- RETIREMENT ANNOUNCEMENT

- HOME PAGE

- "MYCHART" the new patient portal

- BELMONT MEDICAL ASSOCIATES

- MOUNT AUBURN HOSPITAL

- EMERGENCIES

- PRACTICE PHILOSOPHY

- MY RESUME

- TELEMEDICINE CONSULTATION

- CONTACT ME

- LAB RESULTS

- ePRESCRIPTIONS

- eREFERRALS

- RECORD RELEASE

- MEDICAL SCRIBE

- PHYSICIAN ASSISTANT (PA)

- Medicare Annual Wellness Visit

- Case management/Social work

- Quality Care Measures

- Emergency closing notice

- FEEDBACK

- Talking to your doctor

- Choosing..... and losing a doctor

- INDEX A - Z

- ALLERGIC REACTIONS

- Alternative Medicine

- Alzheimer's Disease

- Bladder Problems

- Blood disorders

- Cancer Concerns

- GENETIC TESTING FOR HEREDITARY CANCER

- Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

- Controversial Concerns

- CPR : Learn and save a life

- CRP : Inflammatory marker

- Diabetes Management

- Dizziness, Vertigo,Tinnitus and Hearing Loss

- EXERCISE

- FEMALE HEALTH

-

GASTROINTESTINAL topics

- Appendicitis

- BRAT diet

- Celiac Disease or Sprue

- Crohn's Disease

- Gastroenterologists for Colon Cancer Screening

- Colonoscopy PREP

- Constipation

- Gluten sensitivity, but not celiac disease

- Heartburn and GERD

- Hemorrhoids and Anal fissure

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- NASH : Non Alcoholic Steato Hepatitis

- FEET PROBLEMS

- HEART RELATED topics

-

INFECTIOUS DISEASES

- Antibiotic Resistance

- Cat bites >

- Clostridia difficile infection - the "antibiotic associated germ"

- CORONA VIRUS

- Dengue Fever and Chikungunya Fever

- Food borne illnesses

- Shingles Vaccine

- Hepatitis B

- Hepatitis C

- Herpes

- Influenza

- Helicobacter pylori - the "ulcer germ"

- HIV Screening

- Lyme and other tick borne diseases

- Measles

- Meningitis

- MRSA (Staph infection)

- Norovirus

- Sexually Transmitted Diseases

- Shingles (Herpes Zoster)

- Sinusitis

- West Nile Virus

- Whooping Cough (Pertussis)

- Zika virus and pregnancy

- INSURANCE related topics

- KIDNEY STONES

- LEG CRAMPS

- LIBRARY for patients

- LIFE DECISIONS

- MALE HEALTH

- Medication/Drug side effects

- MEDICAL MARIJUANA

- MENTAL HEALTH

- Miscellaneous Articles

-

NUTRITION - EXERCISE - WEIGHT

- Cholesterol : New guidelines for treatment

- Advice to lower your cholesterol

- Cholesterol : Control

- Cholesterol : Raising your HDL Level

- Exercise

- Food : Making Smart Choices

- Food : Making Poor Choices

- Food : Grape Fruit and Drug Interaction

- Food : Vitamins, Minerals and Supplements

- Omega 3 fatty acids

- Vitamin B12 deficiency

- Vitamin D

- Weight Loss

- ORTHOPEDICS

- PAIN

- PATIENTS' RIGHTS

- SKIN

- SLEEP

- SMOKING

- STROKE

- THYROID

- SUBSTANCE ABUSE

- Travel and Vaccination

- TREMOR

- Warfarin Anticoagulation

- OTHER STUFF FOLLOWS

- Fact or Opinion?

- Hippocratic Oath

- FREE ADVICE.......for what its worth!

- LAUGHTER.....is the best medicine

- Physicians Pet Peeves

- PHOTO ALBUM - its not all work!

- Cape Town, South Africa

- Tribute page

- The 100 Club

- Free Wi-Fi

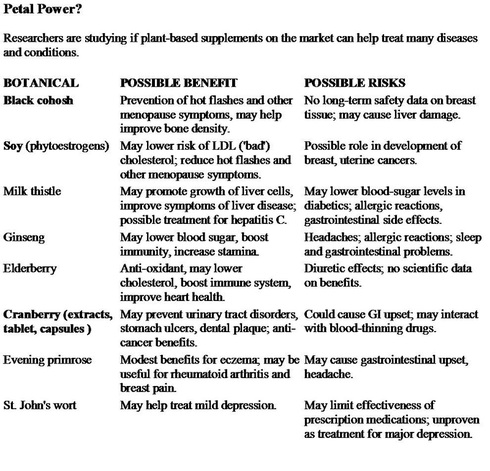

Alternative Medicine

I respect and appreciate the role of acupuncture and chiropractic manipulation in certain conditions and try to be open minded about alternative medical approaches.

It is important that I be kept informed about certain herbal or natural preparations you may be taking because of the potential for interaction with medications that I may prescribe for you.

We know for example that nearly 30 percent of women use alternative therapies to treat the symptoms of menopause. These include soy-rich foods and Black cohosh.

I have no problem with the use of glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate in the management of degenerative arthritis or Saw Palmetto for men with prostate problems.

It is strongly advised to discontinue any herbal product at least one week before undergoing general anesthesia as it has been reported that garlic, gingo and ginseng could cause bleeding when combined with commonly prescribed drugs used in surgery.

Ephedra and Mahuang found in weight loss and energy enhancing supplements can cause an irregular heart beat and an increased risk of of heart attack and stroke; ginseng may exacerbate low blood sugar; Kava and Valerian could exaggerate the impact of anesthetics; Echinacea could pose a risk of poor wound healing and infections; St John's Wort could speed up the metabolism of certain drugs as it interferes with the P450 enzyme system in the liver that the body uses to break down about half of all drugs. Because of this, St John's Wort is believed to interfere with many of the most widely prescribed medicines used for heart disease, certain seizure medicines and drugs used to prevent organ rejection after transplants.

Garlic supplements, often taken in the hope of lowering cholesterol, can seriously interfere with the drugs used to treat AIDS. St John's Wort can have the same effect and Kava has been shown to be associated with liver toxicity.

Basically what I'm trying to get across is that "natural" does not necessarily mean "safer".

Applying Science to Alternative Medicine

By William J. Broad : NY Times Article : September 30, 2008

More than 80 million adults in the United States are estimated to use some form of alternative medicine, from herbs and megavitamins to yoga and acupuncture. But while sweeping claims are made for these treatments, the scientific evidence for them often lags far behind: studies and clinical trials, when they exist at all, can be shoddy in design and too small to yield reliable insights.

Now the federal government is working hard to raise the standards of evidence, seeking to distinguish between what is effective, useless and harmful or even dangerous.

“The research has been making steady progress,” said Dr. Josephine P. Briggs, director of the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine, a division of the National Institutes of Health. “It’s reasonably new that rigorous methods are being used to study these health practices.”

The need for rigor can be striking. For instance, a 2004 Harvard study identified 181 research papers on yoga therapy reporting that it could be used to treat an impressive array of ailments — including asthma, heart disease, hypertension, depression, back pain, bronchitis, diabetes, cancer, arthritis, insomnia, lung disease and high blood pressure.

It turned out that only 40 percent of the studies used randomized controlled trials — the usual way of establishing reliable knowledge about whether a drug, diet or other intervention is really safe and effective. In such trials, scientists randomly assign patients to treatment or control groups with the aim of eliminating bias from clinician and patient decisions.

Sat Bir S. Khalsa, the study’s author and a sleep researcher at the Harvard Medical School, said an added complication was that “the vast majority of these studies have been small,” averaging 30 or fewer subjects per arm of the randomized trial. The smaller the sample size, he warned, the greater the risk of error, including false positives and false negatives.

Critics of alternative medicine have seized on that weakness. R. Barker Bausell, a senior research methodologist at the University of Maryland and the author of “Snake Oil Science” (Oxford, 2007), says small studies often have a built-in conflict of interest: they need to show positive results to win grants for larger investigations.

