- RETIREMENT ANNOUNCEMENT

- HOME PAGE

- "MYCHART" the new patient portal

- BELMONT MEDICAL ASSOCIATES

- MOUNT AUBURN HOSPITAL

- EMERGENCIES

- PRACTICE PHILOSOPHY

- MY RESUME

- TELEMEDICINE CONSULTATION

- CONTACT ME

- LAB RESULTS

- ePRESCRIPTIONS

- eREFERRALS

- RECORD RELEASE

- MEDICAL SCRIBE

- PHYSICIAN ASSISTANT (PA)

- Medicare Annual Wellness Visit

- Case management/Social work

- Quality Care Measures

- Emergency closing notice

- FEEDBACK

- Talking to your doctor

- Choosing..... and losing a doctor

- INDEX A - Z

- ALLERGIC REACTIONS

- Alternative Medicine

- Alzheimer's Disease

- Bladder Problems

- Blood disorders

- Cancer Concerns

- GENETIC TESTING FOR HEREDITARY CANCER

- Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

- Controversial Concerns

- CPR : Learn and save a life

- CRP : Inflammatory marker

- Diabetes Management

- Dizziness, Vertigo,Tinnitus and Hearing Loss

- EXERCISE

- FEMALE HEALTH

-

GASTROINTESTINAL topics

- Appendicitis

- BRAT diet

- Celiac Disease or Sprue

- Crohn's Disease

- Gastroenterologists for Colon Cancer Screening

- Colonoscopy PREP

- Constipation

- Gluten sensitivity, but not celiac disease

- Heartburn and GERD

- Hemorrhoids and Anal fissure

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- NASH : Non Alcoholic Steato Hepatitis

- FEET PROBLEMS

- HEART RELATED topics

-

INFECTIOUS DISEASES

- Antibiotic Resistance

- Cat bites >

- Clostridia difficile infection - the "antibiotic associated germ"

- CORONA VIRUS

- Dengue Fever and Chikungunya Fever

- Food borne illnesses

- Shingles Vaccine

- Hepatitis B

- Hepatitis C

- Herpes

- Influenza

- Helicobacter pylori - the "ulcer germ"

- HIV Screening

- Lyme and other tick borne diseases

- Measles

- Meningitis

- MRSA (Staph infection)

- Norovirus

- Sexually Transmitted Diseases

- Shingles (Herpes Zoster)

- Sinusitis

- West Nile Virus

- Whooping Cough (Pertussis)

- Zika virus and pregnancy

- INSURANCE related topics

- KIDNEY STONES

- LEG CRAMPS

- LIBRARY for patients

- LIFE DECISIONS

- MALE HEALTH

- Medication/Drug side effects

- MEDICAL MARIJUANA

- MENTAL HEALTH

- Miscellaneous Articles

-

NUTRITION - EXERCISE - WEIGHT

- Cholesterol : New guidelines for treatment

- Advice to lower your cholesterol

- Cholesterol : Control

- Cholesterol : Raising your HDL Level

- Exercise

- Food : Making Smart Choices

- Food : Making Poor Choices

- Food : Grape Fruit and Drug Interaction

- Food : Vitamins, Minerals and Supplements

- Omega 3 fatty acids

- Vitamin B12 deficiency

- Vitamin D

- Weight Loss

- ORTHOPEDICS

- PAIN

- PATIENTS' RIGHTS

- SKIN

- SLEEP

- SMOKING

- STROKE

- THYROID

- SUBSTANCE ABUSE

- Travel and Vaccination

- TREMOR

- Warfarin Anticoagulation

- OTHER STUFF FOLLOWS

- Fact or Opinion?

- Hippocratic Oath

- FREE ADVICE.......for what its worth!

- LAUGHTER.....is the best medicine

- Physicians Pet Peeves

- PHOTO ALBUM - its not all work!

- Cape Town, South Africa

- Tribute page

- The 100 Club

- Free Wi-Fi

Prostate Health

Diet and your prostate

An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.

Men who are more interested in preventing prostate cancer than treating it, should make sure that their diet is low in animal fat and includes plenty of lycopenes. These are consumed in the form of cooked tomatoes, as well as garlic, scallions, chives and other vegetables in the alium family.

Vitamin D (in a supplement and from sunlight), Vitamin E (in salad oils, legumes and nuts), pomegranate juice, Selenium and Saw Palmetto are also useful dietary supplements.

Now here is the "bad" news: A new study suggests that eating lycopene-rich tomatoes offers no protection against prostate cancer, contrary to the findings of some past studies. In fact, the researchers found an association between beta carotene, an antioxidant related to lycopene, and an increased risk of aggressive prostate cancer!

Benign Prostatic Hypertrophy

5 Things to Know: B.P.H.

By Gerald Secor Couzen : NY Times Article : April 11, 2008

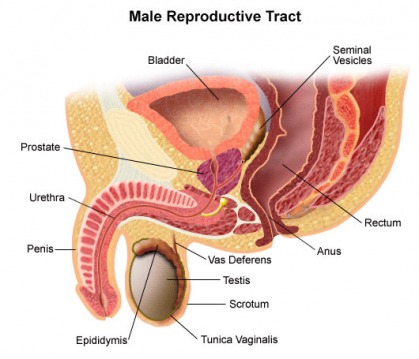

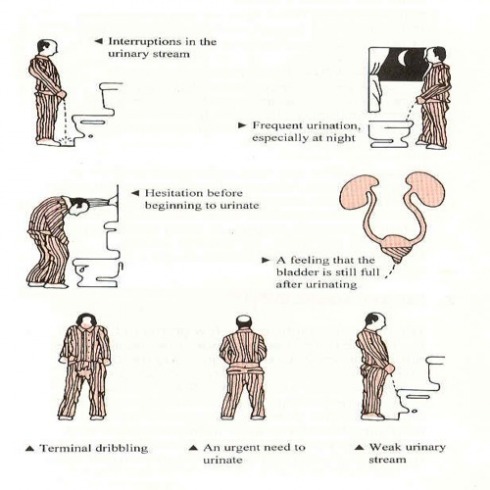

Once a man passes the half-century mark, it’s not uncommon to experience such bothersome lower-urinary-tract symptoms as frequent urination throughout the day, getting up at night multiple times to urinate or a weak urinary stream. These symptoms are often caused by an enlarged prostate, a condition known as B.P.H., for benign prostatic hyperplasia. As the prostate grows in size, pressure is placed on the urethra, the tube transporting urine from the bladder through the prostate, and this can lead to a host of urinary complaints. Here are five things Dr. Franklin C. Lowe, a professor of urology at Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, believes that every man with B.P.H. should know.

1. B.P.H. is not prostate cancer.

Don’t be afraid if your doctor has told you that your prostate is enlarged and that you have benign prostatic hyperplasia. “Benign” means your prostate is not cancerous. “Prostatic” refers to your prostate, the walnut-size gland below your bladder. “Hyperplasia” means an excessive formation of cells. B.P.H., the noncancerous enlargement of your prostate, is the most common tumor found in men.

2. Symptoms.

Before deciding on a course of treatment, ask yourself how bothered you are by symptoms. Are you losing sleep because of multiple nocturnal awakenings to go to the bathroom? If not, and if symptoms are not worsening, you may not have to do anything. Remember, however, symptoms often worsen over time. The International Prostate Symptoms Score, a seven-question guide for determining the severity of symptoms, is an excellent self-assessment. Scores of 0 to 7 are considered mild, 8 to 19 indicate moderate problems and 20 to 35 mean symptoms are severe.

3. Medications.

Some men find temporary relief with saw palmetto capsules or by reducing their daily fluid intake and avoiding alcohol and caffeinated beverages. A variety of prescription B.P.H. medications are available. While no prescription drug offers a cure, they ease symptoms in more than 60 percent of men.

4. Outpatient heat therapies.

Within a year of starting prescription drug therapy for B.P.H., one-third of men discontinue medications due to lack of efficacy, bothersome side effects or cost. Minimally invasive heat treatments, in which extreme heat is applied to destroy excess prostate tissue, include transurethral needle ablation of the prostate (TUNA), transurethral electrovaporization of the prostate (TUVP), transurethral microwave therapy (TUMT) and water-induced thermotherapy (WIT). These treatments are generally safe and effective but may need to be repeated every five years or so.

5. TURP, the “gold standard.”

If B.P.H. symptoms have not improved with other therapies, laser therapy can be used during an outpatient procedure to vaporize prostate tissue. If your problems are severe, your doctor may recommend a transurethral resection of the prostate, or TURP, a surgical procedure that effectively relieves symptoms and rarely requires a second treatment.

