- RETIREMENT ANNOUNCEMENT

- HOME PAGE

- "MYCHART" the new patient portal

- BELMONT MEDICAL ASSOCIATES

- MOUNT AUBURN HOSPITAL

- EMERGENCIES

- PRACTICE PHILOSOPHY

- MY RESUME

- TELEMEDICINE CONSULTATION

- CONTACT ME

- LAB RESULTS

- ePRESCRIPTIONS

- eREFERRALS

- RECORD RELEASE

- MEDICAL SCRIBE

- PHYSICIAN ASSISTANT (PA)

- Medicare Annual Wellness Visit

- Case management/Social work

- Quality Care Measures

- Emergency closing notice

- FEEDBACK

- Talking to your doctor

- Choosing..... and losing a doctor

- INDEX A - Z

- ALLERGIC REACTIONS

- Alternative Medicine

- Alzheimer's Disease

- Bladder Problems

- Blood disorders

- Cancer Concerns

- GENETIC TESTING FOR HEREDITARY CANCER

- Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

- Controversial Concerns

- CPR : Learn and save a life

- CRP : Inflammatory marker

- Diabetes Management

- Dizziness, Vertigo,Tinnitus and Hearing Loss

- EXERCISE

- FEMALE HEALTH

-

GASTROINTESTINAL topics

- Appendicitis

- BRAT diet

- Celiac Disease or Sprue

- Crohn's Disease

- Gastroenterologists for Colon Cancer Screening

- Colonoscopy PREP

- Constipation

- Gluten sensitivity, but not celiac disease

- Heartburn and GERD

- Hemorrhoids and Anal fissure

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- NASH : Non Alcoholic Steato Hepatitis

- FEET PROBLEMS

- HEART RELATED topics

-

INFECTIOUS DISEASES

- Antibiotic Resistance

- Cat bites >

- Clostridia difficile infection - the "antibiotic associated germ"

- CORONA VIRUS

- Dengue Fever and Chikungunya Fever

- Food borne illnesses

- Shingles Vaccine

- Hepatitis B

- Hepatitis C

- Herpes

- Influenza

- Helicobacter pylori - the "ulcer germ"

- HIV Screening

- Lyme and other tick borne diseases

- Measles

- Meningitis

- MRSA (Staph infection)

- Norovirus

- Sexually Transmitted Diseases

- Shingles (Herpes Zoster)

- Sinusitis

- West Nile Virus

- Whooping Cough (Pertussis)

- Zika virus and pregnancy

- INSURANCE related topics

- KIDNEY STONES

- LEG CRAMPS

- LIBRARY for patients

- LIFE DECISIONS

- MALE HEALTH

- Medication/Drug side effects

- MEDICAL MARIJUANA

- MENTAL HEALTH

- Miscellaneous Articles

-

NUTRITION - EXERCISE - WEIGHT

- Cholesterol : New guidelines for treatment

- Advice to lower your cholesterol

- Cholesterol : Control

- Cholesterol : Raising your HDL Level

- Exercise

- Food : Making Smart Choices

- Food : Making Poor Choices

- Food : Grape Fruit and Drug Interaction

- Food : Vitamins, Minerals and Supplements

- Omega 3 fatty acids

- Vitamin B12 deficiency

- Vitamin D

- Weight Loss

- ORTHOPEDICS

- PAIN

- PATIENTS' RIGHTS

- SKIN

- SLEEP

- SMOKING

- STROKE

- THYROID

- SUBSTANCE ABUSE

- Travel and Vaccination

- TREMOR

- Warfarin Anticoagulation

- OTHER STUFF FOLLOWS

- Fact or Opinion?

- Hippocratic Oath

- FREE ADVICE.......for what its worth!

- LAUGHTER.....is the best medicine

- Physicians Pet Peeves

- PHOTO ALBUM - its not all work!

- Cape Town, South Africa

- Tribute page

- The 100 Club

- Free Wi-Fi

CANCER CONCERNS

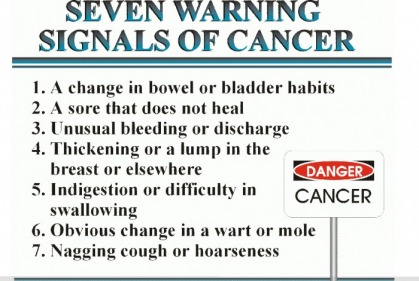

Be aware of cancer's warning signs:

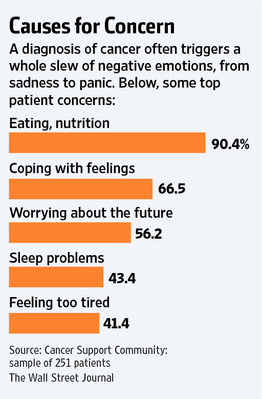

How Much Do You Want to Know About Your Cancer?

By Mikkael A. Sekeres, MD and Timothy D. Gilligan, MD : NY Times : June 1, 2016

Your appointment is at 2:00 on a Tuesday afternoon. It’s your first visit to the cancer center. You’re probably wondering what we are going to say to you. A tumor was recently detected in your left lung and has spread to your bones and liver. A biopsy was performed.

We’re meeting you for the first time, soon after your primary care doctor, or surgeon, has sat down with you, or called, to tell you some terrible news: You have cancer.

We are the oncologists, and we want to help. We want to discuss your diagnosis, what it means and what the options are for treatment. We’d like to give you a clear map of what your life might look like over the next few months as we fight along with you to minimize the amount of this awfulness, even if temporarily, from your body. We want to answer all of your questions.

But one of the biggest problems we face is that we often can’t figure out what our patients would like to know about their prognosis.

Even when we ask.

Spoiler alert: Despite all the exciting stories about progress against cancer that you’ve heard about in the news, there is no cure for most types of cancer once they have spread to other organs. On average, people with lung cancer like yours that has metastasized live another 18 months.

How much of this do you want to know?

It’s a lot to take in. Two months ago you felt fine, and now you have a life expectancy of one to two years. It’s probably the worst news you’ve ever been told. Next year is your 20th wedding anniversary, and your two teenage children don’t even know yet that you are sick. So in many ways, our lament is completely unfair – it’s on us to determine the right time to discuss prognosis.

What can we do to help?

We have all the facts at our fingertips: average survival; likelihood of being alive in five or 10 years; likelihood that chemotherapy will work; and even how long it might work. We will try to put the information in context, adjusting it for your particular situation, and be sure to emphasize that the data were developed in a specific population of patients and may not apply to you as an individual.

Oh, did you not want to hear numbers?

We can roll with that.

We can speak in generalities. We can use phrases such as “likely to be effective” or “most of the time.” We can say, “some people” or “live for years.” Or months.

If that’s what you’d like. But what we don’t want is to be one of “those” doctors.

You know what we mean. The doctors who never talk to their patients about likely outcomes, or life expectancy, and who don’t prepare them for the inevitable. One of us conducted a study in 348 patients with bone marrow cancers in which 35 percent of those patients reported never having discussed prognosis with their doctors. In another study, 74 percent of a similar group of patients estimated their chance for cure to be greater than 50 percent, while their doctors estimated the chance for cure in that same set of patients to be less than 10 percent.

We will do anything to avoid your returning to us with the regret, “I didn’t have time to plan.” Or your widow writing a letter to castigate us with “You never warned me.”

We want to give you time. We want to warn you. Sometimes we advise you to talk to your children’s teachers so that they know there is a crisis at home. Or to put your affairs in order. But often, we just can’t figure out what you want to hear.

And we get it. We would be just as blown away at a cancer diagnosis, and would have just as much difficulty processing all of the information. When we look into your face and really try to connect with you, to read your emotions, we often see fear. And sadness. And regret. And disbelief. And sometimes hopelessness.

We want to give you hope.

At the very least, we don’t want to dash your hopes. We’ll focus on the positives, the best-case scenarios. We’ll tell stories about some of our superstar patients, the poster children for cancer survival, the ones who ignored the statistics and have lived to brag about it.

But we need to place that hope in the staid court of likelihoods. After all, we aren’t hucksters. This balance, between hope and honesty, remains an uneasy truce in medicine. We want you to believe us, to trust us. We recognize that, in some ways, you are placing that most precious of possessions, your own life, in our hands. And we view this as a sacred bond: We will earn your trust by always speaking the truth, though not necessarily all of it.