“All these things conspire to produce false positives,” Dr. Bausell said in an interview. “They make the results extremely questionable.”

That kind of fog is what Dr. Briggs and the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine, with a budget of $122 million this year, are trying to eliminate. Their trials tend to be longer and larger. And if a treatment shows promise, the center extends the trials to many centers, further lowering the odds of false positives and investigator bias.

For instance, the center is conducting a large study to see if extracts from the ginkgo biloba tree can slow the progression of Alzheimer’s disease. The clinical trials involve centers in California, Maryland, North Carolina and Pennsylvania and recruited more than 3,000 patients, all of them over 75. The study is to end next year.

Another large study enrolled 570 participants to see if acupuncture provided pain relief and improved function for people with osteoarthritis of the knee. In 2004, it reported positive results. Dr. Brian M. Berman, the study’s director and a professor of medicine at the University of Maryland, said the inquiry “establishes that acupuncture is an effective complement to conventional arthritis treatment.”

In an interview, Dr. Briggs said another good way to improve clinical trials was to ensure product uniformity, especially on herbal treatments. “We feel we have really influenced the standards,” she said.

Over the years, laboratories have found that up to 75 percent of the samples of ginkgo biloba failed to show the claimed levels of the active ingredient. Scientists doing a clinical trial have a large incentive to fix that kind of inconsistency.

Dr. Briggs said such investments would be likely to pay off in the future by documenting real benefits from at least some of the unorthodox treatments. “I believe that as the sensitivities of our measures improve, we’ll do a better job at detecting these modest but important effects” for disease prevention and healing, she said.

An open question is how far the new wave will go. The high costs of good clinical trials, which can run to millions of dollars, means relatively few are done in the field of alternative therapies and relatively few of the extravagant claims are closely examined.

“In tight funding times, that’s going to get worse,” said Dr. Khalsa of Harvard, who is doing a clinical trial on whether yoga can fight insomnia. “It’s a big problem. These grants are still very hard to get and the emphasis is still on conventional medicine, on the magic pill or procedure that’s going to take away all these diseases.”

Diet Supplements and Safety: Some Disquieting Data

By Dan Hurley : NY Times Article : January 16, 2007

In October 1993, during a Senate hearing on a bill to regulate herbs, vitamins and other dietary supplements on the presumption that they were safe, Senator Orrin G. Hatch, Republican of Utah, spoke up in their defense. Herbal remedies “have been on the market for centuries,” he said, adding: “In fact, most of these have been on the market for 4,000 years, and the real issue is risk. And there is not much risk in any of these products.”

That benign view was written into the bill when it was passed by both houses the following year. While the law, the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994, forbade manufacturers to claim that their products “treat, cure or prevent” any disease, it allowed them to make vaguer claims based on a standard that did not require them to do any testing. And it stated that “dietary supplements are safe within a broad range of intake, and safety problems with the supplements are relatively rare.”

But hiding in plain sight, then as now, a national database was steadily accumulating strong evidence that some supplements carry risks of injury and death, and that children may be particularly vulnerable.

Since 1983, the American Association of Poison Control Centers has kept statistics on reports of poisonings for every type of substance, including dietary supplements. That first year, there were 14,006 reports related to the use of vitamins, minerals, essential oils — which are not classified as a dietary supplement but are widely sold in supplement stores for a variety of uses — and homeopathic remedies. Herbs were not categorized that year, because they were rarely used then.

By 2005, the number had grown ninefold: 125,595 incidents were reported related to vitamins, minerals, essential oils, herbs and other supplements. In all, over the 23-year span, the association — a national organization of state and local poison centers — has received more than 1.6 million reports of adverse reactions to such products, including 251,799 that were serious enough to require hospitalization. From 1983 to 2004 there were 230 reported deaths from supplements, with the yearly numbers rising from 4 in 1994, the year the supplement bill passed, to a record 27 in 2005.

The number of deaths may be far higher. In April 2004, the Food and Drug Administration said it had received 260 reports of deaths associated with herbs and other nonvitamin, nonmineral supplements since 1989. But an unpublished study prepared in 2000 for the agency by Dr. Alexander M. Walker, then the chairman of epidemiology at the Harvard School of Public Health, concluded: “A best estimate is that less than 1 percent of serious adverse events caused by dietary supplements is reported to the F.D.A. The true proportion may well be smaller by an order of magnitude or more.”

The supplements linked to the most reactions in 2005, according to the poison control centers, were ordinary vitamins, accounting for nearly half of all the reports received that year, 62,446, including 1 death. Minerals were linked to about half as many total reports, 32,098, but that number included 13 deaths. Herbs and other specialty products accounted for still fewer total reports, 23,769, but 13 deaths. Essential oils were linked to 7,282 reports and no deaths.

Among herbs and other specialty products, melatonin and homeopathic products — prepared from minuscule amounts of substances as diverse as salt and snake venom — had the most reports of reactions in 2005. The poison centers received 2,001 reports of reactions to melatonin, marketed as a sleep aid, including 535 hospitalizations and 4 deaths. Homeopathic products, often marketed as being safe because the doses are very low, were linked to 7,049 reactions, including 564 hospitalizations and 2 deaths.

But most other types of herbs and specialty supplements also appear in the annual report. In 2005, the poison centers received 203 reports of adverse reactions to St. John’s wort, including 79 hospitalizations and 1 death. Glucosamine, with or without chondroitin, was linked to 813 adverse reactions, including 108 hospitalizations and 1 death. Echinacea was linked to 483 adverse reactions, including 55 hospitalizations, 1 of them considered life-threatening. Saw palmetto was not listed on the report.

Injuries to children under 6 account for nearly three-quarters of all the reports of adverse reactions to dietary supplements, according to the poison centers. In 2005, the most recent year for which figures are available, 48,604 children suffered reactions to vitamins alone, the ninth-largest category of substances associated with reactions in that age group.

Major medical groups and government agencies do not generally recommend vitamin or mineral supplements for children who are otherwise healthy. But an analysis of the National Maternal and Infant Health Survey, published in the journal Pediatrics in 1997, found that 54 percent of parents of preschool children gave them a vitamin or mineral supplement at least three days a week.

Advocates of the products correctly point out that the poison centers’ figures do not prove a causal link between a product and a reaction and that, in any case, far more people are injured and killed by drugs. Painkillers alone were associated with 283,253 adverse reactions in 2005, according to the poison centers, more than twice as many as with supplements. But only 3.5 percent of those reactions occurred when people took the prescribed amount of painkiller; most were from overdoses, either accidental or intentional. The same was true of asthma drugs (3.6 percent of reactions were associated with the prescribed dose) and cough and cold drugs (3.1 percent).

While reactions to vitamins, minerals and essential oils occurred at similarly low levels when people took the recommended amounts, adverse reactions linked to the recommended levels of herbs, homeopathic products and other dietary supplements accounted for 10.3 percent of all reactions to those products reported to the poison centers — about three times the level seen for most drugs.

Drugs marketed in the United States go through a rigorous F.D.A. approval process to prove that they are effective for a particular indication, with the potential risks balanced against the benefits. While the approval process has come under attack in recent years as unduly favorable to drug companies, it remains among the toughest in the world.

There is no comparable requirement for supplements. Even so, hundreds of millions of tax dollars have been spent since the early 1990s on hundreds of studies to test the possible benefits of supplements. The National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine, established by Congress in 1991 to “investigate and validate unconventional medical practices,” has a 2007 budget of more than $120 million.

Since April 2002, five large randomized trials financed by the center have found no significant benefit for St. John’s wort against major depression, echinacea against the common cold (but see new data below on this particular supplement), saw palmetto for enlarged prostate, the combination of glucosamine and chondroitin for arthritis, or black cohosh and other herbs for the hot flashes associated with menopause.

