- RETIREMENT ANNOUNCEMENT

- HOME PAGE

- "MYCHART" the new patient portal

- BELMONT MEDICAL ASSOCIATES

- MOUNT AUBURN HOSPITAL

- EMERGENCIES

- PRACTICE PHILOSOPHY

- MY RESUME

- TELEMEDICINE CONSULTATION

- CONTACT ME

- LAB RESULTS

- ePRESCRIPTIONS

- eREFERRALS

- RECORD RELEASE

- MEDICAL SCRIBE

- PHYSICIAN ASSISTANT (PA)

- Medicare Annual Wellness Visit

- Case management/Social work

- Quality Care Measures

- Emergency closing notice

- FEEDBACK

- Talking to your doctor

- Choosing..... and losing a doctor

- INDEX A - Z

- ALLERGIC REACTIONS

- Alternative Medicine

- Alzheimer's Disease

- Bladder Problems

- Blood disorders

- Cancer Concerns

- GENETIC TESTING FOR HEREDITARY CANCER

- Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

- Controversial Concerns

- CPR : Learn and save a life

- CRP : Inflammatory marker

- Diabetes Management

- Dizziness, Vertigo,Tinnitus and Hearing Loss

- EXERCISE

- FEMALE HEALTH

-

GASTROINTESTINAL topics

- Appendicitis

- BRAT diet

- Celiac Disease or Sprue

- Crohn's Disease

- Gastroenterologists for Colon Cancer Screening

- Colonoscopy PREP

- Constipation

- Gluten sensitivity, but not celiac disease

- Heartburn and GERD

- Hemorrhoids and Anal fissure

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- NASH : Non Alcoholic Steato Hepatitis

- FEET PROBLEMS

- HEART RELATED topics

-

INFECTIOUS DISEASES

- Antibiotic Resistance

- Cat bites >

- Clostridia difficile infection - the "antibiotic associated germ"

- CORONA VIRUS

- Dengue Fever and Chikungunya Fever

- Food borne illnesses

- Shingles Vaccine

- Hepatitis B

- Hepatitis C

- Herpes

- Influenza

- Helicobacter pylori - the "ulcer germ"

- HIV Screening

- Lyme and other tick borne diseases

- Measles

- Meningitis

- MRSA (Staph infection)

- Norovirus

- Sexually Transmitted Diseases

- Shingles (Herpes Zoster)

- Sinusitis

- West Nile Virus

- Whooping Cough (Pertussis)

- Zika virus and pregnancy

- INSURANCE related topics

- KIDNEY STONES

- LEG CRAMPS

- LIBRARY for patients

- LIFE DECISIONS

- MALE HEALTH

- Medication/Drug side effects

- MEDICAL MARIJUANA

- MENTAL HEALTH

- Miscellaneous Articles

-

NUTRITION - EXERCISE - WEIGHT

- Cholesterol : New guidelines for treatment

- Advice to lower your cholesterol

- Cholesterol : Control

- Cholesterol : Raising your HDL Level

- Exercise

- Food : Making Smart Choices

- Food : Making Poor Choices

- Food : Grape Fruit and Drug Interaction

- Food : Vitamins, Minerals and Supplements

- Omega 3 fatty acids

- Vitamin B12 deficiency

- Vitamin D

- Weight Loss

- ORTHOPEDICS

- PAIN

- PATIENTS' RIGHTS

- SKIN

- SLEEP

- SMOKING

- STROKE

- THYROID

- SUBSTANCE ABUSE

- Travel and Vaccination

- TREMOR

- Warfarin Anticoagulation

- OTHER STUFF FOLLOWS

- Fact or Opinion?

- Hippocratic Oath

- FREE ADVICE.......for what its worth!

- LAUGHTER.....is the best medicine

- Physicians Pet Peeves

- PHOTO ALBUM - its not all work!

- Cape Town, South Africa

- Tribute page

- The 100 Club

- Free Wi-Fi

Hepatitis C

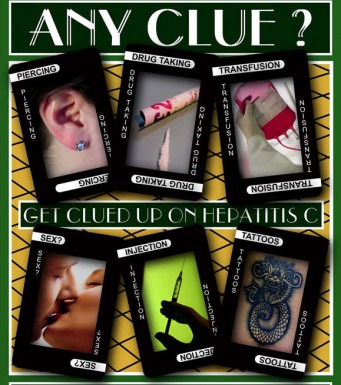

If you answer "YES" to any of these questions, you may have contracted Hepatitis C without your knowledge.

Health Danger of Parties Past

By Melinda Beck : WSJ : September 20, 2010

Most people think their wild-child past is just that—in the past. But some former party animals may be carrying a harmful reminder of their youth and not know it.

People who used intravenous drugs, snorted cocaine with a shared straw, or had an unsterile tattoo or body piercing could be infected with hepatitis C and not realize it. The virus, which spreads via blood-to-blood contact, can cause no symptoms for decades while silently destroying the liver.

Some people may have innocently been infected if they had a blood transfusion before 1992, when the blood supply began to be screened for the virus. Others may have contracted the virus simply by sharing a toothbrush or a razor. More than three million Americans have been diagnosed with hep C, and health experts say at least that many more are unaware that they have it.

"There's a huge reservoir of people who made a few bad decisions many years ago. Now they're successful business people, lawyers, doctors, school principals, and they don't know they are carrying this," says Joseph Galati, medical director of the Center for Liver Disease and Transplantation at Houston's Methodist Hospital. In the meantime, he says, "they could be doing things like drinking alcohol that accelerate the disease or transmitting it to other people."

Hep C, first identified in 1989, is today the leading reason for liver transplants and causes about 12,000 deaths in the U.S. each year. In most cases, the infection becomes chronic, inflaming the liver for years, but often with no apparent symptoms unless the inflammation becomes severe. In about 20% of cases, it progresses to cirrhosis, a severe scarring that shuts down liver function. And about 20% of those cirrhosis cases become liver cancer.