The inescapable fact is that a tragedy is unfolding and we’re the bearer of the news. A life will be cut down prematurely, young children will be left without one of their parents, a spouse will be left on his or her own. It’s unfair and we can’t stop it. We wish we had more to offer and believe us, the enormity of the tragedy often makes us weep. And yet, our sadness probably doesn’t help you.

So please tell us. How much would you like to know?

Breast Cancer Treatment and D.C.I.S.: Answers to Questions About New Findings

By Gina Kolata : NY Times : Aug. 20, 2015

Q. What is D.C.I.S.?

A. D.C.I.S. stands for ductal carcinoma in situ. It is a small pileup of abnormal cells in the lining of the milk duct. You cannot feel it because there is nothing to be felt; there is no lump. But the cells can be seen in a mammogram, and when a pathologist examines them, they can look like cancer cells. The cells have not broken free of the milk duct or invaded the breast. And they may never break free. The lesion might go away on its own or it might invade the breast or spread throughout the body. That raises questions about what, if anything, to do about it.

Q. Is D.C.I.S. cancer?

A. It is often called Stage 0 cancer, but researchers say their view of cancer is changing. They used to think cancers began as clusters of abnormal cells, and unless they were destroyed the cells would inevitably grow and spread and kill. Now they know that many — some say most or all — cancers can behave in a variety of ways. Clusters of abnormal cells like D.C.I.S. can sometimes disappear, stop growing or simply remain in place and never cause a problem. The suspicion is that the abnormal cells may be harmless and may not require treatment. But no one has done a rigorous study comparing outcomes for women who get treatment to those who get no treatment.

“The development of D.C.I.S. treatments and its handling over the past 40 years is an example of something we in medicine could have done better,” said Dr. Otis Brawley, chief medical officer for the American Cancer Society.

Q. How many women get a D.C.I.S. diagnosis each year?

A. About 60,000 in the United States as compared with several hundred annually before 1983, when mammography was less widespread.

Q. How is D.C.I.S. treated?

A. The majority of women get a lumpectomy, sometimes with radiation therapy, sometimes without. Most of the rest have a mastectomy and some choose to have a double mastectomy, removing the healthy breast as a preventive measure.

Q. What did the new study on D.C.I.S. outcomes show?

A. The study analyzed data from 100,000 patients followed over 20 years, the most extensive collection of data ever analyzed on the condition. It found that there was essentially no difference in the death rate from breast cancer between the group that had lumpectomies with or without radiation and the group that had mastectomies. In both groups the risk of dying from breast cancer after 20 years was very low, about 3.3 percent. That is close to the odds that an average woman will die of breast cancer.

If D.C.I.S was an early cancer that, if not destroyed, would spread into the breast, then women who had their breasts removed would be less likely to develop invasive cancers. That did not happen. Also, as an editorial accompanying the new study pointed out, if treating D.C.I.S. was preventing invasive cancers, then the incidence of those cancers should have dropped now that 60,000 cases of D.C.I.S. are being found and treated each year. That also did not happen.

Q. Are some women more at risk than others if they have D.C.I.S.?

A. Yes. The study found that women who are younger than 40, who are black, or whose D.C.I.S cells have molecular markers like those found in more aggressive, invasive cancers have a higher death rate over 20 years, about 7.8 percent.

Q. What should a woman do if she is told she has D.C.I.S.?

A. Because pathology is subjective and the stakes with cancer so high, she might want to get a second opinion. If the diagnosis is D.C.I.S., most doctors would urge treatment until a study shows it is not necessary. But some women are choosing not to be treated while getting frequent monitoring. Dr. Laura Esserman, a breast surgeon and breast cancer researcher at the University of California, San Francisco, is following women who select this course. But, she cautions, “it is not for the faint of heart.”

MOUNT AUBURN HOSPITAL

CANCER GENETICS

AND PREVENTION CLINIC

Director : PRUDENCE LAM, MD

617-575-881

This is a program aimed to educate and provide genetic counseling for individuals at high risk for cancer based on their own personal history of cancer, family history or other risk factors.

Specializing in hereditary predisposition syndromes, in particular breast, ovarian and colon.

Throat Cancer Linked to Virus

By Laura Landro : WSJ : May 31, 2011

A sharp rise in a type of throat cancer among men is increasingly being linked to HPV, the sexually transmitted human papillomavirus that can cause cervical cancer in women.

A new study from the National Cancer Institute warns that if recent trends continue, the number of HPV-positive oral cancers among men could rise by nearly 30% by 2020. At that rate, it could surpass that of cervical cancers among women, which are expected to decline as a result of better screening.

The study is to be presented this week at the annual American Society of Clinical Oncology meeting.

Between 1988 and 2004, the researchers found, the incidence of HPV-positive oropharynx cancers—those that affect the back of the tongue and tonsil area—increased by 225%. Anil Chaturvedi, a National Cancer Institute investigator who led the research, estimates there were approximately 6,700 cases of HPV-positive oropharynx cancers in 2010, up from 4,000 to 4,500 in 2004, and cases are projected to increase 27% to 8,500 in 2020.

HPV Facts Human papillomavirus is the most common sexually transmitted virus in the U.S.

Recent studies show about 25% of mouth and 35% of throat cancers are caused by HPV, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Men account for the majority of cases, and currently the highest prevalence is in men 40 to 55, says Eric Genden, chief of head and neck oncology at Mount Sinai Medical Center in New York. Studies have shown that the cancer can show up 10 years after exposure to HPV, which has become the most common sexually transmitted virus in the U.S.

"We are sitting at the cusp of a pandemic," says Dr. Genden.

Dr. Chaturvedi says more studies are needed to evaluate whether a vaccine now used to prevent HPV for genital warts and genital and anal cancers can prevent oral HPV infections.

The HPV vaccine, Gardasil, made by Merck & Co., was approved in 2006 for girls and young women up to age 26, but while it is routinely recommended, only about 27% of girls have received all three doses needed to confer protection.

The FDA in 2009 approved the vaccine for males ages 9 through 26 to reduce the risk of genital warts, and in 2010 approved it for both sexes for the prevention of anal cancers. However, the CDC has only a "permissive" recommendation for boys, rather than a routine recommendation, meaning doctors generally will only administer it if parents or patients ask for it, says Michael Brady, chairman of the American Academy of Pediatrics infectious disease committee.

Lauri Markowitz, a CDC medical epidemiologist, says the CDC advisory committee that sets vaccine recommendations will review new data related to the issue at a meeting next month. However, at present there aren't any clinical-trial data showing the effectiveness of the vaccine against oral infections, she says.

A Merck spokeswoman says the company has no plans to study the potential of Gardasil to prevent these cancers.

Researchers say it isn't clear why men are at higher risk for HPV-positive oral cancers. But for both men and women a high lifetime number of sex partners is associated with the cancer.

Changes in sexual behaviors that include increased practice of oral sex are associated with the increase, but a 2007 New England Journal of Medicine article also said engagement in casual sex, early age at first intercourse, and infrequent use of condoms each were associated with HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancer. Mouth-to-mouth contact through kissing can't be ruled out as a transmission route.

Most infections don't cause symptoms and go away on their own. But HPV can cause genital warts and warts in the throat, and has been associated with vaginal, vulvar and anal cancers.

Anna Giuliano, chairwoman of the department of cancer epidemiology at the Moffitt Cancer Center in Tampa, Fla., who studies oral HPV infections of men in several countries, says the rise in cancers among men shows it is important for males, as well as girls, to be vaccinated.

Doctors typically don't test for HPV-positive oral cancers. But Jonathan Aviv, director of the voice and swallowing center at New York's ENT and Allergy Associates, says his group looks through a miniature camera inserted through the nose at the back of the throat and tongue, and can biopsy suspicious warts or tumors.

In addition to being asked about symptoms such as hoarseness, difficulty swallowing, a neck mass or mouth sore that won't heal, patients are asked to fill out a risk-assessment sheet that includes the number of lifetime oral-sex partners. "People do get upset sometimes, but if your sexual history puts you at an increased risk for HPV, you should go and see an ear, nose and throat doctor," says Dr. Aviv.

