- RETIREMENT ANNOUNCEMENT

- HOME PAGE

- "MYCHART" the new patient portal

- BELMONT MEDICAL ASSOCIATES

- MOUNT AUBURN HOSPITAL

- EMERGENCIES

- PRACTICE PHILOSOPHY

- MY RESUME

- TELEMEDICINE CONSULTATION

- CONTACT ME

- LAB RESULTS

- ePRESCRIPTIONS

- eREFERRALS

- RECORD RELEASE

- MEDICAL SCRIBE

- PHYSICIAN ASSISTANT (PA)

- Medicare Annual Wellness Visit

- Case management/Social work

- Quality Care Measures

- Emergency closing notice

- FEEDBACK

- Talking to your doctor

- Choosing..... and losing a doctor

- INDEX A - Z

- ALLERGIC REACTIONS

- Alternative Medicine

- Alzheimer's Disease

- Bladder Problems

- Blood disorders

- Cancer Concerns

- GENETIC TESTING FOR HEREDITARY CANCER

- Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

- Controversial Concerns

- CPR : Learn and save a life

- CRP : Inflammatory marker

- Diabetes Management

- Dizziness, Vertigo,Tinnitus and Hearing Loss

- EXERCISE

- FEMALE HEALTH

-

GASTROINTESTINAL topics

- Appendicitis

- BRAT diet

- Celiac Disease or Sprue

- Crohn's Disease

- Gastroenterologists for Colon Cancer Screening

- Colonoscopy PREP

- Constipation

- Gluten sensitivity, but not celiac disease

- Heartburn and GERD

- Hemorrhoids and Anal fissure

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- NASH : Non Alcoholic Steato Hepatitis

- FEET PROBLEMS

- HEART RELATED topics

-

INFECTIOUS DISEASES

- Antibiotic Resistance

- Cat bites >

- Clostridia difficile infection - the "antibiotic associated germ"

- CORONA VIRUS

- Dengue Fever and Chikungunya Fever

- Food borne illnesses

- Shingles Vaccine

- Hepatitis B

- Hepatitis C

- Herpes

- Influenza

- Helicobacter pylori - the "ulcer germ"

- HIV Screening

- Lyme and other tick borne diseases

- Measles

- Meningitis

- MRSA (Staph infection)

- Norovirus

- Sexually Transmitted Diseases

- Shingles (Herpes Zoster)

- Sinusitis

- West Nile Virus

- Whooping Cough (Pertussis)

- Zika virus and pregnancy

- INSURANCE related topics

- KIDNEY STONES

- LEG CRAMPS

- LIBRARY for patients

- LIFE DECISIONS

- MALE HEALTH

- Medication/Drug side effects

- MEDICAL MARIJUANA

- MENTAL HEALTH

- Miscellaneous Articles

-

NUTRITION - EXERCISE - WEIGHT

- Cholesterol : New guidelines for treatment

- Advice to lower your cholesterol

- Cholesterol : Control

- Cholesterol : Raising your HDL Level

- Exercise

- Food : Making Smart Choices

- Food : Making Poor Choices

- Food : Grape Fruit and Drug Interaction

- Food : Vitamins, Minerals and Supplements

- Omega 3 fatty acids

- Vitamin B12 deficiency

- Vitamin D

- Weight Loss

- ORTHOPEDICS

- PAIN

- PATIENTS' RIGHTS

- SKIN

- SLEEP

- SMOKING

- STROKE

- THYROID

- SUBSTANCE ABUSE

- Travel and Vaccination

- TREMOR

- Warfarin Anticoagulation

- OTHER STUFF FOLLOWS

- Fact or Opinion?

- Hippocratic Oath

- FREE ADVICE.......for what its worth!

- LAUGHTER.....is the best medicine

- Physicians Pet Peeves

- PHOTO ALBUM - its not all work!

- Cape Town, South Africa

- Tribute page

- The 100 Club

- Free Wi-Fi

HYPERTENSION / HIGH BLOOD PRESSURE

Educational video

What is High Blood Pressure (Hypertension)?

A blood pressure monitor measure the force of blood flowing in your artery. It is measured in two numbers. The systolic (higher) reading, measures the force when your heart is contracting. The diastolic (lower) reading, measures the force between heart beats (when the heart is relaxed).

If your BP is too high (hypertension), it causes wear and tear on your heart and blood vessels and increases your risk of developing coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, aneurysms and stroke.

The good news is that hypertension can be managed with medication. Lifestyle changes, such as regular exercise or activity, losing weight, stopping smoking and trying to follow a low salt diet, can also help lower blood pressure.

Blood pressure levels Systolic Diastolic

High blood pressure 140 or above 90 or above

Prehypertension 120 to 139 80 to 89

Normal adult (age 18 or older) 119 or below 79 or below

Recording your blood pressure

- Try to take your BP at the same time each day. BP is usually highest in the morning and lowest in the evening.

- Try not to smoke, eat or exercise 30 minutes before you take your BP. Best to sit in a chair with your back resting, legs uncrossed, the cuff properly applied and relax for 5 minutes before checking the reading.

- Bring your monitor to the office so that we can compare the readings and check the accuracy of the machine.

The National High Blood Pressure Education Program presented the complete Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Like its predecessors, the purpose is to provide an evidence-based approach to the prevention and management of hypertension. The key messages of this report are these:

- in those older than age 50, systolic blood pressure (BP) of greater than 140 mm Hg is a more important cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factor than diastolic BP

- beginning at 115/75 mm Hg, CVD risk doubles for each increment of 20/10 mm Hg

- those who are normotensive at 55 years of age will have a 90% lifetime risk of developing hypertension

- prehypertensive individuals (systolic BP 120 - 139 mm Hg or diastolic BP 80 - 89 mm Hg) require health-promoting lifestyle modifications to prevent the progressive rise in blood pressure and CVD

- for uncomplicated hypertension, thiazide diuretic should be used in drug treatment for most, either alone or combined with drugs from other classes

- this report delineates specific high-risk conditions that are compelling indications for the use of other antihypertensive drug classes (angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin-receptor blockers, beta-blockers, calcium channel blockers)

- two or more antihypertensive medications will be required to achieve goal BP (<140/90 mm hg, or <130/80 mm hg) for patients with diabetes and chronic kidney disease

- for patients whose BP is more than 20 mm Hg above the systolic BP goal or more than 10 mm Hg above the diastolic BP goal, initiation of therapy using two agents, one of which usually will be a thiazide diuretic, should be considered

- regardless of therapy or care, hypertension will be controlled only if patients are motivated to stay on their treatment plan.

Blood Pressure Myths and Facts

MYTH: High blood pressure is hereditary.

FACT: While heredity increases the risk of developing high blood pressure, many people with no family history also develop it.

MYTH: The only way to control high blood pressure is with medications.

FACT:: About half of adults with high blood pressure can control it with lifestyle changes including weight loss, exercise, avoiding tobacco and limiting intake of salt, alcohol and caffeine.

MYTH: I don't use table salt, so my blood pressure isn't affected.

FACT: Most sodium consumption comes from processed foods like tomato sauce, soups, condiments, canned foods and prepared mixes. Look for 'soda' and 'sodium' and the symbol 'Na' on labels, which show sodium compounds are present. Using kosher or sea salt doesn't make a difference; chemically they are the same as table salt.

MYTH: I feel fine. I don't have to worry about high blood pressure.

FACT: A third of American adults have high blood pressure—and many of them don't know it or don't experience typical symptoms. If uncontrolled, high blood pressure can lead to severe health problems, and is the No. 1 cause of stroke.

MYTH: My doctor checks my blood pressure so I don't have to do it at home.

FACT: Blood pressure can fluctuate so home monitoring can help your doctors determine whether you really have it and, if you do, whether your treatment plan is working.

MYTH: People with high blood pressure have symptoms such as nervousness, sweating, difficulty sleeping and facial flushing. If I don't have symptoms I don't have high blood pressure.

FACT: High blood pressure is often called 'the silent killer' because it has no symptoms, so patients may not be aware that it is damaging arteries, heart and other organs.

