- RETIREMENT ANNOUNCEMENT

- HOME PAGE

- "MYCHART" the new patient portal

- BELMONT MEDICAL ASSOCIATES

- MOUNT AUBURN HOSPITAL

- EMERGENCIES

- PRACTICE PHILOSOPHY

- MY RESUME

- TELEMEDICINE CONSULTATION

- CONTACT ME

- LAB RESULTS

- ePRESCRIPTIONS

- eREFERRALS

- RECORD RELEASE

- MEDICAL SCRIBE

- PHYSICIAN ASSISTANT (PA)

- Medicare Annual Wellness Visit

- Case management/Social work

- Quality Care Measures

- Emergency closing notice

- FEEDBACK

- Talking to your doctor

- Choosing..... and losing a doctor

- INDEX A - Z

- ALLERGIC REACTIONS

- Alternative Medicine

- Alzheimer's Disease

- Bladder Problems

- Blood disorders

- Cancer Concerns

- GENETIC TESTING FOR HEREDITARY CANCER

- Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

- Controversial Concerns

- CPR : Learn and save a life

- CRP : Inflammatory marker

- Diabetes Management

- Dizziness, Vertigo,Tinnitus and Hearing Loss

- EXERCISE

- FEMALE HEALTH

-

GASTROINTESTINAL topics

- Appendicitis

- BRAT diet

- Celiac Disease or Sprue

- Crohn's Disease

- Gastroenterologists for Colon Cancer Screening

- Colonoscopy PREP

- Constipation

- Gluten sensitivity, but not celiac disease

- Heartburn and GERD

- Hemorrhoids and Anal fissure

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- NASH : Non Alcoholic Steato Hepatitis

- FEET PROBLEMS

- HEART RELATED topics

-

INFECTIOUS DISEASES

- Antibiotic Resistance

- Cat bites >

- Clostridia difficile infection - the "antibiotic associated germ"

- CORONA VIRUS

- Dengue Fever and Chikungunya Fever

- Food borne illnesses

- Shingles Vaccine

- Hepatitis B

- Hepatitis C

- Herpes

- Influenza

- Helicobacter pylori - the "ulcer germ"

- HIV Screening

- Lyme and other tick borne diseases

- Measles

- Meningitis

- MRSA (Staph infection)

- Norovirus

- Sexually Transmitted Diseases

- Shingles (Herpes Zoster)

- Sinusitis

- West Nile Virus

- Whooping Cough (Pertussis)

- Zika virus and pregnancy

- INSURANCE related topics

- KIDNEY STONES

- LEG CRAMPS

- LIBRARY for patients

- LIFE DECISIONS

- MALE HEALTH

- Medication/Drug side effects

- MEDICAL MARIJUANA

- MENTAL HEALTH

- Miscellaneous Articles

-

NUTRITION - EXERCISE - WEIGHT

- Cholesterol : New guidelines for treatment

- Advice to lower your cholesterol

- Cholesterol : Control

- Cholesterol : Raising your HDL Level

- Exercise

- Food : Making Smart Choices

- Food : Making Poor Choices

- Food : Grape Fruit and Drug Interaction

- Food : Vitamins, Minerals and Supplements

- Omega 3 fatty acids

- Vitamin B12 deficiency

- Vitamin D

- Weight Loss

- ORTHOPEDICS

- PAIN

- PATIENTS' RIGHTS

- SKIN

- SLEEP

- SMOKING

- STROKE

- THYROID

- SUBSTANCE ABUSE

- Travel and Vaccination

- TREMOR

- Warfarin Anticoagulation

- OTHER STUFF FOLLOWS

- Fact or Opinion?

- Hippocratic Oath

- FREE ADVICE.......for what its worth!

- LAUGHTER.....is the best medicine

- Physicians Pet Peeves

- PHOTO ALBUM - its not all work!

- Cape Town, South Africa

- Tribute page

- The 100 Club

- Free Wi-Fi

Case of the Daily Headache

That Chronic Head Pain Is Still a Mystery, But Habits Spur Onset

By Melinda Beck : WSJ : March 22, 2011

It's 4 p.m. You've been squinting at the computer all day. The phone won't stop ringing and ... here it is again ... that tightness that wraps around your head and s-q-u-e-e-z-e-s.

Tension headaches are the most common kind of headache, affecting about 40% of people in a given year. Yet they're also the most neglected by medical science and the least understood.

As legions of bleary office workers can attest, tension headaches are one of the most common human afflictions. Melinda Beck explains why chronic tension headaches are also among the most difficult to diagnose and treat.

That's in part because headache experts seldom see them. "In 20 years of practice, I can count on two hands the number of people I've seen with tension-type headaches," says David Dodick, a neurologist with the Mayo Clinic in Phoenix.

Most sufferers just tough them out or treat them with over-the-counter pain killers, which are generally effective. But neurologists warn that taking such pain relievers more than 10 days a month can cause what's known as rebound or medication-overuse headaches, which have the same dull, aching pain as tension headaches themselves.

"They give you temporary relief but they render you vulnerable to another attack," says Dr. Dodick, who is president of the American Headache Society, a professional group of headache experts.

Exactly how and why tension headaches occur is a mystery. Much more is known about migraines, which affect only 12% of the population, but are far more severe and tend to be pulsating and one-sided.

Experts used to believe that tension headaches were caused mainly by muscle tension, especially in the neck, back and shoulders. But studies using electronic sensors to measure muscle contractions found no consistent correlation between headaches, muscle tension or tenderness around the head. In fact, some sufferers had more muscle tension on headache-free days.

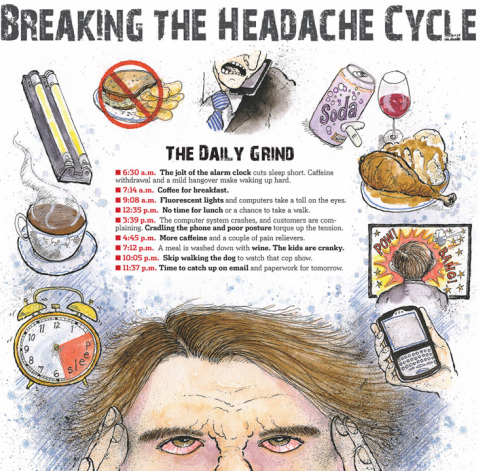

The Daily Grind

Another theory held that the tension was emotional or psychological—a physical manifestation of anxiety and stress. But there isn't a clear correlation there either. Some people under enormous stress never get headaches, and some people get them even at times of little stress.

"It's no longer clear to anybody that anything is tense," says Richard Lipton, vice chairman of neurology at Albert Einstein School of Medicine in the Bronx, N.Y., who says that realization was what prompted the International Headache Society, which officially classifies headache disorders, to adopt the term "tension-type headaches" in 1988.

Now many headache experts believe that people who get tension-type headaches have a dysfunction in the pain-perceiving areas of the brain that make them overly sensitive to stimulation at times. This so-called central sensitization is also thought to be the same mechanism involved in fibromyalgia, a mysterious, widespread pain disorder.

To be sure, tension headaches often involve sore, contracted muscles—but experts now think the pain perception starts in the brain and is referred out to those areas, rather than vice versa. Similarly, under this theory, stress doesn't cause the headache, but it does amplify the pain.

Tension headaches often go hand-in-hand with depression, although it's not clear which comes first. "People who are depressed have increased rates of headaches, and people who have frequent headaches often become depressed," Dr. Lipton notes.

A class of older antidepressants called tricyclics, such as amitriptyline (Elavil) or imipramine (Tofranil), are effective at staving off chronic tension-type headaches in many people who have not found relief with over-the-counter medications. Experts think the drugs' pain-relieving properties prevent the headaches; the dosage is usually far lower than would be used for depression alone. Tricyclics don't cause rebound headaches like other pain killers, but side effects can include drowsiness, dizziness and low blood pressure.

