- RETIREMENT ANNOUNCEMENT

- HOME PAGE

- "MYCHART" the new patient portal

- BELMONT MEDICAL ASSOCIATES

- MOUNT AUBURN HOSPITAL

- EMERGENCIES

- PRACTICE PHILOSOPHY

- MY RESUME

- TELEMEDICINE CONSULTATION

- CONTACT ME

- LAB RESULTS

- ePRESCRIPTIONS

- eREFERRALS

- RECORD RELEASE

- MEDICAL SCRIBE

- PHYSICIAN ASSISTANT (PA)

- Medicare Annual Wellness Visit

- Case management/Social work

- Quality Care Measures

- Emergency closing notice

- FEEDBACK

- Talking to your doctor

- Choosing..... and losing a doctor

- INDEX A - Z

- ALLERGIC REACTIONS

- Alternative Medicine

- Alzheimer's Disease

- Bladder Problems

- Blood disorders

- Cancer Concerns

- GENETIC TESTING FOR HEREDITARY CANCER

- Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

- Controversial Concerns

- CPR : Learn and save a life

- CRP : Inflammatory marker

- Diabetes Management

- Dizziness, Vertigo,Tinnitus and Hearing Loss

- EXERCISE

- FEMALE HEALTH

-

GASTROINTESTINAL topics

- Appendicitis

- BRAT diet

- Celiac Disease or Sprue

- Crohn's Disease

- Gastroenterologists for Colon Cancer Screening

- Colonoscopy PREP

- Constipation

- Gluten sensitivity, but not celiac disease

- Heartburn and GERD

- Hemorrhoids and Anal fissure

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- NASH : Non Alcoholic Steato Hepatitis

- FEET PROBLEMS

- HEART RELATED topics

-

INFECTIOUS DISEASES

- Antibiotic Resistance

- Cat bites >

- Clostridia difficile infection - the "antibiotic associated germ"

- CORONA VIRUS

- Dengue Fever and Chikungunya Fever

- Food borne illnesses

- Shingles Vaccine

- Hepatitis B

- Hepatitis C

- Herpes

- Influenza

- Helicobacter pylori - the "ulcer germ"

- HIV Screening

- Lyme and other tick borne diseases

- Measles

- Meningitis

- MRSA (Staph infection)

- Norovirus

- Sexually Transmitted Diseases

- Shingles (Herpes Zoster)

- Sinusitis

- West Nile Virus

- Whooping Cough (Pertussis)

- Zika virus and pregnancy

- INSURANCE related topics

- KIDNEY STONES

- LEG CRAMPS

- LIBRARY for patients

- LIFE DECISIONS

- MALE HEALTH

- Medication/Drug side effects

- MEDICAL MARIJUANA

- MENTAL HEALTH

- Miscellaneous Articles

-

NUTRITION - EXERCISE - WEIGHT

- Cholesterol : New guidelines for treatment

- Advice to lower your cholesterol

- Cholesterol : Control

- Cholesterol : Raising your HDL Level

- Exercise

- Food : Making Smart Choices

- Food : Making Poor Choices

- Food : Grape Fruit and Drug Interaction

- Food : Vitamins, Minerals and Supplements

- Omega 3 fatty acids

- Vitamin B12 deficiency

- Vitamin D

- Weight Loss

- ORTHOPEDICS

- PAIN

- PATIENTS' RIGHTS

- SKIN

- SLEEP

- SMOKING

- STROKE

- THYROID

- SUBSTANCE ABUSE

- Travel and Vaccination

- TREMOR

- Warfarin Anticoagulation

- OTHER STUFF FOLLOWS

- Fact or Opinion?

- Hippocratic Oath

- FREE ADVICE.......for what its worth!

- LAUGHTER.....is the best medicine

- Physicians Pet Peeves

- PHOTO ALBUM - its not all work!

- Cape Town, South Africa

- Tribute page

- The 100 Club

- Free Wi-Fi

DEPRESSION SCREENING TEST

Depression and other related issues

If you, a family member or a friend is depressed, please read this article............................ Help is a phone call away............................

Everyone at one time or another has felt depressed, sad, or blue. Being depressed is a normal reaction to loss, life's struggles, or an injured self-esteem. But sometimes the feeling of sadness becomes intense, lasting for long periods of time and preventing a person from leading a normal life. This is depression, a mental illness that if left untreated, can worsen, lasting for years and causing untold suffering, and possibly even result in suicide. It is important to recognize the signs of depression and seek help if you or your loved one is exhibiting any of the following symptoms.

These are some of the signs and symptoms of depression that you should be aware of:

- Sadness

- Loss of energy

- Feelings of hopelessness or worthlessness

- Loss of enjoyment from things that were once pleasurable

- Difficulty concentrating

- Uncontrollable crying

- Difficulty making decisions

- Irritability

- Increased need for sleep

- Insomnia or excessive sleep

- Unexplained aches and pains

- Stomachache and digestive problems

- Decreased sex drive

- Sexual problems

- Headache

- A change in appetite causing weight loss or gain

- Thoughts of death or suicide

- Attempting suicide

Warning Signs of Suicide

If you or someone you know is demonstrating any of the following warning signs, contact a mental health professional right away or go to the emergency room for immediate treatment.

- Talking about suicide (killing one's self)

- Always talking or thinking about death

- Making comments about being hopeless, helpless, or worthless

- Saying things like "It would be better if I wasn't here" or "I want out"

- Depression (deep sadness, loss of interest, trouble sleeping and eating) that gets worse

- A sudden switch from being very sad to being very calm or appearing to be happy

- Having a "death wish," tempting fate by taking risks that could lead to death, like driving through red lights

- Losing interest in things one used to care about

- Visiting or calling people one cares about

- Putting affairs in order, tying up lose ends, changing a will

There are several different types of depression:

- Major depressive disorder

- Dysthymia

- Seasonal affective disorder

- Psychotic depression

- Bipolar depression

Major Depression

An individual with major depression, or major depressive disorder, feels a profound and constant sense of hopelessness and despair. Major depression is marked by a combination of symptoms that interfere with the ability to work, study, sleep, eat, and enjoy once pleasurable activities. Major depression may occur only once but more commonly occurs several times in a lifetime.

Who Experiences Major Depression?

In the U.S., approximately 10% of people suffer from major depression at any one time, and 20-25% suffers a major depressive episode, or event, at some point during their lifetimes. Most people associate depression with adults, but it also occurs in children and the elderly -- two populations in which it often goes undiagnosed and untreated. Approximately twice as many women as men suffer from major depression. This is partially because of hormonal changes throughout a woman's life: During menstruation, pregnancy, miscarriage and menopause. Other contributing factors include increased responsibilities in both professional and home lives -- balancing work while taking care of a household, raising a child alone, or even caring for an aging parent. However, depression in men may also be underreported.

Psychotic Depression

What is Psychotic Depression?

Roughly 25% of people who are admitted to the hospital for depression suffer from what's called psychotic depression. In addition to the symptoms of depression, psychotic depression includes some features of psychosis -- like hallucinations (seeing or hearing things that aren't really there) or delusions (irrational thoughts and fears).

How is Psychotic Depression Different Than Other Mental Illness?

While people with other mental illness, like schizophrenia, also experience these symptoms, those with psychotic depression are usually aware that these thoughts aren't true. They may be ashamed or embarrassed and try to hide them, sometimes making this type of depression difficult todiagnose.

What are the Symptoms of Psychotic Depression?

