- RETIREMENT ANNOUNCEMENT

- HOME PAGE

- "MYCHART" the new patient portal

- BELMONT MEDICAL ASSOCIATES

- MOUNT AUBURN HOSPITAL

- EMERGENCIES

- PRACTICE PHILOSOPHY

- MY RESUME

- TELEMEDICINE CONSULTATION

- CONTACT ME

- LAB RESULTS

- ePRESCRIPTIONS

- eREFERRALS

- RECORD RELEASE

- MEDICAL SCRIBE

- PHYSICIAN ASSISTANT (PA)

- Medicare Annual Wellness Visit

- Case management/Social work

- Quality Care Measures

- Emergency closing notice

- FEEDBACK

- Talking to your doctor

- Choosing..... and losing a doctor

- INDEX A - Z

- ALLERGIC REACTIONS

- Alternative Medicine

- Alzheimer's Disease

- Bladder Problems

- Blood disorders

- Cancer Concerns

- GENETIC TESTING FOR HEREDITARY CANCER

- Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

- Controversial Concerns

- CPR : Learn and save a life

- CRP : Inflammatory marker

- Diabetes Management

- Dizziness, Vertigo,Tinnitus and Hearing Loss

- EXERCISE

- FEMALE HEALTH

-

GASTROINTESTINAL topics

- Appendicitis

- BRAT diet

- Celiac Disease or Sprue

- Crohn's Disease

- Gastroenterologists for Colon Cancer Screening

- Colonoscopy PREP

- Constipation

- Gluten sensitivity, but not celiac disease

- Heartburn and GERD

- Hemorrhoids and Anal fissure

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- NASH : Non Alcoholic Steato Hepatitis

- FEET PROBLEMS

- HEART RELATED topics

-

INFECTIOUS DISEASES

- Antibiotic Resistance

- Cat bites >

- Clostridia difficile infection - the "antibiotic associated germ"

- CORONA VIRUS

- Dengue Fever and Chikungunya Fever

- Food borne illnesses

- Shingles Vaccine

- Hepatitis B

- Hepatitis C

- Herpes

- Influenza

- Helicobacter pylori - the "ulcer germ"

- HIV Screening

- Lyme and other tick borne diseases

- Measles

- Meningitis

- MRSA (Staph infection)

- Norovirus

- Sexually Transmitted Diseases

- Shingles (Herpes Zoster)

- Sinusitis

- West Nile Virus

- Whooping Cough (Pertussis)

- Zika virus and pregnancy

- INSURANCE related topics

- KIDNEY STONES

- LEG CRAMPS

- LIBRARY for patients

- LIFE DECISIONS

- MALE HEALTH

- Medication/Drug side effects

- MEDICAL MARIJUANA

- MENTAL HEALTH

- Miscellaneous Articles

-

NUTRITION - EXERCISE - WEIGHT

- Cholesterol : New guidelines for treatment

- Advice to lower your cholesterol

- Cholesterol : Control

- Cholesterol : Raising your HDL Level

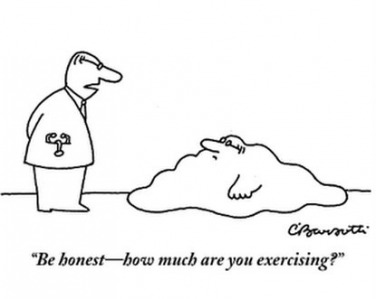

- Exercise

- Food : Making Smart Choices

- Food : Making Poor Choices

- Food : Grape Fruit and Drug Interaction

- Food : Vitamins, Minerals and Supplements

- Omega 3 fatty acids

- Vitamin B12 deficiency

- Vitamin D

- Weight Loss

- ORTHOPEDICS

- PAIN

- PATIENTS' RIGHTS

- SKIN

- SLEEP

- SMOKING

- STROKE

- THYROID

- SUBSTANCE ABUSE

- Travel and Vaccination

- TREMOR

- Warfarin Anticoagulation

- OTHER STUFF FOLLOWS

- Fact or Opinion?

- Hippocratic Oath

- FREE ADVICE.......for what its worth!