"We know these drugs work on pain receptors, but we still aren't clear on the exact mechanism, even though they've been available for 50 years," says Merle Diamond, associate director of the Diamond Headache Center in Chicago.

Anti-seizure drugs, muscle relaxants and migraine medications may also help prevent chronic tension headaches. Doctors can select one based on a patient's lifestyle, for example, avoiding one that is sedating during the daytime, says Katherine Henry, chief of neurology at Bellevue Hospital Center and a member of the faculty at NYU School of Medicine in New York City.

Although the precise mechanism of headache pain is elusive, plenty of things seem to exacerbate headaches in susceptible people. "A lot of the things that trigger migraines are also triggers for tension-type headaches," Dr. Diamond says.

How's the Head?

Tension headaches are dull, aching, non-pulsating vise-like pain, usually on both sides that primarily occurs in the forehead and temples.

• 78% of adults experience them at some point

• 40% have had one in the past year

• They can last 30 minutes to several days

• Over-the-counter pain killers such as aspirin acetaminophen, ibuprofen and naproxen sodium can alleviate pain but can also cause headaches if used too often

• Tricyclic antidepressants and some other medications may prevent them

• Triggers include stress, poor posture, lack of sleep, skipping meals, excess caffeine or alcohol, eyestrain

Sources: National Headache Foundation; Journal of the American Medical Association, 1998

One peak time for tension headaches is early morning, which could be due in part to inadequate sleep, interrupted sleep due to obstructive sleep apnea, an awkward sleeping posture, caffeine withdrawal or a hangover.

Another peak time is late afternoon, when the events of the day have people hunching up their shoulders, grinding their teeth and tensing their neck muscles.

Among other office irritants: Eyestrain from staring at a computer screen and working under fluorescent lights and poor air quality in offices where windows don't open.

What's more, skipping lunch can drive blood-sugar levels down, sitting for long periods of time can contribute to muscle soreness and loading up on caffeine can be counterproductive.

"If you drink two cups of coffee, a soda and take two Excedrin [which contains caffeine], you are asking for a headache, and the withdrawal can be intense," says neurologist Alexander Mauskop, director of the New York Headache Center.

Indeed, caffeine withdrawal is why some people experience headaches on weekends, even when the workplace stress has lifted, Dr. Henry says.

Many experts advise patients who get frequent headaches to track them with a headache diary, noting when they start, how long they last and what else was going on that day. Some are even available as apps for smartphones and computers.

There's also no shortage of advice for lifestyle changes that may help stave off tension headaches. Regular exercise and a sensible diet are chief among them.

One recent study of 50,000 Norwegians found that those who exercised at least 30 minutes a day, five days a week, had far fewer migraines or tension headaches than those who didn't.

Finding ways to relax and alleviate stress—such as yoga, massage or isometrix neck exercises—can also help stave off tension headaches.

Several studies have validated the effectiveness of acupuncture for treating tension headaches, since the needles somehow interrupt malfunctioning pain pathways. Some headache experts are also fans of biofeedback, a technique that trains people to control body functions that are normally involuntary, such as heart rate and blood pressure, to relieve tension headaches, although there too, the mechanism is not well understood.

In some cases, tension headaches signal a serious health problem. About 75% of brain tumors start with symptoms that are very similar, including a dull, achiness and feeling of pressure. Still, such cases are rare, involving only about 0.5% of headaches that come to doctors' attention. A sudden, severe headache with neurological symptoms, such as difficulty thinking or numbness on one side could be from a stroke.

Experts stress that people should consult a physician about any chronic headache rather than try to tough it out themselves.

Many people who have frequent tension-type headaches also suffer from "presenteeism"—the opposite of absenteeism, says Dr. Henry. "They keep on going, because they don't want to stop or miss work for 'just a headache.' But they don't function on all cylinders."

That Chronic Head Pain Is Still a Mystery, But Habits Spur Onset

By Melinda Beck : WSJ : March 22, 2011

It's 4 p.m. You've been squinting at the computer all day. The phone won't stop ringing and ... here it is again ... that tightness that wraps around your head and s-q-u-e-e-z-e-s.

Tension headaches are the most common kind of headache, affecting about 40% of people in a given year. Yet they're also the most neglected by medical science and the least understood.

As legions of bleary office workers can attest, tension headaches are one of the most common human afflictions. Melinda Beck explains why chronic tension headaches are also among the most difficult to diagnose and treat.

That's in part because headache experts seldom see them. "In 20 years of practice, I can count on two hands the number of people I've seen with tension-type headaches," says David Dodick, a neurologist with the Mayo Clinic in Phoenix.

Most sufferers just tough them out or treat them with over-the-counter pain killers, which are generally effective. But neurologists warn that taking such pain relievers more than 10 days a month can cause what's known as rebound or medication-overuse headaches, which have the same dull, aching pain as tension headaches themselves.

"They give you temporary relief but they render you vulnerable to another attack," says Dr. Dodick, who is president of the American Headache Society, a professional group of headache experts.

Exactly how and why tension headaches occur is a mystery. Much more is known about migraines, which affect only 12% of the population, but are far more severe and tend to be pulsating and one-sided.

Experts used to believe that tension headaches were caused mainly by muscle tension, especially in the neck, back and shoulders. But studies using electronic sensors to measure muscle contractions found no consistent correlation between headaches, muscle tension or tenderness around the head. In fact, some sufferers had more muscle tension on headache-free days.

The Daily Grind

Another theory held that the tension was emotional or psychological—a physical manifestation of anxiety and stress. But there isn't a clear correlation there either. Some people under enormous stress never get headaches, and some people get them even at times of little stress.

"It's no longer clear to anybody that anything is tense," says Richard Lipton, vice chairman of neurology at Albert Einstein School of Medicine in the Bronx, N.Y., who says that realization was what prompted the International Headache Society, which officially classifies headache disorders, to adopt the term "tension-type headaches" in 1988.

Now many headache experts believe that people who get tension-type headaches have a dysfunction in the pain-perceiving areas of the brain that make them overly sensitive to stimulation at times. This so-called central sensitization is also thought to be the same mechanism involved in fibromyalgia, a mysterious, widespread pain disorder.

To be sure, tension headaches often involve sore, contracted muscles—but experts now think the pain perception starts in the brain and is referred out to those areas, rather than vice versa. Similarly, under this theory, stress doesn't cause the headache, but it does amplify the pain.

Tension headaches often go hand-in-hand with depression, although it's not clear which comes first. "People who are depressed have increased rates of headaches, and people who have frequent headaches often become depressed," Dr. Lipton notes.

A class of older antidepressants called tricyclics, such as amitriptyline (Elavil) or imipramine (Tofranil), are effective at staving off chronic tension-type headaches in many people who have not found relief with over-the-counter medications. Experts think the drugs' pain-relieving properties prevent the headaches; the dosage is usually far lower than would be used for depression alone. Tricyclics don't cause rebound headaches like other pain killers, but side effects can include drowsiness, dizziness and low blood pressure.

"We know these drugs work on pain receptors, but we still aren't clear on the exact mechanism, even though they've been available for 50 years," says Merle Diamond, associate director of the Diamond Headache Center in Chicago.

Anti-seizure drugs, muscle relaxants and migraine medications may also help prevent chronic tension headaches. Doctors can select one based on a patient's lifestyle, for example, avoiding one that is sedating during the daytime, says Katherine Henry, chief of neurology at Bellevue Hospital Center and a member of the faculty at NYU School of Medicine in New York City.

Although the precise mechanism of headache pain is elusive, plenty of things seem to exacerbate headaches in susceptible people. "A lot of the things that trigger migraines are also triggers for tension-type headaches," Dr. Diamond says.

How's the Head?

Tension headaches are dull, aching, non-pulsating vise-like pain, usually on both sides that primarily occurs in the forehead and temples.