- Anxiety

- Agitation

- Paranoia

- Insomnia

- Physical immobility

- Constipation

- Intellectual impairment

- Psychosis

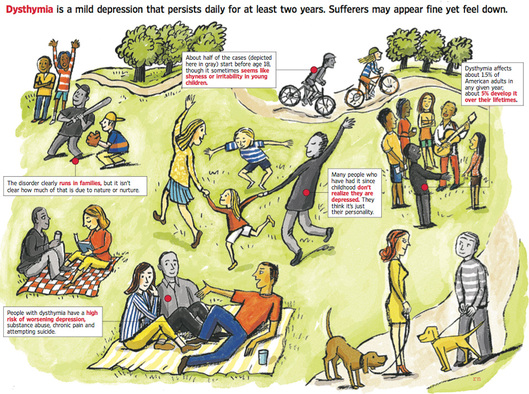

Dysthymia

What is Dysthymia?

Dysthymia, sometimes referred to as chronic depression, is a less severe form of depression but the depression symptoms linger for a long period of time, perhaps years. Those who suffer from dysthymia are usually able to function normally, but seem consistently unhappy.

It is common for a person with dysthymia to also experience major depression at the same time - swinging into a major depressive episode and then back to a more mild state of dysthymia. This is called double depression.

Symptoms of dysthymia include:

- Difficulty sleeping

- Loss of interest or the ability to enjoy oneself

- Excessive feelings of guilt or worthlessness

- Loss of energy or fatigue

- Difficulty concentrating, thinking or making decisions

- Changes in appetite

- Observable mental and physical sluggishness

- Thoughts of death or suicide

Seasonal Affective Disorder

What is Seasonal Affective Disorder?

Seasonal depression, called seasonal affective disorder (SAD), is a depression that occurs each year at the same time, usually starting in fall or winter and ending in spring or early summer. It is more than just "the winter blues" or "cabin fever." A rare form of SAD known as "summerdepression," begins in late spring or early summer and ends in fall.

Symptoms of Seasonal Affective Disorder

People who suffer from SAD have many of the common signs of depression: Sadness, anxiety, irritability, loss of interest in their usual activities, withdrawal from social activities, and inability to concentrate. But symptoms of winter SAD differ from symptoms of summer SAD.

Symptoms of winter SAD include the seasonal occurrence of:

- Fatigue

- Increased need for sleep

- Decreased levels of energy

- Weight gain

- Increase in appetite

- Difficulty concentrating

- Increased desire to be alone

- Weight loss

- Trouble sleeping

- Decreased appetite

Between 4-6% of the U.S. population suffers from SAD, while 10-20% may suffer from a more mild form of winter blues. Three-quarters of the sufferers are women, most of who are in their 20s, 30s, and 40s. Though SAD is most common during these ages, it can also occur in children and adolescents. Older adults are less likely to experience SAD. This illness is more commonly seen in people who live at high latitudes (geographic locations farther north or south of the equator), where seasonal changes are more extreme.

Bipolar Disorder

What is Bipolar Disorder?

Bipolar disorder or "manic-depressive" disease is a mental illness that causes people to have severe high and low moods. People with this type of depression swing from feeling overly happy and joyful (or irritable), to feeling very sad (or overly happy). Because of the highs and the lows -- or two poles of mood -- the condition is referred to as "bipolar" depression. In between episodes of mood swings, a person may experience normal moods. The word "manic" describes the periods when the person feels overly excited and confident. These feelings can quickly turn to confusion, irritability, anger, and even rage. The word "depressive" describes the periods when the person feels very sad or depressed. Because the symptoms are similar, sometimes people with bipolar depression are incorrectly diagnosed as having major depression.

Symptoms of Bipolar Disorder

The severity of the depressive and manic phases can differ from person to person, and in the same person at different times.

During manic periods, people with bipolar disorder may:

- Be overly happy, hopeful, and excited

- Change suddenly from being joyful to being angry and hostile

- Behave in strange ways and have odd beliefs

- Become restless

- Talk rapidly

- Have a lot of energy and need less sleep

- Believe they have many skills and powers and can do anything

- Make grand plans

- Show poor judgment, such as deciding to quit a job, or spending excessive amounts of money

- Become headstrong, annoying, or demanding

- Become easily distracted

- Abuse drugs and alcohol

- Have a higher sex drive

During depressive periods, people with bipolar disorder may:

- Feel empty, sad, or hopeless

- Feel guilty, worthless, or helpless

- Cry often

- Lose interest in things they usually enjoy, including sex

- Be unable to think clearly, make decisions, or remember things

- Sleep poorly

- Lose or gain weight

- Have low energy

- Abuse drugs and alcohol

- Complain of headaches, stomachaches, and other pains

- Become focused on death

- Attempt suicide

Who Experiences Bipolar Disorder?

According to the National Institute of Mental Health, over 2 million American adults experience bipolar disorder. Bipolar disorder usually begins in early adulthood, appearing before age 35. Children and adolescents, however, can develop this disease in more severe forms and in combination with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Some studies have indicated that bipolar depression is genetically inherited, occurring more commonly within families.

While bipolar disorder occurs equally in women and men, women with bipolar disorder may switch moods more quickly -- this is called "rapid cycling." Varying levels of sex hormones and thyroid activity, together with the tendency to be prescribed antidepressants, may contribute to the more rapid cycling seen in women. Women may also experience more periods of depression than men.

An estimated 60% of all people with bipolar disorder have drug or alcohol dependence. It has also been shown to occur frequently in people with seasonal depression and certain anxiety disorders, like posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

When Gray Days Signal a Problem

Dysthymia, a Mild Form of Depression, Can Last For Years and Often Goes Undiagnosed, Untreated

By Melinda Beck : WSJ : July 26, 2011

Barbara Bowman thought the lethargy she has felt since early childhood was due to laziness. As a teacher, wife and mother in Virginia, she would often become argumentative, and then have attacks of remorse. Marriage counseling led her to individual therapy that finally diagnosed dysthymia—mild, chronic depression that can sometimes last for decades.

People who are chronically a little depressed -- gloomy, grumpy, low energy -- have "dysthymic disorder," a condition with its own risks of job and family problems, as well as episodes of major depression. Melinda Beck has details.

Persistent feelings of hopelessness, irritability, low self-esteem and low energy are among the signs of dysthymia (dis-THY-mia). Officially, it's when someone has a dark mood on most days for at least two years. Eeyore, the downcast donkey of "Winnie the Pooh" is the poster child.

"Oftentimes, people have been that way since childhood and it just feels like who they are," says Daniel Klein, chairman of psychology at New York's Stony Brook University.

Yet there's growing evidence that even mild depression that is unrelenting can have severe consequences on work, family and social life, as well as high risk for suicide.

Researchers at the New York State Psychiatric Institute at Columbia University recently analyzed government surveys of 43,000 Americans and found that those who fit the criteria for dysthymia were more likely to have physical and emotional problems and more likely to be on Medicaid or Social Security disability than those with acute depression. They were also less likely to work full time, according to the study in the Journal of Affective Disorders in December.

Major depression shares some of the same symptoms, but it is three times as common and is more severe. It also tends to come in acute episodes, sometimes requiring hospitalization. Many people with dysthymia don't even realize they are depressed and never mention their feelings to a doctor.

Other studies have found that nearly 80% of people with dysthymia also have episodes of major depression—sometimes known as "double depression." People with chronic depression are more likely to attempt suicide than those with more acute forms, in part because their emotions have been rubbed so raw for so long.

Rufus Williams says he knew from about age 5 that he was sadder than other people and even tried to impale himself on a bed post to end his life. He was diagnosed with dysthymia in his 20s and has been in and out of treatment ever since. Even when he is feeling better, "I can feel the sadness right below the surface, like something waiting for you in the next room," says the 42-year-old telecommunications technician in Somerset, N.J. "It's made me a hard person to deal with in a relationship. I'm no picnic," he says.

Officially, dysthymia affects only about 1.5% of the U.S. population in any given year and 5% at some point during their lives. But the current definition excludes anyone who had an episode of major depression during the first two years.