Fortunately, says Mount Sinai's Dr. Genden, those with HPV-positive oral cancers have a disease survival rate of 85% to 90% over five years, higher than those with oral cancers that aren't linked to HPV, but are more commonly linked to alcohol use, tobacco, and radiation exposure.

Philip Keane, a 52-year-old photographer and partner in a marketing firm, found a lump on his neck while shaving, which was initially misdiagnosed as an infection. A scope of his throat showed it was HPV-positive throat cancer. Dr. Genden removed it last July using minimally invasive robotic surgery, and Mr. Keane had 6½ weeks of daily radiation after that, which left him cancer-free.

At first surprised and embarrassed, Mr. Keane says he has no reason to think he was at high risk; while he has young daughters who have been immunized, "I didn't know about HPV in men." He plans to have his 12-year-old son immunized as well.

Red Flags for Hereditary Cancers

By Jane E. Brody : NY Times Article : May 27, 2008

All cancers are genetic in origin. When genes are working properly, cell growth is tightly regulated, as if a stoplight told cells to divide only so many times and no more. A cancer occurs when something causes a mutation in the genes that limit cell growth or that repair DNA damage.

This is true even if the carcinogen is environmental, like tobacco smoke or radon, or if the cause is viral, like Helicobacter pylori or human papillomavirus.

Carcinogenic agents induce cancer by causing genetic mutations that allow cells to escape normal biological controls. Most cancers arise in this way, sporadically in an individual, and may involve several mutations that permit a tumor to grow.

But sometimes, a single potent cancer-causing mutation is inherited and can be passed from one generation to the next. An estimated 5 to 10 percent of cancers are strongly hereditary, and 20 to 30 percent are more weakly hereditary, said Dr. Kenneth Offit, chief of clinical genetics at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York.

Genetic Chances

In hereditary cancer, the mutated gene can be transmitted through the egg or sperm to children, with each child facing a 50 percent chance of inheriting the defective gene if one parent carries it and a 75 percent chance if both parents carry the same defect.

You might be familiar with the BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations that are strongly linked to breast and ovarian cancer in women and somewhat less strongly to breast and prostate cancer in men. A woman with a BRCA mutation faces a 56 to 87 percent chance of contracting breast cancer and a 10 to 40 percent chance of ovarian cancer.

For some hereditary cancer genes, the risks are even greater. A child who inherits a so-called RET mutation faces a 100 percent chance of developing an especially lethal form of thyroid cancer. Likewise, the risk of stomach cancer approaches 100 percent in those with a CDH mutation, Dr. Daniel G. Coit, a surgeon at Memorial Sloan-Kettering, said at a recent meeting there.

Megan Harlan, senior genetic counselor at Sloan-Kettering, said these were red flags that suggest a cancer might be hereditary:

¶Diagnosis of cancer at a significantly younger age than it ordinarily occurs.

¶Occurrence of the same cancer in more than one generation of a family.

¶Occurrence of two or more cancers in the same patient or blood relatives.

For example, a woman with a BRCA mutation is at high risk for both breast and ovarian cancer. A mismatch repair mutation, known as MMR, significantly raises the risk for colon cancer and somewhat for uterine and ovarian cancer. Thus, the occurrence of colon, uterine and ovarian cancers among blood relatives suggests that the family may carry the MMR mutation.

Preventive Actions

Knowing that you have a high-risk cancer gene mutation offers the chance to take preventive actions like scheduling frequent screenings starting at a young age or removing the organ at risk. While surgery is clearly a drastic form of cancer prevention, in the future drugs may be able to thwart cancers in people at high risk, Dr. Offit said.

A third possibility, when a cancer gene runs in a family, is in vitro fertilization and genetic analysis to identify affected embryos and implant those lacking the defective gene.

Ms. Harlan suggested that a woman with a BRCA mutation should start at an early age to conduct monthly breast self-exams and have a doctor examine the breasts two to four times a year. She also advised alternating mammograms and breast M.R.I.’s every 6 to 12 months, starting at age 25.

Likewise, someone who carries an inherited colon cancer gene should start yearly colonoscopies at 20 or 25. A woman with a uterine cancer gene mutation should be screened with sonography and endometrial biopsies yearly and, Dr. Offit added, consider having her uterus removed when she has finished having children.

A growing number of women with BRCA mutations are choosing prophylactic mastectomies and, in some cases, oophorectomies, or removal of the ovaries. That reduces their risk of breast or ovarian cancer 75 percent.

Dr. Coit described a family in which the father and his father both developed thyroid cancer linked to the RET mutation. The younger man’s 6-year-old son was tested and found to carry the same damaged gene. Because the boy was certain to develop thyroid cancer, most likely at a young age, his thyroid was removed. Although the boy will need to take thyroid hormone for the rest of his life, the surgery reduced to zero his chance of developing this often fatal cancer.

Dr. Coit also told of a 33-year-old woman who carried the CDH mutation associated with highly lethal stomach cancer. Her stomach was removed and found to contain three microscopic cancer sites, making her preventive surgery also curative. She is one of 131 patients with the mutation who have had their stomachs removed and a stomachlike pouch created from the small intestine.

The doctor acknowledged that the surgery was a drastic measure, with an operative mortality of 1.5 percent and a complication rate of 53 percent. Most patients cannot eat as much as they used to after the surgery. They develop food intolerances and lose weight, but they do eventually adapt to their new digestive system, Dr. Coit said.

Practical Considerations

Before choosing surgery to reduce risk in an otherwise healthy person, Dr. Coit said these factors should be carefully considered:

¶Possible nonsurgical alternatives.

¶Actual cancer risk from the inherited gene and how much surgery can reduce it.

¶Timing of any operation.

¶Effects of surgery on quality of life.

Another question is how and whether to disclose hereditary cancer risk. Though many people fear limits on their job and ability to obtain affordable health insurance, a federal law was passed this month to prevent such genetic discrimination.

What if someone with a hereditary cancer gene refuses to warn family members of the possible risk and need for tests? These types of questions have begun to arise, in a handful of lawsuits against doctors. In a 1995 case in Florida, for example, the state Supreme Court ruled that a doctor has to inform patients of the risk to family members, but left it to patients to tell them about tests and the potential for prevention.

The deciphering of the human genome has prompted a number of entrepreneurs to cash in on people’s genetic concerns. They offer DNA testing to look for aberrant genes associated with the risk of developing various diseases, especially cancer.

Such testing, when done reliably, might encourage some people to take charge of their health and make better plans for the future. But some professional genetics counselors say this approach to determining cancer risk is fraught with hazards, not the least of which is a false warning of a serious risk that does not exist.

“This kind of testing is premature,” said Dr. Kenneth Offit, chief of clinical genetics at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center. “Some companies are selling research tests for mutations that carry a low risk of causing cancer, leading people to worry needlessly or be falsely reassured.”

Another problem, he said, is the prescription offered after the tests.

“Other companies are telling people what kind of foods to eat and what to put on their skin based on their genes,” Dr. Offit said. “Testing for known cancer genes is legitimate, but often the prescription given for a ‘gene makeover’ is not. Regulation of these labs is sorely needed. And people facing real hereditary cancer risks require intensive professional counseling.

Cancer test a genetic crystal ball for Jewish women

By Lisa Priest : Globe and Mail : May 24, 2008

For the first time in Canada, Jewish women will be offered the chance to alter their genetic destiny by taking a test – at no cost to them – that will determine whether they are at high risk of developing breast and ovarian cancers.

By screening for three inherited breast cancer gene mutations common to those of Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry, Women's College Research Institute scientists have an ambitious goal: to prevent the dreaded disease before it strikes.

They plan to do that by offering adult Jewish women in Ontario, with no known family history of breast or ovarian cancer, the blood test to screen for three specific mutations of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes, beginning this Thursday. Jewish women with a family history of breast or ovarian cancer who have never been tested are also eligible.

If expanding genetic testing to this group proves worthwhile, it could alter the way the testing is offered across Canada by recognizing one's inherent risk of cancer, simply due to ancestry.

The goal of the test is “to prevent cancer,” said Steven Narod, director of the familial breast cancer research unit at Women's College Research Institute in Toronto. One in 44 Ashkenazi Jewish people carry the mutation, he noted; in the general population, an estimated one in 400 individuals carries a mutation in BRCA1 or BRCA2.

