- RETIREMENT ANNOUNCEMENT

- HOME PAGE

- "MYCHART" the new patient portal

- BELMONT MEDICAL ASSOCIATES

- MOUNT AUBURN HOSPITAL

- EMERGENCIES

- PRACTICE PHILOSOPHY

- MY RESUME

- TELEMEDICINE CONSULTATION

- CONTACT ME

- LAB RESULTS

- ePRESCRIPTIONS

- eREFERRALS

- RECORD RELEASE

- MEDICAL SCRIBE

- PHYSICIAN ASSISTANT (PA)

- Medicare Annual Wellness Visit

- Case management/Social work

- Quality Care Measures

- Emergency closing notice

- FEEDBACK

- Talking to your doctor

- Choosing..... and losing a doctor

- INDEX A - Z

- ALLERGIC REACTIONS

- Alternative Medicine

- Alzheimer's Disease

- Bladder Problems

- Blood disorders

- Cancer Concerns

- GENETIC TESTING FOR HEREDITARY CANCER

- Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

- Controversial Concerns

- CPR : Learn and save a life

- CRP : Inflammatory marker

- Diabetes Management

- Dizziness, Vertigo,Tinnitus and Hearing Loss

- EXERCISE

- FEMALE HEALTH

-

GASTROINTESTINAL topics

- Appendicitis

- BRAT diet

- Celiac Disease or Sprue

- Crohn's Disease

- Gastroenterologists for Colon Cancer Screening

- Colonoscopy PREP

- Constipation

- Gluten sensitivity, but not celiac disease

- Heartburn and GERD

- Hemorrhoids and Anal fissure

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- NASH : Non Alcoholic Steato Hepatitis

- FEET PROBLEMS

- HEART RELATED topics

-

INFECTIOUS DISEASES

- Antibiotic Resistance

- Cat bites >

- Clostridia difficile infection - the "antibiotic associated germ"

- CORONA VIRUS

- Dengue Fever and Chikungunya Fever

- Food borne illnesses

- Shingles Vaccine

- Hepatitis B

- Hepatitis C

- Herpes

- Influenza

- Helicobacter pylori - the "ulcer germ"

- HIV Screening

- Lyme and other tick borne diseases

- Measles

- Meningitis

- MRSA (Staph infection)

- Norovirus

- Sexually Transmitted Diseases

- Shingles (Herpes Zoster)

- Sinusitis

- West Nile Virus

- Whooping Cough (Pertussis)

- Zika virus and pregnancy

- INSURANCE related topics

- KIDNEY STONES

- LEG CRAMPS

- LIBRARY for patients

- LIFE DECISIONS

- MALE HEALTH

- Medication/Drug side effects

- MEDICAL MARIJUANA

- MENTAL HEALTH

- Miscellaneous Articles

-

NUTRITION - EXERCISE - WEIGHT

- Cholesterol : New guidelines for treatment

- Advice to lower your cholesterol

- Cholesterol : Control

- Cholesterol : Raising your HDL Level

- Exercise

- Food : Making Smart Choices

- Food : Making Poor Choices

- Food : Grape Fruit and Drug Interaction

- Food : Vitamins, Minerals and Supplements

- Omega 3 fatty acids

- Vitamin B12 deficiency

- Vitamin D

- Weight Loss

- ORTHOPEDICS

- PAIN

- PATIENTS' RIGHTS

- SKIN

- SLEEP

- SMOKING

- STROKE

- THYROID

- SUBSTANCE ABUSE

- Travel and Vaccination

- TREMOR

- Warfarin Anticoagulation

- OTHER STUFF FOLLOWS

- Fact or Opinion?

- Hippocratic Oath

- FREE ADVICE.......for what its worth!

- LAUGHTER.....is the best medicine

- Physicians Pet Peeves

- PHOTO ALBUM - its not all work!

- Cape Town, South Africa

- Tribute page

- The 100 Club

- Free Wi-Fi

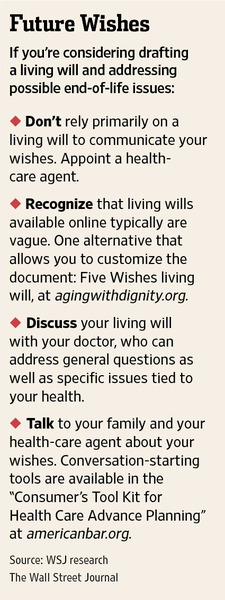

A New Look at Living Wills

These critical documents about your preferences for end-of-life care don't always work as planned. More flexibility might be the answer.

Laura Johannes : WSJ : June 8, 2012

My father was in a coma, hooked up to a ventilator, and I had to make a tough call.

His living will expressed his desires for a few black-and-white situations: He didn't want to be kept alive if he was terminally ill, or in an irreversible vegetative state. But the situation I faced wasn't so simple. The neurologist said he would wake up from the coma, but there was a good chance he would have severe brain damage. How much of a chance? The doctors couldn't say.

Doctors and nurses say my heart-wrenching experience is typical of the complexity of real-life bedside decisions. An estimated 25% to 30% of Americans have filled out living wills, documents that spell out wishes for medical treatment. But ethicists say the typically simplistic documents aren't the solution many hoped they would be. Life-prolonging medical technology has far outstripped doctors' ability to predict outcomes. The hardest choices center on when quality of life will be so diminished that death is preferable.

As such, some health organizations are trying to improve living wills, allowing for more flexibility and nuance. Some ethicists, meanwhile, are de-emphasizing living wills altogether and focusing on appointing a trusted family member or friend as your health-care agent.

"Most of us have come to the conclusion that the way to get over the vagueness is to get someone to speak for you," says Robert M. Veatch, a professor of medical ethics at Georgetown University's Kennedy Institute of Ethics in Washington, D.C.

Living wills were created in the 1960s and gained national attention in the 1970s when a young woman, Karen Ann Quinlan, following alcohol and drug use at a party, was left in a vegetative state, raising alarms about medical technology keeping people alive in hopeless circumstances.

"We had a naive view that if you had a document, that would solve the problem," says Daniel Callahan, co-founder and president emeritus of the Hastings Center, a Garrison, N.Y., nonprofit that was an early champion of living wills. "In practice," he says, "all sorts of problems arise" that aren't spelled out in the documents.

When Paul Shalline, an active 86-year-old who regularly bested his grandchildren at ping pong, was unable to communicate after a severe stroke in March, treatment decisions fell to his daughter, Robin. Ms. Shalline, a 57-year-old teacher from Monkton, Vt., says her father had a living will but had never talked to her about his wishes. "There is so much gray area," she says. "You'd hope the living will would spell it all out, but it doesn't."

His living will called for withdrawing life support if there was no reasonable expectation of regaining a "meaningful quality of life" but didn't describe what that meant, she says. Ms. Shalline, when told by doctors that her father could be blind in one eye, unable to feed himself and might never walk again, made the decision to withdraw the ventilator based on "what I knew about his life." Mr. Shalline, who loved Wiffle ball and had recently helped build a staircase, was "proud of his 'physicalness,' " she says. He died March 18. It is hard enough, under the best of circumstances, to know what your family member would want in a particular situation. But add to that the fact that even top doctors can't predict outcomes very well.

Lee H. Schwamm, vice chairman of the neurology department at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, where Mr. Shalline was treated, says that even when he thinks he can predict a patient's outcome after a stroke, he is wrong 15% to 20% of the time on major outcome measures, such as whether a patient will be able to walk again. "I've never seen a living will—and I've seen a lot—that speaks to this question of diagnostic uncertainty," says Dr. Schwamm.

Living Documents

You can get a living will from a lawyer or download it from the Internet. Many focus on permanent comas and clearly hopeless conditions. Florida's statute-suggested living will, for example, directs life-prolonging treatments to be stopped if there is "no reasonable medical probability" of recovery from a terminal condition or persistent vegetative state. Florida, like most states, allows you to write your own living will; a few states, such as New Hampshire, specify that living wills must use a state-approved form. (A bill now being considered in New Hampshire would make the state form optional.)

