those over 60. The chickenpox vaccine is recommended for all adults who haven’t had the chickenpox. And the hepatitis B vaccine is recommended for all adults who haven’t had it.

Q. Most adults don’t get all of these, is that correct?

A. Physicians who care for adults generally don’t think about vaccines as much as pediatricians do, and adults think of vaccines as a kid thing. As a country, we’re not good at immunizing adults, but if you look at the diseases that kill the most people, it’s influenza and hepatitis B.

Q. Which vaccines are especially underutilized?

A. Flu vaccine is far and away the most underutilized. It’s hard to utilize it. It’s difficult for the health care system to deliver a yearly vaccine to everybody. But hepatitis B and adult pertussis, or whooping cough, vaccine are also underutilized.

Q. One study found that adults are passing whooping cough to their children.

A. Most of the diseases that get transmitted are transmitted from children to adults. Any parent in day care can attest to that. But pertussis is different. Pertussis is a disease that adolescents and adults give to children.

Q. Weren’t most adults vaccinated against whooping cough (pertussis) as children?

A. Everybody needs the vaccine because immunity fades and we’re seeing a lot of pertussis. If you’ve had a cough that lasted weeks, a cough that just doesn’t seem to go away, chances are it was pertussis. Adults should get the Tdap vaccine, which covers whooping cough, tetanus and diphtheria.

Q. Is your risk of getting MRSA, the drug-resistant bacterial infection, higher when you get the flu?

A. If you look at influenza pandemics, it wasn’t just influenza that killed; typically it was a bacterial superinfection on top of it that took over. The flu can definitely set you up for bacterial pneumonias. Does getting flu vaccine lessen your chance of getting bacterial pneumonias? Yes.

Q. Are there any others that can also put you at risk for MRSA?

A. Yes, chickenpox. Chickenpox sets up for these drug-resistant skin infections, so the vaccine helps to prevent that.

Q. There’s some confusion among adults about who needs a chickenpox vaccine and who needs a shingles vaccine?

A. When people get the chickenpox, they recover from it, but the virus lives silently in their nervous system. When they get older, say 70 years of age, there’s a good chance that virus will awaken from that latent state and travel down the nerve route and cause shingles, which can be very painful. If you’ve had chickenpox, you should get the shingles vaccine at 60 years of age. And even if you’ve had shingles, it’s still recommended to get the vaccine. If you’ve never had the chickenpox, you should get the chickenpox vaccine, but you won’t need the shingles vaccine.

Q. Some parents feel that their kids are overloaded with vaccines. Is that a problem?

A. We’re up to 14 vaccines for infants and children. There’s a notion out there that all the vaccinations we give to children just seems like too much. It’s not too much. When you’re in the womb, you’re in a sterile environment. When you enter the birth canal and are born, you’re no longer in a sterile environment. Very quickly you have bacteria living on your skin, in your nose and throat. There are trillions of them that live on the surface of your body. You make an immune response to those bacteria. If you didn’t they would invade your bloodstream and cause death. So you’re constantly handling this barrage of environmental challenges, specifically in the form of fungi and bacteria that live on your body. One bacterium has 2,000 to 6,000 proteins. If you take all 14 vaccines that kids get, it’s probably 150 immunological components or proteins. It’s not just figuratively a drop in the ocean of what you manage every day. It’s literally a drop in the ocean.

Q. What about parents who delay certain shots?

A. The notion of delaying vaccines, withholding them or shifting them around, or having fewer boosters, because it’s too much of a challenge goes against everything one knows about the way your immune system works. People are reticent to give a newborn the hepatitis B vaccine and often delay it. Hepatitis B vaccine is one protein. If you can’t handle that vaccine as a newborn, you’re in big trouble.

Q. Should we expect to see many more vaccines in the next few years?

A. I think after the burst of vaccines you’ve seen in the first half of this decade, you’re not going to see much in the next 10 years. You’ll see extended recommendations on existing vaccines, but not new vaccines.

Questions for Your Doctor

What to Ask About Vaccinations

By Laurie Tarkan

Most pediatricians follow the recommended schedule for childhood vaccinations, making parents’ jobs easier. But with all the new vaccines that have been rolled out in recent years, it’s a good idea to have a vaccine conversation with your doctor, especially when it comes to older children and adults. Here are some questions you may not think to ask, along with notes on why they’re important.

What vaccines does my teenager need?

Three vaccines have recently become available for teenagers: one that guards against meningitis; another that includes protection against pertussis, or whooping cough; and a third for cervical cancer. The meningococcal vaccine protects teenagers against potentially deadly meningitis and bloodstream infections.

It used to be recommended only for those entering college, but the new form has longer-lasting protection and is now recommended starting at age 11, as the protection will now carry teenagers through college, when risk is highest. Children 8 to 12 may also be at risk at overnight camps and on sports teams.