For Ashkenazi women, a group with mainly Central and Eastern European ancestry, the test could reveal a risk they never knew they had. Sarah Neumin, a 44-year-old psychotherapist in Toronto, said there was no breast cancer in her family – until her sister was diagnosed with it three years ago. Ms. Neumin has since tested positive for a mutation of the BRCA1 gene that she inherited from her father.

“We had no cancer at all in the family,” said Ms. Neumin, who now undergoes regular screening for breast and ovarian cancer. “We didn't have a lot of females in our extended family who didn't die in the Holocaust. You can't really do a family tree because a lot of people really didn't live that long.”

Canada's Jewish population is overwhelmingly Ashkenazi: 327,360 out of a total of 370,055, according to figures from Charles Shahar, chief researcher of the national census project for UIA Federations Canada. And about half of the Ashkenazi Jewish population – 165,175 – live in Toronto.

Based on the one-in-44 risk factor, 7,440 Ashkenazi Jewish Canadians are unwitting carriers of BRCA1 or BRCA2 genetic mutations.

Until now, Jewish ancestry was not enough to warrant testing for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer anywhere in Canada; nor is there any known organized population screening of Jewish women in the United States. Several years ago, Dr. Narod, who is also a University of Toronto professor, did a trial for recurring mutations among Polish women similar to the one on Jewish women starting next week.

Rabbi Jennifer Gorman, who is also director of youth activities for the United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism, Eastern Canada region, said she can see the test one day being offered the way screening for Tay-Sachs, a fatal genetic lipid storage disorder, is to couples of Jewish ancestry.

“The rate of this gene is so high,” she said. “It will be one of the tests that is normally done.”

A genetic crystal ball

The test is for three genetic mutations that recur in the Jewish population, due to the so-called founder effect, which occurs when a new colony is started by a few members of the original population, often due to geographic or religious isolation.

According to researchers, 40 per cent of today's Ashkenazi Jewish population arose from a group of four founding mothers, who lived somewhere in Europe within the past 2,000 years.

With the marvels of science, their female descendants are being offered the opportunity to peek into the genetic version of a crystal ball. The test has implications for a woman's family: If she tests positive, she must have inherited the genetic mutation from a parent. Her children run a 50-per-cent chance of carrying the gene, as do her siblings. Testing may have implications for those seeking life or critical care insurance, although policies already in place are typically not affected.

Not seeking an answer, however, also carries a steep cost.

About 70 per cent of women who are BRCA1 mutation carriers will develop breast cancer by age 70; about 40 per cent will develop ovarian cancer by the same age. Those who carry the BRCA2 genetic mutation face the same breast cancer risk as those BRCA1 mutation carriers, but their risk of developing ovarian cancer is lower than the BRCA1 group – between 15 and 20 per cent by age 70, according to Dr. Narod's group.

“It empowers women, as far as I'm concerned, to make choices for themselves,” said Rebecca Dent, a medical oncologist at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre in Toronto, who works closely with Dr. Narod.

Women who test positive can be referred to specialized screening. Some of that screening includes magnetic resonance imaging scans of the breasts, pelvic exams, transvaginal ultrasounds and the CA-125 blood test, which measures a protein found in greater concentration in ovarian cancer cells than in other cells, according to the Jewish Population Screening Study paper done by Dr. Narod's research unit.

As well, there are ways to prevent cancer, including drug therapies such as tamoxifen and oral contraceptives. There are also surgical options such as removal of the breasts and ovaries.

By being hooked into a system where the women are followed more closely, there is more opportunity to participate in new drug or screening techniques as they become available, Dr. Dent said.

Dr. Narod, who holds the Canada Research Chair in breast cancer, said the testing is also a good investment: Focusing on those three recurring mutations in the Jewish community means the test is relatively easy to do as the entire genome does not require sequencing.

With the blood test costing about $25 a patient, to be paid for through his research grant, he expects to find a mutation for BRCA1 and BRCA2 in about one in 50 Jewish women. If that turns out to be the case, he estimates it will cost only $1,250 to find someone at high risk of developing breast and ovarian cancer. (Those figures do not include added costs of genetic counselling, laboratory technician time and doctor consultation times.) And finding one patient actually means finding many more – as it leads to the identification and testing of other family members.

Eligible Ontario patients must be willing to travel to Toronto for the test, which is being offered to 1,000 women as part of a research study, at which point it will be re-evaluated.

“If we see 1,000 women with no family history of breast cancer and find no mutation, that tells us the criteria will stay the same,” said Kelly Metcalfe, clinician scientist at Women's College Research Institute. “If we are finding mutations, that suggests the criteria should change, that we should be offering general [Jewish women] population screening to any Ashkenazi Jewish woman who is interested in the test.”

‘No-brainer' testing

Melissa Lieberman-Moses was 32 and in her last trimester of a twin-girl pregnancy in late 2003 when she found a pea-sized lump in her left breast. She had no family history of breast or ovarian cancer, and while doctors thought the lump was probably nothing to worry about, they sent her for an ultrasound, then a biopsy.

It revealed an early-stage breast cancer. She later tested positive for a BRCA1 mutation. As it turned out, that family history hadn't yet revealed itself because her father was the carrier of the genetic mutation.

She underwent a double mastectomy – as well as an oophorectomy, which is removal of the ovaries.

Having the genetic testing, Dr. Lieberman-Moses feels, has saved the lives of some of her family members, who now know what they may face in the future. But she does worry about her children, twins, Aviva and Talia, and son, Sammy, all of whom could be carriers.

“It was worth doing every single measure I could, the most aggressive things I could,” said the 37-year-old Toronto psychologist. “I wanted to live to see my kids get older.” She thinks it's a “good idea for every Jewish woman to get tested so she can take steps to prevent this horrible disease.”

Aletta Poll, genetic counsellor for the familial breast cancer research unit of the Women's College Research Institute, cautioned this test is appropriate only for the Jewish population.

“We're just looking at three specific mutations of these two genes,” Ms. Poll said. “If you are not Jewish and you take this test, it doesn't really mean much. If you are Jewish, you can still have another mutation in these two genes but it's not that likely.”

In a telephone interview, Reform Rabbi Michal Shekel, executive director of the Toronto Board of Rabbis, described the genetic testing as a “no-brainer,” adding that Jewish law – Halacha – insists one is obligated to take care of oneself.

Likewise, Conservative Rabbi Gorman said she can see the testing being talked about among couples the way other genetic diseases are discussed.

“If we know we can reduce our risk and we know we can save lives, then we have to look into the future and say where are we going to go with this,” she said. “… The more education we put out there, the more likely we can conquer this disease. And now, this is one more piece of it.”

Ask Well: Genetic Testing for Breast Cancer

By Roni Caryn Rabin : NY Times : November 27, 2013

Here are answers to some questions about genetic testing for the three common harmful mutations in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes.

Q.

I’m an Ashkenazi Jewish woman. Should I be tested for the mutations in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes?

A.

If you have been diagnosed with breast or ovarian cancer or have a family history of breast or ovarian cancer, you may want to be tested for one of the mutations in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes that are common among Ashkenazi Jews. Knowing your carrier status may help you evaluate your future risk and can be useful information for other family members. If you have cancer, the information can help shape treatment and alert you to other risks (such as a heightened risk for ovarian cancer if you have breast cancer).

While some Israeli doctors want to expand testing and make it routine, general practice in the United States has not encouraged genetic testing for individuals who are cancer-free and don’t have a family history.

But for Ashkenazi Jews, the bar for genetic testing is not as high as for the general population, said Dr. Susan M. Domchek, executive director of the Basser Research Center for BRCA at the University of Pennsylvania’s Abramson Cancer Center.

“If you’re Jewish, we have a low threshold for testing,” Dr. Domchek said. “If you have an aunt who had breast cancer at 51 and you want testing, that’s O.K.”

Keep in mind that the odds of testing positive are fairly low — only one in 40 Ashkenazi Jews, or 2.5 percent, carry the mutation. That is higher than the rate in the general population, in which fewer than 1 percent carry these mutations, but it means you have a 97.5 percent chance of testing negative.

Remember that a family history includes relatives on both sides of the family, including your father’s side.

