- RETIREMENT ANNOUNCEMENT

- HOME PAGE

- "MYCHART" the new patient portal

- BELMONT MEDICAL ASSOCIATES

- MOUNT AUBURN HOSPITAL

- EMERGENCIES

- PRACTICE PHILOSOPHY

- MY RESUME

- TELEMEDICINE CONSULTATION

- CONTACT ME

- LAB RESULTS

- ePRESCRIPTIONS

- eREFERRALS

- RECORD RELEASE

- MEDICAL SCRIBE

- PHYSICIAN ASSISTANT (PA)

- Medicare Annual Wellness Visit

- Case management/Social work

- Quality Care Measures

- Emergency closing notice

- FEEDBACK

- Talking to your doctor

- Choosing..... and losing a doctor

- INDEX A - Z

- ALLERGIC REACTIONS

- Alternative Medicine

- Alzheimer's Disease

- Bladder Problems

- Blood disorders

- Cancer Concerns

- GENETIC TESTING FOR HEREDITARY CANCER

- Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

- Controversial Concerns

- CPR : Learn and save a life

- CRP : Inflammatory marker

- Diabetes Management

- Dizziness, Vertigo,Tinnitus and Hearing Loss

- EXERCISE

- FEMALE HEALTH

-

GASTROINTESTINAL topics

- Appendicitis

- BRAT diet

- Celiac Disease or Sprue

- Crohn's Disease

- Gastroenterologists for Colon Cancer Screening

- Colonoscopy PREP

- Constipation

- Gluten sensitivity, but not celiac disease

- Heartburn and GERD

- Hemorrhoids and Anal fissure

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- NASH : Non Alcoholic Steato Hepatitis

- FEET PROBLEMS

- HEART RELATED topics

-

INFECTIOUS DISEASES

- Antibiotic Resistance

- Cat bites >

- Clostridia difficile infection - the "antibiotic associated germ"

- CORONA VIRUS

- Dengue Fever and Chikungunya Fever

- Food borne illnesses

- Shingles Vaccine

- Hepatitis B

- Hepatitis C

- Herpes

- Influenza

- Helicobacter pylori - the "ulcer germ"

- HIV Screening

- Lyme and other tick borne diseases

- Measles

- Meningitis

- MRSA (Staph infection)

- Norovirus

- Sexually Transmitted Diseases

- Shingles (Herpes Zoster)

- Sinusitis

- West Nile Virus

- Whooping Cough (Pertussis)

- Zika virus and pregnancy

- INSURANCE related topics

- KIDNEY STONES

- LEG CRAMPS

- LIBRARY for patients

- LIFE DECISIONS

- MALE HEALTH

- Medication/Drug side effects

- MEDICAL MARIJUANA

- MENTAL HEALTH

- Miscellaneous Articles

-

NUTRITION - EXERCISE - WEIGHT

- Cholesterol : New guidelines for treatment

- Advice to lower your cholesterol

- Cholesterol : Control

- Cholesterol : Raising your HDL Level

- Exercise

- Food : Making Smart Choices

- Food : Making Poor Choices

- Food : Grape Fruit and Drug Interaction

- Food : Vitamins, Minerals and Supplements

- Omega 3 fatty acids

- Vitamin B12 deficiency

- Vitamin D

- Weight Loss

- ORTHOPEDICS

- PAIN

- PATIENTS' RIGHTS

- SKIN

- SLEEP

- SMOKING

- STROKE

- THYROID

- SUBSTANCE ABUSE

- Travel and Vaccination

- TREMOR

- Warfarin Anticoagulation

- OTHER STUFF FOLLOWS

- Fact or Opinion?

- Hippocratic Oath

- FREE ADVICE.......for what its worth!

- LAUGHTER.....is the best medicine

- Physicians Pet Peeves

- PHOTO ALBUM - its not all work!

- Cape Town, South Africa

- Tribute page

- The 100 Club

- Free Wi-Fi

REFERRALS

ONLINE REFERRAL REQUESTS

This is normally done through Antonella in our referral office.

Referral line : (617) 864-8822

[email protected]

Information about this follows below. If you want to submit ALL the required information online, we will transmit this to the referral office on your behalf.

Referral line : (617) 864-8822

[email protected]

Information about this follows below. If you want to submit ALL the required information online, we will transmit this to the referral office on your behalf.

REGULAR REFERRAL REQUESTS

Please be aware of the facts

How to get a referral.....

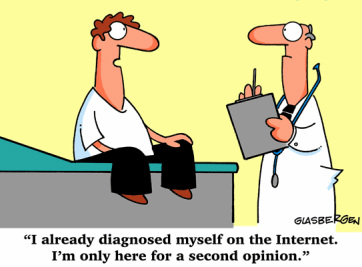

When to get a second opinion....

Advice on receiving a dire diagnosis.....

[email protected]

- You are welcome to discuss referrals to consultants by email and I will be happy to take all the needed information by email (see above), but the actual request for authorization must be done by them. Please give or leave them all the pertinent information: your name, date of birth, name of insurance plan, name of specialist, date of your appointment, brief reason for referral and your telephone number in case we have any questions. Try to give us adequate notice so we can do this in a timely fashion. Remember it is very difficult to back date referrals.

- If you give us all the required information with adequate time to submit it, we will process the referral on your behalf. Unless there is a problem processing the referral you will NOT hear from us.

- After almost 30 years I know my limitations and am not afraid to ask for another opinion. You should not be afraid to ask either. You have the right to a second opinion*. There should be no ego involved in getting you the best care. When you are sick and scared, the last thing you should worry about is your doctor's feelings.

"An education isn't how much you have committed to memory, or even how much you know. It's being able to differentiate between what you do know and what you don't." -Anatole France

- If you are a member of a managed health care plan, it is very important to discuss any referral with me BEFORE you make an appointment with a sub specialist. It is your responsibility to notify me as your primary care physician PRIOR to seeking services with a specialist. It is the policy of our office that we will NOT generate backdated referrals for patients who refer themselves (without first consulting their primary care physician) to specialists.

