- RETIREMENT ANNOUNCEMENT

- HOME PAGE

- "MYCHART" the new patient portal

- BELMONT MEDICAL ASSOCIATES

- MOUNT AUBURN HOSPITAL

- EMERGENCIES

- PRACTICE PHILOSOPHY

- MY RESUME

- TELEMEDICINE CONSULTATION

- CONTACT ME

- LAB RESULTS

- ePRESCRIPTIONS

- eREFERRALS

- RECORD RELEASE

- MEDICAL SCRIBE

- PHYSICIAN ASSISTANT (PA)

- Medicare Annual Wellness Visit

- Case management/Social work

- Quality Care Measures

- Emergency closing notice

- FEEDBACK

- Talking to your doctor

- Choosing..... and losing a doctor

- INDEX A - Z

- ALLERGIC REACTIONS

- Alternative Medicine

- Alzheimer's Disease

- Bladder Problems

- Blood disorders

- Cancer Concerns

- GENETIC TESTING FOR HEREDITARY CANCER

- Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

- Controversial Concerns

- CPR : Learn and save a life

- CRP : Inflammatory marker

- Diabetes Management

- Dizziness, Vertigo,Tinnitus and Hearing Loss

- EXERCISE

- FEMALE HEALTH

-

GASTROINTESTINAL topics

- Appendicitis

- BRAT diet

- Celiac Disease or Sprue

- Crohn's Disease

- Gastroenterologists for Colon Cancer Screening

- Colonoscopy PREP

- Constipation

- Gluten sensitivity, but not celiac disease

- Heartburn and GERD

- Hemorrhoids and Anal fissure

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- NASH : Non Alcoholic Steato Hepatitis

- FEET PROBLEMS

- HEART RELATED topics

-

INFECTIOUS DISEASES

- Antibiotic Resistance

- Cat bites >

- Clostridia difficile infection - the "antibiotic associated germ"

- CORONA VIRUS

- Dengue Fever and Chikungunya Fever

- Food borne illnesses

- Shingles Vaccine

- Hepatitis B

- Hepatitis C

- Herpes

- Influenza

- Helicobacter pylori - the "ulcer germ"

- HIV Screening

- Lyme and other tick borne diseases

- Measles

- Meningitis

- MRSA (Staph infection)

- Norovirus

- Sexually Transmitted Diseases

- Shingles (Herpes Zoster)

- Sinusitis

- West Nile Virus

- Whooping Cough (Pertussis)

- Zika virus and pregnancy

- INSURANCE related topics

- KIDNEY STONES

- LEG CRAMPS

- LIBRARY for patients

- LIFE DECISIONS

- MALE HEALTH

- Medication/Drug side effects

- MEDICAL MARIJUANA

- MENTAL HEALTH

- Miscellaneous Articles

-

NUTRITION - EXERCISE - WEIGHT

- Cholesterol : New guidelines for treatment

- Advice to lower your cholesterol

- Cholesterol : Control

- Cholesterol : Raising your HDL Level

- Exercise

- Food : Making Smart Choices

- Food : Making Poor Choices

- Food : Grape Fruit and Drug Interaction

- Food : Vitamins, Minerals and Supplements

- Omega 3 fatty acids

- Vitamin B12 deficiency

- Vitamin D

- Weight Loss

- ORTHOPEDICS

- PAIN

- PATIENTS' RIGHTS

- SKIN

- SLEEP

- SMOKING

- STROKE

- THYROID

- SUBSTANCE ABUSE

- Travel and Vaccination

- TREMOR

- Warfarin Anticoagulation

- OTHER STUFF FOLLOWS

- Fact or Opinion?

- Hippocratic Oath

- FREE ADVICE.......for what its worth!

- LAUGHTER.....is the best medicine

- Physicians Pet Peeves

- PHOTO ALBUM - its not all work!

- Cape Town, South Africa

- Tribute page

- The 100 Club

- Free Wi-Fi

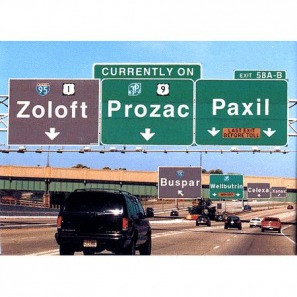

Depression : Therapy

In Defense of Antidepressants

By Peter D. Kramer : NY Times : July 09, 2011

In terms of perception, these are hard times for antidepressants. A number of articles have suggested that the drugs are no more effective than placebos.