“People ignore the father’s side of the family, and they shouldn’t,” said Dr. Domchek. “Women will come to us and say there’s no family history, but actually the dad was Ashkenazi Jewish and the dad’s mother had breast cancer at 40 – that’s a significant family history.”

Q.

What if I don’t know much about my family history?

A.

Many Ashkenazi Jews have limited information about their family because they lost relatives in the Holocaust. Others come from small families that don’t provide a lot of clues, and families everywhere become estranged and keep secrets. One reason Israeli doctors want to do broad-based screening of Ashkenazi Jewish women is so that individuals are not dependent on family members for information.

Nevertheless, Dr. Domchek emphasized that there is still some uncertainty about what it means if a woman tests positive for a mutation and no one in her family has had cancer. Research is trying to resolve questions about what the risk is in these cases. “It’s a challenge to give an individualized risk assessment,” she said.

If you are concerned because you have limited information about your family, genetic counseling may help clarify whether you should pursue testing.

Q.

What does the test consist of? How much does it cost? Will insurance cover it?

A.

The genetic test is a blood test, often accompanied by genetic counseling. Testing for the three specific BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations common among Ashkenazi Jews generally costs between $300 and $500 for all three. Insurance coverage varies and may be more likely to pick up the cost if the individual has a clear family history of breast or ovarian cancer. Genetic testing of men who do not have cancer is generally not covered, Dr. Domchek said.

Q.

What does a positive result mean?

A.

A woman who tests positive for a mutation will be given a range of risk for developing breast cancer and ovarian cancer during her lifetime that takes her family history into account, but assessing individual risk is a challenge, Dr. Domchek said. “If the only history is a mother who developed breast cancer at 55 and the mother has four sisters and no one else has cancer of any sort,” then the woman’s risk will be deemed lower than if several of her aunts have cancer, she explained.

While about 12 percent of women in the general population will develop breast cancer at some point in their lives, 55 percent to 65 percent of women with a harmful BRCA1 mutation and around 45 percent of those with a harmful BRCA2 mutation will develop breast cancer by age 70, according to the National Cancer Institute. While about 1.4 percent of women in the general population will develop ovarian cancer, some 39 percent of carriers of a harmful BRCA1 mutation and 11 percent to 17 percent of carriers of a harmful BRCA2 mutation will develop ovarian cancer by age 70.

Q.

What factors should I weigh when considering prophylactic surgery?

A.

Choosing prophylactic surgery is a difficult and highly personal decision. Many doctors emphasize the importance of removing the ovaries, because the mutations increase the risk of ovarian cancer, which is harder than breast cancer to detect at an early stage. Israeli physicians urge women to undergo ovary removal as soon as they have had their children, preferably by the age of 40. Removing the ovaries also reduces the risk of breast cancer considerably.

The choice of whether to have a prophylactic double mastectomy is complex. Close monitoring and surveillance of the breasts with frequent magnetic resonance imaging scans and clinical breast exams is another option, doctors say. Over time, however, doctors say many women tire of the constant checkups, especially if they are called back for frequent biopsies and some eventually opt for mastectomies as a result.

Both oophorectomy and mastectomy are difficult operations that have serious side effects. Breast reconstruction often leads to infections and other complications and many women are disappointed by the look and feel of their new breasts. Removing the ovaries robs women of important hormones and plunges them into menopause overnight, leading to hot flashes, reduced sex drive and heightened risks of heart disease and bone loss. Hormone replacement treatment or other medication is often required.

- Rapid weight loss: shedding several pounds without trying or for no apparent reason

- Blood: appearing where it shouldn't: (urine, stool, sputum, vagina, etc.)

- Lump or swollen gland: lasting 2 or more weeks, especially if painless (most cancerous lumps are pain-free)

- Changes in breasts: size, dimpling, discharge or new lump

- Changes in testicle: size, shape or lump

- Sudden presence of a mole: change in an existing one (size, color, shape, bleeding, itching)

- Unusual sores: especially sores than won't heal

- Chronic fatigue: with no obvious explanation, such as depression, lack of sleep or medications

- Cough, hoarseness or difficulty swallowing: lasting more than 2 weeks and not due to stomach acid reflux or allergies

- Persistent headache: new, unusual or severe, not a typical tension or migraine form

- Any chronic abdominal pain: for which diet and self-care measures don't remedy

How Much Do You Want to Know About Your Cancer?

By Mikkael A. Sekeres, MD and Timothy D. Gilligan, MD : NY Times : June 1, 2016

Your appointment is at 2:00 on a Tuesday afternoon. It’s your first visit to the cancer center. You’re probably wondering what we are going to say to you. A tumor was recently detected in your left lung and has spread to your bones and liver. A biopsy was performed.

We’re meeting you for the first time, soon after your primary care doctor, or surgeon, has sat down with you, or called, to tell you some terrible news: You have cancer.

We are the oncologists, and we want to help. We want to discuss your diagnosis, what it means and what the options are for treatment. We’d like to give you a clear map of what your life might look like over the next few months as we fight along with you to minimize the amount of this awfulness, even if temporarily, from your body. We want to answer all of your questions.

But one of the biggest problems we face is that we often can’t figure out what our patients would like to know about their prognosis.

Even when we ask.

Spoiler alert: Despite all the exciting stories about progress against cancer that you’ve heard about in the news, there is no cure for most types of cancer once they have spread to other organs. On average, people with lung cancer like yours that has metastasized live another 18 months.

How much of this do you want to know?

It’s a lot to take in. Two months ago you felt fine, and now you have a life expectancy of one to two years. It’s probably the worst news you’ve ever been told. Next year is your 20th wedding anniversary, and your two teenage children don’t even know yet that you are sick. So in many ways, our lament is completely unfair – it’s on us to determine the right time to discuss prognosis.

What can we do to help?

We have all the facts at our fingertips: average survival; likelihood of being alive in five or 10 years; likelihood that chemotherapy will work; and even how long it might work. We will try to put the information in context, adjusting it for your particular situation, and be sure to emphasize that the data were developed in a specific population of patients and may not apply to you as an individual.

Oh, did you not want to hear numbers?

We can roll with that.

We can speak in generalities. We can use phrases such as “likely to be effective” or “most of the time.” We can say, “some people” or “live for years.” Or months.

If that’s what you’d like. But what we don’t want is to be one of “those” doctors.

You know what we mean. The doctors who never talk to their patients about likely outcomes, or life expectancy, and who don’t prepare them for the inevitable. One of us conducted a study in 348 patients with bone marrow cancers in which 35 percent of those patients reported never having discussed prognosis with their doctors. In another study, 74 percent of a similar group of patients estimated their chance for cure to be greater than 50 percent, while their doctors estimated the chance for cure in that same set of patients to be less than 10 percent.

We will do anything to avoid your returning to us with the regret, “I didn’t have time to plan.” Or your widow writing a letter to castigate us with “You never warned me.”

We want to give you time. We want to warn you. Sometimes we advise you to talk to your children’s teachers so that they know there is a crisis at home. Or to put your affairs in order. But often, we just can’t figure out what you want to hear.

And we get it. We would be just as blown away at a cancer diagnosis, and would have just as much difficulty processing all of the information. When we look into your face and really try to connect with you, to read your emotions, we often see fear. And sadness. And regret. And disbelief. And sometimes hopelessness.

We want to give you hope.

At the very least, we don’t want to dash your hopes. We’ll focus on the positives, the best-case scenarios. We’ll tell stories about some of our superstar patients, the poster children for cancer survival, the ones who ignored the statistics and have lived to brag about it.

But we need to place that hope in the staid court of likelihoods. After all, we aren’t hucksters. This balance, between hope and honesty, remains an uneasy truce in medicine. We want you to believe us, to trust us. We recognize that, in some ways, you are placing that most precious of possessions, your own life, in our hands. And we view this as a sacred bond: We will earn your trust by always speaking the truth, though not necessarily all of it.

The inescapable fact is that a tragedy is unfolding and we’re the bearer of the news. A life will be cut down prematurely, young children will be left without one of their parents, a spouse will be left on his or her own. It’s unfair and we can’t stop it. We wish we had more to offer and believe us, the enormity of the tragedy often makes us weep. And yet, our sadness probably doesn’t help you.

So please tell us. How much would you like to know?

