- RETIREMENT ANNOUNCEMENT

- HOME PAGE

- "MYCHART" the new patient portal

- BELMONT MEDICAL ASSOCIATES

- MOUNT AUBURN HOSPITAL

- EMERGENCIES

- PRACTICE PHILOSOPHY

- MY RESUME

- TELEMEDICINE CONSULTATION

- CONTACT ME

- LAB RESULTS

- ePRESCRIPTIONS

- eREFERRALS

- RECORD RELEASE

- MEDICAL SCRIBE

- PHYSICIAN ASSISTANT (PA)

- Medicare Annual Wellness Visit

- Case management/Social work

- Quality Care Measures

- Emergency closing notice

- FEEDBACK

- Talking to your doctor

- Choosing..... and losing a doctor

- INDEX A - Z

- ALLERGIC REACTIONS

- Alternative Medicine

- Alzheimer's Disease

- Bladder Problems

- Blood disorders

- Cancer Concerns

- GENETIC TESTING FOR HEREDITARY CANCER

- Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

- Controversial Concerns

- CPR : Learn and save a life

- CRP : Inflammatory marker

- Diabetes Management

- Dizziness, Vertigo,Tinnitus and Hearing Loss

- EXERCISE

- FEMALE HEALTH

-

GASTROINTESTINAL topics

- Appendicitis

- BRAT diet

- Celiac Disease or Sprue

- Crohn's Disease

- Gastroenterologists for Colon Cancer Screening

- Colonoscopy PREP

- Constipation

- Gluten sensitivity, but not celiac disease

- Heartburn and GERD

- Hemorrhoids and Anal fissure

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- NASH : Non Alcoholic Steato Hepatitis

- FEET PROBLEMS

- HEART RELATED topics

-

INFECTIOUS DISEASES

- Antibiotic Resistance

- Cat bites >

- Clostridia difficile infection - the "antibiotic associated germ"

- CORONA VIRUS

- Dengue Fever and Chikungunya Fever

- Food borne illnesses

- Shingles Vaccine

- Hepatitis B

- Hepatitis C

- Herpes

- Influenza

- Helicobacter pylori - the "ulcer germ"

- HIV Screening

- Lyme and other tick borne diseases

- Measles

- Meningitis

- MRSA (Staph infection)

- Norovirus

- Sexually Transmitted Diseases

- Shingles (Herpes Zoster)

- Sinusitis

- West Nile Virus

- Whooping Cough (Pertussis)

- Zika virus and pregnancy

- INSURANCE related topics

- KIDNEY STONES

- LEG CRAMPS

- LIBRARY for patients

- LIFE DECISIONS

- MALE HEALTH

- Medication/Drug side effects

- MEDICAL MARIJUANA

- MENTAL HEALTH

- Miscellaneous Articles

-

NUTRITION - EXERCISE - WEIGHT

- Cholesterol : New guidelines for treatment

- Advice to lower your cholesterol

- Cholesterol : Control

- Cholesterol : Raising your HDL Level

- Exercise

- Food : Making Smart Choices

- Food : Making Poor Choices

- Food : Grape Fruit and Drug Interaction

- Food : Vitamins, Minerals and Supplements

- Omega 3 fatty acids

- Vitamin B12 deficiency

- Vitamin D

- Weight Loss

- ORTHOPEDICS

- PAIN

- PATIENTS' RIGHTS

- SKIN

- SLEEP

- SMOKING

- STROKE

- THYROID

- SUBSTANCE ABUSE

- Travel and Vaccination

- TREMOR

- Warfarin Anticoagulation

- OTHER STUFF FOLLOWS

- Fact or Opinion?

- Hippocratic Oath

- FREE ADVICE.......for what its worth!

- LAUGHTER.....is the best medicine

- Physicians Pet Peeves

- PHOTO ALBUM - its not all work!

- Cape Town, South Africa

- Tribute page

- The 100 Club

- Free Wi-Fi

NOTICE ABOUT

LONG TERM USE OF FOSAMAX/ALENDRONATE

I am advising my patients who have taken a bisphosphonate (Fosamax/Actonel/Boniva)

for more than 5 years

to stop this type of medication as in some patients there is a change in the bone remodeling process making some bones more brittle and prone to spontaneous fracture. Read last article for more details.

"While it is not clear whether bisphosphonates are the cause, atypical femur fractures, a rare but serious type of thigh bone fracture, have been predominantly reported in patients taking bisphosphonates," particularly those taking the drugs for more than five years, the FDA said in a statement on 10/13/2010.

Osteoporosis

For more in depth information please check this link

Definition:

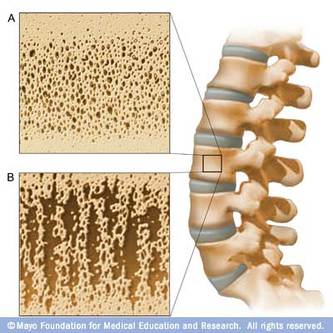

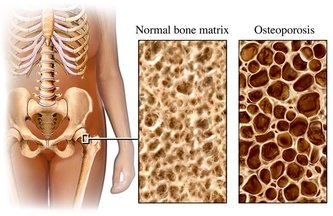

Osteoporosis is a condition of decreased bone mass. This leads to fragile bones which are at an increased risk for fractures. In fact, it will take much less stress to an osteoporotic bone to cause it to fracture. The term "porosis" means spongy, which describes the appearance of osteoporosis bones when they are broken in half and the inside is examined. Normal bone marrow has small holes within it, but a bone with osteoporosis will have much larger holes. The pictures below show a bone with osteoporosis with large spongy holes, and a normal bone with normal small passageways. In severe osteoporosis, this can be exaggerated much more than shown below.

Diagnosis:

There is no method of determining the actual structure of bones without actually removing a piece during a biopsy (which is not practical or necessary). Instead, the diagnosis of osteoporosis is based on special x-ray methods called densitometry. Densitometry will give accurate and precise measurements of the amount of bone (not their actual quality). This measurement is termed "bone mineral density" or BMD.

The World Health Organization "WHO" has established criteria for making the diagnosis of osteoporosis, as well as determining levels which predict higher chances of fractures. These criteria are based on comparing bone mineral density (BMD) in a particular patient with those of a 25 year old female. BMD values which fall well below the average for the 25 year old female (stated statistically as 2.5 standard deviations below the average) are diagnosed as "osteoporotic". If a patient has a BMD value less than the normal 25 year old female, but not 2.5 standard deviations below the average, the bone is said to be "osteopenic" (osteopenic means decreased bone mineral density, but not as sever as osteoporosis). Interestingly, although these criteria are widelyused, they were devised in a Caucasian female so there will be some differences when these levels are applied to non Caucasian females or to males in general. Despite this flaw, measurement of BMD is used daily and has proven to be very helpful in all groups. Some men will be subject to increased fracture rates when they have significantly less BMD than the predicted fracture level for women. In other words, some men will be at increased risk for fracture even when they have osteopenia.

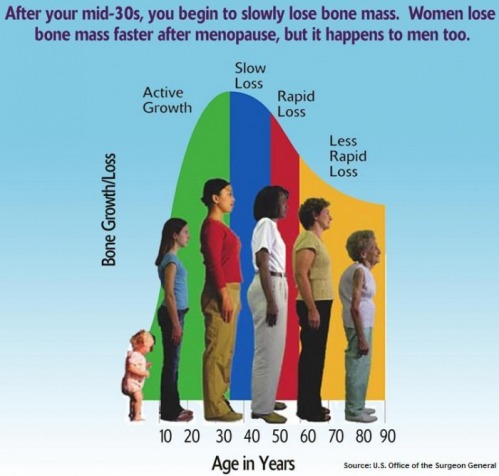

Osteoporosis is different from most other diseases or common illnesses in that there is no one single cause. The overall health of a person's bones is a function of many things ranging from how well the bones were formed as a youth, to the level of exercise the bones have seen over the years. During the first 20 years of life, the formation of bone is the most important factor, but after that point it is the prevention of bone loss which becomes most important. Anything which leads to decreased formation of bone early in life, or loss of bone structure later in life will lead to osteoporosis and fragile bones which are subject to fracture.