A number of efforts have been made to improve on the standard-style living will. A document available online from Lifecare Directives LLC, Las Vegas, for example, spells out several levels of cognitive decline from coma to mental "confusion" that require 24-hour supervision, and asks if you would want life support if your brain failed that much. The document also gives you an option to say whether you want doctors to be "positively certain," "certain to a high degree" or "reasonably certain" that you will never recover before pulling the plug.

A simpler but also innovative approach is the popular Five Wishes living will. Five Wishes is written at a sixth- to seventh-grade level, says Paul Malley, president of Aging with Dignity, a nonprofit that distributes the document. Despite its simplicity, the Five Wishes living will addresses issues many others don't—for example, asking if you want pain medication to relieve suffering even if it makes you sleepy. It also has a blank space where people can specify a state in which they wouldn't want to be kept alive.

"Some people have a phrase that pops out in their mind: 'If I'm in the same condition as Aunt Mary,' " Mr. Malley says. Originally written in 1997, the Five Wishes will has been available online in an interactive format since last year.

Open to Interpretation

The problem with living wills is that most people can't articulate what they want, says ethicist Angela Fagerlin, co-director of the University of Michigan-affiliated Center for Bioethics and Social Sciences in Medicine in Ann Arbor. And even if they can, family members often don't properly interpret those wishes.

In a 400-patient study published in 2001, Dr. Fagerlin and colleagues found that family members who were presented with nine hypothetical scenarios correctly predicted patient wishes about 70% of the time, whether or not the patient had filled out a living will.

Can you forgo such documents completely? Mr. Callahan, who championed living wills in their early days, says he doesn't have one, preferring instead to give decision-making power to his wife, to whom he has said simply, "When in doubt, don't treat."

A health-care agent—a trusted family member, for instance—could supplant the need for a living will. Under the legal doctrine of "substituted judgment," health-care agents must try to make the decision you would if you could, says Alan Meisel, the director of the Center for Bioethics and Health Law at the University of Pittsburgh. Anything—a phone conversation, a list of instructions or a formal living will—can be used as evidence of your wishes, he adds.

As for my father, we postponed the decision, and he woke up, sharp as a tack, able to make his own decisions.

These critical documents about your preferences for end-of-life care don't always work as planned. More flexibility might be the answer.

Laura Johannes : WSJ : June 8, 2012

My father was in a coma, hooked up to a ventilator, and I had to make a tough call.

His living will expressed his desires for a few black-and-white situations: He didn't want to be kept alive if he was terminally ill, or in an irreversible vegetative state. But the situation I faced wasn't so simple. The neurologist said he would wake up from the coma, but there was a good chance he would have severe brain damage. How much of a chance? The doctors couldn't say.

Doctors and nurses say my heart-wrenching experience is typical of the complexity of real-life bedside decisions. An estimated 25% to 30% of Americans have filled out living wills, documents that spell out wishes for medical treatment. But ethicists say the typically simplistic documents aren't the solution many hoped they would be. Life-prolonging medical technology has far outstripped doctors' ability to predict outcomes. The hardest choices center on when quality of life will be so diminished that death is preferable.

As such, some health organizations are trying to improve living wills, allowing for more flexibility and nuance. Some ethicists, meanwhile, are de-emphasizing living wills altogether and focusing on appointing a trusted family member or friend as your health-care agent.

"Most of us have come to the conclusion that the way to get over the vagueness is to get someone to speak for you," says Robert M. Veatch, a professor of medical ethics at Georgetown University's Kennedy Institute of Ethics in Washington, D.C.

Living wills were created in the 1960s and gained national attention in the 1970s when a young woman, Karen Ann Quinlan, following alcohol and drug use at a party, was left in a vegetative state, raising alarms about medical technology keeping people alive in hopeless circumstances.

"We had a naive view that if you had a document, that would solve the problem," says Daniel Callahan, co-founder and president emeritus of the Hastings Center, a Garrison, N.Y., nonprofit that was an early champion of living wills. "In practice," he says, "all sorts of problems arise" that aren't spelled out in the documents.

When Paul Shalline, an active 86-year-old who regularly bested his grandchildren at ping pong, was unable to communicate after a severe stroke in March, treatment decisions fell to his daughter, Robin. Ms. Shalline, a 57-year-old teacher from Monkton, Vt., says her father had a living will but had never talked to her about his wishes. "There is so much gray area," she says. "You'd hope the living will would spell it all out, but it doesn't."

His living will called for withdrawing life support if there was no reasonable expectation of regaining a "meaningful quality of life" but didn't describe what that meant, she says. Ms. Shalline, when told by doctors that her father could be blind in one eye, unable to feed himself and might never walk again, made the decision to withdraw the ventilator based on "what I knew about his life." Mr. Shalline, who loved Wiffle ball and had recently helped build a staircase, was "proud of his 'physicalness,' " she says. He died March 18. It is hard enough, under the best of circumstances, to know what your family member would want in a particular situation. But add to that the fact that even top doctors can't predict outcomes very well.

Lee H. Schwamm, vice chairman of the neurology department at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, where Mr. Shalline was treated, says that even when he thinks he can predict a patient's outcome after a stroke, he is wrong 15% to 20% of the time on major outcome measures, such as whether a patient will be able to walk again. "I've never seen a living will—and I've seen a lot—that speaks to this question of diagnostic uncertainty," says Dr. Schwamm.

Living Documents

You can get a living will from a lawyer or download it from the Internet. Many focus on permanent comas and clearly hopeless conditions. Florida's statute-suggested living will, for example, directs life-prolonging treatments to be stopped if there is "no reasonable medical probability" of recovery from a terminal condition or persistent vegetative state. Florida, like most states, allows you to write your own living will; a few states, such as New Hampshire, specify that living wills must use a state-approved form. (A bill now being considered in New Hampshire would make the state form optional.)

A number of efforts have been made to improve on the standard-style living will. A document available online from Lifecare Directives LLC, Las Vegas, for example, spells out several levels of cognitive decline from coma to mental "confusion" that require 24-hour supervision, and asks if you would want life support if your brain failed that much. The document also gives you an option to say whether you want doctors to be "positively certain," "certain to a high degree" or "reasonably certain" that you will never recover before pulling the plug.

A simpler but also innovative approach is the popular Five Wishes living will. Five Wishes is written at a sixth- to seventh-grade level, says Paul Malley, president of Aging with Dignity, a nonprofit that distributes the document. Despite its simplicity, the Five Wishes living will addresses issues many others don't—for example, asking if you want pain medication to relieve suffering even if it makes you sleepy. It also has a blank space where people can specify a state in which they wouldn't want to be kept alive.

"Some people have a phrase that pops out in their mind: 'If I'm in the same condition as Aunt Mary,' " Mr. Malley says. Originally written in 1997, the Five Wishes will has been available online in an interactive format since last year.

Open to Interpretation

The problem with living wills is that most people can't articulate what they want, says ethicist Angela Fagerlin, co-director of the University of Michigan-affiliated Center for Bioethics and Social Sciences in Medicine in Ann Arbor. And even if they can, family members often don't properly interpret those wishes.

In a 400-patient study published in 2001, Dr. Fagerlin and colleagues found that family members who were presented with nine hypothetical scenarios correctly predicted patient wishes about 70% of the time, whether or not the patient had filled out a living will.

Can you forgo such documents completely? Mr. Callahan, who championed living wills in their early days, says he doesn't have one, preferring instead to give decision-making power to his wife, to whom he has said simply, "When in doubt, don't treat."

A health-care agent—a trusted family member, for instance—could supplant the need for a living will. Under the legal doctrine of "substituted judgment," health-care agents must try to make the decision you would if you could, says Alan Meisel, the director of the Center for Bioethics and Health Law at the University of Pittsburgh. Anything—a phone conversation, a list of instructions or a formal living will—can be used as evidence of your wishes, he adds.