Sources: American Heart Association; Mayo Clinic; WSJ reporting

High Blood Pressure Overview

Risk Factors

During the last decade, the number of Americans with high blood pressure has increased by 30%. Over 65 million American adults now have high blood pressure, and this condition affects close to 1 billion people worldwide. Less than half of these people are on medication, however, and only about half of this group have their blood pressure under good control with such drugs. Older people are less likely to be treated adequately. The majority of people with high blood pressure have the mild type, but even this condition requires attention.

Age and Gender

Age is the major risk factor of hypertension. Blood pressure increases with age in both men and women, and in fact, the lifetime risk for hypertension is nearly 90%. Two-thirds of Americans over age 60 have hypertension. Older women (60 years and above) currently have the highest rates of hypertension, and mortality rates from hypertension are higher in women than in men. Hypertension is also becoming more common in children and teenagers.

Ethnicity

Compared to Caucasians, African Americans have 1.8 times the rate of fatal stroke, 1.5 times the risk for fatal heart disease, and 4.2 times the rates of end-stage kidney disease. In general, about 34% of African American men and women have hypertension; it may account for over 40% of all deaths in this group.

The prevalence of high blood pressure among African Americans is among the highest in the world. The rates of hypertension in Hispanic Americans, Caucasians, and Native Americans are about equivalent (ranging from 24 - 27%). The rate is much lower in Asian/ Pacific Islanders (9.7% in men and 8.4% in women). However, nearly 75% of older Japanese American men are hypertensive.

A number of theories have addressed the reasons for this difference:

- African Americans may have lower levels of nitric oxide and higher levels of a peptide called endothelin-1 (ET-1) than Caucasians. Nitric oxide keeps blood vessels flexible and open and ET-1 narrows blood vessels.

- African Americans have a higher risk for an impaired response to angiotensin (Ang II), which is a peptide important in regulating salt and water balances. African Americans are more likely to be salt-sensitive than other groups.

- Social and income disparities and dietary issues may explain many of the differences in blood pressure rates observed between ethnic groups. For example, while African Americans have a disproportionately high rate of hypertension, one study in rural African villages, where diets are rich in fish, reported only a 3% rate of high blood pressure among inhabitants. Another study reported that Caucasian as well as African Americans in the Southeast have a higher incidence of hypertension and stroke than people in other U.S. regions. The Southeast also has a higher rate of obesity, stress, anxiety, and depression, and diets low in potassium and high in salt, all related to a lower socioeconomic level.

- African Americans have a higher prevalence of risk factors (cardiovascular disease, obesity, diabetes and kidney disease) that are associated with hypertension.

Weight

Obesity. About one-third of patients with high blood pressure are overweight. Even moderately obese adults have double the risk of hypertension than people with normal weights. Moreover, the increase in blood pressure in aging Americans may be due primarily to weight gain. (In other cultures old age does not necessarily coincide with weight gain or high blood pressure.) Children and adolescents who are obese are at greater risk for high blood pressure when they reach adulthood.

Thinness. Interestingly, thin people with hypertension are at higher risk for heart attacks and stroke than obese people with high blood pressure. Experts think that thin people with hypertension are likely to have conditions such as an enlarged heart or stiff arteries that cause the blood pressure to rise and also pose greater dangers to health.

Low Birth Weight. Low birth weight, particularly in girls, has been associated with high blood pressure in both childhood and adulthood. One study suggested that breast-feeding these babies may help reduce this risk. Another study reported high levels of stress hormones in babies with low birth weight, which could increase the risk for high blood pressure later on. Low birth weight is also associated with subsequent obesity, a major contributor to hypertension.

Diabetes

Up to 75% of cardiovascular problems in people with diabetes may be due to hypertension. There are strong biologic links between insulin resistance (with or without diabetes) and hypertension. It is unclear which condition causes the other. Some experts believe angiotensin may be the common factor linking diabetes and high blood pressure. This natural chemical not only influences all aspects of blood pressure control but also interferes with insulin's normal metabolic signaling. People with diabetes or chronic kidney disease need to reduce their blood pressure to 130/80 mm Hg or lower to protect the heart and help prevent other complications common to both diseases. Lowering systolic pressure may be particularly important for people with diabetes.

Effects of Family

Spouses. Studies suggest that spouses of people with high blood pressure are at a much higher risk as well. Such findings indicate that dietary and environmental factors play a role in this disease. Some evidence also indicates that higher risk in spouses may be due to people often choosing mates who are similar to them.

Family History and Genetics. Essential hypertension may be inherited in 30 - 60% of cases. According to one study, being a brother or sister of someone with premature coronary artery disease is a greater risk factor for hypertension than having a parent with the disease. A family history of heart disease is considered to be a major risk factor for high blood pressure in adults under age 65.

Atherosclerosis is a common disorder of the arteries. Fat, cholesterol, and other substances collect in the walls of arteries. Larger accumulations are called atheromas or plaque and can damage artery walls and block blood flow. Severely restricted blood flow in the heart muscle leads to symptoms such as chest pain.

Emotional Factors

People who are anxious or depressed may have over twice the risk for high blood pressure than those without these problems.

Mental Stress. Recent evidence confirms the association between stress and hypertension. In one 20-year study, men who periodically measured highest on the stress scale were twice as likely to have high blood pressure as those with normal stress. The effects of stress on blood pressure in women were less clear. Job stress and lack of career success have been specifically linked to high blood pressure in both men and women.

Anxiety. Studies suggest that anxiety is a risk factor for hypertension, particularly in women.

Depression. Mounting evidence suggests that depression has physiological effects that impair the heart and that it contributes to destructive behaviors, such as weight gain, smoking, or alcohol abuse. In one study, those who scored highest on a depression test had about twice the risk of high blood pressure as those with the lowest score. This link was particularly strong in African Americans. Depression was the strongest risk factor in this group.

Time and Seasonal Factors

Blood pressure levels tend to be lowest during the morning and midday hours and highest at the end of the day. Seasonal changes also affect blood pressure, with hypertension increasing during cold months and declining during the summer. Blood pressure readings can vary by as much as 40% depending on the time of day and season.

Practical Blood Pressure Advice, Too Often Shelved for Convenience

By Eric Sabo : NY Times Article : January 23, 2008

It tastes bland and can be a tough daily regimen to follow, so it’s not the ideal medicine for high blood pressure. But a low-salt, heart-healthy diet is staging a comeback as some 60-plus drugs fail to rein in staggering rates of hypertension in the United States.

Even the Food and Drug Administration is weighing in, with recent deliberations on whether salt contents should be posted clearly on food labels. After years of acrimonious debate on the true dangers of sodium, anti-salt crusaders contend that the writing is on the wall. “The evidence is overwhelming,” said Dr. J. James Rohack, a Texas cardiologist who is working with the American Medical Association to rid the nation of its high-salt habits.

One plan of attack: calling on food companies and restaurants to cut the salt they serve by half over the next 10 years. The move could eventually end one of the major obstacles in fighting hypertension, the self-control and vigilance required when it comes to eating prepared or packaged foods. “People wouldn’t have to make a conscious decision,” said Dr. Lawrence J. Appel, a heart nutrition expert at Johns Hopkins University. “It could really make a difference.”

As many as half of the 70 million people in the United States with hypertension turn out to be sensitive to salt, versus 10 percent of Americans in general. Even so, only 22 percent of patients stick with a hypertension-taming, low-salt DASH diet rich in fruits, vegetables and low-fat dairy. That’s down from 30 percent in 1994. “We’re going in the wrong direction,” said Dr. Phillip Mellen of the Hattiesburg Health Clinic in Mississippi, who has studied nutritional aspects of high blood pressure.

Yet in knocking out one dietary demon, a much larger piece of the lifestyle puzzle still needs to be addressed. Rising rates of obesity, diets shockingly low in fruits and vegetables, and a lack of exercise are all major reasons one in three Americans now suffers from hypertension, experts say.

