- RETIREMENT ANNOUNCEMENT

- HOME PAGE

- "MYCHART" the new patient portal

- BELMONT MEDICAL ASSOCIATES

- MOUNT AUBURN HOSPITAL

- EMERGENCIES

- PRACTICE PHILOSOPHY

- MY RESUME

- TELEMEDICINE CONSULTATION

- CONTACT ME

- LAB RESULTS

- ePRESCRIPTIONS

- eREFERRALS

- RECORD RELEASE

- MEDICAL SCRIBE

- PHYSICIAN ASSISTANT (PA)

- Medicare Annual Wellness Visit

- Case management/Social work

- Quality Care Measures

- Emergency closing notice

- FEEDBACK

- Talking to your doctor

- Choosing..... and losing a doctor

- INDEX A - Z

- ALLERGIC REACTIONS

- Alternative Medicine

- Alzheimer's Disease

- Bladder Problems

- Blood disorders

- Cancer Concerns

- GENETIC TESTING FOR HEREDITARY CANCER

- Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

- Controversial Concerns

- CPR : Learn and save a life

- CRP : Inflammatory marker

- Diabetes Management

- Dizziness, Vertigo,Tinnitus and Hearing Loss

- EXERCISE

- FEMALE HEALTH

-

GASTROINTESTINAL topics

- Appendicitis

- BRAT diet

- Celiac Disease or Sprue

- Crohn's Disease

- Gastroenterologists for Colon Cancer Screening

- Colonoscopy PREP

- Constipation

- Gluten sensitivity, but not celiac disease

- Heartburn and GERD

- Hemorrhoids and Anal fissure

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- NASH : Non Alcoholic Steato Hepatitis

- FEET PROBLEMS

- HEART RELATED topics

-

INFECTIOUS DISEASES

- Antibiotic Resistance

- Cat bites >

- Clostridia difficile infection - the "antibiotic associated germ"

- CORONA VIRUS

- Dengue Fever and Chikungunya Fever

- Food borne illnesses

- Shingles Vaccine

- Hepatitis B

- Hepatitis C

- Herpes

- Influenza

- Helicobacter pylori - the "ulcer germ"

- HIV Screening

- Lyme and other tick borne diseases

- Measles

- Meningitis

- MRSA (Staph infection)

- Norovirus

- Sexually Transmitted Diseases

- Shingles (Herpes Zoster)

- Sinusitis

- West Nile Virus

- Whooping Cough (Pertussis)

- Zika virus and pregnancy

- INSURANCE related topics

- KIDNEY STONES

- LEG CRAMPS

- LIBRARY for patients

- LIFE DECISIONS

- MALE HEALTH

- Medication/Drug side effects

- MEDICAL MARIJUANA

- MENTAL HEALTH

- Miscellaneous Articles

-

NUTRITION - EXERCISE - WEIGHT

- Cholesterol : New guidelines for treatment

- Advice to lower your cholesterol

- Cholesterol : Control

- Cholesterol : Raising your HDL Level

- Exercise

- Food : Making Smart Choices

- Food : Making Poor Choices

- Food : Grape Fruit and Drug Interaction

- Food : Vitamins, Minerals and Supplements

- Omega 3 fatty acids

- Vitamin B12 deficiency

- Vitamin D

- Weight Loss

- ORTHOPEDICS

- PAIN

- PATIENTS' RIGHTS

- SKIN

- SLEEP

- SMOKING

- STROKE

- THYROID

- SUBSTANCE ABUSE

- Travel and Vaccination

- TREMOR

- Warfarin Anticoagulation

- OTHER STUFF FOLLOWS

- Fact or Opinion?

- Hippocratic Oath

- FREE ADVICE.......for what its worth!

- LAUGHTER.....is the best medicine

- Physicians Pet Peeves

- PHOTO ALBUM - its not all work!

