- RETIREMENT ANNOUNCEMENT

- HOME PAGE

- "MYCHART" the new patient portal

- BELMONT MEDICAL ASSOCIATES

- MOUNT AUBURN HOSPITAL

- EMERGENCIES

- PRACTICE PHILOSOPHY

- MY RESUME

- TELEMEDICINE CONSULTATION

- CONTACT ME

- LAB RESULTS

- ePRESCRIPTIONS

- eREFERRALS

- RECORD RELEASE

- MEDICAL SCRIBE

- PHYSICIAN ASSISTANT (PA)

- Medicare Annual Wellness Visit

- Case management/Social work

- Quality Care Measures

- Emergency closing notice

- FEEDBACK

- Talking to your doctor

- Choosing..... and losing a doctor

- INDEX A - Z

- ALLERGIC REACTIONS

- Alternative Medicine

- Alzheimer's Disease

- Bladder Problems

- Blood disorders

- Cancer Concerns

- GENETIC TESTING FOR HEREDITARY CANCER

- Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

- Controversial Concerns

- CPR : Learn and save a life

- CRP : Inflammatory marker

- Diabetes Management

- Dizziness, Vertigo,Tinnitus and Hearing Loss

- EXERCISE

- FEMALE HEALTH

-

GASTROINTESTINAL topics

- Appendicitis

- BRAT diet

- Celiac Disease or Sprue

- Crohn's Disease

- Gastroenterologists for Colon Cancer Screening

- Colonoscopy PREP

- Constipation

- Gluten sensitivity, but not celiac disease

- Heartburn and GERD

- Hemorrhoids and Anal fissure

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- NASH : Non Alcoholic Steato Hepatitis

- FEET PROBLEMS

- HEART RELATED topics

-

INFECTIOUS DISEASES

- Antibiotic Resistance

- Cat bites >

- Clostridia difficile infection - the "antibiotic associated germ"

- CORONA VIRUS

- Dengue Fever and Chikungunya Fever

- Food borne illnesses

- Shingles Vaccine

- Hepatitis B

- Hepatitis C

- Herpes

- Influenza

- Helicobacter pylori - the "ulcer germ"

- HIV Screening

- Lyme and other tick borne diseases

- Measles

- Meningitis

- MRSA (Staph infection)

- Norovirus

- Sexually Transmitted Diseases

- Shingles (Herpes Zoster)

- Sinusitis

- West Nile Virus

- Whooping Cough (Pertussis)

- Zika virus and pregnancy

- INSURANCE related topics

- KIDNEY STONES

- LEG CRAMPS

- LIBRARY for patients

- LIFE DECISIONS

- MALE HEALTH

- Medication/Drug side effects

- MEDICAL MARIJUANA

- MENTAL HEALTH

- Miscellaneous Articles

-

NUTRITION - EXERCISE - WEIGHT

- Cholesterol : New guidelines for treatment

- Advice to lower your cholesterol

- Cholesterol : Control

- Cholesterol : Raising your HDL Level

- Exercise

- Food : Making Smart Choices

- Food : Making Poor Choices

- Food : Grape Fruit and Drug Interaction

- Food : Vitamins, Minerals and Supplements

- Omega 3 fatty acids

- Vitamin B12 deficiency

- Vitamin D

- Weight Loss

- ORTHOPEDICS

- PAIN

- PATIENTS' RIGHTS

- SKIN

- SLEEP

- SMOKING

- STROKE

- THYROID

- SUBSTANCE ABUSE

- Travel and Vaccination

- TREMOR

- Warfarin Anticoagulation

- OTHER STUFF FOLLOWS

- Fact or Opinion?

- Hippocratic Oath

- FREE ADVICE.......for what its worth!

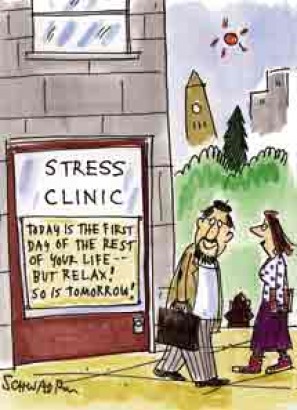

- LAUGHTER.....is the best medicine

- Physicians Pet Peeves

- PHOTO ALBUM - its not all work!