• 78% of adults experience them at some point

• 40% have had one in the past year

• They can last 30 minutes to several days

• Over-the-counter pain killers such as aspirin acetaminophen, ibuprofen and naproxen sodium can alleviate pain but can also cause headaches if used too often

• Tricyclic antidepressants and some other medications may prevent them

• Triggers include stress, poor posture, lack of sleep, skipping meals, excess caffeine or alcohol, eyestrain

Sources: National Headache Foundation; Journal of the American Medical Association, 1998

One peak time for tension headaches is early morning, which could be due in part to inadequate sleep, interrupted sleep due to obstructive sleep apnea, an awkward sleeping posture, caffeine withdrawal or a hangover.

Another peak time is late afternoon, when the events of the day have people hunching up their shoulders, grinding their teeth and tensing their neck muscles.

Among other office irritants: Eyestrain from staring at a computer screen and working under fluorescent lights and poor air quality in offices where windows don't open.

What's more, skipping lunch can drive blood-sugar levels down, sitting for long periods of time can contribute to muscle soreness and loading up on caffeine can be counterproductive.

"If you drink two cups of coffee, a soda and take two Excedrin [which contains caffeine], you are asking for a headache, and the withdrawal can be intense," says neurologist Alexander Mauskop, director of the New York Headache Center.

Indeed, caffeine withdrawal is why some people experience headaches on weekends, even when the workplace stress has lifted, Dr. Henry says.

Many experts advise patients who get frequent headaches to track them with a headache diary, noting when they start, how long they last and what else was going on that day. Some are even available as apps for smartphones and computers.

There's also no shortage of advice for lifestyle changes that may help stave off tension headaches. Regular exercise and a sensible diet are chief among them.

One recent study of 50,000 Norwegians found that those who exercised at least 30 minutes a day, five days a week, had far fewer migraines or tension headaches than those who didn't.

Finding ways to relax and alleviate stress—such as yoga, massage or isometrix neck exercises—can also help stave off tension headaches.

Several studies have validated the effectiveness of acupuncture for treating tension headaches, since the needles somehow interrupt malfunctioning pain pathways. Some headache experts are also fans of biofeedback, a technique that trains people to control body functions that are normally involuntary, such as heart rate and blood pressure, to relieve tension headaches, although there too, the mechanism is not well understood.

In some cases, tension headaches signal a serious health problem. About 75% of brain tumors start with symptoms that are very similar, including a dull, achiness and feeling of pressure. Still, such cases are rare, involving only about 0.5% of headaches that come to doctors' attention. A sudden, severe headache with neurological symptoms, such as difficulty thinking or numbness on one side could be from a stroke.

Experts stress that people should consult a physician about any chronic headache rather than try to tough it out themselves.

Many people who have frequent tension-type headaches also suffer from "presenteeism"—the opposite of absenteeism, says Dr. Henry. "They keep on going, because they don't want to stop or miss work for 'just a headache.' But they don't function on all cylinders."

The Rebound Phenomenon

A Hidden Cause of Headache Pain

Sometimes, the cure is worse than the disease. Sometimes, the cure is the disease.

Four percent of Americans suffer headaches daily, and scientists have suspected culprits as diverse as undiagnosed jaw disorders, genetic susceptibility and stress. But according to recent research, a sizeable and growing number of headaches are being caused by the very medications taken to alleviate them — and the problem is far more common than scientists had realized. Half of chronic migraines, and as many as 25 percent of all headaches, are actually “rebound” episodes triggered by the overuse of common pain medications. Both prescription and over-the-counter drugs may be to blame.

Patients begin by popping too many pills to deal with a migraine or a simple tension-type headache. When the medications stop, another headache follows, similar to a hangover. Sufferers race again to the medicine cabinet, and before long they are locked in a cycle of headaches and overmedication.

At any given time, more than three million Americans are suffering from headaches they are inflicting on themselves, according to Dr. Stephen D. Silberstein, a professor of neurology and director of the Jefferson Headache Center at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia. “If a patient’s headaches have grown markedly worse or more frequent, the problem is almost always medication overuse,” Dr. Silberstein said.

The International Headache Society last year published revised criteria to help doctors recognize and treat headaches from medication overuse. Signs of trouble include headaches that occur 15 or more days a month, according to the society, along with the heavy use of pain medications for three months or more. Overuse is defined as taking pain medication for 15 or more days a month.

“Overuse has less to do with how many pills you take to relieve a single headache than with how often you take them,” said Dr. Robert Kunkel, a headache specialist at the Cleveland Clinic Headache Center. “If you get more than two headaches a week and take pain pills for them, you’re at risk.”

The only way to know whether medication is contributing to your headaches is to stop taking them. Unfortunately, it can take as long as two months for medication-dependent patients to see an improvement.

Migraine sufferers seem to be especially susceptible to rebound episodes. Many doctors begin weaning these patients off painkillers by prescribing drugs to help prevent attacks, then gradually reducing doses of the painkillers used to treat acute episodes.

Several drugs have been approved to prevent migraines. The most recent is topiramate (Topamax), which studies suggest may lessen the frequency of attacks for up to 14 months. In addition, early trials suggest that Botox injected into the scalp can prevent or reduce the frequency of both migraines and tension headaches.

(Although not yet approved by the Food and Drug Administration for headaches, botulinum toxin is being offered by a growing number of headache clinics. When it works — which is by no means certain — it can provide relief for up to three months.)

Tension headaches can frequently be prevented with stress reduction techniques and avoidance of certain triggers. With close attention to prevention, sufferers should not need to resort to painkillers often enough to risk rebounding.

Yet almost any kind of pain pill can cause rebound problems if used to excess. Among over-the-counter drugs, those with caffeine, like Excedrin, are the likeliest villains, studies show. Among prescription drugs, triptans are most commonly associated with rebounding, Dr. Silberstein said.

But in terms of both rebound and dependence, the most problematic drugs are those containing butalbital, a barbiturate. Two such medications, Fioricet and Fiorinal, have been banned in Germany because they so often led to medication-related headaches. Both are still prescribed in the United States.

Now that research has begun to spotlight the extent of the problem of medication-overuse headaches, more and more doctors on are on the lookout for signs of trouble. “Believe me, a lot of patients don’t want to hear that they have to stop taking their pain pills in order to get relief,” Dr. Kunkel said. “But for these kinds of headaches, that’s really the only solution.”

Once weaned from medicine, most patients show significant improvement after three months. They also learn their lesson and steer clear of overusing pain pills, research shows. In one study, 87 percent continued to report significant improvement two years after stopping overusing painkillers. Many headache sufferers have been praying for a miracle cure. Now it’s here, though it may not be what they expected.

Questions for Your Doctor

What to Ask About Headaches

Confronting a new diagnosis can be frightening — and because research changes so often, confusing. Here are some questions you may not think to ask your doctor, along with notes on why they’re important.

Could my headache be a symptom of something serious? Or a preventable underlying condition?

Most headaches are not a symptom of underlying diseases. Still, one recent study found that a surprising number of people who had received a diagnosis of tension headache were actually suffering from temporomandibular joint disorder, or TMJ, a jaw condition that can be brought on by injury or habitual clenching or grinding. Researchers were able to reproduce the pain of tension headaches by manipulating the temporalis muscle involved in TMJ.

How do I know I have a tension-type headache and not a migraine?

Although the symptoms of tension-type and migraine headaches are distinct, there is overlap. Some people suffer both types — so-called mixed headaches. Making the right diagnosis is important for effective treatment.

Is there anything I can do to ease headache pain without taking a medication?

Meditation, relaxation techniques, self-massage and even gentle exercise help some people ease headaches. In one recent study, people had fewer and less intense headaches after performing gentle flexing exercises of the head and neck for 10 minutes twice a day. Daily relaxation exercises combined with osteopathic treatments reduced the frequency of headaches in another recent study.

What are the most effective over-the-counter pain relievers?

A wide range of nonprescription headache remedies is available, but overuse of them actually worsens headache pain and leads to chronic headaches.