- Cape Town, South Africa

- Tribute page

- The 100 Club

- Free Wi-Fi

Meningococcal Meningitis

Quelling a Killer: The Case For the Meningococcal Vaccine

Melinda Beck : WSJ Article : August 5, 2008

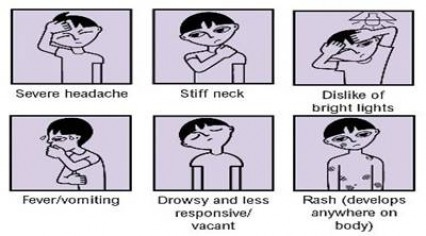

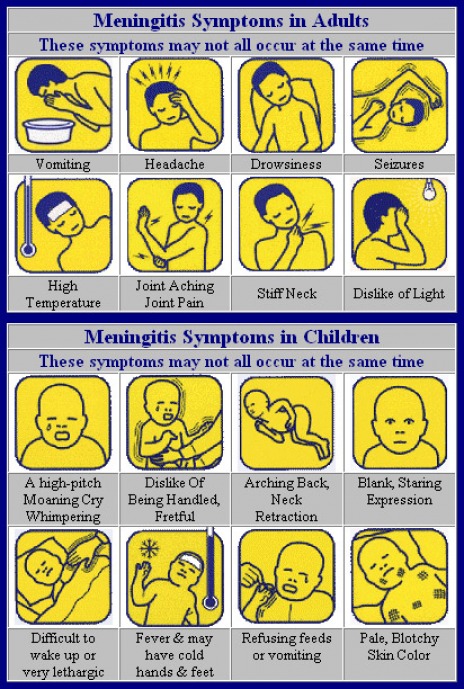

The stories sound chillingly similar. A healthy teenager comes down with what seems like the flu, then gets rapidly weaker, spikes a high fever, starts vomiting and breaks out in a rash. By the time he or she gets to the hospital, infection is overwhelming the body's defenses and shutting down vital organs.

David Pasick, a 13-year-old in Wall Township, N.J., was dead in less than 24 hours. Evan Bozof, a Georgia college student, lingered for 26 days while doctors amputated all four limbs in a futile attempt to save him.

MORE

For more information on meninigococcal meningitis, see:

• www.menactra.com - Sanofi Pasteur

• www.nmaus.org - The National Meningitis Association

• www.acha.org - American College Health Association

Meningococcal meningitis strikes just 1,400 to 2,800 Americans a year -- but with terrifying speed and consequences. Roughly 10% of victims die, often hours after symptoms set in. About 15% of those who survive are left with brain damage, hearing loss or amputations; gangrene sets in rapidly if the disease disrupts blood flow to the limbs. Many victims are adolescents and college kids living away from home for the first time.

As a new TV ad points out, the disease is largely preventable with a vaccine called Menactra, licensed in the U.S. in 2005. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention now recommends Menactra for all 11-to- 18-year-olds. As of 2006, however, only 12% of those eligible had received the vaccine. Sanofi Pasteur, the manufacturer, expects the rate to rise to 50% this year. Even so, that leaves tens of millions of teenagers unprotected.

That's partly because adolescents tend to steer clear of the doctor's office. "Parents are supposed to take their child to the pediatrician every year, and that happens till they're about age six," says Carol J. Baker, a professor of pediatrics at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston. "Then parents start forgetting. Pediatricians don't nag them and schools don't require it."

The CDC is pushing the idea of an adolescent doctor visit to discuss a range of health issues as well as get the meningitis vaccine, a diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis booster and the human papilloma virus shot for girls. But unlike infants and toddlers, who don't have much say in their vaccines, "adolescents often need to be educated about the need," says Dr. Baker.

Starting this fall, New Jersey will require sixth graders to be vaccinated against meningococcal meningitis. Other states require college students to be vaccinated or sign a waiver saying that they have been informed and opted not to have it.