Daily calcium needs at different ages

Age

Amount of Daily Calcium

Infants

Birth to 6 months

400mg

Six months to 1 year

600mg

Children/Young Adults

One to 10 years

800 - 1,200 mg

11 to 24 years

1,200 - 1,500 mg

Adult Women

Pregnant or Lactating

1,200 - 1,500 mg

25 to 49 years (premenopausal)

1,000 mg

50 to 64 years (postmenopausal taking estrogen or similar hormone)

1,000 mg

50 to 64 years (postmenopausal not taking

estrogen or similar hormone)

1,500 mg

Over 65 years old

1,500 mg

Adult Men

25 to 64 years old

1,000 mg

Over 65 years old

1,500 mg

The American College of Physicians has issued a clinical practice guideline on screening men for osteoporosis. The guideline appears in the current Annals of Internal Medicine.

Thinking Twice About Calcium Supplements

By Jane E. Brody : NY Times : April 8, 2013

Americans seem to think that every health problem can be solved with a pill. And certainly many are, especially infectious diseases that succumb to antibiotics, antifungals and, increasingly, antivirals.

But that leaves a medical dictionary full of ailments that continue to plague people despite the best efforts of Big Pharma. Most are chronic health problems related to how Americans live, especially what we eat and drink, and don’t eat and drink, and how we move or don’t move. In our aging society, these ailments have pushed the annual cost of medical care into the trillions of dollars and threaten to break Medicare.

Osteoporosis is one of these increasingly prevalent and costly conditions. Although there are drugs to stanch the loss of bone and the debilitating fractures that often result, the remedies are costly, difficult to administer and sometimes have side effects that can be worse than the disease they are meant to counter.

This makes prevention the preferred and more cost-effective option. But efforts to prevent bone disease have focused on a pill, namely supplements of calcium, the mineral responsible for creating bone in youth that must be maintained throughout adult life, which now routinely extends to the 80s and 90s.

But as with many other pills once regarded as innocuous, the safety and efficacy of calcium supplements in preventing bone loss is being called into question.

In February, the United States Preventive Services Task Force recommended that postmenopausal women refrain from taking supplemental calcium and vitamin D. After reviewing more than 135 studies, the task force said there was little evidence that these supplements prevent fractures in healthy women.

Moreover, several studies have linked calcium supplements to an increased risk of heart attacks and death from cardiovascular disease. Others have found no effect, depending on the population studied and when calcium supplementation was begun.

The resulting controversy has left countless people, especially postmenopausal women, wondering whether they should be taking calcium. Given the conditional evidence currently available, the answer is not likely to be greeted enthusiastically by anyone other than dairy farmers, who supply the foods and drinks that are the country’s richest dietary sources of calcium.

The one indisputable fact is that the safest and probably the most effective source of calcium for strong bones and overall health is diet, not supplements. But few American adults, and a decreasing proportion of children and teenagers, consume enough dairy foods to get the recommended intakes of this essential mineral.

Milk consumption has taken a steady nose-dive in the last four decades, largely supplanted by sugared soft drinks that are now under fire as major contributors to obesity and Type 2 diabetes. Beyond age 20, when bone loss can begin to overtake bone formation, the typical man and woman in this country consumes less than one cup of milk a day. Likewise for teenage girls, who should be striving to maximize bone formation so that there is more in reserve when bone loss begins.

Yogurt, which ounce for ounce is an even better source of calcium than fluid milk, has achieved unprecedented popularity in recent years, but few consume it more than once a day, which doesn’t come close to meeting dietary needs. Frozen yogurt, which threatens to supplant ice cream as the nation’s most popular frozen dessert, has about half the amount of calcium as regular yogurt and only slightly more than ice cream. Both are far more caloric than nonfat milk.

The only other notable calcium-rich foods are tofu (when prepared with calcium); calcium-fortified orange juice, soy milk and rice milk; canned salmon and sardines (but only if you eat the bones); almonds; kale; and broccoli. But few people consume enough of these foods to obtain the calcium they need.

Calcium was long thought to protect the cardiovascular system. It helps to lower blood pressure and the risk of hypertension, a major contributor to heart disease. The Iowa Women’s Health Study linked higher calcium intakes in postmenopausal women to a reduced risk of heart disease deaths, though other long-term studies did not find such an association.

Controversy over calcium supplements arose when a combined analysis of 15 studies by Dr. Mark J. Bolland of the University of Auckland found that when calcium was taken without vitamin D (which enhances calcium absorption), the supplements increased the risk of heart attack by about 30 percent.

Dr. Bolland then reanalyzed data from the Women’s Health Initiative and found a 24 percent increased risk of heart attack among women who took calcium with or without vitamin D. In this case, the increased risk occurred only among those women assigned to take supplemental calcium who had not already been taking it when the study began.

Yet last December, in a report published online in Osteoporosis International, a team at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle reported that among 36,282 postmenopausal women participating in the Women’s Health Initiative, those taking 1,000 milligram supplements of calcium and 400 international units of vitamin D experienced a 35 percent reduced risk of hip fracture, and no increase in heart attacks during a seven-year follow-up.

In February yet another study, published online in JAMA Internal Medicine, found that among 388,229 men and women initially aged 50 to 71 and followed for an average of 12 years, supplemental calcium raised the risk of cardiovascular death by 20 percent among men — but not women. The increased risk was observed only among smokers.

Adding to these confusing results is the fact that none of the studies was specifically designed to assess the effects of calcium supplements on the chances of suffering a heart attack or stroke. This can cause unexpected aberrations in research findings.

One possible explanation for a link, the JAMA researchers said, is that a bolus of calcium that enters the blood stream through a supplement, but not gradually through dietary sources, can result in calcium deposits in arteries. Indeed, this is a known complication among patients with advanced kidney disease who take calcium supplements.

All the researchers agree that, given the widespread use of supplemental calcium, better studies are needed to clarify possible risks and benefits, and to whom they may apply.

Until such information is available, consumers seeking to preserve their bones would be wise to rely primarily on dietary sources of the mineral and to pursue regular weight-bearing or strength-building exercises, or both. Walking, running, weight lifting and working out on resistance machines is unquestionably effective and safe for most adults, if done properly.

Furthermore, the National Osteoporosis Foundation maintains that the findings of current studies and advice about supplements should “not apply to women with osteoporosis or broken bones after age 50 or those with significant risk factors for fracture.” For them, the benefits of calcium supplements are likely to far outweigh any risks.

A Reminder on Maintaining Bone Health

Jane E. Brody : NY Times : October 31, 2011

Is fear, ignorance or procrastination putting you at risk of a devastating bone fracture?

Most of the news about osteoporosis concerns the side effects of current therapies and preventives. But it is important to put these effects in perspective — and to focus on treatment benefits and practical measures that can help to prevent costly and debilitating fractures in fragile bones.

Osteoporosis is both underdiagnosed and undertreated. Doctors say it is underdiagnosed because many who have it fail to get a bone density test, sometimes even after they suffer a fracture. The condition is undertreated because some people avoid drug therapy for fear of side effects, while others take their medications erratically or stop taking them altogether without consulting their doctors.

It is easy to understand the prevailing concern. People hear about drug side effects like osteonecrosis, or bone death, of the jaw (extremely rare and mostly in cancer patients) and unusual fractures of the thigh bone. They hear that supplements of bone-building calcium can increase the risk of heart attack or stroke.

Some 10 million Americans have osteoporosis, and 34 million more with low bone mass are at risk of developing it. It is a silent disease that typically first shows up as a low-trauma fracture of the hip, spine or wrist. Low-trauma does not mean no trauma; someone with healthy bones who falls from a standing height or less is unlikely to break a bone, according to Dr. Sundeep Khosla, president of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research.

While women are the far more frequent victims of osteoporosis and develop it at a younger age, men — especially those over 70 — are also at risk and even less likely than women to have the disease diagnosed and treated.

New Perspective on Treatment

When drugs called bisphosphonates were introduced to prevent and treat osteoporosis (Fosamax, now available as a generic called alendronate, was the first), overly enthusiastic doctors prescribed them for millions of postmenopausal women who were not at high risk of fracture. These were women whose bone density in the hip or spine measured below that of a healthy 35-year-old but still not near the level associated with osteoporosis.