Is there anything I can do to prevent tension-type headaches?

Lifestyle changes, like getting more exercise and eating a balanced diet, may help ward off headaches. Yoga and meditation may be especially helpful. If stress triggers your headaches, learning relaxation techniques could also help.

How do I recognize triggers for headache pain?

Hunger, fatigue, stress and a variety of other triggers can bring on a headache. Some doctors recommend keeping a diary to identify your own triggers, the better to avoid them.

Can muscle relaxants or other prescription drugs help?

Muscle relaxants or low-dose antidepressants, taken regularly, have been shown to ward off serious tension-type headaches.

Are there experimental treatments that would help?

One treatment in particular, Botox injections into the muscles of the neck and head, is showing promise for intractable headache pain. Other promising approaches are being tested in clinical trials.

My child suffers from regular headaches. Are there any special concerns?

As with adults, it is important that underlying causes of headaches be investigated in children. Stress, including pressures to receive good grades or to fit in with peers at school, is a common trigger for tension headaches in children, according to a recent report from the National Headache Foundation. Insomnia and difficulty falling asleep are a common consequence.

Both articles by Peter Jaret

Leaving the Rabbit Hole

By Paula Kamen : NY Times : February 19, 2008

The worst thing, to me, about having a non-stop multi-year headache isn’t necessarily the pain. Or the way it tends to disrupt intimate relationships, empty all financial reserves, and sabotage the best-laid career plans. It’s not even the endless barrage of (albeit well-meaning) suggestions for “cures” from everyone you meet, most of which you’ve already tried anyway (except for the colon cleansing and the Jews for Jesus conversion).

No, it’s the emotional suffering – from all the guilt and the shame, of patients like me thinking it’s our entire fault, and maybe all in our heads.

But, in the past several years of the past 17 of life with my Headache, I’ve learned to reduce much of my nagging self-blame through basic education about neurology. Compared to when I started, I am now infinitely more informed about this particular and absurd disorder, clinically termed “chronic daily headache,” defined as having a headache at least 15 days a month, for at least four hours a day. And I know such education about of this condition can also help to greatly relieve others’ similar suffering, to make their journeys seem less isolated, subterranean and peculiar. It’s a key step to begin to leave the rabbit hole.

For an update on the growing tide of myth-busting scientific research on chronic daily headache, which could also apply to many types of chronic pain disorders, I talked to neurologist Lawrence Robbins. I most came to appreciate him several years ago using his research for my 2005 book on the topic, “All In My Head” (as well as by being his patient). He has operated a headache clinic in Northbrook, Ill., for 20 years, and is assistant professor of neurology at Rush Medical College in Chicago. He also was just awarded the national pain management award by the American Academy of Pain Management. He believes in making patients informed, which is a goal of his Web site, headachedrugs.com (which has as a new addition this week “Headache 2008-9,” a free 72-page update). And he has been an advocate for the toughest cases as founder of a section of the American Headache Society on “refractory” headache patients (those that don’t respond to treatment); basically that means C.D.H. patients, who comprise a majority of that group, he said.

But, while he helps many patients, I most appreciate him for admitting when he doesn’t know something. Contrary to what many doctors may think, we patients prefer this approach over the alternative, mainly characterizing the pain as psychosomatic or prescribing ill-fated and possibly expensive treatments just to send the patient home with something that looks like a “treatment.”

At the start of our conversation, Dr. Robbins recognized that recent advanced scientific research about the dynamics of C.D.H. in the brain has not yet translated into equally advanced treatments. This is in contrast, very relatively speaking, to the experience of migraine patients. Their lot was improved, starting in 1992, with the introduction of Imitrex, the first of about a dozen “triptans” currently on the market. While they don’t work for all, are costly for the average person (costing at least $20 per pill), and carry their own side effects, they are more effective than any other tool previously available to abort a migraine at the first sign of attack. Meanwhile, the C.D.H. patients are still left in the dust with poorer treatments.

He stressed that a well-known problem with the typical daily preventive drugs prescribed to C.D.H. patients, all stolen from other drug classes (such as anti-seizure medications), is their long-term effectiveness. It’s actually not difficult to get short-term relief for any type of pain, whether from daily “preventives,” the friendly neighborhood opium den, mother’s little helpers, or a distraction from a kick in the kneecaps. Finding a drug that you can take every day, and not be reduced to a hazy-brained zombie unable to tell time, is the challenge. In 1999 and 2004, Dr. Robbins conducted two similar studies of 540 C.D.H. patients to determine how many were able to stay on a medication for at least nine months. In both, only 46 percent were able to stick this out because of diminishing effectiveness, intolerable side effects, or both. (The first was published in the Journal of the American Academy of Pain Management in October of 1993, and the second was presented as an abstract at the 2003 meeting of the American Headache Society.)

Ignoring these limits, often doctors blame the patients for the drugs not working. This is a common pattern in medicine, to use a drug to “scientifically” diagnose a disease. Episodic migraine, which was classified as “psychogenic” over the Freud-governed middle decades of the 20th century, only became credible as biologically “real” in the 1960s with the introduction of a newly effective and much lauded preventive migraine drug, methysergide, actually derived from LSD, which may help explain a possible side effect of terrifying hallucinations. (It’s best known as the brand name Sansert, which was discontinued in the U.S. in 2002 because of potential harm to the heart and kidneys). The superior triptans of the 1990s also helped make migraines more legit.

At same time, Dr. Robbins pointed out the irony that many doctors also are too quick to blame drugs themselves, most specifically over-the-counter painkillers, for causing most chronic daily headaches. He said that highly publicized studies from the past decade overstated the effect of “rebound” headaches, which are caused by the repeated use of pain medications that can gradually make the brain more sensitive to pain. He said that the newest studies, which have been able to take a more long-term approach, show that only “between 33 and 50 percent of patients do achieve long-term benefit from decreasing pain medications.” (Two examples he cited are studies in the journals Cephalalgia from 2005 and Current Opinion in Neurology from 2007) But many doctors still tend to blame the patient who still has pain after tossing out their Excedrins as subconsciously “attaching themselves to” their pain,” forgetting that he or she had daily headaches for 20 years before taking it, he added.

The sheer chronicity of C.D.H., which is what makes it biologically harder to treat, also makes it more suspect. According to creaky psychoanalytic thinking, the more chronic something is, the more the patient is getting something from it, termed as a “secondary gain.” This philosophy was officially thrown out of medicine in the 1970s, but still persists, not so much in medical texts, but in self-help books for general audiences. This is even the case in one of the top-selling mass-market headache-prevention guides of the decade, Dr. David Buchholz’s “Heal Your Headache.” While he certainly gives much valuable advice about lifestyle tools for prevention, he blames those most severe patients who don’t get better with his plan. In a section on “hidden agendas,” he explains patients that he can’t help are likely to be subconsciously attached to their illness: “Being identified as a headache patient – especially a failed [italics his] headache patient – may actually be valuable to some people. At least it’s an identity; it distinguishes you. Giving this up leaves a vacuum, and filling the void may not be so easy.”

This reasoning of tying the most chronic problems to psychological causes also defies basic knowledge of brain chemistry. Researchers are now more informed than ever about the process of “chronification” of disease in the brain. According to advanced brain scans – which now render very few illnesses truly “invisible” – the brain, when pummeled with repeated pain attacks, becomes vulnerable to “central sensitization.” That means that the central nervous system becomes overly sensitive and stuck in a pain feedback loop. That is why doctors like Dr. Robbins recommend early treatment for migraines that seem to be getting more frequent, to break the cycle before they turn into the less treatable chronic daily headache.

“Central sensitization is like kindling logs on a fire,” Dr. Robbins explained. “You also get that with depression. More depression begets more depression. You get that with epilepsy and seizures. You get more seizures. You get more headache and you get more headaches. … And once you get central sensitization where the chemistry of the brain really gets changed more toward a chronic pain state, it’s tough to back up the bus.”