As for my father, we postponed the decision, and he woke up, sharp as a tack, able to make his own decisions.

Living wills, other end of life decisions

and why a Health Care Proxy is a better idea in Massachusetts

End of Life Decisions

By Melinda Beck : WSJ Article : August 18, 2009

Forget about the health-reform debate for the moment. Should you have a living will specifying the kind of care you'd want at the end of life if you couldn't speak for yourself?

Doctors, lawmakers and ethicists have been urging Americans to fill out advance directives, as they are called, for decades. Yet less than a third of American adults, and less than half of nursing-home patients, have done so. Many people don't understand the options or the consequences, or they are baffled by the legalities, according to a report prepared for Congress last year by Rand Corp., and doctors and patients alike are reluctant to broach the subject of death.

"Everybody knows they're going to die, but it's really scary to think about how," says Audrey Seeley, a registered nurse in the stroke unit at Inova Hospital in Falls Church, Va., who sees many patients who are suddenly seriously incapacitated. "A lot of people say, 'If I get to that point, I don't care what happens to me.' But your family does."

Connie Paeglow works with elderly people and their families to discuss end-of-life preferences, including deciding on life-support care using the Five Wishes advanced-directives form.

Indeed, advance directives are as much for the living as for the dying. Without specific instructions, family members may have to decide whether you would want to be kept alive artificially, what level of disability you'd be willing to live with and how to let you die if you had no hope of recovery.

If family members aren't available, doctors are generally empowered to discontinue medical care they deem futile. But that rarely happens, largely for legal reasons, says Neil Wenger, director, UCLA Health System Ethics Center, and one of the authors of the Rand report. More often, he says, some family members are present and they want to keep terminal patients connected to life support and hope for a miracle.

Studies have found that most people would not want life-sustaining care if they were in an irreversible coma, Dr. Wenger notes. On the other hand, some patients want to be kept alive at all costs, and some religions require it. "Oftentimes, people think [advance directives] are just about ending life. But you can use them to request every intervention possible," says Jon Radulovic, a spokesman for the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization.

Advance directives come in two varieties. A living will that sets out what kind of life-support care you would want in various situations, such as "if I become terminally ill or injured" or "if I become permanently unconscious." They can't anticipate every situation, so a second kind called a durable power of attorney for health care or a health-care proxy allows you to appoint someone to make health-care decisions for you.

Every state has its own versions and they are widely available online. The Caring Connections Web site of the National Hopsice and Palliative Care Organization has all 50 state forms available free at www.caringinfo.org/stateaddownload.

The Patient Self-Determination Act of 1991 requires all health-care facilities that receive Medicare or Medicaid funds to ask patients if they have advance directives and make them available. But that often occurs during the admitting process when a serious discussion is difficult.

"Five Wishes" is a less legalistic version that meets the legal requirements in 40 states. It's available from www.agingwithdignity.org for $5 a copy.

What you can specify:

Most state forms are brief, setting out hypothetical situations and giving options such as being put on a ventilator, receiving cardiopulmonary resuscitation, or receiving food or water artificially.

Five Wishes adds a third option in which you can specify that such life-support measures may be started, but then stopped if a doctor says they're not doing any good. It also asks whether you want to die at home or in a hospice and whether you would want pain medication, even if it put you to sleep. "Some people want to be awake and communicating with their family as long as possible," says Paul Malley, president of Aging with Dignity, which distributes Five Wishes. "Other people don't want to be in pain—it's their greatest fear."

Sometimes alleviating pain can also hasten death—and that's something patients should understand. "Most people want to live and they don't want to suffer and sometimes those can't both occur," says Christine Blasky, associate director of ICU at Salem Hospital in Salem, Mass.

"I put huge boxes and exclamation points around 'I do not want to be in pain,'" says Ms. Seeley, the stroke-unit nurse, who has filled out a Five Wishes form even though she is only 27. "I don't want somebody to have the burden of making a decision for me. I've seen it. It's gut-wrenching."

Connie Paeglow was given the Five Wishes form at a hospital in Denver when her husband, Wes, was diagnosed with cirrhosis of the liver and hepatitis C in 1998. He designated her as his health-care agent, said he didn't want to go on a ventilator if he couldn't breathe for himself and chose hospice care if his condition became terminal. Wes, who died in 2003, also specified that he wanted his favorite music—"Superman" by Five for Fighting—playing when hHaving all that in writing helped settle disputes with other family members, who wanted everything possible done for him, says Mrs. Paeglow, who now helps other families and patients with Five Wishes.

What do to with the forms:

Advance directives do not need to be filed officially. They go into effect automatically as soon as they are signed and witnessed; some states also require notarization. It's important to give your family members and doctors copies, or at least instructions on how to access them. Some states have electronic registries that store advance directives online. Google Health has started a similar free online service. See www.google.com/intl/en/health/advance-directive.html.

How to have the discussion:

The best time to begin considering advance directives is long before a health-care crisis looms. Having a doctor involved can be useful for answering medical questions. Medicare reimburses doctors for such discussions in some circumstances.

"We call these part of the important discussions in later life, along with 'When is it time to stop driving?' and 'When do you need help at home?'" says AARP President Jennie Chin Hansen. She adds that older people are often less reticent about discussing death than younger people suspect. "When you're 90 years old, it's not like you haven't thought about it, but it may be that nobody has ever asked you," she says.

Aging With Dignity's Next Steps booklet lists many possible ways to begin the conversation with loved ones, such as mentioning your own end-of-life preferences, or discussing the forms as a family group. "Everybody 18 and older should think of what they would want in case of an emergency. Let your family know, 'Here's what I value. Here's what's important to me,'" says Mr. Malley.

Are Living Wills the Answer?

By Drake Bennett

Whether they thinkher life was unduly prolonged or cruelly curtailed, one thing most people can agree on in the wake of Terri Schiavo's death is the importance of a living will: a document, also known as an ''advance directive,'' making clear the sort of care a person does and does not want should they find themselves unable to communicate their wishes. The nonprofit organization Aging with Dignity, distributor of one of the most popular living will forms, estimates a tenfold increase in requests due to the Schiavo case.

But how useful are living wills? According to many of the people actually responsible for drawing up and trying to follow such directives, not terribly. ''Enough. The living will has failed, and it is time to say so,'' Angela Fagerlin and Carl Schneider, a medical research scientist and a law professor, respectively, at the University of Michigan, declared last year in an article in the journal of the The Hastings Center, a bioethics research institute. And among counselors, doctors, and lawyers, that position isn't in fact so extreme.

For one thing, people change their minds, and a living will may be obsolete by the time its signer is in a condition to need it. As Steve O'Neill, a social worker and lawyer and the assistant director of the Ethics Support Service at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, puts it, ''For any of us, what would be important to me now, at this point in my life, might be different from when I was 25 years old, before I had kids. Say you fill one out when you're 25 and you're now 75. Is it still accurate?''

Research suggests that such shifts are often large - Fagerlin and Schneider's meta-analysis of 11 such studies found that ''over periods as short as two years, almost one-third of preferences for life-sustaining medical treatments changed'' - and imperceptible enough that a person might not think there's any need to change their living will.

A person's attitude about living with a debilitating illness is especially likely to change when they find themselves ill. According to Diane Coleman, founder of the disability-rights organization Not Dead Yet, ''Disabled people are very familiar with this process. They think they'd rather die than live a certain way, then they discover, Oh gee, I don't feel that way after all.''' The difficulty, of course, is that the sorts of conditions in which a living will come into play are by definition those in which it's impossible to know whether a patient has changed his mind.

Even without such a reconsideration, circumstances can complicate what were originally simple medical instructions - especially when, as is often the case, the signer of the living will isn't terribly knowledgeable about medical matters in the first place. Nancy Coleman, director of the American Bar Association's Commission on Law and Aging (and no relation to Diane Coleman), offers the hypothetical example of a person who had signed a living will demanding not to be given health care if ill with a terminal disease or severe dementia. If that person were to develop Alzheimer's disease and then fall and break her hip, a literal interpretation of the living will would demand that nothing be done for the hip.