- Cape Town, South Africa

- Tribute page

- The 100 Club

- Free Wi-Fi

Stress Relief Suggestions

- Simplify your life. Cut out some activities or delegate tasks. Use the extra time to relax through such exercises as controlling your breathing, clearing your mind and relaxing your muscles.

- Slow down. When multi-tasking gets out of hand, stop and refocus on mindfulness

- Have fun: Isn't family fun and togetherness what the holidays are all about? Focus on fun and relaxation, rather than on creating the perfect table or moment, and you will see your holiday stress melt away.

- Have realistic expectations: If each day has a realistic to-do list, there will be success at the end of the day, rather than failure.

- Enjoy some me time: Don't become so involved with holiday preparations that you forget to take care of yourself. Falling into bed exhausted each night is not rest. Rejuvenate by reading a book, enjoying a cup of tea, getting a spa treatment or simply watching a funny television show in the middle of the day. Running yourself ragged completely diminishes the joy of the holidays and turns celebration into hard labor.

- View negative situations as positive and a chance to improve your life. Use humor to reduce or relieve tension.

- Take several 30-second breaks to look out the window or stretch.

- Exercise. It relieves tension and provides a "time out" from stressful situations. Try yoga for relaxation and to improve mobility.

- Go to bed earlier. More sleep makes you stronger and more able to handle day-to-day life.

- Eat a good breakfast and lunch.

- Reduce or eliminate caffeine consumption. Caffeine is a stimulant.

- Get a massage.

- Keep a stress journal. Track what sets you off and learn to prioritize. Do what is most important first. Don't try to solve or deal with every problem. Take care of one problem at a time. It is far easier to manage.

- Enjoy yourself. Read a good book or see an uplifting movie. Don't watch a 24 hour news channel. It constantly reinforces the negative or upsetting stories. Perhaps not reading the newspaper for a few days would also be helpful. The world will survive without you for a while.

- Turn off your Blackberry in the evening after work.

- Don't take work problems home or home problems to work.

- Take a hot bath.

- Call a friend and strengthen or establish a support network. Make the most of friends and family.

- Set aside personal time. Limit time spent with negative people.

- Hug your family

- Do volunteer work or start a hobby.

- Pray or meditate.

- Practice relaxation techniques, such as deep breathing or self-hypnosis.

- Take a vacation. Take a day or longer to rejuvenate yourself.

- Keep a positive attitude.

- Accept that there are events that you cannot control.

- Be assertive instead of aggressive. "Assert" your feelings, opinions, or beliefs instead of becoming angry, defensive, or passive. This does not have to be argumentative.

- Learn and practice relaxation techniques.

- Exercise regularly, but not obsessively. Your body can fight stress better when it is fit.

- Eat healthy, well-balanced meals.

- Get enough rest and sleep. Your body needs time to recover from stressful events.

- Don't rely on alcohol or drugs to reduce stress.

- Seek out social support.

- Learn to manage your time more effectively.

- Cultivating calm is like investing in a good long-term relationship - it feels good from the beginning, but as you develop it gets better, sweeter and more rewarding.

- Learn to focus on what really matters rather than the task at hand. Eventually it will change the way you behave in traffic jams, interact with strangers and care for the people you love.

Self-Help for Skeptics

Train Your Brain to Be Positive, and Feel Happier Every Day:

It Only Sounds Corny

Elizabeth Bernstein : WSJ : August 27, 2012

Donna Talarico sat at her computer one morning, stared at the screen and realized she had forgotten—again!—her password.

She was having financial difficulties at the time, and was reading self-help books to boost her mood and self-confidence. The books talked about the power of positive affirmation—which gave her an idea: She changed her various passwords to private messages to herself, like "imawe$some1" or "dogoodworktoday."

"It's something so simple," says the 34-year-old marketing manager at Elizabethtown College, in Pennsylvania. "It just reinforces that you're a good person. You can do a good job at whatever you are trying to talk yourself into."

In times of stress, even people with close social networks can feel utterly alone. We're often advised to "buck up," "talk to someone" (who is often paid to listen) or take a pill. Wouldn't it also make sense to learn ways to comfort and be supportive of ourselves?