Dr. Robbins also pointed out other common misunderstandings doctors have about C.D.H. patients, which, again, also apply to chronic-pain patients in general. Most are women – more easily dismissed as “complainers.” “In general men are taken more seriously than women in terms of pain,” he said. Women are biologically more prone to central sensitization and chronic pain (and fatigue) disorders. They are three times more likely than men to get episodic migraine and twice as likely to get C.D.H.. And when they have a headache disorder, they are more likely to be disabled by it, with the added jolts of hormonal shifts.

He added that doctors are less likely to take C.D.H. patients seriously because they are indeed very likely to also palpably suffer from anxiety and depression. It’s easy, then, to just blame the pain as being a result of these “mental problems.” But, of course, having non-stop pain would be enough to depress anyone (despite the supposedly newfound glamorous “identity” of pain patient). Again, Brain Chemistry 101 explains the correlation. Head pain can be caused by the same chemical imbalances which lead to anxiety and depression. They are two different results of the same root problem, known as “comorbidities.” (Indeed, some of the most effective preventive drugs taken for headache prevention are antidepressants, which address the same offending neurotransmitters.)

Many patients, hungry for validation, take significant comfort in learning such facts, even when their pain isn’t totally relieved after treatment. Dr. Robbins said that his patients are grateful when they first hear the word “chronic daily headache” at a visit, showing it’s something they didn’t conjure up themselves. “People think that maybe they’ve heard of one other person [with a headache all the time]…Their doctors have marginalized them telling them, ‘Get rid of your husband, quit your job and get off the Excedrin, and your headaches will be fine.’ But when I tell them that millions of people have the same thing, they can’t believe it…It helps a lot to know that they’re not alone.”

As many as one in four chronic headaches is believed to result from the overuse of common pain pills.

Both over-the-counter pain pills and prescription drugs cause medication-overuse headaches.

Signs of trouble from overusing pain pills include headaches that occur 15 or more days a month and have grown worse with the regular use of pain medication.

Sometimes, the cure is worse than the disease. Sometimes, the cure is the disease.

Four percent of Americans suffer headaches daily, and scientists have suspected culprits as diverse as undiagnosed jaw disorders, genetic susceptibility and stress. But according to recent research, a sizeable and growing number of headaches are being caused by the very medications taken to alleviate them — and the problem is far more common than scientists had realized. Half of chronic migraines, and as many as 25 percent of all headaches, are actually “rebound” episodes triggered by the overuse of common pain medications. Both prescription and over-the-counter drugs may be to blame.

Patients begin by popping too many pills to deal with a migraine or a simple tension-type headache. When the medications stop, another headache follows, similar to a hangover. Sufferers race again to the medicine cabinet, and before long they are locked in a cycle of headaches and overmedication.

At any given time, more than three million Americans are suffering from headaches they are inflicting on themselves, according to Dr. Stephen D. Silberstein, a professor of neurology and director of the Jefferson Headache Center at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia. “If a patient’s headaches have grown markedly worse or more frequent, the problem is almost always medication overuse,” Dr. Silberstein said.

The International Headache Society last year published revised criteria to help doctors recognize and treat headaches from medication overuse. Signs of trouble include headaches that occur 15 or more days a month, according to the society, along with the heavy use of pain medications for three months or more. Overuse is defined as taking pain medication for 15 or more days a month.

“Overuse has less to do with how many pills you take to relieve a single headache than with how often you take them,” said Dr. Robert Kunkel, a headache specialist at the Cleveland Clinic Headache Center. “If you get more than two headaches a week and take pain pills for them, you’re at risk.”

The only way to know whether medication is contributing to your headaches is to stop taking them. Unfortunately, it can take as long as two months for medication-dependent patients to see an improvement.

Migraine sufferers seem to be especially susceptible to rebound episodes. Many doctors begin weaning these patients off painkillers by prescribing drugs to help prevent attacks, then gradually reducing doses of the painkillers used to treat acute episodes.

Several drugs have been approved to prevent migraines. The most recent is topiramate (Topamax), which studies suggest may lessen the frequency of attacks for up to 14 months. In addition, early trials suggest that Botox injected into the scalp can prevent or reduce the frequency of both migraines and tension headaches.

(Although not yet approved by the Food and Drug Administration for headaches, botulinum toxin is being offered by a growing number of headache clinics. When it works — which is by no means certain — it can provide relief for up to three months.)

Tension headaches can frequently be prevented with stress reduction techniques and avoidance of certain triggers. With close attention to prevention, sufferers should not need to resort to painkillers often enough to risk rebounding.

Yet almost any kind of pain pill can cause rebound problems if used to excess. Among over-the-counter drugs, those with caffeine, like Excedrin, are the likeliest villains, studies show. Among prescription drugs, triptans are most commonly associated with rebounding, Dr. Silberstein said.

But in terms of both rebound and dependence, the most problematic drugs are those containing butalbital, a barbiturate. Two such medications, Fioricet and Fiorinal, have been banned in Germany because they so often led to medication-related headaches. Both are still prescribed in the United States.

Now that research has begun to spotlight the extent of the problem of medication-overuse headaches, more and more doctors on are on the lookout for signs of trouble. “Believe me, a lot of patients don’t want to hear that they have to stop taking their pain pills in order to get relief,” Dr. Kunkel said. “But for these kinds of headaches, that’s really the only solution.”

Once weaned from medicine, most patients show significant improvement after three months. They also learn their lesson and steer clear of overusing pain pills, research shows. In one study, 87 percent continued to report significant improvement two years after stopping overusing painkillers. Many headache sufferers have been praying for a miracle cure. Now it’s here, though it may not be what they expected.

Questions for Your Doctor

What to Ask About Headaches

Confronting a new diagnosis can be frightening — and because research changes so often, confusing. Here are some questions you may not think to ask your doctor, along with notes on why they’re important.

Could my headache be a symptom of something serious? Or a preventable underlying condition?

Most headaches are not a symptom of underlying diseases. Still, one recent study found that a surprising number of people who had received a diagnosis of tension headache were actually suffering from temporomandibular joint disorder, or TMJ, a jaw condition that can be brought on by injury or habitual clenching or grinding. Researchers were able to reproduce the pain of tension headaches by manipulating the temporalis muscle involved in TMJ.

How do I know I have a tension-type headache and not a migraine?

Although the symptoms of tension-type and migraine headaches are distinct, there is overlap. Some people suffer both types — so-called mixed headaches. Making the right diagnosis is important for effective treatment.

Is there anything I can do to ease headache pain without taking a medication?

Meditation, relaxation techniques, self-massage and even gentle exercise help some people ease headaches. In one recent study, people had fewer and less intense headaches after performing gentle flexing exercises of the head and neck for 10 minutes twice a day. Daily relaxation exercises combined with osteopathic treatments reduced the frequency of headaches in another recent study.

What are the most effective over-the-counter pain relievers?

A wide range of nonprescription headache remedies is available, but overuse of them actually worsens headache pain and leads to chronic headaches.

Is there anything I can do to prevent tension-type headaches?

Lifestyle changes, like getting more exercise and eating a balanced diet, may help ward off headaches. Yoga and meditation may be especially helpful. If stress triggers your headaches, learning relaxation techniques could also help.

How do I recognize triggers for headache pain?

Hunger, fatigue, stress and a variety of other triggers can bring on a headache. Some doctors recommend keeping a diary to identify your own triggers, the better to avoid them.

Can muscle relaxants or other prescription drugs help?

Muscle relaxants or low-dose antidepressants, taken regularly, have been shown to ward off serious tension-type headaches.

Are there experimental treatments that would help?

One treatment in particular, Botox injections into the muscles of the neck and head, is showing promise for intractable headache pain. Other promising approaches are being tested in clinical trials.

My child suffers from regular headaches. Are there any special concerns?