The Tdap vaccine, for tetanus, diphtheria and pertussis, is now routinely recommended for teenagers as well as adults. In the past, teenagers would get just tetanus and diphtheria boosters because of safety concerns surrounding the pertussis vaccine, but the new vaccine is considered safe. Pertussis boosters are necessary because the immunization effects of the single shot fade. Whooping cough is one of the few vaccine-preventable diseases that are still not under control.

The third vaccine, Gardasil, protects teenage girls against cervical cancer by taking aim at the human papilloma virus, or H.P.V. It is recommended at age 11 to 12 and requires three injections over a six-month period — or up to age 26 for those who did not get it when younger.

Does my teenager need a chickenpox booster?

The initial recommendation for the chickenpox vaccine was one shot for children 12 to 18 months old. In 2005, because of evidence that the vaccine wears off, it was recommended that all children get a booster dose between ages 4 and 6. Children 8 to 12 and teenagers who received one dose as infants but haven’t gotten the booster need to get one, research shows, because the effects can wear off and getting chickenpox later in life can have serious complications.

What new vaccines does my child need?

There are two new recommendations, one for hepatitis A and another for flu.

The flu vaccine is now recommended for children 6 months to 5 years old. A new intranasal form, approved for 2- to 5-year-olds, can be given instead of a shot. Ask about the cost difference between the two if you’re paying out of pocket, as the nasal spray is more expensive. A flu shot is also recommended for older children with chronic conditions like asthma.

The hepatitis A vaccine was initially recommended only in certain states where the incidence of the disease was high but is now recommended for all children beginning at 1 year old.

Should I get my child a thimerosal-free flu shot?

The evidence is very strong that there is no connection between autism and thimerosal, a mercury-containing vaccine preservative. But a thimerosal-free influenza vaccine for children is available.

As an adult, what shots do I need?

Nearly 50,000 Americans die of vaccine-preventable diseases each year, and 99 percent of them are adults. Adults need tetanus and diphtheria boosters every 10 years.

What if I’m pregnant?

A woman who is thinking of having a baby or who works in a health care or child care setting should ask about the Tdap vaccine against tetanus, diphtheria and pertussis (whooping cough). Adults, even those without symptoms, can spread pertussis to infants younger than 2 months, before they are vaccinated, putting them at serious risk. If you know you’re going to have a baby, the entire family and even grandparents should be up to date on their pertussis vaccinations.

Do you send reminders out about boosters or other vaccinations?

Most doctors don’t. But if they did, there would be more compliance.

Do I need the vaccine against shingles?

People who have had chickenpox are at risk for shingles as they get older. The herpes zoster vaccine protects against shingles and is approved for people 60 and older, although some doctors give it “off label” to younger adults. Many insurers don’t pay for it (it can cost up to $300), and Medicare’s coverage is spotty. Shingles can be very painful, and one in five patients have lingering debilitating pain, so immunization is highly recommended.

Do I need any other vaccines if I’m over 50?

The annual influenza vaccine is recommended for all people over 50. The pneumococcal vaccine, which protects against pneumococcal pneumonia, is recommended for people 65 and older.

What vaccine side effects should I look out for?

Vaccine Information Statements, produced by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, explain the benefits, risks and potential side effects of various vaccines, from anthrax to yellow fever. Federal law requires that these or similar informational statements must be handed out before certain vaccinations are given. It’s good practice to review this material to become aware of possible side effects and what symptoms to look for.

What if a bad reaction occurs?

Most reactions are not serious, but federal health officials urge vaccine recipients to help them monitor reactions by reporting to their doctors unusual symptoms like high fever, behavior changes or allergic reactions like difficulty breathing, rapid heart beat, dizziness, hives or wheezing and asking the doctors to file a Vaccine Adverse Event Report. Patients can file reports themselves through www.vaers.hhs.gov or by calling (800) 822-7967.

FOREIGN TRAVEL :

Questions for Your Doctor

By Eric Sabo : NY Times Article : April 18, 2008

Traveling to foreign countries can present unique health risks. Here are some questions you may not think to ask your doctor, along with notes on why they’re important.

Are there any special precautions I should take before traveling abroad?

Some areas within the developing world are riskier than others, requiring a greater range of medications or vaccines to prevent such problems as food-borne illnesses and infectious disease. A travel health specialist is often the best qualified to outline what you need, especially for destinations that are off the beaten path. But all those considering a trip abroad should be up-to-date on their routine vaccinations, as even industrialized countries can have a higher than normal risk of commonly prevented diseases. You should also bring along remedies to help with more common traveler woes, like motion sickness, sunburns and colds.

What shots do I need if I’m traveling to the developing world?

Make sure your standard vaccines are still current — including mumps, measles and rubella — and update them if they have expired. Other vaccinations will depend on what area you’re traveling to. Experts generally recommend being vaccinated against hepatitis A, since the disease is commonly spread and easily prevented with the vaccine.