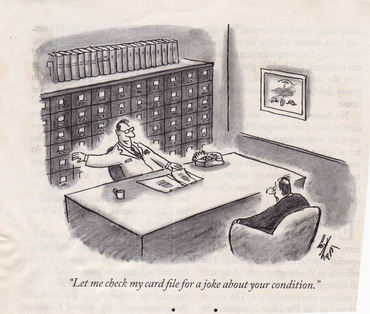

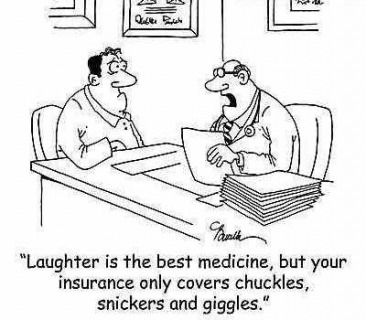

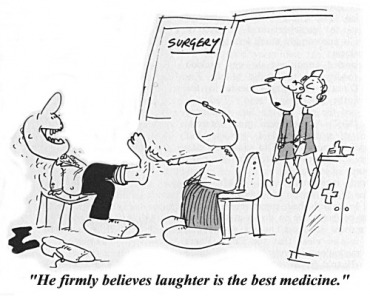

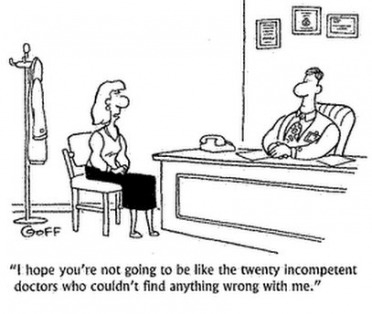

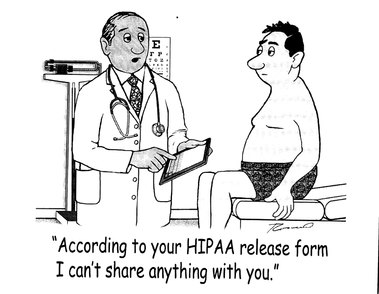

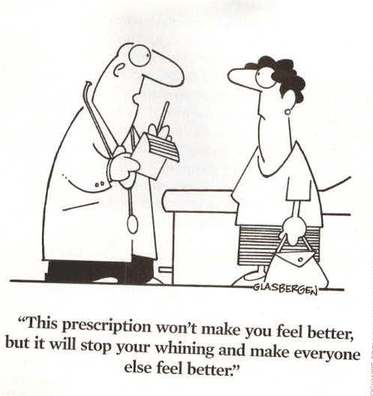

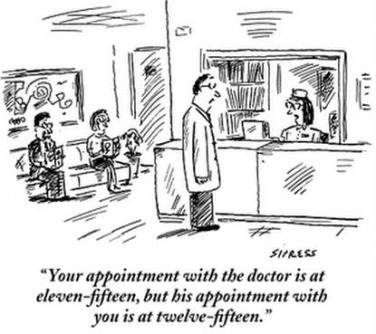

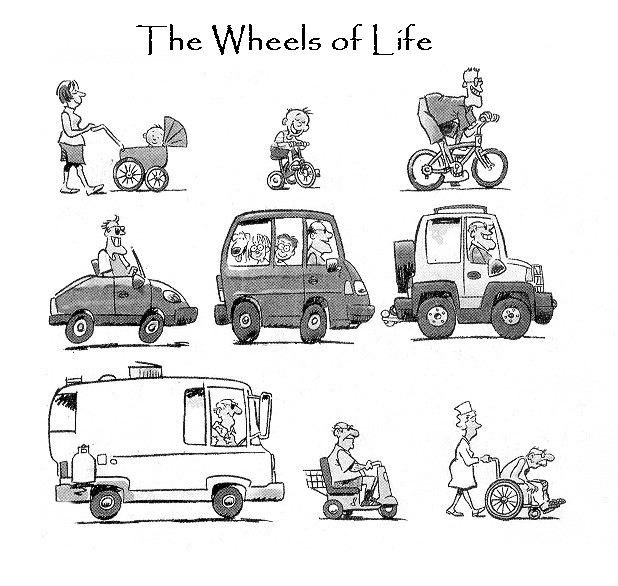

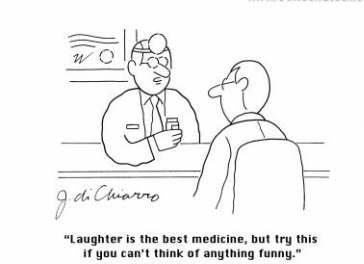

- LAUGHTER.....is the best medicine

- Physicians Pet Peeves

- PHOTO ALBUM - its not all work!