As with adults, it is important that underlying causes of headaches be investigated in children. Stress, including pressures to receive good grades or to fit in with peers at school, is a common trigger for tension headaches in children, according to a recent report from the National Headache Foundation. Insomnia and difficulty falling asleep are a common consequence.

Both articles by Peter Jaret

Leaving the Rabbit Hole

By Paula Kamen : NY Times : February 19, 2008

The worst thing, to me, about having a non-stop multi-year headache isn’t necessarily the pain. Or the way it tends to disrupt intimate relationships, empty all financial reserves, and sabotage the best-laid career plans. It’s not even the endless barrage of (albeit well-meaning) suggestions for “cures” from everyone you meet, most of which you’ve already tried anyway (except for the colon cleansing and the Jews for Jesus conversion).

No, it’s the emotional suffering – from all the guilt and the shame, of patients like me thinking it’s our entire fault, and maybe all in our heads.

But, in the past several years of the past 17 of life with my Headache, I’ve learned to reduce much of my nagging self-blame through basic education about neurology. Compared to when I started, I am now infinitely more informed about this particular and absurd disorder, clinically termed “chronic daily headache,” defined as having a headache at least 15 days a month, for at least four hours a day. And I know such education about of this condition can also help to greatly relieve others’ similar suffering, to make their journeys seem less isolated, subterranean and peculiar. It’s a key step to begin to leave the rabbit hole.

For an update on the growing tide of myth-busting scientific research on chronic daily headache, which could also apply to many types of chronic pain disorders, I talked to neurologist Lawrence Robbins. I most came to appreciate him several years ago using his research for my 2005 book on the topic, “All In My Head” (as well as by being his patient). He has operated a headache clinic in Northbrook, Ill., for 20 years, and is assistant professor of neurology at Rush Medical College in Chicago. He also was just awarded the national pain management award by the American Academy of Pain Management. He believes in making patients informed, which is a goal of his Web site, headachedrugs.com (which has as a new addition this week “Headache 2008-9,” a free 72-page update). And he has been an advocate for the toughest cases as founder of a section of the American Headache Society on “refractory” headache patients (those that don’t respond to treatment); basically that means C.D.H. patients, who comprise a majority of that group, he said.

But, while he helps many patients, I most appreciate him for admitting when he doesn’t know something. Contrary to what many doctors may think, we patients prefer this approach over the alternative, mainly characterizing the pain as psychosomatic or prescribing ill-fated and possibly expensive treatments just to send the patient home with something that looks like a “treatment.”

At the start of our conversation, Dr. Robbins recognized that recent advanced scientific research about the dynamics of C.D.H. in the brain has not yet translated into equally advanced treatments. This is in contrast, very relatively speaking, to the experience of migraine patients. Their lot was improved, starting in 1992, with the introduction of Imitrex, the first of about a dozen “triptans” currently on the market. While they don’t work for all, are costly for the average person (costing at least $20 per pill), and carry their own side effects, they are more effective than any other tool previously available to abort a migraine at the first sign of attack. Meanwhile, the C.D.H. patients are still left in the dust with poorer treatments.

He stressed that a well-known problem with the typical daily preventive drugs prescribed to C.D.H. patients, all stolen from other drug classes (such as anti-seizure medications), is their long-term effectiveness. It’s actually not difficult to get short-term relief for any type of pain, whether from daily “preventives,” the friendly neighborhood opium den, mother’s little helpers, or a distraction from a kick in the kneecaps. Finding a drug that you can take every day, and not be reduced to a hazy-brained zombie unable to tell time, is the challenge. In 1999 and 2004, Dr. Robbins conducted two similar studies of 540 C.D.H. patients to determine how many were able to stay on a medication for at least nine months. In both, only 46 percent were able to stick this out because of diminishing effectiveness, intolerable side effects, or both. (The first was published in the Journal of the American Academy of Pain Management in October of 1993, and the second was presented as an abstract at the 2003 meeting of the American Headache Society.)

Ignoring these limits, often doctors blame the patients for the drugs not working. This is a common pattern in medicine, to use a drug to “scientifically” diagnose a disease. Episodic migraine, which was classified as “psychogenic” over the Freud-governed middle decades of the 20th century, only became credible as biologically “real” in the 1960s with the introduction of a newly effective and much lauded preventive migraine drug, methysergide, actually derived from LSD, which may help explain a possible side effect of terrifying hallucinations. (It’s best known as the brand name Sansert, which was discontinued in the U.S. in 2002 because of potential harm to the heart and kidneys). The superior triptans of the 1990s also helped make migraines more legit.

At same time, Dr. Robbins pointed out the irony that many doctors also are too quick to blame drugs themselves, most specifically over-the-counter painkillers, for causing most chronic daily headaches. He said that highly publicized studies from the past decade overstated the effect of “rebound” headaches, which are caused by the repeated use of pain medications that can gradually make the brain more sensitive to pain. He said that the newest studies, which have been able to take a more long-term approach, show that only “between 33 and 50 percent of patients do achieve long-term benefit from decreasing pain medications.” (Two examples he cited are studies in the journals Cephalalgia from 2005 and Current Opinion in Neurology from 2007) But many doctors still tend to blame the patient who still has pain after tossing out their Excedrins as subconsciously “attaching themselves to” their pain,” forgetting that he or she had daily headaches for 20 years before taking it, he added.

The sheer chronicity of C.D.H., which is what makes it biologically harder to treat, also makes it more suspect. According to creaky psychoanalytic thinking, the more chronic something is, the more the patient is getting something from it, termed as a “secondary gain.” This philosophy was officially thrown out of medicine in the 1970s, but still persists, not so much in medical texts, but in self-help books for general audiences. This is even the case in one of the top-selling mass-market headache-prevention guides of the decade, Dr. David Buchholz’s “Heal Your Headache.” While he certainly gives much valuable advice about lifestyle tools for prevention, he blames those most severe patients who don’t get better with his plan. In a section on “hidden agendas,” he explains patients that he can’t help are likely to be subconsciously attached to their illness: “Being identified as a headache patient – especially a failed [italics his] headache patient – may actually be valuable to some people. At least it’s an identity; it distinguishes you. Giving this up leaves a vacuum, and filling the void may not be so easy.”

This reasoning of tying the most chronic problems to psychological causes also defies basic knowledge of brain chemistry. Researchers are now more informed than ever about the process of “chronification” of disease in the brain. According to advanced brain scans – which now render very few illnesses truly “invisible” – the brain, when pummeled with repeated pain attacks, becomes vulnerable to “central sensitization.” That means that the central nervous system becomes overly sensitive and stuck in a pain feedback loop. That is why doctors like Dr. Robbins recommend early treatment for migraines that seem to be getting more frequent, to break the cycle before they turn into the less treatable chronic daily headache.

“Central sensitization is like kindling logs on a fire,” Dr. Robbins explained. “You also get that with depression. More depression begets more depression. You get that with epilepsy and seizures. You get more seizures. You get more headache and you get more headaches. … And once you get central sensitization where the chemistry of the brain really gets changed more toward a chronic pain state, it’s tough to back up the bus.”

Dr. Robbins also pointed out other common misunderstandings doctors have about C.D.H. patients, which, again, also apply to chronic-pain patients in general. Most are women – more easily dismissed as “complainers.” “In general men are taken more seriously than women in terms of pain,” he said. Women are biologically more prone to central sensitization and chronic pain (and fatigue) disorders. They are three times more likely than men to get episodic migraine and twice as likely to get C.D.H.. And when they have a headache disorder, they are more likely to be disabled by it, with the added jolts of hormonal shifts.

He added that doctors are less likely to take C.D.H. patients seriously because they are indeed very likely to also palpably suffer from anxiety and depression. It’s easy, then, to just blame the pain as being a result of these “mental problems.” But, of course, having non-stop pain would be enough to depress anyone (despite the supposedly newfound glamorous “identity” of pain patient). Again, Brain Chemistry 101 explains the correlation. Head pain can be caused by the same chemical imbalances which lead to anxiety and depression. They are two different results of the same root problem, known as “comorbidities.” (Indeed, some of the most effective preventive drugs taken for headache prevention are antidepressants, which address the same offending neurotransmitters.)