The sobering results come as pharmaceutical companies appear stalled in creating demonstrably superior new drugs to treat high blood pressure. Despite an expanding range of options, including Tekturna, the only novel hypertension treatment in nearly a decade, hypertension rates remain stubbornly high. For many patients, older, cheaper diuretics may work just as well as, or even better than, more heavily advertised treatments like calcium channel blockers or ACE inhibitors. And the most effective diuretic may be the first one made available, back in 1957.

Lacking a slam-dunk pill, the majority of patients end up relying on two or three drugs to keep their blood pressure under control. That state of affairs, some doctors say, could be better managed with the addition of diet and exercise. “We don’t have to worry about side effects from lifestyle changes,” said Dr. David C. Goff Jr., professor of epidemiology and public health at Wake Forest University School of Medicine in Winston-Salem, N.C. “But everyone finds it easier to prescribe drugs.”

The benefits of a proper diet are hardly a secret, even among those with traditionally less access to health care. One survey found that Latinos and African-Americans living in inner-city neighborhoods knew the dangers of eating poorly, but they also told researchers that restrictive diets are too hard to follow and insufficient to end the need for drugs. Years of bad eating may be impossible to undo. “Most people need to be on two drugs by the time we see them,” Dr. Appel said.

That’s a shame, because many patients might end at least some of their reliance on medications simply by eating better. The American Medical Association says that limiting sodium to 1,600 milligrams a day — about a teaspoon of salt — can prevent a five-point rise in systolic blood pressure. When combined with the right diet, cutting back on salt can lower blood pressure as well as any single hypertension pill, research shows. Adding protein and healthy monosaturated fats to the DASH diet may lead to even greater reductions in heart attack risk.

The joint national committee on high blood pressure, a government advisory panel, calls such dietary measures indispensable for treating hypertension, since they can lower blood pressure and improve the effectiveness of drugs. Lifestyle changes work best in combination, the group adds.

But until government regulations address the sodium slipped into processed and restaurant foods, experts say, many patients are going to find cutting back a tough battle to win. “Even when people are trying to be good, the deck is stacked against them,” Dr. Rohack said.

Many Possible Routes to the Goal of 120/80

These are the main categories of medications now used to reduce elevated blood pressure. Two or more types of drugs are typically used in combination to achieve an optimal pressure of 120/80 or less.

Diuretics

These first-line treatments for hypertension wash extra salt or sodium out of the body and allow blood vessels to dilate, which reduces blood pressure. An example would be hydrochlorothiazide (HCTZ)

ACE inhibitors

Drugs like isinopril and enalapril act by preventing the production of the chemical acetylcholine esterase, which causes blood vessels to constrict.

ARBs

Also known by their full name, angiotensin receptor blockers, these drugs affect the same chemical as ACE inhibitors but at a different location. They include Diovan, Benicar and Avapro.

Calcium channel blockers

Drugs like Norvasc (amlodipine), Procardia (nifedipine), DynaCirc (isradipine) and Cardizem (diltazem) help dilate blood vessels by preventing calcium from entering blood vessel walls or heart muscle.

Beta blockers

Lopressor or Toprol XL (metoprolol) and Tenormin (atenolol) reduce the effects of adrenaline. They reduce the work of the heart by slowing the heart rate and reducing its force when it contracts, thus lowering blood pressure.

Keeping Blood Pressure in Check

By Jane E. Brody : NT Times : January 28, 2013

Since the start of the 21st century, Americans have made great progress in controlling high blood pressure, though it remains a leading cause of heart attacks, strokes, congestive heart failure and kidney disease.

Now 48 percent of the more than 76 million adults with hypertension have it under control, up from 29 percent in 2000.

But that means more than half, including many receiving treatment, have blood pressure that remains too high to be healthy. (A normal blood pressure is lower than 120 over 80.) With a plethora of drugs available to normalize blood pressure, why are so many people still at increased risk of disease, disability and premature death? Hypertension experts offer a few common, and correctable, reasons:

¶ About 20 percent of affected adults don't know they have high blood pressure, perhaps because they never or rarely see a doctor who checks their pressure.

¶ Of the 80 percent who are aware of their condition, some don't appreciate how serious it can be and fail to get treated, even when their doctors say they should.

¶ Some who have been treated develop bothersome side effects, causing them to abandon therapy or to use it haphazardly.

¶ Many others do little to change lifestyle factors, like obesity, lack of exercise and a high-salt diet, that can make hypertension harder to control.

Dr. Samuel J. Mann, a hypertension specialist and professor of clinical medicine at Weill-Cornell Medical College, adds another factor that may be the most important. Of the 71 percent of people with hypertension who are currently being treated, too many are taking the wrong drugs or the wrong dosages of the right ones.

Dr. Mann, author of "Hypertension and You: Old Drugs, New Drugs, and the Right Drugs for Your High Blood Pressure," says that doctors should take into account the underlying causes of each patient's blood pressure problem and the side effects that may prompt patients to abandon therapy. He has found that when treatment is tailored to the individual, nearly all cases of high blood pressure can be brought and kept under control with available drugs.

Plus, he said in an interview, it can be done with minimal, if any, side effects and at a reasonable cost.

"For most people, no new drugs need to be developed," Dr. Mann said. "What we need, in terms of medication, is already out there. We just need to use it better."

But many doctors who are generalists do not understand the "intricacies and nuances" of the dozens of available medications to determine which is appropriate to a certain patient.

"Prescribing the same medication to patient after patient just does not cut it," Dr. Mann wrote in his book.

The trick to prescribing the best treatment for each patient is to first determine which of three mechanisms, or combination of mechanisms, is responsible for a patient's hypertension, he said.

¶ Salt-sensitive hypertension, more common in older people and African-Americans, responds well to diuretics and calcium channel blockers.

¶ Hypertension driven by the kidney hormone renin responds best to ACE inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers, as well as direct renin inhibitors and beta-blockers.

¶ Neurogenic hypertension is a product of the sympathetic nervous system and is best treated with beta-blockers, alpha-blockers and drugs like clonidine.

According to Dr. Mann, neurogenic hypertension results from repressed emotions. He has found that many patients with it suffered trauma early in life or abuse. They seem calm and content on the surface but continually suppress their distress, he said.

One of Dr. Mann's patients had had high blood pressure since her late 20s that remained well-controlled by the three drugs her family doctor prescribed. Then in her 40s, periodic checks showed it was often too high. When taking more of the prescribed medication did not result in lasting control, she sought Dr. Mann's help.

After a thorough work-up, he said she had a textbook case of neurogenic hypertension, was taking too much medication and needed different drugs. Her condition soon became far better managed, with side effects she could easily tolerate, and she no longer feared she would die young of a heart attack or stroke.

But most patients should not have to consult a specialist. They can be well-treated by an internist or family physician who approaches the condition systematically, Dr. Mann said. Patients should be started on low doses of one or more drugs, including a diuretic; the dosage or number of drugs can be slowly increased as needed to achieve a normal pressure.

Specialists, he said, are most useful for treating the 10 percent to 15 percent of patients with so-called resistant hypertension that remains uncontrolled despite treatment with three drugs, including a diuretic, and for those whose treatment is effective but causing distressing side effects.

Hypertension sometimes fails to respond to routine care, he noted, because it results from an underlying medical problem that needs to be addressed.

"Some patients are on a lot of blood pressure drugs - four or five - who probably don't need so many, and if they do, the question is why," Dr. Mann said.

Doctors urged to curb reliance on beta-blockers

Research favors other drugs to control hypertension

By Stephen Smith : Boston Globe | August 7, 2007

Doctors should stop routinely using beta-blockers to control high blood pressure, said researchers who reviewed dozens of previously published studies and found that other hypertension pills work better and cause fewer side effects.

For decades, beta-blockers and diuretics, also known as water pills, constituted the cornerstone of treatment for the 50 million Americans with high blood pressure. But a growing body of medical evidence shows that diuretics and newer blood-pressure medications are superior to beta-blockers at reducing high blood pressure, which can lead to heart attacks and strokes, said researchers whose report appeared yesterday in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

"We in medicine like to say that we practice evidence-based medicine," said Dr. Franz H. Messerli, an author of the study and a cardiologist at St. Luke's-Roosevelt Hospital in New York. "What's the evidence here" for continued use of beta-blockers to treat hypertension, Messerli asked. "Zero. To my way of thinking, this is pretty alarming."