- It is also important to understand the concept of choosing a sub specialist within the "circle" of your primary care physician (or "PCP"). Remember that if you select me as your PCP I am affiliated with the Mount Auburn Hospital circle of physicians. Referrals outside of this circle are difficult and not encouraged. Over the years I've gotten to know and trust the sub specialists in this circle. If you do not feel comfortable within this referral circle, it would be my recommendation to select a PCP within the circle of your choice.

- I hope you will trust me to make sound medical decisions based on your medical needs and not be fearful of "managed care". I would be prepared to fight for you IF I felt that your health was truly being jeopardized by a "business" decision.

* Situations that may call for a second opinion:

- a poorly understood or communicated diagnosis

- an initial diagnosis by a non-cancer specialist

- a diagnosis by a cancer subspecialist

- an apparent lack of treatment options

- a treatment plan that involves a clinical trial

- rare cancers

- a treatment plan that involves surgery as the primary treatment

- a diagnosis that has been made at a small or rural hospital

- a treatment plan that involves aggressive treatment

- a treatment plan that involves specialized treatment

Advice on Dire Diagnoses From a Survivor

By Jane E. Brody : NY Times Article : July 3, 2007

Everyone knows lightning is not supposed to strike in the same place twice, let alone four times. Yet it did for Jessie Gruman, 53, the founder and president of the Center for the Advancement of Health, in Washington. She knows all too well what it’s like to be on the receiving end of bad health news: first at age 20 with a diagnosis of Hodgkin’s disease, 10 years later with cervical cancer, then five years ago with viral pericarditis (a potentially fatal infection of the heart’s lining) and just three years ago with colon cancer.

With each diagnosis, knowing her life hung in the balance, she was “stunned, then anguished” and astonished by “how much energy it takes to get from the bad news to actually starting on the return path to health.”

But following all four bouts with life-threatening illness, return to health she did, and the lessons she learned prompted her to write “AfterShock: What to Do When the Doctor Gives You — or Someone You Love — a Devastating Diagnosis,” published this year by Walker & Company.

I consider this book so valuable I plan to keep it on my bedside table should I need it later on. Its recommendations are based not just on the author’s experiences with illness, but also on interviews with more than 250 others: patients, family members, nurses, doctors, health plan administrators, managers of busy practices and nonprofit leaders.

The First 48 Hours

When confronted with a life-threatening diagnosis, most people feel a need to do something fast. But Dr. Gruman, who has a doctorate in social psychology, warns patients to “slow down” — take time to confirm the diagnosis, seek a second opinion, consider the various treatment options and their potential side effects and long-term consequences. Doing a little homework before rushing into treatment can help you get the treatment that will work best for you.

Rather than mull over what you might have done to cause the condition, Dr. Gruman points out that the past is past and that the problem now is how to handle the future. Nor should you worry about being less than optimistic. It’s normal to be depressed when you get terrible news about your future. As Dr. Gruman writes, “Expressing fear, sadness, anger or guilt will not make your disease worse.”

Her common-sense suggestions for getting through those first two days include the following:

- Recognize that this is a crisis and treat it as one. Don’t act as if nothing is happening. If you want to be with family or friends, tell them. If you don’t, tell them you need to be alone. And because memory is often slippery during a crisis, write down things you need to remember.

- Protect yourself. Talk if you want to, cry if you need to. You don’t have to explain to anyone what you decide to do. And if you find the information online confusing or frightening, stop searching.

- Don’t rush to form a treatment plan. Your main job now is to make the next doctor appointment and write down questions for your doctor, employer and insurance company.

- Eat and rest. Emotional stress is exhausting. Try to nap, or if you’re too agitated, go for a walk. Take some deep breaths and pursue your usual exercise if you feel like it. If sleep is elusive, ask your doctor for a temporary sleep aid.

- Next, learn as much as you can about your condition and its potential treatments so that you can make an informed choice. How does the disease affect the body? What may cause it to get worse? How does it usually progress? What treatments are available, and how does each affect the disease? What complications and side effects are likely with each treatment?

Enlist the Help You Need

When a good friend or family member is in trouble, people want — and usually offer — to help. And their help, both physical and emotional, can be very valuable, so take advantage of it.

Some people are also too ready to give advice and to tell about others they know who faced a similar predicament. If this is not what you want to hear, nip it in the bud without offending the person by saying, “Thank you, but each patient is unique, and I’m going by what my doctor tells me.”

To get the help you really need, you will have to tell people what you are up against and give those who offer help something to do. Dr. Gruman suggests listing the necessary tasks that you may not be able to accomplish on your own, like grocery shopping; picking the children up at school, getting them to play dates or taking them for an outing or sleepover; and making meals. You should also include on your list the possible need for someone to accompany you to doctor appointments, transport you to a treatment center or simply take you out for a restorative lunch or walk in the park.

Try to match the tasks to individuals best able to achieve them. But don’t be surprised if some say, “Is there anything I can do to help?” and then fail to follow through. You’ll soon discover whom you can count on.

At the Doctor’s Office

Taking someone with you to doctor appointments can be the most important thing you do. Under stress, memory is unreliable and even hearing can fail you. Dr. Gruman lists the characteristics of a person best suited to help at this time. Your partner should be free for at least two hours beyond when the appointment should end (delays are common); go over transportation and destination arrangements a day ahead of time; be willing to play whatever role you consider appropriate, like sitting quietly, taking notes or asking questions; and agree not to discuss the situation with others without your permission.

Of course, you should come to all doctor appointments with a list of all your questions and, if no one else is able to write down what the doctor says, you should tape-record the session so you can listen to it again at home and replay it for others if you choose to.