About 15% to 20% of the population carries the meningococcal bacterium without having any symptoms. But such carriers can transmit it to people who are more susceptible, via sneezing, coughing, kissing or sharing drinks or cigarettes. That's why the disease often hits people living in close quarters like college dorms and sleep-away camps. Teens who are run down and sleep-deprived are especially vulnerable, and the lack of supervision means that symptoms aren't always recognized early.

"A parent would have that gut instinct that this isn't a simple flu -- but a sorority sister or a roommate might not realize it," says Katherine Karlsrud, a New York City pediatrician.

"Minutes count," notes Candie Benn of San Diego, whose daughter, Melanie, came down with the disease on Christmas Eve in 1995 during her freshman year in college. "We got her to the hospital in 40 minutes and her veins were collapsing. I was still thinking she had the flu and they're telling me she has a 50% chance of living," Ms. Benn says. Melanie survived -- but only after three months in intensive care with skin grafts, two months of rehab, a kidney transplant and amputations of both legs and arms.

The Benns and other families were devastated to learn, too late, that there was a vaccine against meningococcal meningitis available even in the 1990s, called Metamune, that might have saved their children. But it wasn't as effective as the new version and few people knew of it or that meningococcal meningitis was such a threat. Several families banded together in 2002 to form the National Meningitis Association, www.nmaus.org, which works to spread awareness both of the disease and the vaccine, funded in part by Sanofi.

"My son was an honor student, pre-med, gorgeous, happy," says Evan's mother, Lynn Bozof, the association's executive director. "We went through 26 days where we saw his hands and feet turn black as the gangrene set in. He lost his kidney function and his liver function and had 10 hours of Grand Mal seizures, and to think that all this could have been prevented with a vaccine that we just didn't know about. That's why it's so important to get the message out now."

Menactra lasts eight to ten years, long enough to take even 11 year olds through the high-risk early college years. (The incidence of meningococcal meningitis drops by about half, to about 1 case in 200,000, in adults, so the CDC does not recommend the vaccine for them as well.) It protects against four of the five strains of meningococcal meningitis, which account for 70% of cases in the U.S. It's not made with live virus, so there is no danger of getting the disease from the shot, nor does it contain the preservative thimerosal. The injection costs $80 to $100, but is covered by most insurers. Side effects are minimal. Some people have pain and swelling at the injection site, and a handful have come down with Guillain-Barre syndrome (GBS), a neurological disorder, after receiving Menactra. People who have been diagnosed with GBS are advised not to get Menactra.

That worries some vaccine critics, particularly when Menactra and the HPV vaccine are given together. "This the first time we have ever given adolescents multiple vaccines. Where are the studies that look at whether or not this is a healthy thing to do over the long term?" asks Barbara Loe Fisher, co-founder of the National Vaccine Information Center, a nonprofit activist group. She notes that the U.S. government now recommends 69 doses of 16 different vaccines for kids between 12 hours and 18 years old -- triple the number in the 1980s.

Paul Offit, chief of infectious diseases at Children's Hospital in Philadelphia, says that even if a link to GBS were proven, "you have a 20-fold greater chance of getting meningococcal meningitis without the vaccine than of getting GBS from the vaccine, and even if you get GBS, you'll likely recover. ... Statistically, the choice is very clear."

Getting vaccinated "isn't always at the top of people's priorities, or kids say, 'oooh, I don't like shots'," says Melanie Benn, now 31 and a social worker. "But people need to know that this exists and, by the way, you can prevent it."

Melinda Beck : WSJ Article : August 5, 2008

The stories sound chillingly similar. A healthy teenager comes down with what seems like the flu, then gets rapidly weaker, spikes a high fever, starts vomiting and breaks out in a rash. By the time he or she gets to the hospital, infection is overwhelming the body's defenses and shutting down vital organs.

David Pasick, a 13-year-old in Wall Township, N.J., was dead in less than 24 hours. Evan Bozof, a Georgia college student, lingered for 26 days while doctors amputated all four limbs in a futile attempt to save him.