Because symptoms often wax and wane over the years, some experts have recommended combining dysthymia, double depression and chronic major depression into a single category of chronic depression in the next edition of the American Psychiatric Association's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM 5).

Discussions are still ongoing, but Jan Alan Fawcett, a University of New Mexico psychiatrist who heads the Mood Disorders Work Group for DSM 5, says there is a growing consensus that how long depression lasts may be more important than the number of symptoms a patient has at any given time. "Once it's chronic, it should be viewed as just as severe as any depression," he says.

As with other forms of depression, there's no blood test or brain scan for dysthymia. The diagnosis is based on symptoms and history.

In about half of cases, the gloomy moods, chronic pessimism and low self-esteem begin before age 18, but the disorder can look like shyness or irritability in young children. It frequently runs in families, but it's unclear how much of that is due to nature or nurture.

Children who suffer abuse or trauma also have high rates of disorder. Whatever the cause, they often have trouble in school and in social relationships and are less likely to get married than their peers.

Dysthymia that starts later in life is often triggered by a major life stress, such as the loss of a job, the death of a loved one or the breakup of a marriage. Even then, people who have it may not recognize the lingering bad feelings as depression. It can also masquerade as chronic pain or other physical symptoms, further complicating diagnosis.

Like other mood disorders, dysthymia is diagnosed about twice as often in women as in men, but men may simply be more stoic, less willing to seek help or attempt to self-medicate.

"Men may belly up to the bar instead," Dr. Fawcett says.

Alternatively, some people with dysthymia are extremely high achievers and make an effort to be upbeat, but it may be hard to sustain. "There are people who are very good at masking it and mental-health professionals often don't take them as seriously as they should because they seem to be functioning so well," Dr. Klein says.

Often, people with dysthymia only discover they have it when they get much worse, and finally seek treatment and realize they've felt gloomy all their lives.

Dan Fields, a 46-year-old medical editor in Framingham, Mass., says he suspected he was depressed in high school but finally sought help when his anger at minor irritations and hypersensitivity to criticism threatened his marriage. "I got to the point where I had to get help," he says. A combination of individual and family therapy and antidepressants have helped "take the edge off things," and his threshold for annoyances is a lot higher. "I can still feel down or furious at times, but I'm less likely to get stuck in these moods," he says.

Dysthymia has not been studied as extensively as major depression, but treatments are generally the same. About one-third of people with chronic depression respond briskly to antidepressants, says James H. Kocsis, a professor of psychiatry at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York City.

"I can tell when I start receiving wedding announcements from patients. They start dating and socializing," he says. "Often their work improves dramatically, too. They're able to assert themselves. They ask for raises and promotions and stop taking mental-health days off."

Other patients need to try several medications, or combinations of them, to find relief. Talk therapy can also be helpful for chronic depression. To date, the best evidence is for cognitive behavioral therapy, in which patients learn to challenge negative thought patterns that bring them down.

Ms. Bowman, now 61, says cognitive behavioral therapy helped her identify feelings that caused her trouble. "But I needed medication, too," she says. "It helps you reach a place where you can help yourself."

A pilot study presented at the APA meeting this spring showed that Behavioral Activation Therapy, which stresses making positive changes to reach goals, can help those who respond to medication but still aren't functioning well. "In short, you're not depressed, but you still haven't gotten up off the couch and found a job," says David Hellerstein, a professor of clinical psychiatry at Columbia University School of Medicine, the lead investigator.

Experts stress that treatment for chronic depression generally takes longer than more acute forms. Relapse rates are high, and many people find they need to stay on medication long term. "You have to go with the expectation that this is not likely to go away in four to six weeks," Dr. Klein says.

And about one-quarter of people with dysthymia never do find much relief. Says Mr. Williams, "My main goal is to be able to handle the adversity that life throws at me in a healthy manner."

Understanding Empathy: Can You Feel My Pain?

By Richard A. Friedman, MD : NY Times Article : April 24, 2007

“Can I ask you a question?” the young woman ventured. “Have you ever been depressed? Do you have any idea how bad it feels?”

The patient, a married woman in her late 20s, had been tearfully describing her symptoms of depression during a consultation when she suddenly popped this question.

How could I possibly understand or help her, she seemed to be asking, if I had not personally experienced her pain?

Her question caught me by surprise and made me pause. O.K., I’ll admit it. I’m a cheerful guy who’s never really tasted clinical depression. But along the way I think I’ve successfully treated many severely depressed patients.

Is shared experience really necessary for a physician to understand or treat a patient? I wonder. After all, who would argue that a cardiologist would be more competent if he had had his own heart attack, or an oncologist more effective if he had had a brush with cancer?

Of course, a patient might feel more comfortable with a physician who has had personal experience with his medical illness, but that alone wouldn’t guarantee understanding, much less good treatment.

Still, many patients want their doctor to be someone with whom they can identify, not just a technically competent professional who can alleviate their pain.

As a psychiatrist, I’ve met many patients who have made requests for a specific type of therapist: African-Americans who want a black psychiatrist, Orthodox Jews who insist on a Jewish psychotherapist, women who ask for a feminist therapist and so on.

Not long ago, a gay man in his 30s called me to ask for a referral to a gay therapist. He was adamant about seeing only a gay clinician. “I can’t take the chance of getting a homophobic shrink,” he said.

His assumption was that if a therapist shared his sexgroup, there would be a kind of guaranteed basis for understanding or acceptance.

I did, in fact, refer him to an excellent colleague who happens to be gay, but the brief conversation left me troubled. All these patients who were searching ual orientation or ethnic for understanding had a misconception, I think, of what empathy is all about.

What is critical to understanding someone is not necessarily having had his or her experience; it is being able to imagine what it would be like to have it. Thus, I do not have to be black to empathize with the toxic effects of racial prejudice, or be a woman to know how I would feel about being denied promotion on the basis of sex.

Contrary to what many people believe, being empathic is not the same thing as being nice. In fact, empathy can sometimes be put to a very dark purpose.

When the Nazis were bombing Rotterdam in World War II, for example, they put sirens on the Stuka dive-bombers knowing full well that the sound would terrify and disorganize the Dutch. The Nazis imagined perfectly how the Dutch would feel and react. Fiendish, but the very essence of empathy.

In the right hands, empathy has tremendous positive therapeutic force and can narrow what looks like an unbridgeable gap between patients and therapists.

A few years back, I saw an elderly woman who had just lost her husband to cancer. “Oh, I hadn’t realized you were so young!” she exclaimed. “No offense, but maybe I need to see someone who’s a bit older.”

I asked her, “Are you worried that I can’t know what it feels like to lose someone you love and face life without him?”

True, I had never lost a partner, but it wasn’t hard to imagine her grief and anxiety about her future. That must have done the trick, because she stayed in treatment and never again mentioned my age.

Sometimes, though, patients should get exactly what they ask for in a therapist. One of my residents once saw a young woman from Africa who had survived hideous torture and rape and said that she didn’t think she could see a male therapist.

That struck me as entirely appropriate. Given her trauma, she simply could not have put her trust in a male therapist, no matter how empathic he might actually be.

What about patients whose demand for a particular therapist springs from nothing more than everyday prejudice? I remember a patient who once stormed into my office and demanded a white therapist to replace his therapist, who was black.

That’s a request I turned down, even knowing that this patient’s biased beliefs were an appropriate target for treatment. To do otherwise would have vindicated his prejudice and fundamentally compromised the therapy from the start.

In the end, empathy is what makes it possible for us to read each other. And it is the reason your doctor can understand your problem without actually having to live it.

Richard A. Friedman is director of the psychopharmacology clinic at the Weill Medical College of Cornell University.