I cannot emphasize this point strongly enough. As Harry, a 78-year-old who accompanied his daughter to all her doctor appointments, put it to Dr. Gruman: “Even if there are three of us in the room, we each remember different things that were said — and sometimes the things we remember have different meanings to us” and need to be sorted out or clarified by the doctor.

As Dr. Gruman notes, it is difficult to absorb unfamiliar technical information that you may have to weigh as you make decisions. Distress about your diagnosis and what it means for your future can impair your ability to listen and understand. You may find it hard to question, disagree or advocate for your own best interests when you feel your life is in the doctor’s hands. And you may tend to dwell on the best-case or worst-case scenario, but having a record of what the doctor really said can provide a more realistic view of what lies ahead.

When

Doctors Don't Know What's Wrong

Posted by Alex Lickerman, MD

The first patient I ever saw as a first year resident came in with a litany of complaints, not one of which I remember today except for one—he had headaches. The reason I remember he had headaches isn’t because I spent so much time discussing them but rather the opposite: at the time I knew next to nothing about headaches and somehow managed to end the visit without ever addressing his at all, even though they were the primary reason he’d come to see me.

Then I rotated on a neurology service and actually learned quite a lot about headaches. Then when my patient came back to see me a few months later, I distinctly remember at that point not only being interested in his headaches but actually being excited to discuss them.

I often find myself thinking back to that experience when I’m confronted with a patient who has a complaint I can’t figure out, and I thought it would be useful to describe the various reactions doctors have to patients in general when they can’t figure out what’s wrong, why they have those reactions, and what you can do as a patient to improve your chances in such situations of getting good care.

THE SCIENTIFIC METHOD

Believing a wacky idea isn’t wacky in and of itself. Believing a wacky idea without proof,however, most certainly is. Likewise, disbelieving sensible ideas without disproving them when they’re disprovable is wacky as well. Unfortunately, patients are often guilty of the first thought error (“My diarrhea is caused by a brain tumor”) and doctors of the second (“brain tumors don’t cause diarrhea, so you can’t have a brain tumor”), leading in both instances to contentious doctor-patient relationships, missed diagnoses, and unnecessary suffering. Doctors sometimes aren’t willing to order tests that patients think are necessary because they think the patient’s belief about what’s wrong is wacky; they sometimes suggest a patient’s symptoms are psychosomatic when every test they run is negative but the symptoms persist; and they sometimes offer explanations for symptoms the patient finds improbable but refuse to pursue the cause of the symptoms any further.

Sometimes these judgments are correct and sometimes they’re not—but the experience of being on the receiving end of them is always frustrating for patients. However, given that your doctor has medical training and you don’t, the best you can sensibly hope for are judgments based on sound scientific reasoning rather than unconscious bias. Unfortunately, though, even the minds of the most rational scientists are teeming with unconscious biases. So a more realistic strategy might be to attempt to leverage your doctor’s biases in your favor.

EXPERT VS. NOVICE THINKING

In order to do this, you first need to know how doctors are trained to think. Medical students typically employ what’s called “novice” thinking when trying to figure out a diagnosis. They run through the entire list of everything known to cause the patient’s first symptom, then a second list of everything known to cause the patient’s second symptom, and so on. Then they look to see which diagnoses appear on all their lists and that new list becomes their list of “differential diagnoses.” It’s a cumbersome but powerful technique, its name notwithstanding.

A seasoned attending physician, on the other hand, typically employs “expert” thinking, defined as thinking that relies on pattern recognition. I’ve seen carpal tunnel syndrome so many times I could diagnose it in my sleep—but only learned to recognize the pattern of finger tingling in the first, second, and third digits, pain, and weakness occurring most commonly at night by my initial use of “novice” thinking. The main risk of relying on “expert” thinking is early closure—that is, of ceasing to consider what else might be causing a patient’s symptoms because the pattern seems so abundantly clear. Luckily, in most cases, it is clear.

But sometimes it isn’t. In those cases, your doctor may do one or more of the following:

A DOCTOR’S BIASES

Just which of the above approaches a doctor will take when confronted with symptoms he or she can’t figure out is determined both by his or her biases and life-condition—and all doctors struggle with both. To obtain the best performance from your doctor, your objective is to get him or her into a high a life-condition and as free from the influences of his or her biases (good and bad) as possible.

Negative influences on a doctor’s life-condition include all the things that negatively influence yours, as well as the following things that may happen to them on a daily basis:

HOW TO GET YOUR DOCTOR ON YOUR SIDE

Unfortunately, your ability to raise your doctor’s life-condition is as limited as your ability to raise anyone else’s and even more so when you don’t feel well. Good humor, if you can muster it, may be your best option.

But in dealing with your doctor’s biases, you have on your side a fact I firmly believe to be true: most doctors want to do a good job and help their patients as best they can. So what exactly can you do to maximize your doctor’s ability to help you?

Posted by Alex Lickerman, MD

The first patient I ever saw as a first year resident came in with a litany of complaints, not one of which I remember today except for one—he had headaches. The reason I remember he had headaches isn’t because I spent so much time discussing them but rather the opposite: at the time I knew next to nothing about headaches and somehow managed to end the visit without ever addressing his at all, even though they were the primary reason he’d come to see me.

Then I rotated on a neurology service and actually learned quite a lot about headaches. Then when my patient came back to see me a few months later, I distinctly remember at that point not only being interested in his headaches but actually being excited to discuss them.

I often find myself thinking back to that experience when I’m confronted with a patient who has a complaint I can’t figure out, and I thought it would be useful to describe the various reactions doctors have to patients in general when they can’t figure out what’s wrong, why they have those reactions, and what you can do as a patient to improve your chances in such situations of getting good care.