For Men, Relief in Sight

By Gerald Secor Couzens : NY Times Article : May 13, 2008

MEN, the joke goes, spend the first half of their lives making money and the second making water. That is because after age 50 many men face an embarrassing problem called B.P.H., for benign prostatic hyperplasia. This slowly progressive enlargement of the prostate can make urination difficult or painful and send men trudging to the bathroom many times during the day and night.

Though bothersome, B.P.H. is not life threatening. Nor does it lead to cancer. When left untreated, however, B.P.H. can lead to serious health problems for some.

“My father used to be up 10 times a night and said it wasn’t a problem for him,” said Dr. Franklin C. Lowe, professor of urology at Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons. “However, he developed urinary tract infections annually because of his B.P.H. and almost died from sepsis one year. Surprisingly, his case is not unique.”

Many doctors are now urging men to become proactive earlier to prevent chronic problems in the future. Bladder stones, infections and bladder or kidney damage can arise and sometimes require surgery. Urological experts are beginning to rethink treatments, too, based on symptoms and how much a man is bothered by them.

“There is a big difference between having the symptoms and being bothered by the symptoms,” said Dr. Kevin T. McVary, professor of urology at the Feinberg School of Medicine at Northwestern University. “Some men go to the bathroom several times a night, get right back to sleep and are not bothered,” he said. Watchful waiting, or monitoring symptoms while holding off on medical or surgical treatments, is a reasonable plan for these men, he added. But for patients who have trouble getting back to sleep, “there are many effective options, and patients almost always end up with less bothersome symptoms once they choose to do something,” he said.

Although no drug offers a cure, “many men can be managed nicely with medical therapy,” Dr. Lowe said. The latest thinking is that combination therapy — taking both of the two main types of B.P.H. drugs — achieves maximum benefit. Alpha blockers like Flomax, Uroxatral, Hytrin and Cardura relax muscle fibers in the bladder and prostate. Other drugs like Proscar and Avodart, called 5-alpha-reductase inhibitors, shrink the prostate over 9 to 18 months. Once the drugs are stopped, however, symptoms typically recur. Researchers are also exploring the use of erectile dysfunction drugs for men with erection problems and B.P.H. as well as the antiwrinkle drug Botox.

There are also minimally invasive B.P.H. therapies that use heat, ultrasound, microwaves, low-frequency radio waves or lasers to hollow out the prostate’s core and relieve the pressure on the urethra that is reducing urine flow. These outpatient procedures have a long-lasting effect, although many men need an additional procedure within five years, and some even sooner.

“I tell patients, If you have to go through one procedure for your prostate, make sure it is one that will give long-lasting results,” Dr. Lowe said. He recommends the transurethral resection of the prostate. This “gold standard” surgery, performed under anesthesia, involves removing excess prostate tissue with an instrument inserted through the penis. It can offer relief for 10 years or more.

Robert H. Getzenberg, professor of urology at the Johns Hopkins Brady Urological Institute in Baltimore, notes that many men with B.P.H. are surprised to find that their urinary symptoms persist even after cancer surgery to remove the prostate. “People used to think that B.P.H. was just a disease of the prostate, and that’s not entirely true,” he said. “That’s because the prostate is only one component of B.P.H. The bladder, as we have found out, is another.”

Over time, he adds, the bladder may respond to changes in urinary patterns and pressure by becoming thicker and less resilient. When that occurs, a man feels as if he has to urinate more often, and the prostate problem has become a bladder issue.

Dr. Getzenberg believes there is more than one type of B.P.H., and that each requires different treatment. “There is the common B.P.H. found in most men as they age,” he said. “Urinary symptoms are mild and less likely to lead to bladder and other urinary tract damage.” A more severe form of B.P.H. is not always benign. “It’s highly symptomatic and has increased risk of damage to the bladder,” he added.

Genetic tests may eventually give men answers that will lead to better treatment of their condition. “If we can differentiate men into different groups, we can treat this disease more efficiently and effectively,” Dr. Getzenberg said. “This will allow us to intervene much earlier in the disease process.”

Rethinking an Old Ailment: Enlarged Prostate

By Gerald Secor Couzens : NY Times Article : April 11, 2008

Prostate cells in benign prostatic hyperplasia show excessive growth but are not cancerous; they have characteristics of healthy prostate cells, like the uptake of the mineral zinc (arrows).

IN BRIEF

Although no drug offers a cure, “many men can be managed nicely with medical therapy,” Dr. Lowe said. The latest thinking is that combination therapy — in which men take both of the two main types of B.P.H. drugs — achieves maximum benefit. Alpha-blockers like Flomax, Uroxatral, Hytrin and Cardura relax muscle fibers in the bladder and prostate. Other drugs like Proscar and Avodart, called 5-alpha-reductase inhibitors, shrink the prostate over 9 to 18 months. Once the drugs are stopped, however, symptoms typically recur. Researchers are also exploring the use of erectile dysfunction drugs for men with erection problems and B.P.H. as well as the antiwrinkle drug Botox.

There are also minimally invasive, nonsurgical B.P.H. therapies that use heat, ultrasound, microwaves, radiofrequency or lasers to hollow out the prostate’s core and relieve the pressure on the urethra that is reducing urine flow. These 30-to-60-minute outpatient procedures are long lasting, although many men need an additional procedure within five years, some even earlier.

“I tell patients, ‘If you have to go through one procedure for your prostate, make sure it is one that will give long-lasting results,’ ” Dr. Lowe said. He recommends the TURP, for transurethral resection of the prostate. This “gold standard” surgery, performed under anesthesia, involves removing excess prostate tissue via an instrument inserted through the penis. It requires an overnight hospital stay but can offer relief for 10 years or more.

Robert H. Getzenberg, professor of urology at the Johns Hopkins Brady Urological Institute in Baltimore, notes that many men with B.P.H. are surprised to find that their urinary symptoms persist even after cancer surgery to remove the prostate. “People used to think that B.P.H. was just a disease of the prostate, and that’s not entirely true,” he said. “That’s because the prostate is only one component of B.P.H. The bladder, as we have found out, is another.”

Over time, he notes, the bladder may respond to changes in urinary patterns and pressure by becoming thicker and less resilient. When that occurs, a man feels as if he has to urinate more frequently. What started as a prostate problem has become a bladder issue.

Dr. Getzenberg believes there is more than one type of B.P.H. and that each requires a different treatment approach. “There is the common B.P.H. found in most men as they age,” he said. “Urinary symptoms are mild and less likely to lead to bladder and other urinary tract damage.” A second, more severe form of B.P.H. isn’t always benign. “It’s highly symptomatic and has increased risk of damage to the bladder,” he added.

He has developed a genetic blood test called JM-27 that detects about 90 percent of men with the severe form of B.P.H. “It has nothing to do with the size of a man’s prostate or the presence or risk of prostate cancer,” Dr. Getzenberg said. “If we can differentiate men into different groups, we can treat this disease more efficiently and effectively. This will allow us to intervene much earlier in the disease process instead of trying to treat B.P.H. in its severe form.”

Veteran urologists who have seen dozens of promising tests and procedures ultimately fail when put through rigorous testing are naturally skeptical. “JM-27 is a great concept, but it’s too early to draw conclusions,” Dr. Lowe said.

Questions and answers from Dr. Kevin T. McVary

Q. Are you happy with the current drugs for B.P.H.?

A. Yes and no. I am very happy that we have medical therapies for B.P.H. Many patients get relief of their symptoms from the various drugs. However, if you look at the drugs objectively, the response is relatively modest. Medications, which have to be taken daily and indefinitely, just don’t work as well as minimally invasive heat therapies, laser therapy or TURP.

Q. Does B.P.H. improve without any therapy?

A. If you look at some of the observation studies, enlarged prostate symptoms will fluctuate. About half of the men will note improvement in their symptoms to an appreciable degree over the course of a year, so watchful waiting in the early stages is certainly a reasonable choice. Steady improvement is not inevitable, however.

Q. What do you think of the herb saw palmetto as a B.P.H. therapy?

A. For the past 100 years, saw palmetto has been a favorite treatment for B.P.H. While many of my patients swear on a stack of bibles that it helps them, I’d be a rich man if I got a nickel for every one that had no luck with this over-the-counter therapy. A 2006 study of 225 men with moderate to severe B.P.H. was published in The New England Journal of Medicine. The men were randomly assigned to take either a saw palmetto extract or a placebo daily for a year. At the end of the study, the researchers found no differences between the groups in their prostate symptom scores or quality of life.