- Cape Town, South Africa

- Tribute page

- The 100 Club

- Free Wi-Fi

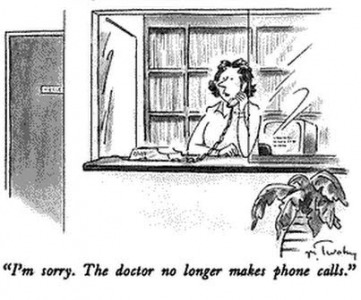

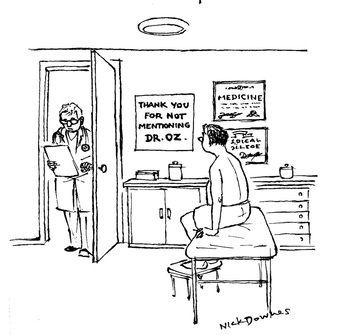

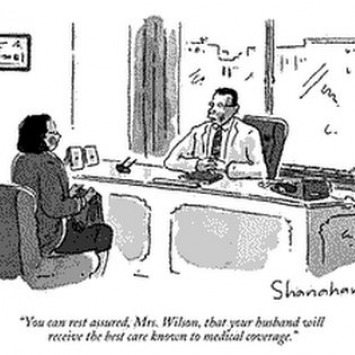

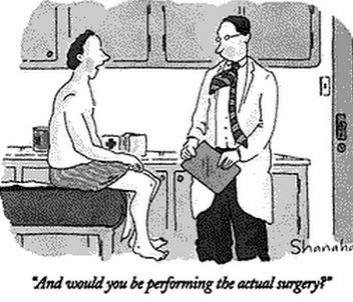

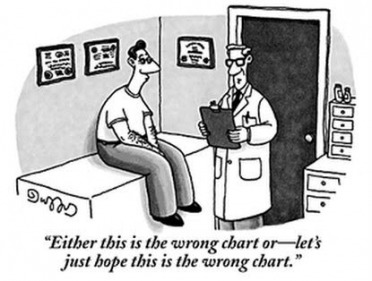

MEDICAL HUMOR

My thanks, appreciation and gratitude goes to these remarkably talented cartoonists.

I have shamelessly "borrowed" their work. I do want them to know that their work lives on and is saving some people a fortune in money that they would normally have had to spend on prescription medications to keep themselves sane!

"Were you also a patient of Dr Kaye?"

"Whoa........That's way too much information!"

Using humor in the doctor’s office

By Dr. Suzanne Koven : Globe Correspondent : November 26, 2012

At the festivities marking the end of our grueling first two years of medical school, I was voted the funniest girl in my class. I hasten to add, lest this admission seem immodest, that the competition was not very stiff. Medical students (and the doctors they become) are a pretty serious lot. And yet, humor had always been so much a part of my life that it seemed unlikely I could subtract it from my identity when I added “M.D.” to my name.

I come from a family of joke tellers, and have a large repertoire myself. My father, an orthopedic surgeon, was a quiet man, not much for small talk (or big talk, for that matter), but he became uncharacteristically garrulous when he told a funny story. Dad stretched out the lead-in to a joke to such an extent — Have you heard this one? The one about the man? You know, the man and the dog? — that the preamble was often funnier, and longer, than the joke itself.

I know that he believed in the therapeutic power of humor. Once, I saw a cheerful, elderly patient with him in his office. After she’d gone, I wondered how she managed to get on so well. As I listed her many ailments — lung cancer, fractures, tuberculosis of the spine — my father interrupted: “You forgot to mention her smile.”

The medical benefits of laughter were recognized in Hippocrates’ time, but it was not until 1979, with the publication of journalist Norman Cousins’ best-selling book, “Anatomy of an Illness,” that the humor therapy movement gained momentum. Cousins described watching Marx Brothers movies and episodes of “Candid Camera” to treat his debilitating arthritis. Bernie Siegel’s popular “Love, Medicine, and Miracles” also encouraged self-healing through humor, as did comedian Gilda Radner, during her illness with ovarian cancer.