THE SCIENTIFIC METHOD

Believing a wacky idea isn’t wacky in and of itself. Believing a wacky idea without proof,however, most certainly is. Likewise, disbelieving sensible ideas without disproving them when they’re disprovable is wacky as well. Unfortunately, patients are often guilty of the first thought error (“My diarrhea is caused by a brain tumor”) and doctors of the second (“brain tumors don’t cause diarrhea, so you can’t have a brain tumor”), leading in both instances to contentious doctor-patient relationships, missed diagnoses, and unnecessary suffering. Doctors sometimes aren’t willing to order tests that patients think are necessary because they think the patient’s belief about what’s wrong is wacky; they sometimes suggest a patient’s symptoms are psychosomatic when every test they run is negative but the symptoms persist; and they sometimes offer explanations for symptoms the patient finds improbable but refuse to pursue the cause of the symptoms any further.

Sometimes these judgments are correct and sometimes they’re not—but the experience of being on the receiving end of them is always frustrating for patients. However, given that your doctor has medical training and you don’t, the best you can sensibly hope for are judgments based on sound scientific reasoning rather than unconscious bias. Unfortunately, though, even the minds of the most rational scientists are teeming with unconscious biases. So a more realistic strategy might be to attempt to leverage your doctor’s biases in your favor.

EXPERT VS. NOVICE THINKING

In order to do this, you first need to know how doctors are trained to think. Medical students typically employ what’s called “novice” thinking when trying to figure out a diagnosis. They run through the entire list of everything known to cause the patient’s first symptom, then a second list of everything known to cause the patient’s second symptom, and so on. Then they look to see which diagnoses appear on all their lists and that new list becomes their list of “differential diagnoses.” It’s a cumbersome but powerful technique, its name notwithstanding.

A seasoned attending physician, on the other hand, typically employs “expert” thinking, defined as thinking that relies on pattern recognition. I’ve seen carpal tunnel syndrome so many times I could diagnose it in my sleep—but only learned to recognize the pattern of finger tingling in the first, second, and third digits, pain, and weakness occurring most commonly at night by my initial use of “novice” thinking. The main risk of relying on “expert” thinking is early closure—that is, of ceasing to consider what else might be causing a patient’s symptoms because the pattern seems so abundantly clear. Luckily, in most cases, it is clear.

But sometimes it isn’t. In those cases, your doctor may do one or more of the following:

- Revert to “novice” thinking. Which, in fact, is completely appropriate. We’re taught in medical school that approximately 90% of all diagnoses are made from the history, so if we can’t figure out what’s wrong, we’re supposed to go back to the patient’s story and dig some more. This also involves reading, thinking, and possibly doing more tests, for which your doctor may or may not have the stamina.

- Ask a specialist for help. Which requires your doctor to recognize he or she is out of his or her depth and needs help.

- Cram your symptoms into a diagnosis he or she does recognize, even if the fit is imperfect. Though this may seem at first glance like a thought error, it often yields the correct answer. We have a saying in medicine: uncommon presentations of common diseases are more common than common presentations of uncommon diseases. In other words, presenting with a set of symptoms that are unusual or atypical for a particular disease doesn’t rule out your having that disease, especially if that disease is common. Or as one of my medical school teachers put it: “A patient’s body frequently fails to read the textbook.”

- Dismiss the cause of your symptoms as coming from stress, anxiety, or some other emotional disturbance. Sometimes your doctor is unable to identify a physical cause for your symptoms and turns reflexively to stress or anxiety as the explanation, given that the power of the mind to manufacture physical symptoms from psychological disturbances is not only well-documented in the medical literature but a common experience most of us have had (think of “butterflies” in your stomach when you’re nervous). And sometimes your doctor will be right. A physician named John Sarno knows this well and has a cohort of patients who seem to have benefited greatly from his theory that some forms of back pain are created by unconscious anger. However, the diagnosis of stress and anxiety should never be made by exclusion (meaning every other reasonable possibility has been appropriately ruled out and stress and anxiety is all that’s left); rather, there should be positive evidence pointing to stress and anxiety as the cause (eg, you should actually be feeling stressed and anxious about something). Unfortunately, doctors frequently reach for a psychosomatic explanation for a patient’s symptoms when testing fails to reveal a physical explanation, thinking if they can’t find a physical cause then no physical cause exists. But this reasoning is as sloppy as it is common. Just because science has produced more knowledge than any one person could ever master, we shouldn’t allow ourselves to imagine we’ve exhausted the limits of all there is to know (a notion as preposterous as it is unconsciously attractive). Just because your doctor doesn’t know the physical reason your wrist started hurting today doesn’t mean the pain is psychosomatic. A whole host of physical ailments bother people every day for which modern medicine has no explanation: overuse injuries (you’ve been walking all your life and for some reason now your heel starts to hurt); extra heart beats; twitching eyelid muscles; headaches.

- Ignore or dismiss your symptoms. This is different from the application of a “tincture of time” that doctors often employ to see if symptoms will improve on their own (as they often do). Rather, this a reaction to being confronted with a problem your doctor doesn’t understand or know how to handle. That a doctor may ignore or dismiss your symptoms unconsciously (as I did with my first-ever patient) is no excuse for doing so.

A DOCTOR’S BIASES

Just which of the above approaches a doctor will take when confronted with symptoms he or she can’t figure out is determined both by his or her biases and life-condition—and all doctors struggle with both. To obtain the best performance from your doctor, your objective is to get him or her into a high a life-condition and as free from the influences of his or her biases (good and bad) as possible.

Negative influences on a doctor’s life-condition include all the things that negatively influence yours, as well as the following things that may happen to them on a daily basis:

- They fall behind in clinic. Your doctor may be naturally slow or frequently have to spend extra time with patients who are especially ill or emotionally upset.

- They have to deal with difficult or demanding patients. Hard not to enter into a defensive, paternalistic posture when too many of these types of patients show up on your schedule.

- They feel like they don’t have enough time to do a good job. With fewer and fewer resources, doctors are being asked (like everyone) to do more and more.