Hospital staff, therefore, tend to treat living wills not as strict instructions but as guides to a patient's general attitudes. Or they just ignore them, as several studies have shown. According to Jay D. Rosenbaum, a partner at the Boston law firm Palmer & Dodge currently teaching a wills and trusts class at Harvard Law School, ''Often, doctors do what doctors do notwithstanding any legal document.''

A better solution, according to many involved in end-of-life care situations, is to designate a health care proxy, someone entrusted to make medical decisions in one's stead. According to the ABA's Coleman, the result ''gives the patient an advocate and makes for a much stronger document.'' But this depends on the assumption that a proxy is acting in the patient's best interest. As both the Schiavo case and, closer to home, the recent protracted legal battle over the fate of Barbara Howe (a 79-year-old Dorchester woman with late-stage Lou Gehrig's disease) have made clear, such interests can be bitterly contested.

Designating a health care proxy also happens to be the only option for patients in Massachusetts, where living wills are not legally binding. Nevertheless, John J. Paris, a Jesuit priest and bioethics professor at Boston College, remains a staunch living will proponent: ''Massachusetts law certainly doesn't prohibit your drawing up a living will. Your proxy needs to know what you want. What's the best way of conveying that? Put it into writing.''

Living wills, for all their limits, are often the most complete source of information as to someone's wishes. ''We can never know what it is under every conceivable circumstance that someone would have wanted,'' says Paris. ''We can never have that level of certitude. At a certain point we have to take the existing best option. The perfect is sometimes the enemy of the good.”

Medical Due Diligence: A Living Will Should Spell Out the Specifics

By Jane E. Brody : Personal Health NY Times : November 28, 2006

When I ask people whether and how they have made preparations for the ends of their lives, the most frequent response is, “Well, I have a living will.” But chances are they are unaware of the serious limitations inherent in such a document and how it is likely to be interpreted by medical personnel should a life-threatening crisis arise.

A living will is an advance directive, a document that states your wishes about how you should be cared for at the end of your life. It is meant to be activated when you are unable to say what you do or do not want to be done medically — if, for example, you are in a terminal condition, your heart and breathing cease, you are in a persistent vegetative state because of severe brain damage or you are too demented to understand the situation.

A living will lists your general preferences for or against life-prolonging treatment like cardiopulmonary resuscitation if your heart suddenly stops, or mechanical respiration if you cannot breathe well enough on your own. But the simple statements contained in most living wills, more often than not, are hard to apply to the great variety of medical situations that can arise.

For example, let’s say you’re a 70-year-old active retiree with congestive heart failure who develops pneumonia and has trouble breathing. You go to the emergency room, living will in hand, stating that if you become terminally ill, you do not want to be treated with antibiotics or placed on a ventilator.

Open to Misinterpretation

The admitting physician reading your living will may interpret it as a “do not resuscitate,” or D.N.R., statement, meaning you want no treatment for your life-threatening infection, in which case you would probably die. Yet a course of antibiotics and a week or so with assisted breathing could restore you to your previously active state.

Dr. Ferdinando L. Mirarchi, chairman of emergency medicine at Hamot Medical Center in Erie, Pa., tells of a very active 64-year-old woman who nearly died because a nurse read her living will as a D.N.R. statement. The woman had slipped on ice and broken a leg, which was reset surgically. On the second postoperative day she began bleeding in her abdomen, and excreted and vomited blood. But the nurse saw her living will and told the physician on call that she was D.N.R. and thus did not warrant admission to the intensive care unit. Fortunately, another physician overrode the nurse’s interpretation and resuscitated the woman, who successfully underwent emergency surgery to stop the bleeding.

Living wills became popular — and were established as legally binding documents in all states except New York, Massachusetts and Michigan — after personal experiences and highly publicized cases like that of Terri Schiavo demonstrated the futility of prolonging lives that met few people’s definition of living.

Countless billions of dollars have been spent to support the hearts and lungs of people who will never leave the hospital alive. Many people, appalled by these torturously medicalized deaths, completed a notarized document to prevent this when they neared the end of their lives. About 20 percent of the population has a living will. But will it really help, or might it harm?

An Improved Document

Dr. Mirarchi has studied how health professionals interpret living wills and found that the overwhelming majority think they mean that the patient wants to be treated as D.N.R., when in fact aggressive life-saving interventions could restore some patients to their previous state of health.

Accordingly, he has devised a more comprehensive living will — an advance directive he calls a medical living will with “code status” — that people can fill out in consultation with their physicians and perhaps an attorney to help assure they get the kind of care they would want if they could ask for it. The “code status” tells medical personnel exactly how someone wants to be treated in a life-threatening medical emergency, removing the guesswork.

If, for example, you choose “full code,” the directive would say: “I would like to receive all lifesaving and supportive measures should an emergency arise. Should my condition fail to improve and I am no longer able to make my own decisions, then I would like my advance directive to be active and followed.”

Only at that point, then, would individually stated requests be honored, such as not being resuscitated, defibrillated, ventilated, fed by tube, transfused, given antibiotics or placed on a dialysis machine.

You could also choose “full code except cardiac arrest,” meaning that all measures short of restarting your stopped heart should be tried. Or let’s say you are a terminally ill cancer patient and recognize the futility of continued treatment. You could choose “comfort care, hospice care” and have only your symptoms treated to ease your departure from this life. Dr. Mirarchi’s reasons for the revised living will are spelled out in his forthcoming book, “Understanding Your Living Will: What You Need to Know Before a Medical Emergency” (Addicus Books).

Dr. Mirarchi strongly recommends that people periodically review and update their living wills as needs and medical conditions change. He points out that if you choose to be an organ donor, your living will should state that and give permission to temporarily suspend the document to preserve the viability of your organs.

Medical consultants writing in Patient Care (Nov. 15, 2000) noted that “the less inclusive a living will is, the more trouble it can cause.” Doctors may be uncomfortable following vague directives. The consultants suggested that living wills could be more useful if the directives were disease specific. For example, if you have emphysema, you may want to accept antibiotics and mechanical ventilation if you develop pneumonia, but you may not want such treatment if you are near death from cancer.

Your living will should also state that you (or your heirs) will not sue health care workers or facilities for following your stated wishes. The document can also call for a two-physician conference before life-prolonging treatments are withdrawn. The final document should be notarized.

Make several copies of your completed living will. File them with your personal physician or local medical center, your next of kin and attorney, and include a copy with your medical records and your last will and testament. You might also carry a wallet-size card stating your chosen “status code,” emergency information and name and phone number of your health care proxy.

Have a Health Care Proxy, Too

As may already be apparent, it is not enough to have a living will. You should also assign someone you trust to voice your medical wishes when you cannot speak for yourself. That person should first have a detailed conversation with you about how you want to be treated under various circumstances and also have a copy of your living will.

It may be best if that person has no vested interest in your estate and is younger than you. In most states, the health care proxy is recognized as acting for the patient, compelling medical personnel to follow the proxy’s instructions.

Finally, it should also be obvious that both a living will and a health care proxy should be in place as soon as a person turns 18 and becomes an adult in the eyes of the law. You never know how old or healthy you may be when its instructions are needed. Ms. Schiavo was only 26 when she suffered a brain-damaging cardiac arrest.

Making our wishes known

By Dr. Terry L. Schraeder : Boston Globe Article : December 5, 2006

Many people in my generation are watching and worrying as our parents get further and further into their senior years. My own 75-year-old mother's health is slowly but certainly ebbing. Each week there seems to be a new health issue that needs attention: something on her body to be scoped, or biopsied, X-rayed or MRI'd.