I was one, and like many others, at age 60 I had what the World Health Organization has labeled osteopenia, not osteoporosis. Osteopenia is defined as a bone density “T-score” between minus 1 and minus 2.5, the lower number being the cutoff for osteoporosis.

Osteopenia is analogous to prediabetes or prehypertension, and as with these conditions, Dr. Khosla recommends that most cases of osteopenia are best treated with protective lifestyle measures, not drugs.

Dr. Khosla, a professor of medicine at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., suggested in an interview that before turning to drugs, people with osteopenia could try to prevent further bone loss with regular weight-bearing and strength-training exercise, adequate intake of calcium and vitamin D, not smoking and limiting alcohol consumption to one drink a day.

The exceptions — those most likely to benefit from drug treatment even if they do not yet have osteoporosis — include people who already have had a low-trauma fracture and those with a bone density level approaching osteoporosis who also have other risk factors, like early menopause, a family history of osteoporosis, the use of steroid drugs (prednisone and others that increase bone loss), extreme thinness, a digestive problem that limits calcium absorption or advanced age.

“Age is itself a major risk factor for fracture,” said Dr. Ethel Siris, director of the osteoporosis clinic at Columbia University Medical Center in New York. Even at the same bone density, a woman of 75 or older is more likely to experience a fall and fracture than a woman of 55.

Dr. Siris explained that with age, changes in the architecture of bones diminish their strength, which can be countered by bisphosphonates. Current thinking in the field, she said, is to place women at risk of fracture on a drug like Fosamax for five years and then perhaps take a one-year drug holiday. For two other bisphosphonates, Actonel and Boniva, she suggests a drug holiday of 6 to 12 months after seven years of treatment.

Benefit Versus Risk

On average, the bisphosphonates reduce the risk of a fragility fracture by 30 to 50 percent. By comparison, the risk of the most talked-about serious side effect — an atypical fracture of the femur, or thigh bone — is minuscule.

A recently published study examined the use of bisphosphonates among 12,777 Swedish women age 55 or older who suffered a fracture of the femur in 2008. Although those who had taken the drugs were 47 times as likely as those who had not to have experienced an atypical femur fracture, the actual number of these fractures was only 5 in 2,000 women who had used the drugs for five years.

Dr. Khosla estimated that the drugs would have prevented more than 100 osteoporotic fractures in these women, a benefit at least 20 times greater than the risk.

Furthermore, this unusual fracture can be prevented because it is preceded by a warning sign — bone changes that cause pain or discomfort in the thigh or groin that persists for weeks or months. If this occurs, Dr. Siris said, you should see your doctor without delay and get an X-ray.

If the X-ray is inconclusive, a bone scan or M.R.I. should follow. If an abnormality is found, Dr. Khosla said, the drug should be stopped and an orthopedist familiar with the problem should be consulted. If keeping weight off the leg does not result in healing, he said, a rod can be surgically inserted in the femur to prevent a fracture.

But Dr. Siris warned against assuming that any pain in the thigh is being caused by the drug. She said too many patients who are at high risk of an osteoporotic fracture stop the drug on their own when in fact the pain could result from sciatica or arthritis in the hip.

As for the risk from calcium supplements, the study that linked them to heart attacks and strokes did not consider how much calcium the women consumed.

Dr. Siris, among others, recommends 1,200 milligrams a day from diet alone or a combination of diet and a supplement. She noted that each serving of dairy (a cup of milk or yogurt or chunk of cheese) provides about 300 milligrams, and most people get another 200 or 300 from nondairy sources.

She said, “If too little calcium is consumed, parathyroid hormone will take calcium from the bones to maintain a normal blood level” of this essential mineral. Vitamin D — about 1,000 to 2,000 international units a day — is also important to assure adequate calcium absorption, especially for those “with bad bones,” she said.

Saving Your Bones: Hard Choices

Osteoporosis Drugs Prevent Fractures, but Patients Worry About Side Effects; Weighing the Risks

Melinda Beck : WSJ Article : September 14, 2009

Osteoporosis has haunted my family for generations, as it has many other families.

My great-grandmother was bent nearly horizontal from collapsed vertebrae. My grandmother lost a foot in height as her spine deteriorated, and broke her hip just pushing a grocery cart. I made her a new backbone out of papier-mâché when I was 4.

My mother did everything she could to avoid the family curse, but she also suffered painful collapsed vertebrae. All three women died, directly or indirectly, as a result of osteoporosis.

That was before the bone-building drugs called bisphosphonates became widely available in the mid-1990s. Thanks in part to them, the number of hip fractures has dropped significantly in the U.S. and Canada in recent years.

Osteoporosis remains a serious health problem for the 10 million Americans who have it and the 34 million who are at risk due to low bone mass; 80% of sufferers are women. It's estimated that one half of women and one-quarter of men over age 50 will suffer an osteoporosis-related fracture.

But reports of scary side effects from bisphosphonates—including Fosamax, Actonel and Boniva—are circulating on the Internet and in medical journals. Hundreds of lawsuits allege that the drugs cause a rare condition in which part of the jaw bone dies. The first case to be tried against Merck & Co.'s Fosamax ended in a hung jury last week in federal court in New York City. And some critics say the drugs—with sales of $8.3 billion a year in the U.S.—are being oversold to women who may never need them.

All that leaves women facing a difficult dilemma: Powerful osteoporosis drugs known to prevent future debilitating injuries are also suspected of increasing the risk for other terrible conditions. Balancing the risks and benefits is different for every woman, and depends on factors such as genetic history, diet and lifestyle. Figuring out how to proceed also requires having a very careful discussion with a qualified physician.

A good place to start is with your family tree. Having a parent with osteoporosis raises your own risk significantly. Caucasians, Asians and Hispanics also have higher rates of osteoporosis than African-Americans. So far, scientists have identified 15 related genes—but there isn't likely to be a predictive genetic test anytime soon.

That's because environmental factors also play a big role. The more bone you build up during the peak building years before age 30, the more reserves you'll have when net bone loss sets in. For women, that happens very rapidly after menopause when estrogen levels decline. Men lose bone far more slowly, although hormone-deprivation drugs for prostate cancer can also set them up for osteoporosis, as can a very strong hereditary load.

A diet rich in calcium (from dairy products and vegetables), plenty of exposure to vitamin D and weight-bearing exercise all help to build strong bones. Too little of those can weaken them, as can smoking, drinking alcohol, and a taking a variety of medications, including corticosteroids, anticonvulsants and antidepressants. Excessive dieting and exercising and being very thin—with a body-mass index of less than 20—can also leave your bones with little reserve. Being obese actually lowers your risk, though it can overstress your joints.

But some people can do everything right and still develop osteoporosis if they have a strong genetic predisposition.

A bone-mineral-density test can give you one indication of how strong your bones are. Women with several risk factors should have one at menopause; or at least at age 65. The most common such test, called a DEXA (for dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry) is quick and painless and measures the amount of bone in your hip, spine or wrist. Results, called T-scores, compare that density with an average peak at age 30.

A T-score of minus 2.5 or below indicates osteoporosis. A T-score between minus 1 and minus 2.4 is considered osteopenia—meaning low bone density but not full-blown osteoporosis.

You and your doctor can also assess your risk by using an online tool developed by the World Health Organization called FRAX, for Fracture Assessment Risk Tool. (See www.shef.ac.uk/FRAX.) It asks your sex, age, weight, height, hip-bone density and factors such as smoking, drinking, and parental hip fractures. It computes your chances of suffering a major bone fracture in the next 10 years.

What to do with that information is still somewhat controversial. "If you already have severe osteoporosis, you don't need a FRAX score to tell you you need treatment," says Bess Dawson-Hughes, director of the Bone Metabolism Lab at Tufts University, who has advised many of the drug makers. "Where we have struggled is what to do with that large group of healthy people who have low bone mass."

The National Osteoporosis Foundation's latest guidelines say that women who have a 3% risk of developing a hip fracture or 20% risk of other major fracture in the next 10 years are candidates for treatment, on cost-effectiveness grounds. In studies of older women with osteoporosis, Fosamax has been found to reduce the chance of hip and spine fractures as much as 50% . But it's less clear to what extent such drugs can prevent osteopenia from becoming osteoporosis.