Last month brought an especially high-profile debunking. In an essay in The New York Review of Books, Marcia Angell, former editor in chief of The New England Journal of Medicine, favorably entertained the premise that “psychoactive drugs are useless.” Earlier, a USA Today piece about a study done by the psychologist Robert DeRubeis had the headline, “Antidepressant lift may be all in your head,” and shortly after, a Newsweek cover piece discussed research by the psychologist Irving Kirsch arguing that the drugs were no more effective than a placebo.

Could this be true? Could drugs that are ingested by one in 10 Americans each year, drugs that have changed the way that mental illness is treated, really be a hoax, a mistake or a concept gone wrong?

This supposition is worrisome. Antidepressants work — ordinarily well, on a par with other medications doctors prescribe. Yes, certain researchers have questioned their efficacy in particular areas — sometimes, I believe, on the basis of shaky data. And yet, the notion that they aren’t effective in general is influencing treatment.

For instance, not long ago, I received disturbing news: a friend had had a stroke that paralyzed the right side of his body. Hoping to be of use, I searched the Web for a study I vaguely remembered. There it was: a group in France had worked with more than 100 people with the kind of stroke that affected my friend. Along with physiotherapy, half received Prozac, and half a placebo. Members of the Prozac group recovered more of their mobility. Antidepressants are good at treating post-stroke depression and good at preventing it. They also help protect memory. In stroke patients, antidepressants look like a tonic for brain health.

When I learned that my friend was not on antidepressants, I suggested he raise the issue with his neurologists. I e-mailed them the relevant articles. After further consideration, the doctors added the medicines to his regimen of physical therapy.

Surprised that my friend had not been offered a highly effective treatment, I phoned Robert G. Robinson at the University of Iowa’s department of psychiatry, a leading researcher in this field. He said, “Neurologists tell me they don’t use an antidepressant unless a patient is suffering very serious depression. They’re influenced by reports that say that’s all antidepressants are good for.”

Critics raise various concerns, but in my view the serious dispute about antidepressant efficacy has a limited focus. Do they work for the core symptoms (such as despair, low energy and feelings of worthlessness) of isolated episodes of mild or moderate depression? The claim that antidepressants do nothing for this common condition — that they are merely placebos with side effects — is based on studies that have probably received more ink than they deserve.

The most widely publicized debunking research — the basis for the Newsweek and New York Review pieces — is drawn from data submitted to the Food and Drug Administration in the late 1980s and the 1990s by companies seeking approval for new drugs. This research led to its share of scandal when a study in The New England Journal of Medicine found that the trials had been published selectively. Papers showing that antidepressants work had found their way into print; unfavorable findings had not.

In his book “The Emperor’s New Drugs: Exploding the Antidepressant Myth,” Dr. Kirsch, a psychologist at the University of Hull in England, analyzed all the data. He found that while the drugs outperformed the placebos for mild and moderate depression, the benefits were small. The problem with the Kirsch analysis — and none of the major press reports considered this shortcoming — is that the F.D.A. material is ill suited to answer questions about mild depression.

As a condition for drug approval, the F.D.A. requires drug companies to demonstrate a medicine’s efficacy in at least two trials. Trials in which neither the new drug nor an older, established drug is distinguishable from a placebo are deemed “failed” and are disregarded or weighed lightly in the evaluation. Consequently, companies rushing to get medications to market have had an incentive to run quick, sloppy trials.

Often subjects who don’t really have depression are included — and (no surprise) weeks down the road they are not depressed. People may exaggerate their symptoms to get free care or incentive payments offered in trials. Other, perfectly honest subjects participate when they are at their worst and then spontaneously return to their usual, lower, level of depression.

THIS improvement may have nothing to do with faith in dummy pills; it is an artifact of the recruitment process. Still, the recoveries are called “placebo responses,” and in the F.D.A. data they have been steadily on the rise. In some studies, 40 percent of subjects not receiving medication get better.

The problem is so big that entrepreneurs have founded businesses promising to identify genuinely ill research subjects. The companies use video links to screen patients at central locations where (contrary to the practice at centers where trials are run) reviewers have no incentives for enrolling subjects. In early comparisons, off-site raters rejected about 40 percent of subjects who had been accepted locally — on the ground that those subjects did not have severe enough symptoms to qualify for treatment. If this result is typical, many subjects labeled mildly depressed in the F.D.A. data don’t have depression and might well respond to placebos as readily as to antidepressants.

Nonetheless, the F.D.A. mostly gets it right. To simplify a complex matter: there are two sorts of studies that are done on drugs: broad trials and narrow trials. Broad trials, like those done to evaluate new drugs, can be difficult these days, because many antidepressants are available as generics. Who volunteers to take an untested remedy? Research subjects are likely to be an odd bunch.