Think of it as becoming our own best friend, or our own personal coach, ready with the kind of encouragement and tough love that works best for us. After all, who else knows us better than ourselves? If that sounds crazy, bear in mind it sure beats turning to chocolate, alcohol or your Pekingese for support.

Experts say that to feel better you need to treat yourself kindly—this is called "self-compassion"—and focus on the positive, by being optimistic. Research shows self-compassionate people cope better with everything from a major relationship breakup to the loss of their car keys. They don't compound their misery by beating themselves up over every unfortunate accident or mistake. Car broke down? Sure, it's a drag, but it doesn't make you an idiot.

"They are treating themselves like a kind friend," says Mark Leary, professor of psychology and neuroscience at Duke University. "When bad things happen to a friend, you wouldn't yell at him."

Self-compassion helps people overcome life's little, and not-so-little, stressors, such as public speaking. In another study, Dr. Leary asked people to stand in front of a videocamera and make up a story starting with the phrase, "Once there was a little bear…" Then he asked them to critique their performance, captured on videotape.

People whom the study had identified as being high in self-compassion admitted they looked silly, recognized the task wasn't easy and joked about it. People low in self-compassion gave harsh self-criticism.

Experts say you can learn self-compassion in real time. You can train your brain to focus on the positive—even if you're wired to see the glass as half empty. A person's perspective, or outlook, is influenced by factors including genetic makeup (is he prone to depression?), experiences (what happened to him?) and "cognitive bias" (how does he interpret his experiences?). We can't change our genes or our experiences, but experts say we can change the way we interpret what has happened in the past.

Everyone has an optimistic and a pessimistic circuit in their brain, says Elaine Fox, visiting research professor at the University of Oxford, England, and director of the Affective Neuroscience Laboratory in the Department of Psychology at the University of Essex. Fear, rooted in the amygdala, helps us identify and respond to threats and is at the root of pessimism. Optimism, in contrast, is rooted in the nucleus accumbens, the brain's pleasure center, which responds to food, sex and other healthy, good things in life.

"The most resilient people experience a wide range of emotions, both negative and positive," says Dr. Fox, author of "Rainy Brain, Sunny Brain." To enjoy life and feel good, people need roughly four positive emotions to counteract the effect of one negative emotion, she says. People who experience life as drudgery had two or even one positive emotion for every negative one, Dr. Fox has found.

It's possible to change your cognitive bias by training the brain to focus more on the positive than on the negative. In the lab, Dr. Fox showed subjects pairs of images, one negative (the aftermath of a bomb blast, say) and one either positive (a cute child) or neutral (an office). Participants were asked to point out, as quickly as possible, a small target that appeared immediately after each positive or neutral image—subliminally requiring them to pay less attention to the negative images, which had no target.

Always There For You

Here are ways to be your own best friend in stressful times.

Want to try this at home? Write down, in a journal, the positive and negative things that happen to you each day, whether running into an old friend or missing your bus. Try for four positives for each negative. You'll be training your brain to look for the good even as you acknowledge the bad, Dr. Fox says.

When I asked, I was pleasantly surprised by the number and variety of ways people said they treat themselves with compassion, care and kindness. Anittah Patrick, a 35-year-old online marketing consultant in Philadelphia, celebrated her emergence from a long depression by making herself a valentine. She covered an old picture frame with lace and corks from special bottles of wine, and drew a big heart inside. Using old computer keys, she spelled out the message "Welc*me Back." Then she put it on her dressing table, where she sees it every morning. "It's a nice reminder that I'll get through whatever challenge I'm facing," she says.

If Kris Wittenberg, a 45-year-old entrepreneur from Vail, Colo., starts to feel bad, she tells herself "Stop," and jots down something she is grateful for. She writes down at least five things at the end of each day. "You start to see how many negative thoughts you have," she says.

Kevin Kilpatrick, 55, a college professor and children's author in San Diego, talks to himself—silently, unless he is in the car—going over everything positive he has accomplished recently. "It helps me to hear it out loud, especially from the voice that's usually screaming at me to do better, work harder and whatever else it wants to berate me about," he says.

Adam Urbanski, 42, who owns a marketing firm and lives in Irvine, Calif., keeps a binder labeled "My Raving Fans" in his office. Filling it are more than 100 cards and letters from clients and business contacts thanking him for his help. "All it takes is reading a couple of them to realize that I do make a difference," Mr. Urbanski says.