- They have to deal with a morass of paperwork in a hopelessly inefficient health care system. The amount of time most doctors must spend justifying their decisions to third-party insurance carriers is growing at an alarming rate.

- Not wanting to diagnose bad illnesses in their patients. Leading sometimes to an incomplete list of differential diagnoses.

- Not wanting to induce anxiety in their patients. Leading sometimes to insufficient explanations of their thought processes, which often paradoxically leads to more patient anxiety.

- Over-relying on evidence-based medicine. Though the practice of evidence-based medicine should be the standard, many physicians forget there’s a great difference between “there’s no evidence existing in the medical literature to link symptom X with disease Y” and “there’s no evidence existing to link symptom X with disease Y because it’s not yet been studied.”

- Not liking their patient. Leading to impatience, not listening, and not taking enough time to think though the patient’s complaints.

- Liking their patient too much. Leading to biases #1 and #2.

- Thinking a patient’s symptoms are caused by one diagnosis instead of many. Also known as Ockham’s razor, sometimes it’s true and sometimes it isn’t.

- Wanting to be right more than wanting their patient to get better. Res ipsa loquitur (the thing speaks for itself).

- Believing their first thoughts about the diagnosis are more likely to be correct than any subsequent thoughts. If your doctor is too attached to a diagnosis simply because it’s the one he or she thought of first or has seen more than other, less common diagnoses, he or she may avoid pursuing other possibilities.

- Failing to consider that a test result may be in error. This doesn’t happen commonly, but it certainly does happen.

- Wanting to avoid feeling ineffectual. Some diagnoses are more amenable to therapy than others. No patient wants to have an untreatable illness and no doctor wants to diagnose it.

- Having an aversion to being manipulated. Manipulation is especially common in patients suffering from chronic pain syndromes (who may at times appear drug-seeking rather than pain relief-seeking). No one likes to be manipulated, but a wise mentor of mine once said, “The question isn’t whether or not your patients will try to manipulate you. The question is how will they try to manipulate you.” Coming to terms with this truth is vital for any doctor to have successful relationships with their patients.

HOW TO GET YOUR DOCTOR ON YOUR SIDE

Unfortunately, your ability to raise your doctor’s life-condition is as limited as your ability to raise anyone else’s and even more so when you don’t feel well. Good humor, if you can muster it, may be your best option.

But in dealing with your doctor’s biases, you have on your side a fact I firmly believe to be true: most doctors want to do a good job and help their patients as best they can. So what exactly can you do to maximize your doctor’s ability to help you?

- Position your symptoms and requests carefully. Don’t demand medications or tests. Ask about them. Wonder about them. It’s perfectly all right to bring up research you’ve done about your symptoms, but explicitly express your openness to the possibility that your ideas might be wrong. Not that you should aim for subservience by any means, but rather for a genuine partnership.

- Remain reasonable even when you’re irritated. Most doctors, even when stressed, will respond to reason and reasonableness in kind.

- If your doctor suggests your symptoms might be due to stress, acknowledge he or she may be right. Even if you disagree. First of all, your doctor may be right, even if it doesn’t feel that way to you. Secondly, if you dismiss the notion out of hand, you might make your doctor defensive and therefore more likely to cling to an idea that a moment before was only one possibility among many.

- Ask questions that promote transparent, logical thinking. Many doctors don’t explain their thought processes clearly. Write all your questions down before your visits and ask smart questions that actually help your doctor think through your symptoms and his or her approach to working them up (“What possibilities will this test rule in or out?” “What else is on your list of possible diagnoses?”). Of course, this presumes you’re comfortable knowing the answers. I recommend you summon your courage to ask these questions, however, because they’ll encourage sharper thinking from your doctor.

- Be explicit about how you want your doctor to work with you. Show them you’re interested in understanding the process of medical detective work. Position yourself as your doctor’s student. Nothing helps improve someone’s thought process like having to explain it to someone else.

- Ask your doctor to explain the risks and benefits of any proposed test or treatment quantitatively. Get percentages for risks and compare them to the risks of activities you tolerate every day. For instance, your annual risk of dying in a motor vehicle accident is 0.016%. You’d be surprised how many worrisome side effects to drugs, for example, occur at an even lower frequency.

- Get second opinions. And sometimes third opinions. And sometimes more. Do this carefully, recognizing that in doing so you risk ending up even more confused than you were with only one opinion. But don’t assume because your doctor doesn’t know what’s going on that no one else does either. There’s almost no way for you to be sure your doctor doesn’t know what’s wrong because he or she doesn’t know or because no one knows. Sometimes you have to go through multiple doctors until you finally find the right one with the right experience to figure out your problem (if your insurance will let you, of course). Neither doctors nor patients like to acknowledge this, but serendipity sometimes plays a role in arriving at the right diagnosis. I once figured out why a patient had been nauseated for 30 years after they’d been seen by almost as many doctors. The patient said something that just happened to make me think of an obscure diagnosis I’d never seen but had read about. I looked it up, sent the patient for a test, and found the answer.

What if the Doctor Is Wrong?

Some Cancers, Asthma, Other Conditions Can Be Tricky to Diagnose, Leading to Incorrect Treatments

By Laura Landro : WSJ : January 17, 2012

When a CT scan showed multiple tumors in Dawna Harwell's pelvis, abdomen and spine in 2008, her doctors in Dallas told her she might have ovarian cancer, which can be especially deadly.

A biopsy came back with inconclusive results, and Ms. Harwell wasted no time in seeking a second opinion at MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston. "I went through every test in the book," says Ms. Harwell. Still, doctors couldn't be sure what she had. Finally, she underwent a surgical procedure to diagnose her case: It wasn't ovarian cancer after all, but a rare form of lymphoma. The 47-year-old horse trainer in Collinsville, Texas, underwent a rigorous regimen of chemotherapy that ended last spring. At her first six-month checkup in October, she received a clean bill of health.