Narrow studies, done on those with specific disorders, tend to be more reliable. Recruitment of subjects is straightforward; no one’s walking off the street to enter a trial for stroke patients. Narrow studies have identified many specific indications for antidepressants, such as depression in neurological disorders, including multiple sclerosis and epilepsy; depression caused by interferon, a medication used to treat hepatitis and melanoma; and anxiety disorders in children.

New ones regularly emerge. The June issue of Surgery Today features a study in which elderly female cardiac patients who had had emergency operations and were given antidepressants experienced less depression, shorter hospital stays and fewer deaths in the hospital.

Broad studies tend to be most trustworthy when they look at patients with sustained illness. A reliable finding is that antidepressants work for chronic and recurrent mild depression, the condition called dysthymia. More than half of patients on medicine get better, compared to less than a third taking a placebo. (This level of efficacy — far from ideal — is typical across a range of conditions in which antidepressants outperform placebos.) Similarly, even the analyses that doubt the usefulness of antidepressants find that they help with severe depression.

In fact, antidepressants appear to have effects across the depressive spectrum. Scattered studies suggest that antidepressants bolster confidence or diminish emotional vulnerability — for people with depression but also for healthy people. In the depressed, the decrease in what is called neuroticism seems to protect against further episodes. Because neuroticism is not a core symptom of depression, most outcome trials don’t measure this change, but we can see why patients and doctors might consider it beneficial.

Similarly, in rodent and primate trials, antidepressants have broad effects on both healthy animals and animals with conditions that resemble mood disruptions in humans.

One reason the F.D.A. manages to identify useful medicines is that it looks at a range of evidence. It encourages companies to submit “maintenance studies.” In these trials, researchers take patients who are doing well on medication and switch some to dummy pills. If the drugs are acting as placebos, switching should do nothing. In an analysis that looked at maintenance studies for 4,410 patients with a range of severity levels, antidepressants cut the odds of relapse by 70 percent. These results, rarely referenced in the antidepressant-as-placebo literature, hardly suggest that the usefulness of the drugs is all in patients’ heads.

The other round of media articles questioning antidepressants came in response to a seemingly minor study engineered to highlight placebo responses. One effort to mute the placebo effect in drug trials involves using a “washout period” during which all subjects get a dummy pill for up to two weeks. Those who report prompt relief are dropped; the study proceeds with those who remain symptomatic, with half getting the active medication. In light of subject recruitment problems, this approach has obvious appeal.

Dr. DeRubeis, an authority on cognitive behavioral psychotherapy, has argued that the washout method plays down the placebo effect. Last year, Dr. DeRubeis and his colleagues published a highly specific statistical analysis. From a large body of research, they discarded trials that used washouts, as well as those that focused on dysthymia or subtypes of depression. The team deemed only six studies, from over 2,000, suitable for review. An odd collection they were. Only studies using Paxil and imipramine, a medicine introduced in the 1950s, made the cut — and other research had found Paxil to be among the least effective of the new antidepressants. One of the imipramine studies used a very low dose of the drug. The largest study Dr. DeRubeis identified was his own. In 2005, he conducted a trial in which Paxil did slightly better than psychotherapy and significantly better than a placebo — but apparently much of the drug response occurred in sicker patients.

Building an overview around your own research is problematic. Generally, you use your study to build a hypothesis; you then test the theory on fresh data. Critics questioned other aspects of Dr. DeRubeis’s math. In a re-analysis using fewer assumptions, Dr. DeRubeis found that his core result (less effect for healthier patients) now fell just shy of statistical significance. Overall, the medications looked best for very severe depression and had only slight benefits for mild depression — but this study, looking at weak treatments and intentionally maximized placebo effects, could not quite meet the scientific standard for a firm conclusion. And yet, the publication of the no-washout paper produced a new round of news reports that antidepressants were placebos.

In the end, the much heralded overview analyses look to be editorials with numbers attached. The intent, presumably to right the balance between psychotherapy and medication in the treatment of mild depression, may be admirable, but the data bearing on the question is messy.

As for the news media’s uncritical embrace of debunking studies, my guess, based on regular contact with reporters, is that a number of forces are at work. Misdeeds — from hiding study results to paying off doctors — have made Big Pharma an inviting and, frankly, an appropriate target. (It’s a favorite of Dr. Angell’s.) Antidepressants have something like celebrity status; exposing them makes headlines.