Heart specialists not involved with the study predicted that it is likely to accelerate a shift in hypertension treatment from beta-blockers, which can cause side effects such as fatigue and sexual dysfunction.

Still, those doctors as well as the authors of the study emphasized that there is strong evidence to support prescribing beta-blockers for patients who have suffered a heart attack or those with a progressive weakening condition called heart failure.

Data from IMS Health, a healthcare information company, show that from January through June of this year, more than 75 million prescriptions were written for various beta-blockers, widely available in generic form. The statistics do not indicate which conditions the doctors were treating.

European medical societies have already begun urging physicians to abandon beta-blockers as a high blood-pressure medication, specialists said.

"I think this paper is going to be fairly influential, although I think the trend had already started before this of moving away from beta-blockers as a first-line treatment of hypertension," said Dr. Joseph Carrozza, chief of interventional cardiology at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. "The side effects are probably the worst" of any medication used to treat high blood pressure, he said.

Cardiologists said there is no clear culprit for the heavy use of beta-blockers. Early research suggested that the drugs had promise in treating high blood pressure, though they were often used with diuretics, which turned out to provide much of the benefit.

Also, beta-blockers have been around for decades and in recent years, their patents had expired, so they were relatively inexpensive, doctors said.

"This is just another example of why we need to do continuing follow-up research on classes of medicine," said Alan Goldhammer, deputy vice president for regulatory affairs at PhRMA, a leading pharmaceutical industry association.

One possible limitation in the new research: It was based on previous studies that looked at older beta-blockers, rather than some recently introduced formulations.

Still, Dr. Ilke Sipahi, a cardiologist at the Cleveland Clinic, said "until further data comes out, I think it's prudent not to use beta-blockers as a first-line treatment of high blood pressure."

The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute had already planned to convene specialists this fall to draft sweeping guidelines directing physicians toward the best treatments for their patients with cardiovascular ailments.

Dr. Lawrence J. Fine, acting chief of the national agency's Clinical Applications and Prevention Branch, said the new study will be factored into those recommendations. "Clearly, these authors have raised issues that new assessments of guidelines will have to consider seriously," Fine said.

In patients with high blood pressure, once-flexible blood vessels have turned rigid, meaning more pressure is needed to propel blood through veins and arteries.

To treat the condition, doctors use four major classes of high blood pressure pills: beta-blockers, diuretics, calcium-channel blockers, and ACE inhibitors.

Beta-blockers, sold under trade names such as Lopressor and Tenormin, work by blocking the effect of the hormone adrenaline on the heart. As a result, the heart slows down and does not have to work as hard. That's especially useful in the treatment of patients who have suffered heart attacks and those whose hearts chronically malfunction.

While beta-blockers reduce blood pressure, the other drugs do so more effectively and with fewer complications, the authors of yesterday's study said.

For example, the researchers cite an earlier analysis of 10 medical studies involving elderly patients with high blood pressure. About two-thirds of the patients taking diuretics had their blood pressure controlled, compared with less than one-third of the patients on beta-blockers.

Diuretics, among the most affordable drugs patients can take, reduce blood pressure by helping the body excrete excess water and sodium. They are widely regarded as the preferred first-line treatment for blood pressure patients, because of their low cost and mild side effects.

The later-generation drugs -- calcium-channel blockers and ACE inhibitors -- relax blood vessel walls, allowing blood to flow more smoothly.

While high blood pressure patients taking beta-blockers have a reduced risk of stroke of 16 percent to 22 percent compared with a placebo, the other hypertension drugs reduce that risk by an average of 38 percent.

Conversely, beta-blockers are powerfully beneficial for patients who have suffered heart attacks, substantially reducing the chances that they will soon die.

Beta-blockers also may work well for patients whose high blood pressure is not controlled by the other medications. Patients should not stop taking blood pressure drugs without first talking to their doctor. "We have the luxury now of a lot of drugs, and we can use the different ones for different situations," said Dr. Aram V. Chobanian, former dean of the Boston University School of Medicine. "The more we find out about these individual drugs, the more we will know about what specific patient populations they should be used in."

Drug-Resistant High Blood Pressure on the Rise

By Brenda Goodman : NY Times Article : June 24, 2008

High blood pressure, the most commonly diagnosed condition in the United States, is becoming increasingly resistant to drugs that lower it, according to a panel of experts assembled by the American Heart Association.

“It’s becoming more difficult to treat and it’s requiring more and more medications to do so,” said the panel chairman, Dr. David A. Calhoun, a hypertension specialist at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

The problem is not that the medications have stopped working, said the report, published this month in the journal Hypertension. Instead, many blood-pressure patients are sicker to begin with and require more drugs, at greater dosages, to manage their conditions.

The doctors say this is especially worrisome because recent surveys estimate that one in three Americans have hypertension, an underlying cause of heart attacks, strokes, kidney disease and heart failure.

Starting at a blood pressure of 115/80, research shows that the risk of a heart attack or stroke doubles with every 20-point increase of systolic pressure, the top number, or 10-point increase of diastolic pressure, the bottom number.

“High blood pressure is currently the biggest single contributor to death around the world because it is so common,” said Dr. Neil R. Poulter of the International Center for Circulatory Health at Imperial College London. In the United States, it is particularly common among blacks, with 41 percent found to have it in a 2005 study, compared with 27 percent of whites.

Resistant hypertension is defined as blood pressure that remains above clinical goals, even after a patient has been put on three or more different classes of medications. Additionally, patients whose blood pressure can be lowered to normal on four or more drugs should be considered resistant and should be closely monitored, the panel said.

After reviewing the available research on drug-resistant hypertension, a phenomenon first described in the 1970s, the panel found that it became more likely with advanced age, weight gain, a diet high in sodium, sleep apnea or chronic kidney disease.

Living in the Southeast, a region long recognized as the “stroke belt” of the United States, is also a risk factor for blacks and whites, though researchers are not sure why. An author of the new paper, Dr. William C. Cushman, chief of preventive medicine at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Memphis, said he suspected factors like inactivity, obesity and diets high in salt and fat.

Pat J. Dixon, 58, a nurse in Atlanta, takes five medications to lower her blood pressure. In many ways, Ms. Dixon is typical of a patient who develops resistant hypertension. At 5 feet and 172 pounds, she is obese, and her weight gain has caused mild Type 2 diabetes, for which she takes yet another drug. The diabetes is an extra strain on the kidneys, in turn worsening her blood pressure.

Ms. Dixon said that she did not use much salt when she cooked but that she did like to snack on potato chips.

“My doctor tells me about every week that I’m going to eat myself to death,” she said. “You do kind of get worn out and depressed every morning that you have to take five or six pills.”

The new report is one of the first to help doctors recognize and manage this growing group of difficult cases. Because so few studies have focused on resistance, the authors say, the number of drug-resistant patients is unclear.

By reviewing studies of patients with at least some hypertension, the panel estimated that 20 to 30 percent could not control their blood pressure with three or more drugs, even when taking them exactly as prescribed. The 20 to 30 percent cohort appears to be growing. A large study in 2006 from Stanford found that the number of blood-pressure patients who were prescribed three or more drugs had increased over 12 years, to 24 percent from 14 percent.

If patients need that many drugs, experts say, they are likely to be at greater risk for illness even if they lower their blood pressure to normal. These patients have usually had high blood pressure for some time and, as a result, have more organ damage.

“It’s a critically important issue,” said Dr. Sheldon Hirsch, chief of nephrology at Michael Reese Hospital in Chicago. “One of the biggest failings in medicine is that as we increasingly realize the importance of treating hypertension, that lower numbers are better than higher numbers, we have increasing trouble reaching those goals.”