Are there any unusual diseases I need to be concerned about where I’m visiting?

Exotic threats like encephalitis or Chagas disease are far greater problems for local populations than for travelers, who are not likely to come into contact with the bugs and unsanitary conditions that spread these diseases. Still, hiking or swimming in remote areas, namely in the tropics, can put you at risk for common third-world infections, including schistosomiasis. Travelers should also be cautious in areas where indigenous diseases like dengue are endemic.

Should I be concerned if I’m visiting a modern country comparable to the United States?

The greatest danger when visiting any country is automobile accidents, the leading cause of preventable deaths for travelers. Sexually transmitted diseases are another major concern, as the rates of H.I.V. are rising in some European countries. Travelers should use the same common sense they would use at home, like practicing safe sex and not driving drunk.

What should I do to prepare for my trip if I have a medical condition?

People with diabetes, underlying heart disease or other health problems should take precautions like any traveler. In addition, ask for an extra prescription in case you run out of your medication, and make a copy of your medical records to bring along so local doctors can better treat you if you get sick. Check with your doctor to see if your travel itinerary is reasonable and safe. Those with immune deficiencies may have special requirements for vaccinations.

Should I take my medications with me, or can I just buy some where I’m going?

Take any medications you may need with you, as not every country has the same drugs available and pharmacies may have different requirements for refilling your prescriptions. Some commonly prescribed drugs may be cheaper and sold over-the-counter in developing countries. But there is a greater risk of ending up with counterfeit and potentially dangerous medications.

Is it safe to travel abroad if I’m pregnant?

Women in their later stages of pregnancy are advised to stay close to home, because it may be harder to get proper health care while traveling. The best time to travel is during the second trimester, when there is less of a chance for miscarriages or premature labor. Pregnant women may want to avoid traveling to high-altitude areas and countries where there is a greater risk of life-threatening diseases spread by food and insects.

Are there any new health threats where I’m going?

Reports of disease outbreaks can surface relatively quickly, so check with a travel health specialist to see whether there are any new advisories for areas you’re visiting. Depending on the level of risk, you may need to take extra precautions, like getting a separate vaccine or postponing your trip. You can find current information on disease outbreaks and other health-related issues for international travelers on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Web site (www.cdc.gov/travel).

I returned from a vacation abroad feeling sick. Could I have caught something?

You should see a doctor if you’re feeling ill after a trip, much as you would if you were sick at home. Having a fever after visiting a malaria-prone area requires immediate attention. But you may also want to see a doctor if you continue to have stomach discomfort or bouts of diarrhea, a common traveler ailment. The problems are sometimes caused by parasites that can be treated with specific drugs.

Is there anything I can take to help an upset stomach?

Most cases of traveler’s diarrhea will eventually clear up on their own, but you can take prescription antibiotics and over-the-counter remedies like Imodium to help you recover faster. Drinking plenty of water and taking an oral rehydration solution can help against dehydration that accompanies severe diarrhea.

Travel Threats Around the World :

Expert Q & A

By Eric Sabo : NY Times Article ; April 18, 2008

Dr. Phyllis Kozarsky is a professor of medicine at the Emory University School of Medicine and the director of Travel Well, a traveler’s medical clinic in Atlanta. She is also the coauthor of the recently updated Centers for Disease Control and Prevention yellow book, “Health Information for International Travel 2008.”

Q: What are the most common health risks that international travelers face?

A: In travel to the developing world, the most common thing is traveler’s diarrhea. Respiratory diseases, skin problems and rashes are also top on the list.

Sexually transmitted diseases are a problem in the developing and developed world because when people travel they do things they wouldn’t do at home, such as having casual and unprotected sex.

There’s also the exacerbation of chronic disease. A major cause of death abroad is cardiovascular disease. That’s because someone who has underlying heart disease may be traveling in a remote region or trekking in Nepal and they have a heart attack.

Health care that may not be the same as at home is an issue for people. It’s not just the young and healthy who are traveling anymore. Everybody goes now.

Q: Many people tend to be concerned when traveling to developing countries. But should travelers take precautions when visiting places like France or England?

A: We tend to focus on exotic diseases, but the No. 1 cause of death to American travelers is motor vehicle accidents. Certainly in areas of the developing world where the roads are poor and there are animals on the road, that’s a bigger problem.

But behavior and common sense change when anyone travels. People are more likely to drive and drink, be on motorcycles without helmets and do things that are kind of crazy. They wouldn’t think of getting on the back of an open truck here in the United States on a major highway, but somehow in another country its O.K. because everyone does it.

Q: Are some parts of the world more risky to travelers than others?