Many patients, hungry for validation, take significant comfort in learning such facts, even when their pain isn’t totally relieved after treatment. Dr. Robbins said that his patients are grateful when they first hear the word “chronic daily headache” at a visit, showing it’s something they didn’t conjure up themselves. “People think that maybe they’ve heard of one other person [with a headache all the time]…Their doctors have marginalized them telling them, ‘Get rid of your husband, quit your job and get off the Excedrin, and your headaches will be fine.’ But when I tell them that millions of people have the same thing, they can’t believe it…It helps a lot to know that they’re not alone.”

As many as one in four chronic headaches is believed to result from the overuse of common pain pills.

Both over-the-counter pain pills and prescription drugs cause medication-overuse headaches.

Signs of trouble from overusing pain pills include headaches that occur 15 or more days a month and have grown worse with the regular use of pain medication.

Beware, a Big Headache Is Coming

Spotting Often-Overlooked Clues Like Nausea, Fatigue, Even Yawns May Help Patients Stave Off Attack

By Melinda Beck : WSJ : June 7, 2011

A migraine is among the most debilitating conditions in medicine—a blinding, throbbing pain that typically lasts between four and 72 hours. There is no cure.

Yet, a few hours or days before the dreaded headache sets in, subtle symptoms emerge: Some people feel unusually fatigued, cranky or anxious. Some have yawning jags. Others have food cravings or excessive thirst.

If migraine sufferers can learn to identify their particular warning signs, they may be able to head off the headache pain with medication or lifestyle changes before it begins, experts say.

"The holy grail of migraine treatment would be to have something you could take tonight to ward off an attack tomorrow," says neurologist Peter Goadsby, director of the headache program at the University of California-San Francisco. At a conference of the American Headache Society last week, he and other experts said these early symptoms may hold clues to what causes migraines in the first place.

Scientists have long known about this so-called premonitory phase, which occurs well before the better-known aura, the flashing lights and wavy lines that about 30% of migraine sufferers see shortly before the headache begins. Yet there have been only a handful of clinical trials treating patients in the premonitory stage—in part because the symptoms are so vague. Still, once patients know what to look for, many can identify some early warning signs.

"If you ask the average migraine sufferer, 'Do you have any symptoms a few hours before the headache starts?' about 30% will say yes," says Werner Becker, professor of neuroscience at the University of Calgary in Alberta. But given a list of 20 common signs, from changes in mood, appetite or energy to urinating frequently or yawning excessively, about 80% of patients will say, "Oh yes, I've noticed that," he says.

Dr. Becker says one of his patients frequently feels dizzy and loses her appetite about 6 p.m. and knows that an attack is imminent. She finds that taking the migraine drug rizatriptan—usually taken only after the headache starts—can ward it off. "If she doesn't take it, then the next morning, she wakes up with a full-blown migraine," Dr. Becker says.

Sheena Selvey, a 28-year old special-education teacher in Northbrook, Ill., says she knows a migraine is coming when co-workers say her neck muscles have tightened up. She rubs her neck with an essential peppermint oil until she can inject herself with Imitrex, another medication usually used to stop rather than prevent headache pain. She says such steps have helped reduce attacks to two or three times a month from three or four times a week.

Ben McKeeb, a 35-year-old nursing student in Bellingham, Wash., says his wife noticed that his forehead muscles tense up in the shape of a "V" a few hours before his headaches begin. "I can almost always catch that feeling, and if I do all the right things—stay hydrated, stay out of the sun, get plenty of sleep, don't work too hard—I probably won't get one," he says.

Nationwide, about 36 million Americans suffer from migraines. Although some people use the word very loosely, migraines are far more severe than a typical headache, last longer and tend to involve nausea, vomiting and sensitivity to light. Women are three times as likely as men to get migraines, and they've been diagnosed in children as young as 6 months. Migraines cost the country more than $20 billion a year in lost wages, disability payments and health-care bills, according to the American Headache Society, an organization of health-care professionals who specialize in headaches.

As many as half of all sufferers don't seek treatment, in part because they think there is little doctors can do for them. In fact, treatments are proliferating, including over-the-counter pain relievers for mild cases and a class of drugs called triptans typically used to stop migraine pain. For chronic migraines, doctors also prescribe beta blockers, antiseizure medications and antidepressants, but they have significant side effects and help only about 50% of patients about 50% of the time. More drugs are in clinical trials, and non-drug treatments such as acupuncture, massage, biofeedback and transcranial-magnetic stimulation are also showing some promise at alleviating migraine pain.

Doctors used to tell patients to wait until their headache pain was severe to moderate before taking medication. But that's changing. "Now we know the closer we can get to the beginning of the attack, the better the outcome will be," says David Dodick, president of the American Headache Society and neurologist at the Mayo Clinic in Phoenix.

Experts also think that they can learn a lot about the origin of migraines by studying how the body changes in the premonitory phase.

For example, "Many people tell us that they vomit yesterday's food," says Joel Saper, director of the Michigan Head-Pain and Neurological Institute in Ann Arbor. That's a sign, he notes, that their digestion slowed long before they knew a migraine was coming.

Some experts are also re-examining the role of common migraine triggers such as alcohol, chocolate, red wine, aged cheese and caffeine. It could be that physiological changes in the premonitory phase trigger a sensitivity to such foods, rather than the other way around.

"For years, patients would say they got a migraine because they ate chocolate or pizza or a hot dog," says Dr. Saper. "But when you ask why they ate those things, they say, 'I had this insatiable craving....' We need to understand where that craving came from."

Functional-imaging studies of the brain have revealed another tantalizing clue: During the aura phase, a wave of electrical activity sweeps over the outer, furrowed layer of the brain known as the cortex, at a pace of 2 to 3 millimeters per minute. This wave—known as "cortical spreading depression"—activates nerve cells as it goes, and the symptoms sufferers report typically correspond to the area of the brain the wave is passing over. For example, the patient sees flashing lights and wavy lines when the wave is over the visual cortex, and tingling in the hands and feet when the wave is in the motor cortex. Once the wave passes by, the nerve cells become quiet and spent.

Dr. Goadsby and colleagues at UCSF are conducting more imaging studies to determine what brain activity occurs during the premonitory phase.

Experts say migraine sufferers can help themselves and their physicians by keeping a careful log of when their headaches occur, what they ate, drank and did several days in advance, as well as any early symptoms they experienced. They may notice patterns and find their own warning signs.

And even though there is no scientific evidence that taking medication at that early stage will stave off migraine headaches, some experts say it makes sense for patients to avoid their known triggers if a migraine seems imminent.

"If stress seems to be a trigger, cut back on your schedule, try a relaxation technique, don't plan a 12-hour day," says Dr. Becker. "You could potentially stop an attack."

Migraines Force Sufferers to Do Their Homework

By Lesley Alderman : NY Times Article : January 30, 2010

Migraines may be right up there with root canals and childbirth as one of life’s more painful experiences. But unlike childbirth or dental surgery — the pain of which can be dulled with standard medications — migraines are notoriously tricky to treat.

Those who suffer from these disabling headaches often try a dozen or so medications before they find something that works. What’s more, many migraines do not get properly diagnosed, according to the doctors and researchers I spoke with. That can lead to a lot of extra pain — and expense — for the afflicted.

A reason migraines are so maddeningly elusive is that they are not simply bad headaches. They stem from a genetic disorder (yes, you have your parents to blame) that afflicts 36 million Americans and manifests as a group of symptoms that besides head pain may include dizziness, visual disturbances, numbness and nausea.

Some of the symptoms resemble those from other disorders, like sinus headaches, epilepsy, eye problems or even strokes. And to further complicate matters, sufferers react in varied ways to medications.