He has something he calls his "1-800-DE-FUNK line." It's not a real number, but a strategy he uses when he is upset. He calls a friend, vents for 60 seconds, then asks her about her problems. "It's amazing how five minutes of working on someone else's problems makes my own disappear," he says. Sometimes, as a reality check, he asks himself, "What Would John Nash Think?" in honor of the mathematician, Nobel laureate and subject of the film "A Beautiful Mind," who suffered from paranoid schizophrenia.

Are things really as dire as he thinks? Is he overreacting? "It always turns out that whatever keeps me down isn't really as bad as I thought," Mr. Urbanski says.

Train Your Brain to Be Positive, and Feel Happier Every Day:

It Only Sounds Corny

Elizabeth Bernstein : WSJ : August 27, 2012

Donna Talarico sat at her computer one morning, stared at the screen and realized she had forgotten—again!—her password.

She was having financial difficulties at the time, and was reading self-help books to boost her mood and self-confidence. The books talked about the power of positive affirmation—which gave her an idea: She changed her various passwords to private messages to herself, like "imawe$some1" or "dogoodworktoday."

"It's something so simple," says the 34-year-old marketing manager at Elizabethtown College, in Pennsylvania. "It just reinforces that you're a good person. You can do a good job at whatever you are trying to talk yourself into."

In times of stress, even people with close social networks can feel utterly alone. We're often advised to "buck up," "talk to someone" (who is often paid to listen) or take a pill. Wouldn't it also make sense to learn ways to comfort and be supportive of ourselves?

Think of it as becoming our own best friend, or our own personal coach, ready with the kind of encouragement and tough love that works best for us. After all, who else knows us better than ourselves? If that sounds crazy, bear in mind it sure beats turning to chocolate, alcohol or your Pekingese for support.

Experts say that to feel better you need to treat yourself kindly—this is called "self-compassion"—and focus on the positive, by being optimistic. Research shows self-compassionate people cope better with everything from a major relationship breakup to the loss of their car keys. They don't compound their misery by beating themselves up over every unfortunate accident or mistake. Car broke down? Sure, it's a drag, but it doesn't make you an idiot.

"They are treating themselves like a kind friend," says Mark Leary, professor of psychology and neuroscience at Duke University. "When bad things happen to a friend, you wouldn't yell at him."

Self-compassion helps people overcome life's little, and not-so-little, stressors, such as public speaking. In another study, Dr. Leary asked people to stand in front of a videocamera and make up a story starting with the phrase, "Once there was a little bear…" Then he asked them to critique their performance, captured on videotape.

People whom the study had identified as being high in self-compassion admitted they looked silly, recognized the task wasn't easy and joked about it. People low in self-compassion gave harsh self-criticism.

Experts say you can learn self-compassion in real time. You can train your brain to focus on the positive—even if you're wired to see the glass as half empty. A person's perspective, or outlook, is influenced by factors including genetic makeup (is he prone to depression?), experiences (what happened to him?) and "cognitive bias" (how does he interpret his experiences?). We can't change our genes or our experiences, but experts say we can change the way we interpret what has happened in the past.

Everyone has an optimistic and a pessimistic circuit in their brain, says Elaine Fox, visiting research professor at the University of Oxford, England, and director of the Affective Neuroscience Laboratory in the Department of Psychology at the University of Essex. Fear, rooted in the amygdala, helps us identify and respond to threats and is at the root of pessimism. Optimism, in contrast, is rooted in the nucleus accumbens, the brain's pleasure center, which responds to food, sex and other healthy, good things in life.

"The most resilient people experience a wide range of emotions, both negative and positive," says Dr. Fox, author of "Rainy Brain, Sunny Brain." To enjoy life and feel good, people need roughly four positive emotions to counteract the effect of one negative emotion, she says. People who experience life as drudgery had two or even one positive emotion for every negative one, Dr. Fox has found.

It's possible to change your cognitive bias by training the brain to focus more on the positive than on the negative. In the lab, Dr. Fox showed subjects pairs of images, one negative (the aftermath of a bomb blast, say) and one either positive (a cute child) or neutral (an office). Participants were asked to point out, as quickly as possible, a small target that appeared immediately after each positive or neutral image—subliminally requiring them to pay less attention to the negative images, which had no target.