A: It’s not necessarily by region; it would be more by what someone’s itinerary might be and their style of life. For example, a corporate executive going to Thailand and staying in a deluxe hotel would have a different risk versus a student traveler who might be hitting the beach, although they’re going to the same country. If you have an adventurous lifestyle — hike and swim, eat anything off the road or immerse yourself more in the culture — it’s much riskier.

Q: Do specific regions present their own unique health risks?

A: Absolutely. In Southeast Asia, there’s a huge rise in dengue, which is spread by mosquitoes, like malaria. We certainly worry about dengue in South and Central America as well, as that’s on the rise there, too.

Malaria is still very common and is a huge hazard in many parts of world. It affects 300 million people and kills several million people a year, mostly children in Africa.

However, we have an increasing number of American travelers now who travel to malaria areas, and people are not often aware that they absolutely need to take precautions, including malaria pills.

Q: There are various disease outbreaks from time to time, like the recent yellow fever epidemic in Paraguay. How do travelers get warnings of such things?

A: These are the types of problems that make it imperative to see someone who is up to date in travel health before traveling. If you went in to your regular doctor and told them that you’re going to Paraguay, they might not know where it is. Or they would joke around and say don’t drink the water, and that would be the end of it.

Yellow fever is no longer just in the jungles, but it’s showing up in Paraguay’s capital, the first time in 30 years. You need someone who’s up to date to know there are problems there and that everyone visiting that country should be vaccinated right now.

Q: Where can people find a qualified travel doctor?

A: There are many clinics now that specialize in travel medicine. The International Society of Travel Medicine has a list on its Web site (www.istm.org). Health departments are a good place to turn to if you live in smaller towns.

Travel medicine has emerged from something of a cottage industry 20 years ago to a full-fledged medical specialty today. In order to keep track of disease spread around the world and the amount of travel going on, providers have to keep up to date almost daily with the kinds of things that are going on.

Q: What vaccines should people take when traveling abroad?

A: The first thing is to update routine vaccines. If someone never got a second measles-mumps-rubella vaccine, they should. Or if they’re going to an area where there is still polio, they should get a booster of polio vaccine. Anything basic, like getting the influenza vaccine during flu season.

Then you get into specific travel vaccines. Yellow fever is the typical one that people think of, and it gets complicated as to where it’s required or recommended. In sub-Sahara Africa and tropical South America, a yellow fever vaccine is needed.

Then there are vaccines like hepatitis A, which for the most part we recommend for all travelers. It’s an excellent vaccine, and hepatitis A is a big risk from substandard food and water that can be easily prevented.

Q: If you’re traveling abroad for just a short time, do you need to take all these precautions?

A: It depends on the amount of risk that people want to take on themselves, and that’s a very personal decision. For example, most vaccines are not required for international travel. But some might have a high-risk aversion and just say, “Give me everything,” even if it’s not that common within the region.

Q: Is it safe to travel abroad if you have an underlying condition, like diabetes or heart disease?

A: Our goal is to enable people, so we try to figure out the best way people can go within realistic boundaries. You advise people about their medication schedule and give them an extra prescription for their trip. You provide access to physicians and health care facilities where they’re traveling. And you tell them to carry their medical records, which is helpful.

Getting special insurance is also important, because most health insurance does not cover going abroad. There are very inexpensive policies for people to extend their own health insurance when they’re traveling. We encourage people to buy medical evacuation insurance as well, because they can find themselves very far away from home in a hospital they don’t want to be at, and it can cost as much as $100,000 for an emergency transfer.

Q: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends taking a general health kit when traveling. What should that include?

A: It depends on someone’s itinerary and degree of adventure. What I usually tell people is to go to their favorite pharmacy and pick off the shelves things that make them feel comfortable when they’re sick. The worst thing in the world is to be stuck in a hotel room and not have anything that is going to even symptomatically make you feel better.

Many of these countries have everything over the counter, and it’s cheaper. But there are concerns in many parts of the world about counterfeit medications or contaminants in medications.

We also give people prescriptions for anti-malarials when needed. We usually recommend Imodium and prescription antibiotics to treat traveler’s diarrhea. They may also need motion sickness medications, or something to help them sleep if they’re going on a long flight.

Q: If you do get sick on a trip, how do you find a good doctor?

A: It can be tough. The United States Embassy in each country usually has a list of doctors. A lot of luxury hotels are attached to physicians, as well as having physicians on staff themselves, so that’s another route.

Q: Even with all these precautions, some are still worried about traveling abroad. How do you reassure people to safely enjoy their trip?

A: The world is so small now. You can bring your cellphone almost anywhere; we’re all connected. It’s almost as if you make an effort to be out of touch.

Traveler's Diarrhea an Overview

Traveler's diarrhea is loose, watery, and frequent stools that occur after visiting areas with contaminated water supplies, poor sewage systems, or inadequate food handling. High-risk destinations include third-world or developing countries, including Latin America, Africa, the Middle East, and Asia.