About 20,000 people are diagnosed with hepatitis C each year, and some two-thirds of those are middle-aged, having contracted the disease 20 or 30 years ago.

There is no vaccine against hep C, unlike for hepatitis A and B, which are liver diseases caused by different viruses. Hep C can be cured with a year-long course of chemotherapy drugs, but only about 50% of patients respond to them. A host of new medications now in clinical trials could work faster, and raise the cure rate as high as 80%, according to early results.

Hep C can be diagnosed with an inexpensive blood test that checks for antibodies—if doctors think to look for it. If that test is positive, another test can determine if the virus is still active. (In about 15% of hep C cases, the virus goes away on its own, although the antibodies may still be present.)

The Sleeper Virus

A regular annual checkup may reveal elevated liver enzymes. But many people with hep C have normal enzyme levels, and only vague symptoms like fatigue or joint pain, until the damage is well advanced.

"I never had any symptoms. I've had major surgery twice and nobody picked up on this," says a Houston nurse who was diagnosed with hep C in December at age 59. She thinks she was exposed to the virus in 1980, when she was accidentally stuck with a needle while caring for a patient. Her hep C was only found because a new job required the test for hep C antibodies. By then, 35% of her liver was damaged from cirrhosis. She is currently undergoing treatment in a clinical trial with Dr. Galati.

Even minute blood drops—from borrowing a toothbrush or piercing several friends' ears with the same needle—can transmit the virus. "Any blood-to-blood transition route can spread it, no matter how microscopic," says Melissa Palmer, medical director at New York University's Hepatology Associates in Plainview, NY.

"People may have done something once and forgotten about it, like share a $1 or a $100 bill to snort cocaine. The blood vessels in the nose are very weak and could bleed a little, and then the blood gets passed to the next person," says Dr. Palmer.

For now, the standard course of treatment for hep C is two chemotherapy drugs—interferon in weekly injections and ribavirin as pills three times a day—for either 24 or 48 weeks, an arduous regime that can cost more than $50,000 a year. Side effects can include fatigue, weakness, muscle and joint pain, hair loss, nausea and depression. Some patients need additional drugs to boost their red and white blood cells, which the chemo drugs deplete. Some have to stop the treatment because it can be so debilitating.

Hepatitis A Through E

Hepatitis is an inflammation of the liver, generally caused by viruses, with symptoms ranging from slight to severe. Versions A through C are the most common.

"I was really, really sick for a while—I had to hide under the wedding gowns so I could nap," says Sidney Merry, 53, who works for a bridal retailer in Houston. Routine blood tests spotted her hep C, which she thinks she got from a blood transfusion in the 1970s, and later started treatment with Dr. Galati. Ms. Merry stuck with the program and is now free of the virus. She helps counsel other patients undergoing treatment.

Ms. Merry says two of her friends died of hep C they declined to treat, and her own mother died of liver cancer at age 53, from what Ms. Merry suspects may also have been hep C. "This touches many lives—but it's so unspoken about and misunderstood," she says.

Two new drugs on the horizon—boceprevir by Merck & Co. and telaprevir by Vertex Pharmaceuticals

In July, the FDA approved a synthetic form of interferon, called Infergen, by Three Rivers Pharmaceuticals LLC, for use in daily injections for patients who don't respond to the first course of treatment.

In some cases, doctors are advising hep C patients to postpone treatment until the new drugs come on the market. But Dr. Galati, who has been the principal investigator for several industry-sponsored clinical trials, notes that the new drugs will be in addition to the current ones, so waiting for the new regimes won't allow patients to avoid the side effects.

Unborn babies can acquire hep C from infected mothers. Kathryn Maloney had complained of fatigue for years before she was diagnosed with hep C in 2005. "Turns out I had it my whole life and didn't know," says Ms. Maloney, 29, an accountant in Houston.

Since there was no obvious source of her infection, Dr. Galati suggested that her mother, Pamela Grant, be tested too. She tested positive as well, though she has no idea when or where she was exposed. She and her daughter underwent treatment together. They also took part in a clinical trial for one of the new medications and are now free of the virus.

Some patients opt to forgo treatment, since only about 20% progress to cirrhosis. But doctors can't tell in advance which cases will progress. Meanwhile, drinking alcohol, smoking cigarettes and carrying excess weight make cirrhosis more likely.

Some health experts are urging that the general public be screened for hep C; the blood test for antibodies costs only about $12. Short of that, liver specialists urge anyone who might have been exposed, no matter how or how long ago or how well they feel now, to tell their doctors and be tested.

Since hep C can carry a lingering stigma of past drug use, even though there are many other ways to contract it, Dr. Galati says some primary-care physicians routinely hand patients a list of risk factors and say, "If you fit into any of these categories, you should get tested. You don't need to tell me which one."

Hepatitis C : An Overview

is a viral disease that leads to swelling (inflammation) of the liver.

Alternative Names

Non-A or non-B hepatitis

Causes

Hepatitis C infection is caused by hepatitis C virus (HCV). People who may be at risk for hepatitis C are those who:

Symptoms

Many people who are infected with the hepatitis C do not have symptoms.

If the infection has been present for many years, the liver may be permanently scarred -- a condition called cirrhosis. In many cases, there may be no symptoms of the disease until cirrhosis has developed.

The following symptoms could occur with hepatitis C infection:

Hepatitis C is often found during blood tests for a routine physical or other medical procedure.

Treatment

There is no cure for hepatitis C, but medications in some cases can suppress the virus for a long period of time.

Some patients with hepatitis C benefit from treatment with interferon alpha or a combination of interferon alpha and ribavirin. Interferon alpha is given by injection just under the skin and has a number of side effects, including:

Ribavirin is a capsule taken twice daily. The major side effect is low red blood cells (anemia). Ribavirin also causes birth defects. Women should avoid getting pregnant during, and for 6 months following treatment.