It is hard to locate the judicious stance with regard to antidepressants and moderate mood disorder. In my 1993 book, “Listening to Prozac,” I wrote, “To my mind, psychotherapy remains the single most helpful technology for the treatment of minor depression and anxiety.” In 2003, in “Against Depression,” I highlighted research that suggested antidepressants influence mood only indirectly. It may be that the drugs are “permissive,” removing roadblocks to self-healing.

That model might predict that in truth the drugs would be more effective in severe disorders. If antidepressants act by usefully perturbing a brain that’s “stuck,” then people who retain some natural resilience would see a lesser benefit. That said, the result that the debunking analyses propose remains implausible: antidepressants help in severe depression, depressive subtypes, chronic minor depression, social unease and a range of conditions modeled in mice and monkeys — but uniquely not in isolated episodes of mild depression in humans.

Better designed research may tell us whether there is a point on the continuum of mood disorder where antidepressants cease to work. If I had to put down my marker now — and effectively, as a practitioner, I do — I’d bet that “stuckness” applies all along the line, that when mildly depressed patients respond to medication, more often than not we’re seeing true drug effects. Still, my approach with mild depression is to begin treatments with psychotherapy. I aim to use drugs sparingly. They have side effects, some of them serious. Antidepressants help with strokes, but surveys also show them to predispose to stroke. But if psychotherapy leads to only slow progress, I will recommend adding medicines. With a higher frequency and stronger potency than what we see in the literature, they seem to help.

My own beliefs aside, it is dangerous for the press to hammer away at the theme that antidepressants are placebos. They’re not. To give the impression that they are is to cause needless suffering.

As for my friend, he had made no progress before his neurologists prescribed antidepressants. Since, he has shown a slow return of motor function. As is true with much that we see in clinical medicine, the cause of this change is unknowable. But antidepressants are a reasonable element in the treatment — because they do seem to make the brain more flexible, and they’ve earned their place in the doctor’s satchel.

By Peter D. Kramer : NY Times : July 09, 2011

In terms of perception, these are hard times for antidepressants. A number of articles have suggested that the drugs are no more effective than placebos.

Last month brought an especially high-profile debunking. In an essay in The New York Review of Books, Marcia Angell, former editor in chief of The New England Journal of Medicine, favorably entertained the premise that “psychoactive drugs are useless.” Earlier, a USA Today piece about a study done by the psychologist Robert DeRubeis had the headline, “Antidepressant lift may be all in your head,” and shortly after, a Newsweek cover piece discussed research by the psychologist Irving Kirsch arguing that the drugs were no more effective than a placebo.

Could this be true? Could drugs that are ingested by one in 10 Americans each year, drugs that have changed the way that mental illness is treated, really be a hoax, a mistake or a concept gone wrong?

This supposition is worrisome. Antidepressants work — ordinarily well, on a par with other medications doctors prescribe. Yes, certain researchers have questioned their efficacy in particular areas — sometimes, I believe, on the basis of shaky data. And yet, the notion that they aren’t effective in general is influencing treatment.

For instance, not long ago, I received disturbing news: a friend had had a stroke that paralyzed the right side of his body. Hoping to be of use, I searched the Web for a study I vaguely remembered. There it was: a group in France had worked with more than 100 people with the kind of stroke that affected my friend. Along with physiotherapy, half received Prozac, and half a placebo. Members of the Prozac group recovered more of their mobility. Antidepressants are good at treating post-stroke depression and good at preventing it. They also help protect memory. In stroke patients, antidepressants look like a tonic for brain health.

When I learned that my friend was not on antidepressants, I suggested he raise the issue with his neurologists. I e-mailed them the relevant articles. After further consideration, the doctors added the medicines to his regimen of physical therapy.

Surprised that my friend had not been offered a highly effective treatment, I phoned Robert G. Robinson at the University of Iowa’s department of psychiatry, a leading researcher in this field. He said, “Neurologists tell me they don’t use an antidepressant unless a patient is suffering very serious depression. They’re influenced by reports that say that’s all antidepressants are good for.”

Critics raise various concerns, but in my view the serious dispute about antidepressant efficacy has a limited focus. Do they work for the core symptoms (such as despair, low energy and feelings of worthlessness) of isolated episodes of mild or moderate depression? The claim that antidepressants do nothing for this common condition — that they are merely placebos with side effects — is based on studies that have probably received more ink than they deserve.

The most widely publicized debunking research — the basis for the Newsweek and New York Review pieces — is drawn from data submitted to the Food and Drug Administration in the late 1980s and the 1990s by companies seeking approval for new drugs. This research led to its share of scandal when a study in The New England Journal of Medicine found that the trials had been published selectively. Papers showing that antidepressants work had found their way into print; unfavorable findings had not.