To Reap Psychotherapy’s Benefits, Get a Good Fit

By Richard A. Friedman, MD : NY Times Article : August 21, 2007

Americans seem to like psychotherapy. Whether it’s for the mundane conflicts of everyday life or life-threatening illnesses like major depression, psychotherapy is widely viewed as a healthy, if not harmless, pursuit.

Yet unlike most other medical treatments, psychotherapy can take considerable time. An infection can be cured in days, but remission of severe depression or anxiety disorder usually takes weeks or months, and a personality disorder typically requires years of intensive psychotherapy.

So if the outcome may be months or years away, how can a person tell whether his psychotherapy is any good?

It’s harder than you’d think. For one thing, people commonly equate feeling better with getting good treatment. But since psychiatric disorders fluctuate spontaneously with time, like most illnesses, many patients would get better even if they got no treatment at all. A patient getting bad psychotherapy might flourish, while another patient getting exemplary treatment might suffer terribly.

Judging from one of the largest surveys of psychotherapy to date, most Americans who try psychotherapy think it is beneficial. In its 1994 annual questionnaire, Consumer Reports asked readers about their experience in psychotherapy. Of 7,000 subscribers who responded to the mental health questions, 4,100 saw mental health professionals. Most reported feeling better with therapy, regardless of whether they were treated by a psychologist, a psychiatrist or a social worker. And those in long-term therapy reported more improvement than those in short-term therapy.

Of course, not all therapy is helpful, and some of it can be downright harmful. Many patients have problems with relationships in the first place; they can find it difficult to extricate themselves from bad or ineffective therapy.

I recall a successful writer whom I saw in consultation. At 44, he had been in psychotherapy for several years and felt that while he had gained much self-understanding, his chronically depressed mood had not changed.

After seeing his depressed partner respond vividly to an antidepressant, he wondered if he too might benefit from a similar drug, but his therapist was opposed.

“He told me that I would be forestalling symptoms with medication that would return years later when I stopped medication,” the writer said. He persisted and got a second opinion.

“Be very wary of any therapist who discourages a consultation,” said a colleague of mine, Dr. Robert Michels, university professor of psychiatry at Weill Cornell Medical College. “If a patient is uncomfortable at the start of treatment, he should leave. But if a patient dislikes his therapy later on, he should discuss it with his therapist, and, if they can’t agree, then it’s time for a consultation. A competent therapist should welcome it.”

It is hardly surprising that many patients are reluctant to seek a second opinion; they may fear rejection by their therapist, or hurting the therapist’s feelings. And therapists, having egos like everyone else, may resist an independent consultation because they see it as a sign of their own failure, not to mention the obvious financial incentive to hold on to a patient.

It’s not just patients who have a hard time knowing if their treatments are helping them; sometimes the therapists themselves can’t tell.

In a study published last month in the journal Psychotherapy Research, Michael J. Lambert and Cory Harmon, psychologists at Brigham Young University, gave psychotherapy patients a questionnaire about how they were feeling and functioning. They randomly gave feedback from the questionnaires to half the patients’ therapists; the other half received strengthened feedback, which included patient self-assessment plus specific information about how the patients viewed their therapists and their social supports. These two groups were compared with a control group of patients whose therapists received no feedback.

The researchers found that giving feedback to therapists clearly improved treatment outcome: When therapists received no feedback, 21 percent of their patients deteriorated. With therapists who received regular feedback, 13 percent of patients deteriorated; with strengthened feedback, 7 percent of patients deteriorated.

The clear implication is that therapists are not always the best judge of how their patients are doing, perhaps because they are blinded by their own optimism and determination to succeed.

Some therapists might even view worsening during treatment as a sign of progress — a misguided “no pain, no gain” view of psychotherapy.

It’s probably easier to say what is bad psychotherapy than what is good, but there are qualities that all good therapies share. You should feel that you are understood as an individual, and that your therapist is compassionate and nonjudgmental. Good therapists should be able to explain the nature of your problem, and which of several treatments might help you.

Ask yourself not just whether you are getting better, but whether you are getting optimal treatment. Information about psychiatric disorders and recommended treatment can be found at several of reputable Web sites, including those of the American Psychiatric Association at www.psych.org, and the National Institute of Mental Health at www.nimh.nih.gov.

The psychiatric association’s treatment guidelines describe what is considered state-of-the-art treatment for various disorders and the empirical basis for the recommendations; see them at www.psych.org/psych_pract.

While it will not guarantee good therapy, seeing an accredited mental health professional provides some assurance of skill and competence.

Feeling better is important, of course, but it is possible to feel good and be stalled, where little significant change is taking place. If you are in therapy, don’t just rely on your own feelings to judge the treatment; speak to good friends and family members and see what they think about how you’re doing.

In the end, psychotherapy is a very personal business. If you need brain surgery, it doesn’t really matter if you like your surgeon as long as he’s skilled and competent. But in therapy, skill and competence are necessary but not enough; personal fit, more than almost anything, can make the therapy — or break it.

Richard A. Friedman is a professor of psychiatry at Weill Cornell Medical College.

Brought on by Darkness, Disorder Needs Light

By Richard A. Friedman, MD : NY Times Article : December 18. 2007

In a few days, the winter solstice will plunge us into the longest and darkest night of the year. Is it any surprise that we humans respond with a holiday season of relentless cheer and partying?

It doesn’t work for everyone, though. As daylight wanes, millions begin to feel depressed, sluggish and socially withdrawn. They also tend to sleep more, eat more and have less sex. By spring or summer the symptoms abate, only to return the next autumn.

Once regarded skeptically by the experts, seasonal affective disorder, SAD for short, is now well established. Epidemiological studies estimate that its prevalence in the adult population ranges from 1.4 percent (Florida) to 9.7 percent (New Hampshire).

Researchers have noted a similarity between SAD symptoms and seasonal changes in other mammals, particularly those that sensibly pass the dark winter hibernating in a warm hole. Animals have brain circuits that sense day length and control the timing of seasonal behavior. Do humans do the same?

In 2001, Dr. Thomas A. Wehr and Dr. Norman E. Rosenthal, psychiatrists at the National Institute of Mental Health, ran an intriguing experiment. They studied two patient groups for 24 hours in winter and summer, one group with seasonal depression and one without.

A major biological signal tracking seasonal sunlight changes is melatonin, a brain chemical turned on by darkness and off by light. Dr. Wehr and Dr. Rosenthal found that the patients with seasonal depression had a longer duration of nocturnal melatonin secretion in the winter than in the summer, just as with other mammals with seasonal behavior.

Why did the normal patients show no seasonal change in melatonin secretion? One possibility is exposure to industrial light, which can suppress melatonin. Perhaps by keeping artificial light constant during the year, we can suppress the “natural” variation in melatonin experienced by SAD patients.

There might have been a survival advantage, a few hundred thousand years back, to slowing down and conserving energy — sleeping and eating more — in winter. Could people with seasonal depression be the unlucky descendants of those well-adapted hominids?

Regardless, no one with SAD has to wait for spring and summer to feel better. “Bright light in the early morning is a powerful, fast and effective treatment for seasonal depression,” said Dr. Rosenthal, now a professor of clinical psychiatry at the Georgetown Medical School and author of “Winter Blues” (Guilford, 1998). “Light is a nutrient of sorts for these patients.”

The timing of phototherapy is critical. “To determine the best time for light therapy, you need to know about a person’s individual circadian rhythm,” said Michael Terman, director of the Center for Light Treatment and Biological Rhythms at the Columbia University Medical Center.

People are most responsive to light therapy early in the morning, just when melatonin secretion begins to wane, about eight to nine hours after the nighttime surge begins.

How can the average person figure that out without a blood test? By a simple questionnaire that assesses “morningness” or “eveningness” and that strongly correlates with plasma melatonin levels, according to Dr. Terman.