This article discusses the appropriate foods and fluids to consume if you develop traveler's diarrhea.

Alternative Names

Diet - traveler's diarrhea

Function

Bacteria and the toxins in the water and food supply cause traveler's diarrhea. (People living in these areas often don't get sick because their bodies have developed some degree of immunity.)

You can decrease your risk of developing traveler's diarrhea by avoiding water and food that may be contaminated. The goal of the traveler's diarrhea diet is to reduce the impact of this illness and avoid severe dehydration.

Side Effects

Traveler's diarrhea is rarely life-threatening for adults. It is more serious in children as it can frequently lead to dehydration.

Recommendation

Prevention of Traveler's Diarrhea:

- Water:

- Do not use tap water for drinking or brushing teeth.

- Do not use ice made from tap water.

- Use only boiled water (at least 5 minutes) for mixing baby formula.

- For infants, breast-feeding is the best and safest food source. However, the stress of traveling may decrease milk production.

- Do not use tap water for drinking or brushing teeth.

- Other beverages:

- Drink only pasteurized milk.

- Drink bottled drinks if the seal on the bottle hasn't been broken.

- Carbonated drinks are generally safe.

- Hot drinks are generally safe.

- Drink only pasteurized milk.

- Food:

- Do not eat raw fruits and vegetables unless you peel them.

- Do not eat raw leafy vegetables (e.g. lettuce, spinach, cabbage); they are hard to clean.

- Do not eat raw or rare meats.

- Avoid shellfish.

- Do not buy food from street vendors.

- Eat hot, well-cooked foods. Heat kills the bacteria. Hot foods left to sit may become re-contaminated.

- Do not eat raw fruits and vegetables unless you peel them.

- Sanitation:

- Wash hands often.

- Watch children carefully. They put lots of things in their mouths or touch contaminated items and then put their hands in their mouths.

- If possible, keep infants from crawling on dirty floors.

- Check to see that utensils and dishes are clean.

- Wash hands often.

If you or your child get diarrhea, continue eating and drinking. For adults and young children, continue to drink fluids such as fruit juices and soft drinks (non-caffeinated). Salted crackers, soups, and porridges are also recommended.

Dehydration presents the most critical problem, especially for children. Signs of severe dehydration include:

- Decreased urine (fewer wet diapers in infants)

- Dry mouth

- Sunken eyes

- Few tears when crying

If rehydration fluids are not available, you can make an emergency solution as follows:

- 1/2 teaspoon of salt

- 2 tablespoons sugar or rice powder

- 1/4 teaspoon potassium chloride (salt substitute)

- 1/2 teaspoon trisodium citrate (can be replaced by baking soda)

- 1 liter of clean water

If you or your child have signs of severe dehydration, or if fever or bloody stools develop, seek immediate medical attention.

Travel Precautions

Insect Repellents

Vector-borne diseases are infections transmitted by insects that harbor parasites, viruses, or bacteria. Common vector-borne diseases include yellow fever, malaria and Dengue Fever, but there are many others in every country in the world.

The risk for malaria and other mosquito-born infections is highest when mosquitoes feed, between dusk and dawn.

DEET.

Most insect repellents contain the chemical DEET (N,N-diethyl-meta-toluamide), which remains the gold standard of currently available mosquito and tick repellents. DEET has been used for more than 40 years and is safe for most children when used as directed. Comparison studies suggest that DEET preparations are the most effective insect repellents now available.

Concentrations range from 4 - 100%. The concentration determines the duration of protection. Experts recommend that most adults and children over 12 years old use preparations containing a DEET concentration of 20 - 35% (such as Ultrathon), which provides complete protection for an average of 5 hours. (Higher DEET concentrations may be necessary for adults who are in high-risk regions for prolonged periods.)

DEET products should never be used on infants younger than 2 months. According to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), DEET products can safely be used on all children age 2 months and older. The EPA recommends that parents check insect repellant product labels for age restrictions. If there is no age restriction listed, the product is safe for any age. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that children use concentrations of 10% or less; 30% DEET is the maximum concentration that should be used for children. In deciding what level of concentration is most appropriate, parents should consider the amount of time that children will be spending outside, and the risk of mosquito bites and mosquito-borne disease.

When applying DEET, the following precautions should be taken:

- Do not use on the face, and apply only enough to cover exposed skin on other areas.

- Do not apply too much and do not use under clothing.

- Do not apply over any cuts, wounds, or irritated skin.

- Parents or an adult should apply repellent to a child instead of letting the child apply it. They should first put DEET on their own hands and then apply it to the child. They should avoid putting DEET near the child's eyes and mouth, and also on the hands (since children frequently touch their faces).

- Wash any treated skin after going back inside.

- If using a spray, apply DEET outdoors -- never indoors.

- Do not apply spray repellents directly on anyone's face.