In his book “The Emperor’s New Drugs: Exploding the Antidepressant Myth,” Dr. Kirsch, a psychologist at the University of Hull in England, analyzed all the data. He found that while the drugs outperformed the placebos for mild and moderate depression, the benefits were small. The problem with the Kirsch analysis — and none of the major press reports considered this shortcoming — is that the F.D.A. material is ill suited to answer questions about mild depression.

As a condition for drug approval, the F.D.A. requires drug companies to demonstrate a medicine’s efficacy in at least two trials. Trials in which neither the new drug nor an older, established drug is distinguishable from a placebo are deemed “failed” and are disregarded or weighed lightly in the evaluation. Consequently, companies rushing to get medications to market have had an incentive to run quick, sloppy trials.

Often subjects who don’t really have depression are included — and (no surprise) weeks down the road they are not depressed. People may exaggerate their symptoms to get free care or incentive payments offered in trials. Other, perfectly honest subjects participate when they are at their worst and then spontaneously return to their usual, lower, level of depression.

THIS improvement may have nothing to do with faith in dummy pills; it is an artifact of the recruitment process. Still, the recoveries are called “placebo responses,” and in the F.D.A. data they have been steadily on the rise. In some studies, 40 percent of subjects not receiving medication get better.

The problem is so big that entrepreneurs have founded businesses promising to identify genuinely ill research subjects. The companies use video links to screen patients at central locations where (contrary to the practice at centers where trials are run) reviewers have no incentives for enrolling subjects. In early comparisons, off-site raters rejected about 40 percent of subjects who had been accepted locally — on the ground that those subjects did not have severe enough symptoms to qualify for treatment. If this result is typical, many subjects labeled mildly depressed in the F.D.A. data don’t have depression and might well respond to placebos as readily as to antidepressants.

Nonetheless, the F.D.A. mostly gets it right. To simplify a complex matter: there are two sorts of studies that are done on drugs: broad trials and narrow trials. Broad trials, like those done to evaluate new drugs, can be difficult these days, because many antidepressants are available as generics. Who volunteers to take an untested remedy? Research subjects are likely to be an odd bunch.

Narrow studies, done on those with specific disorders, tend to be more reliable. Recruitment of subjects is straightforward; no one’s walking off the street to enter a trial for stroke patients. Narrow studies have identified many specific indications for antidepressants, such as depression in neurological disorders, including multiple sclerosis and epilepsy; depression caused by interferon, a medication used to treat hepatitis and melanoma; and anxiety disorders in children.

New ones regularly emerge. The June issue of Surgery Today features a study in which elderly female cardiac patients who had had emergency operations and were given antidepressants experienced less depression, shorter hospital stays and fewer deaths in the hospital.

Broad studies tend to be most trustworthy when they look at patients with sustained illness. A reliable finding is that antidepressants work for chronic and recurrent mild depression, the condition called dysthymia. More than half of patients on medicine get better, compared to less than a third taking a placebo. (This level of efficacy — far from ideal — is typical across a range of conditions in which antidepressants outperform placebos.) Similarly, even the analyses that doubt the usefulness of antidepressants find that they help with severe depression.

In fact, antidepressants appear to have effects across the depressive spectrum. Scattered studies suggest that antidepressants bolster confidence or diminish emotional vulnerability — for people with depression but also for healthy people. In the depressed, the decrease in what is called neuroticism seems to protect against further episodes. Because neuroticism is not a core symptom of depression, most outcome trials don’t measure this change, but we can see why patients and doctors might consider it beneficial.

Similarly, in rodent and primate trials, antidepressants have broad effects on both healthy animals and animals with conditions that resemble mood disruptions in humans.

One reason the F.D.A. manages to identify useful medicines is that it looks at a range of evidence. It encourages companies to submit “maintenance studies.” In these trials, researchers take patients who are doing well on medication and switch some to dummy pills. If the drugs are acting as placebos, switching should do nothing. In an analysis that looked at maintenance studies for 4,410 patients with a range of severity levels, antidepressants cut the odds of relapse by 70 percent. These results, rarely referenced in the antidepressant-as-placebo literature, hardly suggest that the usefulness of the drugs is all in patients’ heads.

The other round of media articles questioning antidepressants came in response to a seemingly minor study engineered to highlight placebo responses. One effort to mute the placebo effect in drug trials involves using a “washout period” during which all subjects get a dummy pill for up to two weeks. Those who report prompt relief are dropped; the study proceeds with those who remain symptomatic, with half getting the active medication. In light of subject recruitment problems, this approach has obvious appeal.