MORE

For more information on meninigococcal meningitis, see:

• www.menactra.com - Sanofi Pasteur

• www.nmaus.org - The National Meningitis Association

• www.acha.org - American College Health Association

Meningococcal meningitis strikes just 1,400 to 2,800 Americans a year -- but with terrifying speed and consequences. Roughly 10% of victims die, often hours after symptoms set in. About 15% of those who survive are left with brain damage, hearing loss or amputations; gangrene sets in rapidly if the disease disrupts blood flow to the limbs. Many victims are adolescents and college kids living away from home for the first time.

As a new TV ad points out, the disease is largely preventable with a vaccine called Menactra, licensed in the U.S. in 2005. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention now recommends Menactra for all 11-to- 18-year-olds. As of 2006, however, only 12% of those eligible had received the vaccine. Sanofi Pasteur, the manufacturer, expects the rate to rise to 50% this year. Even so, that leaves tens of millions of teenagers unprotected.

That's partly because adolescents tend to steer clear of the doctor's office. "Parents are supposed to take their child to the pediatrician every year, and that happens till they're about age six," says Carol J. Baker, a professor of pediatrics at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston. "Then parents start forgetting. Pediatricians don't nag them and schools don't require it."

The CDC is pushing the idea of an adolescent doctor visit to discuss a range of health issues as well as get the meningitis vaccine, a diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis booster and the human papilloma virus shot for girls. But unlike infants and toddlers, who don't have much say in their vaccines, "adolescents often need to be educated about the need," says Dr. Baker.

Starting this fall, New Jersey will require sixth graders to be vaccinated against meningococcal meningitis. Other states require college students to be vaccinated or sign a waiver saying that they have been informed and opted not to have it.

About 15% to 20% of the population carries the meningococcal bacterium without having any symptoms. But such carriers can transmit it to people who are more susceptible, via sneezing, coughing, kissing or sharing drinks or cigarettes. That's why the disease often hits people living in close quarters like college dorms and sleep-away camps. Teens who are run down and sleep-deprived are especially vulnerable, and the lack of supervision means that symptoms aren't always recognized early.

"A parent would have that gut instinct that this isn't a simple flu -- but a sorority sister or a roommate might not realize it," says Katherine Karlsrud, a New York City pediatrician.

"Minutes count," notes Candie Benn of San Diego, whose daughter, Melanie, came down with the disease on Christmas Eve in 1995 during her freshman year in college. "We got her to the hospital in 40 minutes and her veins were collapsing. I was still thinking she had the flu and they're telling me she has a 50% chance of living," Ms. Benn says. Melanie survived -- but only after three months in intensive care with skin grafts, two months of rehab, a kidney transplant and amputations of both legs and arms.

The Benns and other families were devastated to learn, too late, that there was a vaccine against meningococcal meningitis available even in the 1990s, called Metamune, that might have saved their children. But it wasn't as effective as the new version and few people knew of it or that meningococcal meningitis was such a threat. Several families banded together in 2002 to form the National Meningitis Association, www.nmaus.org, which works to spread awareness both of the disease and the vaccine, funded in part by Sanofi.

"My son was an honor student, pre-med, gorgeous, happy," says Evan's mother, Lynn Bozof, the association's executive director. "We went through 26 days where we saw his hands and feet turn black as the gangrene set in. He lost his kidney function and his liver function and had 10 hours of Grand Mal seizures, and to think that all this could have been prevented with a vaccine that we just didn't know about. That's why it's so important to get the message out now."

Menactra lasts eight to ten years, long enough to take even 11 year olds through the high-risk early college years. (The incidence of meningococcal meningitis drops by about half, to about 1 case in 200,000, in adults, so the CDC does not recommend the vaccine for them as well.) It protects against four of the five strains of meningococcal meningitis, which account for 70% of cases in the U.S. It's not made with live virus, so there is no danger of getting the disease from the shot, nor does it contain the preservative thimerosal. The injection costs $80 to $100, but is covered by most insurers. Side effects are minimal. Some people have pain and swelling at the injection site, and a handful have come down with Guillain-Barre syndrome (GBS), a neurological disorder, after receiving Menactra. People who have been diagnosed with GBS are advised not to get Menactra.