A new source of data on adverse reactions to dietary supplements will soon become available: in December, Congress passed a measure requiring the manufacturers of dietary supplements and over-the-counter drugs to inform the F.D.A. whenever consumers call them with reports of serious adverse events. The bill was signed by President Bush the day after Christmas. It is a welcome acknowledgment that “natural” does not always mean “safe.”

Dan Hurley is the author of the new book “Natural Causes: Death, Lies and Politics in America’s Vitamin and Herbal Supplement Industry” (Broadway Books), from which this essay is adapted.

Another Supplement, Under the Microscope

By Michael Manson : NY Times Article : March 13, 2007

Not so long ago, antioxidant vitamins were hailed as nature’s own weapons against chronic illness, powerful antidotes to horrid diets and failed exercise plans.

A parade of observational studies showed that people who consumed large amounts of vitamins C and E and beta carotene were usually healthier than those who ingested comparatively little. Almost overnight, it seemed, millions of consumers morphed into fervid pill poppers, and antioxidants were dolloped into an ever expanding variety of foods.

But recent and more rigorous research suggests that this silver bullet missed its mark. Most long-term prospective trials have shown that using antioxidant vitamin supplements does not prevent heart disease or cancer, with the possible exception of prostate cancer.

In a study published last month in The Journal of the American Medical Association, researchers in Europe analyzed data from 68 large trials in which more than 232,000 adults were given antioxidant supplements.

In a subset of those studies, the scientists concluded, subjects taking vitamins A and E and beta carotene saw a slightly increased risk of death compared with those who did not take supplements. (Vitamin C had no effect on mortality, the team found.)

So are America’s most popular vitamins actually harmful? Not likely, other experts say. Although antioxidant supplements have not been the cure-alls scientists had hoped for, there may yet be a place for them.

“A lot of researchers, including myself, were quite disappointed that the trials showed no benefit, particularly for vitamin E,” said Dr. Meir Stampfer, an epidemiologist at Harvard. “But I don’t think it closes the door on the antioxidant concept.”

The new study has garnered frightening headlines and vigorous criticism. Dr. Stampfer and others say its analysis is methodologically flawed, because it includes data from widely heterogeneous studies, excludes data from hundreds of others for unclear reasons and does not try to detail the causes of increased mortality among supplement users.

“It just seems implausible that antioxidants should be killing you by several different means,” said Dr. Jeffrey Blumberg, a nutrition professor at Tufts. “I don’t buy it.”

Dr. Andrew Shao, vice president of the Council for Responsible Nutrition, a trade group for the supplement industry, said, “Most of these patients already had disease, so the conclusions simply aren’t relevant to a healthy population.”

The study’s authors defended their methods. “Previous studies have included a select group of trials, risking cherry-picking, either good or bad,” said the lead researcher, Dr. Goran Bjelakovic of the University of Nis in Serbia. “Our systematic review is based on more trials and more participants, and hence is more powerful.”

Other studies of healthy adults taking antioxidants have also proved disappointing. After tracking nearly 40,000 women for a decade, researchers at Harvard found that those taking vitamin E were just as likely as others to suffer cardiovascular disease and cancer.

“There was no evidence of harm, but there was no benefit, either,” said Dr. Julie E. Buring, an author of the study. “It’s really too bad. Vitamin E had been incredibly promising.”

For a few consumers, it may still be promising. In the Harvard study, a subgroup of participants older than 65 who took vitamin E did have significantly fewer heart attacks and strokes than those who did not, although the finding may have been due to chance. Vitamin E and selenium have been strongly associated with a reduced risk of prostate cancer in a few studies.

“There still may be subsets of people who are very responsive to the benefits of antioxidants,” said Dr. Blumberg, who serves on scientific advisory boards for some supplement companies.

The essential premise behind antioxidant supplements remains intact, researchers say. Oxygen-free radicals, a normal byproduct of metabolism, damage cellular DNA unless antioxidant compounds remove them. Oxidative damage is characteristic of a wide variety of chronic diseases.

Still, faced with solid basic science but a litany of null results in the clinic, many scientists are calling for a change in tactics. Some theorize that a randomized clinical trial, the gold standard for medical research, may not be the best way to evaluate vitamin supplements.

“You just can’t do this kind of study with something like cancer, which can take 20 years to develop in an initially healthy person,” said Dr. Bruce Ames, a biochemist at the University of California, Berkeley.

Moreover, cancer and heart disease arise from a powerful confluence of genetic and environmental influences. In hindsight, it was naïve of scientists and consumers to hope that the relatively short-term addition of one or two antioxidants would be enough to counteract decades of poor diet and inadequate exercise, not to mention the genome.

Antioxidants remain essential to health. That much has not changed.

But for most of us, the time has come to let go of the notion that high-dose supplements provide a magic wand against disease. The good news is that a diet rich in fruits and vegetables contains literally thousands of antioxidant nutrients. Prevention begins in the kitchen.

Echinacea Helps Colds, Major Review Shows

By Nicholas Bakalar : NY Times Article : July 24, 2007

Echinacea helps banish colds. Echinacea has no effect on colds. The verdict seems to shift with each new scientific study of the herbal remedy.

In the latest twist, a review of more than 700 studies has concluded that echinacea has a substantial effect in preventing colds and in limiting their duration.

The paper, published in the July issue of The Lancet Infectious Diseases, used statistical techniques to combine the results of existing studies and reach conclusions based on the larger sample that resulted. The researchers selected only those trials that used randomized and placebo-controlled techniques: 14 studies involving 1,356 participants for the number of colds and 1,630 for the prevention of colds. The studies varied in the dosages of the herb, the duration it was taken and the species of echinacea used, and the number of participants ranged from 40 to more than 300.

The analysis concluded that echinacea reduced the risk of catching a cold by 58 percent. It also found that the herb significantly shortened the duration of a cold, but there was no general agreement about the magnitude of this effect.

“Our analysis doesn’t say that the stuff works without question,” said Dr. Craig I. Coleman, an assistant professor of pharmacy practice at the University of Connecticut, and the senior author of the paper. “But the preponderance of evidence suggests that it does.”

The authors acknowledged certain weaknesses in their study. For example, they did not examine the safety of the herbal remedy, only its effectiveness.

Dr. Bruce P. Barrett, an associate professor of family medicine at the University of Wisconsin who was not involved with the review, said he was not convinced of the value of combining the studies in a single analysis.

“If you’re testing the same intervention on the same population using the same outcome measures, then meta-analysis is a very good technique,” Dr. Barrett said. “But here every one of those things fails.” One of Dr. Barrett’s papers on echinacea was included in the analysis.

Other experts also expressed skepticism. J. David Gangemi, director of the Institute for Neutraceutical Research at Clemson University, said he found the study interesting, but added, “I think that many of the people who have dedicated their careers to clinical trials in studying these effects are not at all convinced from this analysis that there is this large reduction in incidence and duration of disease.”

Dr. Gangemi is the senior author of a 2005 study, published in The New England Journal of Medicine and included in the review, that found no benefit in the herb.

There are several possible reasons that even a carefully devised single study might fail to show an effect that actually exists. There are more than 200 species of virus that cause colds, Dr. Coleman said, and a study could test one species against which echinacea proves ineffective, while leaving open the question of whether it works for others.

In addition, some studies might not use large enough doses of the herb; others might use a species of echinacea that is less effective. Some might not have a large enough sample to find a small but statistically significant effect.

Dr. Barrett said there was probably little harm in using echinacea, and he was cautiously optimistic that the herb does have a very small positive effect.

“There’s some danger of kids getting a rash, and it would be inadvisable to give it to women in the early stages of pregnancy,” he said. “But if adults believe in echinacea, they’re going to get benefits — maybe from placebo — but they’ll get benefits.”

Dr. Coleman, who described himself as “not much of a pill taker,” hedged a bit when asked if he planned to use echinacea himself. “I’ll probably consider taking it if I feel a cold coming on,” he said. “These results have pushed me toward the idea. Whether I’m actually going to take it, well, we’ll see.”