Experts say that individual patients should never be treated based on T-scores or FRAX probabilities alone. Many other considerations apply.

Are You at Risk?

The more "yes" answers, the greater your risk for developing osteoporosis:

"You need to consider the unique characteristics of this lady in front of you," says Ethel Siris, director of the Toni Stabile Osteoporosis Center at Columbia Presbyterian Medical Center, who has also consulted for the drug makers. For example, a 50-year-old woman with osteopenia may not be a candidate for treatment based on her FRAX alone. But if she falls a lot and her mother suffered spinal fractures, which the FRAX doesn't ask about, it may make sense to treat her for a few years and see how her bone density does, Dr. Siris says. Meanwhile, a 70-year-old who has the same T-score probably started out with better bone density, but she has had 20 more years for her bone architecture to erode, so her bones are more fragile, even though they weigh the same.

The official guidelines also don't take into account potential side effects of the bisphosphonates, which are also highly individual. Gastrointestinal upsets are the most common; the oral medications aren't recommended for patients who can't sit upright for at least a half-hour because these drugs can irritate the esophagus. Gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD) can make such discomfort worse. A woman with severe GERD might fare better on Reclast, a once-a-year injection of bisphosphonate.

Some patients have also reported severe bone and muscle pain while taking bisphosphonates. The Food and Drug Administration alerted doctors last year that they might see this and consider discontinuing the drugs at least temporarily. Who is most affected and how long it lasts seems unpredictable. "I treat a gazillion patients and I see this rarely," says Dr. Siris. "When I do, we stop and re-evaluate."

Cases of osteonecrosis of the jaw (ONJ)—in which parts of bone become exposed during dental work and don't heal—are more serious but very rare. No one knows the exact incidence. Estimates range from 1 in 1,000 to 1 in 100,000 patients taking bisphosphonates for osteoporosis. (It's far more common in cancer patients on much higher doses.) Merck and other manufacturers say there is no evidence that the drugs cause ONJ at doses used for osteoporosis, but some dentists have become wary of doing invasive dental work on women taking bisphosphonates.

"We often advise patients who need extensive, invasive dental work to get that done first, then start the drugs and the issue disappears," says Ian Reid, a professor at the University of Auckland in New Zealand who has written on biosphosphonate safety.

A few doctors have reported unusual fractures of the thigh bone in women taking bisphosphonates for many years. One theory is that because the drugs inhibit the breakdown of old bone, they may be maintaining bone that is unusually brittle. Here too, the incidence seems extremely rare and the link remains unproven. But experts agree that it warrants further study—and that patients and doctors should investigate any unusual thigh pain which has preceded several of the fractures.

On balance, most experts say that women with confirmed osteoporosis face a much higher risk of fractures if they don't treat their condition than if they do. "These horrible cases are incredibly rare, whereas hip fractures are not rare in the aging population and they can kill you," says Dr. Siris. She notes that there are still many unknowns about drugs, including how long it is safe for women to stay on them. Many doctors are using them with patients only about five years at a time and then re-evaluating.

Other osteoporosis drugs on the market work differently and carry different risks. Evista (raloxifene) acts on estrogen receptors and can cut the risk of breast cancer as well as spinal fractures in some women, although it doesn't prevent hip fractures. Forteo (teriparatide) is a daily injection for women with severe osteoporosis, but has been linked with bone malignancies in rats. Last month an advisory panel recommended that the FDA approve denosumab, a biological agent that blocks the production of osteoclasts that break down bone. It would be a twice-yearly injection.

Estrogen-replacement therapy can also help women postpone the rapid loss of bone mass that occurs after menopause. It's no longer recommended for bone protection alone—in part because of the added risk of heart disease and breast cancer found in older women in the Women's Health Initiative studies. But the risk-benefit profile seems more favorable for younger women who want relief from menopausal symptoms like hot flashes. "If you hate your life without estrogen, you can go back on it and that's your bone-loss drug as well," says Dr. Siris.

Some clinics urge women to fight osteoporosis with lifestyle changes rather than pharmaceuticals. Many experts agree that sufficient calcium (at least 1,200 mg per day from food or supplements) and vitamin D (800 to 1,000 IUs per day) and weight-bearing exercise (at least 30 minutes, three times a week) are critical for building and maintaining strong bones, but they may not be sufficient for reversing serious bone loss once it's set in.

All camps agree that the very best way to strong bones is to build them well to begin with. Nearly 90% of bone mass in females is built by age 18, yet few adolescent girls are getting the recommended amounts of calcium and vitamin D.

The (Often Neglected) Basics for Keeping Bones Healthy

By Gina Kolata : NY Times Article : October 19, 2004

In surveys and focus groups, most Americans say they know what to do to protect themselves against osteoporosis, the disease of fragile bones that often occurs in the elderly: eat lots of calcium-rich foods or take a calcium supplement.

Many say they are doing just that, or plan to.

But this response worries osteoporosis researchers like Dr. Joan McGowan, chief of the musculoskeletal diseases branch at the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases.

Consuming calcium, she and others note, can at best make a small difference in osteoporosis risk, while other methods that can have a more substantial effect are often ignored.

Dr. McGowan is one of two scientific editors of the surgeon general's report on bone health that was released last week. The report has an ambitious goal: to educate doctors and the public so that they can put into practice what researchers know about preventing and detecting the bone disease.

The lack of this knowledge, Dr. McGowan said, often leads to bad practice.

For example, she said, doctors should routinely evaluate people over 50 who break a bone, for any reason, to see if they have osteoporosis. But such evaluations are seldom ordered.

Doctors should also make sure that older people get enough vitamin D, because deficiencies greatly increase fracture risk, Dr. McGowan said. But this, too, is rarely done.

Osteoporosis, the most common bone disease, is grimly serious, afflicting 10 million Americans over age 50 annually.

Each year, the report found, about 1.5 million Americans break bones because of osteoporosis, costing the health care system $18 billion. Often, the bone that is broken is the hip. And a hip fracture can set off a spiral leading to a nursing home and death: 20 percent of people who break a hip die within a year, the report said.

Osteoporosis can be prevented and treated with drugs that keep bones from breaking down - if people realize that they have it.

The report urges that doctors and patients pay attention to bones throughout life. Children and adolescents need a proper diet and exercise to stimulate bone growth. For adults, eating properly and staying active can maintain bone strength.

The report recommends that people over 50 who are at high risk for osteoporosis - women with a strong family history of the disease, for example - and anyone over 65 have a bone density test. Older people should also take simple measures to prevent falls, like removing small rugs from their homes.

But paying close attention to fractures is near the top of most experts' list of largely ignored medical interventions.

"When you see people over 50 who fall and break a wrist bone, you need to stop and take a look," said Dr. Richard H. Carmona, the surgeon general. "We need to take one step back and say, 'Why should that bone have broken from a simple fall?' "

That advice is not just for broken wrist bones, Dr. McGowan added.

"One of the ideas that people have is that you earned your fracture," she said. "You tripped, or you were ice skating with your granddaughter and you fell and broke your arm. Well, how many times did your granddaughter fall and not break an arm?"

Dr. McGowan said that a fracture was "really a sentinel event in an older person - any fracture."

"I don't care if you got it falling off a bike or even in a traffic accident," she continued.

Yet too often, she said, doctors do not send patients with broken bones to be evaluated to see why the bone broke in the first place.

The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons agrees.

In a position statement last year, it urged members to do more than just repair fractures in older people.

"There is a terrific information gap," said Dr. Laura Tosi, an orthopedic surgeon at George Washington University and a member of the academy's board. "Orthopods know how to put metal in and get people up and going, but if you don't prevent future fractures, people will end up disabled."

It is not just orthopedists who often miss opportunities. In a paper published last year in The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, Dr. Ethel Siris, director of the Toni Stabile Osteoporosis Center at New York-Presbyterian Hospital/Columbia University Medical Center in New York, and her colleagues reviewed the data and found it depressing.

"In virtually all the reports that have been published in the past few years, physicians who deal directly with the fracture event rarely take appropriate action," they wrote. "This includes radiologists who review X-rays that include the spine, orthopedic surgeons who treat acute fractures, physiatrists who oversee rehabilitation after the fracture, and primary care physicians to whom the patients return for overall care once the fracture has healed."