Q. What novel therapies for B.P.H. are now being tested?

A. Treatment of B.P.H. has relied on alpha-blocker medication (similar to what is prescribed for hypertension) and 5-alpha reductase inhibitors, oral medications that cause the prostate gland to shrink over time, improving urinary symptoms in the process. When these drugs are taken in combination, two-thirds of the men who take them get relief of symptoms.

However, as our understanding of the prostate and the entire lower urinary tract system increases, several novel B.P.H. approaches are being explored. In the future, the B.P.H. armamentarium may include drugs similar to that we now use for erectile dysfunction. In addition, Botox, originally developed from a deadly toxin to cure a rare eye condition and now used as a wrinkle remover, may also be used if clinical studies prove its worth as an effective B.P.H. therapy.

Q. Can Viagra and other erectile dysfunction medications help men with B.P.H.?

A. In the last few years, it has become obvious that men suffering from lower urinary tract symptoms and E.D. seemed to be the same men. We used to look at these ailments in aging men as separate diseases occurring in the same people by coincidence. We are now realizing that B.P.H. and E.D are linked somehow. One disease process may be causing both E.D. and B.P.H. symptoms.

In my erection drug study that I reported at the annual meeting of the American Urological Association in 2007, I described how 369 men with erectile dysfunction and B.P.H. were randomized to receive either placebo or 50 milligrams of Viagra a day for 12 weeks. The medication was taken before bedtime and an hour before sexual activity. Over all, after Viagra treatment, patients with severe B.P.H. at the start of the study experienced a greater improvement (73 percent) in urinary symptoms. More than 55 percent of the men improved to moderate B.P.H. levels, and 16 percent improved to mild levels.

The magnitude of improvement in International Prostate Symptom Scores for men with moderate to severe complaints appeared to be comparable to that achieved with alpha-blockers and 5-alpha reductase inhibitors.

We know that 30 percent of patients discontinue alpha-blocker medication for their B.P.H. within the first 12 months due to adverse side effects or nonresponse. I see the E.D. medications as potentially new agents for treating lower urinary tract symptoms. The erection drugs not only work as an effective form of therapy for lower urinary complaints, but they offer a nice side effect: improved erections. In the future, we may not use Viagra, Cialis and Levitra for urinary complaints, but rather new formulations of these drugs that are geared to specifically influence the bladder and prostate.

Right now, these drugs are used off label by early adopters, urological researchers and physicians frustrated by nonresponse to other medical therapy from their patients.

Q. Why do erectile dysfunction drugs seem to help men with B.P.H.?

A. No one knows for sure, but there are several plausible explanations. One is the influence of the drugs at the bladder level. In addition to the penis, the bladder muscles also have very high activity levels of phosphodiesterase 5 (P.D.E.-5), and so does the prostate. What the erection drugs Viagra, Levitra and Cialis do is block the P.D.E.-5, preventing the enzyme from breaking down nitric oxide, which is needed to dilate blood vessels. Not only are the penile arteries relaxed by the medication, which allows blood to flow into the penis, but these drugs might also cause small blood vessels in the prostate and bladder to dilate, improving urinary symptoms in the process.

Another plausible idea is that these medications may affect neurotransmission in the spinal cord. Even though urination flow rates may not change, the men’s perception of urgency and bother may be altered by the impact of the drug on the central nervous system.

A final cause for improvement in B.P.H. from the E.D. drugs could be that older men with lower urinary complaints have nerve signals to the brain, bladder and prostate that are acting inappropriately. The erection drugs might help mute the erratic signals and therefore improve B.P.H. symptoms.

Q. Can Botox be used to help men with B.P.H.?

A. Although most people think of Botox (botulinum toxin type A) as a wrinkle remedy, it may also play a significant role in the near future as an effective B.P.H. remedy. I have done several studies with the medication, and many of the patients I have treated have had a quick and significant response to the drug.

The Botox injection is performed under ultrasound guidance to help guide the needle to the prostate. Within eight days, many of my study subjects were able to stop all B.P.H. medications. In addition, they saw a drop in their International Prostate Symptom Scores by as much as 50 percent. There don’t appear to be any side effects when the drug is used for B.P.H. therapy.

Q. How does Botox improve B.P.H. symptoms?

A. Botox injections work by weakening or paralyzing certain muscles or by blocking certain nerves. It’s not clear how Botox actually works in the prostate, but it appears that after the injection, the prostate gland undergoes an almost immediate involution; it shrinks down. This reduction in size can improve urine flow and decrease residual urine left in the bladder.

This is a fascinating product for B.P.H., and Botox injected into the prostate seems to be a promising approach that could represent a simple, safe and effective treatment for an enlarged prostate. Currently, however, Botox is not approved by the Food and Drug Administration for this use.

Questions you can ask your doctor:

PSA : Prostate Specific Antigen Testing

Deciphering the Results of a Prostate Test

By Jane E Brody : NY Times Article : May 8, 2007

After his annual physical, a middle-age man is told that his PSA level has jumped to 2.3 after having been stable for years at 1.5. Should he be alarmed?

Maybe and maybe not. The PSA test, as few men older than 40 need to be told, is widely used as a screening tool for prostate cancer. But the test is controversial, and for good reason.

For one thing, the cancer itself is highly variable. As many as 15 percent of 50-year-old men will be given diagnoses of prostate cancer over the next 30 years. But 1.4 percent will die of the disease in that time, a 10-fold difference that shows that the cancer is usually not fatal. By age 85, more than three-fourths of men have evidence of prostate cancer; many have lived with the disease for more than 10 years.

In addition, PSA levels often fluctuate as much as 30 percent for unknown reasons and can increase for reasons other than cancer, challenging physicians who have to determine how to proceed when a man’s PSA level goes up.

“There’s a lot of background noise” associated with PSA testing, said Dr. Peter T. Scardino, chief of urology at the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York and author of “Dr. Peter Scardino’s Prostate Book” (Penguin, 2005). Still, as evidence of the value of the test, he noted that the United States has since 1992 recorded a 30 percent decline in age-specific mortality from prostate cancer, “despite no dramatic new therapy for advanced disease.”

Factors Behind the Measurement

PSA stands for prostate-specific antigen, a substance produced only by the prostate gland and found in the ejaculate. Its purpose is to liquefy the semen to release sperm, freeing them to fertilize an egg. The PSA level, measured in nanograms per milliliter of blood, reflects how much of this antigen is being produced and released into the bloodstream. The larger a man’s prostate, the more PSA is produced, which makes the test very confusing in older men with benign enlargement of this gland.

Aside from cancer and prostatic growth with age, factors that can change PSA measurements include inflammation or infection of the prostate; a decline in testosterone levels or the drug finasteride, taken for hair loss, both of which lower the PSA; and variations in laboratory assays and in the inherent biology of a person. Biological variability can result in as much as a 15 percent difference between readings, and in nearly half of men with an abnormal PSA, the test will normalize in one to four years without any treatment.

But Dr. H. Ballentine Carter, a urologist at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, notes that no significant changes in PSA result from recent sexual intercourse or ejaculation, a digital rectal examination or riding a bicycle. “Even long-distance bikers do not have prostate trauma” that causes their PSA to increase, Dr. Carter said.

Current guidelines recommend that all men have an annual PSA test starting at age 50 and that biopsies be conducted if the level exceeds 4 or if a “significant rise” occurs between two tests. The guidelines also suggest limiting screening to men with more than a 10-year life expectancy.

This approach has resulted in many biopsies in men who did not have cancer — about 70 percent of those with elevated PSAs are cancer free — and debilitating prostate surgery in men with cancers that would never have become a threat in their remaining years of life.

On the Way: New Guidelines

Based on recent studies, the American Urological Association will soon release revised guidelines that, experts hope, will reduce unnecessary biopsies and prostate surgeries, which even in the best hands can leave a man impotent and incontinent. The revised guidelines are expected to reduce the cost of screening, the cost per life saved and overall deaths from prostate cancer.

The new guidelines will no longer rely on a single reading. Rather, they will suggest that doctors focus on changes in levels over time. They will also suggest that testing start at 40 to obtain a baseline measurement, with the test repeated at 45 and 50, after which it should be given annually until 70.

“If a 70-year-old man has a PSA history that hasn’t changed over the years, maybe he doesn’t need further testing,” Dr. Carter suggested. “PSA testing of men over 70 is not rational.”