That worries some vaccine critics, particularly when Menactra and the HPV vaccine are given together. "This the first time we have ever given adolescents multiple vaccines. Where are the studies that look at whether or not this is a healthy thing to do over the long term?" asks Barbara Loe Fisher, co-founder of the National Vaccine Information Center, a nonprofit activist group. She notes that the U.S. government now recommends 69 doses of 16 different vaccines for kids between 12 hours and 18 years old -- triple the number in the 1980s.

Paul Offit, chief of infectious diseases at Children's Hospital in Philadelphia, says that even if a link to GBS were proven, "you have a 20-fold greater chance of getting meningococcal meningitis without the vaccine than of getting GBS from the vaccine, and even if you get GBS, you'll likely recover. ... Statistically, the choice is very clear."

Getting vaccinated "isn't always at the top of people's priorities, or kids say, 'oooh, I don't like shots'," says Melanie Benn, now 31 and a social worker. "But people need to know that this exists and, by the way, you can prevent it."

Meningitis Booster Is Recommended

By Gardiner Harris : NY Times : October 27, 2010

Federal vaccine advisers, by a bare majority, on Wednesday recommended that 15-year-olds be given a booster dose of a vaccine against meningococcal meningitis, a rare but deadly disease that mostly strikes college freshmen.

The reason for the recommendation is that two popular vaccines against the disease do not seem to work as well as hoped. Instead of providing 10 years of protection, the vaccines may work only for five years or less.

That is not long enough to protect teenagers and young adults through the riskiest years because the vaccine is usually given at 11 or 12 years of age. The hope is that a booster dose at 15 would yield protection through the first few years of college, when outbreaks occur most often.

Members of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices debated whether to recommend that the first dose simply be delayed by three or four years or to add a second dose. The vaccine is about $100 a dose, and the disease is rare. So adding a second dose ensures that every death averted would be expensive. Federal officials estimated that the current strategy prevents nine deaths each year, that delaying the first dose would prevent 14 deaths and that adding a second dose would prevent 24 deaths.

Since the federal government pays for about half of all vaccines, the additional cost would be partly borne by taxpayers. The committee voted 6 to 5 to support a booster, but for the recommendation to take effect, the Department of Health and Human Services would need to endorse it, which generally happens but not always.

Dr. Janet Englund, a committee member from Seattle Children’s Hospital, said that simply delaying the vaccine by three or four years would result in many teenagers failing to be vaccinated. A lower share of 15-year-olds are vaccinated compared with preteenagers, she noted. And with so many teenagers dropping out of high school, “by moving the age up, I very strongly fear we’re going to be missing at-risk youths,” she said.

But Dr. James Turner, a liaison representative to the committee from the American College Health Association, said that if the vaccines were truly so ineffective after five years, more meningitis cases would be popping up on college campuses. But a recent survey of 207 schools found just 11 cases, and fewer than half of those cases would have been prevented by vaccination, he said.

“If there is waning immunity, we’re not seeing any emerging disease yet,” he said. “So I don’t know that there’s a lot of urgency today in deciding on a booster.”

Meningococcal meningitis is a horrifying disease. It strikes so quickly that often only a day passes between the first signs of illness and the death of the child. Lori Buher, a mother from Mount Vernon, Wash., told the committee about how her 6-foot-4, 14-year-old son, Carl, was playing football one day and was being airlifted, near death, to Seattle Children’s Hospital the next. His heart stopped three times during the flight.

Carl survived but lost both legs below the knee, three fingers and the use of his knuckles. He suffered through 11 skin graft operations. She advocated for a booster shot, she said, because vaccination at age 11 would have saved Carl from his illness. His illness struck in 2003, before the present vaccines were approved.

“I can’t tell you what it would have meant if we’d been able to vaccinate him at 11,” Ms. Buher said.