In recent years, medical professionals, too, have become more interested in humor. Research has shown that laughter can alleviate anxiety, improve immune function, facilitate blood flow, and decrease the discomfort children experience during invasive procedures. The Association for Applied and Therapeutic Humor brings together hundreds of clowns, comics, and clinicians at its annual conference.

Incorporating humor into my own medical practice was not easy, initially. I feared transgressing boundaries, being inappropriate, not being taken seriously — especially as a young doctor.

My first clinical use of humor was entirely unplanned. I was a medical student rotating through surgery, on night duty in the emergency room. A man about my age, kind of a tough guy, came in with what turned out to be an abscess in his scrotum. He took one look at me and declared that he wasn’t taking off his pants for a lady.

It may have been the hour (2 a.m.) or my mental state (exhausted), but something made me announce: “Listen, if I find anything in there I’ve never seen before, I’ll shoot it.”

He grinned, said, “Hey, you’re OK!” and dropped his drawers.

As I moved beyond training and into my own practice, I used humor hesitantly. I remember the first patient to whom I told a joke. He had given up red meat to improve his cholesterol and told me he was eating so much fish and chicken he didn’t know whether he should swim or cluck. It seemed to be an opening to tell him about the man who’s advised by his doctor to give up sex, alcohol, and rich food. “Will I live longer, Doc?” the patient asks. “No, it’ll just seem longer,” answers the doctor.

OK, so it’s not a exactly a side splitter, but he liked it, as have many other patients of mine. I think that’s because a joke — any joke — breaks down barriers, including between a doctor and a patient. That odd, primitive vocal outburst we emit in response to something funny is so uniquely human that it’s hard to imagine a better way to remind ourselves of our common humanity than by sharing a joke with someone.

Any seasoned clinician will tell you that one of the pleasures of a long-term practice is that, with time, you become more comfortable being yourself. You also become better able to identify those patients from whom you must hold yourself back. As the years have passed I’ve told more jokes to fewer patients — the same patients who tell me jokes in return.

I still sometimes underestimate the value of humor, though.

The other day I visited a patient in the hospital, a woman who loves to tell jokes. I was concentrating on her chart, trying to figure out why her condition wasn’t improving as expected.

“I got a good one for you,” she said. I cut her off.

“Not just now,” I replied. “I need to go check your labs.”

I congratulated myself, briefly, on my restraint. Surely there are times when humor simply isn’t appropriate? But later I got to thinking about how jokes work. One person reveals information bit by bit, and then springs a surprise on the listener. Freud wrote of how a joke teller wields control, creating tension, and then choosing the precise moment when the tension will be released.

Maybe what my patient needed at that moment — uncertain about her fate, tucked too tightly into her hospital bed, tethered to various tubes and wires — was to be in control.

Maybe the most healing thing I could have done for her right then was to let her hit me with the punch line.

By Dr. Suzanne Koven : Globe Correspondent : November 26, 2012

At the festivities marking the end of our grueling first two years of medical school, I was voted the funniest girl in my class. I hasten to add, lest this admission seem immodest, that the competition was not very stiff. Medical students (and the doctors they become) are a pretty serious lot. And yet, humor had always been so much a part of my life that it seemed unlikely I could subtract it from my identity when I added “M.D.” to my name.

I come from a family of joke tellers, and have a large repertoire myself. My father, an orthopedic surgeon, was a quiet man, not much for small talk (or big talk, for that matter), but he became uncharacteristically garrulous when he told a funny story. Dad stretched out the lead-in to a joke to such an extent — Have you heard this one? The one about the man? You know, the man and the dog? — that the preamble was often funnier, and longer, than the joke itself.

I know that he believed in the therapeutic power of humor. Once, I saw a cheerful, elderly patient with him in his office. After she’d gone, I wondered how she managed to get on so well. As I listed her many ailments — lung cancer, fractures, tuberculosis of the spine — my father interrupted: “You forgot to mention her smile.”

The medical benefits of laughter were recognized in Hippocrates’ time, but it was not until 1979, with the publication of journalist Norman Cousins’ best-selling book, “Anatomy of an Illness,” that the humor therapy movement gained momentum. Cousins described watching Marx Brothers movies and episodes of “Candid Camera” to treat his debilitating arthritis. Bernie Siegel’s popular “Love, Medicine, and Miracles” also encouraged self-healing through humor, as did comedian Gilda Radner, during her illness with ovarian cancer.