She and I talk about such things. But she has not yet fully shared her desires about her death -- about what she does and does not want to do when the end draws near. I am reluctant to ask too much. Even for me, her daughter and a doctor, it is a difficult conversation to have. Especially with the holidays at hand, who wants to talk about that? But having witnessed excruciating hospital bedside discussions occurring far too late or "do not resuscitate" orders being considered far too early, I can attest to the importance of discussing what doctors delicately call "end-of-life issues." We all need to ask our loved ones how they feel about organ donation, life support, and living wills. Anything in particular they want at the end? And we need to tell them of our own wishes. I don't want to be on a ventilator. Or I want everything possible to stay alive. I do not want to donate my organs. Or I do.

It seems particularly crazy to talk about these difficult issues at a holiday time . Yet this is the time of year when families are physically close together, and people who live far from their loved ones can have crucial conversations face to face.

This is also when we ask those closest to us, "What do you really want this year?" Instead of assuming we know what our spouse, parent, sibling, or friend desires for a gift (and to ensure we give them exactly what they want), we simply ask -- sometimes reluctantly, sometimes not so reluctantly. There are far more important issues that we should discuss in just as straightforward a manner.

"How can I make sure you have what you want when you can no longer speak for yourself?" we need to say.

And we need to ask, "Can I tell you now about what I want when I die?"

Unfortunately, baby boomers like me are truly unprepared for these issues. When we hit the senior years, we will make up a tidal wave of elderly. We will no doubt overwhelm our current system at a time when our society, nursing homes, healthcare, and government will least be able to help us. It is imperative that we talk about a plan with our loved ones now and try to put those plans in place, both personally by drafting a living will or advanced directive and financially by securing our insurance, savings plans, and wills.

As our own health fails and we can no longer maneuver through our multi-level homes or in our high-level sport utility vehicles -- and we may haveno children to take care of us -- we need to take responsibility for ourselves and our ultimate exits. Death itself won't be a suffering, isolating, and painful moment but a time when our loved ones and friends are near to us and we are leaving this life the way we want to.

Our generation has certainly taken on big issues and dilemmas before and managed them well. But unfortunately, when our time comes for nursing homes and advanced directives or hospice care, we may no longer have the intellectual capacity, influence, or energy to figure things out so well.

Putting our wishes on paper right now is easy. Living will forms are available from hospitals, attorneys, libraries, and the Internet. Organ donations cards are available from motor vehicle registries and at organdonor.gov.

If we all make our wishes clear, if we have discussions with those we love, perhaps we can help ensure the end is what we planned it to be.

This is what I want this year. What do you want?

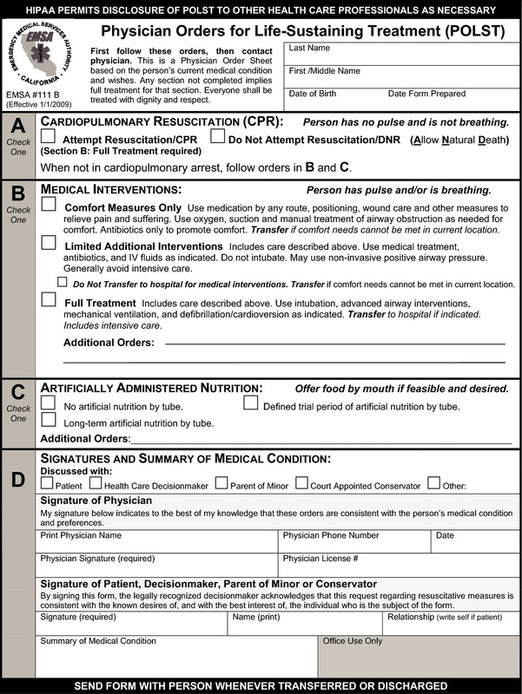

Putting Muscle Behind End-of-Life Wishes

By Jane E. Brody : NY Times Article : February 24, 2009

My friend’s 94-year-old father was near death from congestive heart failure. He had requested in writing that no extraordinary measures be used to prolong his life; he wanted to die peacefully at home. But one day when he began struggling to breathe, my friend, his daughter, panicked and called 911.

Although the paramedics were told of his wishes, they followed established procedures and went right to work, helping him breathe and taking him to the hospital. But they told his distressed daughter that if he stopped breathing again, she should wait 20 minutes before calling 911, at which point resuscitation would not be possible. A few days later, her father died peacefully at home.

Millions of Americans have living wills that they think provide clear instructions to medical personnel about what should and should not be done if their lives hang in the balance and they cannot speak for themselves. Yet in case after case, study after study, it seems that these documents fail to result in the desired end among patients in hospitals and nursing homes.

Misconceptions

Now a new study confirms that confusion about interpreting living wills prevails in prehospital settings, as well. The study, conducted among 150 emergency medical technicians and paramedics by a team at Hamot Medical Center in Erie, Pa., and published this month in The Journal of Emergency Medicine, found that concern for patient safety can collide with confusion about the intent of living wills and do-not-resuscitate orders.

Even when a living will did not specifically say “do not resuscitate,” 90 percent of the emergency medical technicians and paramedics interpreted the mere existence of a living will to mean they should provide only comfort and end-of-life care and not attempt to save the person’s life.

“A living will does not necessarily say, ‘Do not treat me if I have a critical illness.’ This is a major misconception,” said Dr. Ferdinando Mirarchi, the director of emergency medicine at Hamot and the director of the study.

The study did find that when the living will incorporated a code status, like “full code,” meaning that every effort should be made to resuscitate the patient, it was much more likely that emergency responders would provide life-saving care.

But more often than not, the reverse situation occurs. Patients who have clearly specified that no attempt should be made to prolong life if they become unresponsive are nonetheless resuscitated or hooked up to respirators and feeding tubes.

Uncooperative Doctors

In “To Die Well,” Dr. Sidney Wanzer, a co-author, relates the experience of his 92-year-old mother, who was living in a nursing home with advanced Alzheimer’s disease. Long before the disease had overtaken her mind, he wrote, she had completed a living will stating that “she did not want her death prolonged by medical treatment if the quality of her life ever became so poor that there was no significant intellectual activity or reward.” Yet when her heart developed an irregular rhythm that would have soon been fatal, the doctor in charge implanted a pacemaker, which kept her alive another five years in a helpless state “lacking all dignity, totally contrary to her written request,” Dr. Wanzer wrote.

“I thought everything was all set,” he continued. “But we made a big mistake. We did not ask her doctor explicitly, ‘Do you agree with this approach and will you promise to adhere to our mother’s wishes?’ ”

As more and more Americans live beyond the eighth decade, when the risk of dementia rises significantly, cases in which a doctor chooses medical intervention — in the presence or absence of a patient’s wishes — are likely to become more common. Yet in a 1999 study by Dr. Dwenda K. Gjerdingen and colleagues at the University of Minnesota among 84 cognitively normal men and women 65 and older, three-fourths said they would not want to be resuscitated, put on a respirator or nourished by a feeding tube at the end of life if they had mild dementia, and 95 percent would reject such measures if they had severe dementia.

A costly, four-year, multicenter study begun in 1989 sought to improve doctors’ ability to interpret and carry out patients’ wishes for end-of-life care. Yet informing doctors of what hospitalized patients wanted and placing that information in the medical records did nothing to influence the care they provided. Having a living will had no effect on whether doctors used resuscitative efforts at the end of life. The doctors, it seemed, simply could not let patients go even if that was a patient’s explicit wish.

Help for First Responders

Last year, a law went into effect in New York State to help solve the problem of emergency responders’ being forced to give invasive care to people at the end of life, even if that is contrary to the wishes of the dying person and relatives.

The law allows the use of a bright pink form, the Medical Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment form, which lets people to indicate whether they would want intravenous fluids, medications like antibiotics, a feeding tube, a breathing tube or other interventions, and whether they want to go to a hospital. On the form, which is signed by a physician and is considered a medical order, patients can also specify that they want only comfort care or would want a trial of certain treatments.