A "sustained response" means that the patient remains free of hepatitis C virus 6 months after stopping treatment. This does not mean that the patient is cured, but that the levels of active hepatitis C virus in the body are very low and are probably not causing more or as much damage.

Rest may be recommended during the acute phase of the disease when the symptoms are most severe. All patients with hepatitis C should get vaccinated against hepatitis A and B.

People with hepatitis C should also be careful not to take vitamins, nutritional supplements, or new over-the-counter medications without first discussing it with their health care provider.

People with hepatitis C should avoid any substances that are toxic to the liver (hepatotoxic), including alcohol. Even moderate amounts of alcohol speed up the progression of hepatitis C, and alcohol reduces the effectiveness of treatment.

Support Groups

You can often ease the stress of illness by joining a support group of people who share common experiences and problems.

Outlook (Prognosis)

Hepatitis C is one of the most common causes of chronic liver disease in the U.S. today. People with this condition may have:

Prevention

Avoid contact with blood or blood products whenever possible. Health care workers should follow precautions when handling blood and bodily fluids.

Do not inject illicit drugs, and especially do not share needles with anyone. Be careful when getting tattoos and body piercings.

Sexual transmission is low among stable, monogamous couples. A partner should be screened for hepatitis C. If the partner is negative, the current recommendations are to make no changes in sexual practices.

People who have sex outside of a monogamous relationship should practice safer sex behaviors to avoid hepatitis C as well as sexually transmitted diseases, including HIV and hepatitis B.

Currently there is no vaccine for hepatitis C.

Hepatitis C: A Viral Illness Hard to Treat but Also Cured

By Peter Jaret

NY Times Article : August 14, 2008

In Brief:

Hepatitis C can take decades to show up as damage to the liver.

Chronic viral hepatitis is now the leading reason for liver transplants.

Current combination therapy can be individualized to cure chronic infections in 40 to 80 percent of cases.

The consequences of being infected with hepatitis C can take years to appear. So while new cases of the disease have fallen sharply over the past few decades, many people infected years ago are only beginning to learn they carry the virus, and to grapple with its potentially serious effects.

For many, there is good news. Half of all chronic infections can now be cured through a therapy using a combination of drugs. But hepatitis C remains a wily virus, often lying low for years and then following a course so unpredictable that doctors sometimes aren’t sure whether to recommend treatment or advise patients to watch and wait.

The biggest obstacle to effective treatment remains the fact that a majority of the estimated 3.2 million Americans who harbor chronic hepatitis C aren’t even aware they have it. In four out of five people, there are no symptoms when the infection first occurs.

“Most of the people we see discovered they have chronic hepatitis C when they went to donate blood or had a physical exam in order to get insurance,” said Dr. Bruce R. Bacon, director of the division of gastroenterology and hepatology at Saint Louis University School of Medicine.

Almost a third of those exposed to hepatitis C recover fully; their immune systems rout the virus and eliminate it. About 70 percent develop chronic infections, which carry a significant risk of cirrhosis, or scarring, of the liver and liver cancer. Paradoxically, people who become sickest soon after being infected are most likely to fight off the virus, whereas those who have few if any initial symptoms are at greatest danger of suffering persistent infection.

The treatment currently recommended for chronic hepatitis C combines ribavirin, an antiviral drug, with interferon, a substance that increases the immune system’s virus-killing power. The treatment offers a lifelong cure for more than half of patients. But because the drugs are expensive and can have serious side effects, and because the course of disease varies so much from person to person, the decision to start therapy poses tough questions.

“About one-third of people with chronic hepatitis will go on to develop cirrhosis of the liver,” said Dr. Jay H. Hoofnagle, director of the Liver Disease Research Branch at the National Institutes of Health. “Only 5 to 10 percent will develop liver cancer. In other words, many people can live perfectly well with chronic hepatitis infection and never have any problems. The trouble is we can’t tell who will do well and who will die of the disease.”

Nor can doctors predict with certainty how patients will respond to the combination therapy. In 25 to 30 percent of patients, interferon produces anxiety and depression, sometimes so extreme that sufferers have attempted suicide. It can also cause debilitating flu-like symptoms.

“I can usually get anyone through two or three months of interferon and ribavirin. Beyond that, it gets really tough,” Dr. Hoofnagle said. “At least 10 percent of patients can’t make it through the recommended course of therapy.”

Fortunately, physicians are getting better at optimizing the benefits and controlling some of the unwanted side effects, thanks in part to new insights into the virus. Researchers have discovered that hepatitis C occurs in at least six forms, called genotypes. Genotype 1 is the most common and also the hardest to treat, requiring 48 weeks of treatment. Only about 40 percent of people with this subtype get rid of the virus. Genotypes 2 and 3 can be successfully treated in just 24 weeks, eliminating the virus in about 80 percent of cases.

The more rapidly virus levels begin to fall in patients, the better the odds of a cure. By monitoring levels of the virus in blood, some doctors say, it’s now possible to individualize the course of treatment.

“I call it the accordion effect,” said Dr. Ira Jacobsen, chief of the division of gastroenterology and hepatology at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York. “If virus levels drop off very quickly, we can shorten the course of therapy. If the response is slow, we can lengthen it, sometimes to as much as 72 weeks, and improve the chances of success.”

Shortening the course of therapy remains controversial because of the risk of relapse after the treatment is stopped. Relapse occurs when lingering viruses not eradicated by the medication multiply and surge back.

Antidepressant drugs, meanwhile, are being employed to ease psychiatric side effects. And doctors are getting better at predicting who will suffer depression after starting interferon.

“Not surprisingly, people with a history of depression are at greater risk,” said Dr. Francis Lotrich, assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of Pittsburgh. He and his colleagues have also observed that people with chronic sleep problems are also more likely to have trouble with depression. The reason is not clear, but studies are under way to see if improving people’s sleep with the use of insomnia medication or other techniques can lower the risk of psychiatric side effects.