Breast Cancer Treatment and D.C.I.S.: Answers to Questions About New Findings

By Gina Kolata : NY Times : Aug. 20, 2015

Q. What is D.C.I.S.?

A. D.C.I.S. stands for ductal carcinoma in situ. It is a small pileup of abnormal cells in the lining of the milk duct. You cannot feel it because there is nothing to be felt; there is no lump. But the cells can be seen in a mammogram, and when a pathologist examines them, they can look like cancer cells. The cells have not broken free of the milk duct or invaded the breast. And they may never break free. The lesion might go away on its own or it might invade the breast or spread throughout the body. That raises questions about what, if anything, to do about it.

Q. Is D.C.I.S. cancer?

A. It is often called Stage 0 cancer, but researchers say their view of cancer is changing. They used to think cancers began as clusters of abnormal cells, and unless they were destroyed the cells would inevitably grow and spread and kill. Now they know that many — some say most or all — cancers can behave in a variety of ways. Clusters of abnormal cells like D.C.I.S. can sometimes disappear, stop growing or simply remain in place and never cause a problem. The suspicion is that the abnormal cells may be harmless and may not require treatment. But no one has done a rigorous study comparing outcomes for women who get treatment to those who get no treatment.

“The development of D.C.I.S. treatments and its handling over the past 40 years is an example of something we in medicine could have done better,” said Dr. Otis Brawley, chief medical officer for the American Cancer Society.

Q. How many women get a D.C.I.S. diagnosis each year?

A. About 60,000 in the United States as compared with several hundred annually before 1983, when mammography was less widespread.

Q. How is D.C.I.S. treated?

A. The majority of women get a lumpectomy, sometimes with radiation therapy, sometimes without. Most of the rest have a mastectomy and some choose to have a double mastectomy, removing the healthy breast as a preventive measure.

Q. What did the new study on D.C.I.S. outcomes show?

A. The study analyzed data from 100,000 patients followed over 20 years, the most extensive collection of data ever analyzed on the condition. It found that there was essentially no difference in the death rate from breast cancer between the group that had lumpectomies with or without radiation and the group that had mastectomies. In both groups the risk of dying from breast cancer after 20 years was very low, about 3.3 percent. That is close to the odds that an average woman will die of breast cancer.

If D.C.I.S was an early cancer that, if not destroyed, would spread into the breast, then women who had their breasts removed would be less likely to develop invasive cancers. That did not happen. Also, as an editorial accompanying the new study pointed out, if treating D.C.I.S. was preventing invasive cancers, then the incidence of those cancers should have dropped now that 60,000 cases of D.C.I.S. are being found and treated each year. That also did not happen.

Q. Are some women more at risk than others if they have D.C.I.S.?

A. Yes. The study found that women who are younger than 40, who are black, or whose D.C.I.S cells have molecular markers like those found in more aggressive, invasive cancers have a higher death rate over 20 years, about 7.8 percent.

Q. What should a woman do if she is told she has D.C.I.S.?

A. Because pathology is subjective and the stakes with cancer so high, she might want to get a second opinion. If the diagnosis is D.C.I.S., most doctors would urge treatment until a study shows it is not necessary. But some women are choosing not to be treated while getting frequent monitoring. Dr. Laura Esserman, a breast surgeon and breast cancer researcher at the University of California, San Francisco, is following women who select this course. But, she cautions, “it is not for the faint of heart.”

MOUNT AUBURN HOSPITAL

CANCER GENETICS

AND PREVENTION CLINIC

Director : PRUDENCE LAM, MD

617-575-881

This is a program aimed to educate and provide genetic counseling for individuals at high risk for cancer based on their own personal history of cancer, family history or other risk factors.

Specializing in hereditary predisposition syndromes, in particular breast, ovarian and colon.

Throat Cancer Linked to Virus

By Laura Landro : WSJ : May 31, 2011

A sharp rise in a type of throat cancer among men is increasingly being linked to HPV, the sexually transmitted human papillomavirus that can cause cervical cancer in women.

A new study from the National Cancer Institute warns that if recent trends continue, the number of HPV-positive oral cancers among men could rise by nearly 30% by 2020. At that rate, it could surpass that of cervical cancers among women, which are expected to decline as a result of better screening.

The study is to be presented this week at the annual American Society of Clinical Oncology meeting.

Between 1988 and 2004, the researchers found, the incidence of HPV-positive oropharynx cancers—those that affect the back of the tongue and tonsil area—increased by 225%. Anil Chaturvedi, a National Cancer Institute investigator who led the research, estimates there were approximately 6,700 cases of HPV-positive oropharynx cancers in 2010, up from 4,000 to 4,500 in 2004, and cases are projected to increase 27% to 8,500 in 2020.

HPV Facts Human papillomavirus is the most common sexually transmitted virus in the U.S.

- More than half of sexually active men and women are infected with HPV at some time in their lives.

- About 20 million Americans are currently infected and about six million more get infected each year.

- HPV can cause cervical cancer in women, which is the second-leading cause of cancer deaths in women world-wide.

- HPV is linked to a four- to five-fold increase in certain oral cancers, especially in men; about 25% of mouth and 35% of throat cancers are caused by HPV.

- There are more than 100 different types of HPV virus. Some are low-risk while highrisk types can cause several cancers, including head and neck cancer, which is becoming more prevalent.

Recent studies show about 25% of mouth and 35% of throat cancers are caused by HPV, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Men account for the majority of cases, and currently the highest prevalence is in men 40 to 55, says Eric Genden, chief of head and neck oncology at Mount Sinai Medical Center in New York. Studies have shown that the cancer can show up 10 years after exposure to HPV, which has become the most common sexually transmitted virus in the U.S.

"We are sitting at the cusp of a pandemic," says Dr. Genden.

Dr. Chaturvedi says more studies are needed to evaluate whether a vaccine now used to prevent HPV for genital warts and genital and anal cancers can prevent oral HPV infections.

The HPV vaccine, Gardasil, made by Merck & Co., was approved in 2006 for girls and young women up to age 26, but while it is routinely recommended, only about 27% of girls have received all three doses needed to confer protection.

The FDA in 2009 approved the vaccine for males ages 9 through 26 to reduce the risk of genital warts, and in 2010 approved it for both sexes for the prevention of anal cancers. However, the CDC has only a "permissive" recommendation for boys, rather than a routine recommendation, meaning doctors generally will only administer it if parents or patients ask for it, says Michael Brady, chairman of the American Academy of Pediatrics infectious disease committee.

Lauri Markowitz, a CDC medical epidemiologist, says the CDC advisory committee that sets vaccine recommendations will review new data related to the issue at a meeting next month. However, at present there aren't any clinical-trial data showing the effectiveness of the vaccine against oral infections, she says.

A Merck spokeswoman says the company has no plans to study the potential of Gardasil to prevent these cancers.

Researchers say it isn't clear why men are at higher risk for HPV-positive oral cancers. But for both men and women a high lifetime number of sex partners is associated with the cancer.

Changes in sexual behaviors that include increased practice of oral sex are associated with the increase, but a 2007 New England Journal of Medicine article also said engagement in casual sex, early age at first intercourse, and infrequent use of condoms each were associated with HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancer. Mouth-to-mouth contact through kissing can't be ruled out as a transmission route.

Most infections don't cause symptoms and go away on their own. But HPV can cause genital warts and warts in the throat, and has been associated with vaginal, vulvar and anal cancers.

Anna Giuliano, chairwoman of the department of cancer epidemiology at the Moffitt Cancer Center in Tampa, Fla., who studies oral HPV infections of men in several countries, says the rise in cancers among men shows it is important for males, as well as girls, to be vaccinated.

Doctors typically don't test for HPV-positive oral cancers. But Jonathan Aviv, director of the voice and swallowing center at New York's ENT and Allergy Associates, says his group looks through a miniature camera inserted through the nose at the back of the throat and tongue, and can biopsy suspicious warts or tumors.

In addition to being asked about symptoms such as hoarseness, difficulty swallowing, a neck mass or mouth sore that won't heal, patients are asked to fill out a risk-assessment sheet that includes the number of lifetime oral-sex partners. "People do get upset sometimes, but if your sexual history puts you at an increased risk for HPV, you should go and see an ear, nose and throat doctor," says Dr. Aviv.