Before the law was passed, the only directive emergency technicians could obey was an out-of-hospital “do not resuscitate” form specifying that no cardiopulmonary resuscitation be tried if a patient stopped breathing or had no pulse. Not covered were the myriad cases like that of my friend’s father, in which patients were near the end of life but not in cardiac arrest.

California, North Carolina, Oregon, Washington, West Virginia and parts of Wisconsin also have programs that use these physicians’ order forms to clarify treatment and end-of-life decisions for medical personnel. Programs are being developed in still other states.

Can similar improvements in adherence to advance directives be made for all of us, including hospitalized patients? One approach is to assign a trusted person to be your health care proxy, to hold dual power of attorney for health care when you are unable to make your wishes known to medical personnel. Discuss your wishes under various conditions with that person, give the person your detailed living will and complete a health care proxy form. Update the information if your feelings change.

My husband and I carry our proxy forms in our wallets, to help medical personnel figure out whom to contact in an emergency and how to proceed in accordance with our wishes.

You can find more information about advance directives and other end-of-life issues in the newly published “Jane Brody’s Guide to the Great Beyond” (Random House).

By Melinda Beck : WSJ Article : August 18, 2009

Forget about the health-reform debate for the moment. Should you have a living will specifying the kind of care you'd want at the end of life if you couldn't speak for yourself?

Doctors, lawmakers and ethicists have been urging Americans to fill out advance directives, as they are called, for decades. Yet less than a third of American adults, and less than half of nursing-home patients, have done so. Many people don't understand the options or the consequences, or they are baffled by the legalities, according to a report prepared for Congress last year by Rand Corp., and doctors and patients alike are reluctant to broach the subject of death.

"Everybody knows they're going to die, but it's really scary to think about how," says Audrey Seeley, a registered nurse in the stroke unit at Inova Hospital in Falls Church, Va., who sees many patients who are suddenly seriously incapacitated. "A lot of people say, 'If I get to that point, I don't care what happens to me.' But your family does."

Connie Paeglow works with elderly people and their families to discuss end-of-life preferences, including deciding on life-support care using the Five Wishes advanced-directives form.

Indeed, advance directives are as much for the living as for the dying. Without specific instructions, family members may have to decide whether you would want to be kept alive artificially, what level of disability you'd be willing to live with and how to let you die if you had no hope of recovery.

If family members aren't available, doctors are generally empowered to discontinue medical care they deem futile. But that rarely happens, largely for legal reasons, says Neil Wenger, director, UCLA Health System Ethics Center, and one of the authors of the Rand report. More often, he says, some family members are present and they want to keep terminal patients connected to life support and hope for a miracle.

Studies have found that most people would not want life-sustaining care if they were in an irreversible coma, Dr. Wenger notes. On the other hand, some patients want to be kept alive at all costs, and some religions require it. "Oftentimes, people think [advance directives] are just about ending life. But you can use them to request every intervention possible," says Jon Radulovic, a spokesman for the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization.

Advance directives come in two varieties. A living will that sets out what kind of life-support care you would want in various situations, such as "if I become terminally ill or injured" or "if I become permanently unconscious." They can't anticipate every situation, so a second kind called a durable power of attorney for health care or a health-care proxy allows you to appoint someone to make health-care decisions for you.

Every state has its own versions and they are widely available online. The Caring Connections Web site of the National Hopsice and Palliative Care Organization has all 50 state forms available free at www.caringinfo.org/stateaddownload.

The Patient Self-Determination Act of 1991 requires all health-care facilities that receive Medicare or Medicaid funds to ask patients if they have advance directives and make them available. But that often occurs during the admitting process when a serious discussion is difficult.

"Five Wishes" is a less legalistic version that meets the legal requirements in 40 states. It's available from www.agingwithdignity.org for $5 a copy.

What you can specify:

Most state forms are brief, setting out hypothetical situations and giving options such as being put on a ventilator, receiving cardiopulmonary resuscitation, or receiving food or water artificially.

Five Wishes adds a third option in which you can specify that such life-support measures may be started, but then stopped if a doctor says they're not doing any good. It also asks whether you want to die at home or in a hospice and whether you would want pain medication, even if it put you to sleep. "Some people want to be awake and communicating with their family as long as possible," says Paul Malley, president of Aging with Dignity, which distributes Five Wishes. "Other people don't want to be in pain—it's their greatest fear."

Sometimes alleviating pain can also hasten death—and that's something patients should understand. "Most people want to live and they don't want to suffer and sometimes those can't both occur," says Christine Blasky, associate director of ICU at Salem Hospital in Salem, Mass.

"I put huge boxes and exclamation points around 'I do not want to be in pain,'" says Ms. Seeley, the stroke-unit nurse, who has filled out a Five Wishes form even though she is only 27. "I don't want somebody to have the burden of making a decision for me. I've seen it. It's gut-wrenching."

Connie Paeglow was given the Five Wishes form at a hospital in Denver when her husband, Wes, was diagnosed with cirrhosis of the liver and hepatitis C in 1998. He designated her as his health-care agent, said he didn't want to go on a ventilator if he couldn't breathe for himself and chose hospice care if his condition became terminal. Wes, who died in 2003, also specified that he wanted his favorite music—"Superman" by Five for Fighting—playing when hHaving all that in writing helped settle disputes with other family members, who wanted everything possible done for him, says Mrs. Paeglow, who now helps other families and patients with Five Wishes.

What do to with the forms:

Advance directives do not need to be filed officially. They go into effect automatically as soon as they are signed and witnessed; some states also require notarization. It's important to give your family members and doctors copies, or at least instructions on how to access them. Some states have electronic registries that store advance directives online. Google Health has started a similar free online service. See www.google.com/intl/en/health/advance-directive.html.

How to have the discussion:

The best time to begin considering advance directives is long before a health-care crisis looms. Having a doctor involved can be useful for answering medical questions. Medicare reimburses doctors for such discussions in some circumstances.

"We call these part of the important discussions in later life, along with 'When is it time to stop driving?' and 'When do you need help at home?'" says AARP President Jennie Chin Hansen. She adds that older people are often less reticent about discussing death than younger people suspect. "When you're 90 years old, it's not like you haven't thought about it, but it may be that nobody has ever asked you," she says.

Aging With Dignity's Next Steps booklet lists many possible ways to begin the conversation with loved ones, such as mentioning your own end-of-life preferences, or discussing the forms as a family group. "Everybody 18 and older should think of what they would want in case of an emergency. Let your family know, 'Here's what I value. Here's what's important to me,'" says Mr. Malley.

Are Living Wills the Answer?

By Drake Bennett

Whether they thinkher life was unduly prolonged or cruelly curtailed, one thing most people can agree on in the wake of Terri Schiavo's death is the importance of a living will: a document, also known as an ''advance directive,'' making clear the sort of care a person does and does not want should they find themselves unable to communicate their wishes. The nonprofit organization Aging with Dignity, distributor of one of the most popular living will forms, estimates a tenfold increase in requests due to the Schiavo case.

But how useful are living wills? According to many of the people actually responsible for drawing up and trying to follow such directives, not terribly. ''Enough. The living will has failed, and it is time to say so,'' Angela Fagerlin and Carl Schneider, a medical research scientist and a law professor, respectively, at the University of Michigan, declared last year in an article in the journal of the The Hastings Center, a bioethics research institute. And among counselors, doctors, and lawyers, that position isn't in fact so extreme.

For one thing, people change their minds, and a living will may be obsolete by the time its signer is in a condition to need it. As Steve O'Neill, a social worker and lawyer and the assistant director of the Ethics Support Service at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, puts it, ''For any of us, what would be important to me now, at this point in my life, might be different from when I was 25 years old, before I had kids. Say you fill one out when you're 25 and you're now 75. Is it still accurate?''

Research suggests that such shifts are often large - Fagerlin and Schneider's meta-analysis of 11 such studies found that ''over periods as short as two years, almost one-third of preferences for life-sustaining medical treatments changed'' - and imperceptible enough that a person might not think there's any need to change their living will.