Dr. DeRubeis, an authority on cognitive behavioral psychotherapy, has argued that the washout method plays down the placebo effect. Last year, Dr. DeRubeis and his colleagues published a highly specific statistical analysis. From a large body of research, they discarded trials that used washouts, as well as those that focused on dysthymia or subtypes of depression. The team deemed only six studies, from over 2,000, suitable for review. An odd collection they were. Only studies using Paxil and imipramine, a medicine introduced in the 1950s, made the cut — and other research had found Paxil to be among the least effective of the new antidepressants. One of the imipramine studies used a very low dose of the drug. The largest study Dr. DeRubeis identified was his own. In 2005, he conducted a trial in which Paxil did slightly better than psychotherapy and significantly better than a placebo — but apparently much of the drug response occurred in sicker patients.

Building an overview around your own research is problematic. Generally, you use your study to build a hypothesis; you then test the theory on fresh data. Critics questioned other aspects of Dr. DeRubeis’s math. In a re-analysis using fewer assumptions, Dr. DeRubeis found that his core result (less effect for healthier patients) now fell just shy of statistical significance. Overall, the medications looked best for very severe depression and had only slight benefits for mild depression — but this study, looking at weak treatments and intentionally maximized placebo effects, could not quite meet the scientific standard for a firm conclusion. And yet, the publication of the no-washout paper produced a new round of news reports that antidepressants were placebos.

In the end, the much heralded overview analyses look to be editorials with numbers attached. The intent, presumably to right the balance between psychotherapy and medication in the treatment of mild depression, may be admirable, but the data bearing on the question is messy.

As for the news media’s uncritical embrace of debunking studies, my guess, based on regular contact with reporters, is that a number of forces are at work. Misdeeds — from hiding study results to paying off doctors — have made Big Pharma an inviting and, frankly, an appropriate target. (It’s a favorite of Dr. Angell’s.) Antidepressants have something like celebrity status; exposing them makes headlines.

It is hard to locate the judicious stance with regard to antidepressants and moderate mood disorder. In my 1993 book, “Listening to Prozac,” I wrote, “To my mind, psychotherapy remains the single most helpful technology for the treatment of minor depression and anxiety.” In 2003, in “Against Depression,” I highlighted research that suggested antidepressants influence mood only indirectly. It may be that the drugs are “permissive,” removing roadblocks to self-healing.

That model might predict that in truth the drugs would be more effective in severe disorders. If antidepressants act by usefully perturbing a brain that’s “stuck,” then people who retain some natural resilience would see a lesser benefit. That said, the result that the debunking analyses propose remains implausible: antidepressants help in severe depression, depressive subtypes, chronic minor depression, social unease and a range of conditions modeled in mice and monkeys — but uniquely not in isolated episodes of mild depression in humans.

Better designed research may tell us whether there is a point on the continuum of mood disorder where antidepressants cease to work. If I had to put down my marker now — and effectively, as a practitioner, I do — I’d bet that “stuckness” applies all along the line, that when mildly depressed patients respond to medication, more often than not we’re seeing true drug effects. Still, my approach with mild depression is to begin treatments with psychotherapy. I aim to use drugs sparingly. They have side effects, some of them serious. Antidepressants help with strokes, but surveys also show them to predispose to stroke. But if psychotherapy leads to only slow progress, I will recommend adding medicines. With a higher frequency and stronger potency than what we see in the literature, they seem to help.

My own beliefs aside, it is dangerous for the press to hammer away at the theme that antidepressants are placebos. They’re not. To give the impression that they are is to cause needless suffering.

As for my friend, he had made no progress before his neurologists prescribed antidepressants. Since, he has shown a slow return of motor function. As is true with much that we see in clinical medicine, the cause of this change is unknowable. But antidepressants are a reasonable element in the treatment — because they do seem to make the brain more flexible, and they’ve earned their place in the doctor’s satchel.

How to Discontinue Antidepressant Medication

Mary Duenwald : NY Times Article : May 25, 2004

Antidepressants

Now that the Food and Drug Administration has warned Americans taking antidepressants to be on the lookout for potentially harmful side effects, including severe restlessness and suicidal thinking, some people may end up stopping the drugs but going off antidepressants can bring its own problems.

Stopping cold turkey can cause an array of troublesome symptoms, the most common being dizziness, which can last for days on end. Flu-like feelings, including nausea, headache and fatigue, are also common, as are intense feelings of anxiety, irritability or sadness. Some patients experience alarming sensations of tingling or burning in various parts of the body; ringing in the ears; blurred vision; or flashing lights before the eyes. Some people even describe a feeling of shock waves pulsing through their arms and legs, as if they had been zapped with a jolt of electricity, a condition sometimes called lightning-bolt syndrome.