Always There For You

Here are ways to be your own best friend in stressful times.

- Instead of "pushing through" a bad day, look for ways to actively improve it. Take a small break. Get an ice-cream cone. Invite a friend out to dinner.

- Resist the urge to make your problems worse. "Ask yourself, How much of my distress is the real problem, and how much is stuff I am heaping on myself unnecessarily?" says Mark Leary, professor of psychology and neuroscience at Duke University.

- Boost your daily ratio of positive-to-negative emotions, says Elaine Fox, a cognitive psychologist. What do you enjoy doing? Seeing your best buddy, watching a funny movie, walking in the park? Make a list and do one a day.

- Then list things you really don't enjoy. Are there people who bring you down? Hobbies that no longer interest you? Errands you can delegate? Some of this stuff can be avoided.

- If you don't feel happy, fake it. You wouldn't constantly burden a friend with your bad mood, so don't burden yourself. Try holding a pencil horizontally in your mouth. "This activates the same muscles that create a smile, and our brain interprets this as happiness," Dr. Fox says.

Want to try this at home? Write down, in a journal, the positive and negative things that happen to you each day, whether running into an old friend or missing your bus. Try for four positives for each negative. You'll be training your brain to look for the good even as you acknowledge the bad, Dr. Fox says.

When I asked, I was pleasantly surprised by the number and variety of ways people said they treat themselves with compassion, care and kindness. Anittah Patrick, a 35-year-old online marketing consultant in Philadelphia, celebrated her emergence from a long depression by making herself a valentine. She covered an old picture frame with lace and corks from special bottles of wine, and drew a big heart inside. Using old computer keys, she spelled out the message "Welc*me Back." Then she put it on her dressing table, where she sees it every morning. "It's a nice reminder that I'll get through whatever challenge I'm facing," she says.

If Kris Wittenberg, a 45-year-old entrepreneur from Vail, Colo., starts to feel bad, she tells herself "Stop," and jots down something she is grateful for. She writes down at least five things at the end of each day. "You start to see how many negative thoughts you have," she says.

Kevin Kilpatrick, 55, a college professor and children's author in San Diego, talks to himself—silently, unless he is in the car—going over everything positive he has accomplished recently. "It helps me to hear it out loud, especially from the voice that's usually screaming at me to do better, work harder and whatever else it wants to berate me about," he says.

Adam Urbanski, 42, who owns a marketing firm and lives in Irvine, Calif., keeps a binder labeled "My Raving Fans" in his office. Filling it are more than 100 cards and letters from clients and business contacts thanking him for his help. "All it takes is reading a couple of them to realize that I do make a difference," Mr. Urbanski says.

He has something he calls his "1-800-DE-FUNK line." It's not a real number, but a strategy he uses when he is upset. He calls a friend, vents for 60 seconds, then asks her about her problems. "It's amazing how five minutes of working on someone else's problems makes my own disappear," he says. Sometimes, as a reality check, he asks himself, "What Would John Nash Think?" in honor of the mathematician, Nobel laureate and subject of the film "A Beautiful Mind," who suffered from paranoid schizophrenia.

Are things really as dire as he thinks? Is he overreacting? "It always turns out that whatever keeps me down isn't really as bad as I thought," Mr. Urbanski says.

When Daily Stress Gets in the Way of Life

By Jane E. Brody : NY Times : December 10, 2012

I was about to give an hourlong talk to hundreds of people when one of the organizers of the event asked, "Do you get nervous when you give speeches?" My response: Who, me? No. Of course not.

But this was a half-truth. I am a bit of a worrier, and one thing that makes me anxious is getting ready for these events: fretting over whether I've prepared the right talk, packed the right clothes or forgotten anything important, like my glasses.

Anxiety is a fact of life. I've yet to meet anyone, no matter how upbeat, who has escaped anxious moments, days, even weeks. Recently I succumbed when, rushed for time just before a Thanksgiving trip, I was told the tires on my car were too worn to be driven on safely and had to be replaced.

"But I have no time to do this now," I whined.

"Do you have time for an accident?" my car-savvy neighbor asked.