A person's attitude about living with a debilitating illness is especially likely to change when they find themselves ill. According to Diane Coleman, founder of the disability-rights organization Not Dead Yet, ''Disabled people are very familiar with this process. They think they'd rather die than live a certain way, then they discover, Oh gee, I don't feel that way after all.''' The difficulty, of course, is that the sorts of conditions in which a living will come into play are by definition those in which it's impossible to know whether a patient has changed his mind.

Even without such a reconsideration, circumstances can complicate what were originally simple medical instructions - especially when, as is often the case, the signer of the living will isn't terribly knowledgeable about medical matters in the first place. Nancy Coleman, director of the American Bar Association's Commission on Law and Aging (and no relation to Diane Coleman), offers the hypothetical example of a person who had signed a living will demanding not to be given health care if ill with a terminal disease or severe dementia. If that person were to develop Alzheimer's disease and then fall and break her hip, a literal interpretation of the living will would demand that nothing be done for the hip.

Hospital staff, therefore, tend to treat living wills not as strict instructions but as guides to a patient's general attitudes. Or they just ignore them, as several studies have shown. According to Jay D. Rosenbaum, a partner at the Boston law firm Palmer & Dodge currently teaching a wills and trusts class at Harvard Law School, ''Often, doctors do what doctors do notwithstanding any legal document.''

A better solution, according to many involved in end-of-life care situations, is to designate a health care proxy, someone entrusted to make medical decisions in one's stead. According to the ABA's Coleman, the result ''gives the patient an advocate and makes for a much stronger document.'' But this depends on the assumption that a proxy is acting in the patient's best interest. As both the Schiavo case and, closer to home, the recent protracted legal battle over the fate of Barbara Howe (a 79-year-old Dorchester woman with late-stage Lou Gehrig's disease) have made clear, such interests can be bitterly contested.

Designating a health care proxy also happens to be the only option for patients in Massachusetts, where living wills are not legally binding. Nevertheless, John J. Paris, a Jesuit priest and bioethics professor at Boston College, remains a staunch living will proponent: ''Massachusetts law certainly doesn't prohibit your drawing up a living will. Your proxy needs to know what you want. What's the best way of conveying that? Put it into writing.''

Living wills, for all their limits, are often the most complete source of information as to someone's wishes. ''We can never know what it is under every conceivable circumstance that someone would have wanted,'' says Paris. ''We can never have that level of certitude. At a certain point we have to take the existing best option. The perfect is sometimes the enemy of the good.”

Medical Due Diligence: A Living Will Should Spell Out the Specifics

By Jane E. Brody : Personal Health NY Times : November 28, 2006

When I ask people whether and how they have made preparations for the ends of their lives, the most frequent response is, “Well, I have a living will.” But chances are they are unaware of the serious limitations inherent in such a document and how it is likely to be interpreted by medical personnel should a life-threatening crisis arise.

A living will is an advance directive, a document that states your wishes about how you should be cared for at the end of your life. It is meant to be activated when you are unable to say what you do or do not want to be done medically — if, for example, you are in a terminal condition, your heart and breathing cease, you are in a persistent vegetative state because of severe brain damage or you are too demented to understand the situation.

A living will lists your general preferences for or against life-prolonging treatment like cardiopulmonary resuscitation if your heart suddenly stops, or mechanical respiration if you cannot breathe well enough on your own. But the simple statements contained in most living wills, more often than not, are hard to apply to the great variety of medical situations that can arise.

For example, let’s say you’re a 70-year-old active retiree with congestive heart failure who develops pneumonia and has trouble breathing. You go to the emergency room, living will in hand, stating that if you become terminally ill, you do not want to be treated with antibiotics or placed on a ventilator.

Open to Misinterpretation

The admitting physician reading your living will may interpret it as a “do not resuscitate,” or D.N.R., statement, meaning you want no treatment for your life-threatening infection, in which case you would probably die. Yet a course of antibiotics and a week or so with assisted breathing could restore you to your previously active state.

Dr. Ferdinando L. Mirarchi, chairman of emergency medicine at Hamot Medical Center in Erie, Pa., tells of a very active 64-year-old woman who nearly died because a nurse read her living will as a D.N.R. statement. The woman had slipped on ice and broken a leg, which was reset surgically. On the second postoperative day she began bleeding in her abdomen, and excreted and vomited blood. But the nurse saw her living will and told the physician on call that she was D.N.R. and thus did not warrant admission to the intensive care unit. Fortunately, another physician overrode the nurse’s interpretation and resuscitated the woman, who successfully underwent emergency surgery to stop the bleeding.

Living wills became popular — and were established as legally binding documents in all states except New York, Massachusetts and Michigan — after personal experiences and highly publicized cases like that of Terri Schiavo demonstrated the futility of prolonging lives that met few people’s definition of living.

Countless billions of dollars have been spent to support the hearts and lungs of people who will never leave the hospital alive. Many people, appalled by these torturously medicalized deaths, completed a notarized document to prevent this when they neared the end of their lives. About 20 percent of the population has a living will. But will it really help, or might it harm?

An Improved Document

Dr. Mirarchi has studied how health professionals interpret living wills and found that the overwhelming majority think they mean that the patient wants to be treated as D.N.R., when in fact aggressive life-saving interventions could restore some patients to their previous state of health.

Accordingly, he has devised a more comprehensive living will — an advance directive he calls a medical living will with “code status” — that people can fill out in consultation with their physicians and perhaps an attorney to help assure they get the kind of care they would want if they could ask for it. The “code status” tells medical personnel exactly how someone wants to be treated in a life-threatening medical emergency, removing the guesswork.

If, for example, you choose “full code,” the directive would say: “I would like to receive all lifesaving and supportive measures should an emergency arise. Should my condition fail to improve and I am no longer able to make my own decisions, then I would like my advance directive to be active and followed.”

Only at that point, then, would individually stated requests be honored, such as not being resuscitated, defibrillated, ventilated, fed by tube, transfused, given antibiotics or placed on a dialysis machine.

You could also choose “full code except cardiac arrest,” meaning that all measures short of restarting your stopped heart should be tried. Or let’s say you are a terminally ill cancer patient and recognize the futility of continued treatment. You could choose “comfort care, hospice care” and have only your symptoms treated to ease your departure from this life. Dr. Mirarchi’s reasons for the revised living will are spelled out in his forthcoming book, “Understanding Your Living Will: What You Need to Know Before a Medical Emergency” (Addicus Books).

Dr. Mirarchi strongly recommends that people periodically review and update their living wills as needs and medical conditions change. He points out that if you choose to be an organ donor, your living will should state that and give permission to temporarily suspend the document to preserve the viability of your organs.

Medical consultants writing in Patient Care (Nov. 15, 2000) noted that “the less inclusive a living will is, the more trouble it can cause.” Doctors may be uncomfortable following vague directives. The consultants suggested that living wills could be more useful if the directives were disease specific. For example, if you have emphysema, you may want to accept antibiotics and mechanical ventilation if you develop pneumonia, but you may not want such treatment if you are near death from cancer.

Your living will should also state that you (or your heirs) will not sue health care workers or facilities for following your stated wishes. The document can also call for a two-physician conference before life-prolonging treatments are withdrawn. The final document should be notarized.

Make several copies of your completed living will. File them with your personal physician or local medical center, your next of kin and attorney, and include a copy with your medical records and your last will and testament. You might also carry a wallet-size card stating your chosen “status code,” emergency information and name and phone number of your health care proxy.

Have a Health Care Proxy, Too

As may already be apparent, it is not enough to have a living will. You should also assign someone you trust to voice your medical wishes when you cannot speak for yourself. That person should first have a detailed conversation with you about how you want to be treated under various circumstances and also have a copy of your living will.

It may be best if that person has no vested interest in your estate and is younger than you. In most states, the health care proxy is recognized as acting for the patient, compelling medical personnel to follow the proxy’s instructions.