He pointed to a Scandinavian study showing that among men older than 65, to prevent one death from prostate cancer over 10 years, 330 men would have to have prostate surgery.

“This has created a huge dilemma in urology,” Dr. Carter said. “We don’t want to miss the possibility of a life-threatening disease, but we end up diagnosing and treating disease that would never have caused harm.”

The new guidelines will lower the PSA level at which a biopsy should be considered, because, as Dr. Carter put it, “there’s no level below which we can tell a man he doesn’t have prostate cancer or life-threatening prostate cancer.”

As one important trial showed, among men with a very low PSA — that is, a reading below the current cutoff of 4 — biopsies found that 15 percent had prostate cancer. Among that 15 percent, Dr. Carter said, 15 percent had high-grade, potentially life-threatening cancers. That means that 2.25 percent of the total number of men with a PSA less than 4 had life-threatening cancers.

But, he added, “If we biopsied every man with a PSA below 4, we’d be looking at a sea of cancers that would never grow to be life threatening.”

Getting Enough Data

These facts and the results of a recent study by Dr. Carter, among others, indicated that rather than acting on the basis of a single PSA test, the rate of change in levels over time is a better indicator of who might have a serious cancer. This rate, known as PSA velocity, will be part of the new guidelines, which will suggest that in men with low readings, doctors consider the changes in levels over the course of three measurements.

“We need at least 1 ½ to 2 years’ worth of data” to make a meaningful judgment about how to proceed, Dr. Carter said.

He explained that in men with an initially high level — say 10 or higher— velocity is not an issue. For them, if other factors like prostate infection are not the cause of the high level, a biopsy is in order. But in men with a PSA from 0 to 4, knowing the velocity of changes can add useful information, he said.

Another approach to assessing the meaning of a PSA reading is to analyze how much antigen is traveling free in the blood and how much is bound to a companion protein, Dr. Scardino suggested. If more than 25 percent of the PSA is free, chances are that it is being produced by a benignly enlarged prostate. The lower the amount of free PSA, the more likely cancer is the cause and the more likely the disease is aggressive, requiring treatment, according to Dr. Patrick C. Walsh, a Johns Hopkins urologist and the author of “Dr. Patrick Walsh’s Guide to Surviving Prostate Cancer.”

Inappropriate PSA screening :

Not really indicated in elderly men especially those with multiple illnesses. Can do more harm than good.

Many elderly men are getting screened for prostate cancer unnecessarily, according to researchers from the San Francisco VA Medical Center.

In a study of nearly 600,000 men aged 70 and older who had been seen at dozens of VA hospitals across the United States, the research team found high rates of inappropriate PSA testing, even among men with multiple illnesses who were unlikely to survive more than 10 years.

The older a man is, the more likely he is to develop prostate cancer. At the same time, however, the older the man, the more likely he is to die of something else before the prostate cancer can even begin to cause symptoms.

And while the cancer itself might never cause symptoms, the treatment for it may. Treatments for prostate cancer can lead to serious side effects like incontinence, impotence, and bowel function problems, which can severely reduce quality of life. That's one reason no national organization recommends prostate cancer screening for men with a life expectancy of less than 10 years.

The American Cancer Society recommends doctors discuss the risks and benefits of yearly screening beginning at age 50 (or younger for men at high risk of the disease) with men who have at least a 10-year life expectancy.

Anxiety and Worse

The study findings suggest many men are being subjected to unnecessary anxiety about test results and a cancer diagnosis, unneeded diagnostic procedures, and potential side effects of prostate cancer treatment, says lead researcher Louise C. Walter, MD, a staff physician at the San Francisco VA Medical Center and assistant professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco.

"I've seen it happen to my patients," explains Walter a geriatrician. "They get very worried and get procedures done to them that leave them incontinent and impotent for a disease that I thought wasn't going to cause them major problems."

Other experts agree the findings are cause for concern. Several studies suggest that men over 70 or 75 can indeed suffer because of the procedures used to diagnose and treat prostate cancer, notes Andrew Wolf, MD, assistant professor of medicine at the University of Virginia Health System and a member of the ACS Primary Care Advisory Committee.

"There's a good chance a lot of these men are being harmed," adds Wolf, who was not involved in the study.

Overall, 56% of the men in the study group had PSA testing done during the year, although none of them had a history of prostate cancer, elevated PSA, or symptoms of the disease that would give a medical reason for such testing. PSA screening rates did go down with age, but not as much as the researchers expected.

And the decline in screening did not necessarily correspond to worsening health. Among men 85 and older, for instance, 34% of those in "best health" (those with the fewest other illnesses or limitations) got PSA tests, compared to 36% of those in "worst health." The study did not examine how many of the men may have requested the test, as opposed to their doctor just ordering it for them.

The results were published in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

Other Conditions More Important

Overzealous screening can steal valuable time from more pressing medical concerns such as dementia, congestive heart failure, dialysis, oxygen dependency, and functional limitations, Walter notes.

"You put any of those [conditions] with [age] 85 and above and you do wonder why you'd be getting a PSA test," she says.

Better guidance for estimating a man's life expectancy could help doctors avoid unnecessary prostate cancer screening, she adds.

Physicians need to have frank discussions with their elderly male patients about the pros and cons of prostate cancer screening, Walter and Wolf agree.

"I simply explain to them that prostate cancer is one of those areas where oftentimes in the elderly the cure is worse than the disease," Wolf says. "While it's only a blood test or rectal exam or both, it leads rapidly to other testing and interventions that have serious downstream effects -- like death, incontinence, or complications from surgery and radiation -- that, being older, they're much more susceptible to."

Some men will choose to be screened regardless of the risks, Walter acknowledges. But when that happens, "I do make sure they understand that there are downsides and that it's not just a blood test," she says.

Citation: "PSA Screening Among Elderly Men With Limited Life Expectancies." Published in the Nov. 15, 2006, Journal of the American Medical Association (Vol. 296, No. 19: 2336-2342). First author: Louise C. Walter, MD, San Francisco VA Medical Center.

Simplifying the Decision for a Prostate Screening

By Tara Parker-Pope : NY Times : September 27, 2010

One of the most difficult decisions a man makes about prostate cancer happens long before the diagnosis. Should he get a regular blood test to screen for the disease?

Screening for early detection of cancer sounds like a no-brainer, but it’s not an easy choice for men considering regular P.S.A. tests, which measure blood levels of prostate-specific antigen and are used to detect prostate cancer. Though use of the test is widespread, studies show that the screening saves few, if any, lives.

While the test helps find cellular changes in the prostate that meet the technical definition of cancer, they often are so slow-growing that if left alone they will never cause harm. But once cancer is detected, many men, frightened by the diagnosis, opt for aggressive surgical and radiation treatments that do far more damage than their cancers would have, leaving many impotent and incontinent.

As a result, major health groups don’t advise men one way or the other on regular P.S.A. screenings, saying it should be a choice discussed between a man and his doctor.

So how does a man decide whether to get P.S.A. screening or not? Finally, some new research offers simple, practical advice — at least for men 60 and older.

Researchers at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York and Lund University in Sweden have found that a man’s P.S.A. score at the age of 60 can strongly predict his lifetime risk of dying of prostate cancer, according to a new report in the British medical journal BMJ.

The findings also suggest that at least half of men who are now screened after age 60 don’t need to be, the study authors said.

The researchers followed 1,167 Swedish men from the time they were 60 years old until they died or reached 85. During that time, there were 43 cases of advanced prostate cancer and 35 deaths in the group. The researchers found that having had a P.S.A. score of 2.0 or higher at the age of 60 was highly predictive of developing advanced prostate cancer, or dying of the disease, within the next 25 years.

About one in four men will have a P.S.A. score of 2.0 or higher at the age of 60, and most of them will not develop prostate cancer, said the study’s lead author, Andrew Vickers, associate attending research methodologist at Memorial Sloan-Kettering. But the score does put them in a higher-risk group of men who have more to gain from regular screening, he concluded.

The higher the score at age 60, the greater the long-term risk of dying from prostate cancer, Dr. Vickers and his colleagues found. Men with a score of 2.0 or higher at age 60 were 26 times more likely to eventually die of the disease than 60-year-old men with scores below 1.0.

Still, the absolute risks for men with elevated scores were lower than might be expected. A 60-year-old man with a P.S.A. score just over 2.0 had an individual risk of dying from prostate cancer during the next 25 years of about 6 percent, the researchers found. A 60-year-old man with a P.S.A. score of 5 had about a 17 percent risk.