Five alternative treatments that work

By Elizabeth Cohen : The Empowered Patient : CNN

Dr. Andrew Weil wasn't sure exactly how he hurt his knee; all he knew was that it was painful. But instead of turning to cortisone shots or heavy doses of pain medication, Weil turned to the ancient Chinese medicine practice of acupuncture. "It worked -- my knee felt much better," says Weil.

Americans spend billions of dollars each year on alternative medicine, everything from chiropractic care to hypnosis.

Weil says alternative medicine can work wonders -- acupuncture, certain herbs, guided imagery.

For example, Dr. Brian Berman, director of the Center for Integrative Medicine at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, has done a series of studies showing acupuncture's benefits for osteoarthritis of the knee.

Extensive studies have also been done on mind-body approaches such as guided imagery, and on some herbs, including St. John's wort.

But on the other hand, there also is a lot of quackery out there, Weil says. "I've seen it all, [including] products that claim to increase sexual vigor, cure cancer and allay financial anxiety."

So how do you know what works and what doesn't when it comes to alternative medicine? Just a decade ago, there weren't many well-done, independent studies on herbs, acupuncture, massage or hypnosis, so patients didn't have many facts to guide them.

But in 1999, eight academic medical centers, including Harvard, Duke and Stanford, banded together with the purpose of encouraging research and education on alternative medicine. Eight years later, the Consortium of Academic Health Centers for Integrative Medicine has 38 member universities, and has gathered evidence about what practices have solid science behind them.

Here, from experts at five of those universities, are five alternative medicine practices that are among the most promising because they have solid science behind them.

1. Acupuncture for pain

Hands, down, this was the No. 1 recommendation from our panel of experts. They also recommended acupuncture for other problems, including nausea after surgery and chemotherapy.

2. Calcium, magnesium, and vitamin B6 for PMS

Your Health Tools

When pre-menstrual syndrome rears its ugly head, gynecologist Dr. Tracy Gaudet encourages her patients to take these dietary supplements. "They can have a huge impact on moodiness, bloating, and on heavy periods," says Gaudet, who's the executive director of Duke Integrative Medicine at Duke University Medical School.

3. St. John's Wort for depression

The studies are a bit mixed on this one, but our panel of experts agreed this herb -- once thought to rid the body of evil spirits - is definitely promising. "It's worth a try for mild to moderate depression," says Weil, founder and director of the Program in Integrative Medicine at the University of Arizona. "Remember it will take six to eight weeks to see an effect." Remember, too, that St. John's wort can interfere with some medicines; the University of Maryland Medical Center has a list.

4. Guided imagery for pain and anxiety

"Go to your happy place" has become a cliché, but our experts say it really works. The technique, of course, is more complicated than that. "In guided imagery we invite you to relax and focus on breathing and transport you mentally to a different place," says Mary Jo Kreitzer, Ph.D., R.N., founder and director of the Center for Spirituality and Healing at the University of Minnesota.

There's a guided imagery demo at the University of Minnesota's Web site.

5. Glucosamine for joint pain

"It's safe, and it looks like it's effective," says Dr. Frederick Hecht, director of research at the Osher Center for Integrative Medicine at the University of California, San Francisco. "It may be the first thing that actually reverses cartilage loss in osteoarthritis."

All our experts warn that since alternative medicine is financially lucrative, a lot of charlatans have gotten into the business. They have these tips for being a savvy shopper:

1. Look for "USP" or "NSF" on the labels

"The biggest mistake people make is they don't get a good product," says Dr. Mary Hardy, medical director of the Sims/Mann-UCLA Center for Integrative Oncology. She says the stamp of approval from the United States Pharmacopoeia or NSF International, two groups with independent verification programs, means what's on the label is in the product.

2. Find a good practitioner

Make sure the alternative medicine practitioner you're going to is actually trained to practice alternative medicine. One place to start is the Consortium for Academic Health Centers for Integrative Medicine

3. Be wary of crazy claims

"Anything that sounds too good to be true probably is," says Weil.

And once you do start on your journey with alternative medicine, here's a piece of advice: Take it slow. Alternative medicine works, but sometimes not as quickly as taking a drug. "I tell people it's going to take a while," says Hardy. "I tell them to do a six- to eight-week trial, or even 12 weeks."

The Lure of Treatments Science Has Dismissed

By Abigail Zuger : NY Times Book Review ; December 25, 2007

The ailing millions who spend their money on unorthodox medical treatments may differ in their preferences for powders vs. needles vs. the sound of cracking bones, but they do share a single mantra: “I don’t care what the studies say; it works for me.”

The studies — at least the good ones — say that none of these treatments work the miracles often claimed for them. And in this contradiction lies the genesis of R. Barker Bausell’s readable, entertaining and immensely educational book, which undertakes to explain exactly why treatments that science says do not work that well are still able — even likely — to work for you.

It is probably no good recommending that every devotee of alternative medicine spend some time with this book, as should those who gobble up prescription drugs for all the wrong reasons, and the thousands of doctors out there chanting their own version of the same mantra (“I ignore what studies say, and patients love me anyway”). All these departures from scientifically validated therapies tend to be accompanied by a disdain for the statistics supporting them, and Dr. Bausell, a statistician and professor at the University of Maryland in Baltimore, has no particular magic tricks up his sleeve — just numbers, logic and a virtuoso command of the medical literature.

But a stint directing research into alternative medicine has familiarized him with the thought patterns of those who use it, those who are inclined to prescribe it and those whose research seems to support it. He writes with a sense of humor and palpable compassion for all involved, and in the regrettably likely event that he winds up preaching exclusively to the choir, his book will be no less of a tour de force.

Dr. Bausell starts out with the story of his late mother-in-law, Sarah, a concert pianist who developed painful arthritis in her old age and found her doctors to be generally useless when it came to satisfactory pain control. “So, being an independent, take-charge sort of individual, she subscribed to Prevention magazine, in order to learn more about the multiple remedies suggested in each month’s issue” for symptoms like hers.

What ensued, according to Dr. Bausell, was a predictable pattern. Every couple of months Sarah would make a triumphant phone call and announce “with great enthusiasm and conviction” that a new food or supplement or capsule had practically cured her arthritis. Unfortunately, each miracle cure was regularly replaced by a different one, in a cycle her son-in-law ruefully breaks down for detailed analysis.

He makes it crystal clear exactly how the natural history of most painful conditions conspires with the immensely complex neurological and psychological phenomenon known as the placebo effect to make almost any treatment appear to work, so long as the recipient hopes and believes it will.

With equal dexterity Dr. Bausell introduces us to Dr. Smith, a fictional physician who becomes interested in acupuncture and convinced that it helps his patients. Enthusiastically organizing a series of research studies to confirm his conviction, Dr. Smith falls victim to an even more complicated set of scientific, psychological and emotional confounders than did Sarah, all of which invalidate his science and make his treatment appear far more effective than it actually is.

It is, of course, not only research into alternative therapies that is compromised by the pitfalls Dr. Bausell describes. Exactly the same subtle problems bedevil orthodox research, and they are often the source of the contradictory studies and here-today-gone-tomorrow treatment vogues that drive patients crazy.

Nor are patients who are using alternative treatments the only ones to become all wrapped up in the soothing folds of the placebo effect. The word “placebo” has picked up some pejorative overtones in the last few decades, with connotations of trickery and deceit, cold-eyed white-coated investigators doling out sugar pills instead of the real things. In fact, though, placebos have as venerable and honorable a history as just about any medication, and are better studied than most.

Dr. Bausell explores the science behind placebos in detail: the pain relief they afford is reliable and reproducible, and for some reason tends to linger in memory as even stronger than it really is.

But is that placebo-generated pain relief real or imaginary? Patients generally roll their eyes when the argument gets to this stage, for as Dr. Bausell points out, one perfectly reasonable response to the question would be, “Who cares?”

But it turns out that the issue is more than just scientific nitpicking. Placebos may work, but their effects are characteristically mild and temporary; in fact, they are more or less indistinguishable from the effects of most alternative treatments, as the dozens of studies summarized in the book’s last 100 pages make clear.