Use of Permethrin. Permethrin is an insect repellent used as a spray for clothing and bed nets, which can repel insects for weeks when applied correctly. Electric vaporizing mats containing permethrin may be very helpful. A permethrin solution is also available for soaking items, but should never be applied to the skin. Side effects from direct exposure may include mild burning, stinging, itching, and rash, but in general, permethrin is very safe and its use may even reduce child mortality rates from malaria. Travelers allergic to chrysanthemum flowers or who are allergic to head-lice scabicides should avoid using permethrin.

Other Preventive Measures against Vector-borne Diseases:

- Wear trousers and long-sleeved shirts, particularly at dusk. One survey suggested that this measure may significantly reduce the incidence of mosquito-born disease.

- Sleep only in screened areas.

- Air-conditioning may reduce mosquito infiltration. Where air-conditioning is not available, fans may be helpful. Mosquitoes appear to be reluctant to fly in windy air.

- Do not wear perfumes.

- Minimize skin exposure after dusk.

- Wash hair at least twice a week.

- Burning citronella candles reduces the likelihood of bites. (Indeed, burning any candle helps to some extent, perhaps because the generation of carbon dioxide diverts mosquitoes toward the flame.) Smoke from burning certain plants, including ginger, beetlenut, and coconut husks, have also reduced mosquito infiltration, but the irritating and toxic effects on the eyes and lungs (such as the seen with the citrosa plant) may be considerable. To date, no evidence shows much benefit to burning plants but such methods are not harmful.

Motion Sickness

About a third of the population is susceptible to motion sickness, with varying degrees of severity. The cause of motion sickness is still unclear. Some evidence suggests that, in susceptible people, motion triggers signals that the brain interprets as being in conflict with the brain's memory of correct position. It transmits this message to other parts of the body, which respond with sweating, nausea, salivating, and other symptoms of motion sickness. Other theories suggest that motion sickness is triggered by the body's inability to control its own posture and movement.

More women than men experience motion sickness, with one study suggesting that this may be associated with gender differences in the ability to perform spatial tasks. Women appear to be at higher risk just before and during menstruation. Motion sickness may also trigger migraines, even in people who do not ordinarily have them. Alcohol intake increases the risk of vomiting. The following are some remedies tried for motion sickness:

Medications.

Prescribed medications include scopolamine in oral form or as a patch (Transderm Scop), which is worn behind the ear and releases the drug slowly. Scopolamine is the most effective drug for motion sickness.

Over-the-counter medications include dimenhydrinate (Dramamine), meclizine (Bonine), and cyclizin (Marezine). Dramamine appears to be the most rapidly effective, although in one study Marezine caused less drowsiness and was more effective at reducing nausea after 3 minutes. Cinnarizine (Stugeron) is used in Europe and appears to be effective, with few side effects. It is not available in the US. None of these medications are as effective as prescription drugs but may be helpful for 6 - 12 hours. To ensure the drug achieves its desired effect, take oral medications at least an hour before traveling.

Nearly all the medications used for motion sickness, both prescription and nonprescription, can cause drowsiness, mouth dryness, and blurred vision. Scopolamine can cause heart rhythm disturbances. In one comparison study the scopolamine patch and cinnarizine had the fewest adverse effects on functioning. Dimenhydrinate had the most.

Non-medicinal Treatments.

Common recommendations include focusing on the horizon (not on nearby areas), and avoiding alcohol and strong odors. Non-medicinal or alternative remedies are widely used, but are of unproven benefit. Some are even silly, but travelers who experience motion sickness may wish to try anything that isn't harmful. Some methods that have been tried include:

- Taking ginger root capsules (2,000 mg) or eating large amounts of ginger starting about 12 hours before traveling. (Clinical studies are inconsistent on ginger's benefits, with some reporting relief without side effects.)

- Acupressure (wrist bands and self pressure). Acupressure for motion involves exerting pressure on the P6 pressure point -- the so-called nausea-relief point. Travelers can try pressing on the nausea-relief point, located two finger widths below the crease of the wrist on the palm-up side and between the two major tendons leading to the hand. Studies have been inconsistent on the benefits of wrist bands. Some studies have reported relief with a wristband (such as ReliefBand) that uses batteries. These barriers create a small electric charge at the acupressure point. The device may cause a rash, and people with pacemakers should not use it.

- Cold packs. In one study, appling cold packs to the forehead reduced the stomach activity of motion sickness.

- Eating small meals. Protein meals may be more effective in controlling stomach activity than carbohydrates.

- Behavioral Techniques. Some studies have reported relief by using certain behavioral approaches such as controlled breathing (concentrating on breathing gently or deeply), or listening to music.

Issues Involving Air Travel

Effects on Circulation.