“Most of those men are going to be absolutely fine,” said Dr. Vickers. “But they can be told they are at high risk and they need screening.”

Men with a P.S.A. score of 1.0 or lower at age 60 had a very low individual risk of death from prostate cancer over the next 25 years, the study found: just 0.2 percent.

“They can be reassured that even if they have prostate cancer or get it, it’s unlikely to become life-threatening,” said Dr. Vickers. “There’s a strong case that they should be exempted from screening.”

The advice is less clear for men with scores between 1.0 and 2.0 at the age of 60. They still have a very low individual risk of dying from prostate cancer, judging from the new data. The long-term risk of dying from prostate cancer ranged from about 1 percent to 3 percent for these men, and the decision to screen may depend on their personal views and family histories, Dr. Vickers said.

While the findings don’t answer all of the questions associated with P.S.A. screening, they should give peace of mind to sizable numbers of men who decide not to continue regular testing. The results also will reassure men who decide to continue with regular screenings that the benefits most likely outweigh the risks.

Dr. Eric A. Klein, chairman of the Glickman Urological and Kidney Institute at the Cleveland Clinic, said that he would like to see the findings of the new study independently confirmed, but that other studies also have suggested that the risk of cancer is low in men whose P.S.A. levels remain below 1.5 in their 50s and 60s.

“We are in the midst of a paradigm shift in screening and risk assessment that no longer relies on a simple P.S.A. cutoff to determine who should be biopsied,” Dr. Klein said.

P.S.A. screening is already not advised for those 75 and older, because the slow-moving nature of the disease means that a vast majority of men at that age are likely to die from something other than a newly detected prostate cancer. A major study last year confirmed that P.S.A. testing is not helpful for men with 10 years or less of life expectancy.

But the advice continues to be murky for younger men. In a large European study reported last year, 50- to 54-year-olds didn’t benefit from screening. But men ages 55 to 69 who had annual P.S.A. testing were slightly less likely to die from prostate cancer than those who weren’t screened.

The researchers who conducted the latest study also have investigated whether a man’s P.S.A. score at 50 can predict his long-term risk. In a 2008 report of 21,000 men published in the journal BMC Medicine, the researchers found that two-thirds of the advanced cancer cases that developed over 25 years were in men who had a P.S.A. score of 0.9 or higher at the age of 50.

Those findings can help younger men decide how intensely they want to screen for the disease. A man whose P.S.A. test shows him to be at low risk at age 50 may decide not to be retested again until the age of 60. A man with a higher score may want to do more frequent testing.

“We haven’t solved every single problem with screening,” Dr. Vickers noted. “We need to screen fewer people, screen the right people, and we don’t have to treat every cancer we catch.”

New Take on a Prostate Drug, and a New Debate

By Gina Kolata : NY Times Article : June 15, 2008

For the first time, leading prostate cancer specialists say, they have a drug that can significantly cut men’s risk of developing the disease, dropping the incidence by 30 percent.

But the discovery, arising from a new analysis of a large federal study, comes with a debate: Should men take the drug?

Prostate cancer is unlike any other because it is relatively slow-growing and while it can kill, it often is not lethal. In fact, most leading specialists say, a major problem is that men are getting screened, discovering they have cancers that may or may not be dangerous, and opting for treatments that can leave them impotent or incontinent.

So should healthy men take a drug for the rest of their lives to avoid getting and being treated for a cancer that, most often, would be better off undiscovered and untreated? Is it worth risking a chance that unanticipated side effects may emerge years later if millions of men with no prostate problems take the drug?

Some prostate cancer experts say the answer is yes. Any man worried enough about prostate cancer to be screened might consider it, they say.

The drug, finasteride, is available as a generic for about $2.00 a day, and millions of men safely take it now to shrink their prostates, its approved use.

With finasteride, as many as 100,000 cases of prostate cancer a year could be prevented, said Dr. Eric Klein, director of the Center for Urologic Oncology at the Cleveland Clinic.

Dr. Howard Parnes, chief of the prostate cancer group at the National Cancer Institute’s division of cancer prevention, also is convinced. “There is a tremendous public health benefit for the use of this agent,” he said.

While it might seem convoluted to offer a drug to prevent the consequences of overtreatment, that is the situation in the country today, others say. Preventing the cancer can prevent treatments that can be debilitating, even if the cancers were never lethal to start with.

“That’s the bind we’re in right now,” said Dr. Christopher Logothetis, professor and chairman of genitourinary medical oncology at M.D. Anderson Cancer Center. “Most of the time, treatment wouldn’t help and may not be necessary. But the reality is that people are being operated on.”

“We are trying to avoid a diagnosis to avoid a prevention whose value is disputed,” he said. With finasteride, Dr. Logothetis added, “we’re trying to overcome our other sins.”

Other experts say, Not so fast. Finasteride might not make much of a difference in the death rate because so few men die from prostate cancer. What the drug’s proponents are advocating is taking a drug to somehow compensate for what many believe is the nation’s overzealous diagnosis and treatment of the disease.

Dr. Peter Albertsen, a prostate cancer specialist at the University of Connecticut, explains: While 10 percent of men 55 and older find out they have prostate cancer, the cancer is lethal in no more than 25 percent of them. So if finasteride reduced the prostate cancer’s incidence by 30 percent, about 7 percent of men would get a cancer diagnosis and approximately 1.8 percent instead of 2.5 percent would have a lethal cancer.

“Finasteride might make a difference but only in a very small subset of men,” Dr. Albertsen said.

And, he adds, the study did not look for a decline in death rates, and it is unlikely that any study ever will — it would take too long and be too expensive. Yet the ultimate goal of prevention is to save lives. It remains an assumption that finasteride would have much impact on the minority of prostate cancers that, despite early detection and treatment, still kill.

Finasteride blocks the conversion of testosterone to dihydrotestosterone, a hormone active mostly in the prostate and the scalp, and that all prostate cancers need to grow.

The drug is available from Merck & Company, as Proscar, and from six companies as a generic to shrink the prostate in older men whose prostates can enlarge, making urination difficult.

Researchers say it turns out that shrinking the prostate also may be good for cancer detection by making it easier to find all tumors, including the most aggressive.

“The data are compelling,” said Dr. Peter Scardino, chairman of the department of surgery at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, a convert who originally thought the drug was dangerous. “Finasteride has to be recognized as the first clearly demonstrated way to prevent prostate cancer with any medication or any oral agent at all.”

Finasteride has had its ups and downs. Its chronicle began in 1993, with the start of a study sponsored by the National Cancer Institute and involving 19,000 men. Half took finasteride pills; the rest a placebo. In March 2003, 15 months before the study’s scheduled end, its directors halted it abruptly. The reason was that the results were overwhelmingly compelling — men taking the drug were not getting prostate cancer.

Yet despite that note of triumph, a troubling finding emerged. The study was designed to look for a reduction in the overall prostate cancer rate. And that is what it found. But, as Dr. Scardino pointed out in an editorial five years ago in The New England Journal of Medicine that accompanied the study, it appeared that 6.4 percent of the men who took the drug got fast growing, ominous-looking tumors. In contrast, such tumors were found in 5.1 percent, of men who took the placebo.

The concern was that the drug might be preventing cancers that never spread. At the same time, finasteride might actually be causing aggressive cancers that can kill.

It would, of course, be the worse possible outcome. Dr. Scardino’s editorial warned healthy men not to take finasteride.

That seemed to leave the drug dead. The study researchers, though, wondered if that conclusion was correct. Maybe, they thought, by shrinking the prostate, the drug was just making it easier to find aggressive tumors.

When doctors do a biopsy for prostate cancer, they probe the gland with a needle, hoping to find cancer cells. But prostate cancer grows as little nests and an aggressive cancer will appear as dangerous-looking cells in some clusters and less dangerous in others. A smaller prostate means a doctor is more likely to hit upon cancer nests and more likely to find aggressive-looking cells.

The researchers had a way to learn if they were correct. Most of the men in the study who had cancer — aggressive or not — chose to be treated and many had their prostates removed. A pathologist could carefully examine every one of those 500 prostates and compare the kinds of cancers found at surgery to those initially diagnosed at biopsy.

It took years, but the analysis showed the hypothesis was right. Now, two groups of independent researchers conclude, in papers in the current issue of Cancer Prevention Research, that finasteride decreases the risk of having any tumor at all — large or small, fast growing or slow growing, by the same amount — nearly 30 percent.