Evidence is mounting that second opinions—particularly on radiology images and pathology slides from biopsies—can lead to significant changes in a patient's diagnosis or in recommendations for treating a disease. Some malignancies, including lymphomas and rare cancers of the thyroid and salivary glands, are notoriously tricky to diagnose correctly; test results can be inconclusive or return false results. After a decade of annual mammograms, more than half of women will receive at least one false positive recall on a breast-cancer screening, a recent study found. And nearly half of malpractice claims at Harvard University's medical institutions that resulted in serious patient harm or death in the past five years were diagnostic errors, according to its liability company Crico/RMF.

Thomas Feeley, vice president of medical operations at MD Anderson, says as many as 25% of patients who arrive at the center with diagnoses for certain cancers such as lymphoma may receive a different diagnosis. Overall, 3% of MD Anderson patients each year end up with a significant change that affects what treatment they receive. "When you get cancer, the first thing you may want to do is jump to get treatment with the first person you talk to," Dr. Feeley says. "But taking the time to get a second opinion about the diagnosis you have and a careful evaluation of what treatments there are can be lifesaving."

Kim Henderson, a paralegal in Houston, came to MD Anderson to be treated for cervical cancer after being diagnosed elsewhere. Pathologists performed another biopsy that revealed she had a noninvasive precursor to cervical cancer—and not the far more serious invasive type as previously believed. Although she still needed surgery, her doctors told her she could skip the radiation and chemotherapy that had originally been part of the treatment plan.

"I felt like it was a miracle and I was spared from this unnecessary treatment," says Ms. Henderson, who had lost a sister to cancer.

Second opinions are important for other diseases, as well. National Jewish Health, a Denver medical center, found in a study that more than half of patients it diagnosed with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease had previously been misdiagnosed with asthma, leading to inappropriate treatments. A form of dementia is often incorrectly diagnosed as Alzheimer's, and studies show that doctors may misdiagnose coronary artery disease as other conditions.

Not everyone should have a second opinion, of course. Health-care costs would soar if they did, says Robert Wachter, chief of the division of hospital medicine at the University of California, San Francisco. "There is also a risk you can get overwhelmed by conflicting opinions when you are in a terribly vulnerable position." In the end, he says, patients must pick a doctor they trust and go with his or her recommendation.

Many health insurers require a second opinion before approving major surgery or expensive treatments. Patients shouldn't hesitate to tell a doctor they want a second opinion, and they are entitled to their slides, pathology reports and other information to take elsewhere. Major medical centers, including Johns Hopkins Medicine and MD Anderson, have second-opinion services that doctors can refer patients to, or patients can contact directly, to get an independent assessment.

Hardeep Singh, chief of the health policy and quality program at Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center in Houston, says a growing number of centers are requiring an internal second review of pathology reports to prevent misdiagnosis. If the second opinion differs markedly, a third opinion may be necessary to get a consensus on what course of treatment is best.

Misdiagnoses can come about for various reasons. Pathologists and radiologists may misread slides and scans or fail to use the latest tests or technology. Sometimes doctors may simply get stuck on the idea of one diagnosis and ignore or overlook evidence it might be something else. This month, the president of Argentina had her thyroid removed after being diagnosed with cancer from a biopsy, but the doctors announced after the surgery that she in fact had a benign condition.

Jonathan Lewin, chief radiologist at Johns Hopkins Hospital, says that on an annual basis, his group sees a significant discrepancy in diagnosis in about 8% of cases, such as a brain tumor mistakenly thought to be an infection or a stroke or multiple sclerosis that initially is diagnosed as a brain tumor. "The last thing a surgeon wants to do is take out a piece of brain and find out this isn't what we thought it was," Dr. Lewin says.

For Ms. Harwell, the Texas horse trainer, it took more than a month before MD Anderson finally identified her condition. Because certain markers for ovarian cancer weren't present, doctors began to consider a form of lymphoma, although tests for that were inconclusive. Lymphoma expert Rick Hagemeister says he told Ms. Harwell the only way to get a firm diagnosis would be from a surgical biopsy of the tumors massed in her pelvis.

Ms. Harwell says gynecologic oncologist Kathleen Schmeler told her the surgery needed to be a hysterectomy, which would also be the treatment for ovarian cancer on the chance that was the problem. Seven days later, pathology reports from the procedure came back: follicular lymphoma, a rare form of the disease that would require eight rounds of chemotherapy regimen R-CHOP followed by two years of a maintenance drug, Rituxan.

Ms. Harwell says she was grateful that MD Anderson didn't begin treating her with what might have been the wrong regimen. Shortly after starting chemotherapy, Ms. Harwell showed at the Appaloosa World Show. When she took off her hat, a lot of her hair came off, too.

What to Ask When Seeking A Second Opinion:

Some Cancers, Asthma, Other Conditions Can Be Tricky to Diagnose, Leading to Incorrect Treatments

By Laura Landro : WSJ : January 17, 2012

When a CT scan showed multiple tumors in Dawna Harwell's pelvis, abdomen and spine in 2008, her doctors in Dallas told her she might have ovarian cancer, which can be especially deadly.

A biopsy came back with inconclusive results, and Ms. Harwell wasted no time in seeking a second opinion at MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston. "I went through every test in the book," says Ms. Harwell. Still, doctors couldn't be sure what she had. Finally, she underwent a surgical procedure to diagnose her case: It wasn't ovarian cancer after all, but a rare form of lymphoma. The 47-year-old horse trainer in Collinsville, Texas, underwent a rigorous regimen of chemotherapy that ended last spring. At her first six-month checkup in October, she received a clean bill of health.