The nonprofit Center for Environmental Therapeutics has a questionnaire on its Web site (www.cet.org).

Once you know the optimal time, the standard course is 30 minutes of fluorescent soft-white light at 10,000 lux a day. You may discover that you are most photoresponsive very early, depending on whether you are a lark (early to bed and early to rise) or an owl.

The effects of light therapy are fast, usually four to seven days, compared with antidepressants, which can take four to six weeks to work.

For treatment while sleeping, there is dawn simulation. You get your own 90-minute sunrise from a light on a timer that starts with starlight intensity and ends with the equivalent of shaded sun. This is less effective than bright light.

It may sound suspiciously close to snake oil, but the newest promising therapy for SAD is negative air ionization. Dr. Terman found it serendipitously when he used a negative ion generator as a placebo control for bright light, only to discover that high-flow negative ions had positive effects on mood.

Heated and air-conditioned environments are low in negative ion content. Humid places, forests and the shore are loaded with them. It makes you wonder whether there is something, after all, to those tales about the mistral and all those hot dry winds, full of bad positive ions, that supposedly drive people mad.

Of course, you might decide to drop the light and ions and head for a sunny, tropical vacation.

Richard A. Friedman is a professor of psychiatry at Weill Cornell Medical College.

A Way Out of Depression

Coaxing a Loved One in Denial Into Treatment Without Ruining Your Relationship

By Elizabeth Bernstein WSJ Article : September 7, 2010

For people suffering from depression, the advice is usually the same: Seek help.

That simple-sounding directive, however, is often difficult for those with depression to follow because one common symptom of the disease is denial or lack of awareness. This can be frustrating for well-meaning family and friends—and is one of the key ways that treating mental illness is different from treating other illnesses.

Research shows that almost 15 million American adults in any given year have a major depressive disorder. And six million Americans have another mental illness, such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder or other psychotic disorders. Yet a full 50% of people with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia don't believe they are ill and resist seeking help. People with clinical depression resist treatment at similar rates, experts say.

You may have seen that seemingly ubiquitous TV commercial for the anti-depressant Cymbalta that repeatedly stresses that "depression hurts"—not just the person who is sick but the people who love that person as well. (Even the dog looks sad.) It's an ad, sure, but the sentiment is correct: People who live with a depressed person often become depressed themselves. And depression can have a terrible effect on relationships. It is a mental illness beyond just a depressed mood or situational sadness, in which a person is able to still enjoy life. Depression drains people of their interest in social connections. And it erases personality traits, taking away many of the very characteristics that made people love them in the first place.

"Depression makes a person see the world through gray-colored glasses," says Xavier Amador, a clinical psychologist and author of "I Am Not Sick. I Don't Need Help!" which was republished earlier this year in a 10th edition.

The challenge for a person with a depressed spouse, relative or close friend who refuses to get treatment is how to change that defiant person's mind. Reality show-style interventions and tough love are rarely successful, experts say. But there are techniques that can help. The key is to try and avoid a debate over whether your loved one is sick and instead look for common ground.

Patricia Gallagher knows how hard this can be. Her husband, John, came home from his job as a senior financial analyst for a pharmaceutical company one day and said his boss had given him three to six months to find a new job. He was crying.

Over the next year, Ms. Gallagher, who is 59 years old and lives in Chalfont, Pa., noticed her husband became irritable, sad, and short-tempered, withdrawing from her and the kids. He lost 55 pounds, stopped sleeping and would call her numerous times each day saying he couldn't "take it" anymore. He visited doctors dozens of times that year, getting examined for everything from a stomach ulcer to a brain tumor. Many doctors suggested he see a psychiatrist, but he didn't.

Ms. Gallagher tried everything she could think of to help. She urged her husband to relax or take a vacation. She begged him to see a psychologist, eventually scheduling the appointments herself, and even going alone when he refused to go, to ask advice. Eventually, he was hospitalized after becoming catatonic with anxiety, then attempted suicide by jumping out the hospital room window.

A decade later, the Gallaghers are separated. "I kept thinking, 'You've wrecked everything because you didn't go to therapy,'" she says. Mr. Gallagher, 59, a sales associate for a clothing company, says: "I didn't understand [depression] was a chemical thing. I thought it was a physical thing."

People who are mentally ill yet refuse or are unable to admit it or seek help may feel shame. They may feel vulnerable. Or their judgment may be impaired, keeping them from seeing that they're depressed.

"When a loved one tells them they are depressed and should see someone, they feel they are being criticized for being a complete failure," says Dr. Amador, director of the LEAP Institute in Taconic, NY, which trains mental-health professionals and family members how to circumvent a mentally ill person's denial of their disease.

Getting Around Denial

Experts say there are ways to circumvent a loved one's refusal to seek help:

Dr. Amador, who pioneered research into this syndrome 20 years ago, says it appears in about 50% of people with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Experts believe that similar damage sometimes occurs in people with clinical depression, although they are just beginning to research this.

At the LEAP Institute, they teach mental-health professionals and family members how to build enough trust with the mentally ill person that he will follow advice even if he won't admit to being sick. LEAP is an acronym for listen reflectively, empathize strategically, agree on common ground and partner on shared goals.

"It's the difference between boxing and judo, says Dr. Amador. "In boxing you throw a punch and the person blocks you. In judo, a person throws the punch and you take that punch and use their own resistance to move them where you want them."

Sometimes loved ones are able to help. Renee Rosolino, 44, a residential appraiser in Fraser, Mich., says she is sorry she waited so long to listen to her family.

They expressed concerns about her behavior 14 years ago, when she first started showing signs of bipolar disorder. At the time, she felt judged when her husband, parents and sisters told her that her personality had changed completely in six months. She stopped eating and sleeping, cried a lot and yelled at family members, and began pulling away from everything from social activities to church.

Repeatedly, her husband tried to talk to her about her behavior, but she insisted she was fine. He even enlisted Ms. Rosolino's sister to help. After dinner one night, they told her they were worried that she was depressed because she was sad, stressed and always on edge. Ms. Rosolino got mad and "shut down the conversation," she says.

In addition to being angry, Ms. Rosolino says she was terrified. When she was a child, Ms. Rosolino's father, an assistant vice president at a bank, had a mental breakdown and was taken to a psychiatric hospital in the middle of the night. "I never understood what happened to my father," she says. "And I had it in my head that if I went to talk to someone this would happen to me, to my children. I didn't want my kids to have those same feelings."

Ms. Rosolino's husband eventually broke through to her by asking her to speak to their pastor, pleading with her to do it for him and their children. "He said, 'It's OK. I am not going to leave you. I need you. Our kids need you,'" she says.

During her talk with the pastor, she broke down and told him about the pressures she felt as a mom—one of her children is autistic—and her irritation at feeling judged by her family. He told her that family members were worried about her and asked her to see a psychiatrist, just once, to set their minds at ease.

She agreed and started seeing the psychiatrist once a week and taking anti-depressants. Still, she has been hospitalized several times, usually, she says, when she stops taking her medication. But she has been stable for several years and says she has the people in her life to thank.

"Out of love and respect for the pastor and my family, I said I'd make the phone call," she says. "They made me feel safe."

Coaxing a Loved One in Denial Into Treatment Without Ruining Your Relationship

By Elizabeth Bernstein WSJ Article : September 7, 2010

For people suffering from depression, the advice is usually the same: Seek help.

That simple-sounding directive, however, is often difficult for those with depression to follow because one common symptom of the disease is denial or lack of awareness. This can be frustrating for well-meaning family and friends—and is one of the key ways that treating mental illness is different from treating other illnesses.