Still, Dr. Bausell knows perfectly well that people in pain don’t care what studies say. The only study they care about is the study of themselves. And who can blame them for that?

Thus he includes a final, ingenious section titled, “How to select a placebo therapy that works,” suggesting, among other things, that consumers bent on trying alternative medicine find an appealing therapy and an enthusiastic practitioner, then plunge in wholeheartedly to maximize that placebo effect and prolong its duration for as long as possible. Pure scientists might shudder at this advice, but Sarah’s son-in-law knows better.

"SNAKE OIL SCIENCE"

The Truth About Complementary and Alternative Medicine.

By R. Barker Bausell.

Oxford. 324 Pages. $24.95.

No 'Alternative'

By Jerome Groopman, MD : WSJ Article : August 7, 2006

Some 60 million Americans use supplements, megavitamins, herbs and other so-called "alternative" treatments. Their out-of-pocket costs approach $40 billion a year. Their therapies are promoted by a vast number of self-help books, Web sites and talk shows that feature thrilling testimonials of benefits for maladies that mainstream medicine cannot remedy. But we are now learning what happens when the testimonials are subjected to objective testing. In February, the results of a large clinical trial of the supplements glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate for osteoarthritis were released. These data came on the heels of a rigorous assessment of the herb saw palmetto for symptoms of an enlarged prostate gland. Both studies failed to show clinical efficacy. All this should mark a sea change in how the public views such treatments.

* * *In the first case, some 1,583 patients with symptomatic osteoarthritis of the knee were randomly assigned to receive glucosamine, chondroitin sulfate, both supplements, the anti-inflammatory Celebrex, or placebo. The trial was sponsored by the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine, NCCAM, and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. The study found there was no overall statistical benefit except for Celebrex. Of note, 60% of the patients receiving placebo reported significant improvement.

This result was greeted without surprise by a colleague of mine who is a primary care physician. Many of her patients swear by the benefits of the supplement for their arthritis; and one of them, a woman in her 70s, never failed to press the physician to take it for her own aches and pains. When the doctor demurred, the patient eyed her with some disdain. "You doctors are so close-minded," she said. "You won't accept a treatment that comes from outside of your own world." One day, a package arrived at her office. It was a large container of glucosamine, which still sits in a cabinet, unopened. "Despite all my patients' testimonials, it didn't make sense," she told me. "Glucosamine is absorbed from the digestive tract and rapidly broken down in the body. How could this supplement survive digestion, travel through the circulation, deposit in worn-down joints, and rebuild cartilage?"

My colleague is a caring and competent clinician, and I was struck by the barb from her patient about being "close-minded." Most physicians I know feel triangulated in caring for people who pursue alternative therapies. Pointed questioning of the probity of the treatments casts the doctor in the role of adversary rather than ally. Glibly endorsing such therapies may be politically correct but, in essence, patronizes the patient, since the doctor has no objective basis to assess the value of the herb or supplement being promoted for the problem. An honest clinician questions all treatments -- ranging from an antibiotic from a pharmacy to an elixir from a health food store -- and asks if they pose real risks, offer real benefits, or both. When I was a patient with a serious problem of uncertain outcome, I felt the powerful temptation to seek a magical solution. Most doctors are sympathetic to this sensibility. But a good doctor distinguishes magic from medicine.

The widespread misconception among the public is that what is "natural" is necessarily salubrious and safe, while in fact, the natural world is filled with poisons and toxins. Some of those natural poisons, of course, can be used therapeutically: Two of the most important chemotherapy drugs, vincristine and taxol, are derived, respectively, from the periwinkle plant and the Pacific yew tree.

The patients I care for with cancer or AIDS take multiple prescription medications, and how these drugs interact with each other can be no simple matter; throw into the mix an herb of unclear composition and unknown metabolism, as well as unknown side effects, and there is a recipe for trouble. I witnessed this as the first group of pharmaceuticals against HIV were being tested during the late 1980s. There was a groundswell of demand among understandably desperate patients for alternatives to medicines like AZT that can have serious side effects and, as single agents, only modest benefit. One "natural" alternative was an extract from a Chinese cucumber termed compound Q. It was imported from Asia and taken by a number of desperate AIDS patients based on testimonials that it could eradicate HIV. The fact that the cucumber extract was used as an abortifacent in China seemed not to register, until several patients developed severe toxic reactions, including coma. Physicians and researchers who challenged compound Q were vilified as being ignorant, wed to the pharmaceutical-medical complex, or envious that a cure had arrived from outside of "mainstream" medicine.

Then there was St. John's wort. This popular herb was touted as a treatment for depression and alleged to have antiviral activity in people with HIV. It was shown to be no better than placebo for depression and, most worrisome, to interfere with the activity of the lifesaving anti-HIV protease drugs.

* * *That alternative therapies are coming under the sharp lamp of science is of some irony. In 1991, Congress passed a bill to create an Office of Alternative Medicine within the National Institutes of Health. Seven years later, this became NCCAM. Sen. Tom Harkin of Iowa was one of the main drivers behind the legislation. Mr. Harkin was said to believe that nontraditional potions and procedures were important therapies, his faith stemming in part from friends and family who testified to their importance. A collective groan was heard in the halls of university hospitals and research centers. Precious federal dollars were being diverted from "real science" to shamanism. Some alternative medicine gurus also objected, worried that their therapies would be tested "the NIH way."

The academic opponents were proven wrong -- because the fears of the gurus came true. The reason for this can largely be attributed to Stephen Straus, who directs the NCCAM. Dr. Straus is neither a naysayer nor a believer, but rather a scientist, meaning that he is agnostic about any particular therapy. Dr. Straus explained that the same rigorous metrics used to evaluate normal medicine are applied to the numerous unproven alternative treatments -- "the NIH way." The justification for spending federal funds is still hotly debated, as evidenced by an impassioned article in a recent issue of the journal Science, with a call for the Congress to re-examine the issue. But rigorous testing of popular alternative therapies is a matter of public health and informs proper medical practice. On the wall of Dr. Straus's office is a framed quote: "The plural of anecdotes is not evidence." A billion Chinese cannot be wrong, goes the old saw, but in fact they can and often are.

But it is not a matter of geography or culture. Until the 19th century, Western practitioners were badly wrong, attributing diseases to an imbalance in humors, bleeding patients and prescribing poultices and purgatives. Modern Western medicine has also embraced therapies that were later disproven. In the 1960s, surgeons tied off an artery under the breastbone in patients with angina, believing this increased circulation to the diseased heart. Many patients swore by the surgery, but when the procedure was subjected to a clinical trial, it turned out that the sham operation was equally beneficial.

Placebos are very powerful. Beyond yoga for lower back pain and acupuncture for analgesia, there has not been a study showing an unequivocal benefit of an alternative therapy when subjected to the rigor of an NIH trial. This negative outcome should not be greeted smugly, because most experimental drugs developed by pharmaceutical or biotechnology companies fail to fulfill their promise. The difference is that these companies rely on biological mechanisms to select candidate drugs for testing, rather than unsubstantiated testimonials and anecdotes.

Dr. Straus believes the public should acquire an historical perspective on the urban legends of alternative therapy. Beyond compound Q and St. John's wort, he recalled the euphoria around laetrile, the extract from apricot pits promoted as a cancer cure, that brought Steve McQueen to Mexico and to his death, and also the story that shark cartilage caused tumors to melt away because sharks never develop cancer (not true). On the other hand, one of the most important new therapies for leukemia is an arsenic derivative identified in western China as part of traditional practice that resulted in well-documented remissions; its effects on key molecules in the malignant cells have been elegantly mapped by scientists. And qualified researchers are testing components of tumeric and other spices than can inhibit melanoma and breast cancer cell growth. Science is enthusiastic when it meets reality.

Still, the failure to prove that so many popular alternative treatments have any benefit has generated resistance among the believers. The promoters of saw palmetto objected to the study, saying that the dose and preparation used in the trial were not optimal. But, in fact, the most frequently used preparation was the one studied. The clinical trial of glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate will be extended, but lacking a scientific rationale for the treatment should lower expectations about a different outcome.