"The feeling can be really abrupt, like a quick jerk of the muscle," said Dr. Richard C. Shelton, a professor of psychiatry at Vanderbilt University. "It's not painful, but it can be very frightening to people."

Internet bulletin boards and Web sites devoted to antidepressant withdrawal chronicle the crying spells, vertigo and nightmares that people sometimes experience.

"I feel like my brain is floating in Jell-O, slamming into the sides of my skull every time I move my head or my eyes," one person wrote.

Another described palpitations, night sweats and "bloody hideous nightmares."

To avoid such symptoms, or at least hold them to a minimum, the drugs need to be tapered gradually in most cases, and that means quitting under a doctor's supervision. Psychiatrists say it is unwise for people who are taking antidepressants simply to quit on their own.

In its warning, issued in March, the F.D.A. urged doctors to closely monitor patients taking antidepressants, especially during the first weeks of therapy or when changing dosage. Signs of trouble, the agency said, could include suicidal thoughts, severe restlessness, anxiety, hostility or insomnia. Though an association between antidepressants and suicidal thinking or behavior has not been proved, unpublished studies suggesting the possibility of such a link in children and adolescents have caused concern. The F.D.A. is still investigating the issue.

The drugs most likely to produce withdrawal symptoms act on the brain chemical serotonin. These drugs work by blocking the action of a protein in the brain that normally transports serotonin out of the synapses, the spaces between brain cells. With the transporter protein blocked, serotonin lingers in the synapses, and that can have a positive effect on mood.

When the drug is taken away, there is suddenly less serotonin in the synapses. Serotonin receptors in the brain, accustomed to a larger supply of the neurotransmitter, may take days or weeks to adjust, said Dr. Ephrain C. Azmitia, a psychopharmacologist at New York University.

"You get a precipitous drop in all the things that serotonin does in the brain, including its effects on appetite, sleep, sensory perception and emotions," Dr. Shelton said.

Not everyone experiences withdrawal symptoms. Studies suggest that only 10 to 20 percent of patients have significant problems, said Dr. Jerrold F. Rosenbaum, chief of psychiatry at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. And some patients find the effects less intense or bothersome than others.

Doctors say people who have been taking especially large doses of a drug for many years may be somewhat more vulnerable. Which drug a patient is taking also makes a difference. Some are stronger than others, and some are metabolized by the body more quickly.

The longer a drug's half-life - the time it takes for half the amount of drug in the body to be eliminated - the less likely it is to cause withdrawal problems. Eli Lilly's Prozac, for example, has a long half-life, remaining in the body for days or even weeks after someone stops taking it. As a result, people who take it are less likely to experience withdrawal effects.

"With Prozac, it can take six weeks for any symptoms to occur," Dr. Rosenbaum said, and even then the effects are mild, with about 5 to 6 percent of people experiencing mild dizziness.

GlaxoSmithKline's Paxil, on the other hand, generally leaves the body in a day or two. Effexor, made by Wyeth, disappears faster still.

"When you look at these drugs with a very short half-life, almost everybody who quits abruptly experiences at least some symptoms, some dizziness," Dr. Shelton said. "And about half of people have more significant symptoms."

For this reason, psychiatrists advise patients taking antidepressants to avoid skipping doses. People who take Paxil or Effexor sometimes experience withdrawal symptoms when they forget to take their pill for a day or two.

"With Effexor, if you miss your morning dose, you can be in withdrawal by the afternoon," said Dr. Joseph P. Glenmullen, a psychiatrist at Harvard and the author of "Prozac Backlash."

Zoloft, made by Pfizer, is somewhere in the middle - more likely than Prozac to cause withdrawal symptoms, but much less likely to do so than Paxil and Effexor. Celexa and Lexapro, antidepressants that are made by Forrest Laboratories and that act on serotonin, are also somewhere in the intermediate range, Dr. Rosenbaum said.

Cymbalta, a new antidepressant from Lilly that is expected to win F.D.A. approval later this year, will probably also fall in the middle, he said.

Wellbutrin, an antidepressant also marketed as Zyban, does not work directly on serotonin in the brain. As a result, doctors say, the drug, made by GlaxoSmithKline, does not seem to cause withdrawal symptoms when patients stop taking it.

The withdrawal symptoms do not mean that antidepressants are addictive, experts say. People who are coming off the drug do not crave it, as addicts might crave heroin or cocaine, and they do not seek higher and higher doses over time.

"There's a lot of misperception about that," said Dr. Alan F. Schatzberg, a psychopharmacologist who is chairman of psychiatry at Stanford University School of Medicine.