Traveling by car, airplane, or train for more than four hours increases the risk for blood clots in the legs (deep vein thrombosis, also known as DVT) in anyone. Those at highest risk include people with cardiovascular disease or its risk factors, people who have had recent surgery, cancer patients, and those taking oral contraceptives. Studies now suggest that DVT is the cause of more deaths than previously believed, because symptoms typically occur days after travel. In order to keep circulation moving during international flights or on trains, travelers should drink plenty of fluids, avoid salt, wear slippers, wear clothing that fits loosely in the waist and legs, take frequent walks in the aisles, and lift their legs up and down several times an hour. Two 2003 studies suggested that special socks that compress the ankles (such as Kendall Travel Socks, Sigvaris Traveno) may significantly prevent swelling and possibly blood clots due to long flights, even in travelers at medium to low risk.

Respiratory Infections.

Flight cabins have very low humidity, which not only increases the risk for dehydration and dry eyes, but it also increases the risk for triggering disease in the airways. Fliers with colds or allergies are especially susceptible. The first rule is to drink plenty of liquids. Taking a decongestant tablet or nasal spray (not one containing an antihistamine) 30 minutes before flight can help prevent sinus and ear infections.

Of greater concern are studies suggesting that the prolonged time (8 hours or more) spent in the confined space of an airplane, combined with the close proximity to passengers from around the world, may facilitate the spread of serious contagious diseases such as tuberculosis and SARS. The CDC and World Health Organization now have guidelines on when and how to determine the need for preventive treatments after possible exposure to infectious organisms. (Recirculated air, which is now common in new aircraft, does not increase the risk for respiratory infections.)

Preventing Jet Lag.

Crossing time zones can throw off the body's natural rhythms, especially when travelers fly from west to east. But jet lag can be minimized. A few days before long flights, adjust sleeping and eating patterns:

- When traveling west, travelers might avoid outdoor light after 6 p.m.

- If traveling east, travelers might begin going to bed earlier a few days before the trip and avoid outdoor light until 10 a.m.

- If possible, flights should be completed well ahead of an important event requiring concentration.

- If crossing multiple time zones, the traveler should schedule overnight stopovers.

- The traveler should drink plenty of fluids, but avoid alcohol and coffee, which increase fluid loss.

Cruise Ships

Reports of illnesses aboard cruise ships, particularly gastrointestinal problems from contaminated food, have alarmed many travelers. A sanitation program conducted by the U.S. Public Health Service should significantly cut the risk for such problems. Cruise ships are inspected twice a year and are then rated. The CDC provides ratings to the public for all ships sailing from U.S. ports. At this time the ratings are the only guide for a healthy cruise. Meanwhile, cruise-ship travelers should avoid eating eggs and shellfish to help protect against diarrhea.

Aside from sanitation, health problems in general are common on cruise ships. A study of one major cruise ship reported that nearly 30% of the passengers were treated for skin disorders and 26% for respiratory problems while on board. The highly contagious norovirus, brought on board by one passenger, can quickly spread throughout the ship. Flu outbreaks sometimes occur even in summer. Older people who have not been immunized the previous flu season should ask their doctor about flu vaccinations. They add no value for people who had been previously immunized.

Preventing Skin Disorders

An estimated 3 - 10% of travelers experience some skin problem related to their trip, particularly when traveling to tropical and subtropical areas.

Avoiding Exposure to Sunlight.

Many developing countries are in the tropics, were sunlight is intense. Ultraviolet radiation from sunlight not only can cause sunburn, but excessive sunlight and heat can cause toxic skin reactions in susceptible individuals. Everyone should avoid episodes of excessive sun exposure, particularly during the hours of 10 a.m. to 4 p.m., when sunlight pours down 80% of its daily dose of damaging ultraviolet radiation. Reflective surfaces like water, sand, concrete, and white-painted areas should be avoided. Clouds and haze are not protective. High altitudes increase the risk for burning in shorter time, compared to sea level and lower altitudes. Sunscreens and sunblocks with an SPF of 15 or higher are important and should be used generously. However, they should not be relied on for complete protection. Wearing sun-protective clothing is equally important, and provides even better protection than sunscreens. Everyone, including children, should wear hats with wide brims.

Preventing Skin Infections.

People who visit the tropics or developing regions are at risk for a number of skin disorders, including infections with fungi and other organisms. Cleanliness is essential. Bathing or showering is very beneficial, but if there are no facilities, simply washing with soap and water (even if cold) is still helpful. (Note: Taking multiple daily showers can remove protective oils and is not recommended.)

The skin should also be kept dry in order to prevent fungal infections, which thrive in damp, warm climates. Take special care to clean and keep dry certain skin areas where infections are most likely to occur. They include creases in the skin, the armpits, the groin, buttocks, and areas between the toes. Use talcum powder in these areas. Keep socks dry.