Fortunately, says Mount Sinai's Dr. Genden, those with HPV-positive oral cancers have a disease survival rate of 85% to 90% over five years, higher than those with oral cancers that aren't linked to HPV, but are more commonly linked to alcohol use, tobacco, and radiation exposure.

Philip Keane, a 52-year-old photographer and partner in a marketing firm, found a lump on his neck while shaving, which was initially misdiagnosed as an infection. A scope of his throat showed it was HPV-positive throat cancer. Dr. Genden removed it last July using minimally invasive robotic surgery, and Mr. Keane had 6½ weeks of daily radiation after that, which left him cancer-free.

At first surprised and embarrassed, Mr. Keane says he has no reason to think he was at high risk; while he has young daughters who have been immunized, "I didn't know about HPV in men." He plans to have his 12-year-old son immunized as well.

Red Flags for Hereditary Cancers

By Jane E. Brody : NY Times Article : May 27, 2008

All cancers are genetic in origin. When genes are working properly, cell growth is tightly regulated, as if a stoplight told cells to divide only so many times and no more. A cancer occurs when something causes a mutation in the genes that limit cell growth or that repair DNA damage.

This is true even if the carcinogen is environmental, like tobacco smoke or radon, or if the cause is viral, like Helicobacter pylori or human papillomavirus.

Carcinogenic agents induce cancer by causing genetic mutations that allow cells to escape normal biological controls. Most cancers arise in this way, sporadically in an individual, and may involve several mutations that permit a tumor to grow.

But sometimes, a single potent cancer-causing mutation is inherited and can be passed from one generation to the next. An estimated 5 to 10 percent of cancers are strongly hereditary, and 20 to 30 percent are more weakly hereditary, said Dr. Kenneth Offit, chief of clinical genetics at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York.

Genetic Chances

In hereditary cancer, the mutated gene can be transmitted through the egg or sperm to children, with each child facing a 50 percent chance of inheriting the defective gene if one parent carries it and a 75 percent chance if both parents carry the same defect.

You might be familiar with the BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations that are strongly linked to breast and ovarian cancer in women and somewhat less strongly to breast and prostate cancer in men. A woman with a BRCA mutation faces a 56 to 87 percent chance of contracting breast cancer and a 10 to 40 percent chance of ovarian cancer.

For some hereditary cancer genes, the risks are even greater. A child who inherits a so-called RET mutation faces a 100 percent chance of developing an especially lethal form of thyroid cancer. Likewise, the risk of stomach cancer approaches 100 percent in those with a CDH mutation, Dr. Daniel G. Coit, a surgeon at Memorial Sloan-Kettering, said at a recent meeting there.

Megan Harlan, senior genetic counselor at Sloan-Kettering, said these were red flags that suggest a cancer might be hereditary:

¶Diagnosis of cancer at a significantly younger age than it ordinarily occurs.

¶Occurrence of the same cancer in more than one generation of a family.

¶Occurrence of two or more cancers in the same patient or blood relatives.

For example, a woman with a BRCA mutation is at high risk for both breast and ovarian cancer. A mismatch repair mutation, known as MMR, significantly raises the risk for colon cancer and somewhat for uterine and ovarian cancer. Thus, the occurrence of colon, uterine and ovarian cancers among blood relatives suggests that the family may carry the MMR mutation.

Preventive Actions

Knowing that you have a high-risk cancer gene mutation offers the chance to take preventive actions like scheduling frequent screenings starting at a young age or removing the organ at risk. While surgery is clearly a drastic form of cancer prevention, in the future drugs may be able to thwart cancers in people at high risk, Dr. Offit said.

A third possibility, when a cancer gene runs in a family, is in vitro fertilization and genetic analysis to identify affected embryos and implant those lacking the defective gene.

Ms. Harlan suggested that a woman with a BRCA mutation should start at an early age to conduct monthly breast self-exams and have a doctor examine the breasts two to four times a year. She also advised alternating mammograms and breast M.R.I.’s every 6 to 12 months, starting at age 25.

Likewise, someone who carries an inherited colon cancer gene should start yearly colonoscopies at 20 or 25. A woman with a uterine cancer gene mutation should be screened with sonography and endometrial biopsies yearly and, Dr. Offit added, consider having her uterus removed when she has finished having children.

A growing number of women with BRCA mutations are choosing prophylactic mastectomies and, in some cases, oophorectomies, or removal of the ovaries. That reduces their risk of breast or ovarian cancer 75 percent.

Dr. Coit described a family in which the father and his father both developed thyroid cancer linked to the RET mutation. The younger man’s 6-year-old son was tested and found to carry the same damaged gene. Because the boy was certain to develop thyroid cancer, most likely at a young age, his thyroid was removed. Although the boy will need to take thyroid hormone for the rest of his life, the surgery reduced to zero his chance of developing this often fatal cancer.

Dr. Coit also told of a 33-year-old woman who carried the CDH mutation associated with highly lethal stomach cancer. Her stomach was removed and found to contain three microscopic cancer sites, making her preventive surgery also curative. She is one of 131 patients with the mutation who have had their stomachs removed and a stomachlike pouch created from the small intestine.

The doctor acknowledged that the surgery was a drastic measure, with an operative mortality of 1.5 percent and a complication rate of 53 percent. Most patients cannot eat as much as they used to after the surgery. They develop food intolerances and lose weight, but they do eventually adapt to their new digestive system, Dr. Coit said.

Practical Considerations

Before choosing surgery to reduce risk in an otherwise healthy person, Dr. Coit said these factors should be carefully considered:

¶Possible nonsurgical alternatives.

¶Actual cancer risk from the inherited gene and how much surgery can reduce it.

¶Timing of any operation.

¶Effects of surgery on quality of life.

Another question is how and whether to disclose hereditary cancer risk. Though many people fear limits on their job and ability to obtain affordable health insurance, a federal law was passed this month to prevent such genetic discrimination.

What if someone with a hereditary cancer gene refuses to warn family members of the possible risk and need for tests? These types of questions have begun to arise, in a handful of lawsuits against doctors. In a 1995 case in Florida, for example, the state Supreme Court ruled that a doctor has to inform patients of the risk to family members, but left it to patients to tell them about tests and the potential for prevention.

The deciphering of the human genome has prompted a number of entrepreneurs to cash in on people’s genetic concerns. They offer DNA testing to look for aberrant genes associated with the risk of developing various diseases, especially cancer.

Such testing, when done reliably, might encourage some people to take charge of their health and make better plans for the future. But some professional genetics counselors say this approach to determining cancer risk is fraught with hazards, not the least of which is a false warning of a serious risk that does not exist.

“This kind of testing is premature,” said Dr. Kenneth Offit, chief of clinical genetics at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center. “Some companies are selling research tests for mutations that carry a low risk of causing cancer, leading people to worry needlessly or be falsely reassured.”

Another problem, he said, is the prescription offered after the tests.

“Other companies are telling people what kind of foods to eat and what to put on their skin based on their genes,” Dr. Offit said. “Testing for known cancer genes is legitimate, but often the prescription given for a ‘gene makeover’ is not. Regulation of these labs is sorely needed. And people facing real hereditary cancer risks require intensive professional counseling.

Cancer test a genetic crystal ball for Jewish women

By Lisa Priest : Globe and Mail : May 24, 2008

For the first time in Canada, Jewish women will be offered the chance to alter their genetic destiny by taking a test – at no cost to them – that will determine whether they are at high risk of developing breast and ovarian cancers.

By screening for three inherited breast cancer gene mutations common to those of Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry, Women's College Research Institute scientists have an ambitious goal: to prevent the dreaded disease before it strikes.

They plan to do that by offering adult Jewish women in Ontario, with no known family history of breast or ovarian cancer, the blood test to screen for three specific mutations of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes, beginning this Thursday. Jewish women with a family history of breast or ovarian cancer who have never been tested are also eligible.

If expanding genetic testing to this group proves worthwhile, it could alter the way the testing is offered across Canada by recognizing one's inherent risk of cancer, simply due to ancestry.

The goal of the test is “to prevent cancer,” said Steven Narod, director of the familial breast cancer research unit at Women's College Research Institute in Toronto. One in 44 Ashkenazi Jewish people carry the mutation, he noted; in the general population, an estimated one in 400 individuals carries a mutation in BRCA1 or BRCA2.