Evidence is mounting that second opinions—particularly on radiology images and pathology slides from biopsies—can lead to significant changes in a patient's diagnosis or in recommendations for treating a disease. Some malignancies, including lymphomas and rare cancers of the thyroid and salivary glands, are notoriously tricky to diagnose correctly; test results can be inconclusive or return false results. After a decade of annual mammograms, more than half of women will receive at least one false positive recall on a breast-cancer screening, a recent study found. And nearly half of malpractice claims at Harvard University's medical institutions that resulted in serious patient harm or death in the past five years were diagnostic errors, according to its liability company Crico/RMF.

Thomas Feeley, vice president of medical operations at MD Anderson, says as many as 25% of patients who arrive at the center with diagnoses for certain cancers such as lymphoma may receive a different diagnosis. Overall, 3% of MD Anderson patients each year end up with a significant change that affects what treatment they receive. "When you get cancer, the first thing you may want to do is jump to get treatment with the first person you talk to," Dr. Feeley says. "But taking the time to get a second opinion about the diagnosis you have and a careful evaluation of what treatments there are can be lifesaving."

Kim Henderson, a paralegal in Houston, came to MD Anderson to be treated for cervical cancer after being diagnosed elsewhere. Pathologists performed another biopsy that revealed she had a noninvasive precursor to cervical cancer—and not the far more serious invasive type as previously believed. Although she still needed surgery, her doctors told her she could skip the radiation and chemotherapy that had originally been part of the treatment plan.

"I felt like it was a miracle and I was spared from this unnecessary treatment," says Ms. Henderson, who had lost a sister to cancer.

Second opinions are important for other diseases, as well. National Jewish Health, a Denver medical center, found in a study that more than half of patients it diagnosed with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease had previously been misdiagnosed with asthma, leading to inappropriate treatments. A form of dementia is often incorrectly diagnosed as Alzheimer's, and studies show that doctors may misdiagnose coronary artery disease as other conditions.

Not everyone should have a second opinion, of course. Health-care costs would soar if they did, says Robert Wachter, chief of the division of hospital medicine at the University of California, San Francisco. "There is also a risk you can get overwhelmed by conflicting opinions when you are in a terribly vulnerable position." In the end, he says, patients must pick a doctor they trust and go with his or her recommendation.

Many health insurers require a second opinion before approving major surgery or expensive treatments. Patients shouldn't hesitate to tell a doctor they want a second opinion, and they are entitled to their slides, pathology reports and other information to take elsewhere. Major medical centers, including Johns Hopkins Medicine and MD Anderson, have second-opinion services that doctors can refer patients to, or patients can contact directly, to get an independent assessment.

Hardeep Singh, chief of the health policy and quality program at Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center in Houston, says a growing number of centers are requiring an internal second review of pathology reports to prevent misdiagnosis. If the second opinion differs markedly, a third opinion may be necessary to get a consensus on what course of treatment is best.

Misdiagnoses can come about for various reasons. Pathologists and radiologists may misread slides and scans or fail to use the latest tests or technology. Sometimes doctors may simply get stuck on the idea of one diagnosis and ignore or overlook evidence it might be something else. This month, the president of Argentina had her thyroid removed after being diagnosed with cancer from a biopsy, but the doctors announced after the surgery that she in fact had a benign condition.

Jonathan Lewin, chief radiologist at Johns Hopkins Hospital, says that on an annual basis, his group sees a significant discrepancy in diagnosis in about 8% of cases, such as a brain tumor mistakenly thought to be an infection or a stroke or multiple sclerosis that initially is diagnosed as a brain tumor. "The last thing a surgeon wants to do is take out a piece of brain and find out this isn't what we thought it was," Dr. Lewin says.

For Ms. Harwell, the Texas horse trainer, it took more than a month before MD Anderson finally identified her condition. Because certain markers for ovarian cancer weren't present, doctors began to consider a form of lymphoma, although tests for that were inconclusive. Lymphoma expert Rick Hagemeister says he told Ms. Harwell the only way to get a firm diagnosis would be from a surgical biopsy of the tumors massed in her pelvis.

Ms. Harwell says gynecologic oncologist Kathleen Schmeler told her the surgery needed to be a hysterectomy, which would also be the treatment for ovarian cancer on the chance that was the problem. Seven days later, pathology reports from the procedure came back: follicular lymphoma, a rare form of the disease that would require eight rounds of chemotherapy regimen R-CHOP followed by two years of a maintenance drug, Rituxan.

Ms. Harwell says she was grateful that MD Anderson didn't begin treating her with what might have been the wrong regimen. Shortly after starting chemotherapy, Ms. Harwell showed at the Appaloosa World Show. When she took off her hat, a lot of her hair came off, too.

What to Ask When Seeking A Second Opinion:

- Have you reviewed all the materials related to my case?

- Was the lab test/image/biopsy specimen adequate to make a firm diagnosis? Would a repeat test give us more information?

- Are we certain that this is the disease that I have? Could there be another explanation for these symptoms or results?

- If you agree with the initial diagnosis, can you confirm or suggest modifications to the first doctor's proposed treatment plan?

- Can you reassure me that we have explored all the options?

New Ways for Patients to Get a Second Opinion

Online services from established medical centers and independent businesses

By Sumathi Reddy : WSJ : August 24, 2015

For many patients, it has become a routine part of the medical process: Get a diagnosis or treatment plan and then seek a second opinion.

A growing number of online services are offering second opinions and some are seeing increasing patient demand for a second set of eyes.

Some of the services are sponsored by established medical centers, including Massachusetts General Hospital and Cleveland Clinic. Others are independent businesses that work with specialists on a consulting basis. Employers increasingly are contracting with such services, and insurance companies at times require patients to get a second opinion, such as for surgery.

Studies show as much as 20% of patients seek second medical opinions; in specialties such as oncology, the rate is more than 50%. And recent research has found that second opinions often result in different diagnoses or treatments.