With this new analysis, many prostate cancer specialists, including Dr. Scardino, say their view of the drug has completely changed. The study actually found that finasteride protects against both lethal and less dangerous tumors and could cut prostate cancer risk by nearly a third.

Even the effect on smaller tumors has important implications, said Dr. Ian M. Thompson, Jr., the study’s principal researcher and a urologist at the University of Texas Health Science Center in San Antonio.

“The cancers that were prevented were the ones men are having surgery and radiation for today,” Dr. Thompson said.

Now, though, prostate cancer specialists have a new problem: How can they change the drug’s image?

Drug companies are unlikely to be instrumental, Dr. Thompson and others say, because finasteride’s patent has expired, giving companies little incentive to apply to the Food and Drug Administration to market it as a cancer preventative. Without F.D.A. approval, finasteride cannot be advertised as preventing cancer and insurers may not pay for it.

But doctors can prescribe drugs for other purposes at their discretion and Dr. Parnes said that men and their doctors may be persuaded to try it.

In the meantime, GlaxoSmithKline, which has a patented drug, Avodart, to reduce the size of men’s prostates, has a study asking whether its drug can prevent prostate cancer. If it can, and the drug agency approves Avodart for cancer prevention, doctors and patients may have to decide between a generic drug used off-label or a more expensive brand-name drug that does much the same thing.

Some leading prostate specialists, like Dr. Scardino, say they are recommending that men who worry about prostate cancer take finasteride.

He also ponders taking it himself. “I regularly think, Why don’t I take it? Why wouldn’t every man take it?” Dr. Scardino said. He hasn’t done so yet, partly because those years of concern about the drug took a toll.

“I think it’s the difficulty of adjusting to something that originally had a bad reputation,” Dr. Scardino explained.

Dr. Thompson has no such fears.

He is at no particular risk for prostate cancer, but, he reasons, taking finasteride is not that different than taking a statin for a slightly elevated cholesterol level.

“Imagine the marathoner with no family history of heart disease, who’s skinny, doesn’t smoke and has normal blood pressure,” Dr. Thompson says. “Should he take a statin? The amount of benefit he’ll get is not much, but his risk reduction still is 25 or 30 percent.”

Dr. Thompson knows what he will do about finasteride.

“I’m 54,” he said. “The men in the study were 55 and older. So I’ll start taking it next year.”

Men who are more interested in preventing prostate cancer than treating it, should make sure that their diet is low in animal fat and includes plenty of lycopenes. These are consumed in the form of cooked tomatoes, as well as garlic, scallions, chives and other vegetables in the alium family.

Vitamin D (in a supplement and from sunlight), Vitamin E (in salad oils, legumes and nuts), pomegranate juice, Selenium and Saw Palmetto are also useful dietary supplements.

Now here is the "bad" news: A new study suggests that eating lycopene-rich tomatoes offers no protection against prostate cancer, contrary to the findings of some past studies. In fact, the researchers found an association between beta carotene, an antioxidant related to lycopene, and an increased risk of aggressive prostate cancer!

Benign Prostatic Hypertrophy

5 Things to Know: B.P.H.

By Gerald Secor Couzen : NY Times Article : April 11, 2008

Once a man passes the half-century mark, it’s not uncommon to experience such bothersome lower-urinary-tract symptoms as frequent urination throughout the day, getting up at night multiple times to urinate or a weak urinary stream. These symptoms are often caused by an enlarged prostate, a condition known as B.P.H., for benign prostatic hyperplasia. As the prostate grows in size, pressure is placed on the urethra, the tube transporting urine from the bladder through the prostate, and this can lead to a host of urinary complaints. Here are five things Dr. Franklin C. Lowe, a professor of urology at Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, believes that every man with B.P.H. should know.

1. B.P.H. is not prostate cancer.

Don’t be afraid if your doctor has told you that your prostate is enlarged and that you have benign prostatic hyperplasia. “Benign” means your prostate is not cancerous. “Prostatic” refers to your prostate, the walnut-size gland below your bladder. “Hyperplasia” means an excessive formation of cells. B.P.H., the noncancerous enlargement of your prostate, is the most common tumor found in men.

2. Symptoms.

Before deciding on a course of treatment, ask yourself how bothered you are by symptoms. Are you losing sleep because of multiple nocturnal awakenings to go to the bathroom? If not, and if symptoms are not worsening, you may not have to do anything. Remember, however, symptoms often worsen over time. The International Prostate Symptoms Score, a seven-question guide for determining the severity of symptoms, is an excellent self-assessment. Scores of 0 to 7 are considered mild, 8 to 19 indicate moderate problems and 20 to 35 mean symptoms are severe.

3. Medications.

Some men find temporary relief with saw palmetto capsules or by reducing their daily fluid intake and avoiding alcohol and caffeinated beverages. A variety of prescription B.P.H. medications are available. While no prescription drug offers a cure, they ease symptoms in more than 60 percent of men.

4. Outpatient heat therapies.

Within a year of starting prescription drug therapy for B.P.H., one-third of men discontinue medications due to lack of efficacy, bothersome side effects or cost. Minimally invasive heat treatments, in which extreme heat is applied to destroy excess prostate tissue, include transurethral needle ablation of the prostate (TUNA), transurethral electrovaporization of the prostate (TUVP), transurethral microwave therapy (TUMT) and water-induced thermotherapy (WIT). These treatments are generally safe and effective but may need to be repeated every five years or so.

5. TURP, the “gold standard.”

If B.P.H. symptoms have not improved with other therapies, laser therapy can be used during an outpatient procedure to vaporize prostate tissue. If your problems are severe, your doctor may recommend a transurethral resection of the prostate, or TURP, a surgical procedure that effectively relieves symptoms and rarely requires a second treatment.

For Men, Relief in Sight

By Gerald Secor Couzens : NY Times Article : May 13, 2008

MEN, the joke goes, spend the first half of their lives making money and the second making water. That is because after age 50 many men face an embarrassing problem called B.P.H., for benign prostatic hyperplasia. This slowly progressive enlargement of the prostate can make urination difficult or painful and send men trudging to the bathroom many times during the day and night.

Though bothersome, B.P.H. is not life threatening. Nor does it lead to cancer. When left untreated, however, B.P.H. can lead to serious health problems for some.

“My father used to be up 10 times a night and said it wasn’t a problem for him,” said Dr. Franklin C. Lowe, professor of urology at Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons. “However, he developed urinary tract infections annually because of his B.P.H. and almost died from sepsis one year. Surprisingly, his case is not unique.”

Many doctors are now urging men to become proactive earlier to prevent chronic problems in the future. Bladder stones, infections and bladder or kidney damage can arise and sometimes require surgery. Urological experts are beginning to rethink treatments, too, based on symptoms and how much a man is bothered by them.

“There is a big difference between having the symptoms and being bothered by the symptoms,” said Dr. Kevin T. McVary, professor of urology at the Feinberg School of Medicine at Northwestern University. “Some men go to the bathroom several times a night, get right back to sleep and are not bothered,” he said. Watchful waiting, or monitoring symptoms while holding off on medical or surgical treatments, is a reasonable plan for these men, he added. But for patients who have trouble getting back to sleep, “there are many effective options, and patients almost always end up with less bothersome symptoms once they choose to do something,” he said.

Although no drug offers a cure, “many men can be managed nicely with medical therapy,” Dr. Lowe said. The latest thinking is that combination therapy — taking both of the two main types of B.P.H. drugs — achieves maximum benefit. Alpha blockers like Flomax, Uroxatral, Hytrin and Cardura relax muscle fibers in the bladder and prostate. Other drugs like Proscar and Avodart, called 5-alpha-reductase inhibitors, shrink the prostate over 9 to 18 months. Once the drugs are stopped, however, symptoms typically recur. Researchers are also exploring the use of erectile dysfunction drugs for men with erection problems and B.P.H. as well as the antiwrinkle drug Botox.

There are also minimally invasive B.P.H. therapies that use heat, ultrasound, microwaves, low-frequency radio waves or lasers to hollow out the prostate’s core and relieve the pressure on the urethra that is reducing urine flow. These outpatient procedures have a long-lasting effect, although many men need an additional procedure within five years, and some even sooner.

“I tell patients, If you have to go through one procedure for your prostate, make sure it is one that will give long-lasting results,” Dr. Lowe said. He recommends the transurethral resection of the prostate. This “gold standard” surgery, performed under anesthesia, involves removing excess prostate tissue with an instrument inserted through the penis. It can offer relief for 10 years or more.