The Evidence Gap The Minimal Impact of a Big Hypertension Study

By Andrew Pollack : NY Times Article : November 28, 2008

The surprising news made headlines in December 2002. Generic pills for high blood pressure, which had been in use since the 1950s and cost only pennies a day, worked better than newer drugs that were up to 20 times as expensive.

The findings, from one of the biggest clinical trials ever organized by the federal government, promised to save the nation billions of dollars in treating the tens of millions of Americans with hypertension — even if the conclusions did seem to threaten pharmaceutical giants like Pfizer that were making big money on blockbuster hypertension drugs.

Six years later, though, the use of the inexpensive pills, called diuretics, is far smaller than some of the trial’s organizers had hoped.

“It should have more than doubled,” said Dr. Curt D. Furberg, a public health sciences professor at Wake Forest University who was the first chairman of the steering committee for the study, which was known by the acronym Allhat. “The impact was disappointing.”

The percentage of hypertension patients receiving a diuretic rose to around 40 percent in the year after the Allhat results were announced, up from 30 to 35 percent beforehand, according to some studies. But use of diuretics has since stayed at that plateau. And over all, use of newer hypertension drugs has grown faster than the use of diuretics since 2002, according to Medco Health Solutions, a pharmacy benefits manager.

The Allhat experience is worth remembering now, as some policy experts and government officials call for more such studies to directly compare drugs or other treatments, as a way to stem runaway medical costs and improve care.

The aftereffects of the study show how hard it is to change medical practice, even after a government-sanctioned trial costing $130 million produced what appeared to be solid evidence.

A confluence of factors blunted Allhat’s impact. One was the simple difficulty of persuading doctors to change their habits. Another was scientific disagreement, as many academic medical experts criticized the trial’s design and the government’s interpretation of the results.

Moreover, pharmaceutical companies responded by heavily marketing their own expensive hypertension drugs and, in some cases, paying speakers to publicly interpret the Allhat results in ways that made their products look better.

“The pharmaceutical industry ganged up and attacked, discredited the findings,” Dr. Furberg said. He eventually resigned in frustration as chairman of the study’s steering committee, the expert group that continues to oversee analysis of data from the trial. One member of that committee received more than $200,000 from Pfizer, largely in speaking fees, the year after the Allhat results were released.

There was another factor: medicine moves on. Even before Allhat was finished, and certainly since then, new drugs appeared. Others, meanwhile, became available as generics, reducing the cost advantage of the diuretics. And many doctors have shifted to using two or more drugs together, helped by pharmaceutical companies that offer combination pills containing two medicines.

So Allhat’s main query — which drug to use first — became “an outdated question that doesn’t have huge relevance to the majority of people’s clinical practices,” said Dr. John M. Flack, the chairman of medicine at Wayne State University, who was not involved in the study and has consulted for some drug makers.

Dr. Sean Tunis, a former chief medical officer for Medicare, remains an advocate for comparative-effectiveness studies. But, as Allhat showed, “they are hard to do, expensive to do and provoke a lot of political pushback,” said Dr. Tunis, who now runs the nonprofit Center for Medical Technology Policy, which tries to arrange such trials.

“There’s a lot of magical thinking,” he said, “that it will all be science and won’t be politics.”

Expensive Pills

Promising better ways to treat high blood pressure, drug companies in the 1980s introduced a variety of medications, including ones known as calcium channel blockers and ACE inhibitors.

Although there was no real evidence the newer pills were better, diuretics fell to 27 percent of hypertension prescriptions in 1992, from 56 percent in 1982. Use of the more expensive pills added an estimated $3.1 billion to the nation’s medical bill over that period.

So the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, part of the federal National Institutes of Health, decided to compare the various drugs’ ability to prevent heart attacks, strokes and other cardiovascular problems. “This was a big-bucks issue,” said Dr. Jeffrey Cutler, the Heart, Lung and Blood Institute’s project director for the study.

Allhat — short for the Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial — began enrolling patients with high blood pressure, age 55 and older, in 1994, with more than 42,000 people eventually participating. Patients were randomly assigned one of four drugs: a diuretic called chlorthalidone; an ACE inhibitor called lisinopril, which AstraZeneca sold as Zestril; a calcium channel blocker, amlodipine, sold by Pfizer as Norvasc; and an alpha blocker, doxazosin, which Pfizer sold as Cardura.

Cardura was added only after Pfizer, which had already agreed to contribute $20 million to the trial’s costs, increased that to $40 million, Dr. Cutler said.

Early Trouble Signs

Pfizer’s bet on Cardura proved a big mistake. As the Allhat data came in, patients taking Cardura were nearly twice as likely as those receiving the diuretic to require hospitalization for heart failure, a condition in which the heart cannot pump blood adequately. Concerned, the Heart, Lung and Blood Institute announced in March 2000 that it had stopped the Cardura part of the trial.

What happened next provided the first signs that the Allhat evidence might not be universally embraced.

Rather than warn doctors that Cardura might not be suited for hypertension, Pfizer circulated a memo to its sales representatives suggesting scripted responses they could use to reassure doctors that Cardura was safe, according to documents released from a patients’ lawsuit against the company.

And in an e-mail message unearthed in those same court documents, a Pfizer sales executive boasted to colleagues that company employees had diverted some European doctors attending an American cardiology conference from hearing a presentation on the Allhat results and Cardura. “The good news,” the message said, “is that they were quite brilliant in sending their key physicians to sightsee rather than hear Curt Furberg slam Pfizer once again!”

Pfizer declined to comment on the messages.

The Food and Drug Administration waited a year before convening a meeting of outside experts to discuss Cardura’s safety. At that session, some of the experts sharply challenged the conclusions of the Allhat organizers. They argued that the heart failure cases might have been false readings and that an inadequate dose of Cardura had been used in the trial.

By the end of the daylong meeting, Dr. Robert J. Temple, a senior F.D.A. official, was clearly exasperated by the experts’ varying interpretations of a supposedly definitive trial.

“This is the largest and best attempt to compare outcomes we are ever going to see,” he said. “And people are extremely doubtful about whether it has shown anything at all.”

The committee decided that there was no need to issue an urgent warning to doctors and patients about Cardura.

Cardura sales held up in 2000. But the next year, worldwide sales fell to $552 million, from $795 million. Prescriptions for all alpha blockers fell 22 percent from 1999 to 2002 after having risen before then, according to one study.

Pfizer’s decision to stop promoting Cardura in late 2000, after the drug lost patent protection, was a factor in the decline. But Allhat clearly was, too.

Cost-Benefit Analysis

The main Allhat results were announced in December 2002 at a news conference in Washington and published in The Journal of the American Medical Association.

In the primary target outcome of the trial — the prevention of heart attacks — the three remaining drugs were proved equal. But patients receiving the Norvasc calcium channel blocker from Pfizer had a 38 percent greater incidence of heart failure than those on the diuretic. And those receiving the ACE inhibitor from AstraZeneca had a 15 percent higher risk of strokes and a 19 percent higher risk of heart failure.

Moreover, the diuretic cost only about $25 a year, compared with $250 for an ACE inhibitor and $500 for a calcium channel blocker. So the diuretic was declared the winner.

But some hypertension experts accused the government of overstating the case for the diuretics, as a way to cut medical spending.

“There was a feeling there was a political and economic agenda as much as a scientific agenda,” said Dr. Michael Weber, a professor of medicine at the Health Science Center at Brooklyn, part of the State University of New York, who had been an investigator in the study but afterward became one of its leading critics. “They pushed beyond what the data allowed them to say.”

Critics said the rules of the trial had favored the diuretics. If the first drug did not adequately lower blood pressure — as happened in more than 60 percent of cases — a second drug could be added. But that second drug was usually a type that worked better with diuretics than with ACE inhibitors.

There were also more new cases of diabetes among the patients who took diuretics, although experts argued over how meaningful that finding was.

Adding fuel to the debate, an Australian study released two months after Allhat found an ACE inhibitor superior to a diuretic. The proper lesson to draw from Allhat, some critics contended, was that what matters most is how much blood pressure is lowered, not which drug is used to do it. For these and other reasons, European hypertension experts discounted Allhat.