So, with a pounding pulse and no idea how I'd make up the lost time, I went off to get new tires. I left the car at the shop and managed to calm down during the walk home, which helped me get back to the work I needed to finish before the trip.

It seems like such a small thing now. But everyday stresses add up, according to Tamar E. Chansky, a psychologist in Plymouth Meeting, Penn., who treats people with anxiety disorders.

You'll be much better able to deal with a serious, unexpected challenge if you lower your daily stress levels, she said. When worry is a constant, "it takes less to tip the scales to make you feel agitated or plagued by physical symptoms, even in minor situations," she wrote in her very practical book, "Freeing Yourself From Anxiety."

When Calamities Are Real

Of course, there are often good reasons for anxiety. Certainly, people who lost their homes and life's treasures - and sometimes loved ones - in Hurricane Sandy can hardly be faulted for worrying about their futures.

But for some people, anxiety is a way of life, chronic and life-crippling, constantly leaving them awash in fears that prevent them from making moves that could enrich their lives.

In an interview, Dr. Chansky said that when real calamities occur, "you will be in much better shape to cope with them if you don't entertain extraneous catastrophes."

By "extraneous," she means the many stresses that pile up in the course of daily living that don't really deserve so much of our emotional capital - the worrying and fretting we spend on things that won't change or simply don't matter much.

"If you worry about everything, it will get in the way of what you really need to address," she explained. "The best decisions are not made when your mind is spinning out of control, racing ahead with predictions about how things are never going to get any better. Precious energy is wasted when you're always thinking about the worst-case scenarios."

When faced with serious challenges, it helps to narrow them down to specific things you can do now. To my mind, Dr. Chansky's most valuable suggestion for emerging from paralyzing anxiety when faced with a monumental task is to "stay in the present - it doesn't help to be in the future.

"Take some small step today, and value each step you take. You never know which step will make a difference. This is much better than not trying to do anything."

Dr. Chansky told me, "If you're worrying about your work all the time, you won't get your work done." She suggested instead that people "compartmentalize." Those prone to worry should set aside a little time each day simply to fret, she said - and then put aside anxieties and spend the rest of the time getting things done. This advice could not have come at a better time for me, as I faced holiday chores, two trips in December, and five columns to write before leaving mid-month. Rather than focusing on what seemed like an impossible challenge, I took on one task at a time. Somehow it all got done.

Possible Thinking

Many worriers think the solution is positive thinking. Dr. Chansky recommends something else: think "possible."

"When we are stuck with negative thinking, we feel out of options, so to exit out of that we need to be reminded of all the options we do have," she writes in her book.

If this is not something you can do easily on your own, consult others for suggestions. During my morning walk with friends, we often discuss problems, and inevitably someone comes up with a practical solution. But even if none of their suggestions work, at least they narrow down possible courses of action and make the problem seem less forbidding. "If other people are not caught in the spin that you're in, they may have ideas for you that you wouldn't think of," Dr. Chansky said. "We often do this about small things, but when something big is going on, we hesitate to ask for advice. Yet that's when we need it most."

Dr. Chansky calls this "a community cleanup effort," and it can bring more than advice. During an especially challenging time, like dealing with a spouse's serious illness or loss of one's home, friends and family members can help with practical matters like shopping for groceries, providing meals, cleaning out the refrigerator or paying bills.

"People want to help others in need - it's how the world goes around," she said. Witness the many thousands of volunteers, including students from other states on their Thanksgiving break, who prepared food and delivered clothing and equipment to the victims of Hurricane Sandy. Even the smallest favor can help buffer stress and enable people to focus productively on what they can do to improve their situation.

Another of Dr. Chansky's invaluable tips is to "let go of the rope." When feeling pressured to figure out how to fix things now, "walk away for a few minutes, but promise to come back." As with a computer that suddenly misbehaves, Dr. Chansky suggests that you "unplug and refresh," perhaps by "taking a breathing break," inhaling and exhaling calmly and intentionally.

"The more you practice calm breathing, the more it will be there for you when you need it," she wrote.

She also suggests taking a break to do something physical: "Movement shifts the moment." Take a walk or bike ride, call a friend, look through a photo album, or do some small cleaning task like clearing off your night table.

When you have a clear head and are feeling less overwhelmed, you'll be better able to figure out the next step.

This is the first of two columns about anxiety.