For example, in one study reviewed in the paper, of 934 women over age 60 who had routine chest X-rays, 132 had visible moderate to severe vertebral fractures. But only 17 of them had these fractures noted on their discharge statements.

Another underappreciated problem, osteoporosis experts say, is a lack of vitamin D, which bones need to absorb calcium and phosphorus. Vitamin D deficiencies greatly increase the risk of fractures. Yet a new national study by Dr. Michael Holick of Boston University, of about 1,500 postmenopausal women with osteoporosis, found that half had vitamin D levels below what is considered ideal.

Vitamin D is made in the skin in response to sun exposure, but many people do not get enough sunlight, Dr. Siris said, noting that there is a concern about skin cancer. "People today are sun-averse," she said. "And in the elderly, who don't go outdoors, this is a real issue."

She added that the deficiency was easily corrected by vitamin D supplements that cost as little as $3.40 for 100 pills.

Osteoporosis is a real problem, Dr. Siris said. "This is not something made up by the pharmaceutical industry."

But for people who are worried about ending their days bent over with the disease, or with a broken hip in a nursing home, Dr. Carmona has a message.

"You don't have to be a hunched over old lady or old man," he said. "If you pay attention to bone health."

Along the Spine, Women Buckle at Breaking Points

By Jane E. Brody : NY Times : June 27, 2011

An 80-year-old friend was lifting a corner of the mattress while making her bed when, as she put it, “I broke my back.”

In fact, she suffered a vertebral fracture — a compression, or crushing, of the front of a vertebra, one of the 33 bones that form the spinal column. This injury is very common, affecting a quarter of postmenopausal women and accounting for half of the 1.5 million fractures due to bone loss that occur each year in the United States.

By age 80, two in every five women have had one or more vertebral compression fractures. They often result in chronic back pain and impair the ability to function and enjoy life. They are one reason so many people shrink in height as they age.

Multiple vertebral fractures, found in 20 percent to 30 percent of cases, often result in a hunched posture, a condition called kyphosis that impairs breathing and compresses the abdomen, leading to a protruding stomach with limited capacity.

But while vertebral fractures are a telltale sign of bone loss among women over age 50 and men over age 60, most who suffer them are unaware of the problem and receive no treatment to prevent future fractures in vertebrae, hips or wrists, the bones most likely to break under minor stress when weakened.

Yet, if a vertebral fracture is diagnosed and properly treated, the risk of future fractures, including hip fractures, is reduced by half or more, studies have shown.

“Most vertebral fractures do not come to medical attention at the time of their occurrence,” Dr. Kristine E. Ensrud and Dr. John T. Schousboe wrote recently in The New England Journal of Medicine. One reason is that the pain may be minimal at first or, if more severe, attributed to a strain that subsides over a few weeks.

Indeed, patients or their physicians are made aware of these fractures in just one-fourth to one-third of the instances in which they are discovered on X-rays, according to the doctors.

“The patient may have had a chest or back X-ray for some other reason, perhaps to rule out pneumonia, but the focus is on why the test was ordered, and an incidental finding of a vertebral fracture is ignored,” Dr. Ensrud said in an interview. “Doctors need to be more aware of this problem, and maybe patients should ask to see the report.”

Dr. Ensrud, an internist and epidemiologist who researches osteoporosis at the University of Minnesota and the Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Minneapolis, noted that in a person with severe osteoporosis, a vertebral fracture can be caused by something as mundane as coughing, sneezing, turning over in bed or stepping out of a bathtub.

In patients whose bone loss is less advanced, a fracture may occur when lifting something heavy, tripping or falling out of a chair.

“A lot of the time, people don’t recall the incident,” Dr. Ensrud said. “They just report that their back has been bothering them.” Patients also may mistakenly assume that their chronic discomfort is a result of arthritis or a normal consequence of age, and never mention it to their doctors.

About one-third of the postmenopausal women found to have vertebral fractures do not have osteoporosis as defined by bone mineral density testing, according to Dr. Ensrud and Dr. Schousboe. Rather, test scores indicate that these women are suffering from a lesser form of bone loss called osteopenia.

Yet the occurrence of vertebral fractures means that the situation is worse than bone density testing would suggest. “The identification of a vertebral fracture indicates a diagnosis of osteoporosis,” Dr. Ensrud and Dr. Schousboe concluded in their article.

Asked if such women should receive bone-preserving medication, Dr. Ensrud said emphatically, “Yes!” One major study found that a vertebral fracture raises the risk of further vertebral fractures by five times in just one year.

A vertebral fracture can be seen on an ordinary X-ray of the spine. But there is a more practical approach involving much less radiation: a scan of the spine called a lateral DEXA, an acronym for dual energy X-ray absorptiometry, as part of a routine bone density exam.

The scan requires special computer software. Patients must ask whether a particular clinic or hospital is able to perform a lateral DEXA.

If a postmenopausal woman whose bone density measures in the osteopenic range (suggesting bone loss, but not yet full-blown osteoporosis) is found to have a vertebral fracture, her doctor may decide to prescribe medication that increases bone strength. Often the drug will be a bisphosphonate like alendronate (brand name Fosamax), which is now available in an inexpensive generic form.

Future fractures can often be prevented if a bisphosphonate is taken by someone found to have one or more vertebral fractures, even if these fractures cause no discomfort. There are many other bone-building options, too, including a once-a-year injection.

In addition, patients should consume adequate amounts of calcium and vitamin D, the critical nutrients for strong bones: a total of 1,200 milligrams of calcium daily from food and supplements, and 1,000 international units daily of vitamin D.

Initially, a painful vertebral fracture may be treated with a short period of bed rest and pain medication like a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug, narcotic, pain patch or an injection or nasal spray of calcitonin. But if too much time is spent in bed, the resulting weakness can increase the risk of further fractures.

Whatever is done, or not done, to treat the injury, the pain of a vertebral fracture usually subsides over the course of several weeks.

Dr. Ensrud and Dr. Schousboe cautioned in their article against rushing into two invasive procedures that have become increasingly common in this country: vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty. During these procedures, a kind of cement is injected into the compressed vertebra to stabilize it.

The operations are performed by interventional radiologists who, naturally, endorse them enthusiastically. However, two scientifically conducted studies of vertebroplasty using sham procedures as a control found no benefit with respect to pain, disability or quality of life.

Nor are these procedures completely free of risk. Although rarely, they can sometimes injure nerves or cause pulmonary embolisms. They also may result in fractures of adjacent vertebrae by increasing the mechanical stress on them.

Exercises to improve posture, strengthen back muscles and enhance mobility are less costly and likely to be more effective in the long run, the doctors wrote.

How Well Will Your Bones Hold Up?

By Tara Parker-Pope : NY Times Article : May 13, 2008

Are the bones of America about to crumble?

Given the money Americans spend on bone-protecting drugs, you might think so. Spending on these drugs has surged to $5 billion annually, a 50 percent increase compared with five years ago.

While osteoporosis and hip fractures are major health concerns for some people, the challenge is finding out who is at risk and who is not. Most of us have normal aging bones that are not going to break — about 85 percent of women will never fracture a hip.

But an estimated 329,000 hip fractures occur annually in the United States. Hip fractures often lead to declining health. Women with such fractures face a 15 to 20 percent increased risk of dying the year after the break. Although men are also at risk for fracture, fragile bones are more common in women.

Our bodies build bone at a frenzied pace in childhood, but that slows as we get older. After about age 30, we lose bone faster than we can replace it, and bone density starts to wane. Most people have enough bone to start with, so the bone loss of aging is not a big problem. But for some, the decline in density is rapid, as their bones become porous and fracture risk increases.

Most doctors use bone density scans to identify women who are at risk for fractures. Based on the results, a woman may receive a diagnosis of osteoporosis. However, many women receive diagnoses of osteopenia — a scary-sounding term to describe early bone loss that often occurs with normal aging.

Despite the medical community’s heavy reliance on bone density scans, there is growing evidence that bone density is not the most reliable indicator of bone health. A poor score on a scan doesn’t mean you’re in trouble, and a normal score doesn’t mean you’re not at risk. Most people who suffer hip fractures have normal bone density, but their bones have weakened in ways not detected by bone scans.