Second-opinion services are “one of those areas that is growing fairly quickly,” saidGregory Pauly, chief operating officer of the Massachusetts General Physician Organization at Massachusetts General Hospital. The hospital’s online second-opinion service, which started about eight years ago, handled about 10,000 cases last year compared with fewer than 1,000 five years ago, he estimated. The growing demand for second opinions, which cost between $500 and $5,000 depending on the case, has come from patients, including people from overseas, and companies that are including the service as part of employee benefits, he said.

Dr. Pauly said opinions are most often requested in areas such as cancer, neurosurgery, cardiology and orthopedics.

Patients can request their medical records be sent to an online second-opinion service, which might order additional tests if needed. The services are especially helpful for people who live far from major academic centers that cover a range of physician specialties. Many insurance policies cover in-person second opinions but don’t pay for online services unless they are offered as part of an employee’s health plan.

Some experts say patients should seek a second opinion outside of their normal institution or health-care network. “There are sometimes internal cultural approaches to treatment and it’s probably necessary for patients to go outside to get a new approach,” said F. Marc Stewart, president of the Patient Advocate Foundation, a nonprofit that helps patients access medical care. However, transferring care to another doctor can be challenging if the doctor is out of a patient’s insurance network, said Dr. Stewart, a medical oncologist and medical director of the Seattle Cancer Care Alliance.

HOW TO GET A SECOND OPINION

- Second opinions generally aren’t needed for easy-to-diagnose cases, such as sinusitis or shingles, experts say. Save second opinions for conditions where a diagnosis is unclear, involves a serious or rare condition or when treatment options are risky.

- Most doctors expect and encourage second opinions. Being open and honest with your primary physician that you want another viewpoint will help should you later need the experts to discuss your case together.

- If possible seek a second opinion from a doctor or specialist in a different institution or network. Institutional cultures are real so it’s good to get an outside and different perspective.

- Getting a second opinion that confirms the first opinion can be reassuring to patients.

- If your first and second opinions differ, consider getting a third or even fourth opinion. But getting more than that may just end up causing confusion.

- In many cases an online second opinion will suffice, although insurers generally don’t cover them unless they are included in your employee benefits. For some conditions, especially rare ones, an in-person visit is best.

For patients faced with a serious or life-threatening illness, second opinions might steer them to different treatment opportunities that are less invasive, have fewer side effects or are more targeted to their particular circumstance, said Beth Moore,executive vice president of program strategy for the Patient Advocate Foundation, “You don’t always know what’s available unless you seek a second opinion,” she said.

Ms. Moore said in-person second opinions are better in cases that may require sophisticated tests, such as with rare diseases. When two doctors have divergent recommendations, she recommends getting a third or even fourth opinion.

“Patients are often fearful that their physician will be offended” when seeking a second opinion, said Ms. Moore. “We’ve found that not to be the case. You’re going to want the experts to discuss your case in an open way once the second opinion has been issued.”

Easily diagnosed conditions, such as sinusitis or shingles, don’t call for a second opinion. But second opinions can be important when symptoms don’t go away despite treatment; when diagnosis is unclear or appears to involve a serious or rare condition; or when treatment options are risky or harmful, said Hardeep Singh, a patient safety researcher at Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center and Baylor College of Medicine in Houston.

A recent study Dr. Singh co-authored looked at data from Best Doctors Inc., an independent service that offers second opinions online to companies and insurance carriers that offer them as a benefit. The researchers reviewed 6,791 second opinions; there were changes in diagnosis 14.8% of the time and changes in treatment 37.4% of the time.

About 60% of the patients ended up following the recommendations from the second opinion, according to the study, published in April in the American Journal of Medicine. However, Dr. Singh said, “we don’t know whether the ultimate diagnosis for these patients ended up being the correct one.”

SecondOpinionExpert Inc., a website based in Dana Point, Calif., that launched this spring, says it provides second opinions for $300 and the option for a video conference consultation for an additional $200. The fees generally aren’t covered by insurance plans.

Some patients can take the process to extremes, said Mark Urman, the company’s vice president of physician relations and quality assurance. “You have to be careful, you can sometimes get too many opinions and all it does is confuse you more and then you don’t know what to do,” said Dr. Urman, who is an attending cardiologist at Cedars-Sinai Heart Institute in Los Angeles.

Dr. Urman said most of his patients who seek second opinions are those for whom he has recommended a procedure or surgery that is elective. When a patient comes to him for a second opinion, about 75% of the time his opinion will be similar to the previous doctor, he said.

Cleveland Clinic set up an online second-opinion service, MyConsult, more than a decade ago. In recent years, the number of patients served has grown 15% to 25% a year, boosted especially with patients who live far from the clinic and with corporate clients. MyConsult charges $565 for a consultation and $745 if it includes a pathology review.

Cleveland Clinic doctors who review cases disagree with the original diagnosis about 11% of the time, said Jonathan Schaffer, managing director of MyConsult and an orthopedic surgeon. They make moderate changes to treatment in 24% of cases and major changes in 16% of cases. “These numbers can have some pretty significant health-care implications,” said Dr. Schaffer.

Linda Smith, a 67-year-old in New Albany, Ohio, was diagnosed last year with a precancerous lump in her breast. She had it surgically removed and underwent five weeks of radiology treatments. When her doctor then recommended she take a chemotherapy pill, Ms. Smith sought a second opinion through Cleveland Clinic’s MyConsult, which was included in her employee health insurance.

The MyConsult pathologists determined Ms. Smith had had a different type of precancerous lump than was originally diagnosed, she said. They told her she hadn’t needed the five weeks of radiology treatments.

To resolve the conflicting viewpoints, Ms. Smith sought a third opinion, not covered by her insurance, that concurred with the MyConsult diagnosis. “I missed all this work and I missed this key training,” said Ms. Smith, a design engineer for a telecommunications company.

Ms. Smith said in the future she will always seek additional medical opinions, even if she has to pay for it. “Doctors make mistakes and medicine is always changing,” she said.