Allhat’s proponents discounted the Australian study as less authoritative, and they dismissed the other criticisms.

Still, the arguments “muddied the waters,” said Dr. Randall S. Stafford of Stanford, who studied the effect of Allhat on prescriptions. “The message,” he said, “was no longer as clear to physicians.”

Science Moves On

By the time the Allhat results were released, lisinopril, the ACE inhibitor, had become generic. That meant AstraZeneca and Merck, which sold a version of the compound as Prinivil, had less interest in defending their drugs.

Not so Pfizer. Norvasc was the best-selling hypertension treatment in the world, with sales of $3.8 billion in 2002, and Pfizer’s second-biggest drug behind the cholesterol medication Lipitor.

The company set out to accentuate the positive. In a news release after the Allhat results were announced, it said that Norvasc was found to be “comparable to the diuretic in fatal coronary heart disease, heart attacks and stroke.” And in a medical journal advertisement, it proclaimed “ALL HATs off” to its drug.

Neither the news release nor the ad, however, included the 38 percent greater risk of heart failure with Norvasc in the Allhat study.

Nor did Hank McKinnell, then Pfizer’s chief executive, mention heart failure in lauding the results during his quarterly earnings conference call with analysts a few weeks after the Allhat report was released. “Contrary to what you might have read in the press,” Mr. McKinnell said, “Allhat is extremely positive for Norvasc. It will be our job to explain that to the medical community.”

Dr. Paul K. Whelton, president of Loyola University Health System and the current chairman of the Allhat steering committee, said that Pfizer and other drug companies “took what was in their best interest and ran with those, and conveniently didn’t mention other things.”

Pfizer defends its actions. Dr. Michael Berelowitz, the head of Pfizer’s global medical organization, said that in the trial’s design, heart failure was merely one component of a broader measure of various cardiovascular problems. And in that broader measure, Dr. Berelowitz said, there was no difference between Norvasc and the diuretic. Also, he said, the label for Norvasc already contained a precaution about heart failure.

“Further action regarding the heart failure finding was therefore not considered necessary,” he said in a statement in response to questions.

Pfizer was not the only company promoting its drugs. The drug giant Novartis, for example, was spending heavily to market Diovan, a leader among a class of hypertension drugs called angiotensin receptor blockers, which were too new to have been included in Allhat. Diovan, which had more than $5 billion in sales last year, sells for $1.88 to $3.20 a pill on drugstore.com, compared with 8 to 31 cents for a diuretic.

No company, though, was spending money to promote generic diuretics. So the federal Heart, Lung and Blood Institute recruited Allhat investigators, provided them with training and sent them to proselytize fellow physicians. In all, 147 investigators gave nearly 1,700 talks and reached more than 18,000 doctors and other health care providers.

But it was a coffee-and-doughnuts operation compared with the sumptuous dinners that pharmaceutical companies used to market to doctors. Moreover, the steering committee’s outreach program did not get under way until about three years after the results were published.

Dr. Stafford of Stanford said the outreach seemed to have had a slight effect on increasing the use of diuretics.

The results of Pfizer’s efforts are easier to quantify. Norvasc sales continued to grow to $4.9 billion in 2006, falling only after the drug lost patent protection in the United States in 2007.

Tangles and Strife

Tensions about industry influence reached even the study’s own steering committee. Dr. Furberg, the chairman, bluntly accused some members of the committee of being agents of the industry.

One member, Dr. Richard H. Grimm Jr. of the University of Minnesota, had been receiving tens of thousands of dollars a year from Pfizer since at least 1997, according to reports that pharmaceutical companies file in that state.

In 2003, the year after the Allhat results were published, Dr. Grimm’s payments from Pfizer soared to more than $200,000 — an increase that The New York Times reported in 2007.

Dr. Grimm said in a recent interview that about half those fees in 2003 came from giving about 100 Pfizer-sponsored talks to doctors about Allhat. Dr. Grimm said he gave mainly the standard Allhat-sanctioned talk. But instead of saying diuretics were outright better than the other drugs, he said they were as good or better.

Meanwhile, Dr. Grimm had led an effort to remove Dr. Furberg from his position on the grounds that he had not been impartial.

“He had a vendetta against the calcium channel blockers,” Dr. Grimm said. Dr. Furberg had been publicly questioning the safety of those drugs based on some studies he did in the 1990s. The effort to oust Dr. Furberg failed in 2001. But in August 2004, Dr. Furberg resigned as chairman, contending that there had not been enough effort to disseminate the Allhat message.

Dr. Whelton, who took over as chairman, said that the study’s message was never compromised by industry ties on the steering committee.

“Curt is a wonderful guy who is a crusader,” said Dr. Whelton, who did not have industry ties and was not involved in the effort to unseat Dr. Furberg. “He has certainly rubbed a lot of people, even good friends, the wrong way.”

Changing Practice

Experts see several lessons to be learned from Allhat.

One is that “all trials have flaws” that leave the results open to interpretation, said Dr. Robert M. Califf, a cardiologist at Duke who served on the safety monitoring committee of Allhat.

Another is that providing doctors information is “necessary, but not sufficient” to urge them to change their practices, said Dr. Carolyn M. Clancy, director of the federal Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, which itself conducts studies comparing different medical treatments.

And while insurers can influence practice through reimbursement policies, they did not seem to have pushed strongly for diuretics after Allhat, in part because some of the other drugs had become generic.

Even the cost-conscious medical system at the Department of Veterans Affairs did not require diuretics, because too many doctors would probably have requested exceptions, said Dr. William C. Cushman, chief of preventive medicine at the department’s medical center in Memphis.

Dr. Cushman, a member of the Allhat steering committee, said diuretic use in the system was still “much lower” than he thought it should be.

Dr. Clancy said that her agency was now mainly using insurance records to judge how treatments perform. While clinical trials are the gold standard, she said, they are costly and time-consuming.

And, she added, “You might be answering a question that by the time you are done, no longer feels quite as relevant.”

Too Much Salt Takes a Blood-Pressure Toll

By Jane E. Brody : NY Times Article : September 22, 2009

Perhaps nothing in medicine more aptly depicts the paradoxical statement “doing better, feeling worse” than high blood pressure. Despite an extraordinarily easy way to detect it, strong evidence for how to prevent it and proven remedies to treat it, more Americans today have undetected or poorly controlled hypertension than ever before.

The aging of the population is a reason but not the only one, said Dr. Aram V. Chobanian, a hypertension expert at Boston University Medical Center. As he summarized the problem in an interview and in The New England Journal of Medicine in August, Americans are too sedentary and fat. They eat too much, especially salt, but too few potassium-rich fruits and vegetables.

The makers of processed and fast foods created and persistently promote a craving for high-salt foods, even in school lunch programs. And Americans without health insurance often don’t know that their blood pressure is too high because they wait for a calamity to strike before seeking medical care.

Solutions to the blood pressure problem require broad-scale approaches — by the public, by government, by industry and by health care professionals. Several measures are similar to those that have been so effective in curbing cigarette smoking; others require better, affordable access to medical care for everyone at risk, including children and the unemployed. Still others need the cooperation of government, industry and the public to improve the American diet and enhance opportunities for health-promoting exercise.

No one claims that the solutions are cheap. But failure to fix this problem portends even greater costs down the line, because uncontrolled hypertension sets the stage for astronomically expensive heart and kidney disease and stroke — diseases that will become only more common as the population ages.

Doing the Numbers

Once, the prevailing medical opinion was that lowering an elevated blood pressure was hazardous because it would deprive a person’s vital organs of an adequate blood supply. But a few pioneering medical researchers thought otherwise and eventually showed that lowering high blood pressure could prevent heart attacks, heart failure, strokes and kidney disease — and save lives.

Even then, it was long thought that the only important indicator was diastolic pressure — the bottom number, representing the pressure in arteries between heartbeats. Further studies showed that the larger top number, systolic pressure, representing arterial pressure when the heart beats, was also medically important.