How long does it take for a false messiah to be abandoned when redemption does not arrive? "Things that are wrong are ultimately set aside," Dr. Straus said, "and things that are right gain traction. There are the conflicting tides of belief and fact, and each has its own chronology. Things don't change quickly, but over time a cumulative body of evidence becomes compelling." I reflected on this when I read that one major vendor of saw palmetto asserted he would continue to promote the herb despite the new data. As science spreads in his world, doubt will chip away at blind faith, and he will find a shrinking group of believers.

Dr. Groopman is the Recanati Professor at Harvard Medical School.

Nostrums: Supplements Seem to Be No Help to Knees

By Nicholas Bakalar : NY Times Article : October 21, 2008

In 2006, researchers reported that the widely used diet supplements glucosamine and chondroitin were no more effective against osteoarthritis than a placebo, except for a small benefit in some people with arthritis of the knee. Now a new study suggests that the substances may be ineffective for them, too.

In that two-year study, researchers examined 581 knees in 357 people with osteoarthritis. They divided them into five groups to receive either glucosamine, chondroitin sulfate, the two together, celecoxib (an anti-inflammatory drug) or a sugar pill; neither the researchers nor the subjects knew who was taking what. Then they used X-rays to measure the deterioration of their knee joints.

The study, published in the October issue of Arthritis and Rheumatism, found no significant difference between any of the four treatments and the placebo.

No treatment achieved a clinically important improvement, and the disease progressed at the same rate in all groups.

Still, Dr. Allen D. Sawitzke, the lead author and an associate professor of medicine at the University of Utah, said that further study might still find some benefit.

“Our sample is too small, our time frame too short, and the technical limitations of our measuring are too great to exclude small effects,” he said.

“But if the effect were large,” he continued, “we would have caught it.”

.

It is important that I be kept informed about certain herbal or natural preparations you may be taking because of the potential for interaction with medications that I may prescribe for you.

We know for example that nearly 30 percent of women use alternative therapies to treat the symptoms of menopause. These include soy-rich foods and Black cohosh.

I have no problem with the use of glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate in the management of degenerative arthritis or Saw Palmetto for men with prostate problems.

It is strongly advised to discontinue any herbal product at least one week before undergoing general anesthesia as it has been reported that garlic, gingo and ginseng could cause bleeding when combined with commonly prescribed drugs used in surgery.

Ephedra and Mahuang found in weight loss and energy enhancing supplements can cause an irregular heart beat and an increased risk of of heart attack and stroke; ginseng may exacerbate low blood sugar; Kava and Valerian could exaggerate the impact of anesthetics; Echinacea could pose a risk of poor wound healing and infections; St John's Wort could speed up the metabolism of certain drugs as it interferes with the P450 enzyme system in the liver that the body uses to break down about half of all drugs. Because of this, St John's Wort is believed to interfere with many of the most widely prescribed medicines used for heart disease, certain seizure medicines and drugs used to prevent organ rejection after transplants.

Garlic supplements, often taken in the hope of lowering cholesterol, can seriously interfere with the drugs used to treat AIDS. St John's Wort can have the same effect and Kava has been shown to be associated with liver toxicity.

Basically what I'm trying to get across is that "natural" does not necessarily mean "safer".

Applying Science to Alternative Medicine

By William J. Broad : NY Times Article : September 30, 2008

More than 80 million adults in the United States are estimated to use some form of alternative medicine, from herbs and megavitamins to yoga and acupuncture. But while sweeping claims are made for these treatments, the scientific evidence for them often lags far behind: studies and clinical trials, when they exist at all, can be shoddy in design and too small to yield reliable insights.

Now the federal government is working hard to raise the standards of evidence, seeking to distinguish between what is effective, useless and harmful or even dangerous.

“The research has been making steady progress,” said Dr. Josephine P. Briggs, director of the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine, a division of the National Institutes of Health. “It’s reasonably new that rigorous methods are being used to study these health practices.”

The need for rigor can be striking. For instance, a 2004 Harvard study identified 181 research papers on yoga therapy reporting that it could be used to treat an impressive array of ailments — including asthma, heart disease, hypertension, depression, back pain, bronchitis, diabetes, cancer, arthritis, insomnia, lung disease and high blood pressure.

It turned out that only 40 percent of the studies used randomized controlled trials — the usual way of establishing reliable knowledge about whether a drug, diet or other intervention is really safe and effective. In such trials, scientists randomly assign patients to treatment or control groups with the aim of eliminating bias from clinician and patient decisions.

Sat Bir S. Khalsa, the study’s author and a sleep researcher at the Harvard Medical School, said an added complication was that “the vast majority of these studies have been small,” averaging 30 or fewer subjects per arm of the randomized trial. The smaller the sample size, he warned, the greater the risk of error, including false positives and false negatives.

Critics of alternative medicine have seized on that weakness. R. Barker Bausell, a senior research methodologist at the University of Maryland and the author of “Snake Oil Science” (Oxford, 2007), says small studies often have a built-in conflict of interest: they need to show positive results to win grants for larger investigations.

“All these things conspire to produce false positives,” Dr. Bausell said in an interview. “They make the results extremely questionable.”

That kind of fog is what Dr. Briggs and the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine, with a budget of $122 million this year, are trying to eliminate. Their trials tend to be longer and larger. And if a treatment shows promise, the center extends the trials to many centers, further lowering the odds of false positives and investigator bias.

For instance, the center is conducting a large study to see if extracts from the ginkgo biloba tree can slow the progression of Alzheimer’s disease. The clinical trials involve centers in California, Maryland, North Carolina and Pennsylvania and recruited more than 3,000 patients, all of them over 75. The study is to end next year.

Another large study enrolled 570 participants to see if acupuncture provided pain relief and improved function for people with osteoarthritis of the knee. In 2004, it reported positive results. Dr. Brian M. Berman, the study’s director and a professor of medicine at the University of Maryland, said the inquiry “establishes that acupuncture is an effective complement to conventional arthritis treatment.”

In an interview, Dr. Briggs said another good way to improve clinical trials was to ensure product uniformity, especially on herbal treatments. “We feel we have really influenced the standards,” she said.

Over the years, laboratories have found that up to 75 percent of the samples of ginkgo biloba failed to show the claimed levels of the active ingredient. Scientists doing a clinical trial have a large incentive to fix that kind of inconsistency.

Dr. Briggs said such investments would be likely to pay off in the future by documenting real benefits from at least some of the unorthodox treatments. “I believe that as the sensitivities of our measures improve, we’ll do a better job at detecting these modest but important effects” for disease prevention and healing, she said.

An open question is how far the new wave will go. The high costs of good clinical trials, which can run to millions of dollars, means relatively few are done in the field of alternative therapies and relatively few of the extravagant claims are closely examined.

“In tight funding times, that’s going to get worse,” said Dr. Khalsa of Harvard, who is doing a clinical trial on whether yoga can fight insomnia. “It’s a big problem. These grants are still very hard to get and the emphasis is still on conventional medicine, on the magic pill or procedure that’s going to take away all these diseases.”

Diet Supplements and Safety: Some Disquieting Data

By Dan Hurley : NY Times Article : January 16, 2007

In October 1993, during a Senate hearing on a bill to regulate herbs, vitamins and other dietary supplements on the presumption that they were safe, Senator Orrin G. Hatch, Republican of Utah, spoke up in their defense. Herbal remedies “have been on the market for centuries,” he said, adding: “In fact, most of these have been on the market for 4,000 years, and the real issue is risk. And there is not much risk in any of these products.”

That benign view was written into the bill when it was passed by both houses the following year. While the law, the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994, forbade manufacturers to claim that their products “treat, cure or prevent” any disease, it allowed them to make vaguer claims based on a standard that did not require them to do any testing. And it stated that “dietary supplements are safe within a broad range of intake, and safety problems with the supplements are relatively rare.”