Research shows that almost 15 million American adults in any given year have a major depressive disorder. And six million Americans have another mental illness, such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder or other psychotic disorders. Yet a full 50% of people with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia don't believe they are ill and resist seeking help. People with clinical depression resist treatment at similar rates, experts say.

You may have seen that seemingly ubiquitous TV commercial for the anti-depressant Cymbalta that repeatedly stresses that "depression hurts"—not just the person who is sick but the people who love that person as well. (Even the dog looks sad.) It's an ad, sure, but the sentiment is correct: People who live with a depressed person often become depressed themselves. And depression can have a terrible effect on relationships. It is a mental illness beyond just a depressed mood or situational sadness, in which a person is able to still enjoy life. Depression drains people of their interest in social connections. And it erases personality traits, taking away many of the very characteristics that made people love them in the first place.

"Depression makes a person see the world through gray-colored glasses," says Xavier Amador, a clinical psychologist and author of "I Am Not Sick. I Don't Need Help!" which was republished earlier this year in a 10th edition.

The challenge for a person with a depressed spouse, relative or close friend who refuses to get treatment is how to change that defiant person's mind. Reality show-style interventions and tough love are rarely successful, experts say. But there are techniques that can help. The key is to try and avoid a debate over whether your loved one is sick and instead look for common ground.

Patricia Gallagher knows how hard this can be. Her husband, John, came home from his job as a senior financial analyst for a pharmaceutical company one day and said his boss had given him three to six months to find a new job. He was crying.

Over the next year, Ms. Gallagher, who is 59 years old and lives in Chalfont, Pa., noticed her husband became irritable, sad, and short-tempered, withdrawing from her and the kids. He lost 55 pounds, stopped sleeping and would call her numerous times each day saying he couldn't "take it" anymore. He visited doctors dozens of times that year, getting examined for everything from a stomach ulcer to a brain tumor. Many doctors suggested he see a psychiatrist, but he didn't.

Ms. Gallagher tried everything she could think of to help. She urged her husband to relax or take a vacation. She begged him to see a psychologist, eventually scheduling the appointments herself, and even going alone when he refused to go, to ask advice. Eventually, he was hospitalized after becoming catatonic with anxiety, then attempted suicide by jumping out the hospital room window.

A decade later, the Gallaghers are separated. "I kept thinking, 'You've wrecked everything because you didn't go to therapy,'" she says. Mr. Gallagher, 59, a sales associate for a clothing company, says: "I didn't understand [depression] was a chemical thing. I thought it was a physical thing."

People who are mentally ill yet refuse or are unable to admit it or seek help may feel shame. They may feel vulnerable. Or their judgment may be impaired, keeping them from seeing that they're depressed.

"When a loved one tells them they are depressed and should see someone, they feel they are being criticized for being a complete failure," says Dr. Amador, director of the LEAP Institute in Taconic, NY, which trains mental-health professionals and family members how to circumvent a mentally ill person's denial of their disease.

Getting Around Denial

Experts say there are ways to circumvent a loved one's refusal to seek help:

- BE GENTLE. Your loved one likely feels very vulnerable. "This is akin to talking to someone about his weight," says Ken Duckworth, a psychiatrist and medical director of the National Alliance on Mental Illness, an education, support and advocacy group. Simply saying "I love you" will help.

- SHARE YOUR OWN VULNERABILITY. If you've accepted help for anything—a problem at work, an illness, an emotional problem—tell your loved one about it. This will help reduce their shame, which is a contributing factor to denial.

- STOP TRYING TO REASON. Don't get into a debate about who is right and who is wrong. Ask questions instead. Learn what your loved one believes.

- FOCUS ON THE PROBLEMS YOUR LOVED ONE CAN SEE. Suggest they get help for those. For example, if they acknowledge sleep loss or problems concentrating, ask if they will seek help for those issues. "Don't hammer them with everything else," says Dr. Duckworth. "Nobody wants to be pathologized.

- SUGGEST YOUR LOVED ONE SEE A GENERAL PRACTITIONER. It is often far easier to persuade them to do this than to see a psychiatrist or psychologist. And this physician can diagnose depression, prescribe medicine or refer to a mental-health professional.

- WORK AS A TEAM. Ask if you can attend an appointment with the doctor or mental-health professional, just once, so you can share your observations and get advice on how best to help.

- ASK FOR HELP FOR YOURSELF. See a therapist to discuss how you are doing and to get help problem solving. Or contact organizations such as the National Alliance on Mental Illness to find information on caretaking or support groups.

- ENLIST OTHERS. Who else loves this person and can see the changes in their behavior? Perhaps a sibling, parent, adult child or religious leader can help you break through.

- LEVERAGE YOUR LOVE. Ask the person to get help for your sake. "If your loved one will not get help, you will not win on the strength of your argument," says Xavier Amador, a clinical psychologist and director of the LEAP Institute. "You will win on the strength of your relationship."

Dr. Amador, who pioneered research into this syndrome 20 years ago, says it appears in about 50% of people with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Experts believe that similar damage sometimes occurs in people with clinical depression, although they are just beginning to research this.

At the LEAP Institute, they teach mental-health professionals and family members how to build enough trust with the mentally ill person that he will follow advice even if he won't admit to being sick. LEAP is an acronym for listen reflectively, empathize strategically, agree on common ground and partner on shared goals.

"It's the difference between boxing and judo, says Dr. Amador. "In boxing you throw a punch and the person blocks you. In judo, a person throws the punch and you take that punch and use their own resistance to move them where you want them."

Sometimes loved ones are able to help. Renee Rosolino, 44, a residential appraiser in Fraser, Mich., says she is sorry she waited so long to listen to her family.

They expressed concerns about her behavior 14 years ago, when she first started showing signs of bipolar disorder. At the time, she felt judged when her husband, parents and sisters told her that her personality had changed completely in six months. She stopped eating and sleeping, cried a lot and yelled at family members, and began pulling away from everything from social activities to church.

Repeatedly, her husband tried to talk to her about her behavior, but she insisted she was fine. He even enlisted Ms. Rosolino's sister to help. After dinner one night, they told her they were worried that she was depressed because she was sad, stressed and always on edge. Ms. Rosolino got mad and "shut down the conversation," she says.

In addition to being angry, Ms. Rosolino says she was terrified. When she was a child, Ms. Rosolino's father, an assistant vice president at a bank, had a mental breakdown and was taken to a psychiatric hospital in the middle of the night. "I never understood what happened to my father," she says. "And I had it in my head that if I went to talk to someone this would happen to me, to my children. I didn't want my kids to have those same feelings."

Ms. Rosolino's husband eventually broke through to her by asking her to speak to their pastor, pleading with her to do it for him and their children. "He said, 'It's OK. I am not going to leave you. I need you. Our kids need you,'" she says.

During her talk with the pastor, she broke down and told him about the pressures she felt as a mom—one of her children is autistic—and her irritation at feeling judged by her family. He told her that family members were worried about her and asked her to see a psychiatrist, just once, to set their minds at ease.

She agreed and started seeing the psychiatrist once a week and taking anti-depressants. Still, she has been hospitalized several times, usually, she says, when she stops taking her medication. But she has been stable for several years and says she has the people in her life to thank.

"Out of love and respect for the pastor and my family, I said I'd make the phone call," she says. "They made me feel safe."