The best medicine is prevention, and it’s here that the biggest gains have been won against hepatitis C. The number of new infections per year in the United States has plummeted from 240,000 in the 1980s to about 19,000 in 2006. Experts credit a screening test that now prevents hepatitis C from spreading via blood transfusions and organ transplantation, as well as public health messages aimed at discouraging the use of shared needles, which is the leading route of transmission.

In the absence of an effective vaccine, such messages, backed up by intensified surveillance, will remain the chief defense against this virus. In 2003, chronic hepatitis B and C became notifiable diseases that must be reported to federal health officials, enabling them to track new cases nationwide. In 2004, New York State began its own enhanced viral hepatitis surveillance network.

Two years ago, the program demonstrated its usefulness when officials in the Erie County Department of Health detected a cluster of cases centered in one zip code in suburban Buffalo.

“All we had at first was a bunch of dots on a map,” said Dr. Anthony J. Billittier IV, the Erie County health commissioner. Investigators went into the community and identified about 20 young people who were injecting drugs and sometimes sharing needles. The county responded by intensifying prevention efforts, including a free needle exchange.

“We’ve made a lot of progress against hepatitis C, but there’s still a lot to do,” Dr. Billittier said. “One one thing we know about this virus is it’s not going away.”

var user_type = "1"; var s_prop20 = "37466615"; var s_account = "nytimesglobal,nythealth"; var dcsvid = "37466615"; var regstatus = "registered"; var s_pageName = "/ref/health/healthguide/esn-hepatitisC-ess.html"; var s_channel = "health"; var s_prop1 = "health timeseessential"; Tacoda_AMS_DDC_addPair( "t_section","Health" );

Hepatitis C rises among young people

Mass. officials suspect jump tied to drug use

By Stephen Smith

Boston Globe | May 8, 2007

Hepatitis C infections among Massachusetts adolescents and young adults rose dramatically from 2001 to 2005, new data show, prompting health officials to warn doctors statewide to screen and educate patients about the blood-borne disease.

Confirmed and suspected cases of hepatitis C among 15- to 25-year-olds climbed from 254 in 2001 to at least 784 in 2005, the state Department of Public Health found. In Boston, about 100 cases of the potentially painful and life-threatening liver infection were reported in 2006 -- the most this decade.

Massachusetts is better at tracking infectious diseases than many other states, making it difficult to compare state data with nationwide trends.

The spike in hepatitis C, an illness most often spread by drug needles tainted with the virus, emerges during a period of epidemic heroin use in Massachusetts.

That is almost certainly no coincidence, said John Auerbach , the state's public health commissioner. "I suspect there is a direct correlation between the increase in hepatitis C among younger people and the increase in injection drug use and heroin use, in particular," Auerbach said. "It is terribly tragic, but it is very consistent with the pattern of risk that goes along with injection-drug use."

State health authorities acknowledged that some of the rise may be attributable to more diligent reporting of the disease by doctors.

To reverse the rising tide of both hepatitis C and heroin use, the state's Bureau of Substance Abuse Services has recently established pilot programs at community health centers and at Boston Medical Center to routinely ask every patient about possible drug use.

At the same time, the state is enlisting retired doctors and nurses to help review reports of positive hepatitis C tests, and interview adolescents and young adults to better understand the trajectory of the disease.

"We know that injecting just once with a contaminated needle can give you hepatitis C," said Dr. Alfred DeMaria , the state's director of communicable disease control.

Auerbach and other authorities said they believe that the increase in hepatitis C infections reflects a resurgence of the disease among young drug users, not among the broader population. The rise in infections, they said, demonstrates just how easily the virus can travel on the tip of a needle, or even a tube used to inhale heroin or other narcotics.

State figures show that young adults account for a growing share of all admissions to substance-abuse programs and that across age groups, heroin remains a favorite source of getting high: 50 percent of drug-treatment admissions are linked to heroin.

Dr. Maureen Jonas , a pediatric liver specialist at Children's Hospital Boston , regularly witnesses the consequences of that behavior.

"I am seeing, sadly, a fair number of 13-, 14-, 15-, 16-year-olds with IV drug use and hepatitis C," Jonas said. "A lot of them -- not all of them -- knew that the person whose needle they shared had hepatitis of some sort.

"They just have a typical adolescent frame of mind that 'it's not going to happen to me,' " said Jonas, who sits on the medical advisory board of the New England chapter of the American Liver Foundation .

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that about 3.2 million Americans are chronically infected with hepatitis C. In some cases, patients suffer jaundice and intense belly pains and then the disease goes away. In other patients, the virus remains latent for decades. In the worst cases, patients develop liver failure that can require a transplant.

Most of the carriers of hepatitis C in the United States are believed to be in their 40s, 50s, and 60s, having come of age during an era when drug experimentation and dirty needles were rampant, and the ramifications were not fully appreciated. That was also a period when the nation's supply of blood products was not routinely screened for the presence of the virus. The disease can also be spread during sex or by sharing toothbrushes or razors -- although it is far more difficult to contract the virus by those means.

A March report from the CDC found that rates of acute, symptomatic hepatitis C were declining in all age groups. But acute cases are a small fraction of all hepatitis C infections; in 2005, for instance, the number of newly acute patients was just 671 nationally.

The Massachusetts data, unlike the CDC's, includes everyone who tested positive for the disease, even those without symptoms.

Dr. John Ward , director of CDC's Division of Viral Hepatitis, said the agency does not have the money to do a better job of tracking hepatitis. Improving surveillance is important "both so we can actually see how many cases there are but also for patients' own care," he said.

Liver specialists typically will not begin treatment of hepatitis C until patients stop using illegal drugs and are in a setting where it is more likely that they can adhere to a regimen of powerful medications that can send the virus into remission, Jonas said.