In recent years, medical professionals, too, have become more interested in humor. Research has shown that laughter can alleviate anxiety, improve immune function, facilitate blood flow, and decrease the discomfort children experience during invasive procedures. The Association for Applied and Therapeutic Humor brings together hundreds of clowns, comics, and clinicians at its annual conference.

Incorporating humor into my own medical practice was not easy, initially. I feared transgressing boundaries, being inappropriate, not being taken seriously — especially as a young doctor.

My first clinical use of humor was entirely unplanned. I was a medical student rotating through surgery, on night duty in the emergency room. A man about my age, kind of a tough guy, came in with what turned out to be an abscess in his scrotum. He took one look at me and declared that he wasn’t taking off his pants for a lady.

It may have been the hour (2 a.m.) or my mental state (exhausted), but something made me announce: “Listen, if I find anything in there I’ve never seen before, I’ll shoot it.”

He grinned, said, “Hey, you’re OK!” and dropped his drawers.

As I moved beyond training and into my own practice, I used humor hesitantly. I remember the first patient to whom I told a joke. He had given up red meat to improve his cholesterol and told me he was eating so much fish and chicken he didn’t know whether he should swim or cluck. It seemed to be an opening to tell him about the man who’s advised by his doctor to give up sex, alcohol, and rich food. “Will I live longer, Doc?” the patient asks. “No, it’ll just seem longer,” answers the doctor.

OK, so it’s not a exactly a side splitter, but he liked it, as have many other patients of mine. I think that’s because a joke — any joke — breaks down barriers, including between a doctor and a patient. That odd, primitive vocal outburst we emit in response to something funny is so uniquely human that it’s hard to imagine a better way to remind ourselves of our common humanity than by sharing a joke with someone.

Any seasoned clinician will tell you that one of the pleasures of a long-term practice is that, with time, you become more comfortable being yourself. You also become better able to identify those patients from whom you must hold yourself back. As the years have passed I’ve told more jokes to fewer patients — the same patients who tell me jokes in return.

I still sometimes underestimate the value of humor, though.

The other day I visited a patient in the hospital, a woman who loves to tell jokes. I was concentrating on her chart, trying to figure out why her condition wasn’t improving as expected.

“I got a good one for you,” she said. I cut her off.

“Not just now,” I replied. “I need to go check your labs.”

I congratulated myself, briefly, on my restraint. Surely there are times when humor simply isn’t appropriate? But later I got to thinking about how jokes work. One person reveals information bit by bit, and then springs a surprise on the listener. Freud wrote of how a joke teller wields control, creating tension, and then choosing the precise moment when the tension will be released.

Maybe what my patient needed at that moment — uncertain about her fate, tucked too tightly into her hospital bed, tethered to various tubes and wires — was to be in control.

Maybe the most healing thing I could have done for her right then was to let her hit me with the punch line.

If you reached this point and have seen all the cartoons, you can add one extra year to your life expectancy.

If you come across a funny medical cartoon, that you think should be added to this page, be sure to email it to me.

Yours in laughter

THK

If you come across a funny medical cartoon, that you think should be added to this page, be sure to email it to me.

Yours in laughter

THK

Who Says Laughter’s the Best Medicine?

By Jan Hoffman : NY Times : December 20, 2013

Just in time to protect patients from the dangers of holiday cheer, a new scholarly review from a British medical journal describes many harmful effects wrought by laughter.

Among the alarms it sounds: The force of laughing can dislocate jaws, prompt asthma attacks, cause headaches, make hernias protrude. It can provoke cardiac arrhythmia, syncope or even emphysema (this last, according to a clinical lecturer in 1892).

Laughter can trigger the rare but possibly grievous Pilgaard-Dahl and Boerhaave’s syndromes (see explanation below).

And ponder, briefly, the mortifying impact of sustained laughter on the urinary tract (detailed in a 1982 The Lancet paper entitled “Giggle Incontinence”).

At the very least, the new review could be considered an affirmation for the perpetually dour. If 2013 was the year of the worried well, the authors imply that 2014 is poised to be the year of the humorless healthy.

The analysis, “Laughter and MIRTH (Methodical Investigation of Risibility, Therapeutic and Harmful),” was drawn from about 5,000 studies. It appears in BMJ, formerly known as The British Medical Journal, which for more than 30 years has traditionally featured rigorously researched but lighthearted articles in its Christmas issue. A deputy editor, Dr. Tony Delamothe, said that the MIRTH study was indeed peer-reviewed — presumably by a doctor with a carefully managed sense or humor (or humour).