But hiding in plain sight, then as now, a national database was steadily accumulating strong evidence that some supplements carry risks of injury and death, and that children may be particularly vulnerable.

Since 1983, the American Association of Poison Control Centers has kept statistics on reports of poisonings for every type of substance, including dietary supplements. That first year, there were 14,006 reports related to the use of vitamins, minerals, essential oils — which are not classified as a dietary supplement but are widely sold in supplement stores for a variety of uses — and homeopathic remedies. Herbs were not categorized that year, because they were rarely used then.

By 2005, the number had grown ninefold: 125,595 incidents were reported related to vitamins, minerals, essential oils, herbs and other supplements. In all, over the 23-year span, the association — a national organization of state and local poison centers — has received more than 1.6 million reports of adverse reactions to such products, including 251,799 that were serious enough to require hospitalization. From 1983 to 2004 there were 230 reported deaths from supplements, with the yearly numbers rising from 4 in 1994, the year the supplement bill passed, to a record 27 in 2005.

The number of deaths may be far higher. In April 2004, the Food and Drug Administration said it had received 260 reports of deaths associated with herbs and other nonvitamin, nonmineral supplements since 1989. But an unpublished study prepared in 2000 for the agency by Dr. Alexander M. Walker, then the chairman of epidemiology at the Harvard School of Public Health, concluded: “A best estimate is that less than 1 percent of serious adverse events caused by dietary supplements is reported to the F.D.A. The true proportion may well be smaller by an order of magnitude or more.”

The supplements linked to the most reactions in 2005, according to the poison control centers, were ordinary vitamins, accounting for nearly half of all the reports received that year, 62,446, including 1 death. Minerals were linked to about half as many total reports, 32,098, but that number included 13 deaths. Herbs and other specialty products accounted for still fewer total reports, 23,769, but 13 deaths. Essential oils were linked to 7,282 reports and no deaths.

Among herbs and other specialty products, melatonin and homeopathic products — prepared from minuscule amounts of substances as diverse as salt and snake venom — had the most reports of reactions in 2005. The poison centers received 2,001 reports of reactions to melatonin, marketed as a sleep aid, including 535 hospitalizations and 4 deaths. Homeopathic products, often marketed as being safe because the doses are very low, were linked to 7,049 reactions, including 564 hospitalizations and 2 deaths.

But most other types of herbs and specialty supplements also appear in the annual report. In 2005, the poison centers received 203 reports of adverse reactions to St. John’s wort, including 79 hospitalizations and 1 death. Glucosamine, with or without chondroitin, was linked to 813 adverse reactions, including 108 hospitalizations and 1 death. Echinacea was linked to 483 adverse reactions, including 55 hospitalizations, 1 of them considered life-threatening. Saw palmetto was not listed on the report.

Injuries to children under 6 account for nearly three-quarters of all the reports of adverse reactions to dietary supplements, according to the poison centers. In 2005, the most recent year for which figures are available, 48,604 children suffered reactions to vitamins alone, the ninth-largest category of substances associated with reactions in that age group.

Major medical groups and government agencies do not generally recommend vitamin or mineral supplements for children who are otherwise healthy. But an analysis of the National Maternal and Infant Health Survey, published in the journal Pediatrics in 1997, found that 54 percent of parents of preschool children gave them a vitamin or mineral supplement at least three days a week.

Advocates of the products correctly point out that the poison centers’ figures do not prove a causal link between a product and a reaction and that, in any case, far more people are injured and killed by drugs. Painkillers alone were associated with 283,253 adverse reactions in 2005, according to the poison centers, more than twice as many as with supplements. But only 3.5 percent of those reactions occurred when people took the prescribed amount of painkiller; most were from overdoses, either accidental or intentional. The same was true of asthma drugs (3.6 percent of reactions were associated with the prescribed dose) and cough and cold drugs (3.1 percent).

While reactions to vitamins, minerals and essential oils occurred at similarly low levels when people took the recommended amounts, adverse reactions linked to the recommended levels of herbs, homeopathic products and other dietary supplements accounted for 10.3 percent of all reactions to those products reported to the poison centers — about three times the level seen for most drugs.

Drugs marketed in the United States go through a rigorous F.D.A. approval process to prove that they are effective for a particular indication, with the potential risks balanced against the benefits. While the approval process has come under attack in recent years as unduly favorable to drug companies, it remains among the toughest in the world.

There is no comparable requirement for supplements. Even so, hundreds of millions of tax dollars have been spent since the early 1990s on hundreds of studies to test the possible benefits of supplements. The National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine, established by Congress in 1991 to “investigate and validate unconventional medical practices,” has a 2007 budget of more than $120 million.

Since April 2002, five large randomized trials financed by the center have found no significant benefit for St. John’s wort against major depression, echinacea against the common cold (but see new data below on this particular supplement), saw palmetto for enlarged prostate, the combination of glucosamine and chondroitin for arthritis, or black cohosh and other herbs for the hot flashes associated with menopause.

A new source of data on adverse reactions to dietary supplements will soon become available: in December, Congress passed a measure requiring the manufacturers of dietary supplements and over-the-counter drugs to inform the F.D.A. whenever consumers call them with reports of serious adverse events. The bill was signed by President Bush the day after Christmas. It is a welcome acknowledgment that “natural” does not always mean “safe.”

Dan Hurley is the author of the new book “Natural Causes: Death, Lies and Politics in America’s Vitamin and Herbal Supplement Industry” (Broadway Books), from which this essay is adapted.

Another Supplement, Under the Microscope

By Michael Manson : NY Times Article : March 13, 2007

Not so long ago, antioxidant vitamins were hailed as nature’s own weapons against chronic illness, powerful antidotes to horrid diets and failed exercise plans.

A parade of observational studies showed that people who consumed large amounts of vitamins C and E and beta carotene were usually healthier than those who ingested comparatively little. Almost overnight, it seemed, millions of consumers morphed into fervid pill poppers, and antioxidants were dolloped into an ever expanding variety of foods.

But recent and more rigorous research suggests that this silver bullet missed its mark. Most long-term prospective trials have shown that using antioxidant vitamin supplements does not prevent heart disease or cancer, with the possible exception of prostate cancer.

In a study published last month in The Journal of the American Medical Association, researchers in Europe analyzed data from 68 large trials in which more than 232,000 adults were given antioxidant supplements.

In a subset of those studies, the scientists concluded, subjects taking vitamins A and E and beta carotene saw a slightly increased risk of death compared with those who did not take supplements. (Vitamin C had no effect on mortality, the team found.)

So are America’s most popular vitamins actually harmful? Not likely, other experts say. Although antioxidant supplements have not been the cure-alls scientists had hoped for, there may yet be a place for them.

“A lot of researchers, including myself, were quite disappointed that the trials showed no benefit, particularly for vitamin E,” said Dr. Meir Stampfer, an epidemiologist at Harvard. “But I don’t think it closes the door on the antioxidant concept.”

The new study has garnered frightening headlines and vigorous criticism. Dr. Stampfer and others say its analysis is methodologically flawed, because it includes data from widely heterogeneous studies, excludes data from hundreds of others for unclear reasons and does not try to detail the causes of increased mortality among supplement users.

“It just seems implausible that antioxidants should be killing you by several different means,” said Dr. Jeffrey Blumberg, a nutrition professor at Tufts. “I don’t buy it.”

Dr. Andrew Shao, vice president of the Council for Responsible Nutrition, a trade group for the supplement industry, said, “Most of these patients already had disease, so the conclusions simply aren’t relevant to a healthy population.”

The study’s authors defended their methods. “Previous studies have included a select group of trials, risking cherry-picking, either good or bad,” said the lead researcher, Dr. Goran Bjelakovic of the University of Nis in Serbia. “Our systematic review is based on more trials and more participants, and hence is more powerful.”

Other studies of healthy adults taking antioxidants have also proved disappointing. After tracking nearly 40,000 women for a decade, researchers at Harvard found that those taking vitamin E were just as likely as others to suffer cardiovascular disease and cancer.