“We’ve convinced people that you’ve got to have a certain bone density or you’ll have fractures and horrible things will happen to you,” said Dr. Susan Love, clinical professor of surgery at the David Geffen School of Medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles. “But bone density is only one aspect of bone health. It just happens to be the one we can measure.”

So how does a woman know if her bones are at risk? The answers to a few simple questions can give you a better sense of the state of bone health.

Have you ever broken a bone as an adult? Under most circumstances, breaking a bone after age 20 suggests that bones are weaker than normal, even if a bone density test does not signal a problem. “If you have broken a wrist or ankle or hip, that’s a no-brainer,” said Dr. John Robbins, a professor at the University of California, Davis, School of Medicine. “You don’t need a calculator or a bone scan to tell you something is wrong. You’ve failed the ultimate test.”

Did your mother break any of her bones? A New England Journal of Medicine study showed that women whose mothers suffered hip fractures before age 80 were nearly three times as likely to suffer a similar fracture.

Does a vision problem make you clumsy? A major New Zealand study of hip fracture risk, published in The American Journal of Epidemiology, found a strong link between sight problems and fracture risk. Poor vision in both eyes nearly triples fracture risk, while depth perception problems increased risk sixfold.

How far will you fall? A New England Journal of Medicine study showed that tall women are at high risk for hip fracture. It could be because of differences in the architecture of the hip in tall, as opposed to shorter, women. However, the increased risk could be related to the fact that tall women just have farther to fall.

Have you packed on pounds since your 20s? Here’s one case where weight loss is not good. The more weight a woman gains after age 25, the lower her risk of fracture. Women over 50 who weigh less than they did at 25 face a three times higher risk for fracture.

Can you get out of a chair? Women who can’t get out of a chair without using their arms have twice the fracture risk of those who can stand up effortlessly.

The more risk factors you have, the higher your fracture risk. If you also have low bone density, your risk is even higher. According to a 1995 New England Journal of Medicine study of nearly 10,000 women over 65, only 6 percent had multiple risk factors. Those women, however, accounted for about two-thirds of the fractures that occurred during the study.

Drugs to Build Bones May Weaken Them

By Tara Parker-Pope : NY Times Article : July 15, 2008

New questions have emerged about whether long-term use of bone-building drugs for osteoporosis may actually lead to weaker bones in a small number of people who use them.

The concern rises mainly from a series of case reports showing a rare type of leg fracture that shears straight across the upper thighbone after little or no trauma. Fractures in this sturdy part of the bone typically result from car accidents, or in the elderly and frail. But the case reports show the unusual fracture pattern in people who have used bone-building drugs called bisphosphonates for five years or more.

Some patients have reported that after weeks or months of unexplained aching, their thighbones simply snapped while they were walking or standing.

“Many of these women will tell you they thought the bone broke before they hit the ground,” said Dr. Dean G. Lorich, associate director of orthopedic trauma surgery at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell and the Hospital for Special Surgery. Dr. Lorich and his colleagues published a study in The Journal of Orthopaedic Trauma last month reporting on 20 patients with the fracture. Nineteen had been using the bone drug Fosamax for an average of 6.9 years.

Last year, The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery published a Singapore report of 13 women with low-trauma fractures, including 9 who had been on long-term Fosamax therapy.

The doctors emphasize that the problem appears to be rare for a class of drug that clearly prevents fractures and has been life-saving for women with severe osteoporosis. Every year, American adults suffer 300,000 hip fractures.

Merck, which makes Fosamax, says it will study whether the unusual fracture pattern is really more common in bone-drug users. Arthur Santora, Merck’s executive director for clinical research, noted that the fracture accounted for only about 5 or 6 percent of all broken hips, while drugs like Fosamax reduced the risk for the other 95 percent.

The fracture pattern did not emerge in placebo-controlled studies of bone drugs. But those studies have lasted only three to five years, although follow-up studies of the drug users have lasted longer. Now that the fracture pattern has been identified, researchers expect more doctors to publish reports.

“I have several similar patients myself,” said Dr. Susan M. Ott, associate professor of medicine at the University of Washington. “Prior to these recent articles, there were a few cases here and a few cases there, but they are kind of starting to add up.”

Bones are in a constant state of remodeling — dissolving microscopic bits of old bone, a process called resorption, and rebuilding new bone. After age 30 or so, a woman’s bones start to dissolve faster than they can be rebuilt, and after menopause she may develop thin, brittle bones that are easily broken. Bisphosphonates, including Fosamax, Procter & Gamble’s Actonel and GlaxoSmithKline’s Boniva, slow this process.

But some experts are concerned that microscopic bone cracks that result from normal wear and tear are not repaired when the bone remodeling process is suppressed. A 2001 study of beagles taking high doses of bisphosphonates found an accumulation of microscopic damage, though there was no evidence that their bones were weaker.

Last September, the medical journal Bone reported on a study of 66 women, financed by Eli Lilly, that showed an association between Fosamax use and an accumulation of microdamage in bones.

In January 2006, the medical journal Geriatrics published an unusual autobiographical case report. Dr. Jennifer Schneider, a 59-year-old physician from Tucson, wrote that she was riding a New York City subway when the train lurched. “I felt a crack and I fell,” she recalled in an interview. “I knew I’d fractured my femur.”

Dr. Schneider, who had been taking Fosamax for seven years, said she had had pain in her thigh, but X-rays and scans had not found a problem.

In recent years, another rare side effect has been associated with bone drugs: osteonecrosis of the jaw, in which a patient’s jawbone rots and dies. Most victims are cancer patients taking a potent intravenous form of the drug, but a small number of cases from ordinary users have been reported.

Notably, studies suggest there is little extra benefit in taking the bone drugs more than five years. Dr. Lorich says that doctors should monitor the bone metabolism of long-term users and that some patients may want to consider taking time off the drugs. When fractures do occur, surgeons need to be alerted about long-term drug use, because the fracture may require more aggressive treatment and be slower to heal.

Dr. Ott says the focus should be on using bone drugs only in patients with a fracture risk of at least 3 percent over the next 10 years. (An online fracture risk tool is at www.shef.ac.uk/FRAX.)

“Too many of these people are not getting adequate treatment that definitely is beneficial,” Dr. Ott said. “My major caution is that the bisphosphonates should not be used in people who don’t have a high risk of fracture.”

Cola Raises Women's Osteoporosis Risk

Caffeine might be the culprit, experts say

By Steven Reinberg : HealthDay Reporter : Oct 6, 2006

"Among women, cola beverages were associated with lower bone mineral density," said lead researcher Katherine Tucker, director of the Epidemiology and Dietary Assessment Program at the Jean Mayer USDA Human Nutrition Research Center on Aging at Tufts University.

There was a pretty clear dose-response, Tucker added. "Women who drink cola daily had lower bone mineral density than those who drink it only once a week," she said. "If you are worried about osteoporosis, it is probably a good idea to switch to another beverage or to limit your cola to occasional use."

The report was published in the October issue of the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition.

About 55 percent of Americans, mostly women, are at risk for developing osteoporosis, according to the National Osteoporosis Foundation.

In the study, Tucker's team collected data on more than 2,500 participants in the Framingham Osteoporosis Study, averaging just below 60 years of age. The researchers looked at bone mineral density at three different hip sites, as well as the spine.

They found that in women, drinking cola was associated with lower bone mineral density at all three hip sites, regardless of age, menopause, total calcium and vitamin D intake, or smoking or drinking alcohol. Women reported drinking an average of five carbonated drinks a week, four of which were cola.

Bone density among women who drank cola daily was almost 4 percent less, compared with women who didn't drink cola, Tucker said. "This is quite significant when you are talking about the density of the skeleton," she said.

Cola intake was not associated with lower bone mineral density in men. The findings were similar for diet cola, but weaker for decaffeinated cola, the researchers reported.

The reason for cola's effect on bone density may have to do with caffeine, Tucker said. "Caffeine is known to be associated with the risk of lower bone mineral density," she said. "But we found the same thing with decaffeinated colas."