This year, companion studies in the issue include “Were James Bond’s drinks shaken because of alcohol induced tremor?” , “The survival time of chocolates on hospital wards: covert observational study,” and “Operating room safety: the 10 point plan to safe flinging” (among the cautions: “Before flinging, identify your target and the area beyond it” and “Never fling an instrument straight up into the air”).

Last spring the co-authors, Dr. Robin E. Ferner, an honorary professor of clinical pharmacology at the University of Birmingham, and Jeffrey K. Aronson, a fellow in clinical pharmacology at Oxford, who study the benefits and harms of medicines, discussed what benefit-harm they could explore in a gambit to win a coveted berth in BMJ’s Christmas issue. According to Dr. Delamothe, BMJ receives nearly 120 submissions and accepts about 30.

Dr. Ferner and Dr. Aronson considered holiday foods, for example, but their tastes were not in concert. “He likes sweet wines and I like dry wines,” Dr. Ferner explained. Then they found common cause: ”But we both like dry humor.”

They winnowed down the papers that mentioned laughter to 785, putting them into three categories: benefits (85), harms (114) and conditions causing pathological laughter (586).

The question was timely, they argue, because BMJ had not addressed laughter in a serious fashion in over a century. In 1898, it had published a case study of heart failure in a 13-year-old girl following prolonged laughter. The next year, the laughter problem was raised again, when an editorial writer, in response to an Italian doctor’s suggestion that telling jokes could treat bronchitis, dismissively proposed the term “gelototherapy” (Gelos was the Greek god of laughter; in Italian, gelato is ice cream.).

Laughter as therapy was slow to gain traction: in 1928, The Journal of the American Medical Association gave short shrift to Dr. James J. Walsh’s book, “Laughter and Health.”

The harms, however, have been scrutinized. A 1997 discussion of Boerhaave’s syndrome, a spontaneous perforation of the esophagus, a rare though potentially lethal event, mentioned that one unusual precipitating cause is laughter.

Then there is the mysterious Pilgaard-Dahl syndrome, identified in a 2010 article as a pneumothorax in middle-aged male smokers induced by laughter. It takes its name from Ulf Pilgaard and Lisbet Dahl, the Danish revue performers.

“I don’t think of the Danes as uproariously funny,” Dr. Ferner said, “and, having seen their show on YouTube, I still don’t, though, of course, I don’t speak Danish.”

There were other respiratory threats occasioned by laughter, he said. The popping of alveoli (the air sacs in the lungs, which together typically contain about 600 million): “If you’re going to make asthmatics laugh heartily,” Dr. Ferner said, “they might want to have an inhaler by their side.” (This, extrapolated from a 1936 experiment on the mechanism of laughter in asthmatics.)

There are choking hazards, such as ingesting food during belly laughs.

The MIRTH review did take an even-handed, cost-benefit approach to laughter, noting ample evidence of its salutary effects. It concluded that laughter’s benefits included reduced anger, anxiety and stress; reduced cardiovascular tension, blood glucose concentration and risk of myocardial infarction. “The benefit-harm balance,” the authors wrote, “is probably favourable.”

Studies in recent years concluded that laughter “reduces arterial wall stiffness” and “improves endothelial function.” And a 2008 study of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease concluded that laughter inspired by Pello the clown improved lung function.

Indeed medical clowning has been observed and embraced. But one study left Dr. Ferner almost speechless. A 2011 fertility study reported that when a clown dressed as a chef de cuisine entertained would-be mothers for 12 to 15 minutes after in vitro fertilization and embryo transfers, the pregnancy rate was 36 percent, compared with 20 percent among a control group that was not entertained.

“Why a chef de cuisine?” Dr. Ferner asked plaintively.

Despite such a comprehensive look at the medical literature on laughter, Dr. Ferner felt there was still territory to be charted. “We don’t know how much laughter is safe,” he said. “There’s probably a U-shaped curve: laughter is good for you, but enormous amounts are bad, perhaps. It’s not a problem in England.”

Nonetheless, if you choose to peruse the MIRTH study or others in BMJ’s Christmas issue, the risk of outbursts of laughter, ranging from snickers to groans to guffaws, could be perilously high. You have been warned.