Finally, it should also be obvious that both a living will and a health care proxy should be in place as soon as a person turns 18 and becomes an adult in the eyes of the law. You never know how old or healthy you may be when its instructions are needed. Ms. Schiavo was only 26 when she suffered a brain-damaging cardiac arrest.

Making our wishes known

By Dr. Terry L. Schraeder : Boston Globe Article : December 5, 2006

Many people in my generation are watching and worrying as our parents get further and further into their senior years. My own 75-year-old mother's health is slowly but certainly ebbing. Each week there seems to be a new health issue that needs attention: something on her body to be scoped, or biopsied, X-rayed or MRI'd.

She and I talk about such things. But she has not yet fully shared her desires about her death -- about what she does and does not want to do when the end draws near. I am reluctant to ask too much. Even for me, her daughter and a doctor, it is a difficult conversation to have. Especially with the holidays at hand, who wants to talk about that? But having witnessed excruciating hospital bedside discussions occurring far too late or "do not resuscitate" orders being considered far too early, I can attest to the importance of discussing what doctors delicately call "end-of-life issues." We all need to ask our loved ones how they feel about organ donation, life support, and living wills. Anything in particular they want at the end? And we need to tell them of our own wishes. I don't want to be on a ventilator. Or I want everything possible to stay alive. I do not want to donate my organs. Or I do.

It seems particularly crazy to talk about these difficult issues at a holiday time . Yet this is the time of year when families are physically close together, and people who live far from their loved ones can have crucial conversations face to face.

This is also when we ask those closest to us, "What do you really want this year?" Instead of assuming we know what our spouse, parent, sibling, or friend desires for a gift (and to ensure we give them exactly what they want), we simply ask -- sometimes reluctantly, sometimes not so reluctantly. There are far more important issues that we should discuss in just as straightforward a manner.

"How can I make sure you have what you want when you can no longer speak for yourself?" we need to say.

And we need to ask, "Can I tell you now about what I want when I die?"

Unfortunately, baby boomers like me are truly unprepared for these issues. When we hit the senior years, we will make up a tidal wave of elderly. We will no doubt overwhelm our current system at a time when our society, nursing homes, healthcare, and government will least be able to help us. It is imperative that we talk about a plan with our loved ones now and try to put those plans in place, both personally by drafting a living will or advanced directive and financially by securing our insurance, savings plans, and wills.

As our own health fails and we can no longer maneuver through our multi-level homes or in our high-level sport utility vehicles -- and we may haveno children to take care of us -- we need to take responsibility for ourselves and our ultimate exits. Death itself won't be a suffering, isolating, and painful moment but a time when our loved ones and friends are near to us and we are leaving this life the way we want to.

Our generation has certainly taken on big issues and dilemmas before and managed them well. But unfortunately, when our time comes for nursing homes and advanced directives or hospice care, we may no longer have the intellectual capacity, influence, or energy to figure things out so well.

Putting our wishes on paper right now is easy. Living will forms are available from hospitals, attorneys, libraries, and the Internet. Organ donations cards are available from motor vehicle registries and at organdonor.gov.

If we all make our wishes clear, if we have discussions with those we love, perhaps we can help ensure the end is what we planned it to be.

This is what I want this year. What do you want?

Putting Muscle Behind End-of-Life Wishes

By Jane E. Brody : NY Times Article : February 24, 2009

My friend’s 94-year-old father was near death from congestive heart failure. He had requested in writing that no extraordinary measures be used to prolong his life; he wanted to die peacefully at home. But one day when he began struggling to breathe, my friend, his daughter, panicked and called 911.

Although the paramedics were told of his wishes, they followed established procedures and went right to work, helping him breathe and taking him to the hospital. But they told his distressed daughter that if he stopped breathing again, she should wait 20 minutes before calling 911, at which point resuscitation would not be possible. A few days later, her father died peacefully at home.

Millions of Americans have living wills that they think provide clear instructions to medical personnel about what should and should not be done if their lives hang in the balance and they cannot speak for themselves. Yet in case after case, study after study, it seems that these documents fail to result in the desired end among patients in hospitals and nursing homes.

Misconceptions

Now a new study confirms that confusion about interpreting living wills prevails in prehospital settings, as well. The study, conducted among 150 emergency medical technicians and paramedics by a team at Hamot Medical Center in Erie, Pa., and published this month in The Journal of Emergency Medicine, found that concern for patient safety can collide with confusion about the intent of living wills and do-not-resuscitate orders.

Even when a living will did not specifically say “do not resuscitate,” 90 percent of the emergency medical technicians and paramedics interpreted the mere existence of a living will to mean they should provide only comfort and end-of-life care and not attempt to save the person’s life.

“A living will does not necessarily say, ‘Do not treat me if I have a critical illness.’ This is a major misconception,” said Dr. Ferdinando Mirarchi, the director of emergency medicine at Hamot and the director of the study.

The study did find that when the living will incorporated a code status, like “full code,” meaning that every effort should be made to resuscitate the patient, it was much more likely that emergency responders would provide life-saving care.

But more often than not, the reverse situation occurs. Patients who have clearly specified that no attempt should be made to prolong life if they become unresponsive are nonetheless resuscitated or hooked up to respirators and feeding tubes.

Uncooperative Doctors

In “To Die Well,” Dr. Sidney Wanzer, a co-author, relates the experience of his 92-year-old mother, who was living in a nursing home with advanced Alzheimer’s disease. Long before the disease had overtaken her mind, he wrote, she had completed a living will stating that “she did not want her death prolonged by medical treatment if the quality of her life ever became so poor that there was no significant intellectual activity or reward.” Yet when her heart developed an irregular rhythm that would have soon been fatal, the doctor in charge implanted a pacemaker, which kept her alive another five years in a helpless state “lacking all dignity, totally contrary to her written request,” Dr. Wanzer wrote.

“I thought everything was all set,” he continued. “But we made a big mistake. We did not ask her doctor explicitly, ‘Do you agree with this approach and will you promise to adhere to our mother’s wishes?’ ”

As more and more Americans live beyond the eighth decade, when the risk of dementia rises significantly, cases in which a doctor chooses medical intervention — in the presence or absence of a patient’s wishes — are likely to become more common. Yet in a 1999 study by Dr. Dwenda K. Gjerdingen and colleagues at the University of Minnesota among 84 cognitively normal men and women 65 and older, three-fourths said they would not want to be resuscitated, put on a respirator or nourished by a feeding tube at the end of life if they had mild dementia, and 95 percent would reject such measures if they had severe dementia.

A costly, four-year, multicenter study begun in 1989 sought to improve doctors’ ability to interpret and carry out patients’ wishes for end-of-life care. Yet informing doctors of what hospitalized patients wanted and placing that information in the medical records did nothing to influence the care they provided. Having a living will had no effect on whether doctors used resuscitative efforts at the end of life. The doctors, it seemed, simply could not let patients go even if that was a patient’s explicit wish.

Help for First Responders

Last year, a law went into effect in New York State to help solve the problem of emergency responders’ being forced to give invasive care to people at the end of life, even if that is contrary to the wishes of the dying person and relatives.

The law allows the use of a bright pink form, the Medical Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment form, which lets people to indicate whether they would want intravenous fluids, medications like antibiotics, a feeding tube, a breathing tube or other interventions, and whether they want to go to a hospital. On the form, which is signed by a physician and is considered a medical order, patients can also specify that they want only comfort care or would want a trial of certain treatments.

Before the law was passed, the only directive emergency technicians could obey was an out-of-hospital “do not resuscitate” form specifying that no cardiopulmonary resuscitation be tried if a patient stopped breathing or had no pulse. Not covered were the myriad cases like that of my friend’s father, in which patients were near the end of life but not in cardiac arrest.

California, North Carolina, Oregon, Washington, West Virginia and parts of Wisconsin also have programs that use these physicians’ order forms to clarify treatment and end-of-life decisions for medical personnel. Programs are being developed in still other states.