“What might be a miracle drug for one person could be a dud for another,” said Dr. Joel Saper, director of the Michigan Headache and Neurological Institute, a treatment and research center in Ann Arbor. “There is no universally effective therapy.”

If that sounds murky, one thing is not: early intervention is important. If you get a migraine every few months and can cope by taking an over-the-counter med, great — you’ve got the problem somewhat under control. But if recurring pain is not responding to your own efforts, seek expert help.

“Some early data suggests that if you let headache pain go without treatment it can lower your threshold for pain down the line,” Dr. Saper said. In other words, untreated headaches can make you more vulnerable to pain.

On the other hand, if you are taking over-the-counter or prescription painkillers two to three days a week for months on end, the medications you are taking to dull pain could worsen your condition. You may then start to experience medication-overuse headaches — a risk for migraine sufferers.

Researchers are learning that pain and the medications used to treat pain can potentially change the biology of the brain.

Receiving good treatment can help you function more effectively, and will probably also save you money over the long term. And if you have health insurance, it should cover most of the relevant medical evaluations and treatments.

Here are suggestions for getting help.

EVALUATION

If you have chronic or disabling headaches that your primary care physician has not been able to manage, see a neurologist who has expertise in treating headaches.

Be sure to ask beforehand about that expertise. Not all neurologists have experience treating migraines.

You might want to see a certified headache specialist. Doctors with this new certification have passed board exams in their area of specialty as well as one on headaches. You can find a list of the approximately 200 certified headache doctors on the Migraine Research Foundation’s Web site.

Before you make an appointment, ask your potential doctor’s assistant, by phone, a few key questions. Find out about the doctor’s experience. And be sure to ask how long the first meeting will last.

“A good doctor will spend at least an hour with you,” said Dr. David W. Dodick, a neurologist at the Mayo Clinic in Arizona.

It’s important for a doctor to take time to listen to your issues, said Claire Louder, 44, who has had migraines since she was 12. She said she has seen a half-dozen doctors over the years.

“The best ones pay attention to what you say,” said Ms. Louder, who is a chamber of commerce executive in Maryland. “One doctor I saw had a treatment plan in mind before I’d said a word. Then she kept telling me my migraines were due to stress, which was an oversimplification.”

A good doctor should be creative and willing to try a variety of treatments.

At your first visit, the doctor will make sure that your headaches are not caused by an underlying illness, like Lyme disease or a brain tumor. Once the doctor is satisfied that your condition is indeed what are called primary migraines, the doctor will ask you detailed questions about your attacks, take a thorough medical history and probably have you keep a diary of your migraine patterns.

STRATEGIES VARY

Be prepared for a multi-tiered approach.

Doctors typically prescribe a triptan drug or an ergot-related drug to help people control infrequent migraine attacks. Both of these drug types influence brain cell reactions that are part of the migraine process.

There are seven types of triptans. Ms. Louder tried five before she found one, rizatriptan — sold under the brand name Maxalt — that worked for her. The best-seller Imitrex (sumatriptan) is available in an affordable generic version.

Triptans are far more popular, but many people who do not respond well to triptans do well with the ergots, such as D.H.E. (dihydroergotamine), Dr. Saper said.

If you have migraines at least weekly your doctor may prescribe a preventative medicine to reduce their frequency of attacks.

“Prescription preventatives are grossly underutilized,” Dr. Dodick said. “They can be extremely effective for some people.”

Preventive medicines, taken every day, include antiseizure drugs, beta blockers and tricyclic antidepressants. Ms. Louder started taking Topomax (topiramate), an antiseizure drug, five years ago and says it has helped to reduce the frequency of her migraines from once a week to once a month.

Your doctor might suggest some natural remedies too — like vitamin B2, coenzyme Q10, magnesium or butterbur, an herb that is sold under the name Petadolex — which some specialists say can help reduce both the frequency and intensity of your headaches. These supplements are not covered by insurers but all are relatively inexpensive.

LIFESTYLE CHANGES

“Migraines are built into the biology of the brain,” Dr. Saper said.

Sufferers inherit a hypersensitivity to physical and emotional events — like stress, noise, certain foods and even bad weather. Learning to identify the circumstances that can set off an attack is important in migraine management.

Dr. Dodick said, “Recognizing triggers can prevent attacks from occurring.” After keeping a diary, Ms. Louder learned, for instance, that low-pressure storm systems, meats with nitrates and many other preservatives induced her migraines.

“Migraine patients don’t respond well to change,” Dr. Dodick said.

Sometimes just keeping one’s patterns and habits predictable can reduce attacks. Lack of sleep, erratic schedules and lots of plane rides are disorienting for even the hardiest people, but they can literally send migraine sufferers to their beds, or worse, to the E.R.

The effectiveness of other nonprescription alternative therapies:

New evidence-based guidelines from the American Academy of Neurology, which will be published soon in the journal Neurology, indicate that several nutritional and alternative remedies may be effective. The guidelines state that Petasites, the purified extract from the butterbur plant, is effective at a dosage of 75 milligrams twice daily and should be offered for migraine prevention.

The guidelines also say that several other remedies are “probably” effective and should be considered for migraine prevention. These remedies are magnesium (at a daily dose of 300 milligrams), MIG-99 (an extract of the herb feverfew) and riboflavin (400 milligrams daily). They say that coenzyme Q10, or CoQ10 (300 milligrams daily), is “possibly” effective and may be considered for migraine prevention.

Combinations of these therapies are commercially available, but the effectiveness of the combination products has not been definitively demonstrated in studies.

There is a scientific rationale for why these products were studied for migraine prevention, and a plausible explanation for a mechanism of action that is relevant to the biology of migraine. For example, some studies suggest that the metabolic capacity of the brain cells in migraine sufferers may not be sufficient to meet the demands of a migraine attack. Therefore, nutrients like CoQ10 and riboflavin, which are “metabolic enhancers” that increase the capacity for each cell in the body, and presumably the brain, to manufacture energy more efficiently, may be helpful. In addition, in placebo-controlled studies, several of these therapies were found to be superior to placebo. So, the sustained response to niacin noted above, and the response of other patients to that and other therapies, is probably not just a placebo effect.

It is important to recognize that all of these treatments are meant to be taken daily to prevent or reduce the occurrence of attacks. None of these treatments are effective for the acute treatment of an attack after it has begun.

New evidence-based guidelines from the American Academy of Neurology, which will be published soon in the journal Neurology, indicate that several nutritional and alternative remedies may be effective. The guidelines state that Petasites, the purified extract from the butterbur plant, is effective at a dosage of 75 milligrams twice daily and should be offered for migraine prevention.

The guidelines also say that several other remedies are “probably” effective and should be considered for migraine prevention. These remedies are magnesium (at a daily dose of 300 milligrams), MIG-99 (an extract of the herb feverfew) and riboflavin (400 milligrams daily). They say that coenzyme Q10, or CoQ10 (300 milligrams daily), is “possibly” effective and may be considered for migraine prevention.

Combinations of these therapies are commercially available, but the effectiveness of the combination products has not been definitively demonstrated in studies.

There is a scientific rationale for why these products were studied for migraine prevention, and a plausible explanation for a mechanism of action that is relevant to the biology of migraine. For example, some studies suggest that the metabolic capacity of the brain cells in migraine sufferers may not be sufficient to meet the demands of a migraine attack. Therefore, nutrients like CoQ10 and riboflavin, which are “metabolic enhancers” that increase the capacity for each cell in the body, and presumably the brain, to manufacture energy more efficiently, may be helpful. In addition, in placebo-controlled studies, several of these therapies were found to be superior to placebo. So, the sustained response to niacin noted above, and the response of other patients to that and other therapies, is probably not just a placebo effect.

It is important to recognize that all of these treatments are meant to be taken daily to prevent or reduce the occurrence of attacks. None of these treatments are effective for the acute treatment of an attack after it has begun.