Precautions when Traveling to High Altitudes

Acute high altitude illness, or mountain sickness, can affect the brain (mountain sickness, cerebral edema), the lungs (pulmonary edema), or both. Studies suggest that about 25% of mountain climbers experienced symptoms at 7,000 - 9,000 feet, and 42% of them have symptoms at 10,000 feet. Rapid ascension to high altitude, such as arrival by airplane, increases the risk. In most cases the condition is mild. Severe lack of oxygen at high altitudes, however, can cause serious problems in some people.

- Acute Mountain Sickness. This syndrome is defined as headache and at least one other relevant symptom when a person travels to about 8,000 feet. Other symptoms include upset stomach, dizziness, weakness, fatigue, and difficulty sleeping. It typically develops in the first 12 hours, and may resolve spontaneously if the traveler remains at the same altitude.

- High Altitude Cerebral Edema (HACE). HACE is a life-threatening brain swelling and the severe endpoint of acute mountain sickness. Symptoms include altered consciousness, loss of coordination, difficulty concentrating, and lethargy. In extreme cases, it can lead to coma and death.

- High Altitude Pulmonary Edema (HAPE). HAPE is the occurance of fluid in the lungs, which in rare cases can be severe. In one study, about 75% of mountain climbers who ascended to 15,000 feet had some mild form of HAPE. Worse performance and a dry cough suggest the onset of HAPE. In extreme cases it can cause severe lung deterioration. (If it is going to develop at all, HAPE usually occurs in the first 2 days and rarely after 4 days at a given altitude.)

Risk Factors for High Altitude Sickness.

The risk for high altitude sickness is determined by certain characteristics: The rate at which a person ascends; the altitude reached; altitude during sleep; and individual physiology. People who live yearlong at low altitudes are much more likely to be ill at greater heights. Being physically stronger is not protective. Certain common conditions (heart disease, diabetes, hypertension, mild emphysema, and pregnancy) play no role in a person's risk for high altitude sickness. (Upper respiratory infections, however, do increase the risk for HAPE.)

Precautions against Mountain Sickness. Acclimatization by staying several days at increasingly higher altitudes is recommended. If you take high blood pressure medication, ask your doctor about increasing dosage if traveling to high altitudes. And anyone with a chronic medical condition should check with his or her doctor.

The following are some measures for preventing mountain sickness.

- As a rule, ascend no more than 1,000 feet per day at altitudes of 8,000 feet and above. Drink 6 - 8 glasses of water or juice a day and avoid alcohol.

- Stop climbing when experiencing any symptoms of acute mountain sickness. Descend if symptoms worsen. Also descend immediately if there are any symptoms of HACE or HAPE.

- Supplementary oxygen may be required for people who show signs of these conditions.

- People who are hiking to very high altitudes may consider an inflatable chamber (Gamow bag and others). Such devices enclose a person, and when pumped up they simulate air pressure found at low altitudes.

Some medications are available for prevention or treatment of acute mountain sickness.

- Ibuprofen (Advil) may be sufficient to manage headache associated with acute mountain sickness.

- Acetazolamide (Ak-Zol, Diamox) taken one day before, and continued during initial exposure to high altitude, can reduce symptoms of acute mountain sickness, improve exercise performance and sleep, and reduce muscle and body fat loss. It may be used to treat minor symptoms of acute mountain sickness, but if symptoms persist, the traveler should descend to a lower altitude.

- Dexamethasone (Decadron Phosphate, Dexasone, Hexadrol Phosphate) is used to treat acute mountain sickness and cerebral edema (HACE). Dexamethasone is not recommended for prevention, however, because of potentially dangerous side effects.

- Nifedipine (Adalat) is used to treat pulmonary edema (HAPE) and may be used for prevention in people who know they are at high risk for HAPE.

- Preventive use of salmeterol (Serevent), a long-acting inhaled asthma drug known as a beta-adrenergic agonist, may reduce the risk for HAPE by over 50%.

Travelers planning to descend rather than ascend must also take precautions. Individuals with the following conditions should not scuba dive:

- Heart and lung diseases

- Bleeding disorders

- Chronic ear infections or sinus infections blocking the ears

- Diabetes

- Pregnancy

- History of seizures

- History of migraine headaches

Avoiding Air Embolism.

Air embolisms are bubbles that obstruct blood vessels and can occur in divers who hold their breath while swimming up to the surface. They can be life threatening and cause long-term neurologic impairment, including memory lapses, impaired thinking, and emotional disorders. Even tiny bubbles may do some harm over time. One study found that in amateur divers who dive frequently, tiny bubbles appeared to increase the risk for small brain lesions and degenerating spinal disks.

To eliminate these bubbles, experts recommend that you:

- Ascend no faster than 30 feet per minute

- Remain 15 feet below the surface for 3 - 5 minutes before surfacing

- Avoid air travel for 24 hours after diving.

- Drowning. The other major cause of scuba diving deaths is drowning in underwater caves due to improper training and poor equipment.