Robert H. Getzenberg, professor of urology at the Johns Hopkins Brady Urological Institute in Baltimore, notes that many men with B.P.H. are surprised to find that their urinary symptoms persist even after cancer surgery to remove the prostate. “People used to think that B.P.H. was just a disease of the prostate, and that’s not entirely true,” he said. “That’s because the prostate is only one component of B.P.H. The bladder, as we have found out, is another.”

Over time, he adds, the bladder may respond to changes in urinary patterns and pressure by becoming thicker and less resilient. When that occurs, a man feels as if he has to urinate more often, and the prostate problem has become a bladder issue.

Dr. Getzenberg believes there is more than one type of B.P.H., and that each requires different treatment. “There is the common B.P.H. found in most men as they age,” he said. “Urinary symptoms are mild and less likely to lead to bladder and other urinary tract damage.” A more severe form of B.P.H. is not always benign. “It’s highly symptomatic and has increased risk of damage to the bladder,” he added.

Genetic tests may eventually give men answers that will lead to better treatment of their condition. “If we can differentiate men into different groups, we can treat this disease more efficiently and effectively,” Dr. Getzenberg said. “This will allow us to intervene much earlier in the disease process.”

Rethinking an Old Ailment: Enlarged Prostate

By Gerald Secor Couzens : NY Times Article : April 11, 2008

Prostate cells in benign prostatic hyperplasia show excessive growth but are not cancerous; they have characteristics of healthy prostate cells, like the uptake of the mineral zinc (arrows).

IN BRIEF

- There is no link between BPH, the common benign form of enlarged prostate, and prostate cancer

- Doctors are urging men with BPH to be proactive, to prevent more serious problems later

- Urinary symptoms help to determine treatment for BPH

Although no drug offers a cure, “many men can be managed nicely with medical therapy,” Dr. Lowe said. The latest thinking is that combination therapy — in which men take both of the two main types of B.P.H. drugs — achieves maximum benefit. Alpha-blockers like Flomax, Uroxatral, Hytrin and Cardura relax muscle fibers in the bladder and prostate. Other drugs like Proscar and Avodart, called 5-alpha-reductase inhibitors, shrink the prostate over 9 to 18 months. Once the drugs are stopped, however, symptoms typically recur. Researchers are also exploring the use of erectile dysfunction drugs for men with erection problems and B.P.H. as well as the antiwrinkle drug Botox.

There are also minimally invasive, nonsurgical B.P.H. therapies that use heat, ultrasound, microwaves, radiofrequency or lasers to hollow out the prostate’s core and relieve the pressure on the urethra that is reducing urine flow. These 30-to-60-minute outpatient procedures are long lasting, although many men need an additional procedure within five years, some even earlier.

“I tell patients, ‘If you have to go through one procedure for your prostate, make sure it is one that will give long-lasting results,’ ” Dr. Lowe said. He recommends the TURP, for transurethral resection of the prostate. This “gold standard” surgery, performed under anesthesia, involves removing excess prostate tissue via an instrument inserted through the penis. It requires an overnight hospital stay but can offer relief for 10 years or more.

Robert H. Getzenberg, professor of urology at the Johns Hopkins Brady Urological Institute in Baltimore, notes that many men with B.P.H. are surprised to find that their urinary symptoms persist even after cancer surgery to remove the prostate. “People used to think that B.P.H. was just a disease of the prostate, and that’s not entirely true,” he said. “That’s because the prostate is only one component of B.P.H. The bladder, as we have found out, is another.”

Over time, he notes, the bladder may respond to changes in urinary patterns and pressure by becoming thicker and less resilient. When that occurs, a man feels as if he has to urinate more frequently. What started as a prostate problem has become a bladder issue.

Dr. Getzenberg believes there is more than one type of B.P.H. and that each requires a different treatment approach. “There is the common B.P.H. found in most men as they age,” he said. “Urinary symptoms are mild and less likely to lead to bladder and other urinary tract damage.” A second, more severe form of B.P.H. isn’t always benign. “It’s highly symptomatic and has increased risk of damage to the bladder,” he added.

He has developed a genetic blood test called JM-27 that detects about 90 percent of men with the severe form of B.P.H. “It has nothing to do with the size of a man’s prostate or the presence or risk of prostate cancer,” Dr. Getzenberg said. “If we can differentiate men into different groups, we can treat this disease more efficiently and effectively. This will allow us to intervene much earlier in the disease process instead of trying to treat B.P.H. in its severe form.”

Veteran urologists who have seen dozens of promising tests and procedures ultimately fail when put through rigorous testing are naturally skeptical. “JM-27 is a great concept, but it’s too early to draw conclusions,” Dr. Lowe said.

Questions and answers from Dr. Kevin T. McVary

Q. Are you happy with the current drugs for B.P.H.?

A. Yes and no. I am very happy that we have medical therapies for B.P.H. Many patients get relief of their symptoms from the various drugs. However, if you look at the drugs objectively, the response is relatively modest. Medications, which have to be taken daily and indefinitely, just don’t work as well as minimally invasive heat therapies, laser therapy or TURP.

Q. Does B.P.H. improve without any therapy?

A. If you look at some of the observation studies, enlarged prostate symptoms will fluctuate. About half of the men will note improvement in their symptoms to an appreciable degree over the course of a year, so watchful waiting in the early stages is certainly a reasonable choice. Steady improvement is not inevitable, however.

Q. What do you think of the herb saw palmetto as a B.P.H. therapy?

A. For the past 100 years, saw palmetto has been a favorite treatment for B.P.H. While many of my patients swear on a stack of bibles that it helps them, I’d be a rich man if I got a nickel for every one that had no luck with this over-the-counter therapy. A 2006 study of 225 men with moderate to severe B.P.H. was published in The New England Journal of Medicine. The men were randomly assigned to take either a saw palmetto extract or a placebo daily for a year. At the end of the study, the researchers found no differences between the groups in their prostate symptom scores or quality of life.

Q. What novel therapies for B.P.H. are now being tested?

A. Treatment of B.P.H. has relied on alpha-blocker medication (similar to what is prescribed for hypertension) and 5-alpha reductase inhibitors, oral medications that cause the prostate gland to shrink over time, improving urinary symptoms in the process. When these drugs are taken in combination, two-thirds of the men who take them get relief of symptoms.

However, as our understanding of the prostate and the entire lower urinary tract system increases, several novel B.P.H. approaches are being explored. In the future, the B.P.H. armamentarium may include drugs similar to that we now use for erectile dysfunction. In addition, Botox, originally developed from a deadly toxin to cure a rare eye condition and now used as a wrinkle remover, may also be used if clinical studies prove its worth as an effective B.P.H. therapy.

Q. Can Viagra and other erectile dysfunction medications help men with B.P.H.?

A. In the last few years, it has become obvious that men suffering from lower urinary tract symptoms and E.D. seemed to be the same men. We used to look at these ailments in aging men as separate diseases occurring in the same people by coincidence. We are now realizing that B.P.H. and E.D are linked somehow. One disease process may be causing both E.D. and B.P.H. symptoms.

In my erection drug study that I reported at the annual meeting of the American Urological Association in 2007, I described how 369 men with erectile dysfunction and B.P.H. were randomized to receive either placebo or 50 milligrams of Viagra a day for 12 weeks. The medication was taken before bedtime and an hour before sexual activity. Over all, after Viagra treatment, patients with severe B.P.H. at the start of the study experienced a greater improvement (73 percent) in urinary symptoms. More than 55 percent of the men improved to moderate B.P.H. levels, and 16 percent improved to mild levels.

The magnitude of improvement in International Prostate Symptom Scores for men with moderate to severe complaints appeared to be comparable to that achieved with alpha-blockers and 5-alpha reductase inhibitors.

We know that 30 percent of patients discontinue alpha-blocker medication for their B.P.H. within the first 12 months due to adverse side effects or nonresponse. I see the E.D. medications as potentially new agents for treating lower urinary tract symptoms. The erection drugs not only work as an effective form of therapy for lower urinary complaints, but they offer a nice side effect: improved erections. In the future, we may not use Viagra, Cialis and Levitra for urinary complaints, but rather new formulations of these drugs that are geared to specifically influence the bladder and prostate.

Right now, these drugs are used off label by early adopters, urological researchers and physicians frustrated by nonresponse to other medical therapy from their patients.