Once adolescents successfully complete hepatitis treatment, which can take six months to a year, doctors then give them a warning, Jonas said.

"We tell them, 'You're not immune to this now. You can go out and shoot up one more time and you can get it all over again and you haven't done yourself any favors,' " the doctor said. "They look at you a little surprised when you say that."

=0)document.write(unescape('%3C')+'\!-'+'-'); //--> PT_AC_Iterate();

Please discuss this with me.

A simple blood test is available to check for past exposure.

Untreated Hepatitis C can lead to the development of cirrhosis.

This CAN be prevented.

Patients with the following should be offered HCV treatment:

- Did you receive a blood transfusion or blood products before June 1992?

- Did you ever do drugs by injection, even once?

- Have you had multiple sexual partners or had a sex partner who was Hepatitis C positive?

Health Danger of Parties Past

By Melinda Beck : WSJ : September 20, 2010

Most people think their wild-child past is just that—in the past. But some former party animals may be carrying a harmful reminder of their youth and not know it.

People who used intravenous drugs, snorted cocaine with a shared straw, or had an unsterile tattoo or body piercing could be infected with hepatitis C and not realize it. The virus, which spreads via blood-to-blood contact, can cause no symptoms for decades while silently destroying the liver.

Some people may have innocently been infected if they had a blood transfusion before 1992, when the blood supply began to be screened for the virus. Others may have contracted the virus simply by sharing a toothbrush or a razor. More than three million Americans have been diagnosed with hep C, and health experts say at least that many more are unaware that they have it.

"There's a huge reservoir of people who made a few bad decisions many years ago. Now they're successful business people, lawyers, doctors, school principals, and they don't know they are carrying this," says Joseph Galati, medical director of the Center for Liver Disease and Transplantation at Houston's Methodist Hospital. In the meantime, he says, "they could be doing things like drinking alcohol that accelerate the disease or transmitting it to other people."

Hep C, first identified in 1989, is today the leading reason for liver transplants and causes about 12,000 deaths in the U.S. each year. In most cases, the infection becomes chronic, inflaming the liver for years, but often with no apparent symptoms unless the inflammation becomes severe. In about 20% of cases, it progresses to cirrhosis, a severe scarring that shuts down liver function. And about 20% of those cirrhosis cases become liver cancer.

About 20,000 people are diagnosed with hepatitis C each year, and some two-thirds of those are middle-aged, having contracted the disease 20 or 30 years ago.

There is no vaccine against hep C, unlike for hepatitis A and B, which are liver diseases caused by different viruses. Hep C can be cured with a year-long course of chemotherapy drugs, but only about 50% of patients respond to them. A host of new medications now in clinical trials could work faster, and raise the cure rate as high as 80%, according to early results.

Hep C can be diagnosed with an inexpensive blood test that checks for antibodies—if doctors think to look for it. If that test is positive, another test can determine if the virus is still active. (In about 15% of hep C cases, the virus goes away on its own, although the antibodies may still be present.)

The Sleeper Virus

- There is no vaccine for hepatitis C, which was first identified in 1989.

- It can cause no symptoms for decades while silently destroying the liver.

- Hep C can be detected with a blood test, but you usually need to ask for this.

- 3.2 million Americans have been diagnosed with hep C, and doctors say at least that many more don't know they have it.

- 85% of cases become chronic, and 20% of cases develop into cirrhosis.

A regular annual checkup may reveal elevated liver enzymes. But many people with hep C have normal enzyme levels, and only vague symptoms like fatigue or joint pain, until the damage is well advanced.

"I never had any symptoms. I've had major surgery twice and nobody picked up on this," says a Houston nurse who was diagnosed with hep C in December at age 59. She thinks she was exposed to the virus in 1980, when she was accidentally stuck with a needle while caring for a patient. Her hep C was only found because a new job required the test for hep C antibodies. By then, 35% of her liver was damaged from cirrhosis. She is currently undergoing treatment in a clinical trial with Dr. Galati.

Even minute blood drops—from borrowing a toothbrush or piercing several friends' ears with the same needle—can transmit the virus. "Any blood-to-blood transition route can spread it, no matter how microscopic," says Melissa Palmer, medical director at New York University's Hepatology Associates in Plainview, NY.

"People may have done something once and forgotten about it, like share a $1 or a $100 bill to snort cocaine. The blood vessels in the nose are very weak and could bleed a little, and then the blood gets passed to the next person," says Dr. Palmer.

For now, the standard course of treatment for hep C is two chemotherapy drugs—interferon in weekly injections and ribavirin as pills three times a day—for either 24 or 48 weeks, an arduous regime that can cost more than $50,000 a year. Side effects can include fatigue, weakness, muscle and joint pain, hair loss, nausea and depression. Some patients need additional drugs to boost their red and white blood cells, which the chemo drugs deplete. Some have to stop the treatment because it can be so debilitating.

Hepatitis A Through E

Hepatitis is an inflammation of the liver, generally caused by viruses, with symptoms ranging from slight to severe. Versions A through C are the most common.

- Hep A: Transmitted via contaminated water or food, particularly in countries with poor hygiene. Symptoms include fatigue, fever, abdominal pain, depression and jaundice. Permanent liver damage is rare. Vaccine recommended for all children at 1 year.

- Hep B: Two billion people world-wide have been infected with hep B, mostly through infected blood or body fluids. It can become chronic and lead to cirrhosis and liver cancer, but most adults clear the virus without treatment and are then immune. Vaccination is now required for many college students and healthcare workers.

- Hep C: Spread by blood-to-blood transmission, with few symptoms either in early stages or for decades later. About 20% of chronic cases develop into cirrhosis or liver cancer. Curable in about 50% of cases by chemotherapy.

- Hep D: Caused by a small RNA virus that only propagates in the presence of hep B, greatly increasing the chance of cancer, cirrhosis and death. Hep B vaccine will prevent illness from D.