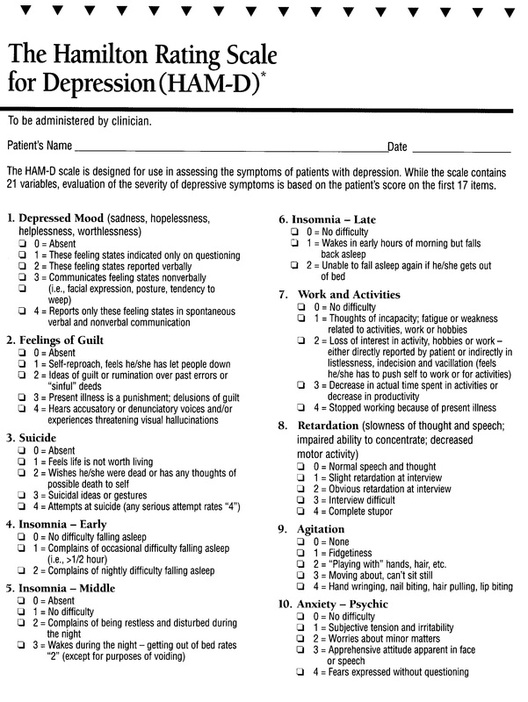

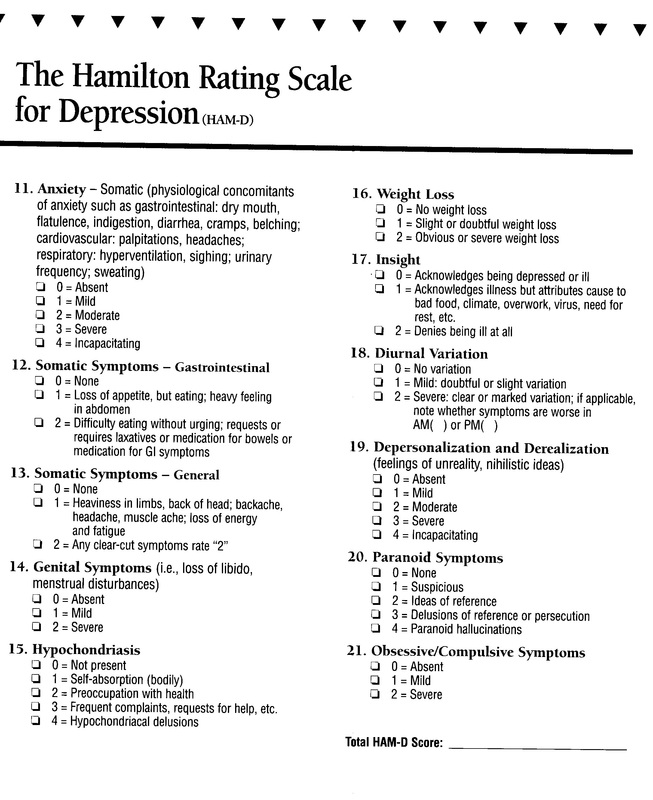

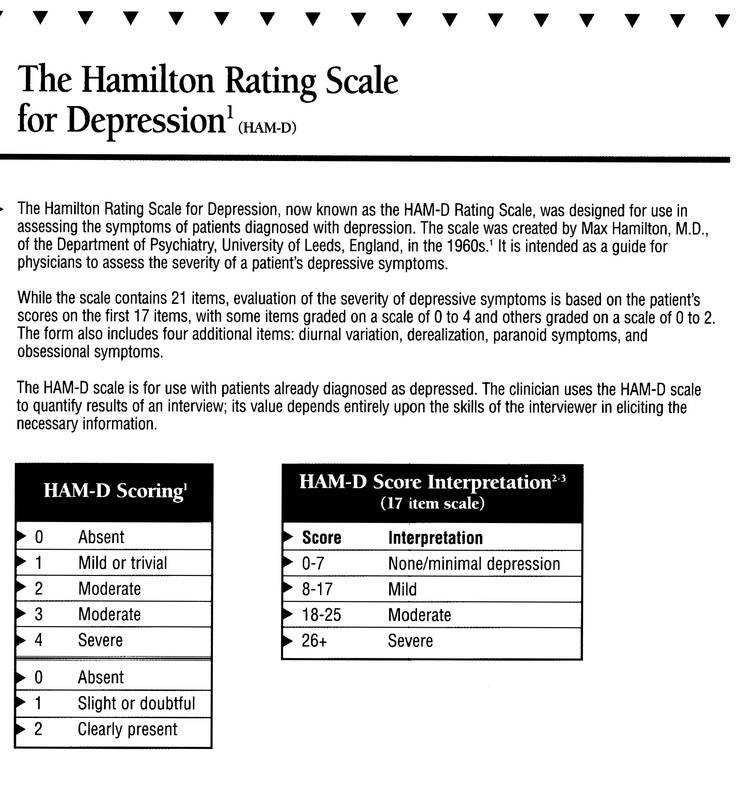

How Doctors Try to Spot Depression

Laura Landro : WSJ Article : December 7, 2010

Appearing anxious and overwhelmed on a routine visit with her primary-care provider, Lucy Cressey was prescribed an anti-anxiety medication and referred for talk therapy with a social worker.

The treatment recommendations came after Ms. Cressey agreed to fill out two questionnaires during the medical visit at the John Andrews Family Care Center in Boothbay Harbor, Maine, last year. Ms. Cressey scored high on both questionnaires, designed to help depression and anxiety.

Following the recent death of her best friend, a tough spinal surgery and some family financial woes, "a lot of stressors just snowballed for me," says Ms. Cressey, a 52-year-old veterinary technician. "But in rural Maine it's not so cool to talk about being depressed or anxious, and those questionnaires really open some doors for them to help you."

A growing number of primary-care providers are using screening tools to assess depression and other mental-health conditions during routine-care visits. They are also coordinating care of depressed patients with behavioral-health specialists. Such so-called mental-health-integration programs have been shown to reduce emergency-room visits and psychiatric-hospital admissions, and to increase employees' productivity at work.

One in four American adults who visit their primary-care doctors for a routine checkup or physical complaint also suffer from a mental-health problem, federal data show. But patients often don't raise the issue and doctors are too busy to ask. As a result, many never get treatment: Less than 38% of adults in the U.S. with mental illness received care for it last year, according to the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

A number of health-care groups work in tandem with behavioral-health providers. And some insurers, including Aetna, are promoting integrated care. About 5,000 physicians participate in Aetna's Depression in Primary Care program, which reimburses them for administering a Patient Health Questionnaire, or PHQ-9, to patients. Aetna is also training behavioral-health specialists, and stationing them in primary-care offices.

Health groups increasingly recognize that physical and emotional health are intertwined. Many patients with mental-health problems have two or more other issues such as heart disease, obesity or diabetes. As many as 70% of primary-care visits are triggered by underlying mental-health issues, according to behavioral-health researchers.

Intermountain Health in Salt Lake City, Utah, uses the PHQ-9 depression-screening tool in about 70 of its 130 medical practices. "The aim is to see if we stabilize patients and get them well in primary care, or whether we need to transition them to a behavioral-health expert," says Brenda Reiss-Brennan, director of the Intermountain Mental Health Integration program.

Wayne Cannon, an Intermountain physician helping lead the effort, says that patients who are asked to fill out the PHQ-9 form might be classified as mildly, moderately or severely depressed. Scoring programs on the questionnaires include guidelines to help doctors determine whether patients need just watchful waiting, medication or a course of psychotherapy. Patients can be immediately seen by a behavioral-health specialist in what's known as a "warm hand-off," Dr. Cannon says, making them more comfortable and likely to follow through with treatment.

Amy Young, a 32-year-old patient at Intermountain who has multiple sclerosis and takes antidepressants, says her primary-care doctor last year referred her to a psychologist who works in the same office and knew about some struggles faced by MS patients. "Your primary-care doctor can't talk to you for an hour at a time like a therapist can," says Ms. Young. "They can talk to each other if they have questions about anything going on with me and I feel much more relaxed because I'm used to going to the same office."

Intermountain says its own studies show that adult patients treated in its mental-health integration clinics have a lower rate of growth in charges for all services than those treated in clinics without the service. It also found that depressed patients treated in the clinics are 54% less likely to have emergency-room visits than are depressed patients in usual care clinics.