Another explanation may have to do with phosphoric acid in cola, which can cause leeching of calcium from bones to help neutralize the acid, Tucker said.

One expert agrees that women should reduce the amount of cola they drink.

"I would expect this finding," said Dr. Mone Zaidi, director of the Mount Sinai Bone Program at Mount Sinai School of Medicine, in New York City. "It's probably a caffeine-related problem."

Women should limit their caffeine intake, Zaidi said. "Caffeine interferes with calcium absorption, which results in less bone formation," he said.

This can be a problem for younger women who never develop peak bone density, Zaidi noted. "Younger women who have a lot of coke will not form bone to an extent their peers would; so, years later, in menopause, they are going to be disadvantaged," he said.

Men, Too, Should Worry About Their Bone Health

By Jacob Goldstein : Wall Street Journal Article : December 4, 2007

Hip and spine fractures are among the most common disabling injuries of the elderly. But because they are more common in women, strategies to prevent them are rarely directed at men.

"We've figured out what to do with women, but men have been largely ignored," says Angela Shepherd of the University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston. That's starting to change as more men live longer and find their lives changed for the worse after breaking a bone.

SCREENING SYSTEM

To identify men at risk for osteoporosis, a new tool assigns points in 3 categories:

Weight: Points start accumulating for men who weigh 175 pounds or less.

Age: The system begins assigning points at age 56.

COPD: Risk is greater with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Dr. Shepherd recently published a system doctors can use to identify men at risk of osteoporosis, a weakening of the bones that raises the risk of fractures. She was drawn to the field after an 89-year-old patient fell and broke his hip while dancing with his wife on New Year's Eve. "I don't think he ever danced again after that," Dr. Shepherd says. "He had to use a walker."

One in four men over 50 will have an osteoporosis-related fracture during his lifetime (for women the figure is one in two), according to the National Institutes of Health. The National Osteoporosis Foundation plans to release guidelines for bone health in men next year, according to Ethel Siris, president of the foundation and director of an osteoporosis center at Columbia University Medical Center.

Even without the guidelines, there are certain clear risk factors for men to be aware of, as well as steps they can take throughout life to keep bones healthy. Unlike women, whose risk of osteoporosis increases dramatically after menopause, men's risk increases slowly and typically doesn't become significant until later in life.

Dr. Shepherd's system, published in the Annals of Family Medicine, uses three variables: age, weight (lighter men are at higher risk) and a history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, which mainly affects smokers. Smoking and excessive drinking both increase the risk of osteoporosis.

Certain drugs can raise the risk dramatically. Hormone-blocking drugs used to treat prostate cancer, such as Lupron, can leave men with weaker bones, as can long-term steroid treatment for diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis and asthma.

Men who believe they may be at high risk can ask their doctor if they should undergo a bone mineral density test to diagnose osteoporosis. In severe cases, prescription osteoporosis drugs may be appropriate. But there are things all men can do to lower their risk of developing osteoporosis and breaking bones in old age.

Getting enough calcium and vitamin D helps. And exercise during childhood and adolescence, while the skeleton is still growing, builds bone. That's important because it helps raise the so-called peak bone mass reached during young adulthood, before the long-term decline in bone mass begins. "The less you start with, the less you're going to end up with when you're really at the age when osteoporosis risk is very important," says Eric Orwoll of Oregon Health & Science University, who is conducting a long-term study of osteoporosis in men.

Staying fit into old age is also important; it means stronger muscles and better coordination and balance, all of which help avoid falls, a key trigger for fractures in the elderly.

There is some evidence that the type of exercise -- weight-bearing, versus non-weight-bearing -- can make a difference for bones. For example, some research suggests competitive cyclists, who spend hours a week on their bicycles but little time running or jumping, may tend to have weaker bones than runners. Josh Johnson, who is 31 and describes himself as an "elite-level amateur" cyclist, recently participated in one such study, and learned that he's at risk for developing osteoporosis later in life.

"It definitely opened my eyes," he says. "I bought a jump rope and I used it for a little while, but I honestly haven't stayed real faithful to it."

Some experts nevertheless say that the more important point is simply to exercise. "I have not been convinced that the tiny increase in bone density [from weight-bearing exercise] is really that critical," Dr. Siris says. "If my patients say, 'I don't enjoy weight-bearing exercise, should I swim?' I say, 'Yes.' "

As Bones Age, Who’s at Risk for Fracture?

By Jane E. Brody : NY Times Article : December 29, 2009

For the millions of Americans with bones that are thinning as they age, this question arises: Who should be treated with bone-enhancing drugs?

Until recently, many doctors and drug companies that make these medications were saying almost everyone — especially older white women, who are at highest risk of one day suffering an osteoporotic fracture.

These low-trauma fractures are debilitating and costly, adding more than $17 billion a year to the national health care bill. Among elderly people who fracture a hip, 10 percent to 20 percent die within six months; many more spend the rest of their lives in nursing homes or needing full-time home care.

The National Osteoporosis Foundation reports that “about one out of every two Caucasian women will experience an osteoporosis-related fracture at some point in her lifetime, as will approximately one in five men.”

“Although osteoporosis is less frequent in African-Americans,” the foundation continues, “those with osteoporosis have the same elevated fracture risk as Caucasians.”

But the drugs currently available to enhance bone density are far from perfect. They are expensive, they can have side effects, and they are only about 50 percent effective at preventing fractures.

Before any treatment, possible risks should be weighed against known benefits.

If you have osteoporosis, defined as a T score — the standard measure of bone density — of minus 2.5 or lower, or you have already had an osteoporotic fracture of the forearm, hip, shoulder or spine, the answer is clear: treat. For you, experts say, the benefits of treatment are expected to far outweigh the risks.

But what about the much greater number of women and men whose bones are not as strong as they were at age 30 but who have not yet become osteoporotic — with T scores in the hip or spine of minus 1 to minus 2.5? They are said to have osteopenia, which may or may not eventually lead to osteoporosis. Who among them would most likely benefit from treatment?

A Tool to Help

To help answer this question, the World Health Organization has devised a controversial tool called FRAX, an online risk calculator to help doctors and patients analyze the likelihood of future osteoporotic fractures and determine whether drug therapy might prevent them. (The calculator is at www.shef.ac.uk/FRAX/index.htm.)

The controversy stems largely from the fact that not every possible contributor to fracture risk has been factored into the FRAX formula. In its latest “Clinician’s Guide to Prevention and Treatment of Osteoporosis,” the National Osteoporosis Foundation provides a full list of the lifestyle factors, conditions, diseases and medications that contribute to the risk of osteoporosis and fractures.

Especially missing from FRAX are weight-bearing exercise, which has a certain benefit, and a diet that builds bone, which is itself subject to some debate. But the W.H.O. formula includes most of the major players, called clinical risk factors, that affect bone health. And if FRAX is used properly, it can result in far wiser treatment decisions than might otherwise be made.

The formula provides a means of estimating someone’s probability of suffering a hip fracture or major osteoporotic fracture within 10 years, providing numbers that doctors and patients can understand. The risk factors it considers are age, gender, weight and height, a previous fracture, a parent with a hip fracture, current smoking, treatment with corticosteroids, alcohol consumption, rheumatoid arthritis and secondary osteoporosis due to a deficiency of vitamin D or excess of parathyroid hormone.

The formula can be applied to men and women across categories of race and ethnicity. In addition, it can be used without knowing a person’s bone density score, although having this test result can enhance the accuracy of the prediction.

“If, using FRAX, someone’s fracture risk is really low, a bone mineral density test probably wouldn’t change the risk very much,” Dr. Susan M. Ott, a bone specialist affiliated with the University of Washington in Seattle, said in an interview. “And if the risk using FRAX is really high, you don’t need the test; you need treatment.

“But if your FRAX risk is in between, getting a bone mineral density test can help you decide whether you need treatment.”

In the journal Osteoporosis International, Dr. Ethel Siris of NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital/Columbia University Medical Center notes that although people with osteopenia have a low fracture risk, many more fall into this midrange of bone density and “total fractures exceed those occurring in persons with osteoporosis.” Dr. Siris says FRAX helps identify “those in the low bone mineral density range who have the highest risk of fracture.”