- Hep E: Transmitted by fecal-oral contamination in unsanitary conditions. Patients are generally very ill for the first few weeks of infection then the virus usually clears on it own. Vaccine is being tested.

"I was really, really sick for a while—I had to hide under the wedding gowns so I could nap," says Sidney Merry, 53, who works for a bridal retailer in Houston. Routine blood tests spotted her hep C, which she thinks she got from a blood transfusion in the 1970s, and later started treatment with Dr. Galati. Ms. Merry stuck with the program and is now free of the virus. She helps counsel other patients undergoing treatment.

Ms. Merry says two of her friends died of hep C they declined to treat, and her own mother died of liver cancer at age 53, from what Ms. Merry suspects may also have been hep C. "This touches many lives—but it's so unspoken about and misunderstood," she says.

Two new drugs on the horizon—boceprevir by Merck & Co. and telaprevir by Vertex Pharmaceuticals

In July, the FDA approved a synthetic form of interferon, called Infergen, by Three Rivers Pharmaceuticals LLC, for use in daily injections for patients who don't respond to the first course of treatment.

In some cases, doctors are advising hep C patients to postpone treatment until the new drugs come on the market. But Dr. Galati, who has been the principal investigator for several industry-sponsored clinical trials, notes that the new drugs will be in addition to the current ones, so waiting for the new regimes won't allow patients to avoid the side effects.

Unborn babies can acquire hep C from infected mothers. Kathryn Maloney had complained of fatigue for years before she was diagnosed with hep C in 2005. "Turns out I had it my whole life and didn't know," says Ms. Maloney, 29, an accountant in Houston.

Since there was no obvious source of her infection, Dr. Galati suggested that her mother, Pamela Grant, be tested too. She tested positive as well, though she has no idea when or where she was exposed. She and her daughter underwent treatment together. They also took part in a clinical trial for one of the new medications and are now free of the virus.

Some patients opt to forgo treatment, since only about 20% progress to cirrhosis. But doctors can't tell in advance which cases will progress. Meanwhile, drinking alcohol, smoking cigarettes and carrying excess weight make cirrhosis more likely.

Some health experts are urging that the general public be screened for hep C; the blood test for antibodies costs only about $12. Short of that, liver specialists urge anyone who might have been exposed, no matter how or how long ago or how well they feel now, to tell their doctors and be tested.

Since hep C can carry a lingering stigma of past drug use, even though there are many other ways to contract it, Dr. Galati says some primary-care physicians routinely hand patients a list of risk factors and say, "If you fit into any of these categories, you should get tested. You don't need to tell me which one."

Hepatitis C : An Overview

is a viral disease that leads to swelling (inflammation) of the liver.

Alternative Names

Non-A or non-B hepatitis

Causes

Hepatitis C infection is caused by hepatitis C virus (HCV). People who may be at risk for hepatitis C are those who:

- Have been on long-term kidney dialysis

- Have regular contact with blood at work (for instance, as a healthcare worker)

- Have unprotected sexual contact with a person who has hepatitis C

- Inject street drugs or share a needle with someone who has hepatitis C

- Received a blood transfusion before July 1992

- Received blood, blood products, or solid organs from a donor who has hepatitis C

- Share personal items such as toothbrushes and razors with someone who has hepatitis C

- Were born to a hepatitis C-infected mother

Symptoms

Many people who are infected with the hepatitis C do not have symptoms.

If the infection has been present for many years, the liver may be permanently scarred -- a condition called cirrhosis. In many cases, there may be no symptoms of the disease until cirrhosis has developed.

The following symptoms could occur with hepatitis C infection:

- Abdominal pain (right upper abdomen)

- Ascites (fluid in the abdominal cavity)

- Bleeding varices (dilated veins in the esophagus)

- Dark urine

- Fatigue

- Generalized itching

- Jaundice

- Loss of appetite

- Low-grade fever

- Nausea

- Pale or clay-colored stools

- Vomiting

Hepatitis C is often found during blood tests for a routine physical or other medical procedure.

- Elevated liver enzymes

- ELISA assay to detect hepatitis C antibody

- Hepatitis C PCR test

- Hepatitis C genotype. Six genotypes exist. Most Americans have genotype 1 infection, which is the most difficult to treat.

- Hepatitis virus serology

- Liver biopsy

Treatment

There is no cure for hepatitis C, but medications in some cases can suppress the virus for a long period of time.

Some patients with hepatitis C benefit from treatment with interferon alpha or a combination of interferon alpha and ribavirin. Interferon alpha is given by injection just under the skin and has a number of side effects, including:

- Depression

- Fatigue

- Fever

- Flu-like symptoms

- Headache

- Irritability

- Loss of appetite

- Low white blood cell counts

- Nausea

- Thinning of hair

- Vomiting

Ribavirin is a capsule taken twice daily. The major side effect is low red blood cells (anemia). Ribavirin also causes birth defects. Women should avoid getting pregnant during, and for 6 months following treatment.

A "sustained response" means that the patient remains free of hepatitis C virus 6 months after stopping treatment. This does not mean that the patient is cured, but that the levels of active hepatitis C virus in the body are very low and are probably not causing more or as much damage.

Rest may be recommended during the acute phase of the disease when the symptoms are most severe. All patients with hepatitis C should get vaccinated against hepatitis A and B.

People with hepatitis C should also be careful not to take vitamins, nutritional supplements, or new over-the-counter medications without first discussing it with their health care provider.

People with hepatitis C should avoid any substances that are toxic to the liver (hepatotoxic), including alcohol. Even moderate amounts of alcohol speed up the progression of hepatitis C, and alcohol reduces the effectiveness of treatment.

Support Groups

You can often ease the stress of illness by joining a support group of people who share common experiences and problems.