For that reason, many doctors describe the effects produced by stopping antidepressants as a "discontinuation syndrome" rather than as withdrawal.

Yet the symptoms can be troublesome enough to prompt some patients to go back on their medications.

To help patients stop taking an antidepressant, most doctors use a strategy of gradually tapering the drug over time. With Prozac, stepping down the dosage for a week to 10 days may be enough to get patients off it comfortably, Dr. Shelton said.

With Paxil or Effexor, on the other hand, the process may take many weeks or months. Dr. Shelton said he often brings his patients down from the drugs in five-milligram increments, with each stage lasting from five days to a week. A person taking 50 milligrams of Paxil, for example, would be advised to go down to 45 milligrams for one week, then step down to 40 milligrams, and so on.

The riskiest period, Dr. Schatzberg said, comes at the end, when even small increments of tapering can have a big impact on serotonin. "The taper at the bottom end often needs to go slower than it does at the top end," Dr. Schatzberg said.

For people who are having difficulty withdrawing from Paxil or Effexor, doctors sometimes prescribe a three-day dose of Prozac toward the end of the withdrawal period. With its longer half-life, Prozac can ensure that serotonin levels readjust more gradually.

Even when patients are entirely off the drugs, they may still experience some symptoms, but usually only for a few days and rarely for more than two weeks, doctors say.

Sadness and anxiety that persist longer than that may be signs that a patient is experiencing a return of the depression. So it is important to distinguish withdrawal from a relapse of illness.

"Just because you're stopping a drug," Dr. Rosenbaum said, "doesn't mean you don't need it."

Antidepressants should list new risks: FDA

July 19, 2006

Information about risks to newborns and migraine sufferers linked to some of the world's most widely used antidepressants should be added to the drug labels, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration said on Wednesday.

The FDA warned that taking antidepressants known as SSRIs -- including Prozac and Zoloft -- or certain SNRIs in combination with migraine drugs known as triptans could result in a life-threatening condition called serotonin syndrome.

It also warned consumers about the risk of a fatal lung condition in newborns whose mothers took SSRIs during pregnancy. The agency added it was seeking more information about persistent pulmonary hypertension in newborns from the drugs.

The agency asked drug makers to list the potential risks on their drug labels.

The SNRIs, or selective serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, cited by the FDA are Lilly's drug Cymbalta and Wyeth's Effexor.

Triptan migraine drugs include Glaxo's Imitrex and Amerge, Johnson & Johnson's Axert, Endo Pharmaceutical's Frova, Merck's Maxalt, Pfizer's Relpax and AstraZeneca's Zomig.

The agency advised patients to talk to their doctors about deciding whether to continue taking the drugs.

Antidepressants Rated Low Risk in Pregnancy

Benedict Carey : NY Times Article : June 28, 2007

Taking an antidepressant like Prozac may increase a pregnant woman’s risk of having a baby with a birth defect, but the chances appear remote and confined to a few rare defects, researchers are reporting today.

The findings, appearing in two studies in The New England Journal of Medicine, support doctors’ assurances that antidepressants are not a major cause of serious physical problems in newborns.

But the studies did not include enough cases to adequately assess risk of many rare defects; nor did they include information on how long women were taking antidepressants or at what doses. The studies did not evaluate behavioral effects either; previous research has found that babies suffer withdrawal effects if they have been exposed to antidepressants in the womb, and that may have implications for later behavior.

“These are important papers, but they don’t close the questions of whether there are major effects” of these drugs on developing babies, said Dr. Timothy Oberlander, a developmental pediatrician at the University of British Columbia, who was not involved in the studies. “There are many more chapters in this story yet to be told.”

In both studies, researchers interviewed mothers of more than 9,500 infants with birth defects, including cleft palate and heart valve problems. They found that mothers who remembered being on antidepressants like Zoloft, Paxil or Prozac while pregnant were at no higher risk for most defects than a control group of women who said they had not taken antidepressants.

There were a few exceptions. One of the studies, led by Carol Louik of Boston University and financed in part by the drug makers GlaxoSmithKline and Sanofi-Aventis, found that use of Paxil was associated with an increased risk of a rare heart defect, which the company had previously reported.

The other study, led by Sura Alwan of the University of British Columbia, found that use of antidepressants increased the risk of craniosynostosis, a condition in which the bones in the skull fuse prematurely. Rare gastric and neural tube defects may also be more common in babies exposed to the medication the studies suggested.

- So if you are planning on discontinuing your medication, please discuss with me.

- Remember it is best to slowly taper the dose.