Sample Calculations

In Clinical Correlations, an internal medicine blog of New York University, Dr. Judith Brenner demonstrated the power of the FRAX tool. Dr. Brenner calculated the risk for a 60-year-old white woman who is 5 feet and 110 pounds, with no family or personal history of fracture and no history of smoking or using steroids. Using FRAX, the risk of a hip fracture within 10 years for this woman is 1.5 percent.

If the same woman instead weighed 200 pounds, her risk would drop to 0.5 percent (more on the reasons below). But if the 110-pound woman had a parent who suffered a hip fracture, her risk would rise to 1.9 percent. Add smoking, and the risk goes to about 2.9 percent. Add steroids, and the risk rises to 5.9 percent. Add daily consumption of two or more alcoholic drinks, and the risk becomes 9 percent.

Instead of 60, say the woman is 80, slender and with no family or personal history of fractures, smoking or steroid use. Dr. Brenner calculated her risk of fracturing a hip in 10 years as 10 percent and of having any major osteoporotic fracture at 35 percent.

Considering the cost and effectiveness of established treatments, Dr. Brenner wrote, in deciding to treat, “the magic number is a 3 percent risk of hip fracture in 10 years or 20 percent risk of any other major osteoporotic fracture.”

When it comes to bone health, it pays to be heavier. Dr. Ott says that model-thin women are at significantly greater risk of breaking a bone. Extra body weight places more stress on bones, which stimulates them to become stronger. Also, body fat produces estrogen, which helps foster bone strength, especially in postmenopausal women.

But even for slender people, regular weight-bearing exercise is an enormous benefit to bones. “Walk, hike, dance — anything that’s weight-bearing can help protect the hips and spine,” Dr. Ott said.

A bone-healthy diet for women over 50 would provide about 1,200 milligrams of calcium and 1,000 international units of vitamin D daily. For those who take omega-3 fatty acids, Dr. Ott recommended using flaxseed oil rather than fish oil; the latter contains unknown amounts of vitamin A, which in excess can be detrimental to bones.

Definition:

Osteoporosis is a condition of decreased bone mass. This leads to fragile bones which are at an increased risk for fractures. In fact, it will take much less stress to an osteoporotic bone to cause it to fracture. The term "porosis" means spongy, which describes the appearance of osteoporosis bones when they are broken in half and the inside is examined. Normal bone marrow has small holes within it, but a bone with osteoporosis will have much larger holes. The pictures below show a bone with osteoporosis with large spongy holes, and a normal bone with normal small passageways. In severe osteoporosis, this can be exaggerated much more than shown below.

Diagnosis:

There is no method of determining the actual structure of bones without actually removing a piece during a biopsy (which is not practical or necessary). Instead, the diagnosis of osteoporosis is based on special x-ray methods called densitometry. Densitometry will give accurate and precise measurements of the amount of bone (not their actual quality). This measurement is termed "bone mineral density" or BMD.

The World Health Organization "WHO" has established criteria for making the diagnosis of osteoporosis, as well as determining levels which predict higher chances of fractures. These criteria are based on comparing bone mineral density (BMD) in a particular patient with those of a 25 year old female. BMD values which fall well below the average for the 25 year old female (stated statistically as 2.5 standard deviations below the average) are diagnosed as "osteoporotic". If a patient has a BMD value less than the normal 25 year old female, but not 2.5 standard deviations below the average, the bone is said to be "osteopenic" (osteopenic means decreased bone mineral density, but not as sever as osteoporosis). Interestingly, although these criteria are widelyused, they were devised in a Caucasian female so there will be some differences when these levels are applied to non Caucasian females or to males in general. Despite this flaw, measurement of BMD is used daily and has proven to be very helpful in all groups. Some men will be subject to increased fracture rates when they have significantly less BMD than the predicted fracture level for women. In other words, some men will be at increased risk for fracture even when they have osteopenia.

Osteoporosis is different from most other diseases or common illnesses in that there is no one single cause. The overall health of a person's bones is a function of many things ranging from how well the bones were formed as a youth, to the level of exercise the bones have seen over the years. During the first 20 years of life, the formation of bone is the most important factor, but after that point it is the prevention of bone loss which becomes most important. Anything which leads to decreased formation of bone early in life, or loss of bone structure later in life will lead to osteoporosis and fragile bones which are subject to fracture.

Daily calcium needs at different ages

Age

Amount of Daily Calcium

Infants

Birth to 6 months

400mg

Six months to 1 year

600mg

Children/Young Adults

One to 10 years

800 - 1,200 mg

11 to 24 years

1,200 - 1,500 mg

Adult Women

Pregnant or Lactating

1,200 - 1,500 mg

25 to 49 years (premenopausal)

1,000 mg

50 to 64 years (postmenopausal taking estrogen or similar hormone)

1,000 mg

50 to 64 years (postmenopausal not taking

estrogen or similar hormone)

1,500 mg

Over 65 years old

1,500 mg

Adult Men

25 to 64 years old

1,000 mg

Over 65 years old

1,500 mg

The American College of Physicians has issued a clinical practice guideline on screening men for osteoporosis. The guideline appears in the current Annals of Internal Medicine.

- Periodic assessments for osteoporotic fracture risk should start in men before age 65.

- Factors that increase risk include age >70, body mass index <25, recent weight loss >10%, physical inactivity, corticosteroid use, androgen-deprivation therapy, and previous fragility fracture.

- Men at increased risk should undergo screening with dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry.

Thinking Twice About Calcium Supplements

By Jane E. Brody : NY Times : April 8, 2013

Americans seem to think that every health problem can be solved with a pill. And certainly many are, especially infectious diseases that succumb to antibiotics, antifungals and, increasingly, antivirals.

But that leaves a medical dictionary full of ailments that continue to plague people despite the best efforts of Big Pharma. Most are chronic health problems related to how Americans live, especially what we eat and drink, and don’t eat and drink, and how we move or don’t move. In our aging society, these ailments have pushed the annual cost of medical care into the trillions of dollars and threaten to break Medicare.

Osteoporosis is one of these increasingly prevalent and costly conditions. Although there are drugs to stanch the loss of bone and the debilitating fractures that often result, the remedies are costly, difficult to administer and sometimes have side effects that can be worse than the disease they are meant to counter.

This makes prevention the preferred and more cost-effective option. But efforts to prevent bone disease have focused on a pill, namely supplements of calcium, the mineral responsible for creating bone in youth that must be maintained throughout adult life, which now routinely extends to the 80s and 90s.

But as with many other pills once regarded as innocuous, the safety and efficacy of calcium supplements in preventing bone loss is being called into question.

In February, the United States Preventive Services Task Force recommended that postmenopausal women refrain from taking supplemental calcium and vitamin D. After reviewing more than 135 studies, the task force said there was little evidence that these supplements prevent fractures in healthy women.

Moreover, several studies have linked calcium supplements to an increased risk of heart attacks and death from cardiovascular disease. Others have found no effect, depending on the population studied and when calcium supplementation was begun.

The resulting controversy has left countless people, especially postmenopausal women, wondering whether they should be taking calcium. Given the conditional evidence currently available, the answer is not likely to be greeted enthusiastically by anyone other than dairy farmers, who supply the foods and drinks that are the country’s richest dietary sources of calcium.

The one indisputable fact is that the safest and probably the most effective source of calcium for strong bones and overall health is diet, not supplements. But few American adults, and a decreasing proportion of children and teenagers, consume enough dairy foods to get the recommended intakes of this essential mineral.

Milk consumption has taken a steady nose-dive in the last four decades, largely supplanted by sugared soft drinks that are now under fire as major contributors to obesity and Type 2 diabetes. Beyond age 20, when bone loss can begin to overtake bone formation, the typical man and woman in this country consumes less than one cup of milk a day. Likewise for teenage girls, who should be striving to maximize bone formation so that there is more in reserve when bone loss begins.

Yogurt, which ounce for ounce is an even better source of calcium than fluid milk, has achieved unprecedented popularity in recent years, but few consume it more than once a day, which doesn’t come close to meeting dietary needs. Frozen yogurt, which threatens to supplant ice cream as the nation’s most popular frozen dessert, has about half the amount of calcium as regular yogurt and only slightly more than ice cream. Both are far more caloric than nonfat milk.