Outlook (Prognosis)

Hepatitis C is one of the most common causes of chronic liver disease in the U.S. today. People with this condition may have:

- Chronic liver infection

- Cirrhosis

- Need for a liver transplant

- Chronic hepatitis

- Cirrhosis

Prevention

Avoid contact with blood or blood products whenever possible. Health care workers should follow precautions when handling blood and bodily fluids.

Do not inject illicit drugs, and especially do not share needles with anyone. Be careful when getting tattoos and body piercings.

Sexual transmission is low among stable, monogamous couples. A partner should be screened for hepatitis C. If the partner is negative, the current recommendations are to make no changes in sexual practices.

People who have sex outside of a monogamous relationship should practice safer sex behaviors to avoid hepatitis C as well as sexually transmitted diseases, including HIV and hepatitis B.

Currently there is no vaccine for hepatitis C.

Hepatitis C: A Viral Illness Hard to Treat but Also Cured

By Peter Jaret

NY Times Article : August 14, 2008

In Brief:

Hepatitis C can take decades to show up as damage to the liver.

Chronic viral hepatitis is now the leading reason for liver transplants.

Current combination therapy can be individualized to cure chronic infections in 40 to 80 percent of cases.

The consequences of being infected with hepatitis C can take years to appear. So while new cases of the disease have fallen sharply over the past few decades, many people infected years ago are only beginning to learn they carry the virus, and to grapple with its potentially serious effects.

For many, there is good news. Half of all chronic infections can now be cured through a therapy using a combination of drugs. But hepatitis C remains a wily virus, often lying low for years and then following a course so unpredictable that doctors sometimes aren’t sure whether to recommend treatment or advise patients to watch and wait.

The biggest obstacle to effective treatment remains the fact that a majority of the estimated 3.2 million Americans who harbor chronic hepatitis C aren’t even aware they have it. In four out of five people, there are no symptoms when the infection first occurs.

“Most of the people we see discovered they have chronic hepatitis C when they went to donate blood or had a physical exam in order to get insurance,” said Dr. Bruce R. Bacon, director of the division of gastroenterology and hepatology at Saint Louis University School of Medicine.

Almost a third of those exposed to hepatitis C recover fully; their immune systems rout the virus and eliminate it. About 70 percent develop chronic infections, which carry a significant risk of cirrhosis, or scarring, of the liver and liver cancer. Paradoxically, people who become sickest soon after being infected are most likely to fight off the virus, whereas those who have few if any initial symptoms are at greatest danger of suffering persistent infection.

The treatment currently recommended for chronic hepatitis C combines ribavirin, an antiviral drug, with interferon, a substance that increases the immune system’s virus-killing power. The treatment offers a lifelong cure for more than half of patients. But because the drugs are expensive and can have serious side effects, and because the course of disease varies so much from person to person, the decision to start therapy poses tough questions.

“About one-third of people with chronic hepatitis will go on to develop cirrhosis of the liver,” said Dr. Jay H. Hoofnagle, director of the Liver Disease Research Branch at the National Institutes of Health. “Only 5 to 10 percent will develop liver cancer. In other words, many people can live perfectly well with chronic hepatitis infection and never have any problems. The trouble is we can’t tell who will do well and who will die of the disease.”

Nor can doctors predict with certainty how patients will respond to the combination therapy. In 25 to 30 percent of patients, interferon produces anxiety and depression, sometimes so extreme that sufferers have attempted suicide. It can also cause debilitating flu-like symptoms.

“I can usually get anyone through two or three months of interferon and ribavirin. Beyond that, it gets really tough,” Dr. Hoofnagle said. “At least 10 percent of patients can’t make it through the recommended course of therapy.”

Fortunately, physicians are getting better at optimizing the benefits and controlling some of the unwanted side effects, thanks in part to new insights into the virus. Researchers have discovered that hepatitis C occurs in at least six forms, called genotypes. Genotype 1 is the most common and also the hardest to treat, requiring 48 weeks of treatment. Only about 40 percent of people with this subtype get rid of the virus. Genotypes 2 and 3 can be successfully treated in just 24 weeks, eliminating the virus in about 80 percent of cases.

The more rapidly virus levels begin to fall in patients, the better the odds of a cure. By monitoring levels of the virus in blood, some doctors say, it’s now possible to individualize the course of treatment.

“I call it the accordion effect,” said Dr. Ira Jacobsen, chief of the division of gastroenterology and hepatology at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York. “If virus levels drop off very quickly, we can shorten the course of therapy. If the response is slow, we can lengthen it, sometimes to as much as 72 weeks, and improve the chances of success.”

Shortening the course of therapy remains controversial because of the risk of relapse after the treatment is stopped. Relapse occurs when lingering viruses not eradicated by the medication multiply and surge back.

Antidepressant drugs, meanwhile, are being employed to ease psychiatric side effects. And doctors are getting better at predicting who will suffer depression after starting interferon.

“Not surprisingly, people with a history of depression are at greater risk,” said Dr. Francis Lotrich, assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of Pittsburgh. He and his colleagues have also observed that people with chronic sleep problems are also more likely to have trouble with depression. The reason is not clear, but studies are under way to see if improving people’s sleep with the use of insomnia medication or other techniques can lower the risk of psychiatric side effects.

The best medicine is prevention, and it’s here that the biggest gains have been won against hepatitis C. The number of new infections per year in the United States has plummeted from 240,000 in the 1980s to about 19,000 in 2006. Experts credit a screening test that now prevents hepatitis C from spreading via blood transfusions and organ transplantation, as well as public health messages aimed at discouraging the use of shared needles, which is the leading route of transmission.

In the absence of an effective vaccine, such messages, backed up by intensified surveillance, will remain the chief defense against this virus. In 2003, chronic hepatitis B and C became notifiable diseases that must be reported to federal health officials, enabling them to track new cases nationwide. In 2004, New York State began its own enhanced viral hepatitis surveillance network.

Two years ago, the program demonstrated its usefulness when officials in the Erie County Department of Health detected a cluster of cases centered in one zip code in suburban Buffalo.