Patients being treated for depression should have the PHQ-9 test regularly administered, says John Bartlett, senior adviser in the mental-health-care program at the nonprofit Carter Center in Atlanta, which promotes mental-health treatment in primary care. If doctors don't offer it or don't repeat it, patients should take the test on their own and alert their doctor to any worrisome score, he says. The test is available free online at depressionscreening.org.

MaineHealth, a network of providers in the state that includes the John Andrews Center where Ms. Cressey is treated, recruited behavioral-health specialists to work in doctors' offices in different communities. Cynthia Cartwright, program director, says MaineHealth created an Adult Wellbeing Screener combining questions from the PHQ-9 for depression, and other tests for anxiety, bipolar disorder and substance abuse. "It's hard sometimes to reduce depression symptoms to the questions on a form, but you have to start somewhere, and I think they help doctors notice, ask about and treat mood disorders," says Debra Rothenberg, one of the physicians participating in the program.

Because behavioral-health services are typically covered separately under most insurance plans, doctors often have to advise patients to seek out additional mental-health care by calling their insurer for a referral. But many patients don't follow through to make the appointments, and there are often limits to their mental-health coverage. That is changing as new federal rules take effect prohibiting insurers from setting stricter limits on mental-health benefits than they do for other illnesses. And mental-health-integration programs are expected to get a boost from the new federal health law, which includes funding for programs creating "medical homes" that coordinate physical- and mental-health care for patients.

In the Aetna program, the insurer's case managers help track patients' progress and alert physicians if they are not improving. Case managers also assist with referrals to additional mental-health services.

Aetna's studies show that on average, patients completing the case-management program experienced a 4.7% increase in productivity at work, based on a questionnaire measuring the impact on productivity of employee health problems. Hyong Un, Aetna's chief psychiatric officer, says the insurer uses its own records to identify patients who may be candidates for depression screenings, including those who have stopped filling their antidepressant prescriptions.

Richard Wender, chair of the department of family medicine at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, says participation in the Aetna program has helped motivate its doctors to administer the screens and follow up with patients. Having a behavioral-health specialist in the same office "has helped us assess behavioral-health issues more frequently and have a plan in place to deal with them," he says.

Laura Landro : WSJ Article : December 7, 2010

Appearing anxious and overwhelmed on a routine visit with her primary-care provider, Lucy Cressey was prescribed an anti-anxiety medication and referred for talk therapy with a social worker.

The treatment recommendations came after Ms. Cressey agreed to fill out two questionnaires during the medical visit at the John Andrews Family Care Center in Boothbay Harbor, Maine, last year. Ms. Cressey scored high on both questionnaires, designed to help depression and anxiety.

Following the recent death of her best friend, a tough spinal surgery and some family financial woes, "a lot of stressors just snowballed for me," says Ms. Cressey, a 52-year-old veterinary technician. "But in rural Maine it's not so cool to talk about being depressed or anxious, and those questionnaires really open some doors for them to help you."

A growing number of primary-care providers are using screening tools to assess depression and other mental-health conditions during routine-care visits. They are also coordinating care of depressed patients with behavioral-health specialists. Such so-called mental-health-integration programs have been shown to reduce emergency-room visits and psychiatric-hospital admissions, and to increase employees' productivity at work.

One in four American adults who visit their primary-care doctors for a routine checkup or physical complaint also suffer from a mental-health problem, federal data show. But patients often don't raise the issue and doctors are too busy to ask. As a result, many never get treatment: Less than 38% of adults in the U.S. with mental illness received care for it last year, according to the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

A number of health-care groups work in tandem with behavioral-health providers. And some insurers, including Aetna, are promoting integrated care. About 5,000 physicians participate in Aetna's Depression in Primary Care program, which reimburses them for administering a Patient Health Questionnaire, or PHQ-9, to patients. Aetna is also training behavioral-health specialists, and stationing them in primary-care offices.

Health groups increasingly recognize that physical and emotional health are intertwined. Many patients with mental-health problems have two or more other issues such as heart disease, obesity or diabetes. As many as 70% of primary-care visits are triggered by underlying mental-health issues, according to behavioral-health researchers.

Intermountain Health in Salt Lake City, Utah, uses the PHQ-9 depression-screening tool in about 70 of its 130 medical practices. "The aim is to see if we stabilize patients and get them well in primary care, or whether we need to transition them to a behavioral-health expert," says Brenda Reiss-Brennan, director of the Intermountain Mental Health Integration program.

Wayne Cannon, an Intermountain physician helping lead the effort, says that patients who are asked to fill out the PHQ-9 form might be classified as mildly, moderately or severely depressed. Scoring programs on the questionnaires include guidelines to help doctors determine whether patients need just watchful waiting, medication or a course of psychotherapy. Patients can be immediately seen by a behavioral-health specialist in what's known as a "warm hand-off," Dr. Cannon says, making them more comfortable and likely to follow through with treatment.

Amy Young, a 32-year-old patient at Intermountain who has multiple sclerosis and takes antidepressants, says her primary-care doctor last year referred her to a psychologist who works in the same office and knew about some struggles faced by MS patients. "Your primary-care doctor can't talk to you for an hour at a time like a therapist can," says Ms. Young. "They can talk to each other if they have questions about anything going on with me and I feel much more relaxed because I'm used to going to the same office."

Intermountain says its own studies show that adult patients treated in its mental-health integration clinics have a lower rate of growth in charges for all services than those treated in clinics without the service. It also found that depressed patients treated in the clinics are 54% less likely to have emergency-room visits than are depressed patients in usual care clinics.

Patients being treated for depression should have the PHQ-9 test regularly administered, says John Bartlett, senior adviser in the mental-health-care program at the nonprofit Carter Center in Atlanta, which promotes mental-health treatment in primary care. If doctors don't offer it or don't repeat it, patients should take the test on their own and alert their doctor to any worrisome score, he says. The test is available free online at depressionscreening.org.

MaineHealth, a network of providers in the state that includes the John Andrews Center where Ms. Cressey is treated, recruited behavioral-health specialists to work in doctors' offices in different communities. Cynthia Cartwright, program director, says MaineHealth created an Adult Wellbeing Screener combining questions from the PHQ-9 for depression, and other tests for anxiety, bipolar disorder and substance abuse. "It's hard sometimes to reduce depression symptoms to the questions on a form, but you have to start somewhere, and I think they help doctors notice, ask about and treat mood disorders," says Debra Rothenberg, one of the physicians participating in the program.

Because behavioral-health services are typically covered separately under most insurance plans, doctors often have to advise patients to seek out additional mental-health care by calling their insurer for a referral. But many patients don't follow through to make the appointments, and there are often limits to their mental-health coverage. That is changing as new federal rules take effect prohibiting insurers from setting stricter limits on mental-health benefits than they do for other illnesses. And mental-health-integration programs are expected to get a boost from the new federal health law, which includes funding for programs creating "medical homes" that coordinate physical- and mental-health care for patients.

In the Aetna program, the insurer's case managers help track patients' progress and alert physicians if they are not improving. Case managers also assist with referrals to additional mental-health services.

Aetna's studies show that on average, patients completing the case-management program experienced a 4.7% increase in productivity at work, based on a questionnaire measuring the impact on productivity of employee health problems. Hyong Un, Aetna's chief psychiatric officer, says the insurer uses its own records to identify patients who may be candidates for depression screenings, including those who have stopped filling their antidepressant prescriptions.

Richard Wender, chair of the department of family medicine at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, says participation in the Aetna program has helped motivate its doctors to administer the screens and follow up with patients. Having a behavioral-health specialist in the same office "has helped us assess behavioral-health issues more frequently and have a plan in place to deal with them," he says.