And as the various studies reached fruition, it became apparent that the long-accepted numbers for desirable blood pressure were too high to protect long-term health.

Now the upper limit of normal blood pressure is listed as 120 over 80; anyone with a pressure of 140 over 90 or higher is considered hypertensive. Those with pressures in between are considered prehypertensive and should take steps to bring blood pressure down or, at least, prevent it from rising more.

The change mirrors what happened with serum cholesterol, for which “normal” was once listed as 240 milligrams per deciliter of blood and is now less than 200 to prevent heart disease caused by clogged arteries.

It was also long thought that blood pressure naturally rises with age. Indeed, the Framingham Heart Study showed that when 65-year-old people whose blood pressure was below 140 over 90 were followed for 20 years, about 90 percent of them became hypertensive because their arteries narrowed and stiffened with age, causing blood to push harder against artery walls.

But in many societies where obesity is rare, activity levels are high and salt intake is low, blood pressure remains low throughout life. This is the best clue we have for the lifestyle changes needed to prevent illness and premature death caused by hypertension.

Dr. Claude Lenfant, who served as director of the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, is now 81 and has a blood pressure of 115 over 60, a level rarely found among older Americans not taking medication for hypertension. His secret: a normal body weight, four or more miles of walking daily, and no salt used to prepare his meals, most of which are made from scratch at home.

In an interview, Dr. Lenfant, who now lives in Vancouver, Wash., said the problem of hypertension was rising all around the world and added that by 2020 the number of people with uncontrolled hypertension was projected to rise 65 percent. One reason is that doctors today are more likely to diagnose the problem, so it is reported more often in population surveys. “But I’m much more concerned about the fact that so much high blood pressure is not controlled,” he said, and called “therapeutic inertia” an important reason.

It is not enough for doctors to write a prescription and tell patients to return for a check-up in six months, he said. Rather, a working partnership between health care professionals and patients is needed to encourage people to monitor their pressure, adopt protective habits and continue to take medication that effectively lowers pressure.

Treatment and Prevention

Diuretics are a first-line and inexpensive remedy, but many patients with hypertension also need other drugs to lower pressures to a desirable level.

Dr. Chobanian, whose New England Journal report was titled “The Hypertension Paradox: More Uncontrolled Disease Despite Improved Therapy,” noted that “in the majority of patients, two or more antihypertensive drugs are required to achieve target blood-pressure levels.” In the interview, he emphasized the detrimental role played by diets high in salt and calories and low in protective fruits and vegetables — a result of portions that are too large, and of too many fast and processed foods that rely on salt to enhance flavor. “Generally, the average person in our society consumes more than 10 grams of salt a day,” Dr. Chobanian said, “but the Institute of Medicine recommends a third of this amount as optimal.”

A new RAND Corporation study finds that a one-third reduction in salt consumption could save $18 billion a year in direct medical costs. Dr. Chobanian called for better food labeling; changes in foods served in cafeterias, restaurants and schools; and less advertising on children’s television of unhealthy foods high in fat, salt and sugar. Also needed are better opportunities for all people to get regular exercise. “We have to focus more on children,” he said. “They’re the ones who will be getting cardiovascular diseases in the future.”

Getting the Right Hypertension Drug

By Gautam Naik : WSJ : August 24, 2010

Roughly half the 50 million Americans who suffer from hypertension don't succeed in keeping their blood pressure under control, often because they haven't been prescribed the drug that would work best for them. Now, three new studies are suggesting ways to help make sure patients get the right medications.

Five types of drugs are commonly used for treating hypertension, or high blood pressure, a major risk factor for heart attacks and stroke. Doctors often choose among the drugs by trial and error, prescribing several of them in turn to see which works best for a particular patient. Complicating matters: Most people need more than one drug to control high blood pressure, making it all the more difficult to ensure a patient is receiving the most effective treatment.

"Our current prescribing methods are very primitive. We haven't increased the success rate [in treating hypertension] in 35 years," says Michael Alderman, a blood-pressure expert at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York City, and a co-author of one of the new studies.

Doctors have known for decades that patients with different physical characteristics respond differently to various hypertension drugs. But little research has focused on matching specific pills to specific patients. The new studies, which appear in the latest issue of the American Journal of Hypertension, represent efforts to provide scientific guidance for doctors treating high blood pressure.

One of the studies, for example, shows that some drugs work better in certain ethnic groups than in others. Two other studies point to the importance of testing patients' levels of renin, a hormone produced by the kidneys, as a guide in prescribing blood-pressure medicine. Researchers in each of the studies emphasized that larger-scale trials would be necessary before the findings could become part of official treatment guidelines.

Hypertension is an unhealthy increase of blood pressure on the arteries. The pressure is governed by the body's intricate plumbing mechanism: The heart is the pump, the arteries are the pipes, and the kidneys are sewers that eliminate unwanted fluids. Blood pressure can go up either because there's too much fluid (salt and water) in the system, or because the arteries have narrowed. Blood pressure can rise with a diet that is high in salt.

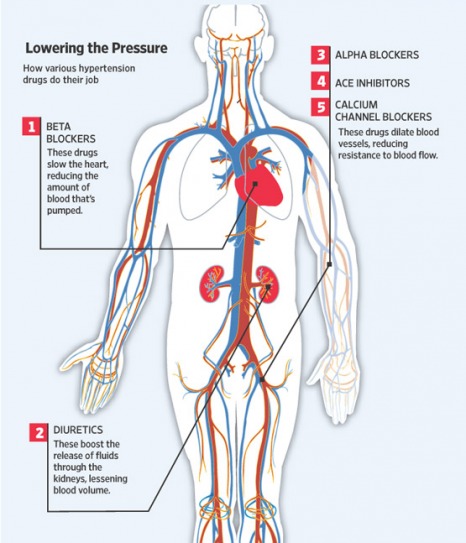

The most common therapies are diuretics, which are cheap, well-tested, and have been around for decades. These drugs boost the release of fluid through the kidneys. Another drug class, beta blockers, slow the heart and thus lower the amount of blood that's pumped. Ace inhibitors, alpha blockers and calcium channel blockers reduce pressure by dilating the blood vessels.

One of the studies, co-authored by Ajay Gupta of Imperial College London,looked at drug responses among 5,425 patients in various countries and across different ethnic groups. For example, in the U.K., south Asians are often given ace inhibitors as a first-line treatment, though the effectiveness of such prescriptions isn't based on any hard evidence. Dr. Gupta's study, for the first time, confirms that south Asians respond especially well to such drugs.

U.K. medical-treatment guidelines say that first-line drug therapies should be guided by a patient's age and race. (Guidelines in the U.S. don't include such suggestions.) Dr. Gupta and his colleagues showed that the same guidelines might also apply for second-line treatments. For example, if a black patient is given a calcium channel blocker or diuretic as the first drug, U.K. guidelines recommend adding an ace inhibitor.

But the study suggests that may not be the most effective route. Instead, if a calcium channel blocker is first prescribed, a diuretic should be the add-on drug. If a diuretic is first prescribed, a calcium channel blocker should be the second-line treatment.

The two other studies focused on the hormone renin. Medical experts say few doctors today measure a patient's renin level, despite a study in the 1970s that suggested it might be used as a biomarker for prescribing the drugs. Contradictory evidence that emerged later, and the cost and delay of testing for the hormone, helped keep renin-testing from catching on, medical experts say.

Nonetheless, one of the new studies, involving 363 patients, confirmed the 1970s finding, showing that measuring the renin level can be an effective method for selecting a blood-pressure medication. The research, by a team led by Stephen Turner of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., found that a patient with a higher renin level probably should not be treated with a diuretic. The patient would probably respond better to a drug, such as a beta blocker, that functions differently in the body.

The predictive effects of renin activity "were statistically independent of race, age and other characteristics," the team's paper concludes. It found that renin levels could also serve as a guide for prescribing add-on therapies for some patients.

The third study, by a team led by Dr. Alderman, found that when an anti-renin drug was used in certain patients with low renin levels, it had the undesirable effect of increasing blood pressure. The study involved 945 patients.