“All we had at first was a bunch of dots on a map,” said Dr. Anthony J. Billittier IV, the Erie County health commissioner. Investigators went into the community and identified about 20 young people who were injecting drugs and sometimes sharing needles. The county responded by intensifying prevention efforts, including a free needle exchange.

“We’ve made a lot of progress against hepatitis C, but there’s still a lot to do,” Dr. Billittier said. “One one thing we know about this virus is it’s not going away.”

var user_type = "1"; var s_prop20 = "37466615"; var s_account = "nytimesglobal,nythealth"; var dcsvid = "37466615"; var regstatus = "registered"; var s_pageName = "/ref/health/healthguide/esn-hepatitisC-ess.html"; var s_channel = "health"; var s_prop1 = "health timeseessential"; Tacoda_AMS_DDC_addPair( "t_section","Health" );

Hepatitis C rises among young people

Mass. officials suspect jump tied to drug use

By Stephen Smith

Boston Globe | May 8, 2007

Hepatitis C infections among Massachusetts adolescents and young adults rose dramatically from 2001 to 2005, new data show, prompting health officials to warn doctors statewide to screen and educate patients about the blood-borne disease.

Confirmed and suspected cases of hepatitis C among 15- to 25-year-olds climbed from 254 in 2001 to at least 784 in 2005, the state Department of Public Health found. In Boston, about 100 cases of the potentially painful and life-threatening liver infection were reported in 2006 -- the most this decade.

Massachusetts is better at tracking infectious diseases than many other states, making it difficult to compare state data with nationwide trends.

The spike in hepatitis C, an illness most often spread by drug needles tainted with the virus, emerges during a period of epidemic heroin use in Massachusetts.

That is almost certainly no coincidence, said John Auerbach , the state's public health commissioner. "I suspect there is a direct correlation between the increase in hepatitis C among younger people and the increase in injection drug use and heroin use, in particular," Auerbach said. "It is terribly tragic, but it is very consistent with the pattern of risk that goes along with injection-drug use."

State health authorities acknowledged that some of the rise may be attributable to more diligent reporting of the disease by doctors.

To reverse the rising tide of both hepatitis C and heroin use, the state's Bureau of Substance Abuse Services has recently established pilot programs at community health centers and at Boston Medical Center to routinely ask every patient about possible drug use.

At the same time, the state is enlisting retired doctors and nurses to help review reports of positive hepatitis C tests, and interview adolescents and young adults to better understand the trajectory of the disease.

"We know that injecting just once with a contaminated needle can give you hepatitis C," said Dr. Alfred DeMaria , the state's director of communicable disease control.

Auerbach and other authorities said they believe that the increase in hepatitis C infections reflects a resurgence of the disease among young drug users, not among the broader population. The rise in infections, they said, demonstrates just how easily the virus can travel on the tip of a needle, or even a tube used to inhale heroin or other narcotics.

State figures show that young adults account for a growing share of all admissions to substance-abuse programs and that across age groups, heroin remains a favorite source of getting high: 50 percent of drug-treatment admissions are linked to heroin.

Dr. Maureen Jonas , a pediatric liver specialist at Children's Hospital Boston , regularly witnesses the consequences of that behavior.

"I am seeing, sadly, a fair number of 13-, 14-, 15-, 16-year-olds with IV drug use and hepatitis C," Jonas said. "A lot of them -- not all of them -- knew that the person whose needle they shared had hepatitis of some sort.

"They just have a typical adolescent frame of mind that 'it's not going to happen to me,' " said Jonas, who sits on the medical advisory board of the New England chapter of the American Liver Foundation .

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that about 3.2 million Americans are chronically infected with hepatitis C. In some cases, patients suffer jaundice and intense belly pains and then the disease goes away. In other patients, the virus remains latent for decades. In the worst cases, patients develop liver failure that can require a transplant.

Most of the carriers of hepatitis C in the United States are believed to be in their 40s, 50s, and 60s, having come of age during an era when drug experimentation and dirty needles were rampant, and the ramifications were not fully appreciated. That was also a period when the nation's supply of blood products was not routinely screened for the presence of the virus. The disease can also be spread during sex or by sharing toothbrushes or razors -- although it is far more difficult to contract the virus by those means.

A March report from the CDC found that rates of acute, symptomatic hepatitis C were declining in all age groups. But acute cases are a small fraction of all hepatitis C infections; in 2005, for instance, the number of newly acute patients was just 671 nationally.

The Massachusetts data, unlike the CDC's, includes everyone who tested positive for the disease, even those without symptoms.

Dr. John Ward , director of CDC's Division of Viral Hepatitis, said the agency does not have the money to do a better job of tracking hepatitis. Improving surveillance is important "both so we can actually see how many cases there are but also for patients' own care," he said.

Liver specialists typically will not begin treatment of hepatitis C until patients stop using illegal drugs and are in a setting where it is more likely that they can adhere to a regimen of powerful medications that can send the virus into remission, Jonas said.

Once adolescents successfully complete hepatitis treatment, which can take six months to a year, doctors then give them a warning, Jonas said.

"We tell them, 'You're not immune to this now. You can go out and shoot up one more time and you can get it all over again and you haven't done yourself any favors,' " the doctor said. "They look at you a little surprised when you say that."

=0)document.write(unescape('%3C')+'\!-'+'-'); //--> PT_AC_Iterate();

Please discuss this with me.

A simple blood test is available to check for past exposure.

Untreated Hepatitis C can lead to the development of cirrhosis.

This CAN be prevented.

Patients with the following should be offered HCV treatment:

- Detectable HCV RNA levels >50 IU/mL

- Persistently elevated ALT values

- A liver biopsy with portal or bridging fibrosis and at least moderate inflammation and necrosis

- Abstinence from alcohol

- Hepatitis A vaccination

- Hepatitis B vaccination for seronegative persons with risk factors for HBV