Q. Why do erectile dysfunction drugs seem to help men with B.P.H.?

A. No one knows for sure, but there are several plausible explanations. One is the influence of the drugs at the bladder level. In addition to the penis, the bladder muscles also have very high activity levels of phosphodiesterase 5 (P.D.E.-5), and so does the prostate. What the erection drugs Viagra, Levitra and Cialis do is block the P.D.E.-5, preventing the enzyme from breaking down nitric oxide, which is needed to dilate blood vessels. Not only are the penile arteries relaxed by the medication, which allows blood to flow into the penis, but these drugs might also cause small blood vessels in the prostate and bladder to dilate, improving urinary symptoms in the process.

Another plausible idea is that these medications may affect neurotransmission in the spinal cord. Even though urination flow rates may not change, the men’s perception of urgency and bother may be altered by the impact of the drug on the central nervous system.

A final cause for improvement in B.P.H. from the E.D. drugs could be that older men with lower urinary complaints have nerve signals to the brain, bladder and prostate that are acting inappropriately. The erection drugs might help mute the erratic signals and therefore improve B.P.H. symptoms.

Q. Can Botox be used to help men with B.P.H.?

A. Although most people think of Botox (botulinum toxin type A) as a wrinkle remedy, it may also play a significant role in the near future as an effective B.P.H. remedy. I have done several studies with the medication, and many of the patients I have treated have had a quick and significant response to the drug.

The Botox injection is performed under ultrasound guidance to help guide the needle to the prostate. Within eight days, many of my study subjects were able to stop all B.P.H. medications. In addition, they saw a drop in their International Prostate Symptom Scores by as much as 50 percent. There don’t appear to be any side effects when the drug is used for B.P.H. therapy.

Q. How does Botox improve B.P.H. symptoms?

A. Botox injections work by weakening or paralyzing certain muscles or by blocking certain nerves. It’s not clear how Botox actually works in the prostate, but it appears that after the injection, the prostate gland undergoes an almost immediate involution; it shrinks down. This reduction in size can improve urine flow and decrease residual urine left in the bladder.

This is a fascinating product for B.P.H., and Botox injected into the prostate seems to be a promising approach that could represent a simple, safe and effective treatment for an enlarged prostate. Currently, however, Botox is not approved by the Food and Drug Administration for this use.

Questions you can ask your doctor:

- Does B.P.H. get better without any therapy?

- Can B.P.H. symptoms be treated effectively with herbal products?

- How can I select a B.P.H. treatment that will work best for me?

- What are the advantages and disadvantages of “watchful waiting” for B.P.H.?

- What are the advantages of alpha-blockers for easing B.P.H. symptoms?

- What are the side effects of alpha-blockers?

- What are the advantages of the 5-alpha-reductase inhibiting medications for treating B.P.H.?

- What are the drawbacks of using 5-alpha-reductase inhibitors for treating B.P.H.?

- How do you decide whether to use an alpha-blocker or a 5-alpha-reductase inhibitor for treating bothersome B.P.H. symptoms?

- If medical therapy has not been effective in relieving B.P.H. symptoms, what is the next step?

- What are the advantages of minimally invasive heat therapies?

- What are the disadvantages of minimally invasive therapies?

- What are the advantages of a laser-resection therapy for B.P.H.?

PSA : Prostate Specific Antigen Testing

Deciphering the Results of a Prostate Test

By Jane E Brody : NY Times Article : May 8, 2007

After his annual physical, a middle-age man is told that his PSA level has jumped to 2.3 after having been stable for years at 1.5. Should he be alarmed?

Maybe and maybe not. The PSA test, as few men older than 40 need to be told, is widely used as a screening tool for prostate cancer. But the test is controversial, and for good reason.

For one thing, the cancer itself is highly variable. As many as 15 percent of 50-year-old men will be given diagnoses of prostate cancer over the next 30 years. But 1.4 percent will die of the disease in that time, a 10-fold difference that shows that the cancer is usually not fatal. By age 85, more than three-fourths of men have evidence of prostate cancer; many have lived with the disease for more than 10 years.

In addition, PSA levels often fluctuate as much as 30 percent for unknown reasons and can increase for reasons other than cancer, challenging physicians who have to determine how to proceed when a man’s PSA level goes up.

“There’s a lot of background noise” associated with PSA testing, said Dr. Peter T. Scardino, chief of urology at the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York and author of “Dr. Peter Scardino’s Prostate Book” (Penguin, 2005). Still, as evidence of the value of the test, he noted that the United States has since 1992 recorded a 30 percent decline in age-specific mortality from prostate cancer, “despite no dramatic new therapy for advanced disease.”

Factors Behind the Measurement

PSA stands for prostate-specific antigen, a substance produced only by the prostate gland and found in the ejaculate. Its purpose is to liquefy the semen to release sperm, freeing them to fertilize an egg. The PSA level, measured in nanograms per milliliter of blood, reflects how much of this antigen is being produced and released into the bloodstream. The larger a man’s prostate, the more PSA is produced, which makes the test very confusing in older men with benign enlargement of this gland.

Aside from cancer and prostatic growth with age, factors that can change PSA measurements include inflammation or infection of the prostate; a decline in testosterone levels or the drug finasteride, taken for hair loss, both of which lower the PSA; and variations in laboratory assays and in the inherent biology of a person. Biological variability can result in as much as a 15 percent difference between readings, and in nearly half of men with an abnormal PSA, the test will normalize in one to four years without any treatment.

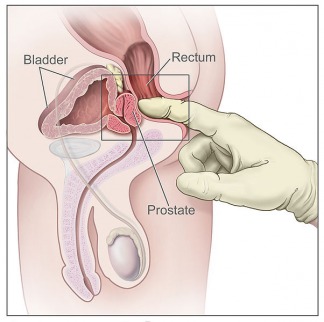

But Dr. H. Ballentine Carter, a urologist at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, notes that no significant changes in PSA result from recent sexual intercourse or ejaculation, a digital rectal examination or riding a bicycle. “Even long-distance bikers do not have prostate trauma” that causes their PSA to increase, Dr. Carter said.

Current guidelines recommend that all men have an annual PSA test starting at age 50 and that biopsies be conducted if the level exceeds 4 or if a “significant rise” occurs between two tests. The guidelines also suggest limiting screening to men with more than a 10-year life expectancy.

This approach has resulted in many biopsies in men who did not have cancer — about 70 percent of those with elevated PSAs are cancer free — and debilitating prostate surgery in men with cancers that would never have become a threat in their remaining years of life.

On the Way: New Guidelines

Based on recent studies, the American Urological Association will soon release revised guidelines that, experts hope, will reduce unnecessary biopsies and prostate surgeries, which even in the best hands can leave a man impotent and incontinent. The revised guidelines are expected to reduce the cost of screening, the cost per life saved and overall deaths from prostate cancer.

The new guidelines will no longer rely on a single reading. Rather, they will suggest that doctors focus on changes in levels over time. They will also suggest that testing start at 40 to obtain a baseline measurement, with the test repeated at 45 and 50, after which it should be given annually until 70.

“If a 70-year-old man has a PSA history that hasn’t changed over the years, maybe he doesn’t need further testing,” Dr. Carter suggested. “PSA testing of men over 70 is not rational.”

He pointed to a Scandinavian study showing that among men older than 65, to prevent one death from prostate cancer over 10 years, 330 men would have to have prostate surgery.

“This has created a huge dilemma in urology,” Dr. Carter said. “We don’t want to miss the possibility of a life-threatening disease, but we end up diagnosing and treating disease that would never have caused harm.”

The new guidelines will lower the PSA level at which a biopsy should be considered, because, as Dr. Carter put it, “there’s no level below which we can tell a man he doesn’t have prostate cancer or life-threatening prostate cancer.”

As one important trial showed, among men with a very low PSA — that is, a reading below the current cutoff of 4 — biopsies found that 15 percent had prostate cancer. Among that 15 percent, Dr. Carter said, 15 percent had high-grade, potentially life-threatening cancers. That means that 2.25 percent of the total number of men with a PSA less than 4 had life-threatening cancers.

But, he added, “If we biopsied every man with a PSA below 4, we’d be looking at a sea of cancers that would never grow to be life threatening.”

Getting Enough Data

These facts and the results of a recent study by Dr. Carter, among others, indicated that rather than acting on the basis of a single PSA test, the rate of change in levels over time is a better indicator of who might have a serious cancer. This rate, known as PSA velocity, will be part of the new guidelines, which will suggest that in men with low readings, doctors consider the changes in levels over the course of three measurements.

“We need at least 1 ½ to 2 years’ worth of data” to make a meaningful judgment about how to proceed, Dr. Carter said.