“There was no evidence of harm, but there was no benefit, either,” said Dr. Julie E. Buring, an author of the study. “It’s really too bad. Vitamin E had been incredibly promising.”

For a few consumers, it may still be promising. In the Harvard study, a subgroup of participants older than 65 who took vitamin E did have significantly fewer heart attacks and strokes than those who did not, although the finding may have been due to chance. Vitamin E and selenium have been strongly associated with a reduced risk of prostate cancer in a few studies.

“There still may be subsets of people who are very responsive to the benefits of antioxidants,” said Dr. Blumberg, who serves on scientific advisory boards for some supplement companies.

The essential premise behind antioxidant supplements remains intact, researchers say. Oxygen-free radicals, a normal byproduct of metabolism, damage cellular DNA unless antioxidant compounds remove them. Oxidative damage is characteristic of a wide variety of chronic diseases.

Still, faced with solid basic science but a litany of null results in the clinic, many scientists are calling for a change in tactics. Some theorize that a randomized clinical trial, the gold standard for medical research, may not be the best way to evaluate vitamin supplements.

“You just can’t do this kind of study with something like cancer, which can take 20 years to develop in an initially healthy person,” said Dr. Bruce Ames, a biochemist at the University of California, Berkeley.

Moreover, cancer and heart disease arise from a powerful confluence of genetic and environmental influences. In hindsight, it was naïve of scientists and consumers to hope that the relatively short-term addition of one or two antioxidants would be enough to counteract decades of poor diet and inadequate exercise, not to mention the genome.

Antioxidants remain essential to health. That much has not changed.

But for most of us, the time has come to let go of the notion that high-dose supplements provide a magic wand against disease. The good news is that a diet rich in fruits and vegetables contains literally thousands of antioxidant nutrients. Prevention begins in the kitchen.

Echinacea Helps Colds, Major Review Shows

By Nicholas Bakalar : NY Times Article : July 24, 2007

Echinacea helps banish colds. Echinacea has no effect on colds. The verdict seems to shift with each new scientific study of the herbal remedy.

In the latest twist, a review of more than 700 studies has concluded that echinacea has a substantial effect in preventing colds and in limiting their duration.

The paper, published in the July issue of The Lancet Infectious Diseases, used statistical techniques to combine the results of existing studies and reach conclusions based on the larger sample that resulted. The researchers selected only those trials that used randomized and placebo-controlled techniques: 14 studies involving 1,356 participants for the number of colds and 1,630 for the prevention of colds. The studies varied in the dosages of the herb, the duration it was taken and the species of echinacea used, and the number of participants ranged from 40 to more than 300.

The analysis concluded that echinacea reduced the risk of catching a cold by 58 percent. It also found that the herb significantly shortened the duration of a cold, but there was no general agreement about the magnitude of this effect.

“Our analysis doesn’t say that the stuff works without question,” said Dr. Craig I. Coleman, an assistant professor of pharmacy practice at the University of Connecticut, and the senior author of the paper. “But the preponderance of evidence suggests that it does.”

The authors acknowledged certain weaknesses in their study. For example, they did not examine the safety of the herbal remedy, only its effectiveness.

Dr. Bruce P. Barrett, an associate professor of family medicine at the University of Wisconsin who was not involved with the review, said he was not convinced of the value of combining the studies in a single analysis.

“If you’re testing the same intervention on the same population using the same outcome measures, then meta-analysis is a very good technique,” Dr. Barrett said. “But here every one of those things fails.” One of Dr. Barrett’s papers on echinacea was included in the analysis.

Other experts also expressed skepticism. J. David Gangemi, director of the Institute for Neutraceutical Research at Clemson University, said he found the study interesting, but added, “I think that many of the people who have dedicated their careers to clinical trials in studying these effects are not at all convinced from this analysis that there is this large reduction in incidence and duration of disease.”

Dr. Gangemi is the senior author of a 2005 study, published in The New England Journal of Medicine and included in the review, that found no benefit in the herb.

There are several possible reasons that even a carefully devised single study might fail to show an effect that actually exists. There are more than 200 species of virus that cause colds, Dr. Coleman said, and a study could test one species against which echinacea proves ineffective, while leaving open the question of whether it works for others.

In addition, some studies might not use large enough doses of the herb; others might use a species of echinacea that is less effective. Some might not have a large enough sample to find a small but statistically significant effect.

Dr. Barrett said there was probably little harm in using echinacea, and he was cautiously optimistic that the herb does have a very small positive effect.

“There’s some danger of kids getting a rash, and it would be inadvisable to give it to women in the early stages of pregnancy,” he said. “But if adults believe in echinacea, they’re going to get benefits — maybe from placebo — but they’ll get benefits.”

Dr. Coleman, who described himself as “not much of a pill taker,” hedged a bit when asked if he planned to use echinacea himself. “I’ll probably consider taking it if I feel a cold coming on,” he said. “These results have pushed me toward the idea. Whether I’m actually going to take it, well, we’ll see.”

Five alternative treatments that work

By Elizabeth Cohen : The Empowered Patient : CNN

Dr. Andrew Weil wasn't sure exactly how he hurt his knee; all he knew was that it was painful. But instead of turning to cortisone shots or heavy doses of pain medication, Weil turned to the ancient Chinese medicine practice of acupuncture. "It worked -- my knee felt much better," says Weil.

Americans spend billions of dollars each year on alternative medicine, everything from chiropractic care to hypnosis.

Weil says alternative medicine can work wonders -- acupuncture, certain herbs, guided imagery.

For example, Dr. Brian Berman, director of the Center for Integrative Medicine at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, has done a series of studies showing acupuncture's benefits for osteoarthritis of the knee.

Extensive studies have also been done on mind-body approaches such as guided imagery, and on some herbs, including St. John's wort.

But on the other hand, there also is a lot of quackery out there, Weil says. "I've seen it all, [including] products that claim to increase sexual vigor, cure cancer and allay financial anxiety."

So how do you know what works and what doesn't when it comes to alternative medicine? Just a decade ago, there weren't many well-done, independent studies on herbs, acupuncture, massage or hypnosis, so patients didn't have many facts to guide them.

But in 1999, eight academic medical centers, including Harvard, Duke and Stanford, banded together with the purpose of encouraging research and education on alternative medicine. Eight years later, the Consortium of Academic Health Centers for Integrative Medicine has 38 member universities, and has gathered evidence about what practices have solid science behind them.

Here, from experts at five of those universities, are five alternative medicine practices that are among the most promising because they have solid science behind them.

1. Acupuncture for pain

Hands, down, this was the No. 1 recommendation from our panel of experts. They also recommended acupuncture for other problems, including nausea after surgery and chemotherapy.

2. Calcium, magnesium, and vitamin B6 for PMS

Your Health Tools

When pre-menstrual syndrome rears its ugly head, gynecologist Dr. Tracy Gaudet encourages her patients to take these dietary supplements. "They can have a huge impact on moodiness, bloating, and on heavy periods," says Gaudet, who's the executive director of Duke Integrative Medicine at Duke University Medical School.

3. St. John's Wort for depression

The studies are a bit mixed on this one, but our panel of experts agreed this herb -- once thought to rid the body of evil spirits - is definitely promising. "It's worth a try for mild to moderate depression," says Weil, founder and director of the Program in Integrative Medicine at the University of Arizona. "Remember it will take six to eight weeks to see an effect." Remember, too, that St. John's wort can interfere with some medicines; the University of Maryland Medical Center has a list.

4. Guided imagery for pain and anxiety

"Go to your happy place" has become a cliché, but our experts say it really works. The technique, of course, is more complicated than that. "In guided imagery we invite you to relax and focus on breathing and transport you mentally to a different place," says Mary Jo Kreitzer, Ph.D., R.N., founder and director of the Center for Spirituality and Healing at the University of Minnesota.

There's a guided imagery demo at the University of Minnesota's Web site.

5. Glucosamine for joint pain