For Ashkenazi women, a group with mainly Central and Eastern European ancestry, the test could reveal a risk they never knew they had. Sarah Neumin, a 44-year-old psychotherapist in Toronto, said there was no breast cancer in her family – until her sister was diagnosed with it three years ago. Ms. Neumin has since tested positive for a mutation of the BRCA1 gene that she inherited from her father.

“We had no cancer at all in the family,” said Ms. Neumin, who now undergoes regular screening for breast and ovarian cancer. “We didn't have a lot of females in our extended family who didn't die in the Holocaust. You can't really do a family tree because a lot of people really didn't live that long.”

Canada's Jewish population is overwhelmingly Ashkenazi: 327,360 out of a total of 370,055, according to figures from Charles Shahar, chief researcher of the national census project for UIA Federations Canada. And about half of the Ashkenazi Jewish population – 165,175 – live in Toronto.

Based on the one-in-44 risk factor, 7,440 Ashkenazi Jewish Canadians are unwitting carriers of BRCA1 or BRCA2 genetic mutations.

Until now, Jewish ancestry was not enough to warrant testing for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer anywhere in Canada; nor is there any known organized population screening of Jewish women in the United States. Several years ago, Dr. Narod, who is also a University of Toronto professor, did a trial for recurring mutations among Polish women similar to the one on Jewish women starting next week.

Rabbi Jennifer Gorman, who is also director of youth activities for the United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism, Eastern Canada region, said she can see the test one day being offered the way screening for Tay-Sachs, a fatal genetic lipid storage disorder, is to couples of Jewish ancestry.

“The rate of this gene is so high,” she said. “It will be one of the tests that is normally done.”

A genetic crystal ball

The test is for three genetic mutations that recur in the Jewish population, due to the so-called founder effect, which occurs when a new colony is started by a few members of the original population, often due to geographic or religious isolation.

According to researchers, 40 per cent of today's Ashkenazi Jewish population arose from a group of four founding mothers, who lived somewhere in Europe within the past 2,000 years.

With the marvels of science, their female descendants are being offered the opportunity to peek into the genetic version of a crystal ball. The test has implications for a woman's family: If she tests positive, she must have inherited the genetic mutation from a parent. Her children run a 50-per-cent chance of carrying the gene, as do her siblings. Testing may have implications for those seeking life or critical care insurance, although policies already in place are typically not affected.

Not seeking an answer, however, also carries a steep cost.

About 70 per cent of women who are BRCA1 mutation carriers will develop breast cancer by age 70; about 40 per cent will develop ovarian cancer by the same age. Those who carry the BRCA2 genetic mutation face the same breast cancer risk as those BRCA1 mutation carriers, but their risk of developing ovarian cancer is lower than the BRCA1 group – between 15 and 20 per cent by age 70, according to Dr. Narod's group.

“It empowers women, as far as I'm concerned, to make choices for themselves,” said Rebecca Dent, a medical oncologist at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre in Toronto, who works closely with Dr. Narod.

Women who test positive can be referred to specialized screening. Some of that screening includes magnetic resonance imaging scans of the breasts, pelvic exams, transvaginal ultrasounds and the CA-125 blood test, which measures a protein found in greater concentration in ovarian cancer cells than in other cells, according to the Jewish Population Screening Study paper done by Dr. Narod's research unit.

As well, there are ways to prevent cancer, including drug therapies such as tamoxifen and oral contraceptives. There are also surgical options such as removal of the breasts and ovaries.

By being hooked into a system where the women are followed more closely, there is more opportunity to participate in new drug or screening techniques as they become available, Dr. Dent said.

Dr. Narod, who holds the Canada Research Chair in breast cancer, said the testing is also a good investment: Focusing on those three recurring mutations in the Jewish community means the test is relatively easy to do as the entire genome does not require sequencing.

With the blood test costing about $25 a patient, to be paid for through his research grant, he expects to find a mutation for BRCA1 and BRCA2 in about one in 50 Jewish women. If that turns out to be the case, he estimates it will cost only $1,250 to find someone at high risk of developing breast and ovarian cancer. (Those figures do not include added costs of genetic counselling, laboratory technician time and doctor consultation times.) And finding one patient actually means finding many more – as it leads to the identification and testing of other family members.

Eligible Ontario patients must be willing to travel to Toronto for the test, which is being offered to 1,000 women as part of a research study, at which point it will be re-evaluated.

“If we see 1,000 women with no family history of breast cancer and find no mutation, that tells us the criteria will stay the same,” said Kelly Metcalfe, clinician scientist at Women's College Research Institute. “If we are finding mutations, that suggests the criteria should change, that we should be offering general [Jewish women] population screening to any Ashkenazi Jewish woman who is interested in the test.”

‘No-brainer' testing

Melissa Lieberman-Moses was 32 and in her last trimester of a twin-girl pregnancy in late 2003 when she found a pea-sized lump in her left breast. She had no family history of breast or ovarian cancer, and while doctors thought the lump was probably nothing to worry about, they sent her for an ultrasound, then a biopsy.

It revealed an early-stage breast cancer. She later tested positive for a BRCA1 mutation. As it turned out, that family history hadn't yet revealed itself because her father was the carrier of the genetic mutation.

She underwent a double mastectomy – as well as an oophorectomy, which is removal of the ovaries.

Having the genetic testing, Dr. Lieberman-Moses feels, has saved the lives of some of her family members, who now know what they may face in the future. But she does worry about her children, twins, Aviva and Talia, and son, Sammy, all of whom could be carriers.

“It was worth doing every single measure I could, the most aggressive things I could,” said the 37-year-old Toronto psychologist. “I wanted to live to see my kids get older.” She thinks it's a “good idea for every Jewish woman to get tested so she can take steps to prevent this horrible disease.”

Aletta Poll, genetic counsellor for the familial breast cancer research unit of the Women's College Research Institute, cautioned this test is appropriate only for the Jewish population.

“We're just looking at three specific mutations of these two genes,” Ms. Poll said. “If you are not Jewish and you take this test, it doesn't really mean much. If you are Jewish, you can still have another mutation in these two genes but it's not that likely.”

In a telephone interview, Reform Rabbi Michal Shekel, executive director of the Toronto Board of Rabbis, described the genetic testing as a “no-brainer,” adding that Jewish law – Halacha – insists one is obligated to take care of oneself.

Likewise, Conservative Rabbi Gorman said she can see the testing being talked about among couples the way other genetic diseases are discussed.

“If we know we can reduce our risk and we know we can save lives, then we have to look into the future and say where are we going to go with this,” she said. “… The more education we put out there, the more likely we can conquer this disease. And now, this is one more piece of it.”

Ask Well: Genetic Testing for Breast Cancer

By Roni Caryn Rabin : NY Times : November 27, 2013

Here are answers to some questions about genetic testing for the three common harmful mutations in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes.

Q.

I’m an Ashkenazi Jewish woman. Should I be tested for the mutations in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes?

A.

If you have been diagnosed with breast or ovarian cancer or have a family history of breast or ovarian cancer, you may want to be tested for one of the mutations in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes that are common among Ashkenazi Jews. Knowing your carrier status may help you evaluate your future risk and can be useful information for other family members. If you have cancer, the information can help shape treatment and alert you to other risks (such as a heightened risk for ovarian cancer if you have breast cancer).

While some Israeli doctors want to expand testing and make it routine, general practice in the United States has not encouraged genetic testing for individuals who are cancer-free and don’t have a family history.

But for Ashkenazi Jews, the bar for genetic testing is not as high as for the general population, said Dr. Susan M. Domchek, executive director of the Basser Research Center for BRCA at the University of Pennsylvania’s Abramson Cancer Center.

“If you’re Jewish, we have a low threshold for testing,” Dr. Domchek said. “If you have an aunt who had breast cancer at 51 and you want testing, that’s O.K.”

Keep in mind that the odds of testing positive are fairly low — only one in 40 Ashkenazi Jews, or 2.5 percent, carry the mutation. That is higher than the rate in the general population, in which fewer than 1 percent carry these mutations, but it means you have a 97.5 percent chance of testing negative.

Remember that a family history includes relatives on both sides of the family, including your father’s side.