"These are not fundamentally novel biological discoveries," says Morris Brown, professor of clinical pharmacology at the University of Cambridge, U.K., who wasn't involved in the studies. But they constitute "a wake-up call that we should be using renin measurements as a systematic form of help" for prescribing hypertension drugs.

By Gautam Naik : WSJ : August 24, 2010

Roughly half the 50 million Americans who suffer from hypertension don't succeed in keeping their blood pressure under control, often because they haven't been prescribed the drug that would work best for them. Now, three new studies are suggesting ways to help make sure patients get the right medications.

Five types of drugs are commonly used for treating hypertension, or high blood pressure, a major risk factor for heart attacks and stroke. Doctors often choose among the drugs by trial and error, prescribing several of them in turn to see which works best for a particular patient. Complicating matters: Most people need more than one drug to control high blood pressure, making it all the more difficult to ensure a patient is receiving the most effective treatment.

"Our current prescribing methods are very primitive. We haven't increased the success rate [in treating hypertension] in 35 years," says Michael Alderman, a blood-pressure expert at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York City, and a co-author of one of the new studies.

Doctors have known for decades that patients with different physical characteristics respond differently to various hypertension drugs. But little research has focused on matching specific pills to specific patients. The new studies, which appear in the latest issue of the American Journal of Hypertension, represent efforts to provide scientific guidance for doctors treating high blood pressure.

One of the studies, for example, shows that some drugs work better in certain ethnic groups than in others. Two other studies point to the importance of testing patients' levels of renin, a hormone produced by the kidneys, as a guide in prescribing blood-pressure medicine. Researchers in each of the studies emphasized that larger-scale trials would be necessary before the findings could become part of official treatment guidelines.

Hypertension is an unhealthy increase of blood pressure on the arteries. The pressure is governed by the body's intricate plumbing mechanism: The heart is the pump, the arteries are the pipes, and the kidneys are sewers that eliminate unwanted fluids. Blood pressure can go up either because there's too much fluid (salt and water) in the system, or because the arteries have narrowed. Blood pressure can rise with a diet that is high in salt.

The most common therapies are diuretics, which are cheap, well-tested, and have been around for decades. These drugs boost the release of fluid through the kidneys. Another drug class, beta blockers, slow the heart and thus lower the amount of blood that's pumped. Ace inhibitors, alpha blockers and calcium channel blockers reduce pressure by dilating the blood vessels.

One of the studies, co-authored by Ajay Gupta of Imperial College London,looked at drug responses among 5,425 patients in various countries and across different ethnic groups. For example, in the U.K., south Asians are often given ace inhibitors as a first-line treatment, though the effectiveness of such prescriptions isn't based on any hard evidence. Dr. Gupta's study, for the first time, confirms that south Asians respond especially well to such drugs.

U.K. medical-treatment guidelines say that first-line drug therapies should be guided by a patient's age and race. (Guidelines in the U.S. don't include such suggestions.) Dr. Gupta and his colleagues showed that the same guidelines might also apply for second-line treatments. For example, if a black patient is given a calcium channel blocker or diuretic as the first drug, U.K. guidelines recommend adding an ace inhibitor.

But the study suggests that may not be the most effective route. Instead, if a calcium channel blocker is first prescribed, a diuretic should be the add-on drug. If a diuretic is first prescribed, a calcium channel blocker should be the second-line treatment.

The two other studies focused on the hormone renin. Medical experts say few doctors today measure a patient's renin level, despite a study in the 1970s that suggested it might be used as a biomarker for prescribing the drugs. Contradictory evidence that emerged later, and the cost and delay of testing for the hormone, helped keep renin-testing from catching on, medical experts say.

Nonetheless, one of the new studies, involving 363 patients, confirmed the 1970s finding, showing that measuring the renin level can be an effective method for selecting a blood-pressure medication. The research, by a team led by Stephen Turner of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., found that a patient with a higher renin level probably should not be treated with a diuretic. The patient would probably respond better to a drug, such as a beta blocker, that functions differently in the body.

The predictive effects of renin activity "were statistically independent of race, age and other characteristics," the team's paper concludes. It found that renin levels could also serve as a guide for prescribing add-on therapies for some patients.

The third study, by a team led by Dr. Alderman, found that when an anti-renin drug was used in certain patients with low renin levels, it had the undesirable effect of increasing blood pressure. The study involved 945 patients.

"These are not fundamentally novel biological discoveries," says Morris Brown, professor of clinical pharmacology at the University of Cambridge, U.K., who wasn't involved in the studies. But they constitute "a wake-up call that we should be using renin measurements as a systematic form of help" for prescribing hypertension drugs.

High Blood Pressure Overview

Hypertension is the term used to describe high blood pressure.

Blood pressure is a measurement of the force against the walls of your arteries as your heart pumps blood through your body.

Blood pressure readings are usually given as two numbers -- for example, 120 over 80 (written as 120/80 mmHg). One or both of these numbers can be too high.

The top number is called the systolic blood pressure, and the bottom number is called the diastolic blood pressure.

If you have heart or kidney problems, or if you had a stroke, your doctor may want your blood pressure to be even lower than that of people who do not have these conditions.

ALTERNATIVE NAMES

Hypertension; HBP; Blood pressure - high

CAUSES »

Many factors can affect blood pressure, including:

You have a higher risk of high blood pressure if you:

High blood pressure that is caused by another medical condition or medication is called secondary hypertension. Secondary hypertension may be due to:

SYMPTOMS »

Most of the time, there are no symptoms. For most patients, high blood pressure is found when they visit their health care provider or have it checked elsewhere.

Because there are no symptoms, people can develop heart disease and kidney problems without knowing they have high blood pressure.

If you have a severe headache, nausea or vomiting, bad headache, confusion, changes in your vision, or nosebleeds you may have a severe and dangerous form of high blood pressure called malignant hypertension.

EXAMS AND TESTS »

Your health care provider will check your blood pressure several times before diagnosing you with high blood pressure. It is normal for your blood pressure to be different depending on the time of day.

Blood pressure readings taken at home may be a better measure of your current blood pressure than those taken at your doctor's office. Make sure you get a good quality, well-fitting home device. It should have the proper sized cuff and a digital readout.

Practice with your health care provider or nurse to make sure you are taking your blood pressure correctly. See also: Blood pressure monitors for home

Your doctor will perform a physical exam to look for signs of heart disease, damage to the eyes, and other changes in your body.

Tests may be done to look for:

TREATMENT »

The goal of treatment is to reduce blood pressure so that you have a lower risk of complications. You and your health care provider should set a blood pressure goal for you.

If you have pre-hypertension, your health care provider will recommend lifestyle changes to bring your blood pressure down to a normal range. Medicines are rarely used for pre-hypertension.

You can do many things to help control your blood pressure, including:

There are many different medicines that can be used to treat high blood pressure. See: High blood pressure medicines

Often, a single blood pressure drug may not be enough to control your blood pressure, and you may need to take two or more drugs. It is very important that you take the medications prescribed to you. If you have side effects, your health care provider can substitute a different medication.

OUTLOOK (PROGNOSIS)

Most of the time, high blood pressure can be controlled with medicine and lifestyle changes.

POSSIBLE COMPLICATIONS

When blood pressure is not well controlled, you are at risk for:

WHEN TO CONTACT A MEDICAL PROFESSIONAL

If you have high blood pressure, you will have regular appointments with your doctor.

Even if you have not been diagnosed with high blood pressure, it is important to have your blood pressure checked during your yearly check-up, especially if someone in your family has or had high blood pressure.

Call your health care provider right away if home monitoring shows that your blood pressure is still high.

PREVENTION

Adults over 18 should have their blood pressure checked regularly.

Lifestyle changes may help control your blood pressure.

Follow your health care provider's recommendations to modify, treat, or control possible causes of high blood pressure.

Hypertension is the term used to describe high blood pressure.

Blood pressure is a measurement of the force against the walls of your arteries as your heart pumps blood through your body.